Abstract

Background

The global burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is increasing, particularly in resource-limited settings like rural China. Although traditional blood glucose remains an essential measurement for diabetes screening, Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) is emerging as a complementary predictor of T2DM risk. Over time, however, the association between AIP and T2DM risk remains insufficiently understood.

Objective

To investigate the association between baseline AIP levels and its 5-year changes with the risk of T2DM in a rural Chinese cohort.

Methods

This prospective cohort study enrolled 14,968 participants without baseline diabetes from a rural Chinese population. AIP was calculated (log(TG/HDL-C)) and used to classify participant results into quartiles. We conducted multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, restricted cubic spline analyses, subgroup analyses, and sensitivity analyses to determine the association between baseline AIP and 5-year changes in AIP with the 10-year risk of T2DM.

Results

Over a median follow-up of 10.4 years, 2,165(N = 14,968) participants developed T2DM. The hazard ratios [aHRs; 95% confidence interval (CI)] for T2DM increased with quartiles 2, 3, and 4 (versus quartile 1) of AIP: 1.17 (1.00–1.38), 1.38 (1.18–1.62), and 1.96 (1.68–2.29), respectively (p for trend < 0.0001) after multivariable adjustment. Regarding 5-year changes in AIP, participants with increased AIP levels had a 18% higher risk of developing T2DM (aHRs 1.18, 95% CIs: 1.00–1.40) compared to those maintaining stable levels, while those with decreased AIP showed a 20% reduction in risk (aHRs 0.80, 95% CIs: 0.67–0.95). RCS analyses showed linear relationships for both baseline AIP (p for nonlinearity = 0.927) and 5-year changes in AIP (p for nonlinearity = 0.083) with T2DM risk.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that both baseline AIP levels and the 5-year changes in those levels are significantly associated with the risk of T2DM. Individuals with higher baseline AIP or 5-year increases in AIP were more likely to develop T2DM.

Graphical Abstract

The atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) is a lipid marker associated with cardiovascular risk. This study examined its association with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) over a 10-year period, focusing on baseline AIP and its 5-year changes. During a median follow-up of 10.4 years, 2,165 participants developed T2DM. Higher levels of AIP were associated with a significantly increased risk of T2DM. Participants with increased AIP had a higher risk of T2DM, while those with decreased AIP had a reduced risk. Our findings suggest that both baseline AIP and its dynamic changes over time are strong predictors of T2DM risk, highlighting its potential role in diabetes prevention and management

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12933-025-02903-5.

Keywords: Atherogenic index of plasma, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Change in AIP, Hazard ratio, Cohort study

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has become a major global health challenge, with its prevalence rising dramatically over recent decades. The International Diabetes Federation reported that 463 million adults worldwide were living with diabetes in 2019, representing approximately 1 in 10 adults, with this number projected to reach 700 million by 2045 [1]. The prevention and control of T2DM is still a major public health issue, particularly in resource-limited rural areas where healthcare access and preventive services remain challenging.

Traditional indicators for diagnosing T2DM, such as fasting blood glucose (FBG) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), remain indispensable for diabetes diagnosis and monitoring [2]; however, these glycemic markers primarily reflect established metabolic disturbances rather than early pathophysiological changes. The identification of early predictive markers is crucial for preventive intervention, particularly for complex metabolic pathogenesis. Lipid metabolism abnormalities have emerged as promising early indicators, as they often manifest before overt glycemic disruption [3]. Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) is defined as the logarithmic transformation of the ratio of triglycerides (TG) to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), which reflects the balance between pro-atherogenic and anti-atherogenic lipoproteins, potentially providing a useful measure of lipid metabolism disturbances [4]. Compared with other complex lipid indicators, AIP is serving as a surrogate marker for small dense low-density lipoprotein particles, which are hallmarks of insulin resistance and directly participate in β-cell dysfunction [5].

Previous epidemiological studies hasreported a positive association between AIP and T2DM risk [6, 7]; however, several notable knowledge gaps still remain. First, most studies were based on cross-sectional design, limiting the ability to infer causality [8–11]. Second, the few existing cohort studies had relatively short follow-up periods (3–7 years), suggesting the value of longer-term prospective data to better understand the temporal relationship between AIP and T2DM [7, 12]. Third, there is limited evidence regarding the combined influence of initial AIP levels and subsequent longitudinal changes in AIP levels on long-term T2DM risk.

Therefore, we conducted a prospective cohort study in a rural Chinese population to examine whether both baseline and 5-year changes in AIP were associated with 10-year risk of T2DM.

Methods

Study population and inclusion/exclusion criteria

The present study utilized data from the Rural Chinese Cohort Study (RCCS), a prospective cohort established in 2007–2008 to investigate non-communicable disease risk factors among rural populations [13]. Initially, 20,194 participants aged ≥ 18 years were enrolled. Two follow-up surveys were conducted in 2013–2014 (response rate: 85.50%, n = 17,265) and 2018–2020 (response rate: 92.86%, n = 18,752), respectively.

In this study, participants were excluded if they had a diagnosis of diabetes at baseline (n = 1,710), had missing baseline data on triglycerides (n = 37) or HDL-cholesterol (n = 17), or were using lipid-lowering medications (n = 1,076) at baseline. Further exclusions were made for participants who were lost to follow-up or had unknown T2DM status at the 10-year follow-up (n = 2,386), resulting in 14,968 participants finally being included in the baseline analysis (Figure S1). For the 5-year changes analysis, we applied the same baseline exclusion criteria to the data, resulting in a final sample of 8,868 participants (Figure S1).

