Abstract

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is a common occupational health issue in nursing. Nursing students, often insufficiently trained in ergonomic practices, are particularly vulnerable. Despite its long-term implications for workforce retention and professional well-being, the timing of onset and progression of LBP in this population remain unclear, especially in hospital-based clinical training. In this study, we investigated the onset, prevalence, intensity, and predictors of LBP among nursing students, specifically focusing on the impact of clinical training. Our aim was to inform the development of evidence-based strategies to improve nursing education and promote workforce sustainability.

Methods

A comparative, cross-sectional, online, questionnaire-based study was conducted among 194 third- and fourth-year nursing students engaged in clinical training at various hospitals. Logistic regression analyses were conducted for each independent variable, considering the Oswestry Disability Index as the dependent variable (< 12 vs. ≥12, where ≥ 12 indicates the presence of disability), to identify predictors of low back pain.

Results

The prevalence of low back pain increased significantly from 40.7% before nursing school to 75.3% during the past month of clinical training. Independent predictors of low back pain were clinical training-related stress (OR = 1.76, p <.003), and pre-existing musculoskeletal pain (neck/shoulder; OR = 3.05, p <.014). Single students experienced lower rates of LBP than married or divorced/widowed participants (OR = 0.138, p =.018). Pain intensity also increased significantly with daily activities, including lifting, walking, sitting, standing, and sleeping, following clinical training.

Conclusions

Hospital-based clinical training significantly increases the risk of LBP among nursing students, underscoring the need for evidence-based preventive strategies. Based on the study observations, specific interventions should include: (1) mandatory ergonomic training prior to and during clinical placements, (2) the integration of stress management programs into nursing curricula, and (3) routine musculoskeletal screening for the early identification of at-risk students. These strategies may improve physical resilience, reduce injury-related dropout, and support long-term workforce sustainability. Further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions and monitor LBP progression beyond graduation.

Keywords: Low back pain, Nursing students, Clinical training, Educational stress, Musculoskeletal disorders, Ergonomics training, Occupational health, Workforce sustainability

Background

Low back pain is one of the most prevalent health issues worldwide, causing substantial suffering and disability. It is the second most common global health problem, affecting approximately 577 million people, and a leading cause of years lived with disability [1, 2]. This growing burden has a considerable impact both on individuals and on healthcare systems, emphasizing the need for effective prevention and management strategies [3].

Among nurses, low back pain is highly prevalent owing to the physical demands of the profession, with global rates ranging from 40 to 90% and averaging approximately 55% across studies [4–7]. Among the musculoskeletal disorders affecting nurses, low back pain is the third most common [8]. Nurses experience back injuries at a rate six times higher than other healthcare workers, driven by tasks such as patient handling, prolonged standing, and repetitive movements [9, 10]. Additionally, factors such as sex and working hours are associated with the susceptibility to low back pain [11, 12]. Nursing-education programs should incorporate evidence-based, safe patient-handling techniques.

Nursing students, who are exposed to these occupational risks early in their training, face similar challenges but often lack adequate training to prevent low back pain, rendering them especially vulnerable to injury [13]. Furthermore, low back pain often persists or even intensifies as students transition to full-time roles. However, few studies have been conducted to examine whether low back pain begins during training or emerges only during full-time employment. The lack of comprehensive preventive measures and training in the prevention of low back pain exacerbates the risk, impacting not only the physical health of nursing students but also their motivation and commitment to the profession [1, 13, 14].

Although extensive research on low back pain has been conducted among registered nurses [6, 11, 13, 15, 16], a significant gap remains in understanding its onset and progression among nursing students, particularly in hospital settings. This gap may be owing to the transitional status of students, who are not yet fully part of the workforce but are exposed to similar physical demands. Owing to their exposure to physically demanding tasks and limited ergonomic training, nursing students are highly susceptible to low back pain. Addressing this gap by identifying its prevalence, contributing factors, and predictors is essential for the development of evidence-based preventive strategies. Integrating such measures into nursing curricula may enhance students’ physical preparedness, long-term well-being, and job satisfaction, ultimately improving patient care.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence, predictors, and impact of low back pain among nursing students before and during the last month of their clinical training.

Methods

Study design and ethics

A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the prevalence and predictors of low back pain among nursing students during hospital-based clinical placement. Data were collected from August 2023 to August 2024. The study comprised both exploratory objectives (e.g., examination of changes in pain intensity and identification of demographic predictors) and confirmatory testing of predefined hypotheses derived from existing literature. The study was designed to examine the impact of clinical training on low back pain among nursing students, exploring stress, pre-existing musculoskeletal pain, and demographic factors as potential predictors. Additionally, we assessed to what extent the intensity of low back pain varies across daily activities and investigated common coping mechanisms.

Eligible participants were third- or fourth-year nursing students engaged in clinical training. Pregnant students were excluded to prevent bias related to physical limitations during clinical work. Recruitment was facilitated through academic nursing departments at higher-education institutions in the Northern District of Israel. Students were invited to participate in an online survey via email or social media, and responses were collected through the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, Dublin, Ireland).

To ensure data integrity and minimize potential duplications, participants were restricted to a single response per question. Informed consent was obtained electronically before the participant could access the questionnaire, and all responses were anonymized to maintain confidentiality. The study protocol was developed in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Departmental Research Ethics Committee of Max Stern Academic College of Emek Yezreel (approval number: YVC EMEK 2023-94). Furthermore, we adhered to the guidelines of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement to ensure rigorous reporting.

