Abstract

Outrigger canoe paddling (“paddling”) is a culturally and regionally relevant physical activity (PA) in Hawai‘i and the Pacific with potential for public health promotion and disease prevention, yet paddling remains understudied from a public health perspective. This study explored the meaning of paddling across levels of the social–ecological model (SEM) using qualitative methods. The study goal was to develop a research base and inform scholarship about participation in paddling for public health. A total of 1066 Hawai‘i residents (18 + years) completed an online or phone survey about culturally relevant PA. Among them, 362 self-identified as current or former paddlers and responded to the open-ended question: ‘What does outrigger canoe paddling mean to you?’. Qualitative analysis was conducted using a deductive–inductive approach. Findings revealed themes spanning an adapted SEM: (i) intrapersonal—fun, relaxation, PA; (ii) proximal connections—relationships with people past and present; (iii) distal connections—teams, canoe(s), and the ocean “humanized” as part of the community; (iv) environmental—immersion in the natural world; (v) macrosocial—culture, traditions, ancestral knowledge; and (vi) spiritual—life symbolism and spirituality. Many respondents reported multiple levels of the SEM in their responses, which can be seen in this illustrative quote, sharing that padding meant: ‘…physical health, emotional balance, spiritual connection with ocean and self, building trust and communication with a team.’ Paddling fosters health, well-being, and community across SEM levels, making it a strong candidate for PA interventions aligned with best-practice public health guidelines.

Keywords: physical activity, public health, disease prevention, determinants of health, evidence-based health promotion

Contribution to Health Promotion.

Outrigger canoe paddling connects participants to their heritage and culture, boosting motivation for physical activity (PA).

Paddling supports a strong connection to ancestors and fostering resilience.

Cultural ties, rather than just health goals, increase long-term participation in PA.

Addressing multiple layers of the extended social–ecological model including spiritual elements can improve health outcomes and support well-being.

Paddling aligns with best-practice guidelines and may serve as an effective intervention to promote PA.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are on the rise. NCDs are the leading cause of death in many countries (Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation 2024) and are mostly preventable. Inequities are found within NCD-related risks and outcomes for many racial/ethnic minorities and in rural populations globally (Deng et al. 2023) and in the USA (Niakouei et al. 2020).

Physical activity (PA) is an important adjustable risk factor for NCDs (Batty et al. 2010) but is decreasing (WHO 2023). Globally, one in three adults is not sufficiently active (WHO 2024). In the USA, nearly 80% of the population does not meet US Department of Health and Human Services’ PA guidelines (An et al. 2016). If current levels of physical inactivity remain unchanged, almost 500 million new cases of preventable NCDs are projected to occur by 2030 (Santos et al. 2022). Public health efforts are underway to increase PA for these reasons.

Racial/ethnic minorities, such as Native Hawaiian (NH) and Pacific Islanders (PI), and those from rural communities have lower (reported) rates of PA, while often experiencing a higher disease burden according to population-level surveillance instruments (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2004, Mau et al. 2009, Sentell et al. 2023). Such measurement tools may not always reflect Indigenous understandings or expressions of PA and may thus undercount actual PA engagement. It is thus critical to build our scientific understanding of PA that is important to Indigenous communities.

NH are the Indigenous People of Hawai‘i. PI have origins from the geographic regions of Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia, including the Indigenous People of Guåhan (Guam), Samoa, French Polynesia, Tonga, and many other island nations and territories. NH and PI have many cultural strengths and assets and face health and social inequities attributable to factors including discrimination, colonialism, militarization, and exploitation by foreign powers (Spickard et al. 2002, Kaholokula et al. 2009). Innovative PA strategies that consider cultural interests and values for all populations are needed to reduce NCD burdens and promote public health.

Research has highlighted culturally relevant PA, described as sport or physical practice with its origin in the culture of the population, as an important means to increase PA and improve health outcomes (Conn et al. 2013, Usagawa et al. 2013, Robinson et al. 2016, Kaholokula et al. 2018, Rio and Saligan 2023). Ethnic dance has been one focal area of this scholarship (Kaholokula et al. 2018, Zhu et al. 2018, Heil et al. 2019, Solla et al. 2019). Notable research exists on the cardiometabolic and hypertension control benefits of the NH dance hula, for NH and other PI in the state of Hawai‘i and on the US continent (Usagawa et al. 2013, Look et al. 2014, Maskarinec et al. 2015, Kaholokula et al. 2017, 2021). The benefits of culturally relevant PA may extend beyond communities of origin by providing opportunities to connect meaningfully to their new home, including learning and embracing the culture.

Outrigger canoe paddling (“paddling”) has promise as a health-promoting PA generally and specifically for NH and PI, but is understudied (Canyon and Sealey 2016, Severinsen and Reweti 2021, Reweti and Severinsen 2022, Sentell et al. 2023, Kanemasu 2024, 2025). Paddling is a culturally, community, and ocean grounded PA in Hawai‘i (Huffer 2017). It was historically very common across the islands. However, after European missionaries arrived in Hawai‘i in 1820, paddling became a prohibited activity (Kai Ikaika n.d.). In 1875, paddling remerged when King David Kalakaua reinstated it as an organized sport during the Hawaiian Renaissance movement, and in 1908, the first paddling club was established (Peattie et al. 2023). Since then, paddling has continued to grow in popularity. Today, paddling is the official team state sport for Hawaiʻi (Hawaii State Capitol 1986) and a popular pastime. According to one study, overall lifetime engagement in paddling in Hawai‘i was 19.8%, with higher rates of paddling seen on the rural neighbor islands compared with the urban ‘Oahu (Sentell et al. 2023). Particularly, high engagement over the lifetime was seen in NH (41.5%) and PI (31.5%) respondents (Sentell et al. 2023). More details about paddling are given in Supplementary Appendix A.

Qualitative research on paddling can help illuminate the meaning and importance of this culturally relevant PA to improve health promotion efforts. The study goal was to develop a research base and inform scholarship about participation in paddling for public health. The research question was: what meaning do participants in the state of Hawai‘i give to their participation in outrigger canoe paddling that is relevant to public health? Our hypothesis was that respondents would describe paddling as having multifaceted significance, with rich relevance for health promotion, not only in terms of PA but also for cultural and community connection. This study was based on, and inspired by, previous qualitative research on hula, which found that the practice holds multifaceted health value, encompassing the mind, body, and spirit (Look et al. 2023).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research collaboration

This work was conceptualized and implemented by a Hawai‘i-based team that is part of a long-term academic–community partnership for impactful public health promotion (Agner et al. 2020). The authors’ identities include NH, PI, paddler, student, Indigenous researcher, Department of Health employee, and community member.

Survey development

A survey was developed for this project, building on established surveillance tools and incorporating community input following a previous quantitative study that indicated interest in gaining deeper insights on these practices for community health. Variables from population-level surveys were included to allow for comparability of results (e.g. age, gender). Additionally, an open-ended question was codesigned from conversations with community members and scholars to elicit insights into the relevance of this activity to public health. Thus, we included a question focused on the “meaning” of this activity.

