Abstract

Background

Health activation is an individual’s knowledge, skills, and confidence in managing personal health and healthcare. The Consumer Health Activation Index (CHAI) is a freely available, 10-item measure originally developed in the United States. This study aimed to validate CHAI among community-dwelling adults in Singapore, examining its content validity, construct validity and test-retest reliability.

Methods

The study was conducted in two phases. In Phase 1, cognitive interviews with nine population health experts and eleven lay participants assessed face and content validity. In Phase 2, a cross-sectional survey of 572 adults, recruited via quota sampling aligned with national census distributions, was conducted. Participants completed the CHAI, EQ-5D-5L, EQ-VAS, and the Internal subscale of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with principal axis factoring and varimax rotation, along with Cronbach’s alpha, assessed structural validity and internal consistency respectively. Test-retest reliability was evaluated in a subsample of 32 participants, of whom 21 reported stable health status at follow-up.

Results

Content validity was acceptable, with a Scale-Level Content Validity Index (S-CVI) of 0.86, although minor wording issues were noted for CHAI items 5, 6, and 10. EFA supported a unidimensional structure, and the CHAI demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.85). CHAI scores showed moderate positive correlations with the MHLC internal subscale (Pearson’s r = 0.449) and weak to moderate positive correlations with EQ-5D-5 L and EQ-VAS, (r = 0.171–0.344). Known-group validity was supported by significantly higher CHAI scores among individuals with chronic diseases (p = 0.017). Test-retest reliability was good (ICC = 0.802, 95% CI = 0.544–0.911).

Conclusion

In summary, the CHAI is a reliable and valid measure of health activation for community-dwelling adults in Singapore. While overall psychometric performance was robust, minor refinements in phrasing may improve language clarity and cultural applicability. Longitudinal research is recommended to further establish CHAI’s utility in both clinical and community local settings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12963-025-00402-z.

Keywords: Health activation, Consumer health activation index, CHAI, Instrument validation, Singapore, Asia, Construct validity

Introduction

Health activation, also referred to as patient activation, can be broadly defined as “an individual’s knowledge, skills and confidence in managing their health and health care”, and it has been shown to have a stronger association with health outcomes than traditional socio-demographic variables [1, 2]. It is closely related to—but distinct from—health literacy or health engagement [1, 2], as it focuses specifically on the internal capacity and behavioral inclination to manage one’s own health and healthcare. Unlike passive health behaviors, health activation implies a proactive stance, where individuals not only understand health information but also apply it meaningfully in everyday decisions. In general, higher activation is thought to be associated with increased participation in preventive health strategies, including screenings, immunizations and health-promoting behaviors such as physical activity and dietary improvements [3–6]. Understanding differences in activation levels and optimizing them through interventions could thus improve long-term health outcomes.

Patient activation has gained traction as a cornerstone of chronic illness management, reflecting a shift towards patient-centered care models that emphasize self-management. The Chronic Care Model (CCM) underscores the importance of patient activation in enhancing self-care and improving health outcomes [7]. The most widely used measure of patient activation is the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), developed by Hibbard et al. in 2004 [8]. It conceptualizes activation as a progressive development of knowledge, confidence, and self-management skills. PAM is a unidimensional scale that categorizes individuals into four levels (based on scoring cut-offs), from disengagement to proactive health management [8]. Although extensively validated across different populations, its proprietary nature, cost and complexity limit its applicability, particularly in populations with varying health literacy levels [9]. Moreover, a previous validation study of the PAM among a sample of 270 Singaporean adults with cardiac conditions found mixed evidence supporting its use [10].

An alternative to the PAM is the Consumer Health Activation Index (CHAI), developed by Wolf et al. [11]. Originating from the United States (US) and first published in 2018, the CHAI was developed by Wolf et al. [11] using an iterative, theory-informed process involving literature review, expert consultation, cognitive interviews and psychometric testing among a diverse sample of adults. Five conceptual domains guided item generation: knowledge, beliefs, self-efficacy, locus of control and actions. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) supported a unidimensional 10-item structure, with a sixth-grade reading level to enhance usability across populations [11]. The CHAI demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.81) and moderate test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.53). Its scores were moderately correlated with related constructs such as internal locus of control and conscientiousness, and were predictive of physical functioning and mental health outcomes.

Importantly, the CHAI is freely available, in contrast to the proprietary PAM, making it a pragmatic option for both clinical and research applications. Moreover, the CHAI was designed for adults with varying levels of health literacy across different healthcare settings and has been applied in various health contexts, including treatment adherence, pandemic preparedness, vaccine trust and telehealth satisfaction [12–16]. A previous validation study was done in South Australia [17], and given its emphasis on key health activation domains (beliefs, knowledge, locus of control, self-efficacy and actions), CHAI presents an opportunity for use as a comprehensive, yet free-to-use and accessible health activation measure in Singapore.

Singapore is experiencing rapid population ageing, with one in four citizens projected to be aged 65 years and older by 2030 [18]. This demographic shift has led to a higher prevalence of chronic disease, accompanied by increased healthcare utilization. In response, a nationwide population health initiative (termed Healthier SG) was launched in July 2023 to promote upstream care by prioritizing preventive health strategies that integrate social and healthcare services, while emphasizing the role of family physicians in chronic disease management [19]. A key component of this strategy is to encourage individuals to take greater ownership of their health through lifestyle modifications and preventive health measures. In this context, measuring health activation could serve as a valuable tool for quantifying effects, population segmentation and, if measured longitudinally, could provide an indicator for self-management capacity over time.

This study therefore aimed to validate the CHAI among community-dwelling individuals in Singapore to ensure that the tool accurately captures the unique cultural, social, and linguistic nuances of the population. Conducted in two phases, we first assessed its content validity through cognitive interviews, followed by evaluating its structural validity, construct validity (with the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) internal locus subscale [20]), and test-retest.

Methods

Design and setting

This mixed-methods study was conducted at two large public primary care clinics, also known as polyclinics, under National University Polyclinics (NUP) in the western region of Singapore between October 2024 and December 2024. NUP oversees seven polyclinics which serve approximately one-third of the public primary care population in the country. Ethical approval for the study and all related activities was obtained from the Department Ethics Review Committee, National University of Singapore (approval number SSHSPH-269).

