Abstract

Ammonia-starved cells of Nitrosomonas europaea are able to preserve a high level of ammonia-oxidizing activity in the absence of ammonium. However, when the nitrite-oxidizing cells that form part of the natural nitrifying community do not keep pace with the ammonia-oxidizing cells, nitrite accumulates and may subsequently inhibit ammonia oxidation. The maintenance of a high ammonia-oxidizing capacity during starvation is then nullified. In this study we demonstrated that cells of N. europaea starved for ammonia were not sensitive to nitrite, either when they were starved in the presence of nitrite or when nitrite was supplied simultaneously with fresh ammonium. In the latter case, the initial ammonia-oxidizing activity of starved cells was stimulated at least fivefold.

Chemolithotrophic nitrifying bacteria play an important role in the global nitrogen cycle by connecting the most reduced and oxidized parts of nitrogen. During the oxidation of ammonium by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, nitrite is formed as an end product that is further oxidized to nitrate by nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Under oxic conditions, chemolithotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria are entirely dependent on ammonium for the generation of energy. Under ammonium-limited conditions, the ammonia-oxidizing activity of cells of Nitrosomonas europaea is repressed by the presence of ammonium-assimilating heterotrophic bacteria and/or plant roots (16). Ammonium oxidation is also repressed in the field during the growing season of the wetland plant Glyceria maxima (2). Hence, ammonia-oxidizing bacteria have to withstand longer periods of ammonium starvation. To be able to profit quickly from the reappearance of fresh ammonium after a period of starvation, the population has to maintain a high ammonia-oxidizing potential. Pure cultures of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria are able to preserve their ammonia-oxidizing activities for several weeks. For example, cultures of Nitrosomonas cryotolerans starved for ammonia were able to maintain their cell densities and cellular compounds and started ammonia oxidation immediately upon addition of ammonia (7-9). Also, ammonia-starved cells of N. europaea responded immediately to addition of fresh substrate (18). The maintenance of a high ammonia-oxidizing capacity has also been demonstrated in mixed cultures of ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing species (4, 14). In mixed cultures, however, repression of ammonia oxidation occurred within the first few hours after addition of fresh ammonium to cells of N. europaea that had been incubated under ammonium-limited conditions for several weeks (4). Since the nitrite-oxidizing cells of Nitrobacter winogradskyi were not able to keep pace with the ammonia-oxidizing cells, nitrite accumulated after addition of fresh ammonium. It was hypothesized that the ammonia-oxidizing cells had been inhibited by the freshly produced nitrite. Stein and Arp (12) showed that the specific loss of ammonia-oxidizing activity in cells of N. europaea deprived of ammonium was due to toxicity of accumulated nitrite in the incubation medium.

Effect of the presence of nitrite during starvation.

To study the potential inhibition of ammonia oxidation by nitrite in cells that had been starved for ammonia for longer periods, cells of N. europaea strain ATCC 19781 were grown in nonshaken slurries containing 4 g of river sand in 20 ml of HEPES-buffered mineral medium at 26°C in the dark. The mineral medium contained (per liter) 330 mg of (NH4)2SO4, 585 mg of NaCl, 55 mg of KH2PO4, 49 mg of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 147 mg of CaCl2 · 2H2O, 75 mg of KCl, 10 g of HEPES, and 1 ml of trace elements solution, as described by Verhagen and Laanbroek (15). Bromothymol blue (3.2 mg/liter) was added from a 0.04% stock solution as a pH indicator. The pH was adjusted with 1 N NaOH to 7.7 before autoclaving. Before inoculation the sand slurries were autoclaved and cooled to room temperature. After 24 h, the slurries were decanted, fresh mineral medium was added, and the preparations were autoclaved again. Altogether, three cycles of autoclaving, cooling, and decanting were performed. Usually within 1 week after inoculation with N. europaea the ammonium was converted to nitrite, the sand slurries were decanted, and fresh mineral medium was added. This subculturing was repeated three times. The use of sand cultures facilitated the axenic replacement of spent medium by fresh medium without the loss of a large portion of the cells. On average, 8% of the medium remained in the culture after decanting. Samples used for determination of nitrite and nitrate contents were centrifuged at 15,000 × g with an EBA 12 table centrifuge for 10 min. Griess-Ilosvay analyses of nitrite in the supernatants of the cultures were performed immediately or within 24 h after transfer to −20°C.