Theory

Our study was framed by the social–ecological model (SEM), which is rooted in Bronfenbrenner’s theory of human development as a dynamic interaction between the growing human organism and their changing environment across the lifespan (Bronfenbrenner 1977). The SEM built on Bronfenbrenner’s characterization of the ecological environment within a nested arrangement of structures and has been a fruitful model for research into PA, showcasing how PA can impact health across multiple levels of influence from micro to macro. McLeroy et al. (1988) summarized public health research across the levels of the SEM in 1988, in support of moving away from a victim-blaming perceptive to one that recognizes that a person is part of many layers in society over which he/she can have more or less control. The SEM is also a useful model for interpreting and contextualizing qualitative findings within public health promotion, including among Indigenous Peoples (Black et al. 2008, Nelson et al. 2010, Willows et al. 2012). Moreover, the SEM has been successfully adapted to health promotion research among Indigenous People by including historical factors, such as colonization and dispossession of traditional lands (Nelson et al. 2010, Willows et al. 2012).

Survey fielding

English-speaking Hawai‘i residents aged 18 + years (n = 1066) from an existing panel by a local survey research organization (SMS Research) completed a survey administered online or by phone. This survey included open-ended questions on the meaning of four culturally and regionally relevant PA that are of particular interest in the state for health promotion (paddling, surfing, hula, and spearfishing). All respondents were asked if they participated in each activity: ‘Over your LIFETIME, how much have you participated in [each activity]?’. Response options included: never, almost never, sometimes, often, and very often. Respondents who reported participating in each activity “sometimes,” “often,” or “very often” over their lifetime were subsequently asked the open-ended question about the meaning of that participation.

This study focused on responses from individuals who self-identified as former and/or current paddlers (n = 362; 34% of the total sample). These were respondents who reported participating in paddling “sometimes,” “often,” or “very often” over their lifetime. They were subsequently asked the open-ended question: ‘What does outrigger canoe paddling mean to you?’. Responses to this question were used for the qualitative analysis. The inclusion of this question was guided by our hypothesis that respondents would describe paddling as having multifaceted health value.

Qualitative analyses

Using a deductive–inductive approach, two of three independent coders evaluated responses about the meaning of paddling using an adapted SEM from Nelson et al (2010). This framework was chosen for its granularity and relevance to Indigenous Peoples in the Pacific. It included six levels that organize and synthesize influences on health, ranging from narrow to broad: (i) genetic characteristics; (ii) individual characteristics; (iii) proximal social connections; (iv) distal social connections; (v) environmental factors; and (vi) macrosocial factors, including historical factors as previously adapted by Nelson et al. (2010).

The three coders (S.M.S., J.F., and C.S.H.) had expertise in PA and chronic disease, social factors in health, and/or Asian and PI communities. One coder (S.M.S.) is also a long-term paddler, contributing additional contextual insight. At least two coders analyzed all qualitative responses to the open-ended question across the SEM levels. If there were discrepancies, a third coder reviewed. The senior author was also available to resolve discrepancies.

Both coders first reviewed and coded all materials independently and blindly. This included separately reading and coding excerpts from the open-ended responses. Coders met at least monthly (often weekly) from November 2022 to March 2023 and used an iterative approach to confirm themes and subcodes within main codes (SEM levels). These codes and themes were then organized within the SEM framework.

There were three main rounds of coding: (i) familiarization and code identification; (ii) development of a SEM coding system collaboratively established by both coders, while allowing for the addition of new codes by either coder. Based on findings, SS suggested an adapted SEM to the cocoder. This coding system was presented and discussed with an additional coauthor (the senior author) for feedback and considerations, which confirmed the final model to be used; and (iii) final coding, involving recoding for emerged themes with new codes added, followed by consensus coding on the agreed upon adapted SEM. Coders reviewed excerpts together as needed to reach consensus on the appropriate SEM level for each response. Final consensus coding was used for analyses (Olson et al. 2016, Richards and Hemphill 2018). Intercoder reliability was 100% after the final iteration. This project was determined to be exempt from human subjects review by the University of Hawaiʻi Institutional Review Board (protocol ID 2022–00449).

Self-reported demographic data were also collected, including gender (male, female, other), race/ethnicity (in alphabetical order: Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, Other, Latino, Japanese, Other PI, White), age group (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75+ years), education level (less than high school [HS], HS or General Education Development Test [GED], Some College, College Graduate), county (‘Oahu, Hawai‘i Island, Maui, Kauai), and income (under $15 000, $15 000–$24 999, $25 000–$49 999, $50 000–$74 999, $75 000–$124 999, $12 500–$1999 999, $200 000 and more). Health-related variables included the number of self-reported health conditions (none, one, two, three, and more) and body mass index (normal, overweight, obese, and underweight). The survey also asked who participants paddled with (with school classmates, family, friends, a club, church group, or other) and their paddling frequency (sometimes, often, very often). R was used for descriptive analysis.

RESULTS

Of the 362 respondents who self-identified as paddlers, only nine (2.5%) did not respond to the open-ended question. Demographic characteristics of the 353 paddlers who did respond are presented in Table 1. Lifetime engagement in paddling among respondents ranged from sometimes (n = 221, 62%) to often (n = 71, 20%) and very often (n = 61, 17%). The sample included 229 (65%) female and 124 (35%) male participants. Most paddlers identified as NH (n = 116, 47%), followed by White (n = 69, 20%), Filipino (n = 30, 9%), Japanese (n = 25, 7%), Other PI (n = 17, 5%), Latino (n = 12, 3%), Chinese (n = 10, 3%), Other Asian (n = 7, 2%), and other (n = 17, 5%). Twenty-four percent of paddlers reported having one chronic condition (24%), 19% reported two, and 9% reported three or more. The sample was evenly split between urban and rural residents, with 176 (50%) from urban areas and 177 (50%) from rural areas.

Table 1.

Demographics of those who self-identified as paddlers (n = 353).

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex/gender | Female | 229 (64.87) |

| Male | 124 (35.13) | |

| Race/ethnicity | Native Hawaiian | 166 (47.03) |

| White | 69 (19.55) | |

| Filipino | 30 (8.50) | |

| Japanese | 25 (7.08) | |

| Pacific Islander | 17 (4.82) | |

| Chinese | 10 (2.83) | |

| Latino | 12 (3.40) | |

| Other Asian | 7 (1.98) | |

| Other | 17 (4.82) | |

| Age category (years) | 18–24 | 60 (17.00) |

| 25–34 | 91 (25.78) | |

| 35–44 | 71 (20.11) | |

| 45–54 | 43 (12.18) | |

| 55–64 | 44 (12.46) | |

| 65–74 | 23 (6.52) | |

| 75+ | 21 (5.95) | |

| Education level | Less than high school | 14 (3.97) |

| High school or GED* | 100 (28.33) | |

| Some college | 136 (38.53) | |

| College graduate | 103 (29.18) | |

| Hawaiʻi county | Oʻahu | 176 (49.86) |

| Hawaiʻi | 77 (21.81) | |

| Maui | 62 (17.56) | |

| Kauaʻi | 38 (10.76) | |

| Number of health conditions | None | 166 (47.03) |

| One | 86 (24.36) | |

| Two | 68 (19.26) | |

| Three+ | 33 (9.35) | |

| Self-reported body mass index | Normal | 189 (54.62) |

| Overweight | 116 (33.53) | |

| Obese | 16 (4.62) | |

| Underweight | 25 (7.23) | |

| Income | < $15 000 | 41 (11.61) |

| $15 000 to $24 999 | 54 (15.30) | |

| $25 000 to $49 999 | 79 (22.38) | |

| $50 000 to $74 999 | 70 (19.83) | |

| $75 000 to $124 999 | 66 (18.70) | |

| $125 000 to $199 999 | 30 (8.50) | |

| $200 000 or more | 13 (3.68) | |

|

Paddling with whom?

