Abstract

Arsenic (As) contamination in rice poses significant health risks due to the toxicity of certain arsenicals. This study presents an improved, time-efficient method for quantifying arsenite (AsIII), arsenate (AsV), dimethylarsinic acid (DMA), and monomethylarsonic acid (MMA) in commercial white and brown rice using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with inductively coupled plasma mass-spectrometry (HPLC–ICP–MS). The method incorporates chromatographic modifiers and ion-pairing agents in the mobile phase, reducing overall retention time to less than 4 minutes while enhancing peak separation. Method optimization, focusing on the solid-to-liquid ratio (g/L) and extraction time (minutes), was validated using the certified reference material (SRM 1568b Rice Flour), with measured concentrations showing good agreement with certified values. The MMA was excluded from the final analysis due to its low concentration in rice samples and minimal risk contribution. Arsenic species in rice followed the trend AsIII > DMA > AsV. No significant association was found between As levels and country of origin, but certain brown (MR 27, MR 29) and white (MR 10, MR 14) rice samples exceeded the European Commission’s limit for inorganic As. Health risk assessments showed all rice samples had a target hazard quotient above 1, indicating potential non-carcinogenic risks. Additionally, estimated cancer risks exceeded the 10–3 (1 in 1000 lifetime risk) threshold under the revised cancer slope factor (CSF) value. This optimized method offers a reliable approach for detecting and quantifying As species in rice, aiding food safety monitoring and regulatory efforts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10653-025-02723-2.

Keywords: Rice, Inorganic arsenic, Speciation analysis, HPLC, ICP-MS, Risk assessment

Introduction

Rice remains as an important food commodity on the planet, feeding nearly 4 billion people. It is predicted that global rice demand will increase by up to 25% between 2010 and 2030 (International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), 2019). Rice is grown in more than 100 countries, but 90% of global production comes from 14 Asian countries (Islam et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2020). Contamination of As is a global concern that transcends economic boundaries (Fig. 1). Arsenic contamination in rice has been a significant global concern due to its toxicological effects and widespread consumption. It typically ranges from 0.08 to 0.20 mg/kg in various national samples, establishing a recognised global baseline (Zavala & Duxbury, 2008). Cereals, including rice, are a significant source of inorganic arsenic (iAs) to humans. This is further corroborated by total diet studies from Japan (Suzuki et al., 2022), Germany (Hackethal et al., 2021), Sweden (Kollander et al., 2019), Hong Kong (Wong et al., 2013), and Italy (Cubadda et al., 2016). While seafood has the highest quantities of As, it is mostly in the form of arsenobetaine (AsB), a less harmful organic form of As (Jayakody et al., 2024). However, in rice, the predominant As species are dimethylarsinic acid (DMA) and the inorganic types, arsenite (AsIII) and arsenate (AsV), all of which are known to cause toxicity (Mandal & Suzuki, 2002; Mawia et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2013).

Fig. 1.

Distribution and speciation of arsenic species in rice from various rice-consuming countries. Base map courtesy of QGIS software version 3.28.5

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies As and its inorganic compounds as Group 1, “carcinogenic to humans”, while MMA and DMA are placed in Group 2B, “possibly carcinogenic to humans”, according to existing toxicological reports. Arsenobetaine and other organic arsenicals, such as arsenolipids and arsenosugars, are categorised as Group 3, "not classified in terms of their carcinogenicity to humans”. Therefore, understanding these variations is crucial for assessing the potential health risks associated with rice consumption, as the bioavailability of As can differ based on the rice type and its geographical origin. Among the various types of rice, brown and white rice are the most consumed forms worldwide. In brown rice, the bran and germ layers are left intact, which is often considered more nutritious, whereas white rice undergoes milling and polishing to remove these outer layers (Bao, 2023). Regulatory agencies, such as the Codex Alimentarius Commission and the European Union Commission Regulation, have established maximum allowable limits for As specifically in husked (brown) and polished (white) rice, reflecting the significance of these two forms in international food safety standards. As rice is typically consumed in its fully milled (white) form, and brown rice continues to gain popularity for health-conscious consumers, understanding As levels in both types is essential for assessing dietary exposure risks (Farrell et al., 2021).

Some countries heavily rely on imports for their rice consumption, making it crucial to maintain food safety and quality to prevent potential contamination and protect consumers who otherwise have no direct exposure to As except through food (Bundschuh et al., 2022). For instance, in the UAE, recent trials in Sharjah have focused on cultivating rice in the desert with water that has undergone desalination and saltwater-resistant hybrid rice varieties (United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service, 2021). Meanwhile, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) revealed that although Lebanon's weather is favourable for growing cereals, high costs incurred from maintaining this crop limit its feasibility (Dal et al., 2021). Therefore, these nations primarily rely on rice imports to fulfil local demand. Similarly, the State of Qatar and the rest of the Gulf Cooperation Council rely on imports from countries like China, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Egypt, the United States of America, and Australia, which have histories of As contamination (Bundschuh et al., 2022). Additionally, the Bahamas relies on rice imports, with per capita consumption estimated at approximately 18.6 kg (Watson & Gustave, 2022). This emphasises the critical importance of maintaining good standards for food safety and quality to prevent potential contamination and protect consumers who rely on imported rice.

Speciation analysis poses a continuous challenge, primarily due to the necessity for precise extraction and preservation of species integrity. In the context of complex food matrices, the key difficulty lies in achieving efficient extraction of As species without inducing their chemical transformation. This process is critical to ensure complete destruction of the matrix while avoiding analyte loss or contamination (Costa et al., 2016). Using the most advanced analytical techniques, over 300 species of As have been found (Xue et al., 2022). While some As species, such as arsenosugars and AsB, demonstrate stability, others like AsIII, AsV, MMAIII, DMAIII, As glutathionines (As-GSH), and As-phytochelatin (As–PC) are less stable (Maher et al., 2015). The effective separation of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and the sensitive detection of Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) have been jointly applied in multiple studies to analyze As species in rice grains (Reid et al., 2020). Although methods for As speciation in rice using HPLC-ICP-MS are already in place, ongoing studies remain important to refine these approaches, aiming to reduce costs, time, and increase practicality for routine use. Given the varying chemical polarities of As species and the inherent complexity of different food matrices, a one-size-fits-all extraction method remains unattainable. Consequently, it is widely recommended that extraction conditions be tailored to suit the specific analytes and matrix involved in each study (Tibon et al., 2021).

A wide range of protocols have been developed for As extraction, varying significantly in terms of solvent systems, extraction temperatures, durations, and instrumental configurations. Traditional techniques commonly relied on physical agitation or sonication to facilitate extraction (Amore et al., 2023; Chajduk & Polkowska-Motrenko, 2019; Costa et al., 2015). More contemporary approaches favour heat-assisted extractions using strong acids such as nitric acid (HNO3) (Urango-Cárdenas et al., 2021), hydrochloric acid (HCl) (Zhao et al., 2023), or trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (Islam et al., 2017a). However, these low-pH conditions often lead to poor reproducibility and undesirable redox changes, particularly the reduction of AsV to AsIII, which undermines analytical accuracy (Narukawa et al., 2014). To reduce such interconversion and improve recovery in carbohydrate-rich matrices like rice, water has been employed as a gentler extractant (Narukawa & Chiba, 2010). Despite this, aqueous extraction typically demands high temperatures (> 90 °C) and prolonged extraction times (2–4 h), rendering it less suitable for routine or high-throughput analysis (Kobayashi & Shikino, 2014).

Chromatographic separation methods also vary considerably (Reid et al., 2020). Ion-pair reversed-phase columns, though operated with similar mobile phase compositions, often yield inconsistent retention times for the same As species (AsIII, DMA, MMA, AsV). These discrepancies are largely attributed to differences in sample preparation and extraction protocols, underscoring the necessity for an optimized method that balances speed with reproducibility (Narukawa et al., 2015; Narukawa & Chiba, 2010). Retention times for these species may range from under 3 min (Kang et al., 2016) to over 10 min (Chajduk & Polkowska-Motrenko, 2019), depending on the choice of column and elution strategy. In particular, gradient-based methods often introduce longer equilibration periods, which further prolong analytical runtimes (Kara et al., 2021; Vu et al., 2019). Such variability highlights the absence of a harmonized, rapid, and robust chromatographic method that is readily applicable to routine food safety assessments.

Considering the points outlined earlier, this study aimed to (i) optimize and validate a HPLC-ICP-MS method for arsenic speciation in rice, (ii) assess the distribution of arsenic species including AsIII, and AsV, DMA and MMA in selected white and brown rice samples available in the market, and (iii) estimate the potential human health risks linked to the consumption of rice.

Materials and methods

Instruments

An ICP-MS (NexION 2000 ICP-MS, Perkin Elmer, USA) was employed to determine As species following the separation of As species by HPLC (Flexar FX-20 HPLC, Perkin Elmer, USA). A reversed-phase column (Capcell Pak® 5 µm C18 MG 100 Å, LC Column 150 × 4.6 mm) with a guard column (Capcell Pak®, 3.0 mm ID × 4 mm, 5 µm) was used to separate four As species (AsIII, AsV, MMA and DMA) under isocratic elution, following methods by Subramaniam et al. (2022) and Ernstberger and Neubauer (2015) with modifications to the composition of the mobile phase and the HPLC-ICP-MS operating parameters.

