Abstract

Purpose

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder often associated with obesity and insulin resistance (IR), though the role of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) in obesity-induced IR in PCOS remains unclear. This study explores the relationship between TXNIP levels and obesity-associated IR in women with PCOS.

Methods

A case–control study was conducted from January 2019 to December 2020, including 161 women with PCOS and 107 healthy controls. PCOS patients were categorized into insulin-resistant (IR) and non-IR subgroups, further divided by BMI into obese, overweight, and normal weight groups. The metabolic parameters such as cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting blood glucose, homocysteine, and serum TXNIP levels were measured. Logistic regression assessed the relationship between TXNIP expression and metabolic dysfunction.

Results

TXNIP levels were significantly higher in the PCOS group compared to controls (67% increase), with a further 56% increase in the IR subgroup. The TXNIP levels were elevated in the obese group compared to overweight and normal weight groups (P < 0.05). TXNIP expression was negatively correlated with obesity (R = − 0.116, P = 0.007) and HDL cholesterol (R = − 0.196, P = 0.001), but positively associated with triglycerides (R = 0.181, P = 0.003) and homocysteine (R = 0.130, P = 0.034). After adjusting for confounders, TXNIP remained significantly associated with IR (P < 0.05). TXNIP demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance in distinguishing IR from non-IR PCOS patients, with an AUC of 0.89 (95% CI 0.84–0.94; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

TXNIP is significantly correlated with IR in women with PCOS, highlighting its potential as a biomarker for metabolic abnormalities. Further research is needed to fully understand its role in obesity-induced IR in PCOS.

Keywords: Thioredoxin-interacting protein, Polycystic ovary syndrome, Insulin resistance, Obesity, Metabolic

What does this study add to the clinical work

| This study identifies thioredoxin-ineracting (TXNIP) as a potential biomarker for obesity-induced insulin resistance in PCOS patients, offering a novel target for early diagnosis and personalized metabolic interventions in clinical practice. |

Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a complex and prevalent metabolic and endocrine disorder that affects a substantial number of women, with estimates of prevalence ranging between 6 and 22%, depending on the diagnostic criteria employed [1, 2]. PCOS is closely linked to a range of metabolic disturbances, such as insulin resistance (IR), dyslipidemia, and an elevated risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [3, 4]. The onset of PCOS typically begins in adolescence, often with symptoms that fluctuate in intensity over time. While lifestyle factors, particularly diet and weight gain, play a significant role in the development and progression of the disorder, the underlying mechanisms driving PCOS remain incompletely understood, underscoring the need for further research into this condition [5].

A critical contributor to the metabolic dysfunction in PCOS is obesity-induced IR. Women with PCOS often experience increased visceral fat, which triggers low-grade systemic inflammation and impairs insulin signaling [6]. This disruption in insulin action is partly driven by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 from excess adipose tissue. These cytokines interfere with insulin receptor function, reducing glucose uptake in muscle and liver cells. Additionally, elevated levels of free fatty acids amplify oxidative stress (OS) and impair mitochondrial function, further exacerbating IR [7]. In response to this metabolic disturbance, the pancreas produces more insulin to compensate for the reduced effectiveness and this increase in insulin stimulates the ovaries to produce excess androgens. This cascade of events results in hormonal imbalances that disrupt the menstrual cycle and lead to anovulation, making fertility a challenge for many women with PCOS [8]. Research supports that lifestyle interventions such as weight management through dietary changes and exercise can help improve insulin sensitivity, restore hormonal balance, and mitigate the severity of these symptoms, emphasizing the importance of metabolic health in managing PCOS.

The intricate relationship between metabolic dysfunction and inflammation in PCOS contributes significantly to the worsening of symptoms [9]. The studies have shown that pro-inflammatory markers like IL-18 and the adipokine metrnl are elevated in women with PCOS, correlating with both fat accumulation and impaired glucose metabolism, further complicating the metabolic landscape of the condition [10]. Central obesity, often a feature of PCOS, further amplifies these issues, promoting lipid imbalances, and significantly increasing the risk for cardiovascular complications [11]. Even women with a normal body mass index (BMI) may experience central adiposity and IR, especially those who are overweight or obese. This underscores the need for therapeutic approaches that address both the metabolic and inflammatory components of PCOS, aiming to reduce long-term health risks [12, 13].

Recently, thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) has been identified as a key player in regulating OS, inflammation, and metabolism by inhibiting the activity of thioredoxin and maintaining cellular redox balance [14, 15]. This inhibition increases OS, which disrupts critical metabolic processes, including insulin secretion, glucose production, and glucose uptake by peripheral tissues like muscle and adipose cells [15, 16]. In women with PCOS and IR, elevated TXNIP levels have been linked to excess visceral fat and sustained hyperinsulinemia [17]. These factors work together to worsen OS, impair insulin signaling, and disrupt glucose metabolism by reducing the activity of key glucose transporters like glucose transporter type 4 [18]. Additionally, free fatty acids and proinflammatory cytokines further stimulate TXNIP expression, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [14, 19]. These pathological changes exacerbate IR and lead to β-cell dysfunction, creating a vicious cycle of metabolic decline that is challenging to reverse [20, 21]. TXNIP plays a critical role in ovarian function, thereby linking it to the pathophysiology of PCOS [17, 22]. The hormonal dysregulation characteristic of PCOS disrupts the normal progression of ovarian follicular development, leading to the manifestation of menstrual irregularities and anovulation. These disruptions, in turn, have significant implications for fertility, as the failure to ovulate impedes the release of mature oocytes necessary for conception. Consequently, TXNIP’s involvement in these processes underscores its potential as a key mediator in the ovarian dysfunction observed in PCOS [17, 23]. Given its involvement in both metabolic and reproductive dysfunction, TXNIP has emerged as a potential therapeutic target [22]. The interventions designed to reduce TXNIP expression, whether through antioxidants, pharmacological agents, or lifestyle changes, may help to improve insulin sensitivity and restore hormonal balance. The widely used PCOS treatment metformin has been shown to reduce TXNIP levels, suggesting that targeting TXNIP could offer an effective strategy for managing both the metabolic and reproductive aspects of the disorder [22, 24].

Although significant strides have been made in understanding the role of TXNIP in metabolic dysfunction, its precise involvement in obesity-induced IR in PCOS remains poorly defined. This study aims to further explore the relationship between TXNIP, obesity, and IR in women with PCOS. Comprehensive, large-scale case–control studies are necessary to unravel how TXNIP contributes to the metabolic disturbances seen in PCOS. Further research could shed light on the underlying mechanisms of PCOS and support the discovery of novel biomarkers. TXNIP emerges as a promising candidate for identifying metabolic dysfunction in PCOS, meriting deeper mechanistic and longitudinal exploration.

