Abstract

There is a consensus in the literature that the integrated leadership approach, which includes different leadership styles, has an impact on teachers’ emotions as well as their behaviors. The aim of this study is to examine the moderator role of distributed leadership in the effect of servant leadership on teachers’ teaching enthusiasm through their subjective well-being in Turkish schools. In this cross-sectional study, a moderated mediation model was tested with a quantitative approach. The analyses were conducted with data collected from 827 teachers from 81 provinces of Türkiye. The study results revealed that there was no significant direct relationship between servant leadership and teaching enthusiasm; however, there was a significant and positive relationship between servant leadership and teacher subjective well-being and between teacher subjective well-being and teaching enthusiasm. Additionally, the study found that when distributed leadership was high, the relationship between servant leadership and teacher subjective well-being and the indirect effect of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm through teacher subjective well-being were strengthened. In other words, the study concluded that school principals who exhibit both servant and distributed leadership can increase teachers’ teaching enthusiasm by improving teachers’ subjective wellbeing.

Keywords: Servant leadership, Distributed leadership, Teacher subjective well-being, Teaching enthusiasm, Integrated leadership, Moderated mediation effect

Subject terms: Psychology, Environmental social sciences

Introduction

Educators and policymakers are trying to identify the key factors influencing student outcomes1. These efforts show that teachers’ positive feelings toward teaching affect student performance and motivation2. Schools are physically and emotionally challenging places3, and in such environments, warmth and enthusiasm are essential qualities for teachers to adapt to new situations and cope with setbacks4. Teaching enthusiasm (TE), an affective factor, is considered important in influencing student learning and academic outcomes5. A lack of enthusiasm in a teacher is associated with burnout6. This issue is particularly concerning in Turkish schools that have a centralized education system, collectivist cultural norms, and limited teacher autonomy7. Teachers unable to take proactive roles may view their profession as unimportant, and as a result, their performance declines8. Existing literature focuses on the effects of TE on teaching quality and student outcomes, but studies on the factors shaping TE are quite limited9,10. In this context, identifying effective strategies to cultivate and maintain teachers’ enthusiasm for teaching is essential for ensuring the long-term effectiveness and resilience of educational systems. Accordingly, closing this research gap may offer substantial contributions to both the theoretical understanding and the practical advancement of educational leadership and teacher development.

Although the role of school leadership in the effectiveness of teachers in the teaching and learning process is known11, there is a knowledge gap regarding the interaction between school leadership and TE. Only a limited number of studies have examined the impact of school leadership on teacher enthusiasm via specific leadership styles such as instructional9 and distributed12 leadership. Although there are studies examining the impact of servant leadership on teacher passion and behaviors that positively influence student learning13, no study has yet examined the relationship between servant leadership (SL) and TE. The lack of studies on SL and TE may stem from hierarchical school structures in which teachers especially need emotional support and inspirational leadership to adapt to changes. SL is defined as a philosophy motivated by serving others, prioritizing followers’ needs over the leader’s own. In schools, SL typically involves principals guiding and supporting teachers’ development14. The characteristics of SL, such as empathy, helpfulness, being a good listener, and foresight15,16, manifest themselves in positive outcomes such as higher job satisfaction and organizational commitment among teachers17. Consequently, principals’ implementation of SL practices may contribute to the improvement of teachers’ subjective well-being (TSW), which encompasses teachers’ overall happiness, job satisfaction, and psychological well-being related to both work and life18. High TSW likely leads teachers to take a more positive approach in the classroom and to display greater enthusiasm and energy in front of their students. This suggests that school leadership may exert an indirect effect on teacher enthusiasm. The literature review shows that teacher subjective well-being (TSW) is positively correlated with both TE19 and SL20. However, the mediating role of TSW in the relationship between SL and TE remains unclear.

SL behaviors support, empower, and prioritize employee development14. When combined with DL behaviors that emphasize shared leadership and teacher participation, they may have a stronger impact on teacher motivation. Theoretically, DL can enhance teacher motivation by granting greater autonomy and actively involving them in decision-making processes. SL addresses teachers’ personal and emotional needs through empathy, support, and ethical guidance21, whereas DL promotes a supportive organizational climate through shared leadership and collaborative teamwork. This dual approach can simultaneously enhance individual well-being and foster a collective, empowering school environment. The combination of these leadership styles can provide optimal conditions for promoting teacher well-being and maintaining their enthusiasm. In Türkiye’s hierarchical and high power distance culture, DL can help overcome rigid structures by promoting collective participation and reducing organizational hierarchies. Therefore, the rationale for this combination is both theoretical and contextual.

A study conducted in Turkey22 found that school principals’ distributed leadership (DL) behaviors promoted teachers’ autonomy, innovative capacity, and professional collaboration. Another study23 similarly indicated that such leadership practices enhanced teachers’ job satisfaction and self-efficacy. Based on these recent findings showing that DL can indirectly contribute to teachers’ well-being, it is thought that the DL environment can strengthen the effects of school principals’ SL practices on teachers. While the relationship between SL and TSW has been examined in various contexts in previous studies20, how this relationship may change when moderated by other leadership approaches such as DL remains unclear.

SL and DL can be considered two important theoretical frameworks that can shape teachers’ emotional and professional experiences. A teacher whose well-being increases can be expected to be enthusiastic in the teaching process19. Because servant leadership can enhance teachers’ well-being, and distributed leadership creates supportive conditions, the impact of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm through teacher well-being may vary depending on with the level of distributed leadership exhibited by the principal. In the only accessible study examining the relationship between principal leadership and teaching enthusiasm through a moderator variable7, discovered that power distance had a negative moderator effect between instructional leadership and teacher enthusiasm. Distributed leadership (DL) is a model in which leadership responsibilities are spread across the school team, moving away from hierarchical practices. This collaborative approach encourages teamwork and high levels of teacher involvement, which in turn motivates and mobilizes teachers24. In Turkish culture, where power distance is high25, teachers can expect support from their principals, participation in decision-making processes, and sharing of leadership roles. Increasing Turkish teachers’ TSW and TE may depend on school principals exhibiting both servant and distributed leadership behaviors.

Overall, the effects of SL and DL on teachers’ emotional states and outcomes have been examined separately13,20,26–28. stated that using various leadership approaches simultaneously rather than a single approach in principal leadership produced more effective results for students, teachers, and schools. Therefore, a study that integrates SL and DL and examines their effects on TE may reveal a stronger relationship and a more comprehensive result. In contrast to the predominant focus on single leadership models in management and leadership studies29, examining SL and DL through an integrated lens may provide valuable contributions to the literature. Although studies have examined various pairs of these four conceptually related variables13,19,20, no research to date has revealed the connections among all four constructs in a single study. Investigating the factors that contribute to TE is not only critical for teachers and students; it can also have positive impacts on the education system as a whole. Research results can provide resources for developing support systems and policies for teachers and school principals. In schools where DL is strongly practiced, teachers are more engaged in decision-making processes and have greater trust in school management; therefore, the influence of the principal’s SL behaviors may become more evident. In contrast, in contexts where leadership is not shared, even well-intentioned SL behaviors may fail to generate positive outcomes for teachers.

The issue of sustaining teachers’ enthusiasm has been widely debated across various educational systems worldwide27. This issue is particularly important in Turkey, where the Ministry of National Education (MEB) manages schools through a highly centralized structure. The country’s hierarchical education system, combined with cultural norms of high power distance, creates an environment where school principals are expected to implement top-down directives, while teachers typically have limited say in decision-making processes. These structural and cultural constraints can hinder teachers’ motivation and reduce their enthusiasm for teaching, especially when they feel unsupported or excluded from the process. Nevertheless, Turkey’s strong collectivist cultural orientation places significant value on interpersonal relationships and emotional support within professional environments. Within this cultural context, school principals play a vital role in the emotional and professional well-being of teachers30. Especially during and after the global pandemic, teachers have been at increased risk of losing motivation, making the supportive role of school leaders more important than ever. Recent studies indicate that teachers in Turkish schools place a strong emphasis on being valued, included in decision-making, and supported by their principals31,32. These expectations align with the core principles of SL, which emphasize support and recognition, and DL, which promotes participatory decision-making. The findings highlight why integrating SL and DL could have a significant impact on teachers’ well-being and enthusiasm in the centralized and power-distance-oriented Turkish school culture. Nonetheless, teachers tend to view school principals not only as authority figures but also as sources of trust, courage, and empathy. Recent policy reforms in Turkey reflect this shift in leadership understanding. For example, the transfer of performance evaluation responsibilities from inspectors to school principals in 201433 and the Ministry of National Education’s emphasis on teaching support provided under the leadership of school principals in the “Turkish Century Education Model”34 highlight the growing importance of principal-teacher relationships in improving school outcomes.

