Abstract

Background

The invasive weed Ageratina adenophora poses significant ecological threats, necessitating novel control strategies. This study investigated the phytotoxic potential of methyl indole-3-acetate (MEIAA) through foliar application. As a methylated derivative of IAA, MEIAA exists in plants at extremely low concentrations and exhibits herbicidal properties distinct from conventional auxin mimics such as 2,4-D. Additionally, we integrated histochemical staining, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and multi-omics analyses to reveal MEIAA mediated structural changes in A. adenophora.

Results

At 20 mM (optimized concentration), MEIAA induced dose-dependent stem curvature (1d post-treatment) and apical meristem necrosis (3d). Mechanistic analyses revealed three combined effects: (1) Structural compromise: MEIAA reduced lignin (20–73%), cellulose (9–29%), hemicellulose (4–11%), and pectin (6–36%) in stems, impairing mechanical integrity. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) further demonstrated severe ultra-structural aberrations, including plasmolysis, organelle disintegration, and cell wall fragmentation. (2) Vascular collapse: Histological staining revealed disorganized vascular bundles and lignin-depleted xylem vessels, disrupting water/nutrient transport. (3) Metabolic-transcriptional dysregulation: Multi-omics integration identified MEIAA-induced perturbations in carbohydrate metabolism (e.g., elevated D-mannose, D-galactose; altered starch/sucrose pathways) and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (suppressed lignin precursors: coniferaldehyde, sinapaldehyde). Concurrently, MEIAA bi-directionally regulated 26 phytohormone signaling genes (e.g., AUX/IAA, ARF, PYR/PYL), diverting metabolic flux from growth to stress responses. Crucially, qRT-PCR validated RNA-seq reliability, highlighting MEIAA’s unique regulatory divergence from both natural auxin (IAA) and synthetic analogs like 2,4-D.

Conclusion

These findings position MEIAA as a potent and distinctive auxin-mimic herbicide, disrupting physiological homeostasis via multi-target inhibition. Our results provide a mechanistic foundation for developing MEIAA as an eco-friendly herbicide specifically for controlling invasive A. adenophora.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-07095-4.

Keywords: Ageratina adenophora, Methyl indole-3-acetate (MEIAA), Stem curvature, Vascular system, Cell wall components, Multi-omics Apporach

Background

The perennial semi-shrub Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.), native to Central America, has emerged as a globally invasive species following its accidental introduction to southern China in the 1940 s [1, 2]. Its rapid colonization of southwestern China and the Yangtze River basin-expanding 20–30 km annually has precipitated severe ecological degradation through competitive exclusion of native flora and disruption of ecosystem services [3, 4]. Despite multidisciplinary control efforts, including biocontrol agents and herbicide applications, sustainable management remains unattained [5], necessitating innovative strategies targeting its unique physiological vulnerabilities.

Methyl indole-3-acetate (MEIAA), a methyl-esterified conjugate of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), is synthesized via IAA carboxyl methyltransferase (IAMT) using S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) as a methyl donor [6–8]. Though transient and low-abundance in planta, MEIAA exhibits distinct bioactivity: it suppresses hypocotyl elongation and root development in Arabidopsis more potently than IAA while enhancing lateral root initiation [7, 9, 10]. Recent studies further demonstrated its species-specific phytotoxicity, inhibiting germination in Panicum miliaceum [11] and inducing chloroplast ultra-structural damage in Avena fatua [12]. These studies demonstrate that MEIAA exhibits varying effects on different plant tissues and organs, suggesting it may also possess certain herbicidal activity.

The common effects induced by auxin-like herbicides include epinastic deformations of roots and shoots, stem bending, senescence, and growth inhibition [13]. These are accompanied by reduced stomatal aperture, carbon assimilation, and transpiration, as well as damage to membranes and vascular systems, localized cell death, and plant decay [14]. These phenomena are also referred to as the “overdose effects” of auxins. Concentration-dependent auxinic herbicides, such as 2,4-D, dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, triclopyr, and dicamba, function similarly to the natural plant auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) [14, 15]. At high concentrations, they disrupt normal plant growth and cause lethal damage [16, 17]. Their biological activity is also influenced by plant species, tissue sensitivity, and physiological stage [14].

Our preliminary studies revealed that MEIAA not only induces stem curvature in A. adenophora but also causes necrosis of its growing points. However, the underlying mechanisms of these phenomena remain to be elucidated. Stem curvature is typically associated with a complex array of cellular and physiological factors, with insufficient mechanical strength being a primary contributing factor [18]. The mechanical strength of stems largely depends on the compositional ratios of cell wall carbohydrates such as lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin [19–22]. We hypothesize that MEIAA-induced stem curvature in A. adenophora may involve the degradation of these critical cell wall components. Additionally, MEIAA likely exerts disruptive effects on the morphological structure of stem cells, as organ curvature in plants is invariably accompanied by cellular deformation [23–25]. In light of this, the present study first identified an optimal spraying concentration (20 mM) through dose-response screening. Subsequently, we employed light microscopy and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to examine cellular structural differences between MEIAA-induced curved stems, control curved stems, and straight stems. We further analyzed variations in major cell wall components among these stem types, complemented by metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses to characterize differential changes in related metabolites and gene expression patterns. This work contributes to a clearer understanding of the mechanisms underlying MEIAA-induced stem curvature and growth point lethality in A. adenophora, while expanding knowledge about MEIAA’s target sites across diverse plant species. The findings may enrich the mechanistic framework of auxin-like herbicides and provide novel perspectives and experimental foundations for developing next-generation auxin-based herbicide applications.

Materials and methods

The Ageratina adenophora (commonly known as Crofton weed) used in this study was propagated from stem cuttings. The specific procedures were as follows: In May 2023, healthy fresh aboveground parts were collected from natural populations of A. adenophora on the campus of Yunnan Agricultural University (25°N, 102°E). After removing extraneous branches and leaves, stems were segmented into 3–5 cm cuttings, which were then cultivated in seedling substrate for approximately 120 days. Plants meeting the criteria of 20 cm height and absence of pests/diseases were selected for treatment. Whole plants were sprayed with 4, 20, and 100 mM MeIAA solutions. Experimental controls included: (1) equivalent concentrations of IAA solution as a positive control, (2) 80% anhydrous ethanol as a solvent control, and (3) distilled water as a blank control. Each treatment group consisted of three pots (three biological replicates), with three seedlings per replicate. Plant phenotypic changes were observed at 1, 3, and 5 days after spraying to identify the optimal treatment concentration of 20 mM. Subsequently, A. adenophora stems treated with 20 mM were used for cytological observation, cell wall component analysis, and transcriptomic and metabolomic studies. (Note: As a widely distributed species in Yunnan Province and a key control target in agricultural/forestry systems, A. adenophora requires no special permits for scientific collection. Taxonomic identification was performed by Dr. Pan-Li, with voucher specimens deposited in the Herbarium of Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Digital voucher records are accessible at https://www.cvh.ac.cn/spms/detail.php?id=bdb443a6).

A. adenophora seedlings were cultivated in greenhouse facilities at Yunnan Agricultural University under natural illumination (70–90%) and temperature conditions (22–28 °C) in Kunming County, Yunnan Province, China, in 2024 (25°N, 102°E). All chemicals utilized were of analytical grade. MEIAA was purchased from Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and IAA was sourced from Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Cell wall components determination

At 1, 3, and 5 days post-treatment, both straight and curved stem tissues were collected, oven-dried at 55 °C until reaching constant weight, ground into fine powder using a mortar and pestle, sieved through a 40-mesh screen (pore size: 0.425 × 0.425 mm), and stored in airtight desiccators to prevent moisture absorption. These processed samples were subsequently used for quantification of primary cell wall components.

Lignin content was quantified following the method of Ren et al. [26] with minor modifications. Briefly, 50 mg of dried stem powder was mixed with 2.5 mL of 25% acetyl bromide-glacial acetic acid solution (v/v = 1:3) and 0.1 mL of 70% perchloric acid in a glass tube. The mixture was incubated at 70 °C for 30 min with intermittent shaking every 10 min. After cooling, 10 mL of 2 mol·L−1 NaOH was added, and the volume was adjusted to 25 mL with glacial acetic acid. The solution was centrifuged at 1,000×g for 5 min, and absorbance was measured at 280 nm. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Cellulose content was determined based on Wang et al. [27] with adjustments. Dried stem powder (100 mg) was hydrolyzed in 30 mL of 50% H2SO4 under cold water bath conditions, followed by boiling for 20 min. After cooling, the volume was adjusted to 50 mL with 50% H2SO4. A 2.5 mL aliquot of the supernatant was diluted to 25 mL with distilled water. Subsequently, 2 mL of the diluted solution was mixed with 0.5 mL of 2% an throne reagent and 5 mL of concentrated H2SO4, boiled for 5 min, and cooled. Absorbance was measured at 620 nm. Cellulose content was calculated using a cellulose standard (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Triplicate measurements were performed.

Hemicellulose content was measured using a commercial hemicellulose assay kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). According to the manufacturer’s protocol, 50 mg of powdered sample was mixed with 1 mL of elution buffer, vortexed thoroughly, and incubated in a 90 °C water bath for 10 min. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded to retain the pellet. The pellet was washed three times with 1 mL of distilled water, followed by centrifugation under the aforementioned conditions. The washed pellet was dried to constant weight, then re-suspended in 0.5 mL of extraction buffer A, homogenized by vortexing, and incubated at 90 °C for 60 min. After cooling to room temperature, 0.5 mL of extraction buffer B was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube, mixed with 0.08 mL of chromogenic reagent and 0.16 mL of distilled water, incubated at 90 °C for 5 min, and cooled to room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm. Three biological replicates were conducted to ensure reliability and repeatability.