This study adhered to the Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) guidelines [21] and was conducted in two phases.

Phase one: content validation of CHAI

Phase one involved 20 in-depth interviews to explore the concepts and content of CHAI, specifically with nine population health experts and 11 lay participants. The population health experts had at least five years of experience in health systems, community health, or health policy or health services research, and were currently employed in an academic, health care, or government position with responsibilities related to health systems or population health at the point of interview. All individuals who were older than 21 years, English-speaking and able to provide informed consent, were eligible to participate in the patient interviews. Participants were recruited using convenience and snowball sampling within the polyclinics. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews lasting between 20 and 60 min were conducted one-to-one, either in person or privately via Zoom, by trained personnel using a topic guide and handwritten field notes.

The interviews commenced with cognitive interviewing, following a four-step cognitive processing model: understanding the question, retrieving relevant information, preparing a response, and refining the answer. Participants first completed the CHAI before sharing their overall impressions of the questionnaire, including its wording, order, format, clarity, applicability and comprehensiveness in assessing health activation. They also identified any missing dimensions and proposed modifications in their own words. Following this, only the experts were asked to rate the relevance of each CHAI item, and the content validity index (CVI) was calculated [22].

Data analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic analysis to identify key themes related to the clarity, applicability and comprehensiveness of CHAI. Two independent researchers coded the transcripts, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Thematic saturation was achieved when no new insights emerged from additional interviews. For cognitive interviewing, participants’ feedback on item wording, ordering, and response format was categorized based on common concerns and suggestions. For content validity, ratings provided by the expert panel were used to calculate the CVI at both the item level (I-CVI) and scale level (S-CVI). An I-CVI of ≥ 0.78 and an S-CVI of ≥ 0.90 were considered acceptable indicators of content validity [22].

Phase two: psychometric validation of CHAI

Phase two involved a cross-sectional survey in which consenting patients were interviewed face-to-face using the paper-and-pencil method before or after their routine consultation. A trained research assistant administered the survey in English. To ensure the generalizability of findings, a non-probability quota-based sampling approach was employed, aligning participant demographics with the Singapore 2024 population estimate, particularly in terms of age, sex, and ethnicity [23]. This approach enhances the applicability of CHAI across diverse population subgroups. Participants were recruited from public primary care clinics and were eligible if they were aged 21 and above, able to provide informed consent, and had no cognitive impairments that could affect questionnaire completion.

All interviews were conducted in two parts. The first part was a baseline survey in which patients completed a paper-based, self-administered questionnaire covering (1) socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, housing, income, education, height, weight, perceived health status and chronic conditions; (2) CHAI; (3) EQ-5D-5L; and (4) the MHLC. The second part was a retest survey via telephone interview, conducted 1–2 weeks after the baseline survey. During the retest, respondents were asked for their consent to participate in a follow-up assessment to evaluate the test-retest reliability of CHAI. To minimize participant burden, the follow-up survey included only CHAI and 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) Item 1. The SF-36 Item 1 was used to assess current health status, with respondents rating their health as “Excellent, Very good, Good, Fair, or Poor”. To identify the stable health status group, we calculated the difference in scores by subtracting the follow-up response from the baseline response. Participants whose ratings remained unchanged between the two time-points were classified as having stable health status. This method ensured that test-retest reliability was evaluated within a subset of individuals whose self-reported health perceptions remained consistent over time.

The target sample size was set at 400 participants, based on recommendations for factor analysis and psychometric validation studies. According to Comrey and Lee (1992), a sample size of 300–500 is considered “good to very good” for EFA [24]. Furthermore, this sample size accounts for potential issues such as weak factor structures, low communalities and the need for additional psychometric evaluations, including confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and reliability testing, ensuring adequate statistical power for construct validation and factor stability across subgroups.

All participants were administered the original English-language version of the CHAI.

Measures

CHAI

The CHAI was developed to assess the participants’ health activation. It is a freely available, English-language, 10-item unidimensional scale. Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (6)”. The total CHAI score ranges from 10 to 60, which is then transformed into a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating greater health activation [25]. Scores can be categorized into three levels: low activation (0–79), moderate activation (80–94), and high activation (95–100). CHAI has demonstrated good validity and reliability in various settings [11, 17, 26].

EQ-5D-5L

The EQ-5D-5L was used to assess participants’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL). It consists of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, each rated on a five-level scale ranging from “no problems” to “extreme problems” [27, 28]. These responses can be converted into a summary utility score ranging from 0 (a state as bad as being dead) to 1 (“full health”), with negative scores representing health states considered worse than death. Additionally, the EQ-5D questionnaire includes a vertical, hash-marked visual analogue scale (EQ VAS) with 1-point intervals, enabling respondents to assess their overall health on the day of the survey. The two anchors of the EQ VAS are 0 (“The worst health you can imagine”) at the bottom and 100 (“The best health you can imagine”) at the top. The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire used in this study was the official EuroQol-approved English version for Singapore. The most recent Singapore EQ-5D-5L value set was applied, with values ranging from − 0.817 to 1.000 [29]. Both the EQ-5D-5L and EQ VAS have demonstrated satisfactory measurement properties for use in primary care settings [30, 31].

EQ-5D-5L and EQ-VAS were included to assess the degree to which health activation correlates with general health status and perceived well-being, respectively. These constructs were selected as comparators based on theoretical and empirical considerations. While not directly measuring activation, HRQoL is expected to be moderately associated with health activation, as individuals who are more activated may report better subjective health due to greater engagement in self-care.

MHLC (IHLC)

The internal sub-scale of the MHLC, also known as Internal Health Locus of Control (IHLC), was used to assess participants’ beliefs regarding the extent to which their health is influenced by internal factors. The IHLC contains six items. Respondents rate each item on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”), with higher scores indicating stronger endorsement of the locus of control dimension [20]. The internal subscale of the MHLC has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in prior studies (α = 0.68–0.84) [32].

