Abstract

Background

Metabolic syndrome is an emerging health problem, and its prevalence is rapidly increasing. Therefore, we first aimed to investigate its pathophysiology, focusing on the insulin resistance state and the consumption of high-calorie diets. In addition, previous studies have shown an association between metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, gonadal dysfunction and obstructive sleep apnea, but little is known about the nature of the relationship between metabolic syndrome and these conditions. Therefore, second, we aimed to investigate this relationship to better predict the risk of these diseases in MetS patients and vice versa.

Materials and methods

We conducted a comprehensive search in multiple scientific databases to examine the pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome and to investigate the nature of the relationship between metabolic syndrome and these conditions. The selection of the articles included in this review is based on their pertinence to the research issue, methodological rigor, and contribution to the field.

Results

This study revealed that insulin resistance and high fructose consumption are two important contributors to the pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome. Additionally, a bidirectional relationship was detected between metabolic syndrome and both non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and secondary male hypogonadism. Both non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and testosterone deficiency can lead to metabolic dysregulation and insulin resistance, which in turn exacerbate this clinical condition. A mutual relationship between metabolic syndrome and polycystic ovarian syndrome has been demonstrated, with similar risk factors and treatment strategies. Finally, an independent relationship was found between obstructive sleep apnea and the components of metabolic syndrome.

Conclusion

Metabolic syndrome is closely related to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, gonadal dysfunction and obstructive sleep apnea. It is therefore recommended that further studies be conducted to better understand these relationships to develop a comprehensive treatment strategy for metabolic health and these conditions.

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, Insulin resistance, High caloric diet, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Dyslipidemia, Male hypogonadism, Polycystic ovarian syndrome, Obstructive sleep apnea

Background

As early as 1923, a constellation of abnormalities, including hyperglycemia, hypertension and hyperuricemia, were detected in some patients. A Swedish physician, Kylin, described these abnormalities in a scientific article, but his study was not followed up [1]. Later, in 1988, the term “syndrome X” was introduced by Reaven [2] to describe this constellation of abnormalities representing glucose intolerance, atherogenic dyslipidemia and elevated blood pressure, focusing on insulin resistance (IR) as the core of this pathophysiological abnormality but without including obesity. In 1989, Kaplan [3] expanded this concept to include central obesity as a major abnormality and retitled it “The Deadly Quartet”. More recently, this group of metabolic disorders has become known as “metabolic syndrome” (MetS) [4].

MetS is linked to a variety of clinical conditions, including obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), atherogenic dyslipidemia, inflammation, oxidative stress, and reproductive disorders [5, 6]. MetS is also attributed to an increased risk of certain diseases, in which individuals with MetS have 5-fold and 2-fold greater risks of developing type 2 diabetes and heart disease, respectively, than those without MetS [7]. Moreover, MetS is widespread worldwide, and its incidence is expected to increase further in the coming years. Approximately 35% of adults in the U.S. and 50% of those over 60 years of age have been diagnosed with MetS [8]. Additionally, at least a quarter of adults in Europe and Latin America are affected by MetS [9]. MetS is also very costly in terms of life, productivity and expenditure. A study by Boudreau et al. [10] reported that the annual healthcare costs of patients with MetS are 1.6 times higher than those without MetS and that the presence of additional risk factors increases costs by 24%.

In light of the above, this review attempts to investigate the pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome, focusing on the insulin resistance state and the consumption of high-calorie diets, and explore the nature of the relationship between metabolic syndrome and its related conditions, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, gonadal dysfunction and obstructive sleep apnea.

Definition

Several definitions of MetS with different criteria and requirements have been proposed to help physicians identify patients with MetS (Table 1).

Table 1.

The definition of metabolic syndrome

| Risk factors | WHO (1998) [11, 12] | EGIR (1999) [163] | NCEP ATPIII (2001) [164] | IDF (2005) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Required criteria | IGT or IFG or IR + any two of others risk factors | Hyperinsulinemia + any two of others risk factors | Three or more of the following risk factors | Central obesity + any two of others risk factors |

| Hyperglycemia / insulin resistance |

IGT, IFG, T2DM and/or IR * |

Plasma insulin > 75th percentile. Reliable only in patients without T2DM. | Fasting glucose ≥ 110 mg/dl | Fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dl |

| Obesity | Waist to hip ratio: 0.95(M),0.85(F) or BMI˃30 kg/m2 | Waist circumferences: ≥94 cm(M), ≥ 80 cm(F) | Waist circumferences: 102 cm (M), ˃88 cm(F) | Increased waist circumferences (population specific) |

|

Dyslipidemia • High TG • Low HDL |

TG ≥ 150 mg/dl And/or HDL ≤ 35 mg/dl (M), ˂39 mg/dl (F) |

TG ≥ 177 mg/dl And/or HDL˂39 mg/dl |

TG ≥ 150 mg/dl HDL˂40 mg/dl(M), ˂50 mg/dl (F) |

TG ≥ 150 mg/dl or Rx HDL˂40 mg/dl (M), ˂50 mg/dl (F) or RX |

| Hypertension | ≥ 140/90 mm Hg | ≥ 140/90 mm Hg or on Rx | ≥ 130/85 mm Hg or on Rx | ≥ 130 mmHg systolic or ≥ 85 mmHg diastolic or on Rx |

| Micro- albuminuria | 20 µg/min or albumin: Cr ratio ˃ 30 mg/g. | --------- | --------- | --------- |

* Insulin sensitivity measured under hyperinsulinemic condition, glucose uptake below lowest quartile for background population investigation. WHO: World Health Organization; European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance; NCEP ATPII: National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel; IDF: International Diabetic Federation. IGT: Impaired glucose tolerance; IFG: Impaired fasting glucose; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; BMI: body mass index; TG: triglyceride; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; Rx, receiving treatment

The world health organization

The WHO proposal was a first attempt to develop a generally accepted definition of MetS [11]. They considered IR or any evidence of IR (glucose intolerance, impaired fasting glucose, T2DM) as the main diagnostic for MetS, together with two or more of these criteria: increased body mass index, dyslipidemia, hypertension and microalbuminuria. Hyperuricemia and coagulation disorders have been identified as components of MetS but are not decisive for its diagnosis [12]. Although the WHO definition includes a physiological and biological description of IR, it is clinically impractical because it relies on a euglycemic clamp to measure IR. Measuring microalbuminuria is also not easy in clinical practice.

The European group for study of insulin resistance

One year after the WHO definition, the European Group for Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR) [13] introduced a revised version of the definition for nondiabetics that excludes diabetic patients. The reason for this is that beta-cell dysfunction in diabetic patients leads to unreliable estimates of insulin sensitivity. Like the WHO, IR was the main diagnostic criterion. However, the EGIR differed from the WHO in the following respects:

They used the term “insulin resistance syndrome” instead of MetS.

They used the plasma insulin level and not the euglycemic clamp to assess IR.

They excluded patients with T2DM and microalbuminuria from the definition.

They focused more on abdominal obesity by measuring waist circumference (WC).

They suggested that hyperuricemia and coagulation disorders should not be included in the definition.

NCEP ATP III

The NCEP ATP III [14] reports that a subject is diagnosed with MetS if they exhibit more than two of these criteria: abdominal obesity, elevated blood glucose levels, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and/or decreased HDL. This definition is characterized by its ease, simplicity and applicability, as IR is not mandatory for the development of MetS. It also depends on the assessment of plasma glucose levels and avoids the use of the euglycemic clamp or the measurement of plasma insulin levels. Other important features of the NCEP ATP III definition are as follows:

WC was used to measure central obesity, with higher cutoffs to be consistent with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) definition [15].

TG and HDL are used as two separate components for the diagnosis of dyslipidemia.

The cutoff value for blood pressure was stricter and more stringent than that of the WHO.