Methods

Study design and participants

This analytical case–control study was conducted between January 2019 and December 2020 at the Department of Reproductive Medicine, Hangzhou Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China. Hangzhou Women’s Hospital is a leading institution in Zhejiang Province, renowned for its specialization in women’s health, and serves as a tertiary care center for reproductive medicine. A total of 161 women diagnosed with PCOS and 107 healthy, age-matched women as controls were enrolled in the study. The PCOS group met the 2003 ESHRE/ASRM Rotterdam criteria [16, 25], which require at least two of the following three conditions: oligo- or anovulation, clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries observed via ultrasound. The control group comprised women with regular menstrual cycles and no clinical evidence of hyperandrogenism or metabolic disorders. The inclusion criteria for the study were: women aged between 18 and 40 years with a diagnosis of PCOS (for the PCOS group) or healthy women with regular menstrual cycles (for the control group). The women were excluded if they had used hormonal contraceptives or other medications that might affect hormone levels or metabolic parameters within the last 3 months. Additional exclusion criteria included a history of thyroid or adrenal disorders, significant liver or kidney disease, cancer, or T2DM. These criteria were established to ensure that any confounding factors related to hormone and metabolic disorders were minimized.

Patients’ characteristics

The diagnosis of PCOS in this study was made using the 2003 ESHRE/ASRM Rotterdam Conference criteria, which include irregular menstrual cycles, clinical or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries confirmed via ultrasound. The control group consisted of women with regular menstrual cycles, no clinical or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism, and normal ovarian morphology as confirmed by ultrasound. The demographic data, including age, menstrual history, family medical history, BMI, and lifestyle factors, were collected through structured questionnaires. The participants were asked about their reproductive history, including the onset of menarche, menstrual cycle regularity, and any fertility-related concerns. The lifestyle factors, such as physical activity and dietary habits, were also recorded, along with a detailed medical history, including conditions like diabetes or hypertension. Anthropometric measurements, including body weight, height, and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), were taken using standard clinical methods. BMI was calculated based on weight and height. WHR was determined by measuring waist circumference at the narrowest point and hip circumference at the widest point. The clinical characteristics were assessed by measuring hormones such as testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), which is a marker of ovarian reserve and is typically elevated in women with PCOS.

Clinical assessment

Fasting venous blood samples (10 mL per participant) were collected from both the PCOS and control groups following an overnight fast of at least 12 h. The samples were processed by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. Serum was subsequently stored at – 80 °C for further analysis. Enzyme chemiluminescent immunoassays were used to quantify various biochemical markers, including total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides (TG), homocysteine (HCY), C-reactive protein (CRP), fasting insulin (Fins), and fasting blood glucose (FBG). These assays were performed using the Beckman-Coulter AU5800 autoanalyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, California, USA), known for its precision and reliability in handling large volumes of samples. IR was evaluated using the HOMA-IR method, with a value of > 2.6 indicating the presence of IR. Additionally, the Free Androgen Index (FAI) was calculated to assess androgen excess in women with PCOS.

Diagnostic criteria for IR and obesity

IR in this study was assessed using the Homeostasis Model Assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), with a cutoff value of > 2.6 indicating IR [26], using the following formula:

The Free Androgen Index (FAI) was calculated to assess androgen excess in women with PCOS using the formula:

For obesity classification, BMI was used: overweight was defined as 24 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 28 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 [27].

ELISA measurements

Serum levels of TXNIP (Catalog No. JL19662, Jianglai Biological, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China), a marker of OS and insulin sensitivity, and AMH (Catalog No. JL47538, Jianglai Biological, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China), a marker of ovarian reserve, were quantified using double-antibody sandwich ELISA kits. These kits are recognized for their high sensitivity and specificity, with detection limits of 0.05 ng/mL for TXNIP and 0.10 ng/mL for AMH. All assays were performed using a SpectraMax Plus 384 ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, USA, MD) and a Stat-Fax 2600 Washer (Awareness Technology, USA), ensuring accurate and reliable readings. The sample preparation was conducted using a TDZ4-WS low-speed automatic balance centrifuge (Xiangyi, Hunan, China). All procedures adhered to the manufacturer’s protocols to guarantee consistent and dependable results.

Statistical analysis

Data were recorded in Excel and analyzed with SPSS software (Version 21, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD) or medians (range), depending on data distribution. For non-normally distributed data, comparisons across groups were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. TXNIP’s diagnostic significance was validated through robust receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, which demonstrated strong discriminative power in distinguishing between the different study groups. All analyses were repeated at least three times. Significant differences identified by the Kruskal–Wallis test were further analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test, with p-values adjusted via the Bonferroni correction. To assess the relationship between TXNIP and other metabolic parameters, logistic regression models were applied. For normally distributed data, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used, while Spearman’s rank correlation was employed for non-normally distributed data. A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Graphs were generated using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Demographic and clinical findings

In this study, we included 161 women diagnosed with PCOS and 107 healthy, age-matched control participants, selected based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant age differences between the two groups (24.79 ± 4.86 Vs. 24.29 ± 4.83; P = 0.41). However, women with PCOS had a significantly higher BMI, showing a 1.2-fold increase compared to the control group (P < 0.001), which may contribute to the metabolic issues associated with the condition. We observed significantly higher levels of AMH, a key marker for ovarian reserve, in the PCOS group (7.85 ± 3.24 ng/mL) compared to the control group (3.63 ± 1.96 ng/mL; P < 0.001). Additionally, CRP, an inflammatory marker, was also significantly elevated in the PCOS group (2.24 ± 2.73 mg/L) compared to the control group (1.35 ± 1.39 mg/L; P = 0.001), indicating a heightened inflammatory state in women with PCOS.

Table 1.

General characteristics of PCOS and control groups

| Parameter | PCOS (n = 161) | Control (n = 107) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.79 ± 4.86 | 24.29 ± 4.83 | 0.410 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.87 ± 4.06 | 19.91 ± 1.76 | < 0.001 |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 7.85 ± 3.24 | 3.63 ± 1.96 | < 0.001 |

| HCY (μmol/L) | 11.73 ± 3.71 | 6.90 ± 2.09 | < 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.23 ± 1.89 | 1.53 ± 0.72 | < 0.001 |

| Fasting Insulin (μIU/mL) | 9.91 ± 7.52 | 7.51 ± 3.36 | < 0.001 |

| Fasting Blood Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.91 ± 0.48 | 4.58 ± 0.35 | < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.24 ± 2.73 | 1.35 ± 1.39 | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.20 ± 0.75 | 0.87 ± 0.46 | < 0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.47 ± 0.37 | 1.73 ± 0.35 | < 0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.66 ± 0.73 | 2.40 ± 0.70 | 0.004 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.75 ± 0.86 | 4.47 ± 0.82 | 0.008 |

| TXNIP (ng/mL) | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | < 0.001 |

Note: P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation

Abbreviation: BMI body mass index, AMH anti-Müllerian hormone, HCY homocysteine, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, FIns fasting insulin, FBG, fasting blood glucose, CRP C-reactive protein, TG triglycerides, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, TC total cholesterol, TXNIP thioredoxin-interacting protein

The HCY levels, a substance linked to cardiovascular risk, were also significantly higher in women with PCOS (11.73 ± 3.71 µmol/L) when compared to the control group (6.90 ± 2.09 µmol/L; P < 0.001). This suggests that women with PCOS may face an increased risk of cardiovascular problems.

