Abstract

Background:

Women's Heart Centers (WHC) are comprehensive, multidisciplinary care centers designed to close the existing gap in women's cardiovascular care. The WHC at The Christ Hospital Heart and Vascular Institute (TCH-WHC) in Cincinnati, Ohio was established in October of 2020, and is a specialized coronary microvascular and vasomotor dysfunction (CMVD) program.

Methods:

The TCH-WHC focuses its efforts across five pillars: patient care, research, education, community outreach and advocacy, and grants and philanthropy. These areas, centered around providing specalized CMVD care and treatment have allowed for substantial growth.

Results:

From October 2020-December 2023, TCH-WHC saw a total of 3219 patients, 42% of which were apart of the CMVD program. Since establishment, patient volume has consistently increased year over year.

Conclusion:

The CMVD program at TCH-WHC is one of the fastest growing in the U. S. and is nationally recognized for specialized clinical care, diagnostics, and research. The goal of this review is to provide an overview of the TCH-WHC structure that allows for the establishment and growth of a CMVD program and to outline core activities supporting the TCH-WHC approach.

Keywords: ANOCA, coronary microvascular and vasomotor dysfunction, INOCA, MINOCA, sex differences, Women's Heart Center

1 ∣. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide and is responsible for approximately 30% of all deaths in women [1]. The steady increase in cardiovascular mortality in women during the late 1990s, combined with the initiation of large clinical trials (e.g. Women's Ischemic Syndrome Evaluation [WISE] and Women's Health Study [NHS]), fueled increased attention on women's cardiovascular care and spurred increased advocacy and efforts to promote sex-specific research and specialized centers of women's cardiovascular care. Women's Heart Centers (WHC) are comprehensive, multidisciplinary care centers designed to close the existing gap in women's cardiovascular care through specialized programs that range from prevention, to disease-specific programs on cardiovascular diseases that disproportionally affect women such as angina/ischemia with nonobstructive coronary artery (ANOCA/INOCA), coronary microvascular and vasomotor dysfunction (CMVD), myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA), and spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). This can also include multidisciplinary programs such as cardio-obstetrics, cardio-menopause, cardio-oncology, cardio-rheumatology, and cardio-metabolic. In addition to specialized care for women, WHCs provide the ideal setting for research, education, community outreach, and advocacy [2].

ANOCA/INOCA affects nearly 4 million individuals in the United States, 70% of which of are women [3]. CMVD is the primary mechanism responsible for ANOCA/INOCA but is increasingly recognized in a wide range of CVDs including MINOCA, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), cardiomyopathies, refractory angina post-revascularization in patients with history of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD), and acute coronary syndrome [4]. ANOCA is defined as anginal symptoms and less than 50% stenosis or absence of significant flow limiting stenosis by fractional flow reserve (FFR > 0.81) in any major epicardial artery. INOCA is defined similarly but these patients additionally have presence of ischemia on stress testing (positive stress test). CMVD is present in up to 80% of ANOCA/INOCA patients undergoing invasive coronary functional testing (ICFT) [5]. CMVD continues to be under-diagnosed and under-treated despite the nearly threefold increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality [6]. ANOCA/INOCA has devastating effects on quality of life and can be extremely costly [7]. In fact, morbidity and mortality costs in ANOCA patients exceeds those of patients with obstructive CAD at $21 billion dollars annually [8]. Despite this, treatment options are limited, and sex-specific research is lacking. Given the female predominance of ANOCA/INOCA and MINOCA, a WHC provides an ideal setting to build a successful CMVD program.

The Women's Heart Center at The Christ Hospital Heart and Vascular Institute (TCH-WHC) in Cincinnati, Ohio was established in October of 2020. The TCH-WHC CMVD program is one of the fastest growing treatment centers in the United States (U.S.) and is nationally recognized for its specialized clinical care, diagnostics and research. The TCH-WHC was founded on five key pillars including specialized clinical programs, cutting edge research, education, community outreach and advocacy, and fundraising through grants and philanthropy (Figure 1). Execution of activities across the pillars combined with the clinical expertize and institutional resources have allowed for rapid growth of the TCH-WHC and the CMVD program. The goals of this manuscript are to provide an overview of the TCH-WHC structure that allows for the establishment and growth of a CMVD program and to outline core activities supporting the TCH-WHC approach. The simultaneous publication “Utilizing Invasive Coronary Functional Testing in a Coronary Microvascular and Vasomotor Dysfunction Program: Methods and Considerations” will provide an overview of when to refer a patient for ICFT, specific ICFT protocols used, and the role of ICFT in the diagnosis and treatment of CMVD.

