Abstract

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) has emerged as a promising tool for non-invasive vascular imaging in dermatology. However, the field lacks standardized methods for processing and analyzing these complex images, as well as sufficient annotated datasets for developing automated analysis tools. We present DERMA-OCTA, the first open-access dermatological OCTA dataset, comprising 330 volumetric scans from 74 subjects with various skin conditions. The dataset contains the original 2D and 3D OCTA acquisitions, as well as versions processed with five different preprocessing methods, and the reference 2D and 3D segmentations. For each version, segmentation labels are provided, generated using the U-Net architecture as 2D and 3D segmentation approaches. By providing high-resolution, annotated OCTA data across a range of skin pathologies, this dataset offers a valuable resource for training deep learning models, benchmarking segmentation algorithms, and facilitating research into non-invasive skin imaging. The DERMA-OCTA dataset is freely downloadable.

Subject terms: Optical imaging, Biomedical engineering

Background & Summary

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) has received much attention in recent years due to its non-invasiveness, label-free, and high-resolution properties1,2. OCTA is an extension of optical coherence tomography (OCT), which exploits the backscattering principle of light mainly in the near-infrared region irradiating the biological tissue to obtain morphological information. OCTA expands the morphological analysis to include a functional analysis by extracting angiographic information from consecutive OCT acquisitions, allowing the in vivo, 3D visualization and quantification of the vascular network. OCTA was firstly applied in ophthalmology demonstrating its ability to create detailed images of blood vessels of the retina in different clinical conditions, such as diabetic retinopathy3,4, age-related macular degeneration5, glaucoma6, and retinal vein occlusion7. The high-resolution images of the radial peripapillary capillary network and the intermediate and deep capillary plexuses in the eye made OCTA a powerful tool for the study of pathogenesis of eye diseases as well as a go-to solution for the development and evaluation of new treatments.

Motivated by the success of OCTA in ophthalmology, there is a growing effort to apply OCTA in dermatology. However, there are specific challenges in applying OCTA technology from ophthalmology to dermatology. Skin tissue is extremely heterogeneous, with multiple scattering layers and varying optical properties, in contrast to the eye’s comparatively homogeneous and transparent structures. Increased motion artifacts, variable penetration depth, and complex light scattering patterns are some of the ways that this complexity degrades imaging quality. Moreover, other factors such as skin temperature, recent caffeine or other vaso-active substances consumption, and pressure applied to the skin during image acquisition could physiologically influence vessel visibility and alter flow-based indices. Despite these challenges, previous studies have shown how OCTA enables the assessment of various dermatological diseases and skin conditions, including melanoma, non-melanocytic skin cancer, psoriasis and peri-ulcerous skin8–11. Moreover, investigations applying OCTA revealed altered capillary structures and increased blood perfusion at the borders of venous leg ulcers compared to healthy skin, indicating potential use of OCTA to non-invasively assess pathological vascular alterations in chronic wounds12. OCTA imaging led to the successful identification of distinct microvascular features in nevi, achieving a differential diagnosis between melanomas and benign melanocytic lesions with high predictive accuracy, potentially reducing unnecessary biopsies13. Port wine birthmarks (PWBs) were also investigated using OCTA, demonstrating that purple PWBs have superficial vessels located closer to the epidermis compared to pink PWBs, which could influence the choice of laser treatment parameters. Additionally, vessel depth in PWBs was associated with age and color, showing distinct changes in vessel depth as patients age14. More recently, the application of OCTA was expanded to chronic venous disease (CVD) revealing specific microvascular patterns for each stage of the disease15. For CVD patients, the disease severity was classified using the clinical-etiology-anatomic-pathophysiologic (CEAP) classification16. Following the CEAP classification system, stage C1 includes patients with telangiectasias, C2 indicates varicose veins, C3 indicates lower leg edema, C4a, b, and c indicate different kinds of skin alternations associated with CVD, C5 indicates a healed venous leg ulcer and C6 an active ulceration. Using OCTA imaging, characteristic vascular patterns could be identified for the following stages: patients with C1 and C4c displayed significantly larger vessel radii compared to healthy controls; vessel length decreased as CVD progressed from stage C1 to C5; vessel tortuosity increased from stage C4 to C6 and patients in stage C6 showed increased microvascular density compared to healthy controls15.

Most of the reported studies have examined OCTA both qualitatively and quantitatively, enhancing its relevance and diagnostic value. Quantitative analysis of vasculature using OCTA is crucial for standardizing clinical interpretation, with key indicators such as vessel density, diameter and length9,12. Previous studies have shown that segmentation errors in OCTA can compromise vessel density measurements in both healthy eyes and in those affected by diabetic macular edema, which can significantly impact diagnostic accuracy4,17. Advances in OCTA segmentation have recently been driven by technological improvements, especially in deep learning. Indeed, artificial intelligence (AI) methods have been increasingly adopted in ophthalmology, leading to significant improvements in segmentation accuracy and automation18. It is well known that the output of an AI-based algorithm is strictly dependent on the quality of the input data. To improve the generalizability of the networks and to avoid a performance drop during testing, it is increasingly important to harmonize and enhance images with unwanted variability, such as OCTA data from different devices, from skin samples with different optical properties and affected by different artefacts19.

