Abstract

Anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies are essential for metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment, however, resistance remains problematic in KRAS/NRAS/BRAF wild-type patients. RAS protein activator-like 2 (RASAL2) regulates RAS signaling by catalyzing the conversion of RAS. This study investigates the pathogenicity of the germline RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant, identified in a high-risk family, and its potential role in CRC progression and therapy resistance. Population analysis reveals its rarity in East Asians (0.01%) but an increased prevalence in Taiwanese CRC patients (1.63%). Functional studies demonstrate that RASAL2 c.2423 A > G enhances RAS signaling, causing sustained ERK phosphorylation and increased CRC cell proliferation. Additionally, RASAL2-mutant cells require higher doses of cetuximab for ERK suppression and growth inhibition, indicating resistance to anti-EGFR therapy via abnormal RAS activation. According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria, the variant is likely pathogenic. Our study highlights RASAL2 c.2423 A > G as a potential biomarker for CRC risk and therapy response.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-16325-6.

Keywords: RASAL2, Germline variant, Pathogenic, RAS signaling, Colorectal cancer, Anti-EGFR, Resistance

Subject terms: Cancer genomics, Gastrointestinal cancer, Tumour biomarkers

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted monoclonal antibodies, such as cetuximab and panitumumab, serving as key therapeutic agents in the treatment of metastatic CRC (mCRC)1,2. However, the effectiveness of anti-EGFR therapy is significantly influenced by genomic alterations that dysregulate the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway, leading to intrinsic and acquired resistance3. Well-established predictive biomarkers of resistance include KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutations, which are now routinely assessed in clinical practice, as recommended by National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines. Beyond these mutations, alterations in other RAS pathway effectors, such as PI3K/AKT mutations4,5as well as ERBB2 and MET amplifications6,7have been identified as additional contributors to resistance mechanisms. Despite the implementation of biomarker-driven patient selection, 20–30% of KRAS/NRAS/BRAF wild-type mCRC patients remain unresponsive to anti-EGFR therapy8,9. Therefore, identifying novel genomic alterations associated with resistance is crucial to improving the efficacy of EGFR blockade and advancing personalized treatment strategies for CRC.

RAS protein activator-like 2 (RASAL2) is a RAS GTPase-activating protein (GAP) that negatively regulates RAS signaling by catalyzing the hydrolysis of RAS-GTP to its inactive GDP-bound form, thereby preventing aberrant RAS activation10. Dysregulation of RASAL2 expression has been implicated in tumorigenesis across multiple cancers, including CRC11. In CRC, RASAL2 is frequently downregulated, with lower expression correlating with more advanced disease stages12. Functional studies have demonstrated that RASAL2 suppression enhances RAS signaling, promoting cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition11. Additionally, RASAL2 has been shown to interact with importin 5 (IPO5) through its nuclear localization signal, facilitating nuclear translocation13. This translocation impairs its ability to suppress RAS signaling in the cytoplasm, thereby enhancing tumor progression and conferring resistance to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) chemotherapy. Given its central role in RAS pathway regulation, genomic alterations in RASAL2 may contribute to aberrant cell proliferation and resistance to targeted therapies, including anti-EGFR agents.

In our previous study investigating cancer-predisposing germline variants in a high-risk family14the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant emerged as one of top candidate mutations. This variant was identified in two CRC patients and three ovarian cancer patients, with strong familial segregation, suggesting a potential hereditary cancer susceptibility association (Fig. 1a). Importantly, unaffected family members did not carry the RASAL2 variant, reinforcing its potential role in cancer predisposition.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant in normal populations and cancer patients, and its co-occurrence with KRAS mutations in CRC patients. (a) The family pedigree showing the segregation of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant with cancer in a family with multiple affected members. Squares represent males, and circles represent females. Family members affected by cancer are filled in red. Deceased members are indicated by a cross. (b) The alternative allele frequency of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant across different ethnic groups. The allele frequency of the variant was compared between normal Taiwanese individuals and various ethnic populations included in the 1000 Genomes Project. (c) The frequency of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant in cancer patients. The clinico-genomic database from National Cheng Kung University Hospital was used to analyze the frequency of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant in patients with CRC, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancer. (d) The co-occurrence of KRAS mutations and the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant in CRC. KRAS mutation status was available in 196 of 367 CRC patients. No any KRAS mutation was detected in tumors from 6 patients carrying RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant; in contrast, 76 (40%) of 190 RASAL2 wild-type patients had KRAS-mutant tumors.

