Abstract

Objective

Older adults are more vulnerable to digital exclusion, which has been associated with psychological distress. This study investigated the relationship between digital exclusion and loneliness among older adults across three countries using three longitudinal surveys.

Design and measurements

Digital exclusion was defined as self-reported non-use of the internet. Loneliness was assessed using the Three-Item Loneliness Scale (T-ILS). We employed Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) with binary logistic regression and propensity score matching (PSM) to examine the association between digital exclusion and loneliness, adjusting for covariates including Age; Gender; Education; Marital status; Employment status; Cohabitation with children; Self-rated health; and Income.

Setting and participants

Nationally representative samples of older adults were obtained from three longitudinal studies: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). The analysis included 39,190 participants (87,256 observations) across the three studies.

Results

Substantial cross-national disparities in digital exclusion rates were observed: CHARLS (96.20%), HRS (52.13%), and ELSA (33.54%). In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), digital exclusion was significantly associated with loneliness in all three studies (CHARLS: OR = 1.22; HRS: OR = 1.16; ELSA: OR = 1.30). These associations remained statistically significant after propensity score matching (CHARLS: OR = 1.33; HRS: OR = 1.23; ELSA: OR = 1.23).

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that a substantial proportion of older adults experience digital exclusion, particularly in China. Digital exclusion demonstrates a positive association with loneliness, suggesting that enhancing digital inclusion may serve as a critical strategy for alleviating loneliness and mitigating psychological distress in ageing populations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-025-06337-2.

Keywords: Digital exclusion, Loneliness, Older adults

Background

Globally, population aging has become an undeniable social trend, accompanied by a rapid increase in loneliness as a critical health risk factor among older adults. Loneliness is not only directly associated with psychological distress (e.g., depression and anxiety) [1] but also elevates risks of chronic disease burden, cognitive decline, and premature mortality [2, 3]. In contemporary societies characterized by high digital technology penetration, digital exclusion—defined as ineffective access to and use of the internet and digital tools—may act as an amplifier of loneliness among older adults [4, 5]. Evidence indicates that digital exclusion is prevalent among older populations across 23 countries [6].

Digital exclusion marginalizes older adults from digital societies, potentially triggering or exacerbating experiences of loneliness [7, 8]. While existing research has revealed associations between digital exclusion and loneliness, critical limitations persist: most empirical work focuses on single-country or specific cultural contexts, neglecting comparative analyses between developing and developed nations. Digital exclusion rates and underlying mechanisms are highly dependent on social support structures and technology accessibility [6]. For instance: In developing regions like China, older adults facing the digital exclusion may rely on family support systems to address immediate needs, yet persistent digital skill deficits significantly constrain their social connectivity, intensifying isolation and psychological burden [6]. In developed economies (e.g., the United States and United Kingdom), despite lower digital exclusion rates, social isolation may be amplified by technological barriers [6, 9].

Consequently, large-scale multinational research encompassing diverse cultural contexts is imperative. Such research can elucidate both universal and culture-specific pathways linking digital exclusion to loneliness while providing an empirical foundation for cross-culturally adaptable digital inclusion strategies to address the urgent mental health crisis in aging societies [9]. This study aims to address these gaps by integrating data comprising 87,256 observations from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), Health and Retirement Study (HRS), and English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). We investigate the relationship between digital exclusion and loneliness among older adults in China, the United States, and the United Kingdom, seeking to identify universal pathways through which digital exclusion influences loneliness. Our findings will provide evidence to inform inclusive digital policy formulation.

