Abstract

The pandemic of influenza A virus (IAV) is on the rise worldwide, however, drug resistance to anti-influenza drugs has been widely found. The viral mutation of IAV highlights the necessitate for discovery of new antiviral agents with broad-spectrum efficacy. Arbidol, an effective pharmaceutical against IAV and other viruses, inhibits viral fusion by targeting a conserved binding region across multiple virus types. The binding area of Arbidol is conserved towards many types of viruses, however, the structural characteristics of Arbidol make it possible human ether-α-go-go related gene (hERG) potassium channel inhibitory. The risk of arrhythmias by Arbidol will limit its further application. Therefore, developing new broad-spectrum antiviral drugs with reduced side effects based on Arbidol’s scaffold is imperative. In this study, 50 natural products were screened for effective universal antiviral drug based on the structure–activity relationship between Arbidol and hemagglutinin (HA). Due to the structural characters of Arbidol related to hERG inhibition, the inhibitory activity of Arbidol on hERG channels were also analyzed by patch clamp technology and molecular docking for toxicity and safety evaluation of drug screening and development. The IC50 of Arbidol to hERG was 0.3030 µM. The results showed that Glycyrrhetinic acid has lower binding energy than Arbidol in the binding site. The molecular structure of Glycyrrhetinic acid is more flexible, which avoids significant interactions with hERG. These findings highlight glycyrrhetinic acid as a promising broad-spectrum anti-IAV candidate drug.

Keywords: Influenza inhibitors, Hemagglutinin, hERG, Arbidol, Broad-spectrum, Glycyrrhetinic acid

Introduction

Influenza is prevalent and causes global epidemics continuously. Influenza virus is an enveloped negative-strand RNA virus belonging to the family of Orthomyxoviridae, which is classified into types A-D. Influenza A virus (IAV) is the most pathogenic [49], H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes are the major strains infecting humans. Antigenic shifts of IAV, makes it cross the species barrier, resulting in a higher risk of pandemics [7]. Influenza vaccines have shown a protection range of 19%-60% over the past 15 influenza seasons, with the 2023–2024 season’s effectiveness falling within 44% [10]. The typical influenza pharmaceuticals are inhibitors of hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA) [43], nucleoprotein (NP), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and extracellular domain of M2 [36]. HA and NA are two surface glycoproteins located in the viral membrane, which are the primary surface antigens of IAV [2]. NA promotes penetration and movement of the virus in the respiratory mucosa. HA is a trimeric transmembrane glycoprotein [20, 26], which drives the fusion of the virus by binding to sialic acid receptors [30], and mediates viral entry [33]. Anti-influenza drugs confront drug resistance at present, especially for NA inhibitors. Reduced susceptibility of IAV to NA inhibitors [9] has been commonly found [16], which makes the inhibitors more ineffective [18, 52].

The continuous viral mutation of IAV highlights the necessity for discovery of new antiviral agents targeting conserved antigen determinants with broad-spectrum efficacy. Owing to the critical role of HA during the initial infection, it becomes an ideal target. HA could provide broadly cross-reactive protection against different influenza viruses [41, 42]. HA includes two sub units, HA1 consists of the globular head [4], however, HA2 and part of HA1 comprise the stem region [12] which are more conserved. The globular head of antigen variability is responsible for the binding of receptor, and the stem mediates the membrane fusion of virus [13] in lower pH [11]. The highly conserved [40, 53] stem region is a perfect target for universal antiviral inhibitors [14].

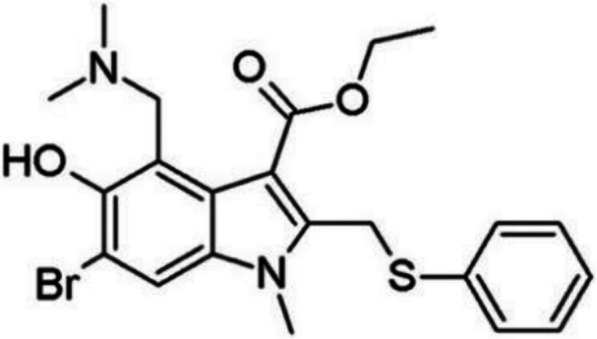

Arbidol (Umifenovir) is indole derivative, with two tertiary amine and aromatic rings groups in the structure (Fig. 1), and is a broad antiviral drug to non-enveloped and enveloped viruses [35]. Arbidol binds to the hydrophobic cavity in the HA stem area. HA performs conformational changes during the fusion of virus in acidic pH. Arbidol blocks the low pH-induced fusion of virus [19]. Arbidol was also used to inhibit severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [35], however, the majority of compounds containing tertiary amine groups and aromatic rings, could establish π-π stacking or hydrophobic interactions with the amino acid residues in the human ether-α-go-go related gene (hERG) potassium channel cavity [25], leading to arrhythmias caused by hERG channel inhibition. Arbidol has both tertiary amines and aromatic groups in the structure, making it a potential hERG potassium ion channel inhibitor.

Fig. 1.

