Abstract

Wilms’ tumor (WT1), a transcription factor highly expressed in various leukemias and solid tumors, is a highly specific intracellular tumor antigen, requiring presentation through complexation with HLA-restricted peptides.. WT1-derived epitopes are able to assemble with MHC-I and thereby be recognized by T cell receptors (TCR). Identification of new targetable epitopes derived from WT1 on solid tumors is a challenge, but meaningful for the development of therapeutics that could in this way target intracellular oncogenic proteins. In this study, we developed and comprehensively describe methods to validate the formation of the complex of WT1126–134 and HLA-A2. Subsequently, we developed an antibody fragment able to recognize the extracellular complex on the surface of cancer cells. The single chain variable fragment (scFv) of an established TCR-mimic antibody, specifically recognizing the WT1-derived peptide presented by the HLA-A2 complex, was expressed, purified, and functionally validated using a T2 cell antigen presentation model. Furthermore, we evaluated the potential of the WT1-derived peptide as a targetable extracellular antigen in multiple solid tumor cell lines. Our study describes methodology for the evaluation of WT1-derived peptides as tumor-specific antigen on solid tumors, and may facilitate the selection of potential candidates for future immunotherapy targeting WT1 epitopes.

Keywords: WT-1, HLA-A2, Intracellular peptide, Antibody, Cancer

1. Introduction

Though the tendency for expression of certain antigens on tumor cells over normal host cells has enabled the development of targeted immunotherapies which have led to approvals for novel therapeutic classes such as gene-modified T cells and checkpoint inhibitors, the lack of specificity for many of the commonly targeted tumor antigens remains a challenge.

Unlike tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), tumor-specific antigens (TSAs), also referred to as neoantigens, are endogenously expressed only on tumor cells, and thus have much higher specificity [1]. They are also present in low abundance on tumors cells and are, as such, much more elusive. Efforts at identifying targetable TSAs have been extensive [2,3].

Among immunogenic, differentially-expressed antigens which elicit specific immune responses and are required for tumor cell survival is Wilms’ tumor gene 1 (WT1), a transcription factor expressed in high levels in various leukemias and solid tumors [4]. Studies have shown that T cells specific for peptide products of WT1 are able to target WT1+ tumors and elicit anti-tumor responses [5,6]. Those peptides which have been able to elicit anti-tumor immune responses have been incorporated into vaccines, some of which have been evaluated clinically, [7] or have been targeted with WT1-specific T cell receptor (TCR) cells [8].

Since WT1 is an intracellular protein and thus inaccessible to targeting by monoclonal antibody therapy, the requirement to generate WT1-specific cell-based therapies that recognize peptides presented extracellularly by MHC class I molecules has been a major challenge for WT1-targeted therapies. WT1 peptides have been mostly developed based on epitopes presented by HLA-A*02:01, presenting peptide WT1 235–243 (CMTW), and HLA-A*24:02 presenting peptide WT1 235–243 (CMTW).[9] Although development of a wider array of HLA alleles is being investigated to broaden the pool of the potentially accessible patient population, the ability to target HLA-binding WT1 with cell therapy remains with numerous unexplored avenues. Part of this stems from the paucity of studies investigating WT1-HLA complexes in tumors, and the scarcity of tools targeting the same.

Here, we present a comprehensive method to develop a WT1-specific antibody targeting the HLA-A*0201-binding WT1(126–134) peptide as an actionable antibody fragment (scFv) targeting cells expressing this complex, and the development of a T2 cell-based antigen presentation model. Through sequence selection, expression, and purification, we outline a robust method to generate WT1-targeting antibody fragments and evaluate their binding on various tumor cells. Interestingly, although T2-pulsed cells show consistent binding to the WT1-peptide complex, most cancer cell lines tested failed to elicit binding responses to the peptide.

Our study serves not only as a resource for the optimized generation of WT1-specific scFv which can potentially be incorporated into various cancer-targeting architectures – including chimeric antigen receptors – but also as a reference to the potential of WT1-presented peptide complex in many common cancer cell lines.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

DMEM with high glucose, RPMI-1640, ExpiCHO expression medium, GlutaMAX, trypsin/EDTA solution, and penicillin and streptomycin were purchased from Gibco (New York, NY, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Corning (New York, NY, USA). FectoPRO transfection reagents were purchased from PolyPlus (Graffenstaden, France). Alexa Fluro 680-conjugated anti-huma WT1 antibody (F-6) (catalog: sc-7385 AF680) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Antibodies including FITC conjugated anti-human HLA-A2 antibody (clone BB7.2), APC-conjugated-anti-His tag antibody (clone J095G46), HRP-conjugated anti-His tag antibody (clone J099B12) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Recombinant human β2 microglobulin (β2M), Cytofix/Cytoperm solution and Perm/Wash buffer for intracellular staining were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Peptides (RMFPNAPYL, abbreviated RMF, and ILSLELMKL, abbreviated ILS) were synthesized by GenScript biotech (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). PureLink HiPure plasmid maxiprep kit, Qubit dsDNA BR assay kit, Qubit protein assay kit, pierce ECL western blotting substrate, HisPur Ni-NTA spin columns, pierce protein concentrators PES with 10 K MWCO, and SYTOX blue dead cell stain were purchased from Thermo fisher scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). 4XLoading buffer, PVDF membrane were purchased from BioRad (Hercules, CA, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA), unless specifically noted otherwise.

