Abstract

Sturge-Weber Syndrome (SWS) is a congenital neurovascular disorder caused by a somatic mosaic mutation in the R183Q GNAQ gene and characterized by capillary-venous malformations of the brain, skin, and eyes. Clinical manifestations include facial port-wine birthmark, glaucoma, seizures, headache or migraine, hemiparesis, stroke or stroke-like episodes, developmental delay, behavioral problems, and hormonal deficiencies. SWS requires careful monitoring, management, and early identification to improve outcome and prevent neurological deterioration. Over the last 25 years, biomarkers have been developed to improve early diagnosis and prognosis and allow for the monitoring of clinical status and treatment response. Importantly, advancements in biomarker research may enable presymptomatic treatment for infants with SWS. This review summarizes current, ongoing, and potential future SWS biomarker studies. These biomarkers, in combination with clinical data, offer a rich source of data for rare disease research leveraging machine learning in future research.

Keywords: Sturge-Weber syndrome, Neurocutaneous syndrome, GNAQ, Biomarker, Urine angiogenic factor, Vascular biomarkers, MRI, QEEG, EEG biomarkers, Neuroimaging biomarkers

Introduction

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a capillary venous malformation disorder of the brain, skin, and eyes, occurring in one in every 20,000–50,000 newborns [1]. Caused by a somatic mosaic mutation in the R183Q GNAQ gene during fetal development [2], the main clinical features of the disorder are a facial port-wine birthmark (PWB), increased intraocular pressure (glaucoma), and impaired vasculature of the brain. The neurovascular complications of the disorder can lead to seizures, stroke/stroke-like episodes, hemiparesis, intellectual disability, headaches, and migraine [3]. Prognosis is known to be partially dependent on the extent of brain involvement and the age of seizure onset [1].

Newborns present with a facial port-wine birthmark on the upper face, indicating their risk of SWS brain involvement and glaucoma due to vascular and structural abnormalities of the eye [4]. Infants with SWS brain involvement are at high risk for seizures, venous stroke and stroke-like episodes, brain atrophy and calcification, focal neurologic deficits, and cognitive impairments. Recent research has demonstrated that early diagnosis and treatment prior to the onset of seizures can prevent or delay seizures and improve neurologic functions by two years of age [5]. The Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC) network has supported research over the last 25 years to develop diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers to improve clinical care and clinical trials for this devastating and rare disorder. Important progress has been made, and ongoing research is bringing novel treatment strategies to these patients and their families.

Recent reviews have discussed the pathophysiology and molecular pathways connecting the underlying most common somatic mosaic R183Q GNAQ to the vascular malformations, role of seizures and stroke in progression of brain injury, clinical symptoms and signs, and both standard and novel treatment approaches [6]. Recent work has demonstrated that early intervention, before the onset of seizures in SWS, can prevent seizures and may improve outcome [5, 7, 8]. These data, along with other recent prospective and promising pilot drug trials for SWS highlight the importance of the ongoing biomarker development for SWS. The objective of this review is to summarize the literature on biomarker development for SWS, focusing on neuroimaging, electrophysiology, and angiogenic biomarker research, and to bring into focus the most urgently needed future biomarker research.

MRI neuroimaging biomarker development

Diagnostic MRI neuroimaging biomarker development

Prior to MRI, computed tomography (CT) was used for diagnosis of SWS brain involvement; head CT demonstrates brain atrophy, and the calcification and enlargement of the choroid plexus. Head CT as a clinical biomarker for SWS is problematic for several reasons. The use of radiation is particularly concerning because the R183Q GNAQ mutation is a driver mutation (oncogene), and the use of ionizing radiation may further increase the risk of additional mutations in affected cells. Furthermore, a child with a facial port-wine birthmark presenting with first seizures and given a head CT is still regularly misdiagnosed with cerebral hemorrhage. Therefore, where available, a limited MRI of the brain is preferred and is increasingly replacing head CT for diagnosis in the emergent setting [9, 10].

