Introduction

Major health disparities have been identified among youth with rheumatic diseases. In particular, recent studies in pediatric rheumatology have found that youth from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds report worse quality of life and experience worse disease outcomes, delays in care, and even sub-optimal treatment. This aligns with the greater body of health disparity literature that documents the significant impact of social determinants of health on a wide spectrum of health outcomes among children and adolescents1. In this review we discuss the current literature on health and healthcare disparities affecting youth with rheumatic diseases, intervention studies that have aimed to mitigate disparities, and strategies to achieve healthcare equity that urgently require investigation within pediatric rheumatology.

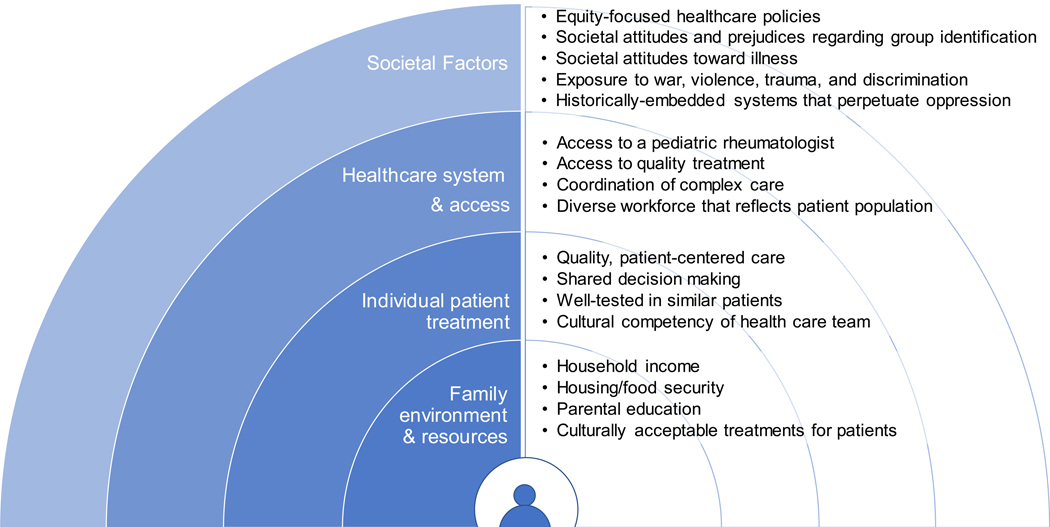

Healthy People 2020 defines health disparity as “a health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage”2 . Furthermore, healthcare disparities can be attributed to disparities in financial resources available for health spending, as well as structural and institutional barriers that prevent equitable delivery of health services2. While health differences exist across the spectrum of health outcomes, health disparities are those that are systematic, avoidable, unfair, and unjust3. Social-ecological models, adapted from Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model of human development4, can be used to help define the nested factors related to familial, individual care, health systems, and broader societal environments that contribute to health and healthcare disparities in pediatric rheumatology (Fig. 1)5.

Figure 1. Modified Social-Ecological Model of Contributors to Health Disparities in Pediatric Rheumatology.

Potential societal, institutional, individual care, and familial determinants of health disparities among youths with pediatric rheumatic diseases. This conceptual framework is based on Reifsnider et al.’s modified Bronfenbrenner social-ecological model5.

Characteristically health disparities affect socially disadvantaged populations who experience barriers to optimal health created by historically-embedded practices of systemic racism and individual and institutional discrimination based on racial/ethnic group, religion, socioeconomic status (SES), gender, mental health, disability, sexual orientation and geographic region2. Social determinants of health are personal, social, economic, and environmental factors that shape an individual’s health2. These factors are primary drivers of health and healthcare disparities among socially disadvantaged racial/ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic groups6. Despite their critical role in other health outcomes, research in social determinants of health in pediatric rheumatology treatment delivery and disease outcomes remains sparse. Robust health and healthcare disparity research is crucial to the development of appropriate changes in practice and health policy to address health equity in pediatric rheumatology.