Description of the instrument

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were assessed using a questionnaire adapted from a validated Hebrew instrument previously shown to reliably measure psychometric properties in studies on low back pain [17, 18]. The questionnaire included variables such as sex, age, height, weight, body mass index, marital status, and year of study (third or fourth year). Health-related behaviors, including smoking status and engagement in physical activity during leisure time (yes/no), were also documented. The amount of physical activity was categorized as more than 150 min per week, 75 to 150 min per week, or less than 75 min per week.

Back-pain characteristics

Participants were asked to indicate the presence and frequency of low back pain at three specific time points: over the course of their lifetime (prior to commencing nursing school), the previous year, and over the past month, corresponding to the period of clinical experience. As all of these items were completed at the same time, the study was cross-sectional rather than longitudinal. Low back pain was defined as any form of discomfort or pain localized between the lower ribs and the hips, with or without radiation to the lower extremities, consistent with established diagnostic criteria [19].

Furthermore, participants were asked whether they had ever been hospitalized for back pain, whether low back pain had impacted their daily activities over the past year, and how many days they had been disabled due to low back pain (categorized as 0, 2–7, 8–30, or > 30 days). Participants were also asked whether and how frequently they used medication for back pain (daily, weekly, or monthly), and whether they experienced an exacerbation of pain during clinical placement. The questionnaire also included items on the presence of pain in additional anatomical regions, such as the neck and shoulders (yes/no), and other musculoskeletal-pain conditions (yes/no).

Measurement tools

The oswestry disability index

Participants rated 10 items on a five-point scale from 0 (“no pain”) to 5 (“worst pain imaginable”), with a maximum score of 50. Higher scores indicate greater disability; as determined in a previous study, scores ≥ 12 were deemed to indicate low back pain with disability, whereas scores < 12 were deemed to indicate low back pain without disability [20]. In this study, the Oswestry Disability Index demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90).

Stress index

This index was used to assess participants’ perceived stress over the past month in four domains: educational (clinical training), family, personal, and social. Participants rated the question “During the past month, how much study-related stress have you experienced?” on a four-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all” to 4 = “to a very large extent” [17, 21]. The questionnaire has demonstrated validity and internal reliability [20].

Pain intensity

Pain intensity was measured using the visual analog scale, a 10-cm line with endpoints labeled “no pain” and “pain as bad as can be.” Participants were instructed to place a mark on the line corresponding to their current pain intensity. The visual analog scale is widely regarded as a reliable and valid tool to quantify pain owing to its simplicity and robust psychometric properties [22].

Data analysis and study sample

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the background characteristics and key study variables. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations, along with ranges, whereas categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. No values were missing in the study dataset. The internal consistency of the study variables was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha.

The frequency of low back pain at the three time points was compared using repeated-measures analysis of variance, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Changes in pain characteristics before and during clinical training were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, given its suitability for paired, non-parametric data. The association between stress factors and low back pain was assessed using the chi-square test, and Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used to examine the relationship between the stress index and the severity of low back pain.

Simple logistic regression analyses were conducted for each independent variable, considering the Oswestry Disability Index as the dependent variable (categorized as < 12 vs. ≥12). Subsequently, a multiple logistic regression model was employed to determine the odds ratios for moderate back-related disability. Variables that did not demonstrate a significant relationship with the Oswestry Disability Index in the preliminary analyses were excluded from the final model. All tests were two-tailed, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

The required sample size to achieve a minimum odds ratio of 1.5 with logistic regression, α = 0.05, and power of 0.80 was calculated with G*Power 3.1 (Heinreich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany) [23]. The required sample size for a 95% confidence interval was 280. However, our sample size was only 194. We address this further in the limitations section.

Results

Sociodemographic and health characteristics

The questionnaire was sent to 380 students, and 194 students responded, all of whom were recruited for the study. Thus, the response rate was 51.1%. Table 1 presents their sociodemographic, academic, and behavioral characteristics. The sample was predominantly female (64.9%) and comprised mainly young adults, with a mean age of 26.4 (standard deviation = 5.2) years. The majority of participants had never been married (75.8%) and were enrolled in their fourth year of academic study (65.5%). The mean body mass index was 24.6 (standard deviation = 4.2) kg/m2, within the healthy range, according to standard classifications. The vast majority of participants were nonsmokers and engaged in regular physical activity during their leisure time (both 72.7%).

Table 1.

Demographic and health-related characteristics according to the ODI

| Variable | Total (N = 194) |

ODI < 12 (n = 141) | ODI ≥ 12 (n = 53) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 26.4 ± 5.2 (20–53) | 26.7 ± 5.1 | 25.7 ± 5.3 | 0.95 (0.88–1.03) | 0.995 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 126 (64.9) | 93 (73.8) | 33 (26.2) | 0.83 (0.43–1.61) | 0.588 |

| Male | 68 (35.1) | 48 (70.6) | 20 (29.4) | 1 (reference) | |

| Marriage status, n (%) | |||||

| Single | 147 (75.8) | 116 (78.9) | 31 (21.1) | 0.16 (0.04–0.71) | 0.016 |

| Married/Cohabiting | 39 (20.1) | 22 (56.4) | 17 (43.6) | 0.46 (0.10–2.21) | 0.336 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 8 (4.1) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 1 (reference) | |

