Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Aging is the primary risk factor for atherosclerosis, a degenerative process regulated by immune cells and the leading cause of death worldwide. Previous studies on premature aging syndromes have linked atherosclerosis to defects in A-type lamins, key nuclear envelope components. However, whether these defects influence atherosclerosis during normal aging remains unexplored. Here, we examined how aging affects lamin A/C expression in circulating leukocytes and investigated the impact of manipulating their expression in hematopoietic cells on their function and atherosclerosis progression.

METHODS:

Flow cytometry assessed lamin A/C expression in human circulating leukocytes. Bone marrow from donor mice was transplanted into lethally irradiated, Ldlr−/−-deficient mice to study leukocyte extravasation into the vessel wall via intravital microscopy in the cremaster muscle, and high-fat-diet–induced atherosclerosis via Oil Red O staining of the aorta and carotid arteries. Single-cell RNA sequencing of the aorta was conducted to identify transcriptional changes associated with hematopoietic cell lamin A/C gain-of-function or loss-of-function.

RESULTS:

Human aging is associated with lower levels of lamin A/C expression in blood-borne leukocytes. To evaluate the functional relationship between hematopoietic lamin A/C expression and atherosclerosis development, we used Lmna-null mice and Lmnatg mice, the latter being the first in vivo model of lamin A gain-of-function. Transplanting lamin A/C–deficient bone marrow into Ldlr−/− mice increased leukocyte extravasation into the vessel wall and accelerated atherosclerosis. Conversely, transplantation of bone marrow overexpressing lamin A into Ldlr−/− receptor mice reduced leukocyte extravasation and atherosclerosis. Single-cell RNA sequencing of atherosclerotic mouse aorta revealed that alterations to hematopoietic cell lamin A/C expression primarily modify the transcriptome of immune cell populations and endothelial cells, affecting their functionality.

CONCLUSIONS:

We suggest that the age-related decline in lamin A/C expression in blood-borne immune cells contributes to increased leukocyte extravasation and atherosclerosis, highlighting lamin A/C as a novel regulator of age-related atherosclerosis.

Keywords: aging, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases, inflammation, lamin type A, single-cell gene expression analysis

Highlights.

Aging in humans is associated with the downregulation of lamin A/C in circulating leukocytes.

The absence of lamin A/C in immune cells increases leukocyte extravasation into the vessel wall and accelerates diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice.

Overexpression of lamin A in immune cells reduces leukocyte extravasation into the vessel wall and diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice.

Gain-of-function and loss-of-function of lamin A/C in hematopoietic cells modify the transcriptome of immune cell populations and endothelial cells.

Preventing age-related lamin A/C downregulation may provide a foundation for developing targeted therapies to mitigate atherosclerosis progression.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, placing a considerable burden on health care systems and government budgets. The most common forms of CVD are coronary heart disease, peripheral artery disease, and stroke. Atherosclerosis, the underlying cause of most cases of CVD, is the result of a chronic inflammatory and fibroproliferative response to vascular injury that leads to the buildup of an atheroma plaque, a deposit of lipids and cells on the arterial wall.1–3

The most important risk factor for CVD is advancing age, which is associated with increased incidence of all clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis.3–5 This is partly due to cumulative exposure to the main traditional risk factors for the development of CVD, such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes. However, multivariable analysis adjusting for traditional risk factors indicates that age makes an independent contribution to the development of subclinical atherosclerosis and clinical atherosclerotic CVD.6–9 A direct promotion of atherosclerosis by aging is also supported by the clinical and epidemiological evidence, thus indicating that there are unidentified age-dependent risk factors that contribute to the development of atherosclerotic CVD. Improvements in health care services and quality of life have increased life expectancy and the number of elderly individuals, who are almost inevitably affected by CVD. This challenging demographic shift requires a redoubling of efforts to uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying age-related CVD, to identify therapeutic targets to address the ongoing aging pandemic.

Previous studies in genetic mouse models of accelerated aging and observational studies in patients with progeroid premature aging syndromes have linked the development of atherosclerosis to defects in the nuclear lamina.10,11 However, whether these defects impact atherosclerosis development during normal aging has remained unexplored. Key components of the nuclear lamina are the A-type lamins, which, in mammals, are encoded by the LMNA gene. This gene gives rise to the isoforms lamin A, lamin C, lamin C2, and lamin AΔ10.12 The major isoforms are lamin A and lamin C (termed collectively lamin A/C), which form type V intermediate filaments that assemble into a complex network closely associated with the inner nuclear membrane, making the nucleus stiffer. Lamin A/C also connects the cytoskeleton to chromatin through interaction with proteins of the LINC (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) complex. In addition to its established roles in regulating cell shape, polarity, and stiffness, lamin A/C also regulates a wide range of cell functions, including chromatin organization, epigenetic regulation, gene transcription, DNA replication, the DNA damage response, and cell differentiation and migration.13–15 While lamin A/C is expressed in most differentiated somatic cells, it is generally not regulated; in contrast, immune cells regulate their lamin A/C protein expression in a highly dynamic manner to perform specific functions, such as activation, differentiation, and migration.16–18 Human and mouse studies have revealed lamin A expression in bone marrow (BM) cells, especially in hematopoietic stem cells,19,20 and lamin A/C-null mice exhibit an aging-like hematopoietic phenotype.20

Here, we show that lamin A/C is downregulated with age in human circulating leukocytes, potentially representing a new pathogenic factor for age-related atherosclerosis. To assess possible functional connections between hematopoietic lamin A/C expression and atherosclerosis development, we conducted studies with Lmna−/− mice21 and Lmnatg mice, a new mouse model that we have generated to allow in vivo gain-of-function studies of lamin A. Using these models, we demonstrate that modulating lamin A/C expression in hematopoietic cells in mice induces multiple transcriptional alterations in immune and nonimmune cell types within the arterial wall, influencing leukocyte recruitment and atherosclerosis development.

Methods

Data Availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, all single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data were deposited at BioStudies-ArrayExpress (E-MTAB-15242), and the code used for scRNA-seq analysis was deposited in GitHub (https://github.com/LAB-VA-CNIC/sc-lmna.TG.OE.HFD). Detailed information on key reagents and animal models is provided in the Major Resources Table (Table S9).

Human Studies

Human blood was obtained from adult cardiology patients and healthy individuals (aged 18–90 years), after signing an informed consent in accordance with local ethics committee guidelines (Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Instituto de Salud Carlos III: CEI PI 44_2015-v3 and Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre: CEI 16/044). Individuals under sexual hormone modulating drug treatment were excluded. For additional demographic data, see Table S1. To assess age-related differences in lamin A/C expression, individuals were stratified into young (19–44 years) and old (67–89 years) groups. The required sample size was estimated to be between 89 and 198 participants based on power analysis for a 2-sample t test with a 2-sided significance level of 0.05 and 80% power. In the absence of prior data, a moderate effect size was assumed, selecting a range of standardized effect sizes (Cohen d) between 0.4 and 0.6.

Human blood was lysed and labeled with the following antibodies against surface markers: A647 (Alexa Fluor 647)-conjugated anti-CD14 (BioLegend Cat 325612, Research Resource Identifiers [RRID]: AB_830685), phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD16 (BioLegend Cat 302056, RRID: AB_2564139), A647-conjugated anti-CD66b (BioLegend Cat 305110, RRID: AB_2563171), phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD3 (BioLegend Cat 300308, RRID: AB_314044), and A647-conjugated anti-CD19 (BioLegend Cat 302220, RRID: AB_389335). After 15 minutes at room temperature (RT), samples were incubated with Becton Dickinson (BD) fluorescence-activated cell sorting lysing solution (Becton Dickinson) for 10 minutes at RT, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes at RT, and incubated with anti-lamin A/C-A488 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology Cat 8617, RRID: AB_10997529). White blood cells (WBCs) were identified by size and complexity: classical monocytes as CD14High and CD16−; intermediate monocytes as CD14High and CD16+; nonclassical monocytes as CD14+ and CD16High; neutrophils as CD66b+; T lymphocytes as CD3+ and CD19−; and B lymphocytes as CD19+ and CD3−. Lamin A/C mean fluorescence intensity was measured for each cell population after subtraction of the nonspecific mean fluorescence intensity of the isotype control (Cell Signaling Technology Cat 97146, RRID: AB_2800275). Data were acquired with BD LSRFortessa and BD FACSymphony cytometers and BD FACSDiva software (RRID: SCR_001456) and were analyzed with FlowJo software (RRID: SCR_008520).