Sand cultures of N. europaea that had been starved for 1, 2, and 3 months in their own spent medium (i.e., in the presence of 5 mM nitrite) were decanted, and fresh mineral medium containing 5 mM ammonium was added. The ammonium-starved cells started to produce nitrite immediately (Table 1). During accumulation of nitrite, no repression of ammonia-oxidizing activity was observed during the first 24 h of incubation. A decline in ammonia-oxidizing activity was occasionally observed during the second day of incubation, which was likely due to ammonium limitation in the culture. In a parallel experiment with the same original batch of sand cultures, the spent medium was replaced by fresh medium without inorganic nitrogen compounds at the start of the starvation period. After 1, 2, and 3 months of ammonium starvation in the absence of nitrite, the cultures received fresh medium with 5 mM ammonium. The potential ammonia-oxidizing activities were low compared to those observed in the experiment described above (Table 1). Again, no inhibition of ammonia-oxidizing activity was observed until ammonium had been exhausted after 6 days of incubation. When we compared the potential ammonia-oxidizing activities after starvation for ammonia in spent and fresh media, it appeared that 81 to 88% of the activity had been lost due to starvation of the cells in fresh medium without inorganic nitrogen compounds. According to an analysis of variance (Statistica software package, 99 edition; StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, Okla.), starvation time had no effect on the size of the ammonia-oxidizing potential after starvation (P = 0.47161, n = 3), whereas the starvation medium had an effect (P = 0.00003, n = 3). The presence of nitrite in fresh starvation medium had no effect on the maintenance of the ammonia-oxidizing potential (Table 2). Again, starvation in fresh medium had a significant (P < 0.05) negative effect on the level of the potential activity of starved cells. Under these conditions, 76% of the potential activity was lost on average when the cells were starved in fresh medium. Losses of cells during replacement of the medium could have been responsible for the differences in the levels of potential ammonia-oxidizing activities in spent and fresh media. The numbers of free and attached cells in sand cultures were determined by flow cytometry in a separate experiment. The average total numbers of cells in slurries prepared with cultures that had been starved in spent and fresh media and that were subsequently used to determine the remaining ammonia-oxidizing potential were 1.62 × 108 and 1.34 × 108, respectively. The difference in the number of cells (17%) is not large enough to explain the large differences in the observed potential ammonia-oxidizing activities of cells starved in spent and fresh media. Hence, replacement of spent medium by fresh medium at the onset of starvation seems to have diluted some unknown factor that had a positive effect on the maintenance of the ammonia-oxidizing potential. Such a factor might have been a homoserine lactone (1).

TABLE 1.

Potential ammonia-oxidizing activities of starved cells of N. europaea measured for 4 h after addition of fresh mineral medium with 5 mM ammonium

| Starvation conditions | Starvation period (mo) | Potential activity (nmol h−1 g [dry wt] of sand−1)a |

|---|---|---|

| Spent medium | 1 | 77 ± 18 |

| 2 | 66 ± 53 | |

| 3 | 37 ± 12 | |

| Fresh medium | 1 | 13 ± 4 |

| 2 | 8 ± 3 | |

| 3 | 7 ± 3 |

Means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

TABLE 2.

Potential ammonia-oxidizing activities of starved cells of N. europaea measured for 5 h after addition of fresh mineral medium with 5 mM ammonium

| Starvation conditions | Starvation period (wk) | Potential activity (nmol h−1 g [dry wt] of sand−1)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | 5 mM nitrite | ||

| Spent | + | 1 | 35 ± 2bb |

| Fresh | + | 1 | 7 ± 2a |

| Fresh | − | 1 | 10 ± 4a |

| Spent | + | 2 | 35 ± 14b |

| Fresh | + | 2 | 8 ± 5a |

| Fresh | − | 2 | 8 ± 3a |

Means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Different letters indicate that means are significantly different (P < 0.05), as determined by Tukey's honestly significant difference test.

Effect of the presence of nitrite during potential activity measurements.

After ammonium starvation for 4 months in spent medium containing 5 mM nitrite, all sand cultures were supplied with fresh medium containing 5 mM ammonium plus different combinations of nitrite, nitrate, and active nitrite-oxidizing cells of N. winogradskyi strain ATCC 25391, as indicated in Table 3. Nitrite and nitrate contents were determined by using high-pressure liquid chromatography as described by Bollmann and Laanbroek (3).

TABLE 3.

Potential ammonia-oxidizing activities of cells of N. europaea starved for ammonium for 4 months in spent medium

| Resuscitation medium supplement | Potential activity (nmol h−1 g [dry wt] of sand−1)a |

|---|---|

| Control | 27 ± 4ab |

| 5 mM nitrite | 141 ± 23c |

| 5 mM nitrite plus active N. winogradskyi | 131 ± 23c |

| Spent medium from N. winogradskyi culture | 20 ± 6a |

| 5 mM nitrate | 58 ± 13b |

Means ± standard deviations. Potential activities were determined for 5 h after addition of fresh mineral medium containing 5 mM ammonium supplemented with additional compounds.

