ABSTRACT

Using three‐wave data from 962 Chinese adolescents (45.1% boys, M age = 12.369, SD = 0.699 at T1, September 2022), this study examined the link between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' life meaning, with adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence tested as a mediator and filial piety tested as a moderator. Parental social comparison shaming (T1) was negatively associated with adolescents' presence of life meaning (T3, September 2023, controlling for baseline) through a negative association with adolescents' satisfaction of competence need (T2, March 2023, controlling for baseline). The link between social comparison shaming and satisfaction of competence need was more pronounced among adolescents with higher (versus lower) reciprocal filial piety. The identified indirect effect was also stronger among adolescents with higher (versus lower) reciprocal filial piety.

Keywords: basic need for competence, filial piety, life meaning, social comparison shaming

Since the seminal work by Barber (1996), parental psychological control has been extensively demonstrated to be a unique form of parental control that has negative implications for child development in various domains and across different cultures (for reviews, see Chyung et al. 2022; Yan et al. 2020). However, addressing the direct and generic associations of parental psychological control (as a broad construct) with child development is reaching a point of diminishing returns. Moving this field forward increasingly hinges on scientific endeavors in the following directions. First, as parental psychological control has long been conceptualized as multidimensional (Yu et al. 2015), greater nuance awaits to be revealed from a differentiated perspective at the dimension level (Cheah et al. 2019; Fang et al. 2022; Romm and Alvis 2022). Accordingly, researchers should pay greater attention to the developmental consequences of psychological control in its more specific forms.

Second, more mechanism‐oriented examinations are needed to elucidate through what processes (i.e., mediating mechanisms) and specify under what conditions (i.e., moderating mechanisms) parental psychological control would be particularly harmful for child development (Cheah et al. 2019; Lu et al. 2017; Soenens et al. 2015). Last, most of the extant research in this field has focused on child psychopathology outcomes, such as internalizing and externalizing problems (see Chyung et al. 2022; Yan et al. 2020). Little is known about the potential implications of parental psychological control for child development of adaptive strengths, which appears to be a key research lacuna given the increasing emphasis on human flourishing with the rise of positive psychology.

In response to such research needs, the present study sought to investigate the association between parental social comparison shaming (as one major yet still underexamined form of parental psychological control; Fang et al. 2022) and adolescents' life meaning (as a stage‐salient asset for positive youth development; Negru‐Subtirica et al. 2016). Further, to elucidate the implicated mechanisms, we also particularly tested the potential mediating role of adolescents' perceived satisfaction of basic psychological need for competence as well as the potential moderating roles of adolescents' endorsement of authoritarian and reciprocal filial piety.

1. Parental Social Comparison Shaming as a Unique Form of Parental Psychological Control

Social comparison shaming is a psychological control strategy that parents use to induce children's feelings of shame about their inferiority by unfavorably comparing the behaviors and performance of their children to those of others (e.g., peers, siblings). This practice aims to motivate children to take responsibility for their actions and strive for improvement (Camras et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2015). For example, some parents may remind their children that their classmates performed better in the school exams than they did to push their children to study harder and catch up. Notably, previous studies have yielded evidence supporting parental social comparison shaming as a separate, unique form of parental psychological control (Fang et al. 2022; Zhu et al. 2023) as well as an important manifestation of parental disrespect across various cultural contexts (Barber et al. 2012).

1.1. Implications for Child Development

Unsurprisingly, children and adolescents tend to consider parental social comparison shaming as a less appropriate and less helpful discipline strategy that reflects less parental love and concern (Smetana et al. 2021). Such shame‐based parenting practices appear to elicit children's fewer positive feelings and be perceived by children as psychologically harmful to their self‐worth and mental well‐being (Helwig et al. 2014; Midgley et al. 2023; Smetana et al. 2021). Furthermore, parental social comparison shaming has been negatively linked with adolescents' life satisfaction and academic functioning (Fang et al. 2022) as well as positively associated with adolescents' internalizing and externalizing problems (Chen et al. 2021; Jensen et al. 2015). Notably, the results of a very recent study (Zhang and Yan 2024) also indicated that parental unfavorable upward social comparison was negatively associated with children's mastery motivation through their impaired self‐concept.

1.2. Contextualization in Chinese Culture

Social comparison shaming appears to be a psychological control strategy that is more commonly adopted in Chinese (versus Western) parenting (Wang et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2002). The prevalence has its roots in Chinese Confucian traditions. Living in an East Asian culture that historically endorses interdependence, conformity, as well as self‐improvement (Heine et al. 2001; Ng et al. 2007), Chinese parents employ social comparison shaming as a moral discipline technique to achieve socialization goals, such as enhancing children's sensitivity to social norms, cultivating children's sense of responsibility for their actions, and promoting children's acquisition of self‐reflection abilities (Fung 1999, 2006; Fung and Chen 2001).

Within the Confucian traditions, “Knowing shame (知恥)” has been long held as a prominent moral virtue, and facilitating children's internalization of such values for the building of behavioral decency represents one of the central tasks for Chinese parenting (Fung 1999). In doing so, Chinese parents tend to feel highly obligated to “guan (管)” (i.e., to govern, to care for, and to love) their children across many life aspects, which is manifested in their “training (教訓)” of children through constantly monitoring and correcting children's misbehaviors to ensure their academic success, socio‐emotional adjustment, and being “fit in” with the society (Chao 1994; Cheung and Pomerantz 2011; Ng and Wang 2019). In the face of children's unsatisfactory performance, eliciting children's feelings of shame through “criticism, threats of abandonment, and negative social comparison” (Fung 1999, 521) is among the most common ways for Chinese parents to carry out their “training” practices.

In addition, as compared to Western parents, Chinese parents' feelings of self‐worth appear to be more contingent on children's performance (Ng et al. 2014), which may heighten their tendency to engage in social comparison shaming so as to motivate children to strive for self‐improvement. Relatedly, Chinese culture is a “face” (面子) culture (Hwang 2006; Kim et al. 2010), in which people's sense of worth is largely derived from others' respect, and people gain others' respect through their fulfillment of societal expectations. Accordingly, when children stand out in key life domains (e.g., academic excellence), Chinese parents will have face. In contrast, children's failures in such domains will make their parents lose face. To save face, Chinese parents are sensitive to children's unsatisfactory performance and place a greater emphasis on children's failures than on their successes (Ng et al. 2007; Pomerantz et al. 2020). When detecting children's unsatisfactory performance, Chinese parents likely engage in social comparison shaming to urge their children to devote more effort for improvement, underlying which might be the fear of losing face and loss of self‐worth (Ng et al. 2014) and the preference for achievement outcomes (Qu et al. 2016).

Unsurprisingly, social comparison shaming has long been viewed as a normative disciplinary practice that is in line with Chinese culture (Fung 2006). Yet, the results of some recent studies based on Chinese samples have challenged this notion. Parental social comparison shaming practices have been perceived by Chinese children and adolescents as psychologically harmful and inappropriate (Smetana et al. 2021). Such practices also have been negatively linked with Chinese young children's and adolescents' adaptation in various domains, including life satisfaction, academic achievement, social adjustment, as well as self‐concept (Chen et al. 2021; Fang et al. 2022; Zhang and Yan 2024).

Notably, although parental social comparison shaming has been linked to various child psychopathology outcomes, little is known about its potential implications for the development of child adaptive strengths. With the rise of positive and humanistic psychology, researchers increasingly acknowledge the importance of understanding what provides human beings with meaning in the lives that they lead, especially as they age into adolescence and young adulthood when people first begin to dedicate themselves to reflecting deeply on their life directions, missions, as well as existential values (Negru‐Subtirica et al. 2016; Russo‐Netzer and Tarrasch 2024; Steger et al. 2009). In response to this trend, in the present study, we aim to examine whether and how parental social comparison shaming may be related to adolescents' meaning in life.