2.2. Cell lines

Human T2 cells, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), were cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) supplemented with 20 % (v/v) FBS. The human erythroleukemic cell line K562 was obtained from ATCC and maintained in IMDM medium supplemented with 10 % FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Human patient-derived glioblastoma cell line GBM43 cell, Uppsala 87 Malignant Glioma (U87MG) cell line, human osteosarcoma cell lines SaOS-2 and SaOS-LM7, were kindly provided by Dr. Karen Pollok from the Indiana University School of Medicine. GBM43 cells, SaOS2, and SaOS-LM7 were cultured in DMEM medium (without sodium pyruvate) supplemented with 10 % FBS. Prostate cancer (PC)3 cells, Triple-negative breast cancer cell line MDB-MA-231, melanoma cell line SK-MEL-2, acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1, lung cancer cell line A549, NCI-H1299 and NCI-H460 cells were gifted from other labs from Purdue University. Among these cells, U87MG cells, PC3, and A549 were cultured in DMEM medium with Sodium Pyruvate supplemented with 10 % FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. NCI-H1299, and NCI-H460 were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10 % FBS. THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10 % FBS, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All of these cell lines were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5 % CO2 environment.

ExpiCHO-S cells were purchased from Thermal Fisher Scientific and cultured in ExpiCHO expression medium without serum. As indicated in the culture manual, ExpiCHO-S cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 8 % CO2 environment with the shaking speed at 125 rpm.

2.3. Gene constructs and synthesis

The sequence of the scFv targeting the human HLA-A2/β2M/RMF complex was derived from the human TCR-mimic antibody published previously [10]. VL and VH sequences were assembled with a (G4S)3 flexible linker. A signal peptide was added at the N terminus for the purpose of secretion of expressed protein in mammalian cells and a 6 × His tag at the C terminus for purification and detection. The target sequence (Fig. S1) was inserted into the pcDNA3.1+ expression vector and synthesized by GenScript (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China).

2.4. Peptide-pulsed T2 cells

To optimize the assembly of HLA-A2/β2M/peptide complex, T2 cells were seeded at a cell density of 1 × 106/ml in a 96-well plate with 100 μl/well serum-free IMDM basal medium. Recombinant human β2M was added into each well at a concentration of 3, 10, or 20 μg/ml. Based on the β2M concentration, synthetic peptides (RMF or ILS) were added into the wells at concentrations that were either 2.5-fold, 5-fold, or 10-folds those of β2M. Specifically, for the wells containing 3 μg/ml of β2M, 7.5, 15, or 30 μg/ml of peptide were added. T2 cells were then incubated with β2M and corresponding peptides at 37 °C overnight to allow for the complex to form. To confirm the presence of HLA-A2/β2M/peptide complex, the expression of HLA-A2 on the surface of T2 cells were measured by flow cytometry. T2 cells were harvested and washed twice with 1 × PBS buffer. FITC-conjugated anti-human HLA-A2 antibody (clone BB7.2) was used to stain the cells at 4 °C for 30 min protecting from light. After 3 × wash cycles, cells were resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS containing 2 % of FBS) for flow cytometry detection using the BD Fortessa Cell Analyzer (Becton Dickinson). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

The extent of formation of the HLA-A2/β2M/peptide complex was measured via the fluorescence index (FI), calculated by the formula below:

MFI indicates mean fluorescence intensity. Higher FI indicates increased surface expression of HLA-A2 on T2 cells due to the complex formation.

2.5. Protein expression

ExpiCHO-S cells were cultured according to the manufacturer’s user guide. Briefly, ExpiCHO-S cell were cultured in the ExpiCHO expression medium at the initial cell density of (0.2~0.4) × 106/ml and passaged when they reached a density of approximately (4~6) × 106/ml. After 2~3 passages, ExpiCHO-S cells were resuspended in fresh ExpiCHO expression medium at a cell density of 3 × 106 /ml. The plasmid encoding anti-HLA-A2/β2 M/RMF complex scFv was added into a tube containing 500 μl of Opti-MEM medium at a ratio of 0.8 μg/ml (DNA:cell volume), and transfection reagent FectoPRO was added to the other 500 μl of Opti-MEM medium. The ratio of DNA:FectoPRO was optimized and set up at 1:2 (μg:μl). After incubation at RT for 5 min, DNA and FectoPRO were mixed and incubated at RT for another 10 min. The mixture was added into the ExpiCHO-S cells dropwise. ExpiCHO-S cells were incubated at 37 °C for 3–5 days to allow for protein expression. Cell viability was measured every day. Supernatant was harvested by centrifugation at 300 g for 10 min to remove the cell pellet, for as long as the cell viability remained above 50 %. The harvested supernatant was filtered using a 0.22 μm membrane and purified directly or stored at the −80 °C until purification.