Beyond the initial challenges of image acquisition, dermatological OCTA faces significant obstacles in data analysis and interpretation. Vessel segmentation, crucial for quantitative analysis, becomes particularly complex due to the three-dimensional nature of skin vasculature, varying vessel architectures across different pathologies, and the presence of tissue-specific artifacts. Furthermore, this research field currently lacks both standardized methods for processing these complex images and sufficient annotated datasets for developing automated analysis tools19. The retinal OCTA community instead has recently taken its first steps to standardize its workflow: a unified framework for data acquisition, analysis, and reporting has been proposed20, and a cross-platform toolbox now allows microvascular metrics to be extracted from retinal scans produced by different instruments21.

To address these limitations and drive the research field of dermatological OCTA forward, in this paper we introduce a new dermatological OCTA dataset named DERMA-OCTA22. Specifically, a cohort of 74 subjects was recruited at the Department of Dermatology at the Medical University of Vienna. A total of 330 OCTA volumes were acquired, with each 3D volume covering a skin surface area of approximately 1 cm2 and a depth of 1 mm. For each original volume, multiple processed versions were generated in both 2D and 3D formats. DERMA-OCTA22 represents the first open-access collection of OCTA images specifically dedicated to dermatology, providing an unprecedented resource for researchers worldwide.

OCTA datasets

Despite the rapid growth of public OCTA datasets in retinal research, OCTA data for vascular segmentation in dermatological applications remains largely unexplored. OCTA datasets like Giarratano23, ROSE24, OCTA-50025 and Soul26 have emerged in the last decade, each dedicated to advancing vessel segmentation in retinal OCTA images. The specifications of the mentioned datasets, compared to those of our dataset DERMA-OCTA22, are reported in Table 1. The Giarratano dataset23 focuses solely on healthy vascular structures, providing OCTA projection maps from 11 subjects to study standard vessel patterns. The ROSE dataset24 includes vessel annotations to support detailed segmentation tasks in both superficial and deeper retinal layers, broadening its application for developing precise vascular models. The ROSE dataset includes more subjects and OCTA images with higher resolution compared to the Giarratano dataset. OCTA-50025 offers an even more extensive dataset that includes a diverse array of retinal images and vessel segmentation labels across multiple fields of view, enhancing model generalization potential. The more recent Soul dataset26 collects 2D OCTA images from 53 patients and focuses on Branch retinal vein occlusion disease, implementing a human-machine collaborative annotation framework.

Table 1.

Summary of public OCTA datasets for vessel segmentation.

| Giarratano23 | ROSE24 | OCTA-50025 | Soul26 | DERMA-OCTA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application | Ophtalmoloy | Ophtalmology | Ophtalmology | Ophtalmology | Dermatology |

| Subjects | 11 | 151 | 500 | 53 | 74 |

| Diseases | — | — | >12 | 1 | 7 |

| #Samples | 55 images | 229 images | 500 volumes | 178 images | 330 volumes |

| 2D/3D | 2D | 2D | From 3D to 2D | 2D | 3D and 2D |

| FOV (mm2) | 3 × 3 | 3 × 3 |

6 × 6 3 × 3 |

6 × 6 | 10 × 10 |

| Resolution (pixel) | (91,91) |

(304,304) (512,512) |

(640,400,400) (640,304,304) |

(304,304) | (90,512,483) |

Vessel segmentation

Although OCTA devices naturally acquire three-dimensional data, the vast majority of studies employ segmentation methods on 2D images rather than analyzing 3D volumes. This preference is primarily due to artifacts that hinder accurate visualization of the volumetric vascular network. Moreover, this limitation is particularly evident in the lack of 3D ground truth segmentations, especially in dermatological applications where AI-based techniques remain less developed compared to ophthalmology18.

In ophthalmology, both traditional and AI-based methods are used to segment the vasculature in OCTA data. Most traditional techniques rely on simple thresholding, often supplemented by processes to reduce noise and artifacts27. Other studies have proposed a graph reasoning convolutional neural network (CGNet)28 and a transformer model29 to segment vessels in retinal 2D images. Although some research has been carried out for pseudo-3D segmentation, e.g. reconstructing the 3D volume from 2D segmentations output by a classical U-Net30, using a layer attention network31 or an image projection network25 to perform 3D-to-2D segmentation, a relatively small amount of studies are available to obtain 3D labels32,33. In dermatological applications, the field remains particularly limited, with existing studies primarily relying on basic thresholding-based methods for vessel segmentation9,34.