(‘not mutually exclusive’) |

At School | 78 (22.10) |

| With Family | 139 (39.38) | |

| With Friends | 176 (49.86) | |

| With a Club | 164 (46.46) | |

| Church Group | 13 (3.68) | |

| Other | 10 (2.83) | |

| Paddling frequency | Sometimes | 221 (62.60) |

| Often | 71 (20.11) | |

| Very often | 61 (17.28) | |

*General Education Development Test (high school equivalence).

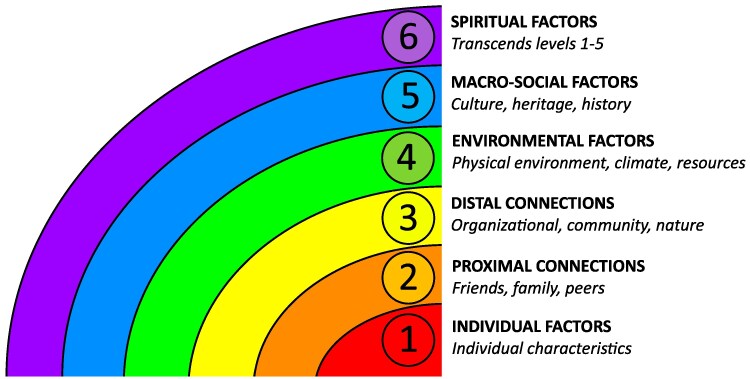

The final SEM used in this analysis is presented in Fig. 1. Of the six levels described by Nelson et al., the first level, genetic characteristics, was excluded, as it was not referenced by any participants. However, during the familiarization phase, the coders identified a strong emergent theme related to spirituality and added a new sixth level: “spiritual factors.” Thus, the final adapted SEM consists of six levels from most narrow to most broad: (i) individual characteristics; (ii) proximal social connections; (iii) distal social connections; (iv) environmental factors; (v) macrosocial factors (including historical); and (vi) spiritual factors. Table 2 briefly explains each level, the themes that emerged within them, the frequency of codes per level, and illustrative quotations.

Figure 1.

SEM adapted from adapted from Nelson et al. (2010), showing the range of meanings of paddling identified by respondents from intrapersonal, interpersonal, environmental, and macrosocial to spiritual factors.

Table 2.

| Level number and name | Description | Code frequency | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6. Spiritual factors | Spiritual factors transcending the previous SEM levels 1–5 | 27 | Mana through team effort (…) how respect unites people and gives us the strength to overcome the biggest waves that life sends us. (…) The concepts that we learned in practices and races that what we learned and the mana‘o that was shared is to be used in ALL aspects of life not just in paddling. |

| 5. Macrosocial factors | Macrosocial factors including culture, heritage, and history | 75 | Love and respect for the culture. It is a very strong outlet where people, locals, community members can (…) experience values and teachings of the culture in Hawai‘i. |

| 4. Environmental factors | Environmental factors including the physical environment, climate, and resources, extending the direct connection to nature (when humanized) from level 3 to the physical environment | 87 | It is by far the coolest, refreshing thing to do especially on hot days. It’s fun and a good way to catch fish. |

| 3. Distal connections | Distal social connections including relationships formed through organizational connections, community, and with nature (e.g. a connection with the wa‘a (canoe) and the ocean) | 170 | It means getting to stand by your team and work as one. It means being connected to kai (sea). |

| 2. Proximal connections | Proximal social connections including those with friends, family, and peers | 56 | Friendship. |

| 1. Intrapersonal factors | Intrapersonal factors including individual characteristics (e.g. psychosocial, behavioral, and other personal factors about an individual) | 261 | It was a good outlet to positively release stress. It taught a lot of discipline and drive. It means as a way to escape and have a good time with peace. |

Level 1 refers to intrapersonal factors or individual characteristics, including the psychosocial, behavioral, and other personal factors about an individual.

Level 2 refers to proximal social connections including those with friends, family, and peers.

Level 3 refers to relationships formed through organizational connections, community, and connection with nature (as humanized by participant as part of the community). In NH culture especially, people often have personal relationships with natural elements (McCubbin and Marsella 2009).

Level 4 refers to environmental factors including the physical environment, climate, and resources, extending the connection to the elements from layer 3. Responses referring to nature in this level reflect more indirect relationships to nature than level 3.

Level 5 refers to macrosocial factors including culture, heritage, and history.

Level 6 refers to transcending meaning beyond the other five levels, including spirituality.

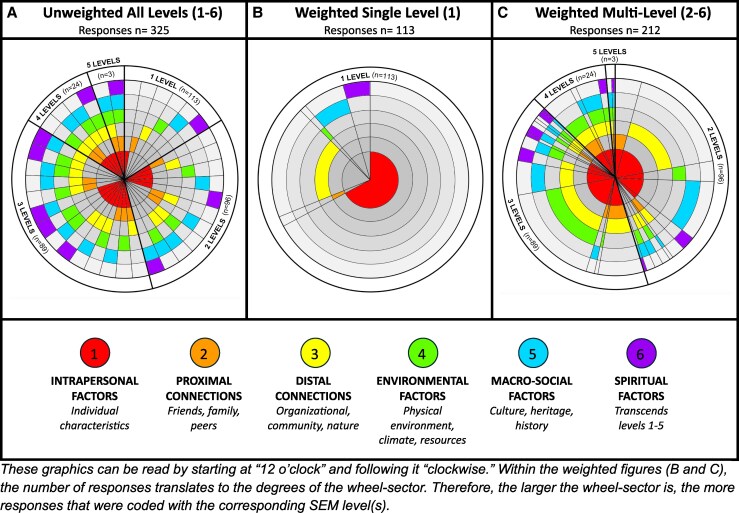

One hundred and thirteen respondents gave answers that were coded into a single SEM level only (Fig. 2b). The distribution of responses was as follows: level 1: intrapersonal level (76 responses), level 2: proximal connections (2 responses), level 3: distal connections (21 responses), level 4: environmental (1 response), level 5: macrosocial factors (8 responses), and level 6: spiritual (5 responses). More than half (60%) of respondents stated more than one level in their responses (Fig. 2b). Combining both single-level and multi-level coded responses, the most frequent codes (total of 676 codes assigned) were from level 1 (n = 261), followed by level 3 (n = 170), level 4 (n = 87), level 5 (n = 75), level 2 (n = 56), and finally level 6 (n = 27) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of visualizations of SEM levels found in the paddlers’ responses: (a) unweighted responses across all six levels and weighted responses split into (b) single-level responses and (c) multi-level response combinations. The unweighted visualization (a) solely reflects which SEM combinations were present. The weighted visualizations (b and c) illustrate the frequency of the SEM combinations in the size of each wheel sector.