All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Zhengzhou University Medical Ethics Committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Covariates

Socio-demographic characteristics were gathered through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire. Smoking status was classified as either never-smokers (who had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime) or smokers (who had smoked 100 or more cigarettes). Alcohol consumption was defined as drinking alcohol more than 12 times in the past year; otherwise, participants were defined as non-drinkers. Physical activity was categorized as either ideal or non-ideal based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Ideal physical activity was defined as engaging in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity activity, 75 min of vigorous-intensity activity, or an equivalent combination of both per week. Participants who did not meet these criteria were classified as having non-ideal physical activity. A family history of diabetes was defined as having at least one first-degree relative diagnosed with diabetes.

Anthropometric measurements were performed with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes. Body weight and height were measured to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Waist circumference (WC) was measured twice, with the average of the two readings used for analysis. Central obesity was defined as WC ≥ 90 cm for men or ≥ 80 cm for women, or a waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) ≥ 0.5. Blood pressure was measured by trained personnel using an electronic sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM-770AFuzzy, Kyoto, Japan) after the participant had rested for at least 5 min in a seated position. Three measurements were taken at 30-second intervals, with the average of the three readings used for analysis.

Fasting blood samples were collected after an overnight fast of at least 8 h. Levels of fasting plasma glucose (FPG), TG, total cholesterol (TC), and HDL-C were measured using a HITACHI automatic clinical analyzer (Model 7060, Tokyo, Japan). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated using the Friedewald formula.

Exposure

AIP was calculated as described in reference [14], using TG and HDL-C concentrations in mmol/L.

|

Outcome

T2DM was diagnosed as a fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, and/or an HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, and/or the use of antidiabetic medications, and/or a self-reported history of diabetes mellitus [15].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables with normal distribution are presented as means (standard deviations); otherwise they are presented as medians (interquartile ranges [IQR]). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages). The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed to assess group differences for variables deviating from normal distribution, while t-tests were conducted for normally distributed continuous variables to perform hypothesis tests on the differences in their means between groups. Categorical data were analyzed using Chi-square tests to assess for statistically significant differences in proportions between groups. Variable selection was guided by a directed acyclic graph (Figure S2) and validated through LASSO regression with cross-validation (Table S1).

Baseline AIP values were categorized into four quartiles (Q1–Q4) for stratified analyses. 5-year changes in AIP were determined by calculating the difference between the 5-year follow-up AIP and baseline AIP. Participants were classified into three groups based on quartiles of 5-year changes in AIP: a decreased group (Q1), a stable group (combined Q2 and Q3, representing minimal change around 0), and an increased group (Q4).

Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to evaluate the association between AIP and the risk of T2DM. Gender, age, marital status, education, income, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, family history of diabetes, BMI, systolic blood pressure, and TC were adjusted for in the multivariate models. The linear trends across AIP quartile groups were evaluated by treating the quartile variable (Q1-Q4) as a continuous variable in the Cox models. In addition, subgroup analyses were incorporated into the AIP analysis to evaluate potential effect modification by gender, age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and family history of diabetes. Interaction terms between AIP and each of these factors were included in the Cox models to test for statistically significant interactions. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was also conducted to assess dose-response relationships between AIP and the risk of T2DM, with p-values for nonlinearity computed. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding participants with different conditions to assess the robustness of our findings. To evaluate the incremental predictive value of AIP, we performed net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) analyses using continuous NRI methodology and bootstrap resampling. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.4.1), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. Among 14,968 participants included in this prospective cohort study, 2,165 developed T2DM during a median follow-up of 10.4 years. At baseline, the median age was 51, with 39.93% males. Participants who developed T2DM showed a higher proportion of those who were females (63.23%), those married (92.24%), those with education levels below high school (91.50%), individuals with a family history of diabetes (9.98%), and those who had used antihypertensive medications (15.47%) compared to those without T2DM (all p < 0.05). Those who developed T2DM showed higher levels of WC, BMI, SBP, DBP, FPG, TC, TG, LDL-C, and AIP compared to those without T2DM (all p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants stratified by T2DM status

| Characteristics | Overall (N = 14968) |

Non-T2DM (n = 12803) |

T2DM (n = 2165) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 5,977 (39.93%) | 5,181 (40.47%) | 796 (36.77%) | |

| Female | 8,991 (60.07%) | 7,622 (59.53%) | 1,369 (63.23%) | |

| Age (years) | 51.00 (19.00) | 50.00 (20.00) | 52.00 (16.00) | < 0.001 |

| Marital Status | 0.005 | |||

| Married/Cohabitating | 13,551 (90.57%) | 11,555 (90.29%) | 1,996 (92.24%) | |

| Unmarried/Divorced/widowed | 1,411 (9.43%) | 1,243 (9.71%) | 168 (7.76%) | |

| Education Level | 0.030 | |||

| Lower Secondary | 13,500 (90.19%) | 11,519 (89.97%) | 1,981 (91.50%) | |

| Higher Secondary | 1,468 (9.81%) | 1,284 (10.03%) | 184 (8.50%) | |

| Income | 0.359 | |||

| Low Income | 13,950 (93.46%) | 11,921 (93.38%) | 2,029 (93.94%) | |

| High Income | 976 (6.54%) | 845 (6.62%) | 131 (6.06%) | |

| Physical Activity | 0.482 | |||

| Non-Ideal (sedentary lifestyle) | 2,907 (19.42%) | 2,499 (19.52%) | 408 (18.85%) | |

