Abstract

Human and bovine respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are significant causes of morbidity and mortality in human and cattle populations worldwide, respectively. RSV disease is characterized by deleterious inflammatory immune responses as well as generation of radical oxygen species in the airways. Recent reports have shown antiviral and anti-inflammatory activity of NRF2 agonists and immunometabolite derivatives 4-octyl-itaconate (4-OI) and dimethyl fumarate (DMF), suggesting their potential to protect against viral-induced inflammation. Here, we evaluated whether 4-OI or DMF impact human and bovine RSV replication and its associated inflammatory response in vitro and the efficacy of these NRF2 agonists in preventing RSV disease in a murine model. We observed that 4-OI and DMF inhibited the early inflammatory response to RSV as well as reduced infectious titers in epithelial cells. Moreover, mice treated with 4-OI or DMF were partially protected against RSV-induced weight loss and airway inflammation and showed reduced viral loads and interleukin-6 levels in the lung. Overall, these results support the use of NRF2 agonists 4-OI and DMF in the prevention of RSV disease in target populations.

Keywords: large animals, lung, rodent, viral

Introduction

The human orthopneumovirus (human respiratory syncytial virus [hRSV]) is a leading agent of acute lower respiratory tract disease in infants and children. Estimations indicate that hRSV is responsible for 33 million cases of respiratory disease in children under 5 years of age every year and leads to more than 100,000 deaths, mainly in low- and middle-income countries.1,2 Additionally, severe hRSV infection can predispose to otitis media and is associated with the development of asthma and recurrent wheezing.3,4 Recently, the Food and Drug Administration has approved vaccines to prevent severe hRSV infection in the elderly and in pregnant women; however, no efficacious interventions to prevent hRSV in infants are available at a global scale, and therefore, the burden of hRSV continues to impact the public health worldwide.

Bovine RSV (bRSV) infection is a highly prevalent pathogen that leads to significant morbidity and mortality in bovine populations and to major economic losses to the cattle industry. As a sole agent, bRSV is a frequent cause of respiratory disease in young calves and seasonal pneumonia in nursing beef calves.5 More importantly, bRSV is a viral etiological agent of bovine respiratory disease, a multifactorial respiratory syndrome in which several pathogens, host, and environmental factors come into play.6 Despite the widespread use of antimicrobial drugs and vaccination in the cattle industry, little progress has been made during the last decades to reduce bovine respiratory disease prevalence, posing a threat to industry sustainability efforts.7

Severe RSV disease in both species is characterized by upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms, with the development of bronchiolitis and pneumonia being hallmarks of severe RSV infection. The immune response to the viral particle is considered a major factor in the development of lung lesions. Infection of the lower respiratory tract by RSV triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by airway epithelial cells (ECs), which in turn recruit inflammatory cells to the airways. The myeloid cell infiltration includes several cells with neutrophils as a major component,8,9 which can undergo NETosis and apoptosis, inducing damage to the lung.10,11 Overall, there is an increase of T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cytokines systemically and in the airways, and several studies suggest that a Th2-biased proinflammatory response is responsible for limiting proper antiviral activity and for perpetuating a deleterious inflammatory condition.12 Understanding the key processes that lead to airway inflammation and how to overturn them has been a major focus in RSV research and its crucial for rational design of prophylactic interventions.

Along with inflammatory cell infiltration and cytokine secretion, dysregulated oxidative responses to RSV have also been associated with pathogenesis and disease severity.5 RSV infection leads to increased production of H2O2 and accumulation of superoxide and hydroxyl radicals while downregulating cell protective antioxidant responses in the airways.13,14 Moreover, in vitro studies indicate that hRSV induces degradation and reduced nuclear and cytoplasmic levels of NRF2, a master transcriptional regulator of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant responses, leading to reduced expression of antioxidant enzymes (AOEs).15,16 The absence of the NRF2-antioxidant response element (ARE) pathway signaling leads to enhanced disease, viral titers, and proinflammatory cytokine levels in the context of RSV and human metapneumovirus infections, and enhanced lung fibrosis after RSV infection.17,18 Importantly, antioxidant activity recovery has been associated with protection against severe RSV infection in murine models,19–21 highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target. Regarding cattle, transcriptomic profiling studies point to dysregulated oxidative responses as a contributing factor to lung lesion development in bRSV infection,22 while a proteomic quantitative study revealed decreased levels of several antioxidant enzymes in the airways.23 These studies indicate that the NRF2 pathway is a promising intervention target to reduce the severity of RSV infection in humans and the bovine population by modulating ROS levels.

Recently, a suppression of NRF2-derived anti-inflammatory and antioxidant responses has been observed in lung biopsies obtained from patients undergoing SARS-CoV-2 infection, suggesting the importance of this pathway in inhibiting host immunopathological responses to infection.24 In this line, administration of synthetic NRF2 agonists such as 4-octyl itaconate (4-OI) and dimethyl fumarate (DMF) elicits type I interferon (IFN)–independent antiviral activity in SARS-CoV-2 infection while also reducing the inflammatory response by ECs in vitro.24 Moreover, the administration of NRF2 agonists has been reported to reduce lung inflammation and mortality in influenza A virus (IAV) mouse models.25 Recent reports also indicate that 4-OI treatment reduces viral infectious titers after IAV infection of ECs,26 as well as replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in porcine alveolar macrophages in vitro while reducing their inflammatory response to the viral particles.27 These data suggest that NRF2 agonists have the potential to prevent or reduce lung pathology induced by inflammatory conditions arising from respiratory viral infections. Here, we characterized effects of 4-OI and DMF treatment in vitro on hRSV and bRSV and in vivo in a murine model of RSV infection, to explore their potential to be applied as immunomodulatory strategies against respiratory disease in human and bovine population.

Materials and methods

Viruses

HRSV A/1997 (provided by Dr. David Verhoeven, Iowa State University) was grown in HEp2 cells, and bRSV st. 375 was prepared from virus stock reisolated from the lung of an infected calf and passaged <3 times on low-passage bovine turbinate (BT) cells. Viruses were then concentrated using PEG precipitation technique to reach 1 × 108 median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50)/mL and 2.3 × 108 TCID50/mL for bRSV and hRSV, respectively. Viral stocks were stored at −80 °C until use.