By testing a moderated mediation model, this study aims to reveal the joint effect of two theoretically complementary leadership styles (servant leadership and distributed leadership) on teaching enthusiasm, an important emotional outcome for educators. The study offers several novel contributions to the existing body of educational leadership literature. First, it is the first empirical study to simultaneously examine the relationships between servant leadership, distributed leadership, teachers’ subjective well-being, and teaching enthusiasm within a integrated theoretical model. Second, this study responds to recent calls in the educational leadership literature to move beyond single-style models and investigate the effects of blended leadership approaches. Third, this study was conducted in Turkey, a culturally and structurally distinct context that has been insufficiently researched, and provides insights into how leadership practices function in centralized and high-power-distance education systems. Finally, by conceptualizing teachers’ subjective well-being as a mediating psychological mechanism, the study advances an emerging line of inquiry linking leadership behaviors to teachers’ emotional and motivational outcomes. The research questions guiding the study are:

Does teacher subjective well-being have a mediating role in the relationship between servant leadership and teaching enthusiasm?

Does distributed leadership have a moderator effect on the relationship between servant leadership and subjective well-being?

Does distributed leadership moderate the indirect effect of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm through (teacher) subjective well-being?

Theoretical background

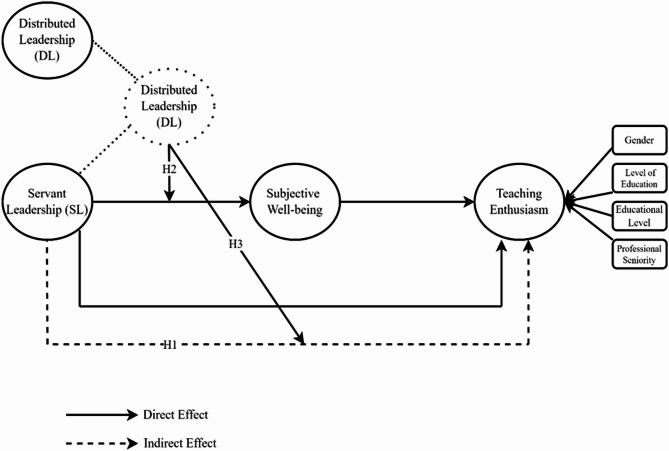

This study is theoretically grounded in the idea that supportive leadership behaviors shape teachers’ attitudes through positive psychological processes. This study draws on Social Exchange Theory35, which assumes a reciprocal relationship between organizations and employees, and Expectancy-Value Theory36, which suggests that expectations determine effort. When employees are supported, they perceive their managers’ behavior more positively and respond with positive and helpful actions37. In a school environment, supportive and empowering practices of servant and distributed principal leadership can promote teacher subjective well-being and enable them to respond positively with enthusiastic teaching activities. According to the expectancy-value theory based on achievement motivation, meeting teachers’ expectations of their principals can increase their enthusiasm for teaching. The proposed model integrates servant and distributed leadership perspectives to explore how principals influence teachers’ subjective well-being and, in turn, their teaching enthusiasm. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model developed and empirically tested in this study.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of study.

In this study, SL and DL models were examined in conjunction due to their theoretical complementarity and contextual relevance, particularly for education systems with centralized structures such as that of Turkey. Although Transformational Leadership (TL) is widely utilized in the educational leadership literature and shares certain features with SL—such as inspirational motivation and individualized consideration—it primarily emphasizes the leader’s vision22,38,39. In contrast, SL centers on addressing the individual needs and development of followers14,15. The integration of SL and DL provides both emotional resources (e.g., feeling valued) and structural resources (e.g., participation, shared leadership) that support TE. SL promotes trust and autonomy, fostering a school climate that facilitates the implementation of DL. Indeed23, demonstrated that when shared leadership is combined with servant leadership, it collectively empowers stakeholders. SL further supports collective participation by viewing followers as ends in themselves rather than as means to an end24. The combined application of these two leadership approaches offers a more effective and sustainable model, especially in contexts where teacher autonomy is constrained. As depicted in Fig. 1, the model posits that principals’ servant leadership behaviors indirectly enhance teachers’ enthusiasm by improving their subjective well-being (H1). Furthermore, the model proposes that distributed leadership moderates the relationship between servant leadership and teachers’ subjective well-being, thereby amplifying this association (H2). As a result, the indirect effect of servant leadership on teachers’ enthusiasm is also expected to be strengthened (H3).

Servant leadership

SL is an approach that embraces the idea of “service first”14. As the name suggests, SL is a “serving” leader and is characterized by qualities such as honesty, humility, excellent communication skills, and work ethic41. SL is a leadership approach that prioritizes the interests of followers over one’s own, considers the collective goals of the group, focuses on their development, and avoids self-promotion42. SL differs from traditional leadership approaches in that it emphasizes employees’ personal integrity, altruism, and ethical orientation14. In this study43, ’s single-dimensional servant leadership framework was adopted, which emphasizes serving as a role model, instilling trust, and providing information and resources.

Distributed leadership

First defined by44, DL refers to the integration of leadership into the function of the group and the sharing of leadership responsibilities by group members. DL is an approach that emphasizes leadership as an interactive and collective practice, rather than being centered on a single leader. In this context, the interaction of multiple actors is important45. DL emphasizes the sharing of leadership roles and tasks as well as the inclusion of more stakeholders in decision-making processes46. In this study27, ’s DL framework, which consists of two dimensions, namely leadership team cohesion and leadership functions, emphasizing the support role and teamwork, was used.

Teaching enthusiasm

Drawing on self-determination theory47, teacher enthusiasm is teachers’ transfer of their high energy and excitement to students through non-verbal expressions48. Teacher enthusiasm was conceptualized by4 in two sub-dimensions: field enthusiasm and teaching enthusiasm. Field enthusiasm is defined as teachers’ belief that their field of specialization is exciting, their passion for engaging with it, and their desire to share this enthusiasm with their students. The other dimension, TE, which is the concept we based our study on, refers to the degree to which teachers find teaching their students enjoyable and enjoy interacting with them49.

Subjective well-being

Subjective well-being refers to an individual’s overall evaluation of life satisfaction and the frequency of experiencing positive emotions18. In the positive psychology literature, SWB is considered the extent to which individuals feel happy, fulfilled, and emotionally balanced in both their personal and professional lives50. In educational settings, TSW should be conceptualized not only in terms of teachers professional commitment or perceived competence, but also through their experiences of happiness, purpose, satisfaction, and emotional stability within the school environment2. TSW, as a subfield of positive psychology, is defined as “an individual feeling of contentment, happiness, and job satisfaction built with students and colleagues in a collaborative process”2. In the present study, we adopt the framework proposed by51, which conceptualizes teachers’ well-being through two dimensions: school commitment and teaching efficacy. Here, school commitment refers to the sense of being supported by members of the school community and maintaining positive interpersonal relationships. The teaching-efficacy dimension reflects teachers’ sense of self-efficacy in teaching, an important indicator of their well-being.