Common OCTA preprocessing techniques

OCTA imaging in dermatology presents unique challenges compared to ophthalmology, particularly in terms of noise susceptibility due to the heterogeneous nature of skin tissue layers, but some general challenges are also common among different applications. A significant common challenge is the projection artifact (or tail artifact), where scattered and reflected light from superficial layers creates false blood signals in deeper tissue regions. Numerous studies have explored solutions to these issues in OCTA imaging in the ophthalmology field35. Projection artifacts can be attenuated using a simple slab subtraction method that consists in subtracting weighted values from the first layers of the volume to the deeper ones36. Unfortunately, this method results in a loss of vascular detail and continuity. More advanced methods focus on the application of k-mean classifiers to distinguish between superficial and deep vascular structures37,38 or use an exponential decrease in intensity along the depth direction39. Another study employs EnhVess, a 3D convolutional neural network (CNN) specifically trained to address this issue40.

The application of Gaussian or median filtering, as well as contrast enhancement, is crucial for improving image clarity and reducing noise. These preprocessing techniques improve the visibility of critical structures, thus supporting the clinician in the visual analysis and automated processing tasks including segmentation, quantification, and classification. Efforts have been made to denoise OCTA images using both traditional and AI-based methods. For instance, Ma et al. demonstrated improvements in the segmentation performance after applying a contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) algorithm to the OCTA data41, and Abu-Qamar et al. implemented a deep-learning pseudo-averaging algorithm to enhance the quality of retinal OCTA images42. Gaussian filtering has also been used to pre-process the OCTA projections acquired on human skin43. Other commonly employed preprocessing techniques include the 3D median filter and the Frangi vesselness filter, which were used on OCTA volumes from subjects with basal cell carcinoma prior vascular parameters extraction9. Frangi filters, also known as vesselness filters, are widely used as a precursor for vessel segmentation in medical imaging due to their ability to enhance tubular structures. These filters analyze the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix, which captures the local curvature of an image, to detect regions with vessel-like characteristics such as elongated, cylindrical shapes. By assessing the scale and orientation of these structures, Frangi filters effectively suppress noise and non-vascular features while highlighting vessels across varying sizes. These filters, while valuable, present specific limitations, such as a strong dependence on the employed scale parameters and necessitating a careful parameter tuning process for obtaining optimal results44.

Recent toolkits aim to standardize the processing of retinal OCTA images. Quantitative OCTA (QOCTA) implements a series of morphological openings and blur filters to delineate the Foveal Avascular Zone (FAZ), that is the capillary-free region at the center of the fovea, and compute vessel density indices45. The OCTA Analysis Toolkit (OAT) with its processing pipeline, introduced by Girgis et al., achieves excellent repeatability for both FAZ and vessel metrics46. OCTAVA offers a configurable chain that can include median smoothing plus either a Frangi or Jerman vesselness filter before binarization47. Hojati et al.’s package first performs histogram equalization and a low-pass filter to smooth images before locating the optic disc48. Our DERMA-OCTA pipeline shares some of the previous stated blocks but is the first to integrate all of them in a volume-based workflow for dermatological data. The processing codes are exposed in an open-source repository together with the data so that future users can re-order, swap or omit steps as required.

Methods

Data collection

A cohort of 74 subjects was recruited at the Department of Dermatology at the Medical University of Vienna. The cohort included 13 healthy subjects, 52 patients with CVD and 9 patients with malignant and benign skin lesions. The subjects were between 18 and 90 years old and both female and male individuals were recruited in a balanced way.

Every subject signed an informed consent form before OCTA images were acquired. The study protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK- 1246/2013). For CVD patients, the disease severity was classified using the CEAP classification, supported by diagnostic assessments including a physical examination and duplex ultrasound. Clinical stages of the CEAP classification system range from C1 to C6, indicating increasing disease severity in higher stages. Regarding patients with malignant and benign skin lesions, our dataset included the following diagnoses: 3 squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 1 seborrheic keratosis, 4 Bowen’s disease, 4 actinic keratosis, 4 basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and 3 systemic sclerosis. Diagnosis was confirmed through biopsy and histological assessment. Contrary to CVD, malignant and benign skin lesions exhibit distinct different vascular patterns visible in OCTA images, characterized by alternating avascular and densely vascularized regions and dotted vessels. This variation prompted the evaluation of OCTA volumes obtained from these patients as a test set from different pathologies. Figure 1 shows the differences between the various patterns from patients with the specific skin conditions analyzed.

Fig. 1.

Example of OCTA acquisitions from subjects with various diagnosis: healthy skin, early-stage CVD, advanced-stage CVD, and a malignant skin lesion (specifically squamous cell carcinoma).

OCTA acquisitions were performed at the Center for Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering at the Medical University of Vienna. Each subject underwent an imaging session during which different imaging locations were investigated. A total of 330 volumes were acquired across all subjects, with an average of 4 volumes per patient (range: 1–12 volumes). Multiple images from individual patients were captured at different locations to ensure data uniqueness for each region of interest. All scans were acquired in the same laboratory at 22 ± 1 °C. Probe pressure was kept minimal through operator training (no visible skin blanching), but was not yet sensor-quantified; we are integrating an in-probe force sensor for future acquisitions. Participants followed their usual routine; no restrictions on caffeine or other vaso-active substances were imposed.