Structure of Arbidol

The hERG Kv11.1 voltage-gated potassium ion channel, is encoded by human ether-a-go-go related gene which mediates the repolarization current of the heart [3] in the cardiac action potential (AP) [46]. The hERG K+ channels [32] keep open during the depolarization phase [23], and then maintain the QT interval when the membrane repolarizes. Inhibition of the hERG channels delays repolarization, prolongs QT intervals [17, 31], resulting in a high risk of arrhythmia [5]. hERG inhibitory activity study is very important to avoid hERG related cardiotoxicity. FDA demands the measurement of hERG inhibitory activity of new drugs due to their potential to cause AP prolongation and arrhythmias [15]. Astemizole, Terfenadine and Cisapride have been withdrawn from the market for hERG inhibition effect [34, 38].

Many components in traditional Chinese medicine have good therapeutic efficacy against influenza [41, 42]. In this study, 50 natural active ingredients were screened for effective broad-spectrum antiviral drugs based on the structure–activity relationship of Arbidol on HA. Due to the potential structure related hERG inhibition of Arbidol, the inhibitory activity of Arbidol on hERG channels was also analyzed by patch clamp technology and molecular docking for the hERG toxicity and safety evaluation of drug screening and development.

Methods and materials

RBD analysis of Arbidol to HA and hERG

The model of crystal structure of HA from the (H3N2) influenza virus A (PDB ID: 5THF, http://www1.rcsb.org) was used as the model for the study of binding site. 5THF is a complex of H3 monomer from HA and two amino acids, the structure was solved by electron microscopy with 2.59 Å resolution [44]. H3 was separated from the complex by PyMOL 3.0 (https://pymol.org/) and used as an independent receptor for inhibitors screening. The human hERG-related K+ channel structure (PDB ID: 5VA1) in a depolarized conformation was used for the analysis [47] of RBD, which was also downloaded from PDB (http://www1.rcsb.org). The structure was determined by electron microscopy with a resolution of 3.8 Å and the pore is open in 5VA1. 5VA1 was used to evaluate the inhibitory activity of compounds.

The molecular docking experiment was carried out by AutoDock Vina and PyMOL software. Solvents were removed from HA and hERG protein, and then hydrogens were added to prepare macromolecular receptor. Charge calculation and atoms type assign were carried out before molecular docking. The structure of ligand molecules were optimized by M2M force field to obtain the lowest energy conformation. The conformations with the lowest binding energies were chosen as dominant conformation. The inhibitors were screened in 50 natural plant active ingredients from “Treatise on Febrile Diseases”. A grid box (60 Å × 60 Å × 60 Å) for the HA, centered at (17.133, 54.849, -30.277) Å, was adopted in the docking experiments using the Auto Dock tools. The grid box for the hERG channel was centered at (92.951,57.473, 52.456) Å. The study was confined to molecular docking without validation by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

Automatic patch clamp

Materials and apparatus

Fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), and TrypLE™ Express were got from Gibco (China). Cisapride (positive control drug), Remdesivir, Oseltamivir, KCl, MgCl2•6H2O, NaCl, potassium aspartate, and Na₂-ATP were from Sigma-Aldrich (China). D-glucose, CaCl2•2H2O and methanol were pursed from Thermo Fisher. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was pursed from Solarbio (China). HEPES buffer was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Shanghai,China). Stable expression cell line of hERG was pursed from Sarl Creacell (France).

Temperature control system (Julabo, FPE50-HE, F25-HE), automatic patch clamp (Sophion, QPatch 48X). Sophion & GraphPad Sophion Analyzer 6.5 & GraphPad Prism was used in data analysis.

Cell culture and cell passage

Cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum at 37 °C and 5% (v/v) CO2. The cells were washed once with PBS after the medium was removed. Then 1 mL of TrypLE™ express solution was added, followed by incubating at 37 ℃ for 1 min. 5 mL of preheated (37 ℃) complete medium was added and the cells were detached from the dish bottom. The cells were gently suspended, followed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The cells were inoculated with a final density of 6 × 105. The cell density must not exceed 80% in order to maintain the electrophysiological activity. Cells were separated with TrypLE ™ Express before patch clamp analysis. Culture medium was added to terminate digestion. The final density of cells were adjusted to 2–3 × 106 cells/mL before detection.

Automatic patch-clamp

IhERG currents were elicited using the whole-cell, patch-clamp electrophysiology technique in the voltage-clamp mode. Automatic patch clamp QPatch was used to carry out the electrophysiological testing. The peak tail current density was then used to assess the voltage dependence of the compounds [39]. The elicited tail current density in the cells was used to be plotted as a current–voltage curve. Extracellular solution: 140 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2•6H2O, 2 mM CaCl2•2H2O, 10 mM D-glucose, 10 mM HEPES, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4•2H2O, and pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Internal solution: 20 mM KCl, 115 mM K-Aspartic, 1 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM Na2-ATP, and pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. HEK293 cell line was used to express hERG channel proteins. First, put the prepared cells on the centrifuge of workbench and replace the cell culture medium with extracellular fluid. The robotic arm scans the MTP-96 board and QPlate chip barcodes and grabs them to the measurement station. Intracellular and extracellular fluid were extracted from the liquid pool and added into the intracellular fluid pool, cell and compound pool. All measurement points on the QPlate must undergo initial quality control. The quality control process includes extracting cell suspension from the cell container of the centrifuge, and positioning the cells onto the chip hole through a pressure controller, establishing a high resistance seal, and forming a whole cell recording mode.

