Abstract

Background

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex autoimmune disease where B-cell proliferation and activation play a pivotal role in pathogenesis. While the role of basophils in SLE is recognized, the impact of basophil-derived exosomes on B-cell proliferation and activation has not been thoroughly investigated.

Methods

Exosomes from human basophils in both resting and activated states were isolated and characterized. These exosomes were then co-cultured with B cells to assess their effects on B-cell survival and proliferation. To investigate the in vivo roles, a Pristane-induced lupus model in Mcpt8flox/flox CAGGCre−ERTM mice was utilized. The Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice were analyzed for basophil-derived exosome accumulation in the spleen and kidneys, and the effects on immune cell proliferation and plasma cell-plasmablast balance were assessed. Transcriptomic analysis was conducted on basophil-derived exosomes to identify key non-coding RNAs. Lupus mice were humanized by transplanting peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with SLE into immunodeficient mice to evaluate the effects of intervening miR-24550 in B cells.

Results

Activated basophil-derived exosomes were found to enhance B-cell survival and proliferation in patients with SLE. In the lupus mouse model, basophil-derived exosomes accumulated primarily in the spleen and kidneys, inducing excessive immune cell proliferation and disrupting the plasma cell-plasmablast balance, which worsened kidney damage. Transcriptomic analysis revealed key non-coding RNAs within basophil-derived exosomes. Activated basophil-derived exosomes were internalized by B cells, releasing miR-24550, which promoted B-cell proliferation. In humanized SLE mice, inhibiting miR-24550 in B cells reduced immune hyperactivation and improved renal function, similar to the effects of inhibiting basophil-derived exosomes release in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice. Ultimately, basophil-derived exosomal miR-24550 promotes B-cell proliferation and activation by targeting Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5), which exacerbates SLE progression.

Conclusions

Basophil-derived exosomal miR-24550 promotes B-cell proliferation and activation by targeting KLF5, thereby exacerbating SLE progression. This study presents a novel strategy for SLE prevention and treatment.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04324-3.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus, Basophils, B cells, Exosomes, miR-24550

Background

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease that is characterized by excessive adaptive immune responses, autoreactive B-cell hyperactivation, and pathogenic autoantibody and cytokine production in large quantities, which lead to multiple organ damage [1]. B-cell activation is regulated by factors such as defective immune regulatory mechanisms, loss of immune tolerance, and abnormal signal transduction [2]. Therefore, targeted intervention of B-cell functions may be a safe and effective strategy for treating SLE. Clinical trials conducted over the past decade for the prevention and treatment of SLE have focused on biological therapies that target B-cell activation through interventions such as B-cell surface costimulatory molecules and activators, interference with intracellular B-cell signal transduction, and B-cell depletion [3].

However, basophils—which are classic innate immune cells—have recently received significant attention in studies that have analyzed the relation between innate and adaptive immunity [4, 5]. Basophils may play a deleterious role in SLE pathogenesis, and their activation in SLE is primarily mediated by circulating IgE immune complexes [6, 7]. Basophils and mast cells share several functional similarities, such as the expression of the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) and the ability to release histamine and cytokines upon activation [8, 9]. Activated basophils upregulate lymphocyte homing receptors that house secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) and regulate B cells through T-cell-dependent and independent pathways, thereby exacerbating SLE progression. Basophil homing is influenced by several factors, such as chemokines, adhesion molecules, and cytokines. Basophils express various chemokine receptors, such as CCR3 and CCR7, for chemokines and adhesion molecules to facilitate their migration toward inflamed tissues. For example, CCR3 helps recruit basophils to allergic inflammatory sites, whereas CCR7 is essential for their migration to secondary lymphoid organs [10]. Additionally, adhesion molecules such as CD62L (L-selectin) are crucial during the initial tethering and rolling of basophils on endothelial cells, which is a critical step in the homing process [7]. Furthermore, cytokines such as IL-3 and IL-33 influence basophil homing. IL-3 promotes basophil survival and activation, which enhances their migration to inflamed tissues. In contrast, IL-33 directly activates the basophils and promotes their migration [11]. A study on the impact of activated basophil-generated inflammatory cytokines and homing receptors on the development of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) found that the IL-4, IL-6, and IL-13 levels in the basophils and CD62L and CCR7 expression were higher in patients with RA than in healthy participants [12]. Thus, these cytokines and receptors may contribute to the homing of basophils to inflamed joints in patients with RA. Additionally, the roles of specific transcription factors and signaling pathways in basophil homing have been recently highlighted. The transcription factor GATA-2 is essential for basophil development and functioning, and its activity influences their migration [13]. Additionally, the expression of certain surface molecules, such as CLEC12A, affects basophil homing. CLEC12A is highly expressed on immature basophils and enables their retention in the bone marrow. However, activated basophils downregulate CLEC12A, which may facilitate their exit from the bone marrow and migration to peripheral tissues [14]. Therefore, basophil homing is a complex process that is influenced by a variety of factors such as chemokines, adhesion molecules, cytokines, and other signaling molecules. These factors interact to guide basophils to specific tissues to contribute to immune responses. The lack of basophils in lupus-like mouse models delayed disease progression by reducing autoantibody levels, circulating immune complex deposition in the glomeruli, and kidney function [6, 7]. Basophils derived from patients with SLE (in an activated state) induced B cells in vitro to produce significant quantities of autoantibodies several times higher than those produced by normal non-activated basophils [15–17]. Additionally, basophils accumulated in the SLOs of patients with SLE and promoted autoantibody production [6, 18]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying basophil-mediated regulation of B cells during SLE progression need to be clarified urgently.

Exosomes are novel carriers of intercellular communication and play a significant role in almost all diseases. They are disc-shaped vesicles that are 30–150 nm in diameter and originate from intracellular multivesicular bodies. They exist widely and stably in various body fluids and deliver compounds (nucleic acids, lipids, proteins, etc.) to recipient cells to regulate their biological functions [19]. The roles of exosomes in SLE pathogenesis and other related underlying mechanisms have received widespread attention. The basophil-derived ultrastructure shows that the basophils contain many membrane vesicles that are 80–100 nm in diameter and of low electron density [20]. Electron microscopy shows that basophils contain many intracellular exosome-like membrane vesicles, which are released into the extracellular space upon basophil activation to perform their biological functions [21].

Exosomes primarily exert their biological functions after being taken up by recipient cells and releasing their effector molecules, which regulate the recipient cells [22]. These effector molecules include various RNAs (e.g., miRNA, lncRNA, circRNA, and mRNA), proteins, and lipids [23]. MiRNA is a class of non-coding single-stranded RNAs that are approximately 20–24 nucleotides long and encoded by endogenous genes. miRNAs have been primarily studied for their underlying mechanism in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. miRNAs bind to the 3′ untranslated region of mRNA through base pairing, which degrades the mRNA or inhibits its translation, thereby regulating gene expression [24]. Exosomes that act as intercellular communication carriers encapsulate miRNAs and release them extracellularly after transporting them to recipient cells to regulate their functions. Furthermore, miRNAs are abundant in exosomes. In this study, we aimed to analyze the exosomes released by activated basophils and elucidate the effects of the released miRNAs on B cells. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate the role and underlying molecular mechanisms of basophil-derived exosomes in B-cell activation during SLE development in patients with SLE, pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice, and humanized SLE mice. Subsequently, we have inferred that basophil-derived exosomal miR-24550 promotes B-cell activation by targeting Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5), which exacerbated SLE progression. Thus, this study suggests a novel strategy for SLE prevention and treatment.

Methods

Patients

This study was conducted at the Department of Nephrology between September 2020 and November 2024. In total, 48 patients with SLE were enrolled based on the modified SLE classification criteria formulated by the American College of Rheumatology in 1997. SLE was assessed according to the SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) 2000 (SLEDAI score > 6). Details, including patient age, sex, positivity rate for anti‐dsDNA IgG and anti‐nuclear IgG, SLEDAI score, and prior treatments, are summarized in the Additional file 1 (Supplementary Tables). This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (Approval no. YJYS2020107). Written informed consent was obtained from all the enrolled patients.

Mice

Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM, Mcpt8flox/flox, and NKG mice were obtained from Cyagen Biosciences (License No. SCXK (Yue) 2020–0055). The mice were housed in a separate pathogen-free barrier facility under the following conditions: 12-h light/dark cycle, 22–25 °C, 40–60% humidity, and free access to water and feed. The maintenance of these mice was approved by the Ethics Committee for Experimental Animals of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (Approval no. GDY2002081). All experiments were conducted under the national animal welfare guidelines. The animal experiment procedures were conducted in strict compliance with the ARRIVE Guidelines (Additional file 2).

Construction of Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox,CAGGCre−ERTM mouse models

Tamoxifen (Sigma, USA) was dissolved in corn oil to a concentration of 20 mg/mL and agitated overnight at 37 °C, followed by sonication for 30 min at the same temperature. Then, 150 µL of Tamoxifen (20 mg/mL) was administered intraperitoneally to Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice (6 weeks old) every 24 h for 7 days. Then, a single intraperitoneal injection of pristane (0.5 mL) (Sigma–Aldrich) was administered to each mouse. We constructed a Pristane–Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mouse model via intraperitoneal pristane injection. We divided the Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice into the lupus control group (having lupus but not subjected to any specific experimental intervention (Control)), basophil-deficient group (Tamoxifen), basophil adoptive transfer group (Tamoxifen + Baso), basophil exosome adoptive transfer group (Tamoxifen + BasoExo), and basophil exosome inhibition group (Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869).

