Abstract

Biofilm microbial communities encased in extracellular polymeric substances are a concern in drinking water premise plumbing and fixtures, and are challenging to remove and disinfect. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), a commonly used surrogate organism, is employed in this study due to its widely documented occurrence in biofilms within drinking water systems. This study investigates 280 nm UV light emitting diodes (UV LEDs) for inactivating P. aeruginosa biofilms grown on common plumbing materials extruded Polytetrafluoroethylene, Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene, Viton®, Silicone, High Density Poly Ethylene, Stainless Steel, Porex (expanded PTFE), and Polycarbonate. Biofilms were cultivated in CDC biofilm reactors on 12.8 mm diameter coupons and then exposed to UV LED light at fluences ranging from 5 to 40 mJ/cm2 with log reduction values between 0.851 and 2.05 CFU/cm2 for Viton® (k = 0.133 ± 0.0625 cm2/mJ) and Silicone (k = 0.344 ± 0.145 cm2/mJ), respectively. This research demonstrates that material properties influence biofilm formation and the subsequent effectiveness of UV LED inactivation while illustrating that characteristics such as surface roughness and reflectivity significantly impact inactivation. This work advances the understanding of biofilm inactivation under UV LED exposure, thereby aiding in the development of more effective biofilm inactivation strategies.

Keywords: Ultraviolet, UV LED, Inactivation, Biofilm, Water treatment

Subject terms: Applied microbiology; Civil engineering; Lasers, LEDs and light sources

Introduction

Biofilm accumulation within distribution systems presents a significant challenge for utilities and point-of-use (POU) systems1–3. Biofilms, robust and protected microbial communities, exhibit significant resistance to removal and inactivation once established. Composed of various microorganisms and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), biofilms are complex and resilient4. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is a commonly used surrogate due to its rapid growth, biofilm formation, and well-characterized ultraviolet (UVC) dose response5–8. While material chemistry and texture facilitate attachment kinetics and biofilm formation mechanisms, there is a gap in understanding the microbial properties of materials.

Opportunistic pathogens play a crucial role in biofilm-related issues within distribution and plumbing systems. These microorganisms, including P. aeruginosa and Legionella pneumophila, exploit favourable conditions to establish infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals9,10. Biofilms provide a protective environment via EPS that enhances the survival and persistence of these pathogens, shielding them from environmental stresses and antimicrobial treatments11. The presence of opportunistic pathogens within biofilms poses significant public health risks, as they can lead to chronic infections and outbreaks associated with water distribution systems and medical devices12–15. Established biofilms can be challenging to treat using conventional chemical disinfectants, and the physical removal of biofilms can be infeasible in many scenarios16–18. Fortunately, inactivation via UVC light is a potential treatment tool for biofilm management7,8,19.

Biofilm inactivation studies utilize a variety of material types to mimic real-world applications and evaluate the effectiveness of inactivation protocols. These materials often include stainless steel, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene, polycarbonate, and silicone, each selected for its relevance in different settings20,21. Stainless steel is widely used in medical devices and food processing equipment due to its durability and resistance to corrosion22. PVC and polyethylene are prevalent in water distribution systems and plumbing due to their cost-effectiveness and ease of installation23–25. Polycarbonate is commonly used in laboratory settings for workspace portioning and shielding26. Silicone, known for its flexibility and biocompatibility, is frequently used in medical tubing and implants27. The choice of these materials in biofilm studies is significant as it allows for the assessment of biofilm formation and inactivation efficacy under conditions that closely replicate practical environments. Understanding how biofilms interact with varied materials and their response to inactivation treatments is crucial for developing tailored strategies to prevent and control biofilm-related issues in various industries.

UVC irradiation as a disinfection method has been employed across sectors for decades and is a well-accepted method for the inactivation of bacteria, viruses, and fungi by altering the genomes of the microbes and therefore rendering them non-viable for replication28. Emerging UV light emitting diodes (LEDs) have the potential to disrupt this well-established space by providing similar inactivation capabilities but with more energy-efficient and longer lasting lamps2,29,30. UV LEDs offer mercury and chemical-free inactivation technology when compared to conventional mercury-based UV lamps and chemical disinfectants.

The advancement of UV LEDs in the inactivation space has been conceptualized in research; however, applications and systems are still emerging. The flexibility of the compact-size UV LEDs in reactor design allows for the creation of systems that were previously impossible to design using traditional mercury-based UV systems1. The use of UV LEDs within pipe systems shows effective treatment at the bench scale, with ongoing developments in the technology contributing to increased efficiency, energy savings, and environmental benefits31,32. Advancements in UV LED technology include improvements in energy consumption and longevity, which increase the suitability for more ambitious applications. Potential applications of UV LED inactivation systems extend beyond water treatment to areas such as air purification, surface disinfection in industrial settings, and even medical applications, where precise and targeted inactivation is critical33–36. As the technology continues to evolve, its adaptability, cost-effectiveness, and energy efficiency position UV LEDs as a promising solution for a wide range of disinfection challenges. A recent review identified several research gaps in UV LED biofilm which includes minimal investigation of the effects of direct exposure of surface-bound biofilms and characterization of support surfaces37. This indicates that to continue to advance development impacts of support surfaces need to be better reported.