| Year of studies, n (%) | |||||

| Third | 67 (34.5) | 52 (77.6) | 15 (22.4) | 1 (reference) | 0.264 |

| Fourth | 127 (65.5) | 89 (70.1) | 38 (29.9) | 1.48 (0.74–2.95) | |

| Lifestyle Behaviors | |||||

| Physical activity, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 141 (72.7) | 104 (73.8) | 37 (26.2) | 0.82 (0.41–1.65) | 0.583 |

| No | 53 (27.3) | 37 (69.8) | 16 (30.2) | 1 (reference) | |

| Physical activity (minutes per week) (n = 141) | |||||

| More than 150 min | 40 (28.4) | 33 (82.5) | 7 (17.5) | 0.45 (0.16–1.28) | 0.135 |

| 75–150 min | 57 (40.4) | 41 (71.9) | 16 (28.1) | 0.84 (0.36–1.97) | 0.681 |

| < 75 min + “don’t remember” | 44 (31.2) | 30 (68.2) | 14 (31.8) | 1 (reference) | |

| Health-Related Characteristics | |||||

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.6 ± 4.2 (17.6–36.9) | 24.2 ± 4.0 | 25.6 ± 4.4 | 1.08 (1.00-1.16) | 0.046 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||

| Ever smoker | 53 (27.3) | 35 (66.0) | 18 (34.0) | 1.56 (0.78–3.09) | 0.205 |

| Never smoker | 141 (72.7) | 106 (75.2) | 35 (24.8) | 1 (reference) | |

| Stress factors, mean ± standard deviation | |||||

| Educational (clinical training) | 2.67 ± 1.01 | 2.52 ± 1.00 | 3.07 ± 0.92 | 1.80 (1.23–2.54) | < 0.001 |

| Family | 2.18 ± 0.97 | 2.11 ± 0.98 | 2.37 ± 0.92 | 1.33 (0.96–1.84) | 0.085 |

| Personal | 2.51 ± 0.92 | 2.50 ± 0.93 | 2.56 ± 0.92 | 1.08 (0.76–1.52) | 0.683 |

| Social | 2.07 ± 0.95 | 1.99 ± 0.93 | 2.26 ± 0.72 | 1.35 (0.97–1.87) | 0.078 |

| Stress Index | 2.36 ± 0.73 | 2.28 ± 0.72 | 2.57 ± 0.71 | 1.74 (1.12–2.72) | 0.014 |

A higher ODI indicates greater disability

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (range) unless otherwise indicated

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index

Low-back-pain characteristics over time

Back-pain characteristics were analyzed across multiple time points in terms of their prevalence and impact (Table 2). Prior to their commencement of nursing studies, 50.3% (n = 79) had experienced back pain, and 8.1% (n = 13) had been hospitalized for this condition. Notably, all participants who had been hospitalized for back pain were currently in their fourth year of study, suggesting a potential cumulative risk. Additionally, the occurrence of back pain prior did not differ according to the current year of study (47.4% of third-year students vs. 52.0% of fourth-year students; p =.577).

Table 2.

Pain-related characteristics according to the ODI

| Variable | Total (N = 194) |

ODI < 12 (n = 141) | ODI ≥ 12 (n = 53) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current pain VAS score | 4.1 ± 2.3 (1–10) | 3.6 ± 2.2 | 5.2 ± 2.1 | 1.38 (1.18–1.61) | < 0.001 |

| Medication for back pain, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 43 (22.2) | 14 (32.6) | 29 (67.4) | 10.96 (5.06–23.74) | < 0.001 |

| No | 151 (77.8) | 127 (84.1) | 24 (15.9) | 1 (reference) | |

| Additional body region with pain, n (%) | |||||

| Shoulder & neck | 55 (28.4) | 34 (61.8) | 21 (38.2) | 3.71 (1.60–8.57) | 0.002 |

| Other body region | 62 (32.0) | 41 (66.1) | 21 (33.9) | 3.07 (1.34–7.03) | 0.008 |

| None | 77 (39.7) | 66 (85.7) | 11 (14.3) | 1 (reference) | |

| Back pain increased with increased frequency of clinical rotation in departments, n (%)(n = 154) | |||||

| Yes | 102 (66.2) | 69 (67.6) | 33 (32.4) | 2.63 (1.11–6.22) | 0.028 |

| No | 52 (33.8) | 44 (84.6) | 8 (15.4) | 1 (reference) | |

| Back pain before entering nursing school, n (%)(n = 157) | |||||

| Yes | 79 (50.3) | 57 (72.2) | 22 (27.8) | 0.92 (0.46–1.84) | 0.820 |

| No | 78 (49.7) | 55 (70.5) | 23 (29.5) | 1 (reference) | |

| Hospitalized for back pain, n (%)(n = 161) | |||||

| Yes | 13 (8.1) | 3 (23.1) | 10 (76.9) | 11.62 (3.02–44.67) | < 0.001 |

| No | 148 (91.9) | 115 (77.7) | 33 (22.3) | 1 (reference) |

A higher ODI indicates greater disability

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (range) unless otherwise indicated

CI, confidence interval; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; VAS, visual analog scale

During the previous year, 54.6% (n = 106) of participants had experienced persistent back pain (Table 2). Nearly half of the participants (48.5%, n = 94) indicated that the pain had significantly interfered with their daily activities, with 10 students reporting more than 7 days of disability. Furthermore, 35.1% (n = 68) had sought medical treatment for back pain, and 32.0% (n = 62) reported using medication to alleviate their symptoms, with a substantial proportion (29.4%, n = 57) taking medication on a daily basis.