FIGURE 1 ∣.

Overview of TCH-WHC Pillars, including the vision and mission.

1.1 ∣. Foundation: Leadership, Clinical Care Team, and Staff Infrastructure

The clinical and leadership team is fundamental to the success of a CMVD program and WHC. Institutional support is critical to the success of the program, although specifics will depend on the institution type (e.g. academic, private practice, community hospital) and can be supplemented through fundraising initiatives (see fundraising section). Here, we highlight key leadership and infrastructure positions that were needed to build a successful CMVD program within TCH-WHC.

At the core of this structure is the leadership and oversight of the clinical care team and WHC pillars by the medical director. The medical director should be a board-certified cardiologist with clinical expertize in women's cardiovascular care, comprehensive approach to CMVD, research, education, community engagement, advocacy, and fundraising. The medical director oversees every aspect of TCH-WHC. Dedicated time for administrative responsibilities, research, and education initiatives is necessary to support this role.

The number of cardiologists that are needed to support a WHC is dependent on volume and number of specialized clinical programs developed, each often needing a physician champion. Partnerships with general cardiologists, advanced imaging cardiologist and radiologists, and interventional cardiologist with expertize in ICFT are critical to build and support a specialty CMVD program. An interventional cardiologist with dedicated time per week to perform ICFT is essential with a high-volume program. Beyond interventional cardiology needs, a strong cardiovascular imaging program equipped with advanced imaging capability is essential. Advanced practice providers (APP's) dedicated to the CMVD program are a critical component and essential for the clinical care team to manage complex CMVD patients, the majority of which often need monthly follow up clinic visits for recurrent anginal symptoms and uptitration of antianginal treatments.

Support staff for the clinical team includes registered nurses, nurse navigator, medical assistants, and schedulers dedicated to the WHC. All clinical staff is supervised by a practice manager who oversees the administrative duties of the practice and facilitates the integration of clinical specialties and services. Nurses play a critical role; they triage patients, manage chest pain calls, titrate antianginals over the phone based on protocols, provide patient education on upcoming procedures, and enhance the flow of clinic. All APP and staff are trained in the diagnosis and care needs for CMVD program patients specialized to their scope of practice as directed by the medical director (see education).

In addition to specialized clinical care programs, the TCH-WHC has developed the infrastructure necessary to support research, education, community outreach, and fundraising which are fundamental to the mission. The four nonclinical pillars are overseen by a WHC program manager. The program manager should have expertize in program management, clinical research, and a strong administrative background. The program manager is a full-time employee, working closely with the medical director, and supporting program and research coordinators to execute initiatives of the WHC. Under the training and guidance of the program manager, program and research coordinators can specialize across pillars. Program and research coordinators perform a variety of roles in TCH-WHC including (but not limited to): management of the WHC registry and related research, scientific writing, training and oversight of student interns and trainees, community outreach, and educational programming. This model has allowed for expansion of larger TCH-WHC initiatives and fostered a positive and highly productive working environment.