This study aims to investigate the pathogenicity of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant using a combination of population genetic analysis, in silico functional prediction, and in vitro experimental validation. Given the role of RASAL2 in RAS pathway regulation, we also explore its potential contribution to resistance against anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy in CRC. Our findings provide novel insights into the clinical significance of RASAL2 mutations and their potential role as biomarkers for personalized cancer treatment.

Results

Frequency of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant in the population and cancer patients

To assess the pathogenic potential of RASAL2 c.2423 A > G, we first analyzed its frequency in the general population. The variant exhibited a low prevalence in the Taiwanese population (0.4%), as shown in Fig. 1b. Data from the 1000 Genomes Project confirmed its rarity, with an allele frequency of 0.01% in East Asians and absence in South Asian, African, American, and European populations (Fig. 1b). Conversely, analysis of the NCKUH cancer patient database revealed that RASAL2 c.2423 A > G was detected in 1.63% of CRC patients, a fourfold increase compared to its frequency in the general Taiwanese population (Fig. 1c). The variant was also found in 1.08% of ovarian cancer patients and 0.7% of endometrial cancer patients, suggesting potential relevance in gynecologic malignancies.

Given the importance of KRAS as a major oncogenic driver in CRC (present in ~ 40% of cases), we investigated the co-occurrence of KRAS mutations with the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant. Among CRC patients without RASAL2 mutations, KRAS mutations were detected in 40% of cases. In contrast, no KRAS mutations were found in RASAL2 c.2423 A > G carriers, suggesting mutual exclusivity (Fig. 1d). The observed frequency differences between CRC patients and the general population, along with this exclusivity, suggest that RASAL2 c.2423 A > G may serve as a germline pathogenic variant contributing to CRC tumorigenesis.

RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant enhances RAS signaling

Since RASAL2 functions as a RAS GTPase-activating protein (GAP) that negatively regulates RAS signaling, we investigated whether the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant disrupts its function, as the hypothesis we proposed in Fig. 2a. In silico functional prediction using FATHMM (Functional Analysis through Hidden Markov Models) assigned the variant a deleterious score of 0.992, suggesting a high likelihood of pathogenicity (Fig. 2b). The prediction of protein stability by DUET, a web server for predicting the effects of missense mutations, showed this variant does not affect protein stability.

Fig. 2.

RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant mediates aberrant ERK phosphorylation in RAS wild-type CRC cells. (a) RASAL2 negatively regulates the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway by catalyzing the conversion of RAS-GTP to RAS-GDP. It is hypothesized that the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant mediates abnormal activation of the RAS pathway, contributing to tumorigenesis. (b) In silico analysis of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant was performed using the Functional Analysis Through Hidden Markov Models-Multiple Kernel Learning (FATHMM-MKL). (c) and (d) Representative confocal images and quantitative analysis showing the time course of ERK phosphorylation in HT29 cells with and without the RASAL2 c.2423 A >G variant in response to EGF (100 ng/mL) stimulation. Values represent the mean ± SEM from at least 30 individual cells across three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. p-ERK (green), phosphorylated ERK; DYK (red), DYKDDDDK-tag; HOE (blue), Hoechst 33,258. Scale bar: 60 μm. (e) and (f) Representative confocal images and quantitative analysis illustrating the changes in EGF-induced ERK phosphorylation in RASAL2 wild-type and mutant LIM1215 cells.

To experimentally validate these predictions, site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate RASAL2 c.2423 A > G mutant plasmids, which were transfected into RAS wild-type CRC cell lines (HT29, LIM1215, SW48, and NCI-H508). Following EGF stimulation, ERK phosphorylation was measured as a surrogate for RAS pathway activation. In HT29 cells expressing wild-type RASAL2, ERK phosphorylation peaked at 10 min after EGF stimulation and gradually declined over 40 min (Fig. 2c–d). In contrast, HT29 cells with the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant exhibited significantly elevated ERK phosphorylation levels, although the phosphorylation kinetics remained similar. Similar trends were observed in LIM1215, SW48, and NCI-H508 cells, where RASAL2-mutant cells exhibited consistently higher ERK phosphorylation than their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 2e–f, Figure S1a–d). The impact of RASAL2 variant on ERK phosphorylation was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 3 and Figure S1e). When RAS pulldown assay was performed to evaluate the active form of RAS, the RASAL2-mutant cells exhibited significantly higher levels of activated RAS compared to wild-type counterparts following 10 min of EGF stimulation, providing the direct evidence of RAS activity in relation to the RASAL2 variant (Figure S2). These findings indicate that the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant enhances RAS signaling upon EGF stimulation, likely by impairing RASAL2’s GAP activity.

