Abstract

Purpose

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a highly prevalent psychiatric condition with complex and heterogeneous biological underpinnings. Lipid dysregulation has emerged as a potential contributor to MDD pathophysiology. However, comprehensive lipidomic profiling studies in Japanese individuals remain limited. This study aimed to investigate serum lipidomic alterations in Japanese patients with MDD and explore the potential associations with depression severity.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a real-world observational study including 30 Japanese patients with MDD and 30 healthy controls. Depression severity was assessed using the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Lipidomic analysis identified 344 lipid peaks from serum samples. Multivariate and univariate statistical analyses were employed to identify differentially expressed lipids and their correlations with clinical symptoms.

Results

Thirty lipids were found to differ significantly between groups, with 7 elevated and 23 reduced in the MDD cohort. Pathway enrichment analysis highlighted disruptions in lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), N-acylethanolamines, and fatty acylcarnitines. Notably, levels of LPC (20:3), platelet-activating factor (20:5), and platelet-activating factor (18:3) were negatively correlated with depression severity, suggesting a potential link to mood regulation.

Conclusion

The pronounced enrichment changes observed in LPC and LPE—lipid species involved in membrane remodeling and cellular signal transduction—are consistent with previous findings. However, the observed negative correlations with psychiatric symptom severity were contrary to prior expectations. These results underscore the importance of interpreting lipidomic data in the context of specific population characteristics, methodological frameworks, and clinical settings. They suggest potentially meaningful metabolic alterations associated with MDD and provide a foundation for future longitudinal and mechanistic investigations.

Keywords: lipidome, lipidomics, lysophosphatidylcholine, major depressive disorder, platelet-activating factor

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common disorder worldwide, with an increasing annual prevalence. Nearly one in five individuals experience at least one episode during their lifetime, resulting in a large social and economic burden.1,2 The complex biochemical network involved in the pathophysiology of MDD remains unclear, and as such, specific biochemical markers that would enable more accurate diagnosis and prognosis remain unknown.3,4 However, the involvement of lipids in this disease has been increasingly emphasized.5

Cellular lipid metabolism is a complex network process involving dozens of enzymes, multiple organelles, and over 1000 lipid types,6 which has limited its analysis in the past. However, recent advancements in research on disease pathophysiology and the advent of the omics approach—which is a comprehensive analytical technique—have significantly contributed to the elucidation of the fundamentals of several diseases and the discovery of specific biomarkers, leading to many breakthroughs.7,8 Lipidomics facilitates the identification of disruptions in the entire lipid profile (lipidome) of patients with MDD.9,10

Lipids comprise major classes, such as cholesterol, fatty acids, triacylglycerols, glycerophospholipids, glycosphingolipids, and sphingomyelin, as well as physiological processes, such as energy metabolism and neuroendocrine function. Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) and lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) have been widely studied as pro-inflammatory mediators, promoting monocyte recruitment and cytokine production while also playing a role in modulating membrane curvature and inflammation.9,11,12 Meanwhile, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), two major omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids commonly found in fish oils, exert anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective functions.13–15 These fatty acids influence membrane fluidity, receptor function, and synaptic transmission. Decreased levels of DHA and EPA can be associated with MDD.16,17 In addition, acylethanolamines (eg, anandamide, AEA) belong to the endocannabinoid family and play important roles in synaptic plasticity, stress response regulation, and neurotransmitter release through cannabinoid receptor-1 signaling.18 AEA can exhibit both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects depending on receptor context and physiological state.19

The brain is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids and is a major target of damage caused by reactive oxygen species produced by chronic stress.20,21 Inflammation and oxidation often affect brain lipid profiles and membrane lipid compositions and could affect membrane structure, function, and characteristics. As lipids can easily cross the blood-brain barrier, disruptions in brain lipid profiling may also be reflected in the blood.20 Given that inflammation is an important biological process related to MDD onset,22 changes in the characteristics of lipids that promote inflammation or have anti-inflammatory effects in the brain can possibly be measured in the blood.20,23

Lipidomic studies have already begun to identify lipid classes and specific species that differentiate patients with MDD from healthy individuals. For instance, Liu et al reported that in patients with MDD, the total levels of lipid classes such as LPC, LPE, phosphatidylcholines, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, diacylglycerol, and triacylglycerol increased while some sphingomyelin species decreased.24 Chan et al investigated the lipid profiles of patients with coronary artery disease and reported that 10 phospholipid types exhibited excellent discriminative power (84%) in distinguishing patients with coronary artery disease who had depressive symptoms from those who did not.25

While these findings underscore the potential of lipidomics for psychiatric research, the field is still in its developing stages. Moreover, many of the related studies were conducted in Western populations; however, accumulating evidence suggests that lipidomic profiles can vary substantially across ethnicities due to differences in genetic background, dietary habits, and environmental exposure.26,27 Therefore, investigating lipidomic alterations in diverse ethnic groups is important for improving the generalizability of lipidomic biomarkers in MDD research. Japan presents a unique context for such investigation, given the population’s distinct nutritional profiles (eg, high fish and omega-3 fatty acid intake), relatively low obesity rates, longevity, and potential cultural and genetic differences in stress response.28–32 However, comprehensive lipidomic studies focusing on Japanese patients with MDD are scarce. Addressing this gap is essential for uncovering population-specific pathophysiological mechanisms and identifying more universally applicable or tailored biomarkers.