The OCT system used in our work is dedicated to research and allows high resolution imaging of the skin, as described in previous studies10,43,49. The light source is an akinetic swept source (SS-OCT-1310, Insight Photonic Solutions, US) operating at 1310 nm with a bandwidth of 29 nm. It is possible to scan a surface of 1 cm2 (512 A-lines and 512 Bscans) with 1.3 mm depth penetration in skin. The lateral and axial resolution in air is 19.5 μm and 13.7 μm, respectively. The axial resolution in air corresponds to an effective resolution of 9.8 μm in tissue, factoring in a refractive index of 1.4 for soft tissues. For this study, a specialized probe was designed to adapt the OCTA system for imaging the lower extremities. This probe possesses five degrees of freedom, allowing translation in three orthogonal directions and rotation around two reference axes. To achieve refractive index matching, a drop of distilled water was applied between the imaging window of the optical system and the skin.

Data preparation

An intensity-based algorithm50 was coded in MATLAB (R2022a, Mathworks Inc., US) to reconstruct the vasculature from 4 subsequent OCT scans. The intensity-based algorithm was chosen among other reconstruction methods51, as it proved to be the most robust to the phase instability of the laser source. The preprocessing workflow began with automatic skin surface detection and correction. As shown in Fig. 2a, the initial Bscans exhibited a surface tilt, which was mapped in 3D (Fig. 2b). The detected surface points were used to correct this tilt, ensuring all en face images were parallel to the skin surface (Fig. 2c). The first 30 cross-sections were removed from each volume as they were affected by an artefact due to the scanning pattern employed during acquisitions, resulting in final volumes of 90 px × 512 px × 483 px.

Fig. 2.

Tilt correction of the acquired volumes. Bscan of an acquired OCT volume (a), same Bscan with a red line overlay highlighting the individualized skin surface (b), same Bscan after the tilt correction (c). The scale bar refers to 0.5 mm.

To improve the image quality of dedicated OCTA image preprocessing methods, the following techniques were adopted in sequence:

Bscan normalization: each pixel’s intensity value was scaled relative to the mean intensity. After this operation, the mean intensity of the resulting image will be the same, that is 1. This suppresses the pixel intensity shift that happens in some Bscans due to patient movement during the acquisition.

Projection artifact attenuation: projection artifacts were mitigated by the implementation of a step-down exponential filtering method39.

Filtering and contrast enhancement: A 3D median filter with a kernel of dimension 3x3x3 was employed to smooth and to equalize local intensity across consecutive slices of the volume. Moreover, an enhancement of the volume contrast based on mean luminance manipulation was applied52; the pixel’s intensity was increased or decreased based on the difference between the pixel’s value and the mean luminance.

Vesselness enhancement: a 3D Hessian-based Frangi vesselness filter53 was then employed. The filter scale range was set from 4 to 6. Each value in this range corresponds to a different level of gaussian smoothing applied to the Hessian matrix calculated, allowing the filter to detect vessels of various diameters.

The filters’ parameters were determined empirically to balance noise suppression with preservation of the smallest vessels, and the resulting configuration generalized reliably to the entire dataset.

The described processing steps are shown in Fig. 3. Each step created a distinct dataset, resulting in 5 different versions of the 3D volumes. For each volume in every dataset, three average intensity projections (AIPs) were created: full-depth projection, superficial vasculature (first half of depth slices) and deep vasculature (second half of depth slices). This empirical division provided optimal visualization of both superficial and deeper vessels. Each AIP was then saturated at the 99th intensity percentile and converted to uint8 format. AIP was utilized for en face image generation, being less sensitive to extreme values caused by noise or artifacts in respect to a maximum intensity projection.

Fig. 3.

Data processing steps applied on one OCTA volume. The first row shows the en face median intensity projections (AIPs) of the superficial layer and the second row represents the en face AIPs of the deep layer. From left to right are the results from the different processing steps. The scale bar refers to 1 mm.

Segmentation labels

The ground truth for the segmentation of vessels in OCTA volumes was created using the software Amira (Amira 2020, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., US) through a semi-automatic process. Four annotators spent an average of 20 minutes per 3D volume and one technician and one clinician verified the segmentation reliability across the dataset. The objective was to generate an accurate and realistic 3D rendering of the blood vessels, minimizing the negative effects of remaining noise and artifacts. The ground truth was performed on the dataset after it underwent both Bscan normalization and Projection artifact attenuation, as raw OCTA data would have severely limited human interpretation of vessel signals.