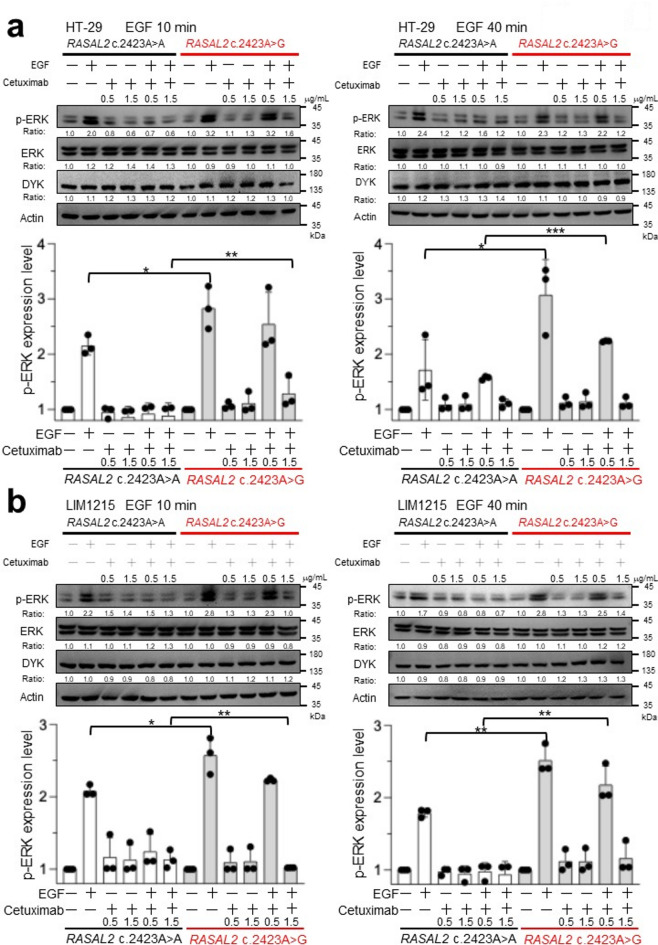

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of ERK phosphorylation in CRC cells with and without RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant. Representative western blot images showing the expression of phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), total ERK, and DYKDDDDK-tag (DYK) in HT29 (a) and LIM1215 (b) cells with and without the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant after EGF (100 ng/mL) treatment for the indicated times (upper panels). Quantification of protein expression levels is shown, representing the relative changes in the expression of each protein. Bar charts display the average relative signal intensity for the indicated time points compared to the control across three seperate experiments. Error bars represent the standard error of mean from the average of three separate experiments. The difference between each time point is tested and statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***<0.001 (lowe panels).

RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant promotes CRC cell proliferation

The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway plays a central role in tumor cell proliferation15. Given the aberrant RAS signaling observed in RASAL2-mutant cells, we evaluated its impact on CRC cell proliferation using MTT assays. HT29 cells expressing wild-type RASAL2 showed no significant difference in proliferation compared to vector controls (Fig. 4a). However, HT29 cells harboring the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant exhibited a significant increase in proliferation by Day 2 and Day 3. Similar results were observed in LIM1215 (Fig. 4b), SW48 (Figure S3a), and NCI-H508 cells (Figure S3b), further supporting that RASAL2 c.2423 A > G drives cell proliferation by aberrantly activating RAS signaling.

Fig. 4.

RASAL2 c.2423 A > G enhances the proliferation ability of CRC cells. The proliferation ability of CRC cells was assessed using the MTT assay in parental, vector-only, wild-type RASAL2 (c.2423 A > A), and mutant RASAL2 (c.2423 A > G) transfected HT29 (a) and LIM1215 cells (b). Cell viability was measured over 2 days, and results are presented as the percentage increase relative to day 0 for each cell line. Bar graphs (right) provide a visual representation of cell proliferation activity on day 2. Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. ***p < 0.001.

RASAL2 c.2423 A > G confers resistance to anti-EGFR therapy

Since mutant RAS is a well-known driver of anti-EGFR therapy resistance, and RASAL2 c.2423 A > G enhances RAS signaling, we evaluated whether this variant affects cetuximab sensitivity in CRC cells. Following EGF stimulation, ERK phosphorylation was measured in HT29 cells pretreated with cetuximab (0.5 µg/mL). In wild-type RASAL2 cells, cetuximab completely abolished EGF-induced ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 5a). However, in RASAL2-mutant cells, cetuximab failed to suppress ERK activation, and a higher concentration (1.5 µg/mL) was required to achieve inhibition. Similar resistance patterns were observed in LIM1215 (Fig. 5b), SW48 (Figure S4a), and NCI-H508 cells (Figure S4b).