| Ideal | 12,061 (80.58%) | 10,304 (80.48%) | 1,757 (81.15%) | |

| Smoking Status | 0.125 | |||

| Non-Smoker | 10,709 (71.68%) | 9,127 (71.44%) | 1,582 (73.07%) | |

| Smoker | 4,232 (28.32%) | 3,649 (28.56%) | 583 (26.93%) | |

| Alcohol Consumption | 0.655 | |||

| Non-Drinker | 13,244 (88.48%) | 11,335 (88.53%) | 1,909 (88.18%) | |

| Drinker | 1,724 (11.52%) | 1,468 (11.47%) | 256 (11.82%) | |

| Family History of Diabetes | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 11,352 (93.76%) | 9,783 (94.39%) | 1,569 (90.02%) | |

| Yes | 755 (6.24%) | 581 (5.61%) | 174 (9.98%) | |

| Antihypertensive Drug Use | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 13,349 (89.18%) | 11,519 (89.97%) | 1,830 (84.53%) | |

| Yes | 1,619 (10.82%) | 1,284 (10.03%) | 335 (15.47%) | |

| WC (cm) | 81.00 (14.25) | 80.05 (13.75) | 87.30 (14.20) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.79 (4.77) | 23.51 (4.57) | 25.67 (4.97) | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 121.67 (25.00) | 120.67 (24.67) | 126.33 (25.67) | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.00 (14.67) | 76.33 (14.33) | 80.00 (15.00) | < 0.001 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.30 (0.69) | 5.25 (0.65) | 5.65 (0.87) | < 0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.35 (1.17) | 4.31 (1.17) | 4.57 (1.15) | < 0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.32 (0.94) | 1.27 (0.89) | 1.64 (1.22) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.14 (0.33) | 1.15 (0.33) | 1.09 (0.31) | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.50 (1.00) | 2.50 (1.00) | 2.60 (0.90) | < 0.001 |

| AIP | 0.06 (0.37) | 0.04 (0.36) | 0.18 (0.38) | < 0.001 |

All variables are reported as median (IQR) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables

p values for normally distributed continuous variables were calculated using t-tests, while non-normally distributed variables were analyzed with the Kruskal-Wallis test. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant

Low income was defined as monthly income ≤ 500 RMB, and high income as monthly income > 500 RMB

Physical activity was categorized as “Ideal” for those meeting WHO recommendations for weekly exercise and “Non-Ideal” otherwise

WC, Waist Circumference; BMI, Body Mass Index; SBP, Systolic Blood Pressure; DBP, Diastolic Blood Pressure; FPG, Fasting Plasma Glucose; TC, Total Cholesterol; TG, Triglycerides; HDL-C, High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; LDL-C, Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

Table S2 shows baseline characteristics by quartiles of the AIP. A gradual increase in the proportion of males (from 36.93% in Q1 to 41.58% in Q4), smokers (from 25.68% to 30.19%), and alcohol drinkers (from 10.53% to 13.58%) is evident. The use of antihypertensive drugs also showed an increasing trend, rising from 7.30% in Q1 to 14.99% in Q4. Waist circumference increased from 75.90 cm in Q1 to 87.00 cm in Q4, while BMI rose from 22.20 to 25.48 kg/m2. Similarly, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, and triglycerides showed progressive increases across AIP quartiles. Conversely, HDL-C levels declined from 1.36 in Q1 to 0.97 mmol/L in Q4 (all p < 0.001).

Association between baseline AIP and 10-year T2DM risk

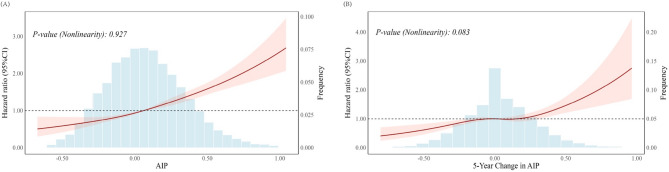

Table 2; Fig. 1(A) present the results of Cox proportional hazards models and RCS analysis for the association and dose-response relationship between AIP and the risk of T2DM. In the unadjusted model (Model a), compared to Q1 of AIP, the HRs of T2DM risk for Q2, Q3, and Q4 were 1.49 (95% CIs: 1.29–1.73), 2.04 (95% CIs: 1.77–2.34), and 3.36 (95% CIs: 2.95–3.83), respectively. After adjusting for gender, age, education, marital, income, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, family history of diabetes, BMI, systolic blood pressure and TC, the HRs of T2DM risk for Q2, Q3, and Q4 remained significant at 1.17 (95% CIs: 1.00–1.38), 1.38 (95% CIs: 1.18–1.62), and 1.96 (95% CIs: 1.68–2.29), respectively, with a significant linear trend across quartile groups (p for trend < 0.0001). Additionally, each 1-standard deviation (SD) increase in AIP was associated with a 33% increased risk of T2DM (aHR: 1.33; 95% CI: 1.26–1.39). The RCS analysis visually corroborates these findings, demonstrating a linear dose-dependent increase of baseline AIP with T2DM risk (p for nonlinearity = 0.927).