SWS brain involvement is diagnosed by identifying abnormal leptomeningeal enhancement on T1-weighted post contrast MRI. Leptomeningeal enhancement most likely results from disruption to the blood brain barrier and impaired local cerebral capillary venous blood flow [11]. The diagnostic accuracy of T1-weighted post contrast MRIs has been studied in infants with SWS [12]; specificity is very high, however 75% of infants who did in fact have brain involvement (on later imaging) were not detected on early contrast-enhanced MRI imaging (poor sensitivity). Therefore, an important goal of ongoing research is to improve early diagnostic MRI neuroimaging. For over 20 years, our Center has evaluated ~ 1,000 patients and has been successful using MRI > 1 y.o. to exclude SWS brain involvement.

Susceptibility/Risk neuroimaging biomarker development

Susceptibility/risk biomarkers are those that indicate an increased or decreased chance of developing a disease and can be used to identify patients who do not yet have the clinical presentation of the disease, which can be important when considering presymptomatic treatment (as has been shown in patients with SWS) [5, 7, 8, 13]. Various MR sequences have been suggested to aid the effort to presymptomatically identify and treat babies at risk for SWS. Bar and colleagues (2020) retrospectively compared MRIs of asymptomatic infants with a facial PWB before three months of age to after 9 months of age to assess other “indirect” indictors of brain involvement and injury (white matter abnormalities, cortical atrophy, and choroid plexus enhancement) along with leptomeningeal enhancement [14]. This small retrospective study demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of SWS brain involvement; these data require confirmation in another cohort and prospective validation. Arterial spin labeling (ASL) is another MRI technique that does not require contrast and may capture the changes in blood perfusion that occur due to vascular reorganization in patients with SWS. This study in young children with SWS suggested that hyperperfusion occurs early in the disorder as the compensatory reorganization takes place, whereas hypoperfusion occurs later in the disease course [15].

The main issue with these alternative approaches to diagnosis is that unless suspicious MR imaging is confirmed with additional sedated, contrast-enhanced MR imaging, patients without actual SWS brain involvement may be inappropriately started on presymptomatic treatment [14] and parents can be reluctant to stop treatment until neuroimaging after a year of age confirms the presence or absence of brain involvement. Therefore, future research needs to confirm which indirect/alternative signs on MR imaging best enable early, accurate diagnosis. Repeated sedated contrast-enhanced MRIs include the low but uncertain risks of gadolinium contrast deposition and sedation; non-sedated, feed-and-wrap neonatal MRIs are increasingly being utilized, given promising results with presymptomatic treatment, making this challenge particularly urgent. Future studies are needed which apply machine learning algorithms for diagnosis of SWS brain involvement in presymptomatic neonates. Alternatively, research with other alternative contrast agents may prove more sensitive and specific than current gadolinium enhancement.

Prognostic MRI neuroimaging biomarker development

A derivation of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) called apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) mapping may have predictive power for seizure onset in patients with presymptomatic SWS. Normative ADC maps created by Pinto and colleagues can quantify the magnitude of water diffusion in patients with SWS [16]. When comparing ADC values to normative age-specific maps, 7/8 (88%) subjects with SWS had abnormal ADC values, specifically in regions of brain involvement and later developed seizures [16]. This small retrospective study requires reproduction and confirmation prospectively. Applying machine-learning artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to brain MR imaging, from infants with known SWS brain involvement, to predict early seizure onset/symptoms and later neurocognitive function is a current focus in SWS research [17].

Monitoring neuroimaging biomarker development

Most recent neuroimaging biomarker studies in SWS have focused on various MRI neuroimaging sequences [18, 19]. However, other longitudinal neuroimaging studies have focused on monitoring biomarkers used to detect the change in degree or extent of a disease [20]. Head CT and brain non-contrast MRI both demonstrate increasing calcification and brain atrophy in patients over time, and evidence that these studies, when quantified, correlate with the severity of neurologic and cognitive impairments including seizure severity [21]. However, the utility of MRI for clinical or drug trial monitoring is limited by the expense, need for sedation, and the observation that clinical changes in patients often are associated with stable MRI neuroimaging [22].