Mice

Atheroprone Ldlr−/− mice were used as recipients in BM transplantation (BMT) experiments. Ldlr−/− mice expressing the CD45.1 epitope were generated by crossing Ldlr−/− mice (RRID: IMSR_JAX:002207) with B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyCrl mice (RRID: IMSR_CRL:494). To generate chimeric Ldlr−/− mice with hematopoietic lamin A/C deficiency or lamin A overexpression, the following mouse strains were used as BM donors: 1) Lmna−/− mice (RRID: IMSR_JAX:009125),21 lacking lamin A/C ubiquitously; and 2) Lmna-OE mice, generated by crossing Vav-iCre (Vav promoter-driven inducible Cre recombinase) mice22 (RRID: IMSR_JAX:008610) with Lmnatg mice (see the following subsection). The myeloid-specific Lmnaflox/flox Rag1−/− model was generated by crossing Rag1−/− mice, which lack mature B and T cells (RRID: IMSR_JAX:002216)23 and Lmnaflox/flox mice, which exhibit lamin A/C deficiency upon Cre-dependent removal of LoxP (Locus of X [cross]-over in P1) sites flacking Lmna exon 6 (RRID: IMSR_JAX:026284).24 All experimental mice were on the C57BL/6J (RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664) genetic background. Male and female mice were used except for intravital microscopy, which was performed in the cremaster muscle of male mice. When experiments included both sexes, sex interactions were assessed. In the absence of sex-related differences, data from males and females were combined to improve statistical power. Experimental mice were separated by sex and housed with a maximum of 5 mice per cage in a specific pathogen-free facility at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares Carlos III. Animal cages were individually ventilated and maintained with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle at 22±2 °C and 50% relative humidity (range, 45%–60%). Mice had ad libitum access to water and food: normal laboratory diet for mice: 5K67 (LabDiet), D184 (SAFE), or Rod18-A (LASQCdiet). Experiments were performed with mice aged 8 to 14 weeks, except for BMT with lamin A/C-null BM, which was obtained from 3- to 4-week-old Lmna−/− mice, because these mice die at 5 to 6 weeks of age.21 All mice were immune-competent and healthy before the experiments described. All experimental mice were euthanized in a CO2 chamber.

Animal experiments conformed to EU Directive 2010/63EU and recommendation 2007/526/EC, codified in Spanish law under Real Decreto 53/2013. Animal protocols were approved by the local ethics committees and the Animal Protection Area of the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (PROEX 71.4/20) and followed the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) reporting guidelines.25

Generation of Lmnatg Mice

The Lmnatg transgenic mouse model was generated using CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9) technology. We used crRNA(402–421) Gt(ROSA)26Sor-809 (sequence GUGUGUGGGCGUUGUCCUGCGUUUUAGAGCUAUGCU) to induce a double-strand break in the mouse Rosa26 locus 62 bases downstream of the XbaI site, the most commonly used site for targeted insertion of foreign sequences at this locus.26 The double-stranded oligo template for homology-directed repair was designed to introduce 2 copies of Lmna cDNA (complementary DNA) inside the Rosa26 locus (via transgene insertion). The construct was flanked by proximal and distal homology arms. The construct is under the control of the CAG (CMV early enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter with rabbit β-globin intron) promoter, which allows ubiquitous expression, followed by a chimeric intron, which is associated with a higher percentage of active transgene expression in mouse lines. This is followed by a transcriptional stop signal flanked by LoxP sequences, followed by 2 copies of the mouse Lmna cDNA (NM_001002011.3). The 2 cDNA sequences are separated by a P2A (porcine teschovirus-1 2A peptide) and T2A (thosea asigna virus 2A peptide) sequence, a bicistronic peptide that mediates polypeptide self-cleavage, increasing the efficiency of coexpression of multiple genes.27 An additional stop codon was added after the cDNA pair, followed by a synthetic polyadenylation signal (bovine growth hormone). Fertilized oocytes (zygotes) were isolated from female mice 24 hours after insemination and cytoplasmatically injected with the following mix in microinjection buffer (10-mmol/L Tris-HCl; pH, 7.5; and 0.1-mmol/L EDTA): 30-ng/μL Streptococcus pyogenes HiFi (high fidelity) Cas9 (3NLS [3 nuclear localization signals]), 0.61-μM sgRNA (single-guide RNA), and 4.5-ng/μL double-stranded DNA donor template. The injected embryos were transferred into the oviducts of ICR/HaJ (Institute of Cancer Research mice, Harlan substrain J) recipient mice (RRID: IMSR_JAX:009122). From the 5 pups that were born, only one carried the transgene inserted in the correct location, as determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping and Sanger sequencing (Supplemental Methods). The sequence was visualized with the sequence alignment function in SnapGene. This mosaic founder Lmnatg mouse was crossed with WT C57BL/6 mice to obtain heterozygous F1 mice. The transgenic Lmnatg mouse line was subsequently established and maintained by further backcrosses with WT C57BL/6J mice.

Mouse Genotyping

Tail snips were obtained at the time of weaning, and DNA was extracted in 50-mmol/L NaOH. Mice were genotyped by PCR using specific primers (Supplemental Methods).

BMT and Atherosclerosis Induction in Mice

Irradiation and BMT were conducted as described.28 Briefly, Ldlr−/− mice expressing the CD45.1 epitope were irradiated with 2 6-Gy doses of 10 minutes each and 3 hours apart at 37 °C with a JL Shephed & Associates 1-68A irradiator with a 1000 Curie Cs-137 source. After no >24 hours, animals were injected in the tail vein with 100-μL BM cells (107 in RPMI [Roswell Park Memorial Institute] or saline) obtained from a pool of 4 femurs and 4 tibias either from Lmna−/− or Lmna-OE− mice or from their respective controls (WT or Lmnatg; all CD45.2). Recipient mice were allocated randomly to experimental or control BM groups. Drinking water was supplemented with antibiotics for 7 days before and after the transplant. After 4 weeks of standard diet, an interval sufficient for BM reconstitution in our experimental conditions, transplanted mice were placed on a high-fat diet (HFD; 10.7% total fat and 0.75% cholesterol, S9167-E011, SSNIFF, Germany) to induce hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis development. Mice were fed the HFD for 6 weeks unless otherwise stated. Transplant efficiency was assessed as the percentage of donor CD45.2 immunoreactive cells in the blood of CD45.1 Ldlr−/− BM recipients, assessed by CD45.2 and CD45.1 immunostaining and flow cytometry. Plasma was obtained by centrifugation of whole blood (2000g, 15 minutes at RT). Plasma lipoproteins were assessed by biochemical analysis with a DIMENSION RxL MAX chemistry analyzer (Siemens).

Flow Cytometry of Mouse Blood and BM

See the Supplemental Methods.

Atherosclerosis Burden Quantification

Aortic arch and carotid artery samples were stained with 0.2% Oil Red O (O0625, Sigma, dissolved in 80% MeOH [methanol]).29 Upon sacrifice, hearts and aortas were perfused in situ with phosphate buffered saline and extracted for fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline overnight at 4 °C. Images for atherosclerosis burden quantification were analyzed using Fiji ImageJ software and quantified through computer-assisted morphometric analysis (SigmaScan pro 5, Systat Software, Inc, San Jose, CA) by an investigator blinded to genotype.

Immunofluorescence of Mouse Blood Cells and Aortas

See the Supplemental Methods.

Intravital Microscopy of the Cremaster Venules

Reconstituted male Ldlr−/− mice were fed the HFD for 12 weeks and used for cremaster muscle intravital microscopy.30 Briefly, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized, placed on an optically clear viewing pedestal, and cut longitudinally with a high-temperature surgical cautery (Lifeline Medical). The corners of the exposed tissue were held in place with surgical suture. Correct temperature and physiological conditions were maintained by continuous tissue perfusion with prewarmed (37 °C) Tyrode’s solution (139-mmol/L NaCl, 3-mmol/L KCl, 17-mmol/L NaHCO3, 12-mmol/L glucose, 3-mmol/L CaCl2, and 1-mmol/L MgCl2). The cremaster microcirculation was visualized with an AXIO Examiner Z.1 work station (Zeiss) mounted on a 3-dimensional motorized stage (Sutter Instrument) and equipped with a CoolSnap HQ2 camera (Photometrics). An APO (apochromatic) 20× NA 1.0 water-immersion objective was used. Images were acquired and processed with Slidebook 5.0 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). Three randomly selected venules were analyzed per mouse, and cells were counted by an investigator blinded to genotype. Leukocytes observed outside the venule lumen and within the muscle were considered migrated.

qPCR and Immunoblotting

See the Supplemental Methods.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

See the Supplemental Methods.

Statistical Analysis

Numerical variables are shown as mean±SEM unless otherwise specified, while frequencies were used to describe categorical variables.

To mitigate the influence of known confounders, human subjects were matched by sex, history of coronary atherosclerotic disease, and the presence of at least 1 other cardiovascular risk factor (ie, high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and smoking). For this purpose, inverse probability weighting was applied using propensity scores and average treatment effect as estimand. The probability of being in each age group was estimated via a logistic regression model including the listed confounders as covariates. The estimated propensity scores were then used to compute stabilized inverse probability weightings, ensuring balance in observed confounders between groups. Covariate balance before and after weighting was assessed using standardized mean differences. To assess age-related differences in lamin A/C expression, linear regression models were fitted with age group as a covariate and the inverse probability weightings as weights. Robust regression was used with the Huber M-estimator to mitigate the influence of outliers. Standard errors were computed using the sandwich estimator to obtain robust P values, addressing potential heteroskedasticity.