Fig. 5.

A higher concentration of EGFR monoclonal antibody was required to suppress EGF-induced ERK phosphorylation in RASAL2-mutant CRC cells. Representative Western blot images from three independent experiments illustrate the levels of phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), total ERK, DYKDDDDK-tag (DYK), and actin in RASAL2 wild-type and mutant (a) HT29 and (b) LIM1215 cells treated with cetuximab. Cells were pre-treated with cetuximab at concentrations of 0.5 and 1.5 µg/mL for 72 h, followed by stimulation with EGF for 10 min (left) or 40 min (right). After EGF stimulation, cell lysates were collected and analyzed via immunoblotting using anti-p-ERK, total ERK, DYK, and actin antibodies (upper panels). The expression levels of each protein were quantified, and the relative changes are shown. Bar charts display the average relative signal intensity for each treatment compared to the control across three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard error of mean from the average of three separate experiments. The difference between each treatment is tested and statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (lowe panels).

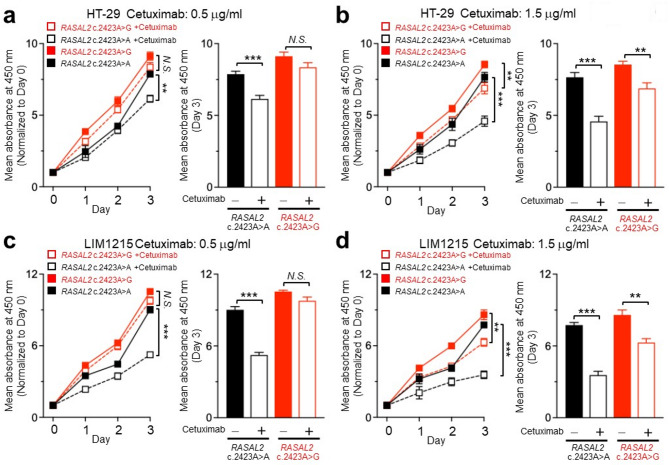

Next, we examined whether RASAL2 c.2423 A > G affects cetuximab’s ability to suppress CRC cell proliferation. Wild-type RASAL2-expressing cells treated with 0.5 µg/mL cetuximab showed significant inhibition of proliferation (Fig. 6a). However, RASAL2-mutant cells continued to proliferate despite cetuximab treatment, requiring a higher dose (1.5 µg/mL) to achieve suppression (Fig. 6b–d). Interestingly, while higher cetuximab concentrations were required to suppress ERK phosphorylation in SW48 and NCI-H508 cells, cell proliferation was effectively inhibited at 0.5 µg/mL in these lines (Figures S5a–d). This suggests that other EGFR-regulated pathways, such as PI3K/AKT and PLC-γ1-PKC, may also contribute to proliferation in these models. Together, these findings demonstrate that RASAL2 c.2423 A > G promotes resistance to anti-EGFR therapy and RASAL2-meidated aberrant RAS signaling might be the mechanism mediating the resistance.

Fig. 6.

RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant confers resistance to anti-EGFR antibody in CRC cells. (a) and (b) The proliferation ability of RASAL2 wild-type and mutant HT29 cells treated with cetuximab over a 3-day period. HT29 cells were transfected with wild-type (c.2423 A > A) and mutant RASAL2 (c.2423 A > G), and cell proliferation was assessed using the MTT viability assay after treatment with cetuximab at concentrations of 0.5 and 1.5 µg/mL (left). Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the absorbance reading on day 0, and the results on day 3 were compared between HT29 cells with and without cetuximab treatment (right). (c) and d, The proliferation ability of RASAL2 wild-type and mutant LIM1215 cells treated with cetuximab at concentrations of 0.5 and 1.5 µg/mL over a 3-day period. Results are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted using Student’s t-test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; N.S., p ≥ 0.05 (not significant).