Pectin content was determined following Chen et al. [28] with modifications. Briefly, 1,000 mg of fresh stem tissue was homogenized into a slurry, mixed with 25 mL of 95% ethanol, and boiled for 30 min to remove soluble sugars and impurities. After cooling to 25 °C, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 15 min, and the supernatant was discarded. This ethanol extraction step was repeated three times. The resulting pellet was re-suspended in 20 mL of distilled water, incubated at 50 °C for 30 min to solubilize water-soluble pectin (WSP), and centrifuged (12,000 ×g, 15 min). The supernatant (WSP fraction) was mixed with 6 mL of concentrated H₂SO₄, boiled for 20 min, cooled, and reacted with 0.2 mL of 1.5 g/L carbazole-ethanol solution. After 30 min of dark incubation, absorbance at 530 nm was measured. For protopectin (water-insoluble pectin, WIP) quantification, the ethanol-washed pellet was hydrolyzed with 25 mL of 0.5 mol·L−1 H₂SO₄ at 100 °C for 60 min. The hydrolysate was centrifuged (12,000 ×g, 15 min), and the supernatant was treated as above (H₂SO₄ boiling, carbazole reaction). Total pectin content was calculated as WSP + WIP using a galacturonic acid standard calibration curve (0–200 µg/mL, R² > 0.99). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the experimental procedures were meticulously repeated in triplicate.

Paraffin section observation

The paraffin section preparation method was improved based on Li et al. [24]with specific procedures as follows: Curved stem samples of A. adenophora were fixed in FAA (37% formaldehyde, glacial acetic acid, 70% ethanol; 1:1:18 v: v:v) for 48 h at 4 °C. The fixed tissues were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (70%, 85%, 95%, and 100%), cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax using embedding molds. Tissue blocks were sectioned into 8–10 μm slices using a rotary microtome (RM2015, Leica, Germany). Sections were de-waxed in xylene, rehydrated through a descending ethanol gradient, and stained with 1% safranin O. After rinsing with distilled water, sections were briefly washed with 1% acetic acid to remove excess stain, followed by counterstaining with 0.5% fast green FCF. The stained sections were rinsed with tap water, dehydrated through an ascending ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted with neutral resin mounting medium (Catalog No. 10004160, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Shanghai, China). Morphological observations were conducted using an Olympus BX43 upright microscope (Tokyo, Japan). Images were captured with a Nikon DS-U3 digital camera system and processed using NIS-Elements BR imaging software (Nikon, Japan).

Observation of Ultra-structure in curved stems via transmission Electron microscopy (TEM)

After 3 days of post-MEIAA treatment, target tissue segments (about 1–2 mm in length) were randomly collected from treated plants. Tissues were immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4) overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, they were washed three times with 0.1 M PBS (15 min each). And then, the samples were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO₄, dissolved in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature under light-protected conditions, and washed again with 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4; 3 × 15 min). The samples were dehydrated with a graded ethanol series 30–100% (20 min per step), and dehydration in absolute acetone two times (15 min each) [29]. Finally, the samples were infiltrated and embedded in Epon 812 epoxy resin overnight, and then 60–80 nm ultrathin sections were obtained using an ultra-microtome (UC7 LEICA, Germany) and observed in a transmission electron microscope (TEM, Hitachi, Japan).

Extraction of metabolites and metabolomics analysis

The extraction of metabolites from A. adenophora stems was conducted following the method described by Zhang et al. [30] with slight modifications. Firstly, 50 mg of stem powder was weighed and mixed with 1.2 mL of −20 °C pre-cooled 70% methanol (Merck, Germany) aqueous solution containing internal standards. The mixture was thoroughly homogenized by vortexing for 30 s every 30 min, repeated six times in total. Subsequently, the solution was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 3 min. The supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm microporous membrane for UPLC-MS/MS (ExionLC™ AD) analysis. The acquired UPLC-MS/MS data were annotated using the MetMep database and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) online database. Differential metabolites were screened based on the following criteria: VIP > 1 and FC ≤ 0.5 or FC ≥ 2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and metabolic pathway analysis were performed using R software (www.r-project.org).

Preparation of cDNA library and transcriptome sequencing analysis

The total RNA from A. adenophora stems was extracted using the MiniBEST Plant RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Japan), and cDNA libraries were constructed. After passing quality control, sequencing was performed on the Illumina platform. Raw sequencing data were filtered to obtain high-quality reads, which were assembled into transcript sequences using Trinity [31]. The longest cluster sequences generated through Corset hierarchical clustering were defined as unigenes for downstream analysis [32]. Unigene sequences were annotated by aligning against the NCBI non-redundant protein database (Nr), KEGG, Gene Ontology (GO), Swiss-Prot, Pfam, eukaryotic orthologous groups (KOG), and Trembl databases using DIAMOND BLASTX software [33]. Using RSEM software, clean reads from each sample were mapped to the reference sequences (Trinity-assembled transcripts after redundancy removal) [34]. Gene expression levels were quantified as FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified with thresholds of |log₂FoldChange| > 1 and a significance threshold of P < 0.05. These DEGs were subsequently subjected to GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. Finally, integrated analysis with metabolomic data was conducted.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction verification

Reverse transcribed cDNA was used to perform real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to validate the RNA-seq data. RT-qPCR was performed on a Rotor Gene-Q real-time PCR system (QIAGEN, Germany) using SYBR™ qPCR Kit (BIOGROUND, Chongqing, China). The total sample volume of 20 µL (10 µL of 2 × SP qPCR Mix, 1 µL of primers, 1 µL of cDNA, and 8 µL of ddH2O). The thermal cycling protocol included: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 10 s, 50–60 °C (primer-specific annealing) for 10 s, and 72 °C for 10 s. β-Actin served as an internal control for normalizing gene expression levels. The relative expression of per DEGs was evaluated by the 2−ΔΔCt method of Livak et al. [35] For each gene and sample, three biological and three technical replicates were used. Primer sequences were listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The metabolite assay and the RNA-Seq assay were determined in triplicates for each treatment. Image composites were processed in Adobe Photoshop 2020 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Column charts and pie diagrams were generated using Origin 2021 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). Statistical analysis of cell wall composition data was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test was employed to determine significant differences among experimental groups at three significance levels: P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001. All results were expressed as the mean ± SE from three replicates. Pathway-specific heat maps were created with Tbtools [36], while integrated pathway heat map visualizations were finalized using Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Results

Inhibition effects of MEIAA on the stems of A. adenophora

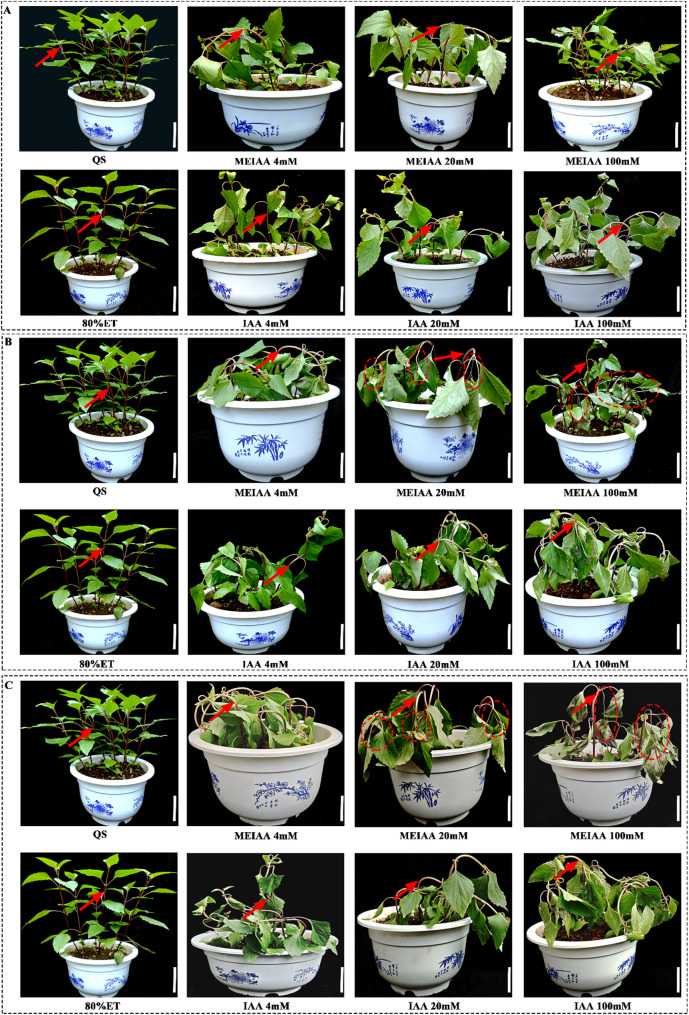

A. adenophora plants were foliar-sprayed with MEIAA solutions at 4, 20, and 100 mM concentrations, using equivalent gradient concentrations of IAA as positive controls. Stem curvature was observed at 1 d across all treatments, with phenotypic analysis revealing dose- and time-dependent escalation of bending angles. Notably, the bending degree of MEIAA treatment was more significant than that of IAA control at corresponding concentrations (Fig. 1). Advanced phytotoxic effects manifested in 20 and 100 mM MEIAA treatments by 3 d, characterized by apical meristem necrosis accompanied by wilting and tissue collapse (Fig. 1). These results showed that MEIAA had a concentration-dependent inhibitory effect on A. adenophora morphogenesis, primarily through induction of stem curl and apical meristem necrosis accompanied by wilting and tissue collapse.