The mediating role of subjective well-being between servant leadership and teaching enthusiasm

Empirical studies in the field of education show that school principals adopting the SL approach prioritize the well-being of teachers and provide them with guidance and assistance, thereby improving teachers’ ability to cope with challenges20,52. While meeting and supporting teachers’ needs positively affects teachers’ enthusiasm53, neglecting them can lead to burnout54. Teachers with high TSW are able to manage difficult emotional situations and achieve pedagogical goals for students2. On the other hand, low TSW results in problems such as classroom management difficulties and absenteeism51. Therefore, serving teachers by prioritizing their needs is of great importance to nurture their motivation and passion55. Teachers who have positive emotions such as cheerfulness, interest, and satisfaction tend to display high levels of energy and excitement26. Within this framework, as school principals’ SL levels increase, teachers’ well-being will also increase, and consequently, their enthusiasm for their work and passion for teaching will also increase. This assumption is supported by social change theory, which argues that when principals act in the interests of teachers, support them, and demonstrate care, teachers respond more positively. Notably, some prior studies have positioned teacher enthusiasm as an antecedent and teacher well-being as an outcome19,56. By contrast, our study treats teacher enthusiasm (TE) as the outcome and teacher subjective well-being (TSW) as an influencing factor, aligning with the expectation that happier, more content teachers become more enthusiastic in teaching. In fact57, provides evidence that teachers who feel psychologically well exhibit greater enthusiasm for their work, supporting our approach. Additionally, TSW mediated the relationship between school leadership and school resilience58. Based on the relationships between TSW, SL, and TE, it was predicted that teacher subjective well-being may also have a mediating role in the relationship between these two variables, and the following first hypothesis of the study was formed:

H1

Teacher subjective well-being has a mediating role in the relationship between servant leadership and teaching enthusiasm.

The moderator role of distributed leadership

When principals provide help and support to teachers, it reduces teachers’ stress and increases their TSW59. Another type of leadership that moves away from hierarchical leadership models and distributes leadership to the school team, encouraging a high level of cooperation and teamwork, is DL60. This participatory and collaborative aspect of DL can support SL practices. Additionally, the literature review showed that DL could reduce teachers’ job stress61 and increase their satisfaction23,62. When teachers are satisfied with their jobs, their TSW is also affected63. Studies have shown that principals’ DL behaviors positively impact teachers’ well-being29,64,6562. pointed out that DL creates a collaborative climate in its positive effect on teachers’ mental health. Since distributed leadership fosters teamwork and collaboration, it facilitates servant leaders in supporting teachers more effectively, thereby positively influencing teacher subjective well-being. Based on the findings based on the relationships in the relevant literature, the second hypothesis of the current study was formed.

H2

Distributed leadership has a moderator effect on the relationship between servant leadership and subjective well-being.

The DL approach66, which focuses on interactions between subordinates and situations, can support teachers’ enthusiasm in the teaching processes. Existing literature provides evidence that when DL distributes responsibility, it improves teachers’ emotional factors such as confidence and enthusiasm67 and creates a sense of ownership in teachers for the school68. Teachers who embrace the school exhibit higher levels of well-being and demonstrate greater commitment to teaching69. Moreover, DL was found to be a predictor of teaching practices70 and teaching skills71. These results are theoretically consistent with the construct of teaching enthusiasm7. found that power distance had a negative moderating effect on the relationship between school leadership and teacher enthusiasm. Based on this theoretical basis, it is put forward that in schools where the power distance between teachers and principals is low, teachers have higher chances of autonomy and success in teaching72. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that the relationship between SL and TSW, as well as between SL and TE, will be stronger under conditions of high DL. In other words, the positive impact of SL on TSW and TE is expected to be more pronounced in schools where DL is high. This proposition is supported by previous research indicating that collaborative leadership environments may amplify the positive effects of servant leadership73. Furthermore, expectancy-value theory provides a theoretical justification for this assumption, as it posits that teachers’ motivation and enthusiasm for teaching will be enhanced when their expectations for support and empowerment are fulfilled through distributed leadership practices. Based on these theoretical considerations regarding the interaction of different leadership styles, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3

Distributed leadership has a moderator effect on the indirect effect of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm through subjective well-being.

Method

This cross-sectional study was designed to test the moderated mediation model using a quantitative approach.

Participants and data collection process

In the study, we reached participants from all provinces of Türkiye (81 provinces). To ensure broad geographical representation, volunteer teachers from various provinces across Turkey were included in the study. The number of participants per province varied due to the use of a convenience sampling method and differing levels of volunteer participation. This sampling strategy was selected to facilitate online data collection and enhance regional diversity. However, given the voluntary nature of participation, representation across provinces may not be entirely balanced. To mitigate this limitation and enhance the representativeness of the sample, the survey was distributed to 1,000 teachers nationwide, with deliberate efforts to ensure diversity in terms of gender, school type, educational background, and teaching experience. Prior to analysis, outliers were identified and excluded to improve the homogeneity of the dataset. These procedures aimed to increase the generalizability of the findings to the broader teaching population in Turkey. The inclusion criteria for participation required individuals to be currently employed as teachers in Turkey, have at least one year of professional experience, and have fully completed the online questionnaire. Teachers in administrative roles (e.g., principals or vice principals) and statistical outliers were excluded from the final sample. These procedures aimed to increase the generalizability of the findings to the broader teaching population in Turkey.

The online scale form, consisting of demographic questions and 30 items, was delivered to 1000 teachers via WhatsApp and e-mail due to time and cost efficiency74. As a result of the six-week data collection process, 848 teachers responded to the scales, providing a response rate of 85%. However, due to outliers, the data of 21 participants were excluded from the analysis was conducted on 827 teachers. In order to minimize social desirability and method bias, the scale items were presented to participants in the order of the dependent, mediator, moderator, and independent variables75. In the sample, 77% of the participating teachers were female (n = 637), while 23% were male (n = 190). In terms of teaching level, 7.3% were employed in preschool settings, 24.8% in elementary schools, 27.1% in middle schools, and 31.3% in high schools. Additionally, 9.6% were working in alternative educational settings such as special education institutions and community education centers. Regarding educational qualifications, 68.6% of the participants held a bachelor’s degree (n = 567), whereas 31.4% had earned a master’s degree (n = 260). The participants’ mean professional seniority was 15.39 years, with a standard deviation of 8.66.

Variables and data collection tools

Independent variable (servant leadership scale-SLS)

SLS is a single-dimension, 7-item scale (Sample item: My manager emphasizes the importance of helping others) developed by40 and adapted to Turkish by76. The scale is a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results of the scale for this study showed statistically appropriate fit within appropriate ranges (x2/sd = 3.77; RMSEA = 0.058, SRMR = 0.017, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98). Additionally, the Cronbach alpha (α) reliability coefficient of the SLS was calculated as 0.91, the mean variance value explained for convergent validity (AVE) was 0.60, and the composite reliability (CR) was 0.90.

Moderator variable (distributed leadership scale-DLS)

DLS is a single-dimension, 10-item scale developed by77 (Sample item: Our principal strives to create a school environment based on sharing). The scale is a five-point Likert-type scale that can be answered between 1 (never) and 5 (always). In the current study, the CFA results of the scale were determined to be within statistically appropriate ranges (x2/sd = 3.21; RMSEA = 0.052, SRMR = 0.015, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99). Additionally, the Cronbach alpha (α) reliability coefficient of the DLS was determined as 0.94, the AVE value for convergent validity was 0.62, and the CR value was 0.94.

Mediator variable (teacher subjective well-being scale-TSWS)

TSWS is a two-dimensional, 8-item scale developed by48 and adapted to Turkish by78. The scale is a four-point Likert-type scale that can be answered between 1 (Almost never) and 4 (Almost always). The scale’s school commitment (Sample item: I can really be myself in this school) and teaching efficacy (Sample item: I feel my teaching is effective and useful) dimensions consist of four items each. The confirmatory factor analysis results indicated that the scale data fit within statistically acceptable ranges (x2/sd = 3.20; RMSEA = 0.051, SRMR = 0.018, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.97). Additionally, the Cronbach alpha (α) reliability coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.85, 0.81, 0.85 for school commitment, teaching efficacy, and overall, respectively; AVE values for convergent validity were calculated as 0.53, 0.51, 0.52; and CR values were calculated as 0.81, 0.79, 0.80.