The voltage stimulation scheme for recording hERG current with whole cell patch clamp was as follows: when a whole cell seal was formed, the cell membrane voltage was held at -80 mV. The clamping voltage was depolarized from -80 mV to -50 mV for 0.5 s (as leakage current detection), then stepped to 30 mV for 2.5 s, and quickly restored to -50 mV for 4 s to excite the tail current of the hERG channel. Repeat data collection every 10 s to observe the effect of drugs on hERG tail current. The experimental data was collected by the QPatch screening workstation and stored in the database server. Each concentration was set to be administered twice for at least 5 min. Each concentration should be independently repeated three times using at least three cells. All electrophysiological tests were conducted at room temperature.

The positive control was Cisapride. 3.37 mg of Cisapride was added to 682.41 μL DMSO to prepare a 10 mM storage solution. Cisapride storage solution was diluted to 1000 μM, 100 μM, 33.3 μM, 10 μM, 3.33 μM and 1 μM by DMSO sequentially. The dilution solution was further diluted to get 300 nM, 100 nM, 30 nM, 10 nM and 3 nM working fluid by extracellular fluid.

Data analysis

For each concentration, the average value of three datas represents the current value after the action of that concentration. The current for each compound was standardized. The current value of each drug concentration and the reference current value of the blank control were normalized (). The inhibition rate corresponding to each drug concentration was then calculated.

| 1 |

The mean (Mean), standard deviation (SD), and standard error (SE) for each concentration inhibition rate were calculated.

| 2 |

The IC50 value of each compound was calculated using Eq. 2 and nonlinear fitting was performed on dose—dependent effects [27, 37], where IC50 was the half inhibitory concentration. The calculation and curve fitting of IC50 were completed using GraphPad Prism software.

Results and discussion

hERG inhibitory of Arbidol

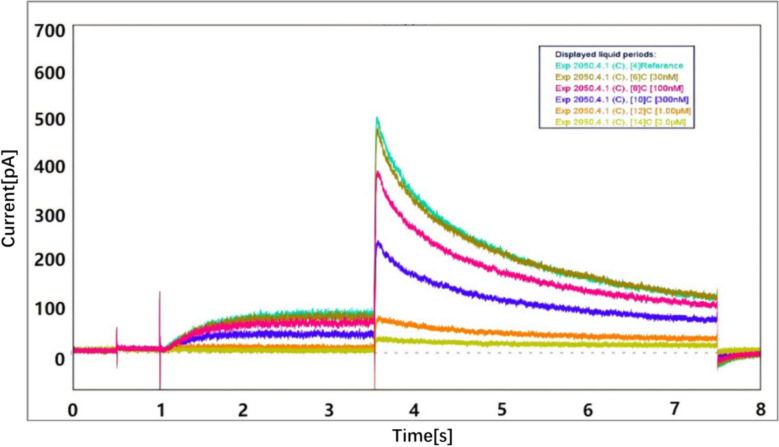

Automatic patch-clamp

Arbidol exhibits inhibitory effects of hERG channels (Fig. 2). Arbidol inhibited outward IhERG tail current. The IhERG current inhibition was 93.79% when the concentration was 3 µM. As the concentration of Arbidol increases, the inhibitory effect gradually increases. The inhibitory effect of Arbidol to hERG ion channels is concentration dependent. The IC50 of Arbidol on hERG is 0.3030 µM (Fig. 3). The patch clamp experiment indicated that Arbidol exerted an inhibitory effect on potassium ions by inhibiting hERG ion channels, and led to arrhythmia (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Whole-cell IhERG currents of Arbidol

Fig. 3.

Inhibition rate of Arbidol on IhERG currents

Table 1.

Inhibition of hERG current by Arbidol and IC50 (n = 3)

| Concentration (µM) | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

hERG current inhibitory % (Mean ± SE) |

4.80 ± 1.00% | 20.31 ± 1.30% | 48.6 ± 2.36% | 83.49 ± 1.16% | 93.79 ± 0.28% |

| IC50 | 0.3030 µM | ||||

Molecular dock

On the basis of patch clamp experiments, structure–activity relationship (SAR) of inhibitory effect of Arbidol on hERG was furtherly investigated by molecular dock. The inhibitory site of hERG is a deep hydrophobic pocket. The π electrons of Tyrosine amino acids are notably prominent for the binding of blockers of hERG channel. [1, 47]. The central cavity of the hERG channel is electronegative, owing to four pore helices, which direct partial negative part toward the cavity [47].The binding site of Arbidol and hERG was highly consistent with previous studies on hERG channel blockers. The results showed that Arbidol bind to hERG with a binding energy of -2.25 kcal/mol. Arbidol interacted with the binding site by three different interactions, including π-π stacking interactions, hydrogen bonds, as well as hydrophobic interactions. Two hydrogen bonds were formed between Arbidol and hERG amino acid HIS-492. Besides hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic forces are established between molecules. The benzene group from Arbidol formed π-π stacking interactions with amino acid ALA-478 and TYR-497, however, the tertiary amine group of Arbidol formed interactions with TYR-475 residues (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Molecular dock of Arbidol with hERG

Compared with Arbidol, NA inhibitor Oseltamivir and RdRp inhibitor Remdesivir did not show hERG inhibition in patch clamp experiments (Fig. 5). The two compounds showed no inhibition on hERG ion channels.