Method

Study design and population

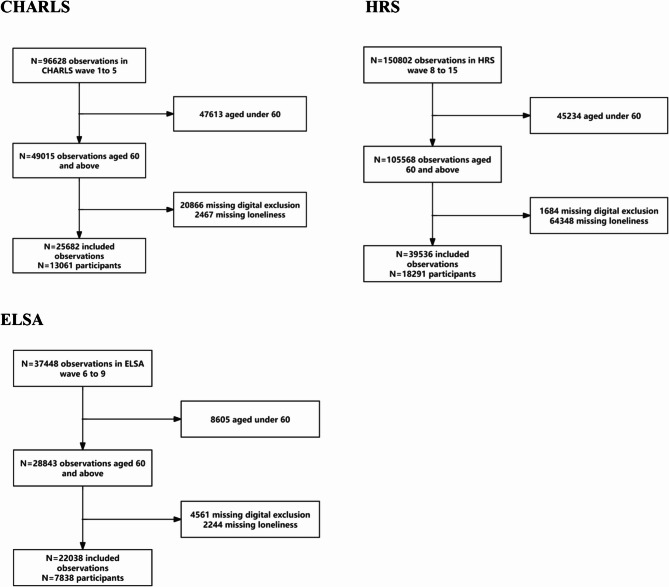

Data were derived from three longitudinal studies: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) [10], the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) [10, 11], and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) [12]. In this study, we utilized partial waves from each study: Waves 1–5 (2011–2020) for CHARLS, Waves 8–15 (2006–2020) for HRS, and Waves 6–9 (2012–2018) for ELSA. Participants aged < 60 years and those with missing data on digital exclusion or loneliness were excluded. The final analytical sample comprised 13,061 participants (25,682 observations) from CHARLS, 18,291 participants (39,536 observations) from HRS, and 7,838 participants (22,038 observations) from ELSA. The detailed participant selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of the study population screening

Digital exclusion

Data on digital exclusion were collected via self-administered questionnaires. In CHARLS, participants answered: “Have you used the internet in the past month?” In HRS, digital exclusion was assessed with: “Do you regularly use the internet (or the World Wide Web) to send/receive emails or for other purposes such as shopping, searching for information, or making travel reservations [6, 13, 14]?” For ELSA, participants reported internet usage frequency on a six-point scale ranging from 1 (“daily or almost daily”) to 6 (“never”). Responses of “no” (CHARLS, HRS) or “less than once a week” (ELSA) were categorised as digital exclusion, while “yes” (CHARLS, HRS) or usage at least once weekly (ELSA) indicated digital inclusion [14].

Loneliness

Loneliness was operationalised differently across studies. CHARLS assessed loneliness through the question: “How often did you feel lonely in the past week?” with responses categorised as “sometimes” (1–2 days), “often” (3–4 days), or “always” (5–7 days), indicating loneliness [15]. In HRS and ELSA, the Three-Item Loneliness Scale (T-ILS) [16] evaluated loneliness through self-rated assessments of social relationship satisfaction, perceived isolation, and sense of belonging. Each item was scored 1–3 points, yielding total scores of 3–9, with scores ≥ 6 (averaging ≥ 2 per item) classified as loneliness [17].

Covariates

Covariates, identified through literature review to address potential confounding between digital exclusion and loneliness, included age; gender [18]; educational attainment [19]; marital/partnered status [20]; employment status [21]; self-rated health [22]; cohabitation with children [23]; income.

The baseline characteristics of participants in CHARLS, HRS, and ELSA were described separately. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages.

Statistical analysis

To address intra-cohort correlations arising from repeated measurements, generalized estimating equations (GEE) with binary logistic regression and exchangeable correlation structures were employed to examine the association between digital exclusion and loneliness. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Robustness of this association was assessed through three sequential adjustment models: Model 1 (unadjusted, no covariates), Model 2 (adjusted for Age; Gender; Education; Marital status), and Model 3 (fully adjusted for Employment status; Self-rated health; Cohabitation with children; and Income). Missing covariate data were handled using multiple imputation by chained equations, with missingness rates summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Given baseline characteristic differences between digitally excluded and included groups in this observational study, propensity score matching (PSM) was implemented to balance participant characteristics. Cohort-specific matching ratios and caliper widths were applied: CHARLS (1:10 ratio, caliper = 0.01), HRS (1:1 ratio, caliper = 0.01), and ELSA (1:2 ratio, caliper = 0.01). Post-matching associations were analyzed using binary logistic regression.

Sensitivity analyses included: (1) Validation of causal relationships using CHARLS Wave 1 as baseline and Wave 2 as follow-up (Supplementary Table 2), with digital exclusion transitions categorized into four states across Waves 3–5: persistent digital exclusion, transition from exclusion to inclusion, persistent digital inclusion, and transition from inclusion to exclusion (Supplementary Table 3). Supplementary Table 4 evaluates associations between these transition states and loneliness. (2) Stratified analyses examining associations across subgroups defined by age, gender, educational attainment, employment status, marital/partnered status, cohabitation with children, and income (Supplementary S4).

For all reported statistical analyses, two-tailed P-values were employed, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of participants across the three studies. The digitally excluded group consistently demonstrated a higher mean age compared to the digitally included group: CHARLS (68.38 ± 6.59 vs. 65.76 ± 5.15), HRS (74.73 ± 8.62 vs. 70.01 ± 7.35), and ELSA (75.23 ± 7.88 vs. 69.33 ± 6.57). Males represented a higher proportion in the digitally excluded group: 50.60% (CHARLS), 59.21% (HRS), and 62.00% (ELSA). Substantial cross-national disparities in digital exclusion prevalence were observed: 96.20% (CHARLS), 52.13% (HRS), and 33.54% (ELSA). Loneliness rates among digitally excluded older adults showed minimal variation: 31.41% (CHARLS), 28.68% (HRS), and 25.58% (ELSA).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| CHARLS | HRS | ELSA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| digital inclusion | digital exclusion | digital inclusion | digital exclusion | digital inclusion | digital exclusion | |

