Abstract

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) is one of the most frequently mutated oncogenes in multiple cancers. Multiple types of KRAS mutation are observed in various patients with cancer, and the KRAS(G12D) mutation is the most common. Although multiple covalent inhibitors of the KRAS(G12C) mutation have been identified and clinically validated to date, no drugs have been approved yet for other mutations, including G12D. Herein, we report the discovery and characterization of ASP3082, a KRAS(G12D)-selective degrader, and the crystal structure of the drug-induced ternary complex of KRAS(G12D)/ASP3082/VHL (von Hippel–Lindau). We have also demonstrated an efficient structure-based rational optimization approach, which could be applicable for the optimization of other bifunctional proximity-inducing drugs. ASP3082 effectively induces KRAS(G12D) protein degradation with remarkable selectivity, demonstrates highly efficacious and durable pharmacological activity, and induces tumor regression in multiple KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer xenograft models. Our results suggest that ASP3082 is a potential therapeutic agent for KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer, and is now under clinical investigation.

Subject terms: Structure-based drug design, Pharmacology, Biophysical chemistry, Mechanism of action, X-ray crystallography

KRAS mutations, particularly KRAS(G12D), are prevalent in various cancers, yet effective treatments remain elusive. Here, the authors introduce ASP3082, a pioneering KRAS(G12D)-selective degrader, demonstrating its potent tumor regression capabilities in xenograft models.

Introduction

Rat sarcoma (RAS) proteins are small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) of about 21 kDa that include four isoforms, KRAS4A, KRAS4B, HRAS, and NRAS1. RAS protein is a molecular switch that cycles between the guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound inactive form and guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound active form, and controls downstream signaling1. Following receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) stimulation by growth factors, guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) such as Son of Sevenless (SOS) promote nucleotide exchange of GDP-bound RAS to GTP-bound RAS. GTP-bound RAS interacts with effector proteins, including rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulators (Ral-GDS), and activates downstream signaling pathways, which regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival1,2. In normal cells, GTP-form RAS is regulated by the GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) to hydrolyze GTP, and RAS returns to its inactive GDP form. Thus, the RAS family of proteins controls downstream signaling and plays an important role in cell proliferation.

KRAS mutations are one of the most frequently observed genetic lesions in human cancer, and most KRAS missense mutations are observed at the Gly-12 codon, for example, G12D, G12V, and G12C3,4. These mutations strongly affect the rate of GTP hydrolysis or nucleotide exchange and increase the ratio of GTP-bound KRAS5, leading to constitutive activation of signal transduction. KRAS(G12D) mutation is the most common (29%) in KRAS-mutated cancer and is found in 4.9% of lung adenocarcinoma, 15.0% of colorectal cancer, 39.5% of pancreatic cancer, and in other solid tumors6. Therefore, targeting the KRAS(G12D) mutation is a potential therapeutic approach for multiple major cancer types.

Although direct inhibition of KRAS was historically considered to be difficult due to the lack of clear binding pockets, the discovery of covalent binders to KRAS(G12C) mutants was reported in 2013 and unveiled an allosteric switch-II pocket, which enabled drug discovery for KRAS7. To date, two KRAS(G12C) inhibitors (sotorasib and adagrasib) are approved by the FDA, and several newer KRAS(G12C) inhibitors are undergoing clinical trials8. Since a switch-II pocket is also present in other KRAS mutants, various KRAS mutants might be directly inhibited by targeting this pocket9. Thus, drug discovery for other mutant KRAS forms, including KRAS(G12D), has become more active10–13, and multiple (at least 10) KRAS(G12D) inhibitors, such as MRTX113314,15, HRS-464216, RMC-980517, GFH375/VS-737518, INCB16173419, LY396267320, TSN161121, QLC110122, QTX304623, and AZD002224, have been recently reported and are in clinical studies as of April 2025. We have also been working on KRAS(G12D) inhibitor research since 2014 and have succeeded in obtaining our own binder, but have struggled to sufficiently improve the inhibitory activity. Therefore, we decided to focus on developing protein degraders that could be applied even with low-affinity KRAS binders. We also expected that KRAS degradation might be more advantageous than inhibition due to long-lasting removal of the KRAS mutant from the signaling pathway.

Targeted protein degradation (TPD) is an emerging and attractive technology that has great potential to target traditionally undruggable or hard-to-drug targets in the drug discovery field25,26. Among many TPD technologies, proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are widely employed in recent TPD research27,28. PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules, which consist of a ligand for the protein of interest (POI), a ligand for an E3 ligase, and a linker. PROTAC molecules catalytically induce the formation of a ternary complex with POI/PROTAC/E3 ligase, which leads to ubiquitination of the POI and subsequent protein degradation by the proteasome, and to inhibition of all functions of the target protein. Recently, many PROTAC-type bifunctional degraders have been developed and are being tested in clinical studies29.

In this report, we have successfully tackled drug discovery of a KRAS(G12D) degrader with a structure-based rational optimization strategy. We initially obtained a proprietary KRAS(G12D) binder and then discovered a hit degrader with a short linker. Next, we constructed a ternary complex model of KRAS(G12D)/degrader/VHL for structure model-based rational design, which led to the successful identification of the selective and potent KRAS(G12D) degrader, ASP3082 (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, we have obtained a crystal structure of the ASP3082-induced ternary complex and have fully characterized the pharmacological profile of ASP3082 in various models.

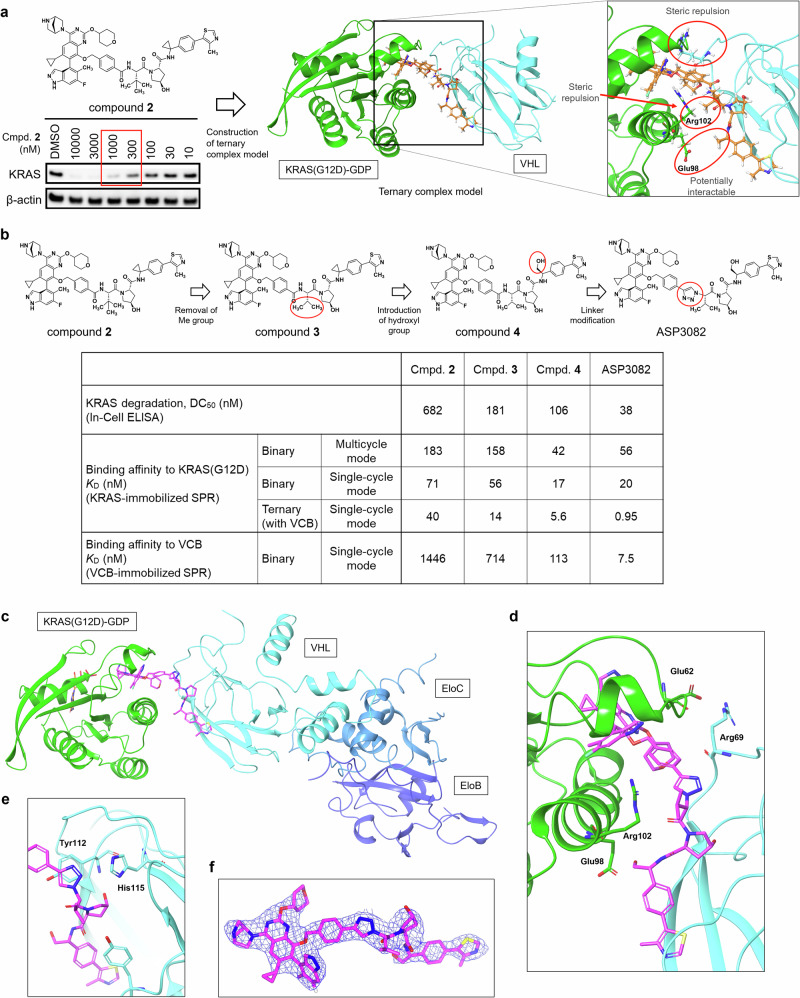

Fig. 1. Discovery of KRAS(G12D) inhibitor and hit degrader.

a Chemical structure of a KRAS(G12D) degrader 2. A constructed ternary complex model of hit degrader 2 in complex with GDP-bound KRAS(G12D) and VHL. Inset on the right shows the interface of the drug-induced ternary complex. b Design and rational optimization of degrader. Relationship of chemical structure, degradation activity (DC50), and binding affinity to KRAS(G12D) or VHL. KRAS degradation activity was assessed by In-Cell ELISA assay in AsPC-1 cells treated with compounds for 24 h. Data are presented as the geometric mean (n = 3). Binding experiments were performed by KRAS(G12D)-immobilized or VHL/ElonginC/ElonginB(VCB)-immobilized SPR assay in multicycle or single-cycle kinetic format. KD values were calculated from fitted kinetic data (KD = kd/ka). Data are presented as the geometric mean (multicycle, n = 5; single-cycle, n = 3). Full details and representative sensorgrams for binary and ternary experiments were shown in Supplementary Fig. 2a, b. X-Ray crystal structure of ternary complex of ASP3082, GDP-bound KRAS(G12D) and VCB (PDB: 9L6F). The ternary complex structure (c), and insets depict interaction between VHL ligand and VHL protein (d), PPI interface of drug-induced ternary complex (e), and the 2Fo – Fc map for the ligand ASP3082 (1.5σ) in mesh (f). For X-ray crystallography data collection and refinement statistics, see Supplementary Table 7.