The MHLC internal subscale was selected based on both theoretical alignment and precedent in the original validation study by Wolf et al. [11], where it was also used to establish construct validity of the CHAI. Specifically, the internal locus of control construct (representing an individual’s belief that their health is determined by their own actions) is thought to be conceptually consistent with health activation, which involves motivation, confidence, and a sense of responsibility in managing one’s health.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R and Jamovi (Version 2.5; The Jamovi Project, 2024), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. As there were no missing data, all analyses included the full sample. Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants at baseline were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Structural validity

EFA was performed to examine the factorial structure of the CHAI. Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.05) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (KMO > 0.6) were used to assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The optimal number of factors was determined through factor diagnostics, including the eigenvalue criterion (eigenvalue > 1) and parallel analysis. EFA was conducted on the polychoric correlation matrix using varimax rotation to enhance interpretability and simplify factor loadings.

For this study, we adopted an exploratory approach rather than a confirmatory one as the purpose of this analysis was to identify the latent structure and assess dimensionality in the local context, rather than to test a hypothesized model. As such, CFA was not performed.

Construct validity

Construct validity was assessed through convergent and known-groups validity. Convergent validity was examined using Pearson correlation analyses between CHAI and the EQ-5D-5 L and MHLC. Correlation strength was categorized as weak (0.2–0.34), moderate (0.35–0.50), or strong (above 0.5) [33]. We hypothesized a weak to moderate positive correlation between CHAI scores and the EQ-5D-5 L index, EQ-VAS, general health score, and MHLC scores, given that these measures capture related but distinct constructs of health status and self-perceived health control. Known-groups validity was assessed by comparing CHAI scores across participants’ socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. Effect sizes were calculated to determine the discriminative capacity of CHAI, defined as the difference in mean CHAI scores between two subgroups, divided by the pooled standard deviation. Effect sizes were interpreted as small (≥ 0.20), medium (≥ 0.50), and large (≥ 0.80) [33]. When comparing more than two groups (e.g., different educational levels), a one-way ANOVA was used. Partial eta-squared (η²) was calculated to estimate effect size for these analyses, with thresholds of 0.01, 0.06, and 0.14 representing small, medium, and large effects, respectively [33]. We hypothesized that individuals with chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) would have significantly lower CHAI scores compared to those without, as they are expected to exhibit lower engagement in health-related decision-making [34]. A detailed hypotheses table, summarising the expected and observed relationships, is provided in the Appendix (Table S1).

Test-retest reliability

To assess test-retest reliability, a 1–2-week interval was decided based on practicality and established methodological recommendations for test-retest reliability studies, balancing potential recall bias and the need to avoid real changes in health status [35]. Health stability was determined using SF-36 Item 1 (self-rated health) [36]; only participants whose rating remained the same were included in the reliability analysis. While the item is categorical, consistent ratings reflect perceived health stability. This approach ensured that variations in CHAI scores reflected instrument reliability rather than actual health fluctuations. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using a two-way mixed-effects model for a single measurement and absolute agreement assessment. An ICC value of ≥0.75 was considered indicative of good reliability [37].

Results

Phase one

Findings from cognitive interviewing and face validation

A total of 20 participants (nine population health experts and 11 laypersons) took part in the cognitive interviewing and face validation process. Cognitive interviewing was conducted following the four-step cognitive processing model in which participants first completed the CHAI, then provided feedback on its clarity, item wording, ordering, format, applicability and comprehensiveness in assessing health activation.

As summarized in Table 1, most participants found the CHAI items straightforward to read and relevant to individual health behaviors. However, certain items prompted concerns about clarity and scope. Q3 (“I always know how to make myself feel better”) was seen as potentially mixing physical and mental well-being, leading several experts to suggest more precise terminology, such as “improve my well‐being.” In Q4, the phrase “before making decisions about my health” prompted questions about whether the focus was specifically on information‐seeking or on decision‐making skills. A recurring theme for both experts and laypersons was that items should avoid combining multiple ideas in one statement. Q10, in particular, elicited ambiguity from both experts and lay persons around “health changes” (e.g., whether it referred to lifestyle, medication, or other behaviors) and the intended meaning of the question. Other minor revisions—such as specifying “healthcare provider” and clarifying whether items refer to physical, mental, or broader well‐being—were identified to reflect modern, multidisciplinary care teams.

Table 1.

Summary of qualitative feedback and proposed changes to CHAI items

| Item | Issue / Comments from Cognitive Interviews | Illustrative Quotes | Proposed Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 It is very important that I treat my health as my top priority. | No major concerns; seen as straightforward. Experts deemed it relevant for emphasizing health prioritization. | “That’s [a] clear [question], I should put health first.” (Lay participant) | No change. Item was clear and well-received. |

| Q2 I always know what steps to take when I have a health problem. | Generally easy to understand; participants felt it covered basic self-management steps. One expert noted that “steps to take” could be broad but still acceptable. | “I know to see a doctor or take medicine, but sometimes not exactly which steps.” (Expert) | No change. Participants generally felt the wording was clear. |

| Q3 I always know how to make myself feel better. | Unclear whether “feel better” refers to physical or mental well-being. Some experts found it vague and wondered if it was deliberately so. | “I wasn’t sure if it’s physical or emotional. Maybe they should say ‘improve my well-being’?” (Expert) | Revise to “I always know how to improve my well-being.” |

| Q4 I always know where to look for information before making decisions about my health. | Generally easy to understand. One expert noted it potentially combines two concepts (finding information versus making decisions). Most participants understood it as knowing where to get health information. | “I’m clear on where to find details, but not sure about the ‘making decisions’ part.” (Expert) | Possible split or clarify scope, “I always know where to look for reliable health information.” |

| Q5 I can always take care of myself. | Vague and overly broad (item-level agreement was low). Some experts questioned the relevance of the question and were unsure if it referred to daily self-care, mental health, or managing chronic issues. | “It’s too general, I don’t know if it means daily chores or serious health issues… And no one can always take care of themselves.” (Expert) | Remove or refine to specify context, e.g. “I can always handle my own health needs.” |

| Q6 It is very easy for me to understand my doctor’s instructions. | Item-level agreement relatively low; some experts felt this question related more to “literacy” or knowing rather than doing. Some also preferred the broader term “healthcare provider” rather than “doctor”. Clarity concerns if instructions come from nurses, pharmacists, etc. | “The doctor’s instruction is okay, but we have a multidisciplinary healthcare team today, with nurses, pharmacists, etc.” (Expert) | Revise to “It is very easy to understand instructions from my healthcare provider.” |