Cells and in vitro infection experiments

BT (ATCC; CRL-1390) and HEp-2 (ATCC; CCL-23) cells were grown in complete minimal essential media (cMEM) with 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco; 21127 022), 1× antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco; 15240062), and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco 11360070) and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco; 16000-044). BEAS-2b cells were grown in flasks precoated with 0.03% type I bovine collagen (Gibco; A1064401), 0.01% fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich; F4759), and 0.01% bovine serum albumin (Thermo Fisher Scientific; J65731-30) in BEGM Bronchial Epithelial Cell Growth Medium BulletKit (Lonza; CC-3170). All cells were grown at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in an Isotemp CO2 incubator (Fisherbrand) in tissue culture-treated polystyrene flasks with vented caps (FB012935, FB0129357 [Fisherbrand]; 353208 [Corning]).

For gene expression experiments and quantification of infectious titers, either BT or BEAS-2b cells were grown in polystyrene flasks, then subcultured into 6- or 12-well plates (Celltreat; 229105, 229111). When reaching around 80% confluency, cells were treated with 4-OI (Sigma-Aldrich; SML2338) at 100 or 200 μM, DMF (from Sigma-Aldrich; 242926) at 50 to 100 μM, or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] at 1%) for 6 h. Cells were then infected with hRSV 1/1997 or bRSV st. 375 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 for 2 h in serum-free MEM at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After adsorption, infectious material was removed and cells received cMEM and were placed in a CO2 incubator for 24 or 48 h. Samples used for gene expression were lysed for RNA extraction after 12 or 48 h, and samples used for quantification of infectious titers were frozen at −80 °C after 48 h. For samples collected at 48 h only, a second dose of agonists was administered 24 h after infection. In a separate experiment evaluating the effects of post-infection drug administration on infectious titers, BEAS-2b and BT cells were infected with hRSV 1/1997 and bRSV st. 375, respectively, at an MOI of 0.1 for 2 h in serum-free MEM at 37 °C, 5% CO2, then treated with DMF or 4-OI at different concentrations 24 h after infection. Plates were frozen 48 h after infection at −80 °C until use.

MTT cell viability assay

A CyQUANT MTT Cell Viability Assay (Invitrogen; 2462682) was modified to be carried out in 24-well plates. The MTT and SDS-HCl solutions were prepared as indicated by the manufacturer; however, the volumes used were changed to suit 24-well plates. Varying concentrations of 4-OI and DMF in DMSO were prepared in cMEM of BEGM as specified previously. BT cells and BEAS-2b cells were grown until reaching 80% confluency and stimulated with varying concentrations of 4-OI and DMF in DMSO, or DMSO only (vehicle), for 24 h. Cells were resuspended in 200 µL of an MTT solution and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. MTT crystals were then mixed with 200 µL of an SDS-HCl solubilization mixture and returned to the incubator for an ON incubation. Finally, the well content was transferred to a flat-bottomed 96-well plate to be read at 570 nm in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) microplate reader (Fisher Scientific accuSkan FC Filter-Based Microplate Photometer).

RNA and complementary DNA preparation, and real-time polymerase chain reaction for gene expression experiments

BT or BEAS-2b cells were lysed in Lysis buffer from MagMAX mirVana Total RNA Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems; A27828), and RNA was isolated using the kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Mouse lungs were placed in TRIzol (Invitrogen, Life Technologies; 15596018), homogenized, and then stored at −20 °C for 24 h, the RNA was isolated using an RNEasy Mini Kit including DNAse treatment per manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen; 74104). RNA concentration was measured on a Qubit fluorometer using the Qubit RNA Broad Range Assay Kit (Invitrogen; Q10211). A total of 500 ng were used to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) using random primers and Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen; 18080044). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; A46110). Forward and reverse primers for target and housekeeping genes are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Reactions were performed on a QuantStudio 5 System (Applied Biosystems; A28140). The following amplification conditions were used: 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C, and a dissociation step (15 s at 95 °C, 1 min at 60 °C, 15 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 60 °C). Relative gene expression was determined using the 2-ΔΔCt method,28 using the uninfected, vehicle-treated condition as a calibrator, and human GAPDH and bovine RPS9 and as housekeeping genes. Two technical replicates were used for each reaction.

Table 1.

Primers sequences used in in vitro gene expression experiments.

| Target | Forward sequence 5′-3′ | Reverse sequence 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| Human IL-1β | AAGCTGATGGCCCTAAACAG | AGGTGCATCGTGCACATAAG |

| Human IL-6 | AGACAGCCACTCACCTCTTCAG | TTCTGCCAGTGCCTCTTTGCTG |

| Human CXCL8 | GAGAGTGATTGAGAGTGGACCAC | CACAACCCTCTGCACCCAGTTT |

| Human IFN-Β | CTTGGATTCCTACAAAGAAGCAGC | TCCTCCTTCTGGAACTGCTGCA |

| Human CCL5 | CCTGCTGCTTTGCCTACATTGC | ACACACTTGGCGGTTCTTTCGG |

| Human GAPDH | ACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGA | CTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGT |

| Bovine il-6 | CTGAAGCAAAAGATCGCAGATCTA | CTCGTTTGAAGACTGCATCTTCTC |

| Bovine cxcl8 | CGCTGGACAGCAGAGCTCACAAG | GCCAAGAGAGCAACAGCCAGCT |

| Bovine ifn-β | CCTGTGCCTGATTTCATCATGA | GCAAGCTGTAGCTCCTGGAAAG |

| Bovine isg15 | GTGGTGCAGAACTGCATCTC | GCCAGAACTGGTCTGCTTGT |

| Bovine ccl5 | CACCCACGTCCAGGAGTATT | AGGACAAGAGCGAGAAGCAA |

| Bovine catalase | TGGGACCCAACTATCTCCAG | AAGTGGGTCCTGTGTTCCAG |

| Bovine nqo1 | TGTATGCCATGAACTTCAC | AGTCTCGGCAGGATACTGAAA |

| Bovine hmox1 | CAAGGAGAACCCCGTCTACA | CCAGACAGGTCTCCCAGGTA |

| Bovine nrf2 | AGGACATGGATTTGATTGAAC | TACCTGGGAGTAGTTGGCA |

| Bovine rps9 | CGCCTCGACCAAGAGCTGAAG | CCTCCAGACCTCACGTTTGTTCC |

Table 2.