Different letters indicate that means are significantly different (P < 0.05, n = 5), as determined by Tukey's honestly significant difference test. Data were log transformed to meet the criteria of normality and homogeneity of variances.

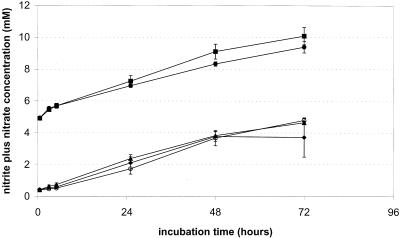

Sand cultures that had received 5 mM nitrite in addition to 5 mM ammonium exhibited high potential ammonia-oxidizing activities for 5 h irrespective of the presence of cells of N. winogradskyi (Table 3). Sand cultures that had received 5 mM nitrate also exhibited higher potential ammonia-oxidizing activities, although these activities were significantly lower than those of the sand cultures incubated with 5 mM nitrite in the medium. Sand cultures that had received spent medium from N. winogradskyi cultures exhibited the lowest potential activities during the first 5 h of incubation in the presence of ammonium. After the initial 5 h the nitrite production rates in the different sand cultures were similar over the next 19 h (Fig. 1). The potential ammonia-oxidizing activities shown in Table 3 were determined over the first 5 h of incubation after addition of fresh medium with ammonium. However, as Fig. 1 shows, the activities declined again after 3 h of incubation in the presence of 5 mM nitrite. Hence, the short-term effect of nitrite on the ammonia-oxidizing activity of ammonia-starved cells was even more pronounced than the effect shown in Table 3. As calculated from the observed nitrite and nitrate conversion rates, the nitrite-oxidizing activity of the cells of N. winogradskyi was 179 nmol of nitrite h−1 g (dry weight) of sand−1, which is well above the potential ammonia-oxidizing capacity of starved cells of N. europaea, as shown in Table 3.

FIG. 1.

Ammonia oxidation by cells of N. europaea starved for ammonium for 4 months in spent medium containing 5 mM nitrite. After starvation all sand cultures were decanted and supplied with fresh mineral medium containing 5 mM ammonium. Some cultures received in addition 5 mM nitrite (▪), 5 mM nitrite plus actively nitrite-oxidizing cells of N. winogradskyi (•), spent medium from an N. winogradskyi culture (○), or 5 mM nitrate (▴). Some cultures were supplied with only 5 mM ammonium and served as controls (⧫). The values are means based on the results obtained with five replicate cultures, and 95% confidence levels are indicated.

The assumed toxicity of nitrite for ammonia-starved cells of N. europaea was not observed in the experiments described above, either when nitrite was present in the starvation medium or when it was present in the resuscitation medium. On the contrary, nitrite stimulated the ammonia-oxidizing activity of starved cells during the first few hours after addition of fresh medium with 5 mM ammonium. Stimulation of ammonia oxidation by nitrite is difficult to explain based on the two-step mechanism of ammonia oxidation in which hydroxylamine is an intermediate product, as has been described for these chemolithotrophic bacteria (6). It is hard to imagine how the end product of the second step (nitrite) could stimulate the oxidation of ammonia. However, nitrite can be reduced to NO by the enzyme nitrite reductase. Nitrite reduction to NO has been shown to occur in N. europaea (5, 10, 11). Recently, Whittaker et al. (17) showed that the NirK component of the nitrite reductase system was present in N. europaea under oxic conditions. Also, the gene for NO reductase was present in the genome of this organism, but the genes for N2O and nitrate reductases were missing (17). Zart et al. (19) demonstrated that NO indirectly stimulates aerobic ammonium oxidation by Nitrosomonas eutropha. It was hypothesized that NO provides the cells with NO2 (or N2O4), which could act as the cosubstrate for the enzyme ammonia monooxygenase in the first step of chemolithotrophic ammonia oxidation. The postulated role of NO in the stimulation of aerobic ammonia oxidation could also be valid for the observed short-term stimulation of ammonia oxidation by nitrite in ammonia-starved cells in the experiments described here. The presence of nitrite during starvation apparently had no effect on the preservation of the ammonia-oxidizing potential.

The observed stimulation of ammonia oxidation by nitrite in N. europaea contradicts the results obtained by Stein and Arp (13) with cells of N. europaea. The most obvious explanation for the difference is the physiological condition of the cells in the two studies. Our observations were made with ammonia-starved cells, whereas Stein and Arp (13) used late-log-phase cells for their inhibition experiments.