The behaviour and impact of various materials under UVC exposure during stages of biofilm development remain poorly understood. To overcome the challenges, this study aimed to address this gap by investigating the effects of UVC exposure on pure-culture P. aeruginosa across eight materials commonly used in plumbing, storage tanks, and other wetted surface use cases. Understanding the behaviour of biofilm communities and their response to inactivation methods is essential for developing effective strategies to mitigate biofouling. This investigation aids in closing identified knowledge gaps regarding the applicability of UV LED disinfection systems and determines the suitability of materials to be used in conjunction with these systems.

Methods

Biofilm reactor and material selection

A CDC Biofilm reactor (model CBR 90-1, BioSurface Technologies Corp., Bozeman, MT, USA) was assembled following the operator’s manual provided by the manufacturer38. The method for biofilm growth was adapted from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) standard operating procedure MB-19-0639. The reactor was filled aseptically with 500 mL of sterile growth medium (300 mg/L TSB) and 1 mL of P. aeruginosa culture to initiate the batch phase. The reactor was set to stir continuously at approximately 125RPM at 23 °C ± 1 °C for 24 ± 2 h. Following the batch phase, the reactor was switched to a continuously stirred mixed reactor (CSTR) system with a 100 mg/L solution of TSB flowing at a rate of 10 mL/min for 24 ± 2 h. After the completion of the CSTR portion, the rods were removed from the reactor, and the coupons were removed with sterile forceps with care not to disrupt biofilm growth.

Biofilm-covered coupons of different common plastics, elastomers, and metals were chosen based on their varying characteristic as wetted surfaces. UV LED exposure on the coupons simulates the application of UV inactivation within a pipe, reservoir, or tank. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual layout of this experiment, where biofilm-laden coupons are exposed to UV light to understand how material type impacts inactivation.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual diagram of CDC coupon biofilm growth and UVC LED exposure (purple) of wetted surfaces (green).

Coupons were purchased from BioSurface Technologies (BioSurface Technologies Corp., Bozeman, MT, USA). Materials which were not available were purchased in sheets and machined to a diameter of 12.8 mm and a thickness not exceeding 3.8 mm. Coupons were sonicated for 5 min at 37 kHz with laboratory-grade soap in deionized water. Coupons were rinsed and sonicated until no suds remained. The coupons were rinsed with 70% ethanol, followed by three rinses of sterile deionized water and laid in a single layer to dry.

Microbial methods

A pure culture of P. aeruginosa (ATCC 15,442) was obtained from ATCC as a freeze-dried pellet. The pellet was rehydrated with 6 mL of tryptic soy broth (TSB, BD 211825) and vortexed to ensure the pellet was completely disaggregated. Several drops of the suspension were transferred to tryptic soy agar (TSA, BD 236950) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, a single colony was collected from the plate using a sterile loop and transferred to 10 mL of TSB in a sterile 15 mL tube and incubated for an additional 24 h at 37 °C and 175 RPM. Vegetative Frozen Stocks (VFS) were prepared in 20% glycerol and held at − 80 °C until needed.

P. aeruginosa for use in the CDC reactors was prepared by pipetting 100 µL of VFS into 10 mL of sterile TSB and incubating overnight (18–20 h) at 37 °C, 175 RPM (New Brunswick Shaker Incubator, Edison, NJ, USA). Before use, the overnight P. aeruginosa culture was vortexed for one minute at 3000 RPM.

Biofilm recovery

Using recovery methods modified from Gora et al.7, the biofilm was removed from the coupon surface by rolling a sterile cotton swab across the surface in a consistent pattern. The swab was dipped in 20 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to resuspend the biofilm and repeated five times. The recovered biofilm suspension was vortexed for 30 s to homogenize the sample before serial dilutions were prepared for plating on TSA. Biofilm quantification was performed using standard plate counts. Biofilm samples were serially diluted, plated on TSA, inverted and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Following incubation, colonies were counted to quantify colony forming units (CFUs).

The resuspension of the biofilm in buffer solution to facilitate quantification does limit observable inactivation results, as losses naturally occur during this step.