This study conducted a serum lipidomic analysis of real-world Japanese patients with MDD and a healthy control (HC) group to investigate lipidome alterations associated with depressive symptoms. We analyzed the data from three perspectives: individual lipid species difference, pathway enrichment as lipid class, and correlation with depressive symptom severity.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (approval no. UOEHCRB21-164). Written and verbal consent were obtained from all participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Design and Participants

This observational study, conducted in a real-world clinical setting, examined participants’ mental state and blood data at the time of enrollment. A total of 60 individuals were included, comprising 30 patients with MDD and 30 HC. Patients with MDD were recruited from outpatient psychiatric clinics and diagnosed by psychiatrists according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Inclusion criteria for the MDD group included aged 18–65 years, a confirmed diagnosis of MDD without comorbid psychiatric disorders, and either no current pharmacological treatment or stable use of antidepressants. We aimed to recruit participants in generally good medical condition. When comorbid medical conditions were present, only those who were medically well-controlled and clinically stable at the time of blood sampling and clinical assessment (eg, controlled hypertension or diabetes) were included. Patients with severe or poorly managed medical illnesses were excluded. Healthy controls were recruited through the medical staff at our university. Through structured interviews and health screenings, they were confirmed to have no history of psychiatric or major medical disorders. We tried to match the MDD and HC groups as closely as possible in terms of three basic demographic data: age, sex, and body mass index (BMI).

Clinical Assessment and Blood Sampling

Depression severity was evaluated using the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). The MADRS is often used in clinical trials to select patients and assess treatment efficacy. Structured interview guides have been found to improve the reliability of scales.33 There was no restriction on the time of blood collection; however, a 30 min resting period was set before blood collection. Patient blood samples were collected in regular blood collection tubes at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health. The serum was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 20 min and stored at −80°C in silicon-coated tubes until analysis.

Lipidomics Analysis

Lipidomics analysis (to measure the lipidome) was conducted at Human Metabolome Technologies (HMT, Tsuruoka City, Japan).

As a pretreatment, 100 µL of serum was mixed with 300 µL of 0.1% formic acid in methanol containing internal standards (H3304-1002, HMT, Inc., Tsuruoka, Yamagata, Japan) and centrifuged at 9100 × g and 4°C for 10 min. Then, 250 µL of the supernatant was mixed with 550 µL of 0.1% formic acid and loaded into a solid phase extraction column (MonoSpinC18, 5010–2170, GL Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The analytes in the SPE column were purified with 0.1% formic acid, followed by 0.1% formic acid in 25% methanol, and subsequently eluted with 200 µL of 0.1% formic acid in methanol.

Lipidomic analysis was conducted according to HMT’s Mediator Scan package using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). LC-MS/MS analysis was carried out using an Agilent 1260 InfinityIIand Agilent 1290 InfinityIIHigh Speed Pump equipped with AB Sciex QTRAP 5500 (AB Sciex Pte. Ltd., Framingham, MA, USA). The multiple reaction monitoring mode was used to detect signals of each metabolite according to HMT’s metabolite database. MRM ion chromatograms were extracted using MultiQuant automatic integration software (AB Sciex) to obtain peak area information. The peak area of each metabolite was normalized to that of the internal standard and sample volume to obtain the relative levels of each metabolite.

Analysis was conducted on substances registered in the HMT Metabolite Library. The detected peaks were classified into fatty acids, acylcarnitines (AC), endocannabinoid (AEA), platelet-activating factor (PAF), lysoPAF, arachidonic acid metabolites, eicosapentaenoic acid metabolites, docosahexaenoic acid metabolites, steroid, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), LPC, LPE, sphinganine, sphingosine, lysophosphatidylglycerol (LPG), lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI), lysophosphatidylserine (LPS), shinganine-1P, shingosine-1P, glucosylceramide, lactosylceramide, seramide, and gangliosides based on the candidate compounds. Consequently, 344 peaks were detected and assigned candidate compound names.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Enrichment analysis is a statistical method for evaluating whether lipid molecules that show significant variation between groups are biased toward specific lipid classes or functional categories. The lipids that showed significant differences in the actual observations are compared with the expected values obtained by randomly selecting lipids based on the overall background data, and it is determined whether the corresponding class is statistically significantly enriched. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0.34

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 17 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). We used Welch’s t-test for the between-group differences test. In addition, we performed an orthogonal partial least-squares-DA (OPLS-DA) analysis35 using the group as the teacher data and calculated the variable importance for prediction (VIP) score.36 Using Welch’s t-test and VIP scores, we identified lipidomes that differed between patients with MDD and HC. We assigned library IDs based on PubChem37 and performed a pathway impact analysis of lipids using MetaboAnalyst. The identified lipidomes were examined for their association with psychiatric symptoms in patients with MDD using regression analysis. The adequacy of the regression analysis model was assessed based on the normality of the residual histogram.

All data were expressed as median and interquartile range. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant with a two-sided test. In the comprehensive lipidomics analysis, to control for multiple testing, we calculated the q-value—a multiple testing correction value based on the Benjamin–Hechberg method—38 for the p-value. A q-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Finally, we defined metabolites that showed a significant difference between patients with MDD and HC in the lipidomics analysis as those that satisfied the criteria of a q-value < 0.05 and a VIP score of > 1.5.36 Similarly, in lipid enrichment analysis, we calculated p-values and q-values.