| Total n (observations) | 976(3.8%) | 24,706(96.20%) | 18,926(47.87%) | 20,610(52.13%) | 14,646(66.46%) | 7392(33.54%) |

| Age | 65.76 ± 5.15 | 68.38 ± 6.59 | 70.01 ± 7.35 | 74.73 ± 8.62 | 69.33 ± 6.57 | 75.23 ± 7.88 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 361 (36.99%) | 12,501 (50.60%) | 10,923 (57.71%) | 12,203 (59.21%) | 7701 (52.58%) | 4583 (62.00%) |

| Female | 615 (63.01%) | 12,205 (49.40%) | 8003 (42.29%) | 8407 (40.79%) | 6945 (47.42%) | 2809 (38.00%) |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than lower secondary education | 524 (53.69%) | 23,003 (93.11%) | 711 (3.76%) | 6236 (30.26%) | 2366 (16.15%) | 4104 (55.52%) |

| Upper secondary & vocational training | 319 (32.68%) | 1384 (5.60%) | 11,115 (58.73%) | 12,369 (60.01%) | 8315 (56.77%) | 2935 (39.71%) |

| Tertiary education | 133 (13.63%) | 319 (1.29%) | 7100 (37.51%) | 2005 (9.73%) | 3965 (27.07%) | 353 (4.78%) |

| Marital/partnered status | ||||||

| Unmarried/Divorced/widowed/others | 104 (10.66%) | 5078 (20.55%) | 6167 (32.58%) | 10,056 (48.79%) | 4351 (29.71%) | 3372 (45.62%) |

| Married/with a partner | 872 (89.34%) | 19,628 (79.45%) | 12,759 (67.42%) | 10,554 (51.21%) | 10,295 (70.29%) | 4020 (54.38%) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| No | 681 (69.77%) | 11,734 (47.49%) | 12,292 (64.95%) | 17,222 (83.56%) | 11,096 (75.76%) | 6761 (91.46%) |

| Yes | 295 (30.23%) | 12,972 (52.51%) | 6634 (35.05%) | 3388 (16.44%) | 3550 (24.24%) | 631 (8.54%) |

| Cohabitation with children | ||||||

| No | 623 (63.83%) | 13,953 (56.48%) | 10,052 (53.11%) | 7531 (36.54%) | 12,126 (82.79%) | 6262 (84.71%) |

| Yes | 353 (36.17%) | 10,753 (43.52%) | 8874 (46.89%) | 13,079 (63.46%) | 2520 (17.21%) | 1130 (15.29%) |

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| health | 315 (32.27%) | 5023 (20.33%) | 9391 (49.62%) | 5856 (28.41%) | 6768 (46.21%) | 1935 (26.18%) |

| ill-health | 661 (67.73%) | 19,683 (79.67%) | 9535 (50.38%) | 14,754 (71.59%) | 7878 (53.79%) | 5457 (73.82%) |

| Income | ||||||

| low | 66 (6.76%) | 8492 (34.37%) | 3228 (17.06%) | 9947 (48.26%) | 3621 (24.72%) | 3724 (50.38%) |

| medium | 190 (19.47%) | 8338 (33.75%) | 6119 (32.33%) | 7061 (34.26%) | 4822 (32.92%) | 2525 (34.16%) |

| high | 720 (73.77%) | 7876 (31.88%) | 9579 (50.61%) | 3602 (17.48%) | 6203 (42.35%) | 1143 (15.46%) |

| loneliness | ||||||

| No | 794 (81.35%) | 16,946 (68.59%) | 14,955 (79.02%) | 14,700 (71.32%) | 12,315 (84.08%) | 5501 (74.42%) |

| Yes | 182 (18.65%) | 7760 (31.41%) | 3971 (20.98%) | 5910 (28.68%) | 2331 (15.92%) | 1891 (25.58%) |

CHARLS China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, HRS Health and Retirement Study,ELSA English Longitudinal Study of Ageing

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) in case of normal distribution and categorical variables are presented as counts (percentages)

Model 3: adjust for Age; Gender; Education; marital/partnered status; employment status; cohabitation with children; Self-rated health; Income

Table 2 displays participant characteristics after propensity score matching. After implementing cohort-specific matching ratios (CHARLS 1:10, HRS 1:1, ELSA 1:2), between-group differences in Age; Gender; Education; Marital status; Employment status; Cohabitation with children; Self-rated health; and Income were substantially reduced across all cohorts.

Table 2.