Discussion

RASAL2, a RAS GTPase-activating protein, plays a crucial role in regulating RAS signaling by converting RAS-GTP to RAS-GDP. In this study, we identified the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant as a likely pathogenic germline mutation associated with CRC and resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. Our findings are supported by several lines of evidence: (i) The RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant segregates with cancer in a high-risk family. (ii) It is rare in the general population but enriched in Taiwanese CRC patients. (iii) RASAL2-mutant CRC cells show increased EGF-induced ERK phosphorylation compared to wild-type cells. (iv) The variant promotes enhanced cell proliferation, indicating a functional impact. (v) A higher dose of cetuximab is required to suppress ERK activation and inhibit proliferation in RASAL2-mutant cells, suggesting therapeutic resistance. These results establish RASAL2 c.2423 A > G as a critical factor in CRC tumorigenesis and anti-EGFR therapy resistance.

Here we show the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant clinical implications and pathogenicity classification. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines for variant classification were applied to RASAL2 c.2423 A > G based on multiple lines of evidence:

Strong Evidence: In vitro functional assays demonstrated aberrant activation of RAS signaling and increased proliferation in RASAL2-mutant cells (Figs. 2 and 3).

Moderate Evidence: The variant is extremely rare in general populations (Fig. 1B).

Supporting Evidence: Familial segregation analysis confirmed the presence of RASAL2 c.2423 A > G in multiple cancer-affected relatives, with its absence in unaffected family members (Fig. 1A).

Based on one strong, one moderate, and one supporting criterion, RASAL2 c.2423 A > G is classified as a likely pathogenic germline variant according to ACMG guidelines16.

Accurate interpretation of germline variants is essential for genetic counseling and personalized therapy17. Previous studies have shown that RASAL2 acts as a tumor suppressor in CRC12,18. While somatic RASAL2 mutations have been linked to clinical outcomes in CRC19, a germline variant predisposing to hereditary cancer has not been previously reported. Based on segregation, population frequency, and in vitro functional data, the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant meets ACMG criteria for likely pathogenicity. Given its prevalence in East Asian populations, our findings support the inclusion of RASAL2 in hereditary cancer panels, aiding risk assessment and treatment decisions.

We also demonstrate the association between RASAL2 and drug resistance. Previous studies have linked RASAL2 to chemoresistance by modulating RAS activity and nuclear translocation13. In triple-negative breast cancer, high RASAL2 expression conferred resistance to multiple chemotherapies20. Similarly, RASAL2 mutations have been identified as potential mechanisms of resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer21. Our findings demonstrate that CRC cells harboring RASAL2 c.2423 A > G exhibit reduced sensitivity to cetuximab, requiring higher drug concentrations to inhibit ERK phosphorylation and cell proliferation. This suggests that CRC patients carrying this variant may require dose adjustments or alternative targeted therapies. In a recent study19, a germline RASAL2 variant (rs12028023) was associated with longer survival in mCRC patients receiving oxaliplatin, 5-FU, and cetuximab, potentially due to underlying resistance mechanisms. If future clinical studies validate our findings, RASAL2 c.2423 A > G could serve as a predictive biomarker for anti-EGFR therapy response.

To further investigate the resistance mechanism, we examined the impact of RASAL2 c.2423 A > G on ERK phosphorylation and cell proliferation across multiple CRC cell lines. A higher dose of cetuximab was required to suppress the proliferation of RASAL2-mutant CRC cells compared to those without RASAL2 variant (Fig. 6). At the same time, we also observed a higher concentration of cetuximab was needed to inhibit EGF-induced ERK phosphorylation in RASAL2-mutant cells than those without RASAL2 variant (Fig. 5). These results suggest RASAL2 c.2423 A > G was associated with the resistance to anti-EGFR therapy and aberrant RAS signaling caused by RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant might be the mechanism mediating the resistance. More studies are still needed to confirm this potential resistant mechanism. While cetuximab effectively suppressed proliferation in SW48 and NCI-H508 cells, despite the presence of the variant, resistance was observed in HT29 and LIM1215 cells. This suggests that EGFR-driven proliferation in some CRC cells may not rely solely on RAS/MEK/ERK signaling but could involve alternative pathways such as PI3K/AKT, PLC-γ1-PKC, or SRC22. Indeed, previous studies show that PI3K inhibitors suppress SW48 growth23,24, while NCI-H508 proliferation is primarily PI3K/AKT-driven25. As RASAL2 c.2423 A > G is a germline variant, its pathogenic role may depend on the cellular context. It is likely that CRC cells carrying this mutation become dependent on abnormal RAS activation, making it the dominant pathway mediating proliferation. Further in vivo and clinical studies are necessary to validate these findings and explore targeted combination therapies to overcome resistance. Interestingly, HT29 cells carry the BRAF V600E mutation, which leads to constitutive activation of BRAF and downstream RAS signaling. Despite this, the presence of the RASAL2 mutation still influenced cetuximab sensitivity in HT29 cells. Current clinical guidelines do not recommend anti-EGFR antibody, alone or in combination with chemotherapy, for patients with BRAF V600E-mutant CRC. As such, the RASAL2 mutation is unlikely to affect the clinical selection of targeted therapy when combining chemotherapy. However, combination therapy with an anti-EGFR antibody and a BRAF inhibitor, with or without chemotherapy, is now the standard first- and second-line treatment for BRAF V600E-mutated metastatic CRC26,27. The association between the RASAL2 mutation and the resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in HT29 cells raises the possibility that the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant could also be a potential predictive biomarker in BRAF V600E-mutant CRC when anti-EGFR antibodies are part of a BRAF inhibitor-based regimen.

