Abstract

Background

Panax ginseng is a perennial plant valued for its medicinal and nutritional properties. Its fruit contains a variety of bioactive compounds such as ginsenosides, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and anthocyanins. However, the regulatory mechanisms underlying the accumulation of these compounds during fruit development remain largely unexplored.

Results

We performed integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses across four developmental stages of ginseng fruit. Metabolite profiling revealed stage-specific accumulation patterns of ginsenosides and phenolics with biphasic trends, and increasing levels of flavonoids and anthocyanins during maturation. We constructed a metabolic and gene expression atlas covering primary metabolism (carbon, amino acids, nitrogen), secondary metabolism (flavonoids, terpenoids), and hormone signaling pathways (abscisic acid, gibberellin, brassinosteroids). Key structural genes and transcription factors, including MYB, bHLH, and ERF families, were found to coordinate stage-specific metabolic shifts. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis revealed metabolite-linked gene modules that delineate regulatory relationships.

Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive molecular framework of fruit development in P. ginseng, highlighting coordinated transcriptional regulation and metabolic reprogramming. These insights contribute to our understanding of developmental regulation in medicinal plants and lay the groundwork for metabolic engineering strategies aimed at enhancing nutritional quality and bioactive compound production.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-07221-2.

Keywords: Panax ginseng, Multi-omics integration, Fruit development, Secondary metabolism, Primary metabolism, Transcription factors

Background

Plant metabolic networks are regulated through dynamic interactions between transcriptional programs and biochemical pathways, enabling developmental progression and environmental adaptation [1, 2]. Ginseng (Panax ginseng), is a perennial herbaceous plant valued for its diverse array of secondary metabolites, especially ginsenosides, which accumulate in a tissue- and stage-specific manner. While much attention has been given to root-derived metabolites, the regulatory mechanisms governing fruit development and metabolic transitions in ginseng remain poorly understood [3]. The perennial growth cycle and specialized tissue metabolism of ginseng present unique challenges for developmental and regulatory studies [4]. Elucidating how transcriptional regulation coordinates with metabolite production throughout fruit development requires a comprehensive, systems-level approach [5].

Fruit development involves tightly coordinated shifts in primary and secondary metabolic pathways that support cellular growth and physiological differentiation. Primary metabolism supplies energy and carbon skeletons through pathways such as carbohydrate metabolism, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and nitrogen assimilation, each dynamically regulated throughout developmental stages [6, 7]. Secondary metabolites, including carotenoids and phenolic compounds, are also developmentally regulated and contribute to pigmentation, defense, and tissue-specific differentiation [8, 9]. The accumulation of these compounds is shaped by transcriptional regulation and environmental cues. For example, AREB1 modulates sugar and amino acid metabolism in tomato, and light and temperature affect metabolic fluxes and developmental timing [10, 11]. Dissecting the transcriptional regulation of metabolic reprogramming during fruit maturation is critical for understanding developmental processes and adaptive evolution in plants.

Recent advances in multi-omics technologies have enabled comprehensive investigations of plant metabolic networks at multiple regulatory layers [12]. While transcriptomics offers insight into gene expression dynamics, it alone often falls short of capturing the complexity of metabolite accumulation, which is shaped by post-transcriptional, enzymatic, and developmental regulation [13]. Integrative approaches that combine metabolomics and transcriptomics allow for the construction of gene-to-metabolite association networks, thereby identifying key transcriptional switches and co-regulated modules that govern developmental metabolic reprogramming [14]. Such strategies have been applied in model and crop species, including jujube (Ziziphus jujuba) and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), to dissect regulatory circuits controlling sugar, organic acid, and flavonoid pathways in response to developmental cues and environmental variation [15, 16].

Although root-specific metabolism in ginseng has been extensively investigated, the regulatory mechanisms driving metabolite dynamics in the fruit remain largely unexplored [17]. While the commercial value of ginseng has traditionally centered on its roots, the fruit plays essential biological roles in reproduction and germplasm renewal and serves as an active site of physiological and metabolic processes during seed maturation. Recent studies have demonstrated that ginseng fruit accumulates a unique profile of secondary metabolites, including ginsenosides, flavonoids, and phenolics, some of which exhibit antioxidant and pharmacological properties [18, 19]. Furthermore, ginseng fruits are increasingly recognized as potential functional food ingredients, underscoring the importance of investigating fruit development not only for fundamental biological insight but also for applications in medicinal and nutritional industries.

The developmental transitions that accompany fruit maturation are known to involve profound metabolic reprogramming, yet the timing, coordination, and molecular basis of these shifts in ginseng fruit are poorly understood. In particular, the integration of transcriptional changes with stage-specific patterns of metabolite accumulation has not been systematically characterized. Given the dynamic enrichment of ginsenosides and other secondary metabolites during fruit maturation, there is a critical need to resolve how gene regulatory programs shape metabolic pathways over time. Addressing this gap is essential to advancing our understanding of tissue-specific metabolic regulation in long-lived medicinal plants and may offer a broader framework for studying the evolution of developmental control in non-model species.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the molecular regulation underlying ginseng fruit development by integrating transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses across four defined developmental stages. This time-series design enabled the capture of stage-specific gene expression patterns and metabolite accumulation dynamics with high temporal resolution. Using RNA sequencing and ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, we constructed a developmental atlas of transcriptional regulation and metabolic reprogramming. We further identified transcription factors, biosynthetic genes, and regulatory modules associated with primary and secondary metabolism. These findings provide new insights into tissue-specific metabolic regulation during fruit maturation and contribute to a broader understanding of developmental control in perennial, non-model medicinal plants, while also laying the groundwork for the valorization of ginseng fruit as a source of bioactive compounds.

Materials and methods

Plant material selection and sample collection

Two-year-old ginseng seedlings (Panax ginseng cv. “Da Ma Ya”) were selected from a commercial ginseng farm located in Jilin Province, China, known for its optimal conditions for ginseng cultivation. Seedlings were rigorously screened to ensure robust health, complete bud integrity, and uniform morphological characteristics and size, thereby minimizing variation among individuals. Forest soil (dark brown soil) used for cultivation was collected from a natural birch forest and transported to the experimental greenhouse, where it was manually cleaned to remove debris including branches, weeds, insects, and large stones. No additional fertilizers or chemical amendments were added to the soil throughout the experiment.

The pot experiment was initiated in April 2024, following previously described protocols with slight modifications [20, 21]. Sixty healthy seedlings, as described above, were planted in polypropylene pots (17 cm height, 20 cm diameter) containing the prepared forest soil. Each pot accommodated two seedlings, resulting in a total of 30 pots. Plants were routinely irrigated based on observed moisture requirements, and weeds were removed manually to maintain soil cleanliness and reduce competition for resources. Greenhouse environmental conditions were tightly controlled with a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C and relative humidity of approximately 60 ± 5%. A 16-hour photoperiod with cool white fluorescent lamps (32 W) provided a light intensity of around 9500 lx daily, followed by an 8-hour dark period. The growth status of plants was monitored regularly to ensure optimal health conditions throughout the cultivation period.

Fruit samples were collected systematically at four representative developmental stages based on distinct morphological characteristics of fruit coloration, indicative of progressive maturity: white-green stage (early fruit set with initial fruit expansion, 55 days of growth), full green stage (rapid fruit expansion phase, 70 days of growth), green-red transition stage (onset of maturation, 95 days of growth), and full red stage (fully mature fruits, 115 days of growth). At each developmental stage, fruits were harvested from multiple plants across different pots to ensure representative sampling and avoid potential individual plant bias. Each developmental stage comprised four independent biological replicates. Samples were promptly collected during the early evening hours (6:00–7:00 p.m.) to minimize potential diurnal metabolic fluctuations. Immediately after collection, each sample was rapidly divided into two portions: one portion was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses, while the other portion was reserved for targeted biochemical quantification of metabolites, including ginsenosides, total phenolics, total flavonoids, and anthocyanins.

Metabolomics analysis

Approximately 50 mg of frozen ginseng fruit samples were weighed precisely and placed into 2 mL sterile centrifuge tubes. Then, 400 µL extraction solvent (methanol: water = 4:1, v/v) and 6 mm grinding beads were added into each tube. Samples were subsequently homogenized using a high-throughput tissue grinder at − 10 °C for 6 min with a frequency of 50 Hz. Following grinding, the homogenates were incubated at − 20 °C for 30 min to ensure adequate metabolite extraction, then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants were carefully collected and transferred to LC-MS/MS injection vials for subsequent analysis. To ensure quality control (QC), equal volumes from each sample extract were pooled to create a mixed QC sample.

