Abstract

The obligate intracellular protozoan pathogen Toxoplasma gondii is estimated to infect a third of the world’s population. Toxoplasmosis is considered a significant worldwide disease that can lead to morbidity or death in immunocompromised individuals. Host defense against T. gondii has been demonstrated to be dependent on a rapid myeloid cell and lymphocyte response working in concert to quickly eliminate the invading pathogen. Classically, T-bet–dependent group 1 innate lymphocytes (ILC1s), natural killer (NK) cells, and CD4+ T cell–derived interferon-γ (IFN-γ) are considered indispensable for host resistance against T. gondii. However, recent discoveries have illustrated that T-bet is not required for NK cell– or CD4+ T cell–derived IFN-γ. Yet, lack of T-bet still results in rapid mortality, pointing to a T-bet–dependent myeloid cell–mediated host defense pathway. This review summarizes the myeloid cell–mediated immune response against T. gondii and provides insights into the lesser known components of the T-bet–dependent myeloid cell–dependent host defense pathway for pathogen clearance.

Keywords: immunoparasitology, innate immunity, myeloid cells, T-bet

Introduction

The apicomplexan obligate intracellular parasite and the causative agent of toxoplasmosis, Toxoplasma gondii, can infect virtually all nucleated cells of warm-blooded animals, including humans. T. gondii transmission typically occurs from unintentional ingestion of feline fecal matter, foodborne transmission via undercooked meats or contaminated produce, and congenital transmission via infection during pregnancy that can lead to the parasite crossing the placental barrier and infecting the fetus. Approximately a third of the human population tests seropositive for the parasite, making T. gondii a global health burden and concern.

Following the consumption of the parasite, T. gondii will ultimately evade clearance and transform into slow-growing cysts within neurons and other tissues, leading to a lifelong infection.1 Notably, individuals that are chronically infected and develop an immunocompromised status due to medications (i.e. chemotherapy or radiation therapy), infection (i.e. HIV/AIDS), or cancer (i.e. leukemia, lymphoma, or multiple myeloma) will lead to reactivation of the parasite and uncontrolled parasite growth. Parasite reactivation can lead to toxoplasmosis encephalitis, resulting in brain inflammation and necrosis.

In immunocompetent individuals, T. gondii generally causes mild flu-like symptoms that typically go unnoticed and untreated. Mild symptoms caused by T. gondii are due to a rapid and robust type 1 immune response characterized by indispensable CD4+ T helper 1 (Th1) cell–derived interferon-γ (IFN-γ). The parasite-mediated Th1 response has been classically considered to be T-bet dependent, yet recent studies by our group and others have revealed that T-bet–independent natural killer (NK) cells, CD8+ T cells, and Th1 cells remain functional mediators of IFN-γ during acute infection.2,3 Despite the presence of NK-, CD8+-, and Th1-derived IFN-γ in the absence of T-bet, Tbx21-deficient mice rapidly succumb to T. gondii infection,3–5 suggesting a T-bet–dependent myeloid cell–mediated host defense pathway. This review examines the individual roles of myeloid cells in the innate immune response to T. gondii and aims to delineate how the transcription factor T-bet mediates myeloid cell–dependent host resistance against intracellular pathogens.

Myeloid cell–mediated host defense

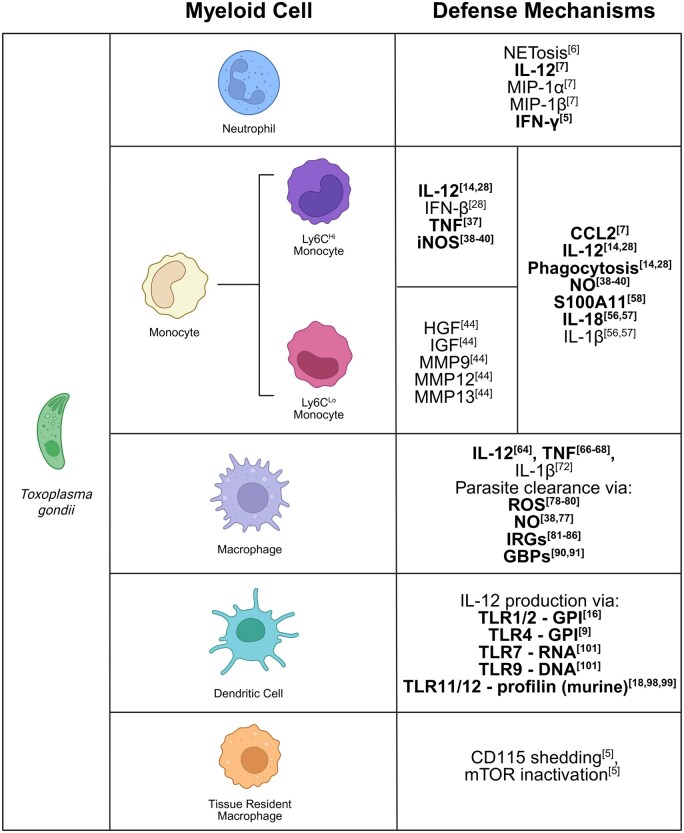

The innate immune system is comprised of specialized myeloid cells and lymphocytes, which work in concert to rapidly clear invading pathogens. T. gondii is a robust inducer of the type 1 immune response, defined by IFN-γ production, which is indispensable for host resistance during infection.6 Our group and others have shown that during the acute stage of T. gondii infection, myeloid cells must work in tandem with group 1 innate lymphoid cells (ILC1s), NK cells, and Th1 cells to generate a rapid and protective IFN-γ response. During T. gondii infection, the myeloid cells that have been shown to play key roles in host defense are neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and a recently identified subpopulation CD11c+MHCII− myeloid cells (Fig. 1).4 The transcription factor T-bet, encoded by Tbx21, has classically been defined as the master regulator of IFN-γ; however, our group recently showed that T-bet–expressing CD11c+MHCII− myeloid cells (TMCs) play an important role in host resistance during acute T. gondii infection.4 Determining T-bet’s role in myeloid cell–mediated innate defense is critical to further our understanding of the mechanisms that eliminate T. gondii and prevent the parasite’s progression to the host’s central nervous system (CNS), where it will ultimately establish a lifelong infection. Herein, we discuss the individual myeloid cells involved in mediating protective immunity against T. gondii to better our understanding of host defense against T. gondii and similar intracellular pathogens.

Figure 1.

Myeloid cells involved in innate defense against T. gondii. Myeloid cells, such as neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, DCs, and TRMs, employ a variety of defense mechanisms via cytokine production, chemoattractant release, and specialized antimicrobial mechanisms such as NETs, oxygen radicals, IRGs, and GBPs. This multifaceted functionality is critical for recruiting additional innate immune cells, initiating trained immunity, priming of the adaptive immune response, and ultimately, rapid parasite clearance. While the protective measures for each cell type vary greatly, overlap in overall function of such measures between multiple cell types highlights the need for redundant processes to ensure host survival. Emboldened text indicates pathways that have been established as directly relevant to host defense against T. gondii. Created in BioRender (https://biorender.com/c91w081).

Neutrophils

Neutrophils have been well-studied in host defense against numerous microbial pathogens and are critical first responders to infection. They have been proven to provide several unique antiparasitic mechanisms contributing to host defense against T. gondii. A key antimicrobial function of neutrophils is the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), weblike structures composed of DNA fibers, histones, and antimicrobial proteins that have been demonstrated to play a role in trapping viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoans.7 To elucidate the role of this specialized antimicrobial mechanism, in vitro examination of fully functional neutrophils acting against tachyzoites was compared with neutrophils with DNase-deactivated NETs.7 This study illustrated that NETs provide an important defensive mechanism against T. gondii via a mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase, independent of the MyD88 pathway.7 These data suggest that NETs are able to kill the parasite due to its entrapment and subsequent inability to enter host cells, leaving T. gondii unable to harvest nutrients and proliferate.7 Although this mechanism provides a hypothesis for parasite elimination, the specific mechanism for NET-mediated parasite death remains unknown, and further studies are needed to elucidate the significance of NETs during T. gondii infection in vivo.