Single-photon computed tomography (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET) have been useful for understanding the evolution of brain injury and atrophy in SWS. MRI, SWI, and PET have been used together to show that calcification volume growth is associated with glucose hypometabolism [23]. Pilli and colleagues found that calcification was associated with longer seizure duration, earlier seizure onset, and lower cognitive scores [23]. Additionally, regions of calcification and hypoperfusion have been found to be significantly correlated with symptoms of hemiparesis in patients with SWS as measured by the SWS Neuroscore [24]. The SWS Neuroscore and neuropsychological testing both quantitatively measure neurologic and cognitive status, as well as effectively validate outcomes due to structural and functional abnormalities detected on MRI.

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET studies in the past have provided important insights. Decreased glucose metabolism is associated with seizure severity and cognitive deficits in SWS [23]. FDG PET has also shown worsening of glucose metabolism over the first few years of life and stabilization around 4 years of age [25]. Glucose hypometabolism has demonstrated to improve with sustained seizure control [26]. Seizures further complicate cerebral perfusion, and ictal SPECT has been used to observe perfusion dynamics during active seizures in patients with SWS. Two different groups reported the key observation that during ictal SPECT, perfusion increases in affected brain regions were lower than expected or even decreased to ischemic levels; unpublished clinical data from other groups support this observation [26, 27]. However, these techniques are also limited in their ability to visualize the actual leptomeningeal angiomatosis and expose children to radiation [28]. Use of SPECT and FDG PET is therefore limited clinically to the workup of children with medically refractory seizures before epilepsy surgery [29].

EEG biomarker development

Monitoring EEG biomarker development

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a noninvasive diagnostic test that measures and records the brain’s electrical activity with millisecond-level temporal resolution. EEG is widely accessible, easy to perform, repeatable, and does not necessitate sedation making it an appealing investigative tool. EEG data are analyzed through two primary methods: qualitative analysis and quantitative analysis. Qualitative analysis involves the visual inspection of EEG waveforms and patterns to identify abnormalities or features indicative of neurological conditions. This can include the detection of epileptiform discharges, EEG asymmetries (such as focal slow activity), rhythmic or periodic patterns. In contrast, quantitative EEG (qEEG) employs mathematical and statistical methods to analyze EEG data objectively, with the goal of identifying meaningful patterns and trends that might not be easily discernible through visual examination. Traditional EEG analysis involves qualitative review; however, in recent decades, with the advancements in technology, there has been a growing adoption of quantitative analysis methods.

EEG is widely used in neurology, with its most common applications being the diagnosis, classification, localization, and monitoring of seizures. Seizures are one of the most prevalent neurological manifestations in individuals with SWS, occurring in up to 75% of cases before the age of 1, with a median onset of around 6 months [30]. Therefore, EEG plays a crucial role in the evaluation and management of SWS, aiding in early detection and guiding treatment. Several different abnormal EEG findings have been described in SWS such as asymmetry (amplitude asymmetry, focal loss of normal background details or focal slow activity) and epileptiform discharges [31–36], which is almost always on the side of port-wine birthmark (PWB), or on the side with maximal skin involvement in individuals with bilateral PWB. Chao et al. first described a chronological progression of EEG findings in individuals with Sturge-Weber Syndrome (SWS), beginning with normal EEG patterns during infancy, followed by the emergence of focal slow activity, and eventually progressing to epileptiform activity [34]. This progressive sequence was later corroborated in a larger cohort of children and adults with SWS by Kossoff et al. [36]. In their study, normal EEGs in younger children evolved over time, typically within approximately one year, into EEG asymmetries characterized by focal slowing and a loss of normal background activity.

