Abstract

Background

Sepsis is a life-threatening syndrome associated with significant health resource utilization. Previous systematic reviews have demonstrated high healthcare costs during hospitalization with sepsis, but post-discharge health costs have not been characterized. Understanding these costs allows health system decision-makers to identify targets for reducing preventable spending and strain on healthcare resources. This systematic review aims to describe the post-hospitalization healthcare costs among adults living in developed nations who survived an episode of sepsis.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Database of Systematic Reviews from the year 2000 to February 4, 2025. The search strategy was developed by combining concepts of sepsis, costs, study types, and developed countries. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text review and data extraction. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for non-randomized studies. Narrative synthesis was used to summarize findings.

Results

We identified 23 observational studies that met the inclusion criteria. The methods used to calculate and report healthcare costs varied widely across studies, including the types of costs incurred (readmissions, physician visits, medication costs, and others) and the period over which costs were calculated. Across studies, the median total healthcare cost among sepsis survivors in year one after discharge was $28,719 (IQR $21,715) and the median total healthcare cost in year two after discharge was $22,460 (IQR $14,407). The median cost of a readmission for sepsis survivors was $20,320 (IQR $4,889). Six of seven studies that included a non-sepsis comparator group reported that sepsis survivors accrue higher healthcare costs post-discharge compared to individuals without sepsis.

Conclusions

Our systematic review demonstrates that sepsis survivors incur high healthcare costs that can persist for years after discharge from initial hospitalization. These findings underscore the long-term health economic burden of sepsis, highlighting sepsis as an important target for policy and practice interventions that could improve health outcomes and reduce costs.

PROSPERO registration number:

CRD42023456850.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at10.1186/s13054-025-05600-7.

Keywords: Sepsis, Costs, High-cost users

Background

Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to an infection [1]. This syndrome is associated with high in-hospital mortality and initial healthcare costs [2]. Sepsis survivors are at increased risk of hospital readmission, with recent estimates reporting that 1 in 21 adults who survive a sepsis hospitalization are readmitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge [3]. They are also at higher risk for cardiovascular disease and cognitive impairment [4]. Sepsis survivors experience increased healthcare costs and resource utilization due to the long-term sequelae of sepsis in the months and years following hospital discharge.

Previous systematic reviews have described hospital costs of the initial sepsis hospitalization [5, 6], as well as metrics of subsequent healthcare resource utilization after sepsis [7, 8]. However, to our knowledge, there are no published systematic reviews that summarize the healthcare costs incurred by sepsis survivors after hospital discharge. Understanding these post-discharge costs is necessary to inform and justify the development of policy interventions that focus on reducing disease burden and subsequent health costs among sepsis survivors. The World Health Organization passed World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution 70.7 in 2017, encouraging member states to take specific actions to reduce the burden of sepsis [9]. Understanding post-sepsis costs is a crucial step in addressing the global impact of sepsis. Thus, our systematic review aims to describe healthcare costs among sepsis survivors after discharge from the initial sepsis hospitalization.

Methods

This systematic review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [10] and prospectively registered in the PROSPERO registry (registration number CRD42023456850).

Eligibility Criteria

Study inclusion criteria were determined prior to study screening. We included papers that: (1) studied adults in developed countries who (2) had a sepsis hospitalization (3), reported healthcare costs after index hospitalization, and (4) were published in English in the year 2000 or later. All study designs were eligible, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, case series, and other designs. Studies that only reported index hospitalization costs or readmission rates were excluded. Commentaries, letters, conference proceedings, and review articles such as scoping reviews and systematic reviews were excluded. The study setting was limited to developed countries, as defined by the United Nations [11], due to the economic nature of the research question and the differences in health systems between low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries. Search limits were restricted to the year 2000 or later due to changes in critical care clinical practice following the publication of the ARDSNet Trial in 2000 [12] and the release of the Sepsis-2 definition in 2001 [13].

Information Sources

The following databases from the Ovid platform were searched by an information specialist (ME): MEDLINE, MEDLINE ePub Ahead of Print/MEDLINE In-process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Embase Classic + Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. CINAHL Ultimate (EbscoHost) was also searched. All databases were searched from inception to February 4th, 2025.

Search Strategy

The search process followed the Cochrane Handbook [14] and the Cochrane Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) [15] for conducting the search, and the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [16] for reporting. The Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guideline for peer-reviewing the search strategies [17], drawing upon the PRESS 2015 Guideline Evidence-Based Checklist, was used to avoid potential search errors.

The search strategy concept blocks were built on the topics of sepsis AND (economics or costs) AND study types AND developed countries, using both controlled vocabularies and text word searching for each component. The searches were limited to human, adults, English or French language, and publication years 2000 to present. Conference and non-journal materials were removed where possible.

The MEDLINE search strategy is available in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Study Selection

Records identified from searches were uploaded to Covidence [18]. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (VC, FS, ML) followed by full-text review and data extraction. Any discrepancies were resolved with an independent reviewer (KB). Risk of bias assessment was performed by one reviewer (VC, FS, ML) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the risk of bias of non-randomized studies [19].

Data Items and Outcomes

The primary outcome in this systematic review was healthcare costs after discharge from a sepsis hospitalization. We recorded any post-discharge healthcare costs reported in the studies as well as the currency and year for reported costs. All costs were converted to United States Dollar (USD) 2022 using the average Consumer Price Index and Purchasing Power Parity conversion rates from the International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook Database [20, 21]. For original currencies as reported in the included studies, refer to eTable 2 in the Supplement. Costs of the index sepsis hospitalization were not an outcome of interest and were not recorded.

Data collected on study characteristics included study design, sample size, geographic location, sepsis definition used, study population, admission to intensive care unit (ICU) and comparator group (if present). Cost data collected included any post-discharge sepsis costs, the duration of time after discharge over which costs were reported, cost categories, methodology used to measure costs, health cost payer, and any relevant measures of association.