| Q7 It is very easy for me to make changes to my daily life to improve my health. | Two experts felt “to my daily life” was unnecessary. Others generally found it implied lifestyle changes appropriately. | “We already know it’s about daily habits. The question can be shortened.” (Expert) | Revise to “It is very easy for me to make changes to improve my health.” |

| Q8 It is very easy for me to follow my doctor’s instructions. | Similar to Q6, clarifying that instructions may come from multiple professionals. Overall clarity was acceptable, but “doctor’s instructions” could be replaced with “healthcare provider.” | “Same as Q6—the instructions don’t always come from a doctor.” (Expert) | Revise to “It is very easy for me to follow instructions from my healthcare provider.” |

| Q9 I always attend all of my doctor’s appointments. | Generally clear; perceived as measuring adherence to recommended appointments. Some experts suggested further specifying “health-related appointments.” | “To me, if you’re serious about health, you won’t no show [miss] for your appointments.” (Lay participant) | Revise to “I always attend all of my health-related appointments.” |

| Q10 I always make the health changes I should even if I do not feel well. | Ambiguity around “health changes” (lifestyle versus medication changes or others? ) Some confusion about persisting with changes despite “not feeling well.” |

“What are health changes? Could you give me some examples?” (Lay participant) “Do they mean not seeing benefits right away or feeling sick from the changes advised but still continuing to do so?” (Lay participant) “If I am running a fever, should I still run because it is a healthy activity otherwise? What is the intention of this question?” (Expert) |

Revise for simplicity and to clarify scope, e.g. “I always make the necessary changes I should (e.g., lifestyle, behaviors, medications).” |

Abbreviations: CHAI, Consumer Health Activation Index

While minor linguistic refinements to Items 5, 6 and 10 were initially considered during cognitive interviews to improve clarity, we ultimately retained the original item wording. This decision was made to preserve fidelity to the validated version of the CHAI and to maintain conceptual and semantic equivalence with the original scale. We attempted to contact the original authors for consultation but did not receive a response.

Content validation

As shown in Table 2, the Scale-Level Content Validity Index/Average (S-CVI/Ave) was 0.86, slightly below the recommended threshold of 0.90. The S-CVI/Universal Agreement (S-CVI/UA) was 0.20, indicating limited universal agreement. Two items (Items 5 and 6) received lower ratings, which may reflect contextual or interpretive ambiguities and potential issues with clarity or cultural applicability.

Table 2.

Item relevance ratings by population health experts

| Item | Expert 1 | Expert 2 | Expert 3 | Expert 4 | Expert 5 | Expert 6 | Expert 7 | Expert 8 | Expert 9 | Experts in agreement | I-CVI | UA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 1.00 | 1 |

| Q2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0.89 | 0 |

| Q3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0.89 | 0 |

| Q4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0.89 | 0 |

| Q5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0.56 | 0 |

| Q6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0.67 | 0 |

| Q7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0.89 | 0 |

| Q8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0.89 | 0 |

| Q9 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0.89 | 0 |

| Q10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 1.00 | 1 |

| S-CVI/ Average | 0.86 | - | ||||||||||

| S-CVI/UA | - | 0.20 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: I-CVI, Item-level content validity index; S-CVI, Scale-level content validity index; S-CVI/Average, Scale-level content validity index based on the average method; UA, Universal agreement score; S-CVI/UA, Scale-level content validity index based on the universal agreement method

The lay participants found CHAI generally easy to understand and complete. However, several respondents identified issues with Question 10, particularly the phrase “health changes,” which was perceived as ambiguous. Some participants were unclear about whether the item referred to persisting with health-related actions despite not seeing immediate benefits or adhering to health advice even if it initially made them feel unwell.

Phase two

A total of 572 completed responses were received. The demographics of the respondents are summarised in Table 3. The mean age was 47.0 (SD = 16.6). A total of 51.9% of the respondents were female and majority were Chinese (69.1%), followed by Malay (17.0%), then Indian (9.8%) and Others (4.2%). This closely models after the most recent Singapore 2024 population estimate [23]. More than half of the sample had one or more chronic disease (54.4%) having one or more chronic disease. While polyclinics in Singapore are often associated with chronic disease management, they also provide a wide range of services including acute care, preventive screenings, vaccinations and health counselling. Hence, individuals without chronic conditions also frequently utilize these services for episodic or preventive health needs, explaining the sizable proportion (45.6%) of participants without chronic disease in our sample.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study respondents (n = 572)

| Variable | Baseline analysis (n = 572)^ | Singapore 2024 population estimate |

|---|---|---|

|

Age (mean (SD)), years 21–44 45–64 ≥65 |

47.0 (16.6) 263 (46.0%) 209 (36.5%) 100 (17.5%) |

43.7 33.3 22.9 |

|

Gender Male Female |

275 (48.1%) 297 (51.9%) |

48.3 51.7 |

|

Ethnicity Chinese Malay Indian Others |

395 (69.1%) 97 (17.0%) 56 (9.8%) 24 (4.2%) |

75.5 12.5 8.7 3.3 |

|

BMI (mean (SD)), kg/m2 <23 23-27.5 >27.5 |

25.4 (5.2) 193 (33.7%) 218 (38.1%) 161 (28.1%) |

|

|

Housing type HDB 1/2 room HDB 3 room HDB 4 room HDB 5 room/Executive flat Condominium/private apartment Landed property |

19 (3.3%) 40 (7.0%) 184 (32.2%) 202 (35.3%) 91 (15.9%) 36 (6.3%) |

|

|

Monthly personal income* <=1,000 1,000–2,999 3,000–4,999 5,000–6,999 7,000–9,999 >=10,000 |

164 (28.7%) 90 (15.7%) 138 (24.1%) 76 (13.3%) 63 (11.0%) 41 (7.2%) |

|

|

Highest education level No formal education Primary Secondary Post-secondary (non-tertiary) Diploma Bachelor’s degree Masters and above |