Extracted metabolites were analyzed using an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system coupled to a Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (UHPLC-Q Exactive HF-X, Thermo Scientific, USA). Mass spectrometry was performed with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating simultaneously in both positive and negative ionization modes. The raw LC-MS/MS data were pre-processed using Progenesis QI software (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA).

Metabolite identification was performed through comprehensive searches against public metabolite databases, including the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB, version 4.0; http://www.hmdb.ca/) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/). The preprocessed data matrix was further uploaded to the Majorbio Cloud Platform (https://cloud.majorbio.com) for statistical and bioinformatics analyses [22]. Data were normalized using Pareto scaling before orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) to identify differences among fruit developmental stages. Differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) were defined according to variable importance in projection (VIP) values from the OPLS-DA model (> 1.0) and statistical significance criteria (P < 0.05). Identified DAMs were further subjected to metabolic enrichment and pathway analyses based on the KEGG database to elucidate key metabolic transitions during fruit maturation.

Transcriptomic analysis

Total RNA was extracted from frozen ginseng fruit samples using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and purity were quantified using a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA), and RNA integrity was verified through agarose gel electrophoresis and an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA).

Purified RNA samples were subsequently sent to Majorbio Bio-pharm Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), for cDNA library preparation and sequencing. Library preparation followed Illumina’s standard protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), including mRNA enrichment using oligo (dT)-attached magnetic beads, fragmentation, random hexamer-primed reverse transcription, second-strand synthesis, adapter ligation, size selection, PCR amplification, and final quality validation. A total of 16 libraries (four developmental stages, each with four biological replicates) were constructed and subjected to paired-end sequencing (2 × 150 bp read length) using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Raw sequencing data were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under accession number PRJNA1246348.

Raw paired-end reads were processed for quality control using fastp software (Version 0.19.5) with default settings. High-quality clean reads were aligned to the ginseng reference genome (sourced from the Ginseng Database: http://ginsengdb.snu.ac.kr) using HISAT2 software (Version 2.1.0) with orientation mode enabled [23]. The mapped reads were assembled into transcripts using StringTie (Version 2.1.2) through a reference-based assembly approach [24].

Gene expression levels were quantified and normalized as transcripts per million reads (TPM) using RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization (RSEM, Version 1.3.3). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among the four fruit developmental stages were identified using DESeq2 software (Version 1.24.0) based on thresholds of |log2(fold change) | >2 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 (P-adjust) [25]. Identified DEGs were subsequently analyzed through functional enrichment analysis utilizing Gene Ontology (GO) annotations and KEGG pathway analysis via the Majorbio Cloud Platform, enabling further elucidation of gene regulatory networks associated with fruit development [22].

qRT-PCR validation of key differentially expressed genes

To validate the reliability of transcriptomic data, a total of 10 key DEGs associated with ginseng fruit development were selected for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. Specific primers for each gene were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software (Premier Biosoft, USA). Primer sequences used for the selected genes and the internal reference gene (GAPDH) are provided in Table S1. Total RNA samples used for qRT-PCR were the same batch as those utilized for transcriptome sequencing, thus ensuring comparability. All qRT-PCR reactions were conducted in triplicate for each biological replicate. Relative gene expression levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as the internal reference gene for normalization.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

To systematically investigate gene co-expression patterns and identify key modules significantly correlated with fruit developmental stages and metabolite accumulation, a weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed using the WGCNA package in R software (Version 3.6.3). Initially, gene expression data obtained from RNA-seq (expressed as TPM values) were filtered to remove genes with consistently low expression (TPM < 1 in all samples), ensuring robust network construction. The filtered expression matrix was then log2-transformed (log2(TPM + 1)) to normalize data distribution.

Network topology analysis was conducted using the pickSoftThreshold function to determine an appropriate soft thresholding power (β) that ensures a scale-free topology fitting index (R2) greater than 0.85. Subsequently, adjacency matrices were constructed by raising the Pearson correlation coefficient between gene pairs to the power of β. A topological overlap measure (TOM) was calculated to quantify gene interconnectivity, and hierarchical clustering was performed based on TOM-based dissimilarity to classify genes into distinct co-expression modules. Module assignment was conducted using a dynamic tree-cut algorithm, with the following parameters: minModuleSize = 30, soft threshold power = 9, and mergeCutHeight = 0.25.

Module eigengenes (MEs), representing the overall expression patterns of each module, were calculated as the first principal component of all gene expression profiles within a module. Pearson correlation analysis was then performed between MEs and fruit developmental stages (white-green, full green, green-red transition, and full red). Modules exhibiting significant correlation (P < 0.05) with these traits were defined as key modules potentially involved in fruit maturation processes.

Determination of ginsenosides, phenolics, flavonoids, and anthocyanins

The contents of key monomeric ginsenosides in ginseng fruits at different developmental stages were determined using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap/MS, Thermo Scientific, USA) following procedures adapted from the Chinese Pharmacopoeia and previous established methodologies [26, 27].

The total phenolic content (TPC) in ginseng fruit samples was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric method as previously described [28]. The total flavonoid content (TFC) was quantified based on the aluminum chloride (AlCl3) colorimetric method following established procedures [29]. Additionally, anthocyanins were extracted from the fruit samples using the acidified methanol extraction method, as outlined in prior studies [30]. All analyses were conducted with at least four biological replicates per developmental stage.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (Version 3.6.3) and GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.1.2). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least four independent biological replicates per developmental stage. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s multiple range test or Tukey’s HSD test, was applied to detect significant differences among groups, with significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Morphological characteristics and bioactive compounds of ginseng fruits at different developmental stages

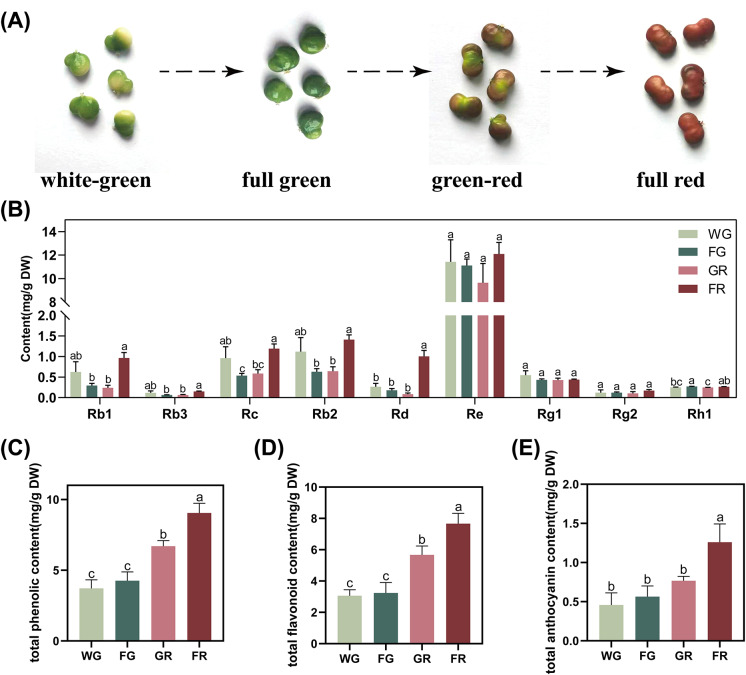

To investigate the morphological and biochemical characteristics of ginseng fruits at different developmental stages, we examined fruits from four stages: WG, FG, GR, and FG. Representative images of the fruits at each stage are shown in Fig. 1A. The contents of nine ginsenosides at different developmental stages are presented in Fig. 1B. Notably, the levels of Rb1, Rb3, and Rb2 were significantly higher at the FR compared to the FG and GR. Additionally, Rc content was significantly elevated at FR relative to FG and GR, while WG displayed a higher level compared to FG. Rd content was significantly higher at FR compared to WG, FG, and GR. In contrast, Rh1 content peaked at the FG, significantly higher than WG and GR, and was also higher at FR than at GR. The contents of Re, Rg1, and Rg2 remained relatively stable throughout all four developmental stages without significant differences.

Fig. 1.