Synthesis Methods

Due to the wide heterogeneity of the types of costs reported by included studies, a meta-analysis was not appropriate [22]. We used narrative synthesis to describe healthcare costs, following the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) guidelines [23]. We calculated medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for total healthcare costs at one year after discharge, total healthcare costs in the second year, and costs of a readmission following sepsis. These summary statistics describe the total long-term cost burden of sepsis, as well as costs due to readmission, which among sepsis survivors can be substantial [24]. Only studies that reported either total costs at one year, total costs at two years, or the cost of a single readmission were included in these summary statistics. Other studies included in this review are described narratively and in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author and year | Study design | Sample size | Country | Sepsis definition | Study population – ward or ICU? | Non-Sepsis Comparator group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrett 2024 | Retrospective cohort study | 927,057 | Canada | ICD-10 codes | Results not reported stratified by ICU and ward. Admission to ICU present in propensity score model. | Hospitalized non-sepsis controls (matched) |

| Braun 2004 | Retrospective cohort study | 2,834 | United States | Sepsis-1 definition using ICD-9-CM codes for sepsis and organ dysfunction | Results not reported stratified by ICU and ward | None |

| Chang 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | 240,198 | United States | ICD-9-CM codes for septicemia, septicemic, bacteremia, disseminated fungal infection, disseminated candida infection, disseminated fungal endocarditis, using the Martin implementation [53] | Not specified | Hospitalizations with congestive heart failure and acute myocardial infarction |

| Farrah 2021 | Retrospective cohort study | 270,669 | Canada | Sepsis-2 using ICD-10 codes | Stratified by ICU and ward | Hospitalized, non-sepsis comparator group (propensity matched controls) |

| Fleischmann-Struzek 2021 | Retrospective cohort study | 159,684 | Germany | Sepsis-1 and sepsis-2 using ICD-10 codes | Stratified by ICU and ward | None |

| Gadre 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | 1,030,335 | United States | ICD-9 codes | Not specified | None |

| Goodwin 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | 43,452 | United States | ICD-9 codes | Not specified | None |

| Lee 2004 | Prospective cohort study | 502 | Canada | Not stated | ICU only | None |

| Letarte 2002 | Retrospective cohort study | 35 (followed up) | Canada | ICD-9 codes for septic shock and septicemia/sepsis | Results not reported stratified by ICU and ward | None |

| Mageau 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | 28,522 SLE patients, of which 1,068 experienced septic shock | France | ICD-10 diagnostic codes for both infection and shock | Results not reported stratified by ICU and ward | SLE patients who did not have sepsis |

| Nissenson 2005 | Retrospective cohort study | 11,572 | United States | ICD-9 code indicating sepsis caused by S. aureus | Not specified | An end-stage renal disease comparator group was used only for comparisons of the costs of the index hospitalization |

| Pandolfi 2023 | Retrospective cohort study | 147,013 | France | Study specific definition combining implicit and explicit sepsis codes in health administrative records | Results not reported stratified by ward and ICU | None |

| Paoli 2018 | Retrospective cohort study | 2,566,689 | United States | ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for sepsis, stratified by severity (septic shock, severe sepsis, sepsis without organ dysfunction, other), or if subjects were reimbursed under a sepsis DRG code with an associated diagnosis of bacteremia | Results not reported stratified by ICU and ward | None |

| Prescott 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | 1,404 | United States | ICD-9-CM codes using the Angus definition [54] | Results not reported stratified by ICU and ward | None |

| Puceta 2024 | Retrospective cohort study | 28,450 | Latvia | ICD-10 codes | Not specified | Non-sepsis hospitalizations (matched) |

| Rose 2023 | Retrospective cohort study | 159,684 | Germany | ICD-10 codes | Results not reported stratified by ICU and ward | None |

| Sankaran 2024 | Retrospective cohort study | 324,694 | United States | MS-DRG criteria based on ICD codes | Not specified | None |

| Schmidt 2022 | Secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study | 210 | Germany | Sepsis-1 using ICD-10 codes | ICU only | None |

| Stinehart 2024 | Retrospective cohort study | 106,189 | United States | ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes | Not specified | None |

| Tew 2021 | Retrospective cohort study | 160,511 | Canada | Sepsis-3 definition, using ICD-10 codes | Not specified | Cancer patients without sepsis |

| Thompson 2018 | Retrospective cohort study | 3,442 | Australia | Sepsis-1 and Sepsis-3 | ICU only | Admitted to ICU with no diagnosis of sepsis |

| Weycker 2003 | Retrospective cohort study | 16,019 | United States | ICD-9 codes, identifying hospitalization with bacterial or fungal infection and organ dysfunction (severe sepsis) | Not specified | None |

| Winkler 2023 | Retrospective cohort study | 41,918 | Germany | ICD-10 codes | Stratified by ICU and ward | None |