IR was notably higher in the PCOS group, as indicated by the HOMA-IR. The average HOMA-IR value for women with PCOS (2.23 ± 1.89) was significantly higher than that of the control group (1.53 ± 0.72, P < 0.001), signaling a higher degree of IR in the PCOS group. The Fins and FBG levels were 1.32-fold and 1.07-fold higher in the PCOS group compared to controls (both P < 0.001). Regarding lipid profiles, TG, LDL, and TC were significantly elevated in the PCOS group, while HDL was significantly lower compared to the control group (P < 0.001). These findings point to a dyslipidemic pattern commonly seen in PCOS. In conclusion, elevated markers of IR, dyslipidemia, inflammation, and OS observed in the PCOS group emphasize the long-term health risks associated with this condition.

Overexpression of TXNIP in IR-induced PCOS

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of TXNIP, a crucial marker for OS, across the study participants and groups. In Fig. 1A, TXNIP levels were significantly higher in the PCOS group (0.32 ± 0.09 ng/mL), reflecting a 1.1-fold increase when compared to the control group (0.29 ± 0.05 ng/mL, P = 0.001). This indicates that women with PCOS experience increased OS. To explore the role of TXNIP in IR among women with PCOS, the participants were separated into two groups: IR-PCOS (n = 41) and non-IR-PCOS (n = 120). This classification allowed us to investigate the association between metabolic parameters and TXNIP levels for IR. In Fig. 1B, TXNIP levels were significantly elevated in the IR group (0.42 ± 0.10 ng/mL) compared to the non-IR group (0.29 ± 0.06 ng/mL; P < 0.001). This finding suggests that TXNIP is strongly associated with IR in women with PCOS. In addition to TXNIP, other key metabolic parameters exhibited notable differences between the two groups (Table 2). The mean BMI was significantly higher in the IR group (27.12 ± 3.39) than in the non-IR group (21.41 ± 3.16), with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). Additionally, CRP and TG levels were higher in the IR group in comparison with the non-IR group, with a significant difference observed (P < 0.001). HDL levels were lower in the IR group (1.24 ± 0.29) compared to the non-IR group (1.54 ± 0.36) (P < 0.001), while LDL levels were slightly higher in the IR group (2.93 ± 0.71) than in the non-IR group (2.57 ± 0.73), with a statistically significant difference (P = 0.007). Interestingly, there were no significant differences in the levels of AMH and HCY between the two groups (P > 0.05). These findings underline that TXNIP emerges as a potential biomarker linked to IR and may contribute to the development of IR in women with PCOS (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

TXNIP expression in PCOS and association with insulin resistance and obesity. A TXNIP expression is elevated in PCOS compared to healthy controls. TXNIP expression (ng/mL) was significantly higher in individuals with PCOS compared to healthy controls, suggesting a potential role of TXNIP in PCOS pathophysiology. B This graph shows a TXNIP expression is increased in insulin-resistant (IR) PCOS compared to non-insulin-resistant (non-IR) PCOS. TXNIP levels were significantly higher in IR-PCOS individuals than in non-IR-PCOS individuals, indicating an association between TXNIP and insulin resistance in PCOS. C TXNIP expression differs among PCOS subgroups based on obesity status. TXNIP levels were significantly lower in overweight (OW-PCOS) and obese (OB-PCOS) individuals compared to controls (Ctrl), with p-values of 0.034 and 0.012, respectively. These findings suggest that TXNIP expression may be influenced by BMI in PCOS patients. Each data point represents an individual, and horizontal bars indicate the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined using independent t-tests

Table 2.

TXNIP levels and metabolic parameters in PCOS with non-IR-PCOS and IR-PCOS

| Parameter | IR-PCOS (n = 41) | Non-IR-PCOS (n = 120) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.44 ± 5.04 | 24.91 ± 4.81 | 0.595 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.12 ± 3.39 | 21.41 ± 3.16 | < 0.001 |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 7.24 ± 3.19 | 8.06 ± 3.24 | 0.159 |

| HCY (µmol/L) | 11.62 ± 3.05 | 11.77 ± 3.92 | 0.820 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.32 ± 2.82 | 1.87 ± 2.61 | 0.003 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.60 ± 0.71 | 1.06 ± 0.71 | < 0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.24 ± 0.29 | 1.54 ± 0.36 | < 0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.93 ± 0.71 | 2.57 ± 0.73 | 0.007 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.89 ± 0.78 | 4.71 ± 0.89 | 0.250 |

| TXNIP (ng/mL) | 0.42 ± 0.10 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | < 0.001 |

Note: P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index, AMH Anti-Müllerian hormone, HCY homocysteine, CRP C-reactive protein, TG triglycerides, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, TC total cholesterol, TXNIP thioredoxin-interacting protein, IR-PCOS insulin-resistant PCOS group, Non-IR-PCOS non-insulin-resistant PCOS group

Table 3.

Comparison of TXNIP levels and metabolic parameters across PCOS groups with different BMI and control

| Parameter | Ctrl. (n = 102) | OB-PCOS (n = 21) | OW-PCOS (n = 38) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.62 ± 4.67 | 25.52 ± 4.09 | 24.84 ± 4.71 | 0.739 |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 8.13 ± 3.17 | 7.28 ± 3.23 | 7.44 ± 3.41 | 0.369 |

| HCY (µmol/L) | 11.83 ± 3.75 | 12.04 ± 3.86 | 11.31 ± 3.59 | 0.702 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.60 ± 1.14 | 4.33 ± 3.04 | 2.75 ± 1.73 | < 0.001 |

| Fins (mU/L) | 7.32 ± 4.68 | 18.46 ± 11.53 | 12.13 ± 6.91 | < 0.001 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 4.84 ± 0.39 | 5.16 ± 0.69 | 4.95 ± 0.54 | 0.017 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.86 ± 2.62 | 3.61 ± 2.97 | 2.52 ± 2.67 | 0.020 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.98 ± 0.55 | 1.85 ± 1.04 | 1.43 ± 0.76 | < 0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.60 ± 0.36 | 1.13 ± 0.23 | 1.30 ± 0.26 | < 0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.58 ± 0.72 | 2.91 ± 0.70 | 2.76 ± 0.78 | 0.103 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.74 ± 0.84 | 4.92 ± 0.84 | 4.70 ± 0.94 | 0.628 |

| TXNIP (ng/mL) | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.38 ± 0.11 | 0.33 ± 0.11 | < 0.001 |

Note: P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation

Abbreviations: AMH Anti-Müllerian hormone, HCY Homocysteine, HOMA-IR Homeostatic Model Assessment Index, Fins Fasting insulin, FBG Fasting blood glucose, CRP C-reactive protein, TG Triglycerides, HDL High-density lipoprotein, LDL Low-density lipoprotein, TC Total cholesterol, TXNIP Thioredoxin-interacting protein, OB-PCOS Obese PCOS group, OW-PCOS Overweight PCOS group, CTRL Control group

