Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

The prevalence of myopia has been rising, whereas prevention efforts have shown limited success. Educational short videos have become crucial sources for health information; however, their quality regarding myopia prevention is uncertain. This study aimed to evaluate the quality and content of short videos on myopia prevention disseminated via major Chinese short video platforms and compare content differences between healthcare professionals and non-professional creators.

Design

A cross-sectional content analysis.

Setting

Top-ranked videos from three dominant Chinese platforms (TikTok, Kwai and BiliBili) in 6–10 August 2024.

Participants

284 eligible videos screened from 300 initial results using predefined exclusion criteria, including 97 videos from TikTok, 94 from BiliBili and 93 from Kwai.

Methods

Videos were assessed using the Global Quality Scale and a modified DISCERN tool. Content completeness was evaluated across six predefined domains. Videos were categorised by source (healthcare professionals vs non-healthcare professionals), and intergroup differences were statistically analysed.

Results

Of the 284 videos, 48.9% were uploaded by healthcare professionals and 51.1% by non-healthcare professionals. Overall video quality was suboptimal. Videos by ophthalmologists had significantly higher quality scores than those by other creators. Healthcare professionals focused more on definitions, symptoms and risk factors of myopia, whereas non-healthcare professionals emphasised prevention and treatment outcomes. Ophthalmologists more frequently recommended corrective lenses (including both standard spectacles and specially designed lenses for myopia control) and low-dose atropine, whereas non-healthcare professionals favoured vision training.

Conclusions

Significant quality gaps exist in myopia prevention videos. Healthcare professionals, particularly ophthalmologists, produce higher-quality and more comprehensive content. Strategic engagement by healthcare professionals in digital health communication and platform-level quality control is needed to improve public health literacy on myopia.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, OPHTHALMOLOGY, Myopia

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study applied validated tools (Global Quality Scale and modified DISCERN) to systematically assess the quality of short videos on myopia prevention.

This study only included videos published in Chinese, which may limit the generalisability to other language contexts.

Video quality was independently assessed by three ophthalmologists, but potential assessor bias cannot be entirely excluded.

A cross-sectional design was used, limiting causal inference about video content trends over time.

Introduction

Myopia has become a global public health problem, especially with the increasing rate of myopia among children and adolescents.1 The visual impairment caused by myopia not only diminishes an individual’s quality of life but also poses substantial socio-economic burdens.2 In Asian countries, 10%–20% of students suffer from high myopia, which continues to progress. Patients with myopia have an increased risk of developing myopic macular degeneration, retinal detachment, cataracts and glaucoma, and the risk increases as the level of myopia increases.3 Therefore, controlling myopia has become crucial for the ocular health of young populations, and targeted prevention strategies are essential for minimising both incidence and progression. Effective preventive measures, such as using low-concentration atropine, increasing outdoor activity time and wearing off-focus glasses, have been established.4 These methods have effectively reduced the occurrence and progression of myopia to some extent,5,11 but they have not been widely applied, especially in rural and town areas where medical resources are relatively scarce. In these areas, providing good health prevention guidance for patients with myopia is challenging, so there is an urgent need for more portable and effective health education measures for myopia control that can be widely disseminated.

In this digital age, social media has become an important platform for information dissemination, and the internet is one of the simplest ways to obtain information.12 Nowadays, patients can easily access a wide range of medical information, and 60.42% of the global population owns a smartphone.13 People are also increasingly searching for professional health and wellness-related information on social media.14 In recent years, short video-sharing platforms have attracted a large number of young users with their rich visual content. Ordinary people can search related keywords on short videos to quickly obtain the health information they want. At the same time, some professional doctors and educators have the opportunity to disseminate relevant health knowledge in an interesting and engaging way through these short video-sharing platforms. The dissemination of these short videos not only makes complex medical knowledge easy to understand but also enables people from different economic regions to receive the same health information in the same way.

In China, TikTok, BiliBili and Kwai are among the most popular short video-sharing platforms, with daily active users reaching hundreds of millions of people. 15,19More and more people are inclined to obtain health information they are interested in from short video-sharing platforms instead of going to the hospital when it is unnecessary. However, the quality of information on social media varies, and inaccurate or misleading content may negatively affect the public’s health awareness. Previous studies have shown that the reliability of some online health information is often difficult to verify, and many health information sources are released by non-professionals.20 This leads to people receiving a variety of health information, which may negatively affect patients’ health. Therefore, it is particularly important to identify and promote high-quality myopia prevention information on short video-sharing platforms. However, compared with traditional health information dissemination methods, the effectiveness and accuracy of conveying myopia prevention knowledge on short video-sharing platforms remain uncertain, and the overall quality of short videos is unknown. This study aimed to evaluate the quality of myopia prevention information on TikTok, BiliBili and Kwai through a cross-sectional study by analysing relevant short videos. Furthermore, it proposes suggestions for improving the dissemination of health information on social media.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