ICD: International Classification of Diseases

ICU: Intensive Care Unit

MS-DRG: Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Groups

SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

ESRD: End-Stage Renal Disease

LOS: Length of Stay

Results

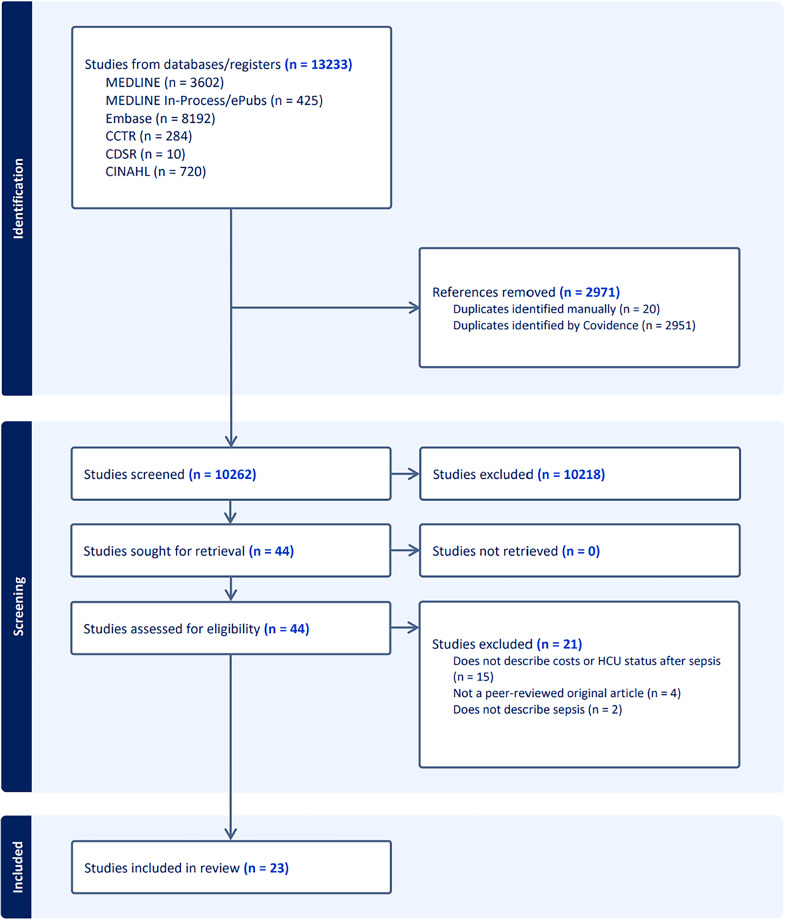

Database searches returned 13,233 results. After deduplication, 10,262 titles and abstracts were screened, and 10,218 articles were excluded at this stage based on clear irrelevance to the review question (e.g. wrong population, exposure, or outcome). The full texts of 44 studies were reviewed, and 23 studies were included in the review [2, 24–45]. The most common reason for exclusion was a lack of description of post-discharge costs (n = 15). The study identification, screening, and inclusion process is summarized in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) [16].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Characteristics of Included Studies and Identification of Sepsis

The study design and characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1. All included studies were cohort studies. The sample sizes of included studies ranged from 35 to 2,566,689 people. The studies represented sepsis costs from the United States (n = 10), Germany (n = 4), Canada (n = 5), Australia (n = 1), Latvia (n = 1) and France (n = 2). The sepsis definition used differed between studies or was not stated. Some studies specified a consensus definition (Sepsis-1, Sepsis-2, or Sepsis-3) [2, 27, 30, 32, 33, 38], while other studies used a different definition and/or used International Classification of Diseases codes to identify sepsis survivors. Seven studies included a comparator group of individuals without sepsis [2, 24, 30, 32, 37, 41, 44], and sixteen did not include a comparator group [25–29, 31, 33–36, 38–40, 42, 43, 45]. All but one [24] of the studies that had a non-sepsis comparator group matched sepsis patients to non-sepsis patients based on characteristics such as age, sex, admission type, comorbidities, length of stay, mechanical ventilation status, trauma, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and others.

Follow-Up Time

Follow-up time after hospital discharge ranged from 30 days to 5 years, with a median follow-up time of 12 months (IQR 30 months).

Identification of Healthcare Costs

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of post-sepsis healthcare costs across studies. Costs were identified using claims-based approaches (n = 10) or through health administrative databases (n = 9). All studies used standardized approaches to calculate costs, although the type of health costs varied widely across studies. Six studies only calculated readmission and hospital-based costs [24, 28, 29, 31, 32, 37], while seventeen studies reported other types of health costs, including outpatient treatment, medication prescriptions, rehabilitation, emergency department visits, long-term care, laboratory and homecare services, same-day surgery visits, primary care and specialist visits, nursing care, or allied health services [2, 25–27, 30, 33–36, 38–45]. Health cost payers were public health insurance (n = 14) or a commercial payor (n = 4).

Table 2.

Description of post-sepsis healthcare costs in included studies

| First author and year | Time period of post-discharge costs | Cost types | Methods for cost estimation | Health costs payer | Costs | Measures of association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrett 2024 | 30-day intervals for up to 4 years | Physician visits, diagnostic tests, same-day surgery, hospitalizations, ED visits, rehabilitation, homecare, prescription drugs, complex continuing care, and long-term care | Individual-level healthcare costs were computed from the public payer’s perspective using a standardized costing methodology for Ontario health administrative databases at ICES | Universal public health insurance | Comparison of high-cost user status between sepsis survivors and individuals who survived a non-sepsis hospitalization | OR 2.24 (95% CI 2.04–2.46) for being a top 5% HCU at any point during discharge. RR 1.46 (95% CI 1.45–1.48) comparing proportion of time spent as a HCU. |

| Braun 2004 | 1 year following admission date of index hospitalization | Medical costs, total outpatient costs, cost of outpatient visits, ED visit costs, pharmacy costs, per-patient per-month (PPPM) outpatient costs, PPPM outpatient visit costs, PPPM pharmacy costs | Reported as defined costs: Costs paid out by insurer, excluding copays and deductibles incurred by patients | Private health insurance |

Survivors of post-discharge period: total mean medical costs = $28,541 ± SD $64,770 (median $7381); total mean outpatient costs = $13,201 ± $20,789 (median $6,907); mean ED visit costs = $1,135 ± $2,342 (median $361); mean pharmacy costs = $2,985 ± $2,342 (median $1,651); Non-survivors of post-discharge period: total mean medical costs = $50,303 ± $93,327 (median $14,720); total mean outpatient costs = $11,943 ± $24,705 (median $4,292); mean ED visit costs = $1,427 ± $3,380 (median $548); mean pharmacy costs = $1,405 ± $2,427 (median $510) |

None |

| Chang 2015 | 30 days post- discharge | 30-day readmission costs | Calculated using charges and cost-to charge ratios | Not specified | Median cost of a readmission within 30 days: $23,205 (IQR $12,668–$43,690) for sepsis. Annual costs of all 30-day readmissions: $600 million/year. | None |

| Farrah 2021 | 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-years post-discharge | Hospitalizations, ED visits, inpatient rehabilitation, long-term and complex continuing care, physician, laboratory and homecare services, and prescription drugs | Individual-level healthcare costs were computed from the public payer’s perspective using a standardized costing methodology for Ontario health administrative databases at ICES [55] | Universal public health insurer |

