Abstract

Background

Successful aging is one model of positive aging promoted among the older population, and represents an ideal aging scenario. It is important to understand what proportion of older adults are aging successfully and what factors influence it, to better support positive aging in the older population. Although aging is a global phenomenon, the Global South’s contribution to successful aging literature is very scant. Hence, this study was conducted in Nepal with the objective of finding the overall situation of successful aging and its predictors among older adults.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Kathmandu, Nepal. A total of 346 older adults aged 60 years and above were interviewed. Data related to successful aging, socio-demographic, and health-related characteristics were collected. Older adults with no major disease, no disability, no cognitive impairment, no physical problems, active social engagement, and spiritual well-being were considered successfully aging. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression were used to test the association of socio-demographic characteristics with successful aging.

Results

The prevalence of successful aging was found to be 29%. Age [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.90–0.99], living with a partner [(AOR = 3.09, CI = 1.17–8.17)], currently employed [AOR = 2.03, CI = 1.12–3.68] and performing daily physical activity [AOR = 3.01, CI = 1.08 − 8.33] were found to be associated with successful aging.

Conclusion

As increasing age was associated with lower odds of successful aging, older adults could be encouraged to maintain partnerships, engage in some form of employment or volunteer activities, and participate in physical activity to promote successful aging.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-025-06335-4.

Keywords: Positive aging, Successful aging, Healthy aging, Well-being, South Asia, Nepal

Background

In recent decades, there has been a notable increase in the global population of older adults, a trend marked by a rising number of people reaching their sixties and beyond [1]. Aging is a natural process occurring in all individuals and populations, involving gradual changes linked to the passage of time [2]. A decline in fertility and an increase in life expectancy have contributed to an upward trend in the population of older adults, accompanied by a continuous expansion in the percentage of older adults within the global population [3].

In 2025, the total count of individuals aged 60 and above is anticipated to be approximately 1.2 billion globally [1]. Although the percentage of older adults is high in high-income countries (HICs), the rate of aging is high in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), and in terms of crude numbers of older adults, LMICs surpass HICs. With more than 10% of the population being age 60 and above, Nepal—like many other LMICs—is already an aging society [4]. In Nepal, the 2021 census revealed that elders (60 + years) constituted 10.2% of the country’s population [4]. The population growth rate for older adults aged 60 and above in Nepal stands at 3.2% between 2011 and 2021, surpassing the overall population growth rate of 0.9% during the same time [4]. This growth rate suggests that Nepal has entered an aging society [4, 5].

As the population ages, it brings both challenges and opportunities. We have to focus more on opportunities and work on making sure our older population ages well. Aging well has been explained in various positive models of aging, such as successful aging, active aging, healthy aging, productive aging, and optimal aging. It is necessary to understand how the population is aging to plan any interventions or policies to promote positive aging. Very scant research has been conducted to understand the situation of positive aging in LMICs, especially in Nepal. Hence, we wanted to explore the situation of successful aging among the Nepali community. Successful aging is the earliest and most researched concept among positive aging models. We chose to study it to compare Nepal’s situation with the global context and identify its related factors. We know that the World Health Organization has promoted healthy aging as a model of positive aging, but it has also been criticized for being more biomedical. Similarly, successful aging has been criticized as well for not being fit for people with disabilities and relying on more health aspects. Nevertheless, as a starting point in the Nepalese context, we adopted Rowe and Kahn’s definition to determine the prevalence of successful aging among Nepali older adults.