Biofilm inactivation

A PearlLab Beam T equipped with 280 nm UV LEDs was used for all UV exposures (AquiSense, Erlanger, KY, USA). Irradiance was measured daily before experimentation using an Ocean Optics USB4000 spectroradiometer (Ocean Optics, Orlando, FL, USA), and exposure times were calculated by following the Bolton and Linden method40. UV experiments were completed under the cover of red light in a dark room to minimize photo-repair effects41. Coupons were removed from the reactor immediately before irradiation and were aseptically transferred to a sterile glass dish. A rotating platform (30 RPM) was placed under the collimated beam to mimic a completely mixed sample42. All experiments were completed in triplicate with duplicate plating.

The efficacy of the inactivation method was evaluated by calculating the log reduction value, which represents the logarithmic decrease in CFU post-treatment when compared to pre-treatment control samples. Log reduction values (LRVs) using Eq. 1, where N0 represents pre-treatment cell counts and N represents post-treatment cell counts in CFU/mL.

| 1 |

Surface characterization

Diffuse reflectance of materials was measured using an integrating sphere system43. Each material sample, prepared on a stable holder, underwent measurements where incident light entered the sphere through an entrance port, underwent multiple diffuse reflections, and was collected through a separate port for spectral analysis using a calibrated spectrometer. A reference measurement without the sample accounted for system losses. Surface roughness and roughness profiles were captured using a 3D laser scanning microscope (VK-X1000, KEYENCE, Itasca, IL, USA).

Data analysis

Data was imported into R and modelled using Geeraerd’s model44. A non-linear model has been used for UV inactivation in several studies as it is based on first-order inactivation while also considering the shouldering and tailing of challenge microbes6,7,45–48. Shouldering refers to the shape and slope of the early stages of the disinfection curve, whereas tailing refers to the mathematical limit of the model describing the ceiling of disinfection for a specific water matrix. Geeraerd’s model is suitable for UV inactivation studies as it can capture microorganisms being clumped, damaged photo-repair abilities, and the existence of resistant sub-populations6. Geeraerd’s model for non-linear microbial inactivation is shown in Eq. (2)6,49

| 2 |

where k is the inactivation rate constant calculated by the nonlinear squares (nls) function within R, No is the initial concentration of the modelled microbe, Nres is the concentration of UV–resistant sub-populations, Nt is the concentration of microbes after UV exposure, and F is UV fluence [mJ cm−2].

Results and discussion

Inactivation rates on different materials

Inactivation potential for 280 nm UV LEDs on pure culture P. aeruginosa biofilm was assessed across eight materials: extruded Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), Viton®, Silicone, High Density Poly Ethylene (HDPE), Stainless Steel, Porex (expanded PTFE), and Polycarbonate. Biofilm growth was quantified using standard plate counts, and data were analyzed using a non-linear model to determine the dose–response curve for each material tested. The UV LED irradiation reduced cell viability across all tested materials. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the dose–response curves have two regions of interest: slope and tailing.

Fig. 2.

Geeraerd’s model biodosimetry (dose–response) curves for pure culture P. aeruginosa biofilm grown in CDC biofilm reactor and inactivated with 280 nm UV LED irradiation for (a) ABS (n = 4), (b) HDPE (n = 4), (c) Polycarbonate (n = 3), (d) Porex (n = 3), (e) PTFE (n = 3), (f) Silicone (n = 5), (g) Stainless steel (n = 4), (h) Viton (n = 3).

The sloped (log-linear) region represents the rate of inactivation, whereas the tailing region demonstrates that increasing fluence does not result in additional log reduction for that test condition. Tailing may occur in instances where there is a resistant subpopulation of a microbe or if there is shielding/shadowing of a subset of microbes, which would prevent them from being exposed to germicidal light. Geeraerd’s Model can quantify this effect in the Nres term, which can provide insights into the impact of material surface in addition to microbial effects. Silicone, polycarbonate, and ABS demonstrated rapid inactivation with steep initial increases in log reduction values at lower fluence levels, achieving over 1.5 LRV at ~ 10 mJ/cm2. PTFE and ABS required higher fluences, ~ 12 mJ/cm2 and ~ 35 mJ/cm2, respectively, to achieve 1.5 LRV. Conversely, stainless steel, HDPE and Viton® did not achieve 1.5 LRV before exhibiting tailing. These observations suggest that surface characteristics play a crucial role in the susceptibility of biofilms to UV LED inactivation. Material surface impacts biofilm attachment and accumulation, which can account for differences in inactivation potential.

The fluence required to reach the tailing region of log reduction varied among the materials. Silicone and polycarbonate reached their maximum log reduction at around 10 mJ/cm2, while Porex, stainless steel and Viton® required 15 mJ/cm2, PTFE required approximately 25 mJ/cm2, and ABS and HDPE required upwards of 35 mJ/cm2. These results indicate that the effectiveness of 280 nm UV LED biofilm inactivation is highly dependent on the material’s properties and the applied fluence. The variability in LRV across tested materials demonstrates the importance of further surface characterization for results to be fully contextualized and analyzed.