2.6. Protein purification

The anti-HLA-A2/β2 M/RMF complex scFv protein was purified using Ni-NTA spin columns owing to the presence of a 6 × His tag at the C-terminus of the protein. The collected supernatant was mixed with the same volume of equilibration buffer (1 × PBS with 10 mM imidazole; pH 7.4) and then added into the equilibrated Ni-NTA spin column for binding to the resin with shaking at 4 °C overnight. Following this, the column was spun down at 700 g for 2 min to remove the unbound flowthrough and washed with two resin-bed volumes of Wash Buffer several times (1 × PBS with 25 or 50 mM imidazole; pH 7.4). The target protein was eluted from the resin using one resin-bed volume of elution buffer (1 × PBS with 250 mM imidazole; pH 7.4) and quantified using Coomassie Plus (Bradford) Assay Reagent. The eluted protein was dialyzed in 1 L 1 × PBS solution at 4 °C overnight and further concentrated using a PES protein concentrator with a 10 K MWCO at 4 °C. The final concentration of the purified protein was measured using the Qubit protein assay kit. The purified protein was further verified by SDS-PAGE for molecular weight and western blot for the presence of the His tag.

2.7. Flow cytometry-based binding assay

T2 cells were pulsed as described before with peptides and β2M and then washed twice with 1 × PBS. Enriched or purified anti-WT1 scFv protein were added to the cells at the required final concentration in 100 μl PBS and cells were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. After the binding, cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS to remove the unbound protein and stained with the APC-conjugated anti-His Tag antibody at 4 °C for 30 min in the dark. After washing, cells were resuspended in FACS buffer containing SYTOX-blue dead cell stain for the live/dead staining. The bound APC-anti-His antibody was measured by flow cytometry on a BD Fortessa Cell Analyzer (Fig. S2). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

2.8. Intracellular staining of WT1

Intracellular staining was carried out to measure the expression of WT1 on tumor cell lines. Specifically, human patient-derived GBM43 cells were collected into micro-tubes and fixed with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) for 20 min at 4 °C. Then, the cells were stained with Alexa Fluro 680-conjugated anti-human WT1 antibody (F-6) in Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing twice with Perm/Wash buffer, the cells were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD Fortessa Cell Analyzer. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software.

3. Results

3.1. Assembly of WT1-derived peptides with HLA complex on T2 cells

Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1) protein, encoded by the WT1 gene, is a widely studied tumor antigen that has been shown to be overexpressed in leukemias and a wide range of solid tumors, including GBM. As an intracellular protein, WT1 can be processed and degraded by the proteasome or endo/lysosomes intracellularly, with the resulting 9-mer fragments possessing binding motifs to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules. The 9-mer fragments can bind to MHC class I to form epitope/HLA complexes on the surface of tumor cells. The HLA in turn presents the WT1 epitopes to the immune system and induces cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses through peptide-MHC (pMHC)-T cell receptor (TCR) interaction. However, the expression of the WT1 peptide complex on various cancer types is unclear. In order to define the extent of expression of the targetable extracellular complex, we sought to develop an antibody-based method to characterize the targetability of WT1 in various cancers. Firstly, to identify the potential target epitopes derived from the WT1 protein, the online algorithm tool NetMHC4.4 was used to analyze and predict the binding affinity of these epitopes to HLA-A2*02:01, which is the predominant HLA-A allele in North America and Europe. According to the prediction by the NetMHC4.4 algorithm, the whole WT1 protein sequence can be digested into 441 short peptides with the length of 9 amino acid (aa) residues within 4 high and 3 weaker binders to HLA-A*02:01 as listed in Table 1. Among these WT1 epitopes, WT110–18 (ALLPAVPSL) and WT1126–134 (RMFPNAPYL) showed high potential to bind to HLA-A2 with a strong binding affinity (<10 nM). Among these, most TCR-mimic antibodies targeting WT1-derived epitopes have focused on WT1126–134 (RMFPNAPYL), which remains the most widely validated epitope. Hence, the RMFPNAPYL (RMF) peptide was selected for further evaluation, while the ILSLELMKL (ILS) peptide, which possesses a weaker binding affinity to HLA-A*02:01, was selected as the control.

Table 1.

WT1-derived peptides binding to HLA-A2 predicted by the NetMHC4.0.

| Item | Name | Sequence | Length | 1-log50k(aff) | Affinity(nM) | Bind level | %rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10–18 | ALLPAVPSL | 9 | 0.834 | 6.01 | strong | 0.05 |

| 2 | 37–43 | VLDFAPPGA | 9 | 0.525 | 170.8 | weaker | 1.5 |

| 3 | 126–134 | RMFPNAPYL | 9 | 0.818 | 7.14 | strong | 0.06 |

| 4 | 187–195 | SLGEQQYSV | 9 | 0.715 | 21.76 | strong | 0.3 |

| 5 | 191–199 | QQYSVPPPV | 9 | 0.686 | 29.84 | strong | 0.4 |

| 6 | 225–233 | NLYQMTSQL | 9 | 0.495 | 236.39 | weaker | 1.8 |

| 7 | 280–288 | ILCGAQYRI | 9 | 0.551 | 128.47 | weaker | 1.2 |

| 8 | Control | ILSLELMKL | 9 | 0.531 | 160.52 | weaker | 1.4 |

To evaluate the complexation of WT1-derived epitopes to HLA-A*02:01 and human β2 microglobulin (β2M) to form the MHC complex for TCR recognition, T2, a lymphoma-derived cell line, was utilized as the antigen presentation model due to the deficiency in a transporter associated with antigen processing protein (TAP), which enables it to present exogenous peptides in the complex with HLA-A2 on the cell surface. This makes in vitro peptide-pulsed T2 cells a valuable tool for studying the process of antigen presentation.