Additional studies have shown that neutrophils are a notable source of interleukin (IL)-12, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), MIP-1α (macrophage inflammatory protein 1α) (also known as CCL3), and MIP-1β (also known as CCL4), which are expressed independent of pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) recognition via Toll-like receptors (TLRs).8 These proinflammatory cytokines were demonstrated to play a key role in the recruitment of macrophages to the site of infection and in T cell activation.9 Moreover, murine neutrophils are capable of recognizing T. gondii surface GPI (glycosylphosphatidylinositol) anchors via TLR2, generating the production of CCL2, which is critical for monocyte recruitment.8 However, TLR2-deficient mice remain capable of initiating a protective immune response against T. gondii, signifying that TLR2 plays a limited role for host defense against the parasite.10

Early studies utilizing Cxcr2-deficient mice set out to investigate the role of neutrophils in host defense against an acute intraperitoneal (i.p.) T. gondii infection. The absence of CXCR2 resulted in defective neutrophil recruitment and an increase in parasite burden at the site of infection.11 Yet, CXCR2 is also expressed on basophils, monocytes, macrophages, NK, NKT, and T cell subsets. This suggests conclusions from studies utilizing Cxcr2−/− mice could overexaggerate the role of neutrophils in host defense against T. gondii. Thus, to clarify the importance of neutrophils in host resistance against T. gondii, experimentation involving the depletion of neutrophils was necessary. By performing antibody mediated depletion using RB6-8C5 (GR-1), studies concluded that neutrophils are essential for innate defense against the protozoan parasite as GR-1 treated mice showed significant decreased cytokine expression, diminished T cell recruitment, and increased parasite burden.12,13 However, these interpretations were skewed due to this initial use of the GR-1 antibody, which binds not only the neutrophil-specific antigen, Ly6G, but also additional Ly6 family members, including Ly6C, a classic monocyte marker.14 To distinguish the individual role of neutrophils and monocytes during acute T. gondii infection, further studies were conducted by depleting neutrophils with the monoclonal antibody 1A8, which is specific to Ly6G.15 Neutrophil depletion using 1A8 showed nearly complete loss of Ly6G+ neutrophils while maintaining Ly6CHi monocytes and were able to control parasite replication with no change in host susceptibility.15 Meanwhile, mice administered GR-1 showed depletion of both Ly6G+ neutrophils and Ly6CHi monocytes, with a significant increase in parasite burden and rapid host mortality, suggesting that while neutrophils play a limited role in host defense, monocytes are an indispensable cell type for host resistance against T. gondii.15 Utilizing Ccr2−/− mice, which demonstrated a lack of monocyte recruitment with no neutrophil defect, resulted in uncontrolled parasite replication and rapid host mortality, establishing that neutrophils play a limited role in host resistance against T. gondii infection.15

More recent studies have shown that neutrophils are capable of expressing IFN-γ during their development under homeostatic conditions.16 It has also been established that neutrophil-derived IFN-γ is TLR- and IL-12-independent; yet, IFN-γ secretion by neutrophils requires microbial or inflammatory environment-mediated degranulation of primary granules containing IFN-γ.16 Host defense against T. gondii is dependent on the TLR and IL-1R adaptor molecule MyD88, which is required for inducing IFN-γ in NK and T cells.10,17,18 Lack of MyD88 or IFN-γ results in rapid host mortality; however, in the absence of TLR11, the sensor for profilin recognition, the host remains resistant to T. gondii infection.19,20 Meanwhile, in the human genome, TLR11 is a pseudogene and nonfunctional.21 Strikingly, depletion of NK cells or T cells from Tlr11−/− mice did not affect overall IFN-γ production.16 Utilizing lymphoid-deficient (Rag2−/−γc−/−) mice it was identified that neutrophils are a critical source of IFN-γ during T. gondii infection and in the absence of TLR11 neutrophil-derived IFN-γ is essential for host resistance against parasitic infection.22 These results provide a potential mechanism for the human immune response against the parasite, wherein TLR11 is nonfunctional, as it is demonstrated that in the absence of TLR11-dependent IL-12 lymphocyte activation, neutrophil-derived IFN-γ is essential for host immunity during acute T. gondii infection.22

As previously mentioned, humans lack a functional version of TLR11 and completely lack TLR12 from their genome, suggesting that neutrophils could play an expanded role in human resistance against the parasite.21 During acute infection with T. gondii, human neutrophils are activated upon exposure to tachyzoites in vitro, leading to an increased expression of cell surface markers. Such markers include CD66b, CD11b, CD15, CD62L, and CD88, along with increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and decreased expression of CD62L, all indicative of neutrophil activation.23 NET release also occurred after active tachyzoite coculture with human neutrophils, confirming that T. gondii mediates the release of neutrophil-derived NETs.23 It was further demonstrated that supplementing human neutrophils with IL-12 was sufficient to induce IFN-γ production, building on in vivo studies conducted utilizing Nocardia asteroides and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium).24–26 Additionally, human neutrophil–derived IFN-γ could be further augmented with the addition of IL-2 and IL-15, indicating that neutrophil-derived IFN-γ in humans may play a more significant role in immunity against T. gondii than their TLR11-sufficient murine counterparts.24 While neutrophil-mediated host defense against T. gondii plays a limited role in murine survival, studies on the role of neutrophils in humans could open new avenues for initiating protective responses against this global protozoan.

Monocytes

Monocytes are critical sentinels of the innate immune system that provide a rapid response to microbial infections. Following the immediate infection with T. gondii, monocytes are produced in the bone marrow via IL-6 signaling.27 Emergency myelopoiesis is stimulated, and through priming via peripheral NK cell–derived IFN-γ, monocytes egress from the bone marrow and are subsequently recruited to the site of infection.28,29 Traditionally, monocytes are classically thought to be precursors to both macrophages and DCs, termed monocyte-derived macrophages and DCs; however, murine studies have shown that these cell types differentiate independently of monocytes, while monocytes develop into their own dynamic phagocyte-related cells.30–32 These monocytic derivations contribute to various physiological processes in ways that mimic both macrophage and DC activity.

In mice, there are two primary subsets of monocytes: classical (inflammatory) Ly6CHi CCR2HiCX3CR1Lo and patrolling Ly6CLoCCR2LoCX3CR1Hi. Inflammatory Ly6CHi monocytes are well characterized, known to be rapidly recruited to the site of infection, and critical for host defense against T. gondii. In the setting of an acute mucosal T. gondii infection, uncontrolled expansion of Gram-negative bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family mediates significant intestinal immunopathology,33–36 and the resulting host response leads to rapid recruitment of neutrophils in order to limit commensal interaction with the intestinal epithelium,35 which is regulated by Ly6CHi inflammatory monocytes in a prostaglandin E2–dependent manner.37 In addition to being key regulators of neutrophil-mediated pathology during T. gondii infection, Ly6Chi monocytes are also critical for host resistance due to their antiparasitic effector mechanisms, including IL-12, IFN-β, and TNF production; phagocytosis; and upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).15,29,38 iNOS generates NO a toxic metabolite that deprives T. gondii, an arginine auxotroph, of arginine, rendering the pathogen incapable of undergoing replication.39–41 While it has been shown that iNOS plays a limited role during acute infection, additional studies show that iNOS production is important for host defense during the chronic stage of infection, where mice succumbed to infection and possessed a much higher parasite burden.42 NO-dependent mechanisms have been indicated to be critical for host defense orchestrated by microglia in the CNS, as demonstrated by the presence of T. gondii in microglia treated with an NOS inhibitor.42,43

As Ly6CHi monocytes maintain host defense against T. gondii, they are also precursors to patrolling Ly6CLo monocytes. The comparatively longer-lived Ly6CLo monocytes reside in tissues to ensure epithelial integrity and utilize a “rolling” motion to patrol vasculature and rapidly respond to infection.44 Patrolling monocytes have been found to be continually present within the vasculature and can rapidly extravasate upon recognition of inflammatory chemokines. Ly6CLo patrolling monocytes are key in anti-inflammatory and healing processes. They inhibit the inflammatory response via anti-inflammatory mechanisms such as engulfing apoptotic T cells and inhibiting T cell function through anti-inflammatory factors and high-mobility group box 1 (CD52-HMGB1) binding.45 During the phagocytic process, Ly6CLo cells produce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), such as MMP9, MMP12, and MMP13, accelerating extracellular matrix degradation and inhibiting fibrosis.45 During tissue repair and reconstruction, Ly6CLo cells secrete hepatocyte growth factor and insulin-like growth factor to promote wound healing and tissue regeneration.45 Furthermore, it has been shown that patrolling monocytes play a critical role in preventing lung tumor metastasis via recruiting and activating NK cells.46 Additional studies are needed to define the wide breadth of patrolling monocytes' functionality to better understand their role in the innate immune system for microbial host defense.