Considering back pain experienced within the past month, the prevalence increased to 75.3% (n = 146), with 22.2% (n = 43) reporting the use of medication to manage their pain (Table 2). Interestingly, the prevalence of back pain in the preceding month did not differ between third- (73.1%) and fourth-year students (75.6%; p =.708). However, 66.2% (n = 102) responded affirmatively to the question, “Do you feel that your back pain worsens as the frequency of your rotations in different departments increases?” This result highlights the potential worsening of low back pain with increased time spent in hospital departments during clinical training.

Multiple-comparison analyses revealed differences between each of the assessed time points (before commencing studies vs. previous year: p =.026; previous year vs. past month: p <.001; before commencing studies vs. past month: p <.001). The prevalence of back pain reportedly increased over time (Fig. 1; F = 58.87, degrees of freedom = 1,193, p <.001). Significant changes in pain intensity were observed across various activities over time, according to the Oswestry Disability Index questionnaire (Table 3) [24]. For example, 56.5% of the students reported experiencing no pain during heavy lifting before their clinical training, whereas only 26.4% reported being pain-free during their training (p <.001). Similarly, the proportion of students being able to walk indefinitely without back pain decreased from 75.6% before their training to 51.3% during their training (p <.001).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of reported low back pain over time

Table 3.

Pain intensity scores across daily activities before and during clinical training based on the ODI

| Before clinical training | During clinical training | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean ± SD Median (Q1-Q3) |

n (%) | Mean ± SD median (Q1-Q3) | p | |

| Lifting heavy weights | |||||

| Without extra pain | 110 (56.7) |

0.9 ± 1.3 0 (0–1) |

52 (26.8) |

1.5 ± 1.4 1 (0–3) |

< 0.001 |

| With extra pain | 44 (22.7) | 68 (35.1) | |||

| Can manage if they are conveniently positioned | 11 (5.7) | 25 (12.9) | |||

| Can lift light weights | 14 (7.2) | 27 (13.9) | |||

| Can lift very light weights | 9 (4.6) | 14 (7.2) | |||

| Unable to lift anything | 6 (3.1) | 8 (4.1) | |||

| Pain when walking | |||||

| Without limit | 147 (75.8) |

0.4 ± 0.9 0 (0–0) |

100 (51.5) |

1.0 ± 1.3 0 (0–2) |

< 0.001 |

| Up to a quarter of an hour | 29 (14.9) | 42 (21.6) | |||

| Up to 800 m–10 min | 9 (4.6) | 23 (11.9) | |||

| Up to 400 m–5 min | 5 (2.6) | 19 (9.8) | |||

| With crutches/cane | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.6) | |||

| When the pain stops | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.6) | |||

| Pain when sitting | |||||

| Without restriction | 140 (72.2) |

0.5 ± 0.9 0 (0–1) |

74 (38.1) |

1.3 ± 1.2 1 (0–2) |

< 0.001 |

| Comfortable chair without restriction | 28 (14.4) | 38 (19.6) | |||

| Up to an hour | 14 (7.2) | 52 (26.8) | |||

| Up to half an hour | 8 (4.1) | 20 (10.3) | |||

| Up to 10 min | 4 (2.1) | 9 (4.6) | |||

| Can’t sit | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Pain when standing | |||||

| Without restriction | 130 (67.0) |

0.5 ± 0.9 0 (0–1) |

48 (24.7) |

1.4 ± 1.1 1 (0–2) |

< 0.001 |

| With slight pain | 39 (20.1) | 68 (35.1) | |||

| Up to an hour | 14 (7.2) | 49 (25.3) | |||

| Up to half an hour | 8 (4.1) | 18 (9.3) | |||

| Up to 10 min | 1 (0.5) | 10 (5.2) | |||

| Can’t stand | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Pain during sleep | |||||

| Without restriction | 146 (75.3) |

0.4 ± 0.8 0 (0-0.5) |

86 (44.3) |

0.9 ± 1.1 0 (0–1) |

< 0.001 |

| Only with painkillers | 30 (15.5) | 62 (32.0) | |||

| With painkillers- sleep less than 6 h | 12 (6.2) | 28 (14.4) | |||

| With painkillers- sleep less than 4 h | 3 (1.5) | 13 (6.7) | |||

| With painkillers- sleep less than 2 h | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) | |||

| Can’t sleep | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | |||

P values are based on the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test

Q, quartile; SD, standard deviation

Association between stress and low back pain

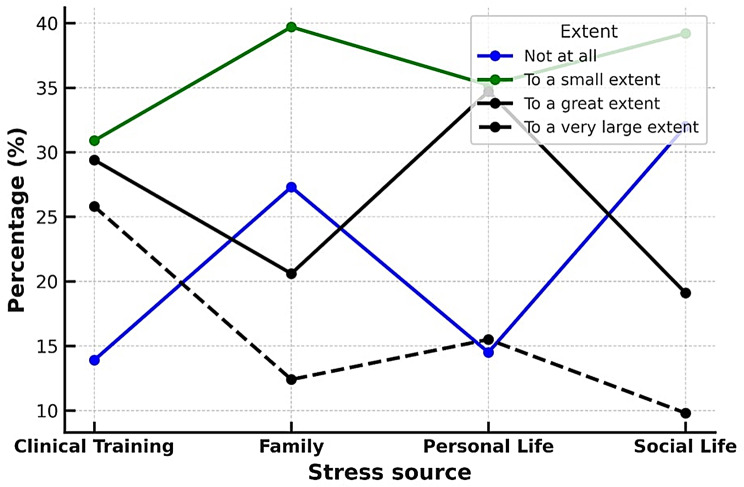

According to the responses, the highest level of stress (“to a very large extent”) was most frequently associated with clinical experience (26% of students). Such a high level of stress was reported less frequently for personal (15.5%), family (12.4%), and social (9.8%) life (Fig. 2). The stress index had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.747, indicating good internal consistency. The mean score was 2.4 (standard deviation = 0.7), and the median score was 2.3 (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Sources and extent of stress

Stress was significantly associated with the presence of back pain during the past month. Among students reporting high levels of clinical experience-related stress (stress index = 4), 82% experienced back pain compared with only 44% of those reporting no clinical experience-related stress (χ2 = 16.3, degrees of freedom = 3, p <.001). No significant association existed between back pain and stress levels related to family, personal, or social life (Table 1).