The first report of quantitative EEG (qEEG) analysis in patients with Sturge-Weber Syndrome (SWS) was published in 2002. In this study, Jansen et al. demonstrated EEG beta band asymmetry, with reduced beta activity observed on the side of the affected hemisphere, after diazepam administration [37]. In 2007, Hatfield et al. introduced the EEG laterality score, a quantitative measure designed to assess power asymmetry across various frequency bands [38]. The laterality score is calculated using the formula: (ipsilateral − contralateral)/(ipsilateral + contralateral), applied to pairs of symmetrical bipolar channels. This score demonstrated a strong correlation with both the severity of SWS and the degree of brain MRI asymmetry.

Susceptibility/Risk EEG biomarker development

Since MRI neuroimaging in young infants have issues with low sensitivity, qEEG has been studied to screen for SWS brain involvement [12]. The SWS qEEG laterality score biomarker was retrospectively applied to a small cohort to predict which infants with PWB were at the highest risk for developing SWS [39]. In subsequent testing with a larger sample, the qEEG biomarker brain involvement in infants born with facial PWB, yielding a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 81% [40]; the SWS qEEG laterality score added approximately 20% additional predictive information, as compared to prediction based on the size, pattern and location of the facial PWB alone. The studies suggest that qEEG-based measures, when combined with other established risk factors such as high-risk PWB, could be used to develop risk calculators for identifying patients with PWB who are at an increased risk of developing SWS. Building on these advancements, the next crucial step would be to harness machine learning techniques to integrate high risk PWB and quantitative EEG measures, and qualitative EEG measures as well, with the goal of developing a comprehensive risk calculator for identifying patients with PWB who are at increased risk of developing SWS. The success of machine learning approaches to that end, however, would require large, well-curated datasets and the inclusion of a broad array of relevant variables to ensure robust and accurate predictive modeling.

Prognostic EEG biomarker development

Most children experience seizures by 2 years of age which is considered a key milestone in the clinical course of SWS [30]. The onset of seizures in SWS can further disrupt blood flow and cause cortical injury which in turn can worsen neurocognitive outcome [24, 41]. Early seizure onset is associated with worse seizure severity, lower IQ, increased severity of hemiparesis and worse brain injury and cognitive decline [30, 42–45]. Epileptiform discharges often precede the onset of seizures [46]. Furthermore, children with abnormal EEG findings—such as focal slow activity, epileptiform discharges, or seizures—are more likely to experience seizure onset before the age of two [5]. These results suggest that qEEG should also be developed as a prognostic biomarker for predicting seizure onset by 2 years of age, and that both clinical EEG and qEEG may be useful treatment responsive biomarkers and further study in this context is needed.

Predictive EEG biomarker development

Previous studies suggest that the somatic GNAQ mutations in SWS may lead to hyperactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, as evidenced by increased phosphorylated S6 in cutaneous and brain vascular malformations of patients with SWS. This has led to the hypothesis that mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus could offer therapeutic benefits [47]. A recent small prospective clinical trial investigating the use of sirolimus in SWS [47] for cognitive impairments in SWS suggested that qEEG analysis has the potential to serve as a biomarker for predicting stroke-like episodes. The qEEG laterality score improved, in the group experiencing a decreased duration of stroke-like episodes on sirolimus, suggesting that qEEG may be a valuable tool for predicting patients likely to benefit from treatment, classifying patients into sirolimus-responders and non-responders, and enriching later phase clinical trials with patients more likely to respond. Further study on this qEEG application is needed to establish utility as a predictive biomarker.

Pharmacodynamic EEG biomarker development

The same small study of sirolimus also suggested that EEG/qEEG may also have potential as a pharmacodynamic EEG biomarker [47]. Further study is needed to validate this, but EEG/qEEG is likely to function as a surrogate clinical endpoint or efficacy response biomarker in a clinical trial. Since acute crises in SWS can be intermittent, with months between events such as seizures or stroke-like episodes, use of EEG/qEEG could be important as a clinical outcome endpoint [5]. Further study is also needed to determine whether EEG/qEEG is a biomarker for response to aspirin or anti-seizure medications.

