ABSTRACT

Aim

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) are increasingly utilising kidney health care services. However, there is no data on the impact of kidney transition clinics, as well as the AYA spectrum of kidney diseases, in South Africa (SA). This study evaluates kidney outcomes and patient survival amongst AYA patients attending a dedicated kidney AYA clinic (KAYAC).

Methods

This 5‐year retrospective study included AYA (aged 13–25) with kidney disease, attending a tertiary nephrology service. A comparative analysis of outcomes between patients who attended the KAYAC and those attending the standard‐of‐care adult kidney clinics was performed. The primary composite outcome assessed included doubling of creatinine, reduction in eGFR > 40%, kidney failure, requirement for kidney replacement therapy, or death. Logistic regression evaluated the associations between relevant variables, death, and loss to follow‐up (LTFU).

Results

The AYA cohort consisted of 292 patients: 111 (38.0%) attended KAYAC and 181 (62.0%) attended adult clinics. Glomerular diseases (72.6%), congenital urinary tract anomalies (10.6%) and hereditary conditions (8.2%) were the most common causes of kidney disease. The KAYAC group had delayed progression to kidney failure with an improved composite outcome (p = 0.018), lower mortality (p = 0.046) and less LTFU (p = 0.001). Both groups demonstrated high rates of non‐adherence, with a prevalence of 33.9% in the total cohort.

Conclusion

AYA are a unique population who could benefit from KAYAC transition clinics. A dedicated KAYAC has been found to be associated with better kidney outcomes, lower mortality and less LTFU, underscoring its critical role in resource‐limited settings.

Keywords: Adolescent and young adult, chronic kidney disease, kidney outcomes, transition clinic

This retrospective study assessed the kidney outcomes and survival of adolescents and young adults (AYA) in those who attended the kidney adolescent and young adult clinic (KAYAC) compared to those who attended the standard‐of‐care adult kidney clinics.

1. Introduction

Adolescents constitute nearly a quarter of the world's population and represent an increasing proportion of those receiving kidney health care globally [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescence as a phase of life between 10 and 19 years of age and young adults as individuals aged between 15 and 24 year [2]. With advances in medical care, a greater number of adolescent and young adults (AYAs) with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are reaching adulthood [3]. It is estimated that approximately 70% of children with CKD will progress to kidney failure by the age of 20 years [4]. Importantly, 95% of AYAs with kidney failure in sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA) do not have access to kidney replacement therapy (KRT) [5]. A dedicated kidney AYA clinic (KAYAC) is a cost‐effective intervention which has the potential to improve kidney outcomes, enhance advocacy and enable young individuals to lead productive lives.

Adolescence is characterised by a period of rapid physical, cognitive and psychosocial development, with the completion of brain development occurring only by the age of 25 years [6]. This developmental phase influences the individual's engagement with management of CKD, impacting executive planning, risk assessment and behavioural regulation [7, 8]. Adolescent decision‐making often favours short‐term reward‐seeking behaviour and risk‐taking tendencies over long‐term gains. This makes the management of chronic illnesses particularly challenging [9]. In addition, studies report that children with CKD have an increased risk of cognitive impairment, with lower‐than‐average cognition, compared to age‐matched controls [10, 11]. The reported deficits include academic skills, executive function, visual and verbal memory [12]. All of these factors contribute towards increased rates of high‐risk behaviour, reduced adherence and poor health‐seeking tendencies, which may negatively impact the management of CKD.

In South Africa (SA), the health care system is two‐tiered and economically disparate. The private sector services 16% of the population who have private health insurance and offers full access to KRT [13]. In contrast, the state sector services 84% of the population, subsidised by the government and has limited access to chronic KRT [13]. The chronic KRT programme prioritises patients who are eligible for future kidney transplantation [13, 14]. Kidney transplantability is the overarching principle for acceptance to most state sector KRT programmes. Thus, good adherence to medical treatment and clinic visits is essential to prevent progression to end‐stage kidney failure and suitability for future KRT [15].

In 2002, in light of the complexities of managing AYAs, a dedicated transition clinic was established for kidney transplant patients in Cape Town. In 2015, this clinic was re‐designed and expanded to include patients aged 13–25 years, irrespective of the aetiology or stage of CKD. The KAYAC service is unique in that it provides an ‘adolescent friendly’ service compared to the standard of care adult kidney clinics. KAYAC is characterised by smaller clinic sizes, longer clinic consultations, pre‐ordered medication and more frequent follow‐up visits (every 1–3 months, depending on aetiology and requirement). In addition, a dedicated multi‐disciplinary team including an adult and paediatric nephrologist, nephrology resident, professional nurse, dedicated social worker and clinical psychologist are present at the clinic, enhancing psychological and social support. The approach to non‐attendance to clinic visits involves contacting the patient, with subsequent adolescent social worker review. In comparison, the adult clinic environment is busier, with larger clinic sizes, less time for consultations, and less frequent follow‐up visits (3–6 monthly) due to the clinical burden with increased patient numbers. Medication is required to be collected from a busy outpatient pharmacy, and access to multi‐disciplinary care is curtailed by the availability of the independent services. If appointments are missed, the expectation is for the patient to inform the clinic and re‐schedule the visit with the administrative staff.

Patients are referred to KAYAC from distinct two sources: paediatric nephrology or adult nephrology services. When patients are referred from the paediatric centre, the transition pathway includes an initial combined clinic visit with input from both paediatric and adult nephrologists at the paediatric hospital. The focus is predominantly on the integration of care, while assessing transition readiness. Thereafter, patients are transferred over to KAYAC, which is located in the adult hospital. When patients are referred to KAYAC from the adult health care services, the referrals mainly consist of new nephrology referrals. In addition, the existing patients (aged 13–25 years), who were present in the adult kidney clinics prior to the establishment of the re‐designed KAYAC, were gradually transferred over to KAYAC, with the rate of transfer being staff resources.

KAYAC clinic visits are structured into two components. The first component consists of the Better Together programme peer‐led support group which provides patients with a sense of belonging and unity. A study from our centre demonstrated that AYAs who attend the support group have significantly lower anxiety (p = 0.001) and depression (p = 0.039), compared to those not attending the group [16]. These sessions are facilitated by trained peer mentors and supported by a dedicated adolescent social worker. The second component consists of the clinical assessment of the patient by the multidisciplinary team. The aim of this clinic is to provide an adolescent‐friendly environment, which focuses on best clinical practice medicine and patient education.