The overall stress index (combining all four domains) was higher among students who reported experiencing back pain during the past month than that among those who reported an absence of such pain (2.4 ± 0.7 vs. 2.1 ± 0.7, p =.014). Moreover, positive correlations were observed between back-pain intensity (visual analog score) in the past month and stress levels related to clinical experience (r =.297, p <.001), family life (r =.151, p =.036), and personal life (r =.189, p =.008). Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between back-pain intensity and the overall stress index (r =.258, p <.001). However, no association was observed between back-pain intensity and social stress levels (Table 1).

Disability due to back pain and predictors

In the study cohort, 27.3% of students (n = 53) reported experiencing disability owing to back pain (Oswestry Disability Index ≥ 12), whereas 72.7% (n = 141) reported not experiencing such (Tables 1 and 2). Comparative analysis revealed significant associations between the Oswestry Disability Indices and various demographic and clinical characteristics (Tables 1 and 4). Marital status was a significant risk factor, with single students exhibiting a significantly lower risk of back pain-related disability than those who were married/cohabiting or divorced/widowed. A higher body mass index was also associated with an increased risk of disability. Furthermore, students reporting back pain-related disability were more likely to use medications for back pain, reported higher visual analog scale scores, and were more likely to experience additional pain in the shoulder and neck.

Table 4.

Predictors of Oswestry disability indices ≥ 12 via multiple logistic regression

| Variable | Categories | B | SE | Wald | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | Continuous (per kg/m2) | 0.054 | 0.042 | 1.651 | 1.055 | 0.972–1.145 | 0.198 |

| Marital status | Widowed/Divorced | 1.98 | 0.835 | 5.618 | 7.242 | 1.408–37.238 | 0.018 |

| Married | 1.066 | 0.412 | 6.703 | 2.903 | 1.296–6.504 | 0.010 | |

| Single | - | - | - | 1.0 | - | - | |

| Additional body region with pain | Neck/Shoulder | 1.115 | 0.456 | 6.002 | 3.049 | 1.248–7.449 | 0.014 |

| Other | 0.92 | 0.454 | 4.095 | 2.508 | 1.030–6.111 | 0.043 | |

| None | - | - | - | 1.0 | - | - | |

| Clinical training-related stress | Continuous (per point) | 0.568 | 0.191 | 8.863 | 1.765 | 1.213–2.567 | 0.003 |

| Increased back pain with increased frequency of clinical rotation between departments | -0.945 | 0.570 | 2.751 | 0.389 | 0.128–1.177 | 0.097 | |

| Constant | - | -2.963 | 1.432 | 4.287 | 0.052 | - | 0.039 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error of B

The model incorporated background variables, stress, and pain (N = 194)

The stress index, particularly for stress related to clinical experience, was strongly associated with the odds of back pain-related disability, suggesting that elevated stress levels increased the likelihood of experiencing disability. In contrast, no significant associations were discovered between back pain-related disability and other variables, such as the year of study, smoking status, engaging in physical activity, and weekly hours of physical activity (Table 1).

Table 4 presents the results of the final logistic regression model for the prediction of back pain-related disability (Oswestry Disability Index ≥ 12). Key covariates included educational stress, body mass index, marital status, increase in back pain with increased frequency of clinical rotation between departments, and pain in other anatomical regions. The logistic regression model was statistically significant (χ² [degrees of freedom = 5] = 34.53, p <.001), accounting for approximately 24% of the variance in Oswestry Disability Index scores (Nagelkerke’s R² = 0.236). Among the predictors of disability were:

•higher levels of clinical training-related stress (odds ratio = 1.765, p =.003),

•being widowed/divorced (odds ratio = 7.242, p =.018),

•being married (odds ratio = 2.903, p =.010), and.

•pain in the neck/shoulder (odds ratio = 3.049, p =.014).

In contrast, body mass index (odds ratio = 1.055, p =.198) and increased back pain with an increased frequency of clinical rotation between departments (odds ratio = 0.389, p =.097) were not significant predictors in this model (Table 4).

Discussion

This study provided valuable insights into the prevalence and progression of low back pain among nursing students undergoing clinical training. The prevalence of low back pain increased significantly as students advanced in their studies, with 75.3% experiencing it in the past month, compared with 54.6% in the previous year and 40.7% before starting their nursing education. These results align with those of previous studies, such as those by Moodley et al. [25], who reported that > 80% of nursing students experienced low back pain during clinical training, and Mitchell et al. [16], who identified low back pain as a common musculoskeletal issue among this group. However, a cohort study of baccalaureate nursing students in America revealed no significant changes in the prevalence of low back pain over a 16-month period, highlighting the variability in progression of low back pain across educational settings [15].