Table 2.

Association between baseline AIP and 10-year risk of T2DM

| AIP Quartile Groups | Cases/N | HRs (95% CIs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d | ||

| Q1 (−0.78~−0.12) | 301/3742 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Q2 (−0.12 ~ 0.06) | 422/3742 | 1.49 (1.29–1.73) | 1.45 (1.25–1.69) | 1.37 (1.16–1.62) | 1.17 (1.00-1.38) |

| Q3 (0.06 ~ 0.25) | 570/3742 | 2.04 (1.77–2.34) | 1.91 (1.66–2.20) | 1.81 (1.55–2.11) | 1.38 (1.18–1.62) |

| Q4 (0.25 ~ 1.13) | 872/3742 | 3.36 (2.95–3.83) | 3.20 (2.80–3.64) | 3.02 (2.61–3.49) | 1.96 (1.68–2.29) |

| Per SD | 1.57 (1.51–1.63) | 1.55 (1.49–1.62) | 1.55 (1.48–1.62) | 1.33 (1.26–1.39) | |

| P for trend | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

a Unadjusted model

b Adjusted for age and gender

c Adjusted for variables in model 2 as well as marital status, education level, monthly individual income, smoking status, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and family history of T2DM

d Adjusted for variables in model 3 as well as bmi, systolic blood pressure and total cholesterol

Fig. 1.

Restricted Cubic Spline Analysis of Baseline AIP (A) and 5-year Changes in AIP with 10-year Risk of T2DM. A linear association between AIP and the risk of T2DM was found (P > 0.05). The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, indicating the precision of the estimated association across different levels of AIP and its 5-year changes. The histogram in the background shows the distribution of AIP and its 5-year changes values among the study population

Using receiver-operating characteristic analysis with the Youden-index method, we identified an optimal AIP cut-off of 0.156. Participants were therefore classified into a high-AIP group (AIP ≥ 0.156) and a low-AIP group (AIP < 0.156). In multivariable models, individuals in the high-AIP group exhibited a 63% higher risk of incident T2DM than those in the low-AIP group (adjusted HR = 1.632, 95% CI 1.48–1.80). To assess the clinical utility of adding AIP to conventional risk prediction models, we conducted NRI and IDI analyses (Table S3). Even in the fully adjusted clinical model containing comprehensive traditional risk factors, AIP provided clinically meaningful incremental value with NRI of 0.237 (p < 0.001) and IDI of 0.0113 (p < 0.001).

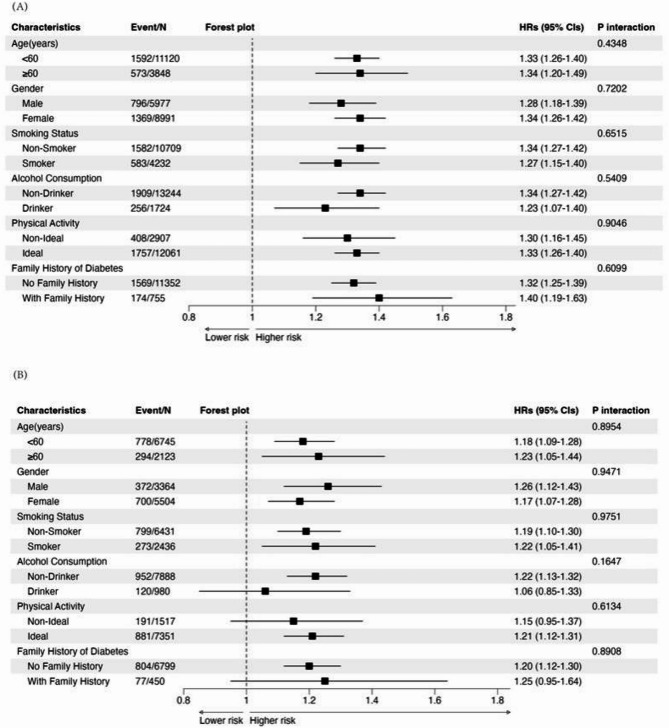

Figure 2(A) illustrates the HRs and 95% CIs for the risk of T2DM among subgroups stratified by gender, age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and family history of diabetes. The positive association between baseline AIP and T2DM risk was consistently observed across different age groups (< 60 years: aHRs 1.33, 95% CI 1.26–1.40; ≥60 years: aHRs 1.34, 95% CI 1.20–1.49), genders (male: aHRs 1.28, 95% CI 1.18–1.39; female: aHRs 1.34, 95% CI 1.26–1.42), and smoking status (non-smoker: aHRs 1.34, 95% CI 1.27–1.42; smoker: aHRs 1.27, 95% CI 1.15–1.40). Similar patterns were observed for alcohol consumption, physical activity, and family history of diabetes. No significant multiplicative interactions were found between baseline AIP and any of the demographic or lifestyle factors (all p for interaction > 0.05), indicating that the association between baseline AIP and T2DM risk was homogeneous across these subgroups. Following this initial subgroup analysis, we conducted a stratified analysis based on baseline AIP levels (Table S4) which showed that within each subgroup the HRs for T2DM consistently increased from Q1 to Q4, with the highest risk observed in Q4 (p for trend < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Subgroup Analysis of the Association Between Baseline AIP (A) and 5-year Changes in AIP (B) with