The primary objective of this study is to compare the proportion of patients reaching the composite outcome (doubling of serum creatinine, having a reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] greater than 40%, kidney failure, requirement of KRT or death); in those attending KAYAC compared to those attending the mainstream adult kidney clinics within the hospital.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This retrospective study assessed nephrology patients aged between 13 and 25 years between 1 June 2015 and 31 May 2020, with CKD (Stages 1–5, including those on KRT), irrespective of the aetiology, attending the kidney service in Cape Town, SA. Figure S1 illustrates the study participant process. The KAYAC cohort consisted of, (1) new referrals from paediatric nephrology services, (2) new referrals from adult nephrology services and (3) the transfer of pre‐existing AYA in the existing adult kidney services. As KAYAC was a new clinic service, the pre‐existing AYA who were attending the ‘standard of care’ adult kidney clinics, were gradually transferred over from the adult kidney clinics to KAYAC. During this study period there, AYA attending the adult kidney clinics (awaiting transfer into KAYAC) inadvertently created a control group to assess the impact of the new clinic intervention, constituting a comparator arm. AYA patients eligible for the study were therefore stratified into two groups, those attending KAYAC and those remaining in the ‘standard of care’ adult clinics. Patients who had acute kidney injury, followed up at different hospitals or those who had insufficient medical records were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Cape Town (HREC REF 646/2020).

2.2. Data Collection and Definitions

Relevant data collected included the primary aetiology of kidney disease, CKD stage and KRT status; as well as various clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters. Demographic and clinical data included: age, sex, blood pressure (mmHg), body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and comorbidities, including diabetes and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Biochemical data recorded included serum creatinine (μmol/L), eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) using the Swartz formula for patients younger than 18 years, and CKD‐EPI 2021 for patients older than 18 years [17, 18]. Additional variables collected were haemoglobin (g/dL) and urine protein‐to‐creatinine ratio (UPCR; g/mmol creatinine). Data was recorded at baseline, annually and at last clinic visit.

Non‐adherence was defined as having missed clinic visits or having sub‐therapeutic drug levels on two or more occasions per year, or self‐reported medication omission on two or more occasions per month, without a clear reason. In this study, lost to follow‐up (LTFU) was defined as non‐attendance to the clinic for more than 1 year.

2.3. Primary and Secondary End Points

The primary outcome assessed the proportion of patients reaching a pre‐specified composite outcome that included doubling of serum creatinine, reduction in eGFR greater than 40%, kidney failure, need for KRT (including chronic dialysis or kidney transplantation) or death. The eGFR reduction of greater than 40% was selected as an outcome marker, as studies have shown this value to have a strong association with the increased future risk of kidney failure [19, 20]. In this study, kidney survival referred to the event‐free period to kidney failure or need for KRT. In addition, allograft failure referred to kidney allograft function with persistent eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or necessity for KRT initiation in a kidney transplant recipient. Existing KRT patients on chronic dialysis were censored in the composite outcome analysis, but included in the independent death and LTFU analysis. The composite outcome was assessed at 5 years. Secondary outcomes were death, LTFU and non‐adherence. Outcomes of AYA patients who were transplanted were reviewed separately for rates of kidney allograft rejection, allograft failure, adherence and LTFU.

The patient characteristics, primary aetiology of CKD and outcomes were summarised by median and IQR for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. A bivariate analysis was performed between patients attending KAYAC and those who attended the adult kidney clinics using Wilcoxon rank–sum (continuous variables) and chi‐squared or Fisher's exact test (categorical variables) between clinic groups and outcomes. Univariable logistic regression was used to evaluate the strength of associations between clinical and biochemical relevant variables with death and LTFU. The low number of deaths (n = 26) particularly in the KAYAC group, precluded a multivariable analysis. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to estimate differences in composite outcome probability and patient survival between KAYAC and adult kidney clinic patients and with varying aetiology. The log–rank test and patient survival curves were used to illustrate differences between the groups. Data was censored for LTFU and for study completion. A p value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analysis was performed in Stata, /BE version 17.0 (Statacorp LP, College Station, United States of America [USA]).

3. Results

Over the 5‐year period, 351 AYA patients attended the nephrology service. There were 292 eligible for the study, with 111 (38.0%) attending the KAYAC and 181 (61.9%) remaining in the adult clinics (Figure S1).

The baseline characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. There was a predominance of females (55.1%), a high prevalence of hypertension (65.8%) and the majority had CKD Stage 1 (45.9%). Those attending KAYAC were younger (19 vs. 21 years; p = 0.013), had a lower UPCR (0.04 vs. 0.013; p = 0.035), had a longer duration of follow‐up (37 vs. 18 months; p < 0.001), a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (7% vs. 1%; p = 0.001) and a higher proportion were on KRT (23% vs. 12%; p = 0.007). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of hypertension, creatinine, or eGFR. The most common aetiologies detected were glomerular disease (72.6%), followed by CAKUT (10.6%) and hereditary conditions (8.2%) (Table S1). A similar pattern of disease was seen across both patient clinic cohorts, except for hereditary conditions which predominantly attended the KAYAC.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics—clinical and biochemical features of kidney patients attending the kidney AYA clinic and the adult kidney clinics.

| Parameters | All (n = 292) | Kidney AYA clinic (n = 111) | Kidney adult clinics (n = 181) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first visit, years (median, IQR) | 20 (18–23) | 19 (17–21) | 21 (18–23) | 0.003 |

| Age < 18 years (n, %) | 81 (28) | 40 (36) | 41 (23) | — |

| Age > 18 years (n, %) | 211 (72) | 71 (64) | 140 (77) | 0.013 |

| Sex: male (n, %) | 131 (45) | 47 (42) | 84 (46) | 0.500 |

| Duration of follow‐up, months (median, IQR) | 24 (8–54) | 37 (19–60) | 18 (3–45) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (median, IQR) | 22 (20–26) | 22 (20–27) | 22 (20–24) | 0.280 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension (n, %) | 192 (66) | 71 (64) | 121 (67) | 0.610 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg (median, IQR) | 130 (120–144) | 128 (119–139) | 133 (120–146) | 0.085 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg (median, IQR) | 80 (70–88) | 78 (68–86) | 80 (70–90) | 0.200 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 9 (3) | 8 (7) | 1 (1) | 0.001 |

| HIV infection (n, %) | 12 (4) | 2 (2) | 10 (6) | 0.120 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Serum creatinine, μmol/L (median, IQR) | 91 (60–254) | 76 (56–284) | 96 (61–250) | 0.200 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 (median, IQR) | 84 (26–126) | 94 (25–129) | 79 (27–120) | 0.280 |

| Serum albumin, g/L (median, IQR) | 39 (30–43) | 40 (34–44) | 38 (28–42) | 0.009 |

| Serum total cholesterol, mmol/L (median, IQR) | 4 (4–6) | 4 (4–5) | 4 (4–6) | 0.410 |