Due to arsenic’s monoisotopic, a collision/reaction cell (CRC) was used to mitigate polyatomic interference from chloride (40Ar35Cl+) at mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) 75. Elevated chloride levels interfere with As detection by forming argon chloride ion (ArCl+) with the same m/z 75 as As. To address this, a dynamic reaction cell (DRC) technique was implemented to oxidize As in an oxygen atmosphere, producing arsenic oxide (AsO+, m/z 91) (Miyashita et al., 2009). The nebulizer gas flow rates were adjusted to ensure that the Ce++ (70)/Ce (140) and CeO (156)/Ce (140) ratios were maintained at or below 0.030 and 0.025, respectively (Montoro-Leal et al., 2021). Table 1 provides the optimized operating conditions for the HPLC-ICP-MS system.

Table 1.

Operating conditions of HPLC-ICP-MS

| ICP-MS operating parameters | HPLC operating parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RF power | 1600 W | Mobile phase composition | 2 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid sodium salt, 2 mM malonic acid, 4 mM tetramethylammonium hydroxide solution |

| Plasma gas flow | 16.0 L/min | Mobile phase pH | 4.13 (± 0.02) |

| Auxiliary (makeup) gas flow | 1.2 L/min | Mobile phase flow rate | 1 mL/min |

| Nebulizer (carrier) gas flow | 0.98 L/min | Injection volume | 20 µL |

| Nebulizer type | Meinhard | Degasser | On |

| Monitored ion | m/z 91 (75As 16O+) | Column temperature | Ambient |

| Acquisition time | 240 s (4 min) | ||

Reagents and standard solutions

Methanol (HPLC grade, Fischer Scientific, Fair Lawn, New Jersey, US), malonic acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for synthesis, 1-octanesulfonic acid sodium salt (≥ 98.0%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), and tetramethylammonium hydroxide solution 25 wt. % in H2O (TMAH) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) were used for the preparation of mobile phase. Nitric acid (HNO3, ~ 65%, for analysis EMSURE® Reag. Ph Eur,ISO) and hydrogen peroxide (H202 30%, R&M Chemicals) of analytical grade were used for sample decomposition of total As. Ammonia hydroxide solution (NH3, 25%, R&M Chemicals) was used for pH adjustment of the mobile phase.

Arsenic species calibration solution concentrations corresponding to 0.25, 0.50, 1.00, 5.00, 10.00, and 20.00 μg/L were prepared from stock standards of AsIII (100 ug/mL in 2% HCI) (Teddington, UK), AsV (100 ug/mL in H2O) (Teddington, UK) and disodium methyl arsonate hydrate (MMA) solution (100 ug/mL in H2O, West Chester, PA, USA). The DMA stock solution (100 μg/mL) was prepared by dissolving cacodylic acid (≥ 99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) in UPW. The certified reference material SRM 1568b Rice Flour, sourced from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST, USA), was used to assess the accuracy of As species quantification and to validate the analytical method.

Quality assurance and quality control

Glassware and plasticware were pre-cleaned by immersion in 10% (v/v) reagent-grade HNO3 for a minimum of 24 h, followed by rinsing with UPW and drying in an oven (Kukusamude et al., 2021). Ultrapure water (UPW) (18.2 M cm; Millipore MilliQ system) was used to prepare all standards, extraction solutions, and mobile phase. Working standard solutions were freshly prepared daily by serial dilutions of stock solutions of each species in the mobile phase at room temperature. A 1 μg/g DMA working standard solution in UPW was kept in tightly sealed polypropylene containers in the dark at 4 °C for up to 3 months.

Rice samples preparation

A total of 30 samples (15 white rice samples and 15 brown rice samples) of various brands and origins were randomly purchased from local superstores in Klang Valley, Selangor, Malaysia. All samples were collected between March and April 2022, thoroughly homogenized, and evenly separated using the quartering technique (FAO/WHO, 2004). White and brown rice samples were finely ground using a high-speed blender, then sifted through a 60-mesh sieve (< 250 μm) and stored in 50 mL centrifuge tubes. This choice of sieve ensures uniform particle size, which enhances sample homogeneity (Castañeda-Figueredo et al., 2022; Welna et al., 2015). The samples in powdered form were dried at 60 °C over a period of two days in a forced convection oven until constant weight (OF-11E, JeioTech, Korea) and kept in a desiccator before analysis (Kukusamude et al., 2021).

Arsenic species digestion and extraction

A heat-enhanced extraction process utilizing an acidic solvent was applied to extract As species from the rice samples, adapted from the PerkinElmer application note with slight modifications (Kobayashi & Shikino, 2014; Park & Ma, 2014). Approximately 1 g of dried rice samples was weighed accurately into digestion tubes, followed by the addition of 10 mL of 0.2% (v/v) HNO3 in two separate portions of 5 mL. The sample was then mixed using a vortex mixer to ensure homogeneity. The mixture was heated in a block digesting system (Shimaden SRS12A) at 90 °C for 1 h and 30 min. Once cooled to room temperature, the extracts were subjected to centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 30 min to separate the supernatant.

Before instrumental analysis, 9 mL of mobile phase was added to 1 mL of the supernatant. A mixture of 0.432 g of 1-octanesulfonic acid sodium salt, 0.208 g of malonic acid, and 0.365 g of TMAH, all dissolved in 1 L of UPW was used as the mobile phase. The mobile phase was vacuum degassed and filtered through a 0.22 μm hydrophilic PTFE membrane filter (HmbG) before use. While the resulting solution was passed through a 0.45 μm nylon filter (Agilent Technologies, China), the first millilitre of the filtered solution was discarded to avoid contamination, and the remaining filtrate was transferred into a 2 mL vial before HPLC-ICP-MS analysis.

Analytical figures of merit

Figures of merit are key validation parameters in analytical chemistry that assess the suitability of an analytical method. The most critical parameters include accuracy, linearity, limit of detection, limit of quantification, and precision. Prior to method validation, these parameters must be established, along with the acceptable limits for reliable results (Hair et al., 2021). All parameters for validation were based on the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines.

Linearity and calibration range

A six-point weighted calibration curve (1/x2) was used for instrument calibration, allowing the determination of specific As species concentrations from their integrated peak areas. Instead of constraining the y-intercept to zero, the intercept was set to be ignored. Calibration standards containing mixed As species were prepared at concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 20.0 µg/L, serving as reference points. The correlation coefficient (R2) was used to evaluate the linearity of the calibration curve, with values approaching one indicating strong linearity and reliable quantification (Hair et al., 2021).

Accuracy

Accuracy was assessed using spiked SRM 1568b rice flour samples, which were selected as a suitable matrix for preliminary spike recovery assessment due to their rice-based composition and similarity to the test samples, despite their high cost and availability for this purpose. This approach helped reduce potential matrix mismatch during method evaluation. A similar use of SRM 1568b and CRM BCR-191 for spike recovery in brown rice analysis has been reported previously (Shraim et al., 2022). Fortification was performed by adding a mixed As standard (200 µg/L) to rice powder (1 g) to achieve final spiking levels of 30, 80, and 150 µg/kg. The standards were introduced into the sample before extraction with 10 mL of 0.2% (v/v) HNO₃, and the samples were not dried post-spiking. Acceptable recovery limits for AsV, MMA, AsIII, and DMA were defined as 70% to 120%. Recovery was assessed in two ways: (i) the certified reference material recovery was calculated by comparing the measured concentration of each As species in SRM 1568b to its certified value, while (ii) spike recovery was determined by spiking known concentrations of As species into representative samples and calculating the percentage recovered after extraction and analysis. Spike recoveries were calculated using Eq. 1, which is based on m/m units (Kubachka et al., 2012).

| 1 |

where; Cx+s is the concentration measured in spiked sample (μg/kg); Cx is the concentration measured in unspiked sample (μg/kg); Cs is the concentration of the spiking solution (μg/kg); Ms is the mass of spiking solution added to sample portion (g); Mx is the mass of sample used (g).

Precision

Instrumental repeatability and reproducibility were conducted using intra-day and inter-day tests respectively. Repeatability was assessed by computing the relative standard deviation (RSD) from multiple replicate measurements (n = 10) of 0.25 µg/L mixed As standards within the same day. The reproducibility was measured by calculating the RSD of repeated measurements (n = 10) of 0.25 µg/L mixed As standards on 10 consecutive days. An acceptable RSD is less than or equal to ± 20% (Schoenau et al., 2019).

Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ)

The limit of detection (LOD) is defined as the minimum concentration at which an analyte can be detected above the baseline noise, while the limit of quantification (LOQ) is the minimum level at which it can be quantified with precision and accuracy. The LOD is always lower than the LOQ (Schoenau et al., 2019). The LOD (Eq. 2) and LOQ (Eq. 3) were determined based on the standard deviation of the response and the calibration slope.

| 2 |

| 3 |

where σ is the standard deviation of response and S is the slope of the calibration curve.

If the analyte concentration is below the LOD, it is not reliably detected and is typically reported as "not detected (ND)" or " < LOD" since the signal is indistinguishable from background noise, whereas if the response falls between the LOD and LOQ, the analyte is detected but cannot be quantified with accuracy and is often reported as "estimated" or "trace." On the other hand, if the response exceeds the LOQ, the analyte’s concentration can be measured with confidence and reported as a precise value (Schoenau et al., 2019).

Health risk assessment

Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks posed by As were assessed according to guidelines set by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA, 2020). Two key metrics were used to evaluate these risks: the estimated daily intake (EDI) and the target hazard quotient (THQ) for the non-carcinogenic risk, and the incremental lifetime cancer risk (ILCR) for carcinogenic risks.