To test the robustness of our findings regarding baseline AIP, sensitivity analyses were conducted using four additional models (Models e–h) (Table S5). Excluding participants with cardiovascular disease, cancer, and renal failure in Model e, the T2DM risk increased by 48% per 1-SD increase in AIP (aHR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.41–1.55). After excluding those with impaired fasting glucose in Model f, the risk was 44% (aHR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.36–1.52). Excluding participants with dyslipidemia in Model g, the risk increase was 35% (aHR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.26–1.43). Finally, in Model h, excluding individuals who developed T2DM within 1 year, the risk increased by 47% (aHR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.40–1.54).

We performed mediation analysis to examine whether WC mediates the association between AIP and T2DM risk (Figure S3 and Table S6). In the total effect model, AIP was significantly associated with increased T2DM risk (HR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.23–1.57). When WC was included as a mediator, the natural direct effect of AIP on T2DM remained significant (HR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.78–1.14), while the natural indirect effect through WC was also significant (HR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.40–0.53). WC mediated 33.19% (95% CI: 26.68%−39.69%) of the total association between AIP and T2DM risk. The RCS analysis stratified by WC status further demonstrated linear dose-dependent relationships between baseline AIP and T2DM risk in both normal waist circumference (p for nonlinearity = 0.229) and abdominal obesity groups (p for nonlinearity = 0.672) (Figure S4).

Association between 5-year changes in AIP and 10-year T2DM risk

Table 3; Fig. 1(B) show the association and dose-response relationship between 5-year changes in AIP and the risk of T2DM. In the unadjusted model (Model a), compared with the stable group, participants in the decreased group had a 26% lower risk of T2DM (HRs: 0.74; 95% CIs: 0.63–0.86), whereas those in the increased group had an 18% higher risk (HRs: 1.18; 95% CIs: 1.02–1.38). After adjusting for gender, age, education, marital status, income, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, family history of diabetes, systolic blood pressure, TC and BMI, the aHRs of T2DM risk for the decreased and increased groups were 0.80(95% CIs: 0.67–0.95) and 1.20 (95% CIs: 1.00–1.40), respectively, with a significant linear trend across groups (p for trend < 0.0001). Further, each 1-SD increase in the 5-year changes in AIP was associated with a 22% increase in T2DM risk (aHR: 1.20; 95% CIs: 1.11–1.29) in the fully-adjusted model (Model d). The RCS analysis confirmed a linear dose-dependent increase of 5-year changes in AIP with T2DM risk (p for nonlinearity = 0.083).

Table 3.

Association between 5-year changes in AIP and 10-year risk of T2DM

| 5-year Changes in AIP | Cases/N | HRs (95% CIs) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d | |||||

| Decrease | 279/2217 | 0.74 (0.63–0.86) | 0.73 (0.63–0.86) | 0.75 (0.63–0.89) | 0.80 (0.67–0.95) | |||

| Stable | 528/4434 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | |||

| Increase | 265/2217 | 1.18 (1.02–1.38) | 1.20 (1.03–1.39) | 1.26 (1.06–1.48) | 1.18 (1.00-1.40) | |||

| Per SD | 1.24 (1.16–1.32) | 1.25 (1.17–1.33) | 1.24 (1.16–1.34) | 1.20 (1.11–1.29) | ||||

| p for trend | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||

a Unadjusted model

b Adjusted for age and gender

c Adjusted for variables in model 2 as well as marital status, education level, monthly individual income, smoking status, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and family history of T2DM

d Adjusted for variables in model 3 as well as bmi, systolic blood pressure and total cholesterol

Figure 2(B) illustrates the aHRs and 95% CIs for the risk of T2DM among subgroups stratified by gender, age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and family history of diabetes. The positive association between AIP and T2DM risk was observed across different age groups (< 60 years: aHRs 1.18, 95% CI 1.09–1.28; ≥60 years: aHRs 1.23, 95% CI 1.05–1.44), genders (male: aHRs 1.26, 95% CI 1.12–1.43; female: aHRs 1.17, 95% CI 1.07–1.28), and smoking status (non-smoker: aHRs 1.19, 95% CI 1.10–1.30; smoker: aHRs 1.22, 95% CI 1.05–1.41). Similar patterns were observed for alcohol consumption, physical activity, and family history of diabetes. Notably, participants who were non-drinkers (aHRs 1.22, 95% CI 1.13–1.32), had ideal physical activity levels (aHRs 1.21, 95% CI 1.12–1.31), and had no family history of diabetes (aHRs 1.20, 95% CI 1.12–1.30) showed a significant association between 5-year changes in AIP and T2DM risk. No significant multiplicative interactions were found between 5-year changes in AIP and any of the examined demographic or lifestyle factors (all p for interaction > 0.05), indicating that the association between 5-year changes in AIP and T2DM risk was generally consistent across these subgroups.