In the presence of the appropriate peptide and human β2M, HLA-A2 expressed on the surface of T2 cells was able to bind to both, thus successfully forming the antigen presentation complex (Fig. 1A). Once the complex had formed, HLA-A2 was temporarily fixed on the surface of T2 cells, resulting in the increased surface expression level of HLA-A2. Therefore, we could evaluate the formation of the antigen presentation complex by measuring the surface expression of HLA-A2. In order to validate the binding of selected WT1-derived peptides to HLA-A2, we incubated T2 cells with peptide RMF or ILS in the presence of β2M overnight. After complex assembly, the surface expression levels of HLA-A2 were detected by staining the cells with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-A2 antibody. Without pulsed peptide, T2 cells showed low expression of HLA-A2 (MFI = 16,788), while after incubation with peptides, the HLA-A2 expression on the surface of T2 was significantly increased (Fig. 1B), indicating that both RMF (MFI = 74,154) and ILS (MFI = 53,912) peptides were able to bind to the HLA-A2/β2M complex. We also noticed that T2 cells, when incubated with RMF, showed a higher expression of HLA-A2 compared to when incubated with ILS, consistent with predicted binding results which suggested that RMF is a stronger binder than ILS to the HLA-A2/β2M complex.

Fig. 1.

Optimization of peptide-HLA-A2/β2M complex assembly on T2 cells. A) Diagram of the peptide-HLA-A2/β2M complex. B) The HLA-A2 expression level on T2 cells after pulsing with WT1-derived peptides. 1 × 105 T2 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate in the presence of β2M (20 μg/ml) and WT1-derived peptides RMF or ILS (50 μg/ml) in IMDM medium (without serum). After peptide pulsing, T2 cells were washed and stained with a FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-A2 antibody. The HLA-A2 expression level on the T2 cell surface was measured by flow cytometry. C) The HLA-A2 expression level on T2 cells under various pulse conditions. The same pulsing process was performed as described above, but with various concentration of β2M (3,10, and 20 μg/ml) and WT1-derived peptides RMF (2.5-fold, 5-fold, and 10-fold of β2M). After peptide pulsing, flow cytometry was used to measure the HLA-A2 expression level on T2 cells.

To further optimize the incubation conditions of peptide-pulsed T2 cells, we tested complex assembly at various concentrations of β2M and RMF peptide. We used concentrations of β2M of 3, 10, and 20 μg/ml for the same cell density (1 × 106/ml) of T2 cells in culture medium without serum. RMF peptide was added at a final concentration to correspond to 2.5 ×, 5 ×, and 10 × that of β2M. HLA-A2 expression on T2 cells was measured by flow cytometry after 24 h incubation. With an increase in peptide and β2M concentration, there was more RMF-HLA-A2/β2M complex assembled on T2 cells (Fig. 1C). To quantify the formation of RMF-HLA-A2/β2M complex, FI was calculated by normalizing the fold change of MFI of HLA-A2 to the unpulsed T2 cells (Table 2). A high amount of β2M (20 μg/ml) with a 10 × higher RMF peptide concentration during complexation achieved the highest antigen presentation on T2 cells, as measured by a 2.84-fold change of HLA-A2 expression on the T2 cell surface. We also measured complex formation under the same conditions of β2M and peptides but in the presence of serum during incubation. The presence of serum significantly impeded the binding of peptides to HLA-A2 (data not shown). Therefore, optimal pulse conditions (without serum, β2M at a concentration of 20 μg/ml and peptide at 200 μg/ml) for peptide to T2 cells were selected for further studies. The fluorescence intensity changes of HLA-A2 level on T2 cells at various peptide pulse conditions. The formula used to calculate FI was:.

Table 2.

FI change of HLA-A2 on T2 cells at various optimization concentrations.

| Concentration of β2M (μg/ml) | Concentration of peptides (ratio of β2M μg/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 × | 5 × | 10 × | |