Construction of humanized SLE mouse models

NKG-immunodeficient mice were divided into four groups: SLE patient peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) transplant control (SLE control), healthy volunteer PBMC transplant control (Normal control), B-cell miR-24550 overexpression (miR-24550OE), and B-cell miR-24550 knockdown (miR-24550KD). The PBMCs were extracted from the patients with SLE in the miR-24550OE and miR-24550KD groups. Then, B cells were sorted and treated with miR-24550 and transplanted into immunodeficient mice along with the PBMCs.

Negative selection of human basophils

Untouched, highly purified basophils from HetaSep™-processed human peripheral blood were isolated using immunomagnetic negative selection (STEMCELL, USA). The sample was prepared at the indicated cell concentration (5 × 107 cells/mL) within the volume range of 0.25–1.5 mL. The sample was added to a 5-mL (12 × 75 mm) polystyrene round-bottom tube (Catalog #38,007). Next, 50 µL/mL of the Isolation Cocktail was added to the sample, followed by mixing and incubation at room temperature (15–25 °C) for 7 min. Next, the mixture was vortexed with RapidSpheres for 30 s. Then, 50 µL/mL of RapidSpheres™ was added to the sample and mixed without incubation. Immediately, the recommended medium was added to the top of the sample at the indicated volume (2.5 mL) and mixed gently by pipetting the top 2.5 mL up and down 2–3 times. The tube (without a lid) was placed into the magnet and incubated at room temperature for 3 min. The magnet was picked up, and the magnet and tube were inverted in one continuous motion to pour the enriched cell suspension into a new 5-mL tube. The tube was removed from the magnet. A new tube (without a lid) was placed into the magnet and incubated at room temperature for 3 min. The magnet was picked up and inverted in one continuous motion to pour the enriched cell suspension into a new tube. The isolated cells were ready for use. The purity of the human basophils (CD123+ CD203c+) was assessed through flow cytometry using the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: anti-human CD123-APC-Cy7 and anti-human CD203c-PE (eBioscience, USA).

Activation of basophils

The isolated basophils were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Then, the basophils were stimulated with anti-IgE antibodies (Sigma–Aldrich, Catalog No. I6284) at a concentration of 2 µg/mL. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h to enable basophil activation. After stimulation, the cells were harvested and washed with PBS. The expression of activation markers such as CD203c was assessed using flow cytometry. Monoclonal antibodies against CD203c (BioLegend, Catalog No. 324606) were used for surface staining. The cells were incubated with the antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C, followed by washing with PBS. The stained cells were analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were acquired and analyzed using FlowJo software.

Negative selection of human B cells

Untouched and highly purified B cells were isolated from fresh or previously frozen human PBMCs or washed leukapheresis samples using immunomagnetic negative selection (STEMCELL, USA). The samples were prepared at the indicated cell concentration (5 × 107 cells/mL) at the volumetric range of 0.25–2 mL. The sample was transferred to a 5-mL (12 × 75 mm) polystyrene round-bottom tube (Catalog #38,007). To this, 50 µL/mL of Cocktail Enhancer was added, followed by the addition of 50 µL/mL of the Isolation Cocktail. After mixing, the sample was incubated at room temperature for 5 min, followed by incubation with Vortex RapidSpheres™ for 30 s. Then, 50 µL/mL of RapidSpheres™ were added to the sample and mixed without incubation. The volume was adjusted to the indicated level using the recommended medium, followed by gently pipetting 2.5 mL up and down 2–3 times to ensure proper mixing. The tube (without lid) was placed into the magnet and incubated at room temperature for 3 min. Then, the magnet and tube were inverted in one continuous motion to pour the enriched cell suspension into a new 5-mL tube. Then, the tube was removed from the magnet. The new tube (without a lid) was placed into the magnet and incubated for a second separation at room temperature for 1 min. The magnet and tube were inverted in one continuous motion to pour the enriched cell suspension into a new tube. Then, the isolated cells were ready for use. Flow cytometry was performed to assess the purity of the human B cells (CD19+) using the anti-human CD19-FITC (BD Biosciences, USA) antibody.

Electroporation of human B cells

A mixture containing 2 µg siRNA, 10 µL Buffer 103A, 10 µL Buffer 103B, and 2 × 106 cells was prepared in electroporation tubes by following the description provided in the Celetrix electroporation kit (Cat#1207, Celetrix). Electroporation was performed at a voltage of 500 V for 20 ms. Next, the cells were resuspended in the recommended medium, which contained 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) along with dual antibiotics and transferred back to the culture plates.

Isolation of basophil-derived exosomes

Supernatants from each group were collected and centrifuged at 4 °C as follows: 300 × g for 10 min, 2000 × g for 10 min, 10,000 × g for 30 min. Then, the basophil-derived exosomes were obtained as pellets after ultracentrifugation with an Optima XE-100-IVD (Beckman Coulter, USA) at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The pellets were washed once in PBS and filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. In all experiments, the basophil-derived exosomes were used immediately after ultracentrifugation. The ultrastructure and shape of the basophil-derived exosomes were confirmed using TEM (JEM-1400, MA JEOL Ltd., Japan). The protein concentration of the basophil-derived exosomes was measured using a bicinchoninic acid assay. The markers CD9 (Abcam, UK), CD63 (Abcam, UK), and TSG101 (Abcam, UK), and the negative expression protein β-actin (Abcam, USA) were detected using western blotting. Nanoparticle tracking assay (NTA; Nanosight NS300, Malvern, UK) was performed to measure the size distribution and concentration of the basophil-derived exosomes.

Detection of exosome uptake by B cells

To detect the uptake of basophil-derived exosomes by B cells, the exosomes were labeled using the PKH26 Red Fluorescent Cell Linker Kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The exosomes were incubated with diluent C and PKH26 dye solution as per the kit instructions. After washing with PBS to remove the unbound dye, the PKH26-labeled exosomes were incubated with B cells. Controls were created by incubating only B cells with the PKH26-PBS solution. Subsequently, DAPI staining was performed to stain the nuclei. Then, fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan) was performed to visualize and confirm the uptake of exosomes by B cells through the co-localization of red fluorescence (PKH26-labeled exosomes) and blue fluorescence (DAPI-stained nuclei).

Transmission electron microscopic analysis

Basophils were incubated overnight at 4 °C in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.2) containing 2% glutaraldehyde and 4% formaldehyde, followed by fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide in an s-collidine buffer. After staining with lead citrate and uranyl acetate, the samples were examined using TEM (JEM-1400, JEOL Ltd., Japan) at 80 kV. A 5-µL basophil exosome suspension was mixed gently but thoroughly with 5 µL of PBS. Then, 10 µL of the diluted exosome suspension was transferred onto a copper grid, allowed to settle for 2 min, and blotted with filter paper to remove excess liquid. Next, 10 µL of 2% uranyl acetate was applied to the dried copper grid and allowed to stand for 1 min, followed by blotting with a filter paper to remove excess dye and air-drying at room temperature for 3 min. TEM (JEM-1400, JEOL Ltd., Japan) was used to observe and record the exosome morphology.

Flow cytometric analysis

Human basophils were identified through positive staining for CD123-APC-Cy7 and CD203c-PE (eBioscience, USA). CD203c-PE expression in basophils was quantified based on mean fluorescence intensity (eBioscience, USA). Human B cells were identified by positively staining for CD19-FITC (BD Biosciences, USA). Ki67-APC-Cy7 and CD86-BB700 expression levels in human B cells were quantified based on mean fluorescence intensity (BD Biosciences, USA). Mouse basophils were sorted through FACS with gates set for FcεRIα-BV421, CD49b-BV510, CD117-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences, USA), and CD11c-APC (BioLegend, USA). Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM, and Mcpt8flox/flox mouse basophils were gated using IgE-FITC and CD49b-APC (BioLegend). Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM, and Mcpt8flox/flox mice plasma cells were identified based on positivity for CD138-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BioLegend, USA) and CD19-APC-Cy7 (BD Biosciences, USA). Humanized mouse plasmablasts were identified through positive staining for CD38-APC and CD27-PE (BD Biosciences). Humanized mouse memory B cells were identified through positive staining for IgD-PerCP-Cy5.5 and CD27-PE (BD Biosciences, USA). The data were acquired and analyzed using the FACS Celesta™ Flow Cytometer and FlowJo Software (BD Biosciences, USA), respectively.

Western blotting analysis

Western blotting was performed to assess the expression of the target proteins in the cells. Protein samples were subjected to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, which was blocked with 5% BSA in TBST solution, incubated with the primary antibody, washed thoroughly, and incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Chemiluminescent reactions were visualized using the Azure C500 Western Blot Imaging System and analyzed using ImageJ software. Uncropped gel images are summarized in the Additional file 3.