We have demonstrated that ASP3082 effectively induced KRAS(G12D) degradation with remarkable selectivity over other KRAS variants and more than 9000 non-KRAS proteins. ASP3082 inhibited downstream signaling in the KRAS pathway and cell proliferation in vitro in various KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer cells, and affected the cell proliferations in other KRAS-mutated cells (12D»12C, 12 V > 13D»12 R, WT). We also investigated mechanistic differences between the degrader and the inhibitor and found that our KRAS(G12D) degrader suggested the potential for a more efficient and durable response compared with our KRAS(G12D) inhibitor. We have established an in vivo PK/PD relationship for ASP3082 and confirmed sustained concentration and durable PD effects in tumors. ASP3082 showed potent anti-tumor activity and achieved tumor regression in multiple KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer xenograft models with once- or twice-weekly intravenous dosing. Taken together, our data indicates that ASP3082 displays therapeutic potential for KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer.

Results

Acquisition of KRAS(G12D) binder and bi-functional KRAS(G12D) hit degrader

PROTAC-type bifunctional degraders require a ligand for the POI, a ligand for the E3 ligase, and a linker, but we did not have a suitable binder for KRAS(G12D) at the beginning of our research. Therefore, we initially identified a proprietary KRAS(G12D) binder 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1a) by structure-based design from our KRAS(G12C) binder ASP245330, which has a quinazoline core similar to ARS-162031, and screening of compounds that bind to GDP-bound KRAS(G12D). We also solved a crystal structure of GDP-bound KRAS(G12D) in a complex with compound 1 (PDB code: 9L6A) and found that the bridged amine interacts with the Asp12 residue of the KRAS(G12D) protein (Supplementary Fig. 1a, distance between nitrogen and oxygen is 2.78 Å.).

Having a proprietary KRAS(G12D) binder in hand, we next explored bifunctional degraders. To acquire hit degraders that form a ternary complex with an appropriate E3 ligase, we first tried a variety of E3 ligands and linkers. Concerning linker selection, we mainly selected short linkers since linker attachment sites of our KRAS(G12D) binder 1 are exposed to the solvent region (Supplementary Fig. 1b). We therefore expected that short linkers should be sufficient to afford drug-like degraders.

Based on this strategy, we designed and synthesized a bifunctional degrader library (ca. 30 compounds) using our proprietary KRAS(G12D) binder 1 and various E3 binders and linkers. As a result of KRAS degradation assay, we were fortunate to find that compound 2, which employs VHL as the E3 ligase, exhibited moderate KRAS(G12D) degradation activity by immunoblot analysis using KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer cells (AsPC-1) after 24-h treatment (Fig. 1a). Although the effective concentration of degradation activity was moderate (~1 μM), we had successfully identified a drug-like hit degrader 2 with a very short linker moiety.

Construction of a ternary complex model using the hit degrader

For structure-based rational optimization of hit degrader 2, we first attempted to obtain structural information of the ternary complex. Since we were unable to obtain crystals of the ternary complex of KRAS(G12D)/degrader 2/VHL, we examined the in-silico construction of a ternary complex model. In general, constructing ternary complex models with flexible compounds having long linkers is highly problematic because such compounds have many possible conformations.

However, our degrader 2 with a short linker has fewer conformations, and we were readily able to create a plausible ternary complex model. We first calculated the conformations with regard to the linker part, as indicated single bond in Supplementary Fig. 1c, of compound 2 (each ligand part was fixed to the conformation of the crystal structure), and generated 20 conformations using the molecular modeling software Maestro32. Next, we constructed ternary complex models using Maestro by superimposing each ligand with the crystal structures of KRAS(G12D) with compound 1 (PDB code: 9L6A) and VHL/EloC/EloB (VCB) with VH032, a known VHL binder commonly used in bifunctional degraders, (PDB code: 4W9H)33, and selected the most plausible ternary complex model, which has one of the most stable conformations with the least collisions between proteins (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Our derived structural model suggested the following several points for improvement of ternary complex formation (Fig. 1a): 1) the tert-butyl group of the VHL ligand is too close to the KRAS(G12D) protein (leading to steric repulsion); 2) a polar residue of the KRAS(G12D) protein is present in the vicinity of the cyclopropyl group of the VHL ligand (possibility of acquiring a new interaction); and 3) the two proteins are partly interacting (potential for steric repulsion). Based on our analysis, we decided to: 1) remove the methyl group from the VHL ligand (convert tert-butyl into isopropyl group); 2) introduce a hydroxyl group to the VHL ligand (convert cyclopropyl into a hydroxymethyl group); and 3) adjust the angle and the length of the linker to avoid the steric repulsion at the protein-protein interaction (PPI) interfaces.

Rapid and rational optimization of the hit degrader using the ternary complex model

Based on analysis of our ternary complex model, we first removed a methyl group from the VHL ligand of degrader 2 in anticipation of improving the stability of the ternary complex. As a result, we found that the degradation activity of modified degrader 3 (DC50 of 181 nM (95% Confidence Intervals (CI), 64–512 nM)) had a dramatic 3–4 fold improvement from degrader 2 (DC50 of 682 nM (95% CI, 131–3563 nM)) as anticipated (Fig. 1b). We also assessed the binary affinity of degraders to GDP-bound KRAS(G12D) or VCB, and the ternary affinity to GDP-bound KRAS(G12D) with VCB by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay, and found that degrader 3 showed better ternary affinity with KD of 14 nM (95% CI, 1.5–137 nM; maximum analyte response (Rmax), 880 RU) compared with degrader 2 with KD of 40 nM (95% CI, 24–66 nM; Rmax, 214 RU), whereas the binary affinity to KRAS(G12D) or VCB was comparable to degrader 2 (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 2a, 2b). KRAS(G12D)-RAF PPI inhibitory activity by cell-free TR-FRET assay showed similar results (Supplementary Fig. 3), and it is worth noting that this modification had little effect on binary affinity for each protein but had a large effect on ternary complex formation.

We next converted the cyclopropyl group of the VHL ligand (degrader 3) to a hydroxymethyl group (degrader 4), expecting to acquire new interactions between the VHL ligand and the KRAS(G12D) protein. Modified degrader 4 showed a 3–4 fold better binary affinity (multicycle mode) to KRAS(G12D) with KD of 42 nM (95% CI, 28–63 nM) compared with degrader 3 with KD of 158 nM (95% CI, 117–214 nM), and binary affinity (single-cycle mode) to VCB with KD of 113 nM (95% CI, 75–169 nM) compared with degrader 3 with KD of 714 nM (95% CI, 261–1958 nM), and slightly better degradation activity with DC50 of 106 nM (95% CI, 28–394 nM) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 2a, 2b). Multicycle mode is the classical standard approach, but cannot be used when it is difficult to find suitable regeneration conditions. In the evaluation of the binary binding to VCB and the ternary binding to KRAS(G12D) with VCB, the compound dissociation rate was slow, making it difficult to examine the regeneration conditions; therefore, measurements were taken in single-cycle mode.

We further investigated modification of the linker to adjust the PPI interfaces between KRAS(G12D) and VHL. We modified the amide moiety in the linker of degrader 4 into other structures to fine-tune the angle and length, and found that the modified degrader ASP3082, which has a triazole ring as a linker, exhibits improved degradation activity with a DC50 of 38 nM (95% CI, 14–108 nM; Fig. 1b). Although the binary affinity of ASP3082 to KRAS(G12D) was slightly reduced (KD of 56 nM (95% CI, 39–81 nM)), ASP3082 showed strong binary binding to VHL with KD of 7.5 nM (95% CI, 3.5–16 nM) and slow dissociation with a dissociation rate constant (kd) of 2.1 × 10−3 s−1 (95% CI, 1.6–2.7 × 10−3 s−1) (Supplementary Fig. 2b), and ternary binding with KD value of 0.95 nM (95% CI, 0.61–1.5 nM) and kd of 4.4 × 10−4 s−1 (95% CI, 1.6–12 × 10−4 s−1) in KRAS(G12D)-immobilized SPR assay with VCB (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Importantly, we successfully obtained a crystal structure of the ternary complex of KRAS(G12D)/ASP3082/VCB (PDB code: 9L6F, Figs. 1c–f). According to the crystal structure, the Arg102 residue of KRAS(G12D) and the isopropyl group of VHL ligand are located close together, suggesting that the introduction of a tert-butyl group instead of an isopropyl group at that position may increase steric repulsion, and the Glu98 residue of KRAS(G12D) and the hydroxyl group of the VHL ligand are in a position where they can interact (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, KRAS(G12D) and VHL proteins are thought to form stable PPIs by interaction between Glu62 of KRAS(G12D) and Arg69 of VHL (Fig. 1d).

In addition, focusing on the vicinity of the triazole group of ASP3082, the triazole seems to interact with His115 of the VHL protein and forms a pi–pi interaction with Tyr112 of VHL protein, leading to strong binding and slow dissociation34,35 (Fig. 1e). Collectively, we demonstrated rational optimization of a degrader using ternary complex structure-based design, and successfully obtained the potent KRAS(G12D) degrader ASP3082.