The characteristics of the population after propensity score matching

| CHARLS | HRS | ELSA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| digital inclusion | digital exclusion | Standardized diff. | digital inclusion | digital exclusion | Standardized diff. | digital inclusion | digital exclusion | Standardized diff. | |

| N | 266 | 2660 | 4700 | 4700 | 1428 | 714 | |||

| Age | 65.33 ± 4.84 | 67.42 ± 7.63 | 0.3267 | 68.00 ± 7.11 | 69.29 ± 8.03 | 0.1698 | 66.47 ± 5.47 | 66.57 ± 5.66 | 0.0176 |

| Gender | 0.1336 | 0.0236 | 0.0702 | ||||||

| Male | 116 (43.6) | 1337 (50.3) | 2699 (57.4) | 2644 (56.3) | 728 (51) | 389 (54.5) | |||

| Female | 150 (56.4) | 1323 (49.7) | 2001 (42.6) | 2056 (43.7) | 700 (49) | 325 (45.5) | |||

| Education | |||||||||

| Less than lower secondary education | 233 (87.6) | 2420 (91) | 0.1096 | 352 (7.5) | 678 (14.4) | 0.2234 | 130 (9.1) | 74 (10.4) | 0.0425 |

| Upper secondary & vocational training | 32 (12) | 223 (8.4) | 0.1207 | 3353 (71.3) | 3191 (67.9) | 0.0750 | 1049 (73.5) | 520 (72.8) | 0.0142 |

| Tertiary education | 1 (0.4) | 17 (0.6) | 0.0370 | 995 (21.2) | 831 (17.7) | 0.0883 | 249 (17.4) | 120 (16.8) | 0.0167 |

| Marital/partnered status | 0.1295 | 0.1455 | 0.0273 | ||||||

| Unmarried/Divorced/widowed/others | 43 (16.2) | 564 (21.2) | 1978 (42.1) | 1646 (35) | 452 (31.7) | 217 (30.4) | |||

| Married/with a partner | 223 (83.8) | 2096 (78.8) | 2722 (57.9) | 3054 (65) | 976 (68.3) | 497 (69.6) | |||

| Employment status | 0.0008 | 0.0791 | 0.0294 | ||||||

| No | 145 (54.5) | 1451 (54.5) | 3259 (69.3) | 3085 (65.6) | 1007 (70.5) | 513 (71.8) | |||

| Yes | 121 (45.5) | 1209 (45.5) | 1441 (30.7) | 1615 (34.4) | 421 (29.5) | 201 (28.2) | |||

| Cohabitation with children | 0.2240 | 0.1510 | 0.0240 | ||||||

| No | 149 (56) | 1194 (44.9) | 2363 (50.3) | 2010 (42.8) | 1118 (78.3) | 566 (79.3) | |||

| Yes | 117 (44) | 1466 (55.1) | 2337 (49.7) | 2690 (57.2) | 310 (21.7) | 148 (20.7) | |||

| Self-rated health | 0.0049 | 0.0360 | 0.0239 | ||||||

| ill-health | 79 (29.7) | 784 (29.5) | 1846 (39.3) | 1929 (41) | 655 (45.9) | 319 (44.7) | |||

| health | 187 (70.3) | 1876 (70.5) | 2854 (60.7) | 2771 (59) | 773 (54.1) | 395 (55.3) | |||

| Income | |||||||||

| low | 36 (13.5) | 499 (18.8) | 0.1424 | 1342 (28.6) | 1460 (31.1) | 0.0549 | 420 (29.4) | 223 (31.2) | 0.0396 |

| medium | 90 (33.8) | 779 (29.3) | 0.0980 | 1889 (40.2) | 1819 (38.7) | 0.0305 | 492 (34.5) | 249 (34.9) | 0.0088 |

| high | 140 (52.6) | 1382 (52) | 0.0135 | 1469 (31.3) | 1421 (30.2) | 0.0221 | 516 (36.1) | 242 (33.9) | 0.0470 |

| loneliness | 0.0977 | 0.0482 | 0.0565 | ||||||

| No | 204 (76.7) | 1927 (72.4) | 3539 (75.3) | 3440 (73.2) | 1141 (79.9) | 554 (77.6) | |||

| Yes | 62 (23.3) | 733 (27.6) | 1161 (24.7) | 1260 (26.8) | 287 (20.1) | 160 (22.4) | |||

CHARLS China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study,HRS Health and Retirement Study,ELSA English Longitudinal Study of Aging

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) in case of normal distribution and categorical variables are presented as counts (percentages)

CHARLS (1:10 ratio, caliper=0.01), HRS (1:1 ratio, caliper=0.01), and ELSA (1:2 ratio, caliper=0.01)

Table 3 details the associations between digital exclusion and loneliness. In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), statistically significant associations persisted despite attenuation from Models 1–2: CHARLS (OR = 1.22), HRS (OR = 1.16), and ELSA (OR = 1.30). This translates to a 22% increased loneliness risk for digitally excluded Chinese older adults, 16% for Americans, and 30% for British individuals relative to their digitally included counterparts. These associations remained significant after propensity score matching: CHARLS (OR = 1.33), HRS (OR = 1.23), and ELSA (OR = 1.23).