In mouse studies, statistical significance of differences in experiments with 2 groups and only 1 variable was assessed by unpaired Student t test (with Welch correction for unequal variance when appropriate) or the Mann-Whitney U test. Differences in experiments with >1 independent variable were evaluated by 2-way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak or Tukey multiple comparison tests. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to study data distribution, and outliers were assessed with the ROUT test (Q=1%).

Statistical analyses for human studies were conducted with R (version 4.1.0), whereas analyses for mouse experiments were conducted with GraphPad Prism (RRID: SCR_002798). For single-cell RNA-seq data, the MAST method and R (version 4.1.0) were used.

Results

Lamin A/C Protein Expression in Circulating Immune Cells Decreases With Human Aging

Human and mouse studies have revealed age-related downregulation of lamin A/C in numerous tissues, including hematopoietic progenitor cells.31,32 To investigate whether similar changes occur in differentiated immune cells, we conducted a flow cytometry analysis of lamin A/C expression in different peripheral WBC populations isolated from young (19–44 years) and old (67–89 years) human study participants. A description of the demographics and cardiovascular risk factors of these individuals is shown in Table S1. We applied inverse probability weighting to mitigate the potential confounding effect of these characteristics over age-related effects (Figure S1). Lamin A/C expression was 17% lower in WBCs from older individuals than in those from younger individuals (Figure 1). This difference was consistent across all cell populations analyzed and reached statistical significance in overall WBCs, neutrophils, and B cells. These results indicate that lamin A/C expression is downregulated in the hematopoietic cell compartment during human aging, aligning with the observed aging-like hematopoietic phenotype in lamin A–deficient mice.20

Figure 1.

Lamin A/C expression in human peripheral blood leukocytes declines with age. Flow cytometry analysis of lamin A/C expression in human blood populations from young and old individuals. Statistical significance was determined by robust linear regression after mitigating confounder effects by inverse probability weighting. MFI indicates mean fluorescence intensity; and WBC, white blood cell.

Absence of Lamin A/C in Hematopoietic Cells Accelerates Atherosclerosis Development in Mice

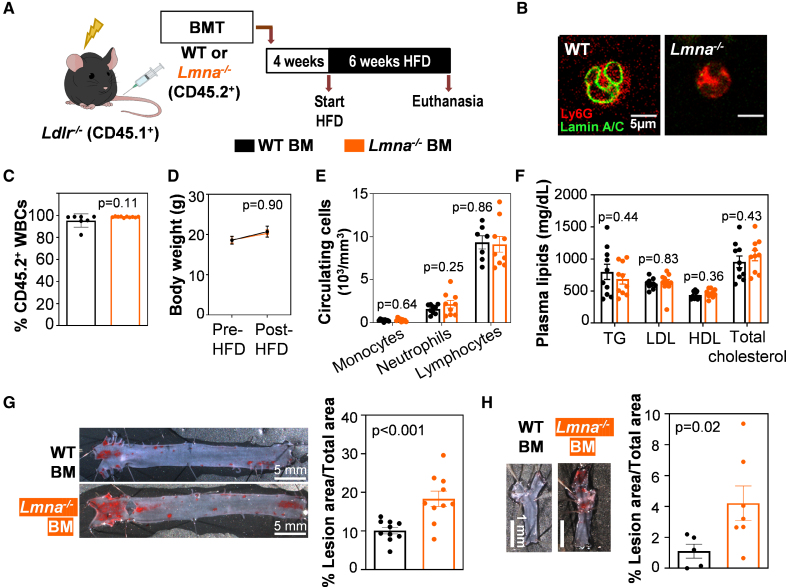

To assess how atherogenesis is affected by the age-associated downregulation of lamin A/C in hematopoietic cells, we used a BMT strategy. Irradiated Ldlr−/−-null mice were reconstituted with BM cells from WT or lamin A/C–deficient (Lmna−/−) donor mice, thus generating atherosclerosis-prone chimeric mice carrying hematopoietic cells with either normal lamin A/C expression or lacking these nuclear proteins, respectively (Figure 2A and 2B). Four weeks after BMT, transplant efficiency was examined by flow cytometry analysis of the CD45 hematopoietic antigen to distinguish between recipient cells (CD45.1+) and donor cells (CD45.2+; see the Methods section). The transplant efficiency was high and comparable between the 2 experimental groups (Figure 2C), thus indicating that lamin A/C deficiency in BM cells does not impair their engraftment or BM reconstitution. To induce atherosclerosis, reconstituted Ldlr−/− mice were fed an HFD for 6 weeks (Figure 2A). The following parameters remained indistinguishable between the 2 groups throughout the study: body weight (Figure 2D), circulating blood cell counts (Figure 2E), and plasma concentrations of triglycerides, LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, and total cholesterol (Figure 2F). Despite this, compared with mice with normal lamin A/C, HFD-fed Ldlr−/− mice carrying Lmna−/− hematopoietic cells developed significantly more atherosclerosis in both the aorta (Figure 2G) and the carotid arteries (Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

Lamin A/C deficiency in hematopoietic cells accelerates atherosclerosis development in atheroprone Ldlr−/− mice. A, Protocol for atherosclerosis studies. B, Representative immunofluorescence images of peripheral blood granulocytes from wild-type (WT) and Lmna−/− mice. The WT cell shows the perinuclear staining characteristic of lamin A/C (green), which is absent in Lmna−/− cells. C, Transplant efficiency shown as the percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the total white blood cell (WBC) population 4 weeks after bone marrow transplantation (BMT), evaluated by flow cytometry (n=7 WT; n=10 Lmna−/−). Statistical differences were assessed by the 2-tailed unpaired t test. D, Body weight evolution over the 6-week fat-feeding period (n=10 WT; n=9 Lmna−/−). Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA. E, Absolute blood cell counts of WBC subpopulations in peripheral blood of reconstituted animals after 6 weeks of fat feeding (n=9, both genotypes). Statistical significance was determined by the multiple t test with the Holm-Sidak method, with α=0.05. Each cell population was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD. F, Fasting plasma lipid concentration after 6 weeks of fat feeding (n=10, both genotypes). Statistical significance was determined by the multiple t test with the Holm-Sidak method, with α=0.05. Each cell population was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD. G, Representative images of Oil Red O–stained aortas and quantification of plaque burden in the aortic arch (n=10, both genotypes). Statistical differences were assessed by the 2-tailed unpaired t test. H, Representative images of Oil Red O–stained right carotid arteries and quantification of plaque burden (n=5 WT; n=7 Lmna−/−). Statistical differences were assessed by the 2-tailed unpaired t test. BM indicates bone marrow; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HFD, high-fat diet; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; and TG, triglyceride.

To better model ≈20% reduction in lamin A/C observed in human WBCs, we performed additional BMT experiments using BM cells from heterozygous Lmna+/- mice, which retain a single functional Lmna allele, to generate chimeric Ldlr−/− mice with a partial reduction in lamin A/C expression (Figure S2A). As observed in previous experimental groups, the following parameters were comparable between groups: hematologic counts (Figure S2B), transplant efficiency (Figure S2C), body weight (Figure S2D), and plasma lipid levels (Figure S2E). Despite similar metabolic profiles, Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with Lmna+/- hematopoietic cells exhibited a 31% increase in aortic atherosclerotic lesion size compared with those receiving WT BM cells (Figure S2F). Although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07), the trend suggests that even a partial reduction in lamin A/C expression may be sufficient to promote atherosclerosis development.

Overexpression of Lamin A in Hematopoietic Cells Delays Mouse Atherosclerosis

To test whether atherosclerosis could be prevented by increasing lamin A expression in hematopoietic cells, we generated a transgenic mouse model to allow lamin A overexpression upon Cre-recombinase expression. We opted to overexpress lamin A alone, rather than lamin C or both isoforms, because lamin A is the predominant A-type lamin isoform in many tissues.33 Consistent with these previous findings, we found higher expression of lamin A than lamin C in the BM and peripheral blood cells of WT mice (Figure S3A). Using CRISPR/Cas9-directed mutagenesis, we inserted 2 copies of the mouse Lmna cDNA into the Rosa26 locus to generate Lmnatg mice (Figure 3A; Figure S3B). The cDNA sequence was preceded by a transcriptional stop signal flanked by LoxP sequences, allowing us to control the timing and location of lamin A overexpression in a Cre recombinase–dependent manner. Proper transgene insertion was confirmed by PCR (Figure S3C and S3D) and validated by Sanger DNA sequencing (Figure S3E). The transgene was maintained in heterozygosis through backcrosses with WT mice on a C57BL/6 genetic background. To assess potential off-target (OT) effects in Lmnatg mice, we used the online Off-Spotter and CRISPOR tools. Compared with the 20-mer sgRNA used for CRISPR/Cas9-dependent editing, this analysis identified 181 mouse genomic sequences with 2, 3, or 4 mismatches (2, 25, and 154 sequences, respectively; Figure S4A). We selected for OT analysis 2 sequences with 3 mismatches (OT-4 and OT-8) and 8 with 4 mismatches (OT-1, OT-2, OT-3, OT-5, OT-6, OT-7, OT-9, and OT-10; Figure S4B). These sequences were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from both WT and Lmnatg mice. The PCR products showed identical DNA sequences in all mice (Figure S4C), indicating the absence of OT effects.