Results

Participants and Demographic Data

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the MDD and HC groups. Those in the MDD group were slightly older than those in the HC group (median: 47 vs 37 years), although the interquartile ranges overlapped. The proportion of sex was similar across groups (male: 46.6% in MDD vs 53.3% in HC), while BMI was slightly higher in the MDD group (24.2 vs 23.1 kg/m²). Educational background differed: 83.3% of HC participants had graduated from university or graduate school, whereas only 33.3% of MDD participants had. By contrast, more MDD patients had only completed high school or junior college. Smoking was more prevalent among MDD patients (26.6%) compared with HC (6.6%), and regular exercise habits were less common (23.3% vs 36.6%). Among MDD participants, the median disease duration was 4 years, and the median number of depressive episodes was 2. The MADRS score median was 24.5, indicating moderate depressive severity. Most patients with MDD (93%) were under pharmacological treatment, with a median imipramine equivalent dose of 150 mg.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data

| HC (n=30) | MDD (n=30) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||

| Age, year | 37 (35–51) | 47 (36.2–53) |

| Sex, male | 53.3% (16) | 46.6% (14) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.1 (21.5–24.4) | 24.2 (21.8–26.1) |

| Education | ||

| Junior high school | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| High school | 3.33% (1) | 33.3% (10) |

| Junior college | 13.3% (4) | 33.3% (10) |

| University/graduate School | 83.3% (25) | 33.3% (10) |

| Smoking | 6.6% (2) | 26.6% (8) |

| Exercise habit | 36.6% (11) | 23.3% (7) |

| Comorbid disease | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 0% (0) | 10% (3) |

| High blood pressure | 0% (0) | 23.3% (7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0% (0) | 13.3% (4) |

| Clinical data | ||

| Disease period, year | 4 (1–8) | |

| Times of episode, times | 2 (1–2) | |

| MADRS, points | 24.5 (9–31.5) | |

| Psychiatric medicine | 93% (28) | |

| Imipramine equivalent | 150 (81.2–225) |

Note: Data are expressed as median and interquartile range and percentages.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MDD, major depressive disorder; HC, healthy control; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; n, number.

Lipidomics Analysis

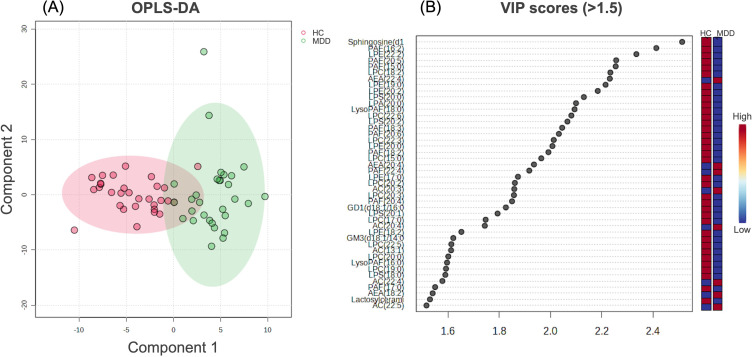

From the 344 lipids identified by lipidomics analysis, we identified 30 lipids that differed between the MDD and HC groups using Welch’s t-test, OPLS-DA analysis, and VIP score (q < 0.05, VIP score > 1.5). Among them, the levels of seven types of lipids—AEA (22:4), AEA (20:4), AEA (18:2), AC (20:3), AC (20:4), AC (22:5), and AC (22:4)—were higher in the MDD than in the HC group, while the remaining 23 were higher in the HC than in the MDD group (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Lipidomics Analysis

| Lipid name | HC | MDD | p-value | q-value | VIP Score | Regulation (Compared with HC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEA (22:4) | 0.000013 (9.40e-06–0.000015) | 0.0000245 (0.000017–0.00003) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 2.23 | Up |

| Sphingosine (d16:1) | 0.000086 (0.000065–0.00013) | 0.000044 (0.000036–0.000063) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 2.51 | Down |

| PAF (16:2) | 0.15 (0.13–0.18) | 0.11 (0.089–0.13) | < 0.001 | 0.0027 | 2.41 | Down |

| LPE (22:2) | 0.000046 (0.000031–0.000078) | 0.000029 (0.000024–0.000033) | < 0.001 | 0.0029 | 2.33 | Down |

| AC (20:3) | 0.000035 (0.00003–0.000044) | 0.000063 (0.000046–0.000076) | < 0.001 | 0.0029 | 1.85 | Up |

| LPC (15:0) | 0.00555 (0.0046–0.0069) | 0.0046 (0.0038–0.0053) | < 0.001 | 0.0029 | 1.96 | Down |

| LPC (18:2) | 0.014 (0.012–0.017) | 0.01 (0.0074–0.012) | < 0.001 | 0.0029 | 2.23 | Down |

| PAF (15:0) | 0.0075 (0.0059–0.0082) | 0.00535 (0.0037–0.0073) | < 0.001 | 0.0041 | 2.25 | Down |

| AC (20:4) | 0.000039 (0.000035–0.000051) | 0.0000675 (0.000047–0.00009) | < 0.001 | 0.0043 | 1.74 | Up |