Theoretical framework

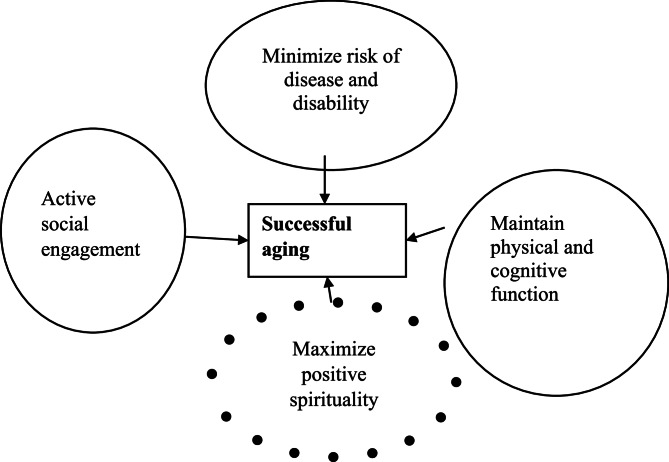

The concept of successful aging gained significant traction with the work of Rowe and Kahn (1997), who proposed a multidimensional model. It was characterized as exhibiting high cognitive and physical functionality, active participation in life, and the absence of disease and disability [6–9]. Their model shifted the focus from merely avoiding disease to maintaining physical, mental, and social well-being in later life. The model’s core components have become central to many definitions of successful aging, often serving as benchmarks in research and policy. However, critiques have emerged over time regarding the model’s limited inclusivity, especially its lack of attention to subjective experiences, psychological and spiritual dimensions [10]. This shift reflects a more holistic and individualized understanding of aging that values meaning and satisfaction alongside physical health. For instance, in many non-Western societies, aging is deeply intertwined with spirituality and community roles, which are not addressed in Rowe and Kahn’s original framework. Later in 2002, Crowther and the team suggested the addition of a spirituality aspect to enhance the model of Row and Kahn’s theoretical framework [10]. While Rowe and Kahn’s model of successful aging has its limitations, it has undeniably sparked a global conversation about how we can age well. By building on Rowe and Kahn’s work and incorporating spirituality as shown in Fig. 1, this paper aims to lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive and inclusive dialogue about successful aging in Nepal.

Fig. 1.

Model of successful aging

Methods

Study design and setting

A descriptive cross-sectional study design was conducted in Nepal during January 2024. Nepal is a landlocked country located in South Asia, occupying an area of 147,516 km2. Kathmandu district, the capital of Nepal, is located in the Bagmati province, with a mix of ethnic groups including Newars, Brahmins, Chhetris, and various indigenous communities. The city is a cultural and economic hub, blending traditional and modern lifestyles. Based on Census 2021, the total population of Nepal was 29,164,578, and the total population of older adults in the country was 2,970,000. The Kathmandu district was selected for the survey because it has the highest number of adults aged 60 and older, with a population of 174,057 [4]. Moreover, it has a heterogeneous population as people from all districts of the country reside in Kathmandu district.

Data collection

The data was collected from 346 older adults with a 96.1% response rate. Sample size was calculated using a formula, n = z2pq/e2 * d; where z is the standard normal variate (1.96) at 95% confidence interval, prevalence (p) = 0.11 [11], q (1-p) = 0.89, allowable error (e) = 0.05, and design effect (d) = 2 were used. As shown in Fig. 2, the sampling method was multistage sampling, which consisted of two stages. First, five of the eleven municipalities of Kathmandu district were selected randomly. Second, three wards from each municipality were selected using simple random sampling. The sampling frame was prepared by collecting information from each municipality and ward. The sampling frame contained information on municipality, ward number, block area (tole), name of the older adults, and contact number of them or their caretakers. A random sampling technique, i.e., the lottery method, was employed at the ward level. All persons above 60 years of age categorized by the Government of Nepal as senior citizens [12] of Kathmandu district were included in the sampling frame. Older adults from institutions or old-age care homes were not included. Moreover, older adults living in a nursing home, having a mental illness (such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with clinical evidence), being extremely sick that they were unable to respond, being deaf or hard of hearing, or being mute were excluded [13]. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with each participant to collect data and interviews were conducted in the Nepali language by the first author in their home. A questionnaire was developed that measured participants’ socio-demographic, health behaviors, and successful aging-related information. Successful aging was measured using various tools validated in the Nepali language, and these tools are described under the Measures section.

Fig. 2.

Sampling design flow chart

Measures

Dependent variable

Successful aging:

In this study, successful aging was defined through the concept of the Rowe and Kahn model of successful aging [8, 14] along with the inclusion of spiritual well-being [10]. Older adults with no major disease, no disability, no cognitive impairment, no physical problems, active social engagement, and spiritual well-being were considered successfully aging.

No major disease: Participants were asked if they had received a diagnosis from a doctor of any of the following conditions, which are leading causes of death for older adults: diabetes, cancer, heart disease, stroke, and chronic lung disease. Moreover, assessment of mental health was done by the 15-item Nepali version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15). The GDS-15 is a scale of 15 sets of questions with a total score of 15, with a cutoff value of less than six considered no depressive symptoms [15, 16]. The Cronbach’s alpha for GDS was 0.71, indicating a reliable tool for measuring depression. Participants who reported no diagnosis of the above-mentioned diseases and were not depressed were considered to have no major diseases.