| 3 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.416 |

| 10 | 0.25 | 0.64 | 1.34 |

| 20 | 0.98 | 1.68 | 2.84 |

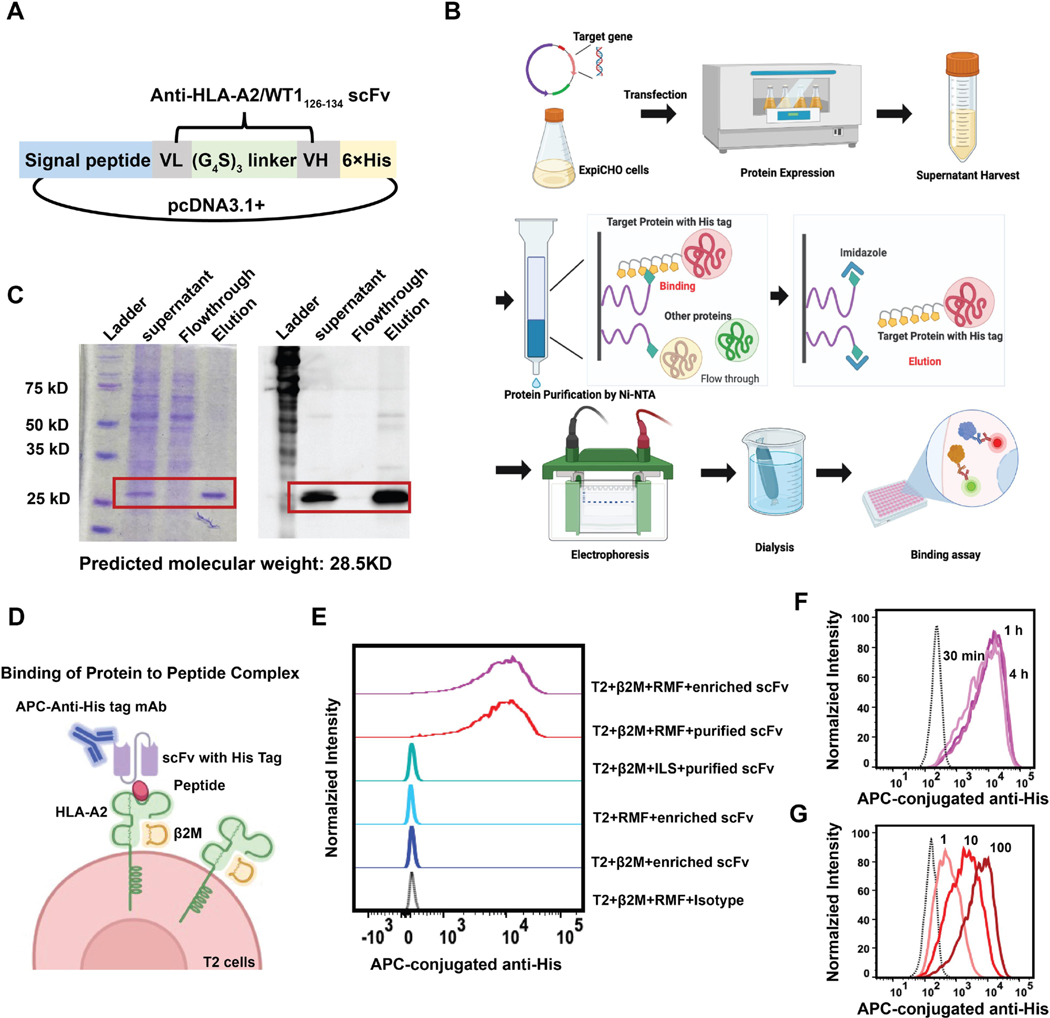

3.2. Expression and purification of scFv targeting the RMF-HLA-A2/β2M complex

Using the sequence of a known T cell receptor-mimic antibody specific for the WT1126–134 /HLA-A2/β2M complex [10], the scFv was generated by linking the VH and VL domain via a flexible (G4S)3 linker. A signal peptide was inserted at the N-terminus to promote secretion of the protein and a 6 × His tag was added to the end of the scFv for detection and purification (Fig. 2A). The scFv sequence targeting the WT1126–134 /HLA-A2/β2M complex was cloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1+ and transiently transfected into ExpiCHO cells using FectoPro reagents to express the scFv. The expressed scFv, secreted by the ExpiCHO cells into the culture medium, was then harvested from the supernatant and purified by affinity chromatography. SDS-PAGE gel and western blot were utilized to measure the expression of target scFv protein (Fig. 2). Both assays confirmed that the expressed scFv had a molecular weight of 28.5 kDa including a His-tag, suggesting the successful expression and purification of the target scFv protein in the mammalian system.

Fig. 2.

Expression, purification, and validation of the scFv protein targeting the RMF-HLA-A2/β2M complex. A) The design of the scFv expression vector. VL and VH sequences were linked together by a flexible GS linker to form the scFv. The signal peptide was inserted into the N-terminus and the 6 × His tag was added at the C-terminus for purification and characterization. The expression sequence was inserted into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1+. B) Scheme of the expression and purification process. The expression plasmid was transiently transfected into ExpiCHO cells and cultured for 5 days. The secreted target protein was purified via IMAC chromatography. Expression of the purified protein was characterized by gel electrophoresis and western blot. A functional assay was also performed using the cell-based binding assay after dialysis and concentration. C) Characterization of the purified protein by SDS-PAGE and western blot. Left: SDS-PAGE gel. Right: western blot. In both images, lane 1: protein standard; lane 2: harvested supernatant from ExpiCHO cells; lane 3: flowthrough after protein binding to the nickel column; lane 4, eluted target protein from the nickel column. D) Schema of scFv binding to the extracellular peptide complex measured using flow cytometry. E–G) Validation of the binding of the target protein (scFv) to peptide-pulsed T2 cells. T2 cells were pulsed with WT1-derived peptide and then incubated with the target protein to allow binding to occur. Cells were then washed and stained using an APC-conjugated anti-His-tag antibody. The abundance of His-tag on the cell surface was measured by flow cytometry. F) RMF-pulsed T2 cells were incubated with target protein for varying lengths of time, and the binding was measured by flow cytometry. G) RMF-pulsed T2 cells were incubated with target protein at various concentrations (1 μl, 10 μl, and 100 μl) and the binding was measured by flow cytometry.