| AC (22:5) | 7.75e-06 (6.10e-06–9.70e-06) | 0.0000125 (8.30e-06– 0.000018) | < 0.001 | 0.0046 | 1.51 | Up |

| PAF (18:3) | 0.00665 (0.0049–0.008) | 0.0049 (0.0033–0.0058) | < 0.001 | 0.012 | 2.04 | Down |

| PAF (20:5) | 0.0022 (0.0017–0.0031) | 0.0014 (0.0012–0.0019) | < 0.001 | 0.014 | 2.25 | Down |

| LPC (22:6) | 0.027 (0.021–0.035) | 0.017 (0.014–0.023) | < 0.001 | 0.014 | 2.08 | Down |

| LysoPAF (18:0) | 0.014 (0.011–0.017) | 0.01 (0.0077–0.014) | < 0.001 | 0.014 | 2.09 | Down |

| AEA (18:2) | 0.000155 (0.00011–0.00018) | 0.000205 (0.00017–0.00025) | < 0.001 | 0.016 | 1.54 | Up |

| AC (13:1) | 0.0019 (0.0014–0.0033) | 0.0010 (0.00082–0.0014) | < 0.001 | 0.016 | 1.61 | Down |

| GM3 (d18:1/14:0) | 0.00077 (0.00059–0.0009) | 0.00068 (0.00056–0.00076) | 0.001 | 0.020 | 1.62 | Down |

| PAF (20:4) | 0.00048 (0.00034–0.00057) | 0.000345 (0.00026–0.00042) | 0.001 | 0.021 | 1.85 | Down |

| LPC (20:3) | 0.0775 (0.063–0.098) | 0.06 (0.043–0.078) | 0.001 | 0.021 | 1.85 | Down |

| AC (22:4) | 6.90e-06 (5.10e-06–8.10e-06) | 1.00e-05 (7.40e-06– 0.000014) | 0.001 | 0.021 | 1.57 | Up |

| PAF (20:6) | 0.012 (0.0088–0.014) | 0.0083 (0.0061–0.01) | 0.002 | 0.021 | 2.03 | Down |

| PAF (18:2) | 0.00135 (0.001–0.0016) | 0.00094 (0.00079–0.0013) | 0.003 | 0.032 | 1.99 | Down |

| LPC (22:3) | 0.00021 (0.00016–0.00025) | 0.000145 (0.00011–0.0002) | 0.003 | 0.032 | 2.01 | Down |

| AEA (20:4) | 0.000068 (0.000058–0.000082) | 0.0000875 (0.000077–0.00012) | 0.003 | 0.032 | 1.93 | Up |

| GD1 (d18:1/16:0) | 0.0000285 (0.000024–0.0000415) | 0.0000235 (0.000019–0.000029) | 0.003 | 0.033 | 1.82 | Down |

| LPE (20:0) | 0.000036 (0.000028–0.000048) | 0.000026 (0.000023–0.000034) | 0.003 | 0.033 | 2.00 | Down |

| LPE (20:2) | 0.00015 (0.00011–0.00025) | 0.00012 (0.00008–0.00015) | 0.004 | 0.034 | 2.18 | Down |

| LPC (17:0) | 0.0075 (0.0061–0.0083) | 0.00595 (0.0048–0.0075) | 0.004 | 0.034 | 1.74 | Down |

| LPE (19:0) | 0.000021 (0.000014–0.000024) | 0.000015 (0.000013–0.000018) | 0.005 | 0.041 | 2.21 | Down |

| Lactosylceramide (d18:1/22:0) | 0.00045 (0.00021–0.00062) | 0.000265 (0.00017–0.00042) | 0.005 | 0.042 | 1.53 | Down |

Notes: From the 344 lipids identified by lipidomics analysis, we identified 30 lipids that differed between the MDD and HC groups. Among them, the levels of 7 types of lipids—AEA (22:4), AEA (20:4), AEA (18:2), AC (20:3), AC (20:4), AC (22:5), and AC (22:4)—were higher in the MDD than in the HC group, while the remaining 23 were higher in the HC than in the MDD group. Differences between groups were tested using univariate analysis with Welch’s t-test. The q-value, a correction value for multiple testing based on the Benjamin–Hechberg method, was calculated for the p-value. The peak area of each metabolite was normalized to that of the internal standard and sample volume to obtain the relative levels of each metabolite.

Abbreviations: AC, Acylcarnitine; AEA, acylethanolamine; GD, ganglioside; HC, healthy controls; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; MDD, major depressive disorder; PAF, platelet-activating factor; VIP, variable importance for prediction.

Figure 1.

OPLS-DA analysis and VIP score. Figure 1 illustrates OPLS-DA analysis (A) and VIP score > 1.5 (B). Of the 30 lipid types identified, 7, including AEA (22:4), AEA (20:4), AEA (18:2), AC (20:3), AC (20:4), AC (22:5), and AC (22:4), were higher in patients with MDD than in HC.

Abbreviations: AC, Acylcarnitine; AEA, acylethanolamine; HC, healthy control; MDD, major depressive disorder; OPLS-DA, orthogonal partial least-squares-DA; VIP, variable importance for prediction.

Lipid Pathway Enrichment Analysis

PubChem IDs were assigned to 29 of the 30 lipids. Lipid pathway enrichment analysis identified LPC, LPE, N-acylethanolamines, fatty acylcarnitines, and 1-alkyl-2-acylglycerophoshocholines as the characteristic pathways. Table 3 and Figure 2 present the detailed results.