TXNIP expression in PCOS with different BMI

To explore the relationship between BMI, TXNIP, and metabolic parameters in women with PCOS, the participants were classified based on their BMI into three groups: Obese (n = 21), Overweight (n = 38), and Normal weight (Control) (n = 102). Our results demonstrated significant variations in TXNIP levels and other metabolic markers among these groups, emphasizing the role of obesity in the metabolic dysfunction associated with PCOS (Fig. 1C). The TXNIP levels showed a distinct pattern across the groups: the Obese-PCOS group had the highest levels (0.38 ± 0.11), followed by the overweight-PCOS group (0.33 ± 0.11), and the Control group had the lowest levels (0.30 ± 0.07). When compared to the control group, the obese-PCOS group exhibited a 21% increase in TXNIP levels (P < 0.05; Fig. 1C), while the overweight-PCOS group showed a 10% rise in TXNIP expression. These results suggest a positive correlation between increased body weight and higher TXNIP levels, potentially reflecting heightened OS and IR in individuals with higher BMI. The elevated TXNIP levels in the obese-PCOS group were coupled with various markers of metabolic imbalance. The Obese-PCOS group had notably higher HOMA-IR (4.33 ± 3.04), a 58% increase compared to the Control group (P < 0.05), signifying severe IR. Additionally, Fins levels were elevated by 35% in the PCOSobese-PCOS group (18.46 ± 11.53) compared to the Control group (P < 0.05). CRP levels in the obese-PCOS group were also 56% higher (3.61 ± 2.97) compared to the Control group (P < 0.05), indicating increased systemic inflammation. Further metabolic disturbances were seen in the obese PCOS group. TG levels were 88% higher (1.85 ± 1.04) in this group compared to the Control group (0.98 ± 0.55; P < 0.05), a significant finding linked to IR and metabolic syndrome. HDL cholesterol was 29% lower in the obese-PCOS group (1.13 ± 0.23) than in the control group (1.60 ± 0.36, P < 0.05), signaling an increased cardiovascular risk in this group.

While both the obese-PCOS and overweight-PCOS groups showed higher TXNIP levels compared to the Control group, the overweight-PCOS group demonstrated milder metabolic changes. In this group, HOMA-IR was 21% higher (2.75 ± 1.73) than in the Control group (P < 0.05), and TG levels were 46% higher (1.43 ± 0.76) compared to the Control group (P < 0.05). However, these changes were less pronounced than those observed in the obese-PCOS group, suggesting that while obesity plays a significant role in metabolic dysfunction, overweight individuals experience a more moderate form of metabolic disturbance. There were no significant differences in LDL cholesterol (Obese: 2.91 ± 0.70 vs. Control: 2.58 ± 0.72) or TC (Obese: 4.92 ± 0.84 vs. Control: 4.74 ± 0.84), suggesting that body weight primarily affects TG and HDL cholesterol levels rather than LDL or TC levels. In conclusion, the findings from this study highlight the significant influence of body weight on the metabolic abnormalities observed in PCOS.

TXNIP correlation with metabolic parameters in PCOS patients with obesity-induced insulin resistance

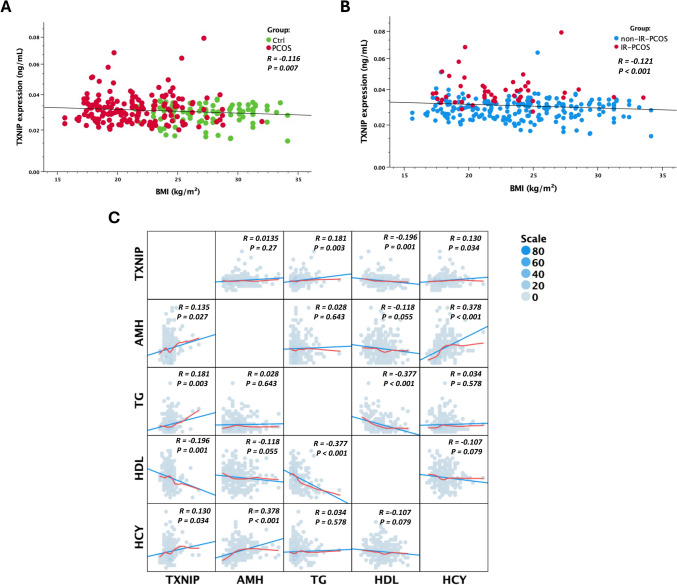

Figure 2 illustrates the correlation between TXNIP expression and key metabolic and hormonal markers in obesity-induced IR in PCOS. In Fig. 2A, TXNIP expression shows a weak but significant negative correlation with BMI in the PCOS group (R = – 0.116, P = 0.007), while the control group exhibits no apparent trend. This relationship is further confirmed in Fig. 2B, where TXNIP expression is negatively associated with BMI in both IR and non-IR-PCOS groups, with a stronger correlation observed in the IR-PCOS subgroup (R = – 0.121, P < 0.001). These findings suggest that TXNIP may be implicated in the metabolic disturbances associated with obesity-driven IR in PCOS. The correlation matrix in Fig. 2C further delineates the metabolic and hormonal interactions of TXNIP. A significant positive correlation is observed between TXNIP and TG (R = 0.181, P = 0.003), implicating TXNIP in lipid metabolism and suggesting a potential role in dyslipidemia. Additionally, TXNIP is strongly correlated with IR (R = 0.535, P < 0.001), reinforcing its involvement in metabolic dysfunction. Conversely, TXNIP exhibits a negative correlation with HDL cholesterol (R = – 0.196, P = 0.001), indicating that higher TXNIP levels may contribute to an unfavorable lipid profile, potentially exacerbating cardiovascular risk. A weak but significant positive correlation with HCY (R = 0.130, P = 0.034) suggests that TXNIP may also influence HCY metabolism, further linking it to cardiovascular risk factors.

Fig. 2.

Collection of the TXNIP expression with metabolic and hormonal parameters in PCOS. A Negative correlation between TXNIP expression and BMI in control (Ctrl) and PCOS groups. TXNIP expression levels (ng/mL) were plotted against BMI (kg/m2) for individuals with PCOS (red) and healthy controls (green). A weak but significant negative correlation was observed, suggesting that TXNIP levels tend to decrease with increasing BMI in PCOS. B Negative correlation between TXNIP expression and BMI in insulin-resistant (IR) and non-insulin-resistant (non-IR) PCOS groups. TXNIP expression (ng/mL) was plotted against BMI (kg/m2) for IR-PCOS (red) and non-IR-PCOS (blue) groups, revealing a significant negative correlation, further supporting an association between TXNIP and metabolic alterations in PCOS. C Correlation matrix depicting relationships between TXNIP and key metabolic and reproductive markers. Scatter plots show pairwise correlations between TXNIP, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and homocysteine (HCY), with Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and p-values indicated. TXNIP was positively correlated with TG and HCY but negatively correlated with HDL. Additionally, TXNIP exhibited a weak but significant positive correlation with AMH, indicating a potential role in ovarian function. Strong negative correlations were observed between HDL and TG, reinforcing the established inverse relationship between these lipid markers. The size and color intensity of the scatter points represent data density

Beyond metabolic parameters, TXNIP is positively correlated with AMH (R = 0.135, P = 0.027), suggesting an association with ovarian reserve and reproductive function. This finding points to a possible link between TXNIP and hormonal regulation in PCOS, a condition characterized by both metabolic and reproductive dysfunction. Notably, TXNIP also shows a significant correlation in PCOS patients (R = 0.186, P = 0.002), a genetic or protein-based marker that itself is positively associated with IR (R = 0.242, P < 0.001) and negatively correlated with BMI (R = – 0.653, P < 0.001), further supporting TXNIP’s potential involvement in the genetic regulation of metabolic pathways. Taken together, these findings highlight the multifaceted role of TXNIP in metabolic and reproductive physiology. Its positive associations with TG, IR, and AMH, coupled with its negative correlation with HDL, suggest a complex regulatory function spanning lipid metabolism, insulin signaling, and ovarian function. These data suggest that TXNIP may serve as a critical molecular link between metabolic dysfunction and reproductive abnormalities in PCOS, warranting further investigation into its mechanistic role in these processes.