All original short video materials were sourced from three Chinese platforms: TikTok, BiliBili and Kwai. In 6–10 August 2024, we searched the top 100 videos on each platform using the keywords ‘myopia prevention’ and ‘myopia control’. To minimise targeted recommendations, a new smartphone with newly registered accounts was used. No videos were downloaded, re-uploaded, liked or commented on during the study to maintain the integrity of data collection.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) duplicate videos, (2) advertising videos, (3) videos unrelated to myopia, (4) non-Chinese videos, (5) videos without images, (6) videos with content that may cause discomfort, (7) videos without sound and (8) videos <10 s in length. Applying these criteria, 16 videos were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 284 videos. Each video underwent review and evaluation by three independent assessors, with the evaluator’s identity and classifications anonymised to prevent bias. All assessors were ophthalmologists with at least 3 years of clinical experience. Collected data encompassed publication date, uploader’s identity, healthcare professional titles, video content, duration, likes, shares, comments and saves.

Video Quality Assessment

Each video was meticulously reviewed by three independent evaluators using the Global Quality Score (GQS) and the modified DISCERN (DIS) tool. The GQS, a tool for evaluating video quality, was used; the video content was assessed in five aspects, including the quality of information accuracy, which refers to whether the video creator accurately and comprehensively mentioned myopia prevention and control methods that are supported by medical evidence. The assessment of video content accuracy was based on both Chinese and international guidelines for myopia prevention and control, 21,23as well as recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses related to myopia management, 24,26completeness, transparency, understandability, interaction and update frequency, with scores ranging from 0 to 5 in each aspect, and the total score was recorded as 0–25 points.27 The modified DIS tool mainly assessed video quality through five questions: (1) Is the video clear, concise and easy to understand? (2) Is the content presented in a balanced and unbiased manner? (3) Does the video include valid citations? (4) Are additional sources of information provided? (5) Are areas of uncertainty or limitations in the topic acknowledged? Scores of 1 or 0 were based on whether the answer was ‘yes’ or ‘no’, with a minimum score of 0 (maximum score of 5) . 28Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a senior reviewer. To minimise platform-driven algorithmic bias, the video search and collection were conducted using a new smartphone with newly registered accounts. The URLs of the eligible videos were saved and distributed to the assessors via a secure shared document. Each assessor accessed and rated the videos using a private browsing mode to avoid recommendation bias.

We recorded whether videos mentioned myopia prevention measures and categorised the specific methods discussed. Additionally, we evaluated whether videos addressed myopia’s definition, symptoms, risk factors, potential consequences, treatment outcomes and adverse effects, scoring the completeness of these aspects. Healthcare professionals were identified by certification and further categorised into ophthalmologists and non-ophthalmologists. Non-professionals were classified into four groups: science communicators, patients with myopia or family members, non-profit organisations or individuals and official news media.

Video quality was compared across healthcare and non-healthcare professional categories, analysing video length, likes, shares, saves, DIS scores and GQS. Further comparisons were conducted regarding content focus and emphasis, assessing statistical significance between different creator categories.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics on the duration, likes, favourites and shares of the 284 videos were conducted, focusing on the maximum, minimum, median and quartiles. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to evaluate whether the GQS and DIS scores of the 284 videos were normally distributed. When the data were normally distributed, a two-sample T-test was conducted, with the values expressed as the mean±SD. When the data were not normally distributed, the Mann−Whitney test was used, with the median and quartiles used to represent the data. The χ2 test was used to compare the number of methods proposed by different categories of people for myopia control; p<0.05 indicates statistically significant differences.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Overview of the videos

A total of 284 short videos were selected from the top 100 videos on TikTok, BiliBili and Kwai (figure 1). Among them, 48.9% were shot by professional healthcare workers, whereas the remaining 51.0% were created and uploaded by non-professionals (table 1). The sources of video publishers were further categorised. Among the videos, the most were uploaded by ophthalmologists and optometrists (85/284, 29.9%), followed by non-ophthalmologists (54/284, 19.0%). The videos uploaded by non-healthcare professionals were divided into four categories: science bloggers, news organisations, non-profit organisations or individuals and patients or their family members. Among them, the most were uploaded by non-profit organisations or individuals (89/284, 31.3%), followed by patients or their family members (36/284, 12.7%), science bloggers (15/284, 5.3%) and news organisations (5/284, 1.8%).

Figure 1. Flowchart of videos related to myopia prevention and control included in this study.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sources of videos related to myopia prevention and control (n = 284).

| Source | Description | Videos, n (%) Total |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare professionals | ||

| Ophthalmologist or optometrist | Certified ophthalmologist or optometrist specialising in ophthalmology | 85 (29.9) |

| Non-ophthalmologist or optometrist | Certified doctor or nurse practitioner specialising in other medical fields except ophthalmology | 54 (19.0) |

| Overall | 139 (48.9) | |

| Non-healthcare professionals | ||

| Non-profit organisations and individuals | Organisations and public hospitals that operate in the collective, public or social interest and individuals | 89 (31.3) |

| Patients or relatives | Patients who have undergone surgery for myopia or their relatives | 36 (12.7) |

| Science blogger | Individuals engaged in the dissemination of scientific knowledge | 15 (5.3) |

| News agents | News agencies and the press | 5 (1.8) |

| Overall | 145 (51.1) |

Comparison of video quality between healthcare and non-healthcare professionals

The collected videos ranged in length from 11 to 1271 s, with a median duration of 81 s. The median number of likes was 2030 (IQR, 437.5–12,000), and the medians for bookmarks and shares were 949 (IQR, 196.25–4775.75) and 617 (IQR, 151–3694), respectively.