Methods

Patient population and variant selection

The discovery of the RASAL2 variant, followed by its confirmation in a validation cohort, was detailed in our previous study14. Briefly, whole genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on germline genomic DNA from members of a high-cancer-density family. By comparing WGS data from three affected and two unaffected family members, variants present in affected members but absent in unaffected members were identified as potential candidates. After filtering out variants located in non-coding regions, synonymous variants, and those with an allele frequency > 0.05% in any population database, a total of 101 candidate variants were identified. A validation cohort consisting of patients with CRC, breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer was used to examine the distribution of these variants. Among them, CGN c.3560 C > T, RASAL2 c.2423 A > G, and TTLL4 c.1532 C > T were identified as the top three variants with a higher prevalence in cancer patients.

The clinico-genomic database of National Cheng Kung University Hospital (NCKUH) was utilized to investigate the frequency of the RASAL2 variant in cancer patients. This database includes clinical information, germline variants, and somatic mutations of cancer patients at NCKUH. Germline genetic variant data were generated through either WGS or whole exome sequencing using DNA derived from peripheral blood, while somatic mutations were analyzed using deep targeted gene sequencing. As of December 2024, data from 367 patients with CRC, 143 patients with endometrial cancer, and 93 patients with ovarian cancer were available for analysis. WGS data from the Taiwan Biobank28 and data from the 1000 Genomes Project29 were utilized to analyze the prevalence of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant in normal Taiwanese individuals and across different ethnic populations. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of NCKUH (IRB numbers: A-ER-104-153 and A-ER-103-395) and adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

In silico analysis

The Functional Analysis Through Hidden Markov Models - Multiple Kernel Learning (FATHMM-MKL) v2.3, which estimates significance based on various factors including conservation, histone modifications, transcription factor binding sites, and open chromatin30, was utilized to predict the functional impact of the RASAL2 variant in silico. The genomic information of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant, including the chromosome, position, reference base, and mutant base, was submitted to the FATHMM-MKL server (https://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/) to calculate the predictive score, which ranges from 0 to 1. Variants with scores greater than 0.5 are predicted to be pathogenic, while those with scores less than 0.5 are predicted to be benign. Scores near 0 or 1 indicate predictions with the highest confidence. To assess the impact of the RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant on protein stability in silico, DUET, a web server designed to predict the effects of missense mutations was used (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/duet/). The wild-type structure of RASAL2, which was obtained from the UniPort database, was uploaded, and the mutational information of RASAL2 c.2423 A > G (p.D667G with NM_004841 or p.D808G with NM_170692), was submitted. The prediction results provided the change in folding free energy upon mutation was shown in Gibbs Free Energy (ΔΔG). A positive ΔΔG value indicates to a stabilizing mutationm whereas a negative ΔΔG value suggests a destabilizing mutation.

Cell line

Four RAS wild-type colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines, including HT29, LIM1215, SW48, and NCI-H508, were used in this study. HT29 and NCI-H508 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, VA, USA). HT29 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5 A medium (Simply Biotech, CA, USA), while NCI-H508 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM L-Glutamine, 35 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 4.5 g/L D-glucose. LIM1215 cells were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC, Porton Down, UK) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Simply Biotech) supplemented with 2 mM L-Glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 0.6 µg/mL insulin, 1 µg/mL hydrocortisone, and 10 µM 1-thioglycerol. SW48 cells were obtained from the Clinical Research Center of NCKUH and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) (Simply Biotech) with 2 mM L-Glutamine. All culture media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Simply Biotech). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere and were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Chemicals and antibodies