2. Linking Parental Social Comparison Shaming With Adolescents' Meaning in Life

2.1. Meaning in Life: Presence Versus Search

Steger et al. (2006, 81) defined meaning in life as “the sense made of, and significance felt regarding, the nature of one's being and existence,” which is accompanied by “the degree to which they perceive themselves to have a purpose, mission, or over‐arching aim in life” (Steger 2009, 682). Furthermore, two sub‐dimensions for meaning in life have been proposed: presence of meaning and search for meaning. The former refers to the extent to which “people experience their lives as comprehensible and significant, and feel a sense of purpose or mission in their lives that transcends the mundane concerns of daily life.” The latter pertains to “the dynamic, active effort people expend trying to establish and/or augment their comprehension of the meaning, significance, and purpose of their lives” (Steger, Kashdan, et al. 2008, 661).

The importance of considering the two aspects of meaning in life in a single study as related but separate and distinct constructs has been highlighted in previous research (Chu and Fung 2021; Steger et al. 2006). The search for and the attainment of life meaning are somewhat independent from each other. People lacking life meaning tend to search for it, but the search for meaning does not necessarily lead to its presence (Steger, Kashdan, et al. 2008). Notably, the presence of life meaning has been consistently demonstrated to be a pivotal psychological asset that can facilitate adaptations and optimal functioning, prevent maladjustment, and play a protective role against adversities (e.g., Dulaney et al. 2018; Ho et al. 2010; Li et al. 2019). As such, feeling that one's life is meaningful is an essential component of human well‐being and a cornerstone resource for human flourishing, whereas lack of meaning in life likely leads to a painful existence, contributes to mental health issues, and compromises resilience in the face of life difficulties.

In contrast, the associations of the search for life meaning with well‐being indicators seem far less straightforward. Findings of prior research still remain highly mixed (see Li et al. 2021 for a review). People demonstrating high levels of search for life meaning could be those who are open‐minded, enthusiastically looking for new possibilities, and proactively seeking a deeper understanding of their life experiences. Alternatively, searching for life meaning also might be a coping response to difficult situations in which people's needs are frustrated, directions for actions are unclear, and life compasses are malfunctioning. The complexity inherent within the construct of the search for life's meaning and its antecedents and consequences still awaits being more systematically revealed. As Steger, Kawabata, et al. (2008) stated, “The search for meaning is related to negative perceptions of self and circumstances yet also marked by a thoughtful openness to ideas about life, suggesting that it might emerge in more or less healthy or unhealthy forms depending on who is searching. It also appears that people might be stimulated to search for meaning when their sense of life's meaningfulness erodes” (225).

2.2. Why Adolescents' Meaning in Life

Meaning in life has been considered an important psychological asset in the positive youth development framework. With the rapid gain in cognitive capacity and the increasingly complex social life, adolescents start to reflect on some “deeper” questions (e.g., Are my being and existence significant?), construct their identity, build their worldview, derive meaning from daily activities, and form their life goals (Chen et al. 2022; Russo‐Netzer and Shoshani 2020). As such, establishing a sense of life meaning is a primary facet of adolescents' well‐being, given that they are in a life period with age‐graded developmental tasks related to identity exploration (Negru‐Subtirica et al. 2016). Prior studies have yielded evidence supporting that the presence of life meaning was negatively associated with adolescents' health risk behaviors and psychological distress (Brassai et al. 2011; Li et al. 2019; Wilchek‐Aviad and Ne'eman‐Haviv 2016), but positively associated with adolescents' adaptations in various domains, such as self‐esteem, academic adjustment, daily well‐being, as well as life satisfaction (Blau et al. 2019; Ho et al. 2010; Kiang and Fuligni 2010). In contrast, a more complex picture has emerged regarding adolescents' search for life meaning. Some studies found that the search for meaning was related to adolescents' lower self‐esteem, lower stability in daily well‐being, as well as greater psychological distress (Kiang and Fuligni 2010; Li et al. 2019), whereas some other studies found that search for meaning had positive links with adolescents' subjective well‐being when they already had substantial meaning in life (Krok 2018). The search for meaning was also found to amplify the positive link between the presence of meaning and adolescents' health‐promoting behaviors (Brassai et al. 2015). In addition, null findings on the search for meaning were also identified in some studies (e.g., Blau et al. 2019).

2.3. The Role of Parental Social Comparison Shaming

As family is the most proximal microsystem for child development and parents are the primary caregivers, it constitutes a research priority with high applied value to identify parenting‐related antecedents to the emergence and development of children's meaning in life (Kealy et al. 2022). Yet, there is still largely a paucity of work in this direction, and research on whether and how psychologically controlling parenting practices would impact this asset remains especially scant. To the best of our literature search, only one study was identified. Using six‐wave longitudinal data from 2023 high school students in Hong Kong, Shek et al. (2021) found that paternal psychological control at Wave 1 negatively predicted adolescents' meaning of life at Waves 2 to 5 with small effect sizes, while maternal psychological control at Wave 1 did not predict adolescents' meaning of life at any subsequent wave.

Further, to our knowledge, there is no study available that particularly focuses on the link between parental social comparison shaming (as a psychological control strategy) and adolescents' meaning in life. Nonetheless, it is plausible that parental unfavorable comparisons likely induce children's feelings of shame and a sense of inferiority and thus threaten their self‐concept (Xing et al. 2023; Zhang and Yan 2024). Theoretically, an eroded self could be a salient risk precursor for the subsequent loss of life meaning as well as the lack of motivations and actions to search for life meaning (Baumeister 1991; Brassai et al. 2013; Fry 1998). Thus, we expect to identify associations between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' presence of and search for life meaning.

Moreover, to more effectively catalyze research on this front, we take one step further by elucidating through what processes and specifying under what conditions parental social comparison shaming would exert its influences on adolescents' meaning in life, as extant research and theories have suggested some plausible mechanisms that still await to be tested. Due to the scope limit, we aim to specifically examine the potential mediating role of child satisfaction of competence need and the potential moderating role of child filial piety beliefs. The underlying rationale is laid out as follows.

3. Child Satisfaction of Needs for Competence as a Potential Explanatory Mechanism

According to the self‐determination theory, satisfaction of the basic psychological need for competence fosters human thriving, and support for this need is among the necessary conditions for a person's growth, integrity, and well‐being (Ryan and Deci 2017). By definition, the psychological need for competence concerns “the sense of efficacy an individual has with respect to both internal and external environments” (Ryan et al. 2008, 153). It has to do with a person's ability to exercise his/her capacities to interact effectively with environments (Ryan and La Guardia 2000).

Parents play key roles in satisfying children's basic psychological needs by engaging in parenting behaviors that are responsive, supportive, and encouraging (Soenens et al. 2017). In contrast, when parenting behaviors are rejecting, unpredictable, and dominant, they will thwart the same basic psychological needs and lead to children's need frustration. Accordingly, due to its manipulative and intrusive nature, parental psychological control likely disrupts the autonomy–connection balance in parent–child relationships and likely hinders children's satisfaction of the basic psychological needs as well as contributes to children's need frustration, which has been widely shown in prior research (e.g., Costa et al. 2016; Peng et al. 2024).

Notably, both parental psychological control and child psychological need satisfaction have been examined as broad constructs in the extant studies. However, it seems plausible that, as a specific strategy of parental psychological control, social comparison shaming likely thwarts children's satisfaction of the basic need for competence in particular. The broader research on social comparison and its developmental consequences has indicated that although upward comparison could provide useful information and motivate people to improve themselves, unfavorable comparisons to superior others, especially those comparisons to close others and particularly in self‐relevant domains, would typically pose threats to self‐concept and likely contribute to feelings of inferiority and subsequent loss of self‐esteem (Gerber et al. 2018; McComb et al. 2023). As noted earlier, when engaging in social comparison shaming, parents would critically compare the behaviors and performance of their children to those of others to induce their children's feelings of shame about their inferiority (Camras et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2021). Such unfavorable comparisons and the resultant feelings of shame likely threaten children's self‐evaluations and erode their self‐efficacy, ultimately leading to their need for competence (Tsai et al. 2014; Xing et al. 2023; Zhang and Yan 2024). Furthermore, theoretically, meaningfulness arises partly from being effective in doing the activities that are self‐chosen and congruent with one's personal values (Baumeister 1991). Meaning in life is associated with an intrinsic need for environmental mastery, which could be obtained through developing a sense of self‐efficacy (Fry 1998). Positive beliefs in one's own abilities to accomplish tasks and goals are relevant to people's perceptions that they can, and ought to, pursue a valued life purpose and live a meaningful life (Brassai et al. 2013). Some empirical research has also demonstrated that the satisfaction of the need for competence is one important and unique predictor for meaning in life (Martela et al. 2018).