The international diabetes federation

Because of the large differences in the diagnostic criteria for MetS and WC cutoff points, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) [16] has attempted to create a globally applicable definition that focuses on racial and gender diversity. As central obesity is closely linked to MetS, the IDF established central obesity as the cornerstone of its definition with specific ethnic WC cutoff values. In addition to central obesity, at least two or more of these criteria are needed: decreased HDL, elevated TG, elevated blood pressure, and/or increased fasting blood glucose. According to the IDF, individuals receiving treatment are considered positive for the corresponding risk factor. Although this definition allows for ethnic variations and is easily applicable in clinical practice, individuals who fit the criteria reported by the NCEP ATP III but do not have major WCs are excluded from this definition. Therefore, of the different proposed criteria for MetS, the NCEP ATP III criteria are the most applicable, followed by the IDF and WHO.

Harmonization of MetS definition

In 2009, a representative of several organizations, including the IDF, NIH, AHA and others, attempted to clarify the confusion in the MetS definition and presented a harmonized consensus definition called “Harmonization of the Metabolic Syndrome”. They agreed that a person who meets 3 of the 5 criteria proposed by the IDF is diagnosed with MetS, and none of these criteria are mandatory [17].

Methodology

This review used data from PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar with keywords such as “insulin resistance”, “high-fat diet” and “high-carbohydrate diet” to investigate the pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome. In addition, metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, gonadal dysfunction, and obstructive sleep apnea were used to examine the associations between metabolic syndrome and these conditions. First, the titles and abstracts of the articles were screened, and then the full texts were reviewed. Only peer-viewed articles with good methodology and relevance to the study were included in this review. This study is a rapid review that did not involve human participants; therefore, ethical approval was not included.

Findings

Pathogenesis

Insulin resistance

The pathophysiology of MetS encompasses various mechanisms that remain incompletely understood, but it is postulated that insulin resistance is the most important mechanism underlying most manifestations of MetS [18]. Insulin is a peptide hormone that is produced by the pancreas when blood sugar levels are high. It regulates glucose levels by promoting glycogen synthesis and glucose utilization in metabolically active tissues while inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis, thus preventing more glucose from entering the bloodstream [19]. Insulin also regulates lipid metabolism in two ways: in the liver, it stimulates de novo lipogenesis (DNL), and in adipose tissue, it prevents the lipolysis of triacylglycerol. Insulin also has an anabolic effect on protein metabolism by increasing protein synthesis and DNA replication [20]. It exerts its effect by binding to its receptor, triggering a series of events that include tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates (IRS), which stimulates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, thus mediating the metabolic role of insulin [21]. Any disruption of this pathway can lead to an IR state in which insulin-dependent cells, such as those in the liver and adipose tissue, do not respond properly to normal circulating insulin levels, so blood sugar levels remain high.

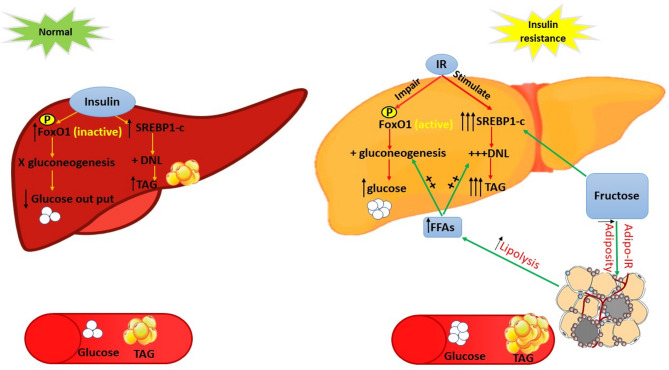

Under normal conditions, insulin inhibits the activity of Forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) in the liver through Akt/PKB-dependent phosphorylation, resulting in the inhibition of gluconeogenesis [22]. On the other hand, insulin stimulates the activity of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1-c (SREBP-1c), leading to upregulation of genes involved in the hepatic DNL process. In the insulin resistance state, the process of glucose homeostasis mediated by FoxO1 is impaired, whereas DNL is overstimulated, leading to increased hepatic glucose and TG production [23]. An important factor that triggers and/or exacerbates hepatic IR is significantly increased circulating free fatty acids (FFAs), which are produced from enlarged adipose tissue [24] Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The role of insulin resistance and high fructose consumption in the development of metabolic syndrome. In the physiological state, insulin promotes both FoxO1 phosphorylation and SREBP1-c expression, resulting in the inhibition of gluconeogenesis and the promotion of de-novo lipogenesis, respectively. The net result is decreased hepatic glucose output and increased triglyceride production. In insulin resistance, AKT/PKB-dependent phosphorylation of Foxo-1 is blocked, whereas SREBP1-c expression is overstimulated, leading to excessive hepatic production of glucose and triglycerides. Excessive fructose consumption induces SREBP1-c expression and visceral adipose tissue insulin resistance, leading to increased DNL and adipose tissue lipolysis, respectively. The increased lipolysis is associated with the excessive release of free fatty acids from visceral adipose tissue into the bloodstream and then into the liver, which promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis and triglyceride production. FoxO1: forkhead box O1; SREBP1-c: sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1-c; AKT/PKB; protein kinase B; DNL: de novo lipogenesis; TAG: triacylglycerol; FFAs: free fatty acids; IR; insulin resistance; Adipo-IR; adipose tissue resistance

There are many proposed mechanisms by which FFAs may induce hepatic IR, such as increased substrate availability, which fuels the liver to produce lipids [25]. Another important mechanism is the direct inhibitory effect of FFAs on the effects of insulin on glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis or both. However, the main effect is related to the inhibition of insulin-mediated suppression of glycogenolysis [26] Hepatic insulin resistance mediated by FFAs was shown in obese individuals with and without diabetes, where reducing FFAs levels in the blood for 12 h with acipimox improved insulin sensitivity [27]. This effect was also observed in studies in mice. In perilipin-null mice, increased lipolysis of adipose tissue led to accelerated release of FFAs from fat cells into the bloodstream, which is responsible for an increase in systemic FFAs and thus in IR [28].

Dietary factors

Dietary intervention is an important factor in the pathogenesis of MetS [29].

Dietary fats

The amount and type of ingested fat are two main factors that influence MetS and its components (Table 2). Based on the amount of ingested fat, diets can be divided into three categories: low-fat diet (LFD), in which fats account for 10% of energy; high-fat diet (HFD), in which fats account for 30–50% of energy; and very high-fat diet (VHFD), in which fat intake exceeds 50% of energy [30]. There are various types of fatty acids with various metabolic reactions. Based on their saturation degree, fatty acids can either be saturated, with no double bonds (e.g., myristic and palmitic acid), monounsaturated, with one double bond (e.g., vaccenic acid), or polyunsaturated, with at least two double bonds (e.g., arachidonic acid and linolenic acid) [31, 32]. Polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA)-enriched diets, especially those enriched with fish oils, can protect against metabolic diseases, whereas those enriched with saturated fatty acids (SFAs), especially long-chain SFAs, are closely associated with MetS and its pathologies [33–35]. SFAs are a heterogeneous class of FAs that may vary in their mechanism of action depending on their structure and length. For example, short-chain SFAs (SC-SFAs) and medium-chain SFAs (MC-SFAs) have positive effects on energy metabolism and protect against obesity, while long-chain SFAs (LC-SFAs) are directly related to metabolic disorders [36, 37]. Of the SC-SFAs, butyrate, a fatty acid produced during fermentation in the large intestine, has many metabolic benefits in HFD-fed mice, including a reduction in HFD-induced obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and hepatic steatosis [38]. In addition, butyrate has been shown to reduce insulin resistance, hyperglycemia [39, 40], atherosclerosis [41] and blood lipid levels while increasing energy expenditure and fatty acid oxidation [42]. Of the MC-SFAs, caprylic acid has been shown to positively modulate lipid metabolism and improve lipid profiles, including lowering triacylglycerol and total cholesterol blood levels [43]. In contrast, LC-SFAs, especially palmitic acid, are known to promote MetS and its associated disorders, such as systemic IR, T2DM and obesity [36, 44]. Palmitic acid can directly impair insulin signaling in cultured rat muscle and liver cells as well as decrease the viability of pancreatic cells and their ability to produce insulin [45]. In addition, excessive accumulation of palmitic acid leads to dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress and vascular damage [46, 47].