Dynamic accumulation of bioactive compounds during ginseng fruit development. A Four representative developmental stages of ginseng fruits. B Contents of nine ginsenosides across developmental stages. C Total phenolic content. D Total flavonoid content. E Total anthocyanin content. Different lowercase letters above bars indicate statistically significant differences between stages (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05)

The TPC and TFC of ginseng fruits increased significantly as the fruit matured (Fig. 1C and D). The levels of TPC and TFC were substantially higher at the FR compared to the WG, FG, and GR stages. Furthermore, GR showed significantly higher contents of both TPC and TFC than WG and FG, while WG and FG did not differ significantly. The total anthocyanin content (TAC) exhibited a sharp increase at the FR, showing significantly higher levels compared to WG, FG, and GR (Fig. 1E). No significant differences were observed among WG, FG, and GR, indicating that anthocyanin accumulation predominantly occurs at the final maturation stage, corresponding to the visible red coloration of the fruit. These results indicate that ginsenosides (especially Rb1, Rb3, Rb2, Rc, and Rd), total phenolics, total flavonoids, and total anthocyanins exhibit dynamic and stage-specific accumulation patterns during ginseng fruit development.

Metabolomic analysis of ginseng fruits at different developmental stages

To investigate the dynamic metabolic changes during ginseng fruit development, we performed LC-MS-based metabolomic analysis on fruit samples collected from four developmental stages. A total of 1228 metabolites were identified and classified into several major categories based on the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), including lipids and lipid-like molecules, organic acids and derivatives, organic oxygen compounds, organoheterocyclic compounds, and phenylpropanoids and polyketides (Fig. 2A and Table S2). The PCA plot revealed a clear and distinct separation among samples from each developmental stage, indicating significant metabolic differences between stages. Furthermore, samples within each stage exhibited tight clustering, demonstrating high reproducibility and consistency of metabolic profiles within the same developmental stage (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Metabolomic profiling reveals dynamic changes during ginseng fruit development. A Classification of detected metabolites. B Principal component analysis (PCA) of metabolic profiles across developmental stages. C Statistics of differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) in pairwise comparisons. D–F KEGG enrichment analysis of DAMs in specific comparisons: D FG vs. WG, E GR vs. FG, F FR vs. GR. G Temporal trajectory analysis of metabolic profiles

To identify the metabolic shifts between developmental stages, we conducted pairwise comparisons of DAMs between adjacent stages (FG vs. WG, GR vs. FG, FR vs. GR). A total of 403, 423, and 409 DAMs were identified in the FG vs. WG, GR vs. FG, and FR vs. GR comparisons, respectively (Fig. 2C and Fig. S1). In the FG vs. WG comparison, the most significantly enriched pathways were Cutin, suberine, and wax biosynthesis, Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, Flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis, and Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (Fig. 2D). For the GR vs. FG comparison, the significantly enriched pathways included Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, Cutin, suberine, and wax biosynthesis, Flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, and alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism (Fig. 2E). In the FR vs. GR comparison, the most enriched pathways were Flavonoid biosynthesis, Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, Riboflavin metabolism, Inositol phosphate metabolism, and Ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis (Fig. 2F).

To further investigate the temporal patterns of metabolite changes, we conducted a time-series analysis of the metabolite profiles across the four developmental stages. A total of 10 metabolic profiles were obtained, among which 3 profiles exhibited significant trends (Fig. 2G). The first profile (9) showed a continuous increase throughout development, including metabolites enriched in Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, Tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis, Isoflavonoid biosynthesis, Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis, and Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism. The second profile (6) demonstrated an increase at the FG stages followed by a decrease at GR. Metabolites in this profile were associated with One carbon pool by folate, beta-Alanine metabolism, Histidine metabolism, Cysteine and methionine metabolism, and Linoleic acid metabolism. The third profile (3) exhibited a decrease over the FG stages, followed by an increase at FR. Metabolites in this profile were related to Stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis, Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, Biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites, Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, and Pentose and glucuronate interconversions (Fig. S2).

Transcriptomics analysis of ginseng fruits at different developmental stages

To explore the transcriptional dynamics during ginseng fruit development, we performed RNA-seq analysis on fruit samples from four developmental stages (the sequencing data statistics are shown in Table S3). The PCA plot revealed that the samples from each developmental stage clustered tightly together, indicating high reproducibility and consistency within each group. Notably, the GR and FR groups exhibited partial overlap, suggesting that these two stages may share similar transcriptional profiles. In contrast, the WG and FG samples were clearly separated (Fig. 3A). We conducted pairwise comparisons of DEGs between adjacent stages, a total of 5242 (2939 upregulated and 2303 downregulated), 7193 (2977 upregulated and 4193 downregulated), and 159 (60 upregulated and 99 downregulated) DEGs were identified in the FG vs. WG, GR vs. FG, and FR vs. GR comparisons, respectively (Fig. 3B). In addition, to examine the overlap and specificity of DEGs among the three comparisons, a Venn diagram was generated (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Transcriptomic analysis identifies key regulatory pathways during ginseng fruit development. A Principal component analysis (PCA) of transcriptome profiles across developmental stages. B Statistics of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in pairwise comparisons. C Venn diagram illustrating overlaps of DEGs between comparison groups. D–F KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in specific comparisons: D FG vs. WG, E GR vs. FG, F FR vs. GR

To understand the functional roles of DEGs, we performed GO annotation for each comparison. The major enriched GO terms across all comparisons were similar, suggesting that key functional categories are consistently regulated throughout fruit development (Fig. S3A-C). Detailed, binding, catalytic activity, cellular anatomical entity, biological regulation, metabolic processes, and cellular processes were the most enriched terms. To further explore the biological functions of DEGs, we conducted KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for each comparison. In the FG vs. WG comparison, enriched pathways included Brassinosteroid biosynthesis, Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, Cutin, suberine and wax biosynthesis, Flavonoid biosynthesis, and Zeatin biosynthesis (Fig. 3D). In the GR vs. FG comparison, significantly enriched pathways included Flavonoid biosynthesis, Zeatin biosynthesis, Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, Plant hormone signal transduction, and Zeatin biosynthesis (Fig. 3E). The FR vs. GR comparison revealed enrichment in Anthocyanin biosynthesis, Flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, Fatty acid degradation, Carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms, and Tryptophan metabolism (Fig. 3F).

Transcription factor analysis during ginseng fruit development

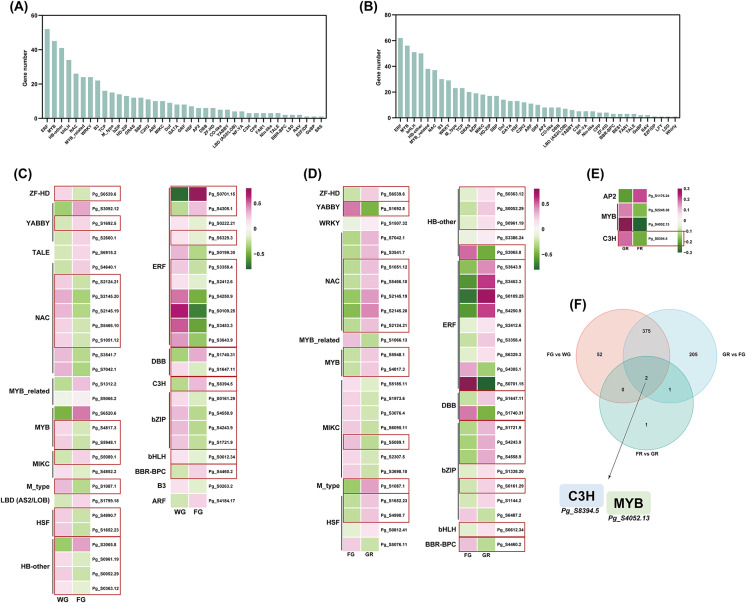

To understand the regulatory mechanisms underlying ginseng fruit development and ripening, we performed a comprehensive analysis of transcription factors (TFs) in four developmental stages based on the Plant Transcription Factor Database (PlantTFDB). In the FG vs. WG comparison, we identified 429 transcription factors belonging to 39 different TF families. Among these, the most represented families were ERF (Ethylene Response Factor), MYB (Myeloblastosis-related), and HB-other (Homeobox-other) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in the GR vs. FG comparison, 583 transcription factors were identified, which belonged to 41 TF families (Fig. 4B). Notably, the most abundant families were ERF, MYB, and bHLH (Basic Helix-Loop-Helix).

Fig. 4.