ASP3082 induces selective KRAS(G12D) degradation and demonstrates inhibition of KRAS-dependent signaling

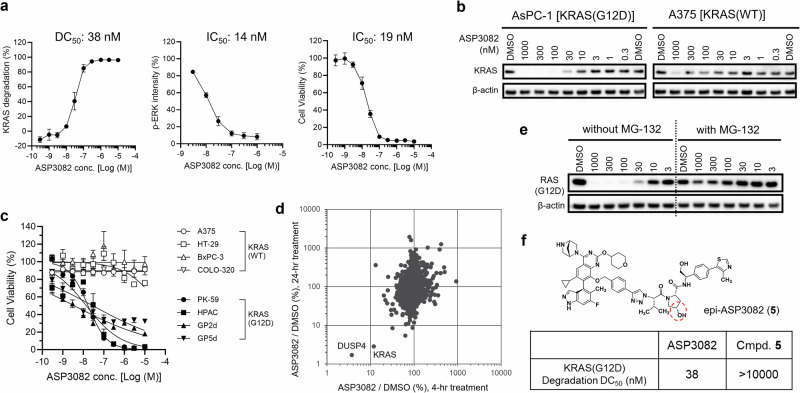

Next, we investigated inhibitory activity on KRAS downstream signaling and cell proliferation using pancreatic cancer cells (AsPC-1) harboring the KRAS(G12D) mutation. ASP3082 significantly inhibited ERK phosphorylation with IC50 of 14 nM (95% CI, 8–23 nM) and cell proliferation with IC50 of 19 nM (95% CI, 13–30 nM) (Fig. 2a). Also, we assessed the selectivity of KRAS(G12D) degradation over KRAS(WT). While KRAS(G12D) degradation was observed in KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer cells (AsPC-1, HPAC, and PK-59), partial degradation of KRAS(WT) in A375 (malignant melanoma) was observed only at higher concentrations (1 μM), probably due to lower binary binding ability to KRAS(WT) with IC50 of >10 μM in KRAS-RAF PPI inhibition assay (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 2. ASP3082 demonstrates selective degradation of KRAS(G12D) via VHL-mediated proteasomal degradation and inhibits KRAS signaling pathway.

a KRAS degradation and p-ERK inhibitory activity using In-Cell ELISA assay (24 h treatment) and cell viability using CellTiter-Glo assay (6 days treatment) of ASP3082 in AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cells harboring KRAS(G12D) mutation. Fluorescence signals of KRAS were normalized with that of β-actin for each well, and the KRAS degradation activity was converted to a percentage, where 0% is defined by average intensity of the DMSO-treated group, and 100% is defined by that of the treatment without anti-RAS(G12D) antibody staining. Fluorescence signals of p-ERK were quantified, and p-ERK levels were converted to a percentage, where 100% is defined by DMSO treatment, and 0% is defined by 1 μM trametinib treatment. Cell viability of AsPC-1 cells treated with ASP3082 was normalized as 100% (average luminescence intensity with DMSO treatment) and 0% (average luminescence intensity without cells). Each point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). b KRAS degradation activity of ASP3082 in human cancer cell lines. Immunoblot analysis of cancer cell lines treated with the indicated concentrations of ASP3082 or DMSO as a control for 24 h was performed. c Cell viability of human cancer cells with KRAS(G12D) mutation (black) and wild-type (WT) KRAS (white) treated with ASP3082 for 6 days using round-bottom white plates. Cell viability was normalized as 100% (DMSO) and 0% (average luminescence intensity without cells). Each point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 1, quadruplicate). d Multiplexed quantitative proteomics analysis of ASP3082. Scatter plots for individual protein ratio of 1 μM ASP3082 versus DMSO-treated AsPC-1 cells for 4 h and 24 h treatment. Both vertical and horizontal axes are expressed as a percentage. e Proteasome-dependent KRAS degradation by ASP3082. Immunoblot analysis of AsPC-1 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of ASP3082 or DMSO as a control for 24 h was performed. Proteasome inhibitor MG-132 was pre-treated with 10 μM for 1 h prior to ASP3082 or DMSO treatment. f VHL-mediated KRAS degradation by ASP3082. KRAS(G12D) degradation in AsPC-1 cells treated with ASP3082 or compound 5 (structure shown) for 24 h was examined by In-Cell ELISA assay. Data are presented as the geometric mean (n = 3).

Subsequently, we evaluated the inhibitory activity of ASP3082 on cell viability of various KRAS(G12D)-mutated and KRAS(WT) cancer cells (Fig. 2c). The effects of ASP3082 on viability of KRAS(WT) cancer cell lines, A375, HT-29 (colorectal), BxPC-3 (pancreatic) and COLO-320 (colorectal), were observed only at higher concentrations (IC50 values were >10 μM) in 3D assay format (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 4c). In contrast, ASP3082 exhibited a wide range of growth-inhibitory effects against various KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer cell lines, PK-59 (pancreatic), HPAC (pancreatic), GP2d (colorectal) and GP5d (colorectal), with IC50 values ranging from 3.6 to 29 nM. Furthermore, we investigated the selectivity against RAS mutants other than KRAS(G12D), and found that growth inhibitory activities on cell lines harboring KRAS mutations (G12V, G12C, G12R and G13D), HRAS(G12V), and NRAS(Q61K) were weak to moderate (Supplementary Fig. 4d). The order of response for different mutations is as follows (12D»12 C, 12 V > 13D»12 R, WT). These data demonstrated that ASP3082 selectively degrades KRAS(G12D) and inhibits KRAS-dependent signaling and survival in KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer cell lines.

We then evaluated the selectivity of degradation activity over proteins other than KRAS(G12D) by proteomics analysis. AsPC-1 cells were treated with ASP3082, and proteomic analysis was performed at 4 and 24 h; selective reduction of KRAS(G12D) and dual specificity protein phosphatase 4 (DUSP4), a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent gene, was observed (Fig. 2d). Since DUSP4 is regulated by p-ERK and is known to be down-regulated by KRAS inhibitors or other MAPK-pathway inhibitors36,37, we assumed that the reduction of DUSP4 is not direct degradation by ASP3082. This result indicates that the degradation activity of ASP3082 is highly selective for KRAS(G12D) over 9000 proteins in AsPC-1 cells.

We also investigated the mechanism of KRAS degradation by ASP3082. First, to confirm that the KRAS(G12D) protein is degraded by the proteasome, we tested whether the degradation is inhibited by the addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG-132. While KRAS(G12D) degradation was induced by ASP3082 without MG-132, it was almost completely rescued by adding 10 μM MG-132 (Fig. 2e), indicating that ASP3082-induced KRAS(G12D) degradation is mediated by a proteasome-related pathway. Next, to confirm that ASP3082-induced KRAS(G12D) degradation is mediated by VHL, we performed two experiments. The first was evaluation using epi-ASP3082 (5, Fig. 2f), which is an epimer of ASP3082 regarding the VHL ligand and does not bind to VHL, and the other was evaluation under VHL-knockdown conditions using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). First, we observed that epi-ASP3082 (5) did not induce KRAS(G12D) degradation in contrast to ASP3082 (Fig. 2f), because epi-ASP3082 did not bind to VHL (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and did not induce PPI between KRAS(G12D) and VHL (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Second, we confirmed that the KRAS(G12D) degradation activity of ASP3082 was partially suppressed under VHL-knockdown conditions using siRNAs in PK-59 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Since VHL knock-down efficiency by siRNAs in AsPC-1 cells was insufficient, PK-59 cells were used in this experiment. Collectively, these results indicated that ASP3082-induced KRAS(G12D) degradation is mediated by VHL and the proteasome.

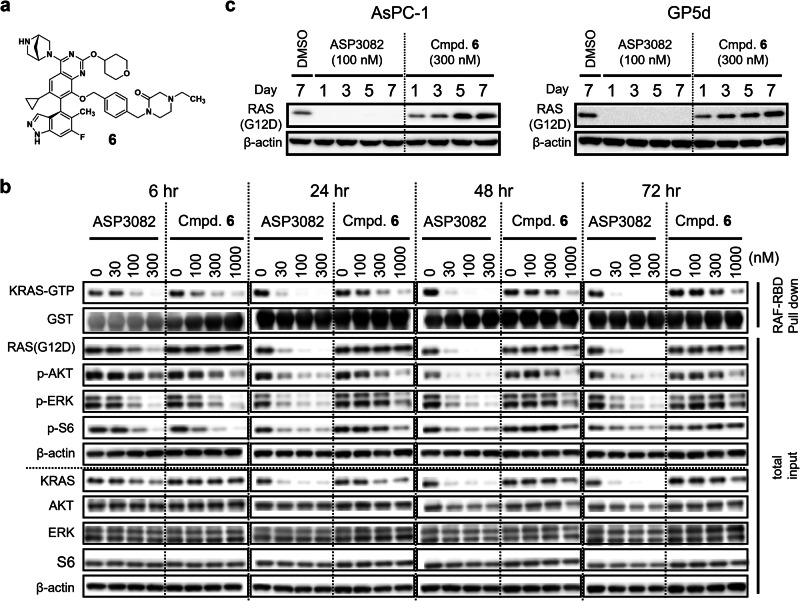

ASP3082 demonstrates durable inhibition of KRAS-dependent signaling

To determine if the KRAS(G12D) degrader has any features compared to inhibitors, we verified the difference in mechanism between ASP3082 and our GDP-bound (off-state) KRAS(G12D) inhibitor 6 (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 5a) in AsPC-1 cells. We first considered using epi-ASP3082 (5), which has no KRAS(G12D) degradation activity, as an inhibitor. However, since epi-ASP3082 has a very weak inhibitory effect on KRAS(G12D) (Supplementary Figs. 2a and 3), we selected compound 6, which has stronger KRAS inhibitory activity (Supplementary Fig. 5a), for evaluation. We evaluated the influence of the KRAS(G12D) degrader and inhibitor on KRAS signaling using AsPC-1 cells. AsPC-1 cells were treated with inhibitor 6 or degrader ASP3082, and expression levels of proteins were evaluated at various time points (Fig. 3b). Inhibitor 6 suppressed the formation of GTP-bound KRAS(G12D) and inhibited the KRAS signaling pathway (p-ERK, p-AKT, and p-S6) at 6 h; however, an increase in GTP-bound KRAS(G12D), p-ERK, p-AKT, and p-S6, was observed at 24, 48, and 72 h. Reactivation was evident at prolonged treatment time points, suggesting the involvement of time-dependent feedback reactivation pathways in AsPC-1 cells. Treatment with the KRAS(G12D) inhibitor 6 led to reactivation of the RAS-MAPK pathway, as evidenced by increased levels of GTP-bound KRAS and p-ERK. A similar adaptive response has been reported with the KRAS(G12D) inhibitor MRTX1133, where relief of feedback inhibition on receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), including EGFR, results in compensatory activation of wild-type RAS isoforms and reactivation of downstream signaling38. These findings suggest that RTK-mediated feedback reactivation is a common mechanism limiting the durability of KRAS(G12D) inhibitors. In contrast, KRAS(G12D) degrader ASP3082 showed durable KRAS(G12D) degradation, including GTP-bound KRAS(G12D) after 24 h, and clearly reduced the protein levels of p-ERK, p-AKT, and p-S6. Moreover, it was found that these protein levels continued to be suppressed even after 72 h. These results revealed that ASP3082-induced KRAS(G12D) degradation could suppress the reactivation of the RAS-MAPK signaling pathway that was observed with the inhibitor.