RNA sequencing analysis

MiRNA analysis was performed using Haplox. The exosomes were extracted using ultracentrifugation. RNA purity was validated using the NanoDrop™ One/OneC spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). RNA concentration was measured using the Qubit® RNA HS Assay Kit and Qubit® 3.0 Flurometer (Life Technologies, USA). Next, approximately 3 µg of RNA per sample was used for establishing a small RNA library. Sequence libraries were created using NEBNext® Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina® (NEB, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and index codes were assigned to attribute sequences to each sample. Clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using the TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBotHS (Illumina). After cluster generation, the library was sequenced using an Illumina platform.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the cultured cells using RNAiso Plus (Takara, Japan). Complementary DNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Japan), and qRT-PCR was performed using the following primers:

hsa-miR-148a-3p (forward: 5′-cggTCAGTGCACTACAGAACTTTGT-3′),

hsa-miR-25109 (forward: 5′-aCCTGTCTGAGCGTCGCTT-3′),

hsa-miR-21-5p (forward: 5′-cggcgTAGCTTATCAGACTGATGTTGA-3′),

hsa-miR-24550 (forward: 5′-attAAGAGGGACGGCCGGG-3′),

hsa-miR-26a-5p (forward: 5′-cgggTTCAAGTAATCCAGGATAGGCT-3′),

hsa-miR-25-3p (forward: 5′-gCATTGCACTTGTCTCGGTCTGA-3′),

hsa-miR-122-5p (forward: 5′-ccgTGGAGTGTGACAATGGTGTTTG-3′),

KLF5: forward: 5′-AAGGCTGCGACTGGAGGTTC-3′; reverse: 5′-GCGAGAAGCTGCGGTTGC-3′

The primers were obtained from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Data analysis was performed using the ΔΔCt method.

Dual-luciferase-reporter gene analysis

The bioinformatic tool used to predict that miR-24550 targets KLF5 was the miRDB database. The miR-24550 sequence and the 3′-UTR of KLF5 were cloned into the pSI-Check2 vector (Hanbio, China). The luciferase constructs containing either wild-type or mutant sequences were transfected into B cells at 50–70% confluence. Concurrently, the cells were treated with either miR-24550 mimic or a negative control (NC) mimic. After 48 h, the transfected cells were harvested, and luciferase activity was quantified using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, USA). Relative firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase luminescence for data analysis.

Plasma autoantibody and inflammatory cytokines analysis

Plasma levels of autoantibodies—specifically antinuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-double-stranded DNA antibody (anti-dsDNA)—were quantified using the mouse ELISA Kit and mouse anti-dsDNA ELISA Kit (both from Alpha Diagnostics, USA) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma levels of the inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and interleukins (IL-4, IL-10, IL-12P70, IL-17) were assessed using a CBA kit (BD Biosciences, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Plasma biochemical metabolism analysis

Plasma levels of various biochemical parameters, such as urea and creatinine, were measured using a biochemical analyzer (Roche cobas® 8000, Switzerland).

Histopathological analysis

The spleens and kidneys were harvested for histopathological analysis. Tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, embedded in paraffin, sectioned to 5-μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), and Masson’s trichrome.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed by fixing the spleen and kidneys in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 h, followed by washing thrice with 7% sucrose in PBS. One set of samples was embedded in OCT medium, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and sectioned into 5-μm sections. Immunofluorescence staining was performed to evaluate splenic CD19 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and IL-10 (Abcam) deposition using a VS200 microscope. Immunofluorescence staining intensity for kidney IgG (Abcam) and C3 (Abcam) depositions was assessed using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to determine whether the data conformed to normal distribution. Normally distributed data between two groups were compared using general or Welch t-tests based on whether the variance was equal or unequal, respectively. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Data analysis and graph generation were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, USA).

Results

Basophil-derived exosomes enhance survival and proliferation of B cells in patients with SLE

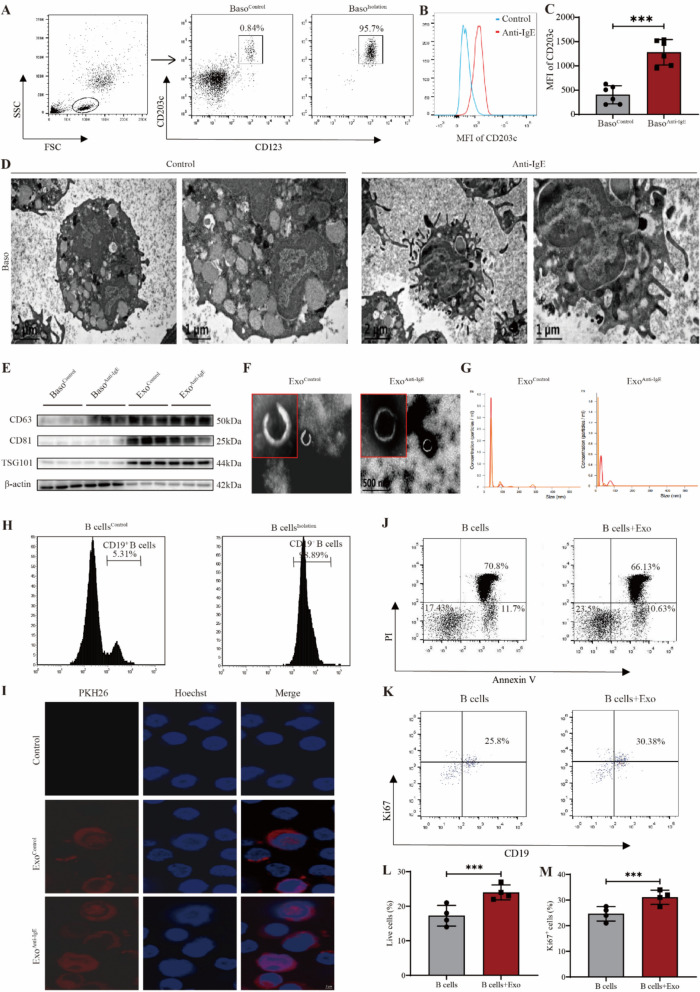

We isolated basophils from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers and assessed their purity using flow cytometry. Before sorting, CD123+CD203c+ basophils comprised 0.84% of the total count; sorting showed that purity was 95.7% (Fig. 1A). Basophil activation was achieved in patients with SLE through anti-IgE stimulation. CD203c is a key marker for identifying and detecting basophils and their activation status [25]. Basophil activation was assessed by measuring the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD203c. The CD203c-MFI of anti-IgE-stimulated basophils was significantly higher than that of the Control group basophils (P = 0.0044) (Fig. 1B–C). Furthermore, transmission electron microscopy images of the morphological characteristics and ultrastructure of the basophils were compared before and after activation. The anti-IgE-activated basophils showed significantly low levels of intracellular vesicle-like and granule-like materials and extended more pseudopodia. This indicates an overall active state (Fig. 1D). Basophil-derived exosomes were isolated using ultracentrifugation. Western blotting was performed to identify the surface markers on exosomes in the ExoControl and ExoAnti−IgE groups. CD81, CD63, and TSG101 expression levels were higher in both basophil-derived exosome groups than in the basophil cells, whereas β-actin was not expressed (Fig. 1E). Transmission electron microscopy-based observation of the morphology of exosomes in the ExoControl and ExoAnti−IgE groups showed round-shaped exosomes with clear outer membrane boundaries and a typical “saucer-like” structure that was approximately 100 nm in diameter (Fig. 1F). Nanosight NS300 NTA showed that the particle size of exosomes in both ExoControl and ExoAnti−IgE groups peaked at 30–50 nm, although the overall range was 80–100 nm with an average particle size of 53.1 ± 11.8 nm and average particle concentration of 1.59 × 109 ± 1.93 × 108 particles/mL (Fig. 1G).

Fig. 1.

Basophil-derived exosomes enhance the survival and proliferation of B cells in SLE patients. A Flow cytometric analysis of CD123+ CD203c+ basophil purity. B Flow cytometric analysis of CD203c expression in human basophils. C Statistical analysis of CD203c expression in human basophils (n = 6). D Transmission electron microscopy images of human basophil morphology. E Western blotting analysis of human basophils and their exosomes. F Transmission electron microscopy images of human basophil-derived exosome morphology. G Nanoparticle tracking analysis of basophil-derived exosome size. H Flow cytometric analysis of CD19+ B-cell purity. I Immunofluorescence analysis of basophil-derived exosomes and B-cell colocalization. J Flow cytometric analysis of B-cell survival. K Flow cytometric analysis of B-cell proliferation. L Statistical analysis of B-cell survival (n = 4). M Statistical analysis of B-cell proliferation. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 4). C, L, and M were analyzed by independent-samples t-tests. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

To elucidate the effects of basophil-derived exosomes on B-cell survival and proliferation, we isolated B cells from the peripheral blood of patients with SLE and assessed their purity using flow cytometry. Before sorting, CD19+ B cells from patients with SLE comprised 5.31% of the total count; after sorting, the purity was 98.89% (Fig. 1H). To verify whether basophil-derived exosomes interact with the B cells from patients with SLE, we co-cultured PKH26 (red)-labeled basophil-derived exosomes with CD19+ B cells from patients with SLE for 24 h. Subsequently, CD19+ B cells from patients were labeled with Hoechst dye (blue) for immunofluorescence co-localization detection. The basophil-derived exosomes were taken up by the CD19+ B cells from patients with SLE. Additionally, the ingested basophil-derived exosomes were primarily located in the cytoplasm of the CD19+ B cells from patients with SLE (Fig. 1I). To determine whether activated basophil-derived exosomes affect the survival and proliferation of B cells from patients with SLE, we co-cultured activated basophil-derived exosomes with B cells from patients with SLE for 3 days and assessed early apoptosis (Annexin V), late apoptosis (PI), and proliferation (Ki-67) using flow cytometry. The survival rate of B cells from patients with SLE was significantly higher than that of the Control (group without exosomes) (P = 0.0008) (Fig. 1J, L), and the addition of activated basophil-derived exosomes enhanced their proliferative capacity (P = 0.0007) (Fig. 1K, M). These results indicate that exosomes derived from activated basophils promote the survival and proliferation of B cells in patients with SLE.