Fig. 1.

Contrast of straight and bending stems in A. adenophora under differential treatments (Scale bar = 15 cm). A-C The phenotypic of the straight and bending stem at 1, 3, and 5 days post-treatment. QS: Water control; 80% ET: 80% Ethanol solvent control; IAA: Indole-3-acetic acid positive control; MEIAA: Methyl indole-3-acetic acid treatment. Red arrows indicate loci of treatment-induced histomorphological anomalies. Dashed circles demarcate lesion development zones

Subsequent investigations employed 20 mM MEIAA treatment as the optimal concentration, given that lower concentrations (4 mM) exclusively induced stem curvature without manifesting complete phytotoxic effects, while higher concentrations (100 mM) were excluded due to risks of nonspecific phytotoxicity potentially confounding experimental outcomes.

Histoogical effects and Ultra-structulral damage

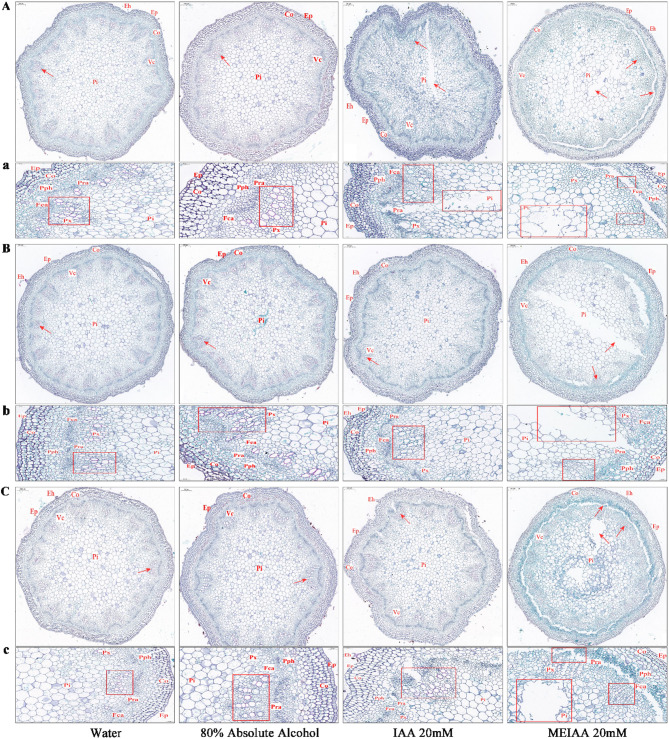

In the control groups (QS and 80% ET), the transverse sections cellular structure of A. adenophora stems exhibited well-organized layers from the exterior to the interior: epidermis, cortex, vascular bundles, and pith (Fig. 2). The cells were uniformly arranged, with cellulose stained green by Fast Green visible within the cells. Well-developed vessels were observed in the vascular bundles, arranged in a single row of 5–6 cells. The cell walls stained red with Safranin, indicating high lignin content. However, the bent stem sections treated with MEIAA (20 mM) for 1, 3, and 5 days displayed varying degrees of structural damage: cells from the vascular bundles to the pith showed loose and deformed arrangements, accompanied by gaps and cavities (Fig. 2). The staining intensity of vessel cells gradually faded, with some exhibiting faint or absent staining, suggesting a reduction in lignin content. Although bending-induced damage was also observed in IAA-control stems, the severity was less pronounced compared to MEIAA.

Fig. 2.

Defective cellular growth and development in MEIAA-treated stems of A. adenophora. A-C Cross-sectional views of stems treated for 1, 3, and 5 days, respectively (Scale bar = 100 μm). a-c: Magnified views of boxed regions (Scale bar = 50 μm). Eh: Epidermal hair; Ep: Epidermis; Co: Cortex; Vc: Vascular cylinder; Pi: Pith; Pph: Primary phloem; Fca: Fascicular cambium; Pra: Pith ray; Px: Primary xylem. Red boxes indicate magnified regions corresponding to the red arrows, highlighting the staining intensity of vessels and structural damage in cellular organization

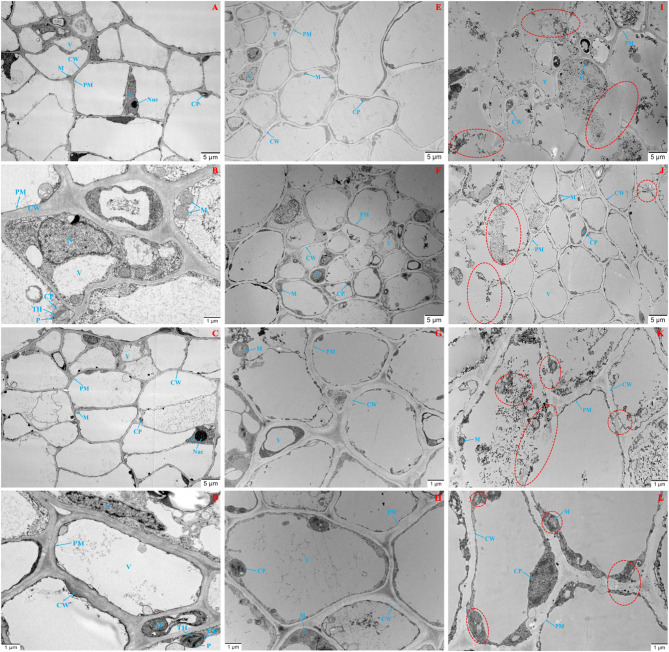

The ultra-structure of cells at target sites was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 3). In the control groups (QS and 80% ET), no cell wall rupture or organelle deformation was detected under both low and high magnification. The stem cells exhibited well-organized arrangements, with smooth and intact cell walls, intact plasma membranes, clearly defined nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and typical mitochondria (round or oval in shape). Chloroplasts displayed an elliptical morphology, with well-developed thylakoid membranes, plastids, and grana lamellae arranged in an orderly manner (Fig. 3A-D). In IAA-control bent stems, partial damage to cell walls and plasma membranes was observed, though cellular morphology was largely maintained. Mild plasmolysis occurred, and nuclei, chloroplasts, and mitochondria showed slight deformation but remained identifiable (Fig. 3E-H). In contrast, MEIAA-treated stems exhibited severe organelle degradation and disintegration. Pronounced plasmolysis, fragmented or lysed cell walls, and disorganized cell arrangements were observed. Un-degraded chloroplasts and mitochondria were markedly damaged: mitochondrial cristae were blurred or absent, thylakoid membranes were ruptured and disorganized, and grana lamellae were partially degraded or missing. Additionally, many black deposits appeared inside the cell under MEIAA treatment, indicating that the cell wall and organelles probably degraded (Fig. 3I-L). These results demonstrated that MEIAA had a strong destructive influence on the integrity of cell wall and organelles in A. adenophora cells.

Fig. 3.

MEIAA disrupts vascular cell integrity in stems. A, B Water control; C, D: 80% anhydrous ethanol solvent control; E-H: 20 mM IAA positive control; I-L: 20 mM MEIAA treatment. CW: Cell wall; PM: Plasma membrane; N: Nucleus; Nue: Nucleolus; V: Vacuole; M: Mitochondria; CP: Chloroplast; P: Plastoglobule; TH: Thylakoid. Red circles indicate structural alterations in cell walls and organelles under MEIAA treatment. Scale bar of 5 μm (A, C, E, F, I, J); Scale bar of 1 μm (B, D, G, H, K, L)

Cell wall composition

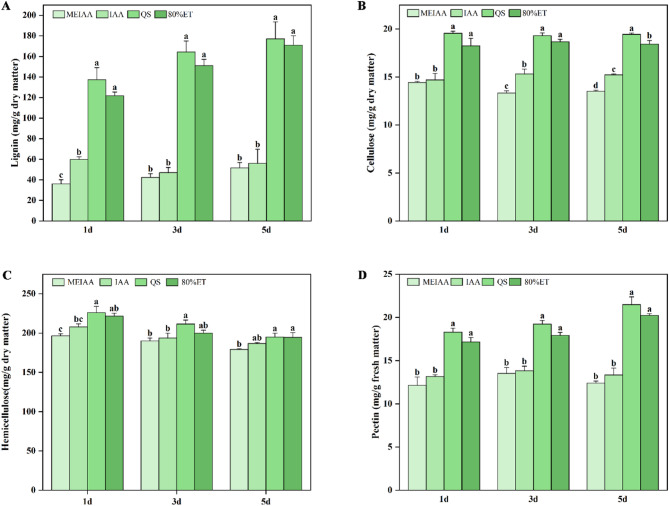

As shown in Fig. 4, MEIAA induced a significant decrease in the content of critical cell wall components (lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin) within bent stems, thereby validating our initial hypothesis. Notably, the suppressive effects of MEIAA on lignin and cellulose biosynthesis differed significantly from those of IAA at specific treatment intervals.

Fig. 4.

MEIAA reduced the levels of key components in the cell walls of A. adenophora stems. A-D The contents of Lignin (A), Cellulose (B), Hemicellulose (C), Pectin (D), respectively. Data from three biological replicates were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 3). Error bars represent the SEs from three parallel samples. Different letters within the same time period indicate significant differences at p < 0.05

MEIAA strongly influenced the transcription of key driver genes related to multiple metabolism

Based on the reference transcriptome dataset, RNA sequencing and transcriptomic analysis were performed on 12 samples from A. adenophora treated with QS, 80% ET, IAA, and MEIAA (20 mM) for 3 days. The sequencing data met the quality criteria for downstream analysis (Supplemental Table S2, Supplemental Fig. 1 A). Clear separation was observed between treatment and control groups (Supplemental Fig. 1B), with highly divergent gene expression profiles between bent and erect stems (Supplemental Fig. 1C-E). GO enrichment analysis revealed that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in MEIAA-treated bent stems were predominantly enriched in biological processes such as cellular processes, metabolic processes, and response to stimuli, as well as molecular functions including binding and catalytic activity, and cellular components like cellular anatomical entities (Supplemental Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 3). KEGG pathway analysis further demonstrated that MEIAA significantly regulated DEGs involved in: Plant hormone signal transduction; Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis; Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis - ganglio series; Galactose metabolism; Ether lipid metabolism; Circadian rhythm - plant; Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism; Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism; Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (Supplemental Fig. 3, Supplemental Table 4). These transcriptional changes align with the metabolomics findings, indicating coordinated metabolic and genetic reprogramming under MEIAA treatment.