To evaluate the binding activity of the purified protein to its specific target, RMF-HLA-A2/β2M complex, peptide-pulsed T2 cells were used as the antigen presentation model. To do this, T2 cells were incubated in the presence of human β2M and peptides for 24 h to form the HLA-A2/peptide complex on the T2 cell surface. After washing the unbound peptides away, pulsed T2 cells were incubated with the purified scFv protein with the His-tag and stained with APC-conjugated anti-His tag antibody (Fig. 2D). By measuring the fluorescence intensity of the His-tag on T2 cells using flow cytometry, we observed that both enriched and purified scFv proteins were able to successfully bind to the RMF-pulsed T2 cells. T2 cells incubated with either RMF peptide or human β2M showed no binding to the scFv, due to the incomplete HLA-A2/peptide complex, indicating the requirement for correct and complete HLA-A2/β2M complex assembly. Further, the scFv showed no binding to T2 cells pulsed with ILS peptide (a weaker binder to the HLA-A2/β2M complex), which indicates selectivity of binding to the higher-affinity RMF/HLA-A2 complex. Additionally, we measured the binding of the scFv protein to its ligand at various incubation times (30 min, 1 h, and 4 h). The purified protein was able to bind to RMF-pulsed T2 cells in a dose-dependent manner and the binding saturation time was as short as 30 min, which was selected as the optimal incubation time for further binding studies (Fig. 2F and G). Our results have shown that the expressed scFv protein was able to selectively recognize and bind to the extracellularly-presented antigen by the RMF-HLA-A2/β2M complex on T2 cells.

3.3. Evaluation of the presence of WT1 derived antigen on tumor cell lines

Following successful expression and purification of the scFv protein, and demonstration of its ability to selectively recognize the RMF-HLA-A2/β2M complex, we sought to evaluate whether WT1-derived RMF could be a targetable extracellular tumor antigen on various tumor cell lines, especially GBM, for which such data are scarce. The prerequisite for such recognition is the expression of both HLA-A2 and WT1 on the target cells. We first measured the expression of HLA-A2 and WT1 on GBM cell line U87MG and patient-derived GBM cell GBM43 cell by flow cytometry. K562 cells were used as the HLA-A2 negative, WT1 positive control. These data showed that HLA-A2 was highly expressed on the surface of both GBM43 and U87MG cells (Fig. 3A). WT1, as an intracellular protein, was also detected in GBM43 and U87MG cells by intracellular staining.

Fig. 3.

Specific binding of WT1 peptide complex-targeting scFv to various tumor cell lines. A) Expression of HLA-A and WT1 proteins on selected tumor cell lines. The expression of HLA-A2 on K562, U87MG, patient-derived GBM43, and MDA-MB-231 cells was measured by surface staining of the anti-HLA-A2 antibody using flow cytometry. The expression of WT1 protein was measured by intracellular staining of the anti-WT1 antibody. B) The binding of the purified WT1 peptide complex-targeting scFv protein to selected tumor cell lines. Multiple tumor cells were incubated with the target protein on ice for 30 min and then stained by APC-conjugated anti-his tag antibody. The level of binding was measured by flow cytometry. Dashed lines are the unstained controls, the solid grey lines represent the isotype control, and the solid colored lines are the measured samples.

Based on these data, the scFv protein was used to recognize GBM43 cells and U87MG cells, which are both HLA-A2 and WT1 positive. To do so, GBM cells were incubated with the scFv protein at 4 °C for 30 min, and then APC-conjugated anti-His tag antibody was used to stain the cells. However, the scFv showed no specific binding to either U87MG or GBM43 cells. Although the expression of HLA-A2 and the WT1 had been validated in both GBM43 and U87MG cells, the lack of scFv binding might indicate that WT1 cannot be processed to RMF peptide and is thus unable to be correctly presented on the cell surface in the form of HLA-A2/RMF complex. Furthermore, due to the relatively low expression of HLA-A2 and WT1, the density of the HLA-A2/WT1126–134 complex might be too low to be recognized by our scFv protein. To improve the assembly of RMF peptide complex on GBM43 cells, we attempted to pulse GBM43 cells in the presence of exogenous RMF peptide for 24 h. However, the peptide pulsed-GBM43 cells were still not able to be recognized by the scFv protein.

In addition, to verify whether other cell lines beyond GBM are able to present the complex for extracellular recognition, we also measured the binding of the scFv protein to other solid tumor cell lines, including MDA-MB-231, A549, THP-1, SAOS2, SAOS-LM7, PC-3, SK-MEL-2, H1299, and H460 (Fig. 3B). Among these cell lines, PC-3, SK-MEL-2, H1299, and H460 were detected as HLA-A2 negative and correspondingly showed no binding to the scFv protein. Similarly to GBM cell lines, although a number of other cell lines (MDB-MA-231, A549, THP-1, SAOS2, SAOS2-LM7) were HLA-A2 positive, they showed no evidence of binding after incubation with the scFv protein. All of these results indicate that WT1-derived antigen RMF may be not suitable as a targetable extracellular tumor-specific antigen on these cell lines.