Fig. 3. Mechanistic differences between KRAS(G12D) degrader ASP3082 and inhibitor 6.

a Chemical structure of our inhibitor (Cmpd. 6). b Effects of KRAS(G12D) degrader ASP3082 or inhibitor 6 on active KRAS (GTP-form) and its downstream signaling. Immunoblot analysis of AsPC-1 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of ASP3082 or compound 6 for the indicated time points was performed. Compound 6 used in this study is hydrochloride salt. c Effects of KRAS(G12D) degrader ASP3082 or inhibitor 6 on total RAS(G12D) protein expression. Immunoblot analysis of G12D-mutated cancer cell lines treated with ASP3082 or compound 6 for the indicated days was performed. Compounds were added only on day 0 and maintained in the cell cultures.

Furthermore, KRAS(G12D) inhibitor 6 induced a time-dependent increase in KRAS protein levels in multiple cancer cell lines harboring the KRAS(G12D) mutation such as AsPC-1, PK-59, HPAC, KP-4 (pancreatic), GP5d, and GP2d (colorectal), while ASP3082 reduced KRAS protein levels, with the reduction maintained for up to 7 days (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 5b). This upregulation is reminiscent of resistance mechanisms reported for KRAS(G12C) inhibitors, where amplification of the mutant KRAS allele has been identified as a key driver of acquired resistance39,40. These findings raise the possibility that a similar gene amplification event may be occurring under KRAS(G12D) inhibitor pressure, contributing to increased KRAS protein and potential drug resistance. Taken together, these results suggested that ASP3082, as a KRAS(G12D) degrader, displays a differentiated mechanism of action with potential for more efficient and durable response compared with inhibitors of GDP-bound KRAS(G12D) and may overcome such resistance mechanisms of KRAS(G12D) inhibitors by degrading the amplified KRAS protein.

ASP3082 demonstrates anti-tumor effect in vivo and achieves tumor regression in xenograft models

Next, in vivo studies were conducted to examine the anti-tumor activity of ASP3082 in subcutaneous cell-line derived xenograft (CDX) mouse models using KRAS(G12D)-mutated pancreatic cancer PK-59 cells. We first evaluated the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) profiles of ASP3082 after single-dose administration to understand the relationship between drug exposure and KRAS(G12D) protein degradation. ASP3082 was administered intravenously at two doses (10 and 30 mg kg−1), and we determined the compound concentrations in plasma and tumor (Fig. 4a), as well as the KRAS(G12D) protein levels in tumor at various time points (2 to 144 h) (Fig. 4b). Maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and area under the concentration–time curve from time of dosing up to the time of the last measurable concentration (AUCt) values of ASP3082 in plasma and tumors increased with an increased dose. Importantly, while the concentrations in plasma decreased rapidly after administration, concentrations in tumors were maintained at a certain level up to 144 h (Fig. 4a). Since KRAS(G12D) protein is expressed only within the xenograft tumors, it is speculated that ASP3082 binds strongly to the KRAS(G12D) protein only within the tumors and remains there for a long time. We also confirmed that the concentration of the compound rapidly decreases in normal pancreatic tissues, similar to that observed in plasma (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. PK/PD relationship and anti-tumor activity of selective KRAS(G12D) degrader ASP3082 in CDX model.

a Pharmacokinetics profiles of ASP3082. Plasma, intratumor and pancreas concentration of ASP3082 after a single intravenous administration of ASP3082 in PK-59 pancreatic cancer xenograft model harboring the KRAS(G12D) mutation. Dotted line in plasma concentration represents in vitro DC50 value of ASP3082 (38 nM, shown in Fig. 2a). Each data point represents the mean ± SD (n = 3). b Pharmacodynamics profile of ASP3082. Immunoblot analysis of PK-59 xenograft tumors treated with ASP3082 or the vehicle for the indicated hours was performed. KRAS(G12D) band intensities were divided by β-actin band intensities for normalization, and relative KRAS(G12D) protein levels were quantified by comparing to the average of vehicle samples for each time point. Each bar represents the mean value of KRAS(G12D) degradation and SEM (n = 3 per time point). c Anti-tumor activity of ASP3082 in a CDX (PK-59) model. Mice were treated with the vehicle or ASP3082 on days 1, 8, and 14. Tumor sizes and body weights were measured twice weekly until day 21. Dotted line represents the mean tumor volume of all groups at day 0. Statistical analysis of tumor sizes was performed for the values on day 21. **P < 0.01 compared with the value of the vehicle group on day 21 (Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). Each point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 5). d Changes of gene expression by ASP3082. qPCR analysis of PK-59 xenograft tumors treated with ASP3082 or the vehicle for the indicated hours was performed. Each gene expression was divided by beta-2-microglobulin gene expression for normalization, and each relative gene expression was quantified by comparing to the average of vehicle samples for each time point. Each bar represents the mean value of each gene expression and SEM (n = 3 per time point, except 48 and 144 h of 30 mg kg−1 group (n = 2)). CDX, cell-line derived xenograft.

Moreover, we conducted immunoblot analyses to assess the changes of KRAS(G12D) protein level in tumors as a PD marker (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 6). After a single-dose intravenous administration of ASP3082, degradation of KRAS(G12D) protein was observed in a dose-dependent manner. Maximum degradation was observed at 1 day (24 h) after administration (82% degradation at 10 mg kg−1, and 93% degradation at 30 mg kg−1), and certain levels of degradation were sustained for at least another 2 days (48 h). It was found that about 50% of the degradation (35% degradation at 10 mg kg−1, and 63% degradation at 30 mg kg−1) was maintained even after 6 days (144 h) compared with the vehicle group. Furthermore, protein levels of p-ERK and DUSP4 were also clearly decreased, and induction of cleaved caspase 3 was observed, especially at 24 h after administration (Supplementary Fig. 6). Collectively, we have established a PK/PD relationship for ASP3082 in this CDX model.

Based on the above results, we decided to conduct anti-tumor studies with once-weekly dosing. ASP3082 was administered by intravenous injection once weekly at dose levels ranging from 0.3 to 30 mg kg−1. Distinct dose-dependent anti-tumor activity was observed by treatment of ASP3082 compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 4c). Notably, tumor regression was observed at 10 and 30 mg kg−1 by 18% and 63% on day 21, respectively. Even at 30 mg kg−1, the highest dose in this study, ASP3082 was well tolerated in mice without body weight loss or other overt toxicity (data not shown). To further investigate the mechanisms of anti-tumor effects, we assessed the changes of gene expression in tumors at various time points (2 to 144 h) by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) experiments (Fig. 4d). We observed an evident reduction of expression of MAPK-dependent genes36,41, such as DUSP4, DUSP6, ETS translocation variant 4 (ETV4), FOS Like 1 (FOSL1), and protein sprouty homolog 4 (SPRY4); this reduction was sustained for several days. Since the KRAS(G12D) inhibitor MRTX1133 had reported to downregulate the MYC gene15, we also investigated the effect of KRAS degradation on the MYC gene and observed time-dependent partial reduction of MYC. Taken together, we confirmed that ASP3082 effectively degraded KRAS(G12D) and inhibited KRAS downstream signaling, including expression of MAPK-dependent genes, and achieved efficacious anti-tumor activity in vivo.

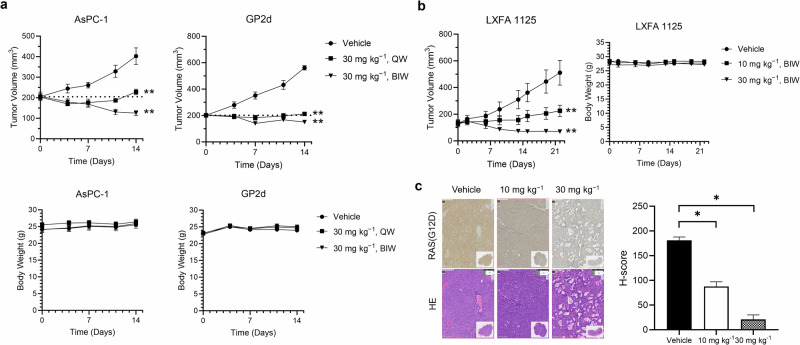

ASP3082 exhibits anti-tumor activity in various cancer xenograft models in mice

To further assess the anti-tumor activity of ASP3082, we also examined other pancreatic and colorectal CDX or lung PDX models harboring the KRAS(G12D) mutation in mice by once or twice weekly dosing. ASP3082 demonstrated almost complete tumor growth inhibition by 30 mg kg−1 once weekly dosing, and tumor regression by 30 mg kg−1 twice weekly dosing in the AsPC-1 and GP2d cancer xenograft models (Fig. 5a). Anti-tumor activity was also confirmed in other xenograft models using PK-1, HPAC, KP-4, and GP5d cells (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Almost complete tumor inhibition was observed in these models by 30 mg kg−1 twice weekly dosing. In the LXFA 1125 (genetic alterations: KRAS, PIK3R1, TP53) and LXFA 2204 (genetic alterations: KRAS, FGFR3, TP53) lung PDX models, ASP3082 exhibited tumor growth inhibition at 10 mg kg−1 twice weekly dosing and tumor regression at 30 mg kg−1 twice weekly dosing (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 7c). In addition, tumor samples were harvested at the endpoint (24 h or 3 days after final dosing) and analyzed by immunohistochemistry to assess the expression levels of KRAS(G12D) protein. We observed a clear reduction of KRAS(G12D) protein in the tumors from ASP3082-treated mice (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 7d).