Table 3.

Lipid Pathway Enrichment Analysis

| Metabolite Set | Total | Hits | Expected | p-value | q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPC | 79 | 4 | 0.00797 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| LPE | 67 | 3 | 0.00676 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| N-acyl ethanolamines | 75 | 3 | 0.00756 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Fatty acylcarnitines | 91 | 3 | 0.00918 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| 1-alkyl-2-acylglyerophosphoshocholies | 115 | 2 | 0.0116 | < 0.001 | 0.0092 |

| O-LPC | 17 | 1 | 0.00171 | 0.0017 | 0.21 |

| Monoacylglycerophopho ethanolamines | 47 | 1 | 0.00474 | 0.0047 | 0.49 |

| Sphingoid base analogs | 73 | 1 | 0.00736 | 0.00734 | 0.67 |

| Chol. esters | 86 | 1 | 0.00867 | 0.00864 | 0.70 |

| Glycosphingolipids | 452 | 1 | 0.0456 | 0.0046 | 1.0 |

Note: Lipid pathway enrichment analysis identified LPC, LPE, N-acylethanolamines, fatty acylcarnitines, and 1-alkyl-2-acylglycerophoshocholines as the characteristic pathways. In particular, LPC and LPE demonstrated the highest enrichment among altered lipid classes. The q-value, a correction value for multiple testing based on the Benjamin–Hechberg method, was calculated for the p-value.

Abbreviations: LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine.

Figure 2.

Overview of lipid pathway enriched metabolites set. Following pathway enrichment analysis, we identify LPC, LPE, N-acylethanolamines, fatty acylcarnitines, and 1-alkyl-2-acylglycerophoshocholines as high enrichment ratios.

Abbreviations: LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine.

Relationship Between Psychiatric Symptoms

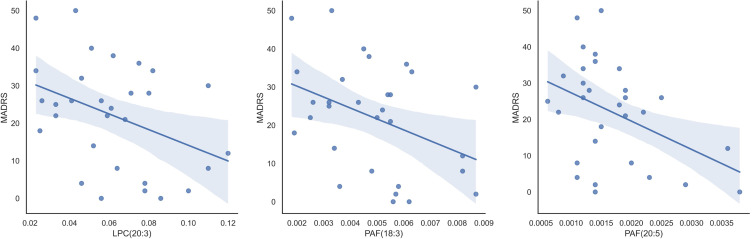

We analyzed the relationship between the 30 identified lipids and psychiatric symptoms (MADRS). Regression analysis showed that LPC (20:3), PAF (20:5), and PAF (18:3) had moderately negative correlations with MADRS (β = −0.391, p = 0.032; β = −0.414, p = 0.023; and β = −0.395, p = 0.030, respectively, β: standardized partial regression coefficient) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relation between detected lipidome and depressive symptoms. Figure 3 shows the relationship between the detected lipids and MADRS. Univariate analysis revealed that LPC (20:3), PAF (20:5), and PAF (18:3) exhibited moderately negative correlations with MADRAS (β = −0.391, p = 0.032; β = −0.414, p = 0.023; and β = −0.395, p = 0.030, respectively).

Abbreviations: LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (points); PAF, platelet-activating factor.

Discussion and Conclusion

Summary of This Study

This study used a lipidomics approach to analyze the serum lipidome of real-world Japanese patients with MDD as well as an HC group. We found that many serum lipids were decreased in patients with MDD. In addition, enrichment analysis revealed that lipid classes such as LPC, LPE, AEA, fatty acylcarnitines, and 1-alkyl-2-acylglycerophosphocholines were significantly altered in the MDD group. Furthermore, regression analysis identified LPC (20:3), platelet-activating factor (PAF) (20:5), and PAF (18:3) as negatively correlated with MADRS scores, suggesting potential links between specific lipid species and symptom severity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Graphical abstract summarizing this study’s key findings. This illustration provides an overview of the study design, major results, and key interpretations.

Background and Racial/Ethnic Lipidome Differences

Although MDD is a highly heterogeneous condition,39 the involvement of lipids in its underlying common pathophysiology has attracted increasing attention in recent years.5 Lipidomics analysis enables the comprehensive analysis of lipid profiles and has shown promise for identifying lipid classes associated with MDD.9 However, despite growing evidence that lipidomic profiles can vary across ethnic groups due to differences in diet, environmental, and genetic factors,27,40 these differences have not been sufficiently investigated in MDD. Our findings must be interpreted in light of the distinct metabolic, lifestyle, and genetic characteristics of the Japanese population. Chronic low-grade inflammation—an established feature of MDD—41 is modulated by both genetic predisposition and environmental exposure.42 Japan’s dietary patterns—marked by high fish consumption and consequently elevated intake of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids—are known to influence systemic and neuronal lipid metabolism.13–15 These nutritional habits may confer anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects and may alter the baseline lipidome, especially when compared with Western populations where red meat consumption is typically higher.43,44 Additionally, Japan’s low prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome may shape lipid-related disease phenotypes in MDD differently.29 Moreover, the proportion of individuals carrying the s/s genotype of the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism is relatively high, which is associated with greater sensitivity to stress.31,45 Thus, in Japanese individuals, the combination of low systemic inflammation, high intake of anti-inflammatory nutrients, and potential genetic resilience may result in a MDD subtype with relatively distinct lipidomic alterations.