| Serum haemoglobin, g/dL (median, IQR) | 11.5 (9–13) | 12.1 (10–13) | 11.1 (9–13) | 0.310 |

| UPCR, g/mmol creatinine (median, IQR) | 0.07 (0.02–0.31) | 0.04 (0.02–0.21) | 0.13 (0.02–0.34) | 0.035 |

| Stage of CKD | ||||

| Stage 1 (n, %) | 134 (46) | 55 (49) | 79 (44) | 0.042 |

| Stage 2 (n, %) | 54 (22) | 16 (18) | 38 (24) | 0.320 |

| Stage 3 (n, %) | 9 (4) | 1 (1) | 8 (5) | 0.170 |

| Stage 4 (n, %) | 19 (8) | 7 (8) | 12 (8) | 0.890 |

| Stage 5, not on KRT (n, %) | 28 (10) | 6 (5) | 22 (12) | 0.700 |

| Kidney replacement therapy (n, %) | 48 (16) | 26 (23) | 22 (12) | 0.007 |

| Haemodialysis (n, %) | 17/48 (35) | 6/26 (23) | 11/22 (50) | — |

| Peritoneal dialysis (n, %) | 19/48 (40) | 14/26 (53) | 5/22 (23) | — |

| Kidney Transplant (n, %) | 12/48 (25) | 6/26 (23) | 6/22 (27) | — |

Abbreviations: AYA, adolescent and young adults; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimate glomerular filtration rate; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; n, number; UPCR, urine protein:creatinine ratio.

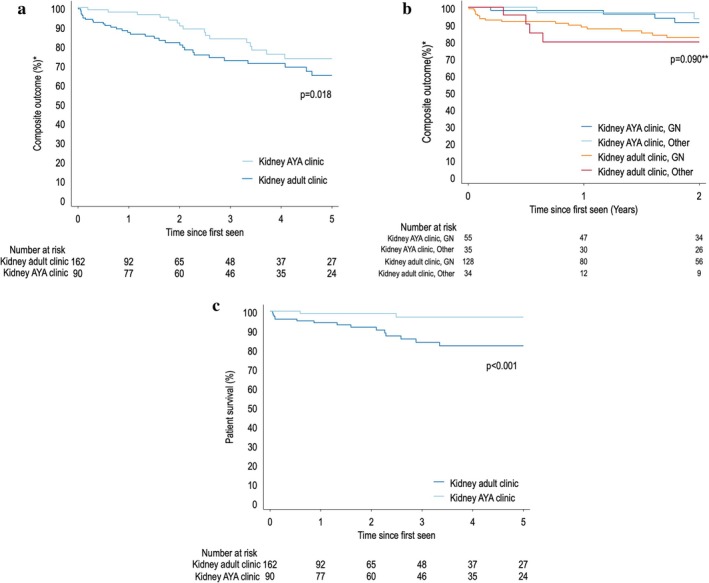

Kidney outcomes between the two groups can be viewed in Table 2. The composite outcome analysis censored patients on chronic dialysis at baseline, with a total of 256 being included for analysis. Improved kidney preservation in the composite outcome, as well as patient survival, in the Kaplan‐Meier curve was observed in patients attending the KAYAC, compared to those attending the adult clinic (p = 0.018) (Figure 1a). The median time to the composite outcome in AYA was longer in the KAYAC cohort compared to the adult kidney clinic cohort (P50 median [IQR P25‐P75] 3.14 vs. 1.45 years). The Kaplan–Meier curve showed an improved composite outcome survival in those attending KAYAC to be 97% (95% confidence interval [CI] 90.96–99.41), 91% (95% CI 82.90–96.33) and 73% (95% CI 59.83–83.08) at 1, 2 and 5 years, respectively. In comparison, the kidney adult clinics reflected a composite outcome survival of 87% (95% CI 79.99–91.83), 81% (95% CI 73.40–87.74) and 64% (95% CI 52.67–74.36) in the corresponding years (Figure 1a). Figure 1b stratifies event‐free survival according to the underlying aetiology (GN vs. non‐GN) in the two cohorts. It demonstrates a trend towards improved composite outcome survival in those attending KAYAC, compared to those attending adult clinic services (0 = 0.090), independent of the presence of a GN aetiology. Although the relative proportion comparison of the composite outcome at 5 years was not significant (p = 0.470), the Kaplan–Meier curves (time to the composite outcomes at 5 years) were statistically different (p = 0.018). The hazard of the composite outcome is reduced by 33% in AYA clinic after adjustment for baseline age, hypertension, HIV, eGFR and UPCR (p = 0.166). Increased age and reduced eGFR at baseline were strong, independent risk factors for increased risk of composite outcome. There was lower mortality (4% vs. 12%; p = 0.046) and less LTFU (18% vs. 34%; p = 0.0021) in the total cohort of patients attending KAYAC. The Kaplan–Meier (Figure 1c) demonstrates greater patient survival in those attending the KAYAC (p < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Outcomes of kidney patients attending the kidney AYA clinic and the kidney adult clinic.

| Parameters | All | Kidney AYA clinic | Kidney adult clinic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney outcomes (n = 256) | ||||

| Doubling of creatinine (n, %) | 35/256 (14) | 13/91 (14) | 22/165 (13) | 0.830 |

| Reduction in eGFR > 40% (n, %) | 44/256 (17) | 14/91 (15) | 30/165 (18) | 0.570 |

| Kidney failure at last visit (n, %) | 43/256 (17) | 10/91 (11) | 33/165 (20) | 0.065 |

| KRT at last visit (n = 34; n, %) | 34/256 (13) | 16/91 (18) | 18/165 (11) | 0.150 |

| Peritoneal dialysis (n, %) | 10/34 (29) | 3/16 (19) | 7/18 (39) | |

| Haemodialysis (n, %) | 4//34 (12) | 1/16 (6) | 3/18 (17) | |

| Kidney transplant (n = 20; n, %) | 20/34 (59) | 12/16 (75) | 8/18 (44) | |

| Graft failure (n, %) | 4/20 (20) | 1/12 (8) | 3/8 (4) | 0.730 |

| Death in composite outcome cohort (n, %) | 22/256 (9) | 2/91 (2) | 20/165 (12) | 0.007 |

| Composite outcome a | 63/256 (25) | 20/91 (22) | 43/165 (26) | 0.470 |

| Death in total cohort (n = 292; n, %) | 26/292 (9) | 5/118 (4) | 21/181 (12) | 0.046 |

| Lost to follow‐up in total cohort (n = 292; n, %) | 79/292 (27) | 18/118 (15) | 61/181 (34) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimate glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end‐stage kidney disease; kidney AYA clinic, kidney adolescent and young adult clinic; KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

Composite end point, doubling of creatinine + reduction in eGFR > 40% + kidney failure + need for KRT + death.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier Curve composite outcome* of patients attending the KAYAC and the kidney adult clinic (a), stratified by attendance and underlying aetiology (b). Kaplan–Meier Curve of patient survival in patients attending the kidney AYA clinic and the kidney adult clinics (c). AYA, adolescent and young adults; GN, glomerulonephritis. *Composite outcome: doubling of creatinine, reduction in eGFR > 40%, kidney failure, requirement of kidney replacement therapy or death. **p values reflect the comparison the two clinic attendance groups.