Disability: The Barthel Index was used, which is a measurement tool used to assess a person’s performance in Activities of Daily Living (ADL). ADLs are basic self-care tasks that individuals typically perform without assistance, such as eating, bathing, dressing, transferring, and using the toilet. The Barthel Index assigns a score of 0–20 for each of these tasks (total range 0 to 100). A score of > 60 was deemed indicative of a good functional status, meaning that the individual can execute daily duties independently, and those older adults were considered not to have a disability. However, a score of ≤ 60 denotes a bad functional status, meaning that the individual needs more assistance to complete everyday tasks [13, 14, 17]. This study calculated the reliability of Barthel’s Index with Cronbach’s alpha, which was found to be 0.91, indicating a highly reliable tool for measuring ADLs.

Cognitive functioning: The Cognitive functioning of the participants was measured using a quick cognitive screening tool with good psychometric qualities, the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS). RUDAS has been found to be a more valid and dependable instrument for evaluating cognitive function in the Nepali population and is especially helpful for groups that are culturally and linguistically diverse [18]. The six-item RUDAS cognitive evaluation instrument has a total score of 30, and a cutoff value greater than 23 indicates good cognitive functioning [19].

Physical functioning: If an individual did not have more than one problem on completing any of the seven assessments—which included walking 100 m, walking 200 m, climbing one flight of stairs, climbing several flights of stairs, lifting or carrying objects weighing more than 5 kg, stooping, kneeling, or crouching, and pulling or pushing large objects—they were considered to have high physical functioning [14].

Active engagement: Rowe and Kahn’s notion of active engagement suggests social connections and engagement in productive activity [8, 9]. Participants were defined as “actively engaged” if they reported performing two or more of these activities such as any volunteer work in past month, engaged in any groups or clubs, taking care of grandchildren at current time, socializing with friends and neighbors once a week, engaged in cultural or religious activities once a month, and monthly contact with non-cohabiting family and relatives.

Spiritual well-being: The Spirituality Index of Wellbeing scale (SIWB) was used to assess spirituality among older adults [20]. The tool was translated into the Nepali language, which contained 12-items divided into two subscales: (a) self-efficacy subscale and (b) life-scheme subscale. Each item was measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 5 (Strongly Disagree). A median score or above in both subscales was considered good spiritual well-being. The Cronbach’s alpha for SWIB in this study was 0.81.

Independent variables

Age was measured in completed years, and sex was categorized into male and female. Likewise, ethnicity was categorized as Brahmin/Chhetri, Dalit, Janajati, and Newar. Moreover, education was categorized into “Illiterate”, “Informal education”, “Basic level (1–8)”, “Secondary level (9–12)”, and “Bachelor’s and above”. Occupations were categorized as not working, agriculture, private or government jobs, business, skilled or unskilled labor and others. However, for the regression analysis occupation was recategorized as currently employed and unemployed. Partnership or marital status was dichotomized into “partnered/married” and “not in partnership/without partner.” Older adults those unmarried, widow, separated, and divorced were categorized as without a partner. The total amount of the family’s monthly income in Nepali rupees was reported. Income data were converted in thousands for regression analysis. The amount of sleep was assessed based on the duration of sleep, at least 8 h and less than 8 h. Physical activity was categorized as regularly, sometimes, and never. Use of assistive devices such as hearing aids, crutches, a tripod, a wheelchair, etc. was recorded as “yes” and “no” if not used.