Videos posted by non-healthcare professionals were notably longer, with a median length of 110 s compared with 72 s for those by healthcare professionals (p=0.0027). Additionally, videos by non-healthcare professionals garnered significantly higher median likes (6086 vs 1098, p<0.01), bookmarks (1706 vs 572, p<0.01) and shares (1150 vs 365, p<0.01) than those posted by healthcare professionals.

The GQS and modified DIS scores were compared between healthcare and non-healthcare professionals. The median GQS was significantly higher for healthcare professionals (16, IQR 14–17) than for non-healthcare professionals (13, IQR 11.5–15, p<0.001). Similarly, the median DIS scores were higher for videos posted by healthcare professionals (2, IQR 2–3) than for those by non-healthcare professionals (2, IQR 1–2, p<0.001), with statistically significant differences in both metrics.

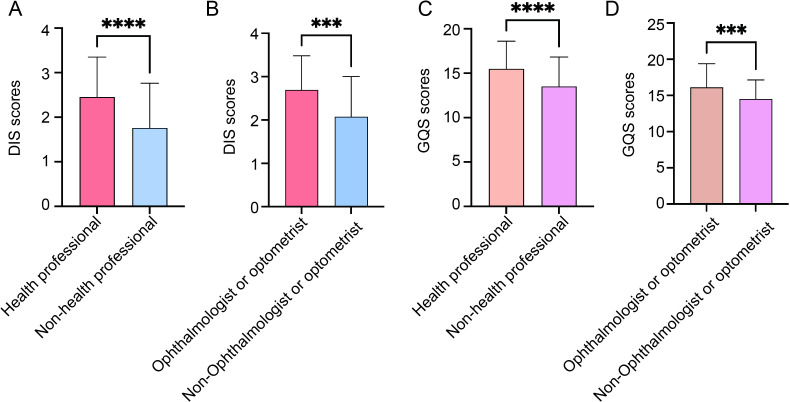

Further analysis of videos from within the healthcare professional category revealed distinctions between ophthalmologists and non-ophthalmologists (table 2). Videos by ophthalmologists received fewer median likes (996 vs 1198, p=0.0027) and bookmarks (385 vs 862, p=0.0204) than those by non-ophthalmologists. The median number of shares for ophthalmologists vs non-ophthalmologists was 51 vs 201.5, although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.2420). However, the quality scores favoured videos by ophthalmologists, with a higher median DIS score (3, IQR 2–3), compared with those by non-ophthalmologists (2, IQR 1–3, p=0.0002) and a higher median GQS (16, IQR 14.5–19) compared with those by non-ophthalmologists (14, IQR 13–16, p=0.0003). These differences were statistically significant, as illustrated in figures2 3.

Table 2. Characteristics of videos on myopia prevention and control .

| Characteristics | N=284 |

|---|---|

| Video duration (s), median, IQR | 81 (53.25–168.75) |

| Number of likes, median, IQR | 2030 (437.5–12000) |

| Number of comments, median, IQR | 179 (47.25–868.5) |

| Number of shares, median, IQR | 617 (151–3694) |

| Number of collections, median, IQR | 949 (196.25–4775.75) |

| DISCERN score, median, IQR | 2 (1–3) |

| GQS, median, IQR | 14 (12–17) |

| Myopia prevention and control methods (n, %) | |

| Mentioned | 274 (96.5) |

| Not mentioned | 10 (3.5) |

| Myopia treatment outcomes (n, %) | |

| Mentioned | 239 (84.2) |

| Not mentioned | 45 (15.8) |

| Adverse effects (n, %) | |

| Mentioned | 83 (29.2) |

| Not mentioned | 201 (70.7) |

DIS, DISCERN tool; GQS, Global Quality Score.

Figure 2. Comparison of the median DISCERN (DIS) and Global Quality Score (GQS) in videos posted by different personnel. The distributions of the (A) DIS and (B) GQS among different sources are displayed by the ridge plot.

Figure 3. Comparison of average scores among different personnel. (A) Average DIS scores and significant differences between healthcare and non-healthcare professionals. (B) Average DIS scores and significant differences between ophthalmologists or optometrists and non-ophthalmologists or optometrists. (C) Average GQS and significant differences between healthcare and non-healthcare professionals. (D) Average GQS and significant differences between ophthalmologists or optometrists and non-ophthalmologists or optometrists. GQS, Global Quality Score; DIS, modified DISCERN tool.