Death was associated with hypertension (odds ratio [OR] 4.5; 95% CI 1.33–15.50; p = 0.016), nephrotic range proteinuria (OR 3.56; 95% CI 1.78–7.12; p < 0.0001) and severe kidney dysfunction at baseline assessment (p < 0.001). The leading causes of death in AYA with kidney disease were infection (42.3%), progression to kidney failure without access to KRT (30.8%), cardiovascular events (15.4%) and malignancy (7.7%). The most common causes of infection‐related deaths were pneumonia, intra‐abdominal sepsis, urinary tract infections and vascular access‐related bacterial infections.

Approximately one third of the cohort was LTFU (30.8%). However, fewer patients attending the KAYAC were LTFU [21% vs. 37%; p = 0.012] (Table 2). Patients who were LTFU had less severe disease. An eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (OR 2.28; 95% CI 1.282–4.055; p = 0.005) at baseline was strongly associated with being LTFU, whereas attendance at the KAYAC was associated with a lower risk of death (OR 0.38; 95% CI 0.211–0.689; p = 0.001). Non‐adherence was noted in 33.9% of the total cohort, with better attendance and fewer missed appointments or dialysis sessions (10% vs. 18%; p = 0.054) in those attending the KAYAC.

There were 32 kidney transplant patients out of the total cohort (32/292; 11%). Fifty‐six percent attended the KAYAC and 43.7% attended the adult transplant clinic. In the total kidney transplant cohort, over the 5‐year period, 28.1% had allograft rejection and 18.7% had allograft failure, with no significant difference between the two groups. Death occurred in 9.3% of the kidney transplant recipients and the aetiology was predominantly attributed to bacterial infection or the progression of kidney allograft failure without access to KRT. LTFU was identified in 12.5% and occurred predominantly in those attending the adult kidney clinic.

4. Discussion

Globally, there is a paucity of data on adolescent kidney disease outcomes and the impact of transition clinics, particularly in resource‐restricted regions, such as SSA. This study is important as it demonstrated an improvement in the kidney composite outcome, lower mortality rates and less LTFU in those attending a dedicated KAYAC clinic. This is an important intervention in the context where access to dialysis and transplantation is restricted due to limited resources. In addition, this study describes the spectrum of kidney disease of AYA in a South African population.

4.1. Spectrum of Kidney Disease

The spectrum of kidney disease in AYA is heterogeneous and encompasses a wide variety of aetiologies in SA. It differs distinctly from those found in paediatric and adult populations, as illustrated in Table 3 [21, 23, 24, 25, 28, 30, 32, 33, 34]. In this study, the top three aetiologies were glomerular disease, CAKUT and hereditary conditions. The pattern of disease is similar to that found in published paediatric data from low‐resourced countries where glomerular diseases predominate [24, 29]. It does, however, contrast with paediatric data from high‐resourced countries, where CAKUT is more commonly reported [21, 23]. The lower proportion of CAKUT in our setting may be influenced by two factors: First, the current referral pathway for CAKUT with early stages of CKD, predominantly managed by the adult urology service; second, patients with severe CAKUT with unsuitable bladders for transplantation are not offered chronic dialysis in the paediatric setting and often do not survive into adolescence. In comparison to the adult population, adolescents tend to have a higher prevalence of GNs (7.2% vs. 61.3%), less hypertensive nephrosclerosis (29.3% vs. 4.4%) and less diabetic kidney disease (47.7% vs. 0.7%) [25, 32]. To our knowledge, in Africa there are no adolescent kidney registries, despite kidney disease being recorded as the 9th leading cause of death for this age group in SA [6, 25, 26, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. The unique patterns of kidney disease in AYA highlight the need for specialised nephrology training in conditions across paediatric and adult teaching platforms. This data assists our understanding of the kidney conditions found in this subgroup, enabling awareness and implementation of targeted strategies to improve clinical outcomes.

TABLE 3.

Variations in the aetiology of chronic kidney disease between different age group populations; and between well‐resourced countries and less‐resourced countries.

| Country date of study publication | Paediatrics | Adolescents | Adults | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WRC | LRC | WRC | LRC | WRC | LRC | |||||||||||

| USRDS [21] 2020 | Japan [22] 2015 | ANZ [23] 2019 | Egypt [24] 2015 | Sudan [25] 2009 | Nigeria [26] 2014 | SA [27] 2008 | USRDS [21] 2020 | ANZ [23] 2019 | Japan [22] 2015 | SA (this study) 2024 | USRDS [28] 2019 | Australia [29] 2020 | Nigeria [30] 2006 | SA [31] 2017 | ||

| Age represented (years) | 0–12 | 0–14 | 0–14 | 1–19 | 0–17 | 0–16 | 5–16 | 13–17 | 15–17 | 15–19 | 13–19 | > 21 | > 18 | 14–72 | > 18 | |

| Patient number in cohort | 2728 | 540 | 267 | 1018 | 205 | 53 | 126 | 2682 | 77 | 118 | 292 | 119 577 | 1244 | 153 | 10 257 | |

| CKD stages included in study | eGFR a < 50 | CKD Stages 1–5 | eGFR a < 50 | Kidney failure | CKD Stages 2–5 | |||||||||||

| Aetiology | Glomerulonephritis (%) | 21.2 | 14.9 | 16.9 | 15.3 | 25.4 | 77.4 | 52.1 | 36.6 | 32.0 | 29.6 | 61.3 | 7.2 | 17.6 | 41.2 | 10.3 |

| Primary GN | 16.0 | — | — | — | — | 25.9 | — | — | 40.7 | — | ||||||

| Secondary GN | 5.2 | — | — | — | — | 10.7 | — | — | 20.5 | — | ||||||

| CAKUT (%) | 39.8 | 42.2 | 33.3 | 46 | 17.5 | 21.2 | 9.5 | 21.8 | 16.0 | 30.5 | 12.7 | — | — | — | — | |

| Cystic/hereditary (%) | 13.6 | 23.7 | 12.3 | 6.7 | 6.8 | — | 3.4 | 11.3 | 7.0 | 18.6 | 8.2 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 6.5 | |

| Urological (%) | 4.4 | — | — | — | 9.3 | — | 14.1 | — | — | — | 2.0 | — | 1.6 | 9.1 | 9.1 | |

| TID (%) | — | — | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0 | — | 2.4 | — | — | — | — | |

| Hypertension (%) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 29.3 | 11.6 | 26.1 | 26.1 | |

| Diabetic kidney disease (%) | — | — | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | 3.0 | — | — | 47.7 | 30.2 | 13.1 | 13.1 | |

| Other causes (%) | 25.3 | 18.9 | 23.4 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 30.3 | 41 | 21.1 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 33.6 | 4.0 | 4.0 | |

Abbreviations: ANZ, Australia and New Zealand; CAKUT, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, eGFR, estimated glomerulofiltration rate; LRC, less‐resourced country; SA, South Africa; TID, tubulointerstitial disease; USRDS, United States Renal Data System; WRC, well‐resourced country.