Individual social–ecological model levels

Level 1: intrapersonal factors (individual characteristics) (261 total responses)

Themes that emerged in this category included paddling as a means of physical exercise, staying active, and getting fit, as well as fun, relaxation, personal enjoyment, and learning. Some respondents focused on the physical benefits of paddling, such as one who stated, ‘I love paddling—it is a great exercise and really gets your blood pumping.’ Others described more holistic intrapersonal benefits that extended beyond PA: ‘It was a good outlet to positively release stress. It taught a lot of discipline and drive. It means as a way to escape and have a good time with peace.’

Within level 1, the coders identified two subthemes: “fun” and “being in shape.” One hundred nine paddlers described paddling as fun and freeing, something they enjoy doing, that provides relaxation, and contributes to a sense of peace and balance in their lives. One hundred sixteen paddlers emphasized paddling as a form of exercise, a way to build physical fitness, and a means of “being in shape.” Thirty paddlers mentioned both subthemes. For example, ‘It was really fun to do and definitely a great exercise’; ‘Not only is it fun, but it is also a very good workout’; ‘… a fun skill (outrigger canoe paddling) that gives you a great workout from head to toe’; ‘Getting stronger and a fun activity.’

Level 2: proximal connections (friends, family, peers) (56 total responses)

For many respondents, paddling was a vehicle for social connection. Some described it as a family tradition, an activity that brought their family together regularly. Others viewed paddling as a fun activity to do with friends, or as an opportunity to build new connections and relationships. For one paddler, the meaning of paddling could be summed up in one word: ‘Friendship.’ Another mentioned ‘(…) hang out with friends and family.’

Level 3: distal connections (organizational, community, nature) (170 total responses)

This level captured themes related to broader social structures and connections beyond immediate relationships. Organizational connections included church-, club-, and school-organized paddling teams and events. Many paddlers emphasized that the deeper meaning of paddling lay in the sense of community created, through shared experiences of fellowship, camaraderie, and teamwork. For example, one paddler said, ‘It means getting to stand by your team and work as one.’ Many respondents reflected on how paddling deepened their connection to nature.

Level 4: environmental factors (physical environment, climate, resources) (87 total responses)

Responses coded at this level reflected the importance of the natural physical environment as a setting for paddling. Many participants highlighted their enjoyment of being outdoors in nature, as opposed to indoor or built environments like gyms: ‘Being out in the water made me feel proud,’ and ‘Exercise, scenery, fresh air.’ Others referenced the climate, describing paddling as refreshing and well-suited for warm weather: ‘It is by far the coolest, refreshing thing to do especially on hot days.’ For some, paddling was a means of catching fish as a resource: ‘It’s fun and a good way to catch fish.’

Level 5: macrosocial factors (culture, heritage, history) (75 total responses)

For many respondents, culture, heritage, and history were deeply intertwined, reflecting both personal identity and broader community values. For example, paddling was often described as a meaningful expression of cultural pride and continuity: ‘Love and respect for the culture.’ Another emphasized: ‘It is a very strong outlet where people, locals, community members can get together and experience values and teachings of the culture in Hawai‘i.’

In this level, the meaning of paddling is tied to time, connecting the past, present, and future. Paddlers referenced history and ancestry: ‘It is the way ancestors sailed’ and ‘How the islands came to be.’ Others spoke of their personal, present-day connection to tradition: ‘Connection to my roots’ and ‘Traveling as our ancestors did.’ Paddling was also described as a vehicle for learning about oneself, about heritage, and about Indigenous knowledge systems embedded in the practice. As one paddler explained: ‘It is a fun way to be active with my fellow peers and learn about my ancestors. Typically, our school taught us about navigating through stars and how to wayfind on the ocean. Not only did I learn paddling, but the key knowledge to wayfinding and the astrological benefits there is to knowing survival.’ Others referenced paddling as inseparable from Hawai‘i itself: ‘It’s part of Hawai‘i.’ In these ways, paddling serves as a cultural keystone, helping to preserve and pass on tradition in contemporary Hawaiian life.

Level 6: spiritual factors (transcend levels 1–5) (27 responses)

Some paddlers described the meaning of paddling in ways that transcended individual, social, environmental, and cultural dimensions, expressing a deep, spiritual connection. Statements such as ‘[Paddling means] everything,’ and ‘Canoe paddling was life, it made me feel free,’ reflected meanings that reached beyond the physical or social to something greater and more sacred. Survey responses that fell into this category referenced Hawaiian values such as ‘mana,’ ‘manaʻo,’ and ‘lōkahi.’ In Hawaiian, ‘mana’ can be translated as ‘divine power,’ ‘manaʻo’ as “thought,” and ‘lōkahi’ as “unity” (Ulukau n.d.). However, these terms hold layered meanings. The Hawaiian language and worldview are expansive, and a single word can encompass multiple interconnected concepts (A. Yoshida personal communication 2024). For example, ‘lōkahi’ can also be interpreted as “unison,” “agreement,” and “peace” (A. Yoshida personal communication 2024) and “balance” (Paglinawan and Paglinawan 2012, Yamasaki 2024). For more expansive definitions of these and other Hawaiian concepts, readers may refer to Ulukau: The Hawaiian Electronic Library (Ulukau n.d.).

For some respondents, this transcendent aspect was described specifically as a spiritual experience: ‘Cleansing one’s spirit,’ ‘Physical health, emotional balance, spiritual connection with ocean and self….’ Some responses described transcendence as a shared experience that creates something greater than the sum of its parts, reflecting the concept of lōkahi: ‘To me, outrigger canoe paddling means community, teamwork, and culture combined to achieve one common shared goal. When done successfully, it is an undeniable artform to both the participants and any observers.’

“Manaʻo” emerged as a notable theme. One participant described paddling as channel for ideas and life lessons: ‘Paddling was always the vehicle to help us grow and better ourselves in life. The concepts that we learned in practices and races that what we learned and the manaʻo that was shared is to be used in ALL aspects of life not just in paddling.’ Participants shared different lessons learned from outrigger canoe paddling: ‘It taught me how to become one with your crew. Without one, there is none.’ Another participant expands on this idea: ‘…working together as one body and soul with other people teaches you how to respect others differences.’

Multiple social–ecological model levels

More than half (60%) of the responses (212 out of 353) were coded across multiple levels of the SEM. Specifically, 96 responses spanned two levels, 89 three levels, 24 four levels, and 3 across five levels. No responses were coded across all six levels. Figure 2c displays the 212 multi-level responses.

‘Among two-level combinations (n = 96),’ the most common pairing was between level 1 (interpersonal) and level 3 (distal connections), with 38 responses. One participant shared, ‘It means teamwork and trying to stay physically fit as well as enjoyment.’ The next most frequent combination was level 1 (individual) and level 5 (macrosocial), appearing in 21 responses. One respondent explained, ‘It connects me with my Hawaiian heritage. My ancestors were voyagers, fisherman, people of the sea. It helps me feel more connected with my culture.’ Other two-level combinations also emerged, such as level 1 and level 2 (proximal connections): ‘It's very fun to paddle especially with my friends.’