MEIAA induced profound changes in the stem metabolome

Untargeted metabolomics analysis revealed that MEIAA induced significant alterations in the metabolite composition of bent stems in A. adenophora. A total of 1,613 metabolites were detected (Supplemental Fig. 4 A). Principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated clear separation between MEIAA-treated bent stems and control stems (Supplemental Fig. 4B), with hierarchical clustering analysis of metabolites showing a similar trend (Supplemental Fig. 4 C). Further analysis indicated that MEIAA markedly altered the profiles of flavonoids, phenolic acids, alkaloids, lipids, amino acids and derivatives, lignin’s and coumarins in bent stems (Supplemental Fig. 5A-C, Supplemental Table 5). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified 12 metabolic pathways significantly perturbed by MEIAA, including: Galactose metabolism; Starch and sucrose metabolism; Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis; Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis; Kaempferol aglycone II biosynthesis; Sphingolipid metabolism; Fructose and mannose metabolism; Indole alkaloid biosynthesis; Propanoate metabolism; Diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis; Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis and ABC transporters (Supplemental Fig. 5D-H, Supplemental Table 6).

Transcriptomic and metabolic disruptions

Correlation analysis between DEMs and DEGs

The correlation nine-quadrant diagram characterizes the association between DEGs and DEMs in curved stems (filtering criteria: Pearson|correlation coefficient| >0.8 and p-value < 0.05). The results indicate that metabolites showing differential expression in curved stems are positively regulated by differentially expressed genes (Supplemental Fig. 6A-E). KEGG enrichment analysis shown that MEIAA treatment significantly affected carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, and secondary metabolic pathways in A. adenophora stems (Supplemental Fig. 7, Supplemental Table 7).

Critical pathway analysis

Based on the integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses, we constructed three metabolic pathways associated with key biological processes in MEIAA-induced curved stems, including carbohydrate metabolism, phenylpropanoid metabolism, and plant hormone signal transduction pathways.

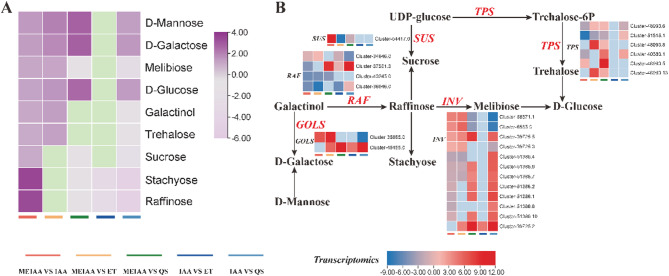

In carbohydrate metabolism, MEIAA significantly altered three sugar metabolic pathways in A. adenophora stems: fructose and mannose metabolism, galactose metabolism, and starch and sucrose metabolism, involving nine metabolites: three monosaccharides (D-mannose, D-galactose, and D-glucose), three disaccharides (melibiose, trehalose, and sucrose), and two oligosaccharides (stachyose and raffinose), and one sugar alcohol (Fig. 5, Supplemental Table 8). Elevated D-mannose levels simultaneously influenced both galactose metabolism and fructose/mannose pathways. Increased D-galactose, galactitol, raffinose, melibiose, and D-glucose further disrupted galactose metabolism. Notably, most DEGs encoding 3-α-galactosyltransferase (GOLS) and β-fructofuranosidase (INV) were upregulated, while DEGs for raffinose synthase (RAF) showed mixed expression (up- and down-regulated). Elevated sucrose, D-glucose, and trehalose levels altered starch/sucrose metabolism. DEGs encoding sucrose synthase (SUS) and trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS) exhibited both up- and down-regulation.

Fig. 5.

MEIAA disrupts carbohydrate metabolism in stems. A The expression patterns of the 9 differential metabolites (ranging from light purple for low to dark purple for high). B The expression patterns of genes involved in carbohydrate biosynthesis regulation (gene expression levels are represented by a color gradient from blue for low to red for high). The heatmap was plotted using log2-transformed fold-change values

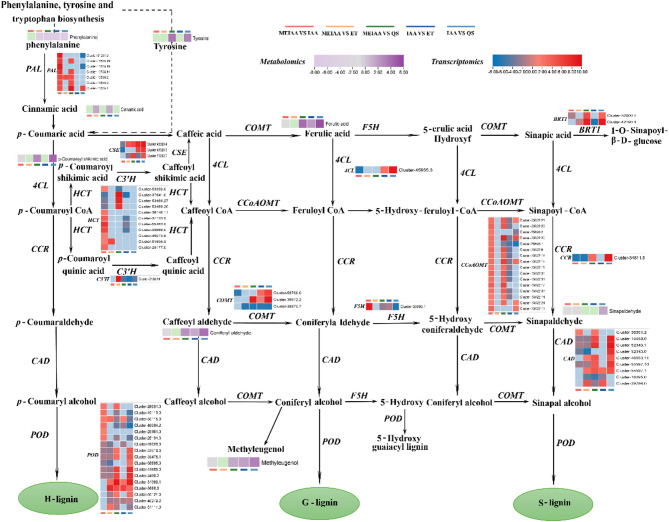

In the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, MEIAA treatment significantly suppressed the accumulation of six critical metabolites compared to IAA and 80% ET controls: phenylalanine, ferulic acid, p-coumaroyl shikimate, coniferaldehyde, sinapaldehyde, and methyleugenol (Fig. 6, Supplemental Table 9). Concurrently, MEIAA induced divergent regulation of genes encoding key biosynthetic enzymes: Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), Ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H), Sinapoylglucose 1-glucosyltransferase (BRT1), Caffeoylshikimate esterase (CSE), Shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase (HCT), Caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT), Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), Peroxidase (POD) were significantly upregulated; Caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase (COMT), 4-Coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), 5-O-(4-Coumaroyl)-D-quinate 3ʹ-monooxygenase (C3’H), Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) were significantly downregulated. This bidirectional regulation suggests MEIAA disrupts lignin biosynthesis by redirecting metabolic flux toward early phenylpropanoid intermediates while suppressing downstream lignin polymerization steps.

Fig. 6.

MEIAA disrupts the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway in stems. The DEMs and DEGs are positioned adjacent to their corresponding metabolites and enzymes in the pathway diagram. Metabolite expression levels are color-coded from low in light purple to high dark purple, while gene expression levels are indicated by blue (low) and red (high) gradients. The heatmap was plotted using log2-transformed fold-change values

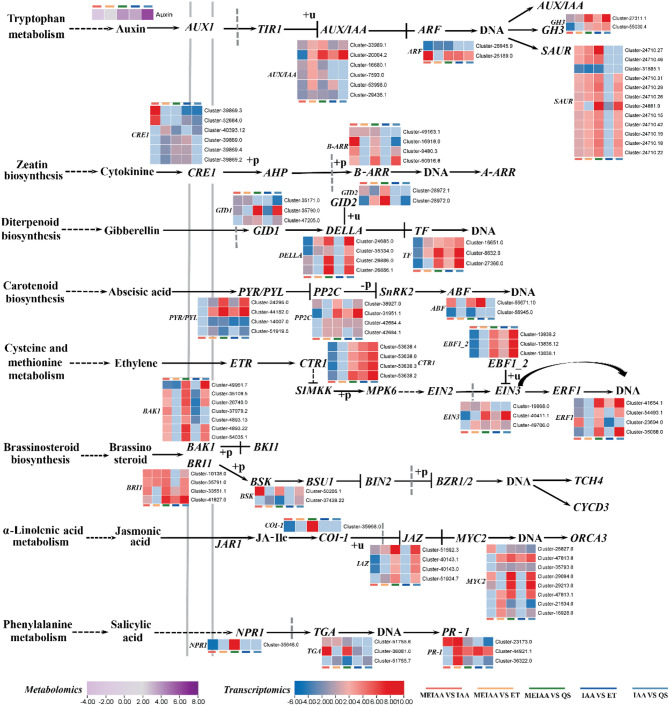

MEIAA modulated the expression of 26 genes associated with auxin (IAA), cytokinin (CK), gibberellin (GA), abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene (ETH), brassinosteroid (BR), jasmonic acid (JA), and salicylic acid (SA) signaling pathways (Fig. 7, Supplemental Table 10). These include: 4 auxin DEGs (AUX/IAA, ARF, GH3 and SAUR); 2 cytokinin DEGs (CRE1 and B-ARR); 4 gibberellin DEGs (GID1, GID2, DELLA and TF); 3 abscisic acid DEGs (PYR/PYL, PP2C and ABF); 4 ethylene based DEGs (CTR1, EIN3, EBF½ and ERF1); 3 brassinosteroid DEGs (BAK1, BRI1 and BSK); 3 jasmonic acid DEGs (COI-1, JAZ and MYC2) and 3 salicylic acid DEGs (NPR1, TGA and PR-1). These results demonstrate that MEIAA exhibits varying intensities of interaction effects with differentially expressed genes, and its regulatory mode diverges distinctly from IAA controls.