The segmentation process consisted of multiple sequential steps. Initially, a rough segmentation was achieved through global thresholding to select relevant grey tones. Since noise frequently exhibited similar grey values to vascular regions, manual refinement was necessary. This refinement included both removal of noisy areas and addition of missed vessels, performed on individual 2D slices and in 3D views. The vessel contours were then refined using the Smooth Labels tool with a 3D kernel of size 3 × 3 × 3, enhancing uniformity and anatomical realism. As a final refinement step, isolated segments smaller than 200 voxels were automatically removed from the continuous volume.

For the creation of the 2D segmentation labels, we implemented a systematic approach based on the 3D masks. The complete 3D mask was divided into two sub-volumes: one containing the first half of the depth slices (superficial vasculature) and another containing the second half (deep vasculature). Average intensity projections (AIP) were calculated for each sub-volume by summing vessel-positive mask instances along the z-direction and normalizing by the number of z-axis pixels. These projections resulted in 2D grayscale images, which were then binarized using Otsu’s method. A similar AIP calculation was performed on the complete 3D mask to create a comprehensive projection incorporating both superficial and deeper vascular layers.

Data Records

The DERMA-OCTA22 dataset is freely downloadable at the following link: 10.5281/zenodo.15088516.

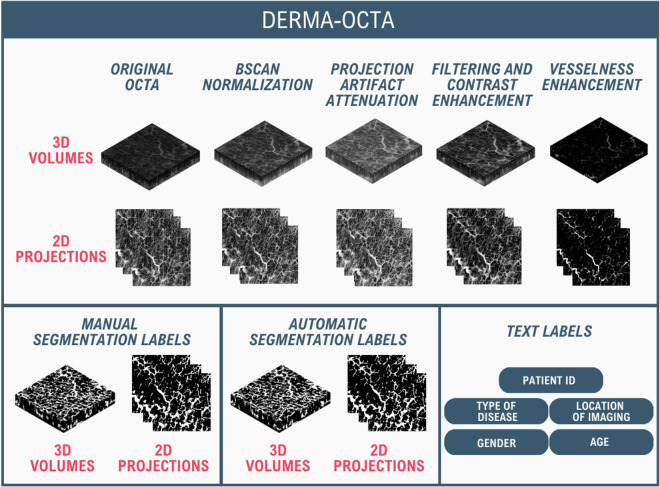

The DERMA-OCTA22 dataset encompasses 330 OCTA volumes, organized into clinical subsets. The collection includes 235 volumes from patients with CVD, 76 volumes from healthy subjects, and 19 volumes from patients with malignant and benign skin lesions. Each volume maintains consistent dimensions of 90 px × 512 px × 483 px (Z × X × Y), corresponding to physical dimensions of 0.9 mm × 10.0 mm × 9.5 mm. As illustrated in Fig. 4, every OCTA acquisition generates 24 distinct versions, stored in different formats: 3D volumes as TIF files and 2D images as PNG files:

five 3D volumes (original + one for each pre-processing step),

one 3D ground truth segmentation,

five 2D AIPs of the superficial half of the volume (original + one for each pre-processing step),

five 2D AIPs of the deeper half of the volume (original + one for each pre-processing step),

five 2D AIPs of the whole volume (original + one for each pre-processing step),

one 2D ground truth segmentation of the superficial half of the volume,

one 2D ground truth segmentation of the deeper half of the volume,

one 2D ground truth segmentation of the whole volume,

3D and 2D automatic segmentations.

Fig. 4.

Structure and contents of the DERMA-OCTA dataset.

Each OCTA volume is complemented by metadata including patient demographics (age given in 10-year age groups and gender), clinical information (disease type and imaging location), and a study-specific unique identifier.

Technical Validation

Exclusion criteria

Both the imaging physician and the recruiting clinician reviewed each OCTA volume. Any scans with artifacts that obscured in an excessive way vascular detail were excluded. Eligibility was not influenced by subjects’ age, gender or status.

OCTA segmentation

To comprehensively assess the quality of our datasets, a 2D U-Net architecture using projection images and a 3D U-Net architecture using the entire volumetric datasets were employed to segment the vessels. The U-Net54 architecture offers traditional encoder-decoder architecture with skip connections. The 2D and 3D networks were developed on the TensorFlow platform using the Keras API. Consistent with the method-dependent variability reported by Meha et al. on the segmentation of retinal OCTA images55, preliminary tests have been carried out on our dataset also with other segmentation architectures. A dedicated study detailing their results is in preparation.

The CVD volumes were distributed in a balanced manner on a patient-level basis into training, validation, test sets and a separate test set with different pathologies was also created (Table 2 and Table 3, respectively).

Table 2.

Acquired data volumes divided into train, validation and test set.

| # OCTA | Healthy | CVD C1 | CVD C2 | CVD C3 | CVD C4a | CVD C4b | CVD C4c | CVD C5 | CVD C6 | Tot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | 53 | 7 | 34 | 37 | 26 | 5 | 14 | 2 | 20 | 198 |

| Validation set | 12 | 4 | 9 | 13 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 68 |

| Test set | 11 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 45 |

Table 3.