Fig. 5.

Whole-cell currents recordings of Remdesivir and Oseltamivir

On account of the structure characteristics of Oseltamivir and Remdesivir, they did not involve the above molecular structure features of inhibitors. There is no continuous conjugate structure in Oseltamivir molecule. The Oseltamivir molecular skeleton has low rigidity and great flexibility, making it difficult to embed into the interior of hERG molecules and further form hydrophobic interactions with them. The molecular center of Remdesivir is flexible with strong polarity. Thiazide and benzene are two rigid structures connected through a flexible structure in the middle, but they are in distance, cannot form an effective negative electron cloud area.

Therefore, in the development process of HA inhibitors, rigid structural molecules with small molecular diameters containing polar groups should be avoided to weaken the inhibitory effect of hERG.

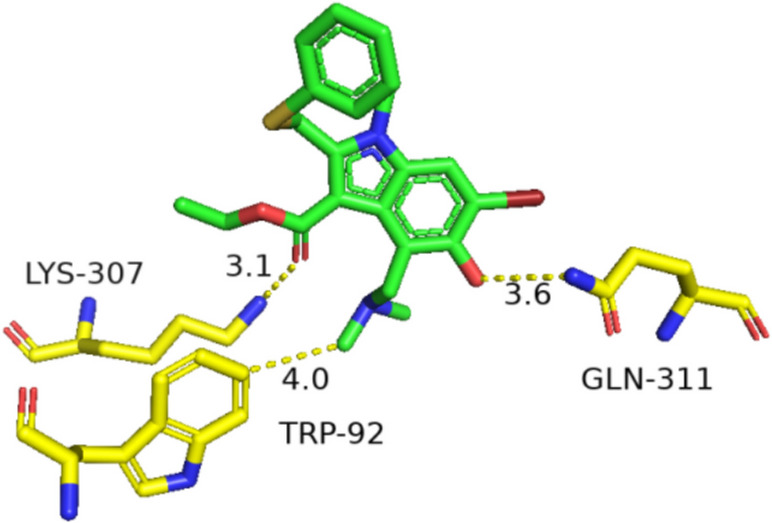

Arbidol RBD analysis of HA

The fusion peptides (FP) of the HA initiated the membrane fusion [26] of IAV. FP consisted of several large hydrophobic amino acids, especially glycine residues [26]. The RBD of Arbidol was the hydrophobic cavity close to the N-terminus of FP. Arbidol bound to the pocket, which was formed by the two helixes of HA and the N-terminus of the FP from an adjacent monomer. A series of ionized amino acid residues including lysine and glutamic acid were located around this pocket [14]. The key amino acids in the binding of Arbidol and HA were LYS-307, TRP-92, TYR-94, GLU-57, GLN-311 and ARG-54. Arbidol formed 2 hydrogen bonds with HA. One was with LYS307, the other was with GLN-311. Hydrophobic interactions were made between amino acids TRP-92, TYR-94, GLU-57 and ARG-54 and Arbidol (Fig. 6). The binding of Arbidol caused steric hindrance to block the low pH-induced rearrangement of HA membrane and the virus-host membrane fusion [6]. The hydrophobic cavity was also the RBD of inhibitors of other influenza virus ([21, 28, 29]). Therefore, this was a target with broad-spectrum inhibitory activity. Based on the crystal structures of Arbidol complexed with the influenza HA viral fusion glycoprotein from the pandemic 1968 H3N2 and contemporary 2013 H7N9 viruses, Arbidol binds within a conserved hydrophobic cavity at the interface of HA protomers in the upper stem region of the fusion domain. This binding stabilizes the pre-fusion conformation of HA, thereby inhibiting the conformational rearrangement essential for membrane fusion and subsequent viral infection[50]. In the Arbidol-H7/SH2 complex, Arbidol forms water-mediated hydrogen bonds with Lys310 of HA. The side chain of Glu97 packs against the thiophene ring surface of Arbidol, establishing hydrophobic interactions. In the Arbidol-bound H3/HK68 HA structure, the carboxyl group of Glu97 participates in salt bridge interactions with both Lys310 and Arg54[22]. Arbidol is a broad-spectrum antiviral agent that demonstrates inhibitory activity against both group 1 and group 2 influenza HA subtypes. While its binding site in group 2 HA has been previously identified, studies on the full-atomic model of the 2009 H1N1 influenza viral envelope have revealed a druggable pocket capable of accommodating Arbidol. This binding site exhibits spatial homology with the known Arbidol-binding site in group 2 HA, suggesting that Arbidol”s interaction with influenza HA may not be group-specific but rather conserved across different groups[24].