Transcription factor (TF) dynamics reveal differential regulation during ginseng fruit development. A Distribution of TFs identified in the FG vs. WG comparison. B Distribution of TFs in the GR vs. FG comparison. C Expression profiles of the top 50 highly expressed TFs in FG vs. WG. D Expression profiles of the top 50 highly expressed TFs in GR vs. FG. E Expression profiles of TFs in FR vs. GR. F Venn diagram showing overlapping TFs across pairwise comparisons. The red boxes highlight the TFs that are significantly differentially expressed across multiple pairwise comparisons

To gain deeper insights into transcriptional dynamics, we examined the expression profiles of the top 50 differentially expressed TFs in both FG vs. WG and GR vs. FG comparisons. A number of transcription factors were downregulated in the FG vs. WG comparison, notably including ERF and NAC families, while MYB family members showed an opposite trend with increased expression at the WG stage (Fig. 4C). In the GR vs. FG comparison, most transcription factors displayed significant upregulation in the GR stage. ERF and NAC family members were predominantly upregulated, while HSF and bZIP family members also exhibited increased expression. Additionally, MYB and WRKY family members showed significant upregulation, highlighting their roles in transcriptional activation during fruit development (Fig. 4D). For transcriptional regulation in the final maturation stage (FR vs. GR), we obtained four differentially expressed TFS belonging to the MYB, C3H and AP2 families. The MYB and C3H TFs exhibited downregulation in the FR stage. In contrast, AP2 transcription factors were upregulated, indicating a distinct shift in transcriptional regulation during the final maturation phase (Fig. 4E).

To identify common and unique transcription factors across different developmental transitions, we performed Venn diagram analysis of TFs from the three pairwise comparisons. several key TFs, including MYB, ERF, bZIP, and NAC, were identified as showing significant differential expression across multiple comparisons of developmental stages (Fig. 4C, D). Two MYB genes, Pg_S4817.3 and Pg_S5948.1, were downregulated at the FG stage, with subsequent upregulation at the GR stage, indicating their involvement in metabolic shifts during fruit maturation. For the ERF family, seven genes, including Pg_S6329.3, Pg_S3358.4, and Pg_S2412.6, showed downregulation at the FG stage, followed by upregulation at the GR stage, suggesting their role in regulating ripening and stress responses. In contrast, two ERF genes, Pg_S0701.15 and Pg_S4305.1, were upregulated at the FG stage, but exhibited downregulation at the GR stage, highlighting the dynamic regulatory roles these genes play in different phases of fruit maturation. Similarly, five NAC genes, such as Pg_S2124.21, Pg_S2145.20, and Pg_S2145.19, were downregulated at the FG stage, but showed upregulation at the GR stage, indicating their involvement in cell expansion and structural remodeling during fruit development. Finally, four bZIP genes, including Pg_S0161.29, Pg_S4558.9, and Pg_S4243.9, exhibited a similar pattern, with downregulation at the FG stage followed by upregulation at the GR stage. Interestingly, the analysis revealed that only two transcription factors were consistently identified as differentially expressed across all three comparisons: Pg_S8394.5 (C3H) and Pg_S4052.13 (MYB) (Fig. 4F). The presence of only two consistently regulated TFs across all stages indicates that most transcriptional regulation is highly stage-specific.

Primary metabolism during ginseng fruit development

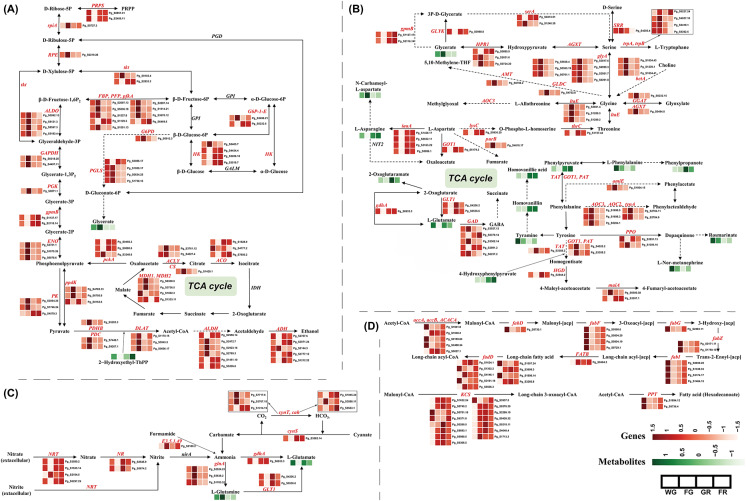

To investigate carbohydrate metabolic activity during ginseng fruit development, we analyzed the expression profiles of genes involved in central carbon metabolism (Fig. 5A). Within glycolysis, genes encoding phosphofructokinase (PFK), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and pyruvate kinase (PK) displayed divergent expression patterns among gene members, suggesting gene-specific contributions to sugar metabolism. In contrast, genes encoding hexokinase (HK) and aldolase (ALDO) also showed member-specific regulation, indicating differential roles during various stages of fruit development. For gluconeogenic enzymes, such as fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP) and phosphoenolpyruvate dikinase (PPDK), expression trends varied among gene members, reflecting potential shifts in carbon flow direction during development. Genes encoding malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) were also transcriptionally regulated in a complex manner, possibly contributing to redox balance and organic acid fluxes. In the pentose phosphate pathway, genes annotated as transketolase (TKT) exhibited divergent expression across gene members, whereas 6-phosphogluconolactonase (PGLS) showed consistent upregulation. Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase (RPIA) maintained stable expression patterns, while ribulose-phosphate 3-epimerase (RPE) displayed member-specific transcriptional variation. TCA cycle-related genes such as aconitase (ACO) showed mixed expression trends, while representative genes encoding succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex components (PDH) were more uniformly expressed, suggesting conserved central carbon flux through respiration. These transcriptional patterns were mirrored by the dynamic accumulation of key carbohydrate-related metabolites. For example, 2-Hydroxyethyl-ThPP, a cofactor involved in pyruvate decarboxylation, accumulated at the later stages, whereas glycerate, a glycolytic intermediate, peaked early and declined thereafter.

Fig. 5.

Integrated regulatory network of key primary metabolic pathways during ginseng fruit development. A Carbon metabolism. B Amino acid metabolism. C Fatty acid metabolism. D Nitrogen metabolism. The pathway maps were simplified, and some intermediate metabolites and bypasses of the metabolic pathway were not shown to emphasize the DAMs and DEGs detected

To investigate changes in amino acid metabolism during ginseng fruit development, we analyzed transcriptomic and metabolomic profiles of key enzymes and metabolites involved in this pathway (Fig. 5B). The results revealed stage-specific transcriptional regulation and metabolite accumulation patterns across multiple amino acid biosynthetic and catabolic routes. Genes involved in glutamate and glutamine metabolism, such as glutamine synthetase (GLUL) and glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), exhibited divergent expression among gene members, reflecting fine-tuned regulation of nitrogen assimilation and neurotransmitter-related compounds. In contrast, asparagine synthetase (ASNS) showed consistent expression trends across development, while genes annotated as branched-chain amino acid transaminase (BCAT) displayed divergent expression patterns, suggesting gene-specific roles in amino acid interconversion. Tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT) and alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGXT) were also upregulated at later stages, potentially contributing to secondary metabolite synthesis or nitrogen redistribution. These transcriptional patterns were supported by metabolomic profiles. L-Glutamate and L-Asparagine showed low accumulation during early stages but increased toward GR and FR, consistent with the upregulation of nitrogen-assimilating enzymes. Conversely, L-Phenylalanine, Rosmarinate, and Tyramine, which are related to aromatic amino acid metabolism, were more abundant at WG and FG, but declined during ripening.

To explore the regulation of nitrogen metabolism during ginseng fruit development, we examined the expression patterns of genes involved in nitrogen assimilation, ammonium transport, and amino group interconversion (Fig. 5C). The results revealed dynamic and stage-specific transcriptional regulation of multiple nitrogen-related pathways. Several genes annotated as nitrate transporter (NRT) showed divergent expression trends, suggesting that different isoforms may contribute to nitrate uptake and distribution at distinct developmental stages. Similarly, genes annotated as carbonic anhydrase (CAH) and beta-type carbonic anhydrase (CAN) exhibited variable expression patterns, implying differential roles in bicarbonate production and pH regulation. Ferredoxin-dependent glutamate synthase (GLT1), represented by a single gene, displayed a biphasic expression pattern, with increased transcript levels at FG and FR, indicating possible involvement in ammonium assimilation during these stages. Genes annotated as glutamine synthetase (GLNA) also showed divergent expression among gene members, reflecting gene-specific regulation of organic nitrogen incorporation. Notably, glutamate dehydrogenase (GDHA) and nitrate reductase (NR) were each represented by one gene that showed increased expression at the later stages, suggesting enhanced nitrogen reduction and reassimilation as the fruit matured.