Figure 3.

Generation of transgenic Lmna-OE mice with Cre-dependent overexpression of lamin A in hematopoietic cells. A, Representation of the genetic construct inserted in the mouse Rosa26 locus before and after Cre-dependent removal of the LoxP-flanked stop sequence. B, Relative Lmna transcript expression in circulating leukocytes, normalized to the average expression of 2 housekeeping genes (Rplp0 and Actb; N=4 Lmnatg; n=8 Lmna-OE; each dot represents a pool of 2 or 3 animals, with approximately equal numbers of males and females). Statistical significance was assessed by the 2-tailed unpaired t test. C, Lamin A protein expression in circulating leukocytes assessed by flow cytometry (n=3 male and 2 female mice per genotype). Statistical significance was determined by the multiple t test with the Holm-Sidak method, with α=0.05. Each cell population was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD. D, Lamin A protein expression in the Lin− Sca1− cKit+ (LK) and Lin− Sca1+ cKit+ (LSK) bone marrow progenitor populations, assessed by flow cytometry and presented as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI); n=3 male and 2 female mice per genotype. Statistical significance was determined by the 2-tailed unpaired t test. E, Immunoblot analysis of lamin A/C in circulating leukocytes from mice of the indicated genotype. Endogenous lamin A runs at the expected 72 KDa in all mice, while Lmna-OE mice overexpress a larger lamin A isoform (lamin A+51aa). The graphs show the quantification of lamin A and lamin A+A+51aa, normalized to GAPDH as loading control. Statistical significance was determined using a 2-tailed unpaired t test comparing Lmnatg and Lmna-OE. F, Representative immunofluorescence images of peripheral blood leukocytes from Lmnatg and Lmna-OE mice showing the perinuclear staining characteristic of lamin A and increased lamin A protein expression in Lmna-OE mice. MERGE refers to the composite image generated by overlapping the DAPI and the Lamin A/C signals, allowing their visualization within the same field of view. cKit indicates cellular Kit proto-oncogene; Cre, causes recombination; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; Lin, lineage; LoxP, Locus of X (cross)-over in P1; Sca1, stem cell antigen; and WT, wild type.

To achieve lamin A overexpression specifically in hematopoietic cells and their progenitors, we crossed Lmnatg mice with Vav-iCre+ mice22 to generate heterozygous Lmnatg Vav Cre+ mice (from here on Lmna-OE). Lmna-OE mice were fertile and viable, exhibited physiological parameters comparable to those of WT animals, and displayed no overt phenotypic abnormalities (Figure S5A through S5E). To assess the overexpression efficiency, we first assessed lamin A expression in blood and BM progenitor populations. In peripheral blood leukocytes, RT-qPCR amplification (Figure 3B) and flow cytometry (Figure 3C) confirmed efficient lamin A overexpression in Lmna-OE mice versus Lmnatg mice (Cre– controls, which expressed only endogenous lamin A). Because carriage of just a single copy of the Lmna transgene resulted in an almost 8-fold increase in transcript expression, all subsequent experiments were conducted with heterozygous mice.

Flow cytometry analysis of BM progenitors from Lmna-OE mice revealed lamin A overexpression in Lin− (lineage) Sca1+ (stem cell antigen-1) cKit+ (cellular kit proto-oncogene) and Lin− Sca1− cKit+ stem and progenitor cell populations compared with Lmnatg controls (Figure 3D). However, mice of both genotypes had similar absolute cell counts in peripheral blood (Figure S5F) and BM populations (Figure S5G), without between-sex differences. Immunoblotting analysis of peripheral blood after erythrocyte lysis detected the expected bands corresponding to endogenous lamin A and lamin C (Figure 3E). In addition, Lmna-OE samples had a band of slightly lower electrophoretic mobility that was absent in samples from control WT and Lmnatg mice, thus indicating Cre-dependent expression of a higher molecular weight lamin A variant in Lmna-OE mice. Further analysis of the inserted transgene sequence revealed a cryptic ATG (adenine-thymine-guanine) within the LoxP sequence, which created a new translation start site and, consequently, a new open reading frame (aberrant ATG: extended open reading frame; Figure S6A). This open reading frame is in the same reading frame as endogenous lamin A, resulting in the addition of 51 extra amino acids (aas) at the N terminus, without altering the rest of the lamin A protein sequence. Targeted proteomic analysis of this additional band confirmed the presence of peptides containing the predicted extra 51 aas (Figure S6B). These findings, together with western blot quantification, indicate that Lmna-OE mice overexpress both normal lamin A and a modified variant, which we call lamin A+51aa (Figure 3E).

We next performed in silico modeling to compare the predicted 3-dimensional structure of mouse lamin A and lamin A+51aa proteins (see details in the Supplemental Methods). The predicted monomers were indistinguishable in the coiled-coil central domain, with differences mainly observed in the N- and C-terminal regions, an expected result, as these regions are highly disordered and lack a well-defined tertiary structure. Importantly, from an energy/stability perspective, both predicted monomers are stable, with nearly identical, highly negative energy values (Figure S6C). In silico modeling also predicted the potential for heterodimer formation without major structural alterations (Figure S6D). Moreover, immunostaining of peripheral blood leukocytes showed the expected perinuclear localization of the overexpressed lamin A (Figure 3F), with no abnormalities observed in Lmna-OE animals. Overall, these results suggest that the transgenic lamin A+51aa protein maintains key structural features required for its function. On this basis, we proceeded with subsequent experiments using the Lmna-OE model. It is also notable that N-terminally tagged recombinant lamin A proteins, such as GFP (green fluorescent protein)-Lamin A/C, are functional.34–37 Thus, although Lmna-OE mice overexpress a slightly modified form of lamin A, for the purpose of this study, we refer generally to lamin A overexpression.

To analyze atherosclerosis development in the context of lamin A overexpression in the hematopoietic cell compartment, we used a similar BMT strategy to that used in the loss-of-function experiments, this time transplanting Lmna-OE or Lmnatg CD45.2+ BM cells into atheroprone Ldlr−/− CD45.1+ recipient mice (Figure 4A). Flow cytometry analysis confirmed efficient lamin A overexpression in various WBC populations in mice reconstituted with Lmna-OE BM versus Lmnatg controls (Figure 4B). This analysis also revealed high and similar transplant efficiency in both groups (Figure 4C), thus indicating that lamin A overexpression in BM cells does not impair their engraftment or BM reconstitution. Furthermore, the 2 mouse groups had similar weight gain after 6 weeks of HFD (Figure 4D), indistinguishable absolute blood cell counts (Figure 4E), and comparable levels of post-HFD hypercholesterolemia (Figure 4F), demonstrating that hematopoietic lamin A overexpression does not impact major physiological parameters in reconstituted Ldlr−/− mice. Oil Red O staining confirmed a significantly lower atherosclerosis burden in the aorta (Figure 4G) and carotid arteries (Figure 4H) of mice reconstituted with Lmna-OE BM, indicating that lamin A overexpression in hematopoietic cells protects against atherosclerosis development.

Figure 4.

Lamin A overexpression in hematopoietic cells reduces atherosclerosis development in atheroprone Ldlr−/− mice. A, Protocol for atherosclerosis studies. B, Lamin A protein expression in CD45.2+ cells assessed by flow cytometry (Lmnatg mice: n=8 females and n=7 males; Lmna-OE mice: n=7 females and n=8 males). Statistical significance was determined by the multiple t test with the Holm-Sidak method, with α=0.05. Each population was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD. C, Transplant efficiency shown as the percentage of CD45.2+ circulating leukocytes 4 weeks after bone marrow transplantation (BMT), evaluated by flow cytometry (Lmnatg mice: n=8 females and n=7 males; Lmna-OE mice: n=7 females and n=8 males). Statistical significance was determined using a Mann-Whitney U test. D, Body weight evolution over the 6-week fat-feeding period (Lmnatg mice: n=8 females and n=7 males; Lmna-OE mice: n=7 females and n=8 males). Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA. E, Absolute cell counts in peripheral blood of reconstituted animals after 6 weeks of fat feeding (Lmnatg mice: n=8 females and n=7 males; Lmna-OE mice: n=7 females and n=8 males). Statistical significance was determined by the multiple t test with the Holm-Sidak method, with α=0.05. Each cell population was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD. F, Fasting plasma lipid concentration after 6 weeks of fat feeding (Lmnatg mice: n=8 females and n=7 males; Lmna-OE mice: n=7 females and n=8 males). Statistical significance was determined by the multiple t test with the Holm-Sidak method, with α=0.05. Each cell population was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD. G, Representative images of Oil Red O–stained aortas and quantification of plaque burden in the aortic arch (Lmnatg mice: n=15; Lmna-OE mice: n=14). Statistical differences were assessed by the 2-tailed unpaired t test. H, Representative images of Oil Red O–stained right carotid arteries and quantification of plaque burden (n=5 for Lmnatg and n=5 for Lmna-OE). Statistical differences were assessed by the 2-tailed unpaired t test. BM indicates bone marrow; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HFD, high-fat diet; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; TG, triglyceride; and WBC, white blood cell.