Angiogenic biomarker development

The somatic mosaic mutation attributed to the development of SWS, GNAQ (p.R183Q), is hypothesized to result in the aberrant downstream hyperactivation of the Ras-Raf-MAPK and PI3K-mTOR pathways [2, 11, 48–51]. It is thought that the abnormal activities of these pathways contribute to the dysregulation of endothelial cell functioning and the growth of the abnormal congenital capillary-venous malformations of the face, brain, and eyes that are characteristic of SWS [52]. Angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, are released by the mutant and surrounding vascular endothelial cells [53]into the blood and urine and are thought to be drivers of pathogenesis in SWS [54–56]. Vascular factors of particular interest in SWS and other vascular malformations identified in previous research include basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and its subtypes [53–56].

Evidence to support the investigation of urine vascular factors for use as non-invasive biomarkers in SWS comes primarily from three studies. The initial study in 2005 compared bFGF, VEGF, and MMP and its subtypes from 74 controls to groups classified as vascular tumors (n = 57), vascular malformations (n = 160), and subgroups of the classifications (i.e., capillary malformations; subgroup sizes varied from n = 8 to n = 47) [54]. This study inspired a follow-up study in SWS specifically, which consisted of 54 SWS subjects and the same 74 controls [55]. This study also included a longitudinal 1-year follow-up for 22 SWS subjects. Subsequently, a larger, longitudinal multi-site study with funding from the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium (BVMC) SWS Investigator Group [56]. The study enrolled 61 SWS subjects and collected data longitudinally, at 3 separate time points across 3 years. Further included were 38 family controls and the 74 pediatric controls from the prior two studies. The results from these studies are summarized below.

Diagnostic angiogenic biomarker development

In 2005, Marler et al. reported that high molecular weight MMPs and abnormally elevated bFGF levels (> 4000 pg/mL) were more likely to be present in the urine of subjects with vascular malformations, as compared to controls [54]. Relatedly, high molecular weight MMPs and bFGF levels were associated with increased lesion extent and disease activity in subjects with vascular malformations [54]. Other studies report similar findings, with MMPs being elevated and predictive of hemangiomas and vascular tumors, and elevated MMPs and abnormally elevated bFGF associated with SWS [55–58]. This research would suggest that elevated MMPs and bFGF are associated with various vascular malformations and vascular tumors, however these angiogenic factors, when present in the urine of patients with facial port-wine birthmark, do not aid in the specific diagnosis of SWS brain or eye involvement or in separating this vascular malformation from other vascular malformation disorders.

Monitoring angiogenic biomarker development

Sreenivasan et al. reported that MMP-9 molecules were associated with the extent of skin, brain, and eye involvement (glaucoma) when MMPs were present in the subject’s urine [55]. However, the subsequent larger study did not replicate this result [56]. Other vascular factors have yet to be associated with glaucoma progression. Reproducibility of the results between studies has been an issue; this may relate to clinical complexity such as the variability in timing of samples gathered in relationship to seizures and other acute crises, or alternatively variability resulting from shipping urine samples from multiple sites for analysis.

Prognostic angiogenic biomarker development

Longitudinally, bFGF urine levels predicted improved hemiparesis in multiple SWS subgroups, better overall neurologic outcome in males in one study, but abnormally elevated bFGF was associated with worse cognition and decreased stigma quality of life outcomes (less feelings of disapproval) in a follow up study with pediatric subjects with SWS. Basic fibroblast growth factor levels could be further developed as a prognostic biomarker; additional research is required to confirm and understand these associations [55]. Urine VEGF levels, in the third study only, was associated with better cognitive, seizure, and overall neurologic outcome [56].

Together these data suggest that urine angiogenic factors are not presently suited for clinical use as non-invasive prognostic blood biomarkers in SWS. Further studies are needed. The Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium is currently studying angiogenesis factors present in the blood to determine biomarkers for further study. Over the next few years, research is likely to provide additional insights into the development of angiogenesis factors in the blood and/or urine as biomarkers for SWS.