We also investigated the characteristics of fatty acid metabolism during the development of ginseng fruit (Fig. 5D). During early developmental stages (WG to FG), genes annotated as ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KCS) exhibited divergent expression patterns, indicating isoform-specific regulation of fatty acid chain initiation. Genes annotated as phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPT) also showed inconsistent expression trends, suggesting differential activation of carrier proteins involved in lipid biosynthesis. Stearoyl-ACP desaturase (FAB2) was represented by two gene members with consistent expression patterns, both showing upregulation at FG followed by a gradual decline through GR and FR, potentially contributing to unsaturated fatty acid production during active biosynthetic phases. Acyl-ACP thioesterase B (FATB) exhibited a biphasic trend, increasing from WG to FG, decreasing at GR, and rising again at FR, indicating stage-specific modulation of saturated fatty acid synthesis. β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (FABF) showed a characteristic trend of downregulation at FG followed by progressive upregulation through GR and FR, implying its involvement in elongation processes during late developmental stages. β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (FABZ) was downregulated from WG to FG, then continuously upregulated from FG to FR, suggesting reactivation of fatty acid elongation during fruit maturation.

Secondary metabolism during ginseng fruit development

To elucidate the dynamics of flavonoid biosynthesis during ginseng fruit development, we analyzed the expression profiles of key structural genes and corresponding metabolite accumulation across four developmental stages (Fig. 6A). Genes involved in the early phenylpropanoid branch, such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), exhibited divergent expression trends among gene members, suggesting functional differentiation in their regulation during development. Similarly, genes encoding chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), and flavonoid 3’-hydroxylase (CYP75B1) also showed member-specific transcriptional changes, indicating temporal shifts in pathway flux toward different flavonoid subclasses. In contrast, some genes such as flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) and anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) showed varying expression among members, with certain isoforms being upregulated during the mid to late stages, potentially contributing to the accumulation of anthocyanin-related compounds. Genes annotated as UDP-glucose: flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (BZ1) and caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT) showed variable expression across gene members, reflecting further modulation in flavonoid decoration and methylation. Metabolite profiling supported these transcriptional trends. Key intermediates such as caffeic acid, sinapoyl-glucose, and 5-hydroxyconiferyl alcohol were more abundant during the early stages, whereas end products such as apiin and xanthohumol accumulated later. Notably, apiin, a glycosylated flavone, was undetectable at WG and FG stages but showed a dramatic increase at GR and peaked at FR, consistent with late-stage activation of glycosyltransferase genes.

Fig. 6.

Coordinated regulation of key secondary metabolic pathways during ginseng fruit development. A Flavonoid-related biosynthesis. B Terpenoid-related metabolism. The pathway maps were simplified, and some intermediate metabolites and bypasses of the metabolic pathway were not shown to emphasize the DAMs and DEGs detected

To investigate the regulation of terpenoid biosynthesis during ginseng fruit development, we analyzed the expression patterns of key genes involved in the mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways, as well as downstream cytochrome P450 enzymes and structural genes related to triterpenoid and steroidal terpenoid biosynthesis (Fig. 6B). Several genes encoding enzymes in the MEP pathway, including 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) and 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase (ispH), exhibited divergent expression trends among gene members, indicating complex regulation of plastid-derived precursor synthesis. Genes annotated as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR), a key enzyme in the MVA pathway, also exhibited expression divergence across gene members, reflecting dynamic regulation of cytosolic isoprenoid precursor synthesis. 10-hydroxygeraniol oxidoreductase (MTD), involved in monoterpenoid biosynthesis, showed high expression at the WG stage and a moderate rebound at FR, suggesting its potential roles in both early and late phases of fruit development.

Plant hormone biosynthesis and signal transduction during ginseng fruit development

To explore hormone-mediated regulatory processes during ginseng fruit development, we analyzed the expression patterns of genes involved in hormone signal transduction pathways (Fig. 7A). In the auxin pathway, genes annotated as Small Auxin Up RNA (SAUR), Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA), and Auxin Response Factor (ARF) exhibited divergent expression trends across different members, with some showing upregulation at early stages and others peaking during fruit ripening. Gretchen Hagen 3 (GH3) and Auxin influx carrier (AUX1/LAX) genes also displayed variable expression patterns, reflecting dynamic regulation of auxin transport and homeostasis. Abscisic acid (ABA) signaling components such as Protein Phosphatase 2 C (PP2C), Pyrabactin Resistance-Like (PYL), and SNF1-Related Protein Kinase 2 (SnRK2) showed distinct and in some cases opposing expression profiles. Several PP2C genes were upregulated during fruit maturation, while others remained low or decreased, suggesting transcriptional differentiation among gene members. Similarly, ABRE-binding factor (ABF) genes exhibited a mixture of expression peaks across early and late stages. In the gibberellin (GA) pathway, genes encoding Gibberellin Insensitive Dwarf1 (GID1), DELLA repressors, and Cyclin D3 (CYCD3) displayed diverse expression trends, indicating differential roles in developmental stage transitions. Notably, certain DELLA members showed increasing expression at the late stages, potentially contributing to growth repression during ripening. For jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid signaling, genes annotated as Jasmonate ZIM-domain (JAZ), Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor (MYC2), TGACG-motif Binding Factor (TGA), and Pathogenesis-Related Protein 1 (PR1) were expressed in stage-dependent and gene-specific manners. Several JAZ and MYC2 genes were transiently activated at mid to late stages, whereas PR1 expression varied substantially among its members. Brassinosteroid (BR) signaling genes such as BRI1-Associated Receptor Kinase 1 (BAK1) and Brassinazole Resistant 1/2 (BZR1/2) exhibited relatively consistent expression patterns, generally showing moderate expression throughout development. In contrast, cytokinin-related genes including Arabidopsis Histidine Kinase (AHK2/3/4), Type-A Arabidopsis Response Regulator (ARR-A), and Type-B Response Regulator (ARR-B) were transcriptionally active at different stages, but with notable differences among gene family members.

Fig. 7.

Hormonal coordination regulates ginseng fruit developmental transitions. A Hormone signal transduction pathways. B Biosynthesis of gibberellins (GAs). C Biosynthesis of brassinosteroids (BRs).The pathway maps were simplified, and some intermediate metabolites and bypasses of the metabolic pathway were not shown to emphasize the DEGs detected

For GA biosynthesis, several genes encoding ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase (CPS) and ent-kaurene oxidase (KAO) exhibited divergent expression trends, with some members showing upregulation at early stages and others at later stages. Genes annotated as ent-kaurene synthase (KS) showed more consistent expression patterns, with representative members exhibiting moderate expression at early and late stages, implying continuous involvement throughout development. Terminal biosynthetic genes, including gibberellin 20-oxidase (GA20ox) and gibberellin 3-oxidase (GA3ox), also showed variable expression across different members, with some isoforms highly expressed during fruit maturation. Meanwhile, gibberellin 2-oxidase (GA2ox), responsible for GA deactivation, displayed opposing patterns among its gene members. These transcriptional trends were partially mirrored by changes in GA metabolite levels. Bioactive GAs such as Gibberellin A29 showed increasing accumulation at the later stages, while A34 peaked at GR and declined thereafter. In contrast, GA catabolites such as Gibberellin A8-catabolite and Gibberellin A34-catabolite peaked at GR, indicating transient accumulation during mid to late stages (Fig. 7B).