Table 2.

Effect of high fat diet on development of metabolic syndrome and its component in mice

| No | Animal | Diet | Duration | Effect | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Male C57BL/6J mice | HFD 37% | 6 weeks |

• Weight gain. • Glucose metabolic disturbance. • Dyslipidemia. • Inflammation. |

[165] |

| 2. | Male C57BL/6J mice | HFD 37.1% | 20 weeks |

• Obesity. • Insulin resistance. • Dyslipidemia. • Fatty liver and liver dysfunction. |

[166] |

| 3. | Male C57BL/6J mice | HFD 45% | 12 weeks |

• Increased body weight. • Hepatic steatosis. • Impaired intestinal barrier integrity. |

[167] |

| 4. | Male C57BL/6J mice | HFD 45% | 16 weeks |

• Glucose metabolic disturbance. • Insulin resistance. • Dyslipidemia. • Imbalance in gut microbiota. |

[168] |

| 5. | Male C57BL/6J mice | HFD 60% | 8 weeks |

• Weight gain. • Glucose intolerance. • Elevated serum lipid level. • Oxidative stress. • Imbalance in gut microbiota. |

[169] |

| 6. | Male C57BL/6J mice | HFD 60% | 8 weeks |

• Weight gain • Dyslipidemia. • Hepatic steatosis. • Gut dysbiosis |

[170] |

| 7. | Male C57BL/6 mice | HFD 60% | 16 weeks |

• Increased mass gain. • Impaired in glucose clearness. • Insulin resistance. • fatty liver |

[171] |

Dietary carbohydrates

The consumption of carbohydrate-enriched food, especially those with a high glycemic index that are rapidly absorbed, has been shown to trigger hyperglycemia, IR, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which are the major contributors to MetS [48]. As with dietary fats, carbohydrates are not chemically equivalent. They can be divided into two main categories. The first category is simple carbohydrates, which can be subdivided into monosaccharides and disaccharides. Glucose and fructose are examples of monosaccharides, while sucrose and lactose are examples of disaccharides. The second category is complex carbohydrates, which consist of starch and fiber [49]. The basic nutritional models used in most experimental studies with high-carbohydrate diets are sucrose, fructose and glucose. However, increased fructose intake is considered a major factor contributing to the onset of obesity and MetS (Table 3) [50].

Table 3.

Effect of high fructose diet on development of metabolic syndrome and its component in rat

| No | Animal | Diet | Duration | Effect | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Male Wister rat | Fructose in drinking water 20% | 8 weeks |

• Obesity • Hyperglycemia. • hypertension. |

[172] |

| 2. | Male Wister rat | High fructose diet 60% | 6 weeks |

• Insulin resistance. • Dyslipidemia. • Hyperuricemia. • Disruption of adipokine. • Oxidative stress. • Hypertension. |

[173] |

| 3. | Male Wister rat | High fructose diet 60% | 42 days |

• Hyperglycemia. • Dyslipidemia. • Hepatic oxidative stress. • Hypertension. |

[174] |

| 4. | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | High fructose diet 60% | 8 weeks |

• Hyperinsulinemia. • Dyslipidemia. • Hyperuricemia. • Hypertension |

[175] |

| 5. | Male Sprague–Dawley rats | High fructose diet 60% | 8 weeks |

• Hyperglycemia. • Hyper triglyceridemic. • Renal impairment. • Hypertension. |

[176] |

| 6. | Male Sprague–Dawley rats | High fructose diet 60% or fructose in the drinking water 10% | 8 weeks |

• Hyper hypertriglyceridemia • Hyperuricemia. • Hypertension. • Renal impairment. |

[177] |

| 7. | Male Albino rat | Highfructose diet 65% | 6 weeks |

• Insulin resistance • Dyslipidemia. • Hyperuricemia. • Disruption of adipokine. • Oxidative stress. • Hypertension. |

[178] |

Previous studies have shown that increased consumption of fructose, particularly from sugary beverages, causes atherogenic dyslipidemia, visceral adiposity, and IR, increasing the risk of developing T2DM and CVD [51]. This can be attributed to many factors. First, the metabolism of fructose differs from that of glucose. The main difference is that fructose is readily metabolized in an insulin-independent way. Second, fructose bypasses the action of the phosphofructokinase enzyme, the main enzyme that regulates glycolysis, and is inhibited by increased ATP levels. Instead, fructose is phosphorylated by fructokinase, producing fructose-1-phosphate, and this enzyme is not inhibited by either an increase in its product or an increase in the intracellular energy level. Therefore, even with excess ATP in the liver, fructose-1-phosphate is produced [52, 53]. Third, fructose is more lipogenic than glucose because it can upregulate the expression of SREBP-1c independently of insulin (Fig. 1) [23, 54]. This finding was confirmed by Mukai et al. who reported that hepatic SREBP-1c expression was increased in both female Wistar rats and their fetuses with high fructose consumption during pregnancy [55]. Finally, excess fructose impairs adipose tissue function by increasing adiposity and causing insulin resistance in adipose tissue (adipo-IR). It impairs the insulin down signaling pathway in adipose tissue, leading to increased lipolysis, followed by the uncontrolled release of FFAs that travel directly to other organs and cause metabolic disturbances. In the liver, FFAs lead to steatosis and promote gluconeogenesis and TG production (Fig. 1) [56, 57]. This has already been established in studies on rodents fed fructose-rich diets [58, 59].

High carbohydrate high fat diet

Changing dietary habits, especially increased consumption of high-carbohydrate high fat (HCHF) diets rich in SFAs and refined sugars, are major contributors to the increased prevalence of MetS, obesity and T2DM [60]. In animal studies, chronic ingestion of HCHF diets lead to rapid damage to cardiac tissue, allowing detailed investigations of changes in cardiovascular function and structure (50). Feeding male rats, a HFHC diet for 16 weeks led to cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, increased cardiac stiffness and inflammatory cell infiltration [61–63]. In addition to causing cardiac damage, the HCHF diet causes other abnormalities, such as hepatic steatosis, dyslipidemia, IR and impaired glucose tolerance [64, 65]. Other factors contributing to the development of MetS are ethnicity, smoking, heavy alcohol intake, physical inactivity, maternal undernutrition and chronic stress [66, 67].

MetS-associated conditions

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

NAFLD is a hepatic manifestation of MetS that is closely associated with its components [68]. It is characterized by triglyceride deposition in more than 5% of hepatocytes without secondary causes of liver injury or significant alcohol consumption [69]. NAFLD can range from a mild form of non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to a severe form of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). In NAFL, hepatic steatosis is present, with IR being the main pathogenic factor for its development [70], whereas in NASH, hepatic steatosis is combined with inflammation and fibrosis, which can progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [71].

Studies have shown that the spleen-liver axis plays an important role in the progression of obesity- associated NAFLD in a cell-specific manner [72, 73]. A study by Brummer et al. [74] suggests that the accumulation of splenic myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) and natural killer T (NKT) cells in the spleen, which are innate-like leukocytes, may modulate MDSC and NKT cells in fatty livers of obese mice, leading to fatty liver inflammation. This indicates a strong positive correlation between the distribution of MDSC and NKT cells in the spleen and liver. However, this correction is not observed in other myeloid cell populations or the B and T cell compartments. The link between spleen-liver axis and obesity-related NAFLD has been also demonstrated in HFD-fed mice, in which alterations in cytokine production by splenic lymphocytes contributed to the development of NAFLD [75]. This suggests that the measurement of spleen volume should be further utilized to better diagnose the presence of NAFLD.