Taken altogether, it seems warranted to expect that parental social comparison shaming would be negatively associated with children's meaning in life indirectly through a negative association with children's satisfaction of need for competence. Yet, it is a twofold task to obtain an adequate delineation of the complex mechanisms that are implicated in the link between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' life meaning. In addition to elucidating the explanatory processes, it is also critical to understand heterogeneity in that link by specifying the conditions under which the effects may be altered. In the present study, we also seek to specifically examine child endorsement of filial piety as a potential moderator. Justifications for this focus are provided below.

4. Child Endorsement of Filial Piety as a Potential Moderator

Although psychologically controlling parenting appears to be universally detrimental for child development (Wang et al. 2007), the extent to which it would adversely affect children's adaptations may actually depend on how children interpret, attribute, and cope with the relevant parenting practices (Pomerantz and Wang 2009; Soenens et al. 2015). In terms of parental social comparison shaming, some studies have shown that when children interpreted their parents' critical comparison and shaming in a more positive manner (e.g., My parents' comparison behaviors are motivated by their good intentions, such as concern for my own good), the negative effects of such controlling behaviors could be mitigated (Camras et al. 2017; Cheah et al. 2019).

In the Chinese culture, children's attribution of psychologically controlling parenting is likely shaped by filial piety (Xiao, 孝). Essentially, filial piety involves a set of psychological schemas for parent–child interactions, which guide how children should attend to their parents (Bedford and Yeh 2019). The Dual Filial Piety Model (Yeh and Bedford 2003) proposed two filial piety attributes: reciprocity and authoritarianism (Bedford and Yeh 2019). Reciprocal filial piety entails “emotionally and spiritually [and also voluntarily] attending to one's parents out of [genuine] gratitude for their efforts in having raising one, and physical and financial care for one's parents as they age and when they die for the same reason,” whereas authoritarian filial piety encompasses “suppressing one's own wishes and complying with one's parents' wishes because of their seniority in physical, financial or social terms, as well as continuing the family lineage and maintaining one's parents' reputation because of the force of role requirements” (Yeh and Bedford 2003, 216). As such, reciprocal filial piety emphasizes physical and affectional reciprocity between parents and children (i.e., horizontal relations). Authoritarian filial piety accentuates the vertical structure of parent–child relationships and stresses children's normative submission to parental authority (Bedford and Yeh 2019).

In addition, the Contextual Model of Parenting Style (Darling and Steinberg 1993) proposed that the influences of parenting practices on adolescent outcomes could be conditioned by adolescents' willingness to be socialized (i.e., how open adolescents are to their parents' attempts to socialize them). Adolescents who have high levels of authoritarian filial piety may be more receptive to parents' psychologically controlling behaviors and tend to interpret such behaviors in a more benign light, given their endorsement of children's normative and unconditional obedience and submission to parental demands and authority. In contrast, adolescents with high levels of reciprocal filial piety are likely to be averse and resistant to parental mental intrusiveness and manipulation because of their strong inclination to view the parent–child relationship as a horizontal bond with mutual respect on a voluntary basis. Accordingly, it seems warranted to expect that the adverse association between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence might be stronger for adolescents with higher (versus lower) reciprocal filial piety; and this negative association might be weaker for adolescents with higher (versus lower) authoritarian filial piety.

The potential moderating roles of child filial piety in the associations between parenting practices and child development have been tested in prior research, but only two of them focused on parental psychological control in particular, and the findings were mixed. Among Chinese secondary school students, Lu et al. (2017) reported null findings with respect to the moderating roles of adolescents' reciprocal or authoritarian filial piety in the association between maternal psychological control and adolescent academic performance. In a sample of Chinese college students, Jorgensen et al. (2017) found that child filial piety moderated the relationship between parental psychological control and child self‐esteem. Specifically, maternal psychological control was negatively associated with child self‐esteem when children had high and moderate levels of filial piety, but was not related to each other when children reported lower levels of filial piety. Notably, in this study, child filial piety was examined as a broad construct without making a distinction between reciprocal and authoritarian attributes. In addition, in both studies, parental psychological control was measured as a broad construct. To the best of our knowledge, no research has ever tested the potential moderating roles of child reciprocal and authoritarian filial piety in the associations between parental social comparison shaming and child outcomes. In the present study, we will address this gap by testing the theoretically plausible hypotheses as stated earlier.

5. Overview of the Present Study

Parental social comparison shaming as a unique form of parental psychological control has been increasingly demonstrated, but how and why it may shape adolescents' adaptations still remains poorly understood, especially for the development of adaptive strengths. As adolescence represents a critical period in the life span when individuals start to reflect on their existential significance, living missions as well as life directions, the actively searching for and establishing a sense of life meaning appear to be stage‐salient activities. Theoretically, parental unfavorable upward social comparison is likely to hinder adolescents' life meaning processes through thwarting their satisfaction of the need for competence. On one hand, the broader research indicates that unfavorable upward social comparison can pose significant threats to self‐concept and lead to feelings of inferiority. On the other hand, theories on the development of human life meaning propose that fulfillment of basic needs for competence and developing a sense of self‐efficacy are highly relevant to people's perceptions that they can pursue a valued life purpose, which are key sources for their meaning in life. Lastly, social comparison shaming is shown to be a parental psychological control strategy that is more commonly adopted in Chinese (versus Western) parenting, which is deeply rooted in the Chinese Confucian traditions. As a core pillar of Confucian ethics, filial piety merits special attention when examining the implications of parenting practices for child development in Chinese family systems, given that Chinese children's perceptions, appraisals, and receptivity to parenting practices, including parental social comparison and shaming, are shaped by their filial piety values.

Against the aforementioned backdrop, this study aimed to understand the mechanisms implicated in the link between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' life meaning by leveraging three‐wave longitudinal data from Chinese adolescents during their junior high school years. In particular, we sought to test adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence as a mediator and adolescents' endorsement of filial piety as a moderator. The specific hypotheses were provided as follows. First, we hypothesized that parental social comparison shaming (Time 1) would be negatively associated with adolescents' life meaning (Time 3, controlling for the baseline) indirectly through a negative association with adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence (Time 2, controlling for the baseline). Further, we also expected to find that the negative link between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence would be stronger among adolescents with higher (versus lower) endorsement of reciprocal filial piety. In contrast, this link would be weaker among adolescents with higher (versus lower) endorsement of authoritarian filial piety. Ultimately, the identified indirect effects would be conditioned. Among adolescents with higher (versus lower) endorsement of reciprocal filial piety, the indirect effect from parental social comparison shaming to adolescents' life meaning through adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence would be stronger. This indirect effect would be weaker among adolescents with higher (versus lower) endorsement of authoritarian filial piety. Note that these patterns of hypotheses might apply more to the presence of life meaning than to the search for life meaning. As we reviewed earlier, the presence of life meaning has been consistently demonstrated in prior research to be an essential component of human well‐being and a cornerstone resource for human flourishing. In contrast, findings of previous studies on the nature and roles of the search for life's meaning still remain mixed. As such, the current analyses for the search for life's meaning are somewhat exploratory, and we do not offer specific hypotheses for it. Other than that, the present analyses represent mostly a confirmatory effort.