Lamin A/C Deficiency and Lamin A Overexpression in Hematopoietic Cells Induce Transcriptomic Changes in Immune and Endothelial Cells in Atherosclerotic Mouse Aortas

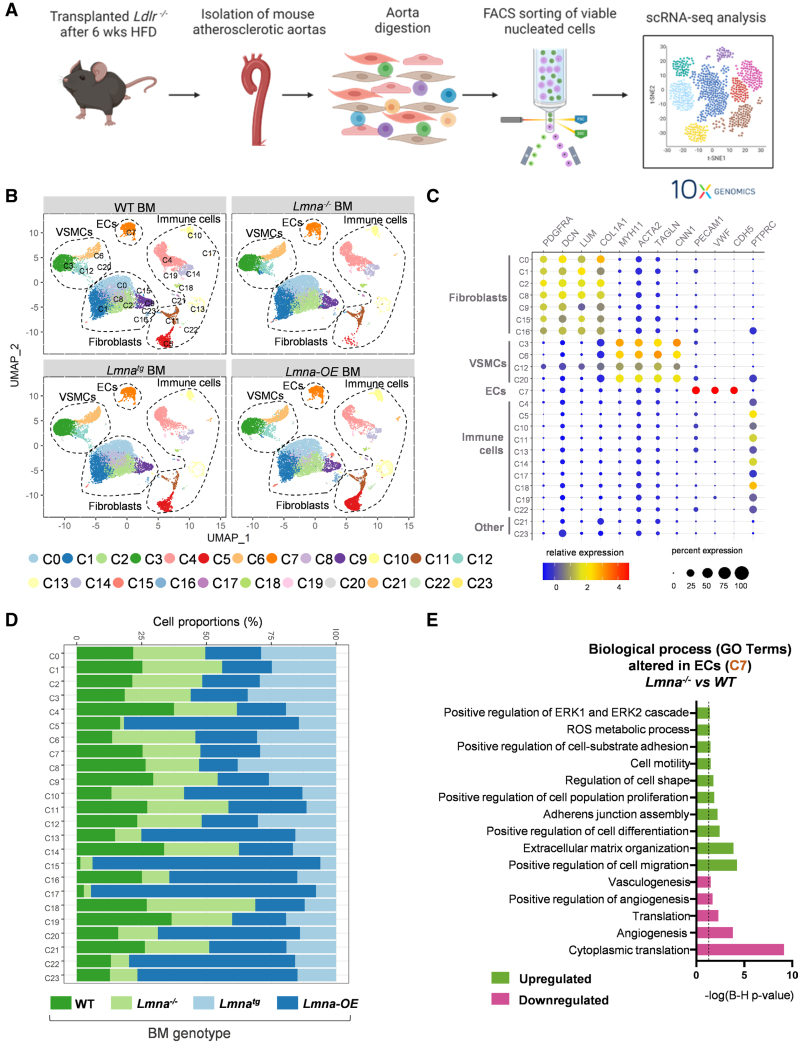

To investigate the mechanisms by which lamin A/C loss-of-function and gain-of-function modulate atherosclerosis, we performed scRNA-seq on aortas from Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with Lmna−/− or Lmna-OE BM or their respective controls (WT and Lmnatg BM, respectively) and fed the HFD for 6 weeks. Aortic tissue was enzymatically digested, viable nucleated cells (TO-PRO-3− and Hoechst 33342+) were isolated by cell sorting,38 and aortic cell suspensions were sequenced with the Chromium 10× Genomics platform (Figure 5A). A total of 49 727 cells were analyzed after the removal of low-quality cells and predicted doublets (≈6000 cells per sample), and a median of 2457 genes were detected per cell. Unsupervised clustering based on gene expression identified 24 cell clusters (C0–C23), which were visualized by dimensionality reduction with Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (Figure 5B). Cell identities for these clusters were determined according to the expression of well-established cell-specific markers, with fibroblasts being the most abundant population (47.91%), followed by immune cells (28.07%), vascular smooth muscle cells (18.75%), and endothelial cells (ECs; 4.99%). We also detected 2 small clusters (0.28%), possibly corresponding to an intermediate, poorly defined population (C21 and C23; Figure 5C). Overall, the relative abundance of the main cell types identified by scRNA-seq was similar across the 4 genotypes, with the exception of a few immune cell clusters (C5, C10, C13, C17, and C22) and some minor nonimmune cell clusters (C15, C20, and C23) that were more abundant in animals overexpressing lamin A in the hematopoietic cell compartment (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of the aorta in Ldlr−/− transplant recipients. A, Experimental approach. Lethally irradiated Ldlr−/− mice were reconstituted with bone marrow (BM) from Lmna+/+, Lmna−/−, Lmnatg, or Lmna-OE mice, and aortas were collected at the end of the 6-week period of fat feeding. B, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) representation of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, showing cell clusters and identified cell types. C, Relative expression and percentage expression of cell type–specific markers in each cluster. D, Relative abundance of each cluster in Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with lamin A–deficient, lamin A–overexpressing, and control BM. E, Biological processes altered within the endothelial cell (EC) cluster (C7) in mice reconstituted with Lmna−/− versus wild-type (WT) BM. The dashed black line indicates the Benjamini-Hochberg significance threshold (P=0.05). Statistical significance was assessed with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. FACS indicates fluorescence-activated cell sorting; GO, gene ontology; HFD, high-fat diet; and VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Bioinformatics analysis of the fibroblast and vascular smooth muscle cell clusters revealed no differences in proportions or transcriptional profiles among the 4 genotypes (Figure S7; Table S2 and S3). In contrast, there were major transcriptomic differences in ECs, which are critical in the early stages of atherosclerosis and its progression. We analyzed an average of 620 cells identified by EC markers (CD31+), all clustering in C7. Cell numbers in the EC cluster were similar in the 4 conditions analyzed (Figure S7D). ECs from recipients of Lmna−/− BM showed significant enrichment in gene ontology categories related to ECM (extracellular matrix) organization and regulation of cell migration. This was evidenced by increased expression of ECM components, such as collagens (Col1a1 and Col3a1), Fn1, ECM-remodeling enzymes such as MMP-3 (matrix metalloproteinase-3; Mmp3), and the actin cytoskeleton components Abi3bp and Tpm1 (Figure 5E; Table S4). These ECs also showed upregulation of constituents of the extracellular signal–regulated kinase signaling pathway, which is activated in proliferating and migrating ECs.39 In contrast, pathways associated with angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, and cytoplasmic translation were downregulated, suggesting compromised vascular repair mechanisms. These changes are consistent with increased EC activation and altered vascular integrity in Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with Lmna−/− BM and correlate with the higher aortic atherosclerosis burden in these mice.

Aortic immune cells accounted for between 17% and 40.9% of the total cells analyzed in the 4 experimental groups (Table S5). As expected, immune cells were directly affected at the transcriptional level by lamin A/C gain-of-function and loss-of-function in our BMT strategy, making them particularly relevant for understanding how lamin A/C modulates atherogenesis. To better characterize immune cell-specific alterations, we performed a reclustering of the CD45+ cell populations (Figure 6A). Among the immune clusters (ICs) identified, 4 were categorized as macrophages (IC1–IC4), characterized by the expression of Adgre1, Csf1r, Fcgr1, and Cd68. IC5 exhibited a gene signature consistent with inflammatory monocytes, marked by the expression of CD300E, Ccl22, and Ccr2, while IC6 was identified as neutrophils, with high expression of Ly6g, S100a9, and S100a8 (Figure S8A). Nonmyeloid cell populations identified in the aorta included B cells (IC7), enriched for Cd79a, Cd79b, Ly6d, and Mzb1; 6 T-cell clusters (IC8–IC12), expressing Cd3g, Cd4, and Cd8a; and a natural killer T-cell cluster (IC13), defined by Klra8, Klrc1, Gzmb, and Cd3g (Figure S8B). Finally, we identified 4 minor clusters, including a proliferative population (IC14), and clusters expressing markers of vascular smooth muscle cells (IC15), fibroblasts (IC16), and stromal cells (IC17), suggesting intermediate phenotypes. The relative abundance of these populations was similar to that reported in a previous scRNA-seq study of atherosclerotic mouse aortas,40 with macrophages being the major immune cell population, accounting for >40% of immune cells in aortas from mice reconstituted with WT, Lmna−/−, or Lmnatg BM (Figure 6B; Table S5).

Figure 6.