Lipids Elevated in MDD: AEA and AC

In this study, among the few lipids that were increased in the MDD group, all belonged to the AEA and AC classes. AEAs are endocannabinoids involved in modulating neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity. Retrograde synaptic inhibition by endocannabinoids specifically impairs neuroplasticity.46–49 While our findings are consistent with the hypothesis of altered neural plasticity in MDD,50,51 the literature remains inconclusive. Some studies report reduced AEA levels in MDD, while others suggest region- or strain-specific increases or decreases in animal models.18,52,53 These discrepancies may reflect compensatory mechanisms, methodological differences, or heterogeneity within depressive phenotypes. AC, meanwhile, plays roles in mitochondrial function and fatty acid metabolism. Increased levels of medium- and long-chain AC in MDD could indicate impaired β-oxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction, aligning with evidence for an increase in metabolic abnormalities in MDD.54–56 However, given that antidepressant use may elevate AC levels,57–59 the interpretation of these results must consider medication status as a potential confounder.

Lipid Class Insights: LPC and LPE Enrichment

Enrichment analysis is crucial in omics research for discerning whether observed changes reflect biologically meaningful alterations rather than random variations. In this study, in particular, LPC and LPE demonstrated the highest enrichment among altered lipid classes; such changes are consistent with previous findings.9 LPCs are derived from phosphatidylcholine via phospholipase A2 activity, while LPEs originate from phosphatidylethanolamine. Both are involved in membrane remodeling and cellular signaling.12,60,61 Chronic stress leads to hyperactivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, resulting in elevated glucocorticoid levels. LPC and LPE induce membrane curvature and destabilization, which further accelerate the influx of glucocorticoids into cells.9 These elevated glucocorticoid levels, and the associated dysregulation of glucose and lipid metabolism, may contribute to the metabolic disturbances often observed in MDD.62 Although LPCs also have been implicated as pro-inflammatory mediators and are often found elevated in MDD,9 recent reports also indicate anti-inflammatory functions under specific conditions.11,60 Reduced LPC levels have been reported in schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease, and a negative correlation between LPC and melancholic depression severity has been documented.11,63–65 These bidirectional findings highlight the complex and context-dependent role of LPCs, suggesting that dysregulation—rather than a simple increase or decrease—may be more relevant to MDD pathophysiology.

Correlation with Depressive Symptoms: LPC and PAF

In addition to LPC, this study identified PAF (20:5 and 18:3) as inversely correlated with MADRS scores. This surprising negative correlation result was contrary to expectation. PAF is a potent phospholipid mediator involved in inflammation and vascular function and has been proposed as a mechanistic link between MDD and cardiovascular disease.66,67 Considering the chronic low-grade inflammation associated with MDD, PAF’s pro-inflammatory role would typically indicate a positive association with depression severity. One possible explanation for this contradictory result is that PAF also exerts neuroprotective functions, including the enhancement of synaptic transmission, memory, and long-term potentiation.68–70 Its dual role—as both a pro-inflammatory agent and a regulator of synaptic plasticity—may help reconcile these findings. A decrease in PAF could thus impair synaptic efficiency and contribute to cognitive and affective symptoms in MDD. These observations warrant further investigation into the pleiotropic effects of lipid mediators in psychiatric disorders.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the small sample size limits both generalizability and statistical power. Although false discovery rates were controlled using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, the possibility of type I error remains. Second, this study recruited patients with MDD who were undergoing real-world clinical treatment; thus, medication use, disease duration, and dietary habits were not fully controlled and may have influenced lipid profiles. These facts also limit the generalization of our results. Third, the cross-sectional design precluded causal inference and limited the ability to track temporal changes in lipid levels. Lastly, current lipidomics platforms capture only a subset of the lipidome (334 lipids in this study), and the potential involvement of unmeasured or unknown lipids cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

This real-world exploratory lipidomics study of Japanese patients with MDD identified several alterations and associations with psychiatric symptoms in serum lipid classes—particularly LPC, LPE, AEA, AC, and PAF—compared with HC. The marked enrichment changes observed in LPC and LPE—lipid species involved in membrane remodeling and cellular signal transduction—align with previous findings. However, the negative correlations observed with psychiatric symptom severity diverge from previously held assumptions. These results highlight the critical importance of interpreting lipidomic data within the specific contexts of population characteristics, methodological approaches, and clinical backgrounds. Although the results of this study need to take potential confounding factors into consideration, our results suggest meaningful lipidome alterations in MDD and can provide a foundation for future longitudinal and mechanistic investigations.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a UOEH Research Grant for the Promotion of Occupational Health, Japan (no. 2024-6).

Data Sharing Statement

The data derived from the participants supporting this study’s findings cannot be provided due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (protocol code: UOEHCRB21-164).