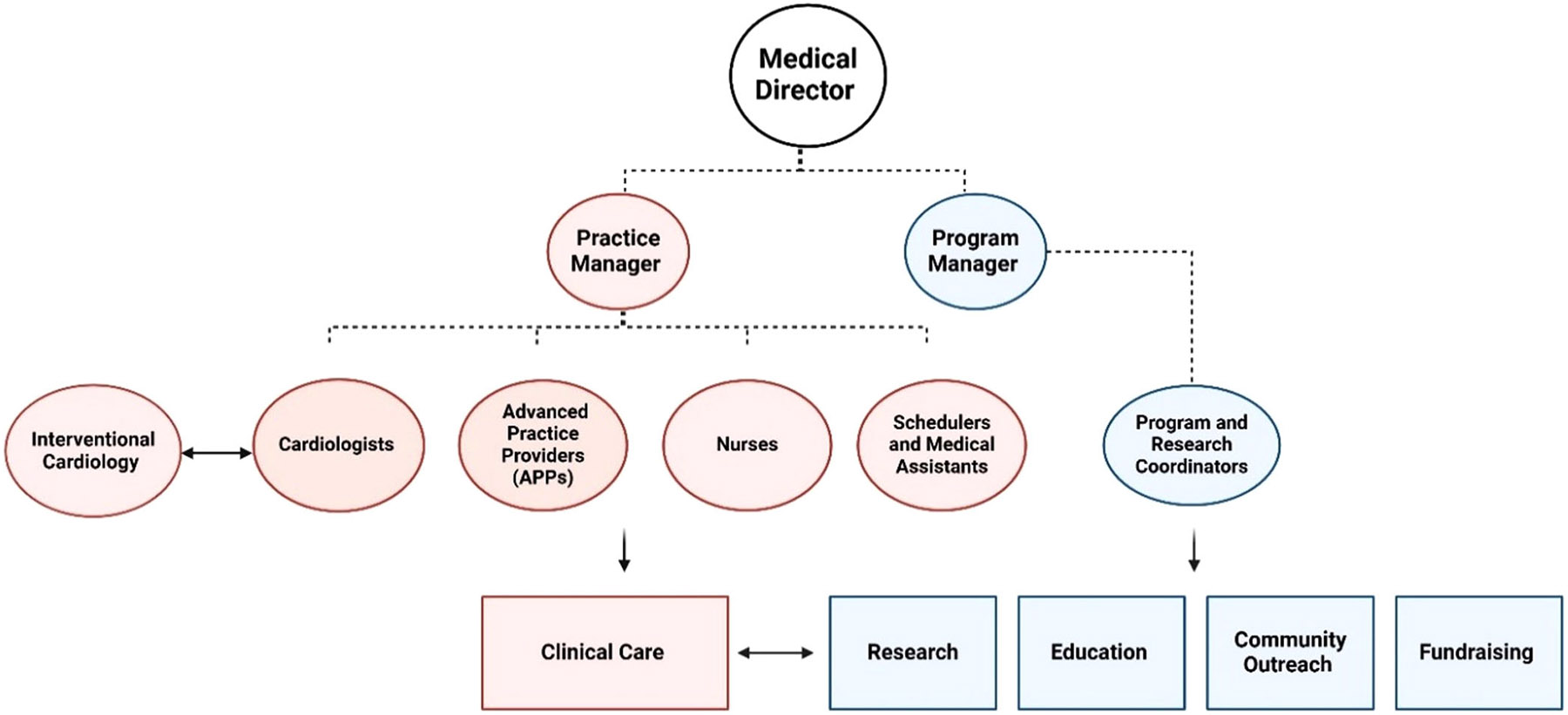

1.2 ∣. TCH-WHC Leadership, Clinical Care Team, and Staff Infrastructure

A simplified organizational chart of the TCH-WHC can be found in Figure 2. The THC-WHC CMVD program was established with a dedicated clinical cardiologist with advanced training in CMVD who also served as the founding medical director, an interventional cardiologist with extensive experience in CMVD and ICFT, and a partnership with the advanced imaging program. By the second year a part-time general cardiologist joined and by year four a full-time general cardiologist with interest in prevention joined the WHC team. A dedicated APP was hired at the inception of the program, and within the first year a second APP was hired to allow for the rapid patient growth. The THC-WHC clinical staff at its onset included a dedicated scheduler, a medical assistant, and a nurse; and within 4 years, the clinical staff has expanded to three dedicated schedulers, three medical assistants, three nurses and a nurse navigator. The non-clinical team was started with the WHC program manager, and within four years the staff has expanded to four program/research coordinators.

FIGURE 2 ∣.

A simplified organization chart for the TCH-WHC Team, does not reflect collaboration with outside departments or nonfull time staff members.

1.3 ∣. CMVD Program at a Glance

The CMVD program was developed to provide appropriate diagnostics and optimal treatment paradigms for patients with CMVD across a multitude of diagnoses including but not limited to ANOCA/INOCA, MINOCA, history of obstructive CAD with refractory angina, HFpEF, post-COVID syndrome, and myocardial bridging. It is important to note the critical role of the CMVD program in a Comprehensive Angina Relief (CARE) program given that a significant proportion of patients with history of obstructive CAD have refractory angina post revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) in large part due to underlying CMVD. At TCH the CMVD program is an integral part of the CARE program.