Characterization of immune cell reclustering in the atherosclerotic aorta of Ldlr−/− mice with lamin A/C deficiency or lamin A overexpression in hematopoietic cells. A, Uniform manifold approximation and projection representation of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) immune cell reclustering (CD45+), showing cell clusters and identified cell types in Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with bone marrow of the indicated genotype and fed the high-fat diet for 6 weeks. B, Bar plots representing the proportions of each immune cell type in each condition (in percentages). Colors for each cluster are defined as in A. C, Violin plots showing gene signature scores for neutrophil activation, NETosis, and apoptosis in the neutrophil cluster (IC6). The black horizontal line marks the mean score for each BM genotype. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test or with Kruskal-Wallis with Bonferroni correction. D, Biological processes altered in aortic macrophage clusters IC3 (left) and IC4 (right) in Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with Lmna−/− BM and fed the high-fat diet for 6 weeks versus wild-type (WT) control bone marrow. Statistical significance was determined by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Discontinuous black lines indicate Benjamini-Hochberg P=0.05. BM indicates bone marrow; GO, gene ontology; and IC, immune cluster.

Interestingly, mice reconstituted with Lmna-OE BM showed a marked reduction in the myeloid populations accompanied by an overall increase in lymphoid clusters, particularly T cells. IC11 was the predominant IC in the aortas of animals with hematopoietic lamin A overexpression, which corresponded to a unique T-cell cluster characterized by the expression of Rag1 along with other T-cell development regulators, supporting the hypothesis that these cells represent an immature, thymocyte-like T-cell population (Figure 6B; Figure S8B). T-cell clusters IC8, IC9, and IC10 were also enriched and represented distinct proliferative T-cell subsets with specialized functional roles, including cytotoxic activity, memory formation, and proinflammatory responses. In contrast, IC12, along with the natural killer T-cell cluster IC13, was the only T-cell populations that were more abundant in the context of lamin A/C deficiency. IC12 was identified as an Foxp3+ population with an inflammatory gene signature, consistent with an intermediate state between regulatory T cells and Th17-like cells. Therefore, we defined IC12 as dysfunctional regulatory T cells. Continuing the characterization of lymphoid clusters, our scRNA-seq analysis revealed an enrichment of the B-cell cluster IC7 under both lamin A/C deficiency and lamin A overexpression conditions compared with their respective controls (Figure 6B; Table S5). Given that B cells are among the immune cells that exhibit the most significant lamin A/C downregulation upon human aging (Figure 1), we further investigated differential gene expression profiles in B cells lacking lamin A/C versus those overexpressing lamin A. Lamin A/C deficiency induced a proinflammatory phenotype in B cells, characterized by upregulation of Cr2, Fcrl1, and Ighd, suggesting a shift toward activated or mature B-cell states with enhanced antigen presentation and T-cell activation potential. Conversely, B cells overexpressing lamin A exhibited upregulation of anti-inflammatory genes (eg, Il6st, Il5ra, Vsir) and regulatory markers (Cxcr5, Itga4, and Klf2/Klf4), likely contributing to disease resolution rather than plaque progression. Overall, these findings align with the accelerated atherosclerosis observed under hematopoietic cell lamin A/C deficiency, which is characterized by the enrichment of inflammatory B cells, cytotoxic natural killer T cells, and dysfunctional regulatory T cells, all contributing to a sustained inflammatory response. In contrast, lamin A overexpression was associated with an increased presence of immature T cells and a reduction in proinflammatory B cells, consistent with the decreased lesion size observed in these animals.

The immune cell reclustering analysis suggests that lymphoid cells may not be the primary drivers of the atherosclerosis phenotype observed but rather contribute to the maintenance of a chronic inflammatory state in the aortas of animals reconstituted with lamin A/C–deficient BM cells. To specifically assess the myeloid cell-driven contribution to atherogenesis in the absence of lamin A/C, we performed a BMT experiment using donor BM from Lmnaflox/flox Vav Cre+ Rag1−/− mice, lacking lamin A/C in hematopoietic cells and deficient in B and T cells, and Cre- controls (Figure S9A). Hematologic analysis confirmed the complete absence of B cells and a profound reduction in T cells in reconstituted Ldlr−/− recipients. The residual T cells detected in transplanted animals likely represent radioresistant cells that survived the preconditioning ionizing radiation and, therefore, express normal levels of lamin A/C (Figure S9B). Interestingly, this model recapitulated the increased lesion size observed in the broader hematopoietic-deficient setting (Figure S9C), indicating that lamin A/C loss in myeloid cells alone is sufficient to drive disease progression. However, complete lamin A/C deficiency across all hematopoietic cells resulted in a more pronounced increase in atherosclerotic burden compared with the myeloid-restricted model, suggesting that B cells and specific T-cell subsets may play a secondary, yet significant, role in modulating disease progression.

Having established the impact of lamin A/C modulation on lymphoid cells, we next focused on myeloid populations, as they emerged as key drivers of atherogenesis in our model. Notably, monocytes and neutrophils were enriched in the aortas of mice lacking lamin A/C in hematopoietic cells, representing 7.39% and 3.25% of total immune cells, respectively. In contrast, their abundance was markedly reduced upon lamin A overexpression, comprising only 2.25 and 0.59% of total cells, respectively (Figure 6B; Table S5). This finding is particularly relevant in the case of neutrophils, which are among the cell types exhibiting the most pronounced lamin A/C downregulation during human aging (Figure 1). Gene signature analysis of neutrophils, based on literature-defined pathways, revealed that lamin A/C deficiency promotes neutrophil activation, apoptosis, and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, 3 processes strongly implicated in atherosclerosis progression (Figure 6C). Building on these findings, we further explored the heterogeneity within the macrophage compartment by characterizing the 4 distinct macrophage clusters identified. IC1 exhibited a gene expression profile consistent with cavity macrophages; IC2 represented a population of resident macrophages; IC3 was identified as the predominant monocyte-derived macrophage population; and IC4 corresponded to a cluster of Trem2+ foamy macrophages (Figure S8A). Macrophages and foam cells were the predominant immune cell populations in mice with hematopoietic lamin A/C deficiency and were drastically reduced upon lamin A overexpression. This pattern aligns with the contrasting atherosclerosis burden observed under these conditions: increased in the absence of lamin A/C in hematopoietic cells and reduced with its overexpression. These findings prompted a deeper investigation into the transcriptional changes within macrophage clusters to better understand their role in atherogenesis. Bioinformatic analysis of the 117 differentially expressed genes identified in the major monocyte-derived macrophage cluster IC3 revealed significant upregulation of gene ontology terms related to leukocyte migration, stress response, and inflammatory pathways in macrophages from mice reconstituted with Lmna−/− BM (Figure 6D, left; Table S6). This included genes related to complement activation, such as complement receptor 3 (Itgam) and complement protein C3, the Ptger4, the cell-motility-related gene Rac2, and several chemokines, chemokine receptors, and adhesion molecules, such as CXCL13 (chemokine [C-X-C motif] ligand 13; Cxcl13), and Fpr2, which has been linked to macrophage recruitment to lesions and the regulation of inflammation. Regarding IC4, only 36 genes were differentially expressed in mice with lamin A/C–deficient BM, all of them suggesting an overall increase in chemotaxis and regulation of immune response gene ontology terms (Figure 6D, right; Table S7). Notably, downregulated gene ontology terms in aortic macrophages from mice reconstituted with Lmna−/− BM included major histocompatibility complex genes (Cd74, H2-Eb1, Igkc, H2-Dma, H2-Dmb1, H2-Aa, and H2-Ab1) and ribosomal proteins, suggesting reduced activation of the adaptive immune response and translation categories (Figure 6D).

Lamin A/C Expression in Hematopoietic Cells Modulates Leukocyte Migration During Atherosclerosis Development in Mice

Analysis of our scRNA-seq identified distinct biological processes potentially underlying the role of lamin A/C in atherogenesis; however, these transcriptomic changes require further validation. Overall, immune cell populations exhibited a proinflammatory profile in the absence of lamin A/C. Given that macrophages are central players in plaque development and serve as a major source of proinflammatory mediators within atherosclerotic plaques, we first investigated whether lamin A/C deficiency and lamin A overexpression affect cytokine production in vitro using BM-derived macrophages activated through lipopolysaccharide and IFNγ (interferon gamma) stimulation. Analysis at different times poststimulation showed no significant differences in cytokine production under either lamin A/C deficiency (Figure S9D) or overexpression (Figure S9E). These findings suggest that altered cytokine production is unlikely to be the primary mechanism driving atherosclerosis in the context of lamin A/C dysregulation.