Since NAFLD is highly related to metabolic syndrome, the term “metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease” (MAFLD) with specific criteria was used to better identify individuals with metabolic liver disease [70, 76]. An individual is diagnosed with MAFLD if hepatic steatosis is detected by biomarkers in blood, biopsy or imaging. In addition to hepatic steatosis, one of the following clinical disorders should present overweight/obesity, T2DM or a metabolic disorder, where a metabolic disorder means the presence of more than one metabolic dysfunction [76]. An intriguing aspect of this definition is that it does not exclude those with other causes of chronic liver disease [76, 77]. However, a significant proportion of patients with NAFLD who are lean with normal BMI were not included [78]. In addition, the continued use of the term “fatty” is perceived by many as stigmatizing [79]. Therefore, recently, in 2023, the term “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease” (MASLD) was introduced by three multinational liver associations. It was agreed that patients with steatosis who meet one of the five simple components of MetS (impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, overweight or obesity, hypertension or dyslipidemia) are considered to have MASLD [80]. These diagnostic criteria are less restrictive than those of MAFLD, as they allow the use of a single risk factor that can be easily obtained from accessible data instead of two. As a result, both lean and non-lean patients with NAFLD were better defined. However, changing the definition from NAFLD to MASLD is still under investigation.

Earlier studies assumed that there is a bidirectional interaction between MAFLD and components of MetS [81]. In the context of MAFLD, the liver is thought to function as an active paracrine and endocrine organ, producing several bioactive mediators that cause inflammation, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and IR [82]. It has been shown that the spleen-liver axis contributes to these changes. In LPS-exposed rats, LPS induced splenic macrophages to release leukotriene B4 (LTB4), an important messenger of the spleen-liver axis. LTB4 induces hepatic Kupffer cells to release tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in response to LPS in a receptor-dependent manner, leading to systemic inflammation [83]. These metabolic disturbances in turn aggravate MAFLD, creating a vicious cycle. Therefore, in addition to liver-related complications, patients with MAFLD may also suffer from other disorders that increase mortality [84]. In fact, MAFLD is one of the main risk factors for CVD, as it leads to increased fat deposition in the epicardium. Additionally, inflammatory mediators released in MASLD induce myocarditis and endothelial damage and accelerate atherogenesis, leading to coronary artery disease [81]. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 2, there is a strong association between MAFLD and both abnormal lipoprotein metabolism and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [85, 86].

Fig. 2.

MAFLD and increasing risk for chronic kidney disease and vascular injury. Excess free fatty acids are transported and esterified in the liver, producing TAG-rich VLDL particles. The increased secretion of VLDL stimulates the CEPT enzyme to transfer TAG from the VLDL particles to both HDL and LDL. This exchange makes TAG-rich HDL susceptible to being easily excreted by the kidneys, increasing the incidence of CDK. Meanwhile, TAG-rich LDL is hydrolyzed by hepatic lipase, producing oxidized LDL particles, which in turn increase the incidence of vascular injury. FFAs, free fatty acids; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; CEPT, cholesterol ester transfer protein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CDK, chronic kidney disease; LDL, low density lipoprotein; ox -LDL, oxidized low density-lipoprotein

Atherogenic dyslipidemia

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, atherogenic dyslipidemia is a key component of MetS that is closely related to IR. It includes a constellation of lipoprotein abnormalities, such as elevated concentrations of TG and oxidized LDL with decreased HDL particles. All of these factors lead to CVD [87]. The mechanism involved in increased TG levels is related primarily to increased circulation and portal FFAs [88]. This hypertriglyceridemia promotes the liver to produce high amounts of TG-rich very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) into the bloodstream [89]. The persistent presence of VLDL in circulation stimulates the cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) enzyme, which transfers TG from these particles to HDL and LDL particles. This transfer makes HDL particles less dense and smaller so that HDL particles can be excreted more easily via the kidneys, which explains the short half-life of HDL in the blood stream [90]. On the other hand, hepatic lipase hydrolyzes triglyceride-rich LDL into small dense LDL particles and ox-LDL particles that are capable of penetrating the vascular endothelium and causing endovascular injury (Fig. 2) [91].

Gonadal dysfunction

Gonadal dysfunction, including polycystic ovary syndrome and male hypogonadism, is closely associated with MetS [92].

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a hormonal imbalance that affects women after puberty. The 2003 Rotterdam Consensus [93] states that a woman with more than one of the following diagnostic criteria is diagnosed with PCOS. These criteria are excess androgen levels (clinical and/or biochemical), polycystic ovarian morphology and ovarian dysfunction; leading to subfertility or infertility. The increased androgen production in PCOS is attributed to dysregulation of gonadotropin secretion (increased pulsatility of luteinizing hormone (LH) and a disturbed LH-FSH ratio), which stimulates theca cells of the ovaries to produce a considerable amount of androstenedione [94]. In addition, adiposity is strongly associated with the development and maintenance of hyperandrogenism. This may be due to the overactivation of 17b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17beta-HSD) and 5α-reductase enzymes, which are important for steroid metabolism and the production of androgens by adipose tissue [95].

Studies have indicated a mutual relationship between MetS and PCOS. PCOS women are more susceptible to exhibit metabolic disturbances (approximately 1/3 to 1/2 of all adolescent girls and women with PCOS have MetS), and women with MetS often also have the reproductive/endocrine characteristics of PCOS [95, 96]. This phenomenon was reported in previous studies on female rats fed a high-calorie diet, which not only presented metabolic changes but also presented signs of PCOS, such as irregular estrus cycles, high LH levels and abnormal ovarian morphology [97]. MetS and PCOS have several common criteria, such as atherogenic dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia. In addition, IR aggravates PCOS and promotes hyperandrogenism, which is the main factor for symptoms and signs of PCOS [98]. In hyperinsulinism, insulin acts as a true gonadotropic hormone that directly enhances LH-stimulated androgen secretion from oocytes. Therefore, androgen levels are positively correlated with high insulin levels [99]. In addition, hyperinsulinemia associated with IR reduces the hepatic release of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which promotes hyperandrogenism [98]. On the other hand, previous research has shown that increased androgen levels in adult female rats induce hyperinsulinemia and IR through the ability of androgen to increase insulin gene (Ins) transcription [100]. Furthermore, hyperandrogenism is thought to be a predictor of NAFLD in PCOS patients [101]. A study conducted by Rathi et al. [102] showed that free androgen index (FAI), an indicator of hyperandrogenism, was significantly higher in PCOS patients with NAFLD than in PCOS patients without NAFLD. The elevated androgen level in PCOS patients interferes with insulin signaling and promotes de novo lipogenesis, which favors the development of NAFLD. Another important similarity between MetS and PCOS is the importance of genetic predispositions in their pathogenesis [103, 104]. Ultimately, the same treatment strategies are used for MetS and PCOS, such as insulin-sensitizing agents, dietary changes and regular exercise [95].

Male hypogonadism

Male hypogonadism (HG) is a medical condition resulting from the inability of the testes to produce sufficient amounts of testosterone (T) and/or impaired spermatogenesis [105]. HG can be either primary or secondary. In primary hypogonadism, the testicles are impaired, but the gonadotropin concentration is increased (hypergonadotropic hypogonadism) [106]. In secondary hypogonadism, both the serum T and gonadotropin concentrations are low, and spermatogenesis is impaired (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) [107]. MetS is associated with secondary HG, termed male obesity secondary hypogonadism (MOSH), which is characterized by impaired sexual function and fertility, altered body composition and lipid metabolism [108].

Prospective studies indicate a bidirectional relationship between MOSH and MetS, as MetS increases the occurrence of HG (as the number of MetS components increases, the T level decreases). However, as T levels decrease, the risk of developing MetS increases [109].