‘Three-level combinations’ were also observed (n = 89). The most common combination included level 1 (intrapersonal factors), level 3 (distal connections), and level 4 (environmental factors), appearing in 37 responses. For example: ‘… It means being connected to kai (sea) (Ulukau n.d.),’ exercising and breathing in clean air, cleansing in the kai’ or ‘It makes me feel like I belong to the ʻāina (land/earth) (Ulukau n.d., A. Yoshida personal communication 2024).’ These examples illustrate how paddlers experience a personal connection to the natural environment through the act of paddling. Other frequently observed three-level combinations were intrapersonal factors (1), proximal factors (2), and distal connections (3) with 16 responses and intrapersonal factors (1), distal connections (3), and macrosocial factors (5) with 12 responses.

Among the 24 responses coded across ‘four SEM levels,’ 11 included levels 1 through 4; two responses combined levels 1, 2, 3, and 5; and 13 responses had combinations with levels 5 and 6 (without level 2). Examples include: ‘…I get to paddle in the Pacific Ocean while meeting and greeting new friends,’ and ‘…Physical health, emotional balance, spiritual connection with ocean and self, building trust and communication with a team.’

Only three responses were coded across ‘five SEM levels.’ One example is: ‘How the islands came to be. The feel of the ocean and being one from the canoe.’ There were no ‘six-level combinations.’

THEMES

Two overarching themes emerged based on the frequency of certain key words and the coding across multiple SEM levels: (i) connection to self and others, canoe, and nature and (ii) improved quality of life through lesson learned and community belongings.

Overarching theme 1

This theme captures the personal benefits and motivations that arise from ‘connections—to self, to others (family, friends, team), to the canoe, and to nature, including ancestors.’ This is also reflected in the quantitative data in Table 1, which shows that nearly 50% of paddlers paddle with friends (n = 176) and/or a club (n = 164), and nearly 40% with family (n = 139).

Within this theme, paddling fosters connection with oneself and with people across time—present, past, and future. Participants shared statements such as ‘I love paddling and it’s both important as a physical event and as a social event,’ ‘It meant a lot to me because I connected with other,’ and ‘It taught me how to become one with our crew.’ ‘It means bonding and strengthening it with the lāhui (people)’ (Ulukau n.d.). ‘Working as a team on the water.’ ‘It's a way to connect to my ancestors.’

Paddling also fosters a connection to nature, embodied by the vessel itself, traditionally made from highly valued Koa wood. These elements are often personified and connected to spiritual dimensions, with the canoe and ocean described as ‘equal partners.’ Culture is another important facet of this theme. Forty-six paddlers referred to paddling as a cultural practice, emphasizing how it connects them to their heritage.

Overarching theme 2

Within theme 2, paddlers reported to have ‘improved their quality of life through the lessons learned from paddling.’ Paddlers reported that they appreciated the structures, guidance, and rules given in paddling as it gives them a feeling of safety and belonging to community. Others reported this trust is rooted in historical practices passed down from their ancestors. Respondents noted that paddling teaches discipline and respect, which participants reported applying to other areas of their lives. This theme can be seen in the following quotes:

I've been involved with paddling at a young age. Paddling was always the vehicle to help us grow and better ourselves in life. The concepts that we learned in practices and races that what we learned and the mana‘o that was shared is to be used in ALL aspects of life not just in paddling.

It means learning how to mālama (tend to, care for, preserve, protect, save, maintain) (Ulukau n.d.) our ocean and how to use it to make us strong, nourished and united as one. It means discovery of ourselves and how respect unites people and gives us the strength to overcome the biggest waves that life sends us.

DISCUSSION

Respondents in the state of Hawai‘i reported multifaceted meanings for paddling across multiple levels of the SEM. Over half of respondents specifically described paddling through multiple SEM layers in their open-ended responses. Research has shown that addressing multiple layers of the SEM model is important for effective health promotion (Richard et al. 1996, Ioannou et al. 2023). Hence, paddling aligns well with best-practice recommendations and may be a promising intervention to increase PA engagement. This is in alignment with previous work on this topic in other locations, which also highlighted the complex, multifaceted health value of paddling practices in the Pacific especially in concordance with Indigenous health perspectives (Severinsen and Reweti 2021, Kanemasu 2024, 2025, Reweti and Severinsen 2022) and in other settings (Mikraszewicz and Richmond 2019).

As hypothesized, many responses revealed areas highly relevant to health and well-being. For paddlers, connection extends beyond teammates and peers, to include family, culture, and ancestors. Paddling nurtures a connection to ‘ohana (family) (Ulukau n.d.), not only immediate or biological family, but also chosen family and community, linking past, present, and future. Respondents described how paddling helped them meet new people, form friendships, and build a sense of belonging, all of which contribute to a broader experience of ‘ohana.

Positive paddling experiences included having fun, enjoyment, relaxation, and physical fitness. Importantly, these benefits were not static but described as evolving processes. Paddlers often described meeting and bonding with new people, experiencing joy and peace, improving mental health, and strengthening physical fitness. Beyond individual benefits, paddling fostered a sense of belonging through relationships to others and nature. These interconnected relationships deepened paddlers’ appreciation for the activity and motivated continued participation throughout their lifetime.

While responses spanned all SEM levels, the most frequently coded theme was at the intrapersonal level (level 1). Within this level, paddlers referred to a variety of physical, emotional, and psychological benefit. Some responses were categorized singularly, while others were coded in combination with other SEM levels.

Sustaining PA can be through different levels of engagement, from recreational to competitive paddling. Outrigger canoe paddling serves many purposes, including voyaging and fishing. From a public health perspective, these all may be important and allow participation across ages and fitness levels. Notably, 40% of survey participants reported paddling with family outside of a formal club. Others associated paddling with competition. For example, one participant described it as ‘officially paddling with a canoe club in a competitive sport,’ while another highlighted its role as a ‘team sport, practice, competition.’ Although competition adds intensity, it may deter those who value other aspects of paddling more.

This study adapted the traditional SEM by adding a spiritual level, as many responses expressed spiritual meanings for paddling. This aligns with other research emphasizing spirituality as integral to health and well-being in Indigenous cultures worldwide (Keene 2024, Prevent Connect 2025). Indigenous health frameworks across Oceania and globally incorporate spirituality and transcendent connections, including the Te Whare Tapa Whā model (Māori, Aotearoa New Zealand) (Rochford 2004, Te Pūkenga 2025), the Fonofale model (Pasifika) (Ioane and Tudor 2017), and the Diné Hózhó resilience model (Kahn-John Diné and Koithan 2015). Our results highlight Indigenous health perspectives and our findings can be considered in light of the importance of Indigenous health frameworks, which are too often underrepresented and undervalued in planning, policy, and practice (Allender et al. 2006, Campbell et al. 2021).

The ocean has always played an important role in NH culture for physical and spiritual sustenance (NOAA 2022). Personal relationships with natural elements are also important to NH and PI cultures. Integrating the cultural values of the ocean is essential for ocean-sports health promotion (Huffer 2017). This has been better researched for surfing (Clapham et al. 2014, Amrhein et al. 2021), but is also true in ocean paddling and other practices (Schmid et al. 2024c).