Year 1 healthcare costs Severe sepsis: $61,117 (SD $71,835) Crude mean difference compared to controls: $22,939 Year 2 Severe sepsis: $28,737 (SD $44,981) Crude mean diff.: $11,368 Year 3 Severe sepsis: $26,919 (SD $41,042) Crude mean diff.: $10,084 Year 4 Severe sepsis: $25,869 (SD $39,279) Crude mean diff.: $9,364 Year 5 Severe sepsis: $25,815 (SD $40,071) Crude mean diff.: $9,415 Estimated 1-yr incremental costs of sepsis in Ontario total $1 billion. |

None |

| Fleischmann-Struzek 2021 | At 1 to 12 months, 13 to 24 months, and 25 to 36 months, among hospital survivors, 12-month survivors, and 24-month survivors | Sum of costs of hospitalizations, outpatient consultations, medication prescriptions, treatment prescriptions, and rehabilitation | Using a health insurance perspective, calculated per patient | Public health insurer |

Mean healthcare costs among all survivors: Year 1: $22,907 ± SD $38,054 (median $10,853) Year 2: $17,696 ± $31,979 (median $7,753) Year 3: $16,185 ± $29,453 per patient in the third year (median $7,087) Total mean healthcare costs in the 3 years after discharge: $44,747 per patient |

None |

| Gadre 2019 | 30 days post-discharge | Readmission costs (cost of hospitalization) | National estimates were produced for cost impact by using sampling weights provided by the sponsor | Not specified |

Mean cost for a readmission within 30 days: $18,980 Annual cost of sepsis readmission in the US: >$4 billion |

None |

| Goodwin 2015 | 30 days and 180 days after index hospital discharge | Cumulative readmission costs | Calculated using charges and cost-to-charge ratios | Commercial payor, Medicaid, Medicare, dual-eligible, and other |

Mean cost of each readmission: $31,490 (SD $47,862) Cumulative readmissions cost over 30 days: $452 million Cumulative readmissions cost over 180 days: $1.4 billion |

None |

| Lee 2004 | Years 1, 2, and 3 after hospital discharge | Hospitalization (excluding nursing home admission), ED, and same-day surgery visits within any of the three Calgary hospitals, all hospital admissions in Alberta, and all Alberta physician claims | Direct healthcare costs incurred by healthcare payor | Universal public health insurer |

Mean costs of care: Year 1: $26,698 Year 2: $9,139 Year 3: $9,078 |

None |

| Letarte 2002 | From 29 days up to 14.5 months after discharge | Follow-up costs after 28 days: prolonged hospitalization, readmission, ambulatory care | From a ministry of health perspective, based on use and unit cost | Public health insurance |

Total cost of prolonged hospitalization: $689,351 Total cost of readmission: $618,107 Total cost of ambulatory care: $26,498 |

None |

| Mageau 2019 | 1 year | Hospital costs (due to readmission) | Health administrative database | Not specified |

One-year healthcare use total cost (n = 738)1: $23,396 (SD $33,145) No significant difference in mean year 1 costs between sepsis survivors and controls, p = 0.3276 |

None |

| Nissenson 2005 | 12 weeks following the episode of care | Inpatient facility and physician services | Administrative and claims data from the United States Renal Data System | Medicare (federal health insurance for older adults) | Total cost of care over 12 weeks: $30,072/person (SD $35,637) | None |

| Pandolfi 2023 | 3 years | Ambulatory care and hospital care (inpatient and day care) | Health administrative database | Not described | Compared to the costs of pre-sepsis care ($3.6 billion), the total medical cost per patient was higher post-sepsis, reaching $4.9 billion | None |

| Paoli 2018 | 30 days following index hospitalization | Readmission costs | Billing records per the cost accounting method used by each hospital | Not specified |

Mean cost of 30-day all-cause readmission hospitalization: Sepsis without organ dysfunction: $16,679 (SD $26,956, median $10,142) Severe sepsis: $18,316 (SD $26,703, median $11,094) Septic shock: $21,660 (SD $34,111, median $12,568) |

None |

| Prescott 2014 | Throughout the 1 year following hospital discharge | Total Medicare spending, including inpatient and outpatient care | Insurance claims-based approach | Medicare |

Total Medicare spending in one year after discharge, median (IQR): Normal weight: $35,720 ($70,000) Overweight: $38,581 ($83,490) Obese: $50,741 ($89,186) Severely obese: $92,363 ($200,843) |

None |

| Puceta 2024 | 1 year | GP visits, specialist consultations, laboratory diagnostics, other outpatient care, and filled prescriptions of reimbursed medicines and medical products | Health administrative database | Public health insurance and patient co-payments |

Per patient, median at one year (IQR): Inpatient care (rehospitalizations): $1874 ($3,471) in sepsis, $1679 ($2,849) in non-sepsis, p < 0.001 Outpatient care (total): $334 ($624) sepsis, $385 ($657) non-sepsis, p < 0.001 PCP visits: $135 ($170) sepsis, $135 ($170) non-sepsis Specialist consultations: $86 (170) sepsis, $102 ($208) non-sepsis, p < 0.001 Laboratory diagnostics: $62 ($104) sepsis, $60 ($93) non-sepsis Other outpatient care: $119 ($3,648) sepsis, $133 ($363) non-sepsis, p = 0.005 Pharmaceuticals: $383 ($991) sepsis, $319 ($761) non-sepsis, p < 0.001 |

None |

| Rose 2023 | 1 year | Hospitalizations, outpatient consultations, medications, treatments (e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy) and rehabilitation | Claims-based approach | Public payer |

1-year overall mean post-sepsis healthcare costs: $26,416 (SD $40,382) in hospital-acquired (HAI) sepsis patients, $21,747 (SD $14,707) in community-acquired (CAI) sepsis patients. In severe sepsis patients, overall mean healthcare costs at one year were $21,581 (SD $9,395) in CAI, $26,062 (SD $7,393) in HAI patients. |