TXNIP differentiates insulin-resistant PCOS from non-insulin-resistant PCOS

To assess the diagnostic potential of TXNIP expression, ROC curve analyses were conducted across three clinically relevant comparisons (Fig. 3). In the first analysis, TXNIP levels were evaluated in a cohort of PCOS patients (n = 161) and compared with age- and BMI-matched healthy controls (n = 107). The resulting AUC was 0.57 (95% CI 0.49–0.63; P = 0.065), indicating limited discriminatory power and a lack of statistical significance (Fig. 3A). While a mild trend was noted, TXNIP did not sufficiently differentiate PCOS cases from controls. A notably higher discriminative performance was observed in the comparison between IR-PCOS and non-IR-PCOS (Fig. 3B). This analysis yielded an AUC of 0.89 (95% CI 0.84–0.94; P < 0.001), signifying excellent accuracy and strong statistical support. These results position TXNIP as a promising biomarker for detecting IR within the PCOS population, with potential applications in metabolic profiling and clinical risk stratification. In contrast, TXNIP expression showed minimal diagnostic value in distinguishing obese PCOS individuals from healthy controls. The corresponding AUC was 0.54 (95% CI 0.43–0.64; P = 0.5058), reflecting poor classification ability and no statistical significance (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that obesity-related changes in PCOS do not substantially influence TXNIP expression, limiting its utility in this subgroup.

Fig. 3.

Diagnostic performance of TXNIP expression across different groups. A ROC curve analysis comparing TXNIP expression between PCOS patients and age- and BMI-matched healthy controls. The AUC was 0.5667 indicating a non-significant ability to distinguish between groups. B ROC curve comparing insulin-resistant PCOS (IR-PCOS) versus non-insulin-resistant PCOS (non-IR-PCOS) patients. TXNIP demonstrated strong discriminative power with an AUC of 0.8950 (95% CI 0.8435–0.9465; P < 0.0001). C ROC analysis comparing obese PCOS patients with healthy controls, yielding a low AUC of 0.5366, indicating poor diagnostic utility in this subgroup. The red and black lines represent the reference and observed performance curves, respectively

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between TXNIP and IR in women with PCOS, while also examining associated metabolic dysfunctions. Our findings provide substantial evidence linking elevated TXNIP levels with increased IR, suggesting TXNIP’s potential role as both a biomarker and mediator in the pathophysiology of PCOS. These results are consistent with previous studies, which have reported metabolic and hormonal disturbances such as IR, OS, and dyslipidemia as integral features of PCOS.

Our study confirmed the presence of significant metabolic abnormalities in women with PCOS, with elevated levels of TG and LDL, alongside reduced HDL compared to controls. This dyslipidemic profile, particularly the increase in TG and LDL levels and the decrease in HDL is in agreement with prior research identifying dyslipidemia as a common feature of PCOS, contributing to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [28]. The lipid abnormalities observed here suggest an impaired lipid metabolism that is strongly linked to IR, further supporting the notion that IR plays a central role in the development of various metabolic complications in PCOS, including dyslipidemia and hypertension [4, 29]. Additionally, our study demonstrated significantly higher levels of hyperinsulinemia and IR in the PCOS group, as measured by the HOMA-IR, when compared to controls. These results align with earlier reports indicating that IR is a central feature of PCOS and often predates the onset of other metabolic disorders [30]. This supports the notion that IR not only contributes to glycolipid metabolic disorders but also plays a significant role in the pathophysiology of PCOS, influencing other metabolic dysfunctions such as obesity and dyslipidemia [31].

One of the key findings of this study was the significant elevation of TXNIP levels in women with PCOS compared to controls. TXNIP functions as a negative regulator of the antioxidant enzyme thioredoxin (TRX), a critical component in maintaining cellular redox balance [32, 33]. TRX typically neutralizes reactive oxygen species (ROS), preventing OS and cellular damage [34]. However, when TXNIP binds to TRX, it inhibits its activity, leading to an accumulation of ROS [21]. In tissues such as skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and the liver, excess ROS disrupts normal insulin signaling by promoting the phosphorylation of serine residues on insulin receptor substrates, which inhibits the normal signaling cascade that facilitates glucose uptake [16, 21]. This impairment in insulin signaling is a key feature of IR, a central pathophysiological characteristic of PCOS. Our findings of elevated TXNIP expression align with this mechanism, as higher TXNIP levels can contribute to the accumulation of ROS and, ultimately, to IR [33]. Increased oxidative stress contributes to β-cell dysfunction, promoting apoptosis and impairing insulin secretion. Wu et al. [17] found that many women with PCOS have severe IR and β-cell dysfunction, linking TXNIP to broader metabolic disturbances and a higher risk of T2DM and cardiovascular disease. Our ROC analysis revealed strong statistical significance in distinguishing IR-PCOS from non-IR-PCOS, highlighting TXNIP’s robust ability to identify metabolic dysfunction within the PCOS population. This specificity for IR is further supported by the lack of statistical significance in distinguishing all PCOS patients from healthy controls, suggesting that TXNIP’s diagnostic utility is primarily relevant for assessing metabolic risk in PCOS, rather than serving as a general PCOS biomarker. The clear distinction between IR-PCOS and non-IR-PCOS highlights TXNIP’s potential as a clinically valuable biomarker for identifying individuals at increased metabolic risk.

Recent studies have increasingly highlighted the involvement of TXNIP in the metabolic disturbances observed in obesity and PCOS [17, 35, 36]. Wu et al. (2013) found that women with PCOS had elevated TXNIP levels, reduced insulin sensitivity (M value), and impaired β-cell function (disposition index) [17]. TXNIP was positively correlated with BMI, WHR, and insulin levels, and negatively with insulin sensitivity. The logistic regression analyses confirmed TXNIP’s association with insulin sensitivity, even after adjusting for other factors. However, no link was found between TXNIP and β-cell dysfunction. These findings suggest that TXNIP may play a role in IR in PCOS, but its impact on β-cell dysfunction requires further investigation. Elevated TXNIP expression has been shown to trigger inflammatory responses via the NLRP3 inflammasome, which disrupts insulin signaling pathways. Specifically, TXNIP-induced inflammation enhances the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) at inhibitory sites, impairing glucose uptake and contributing to IR, particularly in obesity. Li et al. also highlighted the role of TXNIP in AD, where it was upregulated in AD brains and co-localized with interleukin-1β (IL-1β), amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) [35], suggesting a link between TXNIP and inflammation in AD pathology. Further studies in animal models, including PCOS mice, showed that increased TXNIP levels exacerbate oxidative stress, leading to β-cell apoptosis and impaired insulin secretion. However, pharmacologic inhibition of TXNIP activity improved insulin release and glucose tolerance, suggesting that targeting TXNIP may help preserve β-cell function and offer therapeutic potential for both AD and metabolic disorders [35]. Additionally, Oslowski et al. demonstrated that TXNIP is upregulated in response to ER stress, leading to β-cell apoptosis through the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [36]. In a PCOS mouse model, the high TXNIP levels were associated with enhanced oxidative stress, resulting in β-cell apoptosis and impaired insulin secretion. However, pharmacological suppression of TXNIP activity improved insulin release and glucose tolerance in this model, suggesting that TXNIP inhibition may protect β-cell function under metabolic stress [36]. Collectively, these findings highlight TXNIP as a key mediator linking inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance in PCOS, suggesting its potential as a diagnostic biomarker to improve metabolic risk stratification, particularly in obese patients.