Fig. 7.

MEIAA disrupts plant hormone signal transduction in stems. The DEMs and DEGs are positioned adjacent to their corresponding metabolites and genes, respectively. Metabolite expression levels are color-coded from light purple (low) to dark purple (high), while gene expression levels are indicated by blue (low) and red (high) gradients. The heatmap was plotted using log2-transformed fold-change values

Validation of the DEGs results by qRT-PCR analysis

To validate the reliability of the RNA-seq data, we selected 19 DEGs related to carbohydrate metabolism, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and plant hormone signal transduction for qRT-PCR verification. These results showed that the similar expression trends of selected DEGs were consistent with the Illumina sequencing (Supplemental Fig. 8), indicating the dependability of the RNA-Seq data.

Discussion

MEIAA disrupted the vascular system in the stems of A. adenophora

As a critical supporting organ in plant development, stems are essential for morphological maintenance and nutrient transport [23]. Under certain concentration conditions, MEIAA can induce stem bending in A. adenophora, with the degree of curvature intensifying as the treatment concentration and duration increase. High concentrations (20 and 100 mM) may even cause wilting, softening, and necrosis of the weed’s growing points (Fig. 1). Moreover, in the curved stem sections, we observed that MEIAA exerted a strong destructive effect on the vascular tissues and cells of A. adenophora stems. This was manifested as loosening and deformation of vascular bundles and pith cells, along with evident cavitation and structural damage in the tissue (Fig. 2). Simultaneously, the cell walls exhibited significant rupture or complete dissolution, accompanied by severe plasmolysis. Organelles such as nuclei, mitochondria, and chloroplasts were also severely damaged (Fig. 3). The primary mechanism by which auxin-like herbicides cause plant death is the excessive stimulation of plant tissues or organs by high doses of auxin, which suppresses metabolism and growth, leading to phytotoxic effects [14, 37]. This metabolic-physiological process can be divided into three stages: stimulation phase (activation of metabolic processes, including leaf epinasty, tissue swelling, and stem curling); growth inhibition phase (suppression of root and shoot growth, stomatal closure, reduced carbon assimilation and starch formation, and excessive ROS production); and senescence and tissue decay phase (accelerated leaf senescence, chloroplast damage, and loss of membrane and vascular system integrity) [13, 14, 38]. Based on our findings, the phytotoxicity of MEIAA on A. adenophora stems exhibits a concentration-dependent effect, and its physiological progression aligns with that of auxin-like herbicides. Therefore, we conclude that MEIAA possesses potential herbicidal activity.

It has been reported that damage to chloroplast ultrastructure can inhibit chlorophyll synthase activity, accelerate chlorophyll degradation, and impair chloroplast functionality, thereby disrupting photosynthesis [39]. Chloroplasts are rich in to copherols and carotenoids, which effectively quench ¹O₂ and scavenge lipid peroxides [40]. Beyond light harvesting, carotenoids play a critical role in protecting photosynthetic apparatus from photooxidation, serving as potent antioxidants [41]. Mitochondria, key organelles for photosynthesis and energy metabolism, also mediate antioxidant defense via ascorbate (AsA) synthesis, structural damage to mitochondria significantly reduces photosynthetic efficiency and energy supply, thereby inhibiting plant growth [42]. Furthermore, thylakoid and thylakoid membrane damage suppresses light-dependent reactions and diminishes photosynthetic efficiency [29]. We speculate that MEIAA disrupts the structure of chloroplasts and mitochondria while simultaneously impairing photosynthesis, antioxidant activity, and energy supply in the stems.

The plant cell wall is a hetero-polymer composite network primarily composed of cellulose, non-cellulosic polysaccharides (mainly hemicellulose and pectin), and lignin [43]. It regulates vascular bundle development, determines cell shape and size, and provides mechanical support and protective barriers for plant growth through complex molecular mechanisms [43–45]. In growing cells, the wall typically exists as a thin, flexible layer that compresses and shapes the protoplast [46, 47]. Without cell walls, plants would be amorphous protoplasmic masses, unable to develop the diverse morphologies observed in nature [48]. Thus, we propose that MEIAA likely degrades the cell walls in A. adenophora stems, disrupting the rigid protoplast enclosure. This exposes critical intracellular organelles to external attacks, impairing their normal functions. The subsequent collapse of the plant’s transport systems blocks water and nutrient translocation, ultimately causing wilting, shrinkage, and necrosis at growth points. At the same time as, MEIAA treatment significantly reduced lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin content in bent stems (Fig. 4). Histochemical staining revealed that lignin reduction predominantly occurred in vessel cells of vascular bundles, while cellulose depletion was most evident in parenchyma tissues (Fig. 2). Lignin, a heterogeneous phenolic polymer derived from oxidative polymerization of hydroxycinnamyl alcohols, deposits in secondary cell walls of vascular plants, conferring mechanical strength and rigidity. It facilitates xylem vessel formation and long-distance water and nutrient transport [49–51]. Numerous studies have confirmed its critical role in stem rigidity [18, 52–55]. Cellulose, composed of β−1,4-glucan chains forming crystalline microfibrils via hydrogen bonds, provides strength, flexibility, and resistance to degradation [56, 57]. Inhibiting cellulose biosynthesis weakens cell wall rigidity, leading to growth abnormalities or death [58, 59]. Isoxaben, a known cellulose biosynthesis inhibitor, exemplifies herbicide efficacy through cell wall damage (CWD), altering wall composition and structure [60, 61]. Hemicellulose binds covalently to cellulose, lignin, pectin, and phenolic compounds, forming a constrained network [62, 63]. Pectin acts as a cross-linker within the xyloglucan-cellulose microfibril framework, maintaining wall integrity and mechanical support [22]. Depolymerization or degradation of these components is a key contributor to stem bending [22, 64]. Mechanical support in stems primarily relies on vascular bundles, whose strength depends on cell wall composition. In our study, MEIAA not only disrupted vascular structures in A. adenophora stems but also reduced key cell wall components (lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin). We postulate that MEIAA compromises vascular cell wall integrity and intracellular organelle structure, triggering vascular collapse. This likely paralyzes the synthesis and storage of these components, leading to degradation of existing cell wall materials and failure to produce new ones. The most direct manifestation is the observed decline in their content, ultimately crippling stem development and function.

MEIAA disrupts core metabolic processes in the stems of A. adenophora

MEIAA disrupts carbohydrate metabolism in stems

Carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis serve as building blocks and energy sources for plant biomass production and maintenance [65]. Soluble sugars are closely linked to photosynthesis, mitochondrial respiration, and fatty acid β-oxidation, playing critical roles in maintaining cellular redox balance-processes inherently tied to oxidative metabolism in chloroplasts, mitochondria, and peroxisomes [66]. In this study, MEIAA treatment triggered significant accumulation of monosaccharides (D-mannose, D-galactose, and D-glucose), disaccharides (melibiose, trehalose, and sucrose), and oligosaccharides (stachyose and raffinose) in bent stems (Fig. 5, Supplemental Table 8). D-glucose, a fundamental product of photosynthesis, is the preferred carbon and energy source for plants [67]. D-mannose and D-galactose act as ROS scavengers, protecting plant cells from oxidative damage [68]. Sucrose, trehalose, and raffinose are key water-soluble carbohydrates. Sucrose, composed of D-glucose and D-fructose, is the primary photosynthetic product and is integral to plant growth, development, storage, signaling, and stress mitigation [69]. When extended by galactosyl groups, it is further converted into raffinose and stachyose in the cytoplasm [70]. As a non-structural carbohydrate, sucrose not only supplies substrates for cellulose synthesis but also provides carbon skeletons for lignin biosynthesis [71]. MEIAA treatment induced marked sucrose accumulation in bent stems (Fig. 5, Supplemental Table 8), suggesting a strong positive correlation with sucrose biosynthesis. Typically, elevated sucrose levels accelerate lignin and cellulose production. However, in this study, lignin and cellulose content in MEIAA-treated bent stems decreased rather than increased (Fig. 4A and B). Pectin, synthesized in the Golgi apparatus, promotes cell wall thickening and enhances stem elasticity [64]. Additionally, stem cell wall integrity and mechanical strength are positively correlated with cellulose content [22]. Trehalose functions as an osmoprotectant at sufficient levels, stabilizing proteins and membranes [72]. Although trehalose is scarce in most angiosperms, abiotic stress moderately elevates its abundance [73]. These results indicate that MEIAA disrupts both stem cell structure and carbohydrate metabolism in A. adenophora, collectively driving stem bending.