None |

| Sankaran 2024 | 90 days | Inpatient and outpatient physician services, readmissions, hospital outpatient care, post-acute care, and outlier spending | Claims-based approach | Medicare | Mean 90-day episode spending on post-acute care: $5051 | None |

| Schmidt 2022 | 0–6 months, 7–12 months, and 13–24 months | Hospitalizations, rehabilitative care, GP visits, specialist visits, clinical diagnostics, prescription of allied health services, nursing care and medications | Medication costs were calculated using standardized pharmacy selling prices. All other costs were calculated using the German physician reimbursement scheme | Publicly funded health insurance |

Total direct costs per patient: 0–6 months: $25,224 (SD $34,466), median $8,701 7-12 months: $12,991 (SD $18,285), median $4,765 13–24 months: $26,911 (SD $30,781), median $18,458 |

None |

| Stinehart 2024 | 1 year | ED visits, inpatient hospitalizations, skilled nursing facility admissions, primary care visits, physical therapy visits, occupational therapy visits, and home healthcare visits | Claims-based approach | Employer health insurance | Overall median (IQR) healthcare expenditures at one year were: $24,525 ($13,428–$56,323) | None |

| Tew 2021 | 5 years | Inpatient hospitalizations, ED visits, cancer clinic visits, physician services, diagnostic tests, long-term care, prescription drugs, chemotherapy and radiotherapy | Individual-level healthcare costs were computed from the public payer’s perspective using a standardized costing methodology for Ontario health administrative databases at ICES | Universal public health insurer |

5-year total excess cost of care among patients who developed sepsis: Hematology patients: $69,491 (95% CI, $68,543-$70,440) Solid tumor patients: $55,565 (95% CI, $54,663-$56,465) Excess costs of care due to sepsis in year 1: Hematology patients: $42,239 (95% CI, $41,645-$42,834) Solid tumor patients: $26,614 (95% CI, $25,995-$27,233) |

None |

| Thompson 2018 | 2 years after treatment | Cost of ICU admission and cost of hospital admission, inclusive of ICU admission costs, 2 years after treatment | Costs for ICU admissions were measured using the New South Wales cost of care standards cost per bed per day. Total hospital costs were derived from matching Australian Refined Diagnostic Related Group codes to publicly available government reimbursement figures. | Not specified |

Total cost of hospital treatment to 2 years: Sepsis: $58,759 (SD $60,750) Non-sepsis: $52,168 (SD $47,451) p = 0.005 |

None |

| Weycker 2003 | At index admission, the 90- and 180-day periods following admission, and annually thereafter (up to 5 years) | Hospital admissions, outpatient visits (e.g., ED visits and physician office visits), and outpatient pharmacotherapy | Estimated using billed amounts for all paid facility, professional service, and outpatient pharmaceutical claims occurring between index admission and the end of follow-up | Private health insurance |

Mean cumulative costs at 1 year: $124,841 (SE $1,431) Mean cumulative costs at 5 years: $188,931 (SE $2,704) |

None |

| Winkler 2023 | At 7–12 months and at 13–36 months after sepsis hospitalization | Mean total healthcare costs as well as costs for hospitalizations, outpatient consultations, medications, treatments (e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy), and rehabilitation | Measured as actual health expenditures from an insurance perspective and calculated per patient | Public health insurer |

Total mean healthcare costs at 7–12 months, in survivors without an ICU admission: $8,767 (95% CI, $8,229-$9,307) in rehabilitation group, $8,419 (95% CI, $8,232-$8,607) in non-rehabilitation group Total mean healthcare costs at 7–12 months, in survivors with an ICU admission: $9,760 (95% CI, $8,991-$10,349) in rehabilitation group, $10,333 (95% CI, $9,907-$10,759) in non-rehabilitation group |

None |

1n=738 refers to the total number of sepsis survivors in the study. The total sample size was 1,068, and 738 individuals survived post-discharge.

ICU: Intensive Care Unit

CI: Confidence Interval

SD: Standard Deviation

ED: Emergency Department

DRG: Diagnosis Related Groups

APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

GP: General Practitioner

PCP: Primary Care Practitioner

IQR: Interquartile Range

OR: Odds Ratio

RR: Relative Rate

HCU: High-Cost User

Total Post-Discharge Costs Among Sepsis Survivors

Figure 2 visualizes total costs at one year, total costs in the second year, and costs of a readmission. Healthcare costs among sepsis survivors were highest in the first year after discharge, although they varied across studies due to different calculation methods. Ten studies calculated total mean or median healthcare costs at one year after sepsis discharge [2, 26, 27, 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43]. The median one-year total cost across studies was $28,719 (IQR $21,715). Total healthcare costs remained high in the second year after discharge, but declined slightly, with a median year-two cost of $22,460 (IQR $14,407) across studies [2, 26, 27, 33]. Sepsis survivors continued to accrue high costs in the three to five years after discharge, with costs in year three ranging from approximately $9,000 to $27,000 [2, 26, 27, 30].

Fig. 2.

Median total healthcare costs among sepsis survivors in the first year after discharge (n = 10 studies), in the second year after discharge (n = 4 studies), and median cost of a readmission following sepsis (n = 4 studies)

Readmission Costs Among Sepsis Survivors

Four studies calculated readmission cost with the mean or median cost of readmission ranging from approximately $16,700 to $31,500 [24, 28, 29, 31]. The median cost of a readmission across studies was $20,320 (IQR $4,889). Letarte et al. totaled the cost of readmissions for all fifteen readmitted patients in their study up to 14.5 months after discharge, which was $618,107 [36].

Comparison of Post-Discharge Costs Between Sepsis and Non-Sepsis Survivors

Seven studies compared healthcare costs between sepsis survivors and individuals who survived a non-sepsis hospitalization [2, 24, 30, 32, 37, 41, 44]. Healthcare costs after discharge were higher among sepsis survivors. For example, Thompson et al. found the overall cost of hospital treatment at up to two years was higher in sepsis patients (sepsis: $58,759, non-sepsis: $52,168) [32]. Chang et al. reported the total annual cost of 30-day sepsis readmissions in California was higher than that of readmissions for congestive heart failure (CHF) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) combined (sepsis: $617 million, CHF: $283 million, AMI: $175 million) [24]. Of the seven studies that compared post-discharge healthcare costs between individuals with sepsis and individuals without sepsis, six found that costs were higher among those with sepsis [2, 24, 30, 32, 41, 44].