Conclusions and future directions

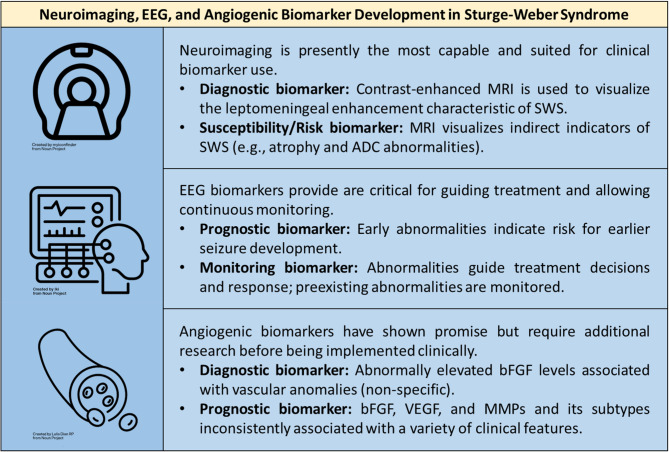

In summary, growing evidence supports the utility of EEG and MRI neuroimaging as useful biomarkers for the screening and diagnosis of SWS brain involvement, and should be further developed for prediction of outcome, monitoring of clinical status, and for treatment responses in SWS (summarized in Fig. 1). These studies each contain large amounts of data that can be quantitatively analyzed using machine learning algorithms to produce more accurate and reproducible biomarkers for these patients. Given the interactions of the abnormal cerebral vasculature, breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, and seizures that are fundamental to mechanisms of brain injury in SWS, both MRI and EEG are needed for clinical monitoring of disease progression and response to treatments. Efforts are ongoing to gather sufficient patients across multiple centers, along with well-curated clinical data, to enable implementation of AI-driven development of MRI and EEG diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Other neuroimaging biomarkers studied in SWS, including CT, SPECT and PET have a much more limited clinical role, such as in urgent care when rapid MRI is not available and in pre-surgical planning for patients with SWS. As in vivo and in vitro models are developed for SWS [11, 59, 60], it is likely that more targeted and sophisticated angiogenesis biomarkers will continue to be developed. With the advent of presymptomatic treatment options for infants with SWS, the need for biomarker development, for use in the clinic and in clinical trials, is greater than ever before.

Fig. 1.

Biomarkers in Sturge-Weber syndrome. MRI and EEG biomarkers have provided the most robust and clinically relevant biomarkers. Urine angiogenic biomarkers offer promising data for use as affordable and non-invasive biomarkers; however, additional research and replication of past research is required before it can be widely adopted and utilized clinically

Abbreviations

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- AI

Artificial intelligence

- ASL

Arterial spin labeling

- bFGF

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- BVMC

Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium

- CT

Computed Tomography

- DTI

Diffusion tensor imaging

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- GNAQ

Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha

- IDDRC

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center

- MAPK

Mitogen activated protein kinase

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PWB

Port-wine birthmark

- qEEG

Quantitative Electroencephalography

- RDCRN

Rare Disease Clinical Research Network

- SPECT

Single-photon emission computed tomography

- SWS

Sturge-Weber syndrome

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Authors’ contributions

S.S.G., K.E.J., and K.D.M. contributed equally to the drafting and revising of the manuscript. A.M.C. conceptualized, supervised, and revised the manuscript. All authors agree to the contents of the manuscript.

Funding

Our SWS-related biomarker research has been supported over the past 25 years by the National Institutes of Health Sponsors: Rare Disease Clinical Research Consortium (RDCRN) Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium (BVMC) SWS Investigator Group; and the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC) at Kennedy Krieger Institute.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

A.M.C. is an inventor on patents related to the R183Q GNAQ mutation in SWS and to the use of cannabidiol for the treatment of SWS; no funding has been received by her from these patents. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Siddharth S. Gupta, Katharine E. Joslyn and Kieran D. McKenney contributed equally to first author.