This study represents one of the initial efforts aimed at revealing the mediating and moderating mechanisms (i.e., satisfaction of need for competence and filial piety) underlying the associations of parental psychological control strategies in one specific form (i.e., social comparison shaming) with child development of one key adaptive strength (i.e., meaning in life) in a sample of Chinese adolescents. It moves beyond the prior research that has predominantly focused on parental psychological control as a broad construct and its direct and generic consequences for child psychopathology. Greater nuances identified by such scientific endeavors would more effectively inform the designs of interventions to facilitate adaptive parenting and positive youth development.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Data were drawn from a larger project on the links between family environment and Chinese adolescents' academic performance and mental health. Participants were recruited from a junior high school in Shanxi (山西省) and Yunnan (云南省), respectively. The schools were conveniently sampled based on the researchers' social network resources. With the help of homeroom teachers (班主任), research assistants introduced the study to adolescents and parents during the time of the weekly class meeting. After obtaining consent from adolescents and parents, adolescents were asked to complete a paper‐and‐pencil survey independently in the classroom, which took about half an hour. Adolescents received gifts (e.g., pens) as appreciation for their support. All procedures have been approved by the institutional review board of the study's home institution (i.e., Project Title: The Links of Family Environment with Adolescent Academic Performance and Mental Health. Review institution: The Review Committee on Biological and Medical Ethics at Beihang University, China. Protocol No. BM20240034).

In the present study, we used data from the first three waves of the larger survey. The first‐wave assessment of the survey was conducted in September 2022, when adolescents were in grade 7 in junior high school. In total, 962 students participated in the survey. The second‐wave and third‐wave assessments were conducted in March 2023 (n = 931, retention rate = 96.78%) and in September 2023 (n = 892, retention rate = 92.72%), respectively. Among the 962 students participating in the initial survey, 45.1% were boys (n = 434) and 54.9% were girls (n = 528), 67.4% were Han (汉) ethnicity (n = 648), 80.4% lived in urban areas (n = 773), 26.1% were the only child in the household (n = 251), and 89.6% were from two‐parent families (n = 862). The mean age of the participants at the 1st wave was 12.369 (SD = 0.699) The average level of family socioeconomic status (SES) at the 1st wave was 5.830 (mode = 5, median = 6, SD = 1.614), which was rated by students on the MacArthur Scale of subjective social status (Adler et al. 2000) using a ladder ranging from 1 to 10. We conducted multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) to examine the potential attrition bias and found that there were no non‐negligible differences in both the key study student variables and covariates assessed at the first wave between adolescents participating in the study across all three waves and adolescents who dropped out. All p‐values for the difference tests ranged from 0.127 to 0.950. Partial η 2 as a measure of effect size for all differences ranged from 0.000 to 0.003, which were far below the criterion value of 0.14 as a practically non‐negligible difference (Bandalos 2002; Cohen 1988).

2.2. Measures

All the used measures for key study variables have been demonstrated to be reliable and valid tools in previous research with samples of Chinese adolescents (e.g., Fang et al. 2022 for parental social comparison shaming; Li et al. 2014 for reciprocal and authoritarian filial piety; Lu et al. 2017 for satisfaction of basic needs with parents; and Li et al. 2019 for the presence of and search for life meaning). A detailed description of the measures was provided as follows. For readers' interest and also to better contextualize the measures, the full scales were provided in the File S1.

2.2.1. Parental Social Comparison Shaming (At the 1st Wave)

Adolescents completed the Psychological Control Scale (PCT; Fang et al. 2022), in which five items were designed for the assessment of parental social comparison shaming practice. Items, such as “When I misbehave, my parents tell me I am not as good as other children”, were rated on a 5‐point Likert scale, ranging from “1 = not at all true” to “5 = very true.” The Cronbach's alpha for this scale in the present sample was 0.938. Mean scores were calculated and used in analyses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of parental social comparison shaming. In the current study, adolescents reported their mothers' and fathers' social comparison shaming practices separately. Adolescents' reports of fathers' and mothers' social comparison strongly correlated with each other: r = 0.717, p < 0.001. Thus, we took an average of them to get an overall reflection of parental social comparison and shaming practice.

2.2.2. Reciprocal Filial Piety and Authoritarian Filial Piety (At the 1st Wave)

Adolescents completed the Dual Filial Piety Scale (DFPS; Yeh and Bedford 2004). The original DFPS has 16 items, with 8 items (e.g., “Be grateful to my parents for raising me”) for reciprocal filial piety and 8 items for authoritarian filial piety (“Take my parents' suggestions even when I do not agree with them”). Following the recent research using this scale among Chinese adolescents (Guo et al. 2022), one item was removed respectively for the authoritarian filial piety subscale (i.e., “Have at least one son for the succession of the family name”) and the reciprocal filial piety subscale (i.e., “Hurry home upon the death of my parents, regardless of how far away I am”). There was a particular rationale underlying such modifications. According to a pilot interview with Chinese early adolescents in previous research (Guo et al. 2022), it seemed difficult for some participants to adequately understand the item concerning the death of parents. They either had no idea about it or had never considered the behavior of “hastening home for the funeral upon the death of one's parent.” For the item on the responsibilities of having sons to carry the family blood lineage, our personal inquiries with the researchers who deleted this item in their studies (Guo et al. 2022) indicated that it was removed due to the still‐effective “One‐Child Policy” at the time. As such, it might be politically inappropriate to discuss this, and for participants in early adolescence, some of them might have never thought about this issue, which might bring in confusion and extra cognitive burdens in filling out the survey.

All used items were rated on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from “1 = extremely unimportant” to “5 = extremely important.” Sum scores were calculated for each subscale and used in analyses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of reciprocal/authoritarian filial piety. In the current sample, Cronbach's alpha of the overall DFPS was 0.811. Cronbach's alphas for the reciprocal and authoritarian filial piety subscales were 0.859 and 0.769, respectively.

2.2.3. Satisfaction of Basic Need for Competence With Parents (At the 2nd Wave)

Adolescents completed the Basic Need Satisfaction in Relationships Scale (BNS‐RS; La Guardia et al. 2000). The scale has 9 items and 3 subscales, including the autonomy subscale, the competence subscale, and the relatedness subscale. Each subscale had 3 items that were rated on a 5‐point Likert scale from “1 = not at all true” to “5 = very true”. In the current survey, adolescents were asked to report their perceived satisfaction of need for competence when they were with their fathers and mothers, respectively (e.g., “When I am with my father/mother, I feel like a competent person”). Mean scores were calculated and used in analyses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction of need for competence with parents. Considering that there was a strong correlation between adolescents' reports of perceived satisfaction of need for competence with mothers and with fathers (r = 0.759, p < 0.001), we took an average of them to get an overall reflection of adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence In the present sample, Cronbach's alpha for this subscale was 0.795.

2.2.4. Life Meaning (At the 3rd Wave)

Adolescents completed the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ; Steger et al. 2006). MLQ has ten items, which are rated on a 7‐point Likert scale ranging from “1 = absolutely untrue” to “7 = absolutely true”. The MLQ had two subscales. One is the presence of the meaning subscale, including five items (e.g., “I understand my life's meaning”). The other one is the search for meaning subscale, including five items (e.g., “I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful”). Mean scores were calculated and used in analyses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of presence of/search for life meaning. In the current sample, Cronbach's alpha of the overall MLQ was 0.829. Cronbach's alphas for the presence of meaning subscale and the search for meaning subscale were 0.874 and 0.919, respectively.