Author Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the reported work, whether in the conception, study design, execution, data acquisition, or analysis and interpretation—or in all of these areas. All authors took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2299–2312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31948-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui L, Li S, Wang S, et al. Major depressive disorder: hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):30. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01738-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buch AM, Liston C. Dissecting diagnostic heterogeneity in depression by integrating neuroimaging and genetics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(1):156–175. doi: 10.1038/s41386-020-00789-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chibaatar E, Fujii R, Ikenouchi A, et al. Evaluating apelin as a potential biomarker in major depressive disorder: its correlation with clinical symptomatology. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(24):13663. doi: 10.3390/ijms252413663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinto B, Conde T, Domingues I, Domingues MR. Adaptation of lipid profiling in depression disease and treatment: a critical review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):2032. doi: 10.3390/ijms23042032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiele C, Wunderling K, Leyendecker P. Multiplexed and single cell tracing of lipid metabolism. Nat Methods. 2019;16(11):1123–1130. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0593-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasin Y, Seldin M, Lusis A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1215-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang F, Jia Z, Gao P, et al. Metabonomics study of urine and plasma in depression and excess fatigue rats by ultra fast liquid chromatography coupled with ion trap-time of flight mass spectrometry. Mol Biosyst. 2010;6(5):852–861. doi: 10.1039/b914751a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walther A, Cannistraci CV, Simons K, et al. Lipidomics in major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickens AM, Sen P, Kempton MJ, et al. Dysregulated lipid metabolism precedes onset of psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89(3):288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knuplez E, Marsche G. An updated review of pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of plasma lysophosphatidylcholines in the vascular system. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4501. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makide K, Kitamura H, Sato Y, Okutani M, Aoki J. Emerging lysophospholipid mediators, lysophosphatidylserine, lysophosphatidylthreonine, lysophosphatidylethanolamine and lysophosphatidylglycerol. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;89(3–4):135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stillwell W, Wassall SR. Docosahexaenoic acid: membrane properties of a unique fatty acid. Chem Phys Lipids. 2003;126(1):1–27. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(03)00101-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(5):349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazinet RP, Layé S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(12):771–785. doi: 10.1038/nrn3820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosso G, Galvano F, Marventano S, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: scientific evidence and biological mechanisms. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:313570. doi: 10.1155/2014/313570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins JG. EPA but not DHA appears to be responsible for the efficacy of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28(5):525–542. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10719785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasbi A, Madras BK, George SR. Endocannabinoid system and exogenous cannabinoids in depression and anxiety: a review. Brain Sci. 2023;13(2):325. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13020325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagarkatti P, Pandey R, Rieder SA, Hegde VL, Nagarkatti M. Cannabinoids as novel anti-inflammatory drugs. Future Med Chem. 2009;1(7):1333–1349. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stirton H, Meek BP, Edel AL, et al. Oxolipidomics profile in major depressive disorder: comparing remitters and non-remitters to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatt S, Nagappa AN, Patil CR. Role of oxidative stress in depression. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25(7):1270–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto N, Hoshikawa T, Honma Y, et al. Effect modification of tumor necrosis factor-α on the kynurenine and serotonin pathways in major depressive disorder on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2024;274(7):1697–1707. doi: 10.1007/s00406-023-01713-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miao G, Deen J, Struzeski JB, et al. Plasma lipidomic profile of depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study in a large sample of community-dwelling American Indians in the strong heart study. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(6):2480–2489. doi: 10.1038/s41380-023-01948-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Li J, Zheng P, et al. Plasma lipidomics reveals potential lipid markers of major depressive disorder. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408(23):6497–6507. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9768-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan P, Suridjan I, Mohammad D, et al. Novel phospholipid signature of depressive symptoms in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(10):e008278. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J, et al. Distinct ethnic differences in lipid profiles across glucose categories. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(4):1793–1801. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pourali G, Li L, Getz KR, et al. Untargeted lipidomics reveals racial differences in lipid species among women. Biomark Res. 2024;12(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s40364-024-00635-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsugane S. Why has Japan become the world’s most long-lived country: insights from a food and nutrition perspective. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75(6):921–928. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0677-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshiike N, Miyoshi M. Epidemiological aspects of overweight and obesity in Japan—International comparisons. Nihon Rinsho. 2013;71(2):207–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stark KD, Van Elswyk ME, Higgins MR, Weatherford CA, Salem N Jr. Global survey of the omega-3 fatty acids, docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid in the blood stream of healthy adults. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;63:132–152. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okamoto N, Watanabe K, Tesen H, et al. Volume of amygdala subregions and plasma levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cortisol in patients with s/s genotype of serotonin transporter gene polymorphism of first-episode and drug-naive major depressive disorder: an exploratory study. Neurol Int. 2022;14(2):378–390. doi: 10.3390/neurolint14020031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3(NCD.RisC) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams JBW, Kobak KA. Development and reliability of a structured interview guide for the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (SIGMA). Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(1):52–58. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang Z, Chong J, Zhou G, et al. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W388–W396. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang RY, Yan YY, Li B, et al. Pattern recognition analysis of metabolites in Escherichia coli based on ESI-Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Chem Biodivers. 2023;20(5):e202201153. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.202201153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, Chen T, Sun L, et al. Potential metabolite markers of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(1):67–78. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, et al. PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1388–D1395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao Q, Tian T, Chen J, Guo X, Zhang X, Zou T. Serum metabolic profiling of late-pregnant women with antenatal depressive symptoms. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:679451. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.679451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Athira KV, Bandopadhyay S, Samudrala PK, Naidu VGM, Lahkar M, Chakravarty S. An overview of the heterogeneity of major depressive disorder: current knowledge and future prospective. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2020;18(3):168–187. doi: 10.2174/1570159X17666191001142934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhargava A, Knapp JD, Fiehn O, Neylan TC, Inslicht SS. An exploratory study on lipidomic profiles in a cohort of individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):15256. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-62971-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yirmiya R. The inflammatory underpinning of depression: an historical perspective. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;122:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.08.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giollabhui NM, Slaney C, Hemani G, et al. Role of inflammation in depressive and anxiety disorders, affect, and cognition: genetic and non-genetic findings in the lifelines cohort study. medRxiv. 2024:2024.04.17.24305950. doi: 10.1101/2024.04.17.24305950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coe CL, Love GD, Karasawa M, et al. Population differences in proinflammatory biology: japanese have healthier profiles than Americans. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(3):494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen TS, Bhatia HS, Wood AC, Momin SR, Allison MA. State-of-the-art review: evidence on red meat consumption and hypertension outcomes. Am J Hypertens. 2022;35(8):679–687. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpac064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murakami F, Shimomura T, Kotani K, Ikawa S, Nanba E, Adachi K. Anxiety traits associated with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region in the Japanese. J Hum Genet. 1999;44(1):15–17. doi: 10.1007/s100380050098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kano M, Ohno-Shosaku T, Hashimotodani Y, Uchigashima M, Watanabe M. Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(1):309–380. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohno-Shosaku T, Maejima T, Kano M. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signals from depolarized postsynaptic neurons to presynaptic terminals. Neuron. 2001;29(3):729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00247-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410(6828):588–592. doi: 10.1038/35069076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heifets BD, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid signaling and long-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:283–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuhn M, Höger N, Feige B, Blechert J, Normann C, Nissen C. Fear extinction as a model for synaptic plasticity in major depressive disorder. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338(6103):68–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1222939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bright U, Akirav I. Modulation of endocannabinoid system components in depression: pre-clinical and clinical evidence. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10):5526. doi: 10.3390/ijms23105526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smaga I, Jastrzębska J, Zaniewska M, et al. Changes in the brain endocannabinoid system in rat models of depression. Neurotox Res. 2017;31(3):421–435. doi: 10.1007/s12640-017-9708-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmed AT, MahmoudianDehkordi S, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Acylcarnitine metabolomic profiles inform clinically-defined major depressive phenotypes. J Affect Disord. 2020;264:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen S, Wei C, Gao P, et al. Effect of Allium Macrostemon on a rat model of depression studied by using plasma lipid and acylcarnitine profiles from liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014;89:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moradi Y, Albatineh AN, Mahmoodi H, Gheshlagh RG. The relationship between depression and risk of metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40842-021-00117-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu T, Deng K, Xue Y, et al. Carnitine and depression. Front Nutr. 2022;9:853058. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.853058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kang M, Yoo HJ, Kim M, Kim M, Lee JH. Metabolomics identifies increases in the acylcarnitine profiles in the plasma of overweight subjects in response to mild weight loss: a randomized, controlled design study. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0887-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MahmoudianDehkordi S, Ahmed AT, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Alterations in acylcarnitines, amines, and lipids inform about the mechanism of action of citalopram/escitalopram in major depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):153. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01097-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Law SH, Chan ML, Marathe GK, Parveen F, Chen CH, Ke LY. An updated review of lysophosphatidylcholine metabolism in human diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(5):1149. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Đukanović N, Obradović S, Zdravković M, et al. Lipids and antiplatelet therapy: important considerations and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):3180. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshimura R, Watanabe C. Comorbidity of major depression and type 2 diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment approaches. J UOEH. 2025;47(2):95–103. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.47.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Troubat R, Barone P, Leman S, et al. Neuroinflammation and depression: a review. Eur J Neurosci. 2021;53(1):151–171. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Osimo EF, Pillinger T, Rodriguez IM, Khandaker GM, Pariante CM, Howes OD. Inflammatory markers in depression: a meta-analysis of mean differences and variability in 5166 patients and 5083 controls. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:901–909. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rolin J, Vego H, Maghazachi AA. Oxidized lipids and lysophosphatidylcholine induce the chemotaxis, up-regulate the expression of CCR9 and CXCR4 and abrogate the release of IL-6 in human monocytes. Toxins. 2014;6(9):2840–2856. doi: 10.3390/toxins6092840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mazereeuw G, Herrmann N, Xu H, et al. Platelet activating factors are associated with depressive symptoms in coronary artery disease patients: a hypothesis-generating study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2309–2314. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S87111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM. Platelet-activating factor, a pleiotrophic mediator of physiological and pathological processes. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40(6):643–672. doi: 10.1080/714037693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hammond JW, Lu SM, Gelbard HA. Platelet activating factor enhances synaptic vesicle exocytosis via PKC, elevated intracellular calcium, and modulation of synapsin 1 dynamics and phosphorylation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:505. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bazan NG. The neuromessenger platelet-activating factor in plasticity and neurodegeneration. Prog Brain Res. 1998;118:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63215-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kato K, Clark GD, Bazan NG, Zorumski CF. Platelet-activating factor as a potential retrograde messenger in CA1 hippocampal long-term potentiation. Nature. 1994;367(6459):175–179. doi: 10.1038/367175a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data derived from the participants supporting this study’s findings cannot be provided due to privacy or ethical restrictions.