In the current study, we identified three key factors associated with the occurrence of low back pain among nursing students: being married or divorced/widowed, experiencing pain in other body regions (particularly the neck and shoulders), and experiencing stress related to clinical training. These risk factors can be broadly categorized into two groups: individual and occupational factors, and the latter can be further divided into physical and psychosocial components [14].

A potential physical occupational risk factor identified in this study was the increased frequency of rotations across different hospital departments, with 66.2% of participants (n = 102) reporting that their back pain worsened as their clinical rotations increased. However, it was not an independent risk factor. Additionally, the participants in our study reported that their low back pain intensified during clinical training compared with the pre-training period, particularly during physically demanding activities such as heavy lifting, but also during walking, standing, sitting, and even sleeping. These results align with those previously reported. Nurses in hospital settings are exposed to various occupational risk factors for low back pain, including prolonged standing and disrupted sleep and eating patterns owing to shift work [14, 26].

Psychosocial factors, particularly stress, play significant roles in the development of low back pain. In this study, clinical training-related stress was a key predictor, with higher stress levels associated with severe low back pain (odds ratio = 1.765, p =.003). This aligns with prior research, such as that by Jradi et al. [14], who reported a strong link between workplace stress and musculoskeletal pain in healthcare workers. Stress can increase muscle tension and alter pain perception, compounding physical strain on the spine, particularly in demanding clinical settings [21]. In a recent scoping review, stress caused by coronavirus disease 2019-related restrictions significantly impacted the psychological well-being of nursing students, with higher levels of resilience serving as a protective factor against its negative effects [27]. Combined with mechanical strain and other psychological factors, such as anxiety, stress contributes to the development and persistence of low back pain. Initial injuries may also become chronic owing to stress-related effects on the central nervous system [28], emphasizing the need to address psychosocial factors in the prevention and management of low back pain for nursing students.

A higher body mass index was identified as a predictor of low back pain in the univariate analysis (odds ratio = 1.08, p =.046). This aligns with previous results [29, 30]. Samaei et al. [30]. suggested that excess abdominal weight increases spinal pressure, potentially leading to chronic lower-back spasms. Upon multivariable logistic regression analysis in this study, body mass index was no longer a significant predictor of low back pain. Thus, its influence may be mediated or confounded by other factors, such as stress, marital status, or pre-existing musculoskeletal conditions, which were independent risk factors in the study. Although some studies support a direct association between body mass index and low back pain due to mechanical stress, others did not [31, 32], possibly owing to differences in population characteristics, measurement methods, or other risk factors. This study indicates that body mass index is likely not a standalone risk factor for low back pain; it may play a context-dependent role in terms of additional personal and occupational factors.

In this study, a history of musculoskeletal pain, especially in the neck, shoulders, and lower back, was a strong predictor of low back pain during clinical training. Participants with prior neck or shoulder pain had an increased risk of low back pain (odds ratio = 3.05, p =.014), and those who were hospitalized for back pain (n = 13, 8%) were even more likely to experience recurrence (odds ratio = 11.62, p <.001). This aligns with the results of previous studies in which individuals with prior musculoskeletal pain, particularly low back pain, were more prone to future episodes [18, 32, 33]. These results highlight the need for early intervention and ongoing management to prevent the recurrence of low back pain.

In this study, being single was a protective factor against low back pain compared with being married or divorced/widowed (odds ratio = 0.14, p =.018). Married participants had higher odds of low back pain than single individuals but seemingly lower odds than divorced/widowed participants (odds ratio = 0.40, p =.297). Previous studies yielded mixed results regarding marital status and low back pain; some revealed no significant association [30, 32], whereas others have suggested that social support may help reduce stress and musculoskeletal pain [34]. The protective effect of being single in our study may be related to this group being younger on average (26 years) and having fewer familial demands such as parenting that are linked to low back pain. Single individuals may also have more flexibility to maintain a healthy lifestyle and face fewer household stressors, potentially reducing their risk of chronic pain.

In our study, several factors traditionally associated with low back pain, including sex, age, smoking status, and engaging in physical activity during leisure time, did not emerge as significant predictors. The relatively young age of our participants (26.4 ± 5.2 years) likely explains the lack of association with most of these factors, as the long-term effects of aging, smoking, and physical inactivity on spinal health may not yet be evident in this group. Age-related spinal degeneration is often associated with low back pain in older populations [30, 34]; however, age was not a significant factor in our analysis (p =.995). This aligns with the results of Dlungwane et al. [35], who reported a higher prevalence of low back pain among nurses aged 30–39 years, but not among those aged 40 years or older, compared with those younger than 30.

Similarly, smoking, often linked to an increased risk of low back pain owing to nicotine-induced vasoconstriction and reduced blood flow to the muscles and intervertebral discs, was not significantly associated with low back pain in our study. This aligns with the results of previous studies [29, 32] and may be attributed to the younger and healthier profile of our sample, as mentioned above.

Several studies have suggested that engaging in physical activity during leisure time may protect individuals against chronic back pain [18], but our study did not bear this out. This aligns with the results of Sitthipornvorakul et al. [36], who reported conflicting results regarding the relationship between physical activity and low back pain. The lack of an association in our study may be due to the relative youth of our sample, as mentioned above. Additionally, occupational stressors might have a more immediate impact on low back pain, overshadowing any protective effects of physical activity.