The calculated inactivation rate constants (k value), residual standard errors and the peak LRV achieved for each material are provided in Table 1. These values allow for a comparison of UV LED effectiveness across material types and further illustrate the impacts and variability that material surface can have on experimental results.

Table 1.

Inactivation rate constants (k) for coupons tested for biofilm formation and inactivation in the CDC biofilm reactor when exposed to 280 nm UV LEDs.

| Material | k ± S (cm2/mJ) | N0 ± S (CFU/cm2) | Nres ± S (CFU/cm2) | RSE (cm2/mJ) | LRV peak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High density polyethylene (HDPE) | 0.0636 ± 0.0328 | 0.0104 ± 0.214 | − 1.19 ± 0.278 | 0.500 | 1.17 |

| Stainless steel (316L) | 0.200 ± 0.0870 | 0.0131 ± 0.217 | − 1.80 ± 0.170 | 0.547 | 1.45 |

| Viton® | 0.133 ± 0.0625 | 0.0300 ± 0.160 | − 1.27 ± 0.165 | 0.346 | 0.851 |

| Acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS) | 0.0604 ± 0.0215 | 0.000644 ± 0.186 | − 1.63 ± 0.318 | 0.458 | 1.57 |

| Polycarbonate | 0.288 ± 0.121 | − 0.0260 ± 0.341 | − 1.84 ± 0.208 | 0.592 | 1.84 |

| Silicone | 0.344 ± 0.145 | − 0.00932 ± 0.443 | − 1.86 ± 0.266 | 0.976 | 2.05 |

| Porex (expanded PTFE) | 0.228 ± 0.0722 | 0.0285 ± 0.245 | − 1.75 ± 0.164 | 0.432 | 1.75 |

| Extruded PTFE | 0.131 + ± 0.0422 | − 0.0968 ± 0.288 | − 1.84 ± 0.195 | 0.428 | 1.84 |

Inactivation rate constants provide a clear picture of the inactivation effectiveness across the materials tested. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed a statistically significant difference in k values among various material types (p = 3.92e−9). To further investigate these differences, a Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was run, which identified several significant comparisons. The most notable significant differences were observed between Porex and ABS, with a mean difference of 0.1527 (p = 0.000126), indicating that Porex is significantly more effective than ABS. Similarly, significant differences were found between Silicone and ABS (p = 0.00014), and PTFE and ABS (p = 0.0284), suggesting that both Silicone and PTFE also demonstrate higher effectiveness compared to ABS. In contrast, the comparisons between HDPE and ABS (p = 1.00), Polycarbonate and HDPE (p = 0.0821), as well as those between Silicone and PTFE (p = 0.535), showed no significant differences. These findings highlight the differences between materials and emphasize the importance of material choice when considering inactivation effects within a system.

Potential role of surface properties for UV inactivation of biofilms

With the limited number of published studies which employ UV LEDs for the inactivation of biofilm on material surfaces, the comparison of collected k values to published values is difficult. Pousty et al.2 employed 270 nm emitting LEDs to inactivate pure culture P. aeruginosa biofilm on three material types (PTFE, polycarbonate and PVC) and observed k-values of 0.133 ± 0.023, 0.416 ± 0.089 and 0.416 ± 0.089, respectively. The k values for PTFE and polycarbonate used in both studies fall within the confidence interval, indicating similar inactivation effectiveness between the experiments.

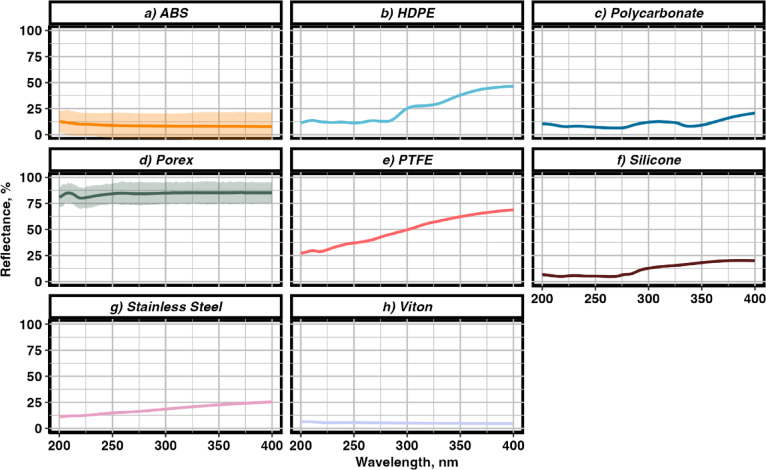

Chemicals used for surface inactivation, such as chlorine (Cl2), are commonplace in many homes and industries alike; however, these chemicals may have limited use cases due to surface or human sensitivity and the inability for their inactivation to be augmented using additive effects. Surface reflectance has been shown to impact UV irradiation, and it is hypothesized that increased surface reflection may present an additive inactivation impact for surface inactivation50,51. The diffuse reflectance for each material, measured in triplicate in increments of 0.5 nm, from 200 to 400 nm, is illustrated in Fig. 3 provides the reflectance percentage at 280 nm for each material.