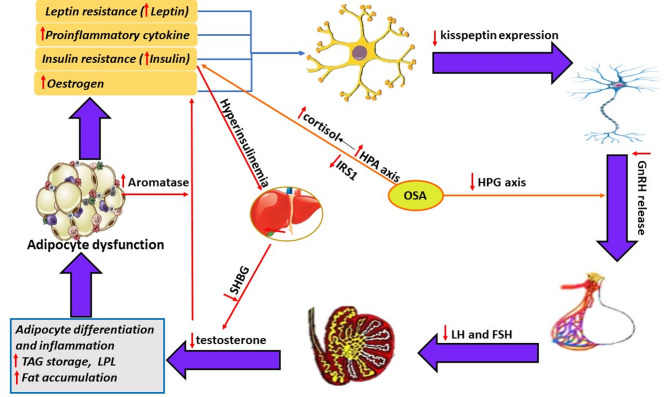

MetS and low testosterone levels

MetS induces hypogonadism in men. Adipocytokines such as TNFα and IL-1 produced by expanded visceral fat lead to inflammation in the hypothalamus and to a distribution of the neuronal network that controls the release of GnRH. This distribution involves a change in the expression of kisspeptin and its receptor, a neuropeptide that enhances the release of GnRH into the circulation [110]. Animal experimental data have shown that the expression of kisspeptin was reduced in the hypothalamus of mice subjected to leptin deprivation and HFD-induced obesity [111]. Another important factor for MetS-associated hypogonadism is related to decreased hepatic SHBG and increased aromatase activity in fat cells. As mentioned above, hyperinsulinemia suppresses hepatic production of SHBG, resulting in an increase in the free T concentration, a good substrate for aromatase produced by expanded adipose tissue to convert T to estradiol (testosterone-estradiol shunt) [112]. The increased estradiol level suppresses the function of the hypothalamic‒pituitary gland, resulting in a further decrease in the plasma T concentration [113, 114]. This finding was reported by Polari et al. [115], who reported that the expression of the aromatase gene was increased in men with increasing obesity-related body weight and inflammation, which contributed to the development of an imbalance between estrogen and androgen. This affects lipid metabolism by altering the presence of the LPL enzyme on fat cells and increasing the storage of TG. The latter leads to increased deposition of visceral and total body fat. These changes create a vicious cycle between MetS and HG (Fig. 3) [108].

Fig. 3.

Viscous cycle of metabolic syndrome, secondary male hypogonadism and obstructive sleep apnea. Besides IR and leptin resistance associated with MetS, the expanded visceral adipose tissue produces inflammatory products. All these factors reduce the expression of kisspeptin and thus the release of GnRH and testosterone. In addition, increased the activity of aromatase enzyme produced from adipose tissue and decreased hepatic production of SHBG contribute to the decrease in testosterone levels. This decrease in testosterone concentration exacerbates the metabolic changes by increasing adipocyte inflammation and fat accumulation. OSA increases the HPA axis and cortisol levels, leading to hyperinsulinemia and IR. On the other hand, it lowers HPG levels, leading to reduced GnRH release and subsequent secondary hypogonadism. GnRH: Gonadotropin releasing hormone; LH: Luteinizing hormone; FSH: follicle stimulation hormone; LPL: lipoprotein lipase enzyme; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea. HPA: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; HPG: hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

Testosterone deficiency and risk for MetS

Hypogonadism is thought to be a fundamental component of MetS [116]. The primary effect of HG on the maintenance and exacerbation of MetS is due to the fact that testosterone deficiency (TD) impairs visceral adipose tissue function, as TD appears to promote adipocyte differentiation and inflammation as well as fat accumulation, leading to chronic inflammation, IR, glucose intolerance and dyslipidemia [117, 118]. These factors increase the risk of developing MetS. Furthermore, the resulting dysfunction of visceral adipose tissue increases estrogen, leptin, insulin, and inflammatory cytokines, resulting in impairment of the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒testicular (HPT) axis, which exacerbates the hypogonadal state (Fig. 3) [119]. Baik et al. [120] reported that TD increases adiposity and the expression of FA synthesis genes in the abdominal fat of rats fed a normal diet. TD is also closely linked to MetS-associated dyslipidemia. Epidemiologic data have shown an inverse relationship between T and TG, TC and LDL, while a positive relationship exists between T levels and HDL [121]. However, many studies have shown that T therapy can not only treat HG but also delay or inhibit the progression of MetS to overt diabetes or CVD through beneficial effects on visceral adipose tissue function, blood pressure, insulin regulation and lipid metabolism [116, 122].

Obstructive sleep apnea

Obesity increases the risk of OSA

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a cardiometabolic disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness, intermittent hypoxia (IH) and fragmentation of sleep, which results from recurrent airway obstruction during sleep [123]. Obesity, especially central adiposity, is a potent risk factor for OSA [124]. The incidence of OSA is greater in obese patients than in nonobese patients [125]. The mechanism linking obesity and OSA is poorly understood but may be due to obesity causing upper airway changes that favor OSA. Obesity may increase the collapsibility of the pharynx due to increased lipid deposition in the lateral pharyngeal wall and reduce its diameter [126]. In addition, abdominal fat deposits lead to a decrease in lung volume and function [127]. Obesity may also affect neuromuscular control of the upper airways through interactions of adipokines and adipocyte-binding proteins at their receptors [128].

OSA induces metabolic dysregulation

Epidemiologic data have established an independent relationship between OSA and MetS components, including NAFLD, IR, glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension [129, 130]. First, OSA and NAFLD. OSA is independently linked to two hit hypotheses of NAFLD. IH is implicated in increased lipid deposition in the liver, as it can increase hepatic FFA influx and SREBP1c expression in obese mice [131]. IH associated with OSA induces hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress by upregulating the proinflammatory transcription factors NF-κB and NADPH oxidase, respectively [132, 133]. Studies in animals and cell cultures have shown that IH stimulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8, which is a key feature of OSA patients [134]. This was also confirmed in a study conducted in HFD-fed mice. IH transformed hepatic steatosis into hepatitis and then into fibrosis [133]. Second, OSA and IR. Sleep deprivation (SD) in OSA patients appears to decrease insulin sensitivity by increasing the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and decreasing adiponectin levels [135]. Moreover, IH may contribute to the development of IR by inhibiting insulin signaling [136] and inducing an inflammatory state in adipose tissue [137]. Both SD and IH create stress in a person’s body, leading to hyperactivity of the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal axis, which increases cortisone release. The latter leads to glucose intolerance and IR [138]. In contrast, patients with OSA show a decrease in the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒gonadal axis, resulting in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (Fig. 3) [139]. This was confirmed by Lee et al. [140]. The effects of OSA, IH and SD on metabolic aspects were effectively studied. Lean mice exposed to IH exhibited glucose intolerance and IR. After a few weeks of IH, these metabolic disturbances disappeared. On the other hand, obese mice exposed to IH exhibited persistent glucose intolerance and IR even after chronic exposure to IH [141]. OSA not only causes disturbed glucose metabolism but also disturbed lipid metabolism. OSA patients showed higher levels of HDL dysfunction and increased oxidized LDL levels [142]. Data from murine studies attributed this effect to IH-induced excessive lipolysis of adipose tissue and dysregulation of lipoprotein lipase [141]. Finally, OSA and PCOS. a negative association between OSA and IVF outcomes was found in PCOS patients, particularly in relation to clinical pregnancy and live birth rate [143]. In PCOS&OSA patients, OSA exacerbated IR and hyperlipidemia and decreased levels of anti-Mullerian hormone, an indicator of ovarian function, compared to PCOS patients without OSA, leading to reproductive dysfunction [144]. On the basis of the information mentioned above, some experts have suggested that OSA should be considered a component of metabolic syndrome [145].