Dependent variable (teaching enthusiasm subscale-TESS)

TESS, a subscale of the teacher enthusiasm scale, was developed by4 and adapted into Turkish by79. The TESS we used for this study has 5 items (Sample item: Teaching is a great pleasure) and is answered on a five-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In our current study, we found that the subscale’s fit indices were within statistically acceptable ranges (x2/sd = 3.58; RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR = 0.038, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98). We also found the Cronbach alpha (α) reliability coefficient of the TESS to be 0.85, the AVE value for convergent validity to be 0.55, and the CR value to be 0.85.

Control variables

In the present study, gender, educational attainment, grade level taught, and professional seniority were incorporated into the model as control variables. This decision was informed by previous research demonstrating that these demographic characteristics can significantly impact teachers’ motivation to teach6,80. Accordingly, the core structural relationships between the independent and dependent variables were adjusted to account for the potential confounding effects of these factors, thereby enhancing the accuracy and interpretability of the model’s results.

Data analysis

We performed all analyses of our study with Mplus 8.3 and Process Macro. In this study, Mplus 8.3 software was utilized to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), descriptive statistics, and correlation analyses. Mplus was selected due to its capacity to manage missing data, support covariance-based structural equation modeling, and perform analyses under the assumptions of parametric statistics. In addition, mediation analyses were conducted using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro, while moderation and moderated mediation analyses were carried out using Model 8. We calculated Mahalanobis distance values for the extreme values of our data. The data from 21 participants whose Mahalanobis distance exceeded the chi-square (x2) threshold were removed from the dataset. We checked the Skewness and Kurtosis values of our data for normality assumption. We found that the Skewness values of our scales ranged from − 0.918 to −0.235, and the Kurtosis values ranged from − 0.533 to 0.126. The fact that Skewness and Kurtosis values were between − 1.5 and + 1.5 means that our data were normally distributed81. In our study, we also examined Q-Q graphs. We found that in all Q-Q graphs, the points did not stray too far from the 45-degree reference line. We found that in the context of linearity, the points in the Scatter plot graph formed a pattern close to the line. We examined the homoscedasticity assumption with the residual graph. We determined that the error terms remained constant in the residual graphs. In our study, the fact that the relationships between the independent variables were less than 0.90 (see Table 1), the VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values were between 1.546 and 3.661 and less than 5, the CI (Condition index) values were between 11.300 and 23.658 and less than 30, the tolerance values were between 0.273 and 0.647 and greater than 0.20, and the Durbin Watson value was 1.86, between 1.5 and 2.5, meant that there was no problem of collinearity and multicollinearity in our study82. Moreover, we evaluated the CFA fit of the scales used in the study by taking into account different fit indices (x2/sd < 4; RMSEA < 0.08; SRMR < 0.08; CFI > 0.90, TLI > 0.90)83,84.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study and pearson correlation analysis findings (n = 827).

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SL | 3.67 | 0.83 | - | 0.836** | 0.535** | 0.245** | 0.026 | 0.009 | −0.083* | −0.091** |

| 2. DL | 3.75 | 0.78 | - | 0.589** | 0.275** | 0.022 | −0.003 | −0.131** | −0.106** | |

| 3. TSW | 3.25 | 0.49 | - | 0.499** | 0.180** | 0.032 | −0.072* | −0.001 | ||

| 4. TE | 4.61 | 0.44 | - | −0.035 | −0.077* | −0.076* | −0.115** | |||

| 5. Professional Seniority | 15.39 | 8.67 | - | 0.168** | 0.119** | 0.104** | ||||

| 6. Gender | - | - | - | 0.158** | 0.051 | |||||

| 7. Level of Education | - | - | - | 0.142** | ||||||

| 8. Educational Level | - | - | - |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation, SL: Servant Leadership, DL: Distributed Leadership, TSW: Teacher Subjective Well-being, TE: Teaching Enthusiasm, Gender: The reference group is women, Level of Education: The reference group is preschool, Educational Level: The reference group is Bachelor’s degree.

We started our analysis by calculating descriptive statistics. Then, we performed mediation analysis by determining the direct and indirect effects between the variables. In the last stage, we reported the conditional indirect effects of the moderator mediation model at three different standard deviation levels (−1 SD, mean, + 1 SD). We examined 95% confidence intervals in 5000 resample analysis and in our study, we accepted the analysis results as statistically significant if the confidence intervals did not contain the value zero (0)85. Additionally, in our study, we applied Harman’s single factor test for common method bias86. The principal component analysis including the items related to all scales revealed a single factor structure explaining 42.33% of the variance, which was less than 50%. This result proves that there is no common method bias in our study87. To address potential common method bias, the full collinearity test proposed by88 was conducted. In this procedure, all constructs—independent, dependent, mediating, and moderating—were alternately treated as dependent variables, and their corresponding variance inflation factor (VIF) values were calculated. All VIF values were below the recommended threshold of 3.3, indicating that common method bias was not a concern in this study or existed only at a negligible level.

Findings

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analysis findings

We started the analyses of our study by calculating the descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) of the data and the Pearson correlation coefficients. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analysis findings of our study.

As seen in Table 1, servant leadership (M = 3.67, SD = 0.83), distributed leadership (M = 3.75, SD = 0.78) and teacher subjective well-being (M = 3.25, SD = 0.49) were above average and at a high level, while teaching enthusiasm (M = 4.61, SD = 0.44) was well above average and at a very high level. The standard deviations of all our scales varied between 0.44 and 0.83, indicating that teachers’ perceptions were homogeneous. Moreover, positive significant relationships were found between servant leadership and distributed leadership (r = 0.836, p < 0.01), teacher subjective well-being (r = 0.535, p < 0.01) and teaching enthusiasm (r = 0.245, p < 0.01); between distributed leadership and teacher subjective well-being (r = 0.589, p < 0.01) and teaching enthusiasm (r = 0.275, p < 0.01); and between teacher subjective well-being and teaching enthusiasm (r = 0.499, p < 0.01).

Findings regarding the hypotheses of the study

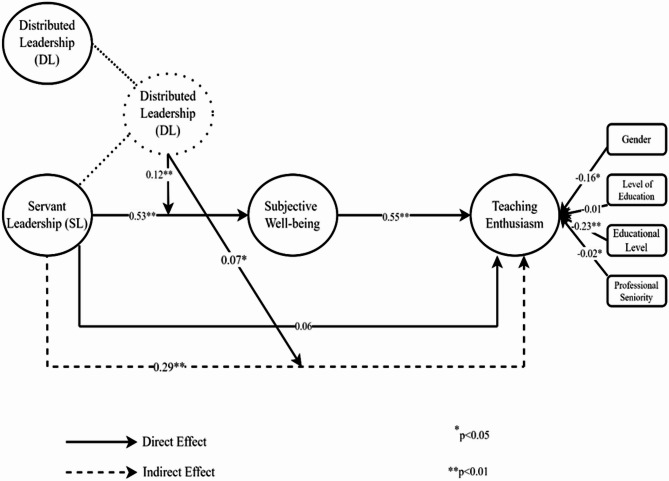

We tested the hypotheses of our study in order. In this context, we first examined the mediating effect of subjective well-being in the relationship between servant leadership and teaching enthusiasm. As can be understood from Table 2; Fig. 2, the direct effect of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm was not significant (β = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.1248, 0.0138]), while its effect on teacher subjective well-being was significant (β = 0.53, 95% CI [0.4720, 0.5862]). Moreover, the effect of teacher subjective well-being on teaching enthusiasm (β = 0.55, 95% CI [0.4806, 0.6211]) and the effect of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm through teacher subjective well-being were also significant (β = 0.29, 95% CI [0.2405, 0.3468]). This result regarding the mediation analysis supports our hypothesis H1.

Table 2.