Recent results have revealed that during T. gondii infection, there is a significant increase of Ly6CLo monocytes in the blood, CNS, and tissues that had yet to be infected, suggesting that patrolling monocytes play an important role in protecting host tissues during acute toxoplasmosis.47 Additional studies have shown that the T. gondii–derived protein kinase ROP17 can contribute to the migration of monocytes to sites of infection via ROCK (Rho-associated kinase) signaling, indicating a parasite-dependent and independent mechanism to the recruitment and migration of monocytes to different sites of infection.48 E2−/− or Nur77 knockout mice, which lack patrolling monocytes, can help us understand how patrolling monocytes defend against T. gondii in future studies.46,49

An important contribution to host protection is the monocyte’s ability to develop trained immunity. This form of immunity is hypothesized to involve activation via plasma-soluble transfer factors or cytokines such as IL-1 or TNF.50 While the mechanistic qualities of trained immunity remain unclear, a possible route could involve reprogramming the transcriptional profile of the cell in a manner similar to TLR-induced chromatin modifications.51 In vivo studies have illustrated that cellular promoters exhibit transcription factor recruitment, increased histone acetylation, H3K4 trimethylation, and chromatin remodeling upon initial exposure to lipopolyaccharide.51 The high H3K4 trimethylation with increased levels of histone acetylation and accessibility upon secondary exposure leads to faster kinetics and a more efficient innate immune response downstream of accelerated transcription of antimicrobial genes.51 Bridging the gap between innate and adaptive immunity, this process of trained immunity involves a more effective second-exposure response to pathogens without the somatic diversification present in the adaptive immune cells. An early study suggested the effect of “trained immunity” against T. gondii using CBA mice treated with muramyl dipeptide (MDP).52 MDP is recognized by NOD2 signaling through nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), which stimulates epigenetic rewiring of macrophages and induces trained immunity.53,54 This study shows that independently of enhanced anti-Toxoplasma antibodies, treating mice with MDP prior to infection with T. gondii lowered mortality rates,52 suggesting that another form of developed immunity to the pathogen, with trained immunity as a possibility.50 Further studies with soluble tachyzoite antigen (STAg) or T. gondii–derived profilin could prove to be effective in determining the nature of monocytic trained immunity against T. gondii.

Inflammasome recognition of intracellular pathogens is essential for innate defense as we have shown with S. Typhimurium and T. gondii.20,55 The inflammasome working in tandem with TLRs provides another aspect of monocyte-mediated host protection. Through the NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes, the adaptor molecule apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) is recruited that is essential for caspase-1 and caspase-11 activation, which then converts pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their biologically active forms.20,56,57 While the inflammasome has been established as indispensable for host defense against S. Typhimurium, our group and others have demonstrated that individual inflammasome components, NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 and caspase-11 play a limited role in host resistance during T. gondii infection.20,58,59 TLR11/12 recognition of T. gondii profilin initiates a robust MyD88-dependent, DC-derived, IL-12–mediated immunity against the parasite. However, in the absence of TLR11, mice do not demonstrate acute susceptibility, suggesting another innate protective pathway being concealed by a robust TLR/IL-12 response. Our group illustrates that in the absence of TLR11, it is IL-18 and not IL-1β that plays a critical role for Th1-mediated immunity during T. gondii infection.20 Additionally, a recent study demonstrates that it is the caspase-1–dependent release of IL-18 from Cx3cr1+ myeloid cells that plays a critical role in mediating Th1 effector function during T. gondii infection.59 Monocytes, macrophages, DCs, and microglia all express Cx3cr1 and have all been shown to play a vital role for myeloid cell–mediated defense against T. gondii, hence additional studies are needed to clarify the precise subpopulation of Cx3cr1+ cells, which are critical for innate inflammasome-dependent immunity.

It is important to note the suggested greater importance of inflammasome functionality in the context of human disease. During human T. gondii infection, IL-1β, a critical regulator of inflammation, is produced and secreted by monocytes in greater frequencies than IL-18, suggesting IL-1β having great impact on human monocyte-mediated immunity against T. gondii.60,61 Recent findings from the Yarovinsky group show that caspase-1 in human monocytes mediates the release of S100A11 from infected cells via the RAGE signaling pathway, triggering CCL2 production.62 These results highlight that monocyte infection by T. gondii is essential for a caspase-1–dependent, CCL2-mediated host defense mechanism. Utilizing S100a11-deficient mice, it was established that in vivo S100a11 promotes CCL2-mediated monocyte recruitment to the site of infection and significantly contributes to host survival.62

Studies investigating the T. gondii ligand recognized by the inflammasome have shown that neither heat-killed T. gondii nor mycalolide B–treated, invasion-inhibited parasites can induce IL-1β release,20,60 indicating that active cellular invasion is necessary for inflammasome activation. It was identified that in bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) from Lewis rats, NLRP1-dependent pyroptosis is mediated by direct infection and the parasite-dense granule proteins GRA35, GRA42, and GRA43.63 In human THP-1 monocyte cells infected with T. gondii, the AIM2 inflammasome sensor has been shown to be activated by T. gondii DNA that has been liberated by guanylate-binding protein (GBP) activity.64,65 It has also been shown using primary mouse peritoneal macrophages and BMDMs that NLRP3 was activated by extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) signaling released from parasite-infected cells via the P2X7 receptor.66 Additionally, the dense granule protein, GRA15, from type II strains of the parasite, plays an important role for IL-1β release in both human monocytes and mouse BMDMs.60,67 Thus, the inflammasome component of monocyte-derived host defense could provide further clarification on human host defense mechanisms. Monocytes play an indispensable role in host defense against T. gondii by controlling parasite replication and facilitating innate recognition, which is critical for recruiting additional immune cells. Additionally, there is a significant gap in understanding the role of monocytes in parasite clearance during human infection due to the rapid immune response and the absence of T. gondii–specific clinical symptoms. Therefore, as we continue to understand the role of monocytes using the toxoplasmosis mouse model, it is necessary to simultaneously define the effector functions of human monocytes during acute infection.

Macrophages

Macrophages play a central role in T. gondii clearance via multiple mechanisms including innate pathogen recognition, production of proinflammatory cytokines, NO, ROS, and induction of IFN-γ–mediated antiparasitic pathways. Early studies indicated that macrophages were a critical source of IL-12 during T. gondii infection,68 which mediated ILC-derived IFN-γ production. Murine studies have now established that the primary source of IL-12 during acute toxoplasmosis infection is produced by type I conventional DCs (cDC1s) through T. gondii profilin–activated TLRs 11/12.17,19,69 Further reports have linked additional T. gondii–derived PAMPs to inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages. T. gondii’s GPI and heat shock proteins have been shown to be recognized by TLR2 and TLR4 in macrophages, resulting in TNF and IL-12 production.70–72 Yet, studies demonstrate that TLR2 and TLR4 play a limited role in host defense, as Tlr2−/− and Tlr4−/− mice have no defect in CD4+ T cell–derived IFN-γ or effect on host survival.70,71 Additionally, it has been observed, using immortalized macrophages, that macrophages are capable of sensing T. gondii RNA via TLR7.73 Similar to TLR2 and TLR4 deficiency, lack of TLR7 does not confer susceptibility to T. gondii infection, nor does it result in an increase of tissue cysts.73 In the mouse model of toxoplasmosis, TLRs 2, 4, 7, and 9 appear to play a limited role in host resistance against T. gondii when TLR11 and TLR12 are intact. However, in the absence of TLR11, TLRs 3, 7, and 9 become essential for host defense during acute infection,69 indicating that in the absence of TLR11, non–profilin-recognizing TLRs play an important role for innate immunity toward T. gondii.