The early stages of atherosclerosis are characterized by the recruitment of circulating leukocytes to the arterial wall and their migration across ECs,2,41 and lamin A/C has been proposed as an important regulator of cell migration in in vitro settings.42–44 Our mouse studies reveal an important role for hematopoietic cell lamin A in early atherogenesis, and the scRNA-seq analysis identifies leukocyte migration as one of the biological processes modulated by changes in lamin A/C expression in these cells. We, therefore, investigated the impact of lamin A/C deficiency and overexpression on leukocyte migration in vivo. Reconstituted Ldlr−/− mice were euthanized after 2 weeks of the HFD to allow analysis of early atherosclerotic lesions. En face immunofluorescence of the aortic arch detected significantly elevated numbers of CD45+ERG− leukocytes in the intimal layer in mice with hematopoietic lamin A deficiency, whereas hematopoietic lamin A overexpression resulted in reduced numbers of recruited leukocytes in the aorta (Figure 7A). These changes in aortic leukocyte accumulation were observed despite no between-genotype differences in total circulating leukocytes (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Changes in hematopoietic lamin A/C expression modulate the leukocyte immune response and extravasation capacity in vivo. Ldlr−/− mice were reconstituted with bone marrow (BM) of the indicated genotype and were fed the high-fat diet for 2 (A and B) or 12 weeks (C). A, Representative en face immunofluorescence staining of endothelial cells (CD31+; green) and leukocytes (CD45.2+; red) in the aortic arch and quantification of CD45+ leukocytes per area (wild-type [WT] and Lmna−/− mice: n=9; Lmnatg and Lmna-OE mice: n=10; with ≈50% males and females in all experimental conditions). The mean value for each mouse was determined by averaging the number of cells present in 3 microscopic fields. Scale bar, 100 µm. B, Absolute white blood cell (WBC) counts at the end of the 2-week fat-feeding period (WT and Lmna−/− mice: n=9; Lmnatg and Lmna-OE mice: n=10; with ≈50% males and females in all experimental conditions). Scale bar, 100 µm. C, Representative intravital microscopy images and quantification of leukocyte extravasation into the cremaster muscle. Each value represents a different venule analyzed from transplanted Ldlr−/− mice (n=23 WT; n=47 Lmna−/−; n=24 Lmnatg; and n=20 Lmna-OE). Statistical significance in A through C was assessed by the 2-tailed unpaired t test. Scale bar, 50 µm. D, Proposed mechanism for lamin A/C–dependent regulation of atherogenesis during aging. Age-related downregulation of lamin A/C levels in circulating leukocytes facilitates their extravasation into the arterial wall, thereby contributing to increased inflammation and the progression of atherosclerosis.

Leukocyte recruitment from the bloodstream to solid tissues involves sequential steps of rolling, adhesion, and extravasation (diapedesis). To determine which of these steps are modulated by lamin A/C expression in vivo, we studied leukocyte recruitment in reconstituted Ldlr−/− mice by intravital microscopy of the small vessels of the cremaster muscle, a tissue that is easily accessible, thin, and transparent, thus facilitating image acquisition. Rolling flux and adhesion of monocytes and neutrophils in the cremaster venules were similar in the experimental groups and their controls, except for significant increases in monocyte rolling flux and the number of adhered neutrophils in Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with Lmna−/− BM (Figure S10A). However, modulation of lamin A/C expression significantly altered the number of extravasated leukocytes in the cremaster muscle, with numbers higher in mice with hematopoietic lamin A/C deficiency and lower in mice with hematopoietic lamin A overexpression (Figure 7C).

To determine whether the enhanced extravasation observed in vivo in lamin A/C–deficient leukocytes is driven by intrinsic cues (eg, reduced nuclear stiffness due to lamin A/C deficiency, as suggested by previous studies)43–45 or by increased vascular inflammation, we performed in vitro leukocyte migration experiments using culture chambers with narrow channels and constrictions, where migration primarily depends on leukocyte intrinsic properties under carefully controlled conditions. We specifically selected proinflammatory monocytes (Ly6Chi [lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C–high expression]), as they play a pivotal role in the early stages of atherosclerosis.46 Our results show that monocytes lacking lamin A/C spent less time within constrictions, suggesting that they migrate more efficiently than controls (Figure S10B). These in vitro findings indicate that the enhanced migratory capacity observed in vivo is most likely driven by intrinsic alterations in monocyte biomechanics, especially reduced nuclear deformability.

Discussion

Several studies have demonstrated that lamin A/C expression decreases with aging in various cell types and species.31,32,47–49 Consistent with those findings, here, we detected an age-related reduction in lamin A/C expression in human WBCs. In line with our results, lamin A/C deficiency in mice is associated with an aging-like hematopoietic phenotype.20 Previous studies also identified correlations between mutated lamin variants and atherosclerosis, suggesting that lamin proteins play a role in the development of atherosclerosis during both normal aging and premature aging.10,38,50–53 Our study extends those findings through an investigation in genetically modified mice of the effects of hematopoietic cell lamin A/C deficiency and lamin A overexpression on the development of atherosclerosis, a highly prevalent disease primarily driven by aging, the most important cardiovascular risk factor.3,6,7,54 Previous studies have shown that global Lmna deletion in homozygous Lmna−/− mice leads to cardiac abnormalities and premature death by 4 to 5 weeks of age,21,55,56 a phenotype also observed in mice with cardiomyocyte-specific Lmna ablation.57,58 In this study, we restricted Lmna deficiency to the hematopoietic compartment via BMT into lethally irradiated Ldlr−/− recipient mice. This approach circumvents the lethality associated with global Lmna loss, likely driven by cardiomyocyte dysfunction, and enables the specific investigation of the hematopoietic role of lamin A/C in atherogenesis. Indeed, Ldlr−/− mice with lamin A/C deficiency in hematopoietic cells showed no signs of systemic illness or increased mortality throughout the study. Instead, these mice exhibited a significant increase in atherosclerotic plaque burden, whereas overexpression of lamin A in hematopoietic cells mitigated atherogenesis. Our findings suggest that lamin A-dependent modulation of HFD-induced atherosclerosis is mediated by changes in the extravasation capability of leukocytes, driven by alterations in nuclear deformability, along with regulation of their proinflammatory profile. Increased EC activation, as identified by scRNA-seq, may also contribute to enhanced leukocyte extravasation following lamin A/C suppression in hematopoietic cells.

Several genetically modified mouse models of lamin A/C deficiency have been generated to assess the role of lamin A/C in various pathophysiological processes.59 However, earlier gain-of-function experiments were performed exclusively in vitro, as no gain-of-function mouse models were available. In this study, we generated the Lmnatg mouse model, the first to enable gain-of-function studies of lamin A, providing a valuable tool for investigating the dosage-dependent effects of lamin A on aging and related conditions, as well as laminopathies. In addition, Cre-dependent expression allows time- and tissue-specific lamin A overexpression, offering deeper insights into finely regulated lamin A expression throughout development.12 Upon Cre recombinase–dependent expression, Lmnatg mice exhibit overexpression of both normal lamin A and a modified form, lamin A+51aa, resulting from the presence of an alternative ATG codon. Lamin A+51aa had the normal lamin A perinuclear location, suggesting that the additional 51 aa at its N-terminal region did not interfere with its integration into the nuclear lamina. Moreover, in silico modeling of the 3-dimensional protein structure predicted that lamin A+51aa is stable, with similar negative energy values compared with the normal lamin A isoform, and has the potential for heterodimer formation without major structural alterations. It is also notable that N-terminally tagged recombinant lamin A proteins, such as GFP-Lamin A/C, are functional.34–37 Importantly, in our analysis, Lmna-OE mice, with lamin A overexpression restricted to the hematopoietic cell compartment, showed no hematologic or phenotypic abnormalities, and BM from these animals supported normal BM reconstitution when transplanted into Ldlr−/− mice in BMT studies. Together, our findings suggest that lamin A+51aa retains essential structural features necessary for its functional activity.

Our scRNA-seq data revealed no major changes in aortic fibroblasts or vascular smooth muscle cells, which are major components of the arterial wall. In contrast, ECs from mice with hematopoietic lamin A/C deficiency exhibited changes consistent with an enhanced activation state, correlating with the elevated atherosclerosis burden in these mice. As expected, manipulation of lamin A/C in the hematopoietic compartment was associated with profound transcriptomic alterations in immune cells. The altered expression of chemotaxis-related genes observed in macrophages of Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with Lmna−/− BM suggests a mechanistic link between hematopoietic lamin A and atherosclerosis, wherein reduced lamin A/C expression increases leukocyte recruitment to the arterial wall, promoting inflammation and plaque formation.

In line with these transcriptional changes, ex vivo confocal immunofluorescence analysis revealed an increased number of recruited leukocytes in the aorta of Ldlr−/− mice with hematopoietic lamin A/C deficiency, whereas hematopoietic lamin A overexpression reduced aortic leukocyte content. Corroborating these observations, intravital microscopy revealed enhanced leukocyte extravasation in mice with hematopoietic lamin A/C deficiency and reduced extravasation in those with hematopoietic lamin A overexpression. Although monocyte rolling flux and neutrophil adhesion were increased in response to hematopoietic lamin A/C deficiency, we observed no changes in monocytes and neutrophils overexpressing lamin A, suggesting that the observed effects on leukocyte recruitment are mediated mainly by changes in leukocyte extravasation capacity. This is supported by previous in vitro studies showing that lamin A/C modulates the migration of leukocytes through small artificial pores, with lamin A/C deficiency increasing cell migration43 and overexpression reducing it.44 Lamin A/C–deficient cells exhibit ≈50% softer nuclei, which increases nuclear deformability and enables more rapid migration through small constrictions.42,60–62 Extrapolating these in vitro results to the vascular wall, we propose that EC junctions act in the same way, functioning as small pores that leukocytes can pass through in response to proatherogenic stimuli. Our results highlight, for the first time, the critical role of hematopoietic lamin A in regulating in vivo leukocyte extravasation and atherogenesis, with elevated lamin A expression reducing leukocyte extravasation, inflammation, and atherosclerosis and low lamin A/C levels promoting these processes (Figure 7D).