Fig. 6.

Molecular dock of Arbidol bind to HA

HA inhibitor screening

The binding free-energy was calculated to explain the nonpolar and polar interactions between the RBD and ligands [51]. The conformation with the lowest binding energy is regarded as the optimal conformation.

Glycyrrhetinic acid formed 1 H-bond with LYS-307 and 2 H-bonds with LYS-310. Paeoniflorin formed 2 H-bonds with GLU-57 and LYS-307. Daidzein formed 2 H-bonds with LYS-307 and VAL-55. Lauric acid formed 1 H-bonds with LYS-307. Magnolol formed 1 H-bonds with GLU-57. Pachymic acid formed 2 H-bonds with LYS-310 and LYS-307. Liquiritigenin formed 2 H-bonds with LYS-307 and LYS-58. Vanillic acid formed 2 H-bonds with LYS-310 and LYS-307. Palmitoleic acid formed 2 H-bonds with LYS-310 and LYS-307. Glycyrrhetinic acid has a very low binding energy in the process of binding with HA, second only to the first coptisine. At the same time, glycyrrhetinic acid and LYS307 can effectively form hydrogen bond interaction, which is very close to the binding site of Arbidol and HA. In addition, Pseudoephedrine interacts with two identical amino acid residues at the Arbidol binding site to form hydrogen bonds, and the binding energy is -5.26 kcal/mol. Pseudoephedrine and Arbidol have the closest RBD, while glycyrrhetinic acid has both site similarity and low binding energy, and the complex formed by binding is more stable. Therefore, pseudoephedrine and glycyrrhetinic acid were selected as candidate broad-spectrum anti HA inhibitors, and further evaluation of hERG ion channel inhibitory activity was conducted. The binding energy of 47 natural products with HA was shown (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Binding energy of natural products

The introduction of hydroxyl group allowing the direct hydrogen bond formation between Glycyrrhetinic acid and LYS-307 of HA residue. Glycyrrhetinic acid molecule is more flexible, which can better interact with surrounding amino acid residues and reduce binding energy. The protein–ligand binding free energy of Glycyrrhetinic acid were in agreement with experimental data, indicating that Glycyrrhetinic acid exhibits higher inhibitory potency against IAV.

From a structural analysis, Glycyrrhetinic acid molecules have high flexibility, no obvious rigid structure, and a large molecular diameter, making it difficult to infiltrate hERG inhibitory site. Pseudoephedrine molecules have a benzene ring structure and are prone to form π-π interactions, and the molecules are small and easily embedded in hydrophobic interaction pockets of hERG (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

a Chemical structures of Glycyrrhetinic acid and Pseudoephedrine, b Glycyrrhetinic acid binding to HA RBD

Glycyrrhetinic acid has lower binding energy than Arbidol to same cavity of HA, and is possible to provide a more stable combination. The molecular structure of Glycyrrhetinic acid is flexible, and it is not easy to form hydrophobic interactions with hERG. According to the results of molecular docking, Glycyrrhetinic acid has potential universal inhibitory effects on IAV but no hERG channels inhibition, making it highly valuable for the development of a broad-spectrum anti-IAV candidate.

Discussion

Arbidol exhibits broad-spectrum antiviral activity against IAV, other respiratory viruses, and even SARS-CoV-2 [54]. Arbidol interacts with all HA subtypes and inhibit the binding of the HA protein to sialic acid receptors [2]. Arbidol’s conserved binding site in the hydrophobic fusion peptide of HA explains its broad antiviral efficacy [22, 24]. Its widespread clinical use in some countries underscores its therapeutic value[45]. However, its tertiary amine and benzene ring moieties—structural hallmarks of hERG potassium channel inhibitors—induce dose-dependent hERG blockade (IC50 = 0.303 µM), leading to arrhythmia risk. This cardiotoxicity limitations severely restricts Arbidol’s therapeutic potential. With the outbreak of influenza epidemics, the current anti-influenza drugs targeting neuraminidase (oseltamivir, zanamivir) and proton M2 channel (amantadine, rimantadine) lead to drug resistance. Therefore, it is crucial to seek new antiviral agents acting on other viral targets [6]. The integrated data substantiate the well-established potential of Arbidol as a high-efficacy antiviral agent target for influenza virus [33, 48]. Based on the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of HA and Arbidol, small-molecule structural analogs targeting the Arbidol-binding pocket have been designed [50]. Arbidol exemplifies HA-stabilizing antivirals that suppress fusion through enhanced acid resistance. Researchers have designed and synthesized indole derivatives structurally related to Arbidol to discover novel antiviral agents [8]. Chemically synthesized small-molecule compounds designed based on SAR require high-throughput screening to validate their target bioactivity. In contrast, SAR-guided screening of potential bioactive molecules from pre-enriched natural product libraries significantly enhances the efficiency of discovering active compounds. In this study, based on the analysis of SAR [14] and binding energy of Arbidol with HA and hERG, natural active ingredients were screened for potential antiviral agents. Glycyrrhetinic acid shares a similar HA binding site with Arbidol but exhibits a lower binding free energy. The absence of coplanar hydrophobic aromatic rings in glycyrrhetinic acid’s structure renders it devoid of hallmark features associated with hERG channel inhibitors. As a fusion inhibitor targeting the conserved HA stem region, glycyrrhetinic acid demonstrates broad-spectrum potential by stabilizing prefusion HA conformation and blocking viral fusion.