Swartz formula estimation of glomerulofiltration rate (mL/min per 1.73 m2).

4.2. Composite Outcome in AYA Clinics

There is a lack of data regarding kidney outcome benefits for AYA attending transition clinics, outside the setting of kidney transplantation. This study demonstrated a trend towards less progression of CKD in the AYA attending KAYAC compared to those attending the adult kidney clinics. The heterogeneous spectrum of kidney disease in the two cohorts makes the trajectory outcome analysis of CKD complex. When the data was stratified by aetiology (GN vs. non‐GN), attending KAYAC still resulted in a better composite outcome (p = 0.09) (Figure 1b). However, UPCR, which is a well‐known risk factor for progression of CKD, was slightly higher at baseline in those attending the adult service (UPCR 0.13 vs. 0.04 g/mmol; p = 0.035), which may have contributed to outcomes. The improved composite outcome could be attributed to the KAYAC multi‐disciplinary holistic approach, with more frequent clinic visits, longer duration of consults, an adolescent‐friendly environment, intense focus on preservation of residual kidney function, education and targeted adherence interventions. KAYAC clinics provide an opportunity to implement early strategies to reduce the risk of progression of kidney disease in AYA, essential in settings where KRT access is scarce.

4.3. Mortality and Kidney Outcomes in AYA Clinics

In this study, the mortality was lower in the cohort attending KAYAC (2% vs. 12%; p = 0.007), despite diabetes mellitus being more frequent and a greater number of patients receiving KRT in this arm of the study. The leading cause of death in this CKD‐AYA cohort was infection (42.3%). This could be attributed to the high burden of infectious diseases in SSA, coupled with multi‐factorial reasons for late presentation to health care services [40]. This contrasts with multiple international studies that report cardiovascular death to be the main cause of death in CKD‐AYA patients (43.5%), with only a small proportion of mortality attributed to infection (5.2%) [22, 27]. In addition, there was a high proportion of patients with advanced CKD who died due to kidney failure (30.8%), reflecting the SA state sector health care system's restricted access to KRT. Acceptance into chronic KRT programmes is often linked to future transplantability and the ability to be adherent to immunosuppressive therapy [31]. Thus, non‐adherence, common amongst AYA, could affect eligibility for future KRT. In this study, a significant proportion of non‐adherence was detected in the total AYA sample (34%), with no difference between the two cohorts, highlighting the high rates of non‐adherence in this population.

4.4. Lost to Follow‐Up

LTFU is a global challenge in adolescents with complex chronic conditions [41, 42]. There are limited studies exploring the impact of LTFU in CKD, with most data reported in the setting of kidney transplantation [27]. The rates of LTFU in AYA post‐kidney transplantation are high, ranging from 28% to 32% [43, 44]. Lack of regular medical follow‐up is associated with poorer long‐term health outcomes [45]. In a SA study describing post‐transplant outcomes, non‐adherence to clinic visits was associated with graft failure [aHR 3.89; 95% CI, 1.76–8.60] [43, 44, 46]. This study highlights how those attending KAYAC had a reduction in LTFU in CKD patients, independent of their CKD stage and KRT status. Published global data report the predictors of LTFU to include a younger age (15–20 years), male gender, institutional transfer and more severe illness [43, 47, 48]. However, in our cohort, age and gender were not associated with LTFU.

The retention of patients and lower LTFU rates in KAYAC could be attributed to the strategic, multi‐disciplinary approach. This included peer‐led support groups, a consistent multi‐disciplinary team, pre‐ordered medication and an adolescent‐friendly clinic environment. The longer duration of contact with the health services may also have been protective against LTFU. This may be due to better rapport with treating clinicians over time and more opportunity for adherence interventions. The identification of those at risk for LTFU is important for targeted interventions and optimising long‐term kidney prognoses [49, 50].

4.5. Importance of Transition Clinics Worldwide

The International Society of Nephrology and the International Pediatric Nephrology Association released a joint consensus statement outlining the ideal transitional care of AYA living with CKD [51]. Failure to effectively transition patients from paediatric to adult nephrology services could lead to poor adherence, progression of kidney disease and allograft loss in the setting of kidney transplantation [15, 52, 53].

Successful transition from paediatric to adult healthcare centres positively impacts outcomes for AYA. Studies have shown benefits not only in terms of clinical parameters, but also in terms of adherence and reduction in healthcare costs. An early United Kingdom‐based study compared the impact of their Young Adult Clinic in comparison to their standard of care adult kidney clinics and found improved kidney allograft survival (log–rank test, p = 0.015) [54]. Subsequently, numerous studies have evaluated the implementation of transition transplant AYA clinics and have shown that those attending the clinic have significantly lower rates of eGFR decline, less allograft rejection, less allograft loss and lower mortality rates at 2–3‐year follow‐up [54, 55, 56, 57]. In addition, transition clinics are more economically feasible due to lower rates of hospital admissions and less need for recommencement of chronic dialysis due to allograft failure [55]. Additional studies have shown that well transitioned transplant recipients have lower rates of non‐adherent behaviour [56, 57].

More than a decade later, a systematic review assessed that there is a well‐established need for transitional care; however, current models are not standardised and may need to be adapted based on specific needs of the region [58]. No data from low‐ or middle‐income countries (LMICs) were included in this review; thus, the impact of implementing successful transitional health services in resource‐limited settings needs to be explored.

4.6. Importance of Transition Clinics in South Africa

The South African demographic population has a large proportion of young individuals, where AYA (aged 10–24) comprise over 25% of the population [59]. This is a growing population which will impact on kidney health care services.