Primers sequences used in in vivo gene expression experiments and viral load quantification.

| Target | Forward sequence 5′-3′ | Reverse sequence 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse il-6 | TAGTCCTTCCTACCCCAATT | TTGGTCCTTAGCCACTCCTTC |

| Mouse cxcl1 | TCCAGAGCTTGAAGGTGTTGCC | AACCAAGGGAGCTTCAGGGTCA |

| Mouse ifn-β | AGCTCCAAGAAAGGACGAACA | GCCCTGTAGGTGAGGTTGAT |

| Mouse ccl5 | CCTGCTGCTTTGCCTACCTCT | ACACACTTGGCGGTTCCTTCGA |

| Mouse actb | AGGCATCCTGACCCTGAAGTAC | TCTTCATGAGGTAGTCTGTCAG |

| hRSV nucleoprotein | GAGACAGCAGCATTGACACTCCT | CGATGTGTTGTTACATCCACT |

Quantification of viral infectious titers

Infected BT and BEAS-2b cells treated with DMF, 4-OI, or vehicle were frozen at −80 °C. HEP-2 cells were grown in T-75 flasks until 80% confluency, then subcultured into 96-well flat-bottom plates. When titration plates were 80% confluent, frozen plates were thawed and either BT and HEp-2 was infected with 10-fold sf-MEM dilutions of 100 µL of infectious cell culture media during 2 h. Each sample was tested using 3 technical replicates. After 2 h, cells received cMEM and were placed in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 4 d (HEp-2 cells) or 6 d (BT cells), then CPE was observed under a microscope couple to a Nikon DS-vi1 camera. Titers were then calculated using the Reed and Muench method and expressed as TCID50/mL.

Animal experiments

All procedures involving mice were approved by the Iowa State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (22-139) and were carried out according to the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition, 2011, and the American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020 Edition). Five- to 6-wk-old female BALB/cJ mice (Jackson Laboratory; strain 000651) were transported to climate-controlled rooms and allowed to condition for 5 d. On day −1, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and intranasally (i.n.) administered saline (vehicle), DMF at 80 μg, or 4-OI at 400 μg dissolved in a sterile saline pH-neutral solution. On day 0, animals were either mock infected (DMEM) or infected intranasally with 50 µL of 2.3 × 108 TCID50/mL under isoflurane anesthesia. Animals received the same dose of agonists on days 1 and 2. Animals were monitored and weighed daily starting day −1 until day 3, when animals were euthanized using CO2 inhalation. Lungs were collected and homogenized in TRIzol for RNA preparation or in 1× cell lysis buffer 2 (R&D Systems, Bio-Techne; 895347) for protein lysate preparation and stored at −20 °C until use. In separate experiments, whole lungs were formalin-fixed for histopathology analyses.

RT-PCR for viral load quantification and relative expression in animal studies

Lung tissue was processed for RNA and cDNA preparation as stated previously. RT-PCR reactions targeting different transcripts were performed as indicated previously. Relative gene expression was determined using the 2-ΔΔCt method28 using primers in Table 1 and mouse β-actin as the housekeeping gene. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) targeting N-hRSV and mouse β-actin were performed using PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; A46110) to quantify viral loads. Primers used are listed in Table 2. Results were expressed as N-hRSV copies per 1,000 mouse β-actin copies according to standard curves run for both target and housekeeping genes. Two technical replicates were used for each reaction.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Lung lysates were prepared by homogenizing the lung tissue in 1× cell lysis buffer 2, then incubating at RT for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 2.000 rpm for 5 min. Supernatants were stored at −20 °C until use. IL-6 levels were then quantified using mouse IL-6 DuoSet ELISA (R&D Systems, Bio-Techne; DY406) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (accuSkan FC Filter-Based Microplate Photometer), and a 4-parameter logistic regression standard curve was used to quantify IL-6 in each sample using blank-substracted absorbance values. Two technical replicates were used for each reaction.

Determination of H2O2 levels in mouse lungs

Mouse lungs were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and left to dry, then weighed. Tissue was then diluted in cold PBS at a ratio or 10 mg tissue/mL of PBS, then homogenized, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were stored at −80 °C until analyzed. H2O2 levels where then measured in supernatants using the OxiSelect Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit (Colorimetric) (Cell Biolabs; STA-844) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (accuSkan FC Filter-Based Microplate Photometer), and a 4-parameter logistic regression standard curve was used to quantify H2O2 in each sample using blank-substracted absorbance values. Two technical replicates were used for each reaction.

Histopathology analysis

Formalin-fixed whole lungs from mice were submitted to the Comparative Pathology Core Service at Iowa State University for histopathological examination of hematoxylin and eosin–stained lung slides. Lesions were scored on a scale of 0 to 3 (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) in the following categories: airway epithelial necrosis, % inflamed airways (peribronchiolar lymphocytes), perivascular lymphocytes, alveolar luminal exudate, pneumocyte hypertrophy/hyperplasia, and interstitial infiltrates. All samples were analyzed by blinded, board-certified veterinary pathologists.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses and plots were made on GraphPad Prism V.10 (GraphPad Software). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM or as median ± range. Gene expression, protein levels and viral loads were analyzed using 1-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Weight curves were analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance with repeated measures, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. In vitro infectious titers and in vivo airway infiltration, lung pathology scores, and H2O2 levels were analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis test due to non-normal distribution of the data according to a Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

DMF and 4-OI effects on transcription of NRF2-derived enzymes during bRSV infection

In order to select doses for our assays, we first determined cell viability after administration of DMF and 4-OI at different doses in BT and BEAS-2b cells, 24 h after treatment. We observed that viability of BT and BEAS-2b cells was significantly affected by DMF at concentrations of 200 μM/mL of higher (Fig. S1). We observed significantly reduced viability after 4-OI treatment when administered at 500 μM/mL in BEAS-2b cells. Based on these results, we chose to carry out our assays using concentrations that did not affect cell viability: DMF at 50 and 100 μM/mL and 4-OI at 100 and 200 μM/mL.