The results may be interpreted through the lens of the Lōkahi-Triangle, a framework that emphasizes lōkahi (balance) among three interconnected elements: (i) Akua and Nā ‘Aumakua (spiritual realm), (ii) Kānaka (humankind), and (iii) ‘Āina, Moana, Lani (land, ocean, sky) to achieve Lōkahi (unity, harmony, balance) (Paglinawan and Paglinawan 2012). Lōkahi is deeply rooted in the Hawaiian culture, and several respondents disclosed how paddling helped them maintain or restore this balance, including: (i) it supported personal well-being—physical, mental, and spiritual—through connection to place and heritage and for others (ii) it reflected their role within a broader community that includes not only people, but also the land and spiritual forces with lōkahi at the center (rather than humans). These participant responses align with themes found in the Lōkahi Wheel framework, which conceptualizes well-being as interconnected sectors of a wheel centered around lōkahi (Martin and Godinet 2018). This model resonates with traditional NH conceptions of the psyche (McCubbin and Marsella 2009).

The study highlights the strength-based approach of how paddlers enjoy this activity and connect to their heritage and culture, offering intrinsic motivation for PA (Meyer 2010, Peattie et al. 2023). The study emphasizes how paddlers’ enjoyment and cultural connection provide intrinsic motivation for PA, reinforcing adherence (Wankel 1993). Research shows that linking exercise to cultural identity, rather than just health benefits such as improving diabetes, enhances participation in other Indigenous populations (Warbrick et al. 2020). This aligns with evidence that meaningful activities foster motivation, which is essential for sustaining PA (Teixeira et al. 2012).

The results have been reported back to community members and community organizations, at community events, including paddling events, and with the study partner, the Hawai‘i Department of Health. The results have also been shared with the scientific community at local, national, and international conferences.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

Research on ocean-based sports such as paddling is important. Recent research suggests that bluepaces may be even more beneficial to health than greenspaces (Liu 2021). Fortunately, in Hawai‘i, legal protections ensure access to beaches and the ocean, supporting participation in such activities (Hawaii State Capitol 1986). Study results can inform strengths-based health promotion interventions related to culturally based PA. Revitalizing paddling in its diverse forms, such as voyaging, canoe fishing, and recreational paddling, beyond competition can capture the full potential of paddling for the people of Hawai‘i. This approach could foster broader public health benefits by leveraging paddling as a tool for chronic disease prevention for many populations at risk.

Our study emphasized the importance of spirituality along with other layers of the SEM. This extended SEM model may be particularly useful when exploring the meaning of culturally relevant PA more broadly. Accounting for spirituality is critical in designing effective health promotion interventions.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Paddling represents a strong example of a multi-level PA intervention that is culturally relevant and potentially scalable, especially among populations with existing cultural ties to the practice. Based on the findings, we recommend expanding and exploring paddling as a health promotion activity by leveraging existing structures such as clubs and community groups. Interventions should follow best practices by addressing multiple SEM layers.

Additionally, quantitative studies on the health benefits of paddling would be valuable. One important area is determining the metabolic equivalent of task (MET) value for outrigger canoe paddling, which measures the intensity and energy expenditure of activities. While MET values exist for more than 1200 activities (Herrmann et al. 2024), outrigger canoe paddling has not yet been determined. Establishing this value could help contextualize paddling’s benefits compared to other recreational and competitive physical activities. Efforts to establish the MET value are currently underway (Schmid et al. 2024a, 2024b).

LIMITATIONS

This study has many strengths and some limitations. This sample consisted of individuals who identified as paddlers, which may introduce social desirability and recall biases (Althubaiti 2016). This analysis is based on a single open-ended question, with the interpretation of ‘meaning’ being broad, which may limit the depth and specificity of findings.

CONCLUSION

Due to the strong evidence on the health benefits of hula (Look et al. 2012, Kaholokula et al. 2014, 2017, 2021) and the growing evidence on paddling (Canyon and Sealey 2016, Mikraszewicz and Richmond 2019, Liu 2021, Severinsen and Reweti 2021, Kanemasu 2024, 2025), health promotion efforts should consider encouraging and reducing barriers to participation in outrigger canoe paddling to support health from a strengths-based and community, culturally relevant perspective (Sentell et al. 2023). Community members’ perspectives were vital to understanding the meaning of paddling. Paddlers reported that its meaning reaches across the SEM and hence aligns with best-practice guidelines developed for PA interventions. Innovative partnerships and policies should be developed to address uptake of culturally relevant PA for people with health disparities. This study confirmed the importance of an extended SEM including spirituality, which could be useful for other research on culturally relevant physical activities.

Implications for policy or practice

Innovative partnerships or policies should be developed to address the uptake of culturally relevant PA for people with health disparities. A next step is to look at barriers for uptake, including the cost and potential of covering paddling club membership through health insurance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all paddler participants and SMS Research & Marketing Services for the data collection of this survey. S.M.S. is deeply grateful to all her past and current paddling coaches and mentors for their wisdom, patience and knowledge. Their guidance and encouragement made this work possible.

Contributor Information

Simone M Schmid, Department of Public Health Science (DPHS), University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1960 East-West Road, Biomed D-104 W, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA; Hawaiʻi State Department of Health, Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division, 1250 Punchbowl Street, Honolulu, HI 96813, USA; AccesSurf Hawaiʻi, Grants and Evaluations, P.O. Box 15152, Honolulu, HI 96830, USA.

Carrie Soo Hoo, Department of Public Health Science (DPHS), University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1960 East-West Road, Biomed D-104 W, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA.

Catherine M Pirkle, Department of Public Health Science (DPHS), University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1960 East-West Road, Biomed D-104 W, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA.

Michael M Phillips, Department of Public Health Science (DPHS), University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1960 East-West Road, Biomed D-104 W, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA.

Mika Thompson, Department of Public Health Science (DPHS), University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1960 East-West Road, Biomed D-104 W, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA.

Ann Yoshida, AccesSurf Hawaiʻi, Grants and Evaluations, P.O. Box 15152, Honolulu, HI 96830, USA.

Heidi Hansen Smith, Hawaiʻi State Department of Health, Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division, 1250 Punchbowl Street, Honolulu, HI 96813, USA.

Lance Ching, Hawaiʻi State Department of Health, Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division, 1250 Punchbowl Street, Honolulu, HI 96813, USA.

Julia Finn, Department of Public Health Science (DPHS), University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1960 East-West Road, Biomed D-104 W, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA.

Tetine Sentell, Department of Public Health Science (DPHS), University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1960 East-West Road, Biomed D-104 W, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA.

Author contributions

S.M.S. led the analysis of the qualitative data, identified the SEM to use as coding structure, developed the extended SEM, led the visualization of the data, and wrote the manuscript. C.S.H. contributed to data analysis and visualization, assisted with the qualitative analysis and interpretation of findings, contributed to the background and discussion sections, provided feedback on the manuscript, and reviewed the final draft. C.M.P. conceived the study and funding, developed the research design provided feedback on the manuscript, and reviewed the final draft. M.M.P. conceived the study and funding, developed the research design, and supervised the quantitative analysis. M.T. led the quantitative analysis. A.Y. supported and reviewed the translation and interpretation of the Hawaiian words, provided feedback to the manuscript, and reviewed the final draft. H.H.S. provided feedback to the manuscript and reviewed the final draft. L.C. conceived the study and funding and developed the research design. J.F. was the second coder for the qualitative analysis and started the visualization of the data. T.S. conceived the study and funding, developed the research design, supervised the research process, provided critical revisions, and ensured adherence to ethical standards.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at Health Promotion International online.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the research, authorship, and publication of this article. This includes financial, personal, or professional interests that could be perceived to influence the results or interpretation of the study.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Hawai‘i Department of Health, Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division.