Acquired data volumes included in the test set from different pathologies.

| # OCTA | SCC | Seborrheic keratosis | Morbus Bowen | Actinic keratosis | BCC | Systemic sclerosis | Tot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test set from different pathologies | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 19 |

The open DERMA-OCTA22 dataset also includes the automatic segmentations obtained by each implemented method, consisting of:

three 2D automatic segmentation outputs for each OCTA data, for each processing step,

one 3D automatic segmentation output for each OCTA data and for each processing step,

three 2D automatic segmentation outputs for each OCTA data extracted from the 3D automatic segmentation outputs.

Here we focus the technical validation on the U-Net segmentation as it is a widely recognized basic model. Figure 5 presents an OCTA AIP example and its corresponding automatic 2D U-Net and 3D U-Net segmentations, where overlapping manual and automatic predictions are shown in yellow, along with only automatic prediction (green) and manual ground truth mask (red). In this case, particularly noteworthy was the ability of the 2D U-Net trained segmentation network to correctly handle the intense white vertical artifact lines present in the left portion of the OCTA image.

Fig. 5.

Left: original OCTA AIP with a notable vertical artifact in the left portion. Middle: 2D U-Net segmentation (green) overlaid with the ground-truth mask (red); yellow indicates regions of perfect overlap. Right: 3D U-Net segmentation (green) overlaid with the ground-truth mask (red); yellow indicates regions of perfect overlap.

Figure 6 illustrates OCTA AIP examples processed through different preprocessing stages and segmented using the 2D U-Net network. The average Dice obtained on the various stages was equal to 82.30 ± 8.09%. All Dice results are shown in Table 4.

Fig. 6.

Qualitative segmentation results obtained with the 2D U-Net after applying preprocessing methods. Automatic predictions (green) are overlaid with ground truth masks (red).

Table 4.

Dice similarity scores (in %) of the segmentation network on 2D and 3D datasets, evaluated across different preprocessing methods.

| Original OCTA | Bscan normalization | Projection artifact attenuation | Filtering and contrast enhancement | Vesselness enhancement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D U-Net | 79.62 ± 8.45 | 81.94 ± 8.40 | 84.56 ± 9.07 | 86.34 ± 8.83 | 79.05 ± 5.68 |

| 3D U-Net | 71.32 ± 12.69 | 71.14 ± 16.46 | 64.20 ± 18.08 | 66.70 ± 18.64 | 57.23 ± 16.36 |

These initial results show that the DERMA-OCTA22 dataset may be used to support and expand the application of deep learning methods for vessel segmentation in dermatological OCTA volumes. The dataset could be extended to become more balanced with respect to various pathologies, specifically considering cancerous dermatological lesions.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the H2020-ICT-2020-2 project REAP with grant agreement ID 101016964. M.L. is funded by the H2020-MSCA-IF-2019 project SkinOpt ima with grant agreement ID 894325.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: K.M.M., G.R., M.S.; Methodology: M.S., G.R.; Validation: G.R., M.S.; Data Curation: G.R., M.S., L.K., J.D.; Writing – Original Draft: M.S., G.R., K.M.M.; Writing – Review & Editing: All authors; Supervision: K.M.M.

Code availability

The code supporting this study is openly available and archived on Zenodo22.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Giulia Rotunno, Massimo Salvi.

References

- 1.Fercher, A., Drexler, W., Hitzenberger, C. & Lasser, T. Optical Coherence Tomography—Principles and Applications, Rep. Prog. Phys, 66, 10.1088/0034-4885/66/2/204 (2003).