4 (0.7%) 11 (1.9%) 114 (19.9%) 94 (16.4%) 136 (23.8%) 161 (28.1%) 52 (9.1%) |

|

|

Presence of chronic disease No Yes |

261 (45.6%) 311 (54.4%) |

|

|

Has diabetes No Yes |

469 (82.0%) 103 (18.0%) |

|

|

Has hypertension No Yes |

415 (72.6%) 157 (27.4%) |

|

|

Has hyperlipidemia No Yes |

409 (71.5%) 163 (28.5%) |

|

|

Has other chronic disease No Yes |

513 (89.7%) 59 (10.3%) |

|

|

Has multi-morbidity (≥ 3 chronic conditions) No Yes |

518 (90.6%) 54 (9.4%) |

|

|

Self-rated general health† Excellent Very good Good Fair Poor |

19 (3.3%) 123 (21.5%) 292 (51.0%) 134 (23.4%) 4 (0.7%) |

|

| CHAI (mean (SD)) | 77.9 (10.9) | |

| EQ-5D-5 L index (mean (SD)) | 0.894 (0.163) | |

| EQ-VAS (mean (SD)) | 77.0 (12.7) | |

| MHLC (mean (SD)) | 26.1 (3.9) |

^Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding

*In Singapore dollars

†SF-36 Item 1

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; CHAI, Community Health Activation Index; MHLC, Multidimensional Health Locus of Control; SD, Standard Deviation

The mean overall CHAI score for the participants was 77.9 (SD = 10.9).

The responses for the different CHAI items were unevenly distributed for all 10 items (refer to Table S2 in Appendix). All 572 responses were complete and there was no missing data. Of the six possible responses, “strongly disagree” was the least used by participants while “agree” and “strongly agree” were the most frequently selected option.

Structural validity

Structural validity was examined using EFA with principal axis factoring and varimax rotation indicated a unidimensional factor structure, with strong factor loading for all items (refer to Table S3 in Appendix). Communality values for several items, notably Item 1, were below 0.30, suggesting lower shared variance with the overall factor. This has been flagged for further investigation.

Barlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 2140, df = 45, p < 0.001) and KMO Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) was 0.857, and all items had individual MSA values > 0.80 (Table S4), indicating suitability for factor analysis. The correlations among the 10 questionnaire items ranged from r = 0.114 to r = 0.622 (refer to Table S5 in Appendix). Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency was 0.85, indicating strong internal consistency.

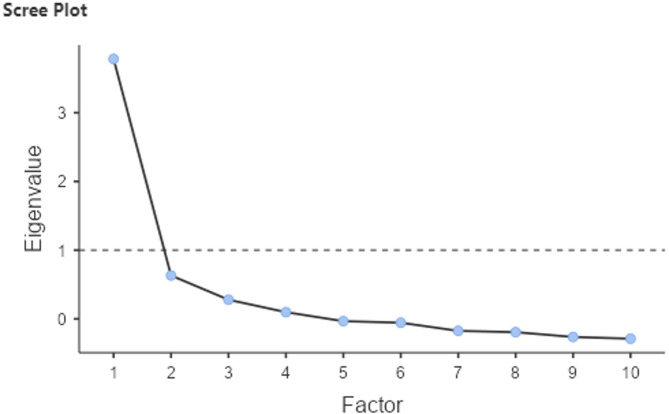

EFA identified two factors with eigenvalues > 1. Factor 1 explained 20.7% of the variance, and Factor 2 explained 19.1%, yielding a cumulative variance explained of 39.8%. While this is below the conventional 50% threshold often cited in psychometric research, the extracted factors showed strong internal consistency and were conceptually coherent.

The scree plot (Fig. 1) further supports unidimensionality with a clear elbow at Factor 1, where the eigenvalue drops sharply and levels off, suggesting that a single factor best explains the variance in the data. Accordingly, we retained a one-factor solution to maintain theoretical parsimony and alignment with the original CHAI development [11].

Fig. 1.

Scree plot from exploratory factor analysis showing a single dominant factor with an eigenvalue above 1, supporting a unidimensional structure

Construct validity

Convergent validity was supported by moderate correlations between CHAI scores and theoretically related constructs. There was a moderate, positive correlation with the MHLC internal subscale (Pearson’s r = 0.449, p < 0.001), while CHAI scores only exhibited a small to moderate positive correlation with the EQ-5D-5 L index (Pearson’s r = 0.171, p < 0.001) and EQ-5D VAS (Pearson’s r = 0.344, p < 0.001), as seen in Table 4. These findings are consistent with the expectation that health activation is conceptually distinct from general health status but related to internal health beliefs, and they align with our hypothesis that higher health activation is modestly associated with better perceived HRQoL.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix for convergent validity of CHAI, MHLC, EQ-5D-5 L and EQ VAS using pearson’s r

| CHAI | MHLC | EQ-5D-5 L | EQ VAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHAI | - | |||

| MHLC | 0.449*** | - | ||

| EQ-5D-5 L | 0.171*** | 0.040 | - | |

| EQ VAS | 0.344*** | 0.184*** | 0.390*** | - |

Legend: *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001

In terms of known-groups validity, as shown in Table 5, CHAI scores significantly differed across key health-related variables. Individuals with lower income and those with lower education had higher CHAI scores (p = 0.013, and p < 0.001 respectively) with a small effect size (0.015 and 0.024 respectively). Similarly, participants with at least one chronic disease (p = 0.017) and diabetes (p = 0.013) had significantly higher CHAI scores with a small effect size (0.200 and 0.271 respectively). Lastly, participants who reported either “excellent” or “very good” for the perceived general health status had a higher mean CHAI score (81.2 vs. 76.7, p < 0.001) with moderate effect size (0.423).

Table 5.