In another preclinical study, Chutkow et al. investigated the role of TXNIP in T2DM and IR using TXNIP knockout (TXNIP −/−) mice [37]. The results showed that TXNIP−/− mice gained significantly more adipose mass than controls due to increased calorie consumption and adipogenesis. Despite the increase in fat mass, TXNIP−/− mice were markedly more insulin-sensitive than control mice, with enhanced glucose transport observed in both adipose and skeletal muscle. The study also found that TXNIP deletion augmented adipogenesis and improved insulin sensitivity, indicating that TXNIP is a novel regulator of both adipogenesis and IR. Further analysis revealed that TXNIP regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) expression and activity, linking TXNIP’s role to adipogenesis and metabolic regulation [37]. Together, these findings underscore TXNIP’s central role in linking inflammation, oxidative stress, and IR in PCOS, with TXNIP inhibition as a promising molecular target for future diagnostic biomarkers aimed at improving metabolic outcomes in PCOS patients, particularly those affected by obesity.

Further analysis revealed that TXNIP levels were significantly higher in the IR subgroup of PCOS patients, reinforcing the relationship between TXNIP and IR [17, 38]. In this subgroup, elevated TXNIP was associated with higher insulin and glucose levels, as well as increased HOMA-IR scores, indicating more severe IR. These findings suggest that TXNIP plays a critical role in exacerbating metabolic dysfunction in PCOS. We hypothesize that TXNIP plays a role in the pathogenesis of obesity in PCOS patients. TXNIP is expressed in adipose tissue, as reported by Dobosz et al. [39], who identified its epigenetic regulation in tissues involved in obesity-related T2D development, including the liver and adipose tissue. Koenen et al. [40] found that glucose-induced TXNIP activation drives intracellular IL-1β precursor accumulation and IL-1β mRNA expression in adipose tissue, promoting IR. The divergence in TXNIP’s role between adipocytes and β-cells may explain differing effects, as shown by Lei et al. [41], who used a high-fat diet in TXNIP knockout mice. Their study revealed that TXNIP deficiency improved insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and β-cell proliferation, suggesting an anti-diabetogenic effect. TXNIP deficiency also activated key signaling pathways, including p-PI3 K, p-AKT, p-mTOR, and p-GSK3β, indicating that TXNIP inhibits β-cell proliferation via the PI3 K/AKT pathway. Zhang et al. [42] linked TXNIP gene methylation to obesity and hypertriglyceridemia, revealing its connection to an increased T2D risk in the Chinese population. While these studies highlight the relationship between TXNIP and metabolic diseases, they do not clarify the specific action pathways by which TXNIP affects obesity.

Moreover, the multivariate analysis identified TXNIP as an independent risk factor for IR in PCOS, suggesting that elevated TXNIP levels could serve as a potential biomarker for IR in this condition [43, 44]. The strong link between TXNIP and IR, independent of age, BMI, and lipid profiles, emphasizes its role in metabolic dysfunction in PCOS, consistent with studies showing TXNIP upregulation in response to IR across tissues [45]. The molecular mechanisms likely involve TXNIP-induced OS, which impairs insulin receptor activity and disrupts glucose metabolism. TXNIP has been shown to exacerbate IR in obesity and T2DM by inducing β-cell dysfunction and promoting inflammatory pathways in adipose tissue [46]. In PCOS, where insulin resistance is prevalent, TXNIP’s involvement in oxidative stress and related molecular pathways may represent a key link to metabolic disturbances, suggesting its potential as a diagnostic biomarker for identifying patients at risk of metabolic complications [17]. Our exploration of the relationship between TXNIP and obesity in PCOS patients revealed that while TXNIP levels were higher in obese women with PCOS compared to those who were overweight or of normal weight, TXNIP was not found to be an independent risk factor for obesity [11]. This suggests that while TXNIP may be elevated in obese individuals, it is not directly responsible for obesity in PCOS. Previous research has shown that TXNIP is expressed in adipose tissue and may contribute to IR through the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, which can exacerbate IR in adipose tissue and other organs [47]. Our findings are consistent with these studies but indicate that the relationship between TXNIP and obesity in PCOS may be more complex, with TXNIP acting as an intermediary in the development of metabolic disturbances rather than directly contributing to obesity [17, 48].

We also observed significant correlations between TXNIP and triglyceride levels, as well as a negative correlation with HDL cholesterol, suggesting TXNIP’s involvement in lipid metabolism disturbances in PCOS. TXNIP regulates OS and inflammatory pathways, and its elevated expression has been linked to IR, a key feature of PCOS. Specifically, TXNIP alters lipid synthesis by influencing the expression of key enzymes involved in triglyceride production, such as fatty acid synthase and diacylglycerol acyltransferase, which are critical in the formation and storage of lipids in adipose tissue and the liver [49]. This dysregulation of lipid metabolism may contribute to the elevated triglyceride levels and reduced HDL cholesterol characteristic of PCOS [6, 50]. Additionally, TXNIP’s interaction with OS pathways could reduce HDL’s antioxidative properties, exacerbating the risk of atherosclerosis. Furthermore, a positive correlation between TXNIP and HCY levels was observed, with HCY being a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Elevated HCY promotes endothelial dysfunction, thrombosis, and arterial stiffness, all of which increase cardiovascular risk. TXNIP may amplify these harmful effects by promoting oxidative damage and inflammatory processes, thereby intensifying the cardiovascular risks seen in PCOS patients [51]. These findings underscore the potential of TXNIP as a biomarker for managing metabolic and cardiovascular complications in women with PCOS [14, 43].

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, its cross-sectional design inherently limits the ability to infer causality; therefore, the associations observed between TXNIP levels and metabolic parameters in PCOS patients should be interpreted as correlative rather than mechanistic. Functional validation through in vitro or in vivo models, such as TXNIP knockdown or overexpression systems, was beyond the scope of this study but would be necessary to elucidate the biological role of TXNIP in IR. Second, the study was conducted at a single medical center in China with an ethnically homogeneous cohort, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to broader or more diverse populations. Third, although our total sample size was reasonably large, the subgroup of obese PCOS patients was relatively small, potentially reducing the statistical power to detect subgroup-specific effects [52]. Fourth, the study did not account for key lifestyle and genetic confounders, such as dietary patterns, levels of physical activity, and genetic susceptibility, which may influence both TXNIP expression and insulin sensitivity. While adjustments were made for basic covariates including age and BMI, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded [53]. Fifth, our assessment of IR was based on surrogate indices like HOMA-IR rather than gold-standard methods such as the hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp, which may limit the precision of metabolic characterization [54]. Sixth, protein-level validation of TXNIP was not performed; techniques such as immunohistochemistry or Western blotting, as well as analysis of mRNA-protein correlations, were not included and remain essential to support the translational relevance of our transcriptional findings. Seventh, due to incomplete treatment data, we were unable to assess the potential influence of pharmacological interventions-such as metformin use-on TXNIP levels or IR, which could confound interpretation of the results [55]. These limitations underscore the exploratory nature of this study and highlight the need for future mechanistic and longitudinal investigations to determine the functional relevance of TXNIP in PCOS-associated IR [45].