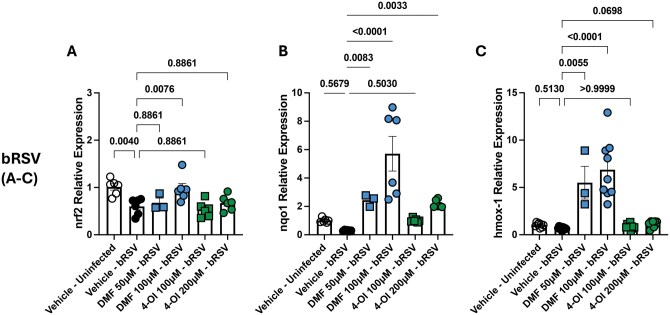

Both DMF and 4-OI are well-known NRF2 agonists; however, the relevance of this has not been explored in the context of bRSV infection. To determine whether these agonists can improve antioxidative responses of respiratory epithelium during bRSV infection, we pretreated BT cells with DMF or 4-OI for 6 h, infected them with bRSV at an MOI of 0.1, and then analyzed transcription of nrf2 and NRF-2-ARE–induced enzymes hmox1, catalase, and nqo1 during early infection times (12 h). bRSV infection significantly downregulated nrf2 (P = 0.004 compared with uninfected, vehicle-treated cells) (Fig. 1). Compared with bRSV-infected, control cells, treatment with 4-OI at 200 μM/mL and DMF at 100 μM/mL upregulated transcription of hmox1 (P = 0.0348 and P < 0.0001, respectively) and nqo1 (P = 0.0033 and P < 0.0001, respectively) but not catalase. nrf2 transcription was restored to normal levels only by DMF treatment at 100 μM/mL (P = 0.0076). Overall, these results suggest that DMF and 4-OI act as agonists of NRF-ARE pathway in bRSV-infected ECs.

Figure 1.

4-OI and DMF modulate transcription of nrf2 and NRF2-ARE–induced enzymes in BT cells during bRSV infection. BT cells were pretreated with DMF (50, 100 µM) or 4-OI (100, 200 µM) and infected 6 h later with bRSV at an MOI of 0.1. Twelve hours later, RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed to cDNA, and relative expression of (A) nrf2, (B) nqo1, and (C) hmox1 was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Expression level was normalized to vehicle-treated, uninfected cells, and rps9 was used as housekeeping gene. Data show the mean ± SEM from 2 independent experiments (n = 3–9), and all data points were plotted. P values were obtained from a 1-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

DMF and 4-OI suppress inflammatory responses to hRSV and bRSV infection in vitro

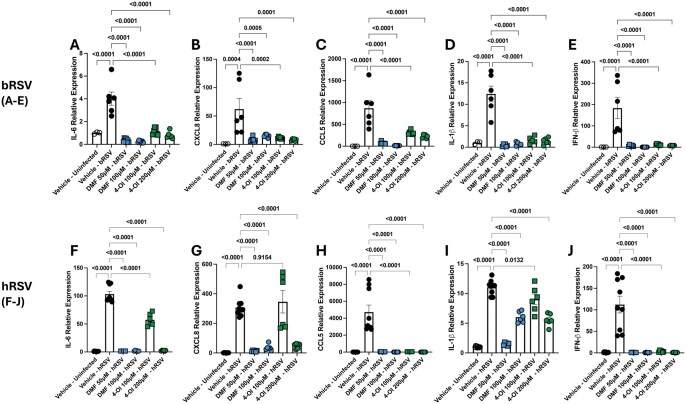

To determine whether synthetic NRF-2 agonists are able to modulate inflammatory cytokine transcription in ECs during bRSV and hRSV infection, BT and BEAS-2b cells were pretreated with DMF and 4-OI for 6 h and then infected with bRSV and hRSV at an MOI of 0.1. Cells were again treated with the agonists 24 h after infection. As expected, we observed increased relative expression of il-1β, il-6, ccl5, and cxcl8 transcription after hRSV and bRSV infection in their respective cell lines. More importantly, both agonists had a potent suppressive activity on il-1β, il-6, ccl5, and cxcl8 transcription after bRSV infection at all tested doses (Fig. 2A–D). The potent immunosuppressive effect was also observed in hRSV infection of BEAS-2b cells after treatment with DMF at both doses and 4-OI at 200 μM/mL. When 4-OI was administered at 100 μM/mL, we observed a strong downregulation of ccl5 only, and a milder but significant downregulation of il-1β and il-6, but cxcl8 levels remained unchanged (Fig. 2F–I). We also quantified the relative expression of IFN-β and observed that DMF and 4-OI strongly inhibited ifn-β transcription during bRSV and hRSV infection (Fig. 2E, J). Overall, 4-OI and DMF downregulated antiviral and anti-inflammatory responses to bRSV and hRSV infection in ECs in vitro.

Figure 2.

4-OI and DMF strongly downregulate inflammatory responses to bRSV and hRSV infection and ifn1b transcription in respiratory ECs. (A–E) BT and (F–J) BEAS-2b cells were pretreated with DMF (50, 100 µM) or 4-OI (100, 200 µM) and infected 6 h later with bRSV or hRSV, respectively, at an MOI of 0.1. Treatments were repeated daily twice. After 72 h, RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed to cDNA, and relative expression of (A, F) il-6, (B, G) cxcl8, (C, H) ccl5, (D, I) il-1b, and (E, J) ifnb1 was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The expression level was normalized to vehicle-treated, uninfected cells, and rps9 was used as a housekeeping gene. Data show the mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments (n = 6–9), and all data points were plotted. P values were obtained from a 1-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