Sex, which is frequently associated with low back pain owing to physiological and structural differences between men and women [1, 30, 34], did not emerge as a significant predictor in our logistic regression model. This may be owing to the stronger influence of other factors such as marital status, pain in other body regions, and stress during clinical training, which were independent predictors of low back pain in our study. Additionally, our sample was predominantly female (64.9%), and the limited variability in the sex distribution might have contributed to the lack of a significant effect of sex.

To strengthen the practical implications of our observations, modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for low back pain must be distinguished. Modifiable factors identified in this study include clinical training–related stress, physical workload during clinical rotations, and certain lifestyle behaviors. These can be targeted through preventive strategies such as ergonomic education and stress management programs. In contrast, non-modifiable factors, such as a history of musculoskeletal pain and marital status, can help to identify students at higher risk but require different management approaches.

Limitations of the study

This study had a comparative, retrospective design with a relatively small sample (N = 194), which might have limited its generalizability. However, a post-hoc analysis showed that the statistical power was 79.6%, close to the commonly accepted threshold. The sample size was constrained by the number of nursing students in clinical training during the study period. Despite this, our sample was likely representative, as a systematic review by Menzel et al. [15] demonstrated that most nursing students are young adults, predominantly female, and often single. The response rate (51.05%) was lower than ideal but comparable to similar nursing-education studies (28–36%) [16, 37], reflecting the challenges of engaging busy students. One study had a high response rate (87%) [27]. Potential biases of our study include the non-response bias, as the characteristics of non-respondents remain unknown; social desirability bias, despite the fact that we ensured anonymity; and recall bias, as self-reported symptoms may be influenced by cognitive or emotional factors.

This study could not establish causality, and we did not monitor the progression of low back pain over time. A longitudinal study would provide deeper insights into its development throughout nursing education. Additionally, confounding factors such as specific clinical duties, workload intensity, and ergonomic conditions were not assessed but should be considered in future research. Lastly, self-reported data might have introduced subjectivity in the severity assessment, limiting result interpretation.

Implications for nursing profession

The nursing profession has a duty to safeguard students from occupational risks, even during their brief exposure to patient-handling tasks. To mitigate low back pain, nursing programs should integrate evidence-based strategies, including stress management, healthy-lifestyle promotion, early musculoskeletal screening, and safe patient-handling techniques. Based on the observations of this study, ergonomic training should be formally embedded into nursing curricula through both theoretical instruction and hands-on workshops during clinical preparation. This could include simulations of lifting and positioning, education on posture awareness, and training in the use of assistive devices [38, 39]. Students should also be empowered to refuse unsafe lifts, and clinical settings should be equipped with adequate mechanical-lifting devices to reduce strain [12, 15]. Furthermore, tailored social support may help alleviate psychological stressors that contribute to low back pain.

By implementing these preventive measures, the nursing profession can foster a healthier, more resilient workforce, ultimately enhancing students’ long-term well-being and career sustainability [7]. Future research should be conducted to assess the long-term effectiveness of such interventions and investigate additional factors that may contribute to low back pain among nursing students.

Conclusions

This study contributes to a deeper understanding of the factors influencing low back pain among nursing students during clinical training. Our findings highlight the important role of clinical training-related stress and pre-existing musculoskeletal conditions, underscoring the need for targeted preventive interventions in nursing-education programs. Addressing these risks through structured interventions in nursing curricula, such as ergonomic training, stress management, and early screening, may enhance students’ physical well-being, clinical competency, and long-term retention in the profession. Future research should be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of such interventions over time and explore additional contributing factors, including the influence of institutional support, workload variations, and the transition into professional practice.

The frequency of low back pain at the three time points was compared using repeated-measures analysis of variance, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The prevalence of back pain reportedly increased over time (F = 58.87, degrees of freedom = 1,193, p <.001).

According to the responses, the highest level of stress (“to a very large extent”) was most frequently associated with clinical experience (26% of students). Such a high level of stress was reported less frequently for personal (15.5%), family (12.4%), and social (9.8%) life.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants in our study.