Standardized coefficients for direct, mediator, moderator, and moderated mediation effects (n = 827).

| Effect Type | Independent Variable | Mediating Variable | Dependent Variable | Direct, Mediator, and Moderated Mediation Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | 95% CI [LCI-UCI] | ||||

| Direct Effect | SL | - | TE | 0.06 | 0.0353 | [−0.1248 0.0138] |

| SL | - | TSW | 0.53** | 0.0291 | [0.4720 0.5862] | |

| TSW | - | TE | 0.55** | 0.0358 | [0.4806 0.6211] | |

| Gender | - | TE | −0.16* | 0.0718 | [−0.2993 −0.0173] | |

| Level of Education | - | TE | −0.01 | 0.0276 | [−0.0601 0.0483] | |

| Educational Level | - | TE | −0.23** | 0.0648 | [−0.3525 −0.0982] | |

| Professional Seniority | TE | −0.02** | 0.0036 | [−0.0200 −0.0060] | ||

| Indirect Effect | SL | TSW | TE | 0.29** | 0.0264 | [0.2405 0.3452] |

| Moderator Effect | SL x DL | - | TSW | 0.12** | 0.0232 | [0.0764 0.1673] |

| Moderated Mediation Effect | SL x DL | TSW | TE | 0.07* | 0.0257 | [0.0167 0.1176] |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, SE: Standardized Error, CI: Confidence Interval, SL: Servant Leadership, DL: Distributed Leadership, TSW: Teacher Subjective Well-being, TE: Teaching Enthusiasm, Gender: The reference group is women, Level of Education: The reference group is preschool, Educational Level: The reference group is Bachelor’s degree.

Fig. 2.

Findings regarding the moderated mediation effect.

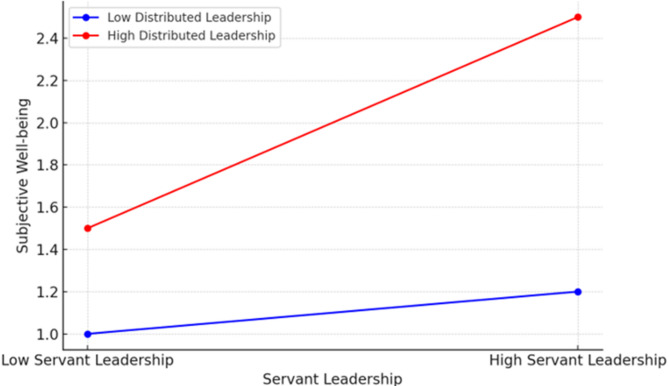

In our study, in line with hypothesis H2, we investigated the moderator effect of distributed leadership on the relationship between servant leadership and teacher subjective well-being (see: Fig. 2). After controlling gender, level of education, educational level, and professional seniority, we found that the interaction term (SL x DL) was significant with teacher subjective well-being (β = 0.12, 95% CI [0.0764, 0.1673]). This result confirms our hypothesis H2. We calculated the simple regression trend to determine whether the effect of servant leadership on teacher subjective well-being varied depending on distributed leadership (see Fig. 3). As can be understood from Table 3, the effect of servant leadership on teacher subjective well-being became stronger when distributed leadership was medium (β = 0.16, 95% CI [0.0660, 0.2601]) and high (β = 0.29, 95% CI [0.1739, 0.3960]). However, when distributed leadership was low (β = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.0619, 0.1443]), the effect of servant leadership on teacher subjective well-being was weak and statistically insignificant. In other words, the relationship between servant leadership and teacher subjective well-being became stronger in schools where distributed leadership was higher while in schools where distributed leadership was low, the relationship between servant leadership and teacher subjective well-being was weaker.

Fig. 3.

The moderator effect of distributed leadership on the relationship between servant leadership and teacher subjective well-being.

Table 3.

The effect of servant leadership on teacher subjective well-being by the levels of distributed leadership.

| Estimate | SE (Boot) | %95 CI | %95 CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 Standard Deviation | 0.04 | 0.0525 | −0.0619 | 0.1443 |

| Mean | 0.16 | 0.0494 | 0.0660 | 0.2601 |

| + 1 Standard Deviation | 0.29 | 0.0566 | 0.1739 | 0.3960 |

In our study, we finally tested our H3 hypothesis. In other words, we examined the effect of distributed leadership on the mediation model in cases where it was low (−1 SD), medium, and high (+ 1 SD). In this context, we found that distributed leadership had a moderator effect on the indirect effect of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm through teacher subjective well-being (β = 0.07, 95% CI [0.0167, 0.1176]) (see Table 2). Additionally, as seen in Table 4, we found that the moderated mediation index was also significant (Moderated Mediation Index = 0.06 95% CI [0.0384, 0.0980]). In other words, when distributed leadership was medium (β = 0.09, 95% CI [0.0311, 0.1495]) and high (β = 0.15, 95% CI [0.0903, 0.2246]), the indirect effect of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm through teacher subjective well-being was also strengthened. In cases where distributed leadership was low (β = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.0415, 0.0893]), the indirect effect of servant leadership was weaker and insignificant (see Table 4). These results support H3. Moreover, in the moderated mediation model, we found that some of the control variables such as gender (β = −0.16, 95% CI [−0.2993, −0.0173]), educational level (β = −0.23, 95% CI [−0.3525, −0.0982]), and professional seniority (β = −0.02, 95% CI [−0.0200, −0.0060]) had significant effects on teacher enthusiasm. On the other hand, level of education did not have any significant effect on teaching enthusiasm (β = −0.01, 95% CI [−0.0601, 0.0483]).

Table 4.

The indirect effect of servant leadership on teaching enthusiasm through teacher subjective wellbeing at different levels of distributed leadership.

| Estimate | SE (Boot) | %95 CI | %95 CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderated Mediation Index | 0.06 | 0.0150 | 0.0384 | 0.0980 |

| −1 Standard Deviation | 0.02 | 0.0334 | −0.0415 | 0.0893 |

| Mean | 0.09 | 0.0304 | 0.0311 | 0.1495 |

| + 1 Standard Deviation | 0.15 | 0.0345 | 0.0903 | 0.2246 |

Discussion

Although teaching enthusiasm is known to benefit educational outcomes56,89, few studies have examined the role of principals’ leadership in influencing it7,12. Guided by theories of social exchange and expectancy-value, we examined the indirect effect of SL on TE based on this need. The first finding was that SL had an indirect effect on TE through TSW. Teachers who work with a principal who serves as a role model, instills confidence, and provides essential information and resources are likely to experience reduced stress and burnout. Such teachers tend to feel better about themselves and enjoy the teaching process more fully. The significant mediating effect of subjective well-being underscores the importance of teachers’ emotional states in Türkiye. Due to the centralized and hierarchical approach in school systems, teacher autonomy is limited in Türkiye. Teachers are expected to implement rules and regulations without objection90. Thus, in centralized systems like Türkiye’s, teachers’ well-being must be high for effective teaching. It is therefore crucial that school principals actively support teacher subjective well-being. This finding provides a notable contribution to the literature by demonstrating that teacher subjective well-being mediates the relationship between school leadership and positive teacher attitudes56,91. Our findings also contribute to the literature showing the contribution of teachers to teaching processes through the effect of school leadership on teacher psychological characteristics7,92,93.

Our second finding suggests that servant leadership can channel teachers’ emotions toward school goals, and thiseffect is enhanced when leadership responsibilities are shared. The reason for this may be that when teachers can participate in decision-making processes and carry out collaborative teamwork, participating in collaborative teamwork helps teachers feel supported rather than isolated94. In other words, teachers may experience greater well-being when they feel supported and valued in their institutions as a result of servant and distributed leadership95. stated that a leader who creates a culture of shared responsibility and collaboration by distributing leadership in a supportive structure will contribute to the well-being of teachers. Turkish culture values paternalistic leadership96, under which principals may see themselves as supportive “parents” to teachers. This situation enhances teachers’ trust in their principals and positively influences their psychological well-being97. Therefore, our study results show how important the serving and delegating roles of principals are for the subjective well-being of teachers in the context of Turkish schools. Our study findings are consistent with previous study results that school leadership emerged as one of the important factors of teacher well-being, in line with traditional Turkish culture57,59,64,65. Our finding that teacher well-being mediates the relationship between leadership and teaching enthusiasm is consistent with the results reported by58 in a different educational context, and further extends the established mediating role of well-being to encompass teachers’ enthusiasm for teaching.