Among ANOCA/INOCA patients testing for CMVD has a 2A indication in the 2021 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Chest Pain guidelines [9]. In the 2024 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the Management of Chronic Coronary Syndromes assessment of CMVD with ICFT has a 1B indication and with noninvasive modalities it has a 2B indication [10]. CMVD encompasses endothelial-independent coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD), endothelial-dependent CMD, microvascular vasospastic angina (VSA), and epicardial VSA [5]. Endothelial-independent CMD can be assessed noninvasively through measure of myocardial blood flow reserve during hyperemia with doppler assessment of left anterior descending artery (LAD) on stress echocardiography, and the gold-standard stress positron emission tomography (PET); and myocardial perfusion reserve with stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) perfusion imaging [11]. ICFT with acetylcholine challenge at varying doses is the only testing modality available for assessment of endothelial-dependent CMD, microvascular VSA, and epicardial VSA; in addition to endothelial-independent CMD assessment utilizing adenosine and measurement of coronary flow reserve (CFR) [12]. The ICFT procedure is performed predominantly through two methods: Doppler technique (ComboWire XT or Flowire; Philips Volcano Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA) or the pressure-temperature sensor guidewire thermodilution method (PressureWire X; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) [13]. Specifics on ICFT techniques, interpretation of results, and CMVD treatment based on endotypes are described in detail in simultaneous publication in Catherization and Cardiovascular Interventions titled “Utilizing Invasive Coronary Functional Testing in a Coronary Microvascular and Vasomotor Dysfunction Program: Methods and Considerations.”

Additionally, we developed an inpatient MINOCA program as part of our comprehensive CMVD program. A third of women presenting with a myocardial infarction have MINOCA [14]. MINOCA can be due to ischemic causes including coronary artery plaque disruption, coronary vasospasm, coronary microvascular dysfunction, and SCAD. Myocardial infarction can also be due to nonischemic causes, commonly referred to as MINOCA-Mimicker, including Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, and nonischemic cardiomyopathy [15]. Despite the absence of obstructive CAD, patients with MINOCA experience similar or higher risk of mortality as compared to patients with obstructive CAD [16, 17]. Therefore, understanding the underlying cause of the MINOCA event is imperative for appropriate treatment. Important tools in the diagnosis of MINOCA include intravascular imaging (intravascular ultrasound [IVUS] and optimal coherence tomography [OCT]), CMRI, and in cases suspicious for coronary vasospasm, ICFT with acetylcholine testing is recommended [18]. CMRI is recommend within 7 days of an event in all MINOCA cases where a diagnosis is uncertain [19]. To ensure that patients with MINOCA receive appropriate and timely CMRI, a close collaboration with advanced cardiovascular imaging program was essential. The electronic medical record (EMR) was leveraged to create a specific order-set that is initiated in patients presenting with myocardial infarction after angiography confirms MINOCA and includes serial troponin assessments until peak, CMRI to be performed inpatient or outpatient within 7 days of event, and expediated postdischarge follow-up with the CMVD program.

In addition to pharmicological treatments, non-medical options have contributed to the success of our program and are available to our CMVD patients. Our CMVD program is equipped with noninvasive therapies including enhanced external counter pulsation (EECP) for the management of patients with refractory angina due to CMVD [20]. Further, the TCH-CMVD program works in close collaboration with cardiac rehabilitation services to provide a specialized cardiac rehabilitation program for CMVD patients.

1.4 ∣. Patient Acquisition Focused on CMVD Patients and Marketing

A combination of educational efforts, collaboration with other departments, and community engagement directly supported the growth of the CMVD program at TCH-WHC. A sustained effort is made to educate healthcare providers on ANOCA/INOCA and MINOCA across departments and scopes of practice (see Education section) and the EMR system is leveraged to facilitate patient referrals. TCH-WHC worked with marketing team members to build a fully functional website which outlines our areas of expertize and includes patient education materials related to CMVD. Further, marketing campaigns and educational events are important tools to share stories of patients with CMVD. Importantly, TCH-WHC allows for self-referrals from patients meeting criteria for ANOCA/INOCA and MINOCA.