Conclusion

This study highlights the TXNIP’s role in IR and metabolic dysfunction in PCOS patients. The elevated TXNIP levels were linked to IR and dyslipidemia, suggesting its potential as a biomarker of metabolic dysfunction. Further research is needed to understand its mechanisms and assess its role in improving metabolic health in obesity-induced IR in PCOS patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all participants in this study, as well as to the Hangzhou Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, for their invaluable support throughout this project.

Author contributions

Author contribution The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: MD, ZZ, and YC; study conduct: MD and ZZ; Data collection: VS; Analysis and interpretation of results: HZ and YC; Draft manuscript preparation: MD and HZ. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hangzhou Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (Nos. OO20190291 and Z20200007), the Zhejiang Province Science and Technology Program (Nos. WKJ-ZJ-2010, 2021 KY261, and 2021442135), and the Hangzhou Medical and Health Science and Technology Major Project (No. Z20250245). Author HZ has received research funding related to this work.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou Women’s Hospital (approval number: 2018–04-03), in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before participation, all participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. All sampling and laboratory procedures were conducted following the ethical guidelines of the hospital’s Ethics Committee, ensuring participant privacy and safety. Identifiers were removed from data to maintain confidentiality, and all data were stored securely.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Joham AE, Norman RJ, Stener-Victorin E, Legro RS, Franks S, Moran LJ, Boyle J, Teede HJ (2022) Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 10(9):668–680. 10.1016/s2213-8587(22)00163-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miazgowski T, Martopullo I, Widecka J, Miazgowski B, Brodowska A (2021) National and regional trends in the prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome since 1990 within Europe: the modeled estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Arch Med Sci 17(2):343–351. 10.5114/aoms.2019.87112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahmatnezhad L, Moghaddam-Banaem L, Behroozi-Lak T, Shiva A, Rasouli J (2023) Association of insulin resistance with polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypes and patients’ characteristics: a cross-sectional study in Iran. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 21(1):113. 10.1186/s12958-023-01160-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W, Pang Y (2021) Metabolic syndrome and PCOS: pathogenesis and the role of metabolites. Metabolites. 10.3390/metabo11120869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jabczyk M, Nowak J, Jagielski P, Hudzik B, Kulik-Kupka K, Włodarczyk A, Lar K, Zubelewicz-Szkodzińska B (2023) Metabolic deregulations in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Metabolites. 10.3390/metabo13020302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo F, Gong Z, Fernando T, Zhang L, Zhu X, Shi Y (2022) The lipid profiles in different characteristics of women with PCOS and the interaction between dyslipidemia and metabolic disorder states: a retrospective study in chinese population. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13:892125. 10.3389/fendo.2022.892125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao H, Zhang J, Cheng X, Nie X, He B (2023) Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome across various tissues: an updated review of pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Ovarian Res 16(1):9. 10.1186/s13048-022-01091-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeanes YM, Reeves S (2017) Metabolic consequences of obesity and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: diagnostic and methodological challenges. Nutr Res Rev 30(1):97–105. 10.1017/s0954422416000287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anagnostis P, Tarlatzis BC, Kauffman RP (2018) Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS): Long-term metabolic consequences. Metabolism 86:33–43. 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabakchieva P, Gateva A, Velikova T, Georgiev T, Yamanishi K, Okamura H, Kamenov Z (2022) Elevated levels of interleukin-18 are associated with several indices of general and visceral adiposity and insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Endocrinol Metab 66(1):3–11. 10.20945/2359-3997000000442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kabakchieva P, Gateva A, Velikova T, Georgiev T, Yamanishi K, Okamura H, Kamenov Z (2024) Meteorin-like protein and zonulin in polycystic ovary syndrome: exploring associations with obesity, metabolic parameters, and inflammation. Biomedicines. 10.3390/biomedicines12010222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hecht Baldauff N, Arslanian S (2015) Optimal management of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescence. Arch Dis Child 100(11):1076–1083. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, Legro RS, Balen AH, Lobo R, Carmina E, Chang J, Yildiz BO, Laven JS et al (2012) Consensus on women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril 97(1):28-38.e25. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qayyum N, Haseeb M, Kim MS, Choi S (2021) Role of thioredoxin-interacting protein in diseases and its therapeutic outlook. Int J Mol Sci. 10.3390/ijms22052754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spindel ON, World C, Berk BC (2012) Thioredoxin interacting protein: redox dependent and independent regulatory mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal 16(6):587–596. 10.1089/ars.2011.4137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(2004) Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 19(1):41–47. 10.1093/humrep/deh098 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wu J, Wu Y, Zhang X, Li S, Lu D, Li S, Yang G, Liu D (2014) Elevated serum thioredoxin-interacting protein in women with polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with insulin resistance. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 80(4):538–544. 10.1111/cen.12192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baptiste CG, Battista MC, Trottier A, Baillargeon JP (2010) Insulin and hyperandrogenism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 122(1–3):42–52. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasoohi S, Ismael S, Ishrat T (2018) Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) in cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases: regulation and implication. Mol Neurobiol 55(10):7900–7920. 10.1007/s12035-018-0917-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong K, Xu G, Grayson TB, Shalev A (2016) Cytokines regulate β-Cell Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) via distinct mechanisms and pathways. J Biol Chem 291(16):8428–8439. 10.1074/jbc.M115.698365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shalev A (2014) Minireview: Thioredoxin-interacting protein: regulation and function in the pancreatic β-cell. Mol Endocrinol 28(8):1211–1220. 10.1210/me.2014-1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alhawiti NM, Al Mahri S, Aziz MA, Malik SS, Mohammad S (2017) TXNIP in metabolic regulation: physiological role and therapeutic outlook. Curr Drug Targets 18(9):1095–1103. 10.2174/1389450118666170130145514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Yang J, Wang Y, Chen Y, Wang Y, Kuang H, Feng X (2023) Upregulation of TXNIP contributes to granulosa cell dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome via activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Mol Cell Endocrinol 561:111824. 10.1016/j.mce.2022.111824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamed IN, Li L, Ismael S, Ishrat T, El-Remessy AB (2021) Thioredoxin interacting protein, a key molecular switch between oxidative stress and sterile inflammation in cellular response. World J Diabetes 12(12):1979–1999. 10.4239/wjd.v12.i12.1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, Dokras A, Laven J, Moran L, Piltonen T, Norman RJ (2018) Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 33(9):1602–1618. 