Basophil-derived exosomes migrate to spleen and kidneys in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice

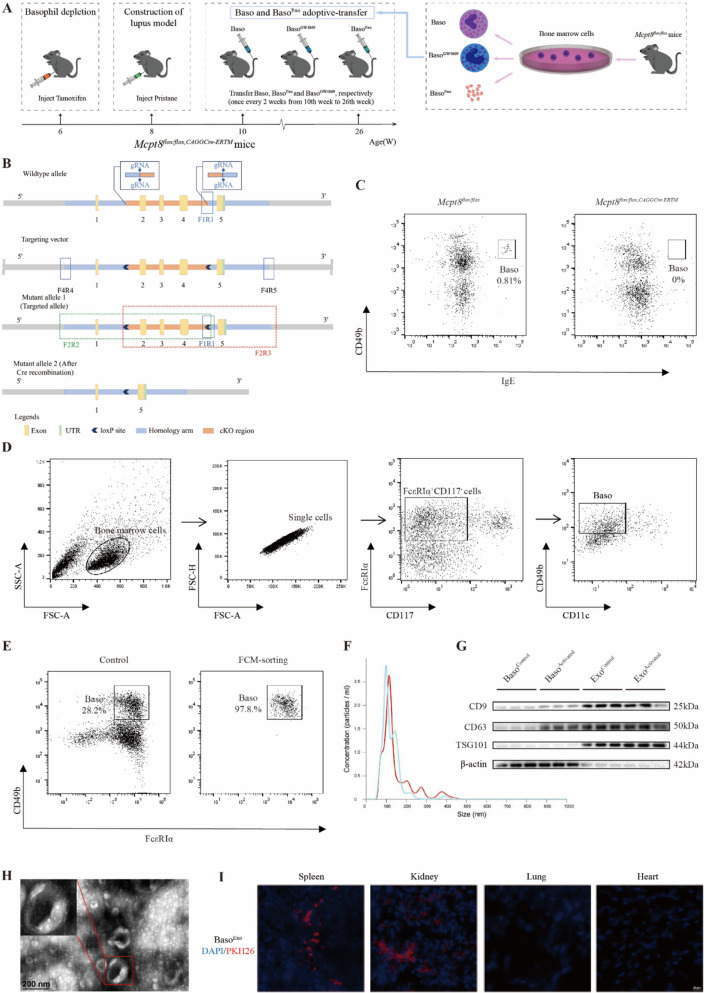

We investigated the role of basophils and their exosomes in vivo by constructing a lupus mouse model of basophil deficiency (Fig. 2A). Basophils primarily express Mcpt8, and we specifically knocked out the Mcpt8 gene in mice using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. We identified five exons with an ATG start codon in exon 1 and a TAG stop codon in exon 5. We selected exons 2–4 as the conditional knockout region. The deletion of this region resulted in the loss of Mcpt8 function in mice, leading to the absence of basophils (Fig. 2B). After successfully creating the model, we intraperitoneally injected 6-week-old Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice with 150 µL (20 mg/mL) of Tamoxifen every 24 h for 7 consecutive days. Mcpt8flox/flox mice were used as the controls and were injected at the same dosage of corn oil. We collected peripheral blood from the tail vein of the mice and performed flow cytometry to detect the basophils gated on IgE+ CD49b+. The proportion of IgE+ CD49b+ basophils in the peripheral blood of Mcpt8flox/flox mice was 0.81%; whereas it was 0% in Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice (Fig. 2C). This indicates the successful creation of a basophil-deficient mouse model.

Fig. 2.

Basophil-derived exosomes migrate to spleen and kidneys in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice. A Timeline of basophil and exosome transfer in Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice. B Schematic of Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mouse construction. C Flow cytometric analysis of basophil proportion in peripheral blood of Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice. D Flow cytometric gating for sorting induced basophils from mouse bone marrow. E Flow cytometric analysis of mouse basophil purity after sorting. F Nanoparticle tracking analysis of basophil exosome size in mice. G Western blotting analysis of mouse basophils and their exosomes. H Transmission electron microscopy of mouse basophil exosome morphology. I Immunofluorescence analysis of distribution of basophil-derived exosomes in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice

We induced basophils from the bone marrow and obtained high-purity basophils using flow sorting. The extracted exosomes were observed to elucidate the role of basophils and their exosomes in lupus progression. Using FcεRIα+ CD117− CD11c− CD49b+ as the flow sorting gate for basophils yielded basophils with 97.8% purity after sorting (Fig. 2D–E). Exosomes were extracted from these high-purity basophils and identified. NTA showed that the particle size of the basophil-derived exosomes peaked at 100 nm with an overall distribution in the 200–400 nm range (Fig. 2F). Western blotting analysis showed that CD9, CD63, and TSG101 expression levels were higher in basophil-derived exosomes than in basophils, whereas β-actin was not expressed (Fig. 2G). Transmission electron microscopy images showed basophil-derived exosomes that were round-shaped with distinct outer membrane boundaries and a typical “saucer-like” structure (Fig. 2H). These results indicate the successful extraction of basophil-derived exosomes.

We constructed a Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mouse model via intraperitoneal pristane injection. We divided the Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice into the lupus control (Control), basophil-deficient (Tamoxifen), basophil adoptive transfer (Tamoxifen + Baso), basophil exosome adoptive transfer (Tamoxifen + BasoExo), and basophil exosome inhibition (Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869) groups. Then, we initiated the adoptive transfer of basophils and their exosomes. Mcpt8flox/flox mice were used as the normal controls and did not receive any intervention. To trace the in vivo migration and distribution of basophil-derived exosomes, they were labeled with PKH26 and injected into the Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM mice via the tail vein. Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis was performed 24 h later. The results showed that exosomes primarily migrated to the spleen and kidneys to perform their functions. Only minimal distribution was observed in the lungs and heart (Fig. 2I).

Basophil-derived exosomes exacerbate disease progression in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice

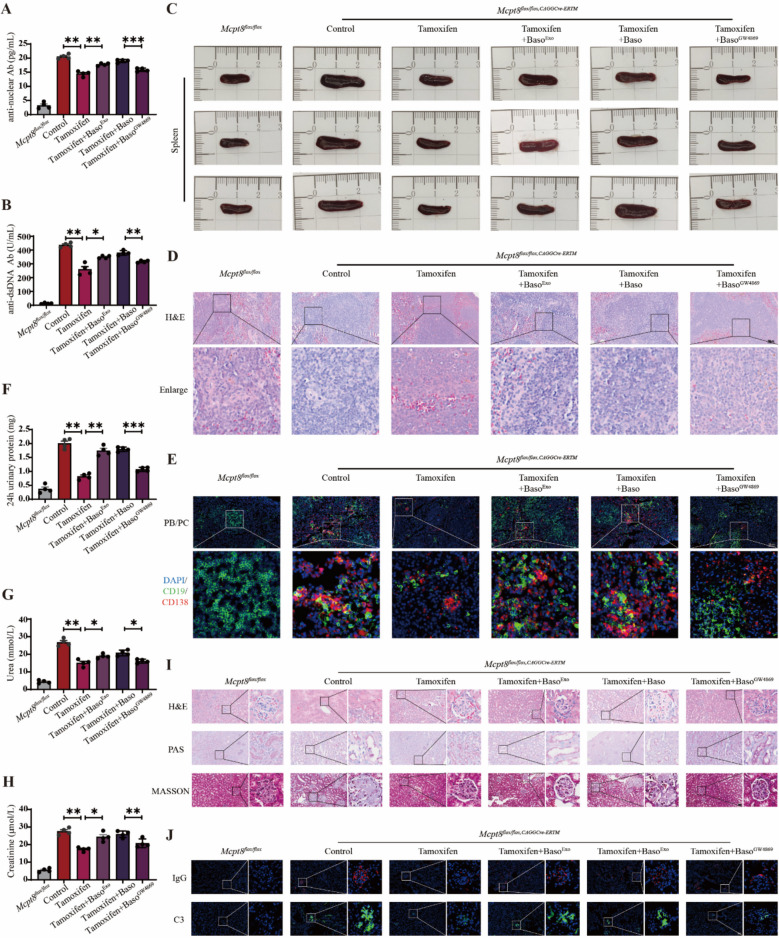

We performed ELISA to detect autoantibodies in the peripheral blood of mice with lupus and found low autoantibody levels in the tamoxifen group. This suggests the involvement of basophils in autoantibody production. High anti-nuclear (P = 0.0054; P = 0.0096; P = 0.0003) (Fig. 3A) and anti-dsDNA (P = 0.0081; P = 0.0271; P = 0.0021) (Fig. 3B) autoantibody levels were detected in the Tamoxifen + BasoExo group, whereas they were lower in the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group than in the Tamoxifen + Baso group. This indicates that basophil-derived exosomes are crucial for autoantibody release by B cells.

Fig. 3.