Estimated daily intake (EDI)

The EDI for iAs was estimated based on the average concentrations of iAs in rice samples (Eq. 4).

| 4 |

where; EDI is the estimated daily intake (mg/kg bw-day); EF is the exposure frequency (365 days/year) (USEPA, 2008); ED is the exposure duration (30 years for adults) (USEPA, 2008); IR is the ingestion rate of rice (0.208 kg per person/day) (OECD/FAO 2024); C is the concentration of iAs in rice (mg/kg); BW is the average body weight (70 kg for adults and 20 kg for children) (USEPA, 2008; Praveena & Omar, 2017); AT is the average time (days) (30 years × 365 days for non-carcinogenic effects, 70 years × 365 days for carcinogenic effects) (USEPA, 2008).

Target hazard quotient (THQ)

The THQ (Eq. 5) was calculated following the methodology of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). The RfD for As is 6 × 10−5 mg/kg bw-day (USEPA, 2025).

| 5 |

where, EDI is the estimated daily intake of rice (mg/kg bw-day) and the RfD is the oral reference dose (mg/kg bw-day).

Incremental lifetime cancer risk (ILCR)

The carcinogenic risk of As was calculated using the Incremental Lifetime Cancer Risk (ILCR) as per Eq. (6) (Sharafi et al., 2019).

| 6 |

where, EDI is the estimated daily intake of rice averaged over 70 years (mg/kg bw-day) and CSF is the cancer slope factor (mg/kg bw-day)−1. For As, the oral CSF is 32 (mg/kg bw-day)−1 (USEPA, 2025).

Results and discussion

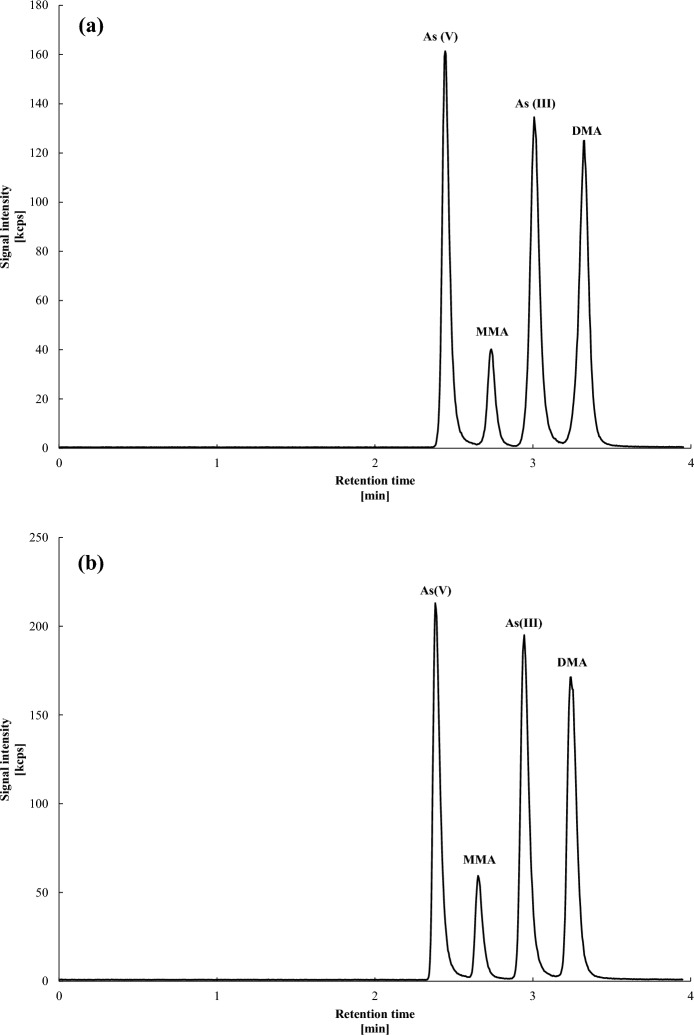

Optimization of HPLC-ICP-MS method for the separation of arsenic species

Optimization of mobile phase pH

The retention time of As species is a critical parameter for optimizing the separation efficiency of HPLC-ICP-MS. The pH of the mobile phase is an important factor that influences the retention of As species (Ma et al., 2016a, 2016b). The retention times of all four As species increased slightly as the pH increased from 4.0 to 4.4 (Fig. 2). Among the species, DMA consistently had the highest retention time, approximately 3 min while AsV displayed the lowest retention time of approximately 2 min. The increase in retention time with rising pH is due to changes in the ionization state of As species, which affect their interaction with both the ion-pairing reagent and the stationary phase. At lower pH, As species are more protonated and interact less with the hydrophobic stationary phase. As pH increases, deprotonation enhances their ability to form stable ion pairs, increasing their affinity for the stationary phase and leading to longer retention times.

Fig. 2.

Effect of pH on the retention time of different arsenic species in a mixed standard solution (10 µg/L); column C18 reversed-phase column (150 mm); flow rate: 1.2 mL/min

Previous studies have demonstrated that the interaction between As species and the stationary phase is influenced by pH-dependent speciation, which affects their retention characteristics (Jayakody et al., 2024; Kara et al., 2021; Lau et al., 2025; Narukawa et al., 2017). At a mobile phase of approximately pH 4, the elution order of As species in reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) is governed by their pKa values, polarity, hydrophobicity, and interactions with the hydrophobic C18 stationary phase, further influenced by ion-pair reagents (Hu et al., 2019). At this pH, AsV existed predominantly in its anionic form (-1 charge) due to the mobile phase pH being higher than its pKa (≈4 > 2.19), while AsIII remained neutral since the pH was lower than its pKa (≈4 < 9.23). Moreover, MMA (pKa = 4.1) existed in a partially ionized state (0 to -1), and DMA (pKa = 6.2) was primarily neutral. In reversed-phase chromatography, the stationary phase retains nonpolar compounds more strongly through hydrophobic interactions, causing As species with methyl groups (MMA and DMA) to elute later. Arsenate (AsV), being the most polar and negatively charged, interacted least with the hydrophobic stationary phase and eluted first. On the other hand, MMA, with one methyl group and lower polarity than AsV, showed moderate hydrophobic interactions and eluted next. Arsenite, though neutral, had a higher polarity than DMA, resulting in weaker retention and earlier elution. Lastly, DMA bearing two methyl groups and exhibiting the highest hydrophobicity among the species, was retained most strongly and eluted last. Ion-pair reagents like 1-octanesulfonic acid and TMAH are known to reduce the retention times of charged species by forming neutral ion-pair complexes. In line with this principle, AsV eluted first due to its high polarity and weak hydrophobic interactions in its anionic form, consistent with the effect of ion-pairing reagents.

The elution order of As species observed in this study aligns with the findings of Subramaniam et al. (2022), likely due to the use of nearly identical chromatographic parameters. However, Kaňa et al. (2020), Narukawa et al. (2015), and Suzuki et al. (2022) reported a different elution order (AsV, AsIII, MMA, and DMA) despite employing a comparable mobile phase composition. This discrepancy can be attributed to the use of a pH below 3.0. Interestingly, Narukawa et al. (2015) observed that the retention times of AsIII and AsV were relatively unaffected by pH, a finding that is consistent with the present study, particularly at pH levels beyond 4.2 (Fig. 3). Similarly, the decrease in retention times for MMA and DMA with increasing pH from 4.2 to 4.4, as reported by Narukawa et al. (2015), was consistent with the present findings.

Fig. 3.

Impact of small variations in the pH on the separation of arsenic species: a pH 4.1, b pH 4.2, c pH 4.3, d pH 4.4, with a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min

Optimization of mobile phase flow rate

The flow rate is another important factor influencing the retention of As species (Ma et al., 2016a, 2016b). This parameter allows for quick and effective separation of the inorganic and organic As species (Narukawa et al., 2017). By tuning the kinetic parameters like the mobile phase flow rate, the separation factor is increased effectively and the peak spacing is optimized (Niezen et al., 2024). The separation of As species at pH 4.1 and 4.3 looks similar visually at flow rate 1.2 mL/min but at pH 4.3 the baseline separation between AsIII and DMA was slightly lifted [Fig. 3(a) and (c)]. To achieve better peak separation, the flow rate was slightly reduced to 1.0 mL/min (Fig. 4). At pH 4.1, the retention times for AsV (2.44 min), MMA (2.73 min), AsIII (3.01 min) and DMA (3.32 min) were more evenly spaced compared to those at pH 4.3 [AsV (2.38 min), MMA (2.65 min), AsIII (2.95 min) and DMA (3.24 min)], reducing the risk of co-elution, particularly with slight pH variations. This is further supported by the observations at pH 4.4 where AsIII and DMA co-eluted [Fig. 3(d)].

Fig. 4.

Impact of flow rate adjustments (1.0 mL/min) on the separation of arsenic species at different pH levels: a pH 4.1 and b pH 4

The effectiveness of separation is evaluated based on the resolution factor (Rs) between consecutive peaks (Song & Wang, 2003). Therefore, the Rs values were also calculated as outlined in the study by Xiao et al. (2024). Overall, the Rs was greater than 1.5 for all tested conditions, confirming effective peak separation (Table 2). However, variations in Rs were observed with changes in the pH and flow rate. Based on the %RSD values, pH 4.3 at both flow rates (1.0 mL/min and 1.2 mL/min) exhibited higher variability compared to pH 4.1 at the same flow rates. Since %RSD represents the precision of an outcome, with lower values indicating better reproducibility, pH 4.3 at both flow rates was deemed unsuitable (Ng et al., 2020). Between the two flow rates tested at pH 4.1, the Rs remained relatively consistent across concentrations. However, the %RSD for the Rs between MMA and AsIII was notably higher at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min, suggesting lower precision. Based on these findings, a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at pH 4.1 was selected as the optimum condition.