1.5 ∣. Growth of CMVD Program at TCH-WHC

From the initiation of TCH-WHC in October of 2020 through July 2024, the TCH-WHC has seen a total of 3219 patients. Reflecting 3 full calendar years, annual totals were 745 patients in 2021, 895 patients in 2022 and 959 patients in 2023 (Figure 3); this reflects consistent year-over-year growth, in 2022 TCH-WHC experienced a 20% year-over-year growth over 2021 and in 2023 there was an additional 7% increase in total patient volume over 2022. The CMVD program accounts for 42% (N = 1368) of total patients seen at the TCH-WHC from October 2020 through July 2024; and a total of 422 ICFT procedures were performed utilizing both doppler and thermodilution methods. The TCH-CMVD program also significantly increased CCTA and CMRI volumes for noninvasive assessment of CMD. Of note, the totals were calculated based on patient information in the TCH-WHC registry and may not reflect a complete count of patients seen by all providers, graphed data in Figure 3 reflects three complete calendar years.

FIGURE 3 ∣.

Total patients seen at the TCH-WHC by year from December of 2020 through December of 2023.

2 ∣. Research Pillar

WHCs provide the ideal setting for clinical research which plays a vital role in closing the gap in sex-differences in cardiovascular care and outcomes. Particularly important in the field of CMVD where treatment options are limited. Investments into research infrastructure has allowed for expansion of both the clinical and nonclinical pillars and provide the basis for future CMVD treatment development.

2.1 ∣. TCH-WHC Registry: Integration of Research Into Clinical Care

An investigator-initiated registry was created inclusive of all patients to close knowledge gaps that remain in the pathogenesis and management of CVDs more common in women, long-term outcomes, and facilitate future research. The registry is housed within a REDCap database and includes demographics including social determinants of health, medical history, ICFT, cardiac imaging, clinical outcomes, and patient reported outcomes via validated questionnaires. The EMR system was leveraged to create note templates that ensure important data is consistently collected. Also, to access change over time in symptoms, CCS class and NYHA class are collected on all patients at each visit. TCH-WHC partnered with the Carl and Edyth Lindner Center for Research and Education summer internship program, and the University of Cincinnati to facilitate recruitment of highly motivated students and trainees to support data entry.

2.2 ∣. Clinical Trials and Partnership With the Carl and Edyth Lindner Center for Research

In partnership with the Carl and Edyth Lindner Center for Research and Education, the WHC has created a diverse and expansive portfolio of sex-specific cardiovascular research projects. Funding mechanisms for research are also diverse including industry sponsors, federal and foundation grants, and divisionally funded investigator-initiated research. Given the high volume of the CMVD program, the TCH-WHC has been a top enroller in pivotal trials for CMVD including a placebo-controlled trial to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of intracoronary delivery of autologous CD34+ cells (FREEDOM trial), the Women's Ischemia Trial to Reduce Events in Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (WARRIOR), Evaluation of CMD Using Magnetocardiography (MICRO1.0) and the Coronary Sinus Reducer for ANOCA patients (COSIRA-2 Registry). TCH-WHC's active involvement in clinical research naturally enhances inclusion of women in these trials which is a key to eliminating gaps in cardiovascular care. The partnership between the Carl and Edyth Lindner Center for Research and Education and the WHC has allowed for investigator-initiated research in CMVD, including a CMVD biorepository that includes blood collection on all patients who consent at time of ICFT. Clinical research has bolstered the national recognition of the TCH-WHC, the CMVD program, and promoted ongoing research collaborations with external investigators and industry partners.

3 ∣. Education and Community Outreach Pillars

Education across multiple levels including healthcare providers and support staff, patients, and the larger community is essential for the success of a WHC specializing in CMVD. Education across tiers is ongoing and recurs on an annual basis.

3.1 ∣. Tiered Approach to Provider Education

The TCH-WHC utilized a tiered approach to CMVD education, directly facilitated and conducted by the medical director. Tier 1 encompassed all members of the TCH-WHC patient care team including cardiologists, APPs, nurses, medical assistants, schedulers, and the clinical research and program team. This training focused on core components of CMVD and was specialized for each scope of practice. This training was accomplished through group meetings and one-on-one trainings led by the medical director, with support from the practice and program managers. Tier 1 also included educating Heart and Vascular Institute providers including cardiologists, trainees, APPs, and support staff which encompassed inpatient and outpatient nurses, imaging and catheterization laboratory technicians to ensure all patients with CMVD would be appropriately recognized and referred for evaluation. Tier 1 education is particularly important in the early stage of a CMVD program and remains a critical component for new staff orientation and annual continuing education.