MEIAA disrupts with phenylpropanoid metabolism in stems

The shikimate pathway generates phenylalanine, initiating the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoid metabolism. This process is further mediated by enzymatic modifications including acylation, methylation, glycosylation, and hydroxylation catalyzed by oxygenases, oxidoreductases, ligases, and various transferases [74]. Spanning the boundary between core and specialized metabolism, this pathway channels metabolic flux from primary to specialized metabolism [75], ultimately diverging into two major classes of end products: flavonoids and lignin [76]. In this study, MEIAA not only altered the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway in stems of A. adenophora but also modified downstream flavonoid metabolism (Supplemental Fig. 3, Supplemental Table 7). Vascular plants require lignin to provide mechanical strength, rigidity, and hydrophobicity to cell walls, facilitating xylem vessel formation and enabling long-distance water/nutrient transport critical for growth and development [50]. Native lignin polymers comprise three monolignol-derived units: p-hydroxyphenyl (H), guaiacyl (G), and syringyl (S), synthesized from p-coumaryl, coniferyl, and sinapyl alcohols, respectively [50]. These monolignols are produced via the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway in the cytoplasm, transported to secondary cell walls by specific transporters, and polymerized into lignin by POD or LAC [51]. Lignin deposition in cell walls confers compressive strength. MEIAA treatment induced stem bending in A. adenophora, indicating compromised mechanical integrity. Our prior work demonstrated MEIAA-induced lignin reduction in stems, consistent with weakened structural support. Here, MEIAA suppressed 6 phenylpropanoid metabolites: phenylalanine, ferulic acid, p-coumaroyl shikimate, coniferaldehyde, sinapaldehyde, and methyleugenol. It concurrently altered expression patterns of 12 DEGs encoding key enzymes: PAL, COMT, F5H, BRT1, 4CL, CSE, HCT, C3H, CCoAOMT, CCR, CAD, and POD (Fig. 6, Supplemental Table 9). These perturbations suggest MEIAA likely disrupts vascular system integrity in A. adenophora stems, impairing organelle function required for phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. This cascade inhibits lignin production, weakens cell wall reinforcement, and ultimately manifests as stem curvature.

MEIAA disrupts with plant hormone signal transduction in stems

Here, both MEIAA and IAA induced stem curvature in A. adenophora, but the degree of bending differed significantly between the two treatments (Fig. 1). MEIAA notably reduced auxin (IAA) content in curved stems, indicating distinct mechanistic pathways underlying their bending effects (Fig. 7, Supplemental Table 10). Furthermore, MEIAA triggered substantial differential expression of genes involved in phytohormone signaling transduction pathways, including auxin (IAA), cytokinin (CK), gibberellin (GA), abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene (ETH), brassinosteroid (BR), jasmonic acid (JA), and salicylic acid (SA) (Fig. 7, Supplemental Table 10). These findings suggest active involvement of these signaling pathways during stem curvature. We hypothesized that MEIAA interacts with these hormones to induce stem bending in A. adenophora, compromising cellular integrity in the vascular system, disrupting water/nutrient transport, and ultimately leading to dehydration, wilting, and necrosis of apical meristems. Plant hormone are naturally occurring small organic signaling molecules that play crucial roles in coordinating environmental cues with developmental programs at ultralow concentrations [77], and exert decisive control over cell differentiation and cell wall biosynthesis [78]. Conversely, cell wall defects can reciprocally alter phytohormone signaling [79]. For instance, disruptions such as pectin modification and xyloglucan alterations have been shown to stimulate BR signaling while IAA responses [79, 80]. In this study, MEIAA suppressed pectin content in cell walls (Fig. 4D), suggesting that abnormal pectin biosynthesis may also partially interfere with IAA and BR signal transduction in stems.

Phytohormone crosstalk critically regulates plant growth and development. For instance, Aux/IAA, a short-lived transcriptional repressors, inhibit ARF under low auxin concentrations [81]. GH3 genes encode IAA-amido synthetases that conjugate excess IAA with amino acids, thereby maintaining auxin homeostasis [82]. The GA-GID1-DELLA module serves as a central regulatory hub, integrating internal signals from other hormonal pathways (auxin, abscisic acid, jasmonic acid, and ethylene) with external environmental cues to coordinate developmental processes [83, 84]. Furthermore, both ABA and ET function as natural senescence promoters—endogenous ABA levels and transcript abundance of ABA-signaling genes increase progressively with plant age [85]. Phytohormones have been reported to regulate plant lignification. For instance, overexpression of PtoARF5.1 and PtoIAA9m (encoding stabilized IAA9 proteins) suppresses the expression of genes involved in lignin deposition and secondary xylem development (e.g., PAL4 and WND1B), thereby inhibiting secondary xylem formation [86]. Additionally, gibberellins (GAs) play critical roles in promoting xylem formation and lignification while suppressing starch biosynthesis [87].

This study demonstrates that MEIAA disrupts auxin homeostasis in stems and perturbs the expression patterns of genes associated with diverse phytohormone signaling transduction pathways. Given the pervasive involvement of plant hormones in virtually all aspects of cellular growth and development—coupled with our prior findings—we hypothesize that dysregulation of these hormonal pathways directly correlates with aberrant growth of vascular cells, triggering a cascade of downstream effects. Collectively, MEIAA-induced stem curvature and apical necrosis in A. adenophora involve multifaceted physiological disruptions. Further investigation is required to determine whether these phenomena arise from the isolated action of a single hormone or represent a systemic consequence of imbalanced crosstalk among critical hormonal networks.

Conclusion

This study systematically elucidates the mechanism by which MEIAA induces stem curvature and apical meristem necrosis in A. adenophora through integrated analyses. The results demonstrate that MEIAA triggers vascular collapse by reducing structural components (lignin, cellulose), disrupting cellular ultra-structure, and compromising organelle integrity. Concurrently, it dysregulates carbohydrate metabolism, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and phytohormone signaling, collectively impairing mechanical support and nutrient transport. These multi-target effects position MEIAA as a potent auxin-mimetic herbicide with distinct application potential for invasive species management: Its targeted foliar action and rapid induction of structural collapse (≤ 3 d) offer a precision tool against resilient perennials like A. adenophora in ecologically sensitive habitats where non-selective herbicides are contraindicated. Future research should prioritize (1) field validation of efficacy/safety in invaded ecosystems, (2) selectivity screening across agronomic crops, and (3) expanded phytotoxicity profiling against other invasive species sharing similar lignocellulosic architectures.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1. Specific primers for real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR (Table S1); Evaluation statistics of sequencing data from stem samples of A. adenophora (Table S2); GO enrichment analysis in the stems of A. adenophora (Table S3); KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the stems of A. adenophora (Table S4); The first four classes of DEMs in the stems of A. adenophora (Table S5); KEGG analysis of DEMs in the stems of A. adenophora (Table S6); Co-enriched pathways in transcriptomic and metabolomic data of A. adenophora stems (Table S7); Identification of carbohydrate metabolism-related DEGs and DEMs in MEIAA-induced curved stems of A. adenophora (Table S8); Identification of phenylpropanoid metabolism-related DEGs and DEMs in MEIAA-induced curved stems of A. adenophora (Table S9); Identification of plant hormone signal transduction-related DEGs and DEMs in MEIAA-induced curved stems of A. adenophora (Table S10). Analysis of DEGs between Upright and Bent Stems of A. adenophora (Fig. S1); GO Annotation of DEGs in MEIAA-treated bent stems of A. adenophora (Fig. S2); KEGG enrichment pathway analysis of DEGs in MEIAA-treated bent stems of A. adenophora (Fig. S3); Qualitative and quantitative analysis of metabolomic data in MEIAA-treated bent stems of A. adenophora (Fig. S4); MEIAA-treated bent stems of A. adenophora: DEMs and KEGG analysis (Fig. S5); Nine-quadrant correlation plot of transcriptome and metabolome in bent vs. upright stems (Fig. S6); Bar plot of KEGG enrichment analysis results for transcriptome and metabolome in bent vs. upright stems (Fig. S7); qRT-PCR validation of RNA Sequencing data accuracy (Fig. S8).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Statement

We declare that this study complies with all applicable local and national regulations governing the use of plants in research.

Abbreviations

- MEIAA

Methyl Indole-3-Acetate

- IAA

Indole-3-acetic acid

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- IAMT

IAA carboxyl methyltransferase

- SAM

S-adenosyl-L-methionine

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DEMs

Differentially expressed metabolites

- RT-qPCR

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Authors’ contributions

G.W., D.Q., and M.Y. conceived and designed the study. Y.R. performed the experiments and wrote the first draft of manuscript. M.H., X.G., X.Q., J.N., D.Y., and T.Z. assisted in the experiments. M.H. revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260704 and 32060639), the Reserve Talents Project for Yunnan Young and Middle-aged Academic and Technical Leaders (202105AC160037 and 202205AC160077), and Yunnan Province Agricultural Joint Special Key Project (202301BD070001-141).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. The raw transcriptome data have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under project accession number PRJNA1265656 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1265656).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our research did not involve any human or animal subjects, materials, or data. We hereby declare that the plant materials used in this study involved no endangered or protected species, and all biological sample collections were conducted in full compliance with China’s Regulations on the Protection of Wild Plants (2022 Revision) and the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Deqiang Qin, Email: peakqin@163.com.

Min Ye, Email: yeminpc@163.com.

Guoxing Wu, Email: wugx1@163.com.