Table 2.

Resolution factors (Rs) for different pH and flow rate (mL/min) combinations at various standard concentrations

| pH/flow rate (mL/min) | Resolution factor (Rs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration of mixed standard (µg/L) | AsV-MMA | MMA-AsIII | AsIII-DMA | |

| 4.1/1.0 | 5 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| 10 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 4.5 | |

| 20 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 4.5 | |

| %RSD | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.3 | |

| 4.1/1.2 | 5 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 5.1 |

| 10 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 5.2 | |

| 20 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 5.0 | |

| %RSD | 1.0 | 4.1 | 2.0 | |

| 4.3/1.0 | 5 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.7 |

| 10 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.4 | |

| 20 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.5 | |

| %RSD | 4.0 | 1.1 | 3.9 | |

| 4.3/1.2 | 5 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.3 |

| 10 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.2 | |

| 20 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.1 | |

| %RSD | 5.3 | 1.7 | 1.8 | |

Optimization of solid/liquid ratio and duration of extraction

The extraction method employed in this study was optimized based on two previously developed methods (Narukawa et al., 2017; Subramaniam et al., 2022). Previous studies indicate that several factors influenced the effective extraction of As species, including extraction temperature, shaking time, rotation speed, and solvent volume (Ma et al., 2016a, 2016b; Nguyen et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2015; Tibon et al., 2021). Notably, different As species exhibit unique sensitivities to these parameters, influencing their extraction efficiencies.

For instance, Ma et al. (2017) found that both extraction temperature and shaking time positively influenced the extraction of AsIII, whereas for AsV and DMA, only extraction temperature had a significant effect. In contrast, rotation speed and solvent volume were deemed insignificant. Another study by Sun et al. (2015) highlighted that extraction temperature, extraction time, solvent volume, and extractant concentration impacted AsIII extraction, whereas AsV was affected by extraction temperature, extraction time, and extractant concentration. Similarly, Nguyen et al. (2021) investigated the effects of extraction temperature, extraction time, and HNO3 concentration, reporting that temperature and HNO3 concentration influenced all As species. However, only AsIII, AsV, and MMA were positively affected by extraction time. Additionally, an increase in HNO3 concentration, extraction time, and temperature was reported to degrade DMA, leading to the overestimation of iAs species.

A separate investigation evaluated various factors influencing extraction efficiency, such as sample mass, solvent composition and volume, addition of oxidizing agents, thermal conditions, duration, and ultrasonic assistance (Tibon et al., 2021). However, only the type of extraction solvent and extraction temperature were found to significantly impact As species extraction. Across all studies, extraction temperature consistently played a crucial role in the efficiency of As species extraction. Despite this, in the present study, the extraction temperature was not optimized and was maintained at 90 °C. This decision was based on equipment limitations and safety considerations, as temperatures exceeding this threshold would have necessitated the use of an oil bath (Tibon et al., 2021). Instead, extraction time was selected as the optimization parameter.

According to Subramaniam et al. (2022), the highest concentration of extracted AsIII, AsV, and DMA was achieved at 60 min, whereas MMA required 120 min. However, Sun et al. (2015) reported that extending the extraction duration to 120 min for AsIII led to interconversion between As species. To prevent this, extraction durations ranging from 60 to 120 min were tested in this study, with increments of 30 min (Tibon et al., 2021) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Recovery of arsenic species (iAs, MMA, DMA) at different extraction durations and solid–liquid ratios. The solid–liquid ratios tested were 0.1 g SRM/10 mL HNO3 and 1 g SRM/10 mL HNO3, with extraction durations of 60, 90, and 120 min. The red dashed lines represent the acceptable recovery threshold range (70–120%). MMA recovery exceeded the acceptable range across all conditions

In addition to extraction time, the amount of solute used in the extraction process plays a crucial role in determining analytical accuracy and precision. A previous study has indicated that the mass of the sample can influence extraction efficiency, as higher sample weights may introduce matrix effects or lead to incomplete extraction (Gil-Martin et al., 2022).

To determine the optimal sample weight, extractions were performed using both 0.1 g and 1.0 g of rice samples. The efficiency of each extraction condition was evaluated using SRM 1568b with recovery rates serving as performance indicators. An ideal extraction condition was defined as one that yielded recoveries within the range of 70–120% with minimal RSD values.

The recovery of iAs, MMA, and DMA varied with extraction duration (60, 90, and 120 min). The recovery of iAs ranged between 137 and 145% for 0.1 g/10 mL and 109% to 116% for 1.0 g/10 mL, with only the 1.0 g/10 mL solid/liquid ratio falling within the acceptable recovery range (70–120%). Similarly, DMA exhibited a slight increase in recovery over time, with values ranging from 92 to 98% (0.1 g/10 mL) and 101% to 111% (1.0 g/10 mL), indicating stable extraction efficiency across all durations. Conversely, the recovery across different extraction times for MMA, was as high as 453% at 60 min (0.1 g/10 mL) and 405% at 120 min (1.0 g/10 mL), exceeding the acceptable range.

The Mann–Whitney U test revealed a statistically significant effect of the solid–liquid ratio on SRM recovery for iAs (p < 0.05). Despite this, the recoveries of SRM for iAs in 0.1 g/10 mL exceeded the acceptable range (70–120%) (Fig. 5). The differences in iAs recovery can be attributed to the instability of AsIII-glutathione complexes in rice grains (Limmer & Seyfferth, 2022). According to Limmer and Seyfferth (2022), AsIII readily forms complexes with glutathione and is sequestered in vacuoles, however, these complexes degrade under routine extraction conditions, potentially leading to variability in measured iAs concentrations. In contrast, no significant difference in DMA recoveries between the solid–liquid ratios was observed (p > 0.05). The lack of significant variation may be attributed to DMA’s higher mobility and its weaker interactions with glutathione, which reduce its tendency to form stable intracellular complexes (Limmer & Seyfferth., 2022).

Given these findings, 0.1 g/10 mL is not recommended for iAs quantification due to its excessive recovery, which could lead to inaccurate estimations. Instead, 1.0 g/10 mL should be used to ensure recovery within the acceptable range, thereby improving the accuracy of As speciation analysis. However, for DMA analysis, 0.1 g/10 mL remains a viable option to minimize sample and reagent consumption without compromising data reliability especially when working with limited or expensive samples.

While MMA is typically undetected or below detection limits in previous studies (Islam et al., 2017b; Jitaru et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2023), the present study recorded higher MMA recoveries. This discrepancy may suggest potential issues such as matrix effects or co-extraction of interfering compounds (Wieczorek et al., 2024). Thus, the inclusion of an internal standard may be necessary to enhance accuracy and precision (Son et al., 2019).

No significant differences in SRM recovery were observed for both iAs and DMA across the tested extraction durations (p > 0.05), indicating that extraction time alone did not have a notable impact on their recoveries. A previous study reported that extraction time significantly influenced iAs recovery but had no effect on DMA (Nguyen et al., 2021). This was attributed to DMA degradation into iAs under elevated extraction conditions, including prolonged extraction time, high temperature, and strong acid concentration. While the findings for DMA in this study align with previous research, the lack of a significant effect on iAs recovery suggests that extraction time alone may not be a key factor in its variability under the tested conditions (Ma et al., 2016a, 2016b; Nguyen et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2015; Tibon et al., 2021). Given this, a Plackett–Burman design could be employed to screen for the most influential factors affecting recovery, providing a systematic approach for future optimization.

Method validation

Linearity and calibration range

In this study, a six-point calibration curve was constructed that ranged between 0.25, 0.50, 1.00, 5.00, 10.00 and 20.00 µg/L, demonstrating strong linearity with a correlation coefficient (R2) ≥ 0.999 for all analytes (Table 3). The established range ensures reliable quantification of As species within the expected sample concentration levels.

Table 3.

Calibration parameters for arsenic species determination

| Analyte | Calibration range (µg/L) | R2 | y-intercept | Slope of regression line (cps.s/µg.L−1) | Residual sum of squares (cps.s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AsV | 0.25 – 20.00 | 0.999 | 170 | 5.59 × 104 | 6.56 × 10–7 |

| MMA | 0.25 – 20.00 | 0.999 | 589 | 1.54 × 104 | 4.86 × 10–6 |

| AsIII | 0.25 – 20.00 | 0.999 | 199 | 5.64 × 104 | 3.36 × 10–7 |

| DMA | 0.25 – 20.00 | 0.999 | 125 | 5.45 × 104 | 3.55 × 10–7 |

Accuracy

The accuracy of the method was assessed by spiking the SRM 1568b with 3 µg/L, 8 µg/L, and 15 µg/L of each As species. The recovery values ranged from 87.8% to 108.6% for the 3 µg/L spiking level, from 85.8% to 99.3% for the 8 µg/L level, and from 74.5% to 93.8% for the 15 µg/L level (Table 4). All recoveries fell within the acceptable range of 70% to 120%, as recommended by the ICH Harmonised Tripartite (2005) guideline.