Table 3.

Associations between digital exclusion and loneliness

| CHARLS | HRS | ELSA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR/β (95% CI) P value | OR/β (95% CI) P value | OR/β (95% CI) P value | ||

| loneliness | Model 1 | 1.69 (1.45, 1.97) <0.0001 | 1.44 (1.37, 1.51) <0.0001 | 1.62 (1.49, 1.76) <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1.36 (1.15, 1.60) 0.0003 | 1.26 (1.19, 1.33) <0.0001 | 1.37 (1.25, 1.51) <0.0001 | |

| Model 3 | 1.22 (1.03, 1.44) 0.0208 | 1.16 (1.09, 1.23) <0.0001 | 1.30 (1.19, 1.43) <0.0001 | |

| Match | Model 1 | 1.97 (1.59, 2.43) <0.0001 | 1.12 (1.02, 1.22) 0.0196 | 1.32 (1.15, 1.51) <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1.41 (1.13, 1.77) 0.0024 | 1.20 (1.09, 1.32) 0.0002 | 1.30 (1.13, 1.51) 0.0004 | |

| Model 3 | 1.33 (1.06, 1.67) 0.0150 | 1.23 (1.11, 1.35) <0.0001 | 1.23 (1.06, 1.43) 0.0055 |

CHARLS China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study,HRS Health and Retirement Study ,ELSA English Longitudinal Study of Ageing

Model 1: unadjusted

Model 2: adjust for Age; Gender; Education; marital/partnered statusModel 3: adjust for Age; Gender; Education; marital/partnered status; employment status; cohabitation with children; Self-rated health; Income

Online Supplementary Table S2 shows baseline characteristics in CHARLS Waves 1–2. The digitally excluded versus included groups comprised 6,788 vs. 79 participants at Wave 1 and 8,940 vs. 257 at Wave 2. Supplementary Table S3 details digital exclusion transitions after 2-year follow-up: persistent digital exclusion (n = 5,035), transition to inclusion (n = 50), persistent inclusion (n = 40), and transition to exclusion (n = 17). Supplementary Table S4 demonstrates that after covariate adjustment, persistent digital exclusion was associated with significantly higher loneliness risk compared to persistent inclusion (HR = 2.37, 95% CI 1.05–5.34).

Supplementary Table 5 reveals robust positive associations (OR > 1; 95% CIs excluding 1) across nearly all stratified subgroups (P-interaction > 0.05). Notably, marital status significantly modified associations in HRS (P = 0.0069) and ELSA (P = 0.0052). Married/partnered individuals exhibited higher vulnerability: HRS (OR = 1.38 vs. 1.22 in unmarried), ELSA (OR = 1.62 vs. 1.30), potentially reflecting intra-household disparities in digital resource allocation.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between digital exclusion and loneliness among older adults using three multinational longitudinal surveys (CHARLS, HRS, ELSA), comprising 39,190 participants (87,256 observations). The findings revealed substantial cross-national disparities in digital exclusion prevalence: CHARLS (96.20%), HRS (52.13%), and ELSA (33.54%), with China exhibiting the highest rate. After adjusting for covariates (e.g., age, gender, education), generalized estimating equations (GEE) models demonstrated significant positive associations between digital exclusion and loneliness: CHARLS (OR = 1.22), HRS (OR = 1.16), and ELSA (OR = 1.30). These associations remained statistically significant after propensity score matching (PSM): CHARLS (OR = 1.33), HRS (OR = 1.23), and ELSA (OR = 1.23). Collectively, digital exclusion emerges as a prevalent phenomenon strongly linked to loneliness in ageing populations, supporting digital inclusion strategies as a viable pathway for mitigating psychological distress [7].

Our results align with recent research exploring digital technology use, social isolation/loneliness, and health outcomes in older adults. Prior studies predominantly focused on single-country contexts. For instance, research in developed nations observed that limited internet engagement correlated with heightened loneliness and weaker social connections [24, 25]. K. Zhang et al.‘s investigation of U.S. older adults (2014–2018, N = 3,026) found digital inclusion reduced loneliness through enhanced social support and life purpose (β =−0.044 to−0.014) [25],consistent with our findings. This study extends this evidence by demonstrating digital exclusion’s universally detrimental impact across both developed and developing nations.