References

- 1.Shrestha K, Wilson E, Gay H. Ecological and environmental study of Eupatorium Adenophorum sprengel (Banmara) with reference to its gall formation in Gorkha-Langtang route, Nepal. J Nat History Museum. 2008;23:108–24. 10.3126/jnhm.v23i0.1848. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng W, Jia G, Zhang J, Lin L, Cui M, Zhang D, Jiao M, Zhao X, Wang S, Dong J, et al. Transcriptome and metabolome analysis of the synthesis pathways of allelochemicals in Eupatorium adenophorum. ACS Omega. 2022;7(19):16803–16. 10.1021/acsomega.2c01816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun X, Lu Z, Sang W. Review on studies of Eupatorium adenophoruman important invasive species in China. J Forestry Res. 2004;15(4):319–22. 10.1007/BF02844961. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang C, Lin H, Feng Q, Jin C, Cao A, He L. A new strategy for the prevention and control of Eupatorium adenophorum under climate change in China. Sustainability. 2017;9(11):2037. 10.3390/su9112037. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian J, Li T, Mu L, Xia Y, Ji Q, Wang R. The Diversity and Natural Enemies of Eupatorium Adenophorum and Native Plants: In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Bioinformatics; SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications: Tianjin, China, 2022; pp 729–733. 10.5220/0011280900003443