To characterize the transcriptional dynamics of brassinosteroid (BR) biosynthesis during ginseng fruit development, we analyzed the expression of key structural genes involved in this pathway (Fig. 7C). Genes annotated as Cytochrome P450 85A1/Brassinosteroid-6-oxidase 1 (CYP85A1/BR6OX1) showed divergent expression among gene members. While some were transiently upregulated during the FG stage, others displayed reduced or stable expression, suggesting potential functional divergence in BR biosynthesis during early to mid-stages. Similarly, expression trends varied among genes annotated as Cytochrome P450 90B1/Dwarf4 (CYP90B1/DWF4) and Cytochrome P450 90C1/Rotundifolia3 (CYP90C1/ROT3), both of which encode enzymes involved in BR biosynthetic steps. Some gene members were moderately expressed throughout development, while others peaked at specific stages, indicating complex transcriptional control. In contrast, genes encoding Cytochrome P450 734A1/Brassinosteroid-inactivating enzyme (CYP734A1/BAS1), which catalyzes BR deactivation, showed a relatively stable expression across stages. Most members were transiently upregulated at FG and declined during the later stages, implying a reduction in BR inactivation as the fruit matured.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis of metabolites and genes during ginseng fruit development

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) was performed based on metabolites that exhibited differential abundance across the four developmental stages of ginseng fruit. A weighted co-expression network model was constructed to classify metabolites, which were subsequently grouped into different modules. A total of six modules were identified, each represented by a distinct color as shown in Fig. 8A. The correlation between different developmental stages and modules was analyzed, and a correlation heatmap was generated (Fig. 8B). Heatmap analysis revealed that the green module showed a significant positive correlation with the GR stage (0.985), while the grey and yellow modules were significantly negatively correlated with GR (−0.845) and FR (−0.885), respectively. To explore the potential functions of the metabolites in these modules, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed. Figure 8C displays the accumulation pattern of metabolites in the green module during ginseng fruit development, along with the associated pathway enrichment. These pathways include the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites, the biosynthesis of indole alkaloids, and the degradation and elongation of fatty acids. Figure 8D presents the accumulation pattern of metabolites in the grey module, along with pathway enrichment, suggesting a potential association with the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway. Figure 8E shows the accumulation pattern of metabolites in the yellow module and the corresponding pathway enrichment. The analysis suggests that this module may be related to D-amino acid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, and arginine and proline metabolism.

Fig. 8.

Integrative WGCNA (weighted gene co-expression network analysis) uncovers stage-specific metabolic and transcriptional modules during ginseng fruit development. A Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of metabolite-level modules. B Expression patterns of module eigengenes across developmental stages (metabolite-level). C–E KEGG pathway analysis and eigengene trends of key modules: C green, D grey, E yellow. F Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of gene-level modules. G Stage-dependent expression dynamics of gene modules. H KEGG enrichment and eigengene profile of the red module

Similarly, a WGCNA was conducted based on gene expression data during ginseng fruit development. A total of seven modules were identified, as shown in Fig. 8F. The correlation between different developmental stages and modules was analyzed, and a correlation heatmap was generated (Fig. 8G). Heatmap analysis revealed that the red module was significantly positively correlated with the FR stage (0.747). Figure 8H shows the accumulation pattern of genes in the red module during ginseng fruit development, along with the pathway enrichment analysis. These pathways include aflatoxin biosynthesis, galactose metabolism, and glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism.

Verification of RNA sequencing results by qRT-PCR

To validate the accuracy of the RNA sequencing data, we selected 12 key genes involved in primary metabolism, secondary metabolism, and plant hormone signal transduction, as well as key transcription factors potentially involved in ginseng fruit development. These genes were analyzed using qRT-PCR to examine their expression levels across the four developmental stages of ginseng fruit. Our results indicated that the expression patterns observed by qRT-PCR were consistent with those identified in the transcriptomic analysis, further supporting the reliability of the RNA sequencing data (Fig. S4).

Discussion

Fruit growth and ripening involve complex biological processes that drive changes in appearance, nutritional composition, and flavor [31]. As a medicinal plant of significant value, the development of ginseng fruit is crucial for accumulating bioactive compounds. Although ginseng root metabolism and gene regulation have been extensively studied, comprehensive analyses of metabolomic and transcriptomic changes during fruit development remain scarce. Understanding these dynamic shifts across different developmental stages is essential for optimizing breeding strategies and enhancing the accumulation of medicinal compounds. This study integrates metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses to uncover the metabolic transitions and underlying transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, addressing a critical gap in the current literature.

Changes in bioactive compounds during ginseng fruit development

The accumulation of bioactive compounds during ginseng fruit development is of great interest due to their medicinal properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer activities [19, 32]. Ginsenosides, TPC, TFC, and anthocyanins show dynamic, stage-specific accumulation patterns during ginseng fruit development. Our results reveal distinct stage-specific variations in the levels of these bioactive compounds during ginseng fruit development.

Significant differences in the six analyzed ginsenosides were observed across different developmental stages (Fig. 1B). The contents of Rb1, Rb3, Rc, Rb2, and Rd were significantly higher at the FR stage compared to earlier stages (FG and GR), peaking at FR. This supports the understanding that ginsenoside accumulation peaks during the later stages of fruit ripening, indicating active biosynthesis during maturation. Surprisingly, the observed biphasic accumulation pattern of ginsenosides during fruit development (with peaks at the WG and FR) likely reflects a sophisticated resource allocation strategy adopted by ginseng to balance growth demands [33]. In contrast, Rh1 levels peaked at the FG stage, significantly higher than at WG and GR, indicating that Rh1 is more prominent in early development and decreases as the fruit matures. In contrast, the levels of Re, Rg1, and Rg2 remained stable across all stages, suggesting that their biosynthesis is less influenced by maturation.

TPC and TFC levels increased significantly as ginseng fruits matured (Fig. 2C, D). The highest TPC and TFC levels were observed at the FR stage, consistent with previous reports that phenolic compounds and flavonoids typically accumulate during fruit ripening [19]. The increased TPC and TFC likely enhance antioxidant activities, contributing to protective functions during fruit ripening [34]. In addition to ginseng, studies on Panax quinquefolius have also revealed similar bioactive compound accumulation during fruit development. Both species show stage-specific increases in ginsenosides and flavonoids during ripening, similar to our findings in fruit [35]. Anthocyanin content, responsible for fruit coloration, increased sharply at the FR stage, reflecting the red color of mature fruits. This increase was significantly greater at FR than at WG, FG, and GR stages (Fig. 2E). No significant differences in anthocyanin content were found among WG, FG, and GR stages, indicating that anthocyanin accumulation primarily occurs late during fruit maturation. This aligns with the established role of anthocyanins in pigmentation and protection against environmental stresses during ripening [36].

In summary, our results show that ginsenosides, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and anthocyanins exhibit dynamic, stage-specific accumulation patterns during ginseng fruit development. These compounds generally peak at the final ripening stage (exceptions such as Rh1). These findings suggest that the synthesis of bioactive compounds in ginseng fruits is tightly regulated, with distinct pathways activated at specific stages of development.

Metabolomic and transcriptomic dynamics during ginseng fruit development

Coordinated regulation of metabolic and transcriptional networks is crucial for fruit development, driving the accumulation of bioactive compounds and other metabolic transitions [37]. The combined analysis offers a clear understanding of how metabolic and gene expression shifts contribute to fruit maturation and the accumulation of secondary metabolites [38]. Our LC-MS-based metabolomic analysis identified 1228 metabolites, categorized into major groups including lipids, organic acids, phenylpropanoids, and polyketides. PCA revealed distinct separation of metabolic profiles between developmental stages, with tight clustering within each stage, indicating high reproducibility and consistent metabolic trends (Fig. 2B). This separation highlights significant metabolic reprogramming as the fruit progresses through different developmental stages. Comparing adjacent stages revealed dynamic shifts in metabolite accumulation. Key metabolic pathways were significantly enriched at different stages, reflecting the changing metabolic focus during fruit maturation. In the FG vs. WG comparison, pathways like phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and flavone and flavonol biosynthesis were enriched, indicating a shift towards secondary metabolism early in fruit development. In the GR vs. FG comparison, the enrichment of flavonoid biosynthesis and plant hormone signaling pathways highlights the growing complexity of metabolic regulation during ripening. At the FR stage, pathways like anthocyanin biosynthesis and fatty acid degradation were significantly enriched, correlating with the accumulation of anthocyanins and other secondary metabolites at full ripeness. Despite the relatively low number of DEGs during the FR vs. GR stage, significant changes in metabolites suggest that post-transcriptional regulation plays a crucial role in modulating metabolic shifts. Mechanisms such as miRNA-mediated regulation, RNA modifications (e.g., m6A methylation), and protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) influence the stability, translation, and activity of metabolic enzymes, ensuring efficient metabolite production despite minimal transcriptional changes. miRNAs likely regulate key metabolic genes involved in ginsenoside and flavonoid biosynthesis, while RNA modifications and PTMs, such as phosphorylation of enzymes in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway, enhance enzymatic activity during ripening. These post-transcriptional mechanisms collectively contribute to the dynamic accumulation of bioactive compounds during fruit maturation, highlighting the importance of post-transcriptional regulation in fruit ripening and secondary metabolism [39–41].