Fig. 5. Anti-tumor activity of selective KRAS(G12D) degrader ASP3082.

a Anti-tumor activity of ASP3082 in CDX (AsPC-1 and GP2d) models. Mice were treated intravenously with the vehicle or ASP3082 (30 mg kg−1) on the following schedule. In the ASP3082 once-weekly group, ASP3082 was administered on days 1 and 8, and the vehicle was administered on days 5 and 12. In the ASP3082 twice-weekly or vehicle group, ASP3082 or the vehicle was administered on days 1, 5, 8, and 12, respectively. Tumor sizes and body weights were measured twice weekly until day 14. Dotted line represents the mean tumor volume of all groups at day 0. Statistical analysis of tumor sizes was performed for the values on day 14. **P < 0.01 compared with the value of the vehicle group on day 14 (Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). Each point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 5). b Anti-tumor activity of ASP3082 in a NSCLC PDX (LXFA1125) model. Mice were treated intravenously with the vehicle or ASP3082 on days 1, 5, 8, 12, 15, and 19. Tumor sizes and body weights were measured twice weekly until day 22. Statistical analysis of tumor sizes was performed for the values on day 22. **P < 0.01 compared with the value of the vehicle-treated group on day 22 (Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). Each point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 8). c Immunohistochemical staining with anti-RAS(G12D) antibody or Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) in the tumors harvested from the vehicle or ASP3082-treated mice (LXFA 1125 PDX model) 3 days after the last dose of ASP3082. (Left) Representative immunohistochemistry images of tumor sections from each treatment group. (Right) H-score of each treatment group. Statistical analysis was performed for the values on day 22. *P < 0.05 compared with the value of the vehicle-treated group on day 22 (Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). Each bar represents the mean value + SEM (n = 8). The H-score is calculated as follows: (1 × percentage of weak staining) + (2 × percentage of moderate staining) + (3 × percentage of strong staining) within the target region, ranging from 0 to 300. NSCLC Non-small cell lung cancer, PDX Patient-derived xenograft, QW Once-weekly, BIW Twice-weekly.

In contrast, ASP3082 did not inhibit tumor growth in the KRAS(WT) xenograft models (A375 and HT-29) at 30 mg kg−1 once daily subcutaneous (sc) dosing while ASP3082 showed anti-tumor activity in the KRAS(G12D) xenograft model (PK-59) by sc dosing (Supplementary Fig. 7b). These comparative studies were performed using sc administration, which is expected to maintain blood concentrations, before the sustained efficacy of intravenous administration was confirmed. These results show that ASP3082 selectively degrades KRAS(G12D) over KRAS(WT) and exhibits anti-tumor activity in vivo, consistent with our in vitro data. Overall, ASP3082 treatment was well tolerated in mice and efficacious in various KRAS(G12D)-mutated tumor xenograft models.

Discussion

KRAS is one of the most frequently mutated oncogenes, and multiple types of KRAS mutations are observed in various patients with cancer. KRAS(G12C) inhibitors were approved by the FDA, and drug discovery activities for other KRAS mutants have become very active. Regarding KRAS(G12D) research, multiple KRAS(G12D) inhibitors and pan-KRAS inhibitors have been reported and are under clinical investigation12,13, including small molecules that bind to a switch-II pocket14–16,18–24,42, a cyclic peptide that binds to GDP-bound KRAS43, and macrocyclic molecules that bind to GTP-bound KRAS and cyclophilin to form ternary complexes17,44,45. While multiple KRAS inhibitors are currently being tested in clinical trials, ASP3082 is the only KRAS degrader in a clinical trial as of April 2025. Herein, we report the first clinical KRAS(G12D) degrader, ASP3082 (NCT05382559).

In this report, we initially obtained KRAS(G12D) binders targeting a switch-II pocket and then explored degraders. Our quinazoline-based KRAS(G12D) binder has two linker attachment sites, Exit a and b (Supplementary Fig 1b); one (Exit a) is also used in a previously reported KRAS(G12C) degrader46, and the other (Exit b) is unique to our KRAS binder. While the known linker attachment site (Exit a) did not yield effective degraders, we succeeded in obtaining potent degraders using our proprietary linker attachment site (Exit b). It has been reported that differences in the linker attachment site have a large effect on the orientation of the two proteins that are desired to be brought together, and influence whether they can form a ternary complex47. Our KRAS(G12D) binder with a proprietary linker attachment site afforded degraders that enabled the formation of a ternary complex on a compatible PPI surface.

We obtained the hit degrader 2 with a short linker and then constructed a ternary complex model of KRAS(G12D)/degrader 2/VHL for structure-based rational optimization. Although there are some successful examples of PROTAC design using ternary complex structure even for PROTACs with a flexible linker48–50, it is generally difficult to obtain ternary complex structure models with flexible PROTACs. In contrast, since our hit degrader 2 with a short linker has limited conformations, we could construct a plausible ternary complex model by our modeling method based on the degrader’s conformation (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1c).

We attempted to optimize degrader 2 to improve the ternary complex based on the points for improvement suggested by the constructed model. Our ternary structure-based optimization approach efficiently improved the stability of the degrader-induced ternary complex as well as degradation activity, leading to the discovery of a potent KRAS(G12D) degrader ASP3082. Notably, modifications of the VHL ligand of degrader 2 contributed to the stabilization of the ternary complex. Removal of the methyl group located at the PPI interface had a large effect on the stabilization of the ternary complex, despite little effect on binary affinity for each protein (degrader 2 to 3); the introduction of a hydroxyl group to VHL ligand affected its binding to the KRAS(G12D) protein and improved the ternary complex (degrader 3 to 4). These SARs are unique to bifunctional degraders as PPI stabilizers.

By further optimization, we have achieved the discovery of a potent KRAS(G12D) degrader, ASP3082, by modifying the linker moiety based on the ternary structure model. We solved the crystal structure of the KRAS(G12D)/ASP3082/VCB ternary complex and identified a key interaction between KRAS(G12D) and VHL. The crystal structure suggested that the triazole group in the VHL ligand of ASP3082 strongly interacts with VHL, contributing to the improved stability of the ternary complex and resulting in KRAS(G12D) degradation activity. Recently, a pan-KRAS degrader, ACBI3, that contains a triazole ring in the VHL ligand has been reported35, and similar to our findings, the triazole group in the VHL ligand of ACBI3 strongly interacts with VHL. Overall, our successful optimization indicates that the ternary complex structure-based design has great potential to enable rapid optimization of bifunctional degraders and other proximity-inducing drugs.

ASP3082 showed potent KRAS(G12D) degradation activity with selectivity over other KRAS variants, such as KRAS(WT) and KRAS(G12V), as well as more than 9000 non-KRAS proteins in cells. We also investigated the mechanistic differences between degraders and inhibitors. ASP3082, as a degrader, demonstrated an efficient and durable response, including the reduction of GTP-bound KRAS, p-ERK, p-AKT, and p-S6, compared with our GDP-bound KRAS(G12D) inhibitor in AsPC-1 cells.

We further examined in vivo anti-tumor studies in xenograft models to evaluate the therapeutic potential of ASP3082. We established an in vivo PK/PD relationship for ASP3082 and confirmed the sustained concentration in tumors and durable PD effects. PK evaluation showed that the compound concentration in the tumor tissue was maintained to a certain extent (Fig. 4a), but the concentrations decreased 2- to 3-fold within 24 h after administration. The RAS and p-ERK levels in the tumors were restored at 144 h (6 days), suggesting that the compound concentration in the cancer cells may have been limited and insufficient.

We also evaluated in vitro plasma protein binding in mice to understand the PK/PD relationship, and the mean unbound fraction ratio of ASP3082 at 10, 50, and 200 µg mL−1 was determined to be 0.00784 by using the ultracentrifugation method. Considering this unbound fraction ratio, it seemed that the unbound compound concentration in the tumor did not reach the effective level at all, making it difficult to clearly explain the PK/PD relationship. Some bifunctional degraders, including ASP3082, often exhibit relatively low membrane permeability, low solubility, and high lipophilicity, which could be caused by non-specific binding in in vitro assay, and the values of cellular potency tend to be “apparent”51,52. Therefore, it is not easy to estimate the actual effective concentration in cells. Collectively, we think that it was difficult to clearly explain the PK/PD relationship from only the “apparent” in vitro cellular potency and the data on total exposure and plasma protein binding. To analyze the PK/PD relationship more precisely, further studies are required. Overall, ASP3082 exhibited anti-tumor activity and achieved tumor regression in several KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer xenograft models by once- or twice-weekly intravenous dosing.