Comparison of video content by different personnel

The video contents on the six main aspects of myopia prevention or control (table 3), namely, definition of myopia, symptoms of myopia, risk factors of myopia, methods of myopia prevention and control, results of myopia treatment and possible adverse consequences of myopia treatment, were evaluated to assess the comprehensiveness of the content of each video. The results showed that very few videos could provide comprehensive information on myopia prevention and control, and most videos (70.7%) did not describe the possible adverse reactions of common myopia treatments. Moreover, only a few videos (0.3%) could provide a comprehensive and detailed introduction to the risk factors of myopia. Myopia prevention and control measures were the most frequently mentioned topic, with 96.5% of the videos providing relevant information.

Table 3. Completeness of video content.

| Video content | Definition, n (%) | Signs/symptoms, n (%) | Risk factors, n (%) | Myopia prevention and control methods (n, %) | Outcomes (n, %) | Adverse events (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No content (0 points) | 168 (59.1) | 136 (47.8) | 111 (39.0) | 10 (3.5) | 45 (15.8) | 201 (70.7) |

| Little content (0.5 points) | 68 (23.9) | 110 (38.7) | 95 (33.4) | 111 (39.0) | 191 (67.2) | 53 (18.6) |

| Some content (1 point) | 20 (7.0) | 26 (9.1) | 65 (22.8) | 114 (40.1) | 36 (12.6) | 24 (8.4) |

| Most content (1.5 points) | 19 (6.6) | 10 (3.5) | 12 (4.2) | 47 (16.5) | 9 (3.1) | 5 (1.7) |

| Extensive content (2 points) | 9 (3.1) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) |

Contents were compared between healthcare and non-healthcare professionals, along with their subgroups. Both groups mentioned prevention and control methods; however, healthcare professionals, including those outside ophthalmology, generally offered more comprehensive content, covering definitions, symptoms and risk factors of myopia (figure 4A). Interestingly, non-ophthalmologists tended to have greater coverage than ophthalmologists (figure 4B). Among non-healthcare professionals, news media tended to provide the most comprehensive information, whereas patients or their family members focused more on potential adverse treatment reactions (figure 4C).

Figure 4. Radar map showing comparisons of content comprehensiveness. (A) Between healthcare and non-healthcare professionals. (B) Between ophthalmologists or optometrists and non-ophthalmologists or optometrists. (C) Among science bloggers, patients or relatives, non-profit organisations, news agents and healthcare professionals.

Myopia prevention and control measures mentioned

A statistical analysis of the 12 most frequently mentioned myopia control measures was conducted, which included outdoor activities (engaging in activities in bright light and viewing distant objects), vision training (eye exercises and pilot vision training), improving eye habits (better posture and avoiding prolonged close-up tasks), wearing suitable lenses (‘wearing suitable lenses’ refers to both standard optical correction (eg, single-vision spectacles or soft contact lenses) and specially designed lenses intended for myopia control, such as orthokeratology (Ortho-K), multifocal soft lenses or defocus-incorporated multiple segments (DIMS) lenses), optimising diet (reducing sugary foods and carbonated drinks, increasing lutein intake and consuming more fruits and vegetables), minimising electronic device usage, environmental lighting adjustments (reducing blue light exposure and increasing indoor brightness), using low-concentration atropine eye drops, ensuring sufficient sleep, regular eye check-ups (especially for children with myopic parents), participating in sports (eg, ping-pong and badminton) and using traditional Chinese medicine (acupuncture and massage). Based on current literature, these 12 methods were further categorised according to the strength of supporting scientific evidence. Each intervention was classified as having strong, moderate or limited evidence, following principles of evidence-based medicine and recent systematic reviews. A summary table to present this classification was added (online supplemental material S1).

The frequency of mentions for each method and the total number of methods mentioned per video were analysed to evaluate content richness. As shown in figure 5, outdoor activities emerged as the most popularly mentioned myopia control measure (89 out of 237 videos), followed by vision training and wearing suitable glasses.

Figure 5. Vertical slice plots showing the frequency of mentions of different myopia prevention and control methods. Myopia prevention and control methods were mentioned 469 times in 237 videos.

Among the 237 videos that mentioned myopia control measures, over half (55.9%) discussed only one control measure, whereas 30% included 2–3 methods. A small proportion (3.7%) provided 6–7 control measures.

Preferences for myopia prevention and control recommendations were compared between ophthalmologists and non-ophthalmologists. Ophthalmologists were more likely to recommend wearing suitable lenses (34.1%, p=0.006), engaging in outdoor exercises (28.2%, p=0.58) and using low-concentration atropine (15.2%, p=0.0065). Non-healthcare professionals favoured outdoor exercise (31.7%), vision training (31.0%, p=0.0004) and improving eye habits (18.6%, p=0.2629). Statistically significant differences emerged in preferences for wearing proper lenses (p=0.006), using low-concentration atropine (p=0.0065) and vision training (p=0.0004).