Conclusion

Arbidol binds to the hydrophobic structural region of FP in HA, which is more conversed to many virus, making it the universal antiviral drug preparation. Arbidol exerts an inhibitory effect on hERG potassium ion channels by the patch clamp and molecular dock, which would lead to side effects such as arrhythmia. This should be paid close attention to in the clinical application of Arbidol.

Glycyrrhetinic acid was found to has lower binding energy than Arbidol on the premise of combining similar site. It is indicated that Glycyrrhetinic acid form a more stable binding with FP hydrophobic structure caves than Arbidol, and prevent FP mediated virus-host membrane fusion. The molecular structure of Glycyrrhetinic acid is more flexible, and it is not easy to form hydrophobic interaction with hERG channels. Glycyrrhetinic acid is the most potential compound for the developing of broad-spectrum antiviral drugs.

Authors’ contributions

Ran Yu designed the study, performed the research. Rong Shen and Wenting Fei analysed data, and Peng Li wrote the paper.

Funding

Authors wish to thank key projects of Beijing Polytechnic University (2024X007-KXZ), Major Science and Technology Projects of Beijing Polytechnic University (2024X005-KXD), plan for outstanding young talent of Beijing Polytechnic University (2023R008-JFQB), and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7254488) for financial support.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors confirm that the work described has not been published before. The publication has been approved by all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abdi A, AlOtaiby S, Badarin FA, Khraibi A, Hamdan H, Nader M. Interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with cardiomyocytes: insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms of cardiac injury and pharmacotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;146: 112518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed AA, Abouzid M. Arbidol targeting influenza virus A hemagglutinin; a comparative study. Biophys Chem. 2021;277: 106663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AlRawashdeh S, Chandrasekaran S, Barakat KH. Structural analysis of hERG channel blockers and the implications for drug design. J Mol Graph Model. 2023;120: 108405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amatsu S, Matsumura T, Zuka M, Fujinaga Y. Molecular engineering of a minimal E-cadherin inhibitor protein derived from Clostridium botulinum hemagglutinin. J Biol Chem. 2023;299: 102944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asai T, Adachi N, Moriya T, Oki H, Maru T, Kawasaki M, Suzuki K, Chen S, Ishii R, Yonemori K, Igaki S, Yasuda S, Ogasawara S, Senda T, Murata T. Cryo-EM Structure of K+-Bound hERG channel complexed with the blocker astemizole. Structure. 2021;29:203-12.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boonma T, Soikudrua N, Nutho B, Rungrotmongkol T, Nunthaboot N. Insights into binding molecular mechanism of hemagglutinin H3N2 of influenza virus complexed with arbidol and its derivative: a molecular dynamics simulation perspective. Comput Biol Chem. 2022;101: 107764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosco-Lauth A, Rodriguez A, Maison RM, Porter SM, Jeffrey Root J. H7N9 influenza A virus transmission in a multispecies barnyard model. Virology. 2023;582:100–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brancato V, Peduto A, Wharton S, Martin S, More V, Di Mola A, Massa A, Perfetto B, Donnarumma G, Schiraldi C, Tufano MA, de Rosa M, Filosa R, Hay A. Design of inhibitors of influenza virus membrane fusion: synthesis, structure–activity relationship and in vitro antiviral activity of a novel indole series. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:125–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown SK, Tseng Y-Y, Aziz A, Baz M, Barr IG. Characterization of influenza B viruses with reduced susceptibility to influenza neuraminidase inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 2022;200: 105280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Effectiveness of Seasonal Flu Vaccines from the 2009–2025 Flu Seasons. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu-vaccines-work/media/files/2025/05/Vaccine-Effectiveness-Chart-2025.xlsx.