References

- 1.Comi AM. Sturge-Weber syndrome. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;132:157–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirley MD, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):1971–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeom S, Comi AM. Updates on Sturge-Weber syndrome. Stroke. 2022;53(12):3769–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dymerska M, et al. Size of facial Port-Wine birthmark May predict neurologic outcome in Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Pediatr. 2017;188:205–e2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valery CB, et al. Retrospective analysis of presymptomatic treatment in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Ann Child Neurol Soc. 2024;2(1):60–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joslyn KE, Truver NF, Comi AM. A review of Sturge-Weber syndrome brain involvement, cannabidiol treatment and molecular pathways. Molecules. 2024. 10.3390/molecules29225279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mankel FL, et al. Diagnostic pathway and management of first seizures in infants with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2025;67(1):111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ville D, et al. Prophylactic antiepileptic treatment in Sturge-Weber disease. Seizure. 2002;11(3):145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley TM, et al. Quantitative analysis of cerebral cortical atrophy and correlation with clinical severity in unilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2005;20(11):867–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marti-Bonmati L, Menor F, Mulas F. The sturge-weber syndrome: correlation between the clinical status and radiological CT and MRI findings. Childs Nerv Syst. 1993;9(2):107–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon C, et al. R183Q GNAQ Sturge–Weber syndrome leptomeningeal and cerebrovascular developmental mouse model. J Vascular Anomalies. 2024;5(4):e099. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zallmann M, et al. Retrospective review of screening for Sturge-Weber syndrome with brain magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography in infants with high-risk port-wine stains. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(5):575–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Califf RM. Biomarker definitions and their applications. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2018;243(3):213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bar C, et al. Early magnetic resonance imaging to detect presymptomatic leptomeningeal angioma in children with suspected Sturge-Weber syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(2):227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clifford SM, et al. Arterial spin-labeled (ASL) perfusion in children with Sturge-Weber syndrome: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Neuroradiology. 2023;65(12):1825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto ALR, et al. Quantitative apparent diffusion coefficient mapping may predict seizure onset in children with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2018;84:32–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vedmurthy P, et al. Study protocol: retrospectively mining multisite clinical data to presymptomatically predict seizure onset for individual patients with Sturge-Weber. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andica C, et al. Aberrant myelination in patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome analyzed using synthetic quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroradiology. 2019;61:1055–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juhász C, et al. Deep venous remodeling in unilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome: robust hemispheric differences and clinical correlates. Pediatr Neurol. 2023;139:49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosnyák E, et al. Predictors of cognitive functions in children with Sturge–Weber syndrome: a longitudinal study. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;61:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juhasz C, et al. Multimodality imaging of cortical and white matter abnormalities in Sturge-Weber syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(5):900–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comi AM. Presentation, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment of the neurological features of Sturge-Weber syndrome. Neurologist. 2011;17(4):179–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilli VK, et al. Clinical and metabolic correlates of cerebral calcifications in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(9):952–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin DD, et al. Dynamic MR perfusion and proton MR spectroscopic imaging in Sturge-Weber syndrome: correlation with neurological symptoms. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24(2):274–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JS, et al. Sturge-weber syndrome: correlation between clinical course and FDG PET findings. Neurology. 2001;57(2):189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aylett SE, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome: cerebral haemodynamics during seizure activity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41(7):480–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namer IJ, et al. Subtraction ictal SPECT co-registered to MRI (SISCOM) in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30(1):39–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valery CB, Comi AM. Sturge–Weber syndrome: updates in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Child Neurol Soc. 2023;1(3):186–201. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Paesschen W, et al. The use of SPECT and PET in routine clinical practice in epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20(2):194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sujansky E, Conradi S. Sturge-weber syndrome: age of onset of seizures and glaucoma and the prognosis for affected children. J Child Neurol. 1995;10(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen HJ, Kay MN. Associated facial hemangioma and intracranial lesion (Weber-Dimitri disease). Am J Dis Child. 1941;62(3):606–12. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lichtenstein BW. Sturge-Weber-Dimitri syndrome: cephalic form of neurocutaneous hemangiomatosis. M Archives Neurol Psychiatry. 1954;71(3):291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterman AF. Encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis (Sturge-Weber disease); clinical study of thirty-five cases. J Am Med Assoc. 1958;167(18):2169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chao DH. Congenital neurocutaneous syndromes of childhood. III. Sturge-Weber disease. J Pediatr. 1959;55:635–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brenner RP, Sharbrough FW. Electroencephalographic evaluation in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Neurology. 1976;26(7):629–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kossoff EH, et al. EEG evolution in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Epilepsy Res. 2014;108(4):816–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jansen FE, et al. Diazepam-enhanced beta activity in Sturge Weber syndrome: its diagnostic significance in comparison with MRI. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113(7):1025–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatfield LA, et al. Quantitative EEG asymmetry correlates with clinical severity in unilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome. Epilepsia. 2007;48(1):191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ewen JB, et al. Use of quantitative EEG in infants with port-wine birthmark to assess for Sturge-Weber brain involvement. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120(8):1433–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gill RE, et al. Quantitative EEG improves prediction of Sturge-Weber syndrome in infants with port-wine birthmark. Clin Neurophysiol. 2021;132(10):2440–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miao Y, et al. Clinical correlates of white matter blood flow perfusion changes in Sturge-Weber syndrome: a dynamic MR perfusion-weighted imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(7):1280–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bebin EM, Gomez MR. Prognosis in Sturge-Weber disease: comparison of unihemispheric and bihemispheric involvement. J Child Neurol. 1988;3(3):181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugano H, et al. Extent of leptomeningeal capillary malformation is associated with severity of epilepsy in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2021;117:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang S, et al. Characteristics, surgical outcomes, and influential factors of epilepsy in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Brain. 2022;145(10):3431–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Day AM, et al. Physical and family history variables associated with neurological and cognitive development in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2019;96:30–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bar C, Kaminska A, Nabbout R. Spikes might precede seizures and predict epilepsy in children with Sturge-Weber syndrome: a pilot study. Epilepsy Res. 2018;143:75–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sebold AJ, et al. Sirolimus treatment in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2021;115:29–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCann M, Cho A, Pardo CA, Phung T, Hammill A, Comi AM. Phosphorylated-S6 Expression in Sturge-Weber Syndrome Brain Tissue. Journal of Vascular Anomalies. 2022;3(3):e046.