Data availability

Data can be available upon request.

References

- Agner J, Pirkle CM, Irvin L et al. The healthy Hawai‘i initiative: insights from two decades of building a culture of health in a multicultural state. BMC Public Health 2020;20:141. 10.1186/s12889-019-8078-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allender S, Cowburn G, Foster C. Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: a review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res 2006;21:826–35. 10.1093/her/cyl063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016;9:211–7. 10.2147/JMDH.S104807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein M, Barkhoff H, Heiby EM. The effects of an ocean surfing course intervention on spirituality and depression. Sport J 2021;27. https://thesportjournal.org/article/the-effects-of-an-ocean-surfing-course-intervention-on-spirituality-and-depression/ [Google Scholar]

- An R, Xiang X, Yang Y et al. Mapping the prevalence of physical inactivity in U.S. States, 1984–2015. PLoS One 2016;11:e0168175. 10.1371/journal.pone.0168175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Kivimaki M et al. Walking pace, leisure time physical activity, and resting heart rate in relation to disease-specific mortality in London: 40 years follow-up of the original Whitehall study. An update of our work with professor Jerry N. Morris (1910–2009). Ann Epidemiol 2010;20:661–9. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black TL, Raine K, Willows ND. Understanding prenatal weight gain in first nations women. Can J Diabetes 2008;32:198–205. 10.1016/S1499-2671(08)23010-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychologist 1977;32:513–31. 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RD, Dennis MK, Lopez K et al. Qualitative research in communities of color: challenges, strategies, and lessons. J Soc Social Work Res 2021;12:177–200. 10.1086/713408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canyon DV, Sealey R. A systematic review of research on outrigger canoe paddling and racing. Ann Sports Med Res 2016;3:1076. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/44691/1/sportsmedicine-3-1076.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Physical activity among Asians and native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islanders—50 states and the District of Columbia, 2001—2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:756–60. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5333a2.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D, Armitano N, Lamont S et al. The ocean as a unique therapeutic environment: developing a surfing program. J Phys Educ Recreat Dance 2014;85:8–14. 10.1080/07303084.2014.884424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conn VS, Chan K, Banks J et al. Cultural relevance of physical activity intervention research with underrepresented populations. Int Q Community Health Educ 2013;34:391–414. 10.2190/IQ.34.4.g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng P, Fu Y, Chen M et al. Temporal trends in inequalities of the burden of cardiovascular disease across 186 countries and territories. Int J Equity Health 2023;22:164. 10.1186/s12939-023-01988-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawaii State Capitol . Session Laws of Hawaii Passed by the Thirteenth State Legislature, Act 219, H.B. 2173-86, [§5] State Team Sport, p. 385, 1986. https://data.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessions/sessionlaws/AllIndex/All_Acts_SLH1986.pdf (15 August 2025, date last accessed).

- Heil DP, Angosta AD, Zhu W et al. The energy expenditure of tinikling: a culturally relevant Filipino dance. Int J Exerc Sci 2019;12:111–21. 10.70252/FJUG5462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann SD, Willis EA, Ainsworth BE et al. 2024 adult compendium of physical activities: a third update of the energy costs of human activities. J Sport Health Sci 2024;13:6–12. 10.1016/j.jshs.2023.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffer E. Raising and Integrating the Cultural Values of the Ocean, 2017. https://www.iucn.org/news/commission-environmental-economic-and-social-policy/201710/raising-and-integrating-cultural-values-ocean (15 August 2025, date last accessed).

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation . Global Burden of Disease 2021, 2024. https://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/GBD_2021_Booklet_FINAL_2024.05.16.pdf (15 August 2025, data last accessed).

- Ioane J, Tudor K. The fa’asamoa, person-centered theory and cross-cultural practice. Pers-Centered Exp Psychother 2017;16:287–302. 10.1080/14779757.2017.1361467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou E, Humphreys H, Homer C et al. O.3.3–7 A socio-ecological approach to overcoming barriers for physical activity promotion after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Eur J Public Health 2023;33:ckad133.162. 10.1093/eurpub/ckad133.162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn-John Diné M, Koithan M. Living in health, harmony, and beauty: the Diné (Navajo) Hózhó wellness philosophy. Glob Adv Health Med 2015;4:24–30. 10.7453/gahmj.2015.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaholokula JK, Ing CT, Look MA et al. Culturally responsive approaches to health promotion for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Ann Hum Biol 2018;45:249–63. 10.1080/03014460.2018.1465593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaholokula JK, Look M, Mabellos T et al. A cultural dance program improves hypertension control and cardiovascular disease risk in Native Hawaiians: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 2021;55:1006–18. 10.1093/abm/kaaa127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaholokula JK, Look MA, Wills TA et al. Kā-HOLO project: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial of a native cultural dance program for cardiovascular disease prevention in Native Hawaiians. BMC Public Health 2017;17:321. 10.1186/s12889-017-4246-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaholokula JK, Nacapoy AH, Dang K. Social justice as a public health imperative for Kānaka Maoli. AlterNative: Int J Indig Peoples 2009;5:116–37. 10.1177/117718010900500207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaholokula JK, Yoshimura S, Palakiko D-M et al. The PILI ‘Ohana Project: a community-academic partnership to achieve metabolic health equity in Hawai‘i. Public Health. 2014;73:29–33. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4271354/pdf/hjmph7312_S3_0029.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai Ikaika . Outrigger Basics. Portland, Oregon: Kai Ikaika Paddling Club, n.d.. https://www.kaiikaika.com/outrigger-basics/ (14 November 2024, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- Kanemasu Y. Paddling our sea of islands: Fiji outrigger canoe racing (va‘a) as living culture. In: Towards a Pacific Island Sociology of Sport. Vol. 22. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2024, 79–98. 10.1108/S1476-285420240000022005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemasu Y. Paddling as ‘pelagic postcolonialism’: Pacific voyaging resurgence, ocean justice and outrigger canoe racing (va‘a) in Fiji. Int Rev Sociol Sport 2025;60:675–95. 10.1177/10126902241282069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keene C. What is Faith-based Prevention and Why Does Spirituality Matter in Our Work to Prevent Gender-based Violence? VAWnet.Org, 2024. https://vawnet.org/news/what-faith-based-prevention-and-why-does-spirituality-matter-our-work-prevent-gender-based (15 August 2025, date last accessed).