Recommendations from ophthalmologists/optometrists were more likely to include interventions with strong evidence support, such as low-concentration atropine, orthokeratology and increased outdoor time. In contrast, recommendations from other healthcare providers often featured less evidence-based methods, such as vision training, improving eye habits or consuming dietary supplements, which currently lack strong clinical evidence.

Discussion

With the popularisation of electronic products and the improvement of people’s education level, the incidence of myopia is increasing annually. By 2050, myopia is estimated to affect 4.949 billion people worldwide. 29In China, the myopia rate of high school students has reached 80.5%. 30However, the progression of myopia is preventable. The prevention and control of myopia in children and adolescents play an important role in reducing the incidence of myopia and high myopia. 31 Increasing myopia prevention and control awareness among patients with myopia or parents of children with myopia, such as the early signs, risk factors, prevention and control measures of myopia and myopia treatment, can prevent the progression of myopia early and reduce the incidence of high myopia. Breaking the information barrier between doctors and patients may reduce the incidence of myopia.32

According to the 59th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development, by June 2024, the country had nearly 1.1 billion Internet users, and the Internet penetration rate will reach 78.0%, among which short video users account for 95.5% of the overall Internet users, 33 which means that nearly everyone in China can obtain or receive information through short videos on their mobile phones. Compared with traditional text science popularisation, short videos have the advantages of easy acceptance, easy understanding and easy dissemination. 34 Moreover, studies have shown that the use of short video-sharing platforms may help the population gain theoretical and practical knowledge, 35 and short video-sharing platforms may be effective at influencing the behaviour of the population. 36 The 284 short videos collected in this study received a total of 16.08 million likes, 320 000 comments and 1.53 million shares, indicating that videos related to myopia prevention and control are widely watched and disseminated. Health education for patients and their families through short videos is economical and effective. However, the quality of videos on short video-sharing platforms varies, 37and information sources of some videos are not transparent or even wrong, 38 which may mislead patients with myopia and their families, causing them to miss the best time for myopia prevention and control and waste time and money. In addition, most short videos cannot provide complete and accurate information for patients. 39 Ophthalmologists must strictly review video content when publishing popular science knowledge about myopia prevention and control to ensure its reliability and scientific nature and provide accurate information for patients.

A total of 284 videos were included in this study, among which the videos posted by non-healthcare professionals received more likes, favourites and shares than those posted by healthcare professionals, and the difference was statistically significant. From this, we can speculate that videos posted by non-healthcare professionals are more acceptable, more popular with the general public and more widely disseminated. A cross-sectional study evaluating the quality of videos related to breast cancer on short video-sharing platforms also showed that videos posted by patients received more comments and were more engaging than those posted by medical professionals, 40 and another study showed that healthcare professionals were inferior to other creators in creating short videos. 41 We speculate that this may be because non-healthcare professionals often use language that is more easily accepted by the general public rather than professional terms. Many of them are patients with myopia or their families and are more likely to gain sympathy from the general public. Their video formats tend to be more elaborate than those of healthcare professionals. In addition, previous studies have shown that the comprehensiveness of video content is related to the number of video comments and shares. 42Interestingly, our findings revealed that shorter videos tended to receive higher engagement metrics, such as likes and shares, despite often scoring lower in educational quality. A study suggested that brief content formats are more likely to retain viewer attention. 43 Similarly, Ming et al found that TikTok videos >60 s tend to receive fewer likes per day, though they score higher in content quality.44 However, the brevity of such content may compromise the accuracy and depth of information delivered, particularly in health-related communication. This trade-off highlights a critical challenge in digital health education: balancing audience engagement with evidence-based quality. Future interventions may explore optimal video lengths that maximise both viewer retention and educational value.

Although the label, sound and effect of a video have no significant effect on the number of its views, this gives us enlightenment that when releasing popular science videos related to myopia prevention and control, we should not only pay attention to the accuracy and completeness of the information, but also consider whether it is easy to be accepted by the general public and adjust the video duration.

However, regarding both GQS and DIS scores, videos posted by healthcare professionals demonstrated significantly higher quality. Moreover, recommendations from ophthalmologists and optometrists are typically grounded in high-level evidence, including randomised controlled trials and clinical guidelines (eg, LAMP (Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression), and BLINK studies(Bifocal Lenses In Nearsighted Kids studies)). In contrast, advice from other healthcare professionals (eg, nutritionists and general practitioners) often relies on lower-quality evidence and anecdotal reports or lacks empirical validation. These differences may explain why the overall quality of videos by healthcare professionals was higher than that of non-professionals. Some previous studies have also shown that healthcare professionals can release more reliable and complete videos with more accurate information on short video-sharing platforms. 42We further analysed and compared the videos posted by healthcare professionals. Although the DIS scores and GQS of videos posted by ophthalmologists were higher than those of non-ophthalmologists, the number of likes, favourites and retweets of videos posted by non-ophthalmologists was higher than that of ophthalmologists. This engagement difference may be attributed to factors, such as more relatable language, storytelling nature or the use of platform-optimised formats, rather than the scientific rigour of the content. Another possible explanation for the engagement difference may be their communication style or perceived relatability. Notably, many of the preventive measures promoted in these videos—particularly by non-specialist healthcare professionals—were supported by evidence of moderate or lower quality. Thus, although these videos may resonate more with the general public, their educational reliability remains limited.