Time-series analysis revealed three distinct metabolic profiles (Fig. 2G). The first profile showed continuous increases in metabolites linked to amino acid biosynthesis, secondary metabolism, and sugar metabolism, suggesting that these pathways remain active throughout development. The second profile showed a rise in metabolites at the FG stage, followed by a decrease at GR, reflecting the transition from rapid expansion to maturation. The third profile, characterized by a decrease during FG followed by an increase at FR, involved metabolites associated with phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and secondary metabolism, suggesting that these processes could be most active during later ripening stages.

To complement the metabolomic data, we performed RNA-seq analysis of ginseng fruit at different developmental stages. PCA of the transcriptomic data revealed clear clustering by stage, with overlap between the GR and FR stages, suggesting similar transcriptional profiles (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the WG and FG stages showed more distinct separation, indicating key regulatory shifts during the transition from early development to full maturity. The highest number of DEGs was found in the GR vs. FG comparison, suggesting substantial transcriptional reprogramming between these stages. DEGs were primarily associated with genes involved in metabolic processes, cellular regulation, and biological functions, consistent with the observed metabolic shifts (Fig. S3). KEGG pathway analysis highlighted several enriched pathways during fruit development. In the FG vs. WG comparison, pathways related to BR biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis were enriched, indicating their importance in the early stages of fruit development. The GR vs. FG comparison revealed enriched pathways related to flavonoid biosynthesis and plant hormone signaling, reinforcing the role of hormones in fruit maturation. The FR vs. GR comparison revealed the importance of secondary metabolism, with enrichment in pathways such as anthocyanin biosynthesis, fatty acid degradation, and tryptophan metabolism, corresponding to the final ripening phase and the accumulation of anthocyanins and other bioactive compounds.

Integrating metabolomic and transcriptomic data offers valuable insights into the regulatory mechanisms driving bioactive compound accumulation in ginseng fruit. Upregulation of genes involved in flavonoid and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis at various stages corresponds with the observed accumulation of these compounds, highlighting the importance of transcriptional regulation in secondary metabolism. Additionally, the enrichment of metabolic pathways linked to plant hormones, particularly during the GR to FR stages, highlights the critical role of hormonal regulation in fruit ripening. In Salvia miltiorrhiza, the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites also undergoes similar metabolic transitions, especially in the synthesis of flavonoids and phenolic acids. The accumulation of these metabolites in S. miltiorrhiza shows significant stage-specific changes during maturation [42]. By comparing these studies, we found that the metabolic pathways and transcriptional regulation mechanisms in different medicinal plants may share common evolutionary bases, particularly in regulating the synthesis of bioactive compounds.

Transcription factor regulation during ginseng fruit development

TFs are crucial in regulating gene expression networks that govern plant development, including fruit maturation [43]. Our analysis of TFs during ginseng fruit development provides valuable insights into the transcriptional mechanisms underlying dynamic metabolic changes across developmental stages (Fig. 4). In the GR vs. FG comparison, the ERF, MYB, and bHLH families were identified as dominant, with bHLH more prominently represented than in the previous comparison. This suggests that as the fruit transitions to ripening, bHLH and ERF may regulate processes associated with growth cessation, ripening, and activation of secondary metabolism [44]. The upregulation of MYB TFs, such as Pg_S4817.3 and Pg_S5948.1, during the GR stage suggests their central role in regulating flavonoid biosynthesis and ginsenoside accumulation, both of which are key bioactive compounds in ginseng. MYB factors have been shown to regulate flavonoid biosynthesis in various plant species, including tomato and grape, where they control key steps in the phenylpropanoid pathway [45]. The observed upregulation of MYB in the ripening phase of ginseng fruit aligns with these findings, highlighting their involvement in secondary metabolism during fruit maturation.

The ERF family, particularly genes like Pg_S6329.3, Pg_S3358.4, and Pg_S2412.6, showed upregulation in the GR stage, suggesting a critical role in ethylene-mediated ripening and stress response regulation. ERF transcription factors have been well-documented for their roles in ethylene signaling, which is integral to fruit ripening in many species [46]. In ginseng, the upregulation of these genes during the ripening phase likely facilitates the maturation of the fruit by promoting the necessary physiological and biochemical processes, such as cell wall modification and secondary metabolite synthesis. In Panax notoginseng, similar transcription factors, such as MYB and ERF, have been shown to regulate the ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway, which aligns with the roles of these transcription factors observed in ginseng during fruit maturation [47]. This comparison further highlights the conserved role of transcription factors in fruit development and bioactive compound synthesis. Furthermore, the structural and interaction analysis of MYB transcription factors in P. notoginseng supports the idea that these factors play a significant role in regulating secondary metabolite biosynthesis, particularly saponin production, which is critical for the medicinal properties of these plants [48].

Similarly, NAC and bZIP TFs, such as Pg_S2124.21 and Pg_S0161.29, show distinct patterns of expression, with downregulation at the FG stage and upregulation at the GR stage, suggesting their role in the transition from growth to maturation. NAC transcription factors have been shown to regulate cell expansion, tissue patterning, and senescence in other plants [49]. Their expression dynamics in ginseng could indicate a shift from cell division and growth to structural differentiation and maturation during the fruit ripening process. Similarly, bZIP TFs are involved in plant hormone signaling, particularly ABA, which has been shown to regulate stress tolerance and secondary metabolism during fruit ripening [50]. The upregulation of bZIP genes in the GR stage supports their role in integrating hormonal signals with metabolic changes required for fruit maturation.

Only two TFs, Pg_S8394.5 (C3H) and Pg_S4052.13 (MYB), were consistently differentially expressed across all three comparisons (Fig. 4F). This finding highlights the stage-specific nature of transcriptional regulation in ginseng fruit development. While a few TFs are involved throughout development, most exhibit distinct expression patterns at each stage, suggesting that transcriptional regulation is finely tuned to the fruit’s needs at each developmental phase. ERF, MYB, bZIP, NAC, and bHLH TFs are particularly important during the transition from early fruit development to ripening, suggesting that they regulate critical pathways involved in growth, stress responses, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis [51, 52]. MYB, ERF, and NAC transcription factors have been identified as key regulators of secondary metabolite biosynthesis in P. quinquefolius, which aligns with our observations in P. ginseng and suggests that these regulatory mechanisms may be conserved across these species [35].

Regulation pattern of primary metabolism during ginseng fruit development

Primary metabolism is essential for providing energy and precursors necessary for cell growth and fruit maturation [53]. This includes central carbon metabolism, nitrogen metabolism, and fatty acid biosynthesis, all crucial for supporting rapid growth and maturation of ginseng fruit [54, 55]. Our study reveals dynamic changes in the expression of key genes involved in these pathways across ginseng fruit developmental stages. These changes reflect shifting metabolic demands as the fruit progresses from early development to full maturation.

Carbohydrate metabolism is central to ginseng fruit development, providing energy and carbon skeletons for other biosynthetic pathways [56]. We observed significant changes in the expression of genes involved in glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the pentose phosphate pathway (Fig. 5A). Key glycolytic genes like PFK, GAPDH, and PK exhibited divergent expression patterns across stages, suggesting that each gene contributes differently to sugar metabolism at specific developmental points. The differential regulation of these enzymes is linked to the fruit’s metabolic needs at each stage, from early rapid cell division to later maturation stages when metabolic shifts toward energy storage and biosynthesis occur [57, 58]. Interestingly, genes involved in gluconeogenesis, like FBP and PPDK, showed varying expression trends. This suggests that carbon flow may shift during development, with the fruit transitioning from rapid growth (requiring more glycolysis) to storage and maturation (involving more gluconeogenic processes) [59]. Additionally, enzymes like MDH and ALDH were differentially expressed, playing a role in redox balance and organic acid fluxes—important for regulating the fruit’s metabolic state during maturation [60]. The pentose phosphate pathway, providing crucial precursors for nucleotide biosynthesis and antioxidant defense, also displayed varied expression patterns [61]. The enzyme PGLS was upregulated, indicating its role in supporting the fruit’s increased metabolic demands during later stages of development. These transcriptional patterns corresponded to the accumulation of carbohydrate-related metabolites. For example, 2-Hydroxyethyl-ThPP, a cofactor in pyruvate decarboxylation, accumulated at later stages, supporting the fruit’s energy metabolism during ripening [62]. Conversely, glycerate, a glycolytic intermediate, peaked early and declined, reflecting the shift in metabolic priorities as the fruit matures [63].