CHAI scores and demographic/health-related variables

| Variable | n (%) | Mean CHAI score (SD)^ | p-value~ | Effect size# |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender Female Male |

297 (51.9) 275 (48.1) |

78.6 (10.7) 77.1 (11.1) |

0.113 | 0.133 |

|

Age <65 years old ≥65 years old |

472 (82.5) 100 (17.5) |

77.5 (10.4) 79.7 (12.9) |

0.112 | 0.203 |

|

BMI Not overweight Overweight |

193 (33.6) 379 (66.3) |

77.4 (10.6) 78.1 (11.1) |

0.515 | 0.058 |

|

Ethnicity Chinese Malay Indian or other ethnicity |

395 (69.1) 97 (17.0) 80 (14.0) |

77.4 (10.8) 78.0 (10.3) 80.1 (11.8) |

0.116 | 0.008 |

|

Housing type public Private |

445 (77.8%) 127(22.2%) |

78.2 (11.2) 76.7 (9.8) |

0.211 | 0.126 |

|

Monthly personal income* <$1,000 $1,000–7,000 ≥$7,000 |

164 (28.7) 304 (53.1) 104 (18.2) |

79.8 (12.1) 77.4 (10.3) 76.0 (10.2) |

0.013 | 0.015 |

|

Highest education level Secondary and below1 Post-secondary/Diploma University graduate and above |

129 (22.6) 230 (40.2) 213 (37.2) |

79.8 (12.9) 78.7 (9.7) 75.7 (10.4) |

< 0.001 | 0.024 |

|

Presence of chronic disease No Yes |

261 (45.6) 311 (54.4) |

76.7 (10.2) 78.8 (11.4) |

0.017 | 0.200 |

|

Has diabetes No Yes |

469 (82.0) 103 (18.0) |

77.3 (10.8) 80.3 (11.3) |

0.013 | 0.271 |

|

Has hypertension No Yes |

415 (72.6) 157 (27.4) |

77.3 (10.5) 79.3 (11.8) |

0.056 | 0.180 |

|

Has hyperlipidemia No Yes |

409 (71.5) 163 (28.5) |

77.8 (10.8) 78.0 (11.3) |

0.856 | 0.017 |

|

Has multi-morbidity (≥ 3 chronic conditions) No Yes |

518 (90.6) 54 (9.4) |

77.9 (10.7) 77.3 (12.7) |

0.673 | 0.060 |

|

Self-rated general health† Excellent/Very good Good/Fair/Poor |

142 (24.8) 430 (75.2) |

81.2 (9.7) 76.7 (11.1) |

< 0.001 | 0.423 |

^Transformed scores 0-100

~T-test and ANOVA as appropriate

#Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s D and  for T-test and ANOVA respectively

for T-test and ANOVA respectively

*In Singapore dollars

1Secondary education level refers to completion of secondary school in Singapore, roughly equivalent to Grades 7–10 elsewhere

†SF-36 Item 1

Abbreviations: CHAI, Community Health Activation Index; SD, Standard Deviation; BMI, Body Mass Index

Bold values indicate a significant p ≤ 0.05

No significant differences were observed for gender, age, BMI, ethnicity, housing type, hypertension, hyperlipidemia or multi-morbidity.

Test-retest reliability

A total of 32 participants were recruited for test-retest reliability, of which 21 participants had a stable health status after completing a second CHAI assessment within 1–2 weeks. The ICC (3,1) was 0.802 (95% CI: 0.544–0.911), reflecting good stability over time. This suggests that CHAI scores remain consistent and reliable when reassessed within a short period.

Discussion

The findings of the study suggest that the CHAI has reasonable overall measurement properties among community-dwelling adults in Singapore. Specifically, the content validity assessment indicates adequate item relevance, while exploratory factor analysis and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85) support a coherent unidimensional structure. Moderate correlations with the internal locus of control (MHLC) and weaker correlations with HRQoL measures provide evidence of convergent validity. Finally, test-retest reliability indicates good score stability over a short-term interval.

Our findings regarding content validity are broadly in line with the original CHAI validation [11] and subsequent research in Western populations [17]. Although most CHAI items received high item-level ratings, some showed lower agreement. Such item-level variations highlight the importance of localized refinements when validating patient-reported measures. Prior research also emphasizes the importance of linguistic and cultural tailoring for patient-reported outcome measures [38]. Our cognitive interviews identified certain items with cultural and linguistic ambiguities, suggesting that more contextually adapted phrasing may improve instrument clarity and sensitivity. Future investigations could incorporate additional qualitative procedures such as cognitive debriefing or item relevance reviews across diverse ethnic or language groups to ensure cultural equivalence.

The unidimensional factor structure observed is consistent with the original development of CHAI [11]. While this supports the conceptualization of health activation as a single latent construct, it also raises questions about the breadth of construct coverage relative to the more established PAM, which categorizes activation into progressive levels (albeit this reflects scoring cut-offs rather than broader theoretical coverage). If CHAI items primarily captures a subset of the domains driving true health activation (e.g., knowledge, skills, confidence), its unidimensionality may indicate narrower construct coverage rather than comprehensive measurement of all potential activation facets. Nonetheless, our factor analytic results demonstrate strong factor loadings, suggesting that a single-factor structure is an appropriate model for use in Singapore.

The moderate correlation between CHAI and the internal locus of control subscale of the MHLC (r = 0.449) aligns with the original validation study [11], indicating that CHAI is meaningfully associated with self-perceived control over health. In contrast, weak to moderate correlations with HRQoL (r = 0.171–0.344) support the notion that activation, while related to perceived health status, represents a distinct construct. The small correlation between CHAI and the EQ-5D-5L, compared to the moderate correlation with EQ-VAS, may be due to the nature of the instruments. The EQ-5D-5L is a multidimensional measure assessing five specific health domains, not all of which directly reflect health motivation or engagement. In contrast, the EQ-VAS is a unidimensional self-rating of overall health, which may align more closely with a person’s general sense of control, confidence, and activation. These associations largely reflect the absence of a universally accepted “gold standard” for health activation; while measures such as MHLC and HRQoL contribute valuable insights, they do not fully encapsulate this multidimensional concept [9]. Therefore, future research could compare it against other validated activation measures to further refine convergent validity findings; notably, PAM licensing explicitly prohibits formal validation against similar measures.