Data management and analysis

The questionnaire was reviewed for completeness at the time of data collection. Data was collected using the Kobo toolbox and analyzed in SPSS v 23. Quantitative data were expressed in the form of frequency and percentage. Using logistic regression, we performed bivariate and multivariable analyses to observe the association of independent variables with successful aging, including the individual’s sociodemographic characteristics, and health behaviors. Crude odds ratio (COR) and adjusted odds ratio (AOR) were reported from binary logistic regression and multivariable logistic regression, respectively. Furthermore, findings were reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI) along with COR and AOR. Multivariable analysis was conducted using independent variables, those found to be p-value < 0.25 in bivariate analysis, and key factors identified in the literature study [21]. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to assess the multicollinearity of the variables. The maximum VIF of 1.60 indicated that there was no issue with multicollinearity. Statistical testing was done on a 95% significance level, where a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Distribution of participants by their sociodemographic, socioeconomic and health behavioral characteristic

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of the participants were male (54.9%), and respondents’ age ranged from 60 to 92 years, with a mean of 70.6 and a standard deviation of 7.3 years. Majority of participants were Brahamin/Chhetri with 49.4%. Moreover, most of them were illiterate (45.4%), and only 3.5% had a bachelor’s and higher level of education. More than two-thirds (75.1%) of the participants were married/partnered, 44.5% were not working and 18.8% were unable to work. Among those who were engaged in occupation, 19.4% were involved in business.

Table 1.

Descriptive findings of study participants (n = 346)

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 70.6 ± 7.3 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 190 | 54.9 |

| Female | 156 | 45.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Brahamin/Chhetri | 171 | 49.4 |

| Dalit | 5 | 1.4 |

| Newar | 111 | 32.1 |

| Janajati | 59 | 17.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| With partner | 260 | 75.1 |

| Without partner | 86 | 24.9 |

| Educational status | ||

| Illiterate | 157 | 45.4 |

| Informal education | 112 | 32.4 |

| Basic (1–8) | 43 | 12.4 |

| Secondary (9–12) | 22 | 6.4 |

| Bachelors and above | 12 | 3.5 |

| Employment | ||

| None | 154 | 44.5 |

| Unable to work | 65 | 18.8 |

| Job | 27 | 7.8 |

| Agriculture | 7 | 2.0 |

| Labor | 11 | 3.2 |

| Business | 67 | 19.4 |

| Retirement | 15 | 4.3 |

| Family income (Mean ± SD) | 60,196.5 ± 37,988 | |

| Sleeping hours | ||

| At least 8 h | 133 | 38.4 |

| Less than 8 h | 213 | 61.6 |

| Physical activity | ||

| Regular | 185 | 53.5 |

| Sometimes | 108 | 31.2 |

| Never | 53 | 15.3 |

| Assistive devices | ||

| Yes | 81 | 23.4 |

| No | 265 | 76.6 |

Only 38.4% of older adults had at least 8 h of sleep. Most respondents had regular physical activity with 53.5% and only 23.4% of the respondents were using assistive devices like eyeglasses, wheelchairs, walking sticks, etc.

Prevalence of successful aging and major themes

Table 2 shows the prevalence of successful aging, which was assessed using six major themes. The prevalence of successful aging was 28.9% with a CI of 24.2–34.0. Almost half of the participants had no major diseases (49.1%), 98.6% had no disability, 74.9% had high cognitive functioning, 56.1% had high physical functioning, 99.4% had active engagement in social lives and 61.8% had good spiritual well-being.

Table 2.

Prevalence within each subcomponent of successful aging (n = 346)

| Major theme | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No major diseases | 170 | 49.1 | |

| No disability | 341 | 98.6 | |

| High cognitive functioning | 259 | 74.9 | |

| High physical functioning | 194 | 56.1 | |

| Good social engagement | 344 | 99.4 | |

| Good spiritual well-being | 214 | 61.8 | |

| Successful ageing | 100 | 28.9 | |

Successful aging and its factors

Table 3 describes the association of covariates with successful aging. From the bivariate analysis, the variables such as age, sex, marital status, education status, employment status, sleeping hours and physical activity had a statistically significant association with successful aging. After controlling for the variables, older adults’ age, marital status, employment status and physical activity were found to be associated with successful aging. With each one-year increase in age, the odds of respondents being successfully aged decrease by 6% [AOR 0.94, 95% CI 0.90–0.99]. The odds of successfully aging were 3.09 times higher among married or partnered respondents [95% CI 1.17–8.17] as compared to those without partners. Respondents with current employment status were 2-times more likely to be successful agers [95% CI 1.12–3.68] than unemployed respondents. This study also found that those respondents who performed physical activities regularly had a higher chance of successful aging (AOR 3.01, 95% CI 1.08–8.33) compared to those who never did physical exercise. Moreover, gender specific analysis showed that the association of age with successful aging was statistically significant for males only [Additional file 1]. Likewise, females had statistically significant higher odds of successful aging if they were married and employed. Furthermore, males had higher odds of successful aging when doing physical activity, and females did not have a statistically significant relationship with physical activity.