In addition to TLRs, macrophages are also capable of sensing T. gondii via the inflammasome. As previously stated, T. gondii can be recognized by both the NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes, mediating IL-1β and IL-18 production, in vitro and in vivo, respectively.67,74 In vivo studies of inflammasome-mediated protection have contradicting results, some studies indicate that the inflammasome is critical for limiting parasite replication and host survival,67 and others, including our group, have shown that the inflammasome plays a limited role in mediating CD4+ T cell–derived IFN-γ response and host resistance.20,58 Nevertheless, our previous findings identify that in the absence of TLR11, the inflammasome plays a significant role in mediating a robust Th1 response, most likely due to the significant upregulation of IL-18 observed in Tlr11−/− mice during acute infection.20 It has also been reported that caspase-8 plays an important role in controlling the transcription of Il12b and Il1b, and mice lacking caspase-8 rapidly succumb to parasitic infection.75 Another reported mechanism of inflammasome-mediated host defense is the purinergic receptor P2X7R, an ATP-gated plasma membrane ion channel known to play a role in a wide range of host defense processes.76 P2X7R leads to the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β secretion.76 Moreover, it was demonstrated, using macrophages, that in the absence of P2X7R, ATP-mediated parasite killing is significantly diminished.77

Early experiments utilizing human macrophages revealed that IFN-γ–mediated toxoplasmacidal activity is critical for the clearance of intracellular parasites.78 IFN-γ–primed murine macrophages are classically considered proinflammatory M1 macrophages capable of limiting T. gondii replication within the parasitophorous vacuole (PV).79 Furthermore, it was demonstrated that macrophages isolated from AIDS patients, when stimulated with IFN-γ, could eliminate intracellular T. gondii, demonstrating that these individuals had functional macrophages that are able to eliminate the parasite.80 Hence, IFN-γ–mediated macrophage-dependent cellular immunity plays a significant role in host resistance against T. gondii infection, with 5 major mechanisms triggered by IFN-γ. These IFN-γ induced mechanisms include (i) iNOS expression, depleting arginine via NO synthesis, starving T. gondii; (ii) ROS intermediates, which have been demonstrated to eliminate intracellular T. gondii in both IFN-γ–dependent and IFN-γ–independent pathways; (iii) inducible immunity-related GTPases (IRGs); (iv) p65 GBPs; and (v) IFN-γ–dependent and tissue-resident macrophage (TRM) cell death mediated via CD115 and the mTOR pathway. Similar to monocytes, macrophages utilize IFN-γ to induce expression of iNOS, depleting arginine via NO synthesis, starving T. gondii.39,81 ROS intermediates have also been demonstrated to eliminate intracellular T. gondii in both IFN-γ–dependent and IFN-γ–independent pathways.82–84 Thus, reasoning that in the absence of robust IFN-γ production, macrophages may remain capable of eliminating intracellular T. gondii via ROS production.

Another critical set of IFN-γ–inducible proteins are IRGs and p65 GBPs. IRGs including IRGM1 (also known as LRG47),85 IRGM3 (also known as IGTP),86,87 IRGD (also known as IRG47),85 IRGA6 (also known as IIGP1),88 and IRGB6 (also known as TGTP)89,90 all contribute to host-mediated defense and parasite clearance. GBPs are now understood to play a critical role in the recruitment of IRGs to the PV,91,92 leading to vesiculation of the PV membrane and, ultimately, parasite elimination. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the autophagy protein ATG5 is required for IFN-γ–inducible IRGA6 recruitment to the PV membrane, mediating parasite clearance in the macrophage.93 Similarly, we have also demonstrated that ATG5 expression within Paneth cells is indispensable for tissue homeostasis in response to T. gondii infection, and the lack of ATG5 in either phagocytes or Paneth cells results in rapid host susceptibility.93,94 A limitation of the translational significance of IRG-related studies in mouse models is that 23 IRG genes are encoded in the mouse, whereas humans only retain one full-length IRG.95 Meanwhile, mice and humans possess 11 and 7 GBPs, respectively.92,96,97 Furthermore, it has been shown that murine GBP2 (mGBP2) targets the PV and promotes the recruitment of mGBP7 to elicit their antiparasitic function.98 It is important to note that the human orthologue of mGBP2, human GBP1 (hGBP1), has also been observed promoting the recruitment of hGBP2, hGBP3, hGBP4, and hGBP6 to Shigella in HeLa cells, demonstrating that GBP’s antimicrobial functions are conserved between different species.99,100

More recently, the role of TRMs has been explored in the context of T. gondii infection. These data suggest that the parasite-mediated immune response leads to TRM elimination in the peritoneal cavity, liver, and intestines during acute parasitic infection.6 TRM elimination was shown to be IFN-γ dependent and TRM cell death mediated via CD115 and the mTOR pathway, which appears to be a critical to remove a replicative niche of the parasite.6,101 Together, these data illustrate the multiple pathways that macrophages may utilize in actively eliminating the microbial niche and killing intracellular pathogens.

Dendritic cells

As the classical antigen-presenting cells, DCs are drivers of the formation of the adaptive immune response. However, their primary role in innate immunity against T. gondii is initiating the IFN-γ–dependent immune response against the parasite. Early murine studies demonstrated that the adaptor molecule MyD88, which is downstream of most TLRs and IL-1 receptors, is critical for IL-12 production during T. gondii infection.10 It was then established using the mouse model of toxoplasmosis, T. gondii profilin is recognized by DCs via TLR11 and TLR12, mediating downstream MyD88- and UNC93B1-dependent signaling, critical for robust IL-12 production and IL-12–dependent Th1 effector function.19,102,103 It was then confirmed that TLR11 and TLR12 can both directly bind to profilin to form a heterodimer complex that also requires the presence of transcription factor IFN regulatory factor 8 (IRF8) for IL-12 production, rather than NF-κB signaling cascade.103 It is important to keep in mind, that unlike in mice, humans lack a functional TLR11 and completely lack TLR12 from their genome21; yet, humans that become infected with T. gondii are relatively resistant and typically asymptomatic to T. gondii infection, unless patients become immunocompromised. Recently, it was also shown that the transcription factor IRF5 also plays a role in IL-12 production by DCs and host resistance.104 However, it remains unclear if IRF5 is critical for all endosomal TLR recognition of T. gondii or is limited to TLR7 and TLR9, which has been observed in plasmacytoid DCs.105 Additional studies will be needed to dissect the role of IRF5 and IRF8 in cDC1-derived IL-12 production and host-mediated resistance.

Even though multiple myeloid cell populations can recognize T. gondii via TLRs (as described previously), multiple TLRs must work in concert to recognize T. gondii and induce a robust IL-12–dependent host immune response. The current innate immune signaling paradigm shows that the lack of MyD88 signaling in DCs using selective deletion largely recapitulates T. gondii infection in whole body Myd88−/− mice,17 establishing the significance of DC TLR-MyD88-dependent recognition of the parasite to mediate host defense. Shortly after the need for MyD88 expression in DCs was observed, it was shown in murine studies that CD8a+ DCs are the primary source of IL-12 following STAg administration.106 It was then confirmed by us and others that CD8a+Batf3+IRF8+ cDC1-derived IL-12 is critical to initiate a robust IL-12–dependent ILC1-, NK-, and Th1-derived IFN-γ response.69,107,108 Meanwhile, it has been demonstrated that a subset of KLF4-expressing cDC2s do not play a major role in controlling parasite replication or host survival.109 Overall, these in vivo studies demonstrate that IRF8+ cDC1s are critical in mediating host resistance against T. gondii and cDC2s play a lesser role in host defense against the parasite.