Fig. 3.

Diffuse reflectance measurements of materials (a–h) used for biofilm formation in CDC biofilm reactors for inactivation by 280 nm UV LED irradiation (n = 3). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals around the mean.

The diffuse reflectance at 280 nm demonstrated a broad range of values, reflecting their varying interactions with UV light. Viton®, a firm black rubber, exhibited the lowest reflectance at 5.2%, followed by Silicone, a soft, transparent rubber, with a reflectance of 6.83%. Polycarbonate, a frosted glass-like material, showed slightly higher reflectance at 7.4%, closely followed by ABS, a hard black plastic, at 8.4%. HDPE, an opaque white plastic, reflected 12.8% of UV light at 280 nm, while Stainless Steel (316L), known for its shiny silver surface, had a reflectance of 16.7%. The two most reflective materials were PTFE, a hard white plastic, and Porex, a flexible white plastic sheet, which demonstrated reflectance of 44.2% and 84.4% respectively, at 280 nm. This variation in reflectance at 280 nm highlights the importance of material properties in UV light interaction and their potential for effective biofilm inactivation.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted on surface reflectance across the materials and revealed a significant effect of material type (p < 2e−16). Significant differences in reflectance between material pairs were also noted. HDPE demonstrated a substantially higher reflectance compared to ABS, with a difference of 16.54% (p < 0.0001), while the difference between Porex and ABS was even more pronounced at 75.71% (p < 0.0001). A two-way ANOVA examining the interaction between material and wavelength also yielded significant results for material type (p < 2e−16), wavelength (p < 2e−16), and the interaction of material with wavelength (p < 2e−16). This indicates that both the type of material and the wavelength significantly influence reflectance, and the interaction suggests the effect of material on reflectance varies with wavelength. These findings highlight the complex relationship and indicate that surface reflection can contribute to an increase in inactivation capacity. However, a greater dataset with increased material types would have to be tested to identify the extent of the impacts.

Surfaces with increased roughness or variation can contribute to increased biofilm attachment52–54. The surface roughness values are shown in Table 2, where Ra represents the average roughness of the material above the mean line, Rz is the average maximum height of the profile, and Rsm is the mean width of the profile elements.

Table 2.

Surface roughness (Ra, Avg. roughness; Rz, Roughness depth; RSm, Peak spacing) of tested materials.

| Material | Ra (µm) | Rz (µm) | RSm (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High density polyethylene (HDPE) | 4.63 | 45.89 | 1307.50 |

| Stainless steel (316L) | 3.45 | 33.33 | 1713.59 |

| Viton® rubber | 9.83 | 55.73 | 5081.31 |

| Acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS) | 3.26 | 22.77 | 1441.73 |

| Polycarbonate | 7.50 | 57.12 | 395.98 |

| Silicone rubber | 13.69 | 108.66 | 2131.00 |

| Porex | 19.86 | 100.01 | 38.61 |

| GAPI PTFE (virgin) | 10.94 | 64.01 | 2705.20 |

A correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation between surface reflectance and surface roughness (p = 0.04). These findings indicate that higher surface roughness is associated with increased diffuse reflectance. To understand the impacts on inactivation due to surface roughness, a further correlation analysis was run between k value and surface roughness (p = 0.202) and surface roughness and Nres (p = 0.484), suggesting neither correlation is statistically significant for the materials tested in this study. This indicated that surface roughness alone does not govern the potential for a material to be inactivated.

Additionally, a linear regression was run to understand the impacts of surface roughness versus k values (p = 0.202, R2 = 0.255) and Nres (p = 0.484, R2 = 0.0848). However, the regressions were not significant. While there appears to be a small relationship between roughness and k-values, in this study, the lack of statistical significance suggests that roughness does not provide predictive power for k values or Nres.

The materials which measured with higher Ra and Rz values, such as silicone rubber (Ra = 13.7 µm, Rz = 108.7 µm) and Porex (Ra = 19.84 µm, Rz = 100.01 µm), provide more surface area and microenvironments for biofilm attachment and formation. In contrast, materials like ABS (Ra = 3.26 µm, Rz = 22.8 µm) and stainless steel (Ra = 3.45 µm, Rz = 33.3 µm) have smoother surfaces, which can inhibit biofilm attachment due to the minimal surface texture. This is represented in this study as materials with higher roughness also resulted in higher maximum LRVs. Silicone (Ra = 13.69 µm) and Porex (Ra = 19.86 µm) were measured as the two roughest materials, but also demonstrated the first and third largest LRVs, 2.05 and 1.75 CFU/cm2, respectively. Furthermore, the modelled Nres for both silicone and porex, 1.86 and 1.75, were amongst the largest of the tested materials. This demonstrates that these materials have the potential to provide favourable conditions for microbial shielding, allowing for a larger resistant sub-population than the other tested materials.