To test the robustness of our findings regarding 5-year changes in AIP, sensitivity analyses were conducted using four additional models (Models e–h) (Table S4). After excluding participants with cardiovascular disease, cancer, and renal failure in Model e, the risk increased by 23% per 1-SD increment in AIP changes (aHR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.14–1.33). When participants with impaired fasting glucose were excluded in Model f, the risk increase was 16% (aHR: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.06–1.27). Excluding individuals with dyslipidemia in Model g, the risk increase was 12% (aHR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.00–1.26). In Model h, excluding participants who developed T2DM within 1 year after the 5-year follow-up, the risk increase was 22% (aHR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.13–1.31).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of a rural Chinese population with a median follow-up of 10.4 years, we observed that both baseline AIP and its 5-year changes are positively associated with10-year T2DM risk. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses support the robustness of these findings, demonstrating their consistency across different participant characteristics and their stability under various analytical conditions. Moreover, our analysis of 5-year changes in AIP reveals that participants with increased AIP had a 18% higher risk of T2DM relative to those with stable AIP, while participants with decreased AIP had a 20% lower risk. Additionally, RCS analyses showed linear dose-response relationships for both baseline AIP and its 5-year changes with T2DM risk.

AIP is a composite lipid marker because it integrates TG and HDL-C into a single logarithmic ratio, thereby reflecting the balance between pro-atherogenic and anti-atherogenic lipoproteins [4]. Several studies have suggested associations between higher AIP and increased T2DM risk, with recent studies reporting its comparative predictive value relative to traditional lipid ratios [9] and longitudinal investigations showing significant associations with both prediabetes [12] and incident T2DM (HR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.41–1.94) in prospective cohorts [16]. Our choice of AIP was informed by its potential advantages in the context of T2DM prediction. Unlike composite indices that combine lipid and anthropometric measurements, AIP is a pure lipid indicator that may help avoids potential multicollinearity issues when adjusting for body composition variables in statistical models. Moreover, AIP may reflect aspects of the pathophysiological processes related to T2DM—insulin resistance—through its reflection of the TG/HDL-C ratio, which has been proposed as a surrogate for insulin resistance and the presence of highly atherogenic small dense LDL particles.

Our prospective cohort study, conducted in a rural Chinese population with a median 10.4-year follow-up, contributeds to this body of evidence. We found that baseline AIP, when assessed as a continuous variable, was significantly and positively associated with 10-year incident T2DM risk: each 1-SD increase in baseline AIP corresponded to a 33% increased risk (aHR: 1.33; 95% CIs: 1.26–1.39). This finding extends the cross-sectional observations of Liu et al. [9] by providing robust prospective evidence for associations with risk of T2DM over an extended follow-up period in a rural Chinese demographic, rather than just examining associations with prevalent disease. Consistent with these findings, our RCS analyses showed linear dose-response relationships for both baseline AIP and its 5-year changes with T2DM risk, with no evidence of a significant threshold effect. This analysis of continuous, linear associations is consistent with and extends the findings of previous longitudinal studies like Li et al.’s [16], which reported increased risk for categorically “higher” AIP, by providing information on the nature of these associations and examining effects per standardized increment. The consistency of these associations across diverse demographic and clinical characteristics, as shown through our subgroup and sensitivity analyses, supports the stability of these findings in this population. Our mediation analysis revealed that WC accounted for approximately one-third (33.19%) of the association between AIP and T2DM risk, suggesting that abdominal adiposity may play an intermediary role in this relationship. This finding is consistent with research by Ma et al., who demonstrated that waist circumference mediated 12.1% of the association between sleep duration and osteoarthritis, indicating the potential mediating role of central obesity in metabolic disease pathways [17].

In contrast, when examining the pattern of the association, Yin et al. (2023) [10], who analyzed data from the NHANES cohort in the United States, and Sun et al. (2024) [11] who focused on overweight or obese individuals, reported J-shaped relationships, with T2DM risk rising significantly beyond specific AIP thresholds (–0.47 and − 0.07, respectively). Interestingly, in those studies no significant association was observed between AIP and T2DM risk below the identified thresholds, whereas the risk appeared to increase in a linear manner once the threshold was exceeded. Our study, however, showed a linear association between AIP and T2DM risk without a significant threshold effect, suggesting that in our population, the relationship appears to be linear. The differences between these findings may reflect variations in study populations, study designs, or other factors that could influence the pattern of association.

Although baseline AIP provides insights into the association between lipid profiles and T2DM risk, it does not capture the temporal fluctuations that occur in lipid metabolism [18]. Previous research suggests potential benefits of dynamic assessments; Zhang et al., for example, demonstrated that cumulative AIP exposure is associated with an elevated risk of myocardial infarction (MI) in an 11-year cohort of 54,440 Chinese adults, suggesting the potential value of tracking lipid changes over time [19]. Based on this premise, we examined 5-year changes in AIP and their association with T2DM risk—a dynamic perspective that is consistent with several studies examining the association of lipid profile alterations over time with diabetes risk. In our study, participants with markedly increased AIP over a 5-year interval had a significantly higher risk of developing T2DM, whereas those with decreased AIP exhibited a reduced risk, suggesting a potential beneficial effect. This finding indicates associations between persistently elevated AIP and increased T2DM risk. Similarly, Lan et al., using the Kailuan cohort, found that high cumulative AIP exposure, particularly when coupled with chronic inflammation, significantly increased T2DM risk among younger adults [20]. Although we did not explicitly assess inflammatory markers, both studies suggest associations between long-term dyslipidemia—reflected by elevated AIP—and T2DM development. In addition to these observations, Zou et al. demonstrated that in individuals with prediabetes, higher cumulative AIP accelerated progression to diabetes while reducing the chance of reverting to normal glucose levels [21]. Moreover, different from Lan et al., Yi et al. investigated middle-aged and older Chinese adults over a 9-year period, showing that, although a reduction in AIP (that is, a “high–low” trajectory) was associated with some protection, it did not fully restore risk to the level seen in individuals with consistently low AIP (“low–low”) [10]. These findings are consistent with our observation that while lowering AIP appears beneficial, it may not completely offset the associations with prior high exposure.