DMF and 4-OI reduce hRSV and bRSV infectious titers in vitro

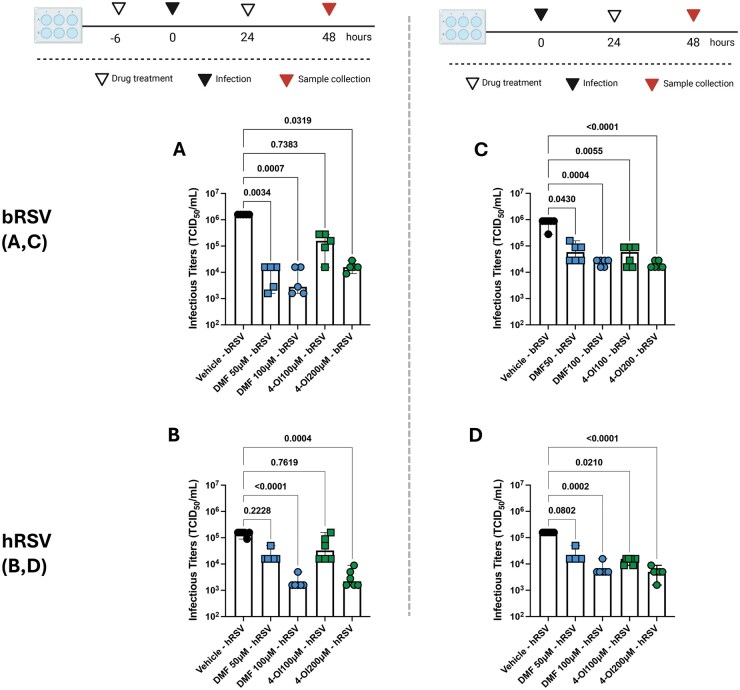

To evaluate whether DMF and 4-OI treatment exert antiviral activity on RSV infection of ECs, we quantified infectious titers (as TCID50/mL) of bRSV and hRSV after infection of BT and BEAS-2b cells, respectively. BT and BEAS-2b cells were pretreated with DMF and 4-OI then infected 6 h later with bRSV and hRSV as previously detailed. Cells were frozen at −80 °C 48 h after infection and then thawed, and infectious titers were quantified. We observed that DMF displayed significant antiviral activity when used at 50 or 100 μM/mL in bRSV infection (P = 0.0034 and P = 0.0007, respectively) and when used at 100 μM/mL in hRSV infection (P < 0.0001). On the other hand, 4-OI led to significantly reduced hRSV (P = 0.0004) and bRSV (P = 0.0319) infectious titers only at the 200 μM/mL dose (Fig. 3A, B). When the NRF2 agonists were administered 24 h after infection, bRSV titers were reduced by 4-OI when used at 100 μM/mL (P = 0.0055) and 200 μM/mL (P < 0.0001), and by DMF when used at 50 μM/mL (P = 0.0430) and 100 μM/mL (P < 0.0001) (P = 0.0004) (Fig. 3C). Similarly, hRSV titers were reduced when 4-OI was administered 24 h after infection at 50 and 100 μM/mL concentrations (P = 0.021 and P < 0.0001, respectively) and when DMF was used after infection at 200 μM/mL (P = 0.002) (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that DMF and 4-OI treatment reduce RSV infection in bovine and human ECs, and this may be independent of type I IFN responses.

Figure 3.

4-OI and DMF reduce hRSV and bRSV infectious titers in vitro. (A, B) BT and BEAS-2b cells were pretreated with DMF (50, 100 µM) or 4-OI (100, 200 µM) and infected 6 h later with bRSV or hRSV, respectively, at an MOI of 0.1. A second dose of DMF, 4-OI, or vehicle was administered 24 h after infection. (C, D) BT and BEAS-2b cells were infected with bRSV or hRSV. Then, 24 h later, cells were treated with DMF (50, 100 µM) or 4-OI (100, 200 µM). In both experiments, plates were frozen after 48 h, and infectious titers were determined by culture titration in BT (bRSV) or HEp-2 (hRSV) cells and calculated using the Reed and Muench method. Titers are expressed as TCID50/mL. Data show the median ± range from 2 independent experiments (n = 5–6), and all data points were plotted. P values were obtained from a Kruskal-Wallis test. Diagram created in BioRender.

Effects of intranasal DMF and 4-OI administration in RSV mouse infection model

We next explored the effects of DMF or 4-OI treatment in a murine model of hRSV infection. First, we carried out a pilot study to determine drug doses to be administered intranasally and observed a trend in reduced viral loads in lung of animals pretreated with DMF at 40 μg/animal and 4-OI at 100 μg/animal but no significant effect on weight loss with any drug/dose scheme (Fig. S2) when compared with animals that received vehicle (2% DMSO in saline solution, vehicle treated). Next, 6-wk-old female BALB/c were pretreated i.n. with DMF at 80 μg/animal, 4-OI at 400 μg/animal, or vehicle, then challenged i.n. with 50 µL of hRSV at 2.3 × 108 TCID50/mL or mock (noninfectious cell culture supernatant). Animals were treated intranasally with DMF or 4-OI or vehicle every 24 h, then were humanely euthanized on day 3 postinfection to collect whole lungs for histopathology, viral load quantification by RT-PCR, and tissue lysates (Fig. 4A). Treatment with either DMF or 4-OI was able to significantly reduce weight loss on days 1 (P = 0.005 and P = 0.033, respectively), 2 (P = 0.0017 and P = 0.0088, respectively), and 3 (P = 0.0011 and P = 0.001, respectively) postinfection and lung viral loads (P = 0.03 and P = 0.019, respectively) at day 3 postinfection after hRSV infection compared with vehicle-treated, hRSV animals (Fig. 4B, C). Histopathology analyses indicated that RSV infection in mice generated mild-to-moderate airway inflammation, with moderate presence of perivascular and peribronchiolar lymphocytes, and alveolar luminal exudates consisting mainly of neutrophils and macrophages. Intranasal 4-OI treatment significantly reduced (P = 0.022) the percentage of airway inflammation and the consolidated histopathology score (P = 0.0012) (Fig. 4D, E). DMF-treated animals showed a trend toward reduced airway infiltration (P = 0.0509) but no reduction in consolidated lung pathology, indicating that the treatment did not reduce lung damage after hRSV infection. Therefore, despite providing similar levels of virological protection in mice, 4-OI and DMF provide different levels of protection against RSV disease, with only intranasal 4-OI reducing lung damage along with morbidity.