Notably, China (CHARLS) exhibited an exceptionally high digital exclusion rate (96.20%)—significantly exceeding the U.S. (52.13%) and U.K. (33.54%). This disparity is closely tied to educational inequities: 93.11% of China’s digitally excluded group had less than junior high education versus 53.70% in the included group. Educational deprivation not only impedes technological literacy but may also erode social participation confidence, reinforcing the “digital capability–social capital” cumulative cycle [7]. Structural age- and health-related disadvantages further compound exclusion: digitally excluded groups were older (e.g., China: 68.38 vs. 65.76 years) and reported poorer self-rated health (e.g., 79.67% “good health” in China’s excluded group vs. 67.73% in included). This aligns with the “health selection effect“ [26]—functional decline and chronic conditions directly hinder technology adoption while reducing motivation for digital engagement [27]. Disrupted family support networks intensify exclusion: 56.48% of China’s excluded group lived without children (vs. 43.52% in included), while solitary living characterized excluded older adults in the U.S. (36.54%) and U.K. (84.71%). Absent intergenerational support may limit technology access channels [28], particularly in China where family-mediated technical assistance remains pivotal, leaving unaccompanied elders vulnerable to becoming “digital castaways.“ [29] Gender differences revealed cultural specificity: females constituted 63.01% of China’s included group but only 49.40% of the excluded—contrasting with male-dominated exclusion in the U.S. (59.21%) and U.K. (62.00%). This suggests Chinese women leverage offspring for technical support within caregiving roles, while men disengage earlier due to traditional social norms [30].

This study found digital exclusion to be a significant independent risk factor across all three nations. In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), the odds ratios (OR) for loneliness among digitally excluded older adults were 1.22 (95% CI: 1.03–1.44) in China (CHARLS), 1.16 (1.09–1.23) in the United States (HRS), and 1.30 (1.19–1.43) in the United Kingdom (ELSA), indicating a 16–30% increased loneliness risk, with the highest effect size observed in the U.K. Digitally excluded individuals face dual deprivation: they are unable to maintain social networks through digital communication tools [31] and lack access to health information and social support platforms [32]. This compounded exclusion mechanism significantly amplifies loneliness risks [6].

China’s elevated OR (1.22) reflects the tension between its exceptionally low internet penetration rate (3.8%) and strong family-orientated cultural norms. While higher digital inclusion rates in the U.S. and U.K. partially mitigate exclusion effects, the prevalence of solitary living (84.71% among the U.K.’s excluded group) remains a critical risk factor. These findings call for policy designs that balance technological accessibility with cultural adaptation: China should prioritize community-family collaborative digital literacy programs, whereas the U.S. and U.K. need to integrate digital tools into elderly healthcare systems to resolve the dual “digital-social isolation” experienced by older adults living alone.

Stratified analyses revealed that the association between digital exclusion and loneliness remained significant across most subgroups. However, marital status emerged as an effect modifier among U.S. older adults (P = 0.0036), with unmarried/widowed individuals showing a lower increase in loneliness risk (OR = 1.25) compared to their married counterparts (OR = 1.49). This suggests marital status may serve as a critical buffer mechanism through social support [33]. Existing evidence indicates that married individuals predominantly rely on their spouses as primary social networks, rendering them more vulnerable when digital exclusion disrupts traditional communication channels and alternative social supports are insufficient [34]. Conversely, unmarried/widowed groups, often adapting to prolonged solitary living, may develop more robust non-digital compensatory social strategies [35] or exhibit lower baseline dependence on digital technology [36], thereby mitigating the psychosocial impact of digital exclusion. Notably, as a multidimensional social exclusion phenomenon [7], digital exclusion likely intensifies loneliness by reducing social participation and limiting resource accessibility, with marital status acting as a key contextual moderator in this pathway [34, 37].

Collectively, digital exclusion represents a significant public health challenge for older adults, with its pervasiveness and multidimensionality potentially driving social marginalization and deteriorating mental health [5]. The exceptionally high exclusion rate in China (96.20%) underscores its severity in developing contexts. Regional variations are critical: digital exclusion may compound isolation through structural barriers (e.g., device shortages) and psychological mechanisms (e.g., eroded social connectivity) [5]. At its core, digital exclusion encompasses both technological deficits and informational isolation, directly restricting older adults’ engagement with the digital world and exacerbating loneliness [38]. Universal positive associations across nations suggest macro-level mechanisms (e.g., national digital infrastructure gaps) and micro-level drivers (e.g., limited digital literacy) collectively fuel social disconnection. For instance, China’s high exclusion aligns with educational disparities, mirroring the negative impact of digital disconnection on loneliness observed here. Thus, advancing digital inclusion through device access and skill training could bridge technological divides while promoting successful aging and psychological well-being.