2.2.5. Covariates and Alternative Competing Mediators

In line with the MacArthur Scale of subjective social status (Adler et al. 2000), we used a ladder (ranging from 1 to 10) to measure students' perceived family SES. Adolescents' reports of family SES across the three waves were averaged to get an overall reflection of their family SES. Adolescents' gender (1 = boys, 2 = girls) and age assessed at the 1st wave were also considered as covariates. In addition to these demographic characteristics, a series of more substantive variables were also included in the primary model analyses. Adolescents' perceived satisfaction of needs for relatedness and autonomy (at the 2nd wave, measured by the BNS‐RS, Cronbach's αs = 0.848 and 0.825, respectively) were included as two alternative parallel mediators to adolescents' perceived satisfaction of need for competence (at the 2nd wave). This addition aimed to estimate the unique role of adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence (at the 2nd wave) in accounting for the associations between parental social comparison shaming (at the 1st wave) and adolescents' life meaning outcomes (at the 3rd wave) (Martela et al. 2018). In addition, the baseline levels (at the 1st wave) for all substantive variables were also controlled for in the primary analyses, including adolescents' perceived satisfaction of needs for relatedness, autonomy and competence (measured by the BNS‐RS, Cronbach's αs = 0.823, 0.778, and 0.748, respectively) and adolescents' presence of life meaning and search for life meaning (measured by the MLQ, Cronbach's αs = 0.831 and 0.868, respectively).

2.3. Analytic Strategies

Preliminary processing of the data was conducted with SPSS 28.0 (IBM Corp. 2021), including missing value processing, descriptive statistics, and correlation analysis. We followed the recommendation by Schlomer et al. (2010) to report missing values in the current dataset. The percentages of missing values across key study variables of interest ranged from 0.10% to 7.3% (Mean = 3.16, SD = 2.77), which were primarily due to attrition of participants across assessment waves. Results of Little's Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test (Little 1988) indicated that the missing pattern in the present data was not completely missing at random (χ 2 = 257.819, df = 171, p < 0.001). However, as χ 2 is rather sensitive to sample size, we further assessed the normed Chi‐Square (χ 2/df = 1.058), which was much smaller than the recommended criterion value of 2 (Bollen 1989), suggesting that the missing pattern in the current data still could be assumed to be completely at random (Adams et al. 2016). Taken collectively, to take full advantage of the available data and also to produce less biased estimates, we decided to adopt the full information maximum likelihood method (FIML) to handle the current missing values (Acock 2005; Schlomer et al. 2010) in the subsequent primary model analyses.

The primary model analyses were conducted using path analyses (Kline 2015) with Mplus 8.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2017). In the path model, adolescents' reports of parental social comparison shaming practice (at Time 1) were specified as an exogenous variable to predict their reports of meaning in life (at Time 3, while controlling for the baseline) as endogenous variables, including presence of meaning and search for meaning. Further, adolescents' perceived satisfaction of need for competence (at Time 2, while controlling for the baseline) was added as a potential mediator.

Adolescents' reports of reciprocal filial piety and authoritarian filial piety (at Time 1) were tested as potential moderators for the link between their reports of parental social comparison shaming practice (at Time 1) and their perceived satisfaction of need for competence (at Time 2). To test the moderating effects, mean‐centered parental social comparison shaming practice (at Time 1) was multiplied by mean‐centered reciprocal/authoritarian filial piety (at Time 1) to create two product terms, which were then added to the model to predict adolescents' perceived satisfaction of need for competence (at Time 2). To illustrate the patterns for the identified interactive effects, simple slope analyses were conducted following the recommendations by Aiken and West (1991). Specifically, simple slopes for the association between parental social comparison shaming (at Time 1) and adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence (at Time 2) was examined at the levels of +1 SD and −1 SD from the mean of the moderator (i.e., adolescents' filial piety at Time 1).

Given that our primary hypothesized mediating pathways (i.e., from parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 to adolescents' life meaning at Time 3 through adolescents' satisfaction of psychological need for their parents at Time 2) were directional, concerns might arise about the directionality and robustness of these pathways. To dispel such concerns, informed by prior methodological research (e.g., Maxwell et al. 2011), we conducted an additional set of analyses, in which an alternative model was tested to show whether mediating pathways in the opposite direction also existed. Specifically, on the basis of the original mediating model without any moderators, paths from adolescents' life meaning at Time 1 to parental social comparison shaming at Time 3 through adolescents' satisfaction of psychological need with their parents at Time 2 were further added.

We used various indices (Kline 2015) to evaluate model fit for all models, including Comparative Fit Index (CFI, values > 0.90 as acceptable), Tucker‐Lewis index (TLI, values > 0.90 as acceptable), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR values < 0.08 as acceptable), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, values < 0.08 as acceptable). We used the bootstrapping technique (Preacher and Hayes 2008) to test the indirect effects (resamples = 5000). If the 95% confidence interval (CI) for unstandardized indirect effects does not include zero, it indicates that the indirect effect is significant. Last, to test the conditional indirect effects, the mediating model was conducted using the bootstrapping technique with 5000 resamples at the higher and lower adolescents' filial piety at Time 1 (i.e., 1SD above and 1SD below the mean).

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for study variables were presented in Table 1. At the zero‐order, bivariate level, intercorrelations among key study variables were generally in line with expectations. Further, a series of path models was conducted.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for and zero‐order bivariate intercorrelations among variables.

| Study variables and covariates | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study variables | ||||||||

| 1. Parental social comparison shaming practice (T1) | — | |||||||

| 2. Child reciprocal filial piety (T1) | −0.224 | — | ||||||

| 3. Child authoritarian filial piety (T1) | 0.069 | 0.264 | — | |||||

| 4. Child satisfaction of need for competence with parents (T2) | −0.401 | 0.257 | −0.055 | — | ||||

| 5. Child satisfaction of need for autonomy with parents (T2) | −0.456 | 0.304 | −0.006 | 0.670 | — | |||

| 6. Child satisfaction of need for relatedness with parents (T2) | −0.443 | 0.329 | 0.059 | 0.638 | 0.787 | — | ||

| 7. Child presence of life meaning (T3) | −0.222 | 0.220 | 0.029 | 0.328 | 0.297 | 0.295 | — | |

| 8. Child searches for life's meaning (T3) | 0.005 | 0.039 | 0.039 | −0.019 | −0.002 | −0.003 | 0.104 | — |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Child satisfaction of need for competence with parents (T1) | −0.447 | 0.253 | −0.076 | 0.506 | 0.480 | 0.446 | 0.250 | 0.004 |

| Child satisfaction of need for autonomy with parents (T1) | −0.547 | 0.366 | 0.007 | 0.454 | 0.618 | 0.563 | 0.201 | 0.005 |

| Child satisfaction of need for relatedness with parents (T1) | −0.476 | 0.367 | 0.092 | 0.433 | 0.557 | 0.612 | 0.223 | −0.004 |

| Child presence of life meaning (T1) | −0.312 | 0.316 | 0.043 | 0.308 | 0.314 | 0.317 | 0.402 | 0.023 |

| Child searches for life meaning (T1) | 0.095 | 0.079 | 0.124 | −0.099 | −0.080 | −0.061 | 0.008 | 0.321 |

| Child gender (T1) | −0.050 | 0.017 | −0.143 | −0.070 | −0.026 | −0.107 | −0.102 | 0.033 |

| Child age (T1) | −0.002 | −0.064 | −0.041 | −0.034 | 0.029 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.022 |

| Family socioeconomic status (the mean of T1, T2, and T3) | −0.218 | 0.078 | 0.084 | 0.196 | 0.169 | 0.177 | 0.224 | 0.064 |

| Mean or sum score | 2.351 | 31.844 | 20.465 | 3.566 | 3.898 | 4.103 | 25.711 | 24.552 |

| Standard deviation | 1.208 | 4.423 | 5.437 | 0.927 | 0.980 | 0.906 | 7.320 | 8.238 |

| Sample size | 961 | 953 | 952 | 934 | 934 | 934 | 892 | 892 |

Note: The codes for child gender: 1 = Boys, 2 = Girls. T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2, and T3 = Time 3. Significant correlations with p values at least < 0.05 (two‐tailed) are bolded.