The final finding of our study proved that DL among principals and teachers supported the effect of SL on TE through TSW98. reported that teachers in schools exhibiting high levels of distributed leadership experienced a stronger sense of commitment to the school and were more willing to strive to overcome work-task challenges. A possible explanation is that teachers feel valued when their principals share leadership responsibilities with them. Our study results support evidence from studies suggesting that when principals encourage collaboration, shared responsibility, participatory decision-making, and work as a team, teachers’ positive attitudes toward teaching can increase9,99. The fact that servant leaders prioritize followers’ interests over their own and focus on collective goals, and that distributed leaders delegate authority, can help eliminate power distance and hierarchy. Eliminating hierarchical management in school communities can motivate teachers to contribute to school management with their professional knowledge939. proved that power distance and school leadership are determining factors on teaching enthusiasm and differentiated instruction in Turkish schools. In our study, when the principal exhibited DL behaviors as well as SL behaviors, TSW levels increased. This ultimately contributed to the teachers’ TE. These results suggest our model aligns well with Türkiye’s centralized, hierarchical education system. They also reinforce the idea that integrated leadership approaches can be more effective than single-style approaches7,92.

Theoretical implications

The literature generally focuses on the consequences of teaching enthusiasm4, but studies on what fosters this enthusiasm are limited89,100. Theoretically, this study provides evidence for the importance of servant leadership, subjective well-being, and distributed leadership in promoting teachers’ teaching enthusiasm in the context of Turkish schools. From a theoretical standpoint, the study lends support for social change theory, which posits that when principals act in alignment with teachers’ interests and provide appropriate support, teachers are more likely to respond with increased motivation and enthusiasm. This finding is also consistent with expectancy-value theory, suggesting that teachers’ enthusiasm tends to rise when their expectations regarding support and recognition are fulfilled. Secondly, while prior studies on school leadership have predominantly examined the effects of a single leadership style, this study explores the combined and comparative effects of servant leadership (SL) and distributed leadership (DL). In doing so, it contributes to the advancement of school leadership theory by offering a more integrated and comprehensive perspective. In this respect, the study offers an original contribution to the field of educational administration and leadership by integrating multiple leadership perspectives and highlighting their joint impact on teacher outcomes. Third, by situating the research within the Turkish context, this study contributes to a culturally grounded perspective to the field of educational leadership. Fourth, it provides insights into how the combination of servant and distributed leadership in Turkish schools can shape teacher outcomes even in challenging contextual and cultural conditions within a centralized and high-power-distance education system. This finding suggests that effective leadership can mitigate some of the negative aspects of a restrictive context. Fifth, the moderating role of DL reinforces the notion that distributed leadership functions as a complementary, rather than competitive, approach within school leadership frameworks. Finally, by incorporating teacher-related outcome variables—namely, teacher subjective well-being and teaching enthusiasm—this study underscores the importance of adopting a teacher-centered lens in educational administration and leadership research. From this perspective, the study highlights that the ultimate aim of school leadership should be to support teachers, thereby enhancing student development.

Implications for policy and practice

Our findings indicate that principals’ servant and distributed leadership practices have a positive influence on teachers, with several implications for educational policy and practice. In centralized education systems such as Türkiye’s, policies should be designed to promote greater teacher participation and autonomy. Educational authorities can develop guidelines and evaluation frameworks that prioritize collaborative and service-oriented leadership over traditional hierarchical approaches. Moreover, principals who successfully implement such leadership models can be recognized and incentivized through formal rewards. Institutionalizing these practices could foster an environment where integrated leadership approaches thrive, ultimately enhancing teacher enthusiasm and performance. To support teachers’ emotional well-being and sustain their motivation, we recommend that school principals actively demonstrate servant and distributed leadership behaviors. More specifically, principals aiming to enhance teacher well-being and enthusiasm should cultivate a school climate that delegates meaningful responsibilities, fosters mutual trust, and promotes collegial collaboration. Given the critical role of TE and TSW, teacher education and professional development programs should incorporate training on stress management, relationship-building, and collaborative practices. These competencies can help teachers maintain their enthusiasm even in demanding work environments. Equipping teachers with such skills not only enables them to benefit from supportive leadership when it is present, but also helps preserve their motivation over time. Finally, we recommend that policymakers in centralized systems develop initiatives aimed at increasing principal–teacher interaction and expanding teacher autonomy.

Limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

The responses to the scales we used in the study are based on the self-reports of the participants. Therefore, common method bias may have occurred in the study. Another limitation of our study stems from social desirability. Although anonymity and random ordering of questions were used to reduce bias, common method bias and social desirability might still influence responses. In order to eliminate these problems, school principals as well as teachers can be involved in studies. Given its nature and contextual characteristics, distributed leadership is ideally measured at the school level using multilevel analysis; however, the online data collection method did not allow for this approach. Additionally, since this study was designed as a cross-sectional one, it cannot reveal the causal relationships between the variables. Longitudinal studies are needed to better determine the direction of the variables. Our study was conducted in Turkish educational schools where the bureaucratic and centralized education system is dominant. Therefore, the results of our study are not valid for all education systems. For this reason, caution should be exercised in generalizing our study results to other countries. It would be beneficial to repeat our study with qualitative or mixed methods for a clearer and deeper understanding of the integrated leadership approach. Future research should be conducted in educational settings with diverse cultural and systemic characteristics to assess the generalizability of the present findings. Subsequent studies may also explore the integration of other leadership styles (e.g., servant and transformational leadership) to determine whether similar advantages emerge or to compare the relative effectiveness of different leadership combinations. Moreover, future research could investigate how leadership approaches indirectly influence student-related outcomes—such as academic achievement and engagement—in conjunction with TSW and TE. Although this study has certain limitations, it offers meaningful contributions to the educational leadership literature. Future studies are encouraged to build on and expand these findings by employing diverse methodological approaches and exploring additional outcome variables.

Conclusion

Specifically, the positive impact of SL on TSW —and consequently on teachers’ enthusiasm—is amplified under conditions of high DL. This finding is noteworthy, as it empirically demonstrates how distinct leadership styles can operate synergistically rather than in isolation. The observed interaction between SL and DL represents a novel contribution to the educational leadership literature. In centralized education systems such as Türkiye’s, where hierarchical authority tends to dominate, this integrated leadership model has proven effective in enhancing teacher motivation. By emphasizing the complementary nature of SL and DL, the study underscores the theoretical value of multi-dimensional leadership frameworks. Furthermore, it offers practical guidance for school leaders and policymakers seeking to foster positive teacher attitudes. Principals who prioritize teachers’ well-being while actively distributing leadership responsibilities can create supportive school environments that sustain teachers’ engagement, motivation, and instructional commitment over time.

Author contributions

As the sole author, I contributed 100% to this work.

Funding

I declare that I have not received any financial support for the conduct of this research.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to high protection on participants’ personal information but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. For inquiries regarding the data and materials in this paper, please contact the corresponding author at eminedogan@ksu.edu.tr.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

I confirm that all methods in the research have been conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. This study adheres to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Siirt University (07.10.2024-7678). All participants provided voluntary informed consent and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Furthermore, our data underwent anonymization procedures to ensure participant privacy.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Vergara, C. R. & Grit Self-efficacy and goal orientation: A correlation to achievement in statistics. Int. J. Educ. Res.8, 89–106 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acton, R. & Glasgow, P. Teacher well-being in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Aust J. Teach. Educ.40 (8), 99–114. 10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.6 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodlad, J. A Place Called School (McGraw-Hill, 2004).