This study possesses two key strengths. First, multinational data from CHARLS, HRS, and ELSA—totaling 39,190 participants—enhance statistical reliability and generalizability. Second, methodological integration of GEE and PSM effectively controlled confounders, providing robust bias-adjusted evidence. Four limitations warrant acknowledgment: (1)Definitional constraints: Digital exclusion was defined solely by self-reported non-use of the internet, potentially introducing reporting bias and overlooking multidimensional aspects (e.g., skill proficiency).(2)Causal inference: Longitudinal analysis was restricted to CHARLS data, limiting causal claims; experimental studies are needed to confirm directionality.(3)Methodological heterogeneity: Variations in loneliness assessments and study waves across cohorts may affect comparability.(4)Residual confounding: Unmeasured variables (e.g., social activity patterns) could contribute to bias.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that a substantial proportion of older adults experience digital exclusion, with this phenomenon being particularly pronounced in China. Digital exclusion exhibits a consistent positive association with loneliness across sociocultural contexts. These results collectively indicate that enhancing digital inclusion may serve as a critical public health strategy to mitigate loneliness and improve psychological well-being in aging populations. Future interventions should develop culturally adapted, integrated technology-society frameworks to address region-specific exclusion pathway.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the research teams of CHARLS, HRS, ELSA for the study concept and design.

Authors’ contributions

S.D.Z. completed the research design, data statistics and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Y.Q.W reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work.