However, this observation does not hold for all materials, for example, HDPE, which measured comparatively low on surface roughness (Ra = 4.63 µm, Rz = 45.89 µm) but exhibited a higher LRV (LRV max. = 1.17). This change could be attributed to additional surface characteristics of HDPE, such as zeta potential, less electrostatic repulsion or hydrophobicity55,56.

Other approaches to enhance biofilm inactivation with UV LEDs

Optimization of UV LED parameters, including wavelength, intensity, and exposure time, is crucial for maximizing biofilm inactivation across material types. Identifying surface characteristics such as roughness and reflectivity allows for the tailoring of UV LED inactivation processes to specific use cases. For instance, ABS required a fluence of 20 mJ/cm2 to achieve maximum inactivation, while PTFE and Viton® reached peak inactivation at 10 mJ/cm2. Understanding the differences between material types and their respective inactivation needs allows for only the required fluences to be applied.

These findings have practical implications for the selection of materials in applications requiring biofilm inactivation using UV LEDs. Materials like ABS, PTFE, and Porex, which show higher and rapid inactivation, are recommended for applications where quick and effective biofilm control is essential. Conversely, materials like HDPE and Polycarbonate, which exhibit lower inactivation rates, may require higher fluence or prolonged exposure for effective biofilm control. Further research is recommended to optimize UV LED parameters for each material to enhance inactivation efficiency. Ultimately, future work should investigate additional material types and the potential synergistic effects with other variables (e.g., light wavelength) to advance the possibilities of UV LED biofilm inactivation.

Conclusion

This study provides insights into the effectiveness of 280 nm UVC irradiation on P. aeruginosa biofilms grown on eight common plumbing materials and demonstrates that material properties influence biofilm formation and the effectiveness of UVC inactivation. Notably, materials such as Polycarbonate (k = 0.288 cm2/mJ), Silicone (k = 0.344 cm2/mJ), and Porex (k = 0.228 cm2/mJ) showed higher and more rapid inactivation rates, indicating their suitability for applications requiring efficient biofilm control. Conversely, materials like HDPE (k = 0.0636 cm2/mJ) and ABS (k = 0.0604 cm2/mJ) exhibited lower inactivation rates, suggesting a need for higher fluence or prolonged exposure to achieve similar inactivation levels. Additional analysis and investigation into the chemical characteristics of these materials would provide additional context in future work, as these characteristics may be impactful on direct UVC inactivation. These insights are relevant for industries and environments where biofilm formation poses challenges, including healthcare, shared spaces, and water treatment systems.

The results of this study contribute to a deeper understanding of biofilm behaviour under UVC exposure and provide valuable guidelines for selecting materials and optimizing inactivation processes to control biofilm formation effectively. As there is limited published research on direct irradiation of surface-bound biofilms, future research should focus on exploring additional microbial properties and environmental factors influencing biofilm dynamics to enhance the efficacy of inactivation protocols on a variety of materials.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded through support from an NSERC Alliance Grant [ALLRP 568507-2021] with the help of the following industry partners: Halifax Water, LuminUltra Technologies Ltd., Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Mantech Inc., City of Moncton, AquiSense Technologies, AGAT Laboratories, and CBCL Ltd.

Author contributions

T.J.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing original draft, review, and editing; S.A.M.: Conceptualization, Project administration, Visualization, Writing—review and editing; A.K.S.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition; G.A.G.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition.