In summary, we identified a highly potent and selective KRAS(G12D) degrader, ASP3082, that elicits potent anti-tumor activity in various preclinical models using KRAS(G12D)-mutated cancer cells. Our data shows that ASP3082 treatment is well-tolerated and efficacious in mice CDX and PDX models, and the results suggest that ASP3082 has the potential to be an effective anti-tumor agent in clinical studies. Our discovery of ASP3082 indicates that TPD technology is applicable and attractive for targeting difficult-to-drug targets.

Online content

Methods, acknowledgements, Nature Research reporting summaries, Supplementary information, Supplementary data; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data are available at 10.1038/s42004-025-01662-4.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

KRAS (G12D, 1–169) was cloned into the pET-30 vector to be expressed with an N-terminal His6 tag and a TEV cleavage site. SOS (564-1049) was cloned into the pET-28 vector to be expressed with an N-terminal His6-T7 tag and a TEV cleavage site. RAF1 (cRAF) was cloned into the pGEX-2T vector to be expressed as an N-terminal GST fusion protein. Each plasmid was transformed into the Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) strain, and protein expressions were induced with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) in TB media. KRAS (G12D, 1–185) and KRAS (WT, 1–185) were cloned into the pET-28 vector to be expressed as a fusion protein with an N-terminal His6 tag, a TEV cleavage site, and Avi-tag. Each Avi-tagged protein was co-expressed with BirA biotin ligase in BL21(DE3) cells cultured in TB medium and induced with IPTG. VHL (54–213) was cloned into the pET-28 vector to be expressed with an N-terminal His6 tag and a thrombin cleavage site, and EloB (1–118) and EloC (17–112) were cloned into the pCDFDuet-1 vector. BL21(DE3) was co-transformed with both plasmids, cultured in LB medium, and induced with IPTG.

To prepare the KRAS (G12D, 1–169) protein, the cell pellet was lysed by sonication in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 0.5% (w/v) CHAPS, 5 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF). After centrifugation, the supernatant was subjected to Ni-NTA Superflow chromatography (QIAGEN), and then the KRAS protein was eluted with 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.5 mM TCEP, and 250 mM imidazole. The His6 tag was cleaved by Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease treatment and removed by the second round of affinity purification. The purified KRAS protein was treated with 1 mM GDP and Alkaline phosphatase-Agarose (SIGMA, 2 U per mg of KRAS) in 32 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 200 mM ammonium sulfate. After 40 minutes of rotating at room temperature, Alkaline phosphatase-Agarose was removed by passing through an empty column, and the buffer was exchanged to 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM magnesium chloride, and 1 mM DTT. The protein was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) using HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg (Cytiva) in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM magnesium chloride, and 1 mM DTT. For crystallization, peak fractions were concentrated to a final concentration of 49.2 mg ml−1 in 20 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT.

Avi-tagged KRAS proteins were purified from KRAS/BirA co-expressing Escherichia coli. Purification steps of the Avi-KRAS (G12D, 1–185) and Avi-KRAS (WT, 1–185) were similar to those for KRAS (G12D, 1–169) except as follows: The cell pellet was lysed by sonication in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) instead of Tris-HCl (pH 7.5); proteins were eluted from Ni-NTA with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, and 250 mM imidazole; prior to His6 tag cleavage, the purified protein was treated with GDP/Alkaline phosphatase.

To prepare SOS protein, the cell pellet was lysed by sonication in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 1 mM PMSF. After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded onto Ni-NTA Superflow. The His6-T7 tagged SOS was eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 250 mM imidazole and then precipitated with 60% ammonium sulfate. The His6-T7 tag was cleaved by TEV protease and separated with the second Ni-NTA Superflow column. The protein was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg (Cytiva) in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT.

To prepare cRAF protein, the cell pellet was lysed by sonication in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF. After centrifugation, the supernatant was subjected to Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (Cytiva), and cRAF protein was eluted with 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 10 mM glutathione (reduced form). The protein was further purified with 60% ammonium sulfate precipitation, and then the precipitant was dissolved into a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT. Finally, the residual ammonium sulfate was removed by a PD-10 desalting column (Cytiva).

To prepare His6-tagged VHL/EloC/EloB ternary complex (VCB) for assay development, the cell pellet was lysed by sonication in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP, and 1 mM PMSF. After centrifugation, the supernatant was subjected to Ni-NTA Superflow, and then VCB protein was eluted with 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 250 mM imidazole. The His6-tagged VCB was applied onto the Resource Q column (Cytiva) equilibrated with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM DTT, and then eluted with an increasing NaCl gradient. The protein was further purified by HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg column equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT and concentrated to 12.0 mg ml−1. For crystallization, the His6 tag was cleaved by thrombin protease following Ni-affinity purification and removed with the second Ni-NTA Superflow column. After Resource Q purification with the same conditions above the VCB was subjected to HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg column equilibrated with 20 mM Bis-tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. The peak fractions were concentrated to a final concentration of 23.7 mg ml−1.

X-ray crystallography

KRAS (G12D) protein in complex with compound 1

KRAS (G12D, 1–169) and compound 1 were mixed (1:2.8 molar ratio) with 5 mM GDP and 5 mM magnesium chloride and incubated for 30 minutes on ice. Crystallization was performed by sitting-drop vapor diffusion methods using a reservoir containing 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0–8.5), 200 mM magnesium chloride, 500 mM NaCl, and 34% (w/v) PEG3350. Crystals were harvested and flash-frozen in a SSRL cassette (Crystal Positioning Systems), precooled with liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the beamline AR-NE3A in the Photon Factory. The dataset was indexed and integrated using XDS53. The structure of KRAS was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser54. Ligand fitting and dictionary generation were performed by AFITT-CL (OpenEye Scientific), followed by manual improvement of the model with COOT55, and refinement with REFMAC556.

Crystallization of the ternary complex

KRAS (G12D, 1–169), VCB, and ASP3082 were mixed (2.1:1:1.4 molar ratio) with 2 mM GDP and 2 mM MgCl2 and incubated for 1 h on ice. Crystallization was performed by sitting-drop vapor diffusion methods using a reservoir containing 100 mM bis-tris propane (pH 6.5–7.0), 250 mM sodium formate, and 22% (w/v) PEG3350. Crystals were harvested and flash-frozen in Universal V1-Puck (Crystal Positioning Systems) precooled with liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected on the beamline BL41XU at Spring-8. The dataset was automatically indexed and integrated using KAMO57. The structures of KRAS and VCB were solved by molecular replacement with Phaser. Ligand fitting and dictionary generation were performed by AFITT-CL, followed by manual improvement of the model with COOT and refinement with REFMAC5.

Molecular modeling of the ternary complex

Modeling was conducted using the software Maestro 2023-3. To construct the ternary complex model of KRAS, VCB, and compound 2, with the conformation of each ligand of compound 2 fixed to that of each co-crystal structure (PDB code: 9L6A for KRAS and 4W9H for VHL), a conformational search was performed only on the single bond connecting the two ligands by the MacroModel program with the Mixed torsional/Low-mode sampling method. The maximum number of steps to take in sampling algorithms was set to 10,000. Twenty conformers of compound 2 were generated, and ternary complex models were constructed using the co-crystal structures of KRAS and VCB by superimposing the ligand on each conformer. The most plausible PPI model described in Fig. 1a was selected from the 20 ternary complex models.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor analysis

SPR assay using immobilized KRAS(G12D) protein

Biotinylated Avi-KRAS (G12D, 1–185) protein was immobilized to the SA sensor chip using a Biacore T200 SPR instrument (Cytiva) at 25 °C. Proteins were immobilized on the chip as follows: The sensor chip surface was pre-equilibrated in running buffer #1 (HBS-P+, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 μM GDP); then, following three consecutive injections of 1 M NaCl/50 mM NaOH (60 sec at 10 μl min−1 flow rate), 1 μg ml−1 biotinylated Avi-KRAS(G12D, 1–185) protein was immobilized for 360 sec at 10 μl min−1 flow rate with running buffer #1, and bound approximately 2500 RU; the flow path was washed with 50% isopropanol in 50 mM NaOH and 1 M NaCl solution between cycles.

A series of dilutions of test compounds in DMSO was initially diluted with the running buffer #1 and mixed with the same amount of the running buffer #1 with or without 189 nM of His6-tagged VCB protein. These serial dilutions were injected sequentially in single-cycle mode (contact time 90 sec, flow rate 30 μl min−1) with regeneration (regeneration buffer: 10 mM Acetate (pH 3.6), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 µM GDP). For multicycle mode measurement, solutions of test compounds were prepared in the running buffer #1 and were injected individually (contact time 90 sec, flow rate 30 μl min−1, dissociation time 300 sec) with regeneration.

SPR assay using immobilized VCB protein

His6-tagged VCB proteins were immobilized to the NTA sensor chip using a Biacore T200 SPR instrument at 25°C. Proteins were immobilized on the chip as follows. The sensor chip surface was pre-equilibrated in running buffer #2 (HBS-P+, 50 μM EDTA, 1 μM GDP). Then, following continuous injections of 350 mM EDTA (60 sec at 10 μl min−1 flow rate), 500 μM NiCl2 (60 sec at 10 μl min−1 flow rate), a mixture of 400 mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and 100 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (600 sec at 10 μl min−1 flow rate), 10 μg ml−1 His6-tagged VCB proteins were immobilized for 420 sec at 10 μl min−1 flow rate with running buffer#2, and bound approximately 7000 RU. After the injection of ligand, 1 M ethanolamine (300 sec at 10 μl min−1 flow rate) and 350 mM EDTA (60 sec at 10 μl min−1 flow rate) were passed over the sensor surface to deactivate remaining active esters.