Health Care Costs Among Sepsis Survivors Relative to Population Health Spending

One study by Barrett et al. described post-discharge healthcare costs among sepsis survivors compared to survivors of a non-sepsis hospitalization with respect to total population healthcare spending using the concept of high-cost users (HCUs). They defined HCUs as individuals whose total healthcare costs were at or above the 95th percentile of total population healthcare costs (i.e., top 5% HCUs). They found that individuals who survived a sepsis hospitalization were more likely to be a top 5% HCU at any time after discharge compared to those who survived a non-sepsis hospitalization (OR 2.24 (95% CI 2.04–2.46)) and that they spent more time as a HCU after discharge (RR 1.46 (95% CI 1.45–1.48)) [44]. This was the only study that described costs using the HCU concept. Two studies described disproportionate healthcare costs in a small subset of individuals [26, 31]. Lee et al. calculated the frequency distribution of healthcare spending among sepsis survivors and found that the total cost of care was positively skewed, suggesting that a minority of patients were responsible for the majority of resource use within the cohort [26]. Goodwin et al. discussed the disproportionate burden of readmission among sepsis survivors, stating that a minority of survivors represented a disproportionate number of readmissions. In their study, individuals with multiple readmissions accounted for 77.3% of all readmissions with a cumulative cost of $1.08 billion [31]. Although HCUs are typically identified by comparing individual spending to the entire population distribution of spending rather than just to the study cohort, the findings of these two studies nevertheless highlight the skewed nature of healthcare spending among sepsis survivors.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The results of risk of bias assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the risk of bias of non-randomized studies can be found in Table 3. Studies were rated on domains of selection of cohorts, comparability of cohorts, and ascertainment of outcome. One study was rated ‘not low risk of bias’ [26], while the remaining were rated ‘low risk of bias’.

Table 3.

Results of risk of bias assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for assessing risk of bias of non-randomized studies

| First author and year | Representative exposed cohort?1 | Selection of non-exposed cohort2 | Ascertainment of exposure3 | Outcome not present at start of study4 | Comparability of cohorts5 | Assessment of outcome6 | Long enough follow-up?7 | Adequacy of follow-up8 | Overall risk of bias rating9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrett 2024 | A | A | A | A | A, B | B | A | A | Low |

| Braun 2004 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | D | Low |

| Chang 2015 | A | A | A | A | A, B | B | A | A | Low |

| Farrah 2021 | A | A | A | A | A, B | B | A | B | Low |

| Fleischmann-Struzek 2021 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | D | Low |

| Gadre 2019 | A | C | A | A | A, B | B | A | D | Low |

| Goodwin 2015 | A | C | A | A | A, B | B | A | A | Low |

| Lee 2004 | A | C | D | A | N/A | B | A | D | Not low |

| Letarte 2002 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | B | Low |

| Mageau 2019 | A | A | A | A | A, B | B | A | D | Low |

| Nissenson 2005 | A | A | A | A | B | B | A | C | Low |

| Pandolfi 2023 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | A | Low |

| Paoli 2018 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | B | Low |

| Prescott 2014 | A | A | C | A | A | B | A | B | Low |

| Puceta 2024 | A | A | A | A | A, B | B | A | A | Low |

| Rose 2023 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | A | Low |

| Sankaran 2024 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | A | Low |

| Schmidt 2022 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B, C | A | D | Low |

| Stinehart 2024 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | A | Low |

| Tew 2021 | A | A | A | B | A, B | B | A | B | Low |

| Thompson 2018 | C | A | A | A | A, B | B | A | D | Low |

| Weycker 2003 | A | C | A | A | N/A | B | A | B | Low |

| Winkler 2023 | A | A | A | A | A, B | B | A | D | Low |

1 Representativeness of the exposed cohort: A* = truly representative of the average ___ in the community. B* = somewhat representative of the average ____ in the community. C = selected group of users. D = no description of the derivation of the cohort

2 Selection of the non-exposed cohort: A* = drawn from the same community as the exposed cohort. B = drawn from a different source. C = no description of the derivation of the non-exposed cohort

3 Ascertainment of exposure: A* = secure record (e.g. surgical records). B* = structured interview. C = written self-report. D = no description

4 Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of study: A* = yes. B = no

5 Comparability of cohorts on the basis of design or analysis: A* = study controls for ___ (most important factor). B* = study controls for any additional factor

6 Assessment of outcome: A* = independent blind assessment. B* = record linkage. C = self-report. D = no description

7 Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur: A* = yes. B = no

8 Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts: A* = complete follow-up – all subjects accounted for. B* = subjects lost to follow up unlikely to introduce bias – small number lost, or description provided of those lost. C = follow up rate low and no description of those lost. D = no statement

9 Overall risk of bias rating: Low risk of bias = 3 or 4 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome domain. Not low risk of bias = 2 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome domain, or fewer stars across domains

Discussion

Our review highlights the substantial healthcare costs incurred after sepsis, reflecting the long-term impacts of this syndrome. Among the included studies, post-discharge costs were largely driven by rehospitalization and hospital-based costs. We found that costs in the first year exceeded $60,000 per patient in the highest reported estimate, and costs remained elevated at five years post-discharge. In the included studies, healthcare costs were higher in sepsis survivors compared to individuals who survived a non-sepsis hospitalization.

Our findings align with previous research, which shows that sepsis survivors face long-term sequelae, including disability, cognitive impairment, and declines in physical functioning [46], that place them at risk for increased healthcare costs. For sepsis survivors treated in the ICU, the post-sepsis experience overlaps with post-intensive care syndrome, which is characterized by physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments that can persist for years after critical illness [47]. These post-sepsis sequelae contribute to substantial post-discharge healthcare costs, which are largely driven by rehospitalization, as demonstrated by Chang et al. [24]. Additionally, evidence from a population-based matched cohort study of adults without prior cardiovascular disease showed that surviving a first sepsis hospitalization was associated with a 30% increase in the hazard of major cardiovascular events during long-term follow-up compared to survivors of non-sepsis hospitalizations [48]. The studies included in our review noted not only increased costs after discharge, but increased resource utilization, such as readmissions, outpatient visits, and medication use. This underscores that the burden of sepsis extends beyond the first hospitalization, contributing to sustained healthcare utilization and long-term costs due to chronic sequelae.