CHAI appeared to differentiate between subgroups based on self-reported health status. Known-group comparisons revealed that CHAI distinguished individuals reporting different levels of general health and certain chronic conditions. However, contrary to previous findings in patient activation literature [3, 11, 33], participants with chronic disease had higher mean CHAI scores than those without. This may reflect the effects of health counselling in primary care settings, which enhances patients’ motivation for self-care and activation as part of standard chronic disease management. Furthermore, national public health campaigns have emphasized the risks associated with conditions such as diabetes, potentially heightening risk perception and encouraging proactive engagement [39]. In our study, individuals with lower education may have been more exposed to community-based health initiatives or received more structured guidance through chronic disease programs, which led to higher CHAI scores, albeit prior literature associated higher education with greater health activation [17]. However, we caution against overinterpretation given that health literacy, a potentially confounding construct, was not directly assessed in this study. Educational attainment may not fully capture functional or critical health literacy, and future studies should incorporate validated health literacy instruments to clarify these relationships.

Nonetheless, the effect sizes for many subgroup differences were relatively small, implying that while CHAI can detect statistically significant differences, the practical significance of these differences in routine care may be limited. This implies that CHAI may be more useful for broad screening or identifying individuals at the extremes of activation levels, rather than for precise stratification of closely related subgroups. Nonetheless, even small effect sizes contribute additional validity evidence, reinforcing CHAI’s ability to capture meaningful distinctions in health activation.

The test-retest reliability estimate of ICC = 0.802 indicates that CHAI produces stable scores among adults reporting no change in general health over a one- to two-week period. This finding is comparable to previous reports of good to excellent reliability in the US [11]. The sample size, although small, does align with prior reliability studies [40]. Nevertheless, the relatively small number of stable participants (n = 21) contributed to a wide confidence interval, highlighting a need for caution in interpreting the precision of the estimate. An additional analysis using responses from a separate SF-36 item (Item 2) was attempted but was limited by the small number of respondents (n = 11) who reported no change in health status. Item 2 asks respondents to compare their current health to one year ago, introducing recall bias and subjective interpretation. As a result, Item 2 may lack sensitivity to subtle changes, making it inadequate for assessing stable health states over short intervals [41].

Overall, the CHAI appears to be a promising, succinct, and freely available measure of health activation in non-Western contexts. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, although our quota-based sample aligns with national census distributions, the cross-sectional design restricts inferences about responsiveness—an important property of measures used in longitudinal studies. Second, the non-random sampling approach may limit the generalizability of CHAI’s psychometric properties beyond the study population. Third, participants recruited from primary care settings may differ in activation levels from the general population, affecting the generalizability to the community. Fourth, the test-retest stability sample was small relative to the baseline cohort, limiting the precision of reliability estimates and the ability to explore intra-observer variability. Future studies with larger follow-up samples will allow for more precise estimates and enable more robust subgroup analyses. Fifth, mode-of-administration differences (paper-based and self-administered for the test survey as opposed to remotely administered telephone interview for the retest) may have impacted reliability estimates and should be accounted for in future studies. Sixth, while overall content validity is acceptable, our findings suggest that refinement of certain items may improve item clarity and cultural alignment. Further evaluation of linguistic and cultural adaptability is warranted, particularly for minority groups and non-English speakers. Seventh, while the scree plot and loading pattern support a unidimensional solution, lower communalities for certain items (particularly Item 1) may indicate weaker contributions to the latent construct and warrant future revision. Eighth, as explained earlier, CFA was not conducted due to our study aims, sample size limitations and the lack of a split-sample design. Nevertheless, future studies should perform CFA to confirm the factor structure and evaluate model fit. Ninth, our analyses did not assess discriminant validity, which should be included in future research using unrelated psychological constructs. Finally, as CHAI relies on self-reported responses, there is a potential risk of response bias, such as social desirability effects, which could influence participants’ responses.

Despite these constraints, our results indicate that CHAI is both psychometrically sound and practical for use in Singapore. Future CFA and longitudinal studies should examine whether CHAI can predict improvements in self-management behaviors or clinical outcomes over time. For instance, tracking newly diagnosed patients with diabetes may clarify the temporal relationship whether increasing activation is associated with disease control and progression. Integrating CHAI into routine clinical workflows may also help identify patients who would benefit most from targeted interventions, such as health coaching or educational programs, thereby optimizing resource allocation in chronic disease management.

Conclusion

In summary, the CHAI demonstrates acceptable psychometric properties and considerable potential as a practical, cost-effective measure of health activation in Singapore’s primary care settings. Its concise format facilitates broad implementation and could inform population health interventions, particularly for individuals in the primary care setting and those with chronic diseases. Nonetheless, our findings highlight the need for further refinement of certain items to enhance cultural relevance and clarity. Future work should include CFA and longitudinal validation to establish its predictive utility, enhance its sensitivity across diverse subgroups and evaluate its role in guiding patient-centered care and public health strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the kind and generous staff at Choa Chu Kang and Bukit Panjang National University Polyclinics (NUP) for hosting and accommodating the research team.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to all the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted. No writing assistance was obtained in the preparation of the manuscript. The manuscript, including related data, figures and tables has not been previously published, and the manuscript is not under consideration elsewhere.QXN: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. JGJL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis. LJC: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Supervision. GCHK: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision. NL: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Supervision.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions. Data are however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of the institutional review board (IRB) of the National University of Singapore (NUS).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Department Ethics Review Committee, National University of Singapore (study number SSHSPH-269), and all participants provided informed consent before interviews commenced. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the research process, and no identifying information was included in the transcripts or final report.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Justin Guang Jie Lee and Qin Xiang Ng contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Hibbard JH, Gilburt H. (2014). Supporting people to manage their health An introduction to patient activation. https://assets.kingsfund.org.uk/f/256914/x/d5fbab2178/supporting_people_manage_their_health_2014.pdf