Data availability

Data generated during this study will be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Linden, K. G., Hull, N. & Speight, V. Thinking outside the treatment plant: UV for water distribution system disinfection. Acc. Chem. Res.52, 1226–1233 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pousty, D. et al. Biofilm inactivation using LED systems emitting germicidal UV and antimicrobial blue light. Water Res.267, 122449 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray, K. E., Manitou-Alvarez, E. I., Inniss, E. C., Healy, F. G. & Bodour, A. A. Assessment of oxidative and UV-C treatments for inactivating bacterial biofilms from groundwater wells. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng.9, 39–49 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu, S. et al. Understanding, monitoring, and controlling biofilm growth in drinking water distribution systems. Environ. Sci. Technol.50, 8954–8976 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin, R., Cheng, J., Wang, J., Li, P. & Lin, J. Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infectious biofilms: Challenges and strategies. Front. Microbiol.13, 955286 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rattanakul, S. & Oguma, K. Inactivation kinetics and efficiencies of UV-LEDs against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Legionella pneumophila, and surrogate microorganisms. Water Res.130, 31–37 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gora, S. L., Rauch, K. D., Ontiveros, C. C., Stoddart, A. K. & Gagnon, G. A. Inactivation of biofilm-bound Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria using UVC light emitting diodes (UVC LEDs). Water Res.151, 193–202 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Lara Larrea, J., MacIsaac, S. A., Rauch, K. D., Stoddart, A. K. & Gagnon, G. A. Comparison of Legionella pneumophila and Pseudomonas fluorescens quantification methods for assessing UV LED disinfection. ACS EST Water3, 3667–3675 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iliadi, V. et al. Legionella pneumophila: The journey from the environment to the blood. J. Clin. Med.11, 6126 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuon, F. F., Dantas, L. R., Suss, P. H. & Tasca Ribeiro, V. S. Pathogenesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm: A review. Pathogens11, 300 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahto, K. U., Priyadarshanee, M., Samantaray, D. P. & Das, S. Bacterial biofilm and extracellular polymeric substances in the treatment of environmental pollutants: Beyond the protective role in survivability. J. Clean. Prod.379, 134759 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Hiyasat, A., Ma’ayeh, S., Hindiyeh, M. & Khader, Y. The presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the dental unit waterline systems of teaching clinics. Int. J. Dent. Hyg.5, 36–44 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waegenaar, F., García-Timermans, C., Van Landuyt, J., De Gusseme, B. & Boon, N. Impact of operational conditions on drinking water biofilm dynamics and coliform invasion potential. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.90, e00042-e124 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouhrour, N., Nibbering, P. H. & Bendali, F. Medical device-associated biofilm infections and multidrug-resistant pathogens. Pathogens13, 393 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemdan, B. A., El-Taweel, G. E., Goswami, P., Pant, D. & Sevda, S. The role of biofilm in the development and dissemination of ubiquitous pathogens in drinking water distribution systems: An overview of surveillance, outbreaks, and prevention. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.37, 36 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin, K., Struewing, I., Domingo, J., Lytle, D. & Lu, J. Opportunistic pathogens and microbial communities and their associations with sediment physical parameters in drinking water storage tank sediments. Pathogens6, 54 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh, A. et al. Bacterial biofilm infections, their resistance to antibiotics therapy and current treatment strategies. Biomed. Mater.17, 022003 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, H. et al. Effect of disinfectant, water age, and pipe material on occurrence and persistence of legionella, mycobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and two amoebas. Environ. Sci. Technol.46, 11566–11574 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma, B. et al. Inactivation of biofilm-bound bacterial cells using irradiation across UVC wavelengths. Water Res.217, 118379 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cullom, A. C. et al. Critical review: Propensity of premise plumbing pipe materials to enhance or diminish growth of legionella and other opportunistic pathogens. Pathogens9, 957 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proctor, C. R., Dai, D., Edwards, M. A. & Pruden, A. Interactive effects of temperature, organic carbon, and pipe material on microbiota composition and Legionella pneumophila in hot water plumbing systems. Microbiome5, 130 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fajobi, M. A., Loto, R. T. & Oluwole, O. O. Austenitic 316L stainless steel; corrosion and organic inhibitor: A review. Key Eng. Mater.886, 126–132 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nisticò, R. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in the packaging industry. Polym. Test.90, 106707 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oberoi, S. & Malik, M. Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), Chlorinated Polyethylene (CPE), Chlorinated Polyvinyl Chloride (CPVC), Chlorosulfonated Polyethylene (CSPE), Polychloroprene Rubber (CR)—Chemistry, Applications and Ecological Impacts—I. In Ecological and Health Effects of Building Materials (eds Malik, J. A. & Marathe, S.) 33–52 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner, A. & Filella, M. Polyvinyl chloride in consumer and environmental plastics, with a particular focus on metal-based additives. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts23, 1376–1384 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gohil, M. & Joshi, G. Perspective of polycarbonate composites and blends properties, applications, and future development: A review. In Green Sustainable Process for Chemical and Environmental Engineering and Science 393–424, Elsevier, (2022). 10.1016/B978-0-323-99643-3.00012-7.