Recently, our group demonstrated that T-bet–dependent ILC1-derived IFN-γ, and to a lesser extent NK cell–derived IFN-γ, play a major role in maintaining inflammatory IRF8+ cDC1s during T. gondii mouse i.p. infection model and restricting parasite growth in peripheral tissues.108 Following this study, we investigated whether ILC1s were required for host immunity during T. gondii infection. Surprisingly, Tbx21−/− mice, which lack ILC1s and retain NK, T, and B cells, succumbed significantly quicker to infection than Rag2−/−γc−/− mice, that lack all lymphocytes, suggesting that T-bet–expressing myeloid cells play a role in parasite elimination and overall host defense.4 Our group recently demonstrated that IL-12 is required for mediating a subpopulation of TMCs. In the following section, we examine the known role of T-bet in mediating immunity against T. gondii and the precedence for a T-bet–expressing myeloid cell population to assist in host resistance against infectious disease.

T-bet–mediated immunity against T. gondii

T. gondii infection mediates a robust type I immune response defined by the effector functions of lymphocytes, including ILC1s, NK cells, and CD4+ Th1 cells.102,110–116 The transcription factor T-bet, encoded by Tbx21, is considered essential for the development and function of ILC1s, NK cells, and CD4+ Th1 cells.110,117–119 Classically, T-bet has been considered the master regulator of IFN-γ expression by CD4+ Th1 cells.117 However, our group and others have shown that T-bet is not required for parasite-mediated NK cell–, CD8+ T cell–, or Th1-derived IFN-γ, demonstrating that T-bet is largely dispensable for overall IFN-γ production2,34,108 [For an in-depth review of T-bet’s function in lymphocytes, see Harms Pritchard et al.5]. Our group was the first to demonstrate a role for T-bet in myeloid cell–mediated host defense against T. gondii (Fig. 2)4; however, identifying T-bet expression in myeloid cells is not uncommon. Preceding reports have demonstrated that T-bet expression in DCs may be upregulated in response to IFN-γ.120 Moreover, T-bet expression in DCs has been shown to play a role in controlling inflammatory arthritis, priming of antigen-specific T cells, CpG DNA adjuvancy, and IFN-γ production.121–123 Seminal studies examining the role of T-bet in innate immunity in the absence of T and B cells led to significant findings demonstrating that T-bet expression within DCs is critical to limit their TNF production.124,125 Moreover, in the absence of T-bet–expressing DCs, as well as T and B cells, the host will develop spontaneous communicable ulcerative colitis that will progress to colonic dysplasia and rectal adenocarcinoma due to MyD88-independent intestinal inflammation.124,125 Moreover, if the host’s DCs are engineered to overexpress T-bet in the absence of T and B cells, these mice displayed a significant reduction of neoplasia. In parallel to the role T-bet plays in restricting DC-derived TNF, recent results have identified two major cDC2 subsets that differentially express T-bet and RORγt, cDC2A, and cDC2B, respectively.126 In agreement with previous reports, T-bet–expressing cDC2As are anti-inflammatory and RORγt+ cDC2Bs are proinflammatory, expressing TNF and suggesting that in the absence of T-bet cDC2s will default to TNF expressing RORγt+ cDC2Bs exacerbating colonic inflammation.126 Additional studies are needed to confirm if Tbx21−/− mice only have cDC2Bs.

Figure 2.

T-bet–mediated host defense during T. gondii infection. The transcription factor T-bet is critical for host survival. Here we illustrate the involvement of T-bet in the host immune response against T. gondii. Recognition of the parasite by myeloid cells, via TLRs and NLRs, contributes to a robust protective response, maintained through production and release of IL-12 and IL-18. The effector function of T-bet–dependent ILC1s and NK cells is dependent on myeloid cell–derived IL-12 and IL-18. T-bet orchestrates the innate immune response through expression in ILC1s, NK cells, Th1 cells, and a recently defined population of TMCs, that are mediated by IL-12. While additional innate immune cells are required for overall host survival, recent studies have demonstrated that mice conditionally lacking T-bet within CD11c+ cells succumb to infection at the same rate as Tbx21−/− mice, suggesting that TMCs may play a crucial role in host defense. Upregulation of IFN-γ is another critical component of host defense; its classical production by ILC1s, NK cells, and Th1 cells. A novel finding of neutrophil-derived IFN-γ provides a method for production of this cytokine in a TLR- and IL-12–independent manner. IFN-γ also promotes TRM cell death, a protective measure aimed at limiting parasite replication within the phagocyte population. Created using BioRender (https://BioRender.com/x12o358).

An unpublished observation from the Glimcher group125 and our own recent results indicate that not only macrophages, but also Ly6G+ neutrophils, Ly6CHi monocytes, and DCs have limited T-bet expression. Unexpectedly, we observed a unique subpopulation of T-bet expressing CD45+CD3−CD19−Nkp46−F4/80−Ly6CLoLy6G−CD11c+MHCII− myeloid cells, which we have termed TMCs, which had the largest intracellular parasite burden within the peritoneum following an i.p. infection relative to other professional phagocytes, suggesting they are critical for T. gondii elimination. Additionally, we have observed TMCs in the small intestinal lamina propria and spleens of infected mice following a mucosal infection.4 Further studies are needed to determine if TMCs in the lamina propria also have the highest frequency of parasite burden during acute T. gondii infection. To better delineate if these TMCs are a subpopulation of an established myeloid cell, we have performed cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes (CITE-Seq) from peritoneal leukocytes on day 5 of i.p. T. gondii infection. From this, we observed that both DCs and Ly6CLo-neg monocytes have robust T-bet expression compared with neutrophils, Ly6CHi monocytes, and macrophages (Fig. 3). These observations indicate that during T. gondii infection there are two primary populations of T-bet–expressing myeloid cells, DCs, and Ly6CLo-neg monocytes. Following these results, the indicated populations are potentially (i) downregulating major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII), (ii) downregulating Ly6C and upregulating CD11c, or (iii) a novel subpopulation of circulating T-bet–expressing Ly6C Lo-neg patrolling monocytes. In the following section, we examine each of these possibilities and propose potential experiments to test them. (i) As we have discussed, there is extensive literature that DCs, specifically cDC2As, express T-bet, and in the absence of T-bet the host displays uncontrolled DC-derived TNF production that can ultimately result in neoplasia.124,125 Additionally, it has been demonstrated that antigen-presenting cells (APCs) infected with T. gondii will lead to the downregulation of MHCII, possibly leading to the T-bet+CD11c+MHCII− population we have observed.127,128 Yet, this is unlikely based on our results using T-bet reporter mice, which indicate there is no gradient of either MHCII or T-bet expression during infection. To determine if TMCs are derived from MHCII+ APCs a bone marrow (BM) chimera model could be utilized. As antigen presentation is critical to develop a robust immune response, we will transfer BM from LysM- and CD11c-Cre mice crossed with MHCIIfl/fl to conditionally delete MHCII from neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages (M-MHCII−/−), or DCs and TMCs (CD11c-MHCII−/−). We will use B6 CD45.1 as recipients and transfer BMs of M-MHCII−/− + B6 CD45.2 (M + B.2→B.1) or CD11c-MHCII−/− + B6 CD45.2 (CD11c+B.2→B.1). Eight weeks following the transplantation, we will infect M + B.2→B.1, CD11c+B.2→B.1, M-MHCII−/−, CD11c-MHCII−/−, and B6 CD45.1 with 20 cysts i.p. and by flow cytometry on day 5 postinfection assess the presence of TMCs from the peritoneum. We anticipate that we will not observe any defect in the frequency or total cell number of TMCs at day 5 postinfection from the infected transplant groups or the B6 controls. Additionally, we expect that conditionally deleting MHCII expression from APCs using either M-MHCII−/− or CD11c-MHCII−/− mice will result in a significant defect in the Th1 effector response, resulting in an increase in pathogen burden, and as a result will display significantly attenuated frequency and absolute cell numbers of TMCs during infection. (ii) Studies have demonstrated that during Leishmania and T. gondii infection, Ly6C+ monocytes downregulate Ly6C and upregulate CD11c.129,130 During T. gondii infection, myeloid cells were able to be differentiated as Ly6CintCD11c+MHCI+MHCII+ and Ly6C−CD11c+F4/80+TREM2+, suggesting they take on DC-like characteristics and have elevated phagocytic capability, respectively.129 Hence, the previously described Ly6C−CD11c+F4/80+TREM2+ monocytes could be the TMCs that we have observed, but based on our gating strategy that excludes F4/80+ cells, it is doubtful that these are the same population. To determine if TMCs differentiate from Ly6C+ monocytes, we have generated LysM-Cre x Tbx21fl/fl (M-Tbx21−/−) mice, conditionally deleting T-bet expression from neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. Our previous findings demonstrate that conditional deletion of T-bet in neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages did not lead to increased parasite burden or accelerated host mortality during infection.4 However, conditionally deleting T-bet from CD11c+ cells resulted in a significant increase of parasite burden at the site of infection compared with T-bet–sufficient mice.4 We have also observed (unpublished observation) that infected M-Tbx21−/− mice displayed no defect in the frequency or absolute cell numbers of TMCs compared with wild-type controls on day 5 postinfection. These preliminary observations suggest that TMCs are not differentiated from Ly6C+. As Ly6CLo monocytes are not solely derived from downregulating Ly6C,131 these results suggest another pathway for TMC development via the common monocyte progenitor (cMoP). (iii) Patrolling Ly6CLoCCR2LoCx3cr1Hi monocytes have been described as the myeloid population that “patrol” the host’s vessels during healthy conditions, and during tissue damage or infection they are capable of rapidly responding to the insult and differentiating into macrophages.131 Recently, it was observed that there is a significant increase of Ly6CLo monocytes in both the blood and the brain during acute T. gondii infection,47 and in our own studies, it appears that Ly6CLo monocytes, potentially TMCs, enter the peritoneum rapidly and play a critical role in host defense against T. gondii. Moreover, based on our CITE-seq observations (Fig. 3), we have found that Ly6CLo monocytes contribute to host defense against intracellular pathogens in a T-bet–dependent pathway. As previously mentioned, patrolling monocytes can be generated via 2 pathways: (i) through direct differentiation from a cMoP or (ii) further differentiation of Ly6C+ monocytes to Ly6CLo.132 cMoPs are a subset of the monocyte-DC precursor, which are capable of producing both patrolling and inflammatory monocytes but do not contribute to DC production.132 Regardless of origin, patrolling monocytes have been shown to be dependent on the transcription factor Nur77 for development yet play no role for the development or function of inflammatory monocytes.132 Therefore, to determine whether patrolling monocytes are critical for host defense against T. gondii, it will be imperative to test the acute toxoplasmosis mouse model employing Nur77 knockout (Nr4a1−/−) mice.46,49 Based on our previous findings, we predict that i.p.-infected Nr4a1−/− mice would have a significant increase in parasite burden, nearly a complete loss of TMCs, and succumb rapidly to infection, similar to Tbx21−/− mice, suggesting that TMCs are a subset of patrolling monocytes and have a significant role for host resistance against T. gondii. To further determine if TMCs are a subpopulation of patrolling monocytes, adoptive transfer studies would be performed in which patrolling monocytes from B6 or Tbx21−/− mice are transferred to T. gondii infected Nr4a1−/− mice and their pathogen burden and frequency of TMCs quantified on day 5 post-infection. As patrolling monocytes have been demonstrated to be strategically located throughout the host prior to infection, a confounding variable with the adoptive transfers would be the lack of their natural seeding throughout the host. While the transferred patrolling monocytes may still contribute to parasite clearance, their response might be less robust systemically, as they were not initially distributed according to their natural pattern. Further analysis could involve utilizing a BM transplant, with irradiated Nr4a1−/− mice that would receive BM transfers from either wild-type or Tbx21−/− donors. This approach to identify the lineage of TMCs could also be combined with the use of a Nur77-GFP reporter strain, which have the Nur77 promoter driving expression of a GFP indicating whether TMCs have expressed Nur77 at any point in their development; yet, although this would only provide a correlative observation between Nur77 expression and TMCs, it does provide further direction for classifying this cell type. Overall, these experiments would provide further direction for mechanistic studies of this population and give guidance for determining a similar population that may exist in humans.