- Liu L. Paddling through bluespaces: understanding waka ama as a post-sport through indigenous Māori perspectives. J Sport Soc Issues 2021;45:138–60. 10.1177/0193723520928596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Look MA, Kaholokula JK, Carvahlo A et al. Developing a culturally based cardiac rehabilitation program: the HELA study. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2012;6:103–10. 10.1353/cpr.2012.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Look MA, Maskarinec GG, de Silva M et al. Kumu hula perspectives on health. Hawai‘i J Med Public Health. 2014;73:21–5. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4271348/pdf/hjmph7312_S3_0021.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Look MA, Maskarinec GG, de Silva M et al. Developing culturally-responsive health promotion: insights from cultural experts. Health Promot Int 2023;38:daad022. 10.1093/heapro/daad022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TK, Godinet M. Using the lōkahi wheel: a culturally sensitive approach to engage native Hawaiians in child welfare services. J Indig Soc Dev 2018;7:22–40. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/jisd/article/view/58482 [Google Scholar]

- Maskarinec GG, Look M, Tolentino K et al. Patient perspectives on the hula empowering lifestyle adaptation study: benefits of dancing hula for cardiac rehabilitation. Health Promot Pract 2015;16:109–14. 10.1177/1524839914527451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mau MK, Sinclair K, Saito EP et al. Cardiometabolic health disparities in Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Epidemiol Rev 2009;31:113–29. 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin LD, Marsella A. Native Hawaiians and psychology: the cultural and historical context of indigenous ways of knowing. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2009;15:374–87. 10.1037/a0016774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MA. Hoʻoulu: Our Time of Becoming: Hawaiian Epistemology and Early Writings. Vol. 1. Honolulu, HI: Ulukau Books, 2010. https://ulukau.org/ulukau-books/? a=d&d=EBOOK-HOOULU.2.1.1&e=-haw-20–1–txt-txPT [Google Scholar]

- Mikraszewicz K, Richmond C. Paddling the Biigtig: Mino biimadisiwin practiced through canoeing. Soc Sci Med 2019;240:112548. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A, Abbott R, Macdonald D. Indigenous Australians and physical activity: using a social–ecological model to review the literature. Health Educ Res 2010;25:498–509. 10.1093/her/cyq025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niakouei A, Tehrani M, Fulton L. Health disparities and cardiovascular disease. Healthcare 2020;8:65. 10.3390/healthcare8010065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOAA . Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument: Native Hawaiian Cultural Heritage, 2022. https://www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/heritage/ (15 August 2025, date last accessed).

- Olson J, McAllister C, Grinnell L et al. Applying constant comparative method with multiple investigators and inter-coder reliability. Qual Rep 2016;21:26–42. 10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paglinawan RK, Paglinawan LKK. Living Hawaiian rituals: lua, ho‘oponopono, and social work. Hūlili: Multidiscipl Res Hawaiian Well-Being. 2012;8:1–18. https://kamehamehapublishing.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2020/09/Hulili_Vol8_2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Peattie P, Padilla C, Villablanca M. Kailua canoe club: a values-based holistic approach to leadership. J Values-Based Leadership. 2023;16:1–23. 10.22543/1948-0733.1432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prevent Connect . Socio-ecological Model, 2025. http://wiki.preventconnect.org/socio-ecological-model/ (15 August 2025, date last accessed).

- Reweti A, Severinsen C. Waka ama: an exemplar of indigenous health promotion in Aotearoa New Zealand. Health Promot J Austr 2022;33:246–54. 10.1002/hpja.632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard L, Potvin L, Kishchuk N et al. Assessment of the integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot 1996;10:318–28. 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards KAR, Hemphill MA. A practical guide to collaborative qualitative data analysis. J Teach Phys Educ 2018;37:225–31. 10.1123/jtpe.2017-0084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rio CJ, Saligan LN. Understanding physical activity from a cultural-contextual lens. Front Public Health 2023;11:1223919. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1223919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DB, Barrett J, Robinson I. Culturally relevant physical education: educative conversations with Mi’kmaw elders and community leaders. In Education 2016;22:2–21. 10.37119/ojs2016.v22i1.260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rochford T. Whare Tapa Wha: a Mäori model of a unified theory of health. J Prim Prev 2004;25:41–57. 10.1023/B:JOPP.0000039938.39574.9e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos AC, Willumsen J, Meheus F et al. The cost of inaction on physical inactivity to healthcare systems. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;11:e32–e39. 10.2139/ssrn.4248284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid SM, Heil DP, Ching L et al. AccessMETs: an innovative project establishing metabolic equivalents of outrigger canoe paddling for health equity in real-life ocean conditions for those with and without spinal cord injuries. In: American Public Health Association Annual Conference, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, 29 October 2024a.

- Schmid SM, Heil DP, Yoshida A et al. Metabolic equivalents of outrigger canoe paddling for health equity: methods of an inclusive AccessMETs study. Rev Disability Stud. 2024b. https://rdsjournal.org/index.php/journal/article/view/1346 [Google Scholar]

- Schmid SM, Soo Hoo C, Thompson M et al. Culturally-relevant physical activities for the people of Hawai‘i in comparison across levels of the social ecological model: Hula, paddling, surfing, and spearfishing. In: American Public Health Association Annual Conference, Minneapolis, 29 October 2024c.

- Sentell T, Wu YY, Look M et al. Culturally relevant physical activity in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system in Hawai‘i. Prev Chronic Dis 2023;20:E43. 10.5888/pcd20.220412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinsen C, Reweti A. Waiora: connecting people, well-being, and environment through waka ama in Aotearoa New Zealand. Health Promot Pract. 2021;22:524–30. 10.1177/1524839920978156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solla P, Cugusi L, Bertoli M et al. Sardinian folk dance for individuals with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Altern Complement Med 2019;25:305–16. 10.1089/acm.2018.0413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spickard P, Rondilla JL, Wright DH. Pacific Diaspora: Island Peoples in the United States and Across the Pacific. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Markland D et al. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:78. 10.1186/1479-5868-9-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Te Pūkenga . New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology. Te Whare Tapa Whā, 2025. https://www.xn--tepkenga-szb.ac.nz/te-pae-ora/living-well-learning-well/te-whare-tapa-wha (13 June 2024, date last accessed).

- Ulukau . Nā Puke Wehewehe ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi. The Hawaiian Electronic Library, n.d.. https://wehewehe.org/ (23 August 2024, date last accessed).

- Usagawa T, Look M, de Silva M et al. Metabolic equivalent determination in the cultural dance of hula. Int J Sports Med 2013;35:399–402. 10.1055/s-0033-1353213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wankel LM. The importance of enjoyment to adherence and psychological benefits from physical activity. Int J Sport Psychol 1993;24:151–69. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-07751-001 [Google Scholar]

- Warbrick I, Wilson D, Griffith D. Becoming active: more to exercise than weight loss for indigenous men. Ethn Health 2020;25:796–811. 10.1080/13557858.2018.1456652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Physical Activity—Key Facts—What is Physical Activity?, 2023. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/ (15 August 2025, date last accessed).

- WHO . Physical Activity, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/physical-activity (15 August 2025, date last accessed).

- Willows ND, Hanley AJG, Delormier T. A socioecological framework to understand weight-related issues in aboriginal children in Canada. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012;37:1–13. 10.1139/h11-128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki L . Lani Kamauu Yamasaki, Live Lōkahi, 2024. https://laniyamasaki.com/ (14 April 2025, date last accessed).

- Yoshida A. Translation of Hawaiian Words in Context of Study by Native Hawaiian Speaker [Personal communication], 2024.

- Zhu W, Lankford DE, Reece JD et al. Characterizing the aerobic and anaerobic energy costs of Polynesian dances. Int J Exerc Sci 2018;11:1156–72. 10.70252/IRUF2750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data can be available upon request.