- 2.Spaide, R. F., Fujimoto, J. G., Waheed, N. K., Sadda, S. R. & Staurenghi, G. Optical coherence tomography angiography. Prog Retin Eye Res64, 1–55, 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.11.003 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun, Z., Yang, D., Tang, Z., Ng, D. S. & Cheung, C. Y. Optical coherence tomography angiography in diabetic retinopathy: an updated review. Eye35(1), 149–161, 10.1038/s41433-020-01233-y (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durbin, M. K. et al. Quantification of Retinal Microvascular Density in Optical Coherence Tomographic Angiography Images in Diabetic Retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol135(4), 370–376, 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0080 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tombolini, B. et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography: A 2023 Focused Update on Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol Ther13(2), 449–467, 10.1007/s40123-023-00870-2 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao, H. L. et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Glaucoma, J Glaucoma, 29(4), https://journals.lww.com/glaucomajournal/fulltext/2020/04000/optical_coherence_tomography_angiography_in.12.aspx (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Borrelli, E., Sacconi, R., Brambati, M., Bandello, F. & Querques, G. In vivo rotational three-dimensional OCTA analysis of microaneurysms in the human diabetic retina. Sci Rep9(1), 16789, 10.1038/s41598-019-53357-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu, M. & Drexler, W. Optical coherence tomography angiography and photoacoustic imaging in dermatology. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences18(5), 945–962, 10.1039/c8pp00471d (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meiburger, K. M. et al. Automatic skin lesion area determination of basal cell carcinoma using optical coherence tomography angiography and a skeletonization approach: Preliminary results. J Biophotonics12(9), e201900131, 10.1002/jbio.201900131 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, Z. et al. Non-invasive multimodal optical coherence and photoacoustic tomography for human skin imaging. Sci Rep7(1), 17975, 10.1038/s41598-017-18331-9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuh, S. et al. Imaging Blood Vessel Morphology in Skin: Dynamic Optical Coherence Tomography as a Novel Potential Diagnostic Tool in Dermatology. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb)7, 1–16, 10.1007/s13555-017-0175-4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes, J., Schuh, S., Bowling, F. L., Mani, R. & Welzel, J. Dynamic Optical Coherence Tomography Is a New Technique for Imaging Skin Around Lower Extremity Wounds. Int J Low Extrem Wounds18(1), 65–74, 10.1177/1534734618821015 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perwein, M. K. E., Welzel, J., De Carvalho, N., Pellacani, G. & Schuh, S. Dynamic Optical Coherence Tomography: A Non-Invasive Imaging Tool for the Distinction of Nevi and Melanomas. Cancers (Basel)15, 20 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehrabi, J. N. et al. Vascular characteristics of port wine birthmarks as measured by dynamic optical coherence tomography. J Am Acad Dermatol85(6), 1537–1543, 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.007 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotunno, G. et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography enables visualization of microvascular patterns in chronic venous insufficiency, iScience, 27(11), 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110998 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lurie, F. et al. The 2020 update of the CEAP classification system and reporting standards. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord8(3), 342–352, 10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.12.075 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghasemi Falavarjani, K. et al. Effect of segmentation error correction on optical coherence tomography angiography measurements in healthy subjects and diabetic macular oedema. British Journal of Ophthalmology104(2), 162, 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-314018 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meiburger, K. M., Salvi, M., Rotunno, G., Drexler, W. & Liu, M. Automatic segmentation and classification methods using optical coherence tomography angiography (Octa): A review and handbook, Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 20(11), 10.3390/app11209734 (2021).

- 19.Seoni, S. et al. All you need is Data Preparation: A Systematic Review of Image Harmonization Techniques in Multi-center/device Studies for Medical Support Systems. Comput Methods Programs Biomed250, 108200, 10.1016/j.cmpb.2024.108200 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampson, D. M., Dubis, A. M., Chen, F. K., Zawadzki, R. J. & Sampson, D. D. Towards standardizing retinal optical coherence tomography angiography: a review. Light Sci Appl11(1), 63, 10.1038/s41377-022-00740-9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Untracht, G. R. et al. Towards standardising retinal OCT angiography image analysis with open-source toolbox OCTAVA. Sci Rep14(1), 5979, 10.1038/s41598-024-53501-6 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotunno, G. et al. DERMA-OCTA. Zenodo.10.5281/zenodo.15088516 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giarratano, Y. et al. Automated Segmentation of Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Images: Benchmark Data and Clinically Relevant Metrics. Transl Vis Sci Technol9(13), 5, 10.1167/tvst.9.13.5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma, Y. et al. ROSE: A Retinal OCT-Angiography Vessel Segmentation Dataset and New Model. IEEE Trans Med Imaging40(3), 928–939, 10.1109/TMI.2020.3042802 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, M. et al. OCTA-500: A retinal dataset for optical coherence tomography angiography study. Med Image Anal93, 103092, 10.1016/j.media.2024.103092 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue, J. et al. Soul: An OCTA dataset based on Human Machine Collaborative Annotation Framework. Sci Data11(1), 838, 10.1038/s41597-024-03665-7 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu, S. et al. An optimized segmentation and quantification approach in microvascular imaging for OCTA-based neovascular regression monitoring. BMC Med Imaging21(1), 13, 10.1186/s12880-021-00546-y (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu, X. et al. CGNet-assisted Automatic Vessel Segmentation for Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. J Biophotonics15(10), e202200067, 10.1002/jbio.202200067 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan, X. et al. OCT2Former: A retinal OCT-angiography vessel segmentation transformer. Comput Methods Programs Biomed233, 107454, 10.1016/j.cmpb.2023.107454 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, M., Huang, K., Zeng, C., Chen, Q. & Zhang, W. Visualization and quantization of 3D retinal vessels in OCTA images. Opt Express32(1), 471–481, 10.1364/OE.504877 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang, C. et al. LA-Net: layer attention network for 3D-to-2D retinal vessel segmentation in OCTA images, Phys Med Biol, 69, 10.1088/1361-6560/ad2011 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Kuhlmann, J. et al. 3D Retinal Vessel Segmentation in OCTA Volumes: Annotated Dataset MORE3D and Hybrid U-Net with Flattening Transformation, in Pattern Recognition, Köthe, U. & Rother, C. Eds., pp. 291–306 Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, (2024).