Basophil-derived exosomes exacerbate disease progression in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice. A Statistical analysis of plasma antinuclear antibodies in mice (n = 4). B Statistical analysis of plasma anti-dsDNA antibodies in mice (n = 4). C Morphological analysis of mouse spleen. D Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining analysis of mouse spleen pathology. E Immunofluorescence staining analysis of plasma cell and plasmablast proportions in mouse spleen. F Statistical analysis of 24-h urinary protein levels in mice (n = 4). G Statistical analysis of urea levels in mice (n = 4). H Statistical analysis of creatinine levels in mice (n = 4). I H&E, PAS, and MASSON staining analysis of mice kidney pathology (n = 4). J Immunofluorescence staining analysis of IgG and C3 deposition in mouse kidneys. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. A, B, F, G, and H were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

The spleen is a vital peripheral immune organ that promotes B-cell proliferation and differentiation and maintains immune cell balance and stability [26]. The spleen size of lupus mice was notably lower in the Tamoxifen group than in the Control group. However, the spleens were significantly larger in the Tamoxifen + BasoExo group than in the Tamoxifen group, although they were smaller in the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group than in the Tamoxifen + Baso group (Fig. 3C). H&E staining of the spleen showed lower immune cell infiltration in the Tamoxifen group than in the Control group, which indicates that basophils may drive immune cell proliferation. The Tamoxifen + BasoExo group showed higher immune cell infiltration than that in the Tamoxifen group, whereas the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group showed lower immune cell infiltration than that in the Tamoxifen + Baso group (Fig. 3D). Immunofluorescence staining showed that the proportion of plasma cells and plasmablasts in the Tamoxifen group was lower than that in the Control group. This suggests that basophils facilitate B-cell differentiation. The proportion of these cells was higher in the Tamoxifen + BasoExo group than in the Tamoxifen group, whereas it was lower in the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group than in the Tamoxifen + Baso group (Fig. 3E). These findings indicate that basophil-derived exosomes play a role in promoting B-cell differentiation.

The kidneys are frequently targeted in SLE in most patients [27]. We assessed 24-h urine protein levels in lupus mice and found that the protein levels were significantly lower in the Tamoxifen group than in the Control group. Furthermore, the urinary protein levels were higher in the Tamoxifen + BasoExo group than in the Tamoxifen group, whereas they were lower in the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group than those of the Tamoxifen + Baso group (P = 0.0017; P = 0.0032; P = 0.0005) (Fig. 3F). Additionally, the plasma kidney function metrics for urea (P = 0.0021; P = 0.0197; P = 0.0101) (Fig. 3G) and creatinine (P = 0.0068; P = 0.0116; P = 0.0075) (Fig. 3H) were low in the Tamoxifen group. In contrast, these levels were higher in the Tamoxifen + BasoExo group and lower in the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group than those of the Tamoxifen + Baso group. These findings suggest that basophil-derived exosomes may contribute to nephron loss and urea and creatinine accumulation in lupus. H&E and PAS staining of the kidney tissues showed low renal crescent formation and improved brush border detachment in the Tamoxifen group than in the Control group. The Tamoxifen + BasoExo group exhibited higher renal crescent formation and brush border detachment, whereas the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group showed improvement. MASSON trichrome staining indicated lower renal fibrosis and better overall renal health in the Tamoxifen group than in the Control group. The Tamoxifen + BasoExo group showed high renal fibrosis, whereas the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group showed low fibrosis and improved pathology (Fig. 3I). Immunofluorescence showed that the IgG and C3 levels in kidney tissues were low in the Tamoxifen group, high in the Tamoxifen + BasoExo group, and lower in the Tamoxifen + BasoGW4869 group than those of the Tamoxifen + Baso group (Fig. 3J). These results imply that basophil-derived exosomes may worsen lupus-associated nephritis progression.

MiR-24550 in basophil-derived exosomes is crucial for their function

To identify the key molecules involved in basophil-derived exosomes, we divided the cells into Control and anti-IgE groups and performed transcriptomic analysis. Cluster analysis of miRNA expression in both groups showed that the miRNAs exhibited significant differential expression. Three samples each from the ExoControl and ExoAnti−IgE groups clustered together. miRNA expression trends were consistent within the same group with minimal intra-group differences; however, the difference was significant between groups (Fig. 4A). Comparison of the two sample groups using a volcano plot showed that 983 miRNAs were significantly differentially expressed between the two groups. Moreover, 158 miRNAs were significantly upregulated and 43 miRNAs were significantly downregulated in the ExoAnti−IgE group compared with those of the ExoControl group. In the ExoAnti−IgE group, 606 mRNAs were significantly upregulated, and 1915 mRNAs were significantly downregulated (Fig. 4B). As basophils primarily regulate B cells after activation, we selected the top 10 highly expressed miRNAs in the activated basophil-derived exosomes based on the sequencing data. We predicted their downstream target genes using databases such as miRDB and TargetScan and screened for target genes related to B-cell function using databases such as STRING. We identified seven miRNAs related to B-cell function and performed qRT-PCR validation. We found that miR-21-5p, miR-122-5p, miR-24550, and miR-25109 were significantly upregulated in activated basophil-derived exosomes than in the non-activated group (P = 0.0308; P = 0.0006) (Fig. 4C). In contrast, miR-148a-3p, miR-25-3p, and miR-26a-5p were not detected in the non-activated exosomes. Additionally, miR-122-5p and miR-24550 were relatively highly expressed in the activated exosomes (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

MiR-24550 in basophil-derived exosomes is crucial for their function. A miRNA differential expression heatmap (red indicates upregulation; green indicates downregulation; higher expression is indicated by brighter colors). B miRNA differential expression volcano plot (horizontal axis: fold change; vertical axis: P-value). C Relative expression levels of miRNAs in basophil-derived exosomes before and after activation (n = 3). D Relative expression levels of miRNAs in exosomes derived from activated basophils. E Flow cytometric gating scheme for detecting CD19+ B cells. F Flow cytometric analysis of CD19+ B cell purity before and after negative selection. G miRNA expression levels in B cells from healthy volunteers and patients with SLE (n = 3). H Changes in miR-24550 expression levels after basophil activation (n = 3). I Relative expression levels of miR-24550 in B cells after co-culturing of activated basophil-derived exosomes with B cells from patients with SLE (n = 3). Results are shown as mean ± SEM. C and G were analyzed by independent-samples t-tests. I was analyzed by paired t-tests. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

Based on these bioinformatic predictions and relative expression levels, we hypothesized that miR-24550 is likely a key molecule in exosomes that is released by activated basophils. We isolated high-purity B cells from human peripheral blood and assessed their purity using flow cytometry. The results showed that CD19+ B cells were 10.6% pure before sorting and 97.2% pure after sorting (Fig. 4E–F). We validated the relative expression levels of these seven miRNAs in peripheral blood B-cells from patients with SLE and age- and sex-matched healthy volunteers using qRT-PCR. We found that miR-24550 expression was higher in B cells from patients with SLE than in healthy volunteers, whereas miR-21-5p, miR-148-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-26a-5p, and miR-122-5p expression levels did not differ (P = 0.0004) (Fig. 4G). This suggests that miR-24550 may be associated with the immune dysregulation of B cells in SLE. Additionally, we found that miR-24550 expression levels increased progressively until 48 h, followed by stabilization through 72 h (Fig. 4H). After co-culturing the activated basophil-derived exosomes with B cells from patients with SLE for 48 h, miR-24550 expression in B cells showed an upward trend (P = 0.0258) (Fig. 4I). Therefore, we hypothesized that basophils are activated in the SLE disease model and that they upregulate miR-24550, which is then packaged into exosomes to regulate the recipient cells. This may be the key molecule through which activated basophil-derived exosomes regulate B cells.

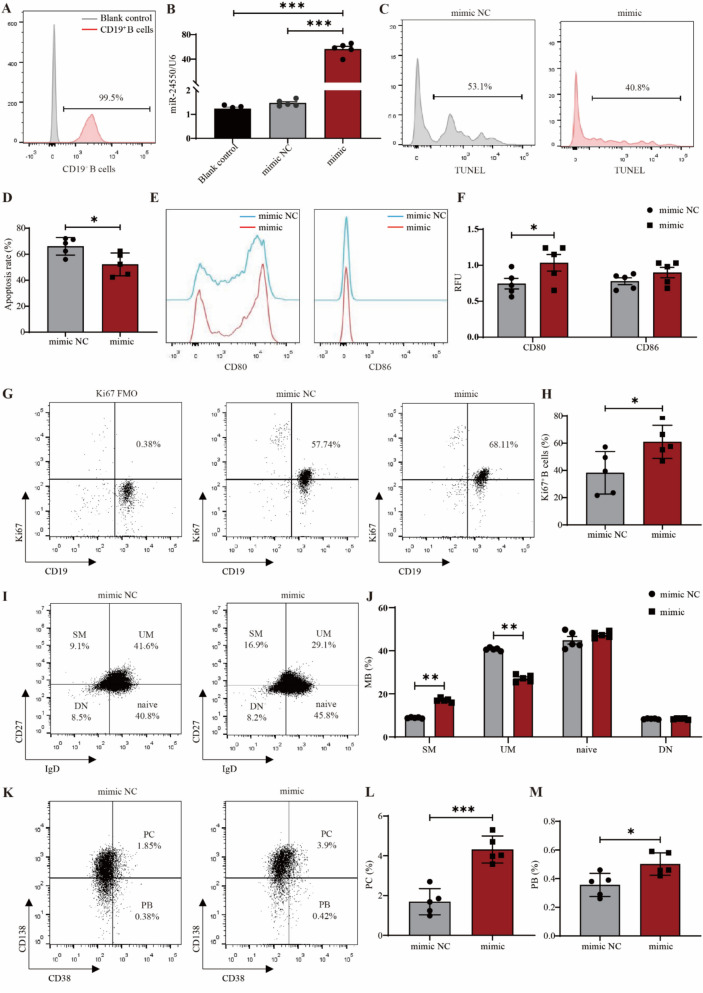

MiR-24550 promotes B cell proliferation

Currently, the regulatory effect of miR-24550 on B-cell function remains unknown. Hence, we overexpressed miR-24550 in B cells using electroporation to verify the regulatory effects of exogenously supplied miR-24550 on B-cell functions such as apoptosis, activation, proliferation, and subsets. B cells were extracted from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers at 99.5% purity, which was confirmed using flow cytometry (Fig. 5A). Subsequently, we constructed a B-cell overexpression model for miR-24550. qRT-PCR validation showed that miR-24550 expression significantly increased in the overexpression group (P = 0.0003; P = 0.0003) (Fig. 5B). B cells were activated with anti-IgM, sCD40L, IL-4, and IL-21 (simulating the activation model of SLE patient B cells) to observe the effects of miR-24550 overexpression on B-cell function.