Our single-cell transcriptomic data reveal an enrichment of lamin A/C–deficient monocytes and neutrophils in atherosclerotic aortas. This finding supports the notion that lamin A/C deficiency enhances the migratory capacity of monocytes and neutrophils, facilitating their recruitment and extravasation into the arterial wall, thereby promoting atherosclerosis. Furthermore, our results show that aortic neutrophils lacking lamin A/C exhibit increased activation, a higher propensity for apoptosis and elevated NET formation, all of which may contribute to atherosclerosis progression. However, the upregulation of activation and NET-associated gene signatures in lamin A/C–deficient neutrophils could also reflect their accumulation in more advanced lesions, rather than being a direct consequence of lamin A/C loss. Supporting our findings, previous studies have shown that lamin B overexpression can attenuate NET formation, whereas reduced lamin B levels enhance NETosis.63 Overall, our data suggest that the accelerated atherosclerosis observed under lamin A/C deficiency results from a cooperative effect among multiple immune cell types present in the aorta. Monocyte-derived macrophages seem to be the primary contributors, promoting leukocyte recruitment and enhancing local inflammation. Neutrophils may also contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation by further amplifying the inflammatory response, as supported by our in vivo findings using a myeloid cell-specific lamin A/C deficiency model. In addition, in the absence of lamin A/C, T cells and B cells exhibit a more active and proinflammatory phenotype, potentially sustaining chronic inflammation and exacerbating plaque progression. Future studies employing cell type–specific models will be essential to confirm and further elucidate these mechanisms.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the age-dependent downregulation of lamin A/C observed in human WBCs is modest (≈20%). Although this reduction is seen across all cell populations analyzed, it reached statistical significance only in neutrophils and B cells. Variability among human samples limited our ability to perform finer age stratifications, which could have provided a more detailed and representative view of the age-related modulation of lamin A/C. In this context, further studies involving larger human cohorts and more granular age groupings will be valuable to confirm and refine these observations. Notably, a 50% reduction in hematopoietic lamin A/C levels in mice resulted in a 31% increase in atherosclerotic lesion size. While this increase did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07), it aligns with the 80% increase observed upon complete lamin A/C deletion, supporting a dose-dependent relationship between lamin A/C levels and atherosclerosis severity. Second, after only 6 weeks of HFD, atherosclerotic lesions in reconstituted Ldlr−/− mice will constitute only a small fraction of the whole arterial sample used for scRNA-seq analysis, potentially masking the detection of small populations and reducing the statistical power to identify differences in biological processes between conditions. Despite this, our work revealed a degree of cellular heterogeneity consistent with previous scRNA-seq studies in mouse atherosclerotic aortas,40,64–66 and immune cells constituted the second-most abundant population in our data set.

Overall, our findings suggest that the age-dependent downregulation of lamin A/C in hematopoietic cells promotes leukocyte extravasation through the vascular endothelium, thereby exacerbating inflammation and accelerating atherosclerosis progression (Figure 7D). Further research into the mechanisms driving this age-related decline in hematopoietic lamin A/C expression could reveal new therapeutic targets for delaying the development of atherosclerosis. Whether this downregulation is associated with other known age-related cardiovascular risk factors, such as clonal hematopoiesis, remains to be investigated. It would also be of interest to investigate whether lamin A overexpression can attenuate inflammation in other age-related inflammatory diseases and whether lamin C overexpression can reproduce the atheroprotective effects observed in our model.

Article Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Simon Bartlett for English editing, the Pluripotent Cell Technology and Transgenesis Units at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares Carlos III (CNIC) for the generation of Lmnatg mice, Verónica Labrador, Hélio Roque, and Elvira Arza from the CNIC Microscopy Unit for help with ImageJ macro development, Eva Santos and the CNIC Animal Facility for animal care, and Matthieu Piel for his assistance with the in vitro monocyte migration assays. Illustrations were created using BioRender.com (licensed to V. Andrés). Flow cytometry and cell sorting were conducted at the CNIC Flow Cytometry Unit. The authors thank the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) for accepting 2 different abstracts related to this article for oral presentation at the 85th and 90th EAS Congress (published as supplements in the journal Atherosclerosis, with DOIs: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.06.176 and 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.06.041).[

Sources of Funding

The laboratory of V. Andrés is supported by grant PID2022-141211OB-I00 funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities (MICIU)/Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI; MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and by the European Regional Development Fund/European Union (ERDF/EU) and by donations from the Asociación Progeria Alexandra Peraut and the Fundación Inocente. The work in the laboratory of J.J. Fuster is supported by grant PLEC2021-008194 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR (Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia); and grant PID2021-126580OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF/EU. The work in the laboratory of H. Bueno is supported by the European Union (grant EU4H-2022-JA-03), the Spanish Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII; Programa de Fortalecimiento Institucional [FORTALECE], PI21/01572), and the Sociedad Española de Cardiología. The laboratory of J.M. González-Granado is supported by grants PI20/00306 and PI24/00146 funded by the ISCIII and the European Union. C. Silvestre-Roig receives support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (CRC TRR332 project A1 and CRC1223 project A6) and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research (IZKF) of the University of Münster. M. Amorós-Pérez was supported by the Ministry of Education, Vocational Training and Sports (predoctoral contract FPU18/02913). The CNIC is supported by the ISCIII, the MICIU, and the Pro-CNIC Foundation and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (grant CEX2020-001041-S funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). The BD FACSymphony Cytometer was acquired with grant EQC2018-005009-P, and microscopy was conducted at the CNIC Microscopy and Dynamic Imaging ICTS (Infraestructura Científica y Técnica Singular)-ReDib (Red Distribuida de Imagen Biomédica), both funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF-a way to make Europe.

Disclosures

H. Bueno received consulting/speaking fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Organon, unrelated to the current study. The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or the reporting of the study. The other authors report no conflicts.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Methods

Tables S1–S8

Major Resources Table (Table S9)

Figures S1–S10

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- aa

- amino acid

- BM

- bone marrow

- BMT

- bone marrow transplantation

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- EC

- endothelial cell

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- IC

- immune cluster

- LDL

- low-density lipoprotein

- LINC

- linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton

- NET

- neutrophil extracellular trap

- OT

- off-target

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- RRID

- Research Resource Identifiers

- RT

- room temperature

- scRNA-seq

- single-cell RNA sequencing

- WBC

- white blood cell

M. Amorós-Pérez and A. Del Monte-Monge contributed equally.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 1633.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.322893.

References

- 1.Libby P. Fanning the flames: inflammation in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107:307–309. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048892.83521.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savji N, Rockman CB, Skolnick AH, Guo Y, Adelman MA, Riles T, Berger JS. Association between advanced age and vascular disease in different arterial territories: a population database of over 3.6 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1736–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JC, Bennett M. Aging and atherosclerosis: mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ Res. 2012;111:245–259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Is age really a non-modifiable cardiovascular risk factor? Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1307–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sniderman AD, Furberg CD. Age as a modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2008;371:1547–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60313-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendieta G, Pocock S, Mass V, Moreno A, Owen R, García-Lunar I, López-Melgar B, Fuster JJ, Andres V, Pérez-Herreras C, et al. Determinants of progression and regression of subclinical atherosclerosis over 6 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:2069–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamczyk MR, del Campo L, Andrés V. Aging in the cardiovascular system: lessons from Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Annu Rev Physiol. 2018;80:27–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021317-121454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorado B, Andrés V. A-type lamins and cardiovascular disease in premature aging syndromes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;46:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke B, Stewart CL. The nuclear lamins: flexibility in function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrés V, González JM. Role of A-type lamins in signaling, transcription, and chromatin organization. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:945–957. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broers JLV, Ramaekers FCS, Bonne G, Ben YR, Hutchison CJ. Nuclear lamins: laminopathies and their role in premature ageing. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:967–1008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verstraeten VRM, Broers JV, Ramaekers FS, van Steensel M. The nuclear envelope, a key structure in cellular integrity and gene expression. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1231–1248. doi: 10.2174/092986707780598032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yabuki M, Miyake T, Doi Y, Fujiwara T, Hamazaki K, Yoshioka T, Horton AA, Utsumi K. Role of nuclear lamins in nuclear segmentation of human neutrophils. Physiol Chem Phys Med NMR. 1999;31:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]