Tier 2 focused on referral providers including primary care and emergency room providers. Provider education was accomplished through grand rounds, inter- and intradepartmental meetings, targeted lectures, and lunch and learns. This facilitated a deeper understanding of sex-specific CVD presentation and fostered relationships that support appropriate referrals to the CMVD program.

The aim of Tier 3 was to educate providers outside of the institution and increase awareness of CMVD locally and on the national level. The annual women's cardiovascular symposium, the first of its kind, was initiated to bring together national experts to Cincinnati to educate healthcare providers on sex-differences in cardiovascular care. The symposium was started in 2022 and occurs annually, attracting more than 250 providers, students, and industry partners from across the country. A Tri-state area advanced practitioner educational series was also established within Tier 3, including a lecture on how to recognize ANOCA/INOCA patients. Education of the broader national scientific community is directly supported by grand round presentations, original research, review articles, and presentations on CMVD in national and international meetings.

Tier 4 focused on trainee education to increase the pipeline of cardiologists and providers well versed in sex-specific cardiovascular care. This training has occurred across all education levels from high school through cardiology fellows from multiple institutions. To further enhance training focused on the cardiovascular care of women, the TCH-WHC will be starting a 1-year, nonaccredited women's cardiovascular fellowship in year 5.

3.2 ∣. Approach to Patient Education

As discussed above, patient education through marketing is critical for patient recruitment. To facilitate enhanced understanding of CMVD, patient materials were developed in both print and electronic format. Patient handouts are available in the clinic setting where one-on-one patient education begins. Electronic versions of all patient-facing educational materials are also available for download from the TCH-WHC website. Additionally, a Facebook support group for the TCH-WHC was created which fosters a sense of community with information and educational content. Through the development of patient education materials, and by partnering with patients and supporting them with opportunities to serve as patient advocates, we have directly facilitated broader opportunities for community engagement and outreach.

3.3 ∣. Patient Education Through Community Outreach

Partnering with our community expanded the reach and impact of the TCH-WHC to help reduce disparities experienced by marginalized groups disproportionately affected by CVD. For example, TCH-WHC partners with the local chapter of the American Heart Association to participate in national, educational heart awareness campaigns, and fundraising events. Further, TCH-WHC partners with local advocacy groups for marginalized communities to host educational and screening events. Grass root efforts were initiated to meet women where they are regardless of age, race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status to provide cardiovascular risk education, awareness, and prevention. The WHC led a one-year campaign initiative in collaboration with multiple community partners focused on increasing awareness of CVD in Hispanic/Latina women. This work has resulted in engagement with local and national media.

4 ∣. Grants and Philanthropy

Fundraising in support of TCH-WHC has directly allowed for the expansion across all TCH-WHC pillars. Direct fundraising in support of TCH-WHC mission is facilitated through the TCH Foundation. Foundation and corporate grants help fund investigator-initiated research, community outreach, and education efforts; in addition to providing financial assistance for patient care. The financial assistance program has increased access to care and provided preventative services for underserved and under-resourced patient populations. TCH-WHC has also received research support via grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American College of Cardiology, and industry partnerships. TCH-WHC creates a quarterly newsletter for patients and donors that summarizes the work accomplished by the WHC as it relates to new research in women's cardiovascular health, education, community outreach, and philanthropy initiatives.

5 ∣. Conclusions

The TCH-WHC was established on five fundamental pillars including education, research, clinical care, community outreach, and grants and philanthropy. This has directly supported the growth of the TCH-WHC and its specialty care program in CMVD. While TCH-WHC strives to close gaps in women's cardiovascular care, additional WHC specializing in CMVD are needed to advance our understanding of these conditions and improve clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients of TCH-WHC, our generous donors and community partners. Your support makes our mission possible. This work was supported by the Accreditation Foundation Committee (“AFC”) of the American College of Cardiology Foundation (“ACCF”) through a Quality Initiative/Process Improvement Grant awarded to Odayme Quesada, MD, MHS and The Women's Heart Center, Heart & Vascular Institute, The Christ Hospital Health Network. K23HL151867 (O.Q.).