Table 4.

Percent recovery of arsenic species (AsV, MMA, AsIII, DMA) in spiked samples

| Spiking concentration (µg/L) | Analyte | Unspiked sample concentration (µg/kg) | Spiked sample concentration (µg/kg) |

Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | AsV | 38.6 ± 1.4 | 67.3 ± 1.3 | 95.7 ± 6.4 |

| MMA | 29.0 ± 2.5 | 55.3 ± 2.3 | 87.7 ± 11.3 | |

| AsIII | 53.4 ± 0.6 | 86.0 ± 0.3 | 108.7 ± 2.2 | |

| DMA | 162.9 ± 2.6 | 193.7 ± 0.8 | 102.7 ± 9.1 | |

| 8 | AsV | 38.6 ± 1.4 | 113.8 ± 1.8 | 94.0 ± 2.9 |

| MMA | 29.0 ± 2.5 | 97.5 ± 2.0 | 85.6 ± 4.0 | |

| AsIII | 53.4 ± 0.6 | 132.8 ± 1.5 | 99.3 ± 2.0 | |

| DMA | 162.9 ± 2.6 | 238.2 ± 2.5 | 94.1 ± 4.5 | |

| 15 | AsV | 38.6 ± 1.4 | 168.7 ± 1.3 | 86.7 ± 1.3 |

| MMA | 29.0 ± 2.5 | 140.8 ± 1.8 | 74.5 ± 2.1 | |

| AsIII | 53.4 ± 0.6 | 194.2 ± 2.8 | 93.9 ± 1.9 | |

| DMA | 162.9 ± 2.6 | 290.6 ± 3.3 | 85.1 ± 2.8 |

At the 3 µg/L level, recovery was generally higher (87.8% to 108.6%). Arsenite had the highest recovery at this level (108.6%), suggesting strong extraction efficiency at lower concentrations. At 8 and 15 µg/L, a slight decrease compared to the 3 µg/L level was observed.

Precision

The standard deviation (SD), %RSD, and confidence interval of all As species were reported, whereby the %RSD was below 20%, showing excellent precision (Table 5).

Table 5.

Repeatability and reproducibility of arsenic species in this study

| Analyte | Repeatability | Reproducibility | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD (µg/L) | RSD (%) | CI* | SD (µg/L) |

RSD (%) | CI* | |||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| AsV | 0.231 | 0.752 | 0.142 | 0.449 | 0.019 | 7.28 | 0.246 | 0.505 |

| MMA | 0.235 | 0.753 | 0.144 | 0.455 | 0.028 | 10.92 | 0.232 | 0.484 |

| AsIII | 0.241 | 0.797 | 0.130 | 0.433 | 0.022 | 8.32 | 0.245 | 0.506 |

| DMA | 0.239 | 0.743 | 0.151 | 0.472 | 0.020 | 7.55 | 0.253 | 0.520 |

*CI values represent the margin of error (95% confidence interval) for the measured concentration

Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ)

The LOD and LOQ values ranged between 0.114 to 0.398 µg/kg and 0.345 to 1.207 µg/kg (Table 6). The LOD values in this study were comparable to a study from Vietnam and Taiwan for AsV (0.20 µg/kg, 0.14 µg/kg) and AsIII (0.10 µg/kg, 0.25 µg/kg) but is lower compared to the LOD for AsV (0.90 µg/kg) and AsIII (0.50 µg/kg) from China (Chen et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2016a, 2016b; Nguyen et al., 2021). The LOD and LOQ in DMA for other studies were higher but lower than the value recorded in Taiwan (0.08 µg/kg).

Table 6.

LOD and LOQ of analytical method for the determination of arsenic species in rice

| Analyte | Response (cps) | Slope (cps/µg/L) | LOD (µg/kg) | LOQ (µg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AsV | 11.8 | 2.75 × 104 | 0.142 | 0.430 |

| MMA | 11.8 | 9.79 × 103 | 0.398 | 1.207 |

| AsIII | 11.8 | 2.84 × 104 | 0.137 | 0.416 |

| DMA | 11.8 | 3.43 × 104 | 0.114 | 0.345 |

Rice analysis

Arsenic speciation in rice is crucial for assessing potential health risks, as different As species exhibit varying levels of toxicity. In this study, an optimized and validated extraction method was applied to determine As species in white and brown rice samples collected from local supermarkets in Selangor, Malaysia. While the method successfully quantified AsIII, AsV, and DMA, MMA was excluded from the final analysis due to its poor recovery, which could compromise data reliability. This exclusion is consistent with previous findings, as MMA is often present in rice at negligible levels or below detection limits (Jitaru et al., 2016; Naito et al., 2015; Reid et al., 2021; Sarwar et al., 2021). Furthermore, since MMA is not a significant contributor to health risk assessments, its omission does not affect the overall evaluation of As exposure from rice consumption (Arcella et al., 2021).

In both brown and white rice samples, the major As species was AsIII followed by DMA and AsV (Fig. 6). Lee et al. (2018) and Nookabkaew et al. (2013) observed similar distribution patterns in the rice samples.

Fig. 6.

Concentration of arsenic species (AsIII, AsV and DMA) in white and brown rice (mg/kg) collected in this study

The mean AsIII concentration in brown rice samples was 0.184 ± 0.015 mg/kg, ranging from 0.082 mg/kg to 0.336 mg/kg. In comparison, white rice had a lower mean concentration of 0.120 ± 0.004 mg/kg, with values ranging from 0.092 mg/kg to 0.148 mg/kg. Arsenate concentrations followed a similar trend, with brown rice containing 0.015 ± 0.004 mg/kg (range: 0.005–0.071 mg/kg) and white rice having a mean of 0.008 ± 0.001 mg/kg (range: 0.003–0.012 mg/kg). The reason for higher AsIII concentration in all rice types could be attributed to the anoxic paddy field soil conditions where AsIII prevails (Sarwar et al., 2021).

The average iAs concentration in brown rice and white rice were 0.199 mg/kg and 0.128 mg/kg, respectively. This observation is higher than those reported by Nookabkaew et al. (2013), Sarwar et al. (2021) and Šlejkovec et al. (2021) for Thailand, Pakistan and Slovenia, respectively. As mentioned before, the mobility of AsIII in flooded paddy fields is higher due to the absence of FeIII oxides, which typically act as adsorption sites for AsV. Under anaerobic conditions, FeIII is reduced to FeII, leading to the dissolution of iron oxides and the subsequent release of adsorbed AsV into the soil solution. This enhances the availability and mobility of AsIII, which is more soluble and less strongly bound to soil particles compared to AsV (León Ninin et al., 2024). Additionally, interactions with other elements such as selenium can influence As uptake in rice. Low selenium concentrations, for example, may increase As content in rice, as Se competes with As for uptake pathways (Pokhrel et al., 2020). Overall, the iAs concentration in brown rice was, on average, 56.8% higher than in white rice, which may be due to its retention in the bran layer (Weber et al., 2021; Yim et al., 2017). Research indicates that iAs predominantly localizes in the grain’s outer layers due to unloading mechanisms, whereas DMA is more prevalent within the starchy core (Lee et al., 2018).

Across all rice samples, iAs levels ranged from 0.096 mg/kg to 0.352 mg/kg, with several samples exceeding regulatory limits with brown rice having higher iAs compared to white rice (p < 0.05). Specifically, all rice samples except for MR 12 surpassed the permissible iAs limit set for infant food production (Fig. 7). Out of the 15 brown rice samples analyzed, two exceeded the European Commission (EC) limit for brown rice (0.250 mg/kg), while two white rice samples surpassed the recently revised EC threshold for white rice (0.150 mg/kg). These limits were chosen as reference points because they were updated in 2023, based on findings that rice, grains, and their derived products are the primary contributors to dietary exposure to iAs, particularly among infants and children (European Commission, 2023). The Malaysian Food Regulation 1985 was not used as a benchmark because it only specifies a limit of 1.000 mg/kg for total As without distinguishing between inorganic and organic species. Since total As includes both toxic and non-toxic forms, using this regulation as a reference could lead to an underestimation of the actual health risk associated with iAs exposure.

Fig. 7.

Inorganic arsenic concentration across all rice samples analysed in this study, compared with the maximum allowable limits for inorganic arsenic: 0.01 mg/kg for rice intended for infant food and snacks, 0.15 mg/kg for polished (white) rice, and 0.25 mg/kg for husked (brown) rice

Interestingly, the two samples with the highest iAs concentrations, MR 14 (white rice) and MR 27 (brown rice), were labelled as organically cultivated. Previous findings suggest that an increase in organic matter in soil can enhance microbial activity, leading to a more reduced environment (Marzouk et al., 2025). Under such conditions, Fe-oxyhydroxides undergo reductive dissolution, subsequently increasing As mobility and accumulation in rice grains (Zhang et al., 2024). In contrast, the other two high-As samples, MR 29 (from Malaysia) and MR 10 (of unknown origin), appeared to be conventionally cultivated without any indication of organic amendments, based on their packaging information. The elevated iAs levels in MR 29 may be attributed to several environmental and anthropogenic factors. Naturally occurring As deposits from the weathering of arsenopyrite have been documented in Malaysia, with surface water As concentrations exceeding 100 µg/L and soil levels surpassing 5 mg/kg. Nonetheless, human-driven actions like mineral extraction and the release of industrial waste have further intensified As pollution (Ahmed et al., 2021; Sakai et al., 2017). Additionally, the extensive use of pesticides in rice cultivation may play a role in As accumulation through airborne deposits and/or contaminated irrigation water (Elfikrie et al., 2020; Hamsan et al., 2017). Moreover, Malaysian paddy soils are acidic due to long-term soil acidification, which enhances As bioavailability and facilitates its uptake by rice plants (Signes-Pastor et al., 2007; Tanaka et al., 2021).

Despite this, another white rice sample (MR 12) from Malaysia, which was not specifically labelled as baby food, had an iAs concentration of 0.096 mg/kg that was within the safety threshold for infant food production. This brand also produces rice varieties intended for baby consumption, suggesting that adherence to international quality standards may have been considered in its cultivation and processing, subsequently leading to the low iAs content.

In conclusion, the range of iAs concentrations observed in this study falls within but does not exceed the broader range reported in a past study from Italy (0.025 mg/kg to 0.471 mg/kg, n = 37) (Jitaru et al., 2016) but exceeded the range reported in China (0.049 mg/kg to 0.211 mg/kg, n = 43) (Ma et al., 2016a, 2016b) and Pakistan (0.035 mg/kg to 0.021 mg/kg, n = 438) (Sarwar et al., 2021) probably due to their higher sample sizes. Nevertheless, the iAs content in this study was within the global average of 0.002 mg/kg to 0.399 mg/kg (Carey et al., 2020).

Health risk

Four scenarios were considered for the human health risk assessment of rice As (Table 7). The first scenario was based on per capita consumption rate of rice in Malaysia (0.208 kg/day) (OECD/FAO, 2024). Corresponding to the newly established CSF of 32 mg/kg bw−1 day−1 (USEPA, 2025), the ILCR for Malaysian adults and children were 1.22 × 10–2 (i.e., 1.22 cases per 100 of the adult population) and 4.27 × 10−2 (4.27 cases per 100 of the child population), respectively, for consuming white rice. For brown rice, the ILCR for Malaysian adults and children were 1.91 × 10–2 (i.e., 1.91 cases per 100 of adult population) and 6.69 × 10−2 (6.69 cases per 100 of children population), respectively. The corresponding THQs due to white rice consumption were 6.35 and 22.21, respectively. For brown rice exposure, the THQs were 9.95 and 34.83, respectively. The THQ and ILCR values were all > 1 and 1 × 10−4, respectively, signifying potential adverse health risk due to iAs exposure through rice samples in this study. In comparison with the new RfD of 6 × 10–5 mg/kg bw-day, the percentage increase in risk sensitivity relative to the previous threshold 3 × 10–4 mg/kg bw-day was found to be increased by 400%. The risk of rice consumption due to iAs exposure is about 20 times higher than the previous CSF of 1.5 mg/kg bw−1 day−1 in comparison to the revised CSF of 32 mg/kg bw−1 day−1 (USEPA, 2025).

Table 7.

Comparison of Incremental Lifetime Cancer Risk (ILCR) and Target Hazard Quotient (THQ) using previous and revised toxicological reference values by USEPA (2025) under different scenarios

| Rice type | Ingestion rate (IR) (kg/day) |

Concentration (C) of iAs in rice (mg/kg) | Body weight (BW) (kg) | EDI (mg/kg bw-day) |

THQ (using previous RfD 3 × 10–4 mg/kg bw-day) | THQ (using revised RfD 6 × 10–5 mg/kg bw-day) | ILCR [using previous CSF 1.5 (mg/kg bw-day)−1] | ILCR [using revised CSF 32 (mg/kg bw-day)−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: EDI, THQ, and ILCR were calculated based on the IR of Malaysian adults and children | ||||||||

| White ricea | 0.208 | 0.128 | 70 | 3.81 × 10–4 | 1.27 | 6.35 | 5.71 × 10–4 | 1.22 × 10–2 |

| White riceb | 0.208 | 0.128 | 20 | 1.33 × 10–3 | 4.44 | 22.21 | 2.00 × 10–3 | 4.27 × 10–2 |

| Brown ricea | 0.208 | 0.201 | 70 | 5.97 × 10–4 | 1.99 | 9.95 | 8.95 × 10–4 | 1.91 × 10–2 |

| Brown riceb | 0.208 | 0.201 | 20 | 2.09 × 10–3 | 6.96 | 34.82 | 3.31 × 10–3 | 6.69 × 10–2 |

| Scenario 2: EDI, THQ, and ILCR were calculated based on the IR of the UK population for both adults and children (0.015 kg/day) (Menon et al., 2020) | ||||||||

| White ricea | 0.015 | 0.128 | 70 | 2.75 × 10–5 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 4.12 × 10–5 | 8.79 × 10–4 |

| White riceb | 0.015 | 0.128 | 20 | 9.61 × 10–5 | 0.32 | 1.60 | 1.44 × 10–4 | 3.08 × 10–3 |

| Brown ricea | 0.015 | 0.201 | 70 | 4.30 × 10–5 | 0.14 | 0.72 | 6.46 × 10–5 | 1.38 × 10–3 |

| Brown riceb | 0.015 | 0.201 | 20 | 1.51 × 10–4 | 0.50 | 2.51 | 2.26 × 10–4 | 4.82 × 10–3 |

| Scenario 3a) Maximum IR to avoid ILCR (using CSF = 1.5 (mg/kg bw-day)−1 to calculate EDI) | ||||||||

| White ricea | 0.036 | 0.128 | 70 | 6.67 × 10–5 | 0.22 | 1.11 | 1.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 × 10–4 |

| White riceb | 0.010 | 0.128 | 20 | 6.67 × 10–5 | 0.22 | 1.11 | 1.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 × 10–4 |

| Brown ricea | 0.023 | 0.201 | 70 | 6.67 × 10–5 | 0.22 | 1.11 | 1.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 × 10–4 |

| Brown riceb | 0.007 | 0.201 | 20 | 6.67 × 10–5 | 0.22 | 1.11 | 1.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 × 10–4 |

| Scenario 3b) Maximum IR to avoid ILCR (using CSF = 32 (mg/kg bw-day)−1 to calculate EDI) | ||||||||

| White ricea | 0.0017 | 0.128 | 70 | 3.13 × 10–6 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 1.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 × 10–4 |

| White riceb | 0.0005 | 0.128 | 20 | 3.13 × 10–6 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 1.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 × 10–4 |

| Brown ricea | 0.0011 | 0.201 | 70 | 3.13 × 10–6 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 1.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 × 10–4 |

| Brown riceb | 0.0003 | 0.201 | 20 | 3.13 × 10–6 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 1.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 × 10–4 |

| Scenario 4a) Maximum IR based on THQ (using RfD = 3 × 10–4 mg/kg bw-day to calculate EDI) | ||||||||

| White ricea | 0.164 | 0.128 | 70 | 3.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.50 × 10–4 | 9.60 × 10–3 |

| White riceb | 0.047 | 0.128 | 20 | 3.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.50 × 10–4 | 9.60 × 10–3 |

| Brown ricea | 0.105 | 0.201 | 70 | 3.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.50 × 10–4 | 9.60 × 10–3 |

| Brown riceb | 0.030 | 0.201 | 20 | 3.00 × 10–4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.50 × 10–4 | 9.60 × 10–3 |

| Scenario 4b) Maximum IR based on THQ (using RfD = 6 × 10–5 mg/kg bw-day to calculate EDI) | ||||||||

| White ricea | 0.033 | 0.128 | 70 | 6.00 × 10–5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.00 × 10–5 | 1.92 × 10–3 |

| White riceb | 0.009 | 0.128 | 20 | 6.00 × 10–5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.00 × 10–5 | 1.92 × 10–3 |

| Brown ricea | 0.021 | 0.201 | 70 | 6.00 × 10–5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.00 × 10–5 | 1.92 × 10–3 |

| Brown riceb | 0.006 | 0.201 | 20 | 6.00 × 10–5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.00 × 10–5 | 1.92 × 10–3 |

aEstimation based on the average adult’s body weight (USEPA, 2008)

bScenario based on average children’s body weight (Praveena & Omar, 2017)

To represent a lower rice consumption scenario, the second case applied the average per capita rice intake of the UK population (0.015 kg/day), reflecting dietary patterns typical of Western countries (Menon et al., 2020). Generally, the THQs based on the updated RfD (6 × 10–5 mg/kg bw-day) were < 1 for the adult population for both rice types. However, children were found to be at risk of adverse non-carcinogenic health effects due to the consumption of white rice (1.60) and brown rice (2.51). Notably, the ILCR values were all above 1 × 10−4, highlighting potential carcinogenic risks due to the iAs present in the rice samples of this study.

To avoid carcinogenic risks (i.e., ILCR < 1 × 10−4) for adults and children, the rice consumption rates for adults must not exceed 0.0017 and 0.0011 kg/day for white and brown rice, respectively, as shown in the third scenario. For children, a lower ingestion rate is recommended (white rice: 0.0005 kg/day; brown rice: 0.0003 kg/day). In comparison to the previous CSF value (1.5 mg/kg bw−1 day−1), the updated CSF anticipates reduced rice consumption to minimize potential carcinogenic risks.