Fig. 5.

MiR-24550 promotes B-cell differentiation and activation. A Flow cytometric analysis of CD19+ B cell purity before and after negative selection. B qPCR analysis of miR-24550 overexpression efficiency in B cells (n = 5). C TUNEL assay to detect the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on B-cell apoptosis. D Statistical analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on B-cell apoptosis (n = 5). E Flow cytometric analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on the expression of the B-cell activation markers CD80 and CD86. (F) Statistical analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on the expression of the B-cell activation markers CD80 and CD86 (n = 5). G Flow cytometric analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on the expression of the B-cell proliferation marker Ki-67. H Statistical analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on the expression of the B cell proliferation marker Ki-67 (n = 5). I Flow cytometric analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on memory B-cell subsets. J Statistical analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on memory B-cell subsets (n = 5). K Flow cytometric analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on plasma cells and plasmablasts. L Statistical analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on plasma cells (n = 5). M Statistical analysis of the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on plasmablasts (n = 5). Results are shown as mean ± SEM. B was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. D, F, H, J, L, and M were analyzed by independent-samples t-tests. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

As the use of electroporation to induce changes in B-cell membrane permeability and PI staining to detect B-cell apoptosis is controversial, we used a TUNEL assay to detect the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on B-cell apoptosis. We found that the proportion of FITC+ B cells decreased compared with that of the mimic NC group after overexpressing the miR-24550 mimic. This indicates that exogenous miR-24550 increases the B-cell survival rate (P = 0.0136) (Fig. 5C–D).

Additionally, miR-24550 overexpression significantly promoted the expression of the B-cell activation marker CD80 but exerted no significant effect on CD86 expression (P = 0.0445) (Fig. 5E–F). This indicates that miR-24550 promotes B-cell activation. Next, we used flow cytometry to detect the B-cell proliferation marker Ki-67 and observe the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on B-cell proliferation. Ki-67 is a nuclear protein that is expressed in all phases of cell proliferation (G1, S, G2, and M) except in the resting phase (G0); hence, it is a marker of cell proliferation [28]. We found that the proportion of CD19+Ki67+ B cells increased compared with that of the mimic NC group after miR-24550 mimic overexpression. This indicates that exogenous miR-24550 promotes B-cell proliferation (P = 0.0229) (Fig. 5G–H).

Finally, we examined the effect of miR-24550 overexpression on B-cell subsets by detecting switched memory B cells (SM), unswitched memory B cells (UM), naïve B cells, double-negative memory B cells (DN), plasma cells (PC), and plasmablasts (PB). The results showed that miR-24550 overexpression increased the proportions of SM (P = 0.0061) (Fig. 5I–J), PC (P = 0.0009) (Fig. 5K–M), and PB (P = 0.0459) (Fig. 5K–M), whereas it reduced the proportion of UM (P = 0.0052) (Fig. 5I–J); however, the changes in the proportion of DN and naïve B cells were not significant. These results indicate that miR-24550 enhances B cell activation. These results indicate that, while differentiation markers were unchanged, miR-24550’s impact on B cell proliferation/activation alone underscores its therapeutic relevance.

B-cell miR-24550 knockdown ameliorates disease progression in humanized SLE mice

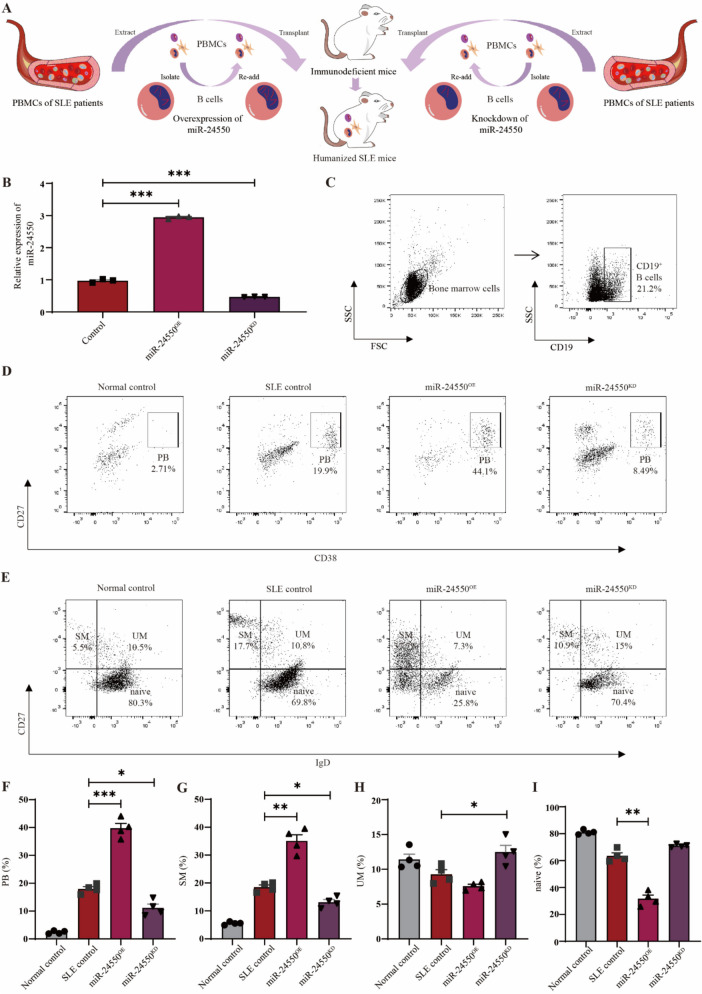

We investigated the effect of miR-24550 intervention in B cells on lupus progression via in vivo experiments. Owing to the poor homology of non-coding RNA between humans and mice and to better simulate the disease state of patients with SLE, we constructed humanized SLE mice by transplanting PBMCs from patients with SLE into immunodeficient mice. To clarify the effect of miR-24550 on B cells, we sorted the B cells after extracting PBMCs from patients with SLE and treated them with miR-24550 before transplanting these B cells together with PBMCs into immunodeficient mice (Fig. 6A). We extracted B cells from the peripheral blood of patients with SLE and constructed B-cell miR-24550 overexpression (miR-24550OE) and knockdown (miR-24550KD) models to assess the transfection efficiency using qRT-PCR. We found that miR-24550 expression was significantly higher in the miR-24550OE group and significantly lower in the miR-24550KD group than that in the Control group. This indicates the successful construction of B-cell miR-24550 overexpression and knockdown models (P = 0.0009; P = 0.0006) (Fig. 6B). Subsequently, miR-24550OE and miR-24550KD B cells were mixed with PBMCs depleted of B cells and injected into immunodeficient mice through the tail vein. Additionally, two immunodeficient mouse groups were included as controls: one injected with PBMCs from patients with SLE without genetic manipulation (SLE control group) and the other with PBMCs from healthy volunteers (normal control group).

Fig. 6.

Construction of humanized SLE mouse models. A Procedure for construction of humanized SLE mouse models. B qRT-PCR analysis of miR-24550 overexpression and knockdown efficiency in B cells from patients with SLE (n = 3). C Flow cytometric analysis of CD19+ B cells from the bone marrow of humanized SLE mice. D Flow cytometric analysis of plasmablasts (PB) from the bone marrow of humanized SLE mice. E Flow cytometric analysis of memory B cells from the bone marrow of humanized SLE mice. F Statistical analysis of PB proportion in bone marrow of humanized SLE mice (n = 4). G Statistical analysis of switched memory (SM) B-cell proportion in bone marrow of humanized SLE mice (n = 4). H Statistical analysis of unswitched memory (UM) B-cell proportion in bone marrow of humanized SLE mice (n = 4). I Statistical analysis of naïve B cell proportion in bone marrow of humanized SLE mice (n = 4). Results are shown as mean ± SEM. B, F, G, H, and I were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

The bone marrow is a crucial central immune organ and primary site for antibody production following humoral immune responses [29]. Bone marrow extracted from humanized mice was subjected to flow cytometry. A significant number of human CD19+ B cells were detected, which confirmed the successful humanization of the immunodeficient mice (Fig. 6C). Analysis of human CD19+ B-cell subsets showed that the SLE control group exhibited higher proportion of CD27+ CD38+ plasmablasts (P = 0.0009; P = 0.0316) and CD27+ IgD− switched memory B cells (P = 0.0065; P = 0.0105) and lower proportion of CD27+ IgD+ unswitched memory B cells (P = 0.1499; P = 0.0359) and naïve B cells (P = 0.050; P = 0.0677) compared with that of the normal control group (Fig. 6D–I). This indicates the successful construction of the humanized lupus mouse model. Furthermore, the numbers of CD27+ CD38+ plasmablasts and CD27+ IgD− switched memory B cells increased in the miR-24550OE group, whereas the proportion of these cells decreased in the miR-24550KD group, which also exhibited an increase in the numbers of unswitched memory B cells and naïve B cells compared with that of the SLE control group (Fig. 6D–I). These findings suggest that miR-24550 knockdown in B cells ameliorates B-cell differentiation in humanized lupus mice.