- 4.Kunter, M. et al. Teacher enthusiasm: dimensionality and context specificity. Contemp. Educ. Psychol.36 (4), 289–301. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.07.001 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, P. H., Mayer, D. & Malmberg, L. E. Teacher well-being in the classroom: A micro-longitudinal study. Teach. Teach. Educ.115, 103720. 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103720 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasalak, G. & Dağyar, M. Teacher burnout and demographic variables as predictors of teachers’ enthusiasm. Part. Educ. Res.9, 280–296. 10.17275/per.22.40.9.2 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Özdemir, M., Kaymak, M. N. & Çetin, O. U. Unlocking teacher potential: the integrated influence of empowering leadership and authentic leadership on teacher self-efficacy and agency in Turkey. Educ. Manag Adm. Leadersh.1, 1–22. 10.1080/02188791.2022.2084361 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gencer, M. Teaching in terms of occupational professionalization: A qualitative analysis. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Acad. Res.7, 21–41 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Özdemir, N., Kılınç, A. Ç. & Turan, S. Instructional leadership, power distance, teacher enthusiasm, and differentiated instruction in turkey: testing a multilevel moderated mediation model. Asia Pac. J. Educ.43, 912–928. 10.1080/02188791.2022.2084361 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, E. & Ye, Y. Understanding how to ignite teacher enthusiasm: the role of school climate, teacher efficacy, and teacher leadership. Curr. Psychol.43, 13241–13254. 10.1007/s12144-023-05387-2 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallinger, P. A review of three decades of doctoral studies using the principal instructional management rating scale: A lens on methodological progress in educational leadership. Educ. Adm. Q.47, 271–306. 10.1177/0013161X10383412 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheppard, B. S., Hurley, N. P. & Dibbon, D. C. Distributed leadership, teacher morale, and teacher enthusiasm: Unravelling the leadership pathways to school success. American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting (2010).

- 13.Uslukaya, A., Demirtas, Z. & Alanoglu, M. The relationship of trust in the principal and servant leadership’s interaction with work engagement and teacher passion: A multilevel moderated mediation analysis. Curr. Psychol.10.1007/s12144-024-06926 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenleaf, R. K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness (Paulist, 1977).

- 15.Spears, L. C. Reflections on Leadership: How Robert K. Greenleaf’s Theory of Servant Leadership Influenced Today’s Top Management Thinkers (Wiley, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbuto, J. E. & Wheeler, D. W. Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group. Organ. Manag. 31 (3), 300–326. 10.1177/1059601106287091 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerit, Y. The effects of servant leadership behaviors of school principals on teachers’ job satisfaction. Educ. Manag Adm. Leadersh.37 (5), 600–623. 10.1177/1741143209339650 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull.95 (3), 542–575 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shao, G. A model of teacher enthusiasm, teacher self-efficacy, grit, and teacher well-being among English as a foreign language teachers. Front. Psychol.14, 1169824. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1169824 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, Y., Liu, S., Aramburo, C. A. & Jiang, J. Leading by serving: how can servant leadership influence teacher emotional well-being? Educ. Manag Adm. Leadersh.1, 1–23. 10.1177/17411432231182250 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spillane, J. P. Distributed Leadership (Jossey-Bass, 2006).

- 22.Bellibaş, M. Ş., Gümüş, S. & Kılınç, A. Ç. Distributed leadership and teacher practices: mediating roles of teachers’ autonomy, professional collaboration, and self-efficacy. Educ. Stud.47 (5), 521–536. 10.1080/03055698.2020.1793301 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun, A. & Xia, J. Teacher-perceived distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: a multilevel SEM approach using the 2013 TALIS data. Int. J. Educ. Res.92, 86–97. 10.1016/j.ijer.2018.09.006 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hulpia, H., Devos, G. & Van Keer, H. The influence of distributed leadership on teachers’ organizational commitment: a multilevel approach. J. Educ. Res.103 (1), 40–52. 10.1080/00220670903231201 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J. & Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (McGraw Hill, 2010).

- 26.Bellibaş, M. Ş., Gümüş, S. & Chen, J. The impact of distributed leadership on teacher commitment: the mediation role of teacher workload stress and teacher well-being. Br. Educ. Res. J.50 (2), 814–836. 10.1002/berj.3944 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, J., Qiang, F. & Kang, H. N. Distributed leadership, self-efficacy and well-being in schools: a study of relations among teachers in Shanghai. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun.10, 1–9. 10.1057/s41599-023-01696-w (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marks, H. M. & Printy, S. M. Principal leadership and school performance: an integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educ. Adm. Q.39 (3), 370–397 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwan, P. Is transformational leadership theory passé? Revisiting the integrative effect of instructional leadership and transformational leadership on student outcomes. Educ. Adm. Q.56 (2), 321–349. 10.1177/0013161X19861137 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gümüş, S., Hallinger, P., Cansoy, R. & Bellibaş, M. Ş. Instructional leadership in a centralized and competitive educational system: a qualitative meta-synthesis of research from Turkey. J. Educ. Adm.59 (6), 702–720. 10.1108/JEA-04-2021-0073 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Çetin, M. & Kıral, B. Opinions of teachers and administrators related to teacher empowerment of school administrators. Mediterr. J. Educ. Res.12 (26), 281–310. 10.29329/mjer.2018.172.15 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yunus, M., Suakrno, S. & Rosyadi, K. I. Teacher empowerment strategy in improving the quality of education. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. Res.4 (1), 32–36 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aslanargun, E. & Tarku, E. Expectations of teachers from inspectors about professional supervision and guidance. Educ. Adm. Theor. Pract.20 (3), 281–306 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.MoNE (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of National Education). Türkiye Yüzyılı Maarif Modeli, Okul Yöneticilerinin Rolleri Ve Öğrenme-Öğretme Süreçlerini İzleme Ve Değerlendirme Kılavuzu (MoNE, 2024). (in Turkish).

- 35.Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life (Wiley, 1964).

- 36.Wigfield, A. Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation: A developmental perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev.6, 49–78. 10.1007/BF02209024 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Somech, A. & Oplatka, I. Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Schools: Examining the Impact and Opportunities Within Educational Systems (Routledge, 2014).

- 38.Bass, B. M. & Avolio, B. J. Improving Organizational Effectiveness Through Transformational Leadership (Sage, 1994).

- 39.Svensson, P. G., Jones, G. J. & Kang, S. The influence of servant leadership on shared leadership development in sport for development. J. Sport Dev.10 (1), 17–24 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone, A. G., Russell, R. F. & Patterson, K. Transformational versus servant leadership: a difference in leader focus. Leadersh Organ. Dev. J.25 (4), 349–361. 10.1108/01437730410538671 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith, C. The leadership theory of Robert K. Greenleaf. (2005). http://www.carolsmith.us/downloads/640greenleaf.pdf