- 33. Liu, Y. et al. AI-based 3D analysis of retinal vasculature associated with retinal diseases using OCT angiography. Biomed Opt Express (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Zhang, Y. et al. Automatic 3D adaptive vessel segmentation based on linear relationship between intensity and complex-decorrelation in optical coherence tomography angiography. Quant Imaging Med Surg11(3), 895–906, 10.21037/qims-20-868 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hormel, T. T., Huang, D. & Jia, Y. Artifacts and artifact removal in optical coherence tomographic angiography. Quant Imaging Med Surg11(3), 1120–1133, 10.21037/qims-20-730 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, A., Zhang, Q. & Wang, R. K. Minimizing projection artifacts for accurate presentation of choroidal neovascularization in OCT micro-angiography. Biomed Opt Express6(10), 4130–4143, 10.1364/BOE.6.004130 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, J. et al. Reflectance-based projection-resolved optical coherence tomography angiography [Invited]. Biomed Opt Express8(3), 1536–1548, 10.1364/BOE.8.001536 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, J. et al. Signal attenuation-compensated projection-resolved OCT angiography. Biomed Opt Express14(5), 2040–2054, 10.1364/BOE.483835 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahmud, M. et al. Review of speckle and phase variance optical coherence tomography to visualize microvascular networks. J Biomed Opt18, 50901, 10.1117/1.JBO.18.5.050901 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stefan, S. & Lee, J. Deep learning toolbox for automated enhancement, segmentation, and graphing of cortical optical coherence tomography microangiograms. Biomed Opt Express11(12), 7325–7342, 10.1364/BOE.405763 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma, Z., Feng, D., Wang, J. & Ma, H. Retinal OCTA Image Segmentation Based on Global Contrastive Learning. Sensors22, 9847, 10.3390/s22249847 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abu-Qamar, O. et al. Pseudoaveraging for denoising of OCT angiography: a deep learning approach for image quality enhancement in healthy and diabetic eyes. Int J Retina Vitreous9(1), 62, 10.1186/s40942-023-00486-5 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen, Z. et al. Phase-stable swept source OCT angiography in human skin using an akinetic source. Biomed. Opt. Express7(8), 3032–3048, 10.1364/BOE.7.003032 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Longo, A. et al. Assessment of hessian-based Frangi vesselness filter in optoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics20, 100200, 10.1016/j.pacs.2020.100200 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amirmoezzi, Y., Ghofrani-Jahromi, M., Parsaei, H., Afarid, M. & Mohsenipoor, N. An Open-source Image Analysis Toolbox for Quantitative Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. J Biomed Phys Eng14(1), 31–42, 10.31661/jbpe.v0i0.2106-1349 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Girgis, J. et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Analysis Toolbox: A Repeatable and Reproducible Software Tool for Quantitative Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Analysis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina54, 114–122, 10.3928/23258160-20230206-01 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Untracht, G. R. et al. OCTAVA: An open-source toolbox for quantitative analysis of optical coherence tomography angiography images, PLoS One, 16(12), pp. e0261052, 10.1371/journal.pone.0261052 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Hojati, S., Kafieh, R., Fardafshari, P., Fard, M. A. & Fouladi, H. A MATLAB package for automatic extraction of flow index in OCT-A images by intelligent vessel manipulation. SoftwareX12, 100510, 10.1016/j.softx.2020.100510 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veselka, L., Krainz, L. Mindrinos, L., Drexler, W. & Elbau, P. A Quantitative Model for Optical Coherence Tomography, Sensors, 21(20), 10.3390/s21206864 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Huang, Y. et al. Swept-Source OCT Angiography of the Retinal Vasculature Using Intensity Differentiation-based Optical Microangiography Algorithms. Ophthalmic Surgery Lasers and Imaging45, 382–389, 10.3928/23258160-20140909-08 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chu, Z. et al. Complex signal-based optical coherence tomography angiography enables in vivo visualization of choriocapillaris in human choroid. J Biomed Opt22(12), 121705, 10.1117/1.JBO.22.12.121705 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu, Y., Bao, S., Tanaka, G., Liu, Y. & Xu, D. Digital Color Image Contrast Enhancement Method Based on Luminance Weight Adjustment. IEICE Transactions on Fundamentals of Electronics, Communications and Computer SciencesE105.A(6), 983–993, 10.1587/transfun.2021EAP1083 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kroon, D.-J. Hessian based Frangi Vesselness filter. MATLAB Central File Exchange.

- 54.Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P., Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation, Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 234–241 (2015).

- 55.Mehta, N. et al. Repeatability of binarization thresholding methods for optical coherence tomography angiography image quantification. Sci Rep10(1), 15368, 10.1038/s41598-020-72358-z (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The code supporting this study is openly available and archived on Zenodo22.