- 27.Shit, S. C. & Shah, P. A review on silicone rubber. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett.36, 355–365 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck, S. E. et al. Wavelength dependent uv inactivation and dna damage of adenovirus as measured by cell culture infectivity and long range quantitative PCR. Environ. Sci. Technol.48, 591–598 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacIsaac, S. A. et al. Improved disinfection performance for 280 nm LEDs over 254 nm low-pressure UV lamps in community wastewater. Sci. Rep.13, 7576 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacIsaac, S. A. et al. UV LED wastewater disinfection: The future is upon us. Water Res. X24, 100236 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chatterley, C. & Linden, K. Demonstration and evaluation of germicidal UV-LEDs for point-of-use water disinfection. J. Water Health8, 479–486 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatterley, C. & Linden, K. G. UV-LED irradiation technology for point-of-use water disinfection. Proc. Water Environ. Fed.2009, 222–225 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azmin, A. et al. Ultraviolet Disinfection for Bio-Contaminated Surfaces with Image-Based Navigation. In: 2023 IEEE Symposium on Industrial Electronics & Applications (ISIEA) IEEE, (2023). 10.1109/ISIEA58478.2023.10212357.

- 34.Racchi, I., Scaramuzza, N., Hidalgo, A., Cigarini, M. & Berni, E. Sterilization of food packaging by UV-C irradiation: Is Aspergillus brasiliensis ATCC 16404 the best target microorganism for industrial bio-validations?. Int. J. Food Microbiol.357, 109383 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauch, K. D. et al. A critical review of ultra-violet light emitting diodes as a one water disinfection technology. Water Res. X10.1016/j.wroa.2024.100271 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos, T. D. & De Castro, L. F. Evaluation of a portable ultraviolet C (UV-C) device for hospital surface decontamination. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther.33, 102161 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gora, S. L. et al. Control of biofilms with UV light: A critical review of methodologies, research gaps, and future directions. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol.10.1039/D4EW00506F (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 38.BioSurface Technologies. CBR Operators Manual. (2020).

- 39.US Environmental Protection Agency & Office of Pesticide Programs. Standard Operating Procedure for Preparing a Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm using the CDC Biofilm Reactor. (2022).

- 40.Bolton, J. R. & Linden, K. G. Standardization of methods for fluence (UV dose) determination in bench-scale UV experiments. J. Environ. Eng.129, 209–215 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bohrerova, Z. & Linden, K. G. Assessment of DNA damage and repair in Mycobacterium terrae after exposure to UV irradiation. J. Appl. Microbiol.101, 995–1001 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ontiveros, C. C. et al. Assessing the impact of multiple ultraviolet disinfection cycles on N95 filtering facepiece respirator integrity. Sci. Rep.11, 12279 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimadzu Corporation. ISR-2600 for UV-2600/2700, ISR-2600Plus for UV-2600 Integrating Sphere Attachment. (2023).

- 44.Postit team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Postit Software, PBC (2024).

- 45.Marquenie, D. Combinations of pulsed white light and UV-C or mild heat treatment to inactivate conidia of Botrytis cinerea and Monilia fructigena. Int. J. Food Microbiol.85, 185–196 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nyhan, L., Przyjalgowski, M., Lewis, L., Begley, M. & Callanan, M. Investigating the use of ultraviolet light emitting diodes (UV-LEDs) for the inactivation of bacteria in powdered food ingredients. Foods10, 797 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rauch, K. D., MacIsaac, S. A., Stoddart, A. K. & Gagnon, G. A. UV disinfection audit of water resource recovery facilities identifies system and matrix limitations. J. Water Process Eng.50, 103167 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wen, D., Jiang, Y. & Chen, D. Evaluating disinfection performance of ultraviolet light-emitting diodes against the microalga Tetraselmis sp.: Assay methods, inactivation efficiencies, and action spectrum. Chemosphere308, 136113 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geeraerd, A. H., Herremans, C. H. & Impe, J. F. V. Structural model requirements to describe microbial inactivation during a mild heat treatment. Int. J. Food Microbial.59, 185–209 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li, W., Li, M., Bolton, J. R., Qu, J. & Qiang, Z. Impact of inner-wall reflection on UV reactor performance as evaluated by using computational fluid dynamics: The role of diffuse reflection. Water Res.109, 382–388 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma, B. et al. Reflection of UVC wavelengths from common materials during surface UV disinfection: Assessment of human UV exposure and ozone generation. Sci. Total Environ.869, 161848 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ammar, Y., Swailes, D., Bridgens, B. & Chen, J. Influence of surface roughness on the initial formation of biofilm. Surf. Coat. Technol.284, 410–416 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chinnaraj, S. B. et al. Modelling the combined effect of surface roughness and topography on bacterial attachment. J. Mater. Sci. Technol.81, 151–161 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franco, R., Rosa, A., Lupi, E. & Capogreco, M. The influence of dental implant roughness on biofilm formation: A comprehensive strategy. Dent. Hypotheses14, 90–92 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Amshawee, S. et al. Roughness and wettability of biofilm carriers: A systematic review. Environ. Technol. Innov.21, 101233 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang, L. et al. Biofilm retention on surfaces with variable roughness and hydrophobicity. Biofouling27, 111–121 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated during this study will be made available by the corresponding author upon request.