Abbreviations

- LBP

Low back pain

Author contributions

AD, TS, JA, and SO contributed to the conceptualization of the study. Data curation was performed by AD, JA, SO and TS. Formal analysis was conducted by AD and SO. Funding acquisition was managed by AD and SO. Investigation was carried out by AD, TS, JA, and SO. The methodology was developed by AD and SO. Project administration was handled by AD, TS, SO and JA. Resources were provided by AD, TS, JA, and SO. Software was managed by AD, TS, JA, and SO. The study was supervised by AD and SO. Validation and visualization were performed by AD and SO. The original draft was prepared by AD and SO, and the manuscript was reviewed and edited by AD and SO.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained electronically before the participant could access the questionnaire, and all responses were anonymized to maintain confidentiality. The study protocol was developed in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Departmental Research Ethics Committee of Max Stern Academic College of Emek Yezreel (approval number: YVC EMEK 2023-94). Furthermore, we adhered to the guidelines of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement to ensure rigorous reporting.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rezaei B, Mousavi E, Heshmati B, Asadi S. Low back pain and its related risk factors in health care providers at hospitals: a systematic review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;70:102903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu A, March L, Zheng X, Huang J, Wang X, Zhao J, et al. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391:2356–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almaghrabi A, Alsharif F. Prevalence of low back pain and associated risk factors among nurses at King Abdulaziz university hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis KG, Kotowski SE. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders for nurses in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and home health care: a comprehensive review. Hum Factors. 2015;57:754–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair DRS. Prevalence and risk factors associated with low back pain among nurses in a tertiary care hospital in South India. Int J Orthop Sci. 2020;6:301–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azizpour Y, Delpisheh A, Montazeri Z, Sayehmiri K. Prevalence of low back pain in Iranian nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nurs. 2017;16:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziam S, Lakhal S, Laroche E, Lane J, Alderson M, Gagné C. Musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) prevention practices by nurses working in health care settings: facilitators and barriers to implementation. Appl Ergon. 2023;106:103895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim MI, Zubair IU, Yaacob NM, Ahmad MI, Shafei MN. Low back pain and its associated factors among nurses in public hospitals of penang, malaysia, Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SJ, Faucett J, Gillen M, Krause N, Landry L. Factors associated with safe patient handling behaviors among critical care nurses. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53:886–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Soud AMA, El-Najjar AR, El-Fattah NA, Hassan AA. Prevalence of low back pain in working nurses in Zagazig university hospitals: an epidemiological study study. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil. 2014;41:109–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albanesi B, Piredda M, Bravi M, Bressi F, Gualandi R, Marchetti A, et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce work-related musculoskeletal injuries and pain among healthcare professionals. A comprehensive systematic review of the literature. J Saf Res. 2022;82:124–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firmino CF, Sousa LMM, Marques JM, Antunes AV, Marques FM, Simões C. Musculoskeletal symptoms in nursing students: concept analysis. Rev Bras Enferm. 2019;72:287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jradi H, Alanazi H, Mohammad Y. Psychosocial and occupational factors associated with low back pain among nurses in Saudi Arabia. J Occup Health. 2020;62:e12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menzel N, Feng D, Doolen J. Low back pain in student nurses: literature review and prospective cohort study. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2016;13:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell T, O’Sullivan PB, Burnett AF, Straker L, Rudd C. Low back pain characteristics from undergraduate student to working nurse in australia: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:1636–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbas J, Hamoud K, Jubran R, Daher A. Has the COVID-19 outbreak altered the prevalence of low back pain among physiotherapy students? J Am Coll Health. 2023;71:2038–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daher A, Dar G, Carel R. Effectiveness of combined aerobic exercise and neck-specific exercise compared to neck-specific exercise alone on work ability in neck pain patients: a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021;94:1739–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dionne CE, Dunn KM, Croft PR, Nachemson AL, Buchbinder R, Walker BF, et al. A consensus approach toward the standardization of back pain definitions for use in prevalence studies. Spine. 2008;33:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Ami N, Korn L. Associations between backache and stress among undergraduate students. J Am Coll Health. 2018;68(1):61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daher A, Halperin O. Association between psychological stress and neck pain among college students during the coronavirus disease of 2019 pandemic: a questionnaire-based cross-sectional study. Healthc (Basel). 2021;9:1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young IA, Dunning J, Butts R, Mourad F, Cleland JA. Reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness of the neck disability index and numeric pain rating scale in patients with mechanical neck pain without upper extremity symptoms. Physiother Theor Pract. 2019;35:1328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tonosu J, Takeshita K, Hara N, Matsudaira K, Kato S, Masuda K, et al. The normative score and the cut-off value of the Oswestry disability index (ODI). Eur Spine J. 2012;21:1596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moodley M, Ismail F, Kriel A. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders amongst undergraduate nursing students at the university of Johannesburg. Health SA. 2020;25:1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selvi Y, Özdemir PG, Özdemir O, Aydın A, Beşiroğlu L. Influence of night shift work on psychologic state and quality of life in health workers workers. Dusunen Adam J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2010;23:238–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith GD, Lam L, Poon S, Griffiths S, Cross WM, Rahman MA, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on stress and resilience in undergraduate nursing students: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;72:103785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang S, Chang MC. Chronic pain: structural and functional changes in brain structures and associated negative affective States. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suliman M. Prevalence of low back pain and associated factors among nurses in Jordan. Nurs Forum. 2018;53:425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samaei SE, Mostafaee M, Jafarpoor H, Hosseinabadi MB. Effects of patient-handling and individual factors on the prevalence of low back pain among nursing personnel. Work. 2017;56:551–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen JN, Holtermann A, Clausen T, Mortensen OS, Carneiro IG, Andersen LL. The greatest risk for low-back pain among newly educated female health care workers; body weight or physical work load? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abolfotouh SM, Mahmoud K, Faraj K, Moammer G, ElSayed A, Abolfotouh MA. Prevalence, consequences and predictors of low back pain among nurses in a tertiary care setting. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2439–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daher A, Carel RS, Dar G. Neck pain clinical prediction rule to prescribe combined aerobic and neck-specific exercises: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2022;102:pzab269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ALMaghrabi AO, ALSharif FH, ALMutary HH. Prevalence of low back pain and associated risk factors among nurses – review. Int J Novel Res Healthc Nurs. 2021;8:150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dlungwane T, Voce A, Knight S. Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain among nurses at a regional hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Health SA. 2018;23:1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sitthipornvorakul E, Janwantanakul P, Purepong N, Pensri P, van der Beek AJ. The association between physical activity and neck and low back pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:677–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryan EC, Dubrow R, Sherman JD. Medical, nursing, and physician assistant student knowledge and attitudes toward climate change, pollution, and resource conservation in health care. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karahan A, Bayraktar N. Effectiveness of an education program to prevent nurses’ low back pain. Workplace Health Saf. 2013;61(2):73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aljohani WA, Pascua GP. Impacts of manual handling training and lifting devices on risks of back pain among nurses: an integrative literature review. Nurse Media J Nurs. 2019;9(2):210–30. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.