Table 3.

Association of covariates with successful aging

| Variables | Unadjusted (COR) | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted (AOR) | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.90 | 0.86–0.3 | 0.001 | 0.94 | 0.90–0.99 | 0.032* |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.91 | 1.17–3.09 | 0.009 | 1.33 | 0.73–2.4 | 0.338 |

| Female | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Brahamin/Chhetri | 1.12 | 0.65–1.93 | 0.675 | 0.83 | 0.438–1.58 | 0.577 |

| Janajati and Dalit | 1.90 | 0.98–3.67 | 0.057 | 1.59 | 0.73–3.46 | 0.237 |

| Newar | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Marital status | – | – | ||||

| Living with Partner | 7.5 | 3.17–17.97 | 0.001 | 3.09 | 1.17–8.17 | 0.023* |

| Living without Partner | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Educational status | ||||||

| Literate | 2.65 | 1.61–4.37 | 0.001 | 1.16 | 0.60–2.24 | 0.648 |

| Illiterate | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 3.1 | 1.93–5.13 | 0.001 | 2.03 | 1.12–3.68 | 0.020* |

| Unemployed | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Family income (in thousand) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.869 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.265 |

| Sleeping hours | ||||||

| At least 8 h | 2.34 | 1.45–3.76 | 0.001 | 1.46 | 0.84–2.54 | 0.174 |

| Less than 8 h | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Always | 5.34 | 2.17–13.12 | 0.001 | 3.01 | 1.08–8.33 | 0.034* |

| Sometimes | 1.67 | 0.625–4.47 | 0.306 | 1.35 | 0.46–3.93 | 0.580 |

| Never | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Assistive devices | ||||||

| Yes | 0.89 | 0.51–1.55 | 0.693 | 1.06 | 0.55–2.03 | 0.859 |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||

Hosmer Lemeshow Chi-square value = 0.741, Negelkerke (pseudo) R2 = 0.272

AOR Adjusted Odds Ratio, COR Crude Odds Ratio, CI Confidence Interval

*=Statistically significant at 95% CI

Discussion

The objective of the study was to find out the prevalence of successful aging among Nepali older adults and the factors associated with it. The findings showed that more than one-fourth (29%) of the respondents were successful agers. After controlling for the variables, lower age, living with a partner, being currently employed, and performing daily physical activity were found to be associated with successful aging.

This finding of the prevalence of successful aging in our study is similar to the various studies conducted in Brazil, China and Thailand that showed the rates of successful aging of 25%, 39% and 24%, respectively [22]. Similarly, a study conducted in Singapore using Rowe and Kahn’s definition of successful aging revealed the prevalence of successful aging at 25.4% [23]. These findings are higher than the studies conducted in Indonesia (6.8%) [24], Korea (13.3%) [25] and Palestine (22.2%) [26]. Whereas, the prevalence was higher in the study conducted in European countries like Austria (58.3%), followed by Switzerland (51.2%), Germany (37.6%), and France (36.7%) [27]. These observed discrepancies may be the result of cultural differences as well as study design factors like sample size and successful aging metrics. Various factors like age, gender, and educational attainment caused variations in the frequency of SA among older persons across different nations. Additionally, the methods of participant selection, cut-off points, and the instruments used to identify SA all affect the prevalence rates [26]. This study incorporates positive spiritual well-being [10, 23] which makes it more holistic from all dimensions to be assessed for SA. In this study, active social engagement was the most predominant subdomain, with 99.9% of the older adults having it. On the other hand, the absence of major diseases was the least.

In the bivariate analysis, age, sex, marriage, education, employment, sleeping hours, and physical activity of respondents were associated with successful aging. After adjusting for all possible covariates, age, marital status, employment status and physical activity were associated with successful aging. This study’s findings of a negative association between age and successful aging mean that the chance of successful aging decreases as age increases. These findings were similar to the study conducted in Thailand [28] and Indonesia [24]. The physiologic, functional, and cognitive deterioration that occurs with aging accounts for the expected negative correlation between age and SA. However, aging is not a risk factor or a medical condition but a lifelong accumulation of social, economic, and health-related influences [29]. As a result of cumulative disadvantages, older age consistently corresponds to higher disability and morbidity [29]. For example, an individual’s risk of developing chronic conditions like heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, and osteoporosis increases with age [24, 30]. Moreover, gender-specific analysis demonstrate that increasing age is significantly associated with lower odds of successful aging among males, but not among females, suggesting that men may be more vulnerable to the negative impacts of aging on well-being or functional status.