At present, some studies have evaluated the quality of myopic videos on short video-sharing platforms. Shuaiming et al found that the most popular videos on the platform were not from healthcare professionals, 45and these videos have low quality. 44 Similar studies on other topics have also shown that many videos on short video-sharing platforms have unsatisfactory content and quality. 46 47 In this study, we evaluated the content, quality and reliability of popular science videos on myopia prevention and control on TikTok, BiliBili and Kwai. The quality of the videos collected was generally not high, and few videos comprehensively introduced the six aspects of myopia prevention and control, namely, definition, symptoms, risk factors, specific measures for prevention and control and results of treatment of myopia, and possible adverse reactions caused by myopia treatment make videos less potentially helpful to patients, which may be because these videos are not regulated before publication.28

Among the five methods commonly mentioned by ophthalmologists and non-ophthalmologists, the difference was statistically significant: wearing suitable lenses, using low-concentration atropine drops and vision training, indicating that different categories of people have preferences in recommending myopia prevention and control, and ophthalmologists are more inclined to recommend patients wear suitable lenses and useatropine drops. Non-healthcare professionals were more likely to recommend vision training that was easy to implement. In general, the advice provided by ophthalmologists was more clinically relevant. Wearing suitable lenses is still the most commonly used and effective measure for myopia control.48 Many studies have shown a significant association between increased time spent outdoors and decreased incidence of myopia. 949,51 Low-concentration atropine drops have been proven to be effective and relatively safe for controlling myopia progression. 52 53 However, most of the suggestions commonly mentioned by non-healthcare professionals are based on practical life, but may not have scientific evidence. For example, vision training (mainly referring to eye exercises and other vision training exercises), which is often mentioned by non-healthcare professionals, may not help in slowing down myopia progression.54 Long hours of near work, such as writing homework for >2 hours a day, are a high risk factor for myopia. Improving eye habits can help slow down the progression of myopia.55

Short videos can provide quick and easy to information and make complex health information easier to understand and remember.56 However, the proliferation of scientifically inaccurate or misleading content on popular platforms is concerning, particularly when such videos attract substantial public engagement. These inaccuracies may mislead patients and undermine evidence-based care, highlighting the need for improved content quality and stricter moderation. Our findings support the importance of promoting verified sources and involving science communication professionals in public health strategies. Moreover, the strength of the supporting scientific evidence of myopia prevention strategies featured in these videos varies considerably. Although interventions such as outdoor activity and low-dose atropine are supported by high-level evidence, other approaches—such as vision training or dietary modification—are based on limited or inconclusive findings. This variability may contribute to public confusion and pose a methodological limitation when evaluating the quality and accuracy of user-generated content.

This study also highlights the broader challenge of science communication in the digital era. Although healthcare professionals produced more accurate and evidence-based content, their videos often received lower engagement than those of non-healthcare professional creators. This discrepancy underscores several fundamental science communication barriers. Terminology accessibility: specialised medical lexicon (eg, cycloplegic refraction and defocus-incorporated multiple-segment lenses) impedes public comprehension. Evidence-level recognition deficit: audiences demonstrate limited capacity to differentiate evidence-based interventions (eg, low-concentration atropine drops (level I evidence)) from unsubstantiated approaches (eg, vision training (level III evidence)). To bridge this scientist–society gap, we advocate for specialised science communication initiatives that integrate cross-disciplinary teams (clinicians+communication specialists) translating technical jargon into visually engaging, culturally relatable narratives (eg, animations explaining myopia progression and interactive elements (question and answer livestreams and myth-debunking series) fostering direct engagement between experts and communities and platform-level prioritisation of certified medical content. These strategies can help simplify complex scientific concepts, foster trust and improve the accessibility of health information across diverse audiences.

This study has limitations. First, this study only collected Chinese videos, so the results may not apply to short video-sharing platforms in other languages. Second, videos posted on TikTok, BiliBili and Kwai are constantly uploaded and spread, whereas this study only evaluated and analysed videos posted within a specific period. Third, although the video quality was scored independently by three experienced ophthalmologists, we still could not avoid potential systematic errors. Fourth, as our classification of lens recommendations was based on general video content, we did not further distinguish between standard corrective lenses and those specifically designed for myopia control. Future studies may benefit from more granular categorisation. Finally, owing to the limitation of short video-sharing platforms, we did not obtain the specific views of these videos. However, based on the number of likes, shares and favourites of these videos, we can still infer that these videos have a wide audience.