- 11.Chauhan K, Singh P, Kumar V, Shukla PK, Siddiqi MI, Chauhan PMS. Investigation of Ugi-4CC derived 1H-tetrazol-5-yl-(aryl) methyl piperazinyl-6-fluoro-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid: synthesis, biology and 3D-QSAR analysis. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;78:442–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung C-F, Gorman J, Andrews SF, Rawi R, Reveiz M, Shen C-H, Wang Y, Harris DR, Nazzari AF, Olia AS, Julie Raab I, Teng T, Verardi R, Wang S, Yang Y, Chuang G-Y, McDermott AB, Zhou T, Kwong PD. Structure of an influenza group 2-neutralizing antibody targeting the hemagglutinin stem supersite. Structure. 2022;30:993-1003.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du R, Cui Q, Rong L. Competitive cooperation of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase during influenza A virus entry. Viruses. 2019;11:458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du R, Cheng H, Cui Q, Peet NP, Gaisina IN, Rong L. Identification of a novel inhibitor targeting influenza A virus group 2 hemagglutinins. Antiviral Res. 2021;186: 105013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friis S, Emma O, Kristina C, Richard K, Morten S. Current Clamp of Stem Cell Derived Cardiomyocytes on Qpatch. Biophysical Journal. 2014;106:764a. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govorkova EA, Takashita E, Daniels RS, Fujisaki S, Presser LD, Patel MC, Huang W, Lackenby A, Nguyen HT, Pereyaslov D, Rattigan A, Brown SK, Samaan M, Subbarao K, Wong S, Wang D, Webby RJ, Yen H-L, Zhang W, Meijer A, Gubareva LV. Global update on the susceptibilities of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors and the cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir, 2018–2020. Antivir Res. 2022;200: 105281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu K, Qian D, Qin H, Chang Cui WC, Fernando HA, Wang D, Wang J, Cao K, Chen M. A novel mutation in KCNH2 yields loss-of-function of hERG potassium channel in long QT syndrome 2. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 2021;473:219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauge SH, Dudman S, Borgen K, Lackenby A, Hungnes O. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses A (H1N1), Norway, 2007–08. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009. 10.3201/eid1502.081031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havare ÖzgeÇolakoğlu. Quantitative structure analysis of some molecules in drugs used in the treatment of COVID-19 with topological indices. Polycycl Aromat Compd. 2022. 10.1080/10406638.2021.1934045. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heindl MR, Böttcher-Friebertshäuser E. The role of influenza-A virus and coronavirus viral glycoprotein cleavage in host adaptation. Curr Opin Virol. 2023;58: 101303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman LR, Kuntz ID, White JM. Structure-based identification of an inducer of the low-pH conformational change in the influenza virus hemagglutinin: irreversible inhibition of infectivity. J Virol. 1997;71:8808–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadam RU, Wilson IA. Structural basis of influenza virus fusion inhibition by the antiviral drug Arbidol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017. 10.1073/pnas.1617020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King TI, Indapurkar A, Tariq I, DePalma R, Mistry S, Alvarez-Baron C, Ismaiel OA, Wu Wendy, Chiu K, Patel V, Rouse R, Strauss DG, Matta MK. Determination of five positive control drugs in hERG external solution (buffer) by LC-MS/MS to support in vitro hERG assay as recommended by ICH S7B. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2022;118: 107229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kochanek SE, Amaro RE. Markov state model of influenza hemagglutinin reveals structural basis for group 1 influenza inhibition by Arbidol. Biophys J. 2019;116:163a-a164. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokot M, Weiss M, Zdovc I, Anderluh M, Hrast M, Minovski N. Diminishing hERG inhibitory activity of aminopiperidine-naphthyridine linked NBTI antibacterials by structural and physicochemical optimizations. Bioorg Chem. 2022;128: 106087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai AL, Freed JH. The interaction between influenza HA fusion peptide and transmembrane domain affects membrane structure. Biophys J. 2015;109:2523–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei CL, Clerx M, Gavaghan DJ, Polonchuk L, Mirams GR, Wang K. Rapid characterization of hERG channel kinetics i: using an automated high-throughput system. Biophys J. 2019;117:2438–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leneva IA, Russell RJ, Boriskin YS, Hay AJ. Characteristics of arbidol-resistant mutants of influenza virus: Implications for the mechanism of anti-influenza action of arbidol. Antiviral Res. 2009;81:132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo G, Torri A, Harte WE, Danetz S, Cianci C, Tiley L, Day S, Mullaney D, Yu KL, Ouellet C, Dextraze P, Meanwell N, Colonno R, Krystal M. Molecular mechanism underlying the action of a novel fusion inhibitor of influenza A virus. J Virol. 1997;71:4062–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y, Wang Ye, Dong C, Gonzalez GX, Song Y, Zhu W, Kim J, Wei L, Wang B-Z. Influenza NP core and HA or M2e shell double-layered protein nanoparticles induce broad protection against divergent influenza A viruses. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology Biology and Medicine. 2022;40: 102479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marín-García, José. 'Chapter 17 - Post-Genomic Analysis of Dysrhythmias and Sudden Death.' in José Marín-García (ed.), Post-Genomic Cardiology (Second Edition) (Academic Press: Boston). 2014.