Sepsis represents significant costs within overall health system spending, with evidence suggesting that sepsis survivors become HCUs and account for a disproportionate share of healthcare expenditures [49]. Identifying these HCUs is important for policymakers and health system decision-makers because it enables the development of targeted interventions that can yield substantial cost savings. Three studies in our review described how certain sepsis survivors incur healthcare costs that place them amongst the highest-cost users [26, 31, 44]. Sepsis presents a high-cost burden both during the initial hospitalization, with one systematic review estimating the median of the mean hospital-wide cost of sepsis per patient at $32,421 (2014 USD) [5], and after discharge, as supported by the findings of our review. Coordinated policy efforts, such as those described in the Berlin Declaration [50] on sepsis and WHA resolution 70.7, can reduce the burden of sepsis through national action plans and strategic investments in prevention, early recognition, and post-discharge care [9]. By mitigating the in-hospital and long-term consequences of sepsis, these policy efforts can improve health outcomes for sepsis survivors and may help contain healthcare costs to address the larger economic impact of sepsis [51].

Of the 23 studies in this review, only seven included a non-sepsis comparator group, limiting further analyses of the economic burden of sepsis relative to other patient populations. While these studies consistently demonstrated higher healthcare spending among sepsis versus non-sepsis survivors, we identified heterogeneity across studies in terms of the type of costs reported, the time period over which costs were calculated, and the descriptive statistics and measures of association used to quantify costs. This made it difficult to compare post-sepsis costs across studies and precluded a formal meta-analysis [22]. The summary statistics provided for year one costs, year two costs, and readmission costs are offered to provide a general estimate of cost patterns but should be interpreted with caution due to the variability across studies. Although the increased costs associated with sepsis are evident, the heterogeneity in cost calculations and study design limits the overall precision of the findings. Due to this heterogeneity, it was not feasible to conduct comparisons across countries or to summarize the contribution of disaggregated cost components, such as surgical, outpatient, readmission, or medication-related expenses, to overall post-discharge costs. Furthermore, best practices for healthcare costing analyses recommend against direct comparison of costs between different jurisdictions due to the lack of harmonized reporting of costing methodologies [52].

Our review highlights the high post-discharge burden associated with sepsis hospitalizations, emphasizing the need for a policy response and future research. To inform targeted interventions, future research should focus on identifying risk factors that place individuals at greater risk of sepsis and, thus, resource utilization. While measures of health-related quality of life were outside of the scope of this review, future health economic evaluations should consider measures such as health utility values, and metrics of health-related quality of life over time, such as disability life years (DALYs) and quality adjusted life years (QALYs). Lastly, all included studies reported data collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research on the pandemic’s impact on sepsis-related healthcare costs could support preparedness efforts, given the changes to critical care delivery and health system pressures seen during this time. In a healthcare system challenged by an aging population and constrained resources, it is increasingly important to identify the populations that accrue high healthcare costs and implement strategies to reduce the burden on the healthcare system.

Conclusions

In this study, we describe the healthcare costs of sepsis survivors after their initial hospitalization. Across all geographic regions represented in the studies, sepsis survivors face high healthcare costs, and these healthcare costs persist for years after discharge. Our results demonstrate the significant health economic burden of sepsis on health payors. Efforts to reduce the burden of sepsis, as outlined in the World Health Assembly resolution 70.7, may help to reduce its economic impact.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SWiM

Synthesis Without Meta-analysis

- IQR

Interquartile range

- USD

United States Dollar

- WHA

World Health Assembly

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- MECIR

Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews

- PRESS

Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

- APACHE

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- CHF

Congestive heart failure

- AMI

Acute myocardial infarction

- HCU

High-cost user

- OR

Odds ratio

- RR

Relative rate

Author contributions

KB and VC conceptualized the study. ME created the search strategy and performed database searches. VC, FS, and ML screened articles for inclusion and performed data extraction and study quality assessment. VC drafted the manuscript, with input from KB, FS, ML, and ME. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/6/2025

The Eligibility Criteria section contains a list which were incorrectly indicated as reference citations in the original publication, this article has been updated.

References

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrah K, McIntyre L, Doig CJ, Talarico R, Taljaard M, Krahn M, et al. Sepsis-associated mortality, resource use, and healthcare costs: a propensity-matched cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(2):215–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackermann K, Lynch I, Aryal N, Westbrook J, Li L. Hospital readmission after surviving sepsis: a systematic review of readmission reasons and meta-analysis of readmission rates. J Crit Care. 2025;85: 154925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankar-Hari M, Rubenfeld GD. Understanding long-term outcomes following sepsis: implications and challenges. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2016;18(11):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arefian H, Heublein S, Scherag A, Brunkhorst FM, Younis MZ, Moerer O, et al. Hospital-related cost of sepsis: a systematic review. J Infect. 2017;74(2):107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Berg M, van Beuningen FE, ter Maaten JC, Bouma HR. Hospital-related costs of sepsis around the world: a systematic review exploring the economic burden of sepsis. J Crit Care. 2022;71: 154096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar-Hari M, Saha R, Wilson J, Prescott HC, Harrison D, Rowan K, et al. Rate and risk factors for rehospitalisation in sepsis survivors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive care medicine. 2020;46(4):619–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPeake J, Bateson M, Christie F, Robinson C, Cannon P, Mikkelsen M, et al. Hospital re-admission after critical care survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2022;77(4):475–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheikh F, Chechulina V, Garber G, Hendrick K, Kissoon N, Proulx L, et al. Reducing the burden of preventable deaths from sepsis in Canada: A need for a national sepsis action plan. Healthc Manage Forum. 2024;37(5):366–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Classifications | UNCTAD Data Hub [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 9]. Available from: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/Classifications.html

- 12.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gül F, Arslantaş MK, Cinel İ, Kumar A. Changing definitions of sepsis. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2017;45(3):129–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Collab [Internet]. 2024; Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current

- 15.Higgins JPT, Lasserson T, Thomas J, Flemyng E, Churchill R. Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews. 2023; Available from: https://community.cochrane.org/mecir-manual

- 16.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covidence systematic review software [Internet]. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; Available from: www.covidence.org.