3.1. Results for the Primary Model Without Moderators: Testing the Mediating Role of Adolescents' Competence Need Satisfaction

The mediation model without moderators, as depicted in Figure 1 fit the data well: Chi‐Square = 146.216, df = 29, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.065 with a 90% CI [0.055, 0.075], CFI = 0.955, TLI = 0.914, SRMR = 0.048. Parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 was negatively associated with adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence with their parents at Time 2 (β = −0.271, p < 0.001), which in turn was significantly and negatively associated with adolescents' presence of life meaning at Time 3 (β = 0.147, p = 0.001) rather than adolescents' search for life meaning at Time 3. Further, results of bootstrapping analyses indicated a significant indirect effect from parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 to adolescents' presence of life meaning at Time 3 through adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence with their parents at Time 2 (b = −0.215, SE = 0.071, 95% CI [−0.372, −0.113], β = −0.036, p = 0.002).

FIGURE 1.

Results for the primary model without moderators. All coefficients are standardized and identified with covariates included. In addition to the T1 baseline controls for the mediators and outcomes, other demographic covariates included: Child Age and Gender (at T1) and Family SES (mean of T1, T2, and T3). For clarity, (a) pathways with p > 0.05 (two‐tailed) are depicted in gray dash lines and pathways with p < 0.05 (two‐tailed) are depicted in black solid lines; (b) the relevant coefficients for nonsignificant correlation lines or predicating paths are not reported but available from authors upon request; and (c) the correlation lines and predicting paths involving demographic covariates are not depicted and the relevant coefficients are not reported but available from authors upon request. T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2, and T3 = Time 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (two‐tailed).

Notably, the mediating role for adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence at Time 2 was identified, while adolescents' satisfaction of need for relatedness and autonomy with their parents at Time 2 was also included in the model as parallel, competing mediators. That is, adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence at Time 2 uniquely accounted for the association between parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 and adolescents' presence of life meaning at Time 3 above and beyond the effects of adolescents' satisfaction of need for relatedness and autonomy at Time 2. Parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 was negatively associated with adolescents' satisfaction of need for relatedness and autonomy with their parents at Time 2 (β = −0.280, p < 0.001 and β = −0.271, p < 0.001, respectively). However, neither of the two forms of psychological need satisfaction at Time 2 was significantly associated with adolescents' life meaning outcomes at Time 3.

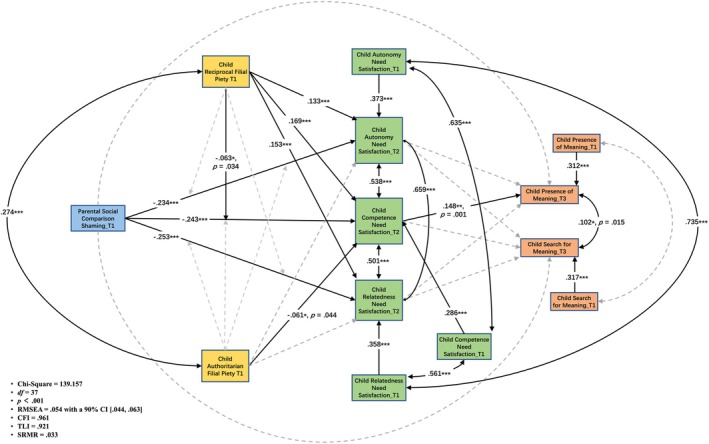

3.2. Results for the Primary Model With Moderators: Testing the Moderating Roles of Adolescents' Filial Piety Beliefs

The model with moderators (see Figure 2) also fit the data well: χ 2 = 139.157, df = 37, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.054 with a 90% CI [0.044, 0.063], CFI = 0.961, TLI = 0.921, SRMR = 0.033. Adolescents' reciprocal filial piety at Time 1 moderated the association between parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 and adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence (rather than relatedness or autonomy) with parents at Time 2 (β = −0.063, p = 0.034 for the interaction). In contrast, no moderating roles were identified for adolescents' authoritarian filial piety at Time 1.

FIGURE 2.

Results for the primary model with moderators. All coefficients are standardized and identified with covariates included. In addition to the T1 baseline controls for the mediators and outcomes, other demographic covariates included: Child Age and Gender (at T1) and Family SES (mean of T1, T2, and T3). For clarity, (a) pathways with p > 0.05 (two‐tailed) are depicted in gray dash lines and pathways with p < 0.05 (two‐tailed) are depicted in black solid lines; (b) the relevant coefficients for nonsignificant correlation lines or predicating paths are not reported but are available from authors upon request; and (c) the correlation lines and predicting paths involving demographic covariates are not depicted and the relevant coefficients are not reported but are available from authors upon request. T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2, and T3 = Time 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (two‐tailed). For readers' curiosity, in a separate model (which was constructed on the basis of the model depicted above), we tested the potential moderating roles of reciprocal and authoritarian filial piety in the direct associations between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' life meaning outcomes. Yet, due to the sparseness and counterintuitive nature of significant results and also to keep the primary analyses coherent and focused, we presented this additional set of analyses in the File S2.

Simple slopes to illustrate the identified interaction were depicted in Figure 3. There was a stronger negative association between parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 and adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence with their parents at Time 2 among adolescents endorsing higher reciprocal filial piety at Time 1 (b = −0.225, SE = 0.034, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.292, −0.157]) than among adolescents endorsing lower reciprocal filial piety at Time 1 (b = −0.140, SE = 0.029, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.196, −0.083]), although both associations were significant.

FIGURE 3.

Illustration of the moderating role of child reciprocal filial piety (T1) in the link between parental social comparison shaming (T1) and child satisfaction of need for competence (T2). T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2, and T3 = Time 3.

3.3. Further Testing the Conditional Indirect Effects Involving Adolescents' Competence Need Satisfaction and Reciprocal Filial Piety

Ultimately, conditional indirect effects were further identified in the subsequent bootstrapping analyses. Among adolescents endorsing higher reciprocal filial piety at Time 1, there was a significant indirect effect from parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 to adolescents' presence of life meaning at Time 3 through adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence with their parents at Time 2 (b = −0.265, SE = 0.089, p = 0.003, 95% CI [−0.468, −0.111]). Likewise, among adolescents endorsing lower reciprocal filial piety at Time 1, there was also a significant (yet smaller) indirect effect from parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 to adolescents' presence of life meaning at Time 3 through adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence with their parents at Time 2 (b = −0.165, SE = 0.061, p = 0.007, 95% CI [−0.311, −0.070]).

3.4. Results for an Alternative Model Demonstrating the Directionality and Robustness of the Hypothesized Mediating Pathway

The model as depicted in Figure 4 fits the data well: χ 2 = 132.874, df = 30, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.060 with a 90% CI [0.050, 0.070], CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.923, SRMR = 0.036. Results of bootstrapping analyses indicated three indirect effects. There was a significant indirect effect from parental social comparison shaming at Time 1 to adolescents' presence of life meaning at Time 3 through adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence with their parents at Time 2 (b = −0.200, SE = 0.067, 95% CI [−0.344, −0.084], β = −0.033, p = 0.003). In contrast, a significant (yet much smaller) indirect effect also emerged from adolescents' presence of life meaning at Time 1 to parental social comparison shaming at Time 3 through adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence with their parents at Time 2 (b = −0.002, SE = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.005, −0.001], β = −0.014, p = 0.025). More importantly, results of the follow‐up difference test indicated that the indirect effect, as we originally hypothesized, was significantly larger than that for the alternative mediating pathway in the reverse direction (b = −0.198, SE = 0.067, 95% CI [−0.343, −0.081], p = 0.003). In addition, another indirect effect also emerged in this set of analyses, which was from adolescents' presence of life meaning at Time 1 to parental social comparison shaming at Time 3 through adolescents' satisfaction of need for autonomy with parents at Time 2 (b = −0.003, SE = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.006, −0.001], β = −0.019, p = 0.025).

FIGURE 4.