The observed association between AIP and T2DM risk may be underpinned by several interrelated biological mechanisms. AIP, as a logarithmic ratio of triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, reflects the balance between pro-atherogenic and anti-atherogenic lipoproteins which are closely tied to insulin resistance—a core pathophysiological feature of T2DM [22]. Importantly, AIP offers superior specificity for detecting dyslipidemia pathogenicity compared to individual lipid measurements alone, as it captures not only the TG/HDL-C ratio but also reflects lipoprotein particle size variations [23]. This comprehensive assessment enables AIP to detect subtle changes in lipid metabolism that may precede overt dyslipidemia, making it particularly valuable for identifying individuals at elevated metabolic risk. At the molecular level, elevated triglycerides induce lipotoxicity through activation of PKC and NF-κB pathways, impairing insulin receptor substrate phosphorylation and disrupting insulin signal transduction [24]. Concurrently, lipid overload in pancreatic β-cells triggers ER stress and the unfolded protein response, leading to β-cell apoptosis through CHOP-mediated pathways [25]. HDL-C’s protective effects extend beyond its anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties. Basic studies demonstrate that HDL particles directly enhance glucose uptake through AMPK activation and promote insulin secretion via ABCA1/ABCG1 transporters [26], while suppressing inflammasome activation through TLR4 inhibition [27]. The reduction in HDL-C thus diminishes these protective mechanisms, exacerbating systemic inflammation and disrupting insulin signaling [28]. Furthermore, dyslipidemia reflected by elevated AIP promotes adipocyte dysfunction, characterized by increased pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (TNF-α, IL-6) and reduced adiponectin production [29]. Ceramide accumulation from excessive fatty acid flux activates PP2A phosphatase, leading to AKT dephosphorylation and impaired GLUT4 translocation [30]. These interconnected molecular pathways provide mechanistic explanations for how both baseline AIP levels and their dynamic changes serve as integrated markers of metabolic dysregulation in T2DM pathogenesis.

Our study has several strengths. First, this is one of the prospective cohort investigations to evaluate both baseline AIP and its 5-year changes over more than a decade of follow-up in a rural Chinese population. Second, focusing on 5-year changes in AIP adds a novel dimension, emphasizing that shifts in lipid profiles over time can be critical to understanding T2DM risk. Third, we conducted sensitivity and subgroup analyses which demonstrated the robustness of our findings, reinforcing the assertion that AIP may be a reliable and broadly applicable risk marker across diverse demographic groups.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our findings are derived from a single cohort study conducted in a rural area of China with relatively homogeneous genetic background and socio-economic status. This significantly limits the generalizability of our results when applied to urban populations, different ethnic groups, or populations with varying healthcare systems and dietary patterns. Future studies should prioritize external validation in independent and diverse cohorts before clinical implementation. Second, although we assessed AIP at baseline and the 5-year follow-up, the underlying metabolic indicators (FPG, TG, HDL-C) and other covariates were measured only once at each time point. These biomarkers fluctuate due to diet, physical activity, and stress, and single measurements may introduce measurement error, potentially reducing the reliability of AIP as a predictor. Third, despite our multiple covariate adjustment, residual confounding remains an inherent limitation of observational epidemiology. Finally, this observational design precludes definitive causal inferences; future interventional trials are needed to establish whether reducing AIP directly lowers T2DM risk.

Conclusion

This prospective cohort study provides robust evidence that both baseline AIP and its 5-year changes are significantly and positively associated with T2DM risk. Higher baseline AIP levels were associated with a linear dose-dependent increase in T2DM risk, while marked increases in AIP over five years further amplified this risk. Conversely, reductions in AIP conferred a protective effect, emphasizing the critical role of lipid profile dynamics in diabetes prevention.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the staff and participants of the Rural Chinese Cohort Study for their participation and contribution.

Abbreviations

- WC

Waist Circumference

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- SBP

Systolic Blood Pressure

- DBP

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- FPG

Fasting Plasma Glucose

- TC

Total Cholesterol

- TG

Triglycerides

- HDL-C

High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

Author contributions

LW: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, data curation, writing - original draft, visualization, writing - review & editing. YW, XF, WH, and BG: investigation, writing - review & editing, supervision. AX, CP, and JK: investigation, resources, data curation, project administration. YS and JL: methodology, software, formal analysis. MZ, YZ, and DH: writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82273707, 82373675, and 82304228); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant numbers 2024A1515010972); and the Science and Technology Development Foundation of Shenzhen (grant number JCYJ20220818095818040).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dongsheng Hu, Email: dongshenghu563@126.com.