- 2.Janamian T, Greco M, Cosgriff D, Baker L, Dawda P. Activating people to partner in health and self-care: use of the patient activation measure. Med J Aust. 2022;216(Suppl 10):S5–8. 10.5694/mja2.51535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowles JB, Terry P, Xi M, Hibbard J, Bloom CT, Harvey L. Measuring self-management of patients’ and employees’ health: further validation of the patient activation measure (PAM) based on its relation to employee characteristics. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(1):116–22. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1443–63. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hibbard JH, Tusler M. Assessing activation stage and employing a next steps approach to supporting patient self-management. J Ambul Care Manage. 2007;30(1):2–8. 10.1097/00004479-200701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosen DM, Schmittdiel J, Hibbard J, Sobel D, Remmers C, Bellows J. Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? J Ambul Care Manage. 2007;30(1):21–9. 10.1097/00004479-200701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–26. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng QX, Liau MYQ, Tan YY, Tang ASP, Ong C, Thumboo J, Lee CE. A systematic review of the reliability and validity of the patient activation measure tool. Healthcare. 2024;12(11):1079. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/12/11/1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngooi BX, Packer TL, Kephart G, Warner G, Koh KW, Wong RC, Lim SP. Validation of the patient activation measure (PAM-13) among adults with cardiac conditions in Singapore. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(4):1071–80. 10.1007/s11136-016-1412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf MS, Smith SG, Pandit AU, Condon DM, Curtis LM, Griffith J, O’Conor R, Rush S, Bailey SC, Kaplan G, Haufle V, Martin D. Development and validation of the consumer health activation index. Med Decis Mak. 2018;38(3):334–43. 10.1177/0272989x17753392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arvanitis M, Opsasnick L, O’Conor R, Curtis LM, Vuyyuru C, Yoshino Benavente J, Bailey SC, Jean-Jacques M, Wolf MS. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine trust and hesitancy among adults with chronic conditions. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101484. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey SC, Serper M, Opsasnick L, Persell SD, O’Conor R, Curtis LM, Benavente JY, Wismer G, Batio S, Eifler M, Zheng P, Russell A, Arvanitis M, Ladner DP, Kwasny MJ, Rowe T, Linder JA, Wolf MS. Changes in COVID-19 knowledge, beliefs, behaviors, and preparedness among High-Risk adults from the onset to the acceleration phase of the US outbreak. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3285–92. 10.1007/s11606-020-05980-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isautier JM, Copp T, Ayre J, Cvejic E, Meyerowitz-Katz G, Batcup C, Bonner C, Dodd R, Nickel B, Pickles K, Cornell S, Dakin T, McCaffery KJ. People’s experiences and satisfaction with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic in australia: Cross-Sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e24531. 10.2196/24531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehawej J, Tran KT, Filippaios A, Paul T, Abu HO, Ding E, Mishra A, Dai Q, Hariri E, Howard Wilson S, Asaker JC, Mathew J, Naeem S, Mensah Otabil E, Soni A, McManus DD. Self-reported efficacy in patient-physician interaction in relation to anxiety, patient activation, and health-related quality of life among stroke survivors. Ann Med. 2023;55(1):526–32. 10.1080/07853890.2022.2159516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morawski K, Ghazinouri R, Krumme A, McDonough J, Durfee E, Oley L, Mohta N, Juusola J, Choudhry NK. Rationale and design of the medication adherence improvement support app for Engagement-Blood pressure (MedISAFE-BP) trial. Am Heart J. 2017;186:40–7. 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flight I, Harrison N, Symonds J, Young EL, G., Wilson C. Validation of the consumer health activation index (CHAI) in general population samples of older Australians. PEC Innov. 2023;3:100224. 10.1016/j.pecinn.2023.100224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health Singapore. (2023). Action Plan for Successful Ageing. 2023. Accessed Feb 17, 2025. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/others/resources-and-statistics/action-plan-for-successful-ageing

- 19.Ministry of Health Singapore. (2022). National Population Health Survey (NPHS) 2022 Report. Accessed Feb 18, 2025. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/others/resources-and-statistics/nphs-2022

- 20.Wallston KA, Wallston BS, DeVellis R. Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health Educ Monogr. 1978;6(2):160–70. 10.1177/109019817800600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gagnier JJ, Lai J, Mokkink LB, Terwee CB. COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(8):2197–218. 10.1007/s11136-021-02822-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Yusoff MSB. ABC of content validation and content validity index calculation. Educ Med J. 2019;11(2):49–54. 10.21315/eimj2019.11.2.6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singapore Department of Statistics. (2025). Singapore Residents By Age Group, Ethnic Group And Sex, At End June, Annual. Accessed Feb 18, 2025. Available from: https://data.gov.sg/datasets/d_3cf667d761b4bdc6d4d3d3aeec37dea5/view

- 24.Comrey AL, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1992.

- 25.Kalmijn W. (2023). Linear Scale Transformation. In F. Maggino, editor, Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (pp. 3924–3926). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-031-17299-1_3659

- 26.Park M, Jung HS. Measuring health activation among foreign students in South korea: initial evaluation of the feasibility, dimensionality, and reliability of the consumer health activation index (CHAI). Int J Adv Cult Technol. 2020;8(3):192–7. 10.17703/IJACT.2020.8.3.192. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, Bonsel G, Badia X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo N, Vasan Thakumar A, Cheng LJ, Yang ZH, Rand K, Cheung YB, Thumboo J. (In press). Developing the EQ-5D-5L value set for Singapore using the ‘lite’ protocol. PharmacoEconomics.

- 30.Cheng LJ, Tan RL, Luo N. Measurement properties of the EQ VAS around the globe: A systematic review and Meta-Regression analysis. Value Health: J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2021;24(8):1223–33. 10.1016/j.jval.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng YS, Kohlmann T, Janssen MF, Buchholz I. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(3):647–73. 10.1007/s11136-020-02688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallston KA, Stein MJ, Smith CA. Form C of the MHLC scales: a condition-specific measure of locus of control. J Pers Assess. 1994;63(3):534–53. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918–30. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polit DF. Getting serious about test-retest reliability: a critique of retest research and some recommendations. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(6):1713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(1):30–46. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, Erikson P. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ow Yong LM, Koe LWP. War on diabetes in singapore: a policy analysis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(1):15. 10.1186/s12961-021-00678-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bujang MA, Omar ED, Foo DHP, Hon YK. (2024). Sample size determination for conducting a pilot study to assess reliability of a questionnaire. Restor Dent Endod, 49(1), e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Hopman WM, Berger C, Joseph L, Towheed T, VandenKerkhof E, Anastassiades T, Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Brown JP, Hanley DA, Papadimitropoulos EA, CaMos Research Group. The natural progression of health-related quality of life: results of a five-year prospective study of SF-36 scores in a normative population. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(3):527–36. 10.1007/s11136-005-2096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions. Data are however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of the institutional review board (IRB) of the National University of Singapore (NUS).