Amino acid metabolism is vital for protein synthesis, nitrogen assimilation, and the production of secondary metabolites during ginseng fruit development [64]. We observed stage-specific regulation of genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and catabolism (Fig. 5B). Genes involved in glutamate and glutamine metabolism, including GLUL and GAD, showed divergent expression patterns, suggesting fine-tuned regulation of nitrogen assimilation across development [65]. ASNS showed stable expression across stages, indicating a constant role in nitrogen assimilation [66]. Genes in the branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) pathway, including BCAT, also showed divergent expression patterns, likely reflecting the fruit’s stage-dependent demand for these amino acids [67]. In later stages, TAT and AGXT were upregulated, potentially contributing to secondary metabolite synthesis or nitrogen redistribution. Metabolomic data supported these transcriptional trends [68]. For instance, L-Glutamate and L-Asparagine accumulated at low levels in early stages but increased significantly by the GR and FR stages, consistent with the upregulation of nitrogen-assimilating enzymes. Conversely, L-Phenylalanine, Rosmarinate, and Tyramine—associated with aromatic amino acid metabolism—peaked early and declined with ripening. These findings suggest a temporal shift in amino acid utilization—from nitrogen assimilation in early development to secondary metabolite synthesis during maturation.

Fatty acid metabolism is essential for membrane formation, energy storage, and secondary metabolite production during ginseng fruit development [69]. We observed dynamic expression changes in genes related to fatty acid synthesis and elongation (Fig. 5D). In early stages (WG to FG), genes such as KCS and PPT showed divergent expression, indicating isoform-specific regulation of fatty acid chain initiation [69, 70]. These findings suggest tight regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis during early fruit development. At later stages, FAB2 was upregulated at FG and declined at GR and FR, likely contributing to unsaturated fatty acid synthesis during active biosynthetic phases. Similarly, FATB and FABF showed biphasic expression patterns, suggesting stage-specific regulation of saturated and unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis [71]. These results indicate that fatty acid metabolism is closely linked to fruit maturation, with distinct synthesis and elongation phases at specific developmental stages.

Regulation pattern of primary metabolism during ginseng fruit development

Secondary metabolism is critical for producing bioactive compounds that confer medicinal properties to fruits, including flavonoids, terpenoids, and other specialized metabolites [72]. Flavonoid and terpenoid biosynthesis undergo dynamic changes during ginseng fruit development, reflecting underlying metabolic reprogramming as the fruit matures. Our study offers a detailed analysis of transcriptional regulation and metabolite accumulation associated with these pathways across the four developmental stages of ginseng fruit (Fig. 6A).

Flavonoids, known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions, are major secondary metabolites in ginseng fruit [73]. Expression profiles of structural flavonoid biosynthetic genes showed clear stage-specific regulation during development. PAL and 4CL, key enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway, showed divergent expression patterns, suggesting their involvement in early-stage flavonoid backbone formation [74]. CHS, CHI, and CYP75B1 displayed member-specific transcriptional variation, indicating temporal shifts in pathway flux toward distinct flavonoid subclasses [75]. This reflects precise regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis to produce specific compounds at defined developmental stages. F3H and ANS showed isoform-specific upregulation during mid-to-late stages, likely contributing to anthocyanin accumulation and red coloration in mature fruit [76]. Their expression peaks aligned with increased anthocyanin levels, particularly at the FR stage. Decoration and methylation genes, including BZ1 and CCoAOMT, showed variable expression, consistent with their roles in the final modification of flavonoids [77]. Such modifications contribute to the functional diversity of flavonoids, affecting their solubility, bioavailability, and antioxidant properties. Metabolomic data supported transcriptional trends, with early intermediates (e.g., caffeic acid, sinapoyl-glucose, 5-hydroxyconiferyl alcohol) enriched in WG and FG stages, while downstream products like apiin and xanthohumol peaked at GR and FR. Notably, apiin was absent at WG and FG, but increased sharply at GR and peaked at FR, aligning with late-stage glycosyltransferase gene activation.

Terpenoids are key secondary metabolites in ginseng fruit, contributing to its medicinal properties such as anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects [78]. We analyzed the expression of genes in the MVA and MEP pathways, which produce terpenoid precursors (Fig. 6B). MEP pathway genes such as DXS and ispH showed divergent expression, suggesting tight regulation of plastid-derived precursor synthesis during fruit development. Similarly, HMGCR in the MVA pathway showed dynamic expression patterns, reflecting regulation of cytosolic isoprenoid precursor synthesis [79]. The MVA pathway produces sterols and triterpenoids, essential for membrane integrity and stress responses. MTD, a key enzyme in monoterpenoid biosynthesis, was highly expressed at WG and showed a moderate rebound at FR, indicating its role in both early and late developmental phases. Given its role in monoterpenoid biosynthesis—key contributors to fruit aroma and flavor—the temporal expression of MTD suggests importance in both early development and final ripening.

Plant hormone regulation during ginseng fruit development

Plant hormones are central regulators of developmental processes such as growth, ripening, and stress responses [80]. We investigated the transcriptional regulation of major hormone signaling pathways during ginseng fruit development. Expression profiles of genes associated with auxin, ABA, GA, JA, SA, BR, and cytokinin pathways revealed how hormone signaling coordinates fruit growth and maturation.

Auxin regulates cell elongation, division, and differentiation throughout fruit development. In ginseng, auxin-responsive genes such as SAUR, IAA, and ARF showed stage-specific expression, with some activated early and others during ripening. The dynamic expression of GH3 and AUX1/LAX genes highlights active auxin transport and homeostasis [81]. Similar regulatory roles have been reported in other plants. In S. miltiorrhiza, auxin promotes the biosynthesis of phenolic acids and tanshinones via transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes [82]. In aromatic crops like peppermint and fennel, auxin and auxin-producing bacteria enhance essential oil yield and modify monoterpene composition [83]. Moreover, in tomato, exogenous auxin affects pigment and primary metabolite profiles during postharvest ripening, suggesting its involvement in metabolic reprogramming [84]. Together, these findings support a conserved role for auxin in coordinating growth and metabolic transitions in diverse plant systems.

ABA plays key roles in stress responses and fruit maturation, particularly in regulating ripening and seed dormancy. In ginseng fruit, stage-specific expression of ABA-related genes—especially PP2C, SnRK2, and ABF—suggests transcriptional reprogramming during maturation. Similar regulatory roles of ABA have been observed in other fruit-bearing plants: for example, in tomato, ABA was found to trigger ethylene biosynthesis, acting as a ripening initiator that also influences fruit development and growth patterns [85]. In woodland strawberry, feedback loops coordinating ABA biosynthesis and catabolism were shown to fine-tune the timing of ripening, illustrating how hormonal homeostasis ensures developmental progression [86]. A broader overview across species highlights ABA’s central position in integrating signaling, transcriptional control, and transport processes to direct both physiological and structural changes during fruit maturation [87].

GAs promote growth and regulate fruit development, particularly the transition from immature to mature stages. In ginseng fruit, key signaling components—GID1, DELLA, and CYCD3—showed stage-specific expression, with DELLA upregulated later, consistent with its role in growth inhibition. Isoform-specific expression of GA biosynthetic genes like CPS and KAO reflects dynamic hormonal regulation throughout development. In P. notoginseng, exogenous GA significantly shortened the after-ripening phase and promoted germination by reprogramming hormone signaling pathways, including DELLA and other growth suppressors [88]. Similarly, in Phellodendron chinense, GA treatment enhanced both growth and flavonoid biosynthesis, indicating its dual role in coordinating primary growth and secondary metabolism in medicinal species [89]. Furthermore, in citrus plants, GA has been shown to increase essential oil and secondary metabolite accumulation in young bitter orange seedlings, reinforcing its metabolic regulatory capacity across species [90]. These parallels suggest that GA-mediated transcriptional shifts represent a conserved developmental strategy in both model crops and medicinal plants, linking morphogenetic control with metabolite biosynthesis.

JA and SA are central to stress responses and also participate in fruit maturation. JA signaling genes such as JAZ, MYC2, and PR1 showed stage-specific expression in ginseng fruit, with transient MYC2 activation during mid-to-late stages suggesting developmental regulation [91]. In Prunella vulgaris, exogenous JA and SA modulated defense genes and boosted phenolic production during reproductive growth [92]; in blackberry, JA and SA enhanced antioxidant capacity and shifted gene expression during postharvest ripening [93]; and in diverse medicinal plants, JA/SA were shown to upregulate WRKY and biosynthetic genes for secondary metabolites such as terpenoids and alkaloids [94]. These findings underscore a conserved role for JA/SA signaling in linking stress responses with metabolite remodeling during fruit maturation.