Figure 3.

Frequency of T-bet expression within myeloid populations. C57BL/6J mice were i.p. infected with 20 cysts and peritoneal exudate cells were harvested on day 5 post-infection. CITE-seq was performed by using TotalSeq antibody cocktail (BioLegend) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Raw FASTQ files were mapped to the GRCm39 reference genome using 10x Genomics Cell Ranger 9.0.0134 to infer read counts of both gene expression (RNA) and antibody-derived tag per gene per cell. Quality control is performed using Seurat package v5.0135 by removing cells with fewer than 500 or more than 7,500 detected genes, and cells fewer than 1,000 or more than 50,000 unique molecular identifiers, and cells greater than 20% mitochondrial content. Following quality control, SCTransform136 was used for normalizing the RNA read counts. Principal component analysis (PCA) is performed for dimension reduction on the normalized RNA read counts for the purpose of cell clustering. Specifically, the top 30 principal components were used with a resolution of 0.5. (A) t-Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding for cluster visualization. Antibody-derived tag counts were normalized using the centered log ratio method. Clusters were further annotated based on known marker genes or antibody levels. (B) Particularly, Tbx21 expression levels were subsequently visualized across annotated clusters. Through unpublished CITE-seq results, our group has identified a strong expression of Tbx21 within a subset of Ly6CLo-neg monocytes and DCs. While limited expression exists within other cell types, a majority of T-bet in myeloid populations is found within a distribution that we believe contains TMCs. Further analysis is being conducted to determine the qualities of this population and isolate them for further experiments to determine their nature of functionality.

Conclusions and perspectives

Inspection of the commonalities that mediate immunity is critical for the development of a comprehensive model of a coordinated and protective immune response. One such commonality is the expression of T-bet within myeloid populations, which is highly conserved across species, including humans.133 Several studies have identified that T-bet can be expressed in DCs and monocytes, and plays a role in controlling inflammatory arthritis, priming of T cells, CpG DNA adjuvancy, IFN-γ and TNF production, colorectal cancer development, and host defense against T. gondii. Using CITE-seq, T-bet expression was identified in various myeloid populations during acute T. gondii infection including DCs and Ly6CLo-neg monocytes (Fig. 3). This observation generates novel questions in the field: (i) Does T-bet directly mediate cell-intrinsic antimicrobial defense for parasite clearance? (ii) Do T-bet–expressing myeloid cells augment the CD4+ T cell effector function during infection? and (iii) Do humans possess T-bet–expressing myeloid cells that can eliminate intracellular pathogens? Moreover, this new avenue of research has far-reaching translational implications for targeting T-bet–dependent myeloid cell immunity against T. gondii, as well as other highly virulent intracellular human pathogens, such as Leishmania, Mycobacteria, and Salmonella.

The recent identification of key effector mechanisms of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and DCs against acute T. gondii infection may inform other long-standing questions about the role of myeloid cell populations in host resistance to intracellular pathogens. Our recent study has revealed T-bet to be vital for CD11c+MHCII− myeloid cells in initiating and maintaining protective mechanisms against T. gondii. It is imperative to further define the importance of T-bet within the myeloid cell populations. Our study found TMCs do not only possess high levels of T-bet, but also the highest levels of parasite burden, suggesting that this population of cells is an unexplored and critical component of host defense against T. gondii. We continue to build on these observations by leveraging CITE-seq to further define the qualities of T-bet–expressing myeloid cells. Future studies will be aimed at delineating the overall contribution to host protection. While the human immune system lacks key components of the anti-T. gondii murine immune system, such as TLR11, they are still capable of mounting immune responses that clear and control intracellular parasites such as T. gondii. Thus, focused murine studies can be used to determine the full extent of TMCs’ effector function to extrapolate which processes are indispensable for defense against intracellular pathogens. Defining the mechanisms by which neutrophil, Ly6CHi monocyte, Ly6CLo monocyte, TRM, macrophage, and DC populations individually contribute to the innate immune response offers critical insight into developing novel parasitic prevention methods and therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Anthony Franchini for comments on this review.

Contributor Information

Madison L Schanz, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States.

Fengdi Zhao, Department of Biostatistics, University of Florida, Tallahassee, FL, United States.

Kamryn E Zadeii, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States.

Li Chen, Department of Biostatistics, University of Florida, Tallahassee, FL, United States.

Américo H López-Yglesias, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States.