- 42.Hale, J. R. & Fields, D. L. Exploring servant leadership across cultures: A study of followers in Ghana and the USA. Leadership3, 397–417. 10.1177/1742715007082964 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liden, R. C. et al. Servant leadership: validation of a short form of the SL-28. Leadersh. Q.26, 254–269. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibb, C. A. An interactional view of the emergence of leadership. Aust J. Psychol.10, 101–110 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H. & Henderson, D. Servant leadership: development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q.19, 161–177. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris, A. Distributed leadership and school improvement: leading or misleading? Educ. Manag Adm. Lead.32, 11–24. 10.1177/1741143204039297 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol.55 (1), 68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baloch, K. & Akram, D. M. Effect of teacher role, teacher enthusiasm and entrepreneur motivation on startup, mediating role technology. Oman Chapter Arab. J. Bus. Manag Rev.7 (4), 1–14. 10.12816/0052284 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kunter, M. et al. Students’ and mathematics teachers’ perceptions of teacher enthusiasm and instruction. Learn. Instr. 18 (5), 468–482. 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.008 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryff, C. D. & Keyes, C. L. M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.69 (4), 719–727 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Renshaw, T. L., Long, A. C. J. & Cook, C. R. Assessing teachers’ positive psychological functioning at work: development and validation of the teacher subjective Well-being questionnaire. Sch. Psychol. Q.30 (2), 289–306. 10.1037/spq0000112 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dooley, L. M. et al. Does servant leadership moderate the relationship between job stress and physical health?. Sustainability12(16), 6591. 10.3390/su12166591 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li, Y., Diwan, L., Tu, Y. & Liu, J. How and when servant leadership enhances life satisfaction. Pers. Rev.47 (5), 1077–1093. 10.1108/PR-07-2017-0223 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schowalter, A. F. & Volmer, J. Trajectories and associations of perceived servant leadership and teacher exhaustion during the first months of a crisis. Occup. Health Sci.10.1007/s41542-024-00206-x (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moè, A. & Katz, I. Need satisfied teachers adopt a motivating style: the mediation of teacher enthusiasm. Learn. Individ Differ.99, 102203. 10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102203 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu, Y. & Wang, J. The mediating role of teaching enthusiasm in the relationship between mindfulness, growth mindset, and psychological well-being of Chinese EFL teachers. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun.11 (1), 1–15. 10.1057/s41599-024-03694-y (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karabiyik, B. & Korumaz, M. Relationship between teacher’s self-efficacy perceptions and job satisfaction level. Procedia-Soc Behav. Sci.116, 826–830. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.305 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Limon, İ., Bayrakcı, C., Hamedoğlu, M. A. & Aygün, Z. The mediating role of subjective well-being in the relationship between empowering leadership and organizational resilience. Hacettepe Univ. J. Educ.38 (3), 367–379. 10.16986/HUJE.2023.491 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Langford, S. & Crawford, M. Walking with teachers: A study to explore the importance of teacher well-being and their careers. Manag Educ.39 (2), 89–96. 10.1177/08920206221075750 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spillane, J. P. Leadership and learning: conceptualizing relations between school administrative practice and instructional practice. Societies5 (2), 277–294. 10.3390/soc5020277 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rabindarang, S., Bing, K. W., Khoo, B. & Yin, K. Y. The impact of demographic factors on organizational commitment in technical and vocational education. Malays J. Res.2 (1), 56–61 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu, Y., Bellibaş, M. Ş. & Gümüş, S. The effect of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: mediating roles of supportive school culture and teacher collaboration. Educ. Manag Adm. Lead.49 (3), 430–453. 10.1177/174114322091043 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song, H., Gu, Q. & Zhang, Z. An exploratory study of teachers’ subjective well-being: Understanding the links between teachers’ income satisfaction, altruism, self-efficacy and work satisfaction. Teach. Teach. Theor. Pract.26 (1), 3–31. 10.1080/13540602.2020.1719059 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu, L., Liu, P., Yang, H., Yao, H. & Thien, L. M. The relationship between distributed leadership and teacher well-being: the mediating roles of organisational trust. Educ. Manag Adm. Lead.52 (4), 837–853. 10.1177/17411432221113683 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Windlinger, R. Leadership in schools and teacher well-being: an investigation of influence processes. (Doctoral thesis, Univ. of Fribourg, 2021)

- 66.Spillane, J. P. Distributed leadership. Educ. Forum. 69 (2), 143–150 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hallinger, P., Gümüş, S. & Bellibaş, M. Ş. ‘Are principals instructional leaders yet?’ A science map of the knowledge base on instructional leadership, 1940–2018. Scientometrics122 (3), 1629–1650. 10.1007/s11192-020-03360-5 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simon, N. S. & Johnson, S. M. Teacher turnover in high-poverty schools: what we know and can do. Teach. Coll. Rec. 117 (3), 1–36. 10.1177/016146811511700305 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ballantyne, J. & Retell, J. Teaching careers: Exploring links between well-being, burnout, self-efficacy and praxis shock. Front. Psychol.10, 2255. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02255 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bellibaş, M. Ş., Kılınç, A. Ç. & Polatcan, M. The moderation role of transformational leadership in the effect of instructional leadership on teacher professional learning and instructional practice: an integrated leadership perspective. Educ. Adm. Q.57 (5), 776–814. 10.1177/0013161x211035079 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu, P. Motivating teachers’ commitment to change through distributed leadership in Chinese urban primary schools. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 34 (7), 1171–1183. 10.1108/IJEM-12-2019-0431 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shengnan, L. & Hallinger, P. Unpacking the effects of culture on school leadership and teacher learning in China. Educ. Manag Adm. Lead.49 (2), 214–233. 10.1177/1741143219896042 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., van Dierendonck, D. & Liden, R. C. Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh. Q.30 (1), 111–132. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goodfellow, L. T. An overview of survey research. Respir Care. 68 (9), 1309–1313. 10.4187/respcare.11041 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.MacKenzie, S. B. & Podsakoff, P. M. Common method bias in marketing: causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 88 (4), 542–555. 10.1016/j.jretai.2012.08.001 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kılıç, K. C. & Aydın, Y. Hizmetkâr liderlik Ölçeğinin Türkçe uyarlaması: Güvenirlik ve Geçerlik Çalışması. KMÜ Sos Ekon. Araş Derg. 18 (30), 106–113 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Özer, N. & Beycioğlu, K. The development, validity and reliability study of distributed leadership scale. Elem. Educ. Online. 12 (1), 77–86 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ergün, E. & Sezgin Nartgün, Ş. Adaptation of teacher subjective wellbeing questionaire (tswq) to turkish: A validity and reliability study. Sakarya Univ. J. Educ.78 (2), 385–397. 10.19126/suje.296824 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kasalak, G. & Dağyar, M. The adaptation of teacher enthusiasm scale into Turkish language: validity and reliability study. Int. J. Curr. Instr. 12 (2), 797–814 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ritu, M. S. & Singh, A. A study of teaching effectiveness of secondary school teachers in relation to their demographic. Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev.1 (6), 97–107 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th edn (Pearson, 2013).

- 82.Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics 4th edn (SAGE, 2013).

- 83.Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ Model.6 (1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th edn (Guilford Press, 2015).

- 85.Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 40 (3), 879–891. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harman, H. H. Modern Factor Analysis, 2nd edn (University of Chicago Press, 1967).

- 87.Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol.88 (5), 879–900. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kock, N. & Lynn, G. S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: an illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst.13, 546–580. 10.17705/1jais.00302 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kouhsari, M., Huang, X. & Wang, C. The impact of school climate on teacher enthusiasm: the mediating effect of collective efficacy and teacher self-efficacy. Camb. J. Educ.54 (2), 143–163. 10.1080/0305764X.2023.2255565 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aydın, Y. The relationship of organizational silence with favoritism in school management and self-efficacy perception of teachers. Educ. Adm. Theor. Pract.22 (2), 165–192 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dilekçi, Ü. & Limon, İ. The mediator role of teachers’ subjective well-being in the relationship between principals’ instructional leadership and teachers’ professional engagement. Educ. Adm. Theor. Pract.26 (4), 743–798 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bellibaş, M. Ş., Gümüş, S. & Liu, Y. Does school leadership matter for teachers’ classroom practice? The influence of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on instructional quality. Sch. Effect Sch. Improv.32 (3), 387–412. 10.1080/09243453.2020.1858119 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Özdoğru, M., Doğuş, Y. & Akyürek, M. İ. The mediating role of the principal–teacher relationship in innovative school leadership and teacher professional learning according to Turkish teachers’ perceptions. Behav. Sci.15 (4), 450. 10.3390/bs15040450 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang, J., Yin, H. & Wang, T. Exploring the effects of professional learning communities on teacher’s self-efficacy and job satisfaction in Shanghai. China Educ. Stud.49 (1), 17–34. 10.1080/03055698.2020.1834357 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brady, J. & Wilson, E. Teacher well-being in england: teacher responses to school-level initiatives. Camb. J. Educ.36 (3), 1–19. 10.1080/0305764X.2020.1775789 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ağalday, B. & Dağlı, A. The investigation of the relations between paternalistic leadership, organizational creativity and organizational dissent. Res. Educ. Adm. Lead.6 (4), 748–794. 10.30828/real/2021.4.1 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karadaş, H. & Özer, N. The management styles of the school principals and the trust levels of the school principals based on the teachers’ opinions. Int. J. Soc. Res.17 (34), 125–153 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 98.Börü, N. & Bellibaş, M. Ş. Comparing the relationships between school principals’ leadership types and teachers’ academic optimism. Int. J. Lead. Educ.1, 1–19. 10.1080/13603124.2021.1889035 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zheng, X., Yin, H. B. & Liu, Y. The relationship between distributed leadership and teacher efficacy in china: the mediation of satisfaction and trust. Asia-Pac Educ. Res.28 (6), 509–518. 10.1007/s40299-019-00451-7 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Burić, I. & Moè, A. What makes teachers enthusiastic: The interplay of positive affect, self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Teach. Teach. Educ.89, 103008. 10.1016/j.tate.2019.103008 (2020). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement