Abstract

Digital twins offer a promising approach to advancing healthcare by providing precise, noninvasive monitoring and early detection of diseases. In heart failure (HF), a leading cause of mortality worldwide, they can improve patient monitoring and clinical outcomes by simulating hemodynamic changes indicative of worsening HF. Current techniques are limited by their invasiveness and lack of scalability. We present a novel framework for HF digital twins that predicts patient-specific hemodynamic metrics in the pulmonary arteries using 3D computational fluid dynamics to address these limitations. We introduce a strategy to determine the minimal geometric complexity required for accurate pressure prediction and explore the effects of varying boundary conditions. By validating our digital twins against invasively-measured data, we demonstrate their potential to improve HF management by enabling continuous, noninvasive monitoring and early identification of worsening HF. This proof-of-concept study lays the groundwork for integrating digital twin technology into personalized HF care.

Subject terms: Computational biophysics, Heart failure

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) digital twins have the potential to transform patient care by enabling noninvasive, personalized monitoring and early detection of worsening HF well before the onset of symptoms. These computational models simulate patient-specific hemodynamic conditions, offering insights that could facilitate timely interventions and improve clinical outcomes for the millions of people affected by HF worldwide. HF remains a leading cause of mortality and hospitalization, with over 85,000 deaths annually in the United States and a projected economic impact rising from $30 billion to over $70 billion by 20301. The complex pathophysiology of HF involves decreased cardiac function, leading to pulmonary and systemic congestion, reduced end-organ perfusion, and increased cardiac workload, perpetuating a harmful feedback loop2,3. Early identification of worsening HF is critical for reducing mortality, hospitalizations, and healthcare costs.

Currently, invasive monitoring techniques such as right heart catheterization (RHC) and implantable hemodynamic monitors (IHMs) provide essential data on pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) and other hemodynamic parameters that predict adverse outcomes in HF patients4,5. Abnormal intracardiac and pulmonary hemodynamics are strongly associated with worse outcomes in HF, including higher rates of hospitalization and death. For example, elevated PAP and pulmonary capillary wedge pressures (PCWP) are directly related to increased risks of cardiac death, hospitalizations related to HF, and the need for heart transplantation3. Right atrial pressure (RAP) is also significantly correlated with these adverse outcomes, underscoring the importance of precise hemodynamic monitoring in the management of HF. Invasive hemodynamic metrics, such as PAP and PCWP, have been shown to outperform noninvasive measures such as heart rate in predicting the progression of HF, emphasizing the need for reliable monitoring strategies6–11. However, despite their diagnostic and predictive value, the invasive nature, risk of complications, and high cost of these techniques are significant barriers to their widespread adoption for routine monitoring of the millions of patients with HF today.

Digital twins offer an exciting potential solution: physics-based models that integrate medical imaging and hemodynamic measurements into a comprehensive, continuous, and noninvasive picture of an individual patient’s cardiovascular physiology. Unlike directly measurable metrics such as heart rate or cardiac output, which alone cannot accurately predict PAP, digital twins can incorporate these data points with detailed anatomical and physiological models to derive predictive metrics like PAP. These metrics can serve as a “digital canary”, detecting hemodynamic changes indicative of worsening HF well before conventional symptoms appear, enabling earlier interventions and customized treatment strategies. Digital twins have already shown their value in cardiovascular applications, offering critical insights into disease mechanisms and treatment outcomes12–17. In particular, previous digital twins of the pulmonary artery (PA) have demonstrated their utility in understanding hemodynamics and advancing the field through validation with physically constructed geometries and quantification of image uncertainty18–20. These studies and other PA models have provided foundational knowledge for the application of digital twins in HF21–23.

However, to fully realize the potential of digital twins in HF management, it is crucial to determine the optimal level of anatomical detail required for accurate hemodynamic modeling. Although previous studies have shown the importance of geometric detail in predicting fluid dynamics in other vascular regions, such as the coronary arteries24, it is not yet clear how much detail is necessary for the geometry of the pulmonary arteries to accurately model the hemodynamics related to HF.

The digital twin framework described here can produce patient-specific “maps” of pulmonary arterial pressure with high spatiotemporal resolution (in theory, limited only by available compute time). Physicians currently lack the tools to “map out” arterial pressures within the pulmonary circulation with any great accuracy. Right heart catheterization (RHC), the gold standard of pulmonary arterial pressure measurement today, can only provide measurements within distinct anatomic regions (e.g., the right ventricle, main pulmonary artery, and left/right pulmonary arteries). Higher spatial-resolution measurements are prevented by technical challenges such as catheter size and risk of complications such as vessel perforation

Despite this, multiple clinical studies have shown that IHM measurement of LPA pressure alone provides sufficient additional information for physicians to reduce heart failure-related hospitalizations5,6 and improve survival10 in HF patients. Consequently, the primary validation metric of this pilot digital twin study was the agreement between our CFD-predicted and IHM-measured LPA pressures.

In this study, we introduce a proof-of-concept framework for HF digital twins that combines noninvasive imaging with advanced computational modeling to predict PAP. Our approach aims to:

assess the level of branching detail needed to represent the hemodynamics of the PA, and

validate our model with PAP recorded from IHM devices.

We accomplish these objectives by using CT pulmonary angiography and RHC-measured hemodynamic data to develop digital twins of a randomly selected subsample of 20 patients out of a larger cohort of 118 HF patients with IHM devices (Fig. 1). Next, we use this workflow to characterize the relationship between geometry complexity and accuracy in predicting pulmonary hemodynamics, ultimately determining the simplest geometric detail needed to achieve accurate patient-specific results. In addition, we examine the effects of different boundary conditions on model performance and demonstrate the accuracy of our digital twins in predicting patient-specific PAP in the left pulmonary artery (LPA), as measured by the latest FDA-approved IHM devices. Our results hint at the untapped potential of digital twins to enhance the medical management of HF by offering a scalable, noninvasive alternative to current monitoring techniques. These findings represent a major step toward making noninvasive monitoring of pulmonary hemodynamics in HF patients a clinical reality.

Fig. 1. Overview of segmentation, computational modeling, and validation workflow.

a High-resolution (0.6 mm) CT angiograms of each patient’s pulmonary arterial anatomy are segmented into (b) up to 3 geometries (3D models) of increasing anatomic complexity. c Boundary conditions (upper right) are determined by RHC and hematocrit measurements obtained at the time of IHM deployment. d We then simulate blood flow using our accelerated blood flow solver, HARVEY, which (e) calculates hemodynamic metrics such as fluid velocity and pressure. f Lastly, we validate our results by comparing our digital twin pressure predictions with IHM recordings at the left pulmonary artery (LPA). Abbreviations: 0P - zero-pressure, ρlbm - lattice density, CT - computed tomography, PmmHg - physical pressure, (L)PA - (left) pulmonary artery, IHM - implantable hemodynamic monitor, RHC - right heart catheterization.

Results

Our proof-of-concept workflow for developing digital twins in 20 HF patients with IHM devices is summarized in Fig. 1. To minimize the chance of selection bias and/or confounding, we sorted the entire 118-patient cohort and selected the first 20 for image segmentation and geometry building. Next, we used high-resolution (0.6 mm) CT pulmonary angiograms to segment anatomically accurate geometries (3D models) of each patient’s pulmonary arterial tree (Fig. 1, left box). For each of the first five patients, we segmented three pulmonary arterial geometries of increasing anatomic complexity, referred to as levels 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 1, top middle box).

These models were analyzed to determine the minimum anatomic detail needed for accurate hemodynamic predictions, identifying that the simplest (level 1) geometry was sufficient. Having established this, we used level 1 geometries to build digital twins of the remaining 15 patients in the cohort, integrating hemodynamic measurements obtained by RHC at the time of IHM deployment in order to enhance the accuracy of each model (Fig. 1, top right image within the blue box). We then used the fluid solver HARVEY to simulate each patient’s pulmonary circulation within their digital twin, thus generating patient-specific hemodynamic data (Fig. 1, bottom images within the blue box). Following this, a boundary condition study was conducted to explore the effects of different boundary settings on the accuracy of the digital twin predictions, refining the model’s capability to replicate observed hemodynamic conditions. Finally, these refined digital twin models were validated by comparing their predicted PAP against invasive measurements from implantable hemodynamic monitors, demonstrating their potential for noninvasive HF monitoring and management (Fig. 1, right panel within the gray box)

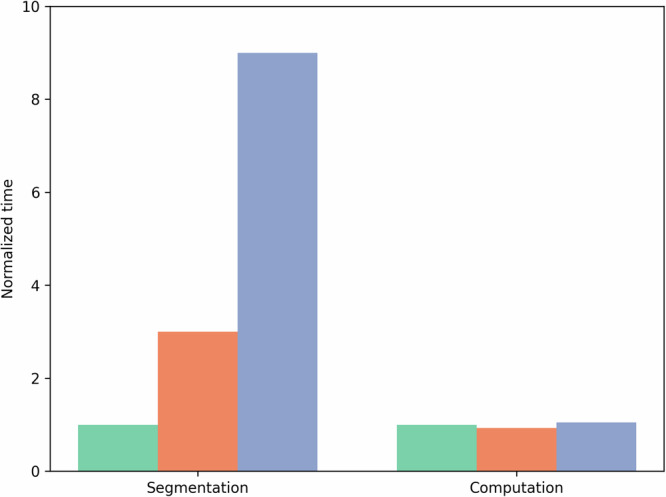

Geometric segmentation determines the complexity of the domain

In computational fluid dynamics, the geometric complexity of the domain is intricately connected to fluid behavior. In coronaries, even side branches have been shown to significantly affect flow24. To create an accurate digital twin, modelers must decide how many vessels to include, noted here as geometric complexity, as it is not feasible to model down to the capillary level using 3D techniques. To make a patient-specific digital twin, modelers must construct a vascular geometry from patient medical imaging as a domain for blood flow. However, the decision of how many vessels to include affects this segmentation process and is a key challenge as including too few vessels would generate inaccurate results, but including too many wastes segmentation time, which is often a significant bottleneck when creating digital twins (Fig. 2).

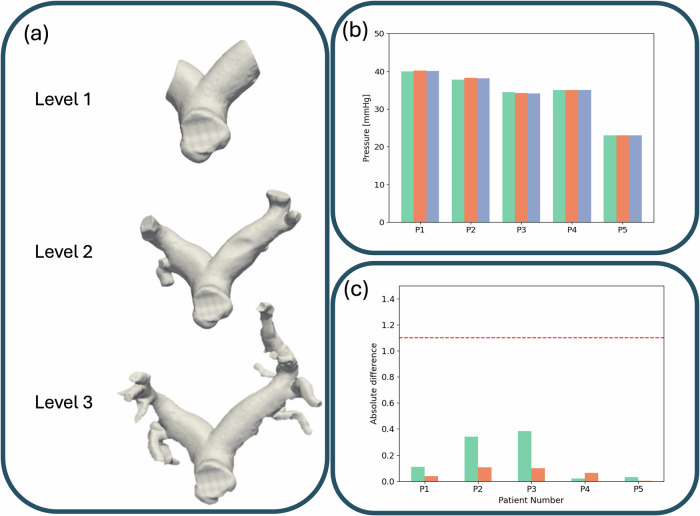

Fig. 2. Comparisons of segmentation and computation time across varying geometric complexities.

Relative times for segmenting (left) and simulating (right) a representative geometry, normalized to the time needed for a level 1 geometry. Green represents level 1 time, orange level 2, and blue level 3.

Hence, determining how many branches must be segmented from a medical image and what complexity is required is a key challenge to efficient and accurate digital twins. In this study, we developed a protocol to evaluate the influence of geometric complexity on hemodynamic predictions by segmenting the pulmonary arteries into three distinct levels of complexity for five patients (Supplementary Fig. 1).

To systematically assess the effects of reducing geometry complexity, we began by defining a “level 3” geometry, which was an extremely detailed segmentation that included the entire pulmonary arterial tree down to second-order vessel branches. Trimming the level 3 segmentation down to first-order vessel branches created a “level 2” geometry. Finally, we further simplified this into a “level 1” complexity geometry that only contained the main pulmonary artery and its primary left and right branches, labeled “level 1” complexity (3D Models box of Fig. 1, all “level 1” complexity geometries are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2).

This stepwise segmentation approach allows us to analyze how different levels of geometric detail affect hemodynamic simulations, offering a scalable framework that can be applied to other vascular regions. By understanding the trade-offs between model complexity and computational feasibility, we can optimize the balance between accuracy and efficiency in patient-specific simulations.

Progressive Simulation of Digital Twin with Varying Complexity

Simulating fluid flow was essential to accurately calculate biomarkers of interest for HF management. We utilized HARVEY25, our advanced computational fluid dynamics (CFD) solver, to create highly personalized flow models for each patient’s digital twin. HARVEY’s capabilities allowed us to simulate complex hemodynamic conditions by integrating patient-specific anatomical and physiological data, providing a detailed representation of blood flow and pressure dynamics.

To evaluate the capabilities of our digital twin, we began by simulating the model under simplified conditions and progressively introduced more realistic components to assess their impact. The initial simulations employed the most basic formulation: a steady-state flow based on the mean volumetric flow rate estimated from RHC measurements obtained during IHM implantation. For this baseline model, we implemented a no-slip boundary condition along the vessel walls and set all outlet pressures to zero, minimizing the number of parameters and simplifying the computational setup.

To determine the level of geometric complexity necessary to accurately predict the LPA pressure using our digital twin, we compared the simulated LPA pressures at three levels of geometric detail–level 1, level 2, and level 3–for five patients (Fig. 3a). Our results (Fig. 3b) indicate that the 3D simulated pressures in each geometry are approximately the same for each patient. To quantify the potential impact of geometric simplification, we calculated the absolute differences in LPA pressure relative to the level 3 geometry, which is considered the most anatomically detailed and accurate (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. Results of varying geometric complexity with respect to PAP.

a Depictions of the three levels of geometric complexities for one patient: level 1 (top), level 2 (middle), and level 3 (bottom). b 3D results: Left - Predicted LPA pressures [mmHg] for 5 patients for each level of geometric complexity - level 1 is in teal, level 2 in orange, and level 3 in blue. c The absolute difference between level 1 and level 2 geometries with level 3 geometries with level 1 in teal and level 2 in orange.

The analysis revealed that all relative differences in LPA pressure predictions between the simpler geometries (levels 1 and 2) and the level 3 geometry were well below 1.1 mmHg, our predefined tolerance for significant variation. This finding demonstrates that level 1 geometries, despite their reduced complexity, are sufficient to capture LPA pressure with accuracy comparable to that of more detailed models. Based on this result, we expanded our study to include an additional 16 patients using level 1 geometries, as they were proven to provide reliable and efficient representations for our simulations.

Outlet boundary conditions have minimal impact on pressure predictions

Having established that level 1 geometries are sufficient to accurately predict LPA pressure, we next evaluated the influence of the assumed 0-pressure outlet boundary conditions on our simulations. To assess this, we compared LPA pressure predictions using the 0-pressure outlet condition with those obtained using a more physiologically realistic boundary condition, the 1-element Windkessel model. The results of these simulations, detailed in Supplementary Table 1, show that the predicted pressures are exactly identical up to two decimal places under both conditions.

Given the lack of differences observed between the two approaches, we concluded that using 0-pressure outlet conditions does not significantly affect the accuracy of our LPA pressure predictions. To maintain efficiency and computational ease in our model, we therefore opted to continue using 0-pressure outlet conditions in subsequent simulations.

Digital twin predictions of LPA pressure agree with the IHM recordings

Building on our analysis of geometric complexity and outlet conditions, we validated our digital twin by comparing its pressure predictions with the IHM recordings. Our initial study, which focused on identifying the optimal setup for the digital twin, demonstrated that level 1 geometries and 0-pressure outlets provide an effective balance of simplicity and accuracy. With this foundation, we expanded our study to a larger cohort of 21 patients to test the performance of the model at scale. However, we excluded one patient from the final analysis due to a discrepancy of more than 10 mmHg between the IHM and RHC pressure readings, resulting in a final dataset of 20 patients.

These 20 digital twins were simulated using HARVEY with patient-specific geometries, hematocrit, and reference pressures which are used to calibrate the pressure conversion in the geometry from lattice to physical units. In this study, obtain the reference pressure by measuring the pressure at the proximal main pulmonary artery via RHC. These simulations were conducted on the Oak Ridge Leaderhip Computing Facility Frontier supercomputer, however, this framework is deployable on other computing platforms, such as cloud-based frameworks, as well.

To assess agreement, we compare digital twin-predicted LPA pressure with the IHM recordings. The simulation results, along with the corresponding IHM recordings, are presented in the top panel of Fig. 4. The data demonstrate a strong concordance between the predicted pressures and the IHM measurements. As shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 4 that the 3D predictions of PAP exhibit a mean bias of -0.1 mmHg and limits of agreement ranging from -6.4 to 6.2 mmHg compared to IHM readings. This close agreement supports the validity of our digital twin approach for noninvasive LPA pressure estimation.

Fig. 4. Results for 3D 0-pressure outlet and steady flow inlet conditions.

a Side-by-side comparisons of the 3D digital twin (3D DT - dark orange) predictions of LPA pressure and recorded IHM pressure (IHM - green). b Bland-Altman analysis to compare predicted 3D DT and IHM pressures. Dashed lines represent the mean difference +/- 1.96 standard deviations, and the solid line denotes the mean difference.

Discussion

Early detection and meticulous monitoring of HF are critical to timely intervention and improvement of patient outcomes. RHC provides invaluable insight into heart function by measuring pressure and fluid velocity among other metrics. However, due to its invasive nature, the RHC is limited to essential instances, restricting the frequency of obtainable measurements. In recent years, IHMs have alleviated some of these limitations by enabling more frequent measurements of PAP, leading to reduced mortality and hospitalizations through early detection of hemodynamic changes in HF before the onset of noticeable symptoms6–10. Digital twins offer the potential to further enhance patient monitoring by noninvasively identifying hemodynamic “digital canaries" indicative of worsening HF and paving the way for future noninvasive, remote fluid monitoring.

In this study, we developed a digital twin model for HF that represents the pulmonary vasculature, validated against IHM recordings. We first investigated the level of geometric complexity required for the digital twin to accurately replicate observed data and assessed the influence of boundary conditions on simulation results. Subsequently, we compared the pressure predictions of the digital twin with the IHM measurements, quantifying the predictive accuracy.

Our initial focus was to determine the geometric complexity needed to accurately reconstruct the pulmonary arteries, addressing a significant gap in the literature: identifying the minimal level of geometric detail necessary for reliable pressure prediction. This aspect is crucial for reducing the costs associated with patient-specific modeling, as shown in Fig. 2. The required level of geometric complexity is context-dependent; for example, prior research has demonstrated that greater detail, such as including side branches, is necessary for accurate hemodynamics in coronary arteries24. It bears emphasis here that we specifically excluded HF patients with a history of congenital heart disease from this study, as they 1) comprise a small minority of the overall HF patient population, and 2) can be expected to have clinically significant variations in pulmonary vascular anatomy (e.g., pulmonary stenosis, anomalous branching patterns, significant collateralization) that would significantly affect pulmonary hemodynamics and likely require extremely detailed segmentations to capture their hemodynamic environment accurately. Without adequate consideration of the geometric complexity of the domain, modelers risk either under-representing the vascular network, leading to inaccurate predictions, or overcomplicating the model, resulting in inefficiency. To date, no studies have specifically examined the required complexity of pulmonary artery segmentations for accurate pressure prediction.

To study the effects of geometric complexity, we examined 3 different levels of complexity in 5 patients with 3D digital twins. Our findings indicated that the predicted LPA pressure in the level 1 geometry closely matched those of level 2 or level 3 LPA pressures. This result is advantageous, as level 1 geometries take far less time to segment (Fig. 2). Although this result holds for LPA pressure predictions, more detailed geometries may be necessary for studies focused on hemodynamics in distal branches or when averaging hemodynamic metrics across the entire geometry. The finding that the simplest geometry is sufficient for predicting LPA pressure motivates future investigations into whether even simpler geometries or reduced-order models could provide similarly accurate predictions. While this is a valuable direction for future work, it is beyond the scope of this proof-of-concept study, which focuses on demonstrating that pressure predictions are feasible using 3D models. We note that our 3D model can accurately predict pressure without needing elastic walls or complex boundary conditions, an advantage of the 3D model over reduced-order models, which rely on a larger number of parameters for tuning. While level 1 geometries are sufficient and preferred for predicting LPA pressure, our methodology should be re-evaluated for digital twins with different objectives.

Building on the findings regarding geometric complexity, we expanded our study to include 20 patient-specific level 1 geometries and compared the predicted pressures to IHM measurements. The digital twin pressure predictions matched the IHM measurements well, with all predictions falling within the range deemed acceptable—a difference between -8.2 and 6.5 mmHg26. The Bland-Altman 95% interval for these comparisons is [-6.4,6.2] mmHg across the 20 patients, within the tolerance noted in ref. 26 for comparisons between IHMs and RHC PAP values. Furthermore, we note that these successful predictions occur without precise knowledge of the IHM location—we only know that the IHM device is placed in the left pulmonary artery. Instead, we assume that the pressure drop in the LPA is minimal, and thus represents LPA pressure as the pressure predicted at the vessel’s longitudinal midpoint. Although simulated pressure predictions match IHM recordings well, predictions could be even more accurate if the precise location of the IHM device in the simulated geometry were known, as the localization of IHM recordings is uncertain. These comparisons were conducted using steady inlet and 0-pressure outlet conditions for the 3D model, further confirming that level 1 segmentation models can effectively predict IHM pressure readings.

Despite these promising results, this proof-of-concept study has some limitations. A key limitation is the reliance on a reference pressure to convert LBM density to physical pressure27, which was derived from RHC measurements at the proximal main pulmonary artery. Future research should explore methods to minimize the dependency on calibration reference pressures or develop noninvasive approaches to obtain them. Additionally, this study’s small cohort size is a limitation. Future studies should validate HF digital twins with a larger, more diverse patient population, potentially leveraging semi-automatic or fully automated segmentation methods.

This work advances the modeling and HF field by (1) determining the level of detail necessary to accurately capture pulmonary artery pressure in a digital twin and (2) demonstrating that LPA pressure can be reliably predicted using a digital twin. We have created a pipeline to obtain patient-specific HF digital twins, showing their robustness, reliability, and feasibility for noninvasive LPA pressure prediction. Although this study is a preliminary proof-of-concept, the ability to replicate IHM readings suggests significant potential for these models. This study leverages 3D models to analyze the effects of geometric differences on fluid flow, as geometry plays a critical role in hemodynamics. However, this work also serves as a foundation for future directions, such as developing reduced-order or AI surrogate models, to advance HF monitoring and other applications.

Digital twins offer a powerful tool to examine hemodynamic changes in HF, such as pressure alterations that are crucial for patient monitoring. Beyond noninvasive predictive pressure, digital twins can provide a range of hemodynamic metrics relevant to HF management. By examining these hemodynamic changes, digital twins could uncover advanced biomarkers that are synergistic with already established metrics to refer patients to care before significant decompensation. HF digital twins also show promise to enhance the monitoring already offered by RHC and IHMs. For instance, IHMs often require the patient to be positioned prone on a sensor for readings. Digital twins have the potential to use this one-time measurement to calibrate the digital twin to predict PA pressure throughout the day. Additionally, HF digital twins could serve as alternatives to RHC or IHMs for patients who cannot undergo invasive procedures due to concerns of complications. Moreover, HF digital twins show promise in settings such as the ICU or post-operative care to monitor for HF after heart transplants.

In conclusion, we have developed a proof-of-concept HF digital twin capable of accurately predicting LPA pressure. Our findings demonstrate that even level 1 geometries are sufficient for noninvasive LPA pressure prediction. Our results establish a much-needed personalized HF digital twin for noninvasive detection of worsening HF and lay the groundwork for proactive and remote monitoring strategies to mitigate HF burden.

Methods

Patient data and Clinical Methods

To validate the pre-clinical digital twin, we performed a retrospective study to determine the agreement between our digital twin and IHM recorded pressure. This study was conducted in accordance with relevant ethical regulations and approved by the institutional review board at Duke University (IRB Protocol 00100536). This study fell under IRB exemption category 4 as it involved the analysis of existing records where individuals could not be identified, allowing for the secondary research of previously collected information without requiring individual consent. To develop and validate the HF digital twins, we selected a cohort of patients with diagnosed HF who had undergone both CT pulmonary angiography and RHC. The study collected patient characteristics, CT angiograms, and RHC data from invasive tests. We selected a total of 21 patients out of a cohort of 118 patients based on the quality of their CT images and the availability of IHM data. The inclusion criteria required patients to have high-resolution CT pulmonary angiograms (0.6 mm slice cuts) and complete hemodynamic data from RHC. One patient was excluded from the final analysis due to discrepancies between the RHC and IHM pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) measurements exceeding 10 mmHg. RHC was performed immediately prior to IHM delivery; recorded metrics included PAP and cardiac output (CO), as calculated using the Fick equation. Hematocrit was also measured at the time of IHM implantation. These values were used to inform all digital twin simulations.

Supplementary Table 2 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient cohort whose personalized HF digital twins were created. The cohort included 12 male and 9 female patients, with an average age of 67 years. Most of the patients had a history of hypertension and diabetes, and all had evidence of elevated pulmonary artery pressure. The digital twins were then used to simulate hemodynamic conditions, providing a noninvasive method for continuous monitoring and prediction of HF progression.

Generating Pulmonary Artery Geometries

Patient-specific, 3D models of the pulmonary arterial tree were segmented from high-resolution (0.6mm) CT pulmonary angiograms acquired within 1 year of IHM implantation. The segmentation process was conducted using the Aquarius iNtuition software (TeraRecon Aquarius, San Mateo, CA) under the oversight of an experienced physician and trained personnel. Two segmentation methods were used based on anatomical requirements and the size of the arterial segment: a region-growing approach for larger vessels and a manual slice-by-slice method for more complex regions. These methods ensured accurate segmentation of the pulmonary arterial tree, customized to the specific vascular structures in each case. Consequently, geometries were created up to the third generation of pulmonary bifurcations from which they were trimmed down to create the first, second, and third level of complexity in the tree structure: level 1 models included only the main PA and left/right PA branches; level 2 models included the first order bifurcations (lobar pulmonary arteries), and level 3 models included the second order bifurcations (segmental pulmonary arteries). An example of each type of geometry can be seen in the left of Fig. 3.

Once segmentation was complete, the resulting geometries were exported as stereolithography (STL) files for further refinement. These STL files were initially post-processed using Meshlab software28, where Poisson surface reconstruction and Laplacian smoothing techniques were applied to enhance mesh quality by reducing noise and improving surface smoothness. Subsequent processing was performed using Blender (version 2.7.9, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), where additional modifications were made to prepare the geometries for analysis. These analyzes included blunting, which involved trimming the vessel ends to apply boundary conditions, as well as applying mesh smoothing filters to eliminate surface artifacts caused by the voxelated nature of the volumetric imaging data. Following the smoothing procedures, the refined geometries were processed through an in-house developed Python script utilizing the VTK (Visualization Toolkit) and VMTK (Vascular Modeling Toolkit) libraries. This automated pipeline facilitated the extraction of critical geometric features, including centerlines, openings (inlet/outlet), and associated parameters such as center, normal vectors, and cross-sectional area. These features were essential for setting the boundary conditions in subsequent hemodynamic simulations. In addition, the centerline points and tangent vectors derived from the VMTK pipeline were used to consistently identify anatomical regions of interest within the pulmonary arterial tree. This consistent mapping was particularly crucial for validation purposes and for extracting hemodynamic metrics at key locations, such as the left pulmonary artery (LPA), where IHMs were placed.

Computational fluid dynamic solver

In recent years, CFD for cardiovascular applications has seen significant advancements. The computational methodology for simulating blood flow in the PAs in this study utilized the massively parallel fluid dynamics solver, HARVEY, as described in our previous publications25,29. HARVEY uses the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM), a mesoscopic approach that recovers the Navier-Stokes equations by simulating fluid dynamics at the particle level. The LBM approach allows for modeling complex fluid behavior by representing the fluid as particles with distribution functions, which evolve in space and time according to the lattice Boltzmann equation27:

| 1 |

where x denotes the position in space, t represents time, ci marks the velocity, and Ωi is the Bhatnagar-Gross-Krook (BGK) collision operator. For spatial velocity discretization, HARVEY employs the D3Q19 model, which is particularly well-suited for complex 3D geometries. We utilize a grid spacing of 100 microns, which was verified to converge spatially through a representative convergence study. For details and representative convergence graphs, see Supplementary Figures 3 and 4. In this study, rigid wall boundaries and the halfway bounce-back condition were used to model the interactions between blood flow and the vessel walls.

Digital twin set-up and assumptions

To construct the digital twin models, blood in the pulmonary arteries was modeled as an incompressible Newtonian fluid with a constant density of 1060 kg/m3. The patient-specific dynamic viscosity, μ, was calculated based on the hematocrit, ϕ, using the following relationship30

| 2 |

where μ0 = 1.2 cP is the viscosity of plasma24,30,31.

This model assumes a constant cardiac output as the inlet condition for the simulations, using a volumetric flow rate to approximate physiological conditions. The outlet boundary conditions were set using either a 0-pressure condition or a 1-element Windkessel model, which was calibrated with RHC data to account for resistance based on Murray’s law.

The use of the 1-element Windkessel model, which simulates vascular resistance and compliance, allows a more physiologically accurate representation of pressure wave reflections in the pulmonary vasculature, compared to the simpler 0-pressure outlet condition. This approach was validated by comparing the results of the digital twin simulation with clinical measurements to ensure their reliability for patient-specific hemodynamic predictions.

Hemodynamic metrics

In this study, the primary focus is on validating the use of HF digital twins to calculate PAP in the LPA. The pressure values obtained from the LBM component of the digital twin need to be converted from LBM units to physical units to accurately represent the physiological pressure in the LPA. This conversion process begins by computing a reference density, ρ0, which serves as a baseline for transforming LBM density values into real-world measurements. The reference density, ρ0, is calculated using the following equation:

where ρmean denotes the mean LBM density at a cross-section, pmap denotes the mean measured pressure at the same location as ρ0, u marks the velocity with the subscripts “lbm" and “physical" marking LBM and real-world physical units, respectively, is the lattice speed of sound for D3Q19, and ρblood is the density of blood [kg/m3]. Note that pmap is the “reference pressure" used to calibrate the conversion of lattice units to physical units, measured via RHC at the inlet to the PA. Once the reference density, ρ0, is determined, the physical pressure, P [Pa] is calculated by converting the LBM pressure values using the relationship:

| 4 |

where Δx represents the grid spacing distance and Δt is the timestep duration in the simulation. This conversion ensures that the pressure values of the digital twin are accurately translated into real-world pressures, enabling meaningful comparisons with clinical measurements obtained by invasive methods.

The approach outlined above allows for a robust validation of the digital twin models against patient-specific hemodynamic data, ensuring that the noninvasive simulations can reliably predict PAP in the LPA. This validation is crucial in demonstrating the potential of digital twins to replace or complement current invasive monitoring techniques in the management of HF.

Metrics of success

This study seeks to (1) determine the appropriate level of geometric complexity needed in PA segmentations for accurate HF digital twins and (2) the agreement between the pressure readings obtained from the simulations of digital twins and those of IHMs. To assess the appropriate level of complexity, we compared the mean pressure readings in the LPA at different levels of segmentation complexity. Specifically, the mean pressure in the middle LPA was compared between level 1 and level 3, as well as between the level 2 and level 3 segmentations. A difference of less than 1.1 mmHg was considered equivalent, based on FDA-approved tolerances for algorithmic error margins32.

For validation of the digital twin measurements against IHM data, the absolute difference in pressure readings, expressed in mmHg, was calculated. Consistent with device performance standards, we use a 95% accuracy interval (limits of agreement) relative to RHC data, defined as a range between -8.2 and 6.5 mmHg26. This interval was set as the acceptable range for deviations between the digital twin predictions and the IHM measurements to establish their clinical reliability.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Megan Llewellyn for assistance with illustrations. The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DP1AG082343. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health and the Duke Center for Computational and Digital Health Innovation. Funding was also given under NSF GRFP under Grant No. DGE 164486. An award of computer time was provided by the INCITE program. This research also used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725.

Author contributions

J.R.G.: conceptualization, methodology, software development, analysis, draft writing. C.W.J.: conceptualization, segmentation, draft writing. C.T.: analysis, methodology, software development, and draft writing. A.G.: analysis, segmentation, figures. M.F.: conceptualization, data acquisition, M.R.P.: conceptualization, data acquisition. A.R.: funding acquisition, resources, supervision, conceptualization and draft writing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The de-identified patient data from Duke Hospital may be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to approval from the Institutional Review Board.

Code availability

The code is available for academic license through the Duke University Office of Licensing and Ventures. A prototype of the fluid solver code can be found in the Duke Repository at 10.7924/r45t3t64k.

Competing interests

Dr Fudim was supported by Alleviant, Gradient, Reprieve, Sardocor, and Doris Duke. He is a consultant/has ownership interest in Abbott, Acorai, Ajax, Alio Health, Alleviant, Artha, Audicor, AxonTherapies, Bodyguide, Bodyport, Boston Scientific, Broadview, Cadence, Cardiosense, Cardioflow, CVRx, Daxor, Edwards LifeSciences, Echosens, EKO, Endotronix, Feldschuh Foundation, Fire1, FutureCardia, Galvani, Gradient, Hatteras, HemodynamiQ, Impulse Dynamics, Medtronic, Merck, NovoNordisk, NucleusRx, NXT Biomedical, Omega, Orchestra, Parasym, Pharmacosmos, Presidio, Procyreon, Proton Intelligence, Puzzle, ReCor, SCPharma, Shifamed, Splendo, STAT Health, Summacor, SyMap, Terumo, Vascular Dynamics, Vironix, Viscardia, Zoll. Dr. Patel has been supported with research grants from Bayer, Janssen, Heartflow, Novartis, and the NIH. He serves on the advisory board or as a consultant for Bayer, Janssen, Novartis.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41746-025-01920-8.

References

- 1.Heidenreich, P. A. et al. Economic issues in heart failure in the United States. J. Card. Fail.28, 453–466 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozkurt, B. et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur. J. Heart Fail.23, 352–380 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper, L. B. et al. Hemodynamic predictors of heart failure morbidity and mortality: fluid or flow? J. Card. Fail.22, 182–189 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevenson, L. et al. Chronic ambulatory intracardiac pressures and future heart failure events. Circulation: Heart Fail.3, 580–587 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zile, M. R. et al. Intracardiac pressures measured using an implantable hemodynamic monitor. Circulation: Heart Fail.10, e003594 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham, W. T. et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet377, 658–666 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham, W. T. et al. Sustained efficacy of pulmonary artery pressure to guide adjustment of chronic heart failure therapy: complete follow-up results from the CHAMPION randomised trial. Lancet387, 453–461 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourge, R. C. et al. Randomized controlled trial of an implantable continuous hemodynamic monitor in patients with advanced heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.51, 1073–1079 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindenfeld, J. et al. Haemodynamic-guided management of heart failure (GUIDE-HF): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet398, 991–1001 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindenfeld, J. et al. Implantable hemodynamic monitors improve survival in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.83, 682–694 (2024).38325994 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fudim, M., Butler, J. & Kittipibul, V. Implantable hemodynamic-guide monitors: a champion among devices for heart failure (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ong, C. W. et al. Computational fluid dynamics modeling of hemodynamic parameters in the human diseased aorta: A systematic review. Ann. Vasc. Surg.63, 336–381 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, J.-M. et al. Perspective on cfd studies of coronary artery disease lesions and hemodynamics: a review. Int. J. Numer. methods Biomed. Eng.30, 659–680 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taebi, A. Deep learning for computational hemodynamics: a brief review of recent advances. Fluids7, 197 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Horst, A. et al. Towards patient-specific modeling of coronary hemodynamics in healthy and diseased state. Comput. Math. Methods Med.2013, 393792 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Augustin, C. M. et al. Patient-specific modeling of left ventricular electromechanics as a driver for haemodynamic analysis. EP Europace18, iv121–iv129 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakata, K. et al. Assessing the arrhythmogenic propensity of fibrotic substrate using digital twins to inform a mechanisms-based atrial fibrillation ablation strategy. Nature Cardiovascular Research 1–12 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Yao, T. et al. Image2Flow: A proof-of-concept hybrid image and graph convolutional neural network for rapid patient-specific pulmonary artery segmentation and CFD flow field calculation from 3d cardiac MRI data. PLOS Computational Biol.20, e1012231 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bordones, A. D. et al. Computational fluid dynamics modeling of the human pulmonary arteries with experimental validation. Ann. Biomed. Eng.46, 1309–1324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colebank, M. J. et al. Influence of image segmentation on one-dimensional fluid dynamics predictions in the mouse pulmonary arteries. J. R. Soc. Interface16, 20190284 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang, B. T. et al. Wall shear stress is decreased in the pulmonary arteries of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: an image-based, computational fluid dynamics study. Pulm. circulation2, 470–476 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kheyfets, V. O. et al. Patient-specific computational modeling of blood flow in the pulmonary arterial circulation. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed.120, 88–101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conijn, M. & Krings, G. J. Understanding stenotic pulmonary arteries: can computational fluid dynamics help us out? Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol.64, 101452 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vardhan, M. et al. The importance of side branches in modeling 3d hemodynamics from angiograms for patients with coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep.9, 8854 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Randles, A. P., Kale, V., Hammond, J., Gropp, W. & Kaxiras, E. Performance analysis of the lattice Boltzmann model beyond navier-stokes. In 2013 IEEE 27th International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Processing, 1063–1074 (IEEE, 2013).

- 26.Abraham, W. T. et al. Safety and accuracy of a wireless pulmonary artery pressure monitoring system in patients with heart failure. Am. heart J.161, 558–566 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krüger, T. et al. The lattice boltzmann method. Springe. Int. Publ.10, 4–15 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cignoni, P. et al. MeshLab: an Open-Source Mesh Processing Tool. In Scarano, V., Chiara, R. D. & Erra, U. (eds.) Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference (The Eurographics Association, 2008).

- 29.Randles, A., Draeger, E. W., Oppelstrup, T., Krauss, L. & Gunnels, J. A. Massively parallel models of the human circulatory system. In Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 1–11 (2015).

- 30.Pirofsky, B. et al. The determination of blood viscosity in man by a method based on poiseuille’s law. J. Clin. Investig.32, 292–298 (1953). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vardhan, M. et al. Non-invasive characterization of complex coronary lesions. Sci. Rep.11, 8145 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Premarket Notification 510(k) Smart Wedge algorithm, K230579. Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf23/K230579.pdf (2023).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified patient data from Duke Hospital may be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to approval from the Institutional Review Board.

The code is available for academic license through the Duke University Office of Licensing and Ventures. A prototype of the fluid solver code can be found in the Duke Repository at 10.7924/r45t3t64k.