Figure 4.

Effects of repeated intranasal 4-OI and DMF administration in RSV disease in mice. (A) Experiment design. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and i.n. administered saline (vehicle), DMF at 80 μg, or 4-OI at 400 μg. Six hours later, mice were either mock infected (DMEM) or infected i.n. with 50 µL of 2.3 × 108 TCID50/mL hRSV A/1997. Animals were given drugs daily and were euthanized 72 h after infection. (B) Lungs (n = 7–8, all data points plotted) were collected and homogenized in TRIzol for RNA and cDNA preparation. N-hRSV and beta-actin copies were determined by RT-PCR. P values were obtained from a 1-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Body weights from mice (n = 9–12, all data points plotted) were recorded daily after infection and weight percentage relative to day 0 was calculated. P values were obtained from a 2-way analysis of variance with repeated measures and followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (D, E) Whole lungs from mice (n = 3–9) were formalin-fixed for histopathology scoring performed by blinded, trained pathologist with criteria specified in material and methods. P values obtained from a Kruskal-Wallis test. Data in panels D and E show median ± range from 3 independent experiments, and all data points were plotted. **P < 0.01. D, day. Diagram created in BioRender.

Lung inflammatory responses to RSV in DMF- and 4-OI–treated mice

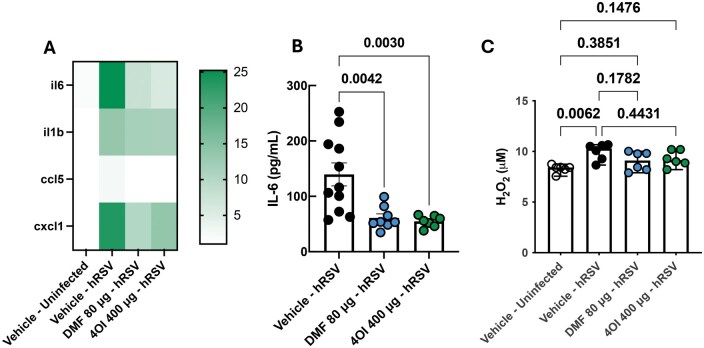

To gain further insights on the effects of the agonists on the inflammatory response during RSV infection, we quantified transcripts of proinflammatory cytokines of importance during RSV infection. We observed that il-6 (P = 0.0036), il-1β (P = 0.0002), cxcl1 (P = 0.0145), and ccl5 (P = 0.0057) were strongly upregulated in RSV-infected, vehicle-treated animals in comparison with uninfected animals (Fig. 5A; Fig. S3). However, il-6 and ccl5 transcription were downregulated in DMF-treated (P = 0.0032 and P = 0.0002, respectively) and 4-OI–treated (P = 0.001 and P = 0.0005, respectively) animals (Fig. 5A; Fig. S3). IL-6 protein levels were also downregulated by DMF (P = 0.0061) and 4-OI (P = 0.0105) treatment (Fig. 5B). We observed no significant treatment effect on il-1β and cxcl1 transcript levels in lungs. In order to understand whether NRF2 agonist treatment has effects on H2O2 production, we measured its level in the lung tissue. We observed increased H2O2 levels in lungs of vehicle-treated animals (P = 0.062) when compared with uninfected, vehicle-treated animals, but not in DMF- or 4-OI–treated animals, indicating that NRF2 agonist treatment modulated H2O2 levels in the lung (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Effects of intranasal 4-OI and DMF administration in the inflammatory response and H2O2 production in RSV infected mice lungs. (A) RNA and cDNA were processed from mice lungs (n = 9) and transcription of inflammatory cytokines was determined through RT-PCR. Expression level was normalized to vehicle-treated, uninfected cells, and beta-actin (mouse) was used as a housekeeping gene. Statistical analyses results are shown in Figure S3. (B) IL-6 protein levels were quantified in mice lung lysates (n = 8–11) through an indirect ELISA. P values were obtained from a 1-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. For A and B, data show the mean ± SEM 3 independent experiments. (C) H2O2 levels were measured in mice lung lysates (n = 6) using a colorimetric assay. P values were obtained from a Kruskal-Wallis test. Data show the median ± range from 2 dependent experiments. All data points were plotted.

Discussion

Despite the use of vaccines, bRSV continues to impact cattle operations worldwide as a sole agent or as a factor contributing to bovine respiratory disease. The immature immune system of dairy calves and lack of placental antibody transfer makes colostrum administration an essential practice to preserve calf health. However, presence of maternally derived antibodies, along with stressful management practices, hinders calves’ ability to respond to vaccination. The relationship between stressful management practices and the incidence of bovine respiratory disease has been well documented,29–31 allowing targeted use of prophylactic and therapeutic drugs or immunomodulators during critical disease susceptibility periods in cattle farms. A limited number of immunomodulators has been licensed for use in cattle in against respiratory disease, in an effort to reduce antimicrobial use.32 Here, we showed that both DMF and 4-OI exert antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects on bovine respiratory ECs during bRSV infection, suggesting their potential application to prevent bRSV disease. Moreover, we show that these agonists also promote anti-inflammatory and antiviral responses in hRSV-infected human ECs and provide partial clinical and virological protection against hRSV infection in a mouse model, suggesting their potential use against RSV disease in both humans and cattle.