Data availability

The original survey datasets from CHARLS, HRS and ELSA are all free of charge and available from the Global Ageing Data Portal (https://g2agi ng.org/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We utilized de-identified data from public databases, including CHARLS, HRS, ELSA. The ethical approval was covered by the original surveys and was not necessary for the present study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mehra A, Agarwal A, Bashar M, Avasthi A, Chakravarty R, Grover S. Prevalence of Loneliness in Older Adults in Rural Population and Its Association with Depression and Caregiver Abuse. Indian J Psychol Med. 2024;46(6):564–9. 10.1177/02537176241231060S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Lau J, Koh WL, Ng JS, Khoo AM, Tan KK. Understanding the mental health impact of COVID-19 in the elderly general population: A scoping review of global literature from the first year of the pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2023;329:115516. 10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115516. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Masoudi N, Sarbazi E, Soleimanpour H, et al. Loneliness and its correlation with self-care and activities of daily living among older adults: a partial least squares model. BMC Geriatr Jul. 2024;20(1):621. 10.1186/s12877-024-05215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jentoft EE. Technology and older adults in British loneliness policy and political discourse. Front Digit Health. 2023;5:1168413. 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1168413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang Y, Shao Y, Wang M. The involuntary experience of digital exclusion among older adults: A taxonomy and theoretical framework. Am Psychol. 2025;30. 10.1037/amp0001502. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Wang Y, Wu Z, Duan L, et al. Digital exclusion and cognitive impairment in older people: findings from five longitudinal studies. BMC Geriatr. 2024;(1): 406. 10.1186/s12877-024-05026-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ge H, Li J, Hu H, Feng T, Wu X. Digital exclusion in older adults: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2025;168: 105082. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2025.105082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mubarak F, Suomi R. Elderly forgotten?? digital exclusion in the information age and the rising grey digital divide. Inquiry Jan-Dec. 2022;59:469580221096272. 10.1177/00469580221096272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latikka R, Rubio-Hernandez R, Lohan ES, et al. Older adults’ loneliness, social isolation, and physical information and communication technology in the era of ambient assisted living: A systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res Dec. 2021;30(12):e28022. 10.2196/28022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):61–8. 10.1093/ije/dys203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR. Cohort profile: the health and retirement study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):576–85. 10.1093/ije/dyu067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J. Cohort profile: the English longitudinal study of ageing. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1640–8. 10.1093/ije/dys168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan S, Chen D, Wang J, et al. Digital exclusion and cognitive function in elderly populations in developing countries: insights derived from 2 longitudinal cohort studies. J Med Internet Res Nov. 2024;15:26:e56636. 10.2196/56636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu X, Yao Y, Jin Y. Digital exclusion and functional dependence in older people: findings from five longitudinal cohort studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;54: 101708. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aßmann ES, Ose J, Hathaway CA, et al. Risk factors and health behaviors associated with loneliness among cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Behav Med. 2024;47(3):405–21. 10.1007/s10865-023-00465-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin CY, Tsai CS, Fan CW, et al. Psychometric evaluation of three versions of the UCLA loneliness scale (Full, Eight-Item, and three-Item versions) among sexual minority men in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;1(13). 10.3390/ijerph19138095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Victor CR, Rippon I, Barreto M, Hammond C, Qualter P. Older adults’ experiences of loneliness over the lifecourse: an exploratory study using the BBC loneliness experiment. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Sep-Oct. 2022;102:104740. 10.1016/j.archger.2022.104740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freilich CD, Mann FD, South SC, Krueger RF. Comparing phenotypic, genetic, and environmental associations between personality and loneliness. J Res Pers. 2022;101. 10.1016/j.jrp.2022.104314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Heponiemi T, Jormanainen V, Leemann L, Manderbacka K, Aalto AM, Hyppönen H. Digital divide in perceived benefits of online health care and social welfare services: National longitudinal survey study. J Med Internet Res Jul. 2020;7(7):e17616. 10.2196/17616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norlin J, McKee KJ, Lennartsson C, Dahlberg L. Quantity and quality of social relationships and their associations with loneliness in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2025. 10.1080/13607863.2025.2460068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buecker S, Denissen JJA, Luhmann M. A propensity-score matched study of changes in loneliness surrounding major life events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2021;121(3):669–90. 10.1037/pspp0000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan R, Liu X, Xue R, et al. Association between internet exclusion and depressive symptoms among older adults: panel data analysis of five longitudinal cohort studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;75: 102767. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang R, Wang H, Edelman LS, et al. Loneliness as a mediator of the impact of social isolation on cognitive functioning of Chinese older adults. Age Ageing. 2020;(4):599–604. 10.1093/ageing/afaa020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kung CSJ, Steptoe A. Internet use and psychological wellbeing among older adults in england: a difference-in-differences analysis over the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med Aug. 2023;53(11):5356–8. 10.1017/s0033291722003208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang K, Burr JA, Mutchler JE, Lu J. Pathways linking information and communication technology use and loneliness among older adults: evidence from the health and retirement study. Gerontologist. 2024(4). 10.1093/geront/gnad100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Wei Y, Guo X. Impact of smart device use on objective and subjective health of older adults: findings from four provinces in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1118207. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1118207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu S, Lu Y, Wang D, et al. Impact of digital health literacy on health-related quality of life in Chinese community-dwelling older adults: the mediating effect of health-promoting lifestyle. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1200722. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1200722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phang JK, Kwan YH, Yoon S, et al. Digital intergenerational program to reduce loneliness and social isolation among older adults: realist review. JMIR Aging Jan 4. 2023;6:e39848. 10.2196/39848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, He R. A study on digital inclusion of Chinese rural older adults from a life course perspective. Front Public Health. 2022;10:974998. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.974998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu H, Xu W. Socioeconomic differences in digital inequality among Chinese older adults: results from a nationally representative sample. PLoS One. 2024;19(4):e0300433. 10.1371/journal.pone.0300433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gadbois EA, Jimenez F, Brazier JF, et al. Findings from talking tech: a technology training pilot intervention to reduce loneliness and social isolation among homebound older adults. Innov Aging. 2022;6(5): igac040. 10.1093/geroni/igac040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang H, Valimaki M, Li X, et al. Barriers and facilitators of digital interventions use to reduce loneliness among older adults: a protocol for a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e067858. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birditt KS, Manalel JA, Sommers H, Luong G, Fingerman KL. Better off alone: daily solitude is associated with lower negative affect in more conflictual social networks. Gerontologist. 2019(6). 10.1093/geront/gny060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Vitman Schorr A, Khalaila R. Aging in place and quality of life among the elderly in europe: A moderated mediation model. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Jul-Aug. 2018;77:196–204. 10.1016/j.archger.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Copeland M, Nowak G 3rd, Chopik WJ, Oh J. Marital status differences in loneliness among older Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2023. 10.1007/s11113-023-09822-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Sandoval MH, Alvear Portaccio ME. Marital status, living arrangements and mortality at older ages in chile, 2004–2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health Oct. 2022;22(21). 10.3390/ijerph192113733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Mishra B, Pradhan J, Dhaka S. Identifying the impact of social isolation and loneliness on psychological well-being among the elderly in old-age homes of India: the mediating role of gender, marital status, and education. BMC Geriatr. 2023;(1): 684. 10.1186/s12877-023-04384-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang L, Lynch C, Lee JT, Oldenburg B, Haregu T. Understanding the association between home broadband connection and Well-Being among Middle-Aged and older adults in china: nationally representative panel data study. J Med Internet Res Feb. 2025;10:27:e59023. 10.2196/59023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original survey datasets from CHARLS, HRS and ELSA are all free of charge and available from the Global Ageing Data Portal (https://g2agi ng.org/).