In LMICs, the focus of transition clinics has centred around chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus and people living with HIV. Barriers in LMICs for adolescents to transition include the emotional and psychological burden for patients, lack of age‐appropriate healthcare, in addition to logistical and system‐related obstacles with resource mismatches [60, 61]. Factors identified to facilitate transition amongst AYA included readiness to transition, social support, skills development, multi‐disciplinary teams and transition co‐ordination [15, 60].

KAYAC has demonstrated that a meaningful low‐cost intervention in a South African setting, could improve progression of kidney disease, morality and LTFU in AYA. KAYAC is a structured, adolescent‐friendly service with many factors facilitating its growth and success in a low‐resourced setting. There are four key features which have facilitated this. First, the presence of constant paediatric and adult nephrology ‘champions’. These ‘champions’ create a bridge between paediatric and adult centres, in addition to raising awareness and advocating for the importance of transition clinics. These education drives were directed towards paediatric and adult medicine academic forums, with special invitation for senior management staff to attend. In our setting, the transition process begins at the paediatric centre with the adult nephrologist attending a joint clinic. Once adolescents are transitioned to KAYAC in the adult centre, paediatric nephrologists attend the clinic, contributing to the ‘familiar face in a different place’ phenomena. Second, KAYAC's philosophy is to be patient‐centred, flexible and pragmatic. The initial clinic was only for kidney transplant recipient adolescents (aged 13–19) and occurred bimonthly, for a 2‐hour period; the only time available on the clinical platform. Due to the clinic demonstrating improved attendance, adherence and positive qualitative feedback, the clinic grew. KAYAC has now expanded to weekly clinics, 3‐hour durations, driven by two nephrologists (supported by the both paediatric nephrology and adult nephrology teams), for all AYA CKD (aged 13–25), including those on KRT. Thirdly, KAYAC integrated the Better Together peer‐support group as an integral part of the clinic structure. This support group is led by peer mentors, who are essential in reaching young individuals. They support patients and encourage chronic illness acceptance, health self‐management skills and healthy lifestyle behaviours. This has been shown to have a positive impact on AYA, with those attending the group having higher individual‐level resilience scores (p = 0.004), more positive attitude towards their illness (p < 0.001), and to be less likely to screen positive for depression and anxiety [16]. Fourthly, KAYAC is supported by a holistic multi‐disciplinary team who are passionate about AYA and recognise the importance of tailoring care in nephrology to the individual. This has been beneficial in the implementation of strategic multi‐levelled interventions for non‐adherence. KAYAC is patient‐centred and attempts to meet the needs of the young individuals at the clinic. The factors at KAYAC which promoted strength and sustainability, include working as a team to overcome structural challenges and to ensure that the service is tailored to the local context.

5. Limitations

The strength of this study is that it highlights the positive impact a KAYAC has on kidney outcomes, death and LTFU. In addition, it expands our understanding of the spectrum of kidney disease of AYA in SA. Limitations included that it is a single centre retrospective study design, with its known shortcomings. Those attending KAYAC were predominantly (1) new patient referrals (from paediatric or adult services) and (2) a staggered transfer of existing AYA from the standard of care adult nephrology service. Selection bias could also have been introduced with the gradual transfer of existing AYA from the adult kidney clinics to KAYAC, where clinicians prioritised the transfer of AYA who were less adherent, requiring more frequent follow‐up care and more multi‐disciplinary support. The relatively small sample size and heterogeneous nature of the underlying kidney disease, as well as the slightly different baseline kidney function, limited the statistical analysis of subgroups and its potential influence on the outcomes. However, this data reflects real‐world kidney clinic outcomes in a low‐resourced setting.

The kidney transplant subset was relatively small for meaningful analysis. Those LTFU in the cohort did not re‐enter the healthcare system, therefore limiting the evaluation of this group's contribution towards CKD progression and mortality. Future research could prospectively evaluate the effectiveness of a dedicated KAYAC in a larger multi‐centred study, over a longer time period. Additionally, there is a need to better characterise the complexities of adherence and evaluate factors that could limit LTFU.

6. Conclusion

This study adds to the dearth of literature on the spectrum of AYA kidney disease in our setting. Adolescent nephrology is a growing field, and the principles of care should be incorporated in nephrology training. An innovative kidney transition clinic can foster a supportive environment while actively addressing high‐risk aspects of adolescent care. A dedicated KAYAC has the potential to improve kidney outcomes, lower mortality and reduce LTFU, with the impact shown as early as 1‐year and persisting at 5‐years when the study concluded. This is essential in a resource‐limited setting where access to KRT is restricted, and utilisation of transition clinics could be a cost‐effective intervention aimed at improving patient survival in young individuals with kidney disease.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1: Flow diagram demonstrating patient selection for the study population.

Table S1: Aetiology of primary kidney disease—the spectrum of chronic kidney disease in patients attending the kidney AYA clinic and the kidney adult clinic.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Division of Nephrology and Hypertension at Groote Schuur Hospital and the Paediatric division of Nephrology at Red Cross War Memorial Hospital for their ongoing support. Special thank you to the One‐to‐One Children's Fund and One to One Africa for their commitment and support of the Better Together programme.

Barday Z., Wearne N., Jones E. S. W., et al., “Clinical Outcomes of a Dedicated Kidney Adolescent and Young Adult Clinic (KAYAC) in South Africa,” Nephrology 30, no. 9 (2025): e70110, 10.1111/nep.70110.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. World Health Organization , “Adolescent and Young Adult Health WHO,” (2022), WHO Fact Sheet, https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/adolescents‐health‐risks‐and‐solutions.

- 2. World Health Organization , “Adolescent Mental Health,” (2021), WHO Fact Sheet, https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/adolescent‐mental‐health.