In bRSV and hRSV-infected ECs, both 4-OI and DMF showed robust anti-inflammatory effects at the transcriptional level when administered 6 h before infection and then daily after infection (Fig. 2). Our results are in line with Olagnier et al.,24 in which suppression of inflammatory cytokine transcription was observed after DMF and 4-OI treatment SARS-CoV-2 and Sendai virus infection in vitro. Similarly, dimethyl itaconate (DI) and itaconate reduced cxcl10 transcription on A549 cells and human tissue explants during IAV infection. Pretreatment of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with 4-OI, DI, and itaconate reduced transcripts of tnf, il-6, and il-1β during IAV infection, with 4-OI showing the most potent suppressive effects in comparison with DI and itaconate.25 4-OI also reduced ccl5, il-8, il-6, and tnf in PRRSV-infected immortalized porcine alveolar macrophages (IPAMs).27 In our in vivo RSV model, we also observed reduced levels of IL-6 and il-6 transcripts in both DMF- and 4-OI–treated mice, as well as ccl5 and cxcl1, but not il-1β (Fig. 5C; Fig. S3). This was associated with reduced morbidity during hRSV infection (Fig. 4C), which is in line with reports in human infants, in which airway IL-6 levels have been correlated with disease severity.9,33 DMF and 4-OI both inhibit IL-1β production in several inflammation models by multiple mechanisms targeting nuclear factor κB signaling and the inflammasome, among others.34–36 While both 4-OI and DMF are considered NRF2 agonists and glycolysis inhibitors, they also have distinct effects on other pathways, and therefore identical effects on inflammation and antioxidant responses were not expected. Moreover, their effects on ECs have been less described. Olagnier et al.24 reported reduced IL-1β transcription in 4-OI–treated, SARS-CoV-2–infected Calu3 cells; however, the effects on this cytokine were milder compared with the reduction observed on ccl5 and tnf. It is likely that the timing of drug administration in our model accounts for the discrepancy between our in vitro and in vivo results on il-1β transcription, as well as for the difference between protection provided against lung damage. Quantification of protein levels would be a confirmatory approach to consider in future studies. Overall, our results add to the growing literature showing the immunomodulatory potential of both DMF and itaconate derivatives,34,37,38 further enforcing their potential application to prevent or reduce viral immunopathogenesis.

This anti-inflammatory response has been accompanied by DMF- and/or 4-OI–enhanced NRF2 signaling in the context of SARS-CoV-2 and PRRSV infection.24,27 Here, bRSV significantly reduced nrf2 levels but not NRF2-ARE–dependent enzyme transcription. However, NRF2 agonists were able to differentially increase transcription of some of these enzymes, suggesting that they activate the NRF2-ARE pathway in bovine ECs. DMF used at 200 μM/mL was also able to restore nrf2 transcription to basal levels and had a more robust effect in inducing AOE transcription. PRRSV and SARS-CoV-2 also impair nrf2 transcription, with a reduction in AOE transcription shown in the latter.24,27 Although DMF and 4-OI act on the KEAP1-NRF2 interaction level,39,40 4-OI has been shown to restore nrf2 transcription during PRRSV infection in IPAMs when administered for 24 h right after PRRSV infection.27 We did not observe this in our experiment, although several factors including time and duration of treatment may account for these differences. As mentioned previously, the NRF2-ARE pathway plays a role in regulating oxidative damage during hRSV and hPMV infection and recovery of antioxidant function has proven beneficial against RSV disease in murine models.19,20 Regarding bRSV, one report showed that BT cells increase transcription of several antioxidant genes after infection, including sod2, gpx1, hmox1, and others, suggesting the activation of an antioxidant program.41 Particularly, hmox1 transcription tended to increase 48 h after infection, with transcription increasing as infection progressed. Catalase was not significantly modulated at the transcriptional level after bRSV infection. Authors also analyzed ROS and antioxidant pathways across uninfected lung tissue and bRSV-infected lesion and nonlesion lung samples ex vivo and observed that bRSV pathology is characterized by a distinct oxidative transcriptional program, in line with previous findings discussed elsewhere. In our mouse model, we observed increased H2O2 levels 3 d after infection in RSV-infected, vehicle-treated animals but not in DMF- and 4-OI–treated animals when compared with uninfected, vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 5C), indicating that intranasal administration of NRF2 agonists modulated either formation of detoxification of this ROS. Together, our results suggest that DMF or 4-OI could be protective against RSV by promoting antioxidant responses.

Our in vitro assays indicate that both DMF and 4-OI reduce formation of infectious particles of bRSV and hRSV in ECs when administered before and during infection (Fig. 3A–D) despite a strong downregulation of ifnb1 (Fig. 2E, J), suggesting that their mechanism of action is independent of type I IFN signaling. Our results are in line with previous studies have showed that 4-OI and DMF strongly downregulate type I IFN responses to SARS-CoV-2 in ECs. Nonetheless, 4-OI reduces infectious titers of SARS-CoV-2, Zika virus, herpes simplex virus 1, and vaccinia virus by mechanisms yet to be elucidated. Both DI and 4-OI have been shown to reduce ifnb1 transcription in IAV-infected PBMCs, while only 4-OI treatment showed a reduction in IAV hemagglutinin messenger RNA in PBMCs. 4-OI also reduced infectious titers on A549 cells but not on hemagglutinin messenger RNA copies, suggesting antiviral effects at a posttranscriptional level. Recently, Ribó-Molina et al.42 reported that 4-OI reduces IAV replication by modifying a C528 of the chromosomal maintenance 1 protein, which is essential in mediating the export of IAV ribonucleoprotein complexes. They suggested that this mechanism could explain antiviral properties of 4-OI on other pathogenic viruses. Pang et al.27 showed that 4-OI interferes with the viral cycle at several levels, including virus attachment, replication, and export, although the exact mechanisms were not investigated. 4-OI interfered with PRRSV release when used 18 h postinfection. Our experiments also indicate that these drugs reduce infectious titers when used 24 h after infection (Fig. 3C, D). Therefore, the therapeutic use of 4-OI and DMF should be further investigated. In our in vivo model, we observed that both drugs significantly reduced lung viral copies; however, the mechanisms of action of these immunomodulatory drugs on the viral replication cycle will be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, DMF and 4-OI agonists promote transcription of antioxidant enzymes during bRSV infection, downregulate inflammatory responses and virus production in respiratory ECs during hRSV and bRSV infection, and are partially protective in a murine hRSV infection model. Our results warrant further investigation of the mechanisms of action of these immunomodulatory agents in the bovine species as well as their potential application in preventing or treating RSV in both ruminants and infants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Iowa State University Laboratory Animal Resources team for dedicated care of animals involved in this study.

Contributor Information

Fabian E Diaz, Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Preventive Medicine, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States.