Results for an alternative model demonstrating the directionality and robustness of the hypothesized mediation pathway. All coefficients are standardized and identified with covariates included. In addition to the T1 baseline controls for the mediators and outcomes, other demographic covariates included: Child Age and Gender (at T1) and Family SES (mean of T1, T2, and T3). For clarity, (a) pathways with p > 0.05 (two‐tailed) are depicted in gray dashed lines and pathways with p < 0.05 (two‐tailed) are depicted in black solid lines; (b) the relevant coefficients for nonsignificant correlation lines or predicting paths are not reported but available from authors upon request; and (c) the correlation lines and predicting paths involving demographic covariates are not depicted and the relevant coefficients are not reported but available from authors upon request. T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2, and T3 = Time 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (two‐tailed).

4. Discussion

The central goal of this study was to understand how and why parental social comparison and shaming practices may disrupt Chinese adolescents' development of meaning in life. Mostly in line with our hypotheses, parental earlier social comparison shaming practice was found to be negatively associated with adolescents' subsequent presence of life meaning. Further, results also indicated that one process through which this negative consequence occurred was adolescents' compromised satisfaction of need for competence with their parents. Ultimately, such an indirect effect was found to be stronger among adolescents who valued higher (versus lower) reciprocal filial piety. No associations emerged for adolescents' search for life meaning, and no moderating roles were identified for adolescents' endorsement of authoritarian filial piety. This study contributes to the literature by serving as one of the initial scientific efforts that try to elucidate the complex mechanisms underlying the developmental ramifications of parental social comparison and shaming practice.

4.1. Parental Social Comparison Shaming Hindered Adolescents' Presence of Life Meaning

As an important form of parental psychological control, social comparison shaming has long been viewed as a normative parental discipline practice in China (Fung 2006), which reflects Chinese parents' active efforts to “Guan (管)” their children and ensure children to improve themselves and “fit in” (Chao 1994; Cheung and Pomerantz 2011). Yet, by indicating that parental social comparison shaming could preclude Chinese adolescents from experiencing their lives as comprehensible and from developing a sense of purpose in their lives, results of our study appear to call for a reconsideration of the developmental consequences of parental social comparison shaming in Chinese families, despite Chinese parents' typically “good” intentions underlying this strategy.

Indeed, research that indicated the detrimental consequences of parental social comparison shaming for Chinese children's well‐being is accumulating. Chinese children appear to become increasingly critical of parental discipline based on shaming, and they question the effectiveness of such strategies in facilitating them to achieve optimal development (Smetana et al. 2021; Helwig et al. 2014). It is thus unsurprising to find that several recent studies consistently revealed negative links of parental social comparison shaming with Chinese children's and adolescents' adaptation in various domains (Chen et al. 2021; Fang et al. 2022; Zhang and Yan 2024).

Note that the unique contribution of the present study is providing initial evidence demonstrating that the harms of parental social comparison shaming for adolescent development may extend to the life meaning domain. Living in a world characterized by increasing complexity and uncertainty, establishing a sense of life meaningfulness is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone intrapersonal asset or resource for human well‐being and flourishing (Li et al. 2021; Steger 2018). Developing meaning in life seems especially critical during adolescence, given the age‐graded developmental tasks related to identity exploration (Negru‐Subtirica et al. 2016). Typically, it is during adolescence that people start to reflect on existential questions regarding the significance of one's being as well as the directions and goals of one's life (Chen et al. 2022; Russo‐Netzer and Shoshani 2020). Furthermore, the presence of life meaning has been widely shown to be a critical antecedent to adolescent well‐being and a protective factor against adversities (Blau et al. 2019; Brassai et al. 2011; Ho et al. 2010; Li et al. 2019; Kiang and Fuligni 2010). Exposure to parental unfavorable social comparisons would contribute to children's increased feelings of shame and inferiority and thus pose significant threats to their self‐concept, likely resulting in low self‐esteem and negative self‐evaluation (Zhang and Yan 2024). Further, an impaired inner psychological world (e.g., the self) could trigger the loss of life meaning (Baumeister 1991; Fry 1998).

4.2. Adolescents' Competence Need Satisfaction as an Explanatory Mechanism

As proposed by the self‐determination theory, parents play critical roles in satisfying children's basic psychological needs (Soenens et al. 2017). Parental psychological control as a manipulative and intrusive parenting strategy could frustrate children's satisfaction of basic needs (Costa et al. 2016; Peng et al. 2024). Results of the present study provide support to this theory by showing that parental social comparison shaming could dampen children's satisfaction of the basic psychological need for competence, which serves as one mechanism accounting for why parental social comparison shaming may hinder children's presence of meaning in life. Indeed, by definition, when engaging in social comparison shaming, parents would unfavorably compare the performance of their children to those of peers to induce children's feelings of shame about their inferiority (Camras et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2021; Yu et al. 2015). Such comparisons are likely to hurt children's self‐esteem and damage their self‐confidence (Tsai et al. 2014; Xing et al. 2023; Zhang and Yan 2024). Our findings also converge with the broader social comparison research showing that unfavorable social comparisons to close others in self‐relevant domains are especially threatening to one's self‐concept and likely result in a substantial loss of self‐esteem subsequently (Gerber et al. 2018; McComb et al. 2023).

Further, life meaning theorists propose that meaningfulness partly derives from one's being effective in accomplishing goals and the establishment of environmental mastery and a sense of self‐efficacy (Baumeister 1991; Fry 1998). In line with this proposition, results of some prior studies suggest that people with the need for competence unfulfilled tend to suffer from a lack of meaning in life (e.g., Yalçın 2023), whereas satisfaction of the need for competence could be one important and unique contributor to the presence of meaning in life (e.g., Martela et al. 2018). Our study adds to these studies by highlighting competence need satisfaction as a key source of meaning in life.

Last, it is also important to contextualize our current identification of competence need satisfaction as an explanatory mechanism in adolescence. Positive beliefs in their abilities to achieve goals and accomplish tasks are especially relevant to adolescents' perceptions that they can pursue a valued life purpose and live a meaningful life (Brassai et al. 2013). In addition, considering the radical and dynamic changes across multiple systems and domains during adolescence (Sisk and Gee 2022), building a solid sense of competence out of a sufficient satisfaction of competence need in important social relations would help adolescents navigate the various challenges they inevitably encounter across this stressful and transitional life period (Masten 2007). As such, it seems practically important to replace parental unfavorable social comparison shaming practices with some more adaptive forms of discipline so as to effectively satisfy adolescents' competence need and facilitate their establishment of meaning in life as well as growth of resilience against developmental stressors.

4.3. The Shaping Role of Adolescents' Reciprocal Filial Piety

Cross‐cultural research on the developmental implications of parental psychological control practices is extensive (e.g., Wang et al. 2007), but within‐culture heterogeneity awaits to be more thoroughly revealed by investigating factors that may shape the differential susceptibility of children from the same cultural background to the consequences of parental psychological control. Findings of our study highlight that adolescents' reciprocal filial piety orientation is among such factors. We found that the link between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' satisfaction of need for competence was stronger among adolescents with higher (versus lower) endorsement of reciprocal filial piety. Further, the negative indirect effect from parental social comparison shaming to adolescents' presence of life meaning through their compromised satisfaction of need for competence was stronger among adolescents with higher (versus lower) endorsement of reciprocal filial piety.

Adolescents who highly endorse reciprocal filial piety tend to believe that children's respect for parents should be out of gratitude on a voluntary basis and there should be mutual respect and status equality in parent–child relationship (Bedford and Yeh 2019, 2021). In the face of parents' social comparison shaming, these adolescents tend to be averse and resistant, indicating low willingness to be psychologically controlled and low openness to parental mental intrusiveness (Darling and Steinberg 1993). In their eyes, parental social comparison shaming is unlikely to be out of care and concern for children's own good, but represents parents' attempts to manipulate children's cognitions and emotions. As a result, such negative interpretations would amplify the negative influences of parental social comparison shaming on children's adaptation (Camras et al. 2017; Cheah et al. 2019).