- 49.Martins L, et al. Computational analysis for GNAQ mutations: new insights on the molecular etiology of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Mol Graph Model. 2017;76:429–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin R, et al. Activation of PKCalpha and PI3K kinases in hypertrophic and nodular Port wine stain lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(10):747–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan W, et al. Sustained activation of c-Jun N-terminal and extracellular signal-regulated kinases in port-wine stain blood vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(5):964–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wellman RJ, et al. Gαq and hyper-phosphorylated ERK expression in Sturge–Weber syndrome leptomeningeal blood vessel endothelial cells. Vascular Med. 2019;24(1):72–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S, et al. The mTOR/AP-1/VEGF signaling pathway regulates vascular endothelial cell growth. Oncotarget. 2016;7(33):53269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marler JJ, et al. Increased expression of urinary matrix metalloproteinases parallels the extent and activity of vascular anomalies. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sreenivasan AK, et al. Urine vascular biomarkers in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Vasc Med. 2013;18(3):122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimbrell B, et al. Longitudinal prospective study of Sturge–Weber syndrome urine angiogenic factors and neurological outcome. Annals Child Neurol Soc. 2024;2(2):120–34. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith ER, et al. Urinary biomarkers predict brain tumor presence and response to therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(8):2378–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kleber CJ, et al. Urinary matrix metalloproteinases-2/9 in healthy infants and haemangioma patients prior to and during propranolol therapy. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(6):941–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fjaer R, et al. A novel somatic mutation in GNB2 provides new insights to the pathogenesis of Sturge-Weber syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2021;30(21):1919–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galeffi F, et al. A novel somatic mutation in GNAQ in a capillary malformation provides insight into molecular pathogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2022;25(4):493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.