Conclusion

This study analysed 284 myopia prevention and control videos from TikTok, BiliBili and Kwai. Overall, video quality was unsatisfactory and correlated with the source. Healthcare professionals generally produced higher quality and more comprehensive content than non-healthcare professionals. Ophthalmologists provide detailed information on myopia’s definition, symptoms and risk factors, whereas non-healthcare professionals focus on prevention measures, treatment outcomes and potential adverse effects. Healthcare professionals often recommended appropriate lenses and low-concentration atropine drops, whereas non-healthcare professionals favoured vision training. In the future, we should pay more attention to the concerns of viewers when creating short popular science videos on myopia prevention and control to improve the quality of myopia prevention and control videos on short video-sharing platforms.

Supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the Scientific Research Program of Shanghai Health Commission (No. 202340282).

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2025-102818).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Jinshan Hospital of Fudan University. (JIEC2023-S92) Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: Not applicable.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Baird PN, Saw S-M, Lanca C, et al. Myopia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:99. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan IG, Ohno-Matsui K, Saw S-M. Myopia. Lancet. 2012;379:1739–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah R, Vlasak N, Evans BJW. High myopia: Reviews of myopia control strategies and myopia complications. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt . 2024;44:1248–60. doi: 10.1111/opo.13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrenson JG, Shah R, Huntjens B, et al. Interventions for myopia control in children: a living systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;2:CD014758. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014758.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang XJ, Zhang Y, Yip BHK, et al. Five-Year Clinical Trial of the Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) Study: Phase 4 Report. Ophthalmology. 2024;131:1011–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yam JC, Jiang Y, Tang SM, et al. Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) Study: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial of 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01% Atropine Eye Drops in Myopia Control. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng L, Pang Y. Effect of Outdoor Activities in Myopia Control: Meta-analysis of Clinical Studies. Optom Vis Sci . 2019;96:276–82. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong S, Sankaridurg P, Naduvilath T, et al. Time spent in outdoor activities in relation to myopia prevention and control: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Ophthalmol . 2017;95:551–66. doi: 10.1111/aos.13403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kido A, Miyake M, Watanabe N. Interventions to increase time spent outdoors for preventing incidence and progression of myopia in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;6:CD013549. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013549.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Lu Y, Huang D, et al. The Efficacy of Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments Lenses in Slowing Myopia Progression: Results from Diverse Clinical Circumstances. Ophthalmology. 2023;130:542–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walline JJ, Walker MK, Mutti DO, et al. Effect of High Add Power, Medium Add Power, or Single-Vision Contact Lenses on Myopia Progression in Children: The BLINK Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA . 2020;324:571–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yli-Uotila T, Rantanen A, Suominen T. Motives of cancer patients for using the Internet to seek social support. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013;22:261–71. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.How many smartphones are in the world. https://www.bankmycell.com/blog/how-many-phones-are-in-the-world n.d. Available.

- 14.Yi S, Guo Y, Lin Z, et al. Is information evaluated subjectively? Social media has changed the way users search for medical information. Digit Health . 2024;10:20552076241259039. doi: 10.1177/20552076241259039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.QuestMobile2025 spring report on china’s mobile internet. https://wwwquestmobilecomcn/research/report/1919961024158601218 n.d. Available.

- 16.Jiang S, Zhou Y, Qiu J, et al. Search engines and short video apps as sources of information on acute pancreatitis in China: quality assessment and content assessment. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1578076. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1578076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu R, Ren Y, Li X, et al. The quality and reliability of short videos about premature ovarian failure on Bilibili and TikTok: Cross-sectional study. Digit Health. 2025;11:20552076251351077. doi: 10.1177/20552076251351077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei Y, Liao F, Li X, et al. Quality and reliability evaluation of pancreatic cancer-related video content on social short video platforms: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health . 2025;25:1919. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-23130-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He W, Tang D, Jin Y, et al. Quality of cerebral palsy videos on Chinese social media platforms. Sci Rep . 15:13323. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-84845-8. n.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai Y, He Z, Liu Y, et al. The quality and reliability of TikTok videos on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a propensity score matching analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1231240. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1231240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinese Association of Integration Medicine; China Association of Chinese Medicine; Chinese Medical Association Clinical practice guideline of integrative Chinese and western medicine for myopia in children. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi Jan. 2024;60:13–34. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112142-20231025-00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gifford KL, Richdale K, Kang P, et al. IMI - Clinical Management Guidelines Report. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:M184–203. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harewood J, Contreras M, Huang K, et al. Access to Myopia Care in the United States-A Narrative Review. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2025;66:5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.66.7.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Z, Chen Y, Tan Z, et al. Interventions recommended for myopia prevention and control among children and adolescents in China: a systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023;107:160–6. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-319306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Mueller A, Morgan I, et al. Best practice in myopia control: insights and innovations for myopia prevention and control – a round table discussion. Br J Ophthalmol. 2024;108:913–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo-2023-325112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S-H, Tseng B-Y, Wang J-H, et al. Efficacy of Myopia Prevention in At-Risk Children: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. JCM. 2025;14:1665. doi: 10.3390/jcm14051665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engin O, Kızılırmak Karataş AS, Taşpınar B, et al. Evaluation of YouTube videos as a source of information on facial paralysis exercises. NeuroRehabilitation. 2024 doi: 10.3233/NRE-240027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai Y, Liao F, He Z, et al. The status quo of short videos as a health information source of Helicobacter pylori: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1344212. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1344212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holden BA, et al. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1036–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang W, Tan T, Lin J, et al. Developmental characteristics and control effects of myopia and eye diseases in children and adolescents: a school-based retrospective cohort study in Southwest China. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e083051. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-083051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.So C, Lian J, McGhee SM, et al. Lifetime cost-effectiveness of myopia control intervention for the children population. J Glob Health. 2024;14:04183. doi: 10.7189/jogh.14.04183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Division of B . National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2024 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. National Academies Press (US); 2024. The national academies collection: reports funded by national institutes of health. myopia: causes, prevention, and treatment of an increasingly common disease. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The 54th statistical report on internet on china’s internet development. https://www.cnnic.cn/n4/2024/0829/c88-11065.html n.d. Available.