Management

Changes in lifestyle

Diet

Lifestyle modifications, including changes in dietary habits and increases in physical activity and exercise, constitute the basis for managing MetS [146]. Many studies have linked a plant-based diet with a lower incidence of MetS and its components [147]. The Mediterranean diet (MD) is a well-known plant-based diet characterized by a balanced combination of fruits, vegetables, fish, grains, and MUFAs such as olive oil and PUFAs, with reduced meat and dairy intake [148]. The protective effect of MD in metabolic syndrome can be attributed to the phytochemical components it contains, such as polyphenols, tocopherols and flavonoids, which are very strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents [149]. Previous data have shown the beneficial metabolic effects of olive leaf extract, an important component of MD, in rat models of metabolic syndrome, including improvements in liver function and glucose utilization [150, 151]. Additionally, several previous studies have confirmed the protective effect of resveratrol, a polyphenolic component, in obesogenic diet-fed rats [152, 153]. Low-carbohydrate diets, especially ketogenic diets, also help in the management of obesity, MetS and CVD [154]. Carbohydrate restriction (CR) in the ketogenic diet reduces insulin secretion, which inhibits lipid synthesis and accumulation while increasing lipolysis. This finding was confirmed in a previous study in mice with MetS [155]. In addition, CR stimulates the use of ketone bodies as a primary energy source [147], and the high protein content in a ketogenic diet has a satiety effect that reduces appetite [154].

Physical activity

Many studies have shown that an increase in physical activity (PA) and cardiorespiratory fitness, an increase in the ability of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems to supply skeletal muscles with oxygen, has a positive effect on MetS and its components [156]. According to the type and intensity of PA, PA can also help with weight loss, as it reduces fat mass, increases total energy expenditure and maintains lean body mass [146].

Edible microalgae

Recent studies suggest that edible microalgae have beneficial properties for preventing many acute and chronic diseases because of their nutrient-rich and bioactive components, such as polysaccharides, carotenoids, n-3PUFAs and phenolic components [157, 158]. These components can act effectively against MetS under two conditions: during the development of IR and when the function of pancreatic cells is impaired. This is attributed to the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of the carotenoids and n-3PUFAs they contain , which prevent systemic inflammation and pancreatic damage [158].

Inflammatory inhibitors

Since inflammation is considered a potent MetS component, the effects of the inhibition of phospholipase A2 group IIA (PLA2G2A), an enzyme involved in the formation of prostaglandin E2 and eicosanoids, on diet-induced obesity were tested in a rat model. Inhibition of PLA2G2A was found to suppress inflammatory cell infiltration and attenuate visceral adiposity, metabolic changes, cardiovascular and liver changes [159].

Bariatric surgery

For severely obese patients, bariatric surgery is the first-line treatment strategy, especially when nonsurgical alternatives have failed. Gastric bypass reduces hunger and energy intake, changes food preferences, and increases satiety and energy expenditure [160, 161]. However, these changes could lead to micronutrient deficiencies and alterations in gut hormones, the microbiota, the gut‒brain axis and bile acid signaling [160, 162].

Conclusion

Metabolic syndrome is a common clinical condition consisting of a number of interrelated diseases, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, dyslipidemia and reproductive disorders. Several definitions with different criteria have been developed to facilitate the identification of patients with MetS. The pathophysiology of MetS is multifactorial, with the interplay of genetic, nutritional, and environmental factors, but insulin resistance, and dietary factors play a major role in the progression of the syndrome. As MetS is associated with a variety of risk factors, patients with MetS have a higher risk of diabetes, heart disease and cancer. It is important to understand the nature of relationship between MetS and its associated disorders for better management of MetS patients. In this study, a bidirectional relationship was found between MetS and NAFLD and between MetS and male hypogonadism. A mutual relationship was demonstrated between MetS and PCOS. Finally, an independent relationship was found between OSA and the components of metabolic syndrome. However, this study has some limitations, such as the lack of clarification of the role of genetic variations and gut dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of MetS. Moreover, the nature of the relationship between MetS and other associated conditions such as non-alcoholic fatty pancreatic disease, MetS-related renal impairment and cognitive impairment was not included in the study. In addition, clinical and epidemiologic studies should be conducted to verify the nature of the relationship between MetS and its associated disorders.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Adipo-IR

Adipose tissue resistance

- AHA

American Heart Association

- CETP

Cholesterol ester transfer protein

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CR

Carbohydrate restriction

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DNL

De novo lipogenesis

- EGIR

European Group for Study of Insulin Resistance

- FAI

Free androgen index

- FFAs

Free fatty acids

- FSH

Follicle stimulation hormone

- FoxO1

Forkhead box O1

- GnRH

Gonadotropin releasing hormone

- HCD

High carbohydrate diet

- HCHF

High-carbohydrate high fat

- HFD

High-fat diet

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- HG

Hypogonadism

- HPA

Hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal axis

- HPG

Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

- HPT

Hypothalamic‒pituitary‒testicular

- IDF

International Diabetes Federation

- IH

Intermittent hypoxia

- IR

Insulin resistance

- IRS

Insulin receptor substrates

- LC-SFAs

Long-chain saturated fatty acids

- LFD

Low-fat diet

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- LH

Luteinizing hormone

- LTB4

Leukotriene B4

- LPL

Lipoprotein lipase enzyme

- MC-SFAs

Medium-chain saturated fatty acids

- MD

Mediterranean diet

- MAFLD

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

- MASLD

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- MOSH

Male obesity secondary hypogonadism

- NAFL

Non-alcoholic fatty liver

- NASH

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NCEP ATP III

National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NKT

Natural killer T

- PA

Physical activity

- PCOS

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PLA2G2A

Phospholipase A2 group IIA

- PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- OSA

Obstructive sleep apnea

- OX-LDL

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein

- SD

Sleep deprivation

- SC-SFAs

Short-chain saturated fatty acids

- SFAs

Saturated fatty acids

- SHBG

Sex hormone-binding globulin

- SREBP-1c

Sterol regulatory element binding protein-c

- T

Testosterone

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TD

Testosterone deficiency

- TG

Triglyceride

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- VHFD

Very high-fat diet

- VLDL

Very low-density lipoprotein

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WC

Waist circumference

Author contributions

D.R. is responsible for conceptualization, writing the draft, illustration of the figure and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study does not involve human participants or animal use; therefore, ethical approval was not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kylin E. Studies of the hypertension-hyperglycemia-hyperuricemia syndrome. Zentralbl Inn Med. 1923;44:105–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reaven GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37(12):1595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan NM. The deadly quartet: Upper-Body obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(7):1514–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberti G. Introduction to the metabolic syndrome. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2005;7(supplD):D3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reaven P. Metabolic syndrome. J Insur Med. 2004;36(2):132–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss R, Bremer AA, Lustig RH. What is metabolic syndrome, and why are children getting it? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1281(1):123–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bovolini A, Garcia J, Andrade MA, Duarte JA. Metabolic syndrome pathophysiology and predisposing factors. Int J Sports Med. 2020;42(03):199–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCracken E, Monaghan M, Sreenivasan S. Pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(1):14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho LW. Metabolic syndrome. Singap Med J. 2011;52(11):779–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudreau D, Malone D, Raebel M, Fishman P, Nichols G, Feldstein A, et al. Health care utilization and costs by metabolic syndrome risk factors. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7(4):305–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Organization WH. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: report of a WHO consultation. Part 1, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. World health organization; 1999.

- 12.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15(7):539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balkau B, Charles MA. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European group for the study of insulin resistance (EGIR). Diabet Med. 1999;16(5):442–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult treatment panel III). JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson PM, Tuomilehto J, Rydén L. The metabolic syndrome–What is it and how should it be managed? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(2suppl):33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Group IETFC. International diabetes federation: the IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/Metabolic_syndrome_def.pdf. 2005.