4. Discussion

Despite recent clinical successes of various cell-based immunotherapies against hematopoietic tumors, one of the challenges with solid tumors has been the identification of specific tumor-associated antigens. Currently, the wider application of these therapeutic approaches is constrained by targeting cell surface antigens, which are abundantly expressed on tumor cells but also on normal tissues, resulting in lower anti-tumor activity due to off-target effects and targeting-related toxicities. The development of TCR-mimic antibodies has enabled the targeting of intracellular proteins as highly specific tumor-associated antigens in various cancers, including solid tumors. In the present study, we expressed and developed a TCR-mimic antibody fragment (scFv) specifically targeting an antigen derived from the WT1 oncoprotein. After the validation of its binding capacity to the peptide presented by the HLA-A2/β2M complex, we evaluated the potential of recognition of the WT1-derived peptide complex as a targetable extracellular tumor-specific antigen on multiple tumor cell lines, which may provide some hints to future studies designing novel therapeutics against solid tumors via targeting the WT1 oncoprotein.

The WT1 oncoprotein, a zinc finger transcription factor, has been ranked at the top of a the list of “ideal” cancer antigens in a study by the National Cancer Institute [11]. Despite its discovery as a tumor suppressor, WT1 has been characterized as a tumor oncogene overexpressed in a variety of cancers, including leukemias, lymphomas, and various solid tumors, including GBM [12,13]. Numerous efforts have been made to design and develop therapies against the WT1 oncoprotein. The most common have been WT1-derived peptide vaccines, many of which have been evaluated clinically against liquid and solid tumors. These efforts have demonstrated clinical safety in patients with complex cancers including recurrent malignant glioma [14,15]. The development of TCR-mimic antibodies has made it possible to target intracellular proteins, thus expanding the availability of antigen pools to those beyond extracellular targets. Multiple immunotherapeutic formats targeting WT1-derived peptides beyond TCR-mimic monoclonal antibodies have also been developed, which include CAR-T cell therapy with the scFv targeting WT1 peptides, ADC-TCR conjugates, and TCR-bispecific T cell engagers (BITEs) [10,16–20]. However, the majority of the attempts have been for hematological malignancies such as AML, not solid tumors. More work is required to evaluate whether the WT1 peptide could be a suitable tumor-associated antigen for solid tumors and thereby stimulate the development of novel therapeutics targeting its overexpression in cancer.

To address this, in our study, the fragment of a known TCR-mimic antibody, specifically recognizing the WT1-derived peptide RMF, was expressed, purified, and its binding to the target complex validated. We attempted to recognize tumor cells via the purified TCR-like scFv, which would indicate successful extracellular recognition of the HLA-restricted WT1 peptide. Although HLA-A2 and WT1 protein were successfully detected on GBM cells including the U87MG cell line and patient-derived GBM43 cells by surface and intracellular flow cytometry, our TCR-scFv could not bind to these cells. This suggests the possibility of low abundance of presentation of the processed peptide in these tumor types. Another possible reason for these results is the low binding affinity of scFv to its target despite the reported strong binding at a concentration as low as 0.01 μg/ml. Another potential explanation is the incorrect assembly of the antigen by the HLA-A2. The antigen presentation process involves protein lysis by the lysosome, assembly of the peptide with HLA-A2 in the ER, and then the transportation of peptide-HLA-A2 complex to the cell surface. However, any mistakes involved in the antigen presentation process will lead to loss of the antigen. For instance, T2 cells, which we used as the positive model in the validation assay, could only be pulsed with the epitopes extracellularly due to the deficiency of the TAP. We also tried to pulse GBM cells in a similar way to improve the antigen density on the surface of the cells but failed to see any changes. On the other hand, malignant cells are reported to downregulate expression of MHC-class I to escape from immune surveillance, which may also contribute to the low density of antigen on the solid tumor cells tested.

Our study demonstrated that the WT1-derived peptide RMF may not be an optimal tumor recognition marker on many solid tumor cell lines including GBM43 and U87MG, as it was difficult to recognize tumor cells by the peptide/HLA-A2 complex on the surface. However, one limitation of our results was that the binding was only tested through a direct binding assay utilizing a validated specific antibody fragment based on in-silico prediction of binding affinity. Other approaches to directly detect and quantify neoantigens have been reported and could provide an additional dimension to these binding results. For example, mass spectrometry has been used together with immunoprecipitation with relevant anti-HLA antibodies to analyze whether predicted neoantigen peptides are actually expressed, processed correctly, and presented successfully by the HLA complex on the cell surface. However, this method is not well applicable for low abundance neoantigens. Qing and colleagues developed a method via optimized immunoprecipitation coupled with two-dimensional chromatography and mass spectrometry to detect and quantify the copy numbers of neoantigen on tumor cells with improved sensitivity [21]. In practice, combining the direct binding assay using a specific antibody with such an additional quantification method may provide more depth of information about the extent of the antigen presentation process and offer more detailed information about the abundance of neoantigen peptides presented on the cell surface. Nonetheless, our study represents the first example of characterization of the extracellular targetability of WT1 peptide complexes on a number of commonly used cancer cell lines representing various solid tumors, using approaches that can be implemented with ease.