This study illustrates that older adults who were engaged in any employment have a higher chance of becoming successful agers, similar to the findings of the studies conducted in European countries [31] and Indonesia [24]. By engaging in productive work, older adults sustain a sufficient income to cover their everyday expenses, encompassing continuously rising medical costs and healthcare requirements [32]. Moreover, employment maintains the social connection with their friends, and this connection works as a protective factor for the development of chronic diseases or disabilities [33]. On the other hand, it is also possible that those who are non-disabled, without chronic diseases and of sound mental capacity, are more likely to work, and hence, there could be bidirectional relationships between successful aging and work and employment [33].

In terms of marital status, older individuals who lack a partner face a decreased likelihood of experiencing successful aging compared to those who are living with their partners. Having a spouse offers assistance for social engagement and boosts self-esteem. Spouses play a crucial role in providing support, as evidenced by reduced life satisfaction observed after the death of a spouse, particularly among men [24]. This study showed [see Additional file 1] that marital status and employment were particularly salient predictors for women: females who were married or employed had significantly higher odds of successful aging, whereas these factors were less influential for their male counterparts. This may reflect the unique social and economic roles that marriage and employment play in women’s lives, possibly offering greater social support or financial security that mitigates age-related challenges. The presence of a spouse positively affects longevity and promotes healthy aging due to enhanced companionship and partner support [25, 34]. There is a potential gap to understand how gender interacts with the successful aging among Nepali older adults.

This study finds a positive association between physical activity and successful aging. Those respondents who were performing regular physical activities were more likely to have a successful aging, which coincides with the findings from a study conducted in India [11]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the beneficial impact of physical activity on middle-aged and older persons’ ability to age well [35]. Physical activity possesses the ability to partially counteract the impacts of aging on physiological functions partially and to maintain existing functional capacities in older adults [36]. The correlation between physical activity and successful aging appears quite evident; increased physical activity directly enhances health, while lack of activity can result in a decline in muscle, bone, and circulatory system. Moreover, physical activity and health may indirectly influence improved mental well-being and feelings of life fulfillment [37, 38]. Interestingly, regular physical activity was strongly associated with successful aging among men, but not women, indicating that men may derive greater physical or psychological benefits from exercise in later life, or that barriers to physical activity for women may attenuate its impact.

Strengths and limitations of the study

As far as we are aware, this is the first study in Nepal to find out the successful aging among the older population in Nepal using the Rowe and Kahn’s model of successful aging. In addition, incorporating the spirituality aspects and setting a benchmark for a similar study that will be conducted in the future is a major strength of this study. This study was conducted using tools that are validated in the Nepali language. A notable strength of this study is its gender-specific analysis, which reveals important differences in the predictors of successful aging between men and women. These gender-specific findings signifies the importance of considering gender as a moderator in successful aging research.

This study has a few limitations as well. This study did not include older people who live in old age homes/institutions and older adults with profound disability, which potentially led to coverage error. The study’s self-reported findings could have been influenced by recall and social desirability biases. Likewise, cross-sectional analysis does not give causal inference but provides an association. Similarly, the study was focused on Kathmandu district where various ethnic groups reside, but still generalizing the findings to overall Nepal need caution. As multistage sampling was performed to select samples, and multilevel modeling is preferred for this kind of sampling, however, our study area was only one district, and there was not much variation in ethnicity and socio-economic status among the selected wards, we performed binary logistic regression. As the study aimed to explore socio-demographic and behavioral factors associated with successful aging, those with severe disability were excluded from the sampling. The reported prevalence rate of successful aging could be lower if older adults with severe disability had been incorporated into the study. Rowe and Kahn’s model has been extensively used in terms of defining and quantifying successful aging objectively; however, the model has been criticized for not being feasible for those with severe disability and presuming that those people will never age successfully. This binary perspective fails to recognize the diversity of aging experiences and may overlook the strengths and adaptive capacities of older adults who live with chronic conditions or functional limitations. In contrast, alternative models of aging emphasize resilience, adaptability, and the ability to find fulfillment and maintain independence despite the presence of health challenges.