Abbreviations:

- ANOCA

angina with nonobstructive coronary artery disease

- APP

advanced practice provider

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CCS

Canadian Cardiovascular Society

- CMD

coronary microvascular dysfunction

- CMRI

cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

- CMVD

coronary microvascular and vasomotor dysfunction

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- EMR

electronic medical record

- ICFT

invasive coronary functional testing

- INOCA

ischemia with nonobstructive coronary artery disease

- MINOCA

myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary artery disease

- SCAD

spontaneous coronary artery dissection

- TCH-WHC

The Women's Heart Center at The Christ Hospital Heart and Vascular Institute

- VSA

vasospastic angina

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. , “Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association,” Circulation 145 (2022): e153–e639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulati M, Hendry C, Parapid B, and Mulvagh SL, “Why We Need Specialised Centres for Women's Hearts: Changing the Face of Cardiovascular Care for Women,” European Cardiology Review 16 (2021): e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, Walsh MN, et al. , “Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (INOCA): Developing Evidence-Based Therapies and Research Agenda for the Next Decade,” Circulation 135 (2017): 1075–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Buono MG, Montone RA, Camilli M, et al. , “Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Across the Spectrum of Cardiovascular Diseases,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 78 (2021): 1352–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford TJ, Yii E, Sidik N, et al. , “Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: Prevalence and Correlates of Coronary Vasomotion Disorders,” Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions 12 (2019): e008126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelshiker MA, Seligman H, Howard JP, et al. , “Coronary Flow Reserveflow Reserve and Cardiovascular Outcomes: Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis,” European Heart Journal 43 (2022): 1582–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmad A, Corban MT, Moriarty JP, et al. , “Coronary Reactivity Assessment is Associated With Lower Health Care-Associated Costs in Patients Presenting With Angina and Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease,” Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions 16 (2023): e012387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw LJ, Merz CNB, Pepine CJ, et al. , “The Economic Burden of Angina in Women With Suspected Ischemic Heart Disease: Results From the National Institutes of Health—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute—Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation,” Circulation 114 (2006): 894–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. , “2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/ CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines,” Circulation 144 (2021): e368–e454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, et al. , “2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Coronary Syndromes,” European Heart Journal 45 (2024): 3415–3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taqueti VR and Di Carli MF, “Coronary Microvascular Disease Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Options,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 72 (2018): 2625–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuels BA, Shah SM, Widmer RJ, et al. , “Comprehensive Management of Anoca, Part 1—Definition, Patient Population, and Diagnosis,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 82 (2023): 1245–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demir OM, Boerhout CKM, de Waard GA, et al. , “Comparison of Doppler Flow Velocity and Thermodilution Derived Indexes of Coronary Physiology,” JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 15 (2022): 1060–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marzilli M, Merz CNB, Boden WE, et al. , “Obstructive Coronary Atherosclerosis and Ischemic Heart Disease: An Elusive Link!,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 60 (2012): 951–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamis-Holland JE, Jneid H, Reynolds HR, et al. , “Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Myocardial Infarction in the Absence of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association,” Circulation. 139 (2019): 891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choo EH, Chang K, Lee KY, et al. , “Prognosis and Predictors of Mortality in Patients Suffering Myocardial Infarction With Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries,” Journal of the American Heart Association 8 (2019): e011990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quesada O, Yildiz M, Henry TD, et al. , “Mortality in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries and Mimickers,” JAMA Network Open 6 (2023): e2343402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montone RA, Niccoli G, Fracassi F, et al. , “Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries: Safety and Prognostic Relevance of Invasive Coronary Provocative Tests,” European Heart Journal 39 (2018): 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agewall S, Beltrame JF, Reynolds HR, et al. , “ESC Working Group Position Paper on Myocardial Infarction With Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries,” European Heart Journal 38 (2017): 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashokprabhu ND, Fox J, Henry TD, et al. , “Enhanced External Counterpulsation for the Treatment of Angina With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease,” The American Journal of Cardiology 211 (2024): 89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]