Is stimulation of ammonia oxidation in ammonia-starved cells by nitrite also feasible in the natural environment? Due to their lack of competitive ability with respect to ammonium uptake, cells of N. europaea have to deal with periods of ammonium limitation or starvation (2, 16). Under oxic conditions, ammonium starvation also leads to nitrite starvation for the nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. When ammonium reappears in an oxic environment, no nitrite is available to be used as a stimulus for ammonia oxidation by starved cells. Hence, the results obtained with monocultures should be interpreted with care from an ecological point of view, but they may be helpful in understanding the metabolism of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, at least those belonging to the N. europaea-N. eutropha group.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bertus Beaumont, Annette Bollmann, Paul Bodelier, and Ingo Schmidt for valuable discussions. Paul Bodelier is also acknowledged for performing the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Publication 2893 of the NIOO-KNAW Centre for Limnology, Nieuwersluis, The Netherlands.

REFERENCES

- 1.Batchelor, S. E., M. Cooper, S. R. Chhabra, L. A. Glover, G. S. A. B. Stewart, P. Williams, and J. I. Prosser. 1997. Cell density-regulated recovery of starved biofilm populations of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2281-2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodelier, P. L. E., J. A. Libochant, C. W. P. M. Blom, and H. J. Laanbroek. 1996. Dynamics of nitrification and denitrification in root-oxygenated sediments and adaptation of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria to low oxygen or anoxic habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4100-4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bollmann, A., and H. J. Laanbroek. 2001. Continuous culture enrichments of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria at low ammonium concentrations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:211-221. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerards, S., H. Duyts, and H. J. Laanbroek. 1998. Ammonium-induced inhibition of ammonium-starved Nitrosomonas europaea cells in soil and sand slurries. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 26:269-280. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooper, A. B. 1968. A nitrite-reducing enzyme from Nitrosomonas europaea. Preliminary characterisation with hydroxylamine as electron donor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 162:49-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooper, A. B., T. Vannelli, D. J. Bergmann, and D. M. Arciero. 1997. Enzymology of the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite by bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 71:59-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnstone, B. H., and R. D. Jones. 1988. Physiological effects of long-term energy-source deprivation on the survival of a marine chemolithotrophic ammonium-oxidizing bacterium. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 49:295-303. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnstone, B. H., and R. D. Jones. 1988. Recovery of a marine chemolithotrophic ammonium-oxidizing bacterium from long-term energy-source deprivation. Can. J. Microbiol. 34:1347-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones, R. D., and R. Y. Morita. 1985. Survival of a marine ammonia oxidizer under energy-source deprivation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 26:175-179. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poth, M. 1986. Dinitrogen production from nitrite by a Nitrosomonas isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:957-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poth, M., and D. D. Focht. 1985. 15N kinetic analysis of N2O production by Nitrosomonas europaea: an examination of nitrifier nitrification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:1134-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein, L. Y., and D. J. Arp. 1998. Ammonium limitation results in the loss of ammonia-oxidizing activity in Nitrosomonas europaea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1514-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein, L. Y., and D. J. Arp. 1998. Loss of ammonia monooxygenase activity in Nitrosomonas europaea upon exposure to nitrite. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4098-4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tappe, W., A. Laverman, M. Bohland, M. Braster, S. Rittershaus, J. Groeneweg, and H. W. van Verseveld. 1999. Maintenance energy demand and starvation recovery dynamics of Nitrosomonas europaea and Nitrobacter winogradskyi cultivated in a retentostat with complete biomass retention. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2471-2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verhagen, F. J. M., and H. J. Laanbroek. 1991. Competition for ammonium between nitrifying and heterotrophic bacteria in energy-limited chemostats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:3255-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verhagen, F. J. M., H. J. Laanbroek, and J. W. Woldendorp. 1995. Competition for ammonium between nitrifying, heterotrophic bacteria and plant roots and effects of grazing by protozoa. Plant Soil 170:241-250. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittaker, M., D. Bergmann, D. Arciero, and A. B. Hooper. 2000. Electron transport during the oxidation of ammonia by the chemolithotrophic bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1459:346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilhelm, R., A. Abeliovich, and A. Nejidat. 1998. Effect of long-term ammonia starvation on the oxidation of ammonia and hydroxylamine by Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Biochem. 124:811-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zart, D., I. Schmidt, and E. Bock. 2000. Significance of gaseous NO for ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas eutropha. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 77:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]