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) recombinant human protein (PHG0313, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Cetuximab, an anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody (A2000, Selleck Chemicals, TX, USA), was obtained from Selleck Chemicals. The antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follows: rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Cell Signaling, 9101), rabbit anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Cell Signaling, 9102), mouse anti-DYKDDDDK tag (Thermo Fisher, MA1-91878), and rabbit anti-β-actin (GeneTex, GTX109639). The antibodies used for immunofluorescent staining included: rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Cell Signaling, 9101), mouse anti-DYKDDDDK tag (Thermo Fisher, MA1-91878), and Hoechst 33,258 (Sigma-Aldrich, 861405). Alexa Fluor 647- (A-21245) and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (A-11004) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Site-directed mutagenesis and plasmid transfection

The RASAL2 plasmid construct pcDNA3.1-RASAL2-DYK (OHu14551) and the empty vector pcDNA3.1-C-(k)DYK were obtained from Genescript Biotech (NJ, USA). The RASAL2 c.2423 A > G variant was generated using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Welgene Biotech, Taipei, Taiwan). Plasmid vectors were prepared using DNA Midiprep Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and the mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Transfections were performed using jetPRIME® Transfection Reagent (Polyplus SA, Illkirch, France). At 24 h post-transfection, stable integration was selected with G418 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and successful transfection was verified by western blot analysis.

Immunoblotting

For immunoblotting, cells were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (9806, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA) to disrupt cellular membranes and release proteins. The lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min to ensure complete lysis. Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and equal amounts of protein were loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels for separation. Subsequently, the proteins were transferred onto Immobilon®-E PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked, incubated with primary antibodies, and washed before being treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immuno Research, PA, USA). Immunoblot bands were visualized using the iBright™ FL1500 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and quantified using ImageJ analysis software.

RAS pulldown assay

For RAS pulldown assay, Active RAS Dectection Kit (8821, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA).) was used. After stimulation with EGF (100 ng/mL) for the indicated times, cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and then lysed with Cell Lysis/Binding/Wash Buffer from Active Ras Detection kit. Lysates were vortexed, incubated for 5 min on ice and subsequently precleared at 16,000 xg for 15 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was measured by using a BCA protein assay kit (Cat. NO. 23225, Thermo Scientific). Lysates were adjusted to 1 mg/mL with Cell Lysis/Binding/Wash Buffer to ensure the equal amount of protein for RAS pull-down. Lysis buffer (100 µL) containing GST-RAF-RBD beads was added to the lysate (130 µL at 1 mg/mL), in a final volume of 230 µL. 90% of the pre-cleared lysates were subsequently added to prewashed glutathione agarose beads from Active Ras Detection kit for 1 h at 4 °C under constant rocking. The beads were subsequently pelleted, washed 3 times with Cell Lysis/Binding/Wash buffer, and eluted for western blotting with 30 µl of 2X reducing sample buffer (1 M dithiothreitol (DTT) to 2X SDS Sample Buffer to a final concentration of 200 mM). Level of GTP-bound RAS was determined by Western blot. GTPγS and GDP were added into the lysates to be used as positive and negative control, respectively.

MTT assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (M2128, Merck Millipore). Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 3.5 × 103 cells per well and allowed to proliferate for 24–72 h. The absorbance at 570 nm, measured using a microplate reader (SpectraMax 340PC384, Molecular Devices, CA, USA), was directly proportional to the number of viable cells. Absorbance values were normalized to Day 0 and across groups at the specified time points.

Immunofluorescence and the FV-3000 confocal microscope

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and then washed 2–3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Blocking was performed with 3% bovine serum albumin (IgG-free, protease-free) (Millipore Sigma, MA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (Abs) diluted in PBS, washed at least three times with PBS containing Tween 20 (PBST), and then incubated with secondary Abs for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were washed at least three more times in PBST after secondary antibody incubation. To visualize the nuclei, Hoechst 33,258 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was applied for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then washed, mounted, and imaged using a scanning confocal microscope (FV-3000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), with the fluorophores excited by lasers at 405, 488, 568, and 647 nm. Image intensity was analyzed using cellSens software (Olympus) to quantify the fluorescence signal intensity from the confocal images.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Group differences were analyzed using the Student’s t-test.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kimforest LTD Taiwan for bioinformatic support.

Author contributions

YMY was responsible for designing the study, conducting the research, analyzing data, interpreting results, preparing figures, and writing the manuscript. YHH was responsible for conducting the study, analyzing data and interpreting results. YTH was responsible for analyzing data, interpreting results, and preparing the figures. PCL, YTH and PYW are responsible for analyzing data and interpreting results. MRS was responsible for designing the study, interpreting results, writing the manuscript, providing the funding and supervising the conduction of whole research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW-114-TDU-B-221-144005) and the National Science and Technology Council (113-2640-B-006-004).