- 3. Moreno M. and Thompson L., “What Is Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine?,” JAMA Pediatrics 174, no. 5 (2020): 512, 10.1001/JAMAPEDIATRICS.2020.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ardissino G., Daccò V., Testa S., et al., “Epidemiology of Chronic Renal Failure in Children: Data From the ItalKid Project,” Pediatrics 111 (2003): e382–e387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ashuntantang G., Osafo C., Olowu W. A., et al., “Articles Outcomes in Adults and Children With End‐Stage Kidney Disease Requiring Dialysis in Sub‐Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review,” Lancet Global Health 5 (2017): e408–e417, 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Ferris M. E. D. G., “Adolescents and Emerging Adults With Chronic Kidney Disease: Their Unique Morbidities and Adherence Issues,” Blood Purification 31, no. 1–3 (2011): 203–208, 10.1159/000321854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Konrad K., Firk C., and UP , “Brain Development During Adolescence,” Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 110 (2013): 425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vigil P., Pablo J., Río D., et al., “Influence of Sex Steroid Hormones on the Adolescent Brain and Behavior: An Update,” Linacre Quarterly 83, no. 3 (2016): 308–329, 10.1080/00243639.2016.1211863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galvan A., Hare T., Voss H., Glover G., and Casey B. J., “Risk‐Taking and the Adolescent Brain: Who Is at Risk?,” Developmental Science 10, no. 2 (2007): F8–F14, 10.1111/J.1467-7687.2006.00579.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krb M., Brouhard B. H., Donaldson L. A., et al., “Cognitive Functioning in Children on Dialysis and Post‐Transplantation,” Pediatric Transplantation 4 (2000): 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Icard P., Hooper S. R., Gipson D. S., and FM , “Cognitive Improvement in Children With CKD After Transplant,” Pediatric Transplantation 14 (2010): 887–890, 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen K., Didsbury M., van Zwieten A., et al., “Neurocognitive and Educational Outcomes in Children and Adolescents With CKD: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 13, no. 3 (2018): 387–397, 10.2215/CJN.09650917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mayosi B. M. and Benatar S. R., “Health and Health Care in South Africa—20 Years After Mandela,” New England Journal of Medicine 371, no. 14 (2014): 1344–1353, 10.1056/NEJMSR1405012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wearne N., Okpechi I. G., and Swanepoel C. R., “Nephrology in South Africa: Not Yet Ubuntu,” Kidney Diseases 5, no. 3 (2019): 189–196, 10.1159/000497324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barday Z., Davidson B., Harden P., et al., “Kidney Adolescent and Young Adult Clinic: A Transition Model in Africa,” Pediatric Transplantation 28, no. 2 (2024): e14690, 10.1111/PETR.14690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harrison A., Mtukushe B., Kuo C., et al., “Better Together: Acceptability, Feasibility and Preliminary Impact of Chronic Illness Peer Support Groups for South African Adolescents and Young Adults,” Journal of the International AIDS Society 26, no. S4 (2023): e26148, 10.1002/JIA2.26148/FULL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swartz S., Deutsch C., Makoae M., et al., “Measuring Change in Vulnerable Adolescents: Findings From a Peer Education Evaluation in South Africa,” SAHARA‐J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/Aids 9, no. 4 (2012): 242–254, 10.1080/17290376.2012.745696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inker L. A., Coresh H. T., Sang D. C., et al., “New Creatinine‐ and Cystatin C‐Based Equations to Estimate GFR Without Race,” New England Journal of Medicine 385, no. 19 (2021): 1737–1749, 10.1056/NEJMoa2102953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levin A., Agarwal R., Herrington W. G., et al., “International Consensus Definitions of Clinical Trial Outcomes for Kidney Failure: 2020,” Kidney International 98, no. 4 (2020): 849–859, 10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siew E. D., Abdel‐Kader K., Perkins A. M., et al., “Timing of Recovery From Moderate to Severe AKI and the Risk for Future Loss of Kidney Function,” American Journal of Kidney Diseases 75, no. 2 (2020): 204–213, 10.1053/J.AJKD.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hattori M., Sako M., Kaneko T., et al., “End‐Stage Renal Disease in Japanese Children: A Nationwide Survey During 2006‐2011,” Clinical and Experimental Nephrology 19 (2015): 933–938, 10.1007/s10157-014-1077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferris M. E., Miles J. A., and Seamon M. L., “Adolescents and Young Adults With Chronic or End‐Stage Kidney Disease,” Blood Purification 41, no. 1–3 (2016): 205–210, 10.1159/000441317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Safouh H., Fadel F., Essam R., Salah A., and Bekhet A., “Causes of Chronic Kidney Disease in Egyptian Children,” Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation 26, no. 4 (2015): 806–809, 10.4103/1319-2442.160224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ali E. T. M. A., Abdelraheem M. B., Mohamed R. M., Hassan E. G., and Watson A. R., “Chronic Renal Failure in Sudanese Children: Aetiology and Outcomes,” Pediatric Nephrology 24, no. 2 (2008): 349–353, 10.1007/S00467-008-1022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saran R., Robinson B., Abbott K. C., et al., “US Renal Data System 2019 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States,” American Journal of Kidney Diseases 75, no. 1 (2020): A6–A7, 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Department of Statistics South Africa Republic of SA , “The Young and the Restless—Adolescent Health in SA,” (2022), Statistics South Africa, https://www.statssa.gov.za.

- 27. Hansrivijit P., Chen Y. J., Lnu K., et al., “World Journal of Nephrology Prediction of Mortality Among Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review Conflict‐Of‐Interest Statement: PRISMA 2009 Checklist Statement,” World Journal of Nephrology 10, no. 4 (2021): 59–75, 10.5527/wjn.v10.i4.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alebiosu C. O., Ayodele O. O., Abbas A., and Olutoyin I. A., “Chronic Renal Failure at the Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria,” African Health Sciences 6, no. 3 (2006): 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Asinobi A. O., Ademola A. D., Ogunkunle O. O., and Mott S. A., “Paediatric End‐Stage Renal Disease in a Tertiary Hospital in South West Nigeria,” BMC Nephrology 15, no. 25 (2014): 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Australian Government: Institute of Health and Welfare , “Chronic Kidney Disease: Australian Facts, Summary—Australian Institute of Health and Welfare,” (2022), https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic‐kidney‐disease/chronic‐kidney‐disease.

- 31. Moosa M. R., “The State of Kidney Transplantation in South Africa,” South African Medical Journal 109, no. 4 (2019): 235–240, 10.7196/SAMJ.2019.VL09I4.13548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. USRDS , “United States Renal Data System: ESRD Among Children and Adolescents,” 2020. Annual Data Report.

- 33. SAHMRI , “ANZDATA: Dialysis and Transplant Registry Annual Report,” (2021), https://www.anzdata.org.au/anzdata/publications/reports/.

- 34. ANZDATA , “Paediatric Patients With End‐Stage Kidney Disease Requiring Renal Replacement Therapy,” (2019), ANZDATA Annual Report, http://www.anzdata.org.au.