Similarly, with the newly established RfD of 6 × 10–5 mg/kg bw-day, to avoid non-carcinogenic risks (i.e., THQ < 1) under Scenario 4, it is recommend that adults consume no more than 0.033 kg/day of white rice and 0.021 kg/day of brown rice, while children should limit their intake to 0.009 kg/day of white rice and 0.006 kg/day of brown rice. Based on the calculated limits, the recommended weekly intake is up to 0.231 kg of white rice and 0.147 kg of brown rice for adults, and 0.063 kg of white rice and 0.042 kg of brown rice for children.

Based on the risk-based scenarios, children appear particularly susceptible to both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic effects of iAs exposure. This heightened vulnerability is not only attributable to their lower body weight but also due to the fact that their organs are still in developmental stages. Furthermore, behavioural patterns such as higher food intake relative to body mass and frequent hand-to-mouth activity contribute to greater exposure levels (Ngo et al., 2024). While most studies continue to rely on outdated toxicological benchmarks that further restrict meaningful comparisons across existing literature, one recent modelling study incorporated the revised RfD and CSF to assess iAs risk under future climate conditions using paddy-grown rice (Wang et al., 2025). The aforementioned study suggests that climate change may further amplify dietary iAs exposure and associated health risks by 2050, particularly in major rice-consuming countries similar to the findings by Kumar et al. (2025b). Moreover, several recent studies continue to apply the outdated RfD, which could result in an underestimation of the true risk, particularly among vulnerable groups such as children (Ignacio et al., 2025; Kumar et al., 2025a; Sel et al., 2026). Therefore, in order to improve the accuracy of iAs exposure evaluations and account for differences across various population subgroups, it is recommended that future research include detailed food consumption data obtained through population-specific dietary surveys (Rahman & Wu, 2025).

Conclusion

The HPLC-ICP-MS method presented a simple, efficient, and accurate quantification of As species (AsV, AsIII and DMA) in rice samples. The efficient separation of As species (AsV, AsIII, and DMA) under four minutes was achieved using a mobile phase composition of 2 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid sodium salt, 2 mM malonic acid, 4 mM TMAH, and 2% (v/v) methanol operated at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and pH 4.1. The LOD and LOQ calculated for the species were in the range of 0.114–0.430 µg/kg and 0.345–1.21 µg/kg, respectively, with good linearity (R2 ≥ 0.999). At the lowest calibration level (0.25 µg/L), measurement variability remained within acceptable limits (%RSD ≤ 20), reflecting consistent instrument performance. Besides, spiked SRM 1568b rice flour yielded acceptable recoveries between 74.5% to 108.6%, which are within the 70 to 120% range proposed by ICH guidelines. The most predominant As species was the AsIII. (0.153 mg/kg), followed by DMA (0.043 mg/kg) and AsV (0.012 mg/kg), highlighting different translocation efficiency of the As species in rice. The EDIs for iAs from brown and white rice were 5.97 × 10–4 mg/kg bw-day and 3.81 × 10–4 mg/kg bw-day for adults and 2.09 × 10–3 mg/kg bw-day and 1.33 × 10–3 mg/kg bw-day for children. All values exceeded the recently revised reference dose of 6.00 × 10–5 mg/kg bw-day set by EFSA. Additionally, THQ values above 1 and ILCR values exceeding the threshold of 1.00 × 10–4 indicate potential non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks associated with rice consumption in this study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their appreciation for the financial support received from the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) Malaysia, specifically through the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2020/STG04/UPM/02/17), which was instrumental in funding this study. The authors also gratefully for the constructive comments from the editor and the two anonymous reviewers, which have contributed to improving the quality of this manuscript.

Author contribution

Raneesha Navaretnam: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Data curation, Writing – Original draft. Ahmad Zaharin Aris: Supervision and Resources. Muhammad Faizan A. Shukor: Supervision, Resources, Conceptualization. Mohd Nor Faiz Norrrahim: Supervision, Resources, Validation. Victor Feizal Knight: Supervision and Resources. Teen Teen Chin: Resources. Noorain Mohd Isa: Project administration. Ley Juen Looi: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia and Universiti Putra Malaysia. This study was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) Malaysia, through the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2020/STG04/UPM/02/17).

Data Availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmed, M. F., Mokhtar, M. B., & Alam, L. (2020). Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risk of arsenic ingestion via drinking water in Langat River basin, Malaysia. Environmental Geochemistry and Health,43(2), 897–914. 10.1007/s10653-020-00571-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcella, D., Cascio, C., & Gómez Ruiz, J. Á. (2021). Chronic dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic. EFSA Journal. 10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J. (2023). Rice. ICC Handbook of 21st Century Cereal Science and Technology, pp. 145–151. 10.1016/b978-0-323-95295-8.00035-6

- Bundschuh, J., Niazi, N. K., Alam, M. A., Berg, M., Herath, I., Tomaszewska, B., Maity, J. P., & Ok, Y. S. (2022). Global arsenic dilemma and sustainability. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey, M., Meharg, C., Williams, P., Marwa, E., Jiujin, X., Farias, J. G., De Silva, P. M., Signes-Pastor, A., Lu, Y., Nicoloso, F. T., Savage, L., Campbell, K., Elliott, C., Adomako, E., Green, A. J., Moreno-Jiménez, E., Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A., Triwardhani, E. A., Pandiangan, F. I., … Meharg, A. A. (2019). Global sourcing of low-inorganic arsenic Rice Grain. Exposure and Health, 12(4), 711–719. 10.1007/s12403-019-00330-y

- Castañeda-Figueredo, J. S., Torralba-Dotor, A. I., Pérez-Rodríguez, C. C., Moreno-Bedoya, A. M., & Mosquera-Vivas, C. S. (2022). Removal of lead and chromium from solution by organic peels: Effect of particle size and bio-adsorbent. Heliyon. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chajduk, E., & Polkowska-Motrenko, H. (2019). The use of HPLC-NAA and HPLC-ICP-MS for the speciation of As in infant food. Food Chemistry. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.-L., Lee, C.-C., Huang, W.-J., Huang, H.-T., Wu, Y.-C., Hsu, Y.-C., & Kao, Y.-T. (2015). Arsenic speciation in rice and risk assessment of inorganic arsenic in Taiwan population. Environmental Science and Pollution Research,23(5), 4481–4488. 10.1007/s11356-015-5623-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Zhou, C., Cao, F., & Huang, M. (2024). Carcinogenic risks of inorganic arsenic in white rice in Asia. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research,18, Article 101444. 10.1016/j.jafr.2024.101444 [Google Scholar]

- Costa, B. E. S., Coelho, L. M., Araújo, C. S. T., Rezende, H. C., & Coelho, N. M. M. (2016). Analytical strategies for the determination of arsenic in rice. Journal of Chemistry. 10.1155/2016/1427154 [Google Scholar]

- Costa, B. E. D. S., Coelho, N. M. M., & Coelho, L. M. (2015). Determination of arsenic species in rice samples using CPE and ETAAS. Food Chemistry. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubadda, F., D’Amato, M., Aureli, F., Raggi, A., & Mantovani, A. (2016). Dietary exposure of the Italian population to inorganic arsenic: The 2012–2014 Total Diet Study. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 10.1016/j.fct.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amore, T., Miedico, O., Pompa, C., Preite, C., Iammarino, M., & Nardelli, V. (2023). Characterization and quantification of arsenic species in foodstuffs of plant origin by HPLC/ICP-MS. Life. 10.3390/life13020511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal, E., Díaz-González, A.M., Morales-Opazo, C. & Vigani, M. (2021). Agricultural sector review in Lebanon. FAO Agricultural Development Economics Technical Study No. 12. Rome, FAO. 10.4060/cb5157en

- Elfikrie, N., Ho, Y. B., Zaidon, S. Z., Juahir, H., & Tan, E. S. S. (2020). Occurrence of pesticides in surface water, pesticides removal efficiency in drinking water treatment plant and potential health risk to consumers in Tengi River Basin, Malaysia. Science of the Total Environment,712, Article 136540. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernstberger, H., & Neubauer, K. (2015). Accurate and rapid determination of arsenic speciation in apple juice. PerkinElmer Application Note. United States, Perkin Elmer.

- European Commission. (2023). Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/465 of 3 March 2023 amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as regards maximum levels of arsenic in certain foods. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/eur215445.pdf

- Farrell, S., Dean, M., & Benson, T. (2021). Consumer awareness and perceptions of arsenic exposure from rice and their willingness to change behavior. Food Control,124, Article 107875. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.107875 [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)/World Health Organization (WHO). (2004). The Codex General Guidelines on Sampling-CAC/GL 50-2004.

- Gil-Martín, E., Forbes-Hernández, T., Romero, A., Cianciosi, D., Giampieri, F., & Battino, M. (2022). Influence of the extraction method on the recovery of bioactive phenolic compounds from food industry by-products. Food Chemistry,378, Article 131918. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackethal, C., Kopp, J. F., Sarvan, I., Schwerdtle, T., & Lindtner, O. (2021). Total arsenic and water-soluble arsenic species in foods of the first German total diet study (BfR MEAL study). Food Chemistry. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., Ray, S. (2021). Evaluation of the structural model. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Classroom Companion: Business. Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7_6

- Hamsan, H., Ho, Y. B., Zaidon, S. Z., Hashim, Z., Saari, N., & Karami, A. (2017). Occurrence of commonly used pesticides in personal air samples and their associated health risk among paddy farmers. Science of the Total Environment,603, 381–389. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B., Chen, B., He, M., Nan, K., Xu, Y., & Xu, C. (2019). Separation methods applied to arsenic speciation. Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry. 10.1016/bs.coac.2019.04.001 [Google Scholar]

- Ignacio, S., Goessler, W., Rieger, J., Volpedo, A. V., & Thompson, G. A. (2025). Arsenic species in coastal marine fish species from the southwest Atlantic Ocean: Human health risk implications. Marine Pollution Bulletin,216, Article 117971. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.117971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Guidance for Industry Q2B Validation of Analytical Procedures: Methodology. (1996).