Data availability

The data analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding authr on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Running title

RASAL2 variant mediates anti-EGFR resistance in colorectal cancer.

Word count

3068, 6 figures.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Figures and Figure Legends.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Van Cutsem, E. et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl. J. Med.360, 1408–1417 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douillard, J. Y. et al. Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J. Clin. Oncol.28, 4697–4705 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Fiore, F., Sesboue, R., Michel, P., Sabourin, J. C. & Frebourg, T. Molecular determinants of anti-EGFR sensitivity and resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 103, 1765–1772 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrone, F. et al. PI3KCA/PTEN deregulation contributes to impaired responses to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann. Oncol.20, 84–90 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartore-Bianchi, A. et al. PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with clinical resistance to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res.69, 1851–1857 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sartore-Bianchi, A. et al. HER2 positivity predicts unresponsiveness to EGFR-targeted treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist24, 1395–1402 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raghav, K. et al. MET amplification in metastatic colorectal cancer: an acquired response to EGFR inhibition, not a de Novo phenomenon. Oncotarget7, 54627–54631 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morano, F. et al. Negative hyperselection of patients with RAS and BRAF wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer who received panitumumab-based maintenance therapy. J. Clin. Oncol.37, 3099–3110 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cremolini, C. et al. Negative hyper-selection of metastatic colorectal cancer patients for anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies: the PRESSING case-control study. Ann. Oncol.28, 3009–3014 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bos, J. L., Rehmann, H. & Wittinghofer, A. GEFs and gaps: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell129, 865–877 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou, B., Zhu, W., Jiang, X. & Ren, C. RASAL2 plays inconsistent roles in different cancers. Front. Oncol.9, 1235 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia, Z., Liu, W., Gong, L. & Xiao, Z. Downregulation of RASAL2 promotes the proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells. Oncol. Lett.13, 1379–1385 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, W. et al. IPO5 promotes the proliferation and tumourigenicity of colorectal cancer cells by mediating RASAL2 nuclear transportation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.38, 296 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, Y. T. et al. Tight junction protein cingulin variant is associated with cancer susceptibility by overexpressed IQGAP1 and Rac1-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.43, 65 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, W. & Liu, H. T. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell. Res.12, 9–18 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med.17, 405–424 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith, S. A., French, T. & Hollingsworth, S. J. The impact of germline mutations on targeted therapy. J. Pathol.232, 230–243 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLaughlin, S. K. et al. The RasGAP gene, RASAL2, is a tumor and metastasis suppressor. Cancer Cell.24, 365–378 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wills, C. et al. Germline variation in RASAL2 may predict survival in patients with RAS-activated colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 62, 332–341 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koh, S. B. et al. RASAL2 confers collateral MEK/EGFR dependency in chemoresistant triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.27, 4883–4897 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu, Z. et al. Novel resistance mechanisms to osimertinib analysed by whole-exome sequencing in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Manag Res.13, 2025–2032 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wee, P. & Wang, Z. Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers (Basel). 9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Belli, V. et al. Combined blockade of MEK and PI3KCA as an effective antitumor strategy in HER2 gene amplified human colorectal cancer models. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.38, 236 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song, K. W. et al. RTK-Dependent inducible degradation of mutant PI3Kalpha drives GDC-0077 (Inavolisib) efficacy. Cancer Discov. 12, 204–219 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park, S. M. et al. Systems analysis identifies potential target genes to overcome cetuximab resistance in colorectal cancer cells. FEBS J.286, 1305–1318 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopetz, S. et al. Encorafenib, cetuximab and chemotherapy in BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer: a randomized phase 3 trial. Nat. Med.31, 901–908 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopetz, S. et al. Encorafenib, binimetinib, and cetuximab in BRAF V600E-mutated colorectal cancer. N Engl. J. Med.381, 1632–1643 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan, C. T., Lin, J. C. & Lee, C. H. Taiwan biobank: a project aiming to aid taiwan’s transition into a biomedical Island. Pharmacogenomics9, 235–246 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genomes Project, C. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature526, 68–74 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shihab, H. A. et al. An integrative approach to predicting the functional effects of non-coding and coding sequence variation. Bioinformatics31, 1536–1543 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding authr on reasonable request.