- 34.He Z, Wang Z, Song Y, et al. The Reliability and Quality of Short Videos as a Source of Dietary Guidance for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Cross-sectional Study. J Med Internet Res . 2023;25:e41518. doi: 10.2196/41518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poza-Méndez M, Fernández-Gutiérrez M, Marín-Paz AJ, et al. TikTok as a teaching and learning method for nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2024;141:106328. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petkovic J, Duench S, Trawin J, et al. Behavioural interventions delivered through interactive social media for health behaviour change, health outcomes, and health equity in the adult population. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5:CD012932. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012932.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng F, Zhang W, Wang M, et al. Douyin and Bilibili as sources of information on lung cancer in China through assessment and analysis of the content and quality. Sci Rep . 14:20604. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70640-y. n.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pennycook G, McPhetres J, Zhang Y, et al. Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental Evidence for a Scalable Accuracy-Nudge Intervention. Psychol Sci. 2020;31:770–80. doi: 10.1177/0956797620939054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X, Kong Q, Song Y, et al. TikTok and Bilibili as health information sources on gastroesophageal reflux disease: an assessment of content and its quality. Dis Esophagus. 2024;37:doae081. doi: 10.1093/dote/doae081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qu Y, Lian J, Pan B, et al. Assessing the quality of breast cancer-related videos on TikTok: A cross-sectional study. Digit Health. 2024;10:20552076241277688. doi: 10.1177/20552076241277688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fritsche M, King T, Hollins L. Skin of Color in Dermatology: Analysis of Content and Engagement on TikTok. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:718–22. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gong X, Dong B, Li L, et al. TikTok video as a health education source of information on heart failure in China: a content analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1315393. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1315393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Violot C, Elmas T, Bilogrevic I, et al. Shorts vs. regular videos on youtube: a comparative analysis of user engagement and content creation trends. Arixv. 2024 doi: 10.1145/3614419.3644023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ming S, Han J, Yao X, et al. Myopia information on TikTok: analysis factors that impact video quality and audience engagement. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1194. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18687-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ming S, Han J, Li M, et al. TikTok and adolescent vision health: Content and information quality assessment of the top short videos related to myopia. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1068582. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1068582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Du RC, Zhang Y, Wang MH, et al. TikTok and Bilibili as sources of information on Helicobacter pylori in China: A content and quality analysis. Helicobacter . 2023;28:e13007. doi: 10.1111/hel.13007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan W, Liu Y, Shi Z, et al. Information quality of videos related to Helicobacter pylori infection on TikTok: Cross-sectional study. Helicobacter . 2024;29:e13029. doi: 10.1111/hel.13029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao J, Huang Y, Li X, et al. Spectacle Lenses With Aspherical Lenslets for Myopia Control vs Single-Vision Spectacle Lenses: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol . 2022;140:472–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.0401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Ip J, et al. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology . 2008;115:1279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dirani M, Tong L, Gazzard G, et al. Outdoor activity and myopia in Singapore teenage children. Br J Ophthalmol . 2009;93:997–1000. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.150979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin Z, Vasudevan B, Jhanji V, et al. Near work, outdoor activity, and their association with refractive error. Optom Vis Sci . 2014;91:376–82. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bullimore MA, Berntsen DA. Low-Dose Atropine for Myopia Control: Considering All the Data. JAMA Ophthalmol . 2018;136:303. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.6638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Polling J-R, Klaver CCW. Challenges in Assessing Dose-Dependent Atropine for Myopia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024;142:884–5. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2024.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin Z, Xiao F, Cheng W. Eye exercises for myopia prevention and control: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Eye (Lond) 2024;38:473–80. doi: 10.1038/s41433-023-02739-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Li S, He S, et al. Regional disparities in the prevalence and correlated factors of myopia in children and adolescents in Gansu. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024;11:1375080. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1375080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Z, Chen Y, Lin Y, et al. YouTube/ Bilibili/ TikTok videos as sources of medical information on laryngeal carcinoma: cross-sectional content analysis study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1594. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-19077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]