- 17.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; National heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo S. Insulin signaling, resistance, and the metabolic syndrome: insights from mouse models into disease mechanisms. J Endocrinol. 2014;220(2):T1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahed G, Aoun L, Bou Zerdan M, Allam S, Bou Zerdan M, Bouferraa Y, et al. Metabolic syndrome: updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meshkani R, Adeli K. Hepatic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Clin Biochem. 2009;42(13):1331–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Models Mech. 2009;2(5–6):231–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry RJ, Samuel VT, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. The role of hepatic lipids in hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2014;510(7503):84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. Fructose consumption: potential mechanisms for its effects to increase visceral adiposity and induce dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19(1):16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boden G. Obesity, insulin resistance and free fatty acids. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18(2):139–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365(9468):1415–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boden G, Cheung P, Stein TP, Kresge K, Mozzoli M. FFA cause hepatic insulin resistance by inhibiting insulin suppression of glycogenolysis. Am J Physiology-Endocrinology Metabolism. 2002;283(1):E12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boden G. Fatty acid—induced inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and liver. Curr Diab Rep. 2006;6(3):177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhai W, Xu C, Ling Y, Liu S, Deng J, Qi Y, et al. Increased lipolysis in adipose tissues is associated with elevation of systemic free fatty acids and insulin resistance in perilipin null mice. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42(04):247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roche HM, Phillips C, Gibney MJ. The metabolic syndrome: the crossroads of diet and genetics. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2005;64(3):371-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Angelova P, Boyadjiev N. A review on the models of obesity and metabolic syndrome in rats. Trakia J Sci. 2013;11(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lottenberg AM, Afonso MS, Lavrador MSF, Machado RM, Nakandakare ER. The role of dietary fatty acids in the pathology of metabolic syndrome. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23(9):1027–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White B. Dietary fatty acids. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(4):345–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moussavi N, Gavino V, Receveur O. Could the quality of dietary fat, and not just its quantity, be related to risk of obesity?? Obesity. 2008;16(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fedor D, Kelley DS. Prevention of insulin resistance by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metabolic Care. 2009;12(2):138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buettner R, Parhofer K, Woenckhaus M, Wrede C, Kunz-Schughart LA, Scholmerich J, et al. Defining high-fat-diet rat models: metabolic and molecular effects of different fat types. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;36(3):485–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saraswathi V, Kumar N, Gopal T, Bhatt S, Ai W, Ma C, et al. Lauric acid versus palmitic acid: effects on adipose tissue inflammation, insulin resistance, and Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease in obesity. Biology. 2020;9(11):346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin HV, Frassetto A, Kowalik EJ Jr, Nawrocki AR, Lu MM, Kosinski JR, et al. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z, Yi C-X, Katiraei S, Kooijman S, Zhou E, Chung CK, et al. Butyrate reduces appetite and activates brown adipose tissue via the gut-brain neural circuit. Gut. 2018;67(7):1269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward RE, Martin RJ, Lefevre M, et al. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henagan TM, Stefanska B, Fang Z, Navard AM, Ye J, Lenard NR, et al. Sodium butyrate epigenetically modulates high-fat diet-induced skeletal muscle mitochondrial adaptation, obesity and insulin resistance through nucleosome positioning. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172(11):2782–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aguilar E, Leonel A, Teixeira L, Silva A, Silva J, Pelaez J, et al. Butyrate impairs atherogenesis by reducing plaque inflammation and vulnerability and decreasing NFκB activation. Nutr Metabolism Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24(6):606–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.den Besten G, Bleeker A, Gerding A, van Eunen K, Havinga R, van Dijk TH, et al. Short-Chain fatty acids protect against High-Fat Diet–Induced obesity via a PPARγ-Dependent switch from lipogenesis to fat oxidation. Diabetes. 2015;64(7):2398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unger AL, Torres-Gonzalez M, Kraft J. Dairy fat consumption and the risk of metabolic syndrome: an examination of the saturated fatty acids in dairy. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palomer X, Pizarro-Delgado J, Barroso E, Vázquez-Carrera M. Palmitic and oleic acid: the Yin and Yang of fatty acids in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Trends Endocrinol Metabolism. 2018;29(3):178–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang M, Wei D, Mo C, Zhang J, Wang X, Han X, et al. Saturated fatty acid palmitate-induced insulin resistance is accompanied with myotube loss and the impaired expression of health benefit myokine genes in C2C12 myotubes. Lipids Health Dis. 2013;12(1):104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carta G, Murru E, Banni S, Manca C. Palmitic acid: physiological role, metabolism and nutritional implications. Front Physiol. 2017;8:902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu Y, Cheng J, Chen L, Li C, Chen G, Gui L, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress involved in high-fat diet and palmitic acid-induced vascular damages and Fenofibrate intervention. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akter S, Akhter H, Chaudhury HS, Rahman MH, Gorski A, Hasan MN, et al. Dietary carbohydrates: pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets to obesity-associated metabolic syndrome. BioFactors. 2022;48(5):1036–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griel AE, Ruder EH, Kris-Etherton PM. The changing roles of dietary carbohydrates: from simple to complex. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(9):1958–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Angelova P, Boyadjiev N. A review on the models of obesity and metabolic syndrome in rats. TJS. 2013;1:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seo YS, Lee H-B, Kim Y, Park H-Y. Dietary carbohydrate constituents related to gut dysbiosis and health. Microorganisms. 2020;8(3):427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Legeza B, Marcolongo P, Gamberucci A, Varga V, Bánhegyi G, Benedetti A, et al. Fructose, glucocorticoids and adipose tissue: implications for the metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2017;9(5):426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merino B, Fernández-Díaz CM, Cózar-Castellano I, Perdomo G. Intestinal Fructose and glucose metabolism in health and disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(1):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nagai Y, Nishio Y, Nakamura T, Maegawa H, Kikkawa R, Kashiwagi A. Amelioration of high fructose-induced metabolic derangements by activation of PPARα. Am J Physiology-Endocrinology Metabolism. 2002;282(5):E1180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mukai Y, Kumazawa M, Sato S. Fructose intake during pregnancy up-regulates the expression of maternal and fetal hepatic sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c in rats. Endocrine. 2013;44(1):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, Wang J, Gu T, Yamahara J, Li Y. Oleanolic acid supplement attenuates liquid fructose-induced adipose tissue insulin resistance through the insulin receptor substrate-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmcol. 2014;277(2):155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DiNicolantonio JJ, Mehta V, Onkaramurthy N, O’Keefe JH. Fructose-induced inflammation and increased cortisol: A new mechanism for how sugar induces visceral adiposity. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alzamendi A, Giovambattista A, Raschia A, Madrid V, Gaillard RC, Rebolledo O, et al. Fructose-rich diet-induced abdominal adipose tissue endocrine dysfunction in normal male rats. Endocrine. 2009;35(2):227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crescenzo R, Bianco F, Coppola P, Mazzoli A, Valiante S, Liverini G, et al. Adipose tissue remodeling in rats exhibiting fructose-induced obesity. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53(2):413–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hao L, Lu X, Sun M, Li K, Shen L, Wu T. Protective effects of L-arabinose in high-carbohydrate, high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Food Nutr Res. 2015;59(1):28886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Panchal SK, Poudyal H, Iyer A, Nazer R, Alam A, Diwan V, et al. High-carbohydrate, high-fat diet–induced metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular remodeling in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;57(5):611–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alam MA, Kauter K, Brown L. Naringin improves Diet-Induced cardiovascular dysfunction and obesity in high carbohydrate, high fat Diet-Fed rats. Nutrients. 2013;5(3):637–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poudyal H, Panchal S, Brown L. Comparison of purple Carrot juice and β-carotene in a high-carbohydrate, high-fat diet-fed rat model of the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(9):1322–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reda D, Elshopakey GE, Mahgoub HA, Risha EF, Khan AA, Rajab BS, et al. Effects of Resveratrol against induced metabolic syndrome in rats: role of oxidative stress, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2022;2022:3362005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhandarkar NS, Brown L, Panchal SK. Chlorogenic acid attenuates high-carbohydrate, high-fat diet–induced cardiovascular, liver, and metabolic changes in rats. Nutr Res. 2019;62:78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mohamed SM, Shalaby MA, El-Shiekh RA, El-Banna HA, Emam SR, Bakr AF. Metabolic syndrome: risk factors, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management with natural approaches. Food Chem Adv. 2023;3:100335. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lakshmy R. Metabolic syndrome: role of maternal undernutrition and fetal programming. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14(3):229–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamaguchi M, Takeda N, Kojima T, Ohbora A, Kato T, Sarui H, et al. Identification of individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by the diagnostic criteria for the metabolic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(13):1508–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reda D, Elshopakey GE, Albukhari TA, Almehmadi SJ, Refaat B, Risha EF et al. Vitamin D3 alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats by inhibiting hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation via the SREBP-1-c/ PPARα-NF-κB/IR-S2 signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2023;Volume 14–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Ng CH, Huang DQ, Nguyen MH. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease versus metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: prevalence, outcomes and implications of a change in name. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28(4):790–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paschos P, Paletas K. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome. Hippokratia. 2009;13(1):9–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tarantino G, Citro V, Balsano C. Liver-spleen axis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15(7):759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barrea L, Di Somma C, Muscogiuri G, Tarantino G, Tenore GC, Orio F, et al. Nutrition, inflammation and liver-spleen axis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58(18):3141–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brummer C, Singer K, Renner K, Bruss C, Hellerbrand C, Dorn C, et al. The spleen-liver axis supports obesity-induced systemic and fatty liver inflammation via MDSC and NKT cell enrichment. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2025;601:112518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baccan GC, Hernández O, Díaz LE, Gheorghe A, Pozo-Rubio T, Marcos A et al. Changes in lymphocyte subsets and functions in spleen from mice with high fat diet-induced obesity. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2013;72(OCE1):E63.