Alternatively, children's internalization process of parents' beliefs and practices is influenced by parent–child relatedness and interaction patterns (Asakawa and Csikszentmihalyi 2000; Bao and Lam 2008; Deci and Ryan 2000). Supportive parent–child relationships, which are positively associated with child reciprocal filial piety, likely facilitate child internalization of parental expectations (Chen and Ho 2012). Accordingly, adolescents with stronger reciprocal filial piety, who are likely living in families characterized by more harmonious and supportive parent–child relationships (Chen et al. 2016), may more readily internalize parental unfavorable social comparisons, leading to their lower self‐esteem and higher competence need frustration.

Unfortunately, we did not measure adolescents' perceptions and appraisals of parental social comparison shaming practice and thus could not test the aforementioned explanations. Yet, built on our study, future research will benefit from directly assessing children's perceptions and appraisals of parental psychologically controlling strategies, and further examining their links with children's filial piety beliefs as well as their potential roles in shaping the implications of parental psychologically controlling strategies for child development (Helwig et al. 2014; Smetana et al. 2021).

4.4. The Null Findings on the Moderating Role of Adolescents' Authoritarian Filial Piety

Inconsistent with our hypothesis, no moderating roles of adolescents' authoritarian filial piety were identified for the link between parental social comparison shaming and adolescents' basic psychological need satisfaction. Our tentative explanations for such null findings are twofold. First, despite their relatedness, reciprocal filial piety represents a more active form of filial piety (i.e., voluntarily want to do out of gratitude), whereas authoritarian filial piety reflects a more passive one (i.e., have to do because of obligation) (Bedford and Yeh 2019; Yeh and Bedford 2003). Thus, adolescents with stronger authoritarian filial piety values, compared with those with stronger reciprocal filial piety values, may experience less autonomy in intergenerational interactions and thus be less receptive to the influences of their parents (Darling and Steinberg 1993; Deci and Ryan 2002). The relatively “rigid” and “passive” nature of authoritarian filial piety might limit its power in shaping the influences of parenting practices on child development (Li et al. 2018).

In addition, prior research (e.g., Liu and Chong 2024) also suggests that the moderating effects of authoritarian filial piety might be more specific to the associations of adverse family experiences with psychopathology outcomes than with positive mental health outcomes, as it likely fosters negative traits such as feelings of helplessness, worthlessness, and cognitive conservatism. In contrast, the moderating roles of reciprocal filial piety might be more specific to the links of adverse family experiences with positive mental health outcomes than with psychopathology outcomes, given it is closely related to positive traits such as empathy, emotional intelligence, and cognitive flexibility. In the present study, we focused on satisfaction of basic psychological needs as positive outcomes and only identified the moderating role of reciprocal filial piety. Future research may test if the moderating roles of authoritarian filial piety would emerge when psychopathology outcomes are examined.

4.5. The Null Findings on Adolescents' Search for Life Meaning

It seems unsurprising to get null results on adolescents' search for life meaning in the current analyses, in light of the highly mixed findings in prior studies on the associations of search for life meaning with a host of outcomes (e.g., subjective well‐being) and the still ongoing debate with respect to its nature and conceptualization (see Li et al. 2021). In contrast, the presence of life meaning has been consistently linked with greater well‐being in prior research. By definition, search for life meaning refers to “the dynamic, active effort people expend trying to establish and/or augment their comprehension of the meaning, significance, and purpose of their lives” (Steger, Kawabata, et al. 2008, 661). On one hand, the search for life meaning appears to represent a personal asset, approaching orientation, or driving force that motivates people to seek new opportunities, mobilize their resources, and overcome difficulties for a better understanding of life. In this way, it likely contributes to increased well‐being. On the other hand, the search for life meaning could also reflect a life state characterized by confusion, frustration, as well as vulnerability, which is likely associated with maladjustment and psychopathology (Kiang and Fuligni 2010; Li et al. 2019). We speculate that given such complexity in the conceptualization of the search for life's meaning, the effects of different sub‐components might counterbalance each other, leading to nonsignificant findings. Nevertheless, it is still pressing for future research to clarify the connotation and nature of search for life meaning and also specify its distinct antecedents (from those for presence of life meaning) as well as the conditions for its relations with various life outcomes (Brassai et al. 2015; Krok 2018; Li et al. 2021; Steger, Kawabata, et al. 2008; Steger, Kashdan, et al. 2008).

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

First, although we arranged predictors, mediators, and outcomes at different waves and autoregressively controlled for the baselines of both mediators and outcomes, the correlational nature of the current data still precluded us from making causal inferences. Second, the shared‐method and shared‐informant variance bias may inflate the identified associations. Relatedly, parenting behaviors were measured exclusively with adolescents' reports, but there could be incongruence and discrepancy between parents' and children's perceptions (Zhang and Wang 2024). Future research will benefit from using multiple‐method and multiple‐informant designs. Third, the high correlations in the current sample between adolescents' reports of paternal and maternal behaviors did not allow us to explore if there could be meaningful differences between fathers and mothers in the model, which may represent an important direction for future research (Romm and Alvis 2022). Fourth, our null findings regarding adolescents' search for life meaning appear to highlight the complex nature of this construct. As discussed earlier, greater research attention should be paid to the potentially different predictors and developmental consequences of various “search for life meaning” components. Unfortunately, in the present study, we did not approach the search for life's meaning from a multi‐dimensional or multi‐component perspective, which should be addressed in future studies.

Last, considering that parental psychological control has long been conceptualized as multidimensional (Fang et al. 2022; Yu et al. 2015), in addition to social comparison, there also are other important strategies (e.g., shared shame, love withdrawal, harsh psychological control, and relationship‐oriented guilt induction). As such, a number of important research questions still await systematic examination, including the relative, unique influences of different strategies, the potential specificity in the links between different strategies and child adaptation in various domains, as well as the possible interactions among these strategies in shaping child development (e.g., variable‐centered moderations and person‐centered configuration profiles). Addressing these questions is beyond the scope of the present study but merits future endeavors.

5. Conclusions and Implications

Most centrally, results of the present study suggest that parental social comparison shaming practice may hinder Chinese adolescents' presence of life meaning through thwarting their satisfaction of psychological need for competence, and this effect appears to be especially strong for adolescents who highly endorse reciprocal filial piety. Notably, in China, social comparison shaming is a parenting strategy still widely adopted by many parents. Our findings contribute to the literature by revealing some of the processes and conditioning mechanisms that are implicated in the negative ramifications of parental social comparison shaming. To obtain a more nuanced and thorough understanding of the link between parental psychological control and child development, we call for more researchers to join us in examining how and why parental psychological control in its specific forms would influence child development. By doing so, this field can be effectively moved forward.

Our findings are also practically informative. Culturally, parental social comparison shaming has long been believed to be a normative parental discipline strategy in China that reflects parental concerns and training involvement for the sake of children's improvement. As such, it is still widely used even in contemporary Chinese families. Our findings call for caution with respect to this parenting practice. It seems important to raise Chinese parents' awareness regarding the side effects of social comparison shaming for children's development. Parenting‐related training programs should bring it to Chinese parents' attention that unfavorably comparing their children with others might not be a developmentally effective way to stimulate children's self‐improvement; instead, it would likely impair children's confidence in their competence and even disrupt the growth of their spiritual world and make them lose a sense of meaning for life. Replacing such unfavorable comparison practices with the more adaptive forms of discipline should be an important goal of parenting training programs. Moreover, the parental social comparison shaming practice appears to be especially harmful for children who believe that the parent–child relationship should be a horizontal one with mutual respect. As such, children's personal values and beliefs are critical factors that merit more attention while designing and tailoring relevant parenting interventions.

Author Contributions

The current order of authorship corresponds to the authors' relative contributions to the research effort reported in the manuscript. Hongjian Cao: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, supervision, visualization, writing – original draft. Nan Zhou: formal analysis, funding acquisition, supervision, writing – review and editing. Yuhan Wang: formal analysis, visualization. Yang Liu: data curation, investigation, project administration, writing – review and editing.

Ethics Statement