Nevertheless, this study represents the first step in researching successful aging in Nepal. This study will be a building block to initiate the conversation about successful aging and how to redefine it within the Nepali context. Moving forward, it will be important to develop a more inclusive and subjective framework for successful aging that considers the diverse cultural, social, and personal factors relevant to older adults in Nepal. Qualitative research that explores the lived experiences and perspectives of older adults can provide valuable insights into what they view as successful aging. Furthermore, longitudinal or interventional studies are needed to establish causal relationships between various determinants and outcomes of successful aging. These approaches will enhance our understanding and guide the development of culturally appropriate interventions and policies that promote positive aging experiences among Nepal’s older population.

Conclusion

This study provides the prevalence of successful aging and the associated factors that support successful aging in the Nepali context. More than one in four older adults above the age of 60 years were successfully aging. This study highlights the importance of living with their partners, engaging in physical activities, and having employment opportunities to determine successful aging. Marital or partnership status, regular physical activities, and creating employment opportunities during old age could enhance successful aging; hence, longitudinal studies should be conducted to establish causality and advise policy. This study is the benchmark for starting the discussion about positive aging focused on successful aging among Nepali older adults and warrants more research and discussion about successful aging with Nepali socio-cultural perspectives.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to our research participants, the authorities who allowed us to conduct our study, and the teachers who guided us.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of Daily Living

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- GDS

Geriatric Depression Scale

- HICs

High-income countries

- LMICs

Low-and middle-income countries

- RUDAS

Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale

- SA

Successful aging

- SIWB

Spirituality Index of Wellbeing scale

- VIF

Variance inflation factor

Authors’ contributions

PK and KPS conceptualized the research idea. PK designed the study, collected and managed the data, performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. PK and KPS were major contributors to writing the manuscript. PK, PSP, KPS, BKS and AB critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sigma Xi Grants-in-Aid of Research Award (G20230315-5122) and the Academy for Data Science and Global Health. The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for undertaking the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of the Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University (Ref: 291 − 080/081) on Dec 21, 2023. Before beginning the study, permission was obtained from the relevant municipal administration after the researcher provided them with a detailed explanation of the study’s objective. Before beginning the interview, participants were informed of the risks and benefits, of participating in the study along with voluntary participation. Afterwards, informed written consents were obtained from all respondents. Interviews were conducted in an open space at respondents’ convenience, mostly in their homes. Data was anonymized and kept secure in the folder with password protection. Respondent’s anonymity was maintained throughout the research process. This study adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Ageing and health. 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- 2.Venes D, Thomas CL, Taber CW, editors. Taber’s cyclopedic medical dictionary. Philadelphia: F.A.Davis Co; 2001. p. 2654. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh ML. Aspects of ageing. Population Monograph of Nepal. Vol. II (Social Demography). Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics; 2014. p. 73–107.

- 4.Sapkota KP, Shrestha A, Brown JS. The demographic context of aging in Nepal. In: Tausig M, Subedi J, Ghimire S, editors. Population aging in societal context. London: Routledge; 2025. pp. 23–37. 10.4324/9781003618843-4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shrestha S, Aro AR, Shrestha B, Thapa S. Elderly care in Nepal: are existing health and community support systems enough. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9: 205031212110663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alley DE, Putney NM, Rice M, Bengtson VL. The increasing use of theory in social gerontology: 1990–2004. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B(5):583–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lupien SJ, Wan N. Successful ageing: from cell to self. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1449):1413–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Human aging: usual and successful. Science. 1987;237(4811):143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997;37(4):433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowther MR, Parker MW, Achenbaum WA, Larimore WL, Koenig HG. Rowe and kahn’s model of successful aging revisited: positive Spirituality—The forgotten factor. Gerontologist. 2002;42(5):613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Successful ageing among a national community-dwelling sample of older adults in India in 2017–2018. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1): 22186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Government of Nepal. Senior Citizen Act, 2063. 2006. Available from: www.lawcommission.gov.np.