- 76.Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rinaldi L, Pafundi PC, Galiero R, Caturano A, Morone MV, Silvestri C, et al. Mechanisms of Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease in the metabolic syndrome. Narrative Rev Antioxid. 2021;10(2):270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.De A, Bhagat N, Mehta M, Taneja S, Duseja A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) definition is better than MAFLD criteria for lean patients with NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2024;80(2):e61–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gambardella ML, Abenavoli L. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated steatotic liver disease vs. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated fatty liver disease: which option is the better choice?? Br J Hosp Med. 2025;86(2):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78(6):1966–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Younossi ZM, Kalligeros M, Henry L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31(Suppl):S32–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lim S, Kim J-W, Targher G. Links between metabolic syndrome and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Trends Endocrinol Metabolism. 2021;32(7):500–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fonseca MT, Moretti EH, Marques LM, Machado BF, Brito CF, Guedes JT, et al. A leukotriene-dependent spleen-liver axis drives TNF production in systemic inflammation. Sci Signal. 2021;14(679):eabb0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martín-Mateos R, Albillos A. The role of the Gut-Liver axis in metabolic Dysfunction-Associated fatty liver disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Heeren J, Scheja L. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and lipoprotein metabolism. Mol Metabolism. 2021;50:101238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, Okamura T, Nakanishi N, Obora A, Kojima T, et al. Metabolic associated fatty liver disease is a risk factor for chronic kidney disease. J Diabetes Invest. 2022;13(2):308–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alnami A, Bima A, Alamoudi A, Eldakhakhny B, Sakr H, Elsamanoudy A. Modulation of dyslipidemia markers Apo b/apo A and Triglycerides/HDL-Cholesterol ratios by Low-Carbohydrate High-Fat diet in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2022;14(9):1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lechner K, McKenzie AL, Kränkel N, Von Schacky C, Worm N, Nixdorff U, et al. High-Risk atherosclerosis and metabolic phenotype: the roles of ectopic adiposity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and inflammation. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2020;18(4):176–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Semenkovich CF. Insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1813–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mooradian AD. Dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Reviews Endocrinol. 2009;5(3):150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bosomworth NJ. Approach to identifying and managing atherogenic dyslipidemia: a metabolic consequence of obesity and diabetes. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(11):1169–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Calderón B, Gómez-Martín JM, Vega-Piñero B, Martín-Hidalgo A, Galindo J, Luque-Ramírez M, et al. Prevalence of male secondary hypogonadism in moderate to severe obesity and its relationship with insulin resistance and excess body weight. Andrology. 2016;4(1):62–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.group TREAsPcw. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Witchel SF, Tena-Sempere M. The Kiss1 system and polycystic ovary syndrome: lessons from physiology and putative pathophysiologic implications. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(1):12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Caserta D, Adducchio G, Picchia S, Ralli E, Matteucci E, Moscarini M. Metabolic syndrome and polycystic ovary syndrome: an intriguing overlapping. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(6):397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Essah PA, Wickham EP. The metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50(1):205–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jemaa M, Khessairi N, Ayari S, Oueslati I, Yazidi M, Chihaoui M, editors. Polycystic ovarian syndrome and metabolic syndrome. Endocrine Abstracts; 2021.

- 98.Galluzzo A, Amato MC, Giordano C. Insulin resistance and polycystic ovary syndrome. Nutr Metabolism Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18(7):511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ovalle F, Azziz R. Insulin resistance, polycystic ovary syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(6):1095–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mishra JS, More AS, Kumar S. Elevated androgen levels induce hyperinsulinemia through increase in Ins1 transcription in pancreatic beta cells in female rats†. Biol Reprod. 2018;98(4):520–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Salva-Pastor N, López-Sánchez GN, Chávez-Tapia NC, Audifred-Salomón JR, Niebla-Cárdenas D, Topete-Estrada R, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome with feasible equivalence to overweight as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease development and severity in Mexican population. Ann Hepatol. 2020;19(3):251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rathi A, Goswami D, Garg A, Kaushik S, Dhiman N. Prevalence and predictors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and metabolic dysfunction‐associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) in Indian women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2025;51(6):e16335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Macut D, Bjekić-Macut J, Rahelić D, Doknić M. Insulin and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;130:163–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Han TS, Lean MEJ. Metabolic syndrome. Medicine. 2015;43(2):80–7. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Assyov Y, Gateva A, Karamfilova V, Gatev T, Nedeva I, Velikova T, et al. Impact of testosterone treatment on Circulating Irisin in men with late-onset hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):1381–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Carnegie C. Diagnosis of hypogonadism: clinical assessments and laboratory tests. Rev Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 6):S3–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Basaria S. Male hypogonadism. Lancet. 2014;383(9924):1250–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Noce A, Marrone G, Di Daniele F, Di Lauro M, Pietroboni Zaitseva A, Wilson Jones G, et al. Potential cardiovascular and metabolic beneficial effects of ω-3 PUFA in male obesity secondary hypogonadism syndrome. Nutrients. 2020;12(9):2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rastrelli G, Filippi S, Sforza A, Maggi M, Corona G. Metabolic syndrome in male hypogonadism. Metabolic Syndrome Consequent Endocr Disorders. 2018;49:131–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Morelli A, Sarchielli E, Comeglio P, Filippi S, Vignozzi L, Marini M, et al. Metabolic syndrome induces inflammation and impairs gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the preoptic area of the hypothalamus in rabbits. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382(1):107–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Quennell JH, Howell CS, Roa J, Augustine RA, Grattan DR, Anderson GM. Leptin deficiency and Diet-Induced obesity reduce hypothalamic Kisspeptin expression in mice. Endocrinology. 2011;152(4):1541–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bellastella G, Menafra D, Puliani G, Colao A, Savastano S. How much does obesity affect the male reproductive function? Int J Obes Supplements. 2019;9(1):50–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Berg WT, Miner M. Hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome: review and update. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2020;27(6). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 114.Naifar M, Rekik N, Messedi M, Chaabouni K, Lahiani A, Turki M, et al. Male hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome. Andrologia. 2015;47(5):579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Polari L, Yatkin E, Martínez Chacón MG, Ahotupa M, Smeds A, Strauss L, et al. Weight gain and inflammation regulate aromatase expression in male adipose tissue, as evidenced by reporter gene activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;412:123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Makhsida N, Shah JAY, Yan G, Fisch H, Shabsigh R. Hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome: implications for testosterone therapy. J Urol. 2005;174(3):827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang C, Jackson G, Jones T, Matsumoto A, Nehra A, Perelman M, et al. Low testosterone associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome contributes to sexual dysfunction and cardiovascular disease risk in men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1669–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kelly DM, Jones TH. Testosterone: a metabolic hormone in health and disease. J Endocrinol. 2013;217(3):R25–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]