Yang Zhao, Email: zhaomiemie@126.com.

References

- 1.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157: 107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozery-Flato M, Parush N, El-Hay T, Visockienė Ž, Ryliškytė L, Badarienė J, et al. Predictive models for type 2 diabetes onset in middle-aged subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vergès B. Pathophysiology of diabetic dyslipidaemia: where are we? Diabetologia. 2015;58:886–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobiasova M, Frohlich J. The new atherogenic plasma index (AIP) reflects the ratio of triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol, size of lipoprotein particles and esterification rate of cholesterol: changes after lipanor treatment. Vnitr Lek. 2000;46:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou K, Qin Z, Tian J, Cui K, Yan Y, Lyu S. The atherogenic index of plasma: a powerful and reliable predictor for coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Angiology. 2021;72:934–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.You F-F, Gao J, Gao Y-N, Li Z-H, Shen D, Zhong W-F, et al. Association between atherogenic index of plasma and all-cause mortality and specific-mortality: a nationwide population–based cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi Q, Ren Z, Bai G, Zhu S, Li S, Li C, et al. The longitudinal effect of the atherogenic index of plasma on type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and older Chinese. Acta Diabetol. 2022;59:269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y, Wen M. Sex-specific differences in the effect of the atherogenic index of plasma on prediabetes and diabetes in the NHANES 2011–2018 population. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Fu Q, Su R, Liu R, Wu S, Li K, et al. Association between nontraditional lipid parameters and the risk of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from the National health and nutrition examination survey 2017–2020. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1460280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin B, Wu Z, Xia Y, Xiao S, Chen L, Li Y. Non-linear association of atherogenic index of plasma with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Y, Li F, Zhou Y, Liu A, Lin X, Zou Z, et al. Nonlinear association between atherogenic index of plasma and type 2 diabetes mellitus in overweight and obesity patients: evidence from Chinese medical examination data. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng X, Zhang X, Han Y, Hu H, Cao C. Nonlinear relationship between atherogenic index of plasma and the risk of prediabetes: a retrospective study based on Chinese adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang M, Zhao Y, Sun L, Xi Y, Zhang W, Lu J, et al. Cohort profile: the rural Chinese cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50:723–l724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobiás̆ová M, Frohlich J. The plasma parameter log (TG/HDL-C) as an atherogenic index: correlation with lipoprotein particle size and esterification rate inapob-lipoprotein-depleted plasma (FERHDL). Clin Biochem. 2001;34:583–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia W, Weng J, Zhu D, Ji L, Lu J, Zhou Z, et al. Standards of medical care for type 2 diabetes in China 2019. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35: e3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y-W, Kao T-W, Chang P-K, Chen W-L, Wu L-W. Atherogenic index of plasma as predictors for metabolic syndrome, hypertension and diabetes mellitus in Taiwan citizens: a 9-year longitudinal study. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma G, Xu B, Wang Z, Duan W, Chen X, Zhu L, et al. Non-linear association of sleep duration with osteoarthritis among U.S. middle-aged and older adults. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Liu C, Peng Y, Fang Q, Wei X, Zhang C, et al. Impact of baseline and trajectory of the atherogenic index of plasma on incident diabetic kidney disease and retinopathy in participants with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2024;23:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Chen S, Tian X, Wang P, Xu Q, Xia X, et al. Association between cumulative atherogenic index of plasma exposure and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan Y, Wu D, Cai Z, Xu Y, Ding X, Wu W, et al. Supra-additive effect of chronic inflammation and atherogenic dyslipidemia on developing type 2 diabetes among young adults: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou Y, Lu S, Li D, Huang X, Wang C, Xie G, et al. Exposure of cumulative atherogenic index of plasma and the development of prediabetes in middle-aged and elderly individuals: evidence from the CHARLS cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Chen S, Deng A, Liu X, Liang Y, Shao X, et al. Association between lipid ratios and insulin resistance in a Chinese population. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou B, Rayner AW, Gregg EW, Sheffer KE, Carrillo-Larco RM, Bennett JE, et al. Non-linear association of atherogenic index of plasma with bone mineral density a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 2024;23:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu C, Chen Y, Cline GW, Zhang D, Zong H, Wang Y, et al. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laybutt DR, Preston AM, Åkerfeldt MC, Kench JG, Busch AK, Biankin AV, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to beta cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:752–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drew BG, Duffy SJ, Formosa MF, Natoli AK, Henstridge DC, Penfold SA, et al. High-density lipoprotein modulates glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2009;119:2103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Q, Liu Z, Wei M, Huang Q, Feng J, Liu Z, et al. High-density lipoprotein mediates anti-inflammatory reprogramming of macrophages via the transcriptional regulator ATF3. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:152–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam JS, Kim MK, Park K, Choi A, Kang S, Ahn CW, et al. The plasma atherogenic index is an independent predictor of arterial stiffness in healthy Koreans. Angiology. 2022;73:514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holland WL, Bikman BT, Wang L-P, Yuguang G, Sargent KM, Bulchand S, et al. Lipid-induced insulin resistance mediated by the proinflammatory receptor TLR4 requires saturated fatty acid–induced ceramide biosynthesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(5):1858–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.