- 13.Ghimire S, Paudel G, Mistry SK, Parvez M, Rayamajhee B, Paudel P, et al. Functional status and its associated factors among community-dwelling older adults in rural Nepal: findings from a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin SJ, Connell CM, Heeringa SG, Li LW, Roberts JS. Successful aging in the united states: prevalence estimates from a National sample of older adults. J Gerontol Ser B. 2010;65B(2):216–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg SA. How to try this: The Geriatric Depression Scale: Short Form. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(10):60–9. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000292204.52313.f3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Risal A, Giri E, Shrestha O, Manandhar S, Kunwar D, Amatya R, et al. Nepali Version of Geriatric Depression Scale-15 - A Reliability and Validation Study. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2020;17(4):506-11. 10.33314/jnhrc.v17i4.1984. PMID: 32001857 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:56–6. [PubMed]

- 18.Nepal GM, Shrestha A, Acharya R. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Nepali version of the Rowland universal dementia assessment scale (RUDAS). J Patient-Rep Outcomes. 2019;3(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storey JE, Rowland JTJ, Basic D, Conforti DA, Dickson HG. The Rowland universal dementia assessment scale (RUDAS): a multicultural cognitive assessment scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16(1):13–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daaleman TP, Frey BB. The spirituality index of well-being: a new instrument for health-related quality-of-life research. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. Third edition. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley; 2013. 500 p. (Wiley series in probability and statistics).

- 22.Susanti I, Latuperissa gr, Soulissa FF, Fauziah A, Sukartini T, Indarwati R, Aris A. The factors associated with successful aging in elderly: a systematic review. J Ners. 2020. 10.20473/jn.v15i1Sp.19019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vaingankar J, Sambasivam R, Seow E, Picco L, et al. Successful ageing in Singapore: prevalence and correlates from a national survey of older adults. Singapore Med J. 2019;60(1):22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulfa L, Sartika RAD. Risk factors and changes in successful aging among older individuals in Indonesia. Malays J Public Health Med. 2019;19(1):126–33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang HY. Factors associated with successful aging among community-dwelling older adults based on ecological system model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9): 3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badrasawi M, Samuh M, Khallaf M, Abuqamar M. Successful aging among community-dwelling Palestinian older adults: prevalence and association with sociodemographic characteristics, health, and nutritional status. Indian J Public Health. 2020;64(3):271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schietzel S, Chocano-Bedoya PO, Sadlon A, Gagesch M, Willett WC, Orav EJ, et al. Prevalence of healthy aging among community dwelling adults age 70 and older from five European countries. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1): 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anantanasuwong D, Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Prevalence and associated factors of successful ageing among people 50 years and older in a national community sample in Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17): 10705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrestha A, Sapkota KP, Karmacharya I, Tuladhar L, Bhattarai P, Bhattarai P, et al. Chronic morbidity levels and associated factors among older adults in Western Nepal: a cross-sectional study. J Multimorb Comorb. 2025;15: 26335565251325920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosch-Farré C, Garre-Olmo J, Bonmatí-Tomàs A, Malagón-Aguilera MC, Gelabert-Vilella S, Fuentes-Pumarola C, et al. Prevalence and related factors of active and healthy ageing in Europe according to two models: results from the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE). PLoS One. 2018;13(10): e0206353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jang SN, Choi YJ, Kim DH. Association of socioeconomic status with successful ageing: differences in the components of successful ageing. J Biosoc Sci. 2009;41(2):207–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamichhane K. Employment situation and life changes for people with disabilities: evidence from Nepal. Disabil Soc. 2012;27(4):471–85. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rattanapun S, Fongkeaw W, Chontawan R, Panuthai S, Wesumperuma D. Characteristics of healthy ageing among the elderly in Southern Thailand. CMU J Nat Sci. 2009;8(2):143–60.

- 35.Lin YH, Chen YC, Tseng YC, Tsai S, tzu, Tseng YH. Physical activity and successful aging among middle-aged and older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Aging. 2020;12(9):7704–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Södergren M. Lifestyle predictors of healthy ageing in men. Maturitas. 2013;75(2):113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carr K, Weir PL. A qualitative description of successful aging through different decades of older adulthood. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(12):1317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmore E. Predictors of successful aging. Gerontologist. 1979;19(5 Pt 1). 10.1093/geront/19.5_Part_1.427. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.