SLE is a chronic autoimmune disease that is characterized by excessive adaptive immune responses, which lead to autoantibody production and multiple organ damage [27]. An ELISA performed on peripheral blood from humanized mice to detect autoantibodies showed significantly higher levels of antinuclear antibodies—particularly that of anti-nuclear (P = 0.0183; P = 0.0363) (Fig. 7A) and anti-dsDNA (P = 0.0281; P = 0.0317) (Fig. 7B)—in the miR-24550OE group than in the SLE Control group; in contrast, the miR-24550KD group showed significantly lower levels of these autoantibodies. This suggests that miR-24550KD in B cells notably reduces autoantibody expression in humanized lupus mice. IFN-γ is a key cytokine that promotes autoantibody production in the body [30]. The cytometric bead array (CBA) performed for the detection of IFN-γ in the peripheral blood of humanized mice showed significantly elevated IFN-γ levels in the miR-24550OE group but a decreasing trend in the miR-24550KD group (P = 0.028; P = 0.1921) (Fig. 7C). IL-17 contributes to autoimmune and inflammatory responses [31]. Its level was significantly high in the miR-24550OE group and low in the miR-24550KD group (P = 0.0443; P = 0.0076) (Fig. 7D). Additionally, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-12P70 are important inflammatory cytokines. However, only TNF-α (P = 0.0026; P = 0.6813) was highly expressed in the miR-24550OE group of humanized model mice; moreover, the IL-4 and IL-12P70 levels did not differ significantly among the groups (Fig. 7E–G). The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 curbs the production of cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α [32]. Its level was significantly higher in the miR-24550KD group than in the SLE control group (P = 0.6862; P = 0.0385) (Fig. 7H). Overall, miR-24550 knockdown in B cells significantly reduced proinflammatory cytokine expression in humanized lupus mice.

Fig. 7.

B-cell miR-24550 knockdown ameliorates disease progression in humanized SLE mice. A Statistical analysis of plasma antinuclear antibodies in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). B Statistical analysis of plasma anti-dsDNA antibodies in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). C Statistical analysis of plasma IFN-γ in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). D Statistical analysis of plasma IL-17 in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). E Statistical analysis of plasma TNF-α in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). F Statistical analysis of plasma IL-4 in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). G) Statistical analysis of plasma IL-12P70 in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). H Statistical analysis of plasma IL-10 in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). I Morphological analysis of spleen morphology in humanized SLE mice. J Statistical analysis of spleen weight–body weight ratio in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). K H&E staining analysis of spleen pathology in humanized SLE mice. L Immunofluorescence staining analysis of plasma cells (PC) in the spleen of humanized SLE mice. M Statistical analysis of 24-h urinary protein levels in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). N Statistical analysis of plasma urea level in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). O Statistical analysis of plasma creatinine level in humanized SLE mice (n = 4). P H&E, PAS, and MASSON staining analysis of kidney pathology in humanized SLE mice. Q Immunofluorescence staining analysis of IgG and C3 deposition in the kidneys of humanized SLE mice. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J, M, N, and O were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

The spleen of the humanized mice was significantly enlarged in the miR-24550OE group and reduced in the miR-24550KD group compared with that in the SLE Control group (Fig. 7I). The spleen weight-to-body weight ratio followed a similar pattern and was higher in the miR-24550OE group and lower in the miR-24550KD group (P = 0.0036; P = 0.0050) (Fig. 7J). H&E staining of the humanized lupus mouse spleen showed increased immune cell infiltration in the miR-24550OE group and decreased infiltration in the miR-24550KD group than that in the SLE Controls (Fig. 7K). These findings indicate that miR-24550KD in B cells significantly reduces immune cell overproliferation in the spleen. Immunofluorescence staining showed that the proportion of plasma cells was higher in the miR-24550OE group and lower in the miR-24550KD group than that in the SLE Control group (Fig. 7L). This suggests that miR-24550 knockdown in B cells significantly reduces plasma cell numbers and suppresses abnormal B-cell activation.

SLE frequently affects the kidneys in approximately 50% of patients [33]. We analyzed the 24-h protein levels in urine samples from humanized mice and found that they were significantly higher in the miR-24550OE group and lower in the miR-24550KD group than those in the SLE Control group (P = 0.0411; P = 0.0483) (Fig. 7M). Plasma kidney function markers showed a similar trend, with increased urea (P = 0.2256; P = 0.0039) and creatinine (P = 0.0125; P = 0.0423) levels in the miR-24550OE group and decreased levels in the miR-24550KD group (Fig. 7N–O). Histological analysis via H&E and PAS staining showed increased renal crescent formation and brush border detachment in the miR-24550OE group, whereas crescent formation was reduced and detachment was improved in the miR-24550KD group compared with that of the SLE Control group. MASSON staining indicated high renal fibrosis in the miR-24550OE group and low fibrosis in the miR-24550KD group. This suggests improved renal pathology (Fig. 7P). Immunofluorescence for IgG and C3 in the kidney tissues showed increased deposition in the miR-24550OE group and decreased deposition in the miR-24550KD group than in the SLE Control group (Fig. 7Q). These findings suggest that miR-24550 knockdown in B cells enhances kidney function in humanized SLE mice.

Overall, disease progression in humanized SLE mice mirrored the effects observed on inhibition of basophil exosome release in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice. This indicates that basophil-derived exosomes regulate B cells primarily through miR-24550.

MiR-24550 promotes B-cell proliferation and activation by inhibiting KLF5 expression

MiRNAs are a class of endogenous non-coding small RNAs that downregulate target gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. Specifically, miRNAs act by binding to the 3′-UTR of target mRNAs and repressing protein production by destabilizing mRNA and translational silencing [34]. We performed bioinformatic prediction to identify the target protein that enables miR-24550-mediated suppression of B-cell activation. We found that miR-24550 specifically binds to the 3′-UTR of Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) (Fig. 8A). KLF5 is a member of the Krüppel-like transcription factor family and a zinc finger protein that is involved in diverse biological processes such as embryonic development, cellular proliferation, differentiation, and stress response. KLF5 acts as either a transcriptional activator or repressor, and its role in cell growth and survival varies depending on the cellular and genetic contexts [35].

Fig. 8.

MiR-24550 promotes B cell activation by inhibiting KLF5 expression. A Bioinformatic prediction of miR-24550 targeting KLF5. B qRT-PCR analysis of miR-24550 levels in B cells in healthy volunteers and patients with SLE (n = 3). C qRT-PCR analysis of KLF5 levels in B cells from healthy volunteers and patients with SLE (n = 3). D qRT-PCR analysis of KLF5 levels following miR-24550 overexpression in B cells (n = 5). E qRT-PCR analysis of KLF5 levels following miR-24550 knockdown in B cells (n = 5). F qRT-PCR analysis of KLF5 levels after modulation of B-cell miR-24550 level (n = 3). G Flow cytometric analysis of CD80 levels post-KLF5 knockdown in B cells. H Statistical analysis of CD80 levels post-KLF5 knockdown (n = 5). I Flow cytometric analysis of CD86 levels post-KLF5 knockdown in B cells. J Statistical analysis of CD86 levels post-KLF5 knockdown (n = 5). K Statistical analysis of IgG secretion following KLF5 modulation in B cells (n = 5). L Correlation between miR-24550 and KLF5 expression. M Correlation among miR-24550, KLF5, CD80, CD86, and IgG expression levels (n = 15). N Dual-luciferase reporter plasmid design for miR-24550 targeting KLF5. O Dual-luciferase reporter gene analysis of miR-24550 for targeting KLF5 (n = 3). Results are shown as mean ± SEM. B, C, D, E, and O were analyzed by independent-samples t-tests. F, H, J, and K were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. L was analyzed by Spearman correlation analyses. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

We hypothesize that miR-24550 exerts its biological effects by targeting the 3′-UTR of KLF5. Examining miR-24550 and KLF5 expression in B cells from patients with SLE showed that miR-24550 expression level increased (P = 0.0006) (Fig. 8B), whereas that of KLF5 decreased (P = 0.0008) (Fig. 8C) in B cells from patients with SLE compared with that in the normal control group. Next, we overexpressed and knocked down miR-24550 in B cells and found that miR-24550 overexpression reduced KLF5 expression (P = 0.0002) (Fig. 8D), whereas its knockdown increased KLF5 expression (P = 0.0003) (Fig. 8E). This further confirms our hypothesis that miR-24550 targets KLF5 to regulate B cells. Next, we examined the effect of KLF5 knockdown and overexpression on B-cell activation. qRT-PCR results confirmed the successful establishment of B cell models with KLF5 knockdown and overexpression (P = 0.0038; P = 0.0001) (Fig. 8F). Flow cytometric results indicated that KLF5 knockdown in B cells significantly increased the expression levels of the activation markers CD80 (P = 0.0041; P = 0.0001) and CD86 (P = 0.0006; P = 0.0003), whereas KLF5 overexpression significantly reduced these levels (Fig. 8G–J). Investigating the effects of KLF5 knockdown and overexpression on antibody release from B cells from patients showed that KLF5 knockdown in B cells significantly increased IgG release, whereas KLF5 overexpression significantly reduced IgG release. This result was consistent with the previous observations for CD80 and CD86 (P = 0.0351; P = 0.0007) (Fig. 8K). Correlation analysis showed a significant negative correlation between miR-24550 and KLF5 expression levels (Fig. 8L); furthermore, miR-24550 correlated positively with CD80, CD86, and IgG levels, whereas KLF5 level correlated negatively with those of these markers (Fig. 8M).