In conclusion, our study established an optimized method to express and purify specific antibody fragments targeting extracellular WT1-processes peptide, validate their binding affinity using a peptide-pulsed T2 cell antigen presentation model and, for the first time, establish the recognition of WT1 peptide on a variety of common cell lines representing various solid tumor models. As a tool, it provides a robust approach to generate WT1 peptide complex-targeting antibody fragments for use in targeted cell therapies, including CARs or BiTEs. As such, the protocol paves the way for the development of more TCR-mimic antibodies and novel therapeutics targeting intracellular proteins as extracellular tumor-associated antigens for cancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2024.106881.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1 R21CA256413-01 from the National Cancer Institute, the V Foundation for Cancer Research (Grant #D2019-039), the Walther Cancer Foundation (Embedding Tier I/II Grant #0186.01, as well as a Purdue Research Fellowship, a Lilly Endowment Gift Graduate Research Award and the SIRG Graduate Research Assistantships award (P30CA023168) to Xue Yao. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the support of the Flow Cytometry Shared Resource, with support from the Purdue Center for Cancer Research, NIH grant P30 CA023168, the IU Simon Cancer Center NIH grant P30 CA082709, and the Walther Cancer Foundation. The authors also gratefully acknowledge support from Xyphos Biosciences (an Astellas company).

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xue Yao: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Sandro Matosevic: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Sandro Matosevic reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data and materials availability

Source data for all figures are provided with this paper and are available online. All other data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD, Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy, Science 348 (6230) (2015) 69–74 (80-.). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Apavaloaei A, Hardy MP, Thibault P, Perreault C, The origin and immune recognition of tumor-specific antigens, Cancers (Basel) 12 (9) (2020) 2607. Pagevol. 12p. 2607, Sep. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Minati R, Perreault C, Thibault P, A roadmap toward the definition of actionable tumor-specific antigens, Front. Immunol 11 (2020) 583287. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sugiyama H, WT1 (Wilms’ Tumor Gene 1): biology and cancer immunotherapy, Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol 40 (5) (2010) 377–387. May. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chapuis AG, et al. , Transferred WT1-reactive CD8+ T cells can mediate antileukemic activity and persist in post-transplant patients, Sci. Transl. Med 5 (174) (2013). Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Oka Y, et al. , Human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses specific for peptides of the wild-type Wilms’ tumor gene (WT1) product, Immunogenetics 51 (2) (2000) 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Oka Y, et al. , Induction of WT1 (Wilms’ tumor gene)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by WT1 peptide vaccine and the resultant cancer regression, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 101 (38) (2004) 13885–13890. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schmitt TM, et al. , Enhanced-affinity murine T-cell receptors for tumor/self-antigens can be safe in gene therapy despite surpassing the threshold for thymic selection, Blood 122 (3) (2013) 348–356. Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dao T, et al. , An immunogenic WT1-derived peptide that induces T cell response in the context of HLA-A*02:01 and HLA-A*24:02 molecules, Oncoimmunology 6 (2) (2017) e1252895. Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dao T, et al. , Targeting the intracellular WT1 oncogene product with a therapeutic human antibody, Sci. Transl. Med 5 (176) (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cheever MA, et al. , The prioritization of cancer antigens: a National Cancer Institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research, Clin. Cancer Res 15 (17) (2009) 5323–5337. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Menssen HD, et al. , Wilms’ tumor gene (WT1) expression in lung cancer, colon cancer and glioblastoma cell lines compared to freshly isolated tumor specimens, J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 126 (4) (2000) 226–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Oji Y, et al. , Overexpression of the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in primary astrocytic tumors, Cancer Sci. 95 (10) (2004) 822–827. Oct. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Oji Y, et al. , Association of WT1 IgG antibody against WT1 peptide with prolonged survival in glioblastoma multiforme patients vaccinated with WT1 peptide, Int. J. Cancer 139 (6) (2016) 1391–1401. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Izumoto S, et al. , Phase II clinical trial of Wilms tumor 1 peptide vaccination for patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme, J. Neurosurg 108 (5) (2008) 963–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rafiq S, et al. , Optimized T-cell receptor-mimic chimeric antigen receptor T cells directed toward the intracellular Wilms Tumor 1 antigen, Leukemia 31 (8) (2017) 1788–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tassev DV, Cheng M, Cheung N-K, Retargeting NK92 cells using an HLA-A2-restricted, EBNA3C-specific chimeric antigen receptor, Cancer Gene Ther. 19 (2012) 84–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shen Y, et al. , The antitumor activity of TCR-mimic antibody-drug conjugates (TCRm-ADCs) targeting the intracellular wilms tumor 1 (WT1) oncoprotein, Int. J. Mol. Sci 20 (16) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kurosawa N, Wakata Y, Ida K, Midorikawa A, Isobe M, High throughput development of TCR-mimic antibody that targets survivin-2B80–88/HLA-A*A24 and its application in a bispecific T-cell engager, Sci. Rep 9 (1) (2019) 1–11. 91Jul. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dao T, et al. , Supplementory-Therapeutic bispecific T-cell engager antibody targeting the intracellular oncoprotein WT1, Nat. Biotechnol 33 (10) (2015) 1079–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang Q, et al. , Direct detection and quantification of neoantigens, Cancer Immunol. Res 7 (11) (2019) 1748–1754. Nov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data for all figures are provided with this paper and are available online. All other data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.