- 35. Okpechi I. G., Ameh O. I., Bello A. K., Ronco P., Swanepoel C. R., and Kengne A. P., “Epidemiology of Histologically Proven Glomerulonephritis in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” PLoS One 11, no. 3 (2016): e0152203, 10.1371/journal.pone.0152203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maoujoud O., Aatif T., Bahadi A., et al., “Regional Disparities in Etiology of End‐Stage Renal Disease in Africa,” Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation 24, no. 3 (2013): 594–595, 10.4103/1319-2442.111078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Crowley‐Nowick P. A., Julian B. A., Wyatt R. J., et al., “IgA Nephropathy in Blacks: Studies of IgA2 Allotypes and Clinical Course,” Kidney International 39, no. 6 (1991): 1218–1224, 10.1038/ki.1991.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seedat Y. K., Nathoo B. C., Parag K. B., Naiker I. P., and Ramsaroop R., “IgA Nephropathy in Blacks and Indians of Natal,” Nephron 50, no. 2 (1988): 137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Okpechi I., Swanepoel C., Duffield M., et al., “Patterns of Renal Disease in Cape Town South Africa: A 10‐Year Review of a Single‐Centre Renal Biopsy Database,” Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 26 (2011): 1853–1861, 10.1093/ndt/gfq655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rudd K. E., Johnson S. C., Agesa K. M., et al., “Global, Regional, and National Sepsis Incidence and Mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study,” Lancet 395 (2020): 200–211, 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Farirai J. T. and Cooper D., “Predictors of Lost‐To‐Follow‐Up Amongst Adolescents on Antiretroviral Therapy in an Urban Setting in Botswana,” (2018), University of the Western Cape.

- 42. Skogby S., Bratt E. L., Johansson B., Moons P., and Goossens E., “Discontinuation of Follow‐Up Care for Young People With Complex Chronic Conditions: Conceptual Definitions and Operational Components,” Health Services Research 21 (2021): 1343, 10.1186/s12913-021-07335-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Melanson T. A., Mersha K., Patzer R. E., and George R. P., “Loss to Follow‐Up in Adolescent and Young Adult Renal Transplant Recipients,” Transplantation 105, no. 6 (2021): 1326–1336, 10.1097/TP.0000000000003445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hung Y. C., Williams J. E., Bababekov Y., Rickert A. G., Chang D. C., and Yeh H., “Surgeon Crossover Between Pediatric and Adult Centers Is Associated With Decreased Rate of Loss to Follow‐Up Among Adolescent Renal Transplantation Recipients Ya‐Ching,” Pediatric Transplantation 23 (2019): 1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Blackwell C. K., Elliott A. J., Ganiban J., et al., “General Health and Life Satisfaction in Children With Chronic Illness,” Pediatrics 143, no. 6 (2019): e20182988, 10.1542/PEDS.2018-2988/-/DCSUPPLEMENTAL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chhiba P. D., Moore D. P., Levy C., and Do Vale C., “Factors Associated With Graft Survival in South African Adolescent Renal Transplant Patients at CMJAH Over a 20‐Year Period (GRAFT‐SAT Study),” Pediatric Transplantation 26, no. 1 (2022): 1–6, 10.1111/petr.14148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Geng E. H., Glidden D. V., Emenyonu N., et al., “Tracking a Sample of Patients Lost to Follow‐Up Has a Major Impact on Understanding Determinants of Survival in HIV‐Infected Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy in Africa,” Tropical Medicine & International Health 15, no. Suppl 1 (2004): 63–69, 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Id E., dorice T., Kishimba R., Njau P., and Revocutus B., “Predictors of Loss to Follow Up From Antiretroviral Therapy Among Adolescents With HIV/AIDS in Tanzania,” PLoS One 17 (2022): 1–14, 10.1371/journal.pone.0268825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Graves M. M., Roberts M. C., Abpp P., Rapoff M., and Boyer A., “The Efficacy of Adherence Interventions for Chronically Ill Children: A Meta‐Analytic Review,” Journal of Pediatric Psychology 35, no. 4 (2010): 368–382, 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Atger‐Lallier L., Guilmin‐Crepon S., Boizeau P., et al., “Factors Affecting Loss to Follow‐Up in Children and Adolescents With Chronic Endocrine Conditions,” Hormone Research in Pædiatrics 92, no. 4 (2006): 254–261, 10.1159/000505517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Watson A. R., Harden P. N., Ferris M. E., Kerr P. G., Mahan J. D., and Ramzy M. F., “Transition From Pediatric to Adult Renal Services: A Consensus Statement by the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) and the International Pediatric Nephrology Association (IPNA),” Kidney International 80 (2011): 704–707, 10.1038/ki.2011.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kaboré R., Couchoud C., Macher M. A., et al., “Age‐Dependent Risk of Graft Failure in Young Kidney Transplant Recipients,” Transplantation 101, no. 6 (2017): 1327–1335, 10.1097/TP.0000000000001372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ritchie A. G., Clayton P. A., Mcdonald S. P., Kennedy S. E., and Kennedy S., “Age‐Specific Risk of Renal Graft Loss From Late Acute Rejection or Non‐Compliance in the Adolescent and Young Adult Period (Summary at a Glance),” 23 (2017): 585–591, 10.1111/nep.13067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Harden P. N., Walsh G., Bandler N., et al., “Bridging the Gap: An Integrated Paediatric to Adult Clinical Service for Young Adults With Kidney Failure,” BMJ (Online) 344, no. 7861 (2012): 1–8, 10.1136/bmj.e3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Prestidge C., Romann A., Djurdjev O., and Matsuda‐Abedini M., “Utility and Cost of a Renal Transplant Transition Clinic,” Pediatric Nephrology 27, no. 2 (2012): 295–302, 10.1007/S00467-011-1980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weitz M., Heeringa S., Neuhaus T. J., Fehr T., and Laube G. F., “Standardized Multilevel Transition Program: Does It Affect Renal Transplant Outcome?,” Pediatric Transplantation 19 (2015): 691–697, 10.1111/petr.12570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mcquillan R. F., Toulany A., Kaufman M., and Schiff J. R., “Benefits of a Transfer Clinic in Adolescent and Young Adult Kidney Transplant Patients,” Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease 2 (2015): 81, 10.1186/s40697-015-0081-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wildes D. M., Costigan C. S., Kinlough M., et al., “Transitional Care Models in Adolescent Kidney Transplant Recipients—A Systematic Review,” Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 38, no. 1 (2023): 49–55, 10.1093/NDT/GFAC175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Crowling N., “Share of Teenage Pregnancies in South Africa 2018–2022,” (2023), STATISTA, https://www.statista.com/statistics.

- 60. Jones C., Ritchwood T. D., and Taggart T., “Barriers and Facilitators to the Successful Transition of Adolescents Living With HIV From Pediatric to Adult Care in Low and Middle‐Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Policy Analysis,” AIDS and Behavior 23, no. 9 (2019): 2498–2513, 10.1007/S10461-019-02621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Narla N. P., Ratner L., Viera Bastos F., et al., “Paediatric to Adult Healthcare Transition in Resource‐Limited Settings: A Narrative Review,” BMJ Paediatrics Open 5 (2021): 1059, 10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Flow diagram demonstrating patient selection for the study population.

Table S1: Aetiology of primary kidney disease—the spectrum of chronic kidney disease in patients attending the kidney AYA clinic and the kidney adult clinic.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.