We performed a dual-luciferase reporter gene assay to clarify the target-binding relationship between miR-24550 and KLF5 (Fig. 8N). The experiment included four groups: WT + miR-24550 mimic, WT + mimic negative control, MUT + miR-24550 mimic, and MUT + mimic negative control. The results showed that the relative luciferase expression in the wild-type plasmid (KLF5-WT-3′-UTR) + miR-24550 group was significantly lower than that in the wild-type plasmid (KLF5-WT-3′-UTR) + miR-NC group. This indicates that miR-24550 binds to the wild-type KLF5 3′-UTR and suppresses its expression. However, luciferase expression did not significantly differ between the mutant plasmid groups (KLF5-MUT-3′-UTR) + miR-NC and (KLF5-MUT-3′-UTR) + miR-24550. This indicates that miR-24550 cannot bind to the mutant KLF5 ′ (P = 0.4157; P = 0.0002) (Fig. 8O). These results show that miR-24550 targets and binds to KLF5, thereby inhibiting its expression.

Overall, we have found that basophil-derived exosomal miR-24550 promotes B-cell activation by targeting KLF5, thereby exacerbating SLE progression. These findings provide new insights into the prevention and treatment of SLE.

Discussion

Exosome functions in SLE

SLE is a complex autoimmune disease that is characterized by the disruption of B-cell self-tolerance and the generation of numerous autoantibodies that trigger inflammation and tissue damage [36]. Basophils are crucial to SLE pathogenesis because of their significant immunoregulatory functions [4]. Exosomes are extracellular vesicles that facilitate intercellular communication and contain numerous non-coding RNAs, lipids, and proteins that exert regulatory effects between cells [23]. Nevertheless, the secretion of exosomes by basophils and their biological functions are yet to be clarified. In this study, we co-cultured human basophil-derived exosomes with B cells from patients with SLE and showed that these exosomes are internalized by B cells, which confirms the existence of a communication pathway between basophils and B cells through exosome release. Furthermore, we have observed that the B cells that internalized the basophil-derived exosomes exhibited significantly improved survival and proliferation rates. This finding suggests that basophil-derived exosomes may play a role in modulating B-cell activity in SLE. Overall, our findings demonstrate that basophil-derived exosomes play a crucial role in facilitating communication between basophils and B cells, thereby contributing to SLE pathogenesis by promoting B cell activation and autoantibody production. This understanding forms the basis for investigating the specific molecular mechanisms underlying this interaction. This study highlights the importance of basophil-derived exosomes in facilitating communication between basophils and B cells. Therefore, targeting these exosomes or their cargo could provide a new approach to modulating immune responses in SLE.

In vivo findings

We developed a Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mouse model to investigate the in vivo effects of basophils and their exosomes. Upon transfer into lupus mice, the mouse basophil-derived exosomes predominantly targeted the spleen and kidneys and showed minimal presence in the lungs and heart. This indicates a primary role for basophil-derived exosomes in these organs. The spleen is a key peripheral immune organ that is crucial for B-cell proliferation and differentiation and maintenance of immune balance [37]. Upon antigenic stimulation, B cells differentiate into plasma cells that produce antibodies against pathogens [38]. Basophil-derived exosomes stimulate excessive splenic immune cell proliferation, which disrupts the balance between plasma cells and plasmablasts. The kidney is a target for basophil-derived exosomes and is frequently affected in SLE; therefore, we assessed renal function in the lupus mouse model [27]. Inhibition of basophil-derived exosomes reduced urinary protein and urea levels in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice, which suggests a role in nephron preservation and urea and creatinine accumulation in lupus. Pathological assessments showed that exosome inhibition improved kidney pathology, decreased fibrosis, and reduced immune complex deposition. This indicates that basophil-derived exosomes contribute to lupus nephritis progression. This study used a Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mouse model and has shown that basophil-derived exosomes primarily target the spleen and kidneys. In the spleen, they stimulate excessive immune cell proliferation, which disrupts the balance between plasma cells and plasmablasts. In the kidneys, exosome inhibition reduced urinary protein and urea levels, which improved kidney pathology, decreased fibrosis, and reduced immune complex deposition. This indicates that basophil-derived exosomes play a role in lupus nephritis progression. Overall, these findings suggest that basophil-derived exosomes play a particularly significant role in SLE pathology in the spleen and kidneys and could be potential therapeutic targets.

Molecular mechanisms of miR-24550

Furthermore, we investigated the molecular mechanism underlying basophil-derived exosomes in lupus pathogenesis. Transcriptomic analysis of control and anti-IgE basophil group exosomes showed a significant upregulation of miR-24550 upon basophil activation. Co-culturing the activated exosomes with B cells from patients with SLE increased miR-24550 expression. This suggests that activated basophils package miR-24550 into exosomes to regulate recipient cells; thus, miR-24550 potentially acts as a key molecule in this process. miRNAs are non-coding single-stranded RNAs that are approximately 20–24 nucleotides in length. They regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to the 3′-UTR of mRNAs, which causes mRNA degradation or translational inhibition [24]. As carriers of intercellular communication, exosomes transport miRNAs to recipient cells and modulate cellular functions. To elucidate the effect of miR-24550 on B cells, we performed in vivo experiments to assess the effect of modulating B-cell miR-24550 on lupus progression. To mimic the human disease state more accurately, we constructed humanized SLE mice by transplanting PBMCs from patients with SLE into immunodeficient mice and isolated the B cells for miR-24550 intervention. The bone marrow is a central immune organ that is crucial for antibody production during humoral immune responses [29]. We detected a significant number of human CD19+ B cells in the bone marrow of humanized SLE mice, which validated the humanization of the model. Analysis of human CD19+ B-cell subsets showed that CD27+ CD38+ plasmablasts and CD27+ IgD− switched memory B cell levels increased in the SLE control group, whereas those of CD27+ IgD+ unswitched memory B cells and naïve B cells decreased. These results validate our humanized lupus mouse model. The CD27+ CD38+ plasmablast and CD27+ IgD− switched memory B cell levels decreased in the miR-24550KD group compared with those of the miR-24550OE and SLE control groups, whereas those of CD27+ IgD+ unswitched memory B cells and naïve B cells increased. This indicates improved bone marrow B-cell differentiation in humanized SLE mice owing to B-cell miR-24550KD. However, the DN population remained unchanged. As DN B cell population is of particular interest in SLE owing to its potential role in disease pathology, we have carefully considered the factors that may be attributed to the lack of observed change in this population in this study: (1) Sample heterogeneity: SLE is a highly heterogeneous disease, and the patient samples used in our study may have varying levels of disease activity and genetic backgrounds [39]. This heterogeneity could influence the representation and behavior of different B cell subsets, including DN memory B cells. (2) Disease stage: The disease stage of the patients included in this study may also play a role. DN memory B cells may be more prevalent or active in specific phases of SLE, and our study may not have captured the population during the critical time point [40]. Additionally, inhibiting B-cell miR-24550 significantly improved renal function in humanized SLE mice, which mirrors the effects observed for inhibition of basophil release in Pristane-Mcpt8flox/flox, CAGGCre−ERTM lupus mice. This suggests that basophil exosome regulation of B cells is primarily mediated by miR-24550.

Therapeutic implications

Our findings suggest that miR-24550 and basophil-derived exosomes could act as novel therapeutic targets for SLE. The understanding of the role of miR-24550 in promoting B-cell activation and autoantibody production could enable researchers to develop strategies to inhibit this miRNA and mitigate its pathological effects. The discovery of the role of miR-24550 in SLE pathogenesis opens avenues for the development of miRNA-based therapies. These may include the use of miRNA inhibitors or mimics to modulate immune responses and reduce disease severity. Understanding the specific mechanisms through which basophils and miR-24550 contribute to SLE pathogenesis may enable the development of personalized treatment strategies tailored to individual patient disease profiles. However, these therapeutic strategies in preclinical models and clinical trials need to be further validated to assess their safety and efficacy in human SLE patients. In summary, investigating miR-24550 showed that this miRNA is a key mediator of basophil-derived exosome-induced B cell activation. Its upregulation in SLE patients and its role in promoting B cell proliferation and activation highlight its significance as a potential therapeutic target and present broader implications for the findings of this study in clinical applications and future research directions.

KLF5 is a member of the Krüppel-like transcription factor family and is a zinc finger protein that is involved in various biological processes, including embryonic development, cell proliferation, differentiation, and stress response. Its function as a transcriptional activator or repressor varies based on the cellular and genetic contexts [35]. We performed bioinformatic prediction and identified KLF5 as a target of miR-24550 that specifically binds to the 3′-UTR of KLF5. CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2) are costimulatory molecules that are expressed in antigen-presenting cells and B cells, respectively. They are crucial for B-cell activation and differentiation, and their roles differ in various immune contexts [41]. KLF5 modulation in B cells significantly influenced CD80 and CD86 expression; moreover, KLF5 knockdown and overexpression increased and decreased these levels, respectively. Furthermore, KLF5 knockdown increased IgG release, whereas its overexpression reduced it. These results concur with the observed changes in CD80 and CD86 expression. A dual-luciferase reporter gene assay confirmed that miR-24550 targets KLF5 and inhibits its expression. Thus, the transcription factor KLF5 plays a crucial role in regulating B-cell activation and function. Our findings indicate that miR-24550 directly targets KLF5, thereby modulating its expression. KLF5 is known to influence the expression of CD80 and CD86, which are critical co-stimulatory molecules involved in B-cell activation and immune responses [42]. Therefore, KLF5 downregulation may cause miR-24550 to affect the expression of these molecules, which would ultimately impact B-cell activation and autoantibody production in SLE.

Limitations and future directions