Author contributions

M.L.S. (Conceptualization [Equal], Formal analysis [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Supervision [Equal], Visualization [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal]), F.Z. (Formal analysis [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Visualization [Equal], Writing—original draft [Supporting]), K.E.Z. (Visualization [Supporting], Writing—review & editing [Supporting]), L.C. (Formal analysis [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Visualization [Equal], Writing—original draft [Supporting]), and A.H.L.-Y. (Conceptualization [Lead], Formal analysis [Lead], Funding acquisition [Lead], Investigation [Lead], Project administration [Lead], Resources [Lead], Supervision [Lead], Visualization [Lead], Writing—original draft [Lead], Writing—review & editing [Lead])

Funding

This work was supported by the American Heart Association Career Development Award 858028 (A.H.L.-Y), the Indiana University School of Medicine Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Research Enhancement Grant (A.H.L.-Y), the Indiana University School of Medicine Program to Launch those Underrepresented in Medicine toward Success (A.H.L.-Y), and National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI168056 (A.H.L.-Y), and R35GM142701 (L.C.).

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The data underlying this article is included in this article.

References

- 1. Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Speer CA. Structures of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites and biology and development of tissue cysts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:267–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harms Pritchard G et al. Diverse roles for T-bet in the effector responses required for resistance to infection. J Immunol. 2015;194:1131–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. López-Yglesias AH, Burger E, Araujo A, Martin AT, Yarovinsky F. T-bet-independent Th1 response induces intestinal immunopathology during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:921–931., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schanz ML et al. IL-12 mediates T-bet-expressing myeloid cell-dependent host resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Immunohorizons. 2024;8:355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harms Pritchard G, Kedl RM, Hunter CA. The evolving role of T-bet in resistance to infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:398–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martin AT et al. Parasite-induced IFN-gamma regulates host defense via CD115 and mTOR-dependent mechanism of tissue-resident macrophage death. PLoS Pathog. 2024;20:e1011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abi Abdallah DS et al. Toxoplasma gondii triggers release of human and mouse neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect Immun. 2012;80:768–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Denkers EY, Butcher BA, Del Rio L, Bennouna S. Neutrophils, dendritic cells and Toxoplasma. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Denkers EY. Toll-like receptor initiated host defense against Toxoplasma gondii. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:737125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scanga CA et al. Cutting edge: MyD88 is required for resistance to Toxoplasma gondii infection and regulates parasite-induced IL-12 production by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:5997–6001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Del Rio L, Bennouna S, Salinas J, Denkers EY. CXCR2 deficiency confers impaired neutrophil recruitment and increased susceptibility during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:6503–6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sayles PC, Johnson LL. Exacerbation of toxoplasmosis in neutrophil-depleted mice. Nat Immun. 1996;15:249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bliss SK, Gavrilescu LC, Alcaraz A, Denkers EY. Neutrophil depletion during Toxoplasma gondii infection leads to impaired immunity and lethal systemic pathology. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4898–4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fleming TJ, Fleming ML, Malek TR. Selective expression of Ly-6G on myeloid lineage cells in mouse bone marrow. RB6-8C5 mAb to granulocyte-differentiation antigen (Gr-1) detects members of the Ly-6 family. J Immunol. 1993;151:2399–2408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dunay IR, Fuchs A, Sibley LD. Inflammatory monocytes but not neutrophils are necessary to control infection with Toxoplasma gondii in mice. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1564–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sturge CR, Burger E, Raetz M, Hooper LV, Yarovinsky F. Cutting edge: developmental regulation of IFN-gamma production by mouse neutrophil precursor cells. J Immunol. 2015;195:36–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hou B, Benson A, Kuzmich L, DeFranco AL, Yarovinsky F. Critical coordination of innate immune defense against Toxoplasma gondii by dendritic cells responding via their Toll-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:278–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim L et al. Toxoplasma gondii genotype determines MyD88-dependent signaling in infected macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;177:2584–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yarovinsky F et al. TLR11 activation of dendritic cells by a protozoan profilin-like protein. Science. 2005;308:1626–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lopez-Yglesias AH, Camanzo E, Martin AT, Araujo AM, Yarovinsky F. TLR11-independent inflammasome activation is critical for CD4+ T cell-derived IFN-gamma production and host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roach JC et al. The evolution of vertebrate Toll-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9577–9582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sturge CR et al. TLR-independent neutrophil-derived IFN-gamma is important for host resistance to intracellular pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10711–10716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miranda FJB et al. Toxoplasma gondii-induced neutrophil extracellular traps amplify the innate and adaptive response. mBio. 2021;12:e0130721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ethuin F et al. Human neutrophils produce interferon gamma upon stimulation by interleukin-12. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1363–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ellis TN, Beaman BL. Murine polymorphonuclear neutrophils produce interferon-gamma in response to pulmonary infection with Nocardia asteroides. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kirby AC, Yrlid U, Wick MJ. The innate immune response differs in primary and secondary Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:4450–4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chou DB et al. Stromal-derived IL-6 alters the balance of myeloerythroid progenitors during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Askenase MH et al. Bone-marrow-resident NK cells prime monocytes for regulatory function during infection. Immunity. 2015;42:1130–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Orchanian SB, Lodoen MB. Monocytes as primary defenders against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Trends Parasitol. 2023;39:837–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yanez A et al. Granulocyte-monocyte progenitors and monocyte-dendritic cell progenitors independently produce functionally distinct monocytes. Immunity. 2017;47:890–902.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hashimoto D et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Varol C et al. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31:502–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raetz M et al. Parasite-induced TH1 cells and intestinal dysbiosis cooperate in IFN-gamma-dependent elimination of Paneth cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lopez-Yglesias AH, Burger E, Araujo A, Martin AT, Yarovinsky F. T-bet-independent Th1 response induces intestinal immunopathology during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:921–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Molloy MJ et al. Intraluminal containment of commensal outgrowth in the gut during infection-induced dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:318–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heimesaat MM et al. Gram-negative bacteria aggravate murine small intestinal Th1-type immunopathology following oral infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 2006;177:8785–8795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grainger JR et al. Inflammatory monocytes regulate pathologic responses to commensals during acute gastrointestinal infection. Nat Med. 2013;19:713–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Han SJ et al. Internalization and TLR-dependent type I interferon production by monocytes in response to Toxoplasma gondii. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:872–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fox BA, Gigley JP, Bzik DJ. Toxoplasma gondii lacks the enzymes required for de novo arginine biosynthesis and arginine starvation triggers cyst formation. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Butcher BA et al. Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry kinase ROP16 activates STAT3 and STAT6 resulting in cytokine inhibition and arginase-1-dependent growth control. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. El Kasmi KC et al. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1399–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scharton-Kersten TM, Yap G, Magram J, Sher A. Inducible nitric oxide is essential for host control of persistent but not acute infection with the intracellular pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1261–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chao CC et al. Activated microglia inhibit multiplication of Toxoplasma gondii via a nitric oxide mechanism. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;67:178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:392–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li YH et al. Occurrences and Functions of Ly6C(hi) and Ly6C(lo) Macrophages in Health and Disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:901672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Narasimhan PB et al. Patrolling monocytes control NK cell expression of activating and stimulatory receptors to curtail lung metastases. J Immunol. 2020;204:192–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schneider CA et al. Imaging the dynamic recruitment of monocytes to the blood-brain barrier and specific brain regions during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:24796–24807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Drewry LL et al. The secreted kinase ROP17 promotes Toxoplasma gondii dissemination by hijacking monocyte tissue migration. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1951–1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thomas GD et al. Deleting an Nr4a1 super-enhancer subdomain ablates Ly6C(low) monocytes while preserving macrophage gene function. Immunity. 2016;45:975–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Netea MG, Quintin J, van der Meer JW. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Foster SL, Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature. 2007;447:972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krahenbuhl JL, Sharma SD, Ferraresi RW, Remington JS. Effects of muramyl dipeptide treatment on resistance to infection with Toxoplasma gondii in mice. Infect Immun. 