A series of dilutions of test compounds in DMSO was initially prepared in the running buffer #2. These serial diluted solutions were injected sequentially in single-cycle mode (contact time 90 sec, flow rate 30 μl min−1). All SPR experiments were performed at 25 °C.

SPR data analysis

Data were analyzed using Biacore T200 Evaluation Software ver. 1.0 (Cytiva), and we calculated the association rate constant (ka), dissociation rate constant (kd), dissociation constant (KD), and maximum analyte response (Rmax) value. The geometric means of ka, kd, KD, and Rmax values were calculated by Sigmoid-Emax non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad software).

Cell-free TR-FRET KRAS-RAF (Inhibitory activity on SOS-mediated KRAS-RAF interactions)

Test compounds (DMSO solution) were incubated with 400 nM biotinylated Avi-KRAS(G12D, 1–185) or biotinylated Avi-KRAS(WT, 1–185) protein for 10 min with or without VCB. To the mixtures were added 1.3 μM SOS (564–1049) and 130 nM GST-tagged cRAF containing 4 μM GTP. After incubating for 1 h, 120 nM ULight-anti-GST antibody (PerkinElmer) and 100 ng ml−1 LANCE Eu-W1024 Streptavidin (PerkinElmer) were added. Time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) measurements were performed on EnVision Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer) with the following settings: 337 nm excitation, 665 nm, and 620 nm emission. The TR-FRET ratio was taken as the 665/620 nm intensity ratio. The readings were normalized to the control (DMSO with or without GTP), and the IC50 was calculated by non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

Cell lines and cell culture

AsPC-1, HPAC, HT-29, A375, BxPC-3, SK-CO-1, NCI-H358, HCT 116, and NCI-H1299 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC); PK-59, PK-1, and COLO-320 cells were purchased from RIKEN BRC; LCLC-97TM1, SW-403, and PA-TU-8902 cells were purchased from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ); GP2d, GP5d and PSN1 cells were purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC); and KP-4 and T24 cells were purchased from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (JCRB). All cell lines were cultured according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. All media were supplemented with 10% (or 20% for KP-4) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin–streptomycin solution (50 U ml−1 and 50 μg ml−1; Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cell lines were incubated at 37 °C in 5% (or 0% for SW-403) CO2. The cell lines used in this study were purchased from providers of authenticated cell lines and stored at early passages in a central cell bank at Astellas Pharma Inc. The experiments were conducted using low-passage cultures of these stocks with mycoplasma testing.

Cell assay

In-Cell ELISA KRAS (G12D) degradation assay

AsPC-1 cells were seeded in 384-well clear plates at 2 × 104 cells per well. The following day, DMSO (as a negative control) or DMSO solutions of test compounds diluted in medium to multiple concentrations ranging from 0.1 nM to 10 μM (final) were added to each well. After incubation for 24 h, the medium was removed, and cells were fixed with 4% para-formaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min. The plates were treated with blocking buffer, and then the mixture of anti-RAS(G12D) rabbit (Cell Signaling Technology (CST)) and anti-β-actin mouse (Abcam) antibodies in blocking buffer was added to each well as primary antibody and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following day, the plates were washed with PBS, and the mixture of IRDye800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR Biosciences) and IRDye680RD donkey anti-mouse IgG (LI-COR Biosciences) antibodies in blocking buffer was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were washed with PBS and dried for at least 2 h in the air. The fluorescence signals were quantified using the Aerius (LI-COR Biosciences), an automated infrared imaging system. The KRAS(G12D) signal was normalized with the β-actin signal for each well. KRAS degradation activity was converted to a percentage as 0% (DMSO only) and 100% (without RAS(G12D) antibody staining). The half maximal (50%) degradation concentration (DC50) values of test compounds were calculated by Sigmoid-Emax non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

In-Cell ELISA ERK1/2 phosphorylation (p-ERK) assay

AsPC-1 or A375 cells were seeded in 384-well clear flat plates at 2 × 104 cells per well. The following day, DMSO (as a negative control) or DMSO solutions of test compounds diluted in medium to multiple concentrations ranging from 0.1 nM to 10 μM (final) were added to each well. Trametinib, a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor, was used as a positive control at a final concentration of 1 μM. After 2 or 24 h of incubation, cells were fixed with 30% glyoxal in PBS for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X100 in PBS for 10 min. The plates were treated with blocking buffer, and anti-p-ERK 1/2 rabbit antibody (CST) was used as a primary antibody and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following day, the plates were washed with 0.05% Tween 20-containing PBS (PBS-T), and IRDye800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody in blocking buffer was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were washed with PBS-T and dried for at least 3 h in the air. The fluorescence signals were quantified using the Aerius. Inhibitory activity of ERK phosphorylation was converted to a percentage as 0% (DMSO only) and 100% (trametinib-treated). The half maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of test compounds were calculated by Sigmoid-Emax non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

In vitro cell growth assay

The cells were seeded in low-attachment 96-well or 384-well round-bottom white plates (Sumitomo Bakelite) at 100–1000 cells per well. The following day, DMSO (as a negative control) or DMSO solutions of test compounds diluted in medium to multiple concentrations ranging from 0.1 nM to 10 μM (final) were added to each well. After six days of incubation, CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 Reagent (Promega) was added to each well, and luminescence intensity was measured using a multi-label plate reader ARVO-X3 (Perkin Elmer). Inhibitory activity of cell growth was converted to a percentage as 0% (DMSO only) and 100% (without cell seeding). The IC50 values of test compounds were calculated by Sigmoid-Emax non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

Proteomic analysis

AsPC-1 cells were plated in 10 cm dishes and incubated for 4 days to reach sub-confluent. Cells were treated with DMSO or ASP3082 (final concentration of 1 μM) for 4 and 24 h at 37 °C. Treated cells were collected and washed twice with PBS, and cell pellets were stored at −80 °C. Sample preparation for Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Liquid Chromatography (LC)-MS/MS analysis were performed by Kazusa DNA Research Institute. The obtained MS data (quintuplicate) were analyzed using Scaffold DIA v2.2 (Proteome Software) at Kazusa DNA Research Institute for the identification of proteins and the quantification of individual protein expression. To evaluate each individual protein degradation, the percentages of the average protein abundance of ASP3082-treatment versus that of DMSO-treatment were calculated with quantitative values. The list of individual protein expression levels can be found in Supplementary Table 2 (Supplementary Data 1).

Immunoblot analyses (in vitro)

Cells were seeded and incubated overnight. Cells were treated with the solution of test compounds in the indicated dilution series or DMSO (as negative control) and incubated at 37 °C for the indicated time. Then, cells were lysed with lysis buffer, and lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Membranes were blocked with blocking reagent for Can Get signal (TOYOBO), washed with PBS-T, and incubated with each primary antibody overnight. After the incubation, the membranes were washed with PBS-T, and then incubated with each secondary antibody for 1 h. After the incubation, the membranes were washed with PBS-T, and finally, ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Cytiva) was added to the membranes for chemiluminescent signal detection, and images were taken with ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories), ImageQuant™ LAS4000 (Cytiva), or Lumi Vision PRO 400EX (Aisin). The antibodies used in each experiment are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

For competition assays (Fig. 2e), cells were pre-treated with MG-132 (10 µM) for 1 h, before being treated with ASP3082.

RAF-RBD pulldown assay

The active form of KRAS was detected using an RAF-RBD pulldown assay. The cell lysate was prepared as described in the previous method and was mixed with MagneGST™ Glutathione Particles (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the GST-tagged RAS-binding domain (RBD) of RAS effector kinase Raf1 (GST-Raf-RBD; CST). After incubation for 1 h at 4 °C with constant rocking, the beads were washed three times with the lysis buffer and eluted through the process of protein denaturation with lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer including DTT. The eluted proteins were used to perform the immunoblot analyses described above to detect KRAS-GTP and GST-Raf-RBD.

VHL knockdown assay with siRNA

Anti-human VHL siRNA (ON-TARGETplus Human VHL (7428)), anti-human KRAS siRNA (ON-TARGETplus Human KRAS), and control siRNA (ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting Pool) were purchased from Dharmacon. siRNAs used in this study were provided in Supplementary Table 4. PK-59 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at 3 × 104 cells per well for immunoblotting and then incubated with 10 nM siRNA (anti-human VHL siRNA or control siRNA) and Lipofectamine RNA iMAX (Invitrogen) mixture. Two days after the treatment, the cells were collected by adding lysis buffer and subjected to immunoblot analysis. For the evaluation of KRAS degradation activity of ASP3082 with anti-human VHL siRNA or control siRNA, PK-59 cells were seeded in a 384-well plate at 4 × 103 cells per well and then incubated with 10 nM siRNA (anti-human VHL siRNA or control siRNA, or anti-human KRAS siRNA) and Lipofectamine RNA iMAX mixture for 3 days. ASP3082 was treated in the siRNA-treated group (not in the si KRAS-treated group) for 24 h, and In-Cell ELISA KRAS degradation assay was performed as described above using rabbit anti-RAS(G12D) and mouse anti-β-actin (Abcam) antibodies with IRDye800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG and IRDye680RD donkey anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies. The signals of the DMSO-treated group under each siRNA treatment condition were used as 0% and those of the si KRAS-treated group as 100%. The DC50 value of ASP3082 was calculated by Sigmoid-Emax non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

In vivo anti-tumor studies in xenografts

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Astellas Pharma Inc., Tsukuba Research Center, which is accredited by AAALAC International. Mice were housed in individually ventilated cages, depending on group size (5–8 mice per cage) and maintained on water and a standard diet throughout the experimental procedures. For cancer cell line-based xenograft (CDX) studies, PK-59, AsPC-1, HPAC, PK-1, GP2d, GP5d, A375, KP-4, and HT-29 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into the flank of 4–8 week-old male nude mice (Balb/c nu/nu; The Jackson Laboratory Japan or Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd) at 1–6 × 106 cells per 0.1–0.2 ml (Matrigel (Corning):PBS = 1:1)/mouse and allowed to grow. For patient-derived xenograft (PDX)-based studies conducted at Charles River Discovery Research Services Germany GmbH, each tumor (LXFA 1125 and LXFA 2204) was subcutaneously implanted into nude mice (Crl:NMRI-Foxn1nu; Charles River) and allowed to grow.