- Islam, S., Rahman, M. M., Islam, M. R., & Naidu, R. (2016). Arsenic accumulation in rice: Consequences of rice genotypes and management practices to reduce human health risk. Environment International,96, 139–155. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S., Rahman, M. M., Islam, M. R., & Naidu, R. (2017a). Geographical variation and age-related dietary exposure to arsenic in rice from Bangladesh. Science of the Total Environment. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S., Rahman, M. M., Rahman, M. A., & Naidu, R. (2017b). Inorganic arsenic in rice and rice-based diets: Health risk assessment. Food Control. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.06.030 [Google Scholar]

- Jayakody, J. A. K. S., Edirisinghe, E. M. R. K. B., Senevirathne, S. A., & Senarathna, L. (2024). Total arsenic and arsenic species in selected seafoods: Analysis using high-performance liquid chromatography- inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and health risk assessment. Journal of Chromatography Open. 10.1016/j.jcoa.2024.100172 [Google Scholar]

- Jitaru, P., Millour, S., Roman, M., El Koulali, K., Noël, L., & Guérin, T. (2016). Exposure assessment of arsenic speciation in different rice types depending on the cooking mode. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 10.1016/j.jfca.2016.09.007 [Google Scholar]

- Kaňa, A., Sadowska, M., Kvíčala, J., & Mestek, O. (2020). Simultaneous determination of oxo- and thio-arsenic species using HPLC-ICP-MS. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 10.1016/j.jfca.2020.103562 [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. H., Jung, H. J., & Jung, M. Y. (2016). One step derivatization with British Anti-Lewsite in combination with gas chromatography coupled to triple-quadrupole tandem mass spectrometry for the fast and selective analysis of inorganic arsenic in rice. Analytica Chimica Acta. 10.1016/j.aca.2016.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara, S., Chormey, D. S., Saygılar, A., & Bakırdere, S. (2021). Arsenic speciation in rice samples for trace level determination by high performance liquid chromatography-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, K., & Shikino, O. (2014). Arsenic Speciation Analysis in Brown Rice by HPLC/ICP-MS Using the NexION 300D/350D, PerkinElmer Application Note. United States, Perkin Elmer. https://resources.perkinelmer.com/lab-solutions/resources/docs/nexion300d-arsenicspeciationinwhiterice.pdf

- Kollander, B., Sand, S., Almerud, P., Ankarberg, E. H., Concha, G., Barregård, L., & Darnerud, P. O. (2019). Inorganic arsenic in food products on the Swedish market and a risk-based intake assessment. Science of the Total Environment. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubachka, K. M., Shockey, N. V., Hanley, T. A., Conklin, S. D., & Heitkemper, D. T. (2012). Elemental Analysis Manual: Section 4.11: Arsenic Speciation in Rice and Rice Products Using High Performance Liquid Chromatography− Inductively Coupled Plasma− Mass Spectrometric Determination. United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA). https://www.fda.gov/media/95197/download

- Kukusamude, C., Sricharoen, P., Limchoowong, N., & Kongsri, S. (2021). Heavy metals and probabilistic risk assessment via rice consumption in Thailand. Food Chemistry,334, Article 127402. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P., Khan, P. K., & Kumar, A. (2025a). Health risk assessment upon exposure to groundwater arsenic among individuals of different sex and age groups of Vaishali District, Bihar (India). Toxicology Reports,14, Article 102024. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2025.102024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Dwivedi, S., Kumar, V., Sharma, P., Agnihotri, R., Mishra, S. K., Adhikari, D., Chauhan, P. S., Tewari, R. K., & Pandey, V. (2025b). Combined effects of climate stressors and soil arsenic contamination on metabolic profiles and productivity of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Science of the Total Environment,962, Article 178415. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.178415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C., Lu, X., Hoy, K. S., Davydiuk, T., Graydon, J. A., Reichert, M., & Le, X. C. (2025). Arsenic speciation in freshwater fish using high performance liquid chromatography and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China),153, 302–315. 10.1016/j.jes.2024.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. G., Kim, D. H., Lee, Y. S., Cho, S. Y., Chung, M. S., Cho, M. J., Kang, Y. W., Kim, H. J., Kim, D. S., & Lee, K. W. (2018). Monitoring of arsenic contents in domestic rice and human risk assessment for daily intake of inorganic arsenic in Korea. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 10.1016/j.jfca.2018.02.004 [Google Scholar]

- León Ninin, J. M., Muehe, E. M., Kölbl, A., Higa Mori, A., Nicol, A., Gilfedder, B., Pausch, J., Urbanski, L., Lueders, T., & Planer-Friedrich, B. (2024). Changes in arsenic mobility and speciation across a 2000-year-old paddy soil chronosequence. Science of the Total Environment,908, Article 168351. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limmer, M. A., & Seyfferth, A. L. (2022). Altering the localization and toxicity of arsenic in rice grain. Scientific Reports. 10.1038/s41598-022-09236-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Huang, Y., Li, L., Xiong, Y., Wang, X., Tong, L., Wang, F., Fan, B., & Gong, J. (2023). Arsenic source analysis of rice from different growing environments and health risk assessment in Hunan Province, China. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 10.1016/j.jfca.2023.105637 [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., Wang, L., Jia, Y., & Yang, Z. (2016a). Arsenic speciation in locally grown rice grains from Hunan province, China: Spatial distribution and potential health risk. Science of the Total Environment,557–558, 438–444. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., Yang, Z., Kong, Q., & Wang, L. (2017). Extraction and determination of arsenic species in leafy vegetables: Method development and application. Food Chemistry,217, 524–530. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., Yang, Z., Tang, J., & Wang, L. (2016b). Simultaneous separation and determination of six arsenic species in rice by anion-exchange chromatography with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Journal of Separation Science,39(11), 2105–2113. 10.1002/jssc.201600216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, B. K., & Suzuki, K. T. (2002). Arsenic round the world: A review. Talanta,58(1), 201–235. 10.1016/S0039-9140(02)00268-0 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk, S. H., Kwaslema, D. R., Omar, M. M., & Mohamed, S. H. (2025). “Harnessing the power of soil microbes: Their dual impact in integrated nutrient management and mediating climate stress for sustainable rice crop production” A systematic review. Heliyon,11(1), Article e41158. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e41158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawia, A. M., Hui, S., Zhou, L., Li, H., Tabassum, J., Lai, C., Wang, J., Shao, G., Wei, X., Tang, S., Luo, J., Hu, S., & Hu, P. (2021). Inorganic arsenic toxicity and alleviation strategies in rice. Journal of Hazardous Materials,408, Article 124751. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon, M., Sarkar, B., Hufton, J., Reynolds, C., Reina, S. V., & Young, S. (2020). Do arsenic levels in rice pose a health risk to the UK population? Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety,197, Article 110601. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito, S., Matsumoto, E., Shindoh, K., & Nishimura, T. (2015). Effects of polishing, cooking, and storing on total arsenic and arsenic species concentrations in rice cultivated in Japan. Food Chemistry. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narukawa, T., Chiba, K., Sinaviwat, S., & Feldmann, J. (2017). A rapid monitoring method for inorganic arsenic in rice flour using reversed phase-high performance liquid chromatography-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narukawa, T., Matsumoto, E., Nishimura, T., & Hioki, A. (2015). Reversed phase column HPLC-ICP-MS conditions for arsenic speciation analysis of rice flour. Analytical Sciences. 10.2116/analsci.31.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narukawa, T., Suzuki, T., Inagaki, K., & Hioki, A. (2014). Extraction techniques for arsenic species in rice flour and their speciation by HPLC–ICP-MS. Talanta,130, 213–220. 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, B., Quinete, N., & Gardinali, P. R. (2020). Assessing accuracy, precision and selectivity using quality controls for non-targeted analysis. Science of the Total Environment,713, Article 136568. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, H. T., Hang, N. T., Nguyen, X. C., Nguyen, N. T., Truong, H. B., Liu, C., La, D. D., Kim, S. S., & Nguyen, D. D. (2024). Toxic metals in rice among Asian countries: A review of occurrence and potential human health risks. Food Chemistry,460, Article 140479. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. Q., Tran-Lam, T. T., Nguyen, H. Q., Dao, Y. H., & Le, G. T. (2021). Assessment of organic and inorganic arsenic species in Sengcu rice from terraced paddies and commercial rice from lowland paddies in Vietnam. Journal of Cereal Science,102, Article 103346. 10.1016/j.jcs.2021.103346 [Google Scholar]

- Niezen, L. E., Cabooter, D., & Desmet, G. (2024). Exploring the utility of complementary separations in liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A. 10.1016/j.chroma.2024.465469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nookabkaew, S., Rangkadi lok, N., Mahidol, C., Promsuk, G., & Satayavivad, J. (2013). Determination of arsenic species in rice from Thailand and other Asian countries using simple extraction and HPLC-ICP-MS analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 10.1021/jf4014873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD/FAO. (2024). OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2024–2033, Paris and Rome. 10.1787/4c5d2cfb-en