- 32.McNally BA, Pendon ZD, Trudeau MC. hERG1a and hERG1b potassium channel subunits directly interact and preferentially form heteromeric channels. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:21548–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nasser ZH, Swaminathan K, Müller P, Downard KM. Inhibition of influenza hemagglutinin with the antiviral inhibitor arbidol using a proteomics based approach and mass spectrometry. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Negami T, Araki M, Okuno Y, Terada T. Calculation of absolute binding free energies between the hERG channel and structurally diverse drugs. Sci Rep. 2019. 10.1038/s41598-019-53120-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padhi AK, Seal A, Khan JM, Ahamed M, Tripathi T. Unraveling the mechanism of arbidol binding and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2: insights from atomistic simulations. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;894: 173836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park KS, Seo YB, Lee JY, Im SJ, Seo SH, Song MS, Choi YK, Sung YC. Complete protection against a H5N2 avian influenza virus by a DNA vaccine expressing a fusion protein of H1N1 HA and M2e. Vaccine. 2011;29:5481–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridder BJ, Leishman DJ, Bridgland-Taylor M, Samieegohar M, Han X, Wu WW, Randolph A, Tran P, Sheng J, Danker T, Lindqvist A, Konrad D, Hebeisen S, Polonchuk L, Gissinger E, Renganathan M, Koci B, Wei H, Fan J, Levesque P, Kwagh J, Imredy J, Zhai J, Rogers M, Humphries E, Kirby R, Stoelzle-Feix S, Brinkwirth N, Rotordam MG, Becker N, Friis S, Rapedius M, Goetze TA, Strassmaier T, Okeyo G, Kramer J, Kuryshev Y, Wu Caiyun, Himmel H, Mirams GR, Strauss DG, Bardenet R, Li Z. A systematic strategy for estimating hERG block potency and its implications in a new cardiac safety paradigm. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020;394: 114961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saxena P, Zangerl-Plessl EM, Linder T, Windisch A, Hohaus A, Timin E, Hering S, Stary-Weinzinger A. New potential binding determinant for hERG channel inhibitors. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shugg T, Somberg JC, Molnar J, Overholser BR. ’Inhibition of human ether-A-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium current by the novel Sotalol analogue Soestalol. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6:756–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Son S, Ahn SB, Kim G, Jang Y, Ko C, Kim M, Kim SJ. Identification of broad-spectrum neutralizing antibodies against influenza A virus and evaluation of their prophylactic efficacy in mice. Antiviral Res. 2023;213: 105591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song J, Zhao J, Cai X, Qin S, Chen Z, Huang X, Li R, Wang Y, Wang X. Lianhuaqingwen capsule inhibits non-lethal doses of influenza virus-induced secondary Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;298: 115653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song Y, Zhu W, Wang Ye, Deng L, Ma Y, Dong C, Gonzalez GX, Kim J, Wei L, Kang S-M, Wang B-Z. Layered protein nanoparticles containing influenza B HA stalk induced sustained cross-protection against viruses spanning both viral lineages. Biomaterials. 2022;287: 121664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su H-C, Jung Feng I, Tang H-J, Shih M-F, Hua Y-M. Comparative effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in patients with influenza: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Infect Chemother. 2022;28:158–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tzarum N, de Vries RP, Peng W, Thompson AJ, Bouwman KM, McBride R, Yu Wenli, Zhu X, Verheije MH, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. The 150-loop restricts the host specificity of human H10N8 influenza virus. Cell Rep. 2017;19:235–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ul’yanovskii NV, Kosyakov DS, Sypalov SA, Varsegov IS, Shavrina IS, Lebedev AT. Antiviral drug umifenovir (Arbidol) in municipal wastewater during the COVID-19 pandemic: estimated levels and transformation. Sci Total Environ. 2022;805: 150380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang T, Sun J, Zhao Qi. Investigating cardiotoxicity related with hERG channel blockers using molecular fingerprints and graph attention mechanism. Comput Biol Med. 2023;153: 106464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang W, MacKinnon R. Cryo-EM Structure of the Open Human Ether-à-go-go-Related K+ Channel hERG. Cell. 2017;169:422-30.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Ding Y, Yang C, Li R, Du Qiuling, Hao Y, Li Z, Jiang H, Zhao J, Chen Q, Yang Z, He Z. Inhibition of the infectivity and inflammatory response of influenza virus by Arbidol hydrochloride in vitro and in vivo (mice and ferret). Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;91:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilasang C, Suttirat P, Chadsuthi S, Wiratsudakul A, Modchang C. Competitive evolution of H1N1 and H3N2 influenza viruses in the United States: a mathematical modeling study. J Theor Biol. 2022;555: 111292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wright ZVF, Wu NC, Kadam RU, Wilson IA, Wolan DW. Structure-based optimization and synthesis of antiviral drug Arbidol analogues with significantly improved affinity to influenza hemagglutinin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:3744–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yazdani M, Jafari A, Mahdian S, Namazi M, Gharaghani S. Rational approaches to discover SARS-CoV-2/ACE2 interaction inhibitors: pharmacophore-based virtual screening, molecular docking, molecular dynamics and binding free energy studies. J Mol Liq. 2023;375: 121345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang A, Chaudhari H, Agung Y, D’Agostino MR, Ang JC, Tugg Y, Miller MS. Hemagglutinin stalk-binding antibodies enhance effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors against influenza via Fc-dependent effector functions. Cell Reports Medicine. 2022;3: 100718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu H, Li X, Ren X, Chen H, Qian P. Improving cross-protection against influenza virus in mice using a nanoparticle vaccine of mini-HA. Vaccine. 2022;40:6352–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu Z, Lu Zhaohui, Xu Tianmin, Chen C, Yang G, Zha T, Lu Jianchun, Xue Y. Arbidol monotherapy is superior to lopinavir/ritonavir in treating COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:e21-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.