Jodi L McGill, Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Preventive Medicine, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States.

Author contributions

F.E.D. and J.L.M.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation Visualization Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Fabian E. Diaz (Conceptualization [Equal], Data curation [Equal], Formal analysis [Equal], Funding acquisition [Equal], Investigation [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Project administration [Equal], Resources [Equal], Supervision [Equal], Validation [Equal], Visualization [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]) and Jodi L. McGill (Conceptualization [Equal], Data curation [Equal], Formal analysis [Equal], Funding acquisition [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Project administration [Equal], Resources [Equal], Supervision [Equal], Validation [Equal], Visualization [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal])

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at ImmunoHorizons online.

Funding

This work was supported by a U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture Capacity Grant.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Nair H et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mazur NI et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention within reach: the vaccine and monoclonal antibody landscape. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23:E2–E21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sigurs N et al. Asthma and allergy patterns over 18 years after severe RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life. Thorax. 2010;65:1045–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Silvestri M, Sabatini F, Defilippi AC, Rossi GA. The wheezy infant—immunological and molecular considerations. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5(Suppl A):S81–S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sacco RE, McGill JL, Pillatzki AE, Palmer MV, Ackermann MR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in cattle. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brodersen BW. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2010;26:323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith RA, Step DL, Woolums AR. Bovine respiratory disease: looking back and looking forward, what do we see? Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2020;36:239–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lukens MV et al. A systemic neutrophil response precedes robust CD8(+) T-cell activation during natural respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants. J Virol. 2010;84:2374–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McNamara PS, Ritson P, Selby A, Hart CA, Smyth RL. Bronchoalveolar lavage cellularity in infants with severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Childhood. 2003;88:922–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mutua V, Cavallo F, Gershwin LJ. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in a randomized controlled trial of a combination of antiviral and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory treatment in a bovine model of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2021;241:110323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cortjens B et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps cause airway obstruction during respiratory syncytial virus disease. J Pathol. 2016;238:401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Russell CD, Unger SA, Walton M, Schwarze J. The human immune response to respiratory syncytial virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:481–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hosakote YM, Liu TS, Castro SM, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Respiratory syncytial virus induces oxidative stress by modulating antioxidant enzymes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:348–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hosakote YM et al. Viral-mediated inhibition of antioxidant enzymes contributes to the pathogenesis of severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1550–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Komaravelli N, Ansar M, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Respiratory syncytial virus induces NRF2 degradation through a promyelocytic leukemia protein—ring finger protein 4 dependent pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;113:494–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Komaravelli N et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection down-regulates antioxidant enzyme expression by triggering deacetylation-proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88:391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ivanciuc T, Sbrana E, Casola A, Garofalo RP. Protective role of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 against respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus infections. Front Immunol. 2018;9:854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ivanciuc T et al. Micro-CT features of lung consolidation, collagen deposition and inflammation in experimental RSV infection are aggravated in the absence of Nrf2. Viruses. 2023;15:1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Espinoza JA et al. Heme oxygenase-1 modulates human respiratory syncytial virus replication and lung pathogenesis during infection. J Immunol. 2017;199:212–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ansar M, Ivanciuc T, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Increased lung catalase activity confers protection against experimental RSV infection. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castro SM et al. Antioxidant treatment ameliorates respiratory syncytial virus-induced disease and lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1361–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lebedev M et al. Analysis of lung transcriptome in calves infected with Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus and treated with antiviral and/or cyclooxygenase inhibitor. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hägglund S et al. Proteome analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage from calves infected with bovine respiratory syncytial virus-Insights in pathogenesis and perspectives for new treatments. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Olagnier D et al. SARS-CoV2-mediated suppression of NRF2-signaling reveals potent antiviral and anti-inflammatory activity of 4-octyl-itaconate and dimethyl fumarate. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sohail A et al. Itaconate and derivatives reduce interferon responses and inflammation in influenza A virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18:e1010219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Waqas FH et al. NRF2 activators inhibit influenza A virus replication by interfering with nucleo-cytoplasmic export of viral RNPs in an NRF2-independent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2023;19:e1011506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pang Y et al. Itaconate derivative 4-OI inhibits PRRSV proliferation and associated inflammatory response. Virology. 2022;577:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoerlein AB, Marsh CL. Studies on the epizootiology of shipping fever in calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1957;131:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gaudino M, Nagamine B, Ducatez MF, Meyer G. Understanding the mechanisms of viral and bacterial coinfections in bovine respiratory disease: a comprehensive literature review of experimental evidence. Vet Res. 2022;53:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Caswell JL. Failure of respiratory defenses in the pathogenesis of bacterial pneumonia of cattle. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:393–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGill JL, Loving CL, Kehrli ME. Future of immune modulation in animal agriculture. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2025;13:255–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kerrin A et al. Differential lower airway dendritic cell patterns may reveal distinct endotypes of RSV bronchiolitis. Thorax. 2017;72:620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peace CG, O'Neill LA. The role of itaconate in host defense and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2022;132: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peng H et al. Dimethyl fumarate inhibits dendritic cell maturation via nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) and mitogen stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK1) signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28017–28026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gillard GO et al. DMF, but not other fumarates, inhibits NF-κB activity in vitro in an Nrf2-independent manner. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;283:74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O'Neill LAJ, Artyomov MN. Itaconate: the poster child of metabolic reprogramming in macrophage function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yadav SK, Soin D, Ito K, Dhib-Jalbut S. Insight into the mechanism of action of dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis. J Mol Med (Berl). 2019;97:463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mills EL et al. Itaconate is an anti-inflammatory metabolite that activates Nrf2 via alkylation of KEAP1. Nature. 2018;556:113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Linker RA et al. Fumaric acid esters exert neuroprotective effects in neuroinflammation via activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Brain. 2011;134:678–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hofstetter AR, Sacco RE. Oxidative stress pathway gene transcription after bovine respiratory syncytial virus infection in vitro and ex vivo. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2020;219:109956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ribó-Molina P et al. 4-Octyl itaconate reduces influenza A replication by targeting the nuclear export protein CRM1. J Virol. 2023;97:e0132523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.