1981;31:716–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mulder WJM, Ochando J, Joosten LAB, Fayad ZA, Netea MG. Therapeutic targeting of trained immunity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:553–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kleinnijenhuis J et al. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17537–17542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lopez-Yglesias AH et al. FlgM is required to evade NLRC4-mediated host protection against flagellated Salmonella. Infect Immun. 2023;91:e0025523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Matsuno SY, Pandori WJ, Lodoen MB. Capers with caspases: Toxoplasma gondii tales of inflammation and survival. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2023;72:102264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Munoz-Planillo R, Nunez G. The inflammasome: a caspase-1-activation platform that regulates immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hitziger N, Dellacasa I, Albiger B, Barragan A. Dissemination of Toxoplasma gondii to immunoprivileged organs and role of Toll/interleukin-1 receptor signalling for host resistance assessed by in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:837–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Babcock IW et al. Caspase-1 in Cx3cr1-expressing cells drives an IL-18-dependent T cell response that promotes parasite control during acute Toxoplasma gondii infection. PLoS Pathog. 2024;20:e1012006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gov L, Karimzadeh A, Ueno N, Lodoen MB. Human innate immunity to Toxoplasma gondii is mediated by host caspase-1 and ASC and parasite GRA15. mBio. 2013;4:e00255–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gaidt MM et al. Human monocytes engage an alternative inflammasome pathway. Immunity. 2016;44:833–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Safronova A et al. Alarmin S100A11 initiates a chemokine response to the human pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang Y et al. Three Toxoplasma gondii dense granule proteins are required for induction of lewis rat macrophage pyroptosis. mBio. 2019;10:e02388–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fisch D et al. Human GBP1 is a microbe-specific gatekeeper of macrophage apoptosis and pyroptosis. EMBO J. 2019;38:e100926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fisch D et al. Human GBP1 differentially targets salmonella and toxoplasma to license recognition of microbial ligands and caspase-mediated death. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Moreira-Souza ACA et al. The P2X7 receptor mediates Toxoplasma gondii control in macrophages through canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation and reactive oxygen species production. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gorfu G et al. Dual role for inflammasome sensors NLRP1 and NLRP3 in murine resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. mBio. 2014;5:e0117–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gazzinelli RT et al. Parasite-induced IL-12 stimulates early IFN-gamma synthesis and resistance during acute infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1994;153:2533–2543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mashayekhi M et al. CD8alpha(+) dendritic cells are the critical source of interleukin-12 that controls acute infection by Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Immunity. 2011;35:249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mun HS et al. TLR2 as an essential molecule for protective immunity against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1081–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Debierre-Grockiego F et al. Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by glycosylphosphatidylinositols derived from Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 2007;179:1129–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ahmed AK et al. Roles of Toxoplasma gondii-derived heat shock protein 70 in host defense against T. gondii infection. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48:911–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Andrade WA et al. Combined action of nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors and TLR11/TLR12 heterodimers imparts resistance to Toxoplasma gondii in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ewald SE, Chavarria-Smith J, Boothroyd JC. NLRP1 is an inflammasome sensor for Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun. 2014;82:460–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. DeLaney AA et al. Caspase-8 promotes c-Rel-dependent inflammatory cytokine expression and resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:11926–11935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Quan JH et al. P2X7 receptor mediates NLRP3-dependent IL-1beta secretion and parasite proliferation in Toxoplasma gondii-infected human small intestinal epithelial cells. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lees MP et al. P2X7 receptor-mediated killing of an intracellular parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, by human and murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;184:7040–7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nathan CF, Murray HW, Wiebe ME, Rubin BY. Identification of interferon-gamma as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and antimicrobial activity. J Exp Med. 1983;158:670–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sibley LD, Weidner E, Krahenbuhl JL. Phagosome acidification blocked by intracellular Toxoplasma gondii. Nature. 1985;315:416–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Murray HW, Gellene RA, Libby DM, Rothermel CD, Rubin BY. Activation of tissue macrophages from AIDS patients: in vitro response of AIDS alveolar macrophages to lymphokines and interferon-gamma. J Immunol. 1985;135:2374–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Adams LB, Hibbs JB Jr, Taintor RR, Krahenbuhl JL. Microbiostatic effect of murine-activated macrophages for Toxoplasma gondii. Role for synthesis of inorganic nitrogen oxides from L-arginine. J Immunol. 1990;144:2725–2729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Matta SK et al. NADPH oxidase and guanylate binding protein 5 restrict survival of avirulent type III strains of Toxoplasma gondii in naive macrophages. mBio. 2018;9:e01393–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kim JH et al. NADPH oxidase 4 is required for the generation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor and host defense against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Murray HW, Juangbhanich CW, Nathan CF, Cohn ZA. Macrophage oxygen-dependent antimicrobial activity. II. The role of oxygen intermediates. J Exp Med. 1979;150:950–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Collazo CM et al. Inactivation of LRG-47 and IRG-47 reveals a family of interferon gamma-inducible genes with essential, pathogen-specific roles in resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 2001;194:181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Taylor GA et al. Pathogen-specific loss of host resistance in mice lacking the IFN-gamma-inducible gene IGTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:751–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zhao Y et al. Virulent Toxoplasma gondii evade immunity-related GTPase-mediated parasite vacuole disruption within primed macrophages. J Immunol. 2009;182:3775–3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Liesenfeld O et al. The IFN-gamma-inducible GTPase, Irga6, protects mice against Toxoplasma gondii but not against Plasmodium berghei and some other intracellular pathogens. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fentress SJ et al. Phosphorylation of immunity-related GTPases by a Toxoplasma gondii-secreted kinase promotes macrophage survival and virulence. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:484–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zhao YO, Khaminets A, Hunn JP, Howard JC. Disruption of the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole by IFNgamma-inducible immunity-related GTPases (IRG proteins) triggers necrotic cell death. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yamamoto M et al. A cluster of interferon-gamma-inducible p65 GTPases plays a critical role in host defense against Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity. 2012;37:302–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Degrandi D et al. Extensive characterization of IFN-induced GTPases mGBP1 to mGBP10 involved in host defense. J Immunol. 2007;179:7729–7740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zhao Z et al. Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:458–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Burger E et al. Loss of Paneth cell autophagy causes acute susceptibility to toxoplasma gondii-mediated inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:177–190.e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bekpen C et al. The interferon-inducible p47 (IRG) GTPases in vertebrates: loss of the cell autonomous resistance mechanism in the human lineage. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Olszewski MA, Gray J, Vestal DJ. In silico genomic analysis of the human and murine guanylate-binding protein (GBP) gene clusters. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:328–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kresse A et al. Analyses of murine GBP homology clusters based on in silico, in vitro and in vivo studies. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Steffens N et al. Essential role of mGBP7 for survival of Toxoplasma gondii infection. mBio. 2020;11:e02993–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Piro AS et al. Detection of cytosolic shigella flexneri via a C-terminal triple-arginine motif of GBP1 inhibits actin-based motility. mBio. 2017;8:e01979–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wandel MP et al. GBPs inhibit motility of shigella flexneri but are targeted for degradation by the bacterial ubiquitin ligase IpaH9.8. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:507–518 e505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Araujo A et al. IFN-gamma mediates Paneth cell death via suppression of mTOR. Elife. 2021;10:e60478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yarovinsky F, Kanzler H, Hieny S, Coffman RL, Sher A. Toll-like receptor recognition regulates immunodominance in an antimicrobial CD4+ T cell response. Immunity. 2006;25:655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Raetz M et al. Cooperation of TLR12 and TLR11 in the IRF8-dependent IL-12 response to Toxoplasma gondii profilin. J Immunol. 2013;191:4818–4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Pereira M et al. The IRAK1/IRF5 axis initiates IL-12 response by dendritic cells and control of Toxoplasma gondii infection. Cell Rep. 2024;43:113795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Negishi H et al. Negative regulation of Toll-like-receptor signaling by IRF-4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15989–15994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Reis e Sousa C et al. In vivo microbial stimulation induces rapid CD40 ligand-independent production of interleukin 12 by dendritic cells and their redistribution to T cell areas. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1819–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Hildner K et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. López-Yglesias AH et al. T-bet-dependent ILC1- and NK cell-derived IFN-γ mediates cDC1-dependent host resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1008299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Tussiwand R et al. Klf4 expression in conventional dendritic cells is required for T helper 2 cell responses. Immunity. 2015;42:916–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]