The mice were randomized into treatment groups based on tumor volume and were administered the vehicle (5% glucose solution with 4% ethanol (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation)/0.5% (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (HP-βCD; Roquette Frères)/9% hydrogenated castor oil 40 (HCO 40; NIKKO Chemicals Co., Ltd)) or ASP3082 solution intravenously once or twice a week, or subcutaneously daily. Body weight and tumor diameter were measured using a balance and a caliper, respectively. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula length × width2 × 0.5. Tumor growth inhibition rate (TGI) was calculated using the following formula:

Tumor growth inhibition rate [%] = 100 × [1 − (mean value of difference in tumor volume between day at the end of the study and day 0 or 1 (at the start of each study) in each group [mm3]) / (mean value of difference in tumor volume between day at the end of the study and day 0 or 1 in the vehicle group [mm3])].

Tumor regression rate was calculated in groups whose tumor growth inhibition exceeded 100%, as follows:

Tumor regression rate [%] = 100 × [1 − (mean tumor volume of each group on day at the end of the study [mm3]) / (mean tumor volume of each group on day 0 or 1 [mm3])].

Pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) assays

PK-59 xenograft mice were used 25 days after subcutaneous implantation. Mice were intravenously administered the vehicle used in the in vivo anti-tumor study or 10 or 30 mg/10 ml/kg of ASP3082. Blood, tumors, and pancreas were collected from three mice at 2, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 144 h after administration. Blood samples were collected under anesthesia. After the mice were euthanized, tumor and pancreas samples for PK and PD analysis were collected from the same mice. The plasma samples were prepared with centrifugation (5000 × g for 10 min, 4 °C). The tumor and pancreas samples for PK analysis were added with 4-fold PBS and homogenized with a bead homogenizer. All samples were frozen until used for measurement.

For pharmacokinetic (PK) assay, plasma, tumor, and pancreas homogenate samples were mixed with reagents including methyltestosterone as the internal standard, and centrifuged at 1880 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was analyzed with a liquid chromatograph-tandem mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS; AB SCIEX, Shimadzu). The LC-MS/MS conditions are also shown in Supplementary Table 5. PK parameters were calculated from the mean concentration of three mice at each time point using the noncompartmental analysis model of Phoenix WinNonlin ver. 8.1 software (CERTARA). The means and the standard deviations of plasma, tumor, and pancreas concentrations were calculated using Microsoft Excel for Office 365 MSO. The concentration-time–time profiles in plasma, tumor, and pancreas were described by using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

The tumor samples for PD analysis were homogenized with lysis buffer using a bead homogenizer. Samples were centrifuged (20400 × g for 10 min) and the supernatants were collected for immunoblotting.

Band intensities of RAS(G12D) were estimated using Image Lab6.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and relative band intensities were calculated using Microsoft Excel for Office 365 MSO. Each band intensity of KRAS(G12D) was divided by the band intensity of β-actin for normalization, and relative quantification of KRAS(G12D) was performed by comparing to the average of vehicle samples for each time point. The decrease rate of relative KRAS(G12D) band intensities means KRAS(G12D) degradation.

Gene expression analyses (quantitative realtime PCR)

Total RNA extraction from tumor tissues was performed with the NucleoSpin RNA plus (Macherey-Nagel). cDNA was generated by using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for qPCR. Equal amounts of cDNA in each sample, TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix, and TaqMan Probe/Primer were mixed and applied to qPCR by using Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 12 K Flex with equipped software version 1.3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). TaqMan Probes/Primers used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table 6. Expression levels were normalized to beta-2-microglobulin (B2M). Each relative gene expression was quantified by comparing to the average of vehicle samples for each time point.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tumor samples were collected from the vehicle or ASP3082-treated mice (LXFA 1125 or LXFA 2204 xenograft model) in 24 h (LXFA 2204) or 3 days (LXFA 1125) after the final dose of ASP3082. Tumors were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for approximately 24 h and then transferred to 70% ethanol for up to 7 days. Thereafter, samples were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on paraffin sections. Briefly, after deparaffinization, antigen retrieval was performed in an autoclave for 10 min at 110 °C. The heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) solution was prepared by mixing 2 parts of EDTA pH 9 of 10× target retrieval concentrate (Dako) and 1 part of citrate pH 6 of 20× concentrate (0.2 M citrate, 1% Tween 20) with 17 parts of Milli-Q water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with H2O2, followed by washing with water and PBS-T and blocking buffer (Protein Block Serum-Free, Dako). The anti-RAS(G12D) antibody (CST) was diluted to 1:100 with diluent (BOND Primary Antibody Diluent, Leica) and applied to slides. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, slides were washed with PBS-T and then incubated with a secondary antibody kit (N-Histofine Simple Stain MAX-PO(R), Nichirei Biosciences). Slides were washed with PBS-T, and positive labeling was detected by exposing the sample to a DAB substrate kit (ImmPACT DAB EqV, Vector). Slides were washed with Milli-Q water, and counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin (Wako). Slides were washed with water and dehydrated by ethanol and xylene, and were sealed and coverslipped with a water-free mounting media (Entellan, Merck). A whole slide image was obtained by use of a digital slide scanner (NanoZoomer-XR, Hamamatsu Photonics). Digital image analysis was carried out with an image analysis platform (HALO 3.3, Indica Labs), and H-score was evaluated with use of the Membrane IHC module (Membrane v1.7, Indica Labs). The H-score is calculated as follows: (1 × percentage of weak staining) + (2 × percentage of moderate staining) + (3 × percentage of strong staining) within the target region, ranging from 0 to 300.

In vitro plasma protein binding

In vitro unbound fraction ratios in mice were evaluated using the ultracentrifugation method. ASP3082 was added to CAnN.Cg-Foxn1nu/CrlCrlj(nu/nu) mouse plasma to make concentrations of 10, 5,0 and 200 µg/mL (n = 3). The plasma samples were incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. The incubated plasma samples were transferred to polypropylene tubes to determine the total concentration. The incubated plasma samples were separately transferred to ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman Coulter), and then ultracentrifuged (approximately 436000 × g, 4 °C, 140 min). After ultracentrifugation, an aliquot of the upper part from the middle layer of the three layers of the samples was transferred to the polypropylene tube to determine the unbound fraction. The total concentration samples and unbound fraction samples were deproteinized by adding internal standard solution and methanol, and the supernatant was analyzed with an LC-MS/MS (AB SCIEX, Shimadzu). The mean unbound fraction ratio was calculated using Microsoft Excel for Windows.

Chemical synthesis

Detailed protocols for chemical synthesis and analytical data are provided in the Supplementary Note section of Supplementary Information.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description_of_Additional_Supplementary_Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yukihito Sugano for spectroscopic measurements (single crystal X-ray crystallography), Dr. Noriyuki Sakiyama for construction of the ternary complex model of KRAS(G12D)/degrader 2/VHL, Hazuki Tanaka, Mutsumi Takahashi, Mayo Kikuchi, Shinobu Shirata, and Takuto Nisimoto for the biological and pharmacological assay, Akemi Fujiwara for crystallization of protein, Aki Bando, Ayano Watanabe, and Mayo Shinozaki for protein expression and purification, and Dr. David Barrett for proofreading the manuscript. This study was funded by Astellas Pharma Inc.

Author contributions

T.Y. designed and synthesized the degrader molecules, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript with input from all authors. T.N. conceived and designed the biological and pharmacological experiments and analyzed the data. H.I. designed and synthesized the degrader molecules and analyzed the data. K.Inamura conceived and performed the experiments and analyzed the data related to the biophysical assay and immunoblot assay. M.T. performed the biological and pharmacological experiments, analyzed the data, and arranged the figures. Y.N., K.Iguchi, C.S., A.S. and A.N. performed the biological and pharmacological experiments and analyzed the data. Y.A. performed the crystallization and X-ray diffraction structural analysis. Y.T. expressed and purified the proteins. Y.Y. analyzed PK data. F.O. performed gene expression analyses. M.Y. performed the experiments on immunohistochemistry. K.K. and T.I. designed and synthesized the inhibitor molecules. M.H. supervised the research. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or Supplementary Information. The previous structural data that support the findings of this study are available in the PDB (ID: 4W9H). Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures in this work have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 9L6A (GDP-bound KRAS(G12D) complexed with compound 1) and 9L6F (ternary complex of GDP-bound KRAS(G12D)/ASP3082/VCB). Experimental procedures and analytical data for compound characterization (NMR, LCMS, etc.) are available within Supplementary Information and NMR spectra are available as Supplementary Data 2. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under deposition numbers CCDC 2412699 (S12) and 2412700 (S8b). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Source data are provided with this paper as Supplementary Data 3.

Competing interests

All authors are employees of Astellas Pharma Inc. and its affiliates.

Ethics approval and consent to participate