- 19.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2011;2:1–12 https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner HC, Lauer JA, Tran BX, Teerawattananon Y, Jit M. Adjusting for inflation and currency changes within health economic studies. Value Health. 2019;22(9):1026–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IMF [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 8]. World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database. Available from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/download-entire-database

- 22.Imrey PB. Limitations of meta-analyses of studies with high heterogeneity. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang DW, Tseng CH, Shapiro MF. Rehospitalizations following sepsis: common and costly. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(10):2085–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nissenson AR, Dylan ML, Griffiths RI, Yu HT, Dean BB, Danese MD, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus septicemia in ESRD patients receiving hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(2):301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee H, Doig CJ, Ghali WA, Donaldson C, Johnson D, Manns B. Detailed cost analysis of care for survivors of severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):981–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleischmann-Struzek C, Rose N, Freytag A, Spoden M, Prescott HC, Schettler A, et al. Epidemiology and costs of postsepsis morbidity, nursing care dependency, and mortality in Germany, 2013 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11): e2134290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paoli CJ, Reynolds MA, Sinha M, Gitlin M, Crouser E. Epidemiology and costs of sepsis in the United States-an analysis based on timing of diagnosis and severity level. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(12):1889–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gadre SK, Shah M, Mireles-Cabodevila E, Patel B, Duggal A. Epidemiology and predictors of 30-day readmission in patients with sepsis. Chest. 2019;155(3):483–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tew M, Dalziel K, Thursky K, Krahn M, Abrahamyan L, Morris AM, et al. Excess cost of care associated with sepsis in cancer patients: results from a population-based case-control matched cohort. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodwin AJ, Rice DA, Simpson KN, Ford DW. Frequency, cost, and risk factors of readmissions among severe sepsis survivors. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(4):738–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson K, Taylor C, Jan S, Li Q, Hammond N, Myburgh J, et al. Health-related outcomes of critically ill patients with and without sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(8):1249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt KFR, Huelle K, Reinhold T, Prescott HC, Gehringer R, Hartmann M, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in sepsis survivors in Germany--secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022;11(4):1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weycker D, Akhras KS, Edelsberg J, Angus DC, Oster G. Long-term mortality and medical care charges in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(9):2316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prescott HC, Chang VW, O’Brien JM Jr, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Obesity and 1-year outcomes in older Americans with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):1766–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Letarte J, Longo CJ, Pelletier J, Nabonne B, Fisher HN. Patient characteristics and costs of severe sepsis and septic shock in Quebec. J Crit Care. 2002;17(1):39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mageau A, Sacre K, Perozziello A, Ruckly S, Dupuis C, Bouadma L, et al. Septic shock among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: short and long-term outcome. Analysis of a French nationwide database. J Infect. 2019;78(6):432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braun L, Riedel AA, Cooper LM. Severe sepsis in managed care: analysis of incidence, one-year mortality, and associated costs of care. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10(6):521–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winkler D, Rose N, Freytag A, Sauter W, Spoden M, Schettler A, et al. The effects of postacute rehabilitation on mortality, chronic care dependency, health care use, and costs in sepsis survivors. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(2):279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stinehart KR, Hyer JM, Joshi S, Brummel NE. Healthcare use and expenditures in rural survivors of hospitalization for sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2024;52(11):1729–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puceta L, Luguzis A, Dumpis U, Dansone G, Aleksandrova N, Barzdins J. Sepsis in Latvia-incidence, outcomes, and healthcare utilization: a retrospective, observational study. Healthcare. 2024;12(2): 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pandolfi F, Brun-Buisson C, Guillemot D, Watier L. Care pathways of sepsis survivors: sequelae, mortality and use of healthcare services in France, 2015–2018. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose N, Spoden M, Freytag A, Pletz M, Eckmanns T, Wedekind L, et al. Association between hospital onset of infection and outcomes in sepsis patients - a propensity score matched cohort study based on health claims data in Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2023;313(6): 151593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barrett KA, Sheikh F, Chechulina V, Chung H, Dodek P, Rosella L, et al. High-cost users after sepsis: a population-based observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2024;28:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sankaran R, Gulseren B, Prescott HC, Langa KM, Nguyen T, Ryan AM. Identifying sources of inter-hospital variation in episode spending for sepsis care. Med Care. 2024;62(7):441–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith S, Rahman O. Postintensive Care Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 [cited 2025 Mar 24]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558964/ [PubMed]

- 48.Angriman F, Rosella LC, Lawler PR, Ko DT, Wunsch H, Scales DC. Sepsis hospitalization and risk of subsequent cardiovascular events in adults: a population-based matched cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(4):448–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosella LC, Fitzpatrick T, Wodchis WP, Calzavara A, Manson H, Goel V. High-cost health care users in Ontario, Canada: demographic, socio-economic, and health status characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Global Sepsis Alliance [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 17]. Berlin Declaration. Available from: https://globalsepsisalliance.org/berlin-declaration

- 51.Lives and money. Understanding the true cost of sepsis in Canada [Internet]. Open Access Government. 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/article/lives-and-money-understanding-the-true-cost-of-sepsis-in-canada/190252/

- 52.Mogyorosy Z, Smith PC. The main methodological issues in costing health care services - a literature review. York, UK: Centre for Health Economics, University of York; 2005. (CHE Research Paper). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schull MJ, Azimaee M, Marra M, Cartagena RG, Vermeulen MJ, Ho M, et al. ICES: data, discovery, better health. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2020;4(2): 1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.