10.1093/humrep/dey256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Na Z, Jiang H, Meng Y, Song J, Feng D, Fang Y, Shi B, Li D (2022) Association of galactose and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. EClinicalMedicine 47:101379. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Chen J, Qin Q, Zhao D, Dong B, Ren Q, Yu D, Bi P, Sun Y (2018) Chronic pain and its association with obesity among older adults in China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 76:12–18. 10.1016/j.archger.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abruzzese GA, Cerrrone GE, Gamez JM, Graffigna MN, Belli S, Lioy G, Mormandi E, Otero P, Levalle OA, Motta AB (2017) Lipid accumulation product (LAP) and Visceral adiposity index (VAI) as markers of insulin resistance and metabolic associated disturbances in young argentine women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Horm Metab Res 49(1):23–29. 10.1055/s-0042-113463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amato MC, Vesco R, Vigneri E, Ciresi A, Giordano C (2015) Hyperinsulinism and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): role of insulin clearance. J Endocrinol Invest 38(12):1319–1326. 10.1007/s40618-015-0372-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez-Garrido MA, Tena-Sempere M (2020) Metabolic dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: pathogenic role of androgen excess and potential therapeutic strategies. Mol Metab 35:100937. 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewandowski KC, Skowrońska-Jóźwiak E, Łukasiak K, Gałuszko K, Dukowicz A, Cedro M, Lewiński A (2019) How much insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome? Comparison of HOMA-IR and insulin resistance (Belfiore) index models. Arch Med Sci 15(3):613–618. 10.5114/aoms.2019.82672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabbani N, Xue M, Weickert MO, Thornalley PJ (2021) Reversal of insulin resistance in overweight and obese subjects by trans-resveratrol and hesperetin combination-link to dysglycemia, blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and low-grade inflammation. Nutrients. 10.3390/nu13072374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, Chng WJ (2013) Roles of thioredoxin binding protein (TXNIP) in oxidative stress, apoptosis and cancer. Mitochondrion 13(3):163–169. 10.1016/j.mito.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaur S, Archer KJ, Devi MG, Kriplani A, Strauss JF 3rd, Singh R (2012) Differential gene expression in granulosa cells from polycystic ovary syndrome patients with and without insulin resistance: identification of susceptibility gene sets through network analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(10):E2016-2021. 10.1210/jc.2011-3441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Ismael S, Nasoohi S, Sakata K, Liao FF, McDonald MP, Ishrat T (2019) Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) associated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Alzheimers Dis 68(1):255–265. 10.3233/jad-180814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oslowski CM, Hara T, O’Sullivan-Murphy B, Kanekura K, Lu S, Hara M, Ishigaki S, Zhu LJ, Hayashi E, Hui ST et al (2012) Thioredoxin-interacting protein mediates ER stress-induced β cell death through initiation of the inflammasome. Cell Metab 16(2):265–273. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chutkow WA, Birkenfeld AL, Brown JD, Lee HY, Frederick DW, Yoshioka J, Patwari P, Kursawe R, Cushman SW, Plutzky J et al (2010) Deletion of the alpha-arrestin protein Txnip in mice promotes adiposity and adipogenesis while preserving insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 59(6):1424–1434. 10.2337/db09-1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao YC, Zhu J, Song GY, Li XS (2015) Relationship between thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) and islet β-cell dysfunction in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and hypertriglyceridemia. Int J Clin Exp Med 8(3):4363–4368 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dobosz AM, Dziewulska A, Dobrzyń A (2018) Spotlight on epigenetics as a missing link between obesity and type 2 diabetes. Postepy Biochem 64(2):157–165. 10.18388/pb.2018_126 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Koenen TB, Stienstra R, van Tits LJ, de Graaf J, Stalenhoef AF, Joosten LA, Tack CJ, Netea MG (2011) Hyperglycemia activates caspase-1 and TXNIP-mediated IL-1beta transcription in human adipose tissue. Diabetes 60(2):517–524. 10.2337/db10-0266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lei Z, Chen Y, Wang J, Zhang Y, Shi W, Wang X, Xing D, Li D, Jiao X (2022) Txnip deficiency promotes β-cell proliferation in the HFD-induced obesity mouse model. Endocr Connect. 10.1530/ec-21-0641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang D, Cheng C, Cao M, Wang T, Chen X, Zhao Y, Wang B, Ren Y, Liu D, Liu L et al (2020) TXNIP hypomethylation and its interaction with obesity and hypertriglyceridemia increase type 2 diabetes mellitus risk: a nested case-control study. J Diabetes 12(7):512–520. 10.1111/1753-0407.13021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polak K, Czyzyk A, Simoncini T, Meczekalski B (2017) New markers of insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 40(1):1–8. 10.1007/s40618-016-0523-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagaraj K, Lapkina-Gendler L, Sarfstein R, Gurwitz D, Pasmanik-Chor M, Laron Z, Yakar S, Werner H (2018) Identification of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) as a downstream target for IGF1 action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115(5):1045–1050. 10.1073/pnas.1715930115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li M, Chi X, Wang Y, Setrerrahmane S, Xie W, Xu H (2022) Trends in insulin resistance: insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7(1):216. 10.1038/s41392-022-01073-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hua Y, Yin Z, Li M, Sun H, Shi B (2024) Correlation between circulating advanced glycation end products and thioredoxin-interacting protein levels and renal fat content in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetol Metab Syndr 16(1):144. 10.1186/s13098-024-01361-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rohm TV, Meier DT, Olefsky JM, Donath MY (2022) Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 55(1):31–55. 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barber TM, Hanson P, Weickert MO, Franks S (2019) Obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome: implications for pathogenesis and novel management strategies. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health 13:1179558119874042. 10.1177/1179558119874042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chutkow WA, Patwari P, Yoshioka J, Lee RT (2008) Thioredoxin-interacting protein (Txnip) is a critical regulator of hepatic glucose production. J Biol Chem 283(4):2397–2406. 10.1074/jbc.M708169200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butler AE, Moin ASM, Reiner Ž, Sathyapalan T, Jamialahmadi T, Sahebkar A, Atkin SL (2023) High density lipoprotein-associated proteins in non-obese women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 14:1117761. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1117761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ganguly P, Alam SF (2015) Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr J 14:6. 10.1186/1475-2891-14-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faber J, Fonseca LM (2014) How sample size influences research outcomes. Dental Press J Orthod 19(4):27–29. 10.1590/2176-9451.19.4.027-029.ebo [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raghavan S, Jablonski K, Delahanty LM, Maruthur NM, Leong A, Franks PW, Knowler WC, Florez JC, Dabelea D (2021) Interaction of diabetes genetic risk and successful lifestyle modification in the Diabetes Prevention Programme. Diabetes Obes Metab 23(4):1030–1040. 10.1111/dom.14309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tam CS, Xie W, Johnson WD, Cefalu WT, Redman LM, Ravussin E (2012) Defining insulin resistance from hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps. Diabetes Care 35(7):1605–1610. 10.2337/dc11-2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chai TF, Hong SY, He H, Zheng L, Hagen T, Luo Y, Yu FX (2012) A potential mechanism of metformin-mediated regulation of glucose homeostasis: inhibition of Thioredoxin-interacting protein (Txnip) gene expression. Cell Signal 24(8):1700–1705. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.