- 6.Zubieta C, Ross JR, Koscheski P, Yang Y, Pichersky E, Noel JP. Structural basis for substrate recognition in the salicylic acid carboxyl methyltransferase family. Plant Cell. 2003;15(8):1704–16. 10.1105/tpc.014548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin G, Gu H, Zhao Y, Ma Z, Shi G, Yang Y, Pichersky E, Chen H, Liu M, Chen Z, et al. An indole-3-acetic acid carboxyl methyltransferase regulates Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Cell. 2005;17(10):2693–704. 10.1105/tpc.105.034959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbas M, Hernández-García J, Pollmann S, Samodelov SL, Kolb M, Friml J, Hammes UZ, Zurbriggen MD, Blázquez MA, Alabadí D. Auxin methylation is required for differential growth in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(26):6864–9. 10.1073/pnas.1806565115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Hou X, Tsuge T, Ding M, Aoyama T, Oka A, Gu H, Zhao Y, Qu L-J. The possible action mechanisms of Indole-3-acetic acid methyl ester in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27(3):575–84. 10.1007/s00299-007-0458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y, Xu R, Ma C, Vlot AC, Klessig DF, Pichersky E. Inactive methyl indole-3-acetic acid ester can be hydrolyzed and activated by several esterases belonging to the At MES esterase family of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(3):1034–45. 10.1104/pp.108.118224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Zhao Y, Dong B, Wang D, Hao J, Jia X, Zhao Y, Nian Y, Zhou H. The aqueous extract of Brassica oleracea L. exerts phytotoxicity by modulating H2O2 and O2– levels, antioxidant enzyme activity and phytohormone levels. Plants. 2023;12(17):3086. 10.3390/plants12173086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma X, Shen S, Li W, Wang J. Elucidating the eco-friendly herbicidal potential of microbial metabolites from Bacillus altitudinis. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2024;40(11):356. 10.1007/s11274-024-04154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossmann K, Kwiatkowski J, Tresch S. Auxin herbicides induce H2O2 overproduction and tissue damage in cleavers (Galium aparine L). J Exp Bot. 2001;52(362):1811–6. 10.1093/jexbot/52.362.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossmann K. Mediation of herbicide effects by hormone interactions. J Plant Growth Regul. 2003;22(1):109–22. 10.1007/s00344-003-0020-0. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyerova K, Hosek P, Quareshy M, Li J, Klima P, Kubes M, Yemm AA, Neve P, Tripathi A, Bennett MJ, et al. Auxin molecular field maps define AUX1 selectivity: many auxin herbicides are not substrates. New Phytol. 2018;217(4):1625–39. 10.1111/nph.14950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaines TA, Duke SO, Morran S, Rigon CAG, Tranel PJ, Küpper A, Dayan FE. Mechanisms of evolved herbicide resistance. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(30):10307–30. 10.1074/jbc.REV120.013572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pazmiño DM, Rodríguez-Serrano M, Romero-Puertas MC, Archilla-Ruiz A, Del Río LA, Sandalio LM. Differential response of young and adult leaves to herbicide 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in pea plants: role of reactive oxygen species. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34(11):1874–89. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhammad A, Hao H, Xue Y, Alam A, Bai S, Hu W, Sajid M, Hu Z, Samad RA, Li Z, et al. Survey of wheat straw stem characteristics for enhanced resistance to lodging. Cellulose. 2020;27(5):2469–84. 10.1007/s10570-020-02972-7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coen E, Cosgrove DJ. The mechanics of plant morphogenesis. Science. 2023. 10.1126/science.ade8055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson K, Hamant O, Bhalerao RP. Plant cell walls as mechanical signaling hubs for morphogenesis. Curr Biol. 2022;32(7). 10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.036. PR334-R340. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Naing AH, Soe MT, Yeum JH, Kim CK. Ethylene acts as a negative regulator of the stem-bending mechanism of different cut snapdragon cultivars. Front Plant Sci. 2021. 10.3389/fpls.2021.745038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng G, Wang L, He S, Liu J, Huang H. Involvement of pectin and hemicellulose depolymerization in cut Gerbera flower stem bending during vase life. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2020;167: 111231. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2020.111231. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonsson K, Ma Y, Routier-Kierzkowska A-L, Bhalerao RP. Multiple mechanisms behind plant bending. Nat Plants. 2023;9(1):13–21. 10.1038/s41477-022-01310-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Sheng Y, Xu H, Li Q, Lin X, Zhou Y, Zhao Y, Song X, Wang J. Transcriptome and hormone metabolome reveal the mechanism of stem bending in water lily (Nymphaea tetragona) cut-flowers. Front Plant Sci. 2023. 10.3389/fpls.2023.1195389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao H, Wang S, Yang R, Yang D, Zhao Y, Kuang J, Chen L, Zhang R, Hu H. Side chain of confined xylan affects cellulose integrity leading to bending stem with reduced mechanical strength in ornamental plants. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;329: 121787. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.121787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren W, Lei L, Su J, Zhang R, Zhu Y, Chen W, Wang L, Wang R, Dai J, Lin Z, et al. Toxicity of different forms of antimony to rice plant: effects on root exudates, cell wall components, endogenous hormones and antioxidant system. Sci Total Environ. 2020;711:134589. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Xue Y, Fan J, Yao J, Qin M, Lin T, Lian Q, Zhang M, Li X, Li J, et al. A systems genetics approach reveals PbrNSC as a regulator of lignin and cellulose biosynthesis in stone cells of pear fruit. Genome Biol. 2021;22(1): 313. 10.1186/s13059-021-02531-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Y, He Z, Liu Q, Lai S, Yang H. Effect of exogenous ATP on the postharvest properties and pectin degradation of mung bean sprouts (Vigna radiata). Food Chem. 2018;251:9–17. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Chen X, Chu S, You Y, Chi Y, Wang R, Yang X, Hayat K, Zhang D, Zhou P. Comparative cytology combined with transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of Solanum Nigrum L. in response to cd toxicity. J Hazard Mater. 2022;423: 127168. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang S, Yin F, Li J, Ren S, Liang X, Zhang Y, Wang L, Wang M, Zhang C. Transcriptomic and metabolomic investigation of metabolic disruption in Vigna unguiculata L. triggered by acetamiprid and cyromazine. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;239: 113675. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–52. 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson NM, Oshlack A, Corset. Enabling differential gene expression analysis for de novoassembled transcriptomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15(7):410. 10.1186/s13059-014-0410-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):59–60. 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li B, Dewey CNRSEM. Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(1):323. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using Real-Time quantitative PCR and the 2–∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen C, Wu Y, Li J, Wang X, Zeng Z, Xu J, Liu Y, Feng J, Chen H, He Y, et al. TBtools-II: A one for all, all for one bioinformatics platform for biological Big-Data mining. Mol Plant. 2023;16(11):1733–42. 10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossmann K. Auxin herbicides: current status of mechanism and mode of action. Pest Manag Sci. 2010. 10.1002/ps.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilbert AF. The status of plant-growth substances and herbicides in 1945. Chem Rev. 1946;39(2):199–218. 10.1021/cr60123a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simionato D, Block MA, La Rocca N, Jouhet J, Maréchal E, Finazzi G, Morosinotto T. The response of Nannochloropsis gaditana to nitrogen starvation includes de novo biosynthesis of triacylglycerols, a decrease of chloroplast galactolipids, and reorganization of the photosynthetic apparatus. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12(5):665–76. 10.1128/ec.00363-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maeda H, DellaPenna D. Tocopherol functions in photosynthetic organisms. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10(3):260–5. 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farré G, Sanahuja G, Naqvi S, Bai C, Capell T, Zhu C, Christou P. Travel advice on the road to carotenoids in plants. Plant Sci. 2010;179(1):28–48. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.03.009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H, Zhang S, Wu K, Li R, He X, He D, Huang C, Wei H. The effects of exogenous organic acids on the growth, photosynthesis and cellular ultrastructure of Salix variegata franch. under Cd stress. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;187: 109790. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffmann N, King S, Samuels AL, McFarlane HE. Subcellular coordination of plant cell wall synthesis. Dev Cell. 2021;56(7):933–48. 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu H, Zhang R, Tao Z, Li X, Li Y, Huang J, Li X, Han X, Feng S, Zhang G, et al. Cellulose synthase mutants distinctively affect cell growth and cell wall integrity for plant biomass production in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59(6):1144–57. 10.1093/pcp/pcy050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu K, Cao J, Zhang J, Xia F, Ke Y, Zhang H, Xie W, Liu H, Cui Y, Cao Y, et al. Improvement of multiple agronomic traits by a disease resistance gene via cell wall reinforcement. Nat Plants. 2017;3(3):1–9. 10.1038/nplants.2017.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Yu J, Wang X, Durachko DM, Zhang S, Cosgrove DJ. Molecular insights into the complex mechanics of plant epidermal cell walls. Science. 2021;372(6543):706–11. 10.1126/science.abf2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.T Anderson C, J Kieber J. Dynamic construction, perception, and remodeling of plant cell walls. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2020;71(71, 2020):39–69. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-081519-035846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cosgrove DJ. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(11):850–61. 10.1038/nrm1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boerjan W, Ralph J, Baucher M. Lignin, biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54:519–46. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao Q. Lignification. Flexibility, biosynthesis and regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21(8):713–21. 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dong N, Lin H. Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant–environment interactions. J Integr Plant Biol. 2021;63(1):180–209. 10.1111/jipb.13054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao D, Tang Y, Xia X, Sun J, Meng J, Shang J, Tao J. Integration of transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome provides insights into how calcium enhances the mechanical strength of herbaceous peony inflorescence stems. Cells. 2019;8(2):102. 10.3390/cells8020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Z, Zhang X, Lin Z, Wang J, Liu H, Zhou L, Zhong S, Li Y, Zhu C, Lai J, et al. A large transposon insertion in the Stiff1 promoter increases stalk strength in maize. Plant Cell. 2020;32(1):152–65. 10.1105/tpc.19.00486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hussain S, Liu T, Iqbal N, Brestic M, Pang T, Mumtaz M, Shafiq I, Li S, Wang L, Gao Y, et al. Effects of lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose, sucrose and monosaccharide carbohydrates on soybean physical stem strength and yield in intercropping. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2020;19(4):462–72. 10.1039/c9pp00369j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brulé V, Rafsanjani A, Pasini D, Western TL. Hierarchies of plant stiffness. Plant Sci. 2016;250:79–96. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li F, Xie G, Huang J, Zhang R, Li Y, Zhang M, Wang Y, Li A, Li X, Xia T, et al. Oscesa9 conserved-site mutation leads to largely enhanced plant lodging resistance and biomass enzymatic saccharification by reducing cellulose DP and crystallinity in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15(9):1093–104. 10.1111/pbi.12700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noack LC, Persson S. Cellulose synthesis across kingdoms. Curr Biol. 2023;33(7):R251–4. 10.1016/j.cub.2023.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Traxler C, Gaines TA, Küpper A, Luemmen P, Dayan FE. The nexus between reactive oxygen species and the mechanism of action of herbicides. J Biol Chem. 2023;299(11): 105267. 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chaudhary A, Chen X, Gao J, Leśniewska B, Hammerl R, Dawid C, Schneitz K. The Arabidopsis receptor kinase STRUBBELIG regulates the response to cellulose deficiency. PLoS Genet. 2020;16(1):e1008433. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heim DR, Skomp JR, Tschabold EE, Larrinua IM. Isoxaben inhibits the synthesis of acid insoluble cell wall materials in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1990;93(2):695–700. 10.1104/pp.93.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lefebvre A, Maizonnier D, Gaudry JC, Clair D, Scalla R. Some effects of the herbicide EL-107 on cellular growth and metabolism. Weed Res. 1987;27(2):125–34. 10.1111/j.1365-3180.1987.tb00745.x. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang R, Hu Z, Peng H, Liu P, Wang Y, Li J, Lu J, Wang Y, Xia T, Peng L. High density cellulose nanofibril assembly leads to upgraded enzymatic and chemical catalysis of fermentable sugars, cellulose nanocrystals and cellulase production by precisely engineering cellulose synthase complexes. Green Chem. 2023;25(3):1096–106. 10.1039/D2GC03744K. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang R, Gao H, Wang Y, He B, Lu J, Zhu W, Peng L, Wang Y. Challenges and perspectives of green-like lignocellulose pretreatments selectable for low-cost biofuels and high-value bioproduction. Bioresour Technol. 2023;369: 128315. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bidhendi AJ, Geitmann A. Relating the mechanics of the primary plant cell wall to morphogenesis. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(2):449–61. 10.1093/jxb/erv535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keunen E, Peshev D, Vangronsveld J, Van Wim D, Cuypers E. Plant sugars are crucial players in the oxidative challenge during abiotic stress: extending the traditional concept. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36(7):1242–55. 10.1111/pce.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Couée I, Sulmon C, Gouesbet G, El Amrani A. Involvement of soluble sugars in reactive oxygen species balance and responses to oxidative stress in plants. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(3):449–59. 10.1093/jxb/erj027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahdavi V, Farimani MM, Fathi F, Ghassempour AA. Targeted metabolomics approach toward understanding metabolic variations in rice under pesticide stress. Anal Biochem. 2015;478:65–72. 10.1016/j.ab.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li K, Chen J, Zhu L. The phytotoxicities of decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) to different rice cultivars (Oryza sativa L). Environ Pollut. 2018;235:692–9. 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salerno GL, Curatti L. Origin of sucrose metabolism in higher plants: when, how and why?? Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8(2):63–9. 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schneider T, Keller F. Raffinose in chloroplasts is synthesized in the cytosol and transported across the chloroplast envelope. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50(12):2174–82. 10.1093/pcp/pcp151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rogers LA, Dubos C, Cullis IF, Surman C, Poole M, Willment J, Mansfield SD, Campbell MM. Light, the circadian clock, and sugar perception in the control of lignin biosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(416):1651–63. 10.1093/jxb/eri162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paul MJ, Primavesi LF, Jhurreea D, Zhang Y. Trehalose metabolism and signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:417–41. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krasensky J, Jonak C. Drought. Salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(4):1593. 10.1093/jxb/err460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang S, Alseekh S, Fernie AR, Luo J. The structure and function of major plant metabolite modifications. Mol Plant. 2019;12(7):899–919. 10.1016/j.molp.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fraser CM, Chapple C. The phenylpropanoid pathway in Arabidopsis. Arabidopsis Book. 2011;9: e0152. 10.1199/tab.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gray J, Caparrós-Ruiz D, Grotewold E. Grass phenylpropanoids: regulate before using! Plant Sci. 2012;184:112–20. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Altmann M, Altmann S, Rodriguez PA, Weller B, Elorduy Vergara L, Palme J, de la Marín- N, Sauer M, Wenig M, Villaécija-Aguilar JA, et al. Extensive signal integration by the phytohormone protein network. Nature. 2020;583(7815):271–6. 10.1038/s41586-020-2460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Du J, Gerttula S, Li Z, Zhao S, Liu Y, Liu Y, Lu M, Groover AT. Brassinosteroid regulation of wood formation in Poplar. New Phytol. 2020;225(4):1516–30. 10.1111/nph.15936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yue Z, Liu N, Deng Z, Zhang Y, Wu Z, Zhao J, Sun Y, Wang Z, Zhang S. The receptor kinase OsWAK11 monitors cell wall pectin changes to Fine-Tune brassinosteroid signaling and regulate cell elongation in rice. Curr Biol. 2022;32(11):2454–e24667. 10.1016/j.cub.2022.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wolf S, Mravec J, Greiner S, Mouille G, Höfte H. Plant cell wall homeostasis is mediated by brassinosteroid feedback signaling. Curr Biol. 2012;22(18):1732–7. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liscum E, Reed JW. Genetics of aux/iaa and ARF action in plant growth and development. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;49(3):387–400. 10.1023/A:1015255030047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Staswick PE, Serban B, Rowe M, Tiryaki I, Maldonado MT, Maldonado MC, Suza W. Characterization of an Arabidopsis enzyme family that conjugates amino acids to indole-3-acetic acid. Plant Cell. 2005;17(2):616–27. 10.1105/tpc.104.026690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bari R, Jones JDG. Role of plant hormones in plant defence responses. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;69(4):473–88. 10.1007/s11103-008-9435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sun T. The molecular mechanism and evolution of the GA–GID1–DELLA signaling module in plants. Curr Biol. 2011;21(9):R338–45. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jibran R, Hunter A, Dijkwel D;P. Hormonal regulation of leaf senescence through integration of developmental and stress signals. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;82(6):547–61. 10.1007/s11103-013-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu C, Shen Y, He F, Fu X, Yu H, Lu W, Li Y, Li C, Fan D, Wang HC, et al. Auxin-mediated Aux/IAA-ARF-HB signaling cascade regulates secondary xylem development in Populus. New Phytol. 2019;222(2):752–67. 10.1111/nph.15658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Singh V, Sergeeva L, Ligterink W, Aloni R, Zemach H, Doron-Faigenboim A, Yang J, Zhang P, Shabtai S, Firon N. Gibberellin promotes Sweetpotato root vascular lignification and reduces Storage-Root formation. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10. 10.3389/fpls.2019.01320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1. Specific primers for real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR (Table S1); Evaluation statistics of sequencing data from stem samples of A. adenophora (Table S2); GO enrichment analysis in the stems of A. adenophora (Table S3); KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in the stems of A. adenophora (Table S4); The first four classes of DEMs in the stems of A. adenophora (Table S5); KEGG analysis of DEMs in the stems of A. adenophora (Table S6); Co-enriched pathways in transcriptomic and metabolomic data of A. adenophora stems (Table S7); Identification of carbohydrate metabolism-related DEGs and DEMs in MEIAA-induced curved stems of A. adenophora (Table S8); Identification of phenylpropanoid metabolism-related DEGs and DEMs in MEIAA-induced curved stems of A. adenophora (Table S9); Identification of plant hormone signal transduction-related DEGs and DEMs in MEIAA-induced curved stems of A. adenophora (Table S10). Analysis of DEGs between Upright and Bent Stems of A. adenophora (Fig. S1); GO Annotation of DEGs in MEIAA-treated bent stems of A. adenophora (Fig. S2); KEGG enrichment pathway analysis of DEGs in MEIAA-treated bent stems of A. adenophora (Fig. S3); Qualitative and quantitative analysis of metabolomic data in MEIAA-treated bent stems of A. adenophora (Fig. S4); MEIAA-treated bent stems of A. adenophora: DEMs and KEGG analysis (Fig. S5); Nine-quadrant correlation plot of transcriptome and metabolome in bent vs. upright stems (Fig. S6); Bar plot of KEGG enrichment analysis results for transcriptome and metabolome in bent vs. upright stems (Fig. S7); qRT-PCR validation of RNA Sequencing data accuracy (Fig. S8).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. The raw transcriptome data have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under project accession number PRJNA1265656 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1265656).