Disparities in childhood-onset SLE (cSLE)

Health disparities in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) have received more attention in pediatric rheumatology research than disparities in most other rheumatologic diseases. This attention is warranted as cSLE can be a deadly disease, more so with sub-optimal treatment. In young adults SLE is even more deadly than in other age ranges 7 and cSLE is more deadly compared to adult-onset SLE8. Morbidity associated with cSLE is particularly high in young adults of minority race/ethnicities. In the US, SLE ranks as the 5th cause of death among Black and Hispanic females ages 10–25 years old9.

Despite the attention given to disparities along race/ethnicity, major gaps in the cSLE literature exist for other social determinants of health. Few studies have examined income, education, and other factors associated with systemic barriers to health equity.

Disparities in Health in cSLE

There are striking differences in prevalence across race/ethnicities for SLE both in pediatric and adult populations. The prevalence of cSLE is especially high in indigenous peoples around the globe, including Native American/First Nation Canadians, Maori people of New Zealand, and the Aboriginal people of Australia10–14. The highest prevalence of cSLE, like SLE, is documented in Native American and First Nation Canadians. The prevalence in Native American children is around 13 per 100,000 and at least 3 times that of the general population10, 11. Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian youth have higher prevalence than white youth10.

The largest effort to identify disparities across race/ethnicity in SLE was through the LUMINA study (Lupus in Minorities: Nature versus Nurture) in the US15. While this study primarily examined adults, a proportion of participants were pediatric age. Research out of the LUMINA study established that both Hispanic and Black Americans had worse disease activity scores, worse patient reported outcomes, and worse organ involvement (specifically cardiac and renal). In line with this, Hispanic and Black Americans were more likely to be treated with more steroids and cyclophosphamide, likely indicating worse disease16–22.

Indeed, differences in cSLE disease severity between Black and white youth is evident from several other studies, as well. Studies in cSLE have consistently demonstrated that Black youth are more likely to have the most severe forms of organ involvement associated with SLE, including renal, neurologic, and cardiac disease23–25. Furthermore, Black youth with cSLE are more likely to have SLE organ-related disease than even Black adults with adult-onset SLE, with more renal, neurologic, hematologic and ocular manifestations26, 27.

Worldwide, non-white youth with cSLE have worse disease outcomes compared to white youth. Black youth from low-resource areas demonstrate the highest rates of end-organ disease and morbidity. In the PULSE cohort from South Africa, Black South African children had more end-organ damage (63% vs 23%) than Black American youth from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) registry, and more Black youth from the PULSE cohort required renal transplantation (8% vs. <1%)28.

Frequent hospitalizations in cSLE are associated with increased morbidity and mortality and disparities in hospitalizations of cSLE patients based on race/ethnicity have also been identified, with Black and Hispanic youth being overrepresented7. Demographic factors associated with increased length of stay in the hospital include other race than white or Black and urban location, after accounting for important clinical factors such as lupus nephritis7. Mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System of the National Center for Health Statistics shows that the Black/white mortality rate was 5.7 for patients aged 0–24 in 1995– 1997 which increased to 6.7 in 2015–201729. Another recent national study of youth enrolled in Medicaid (an indicator of low income) showed that Black race and hospital location in the Southern US were among the strongest risk factors for hospitalization mortality, even after accounting for lupus nephritis and young adult age (age 18–20)7. The mortality of Black youth with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) from lupus nephritis is twice that of their white counterparts10.

Disparities in Healthcare in cSLE

Health disparities observed in cSLE may be related to or a direct result of disparities in healthcare, specifically disparities in access and treatment. However, few studies to date have examined disparities in quality of care, access in care, and treatment in cSLE. The studies to date that have attempted to examine these questions indicate important disparities in healthcare along race/ethnicity and income. A study of the CARRA registry found that delays in diagnosis of >1 year were more likely in youth with cSLE from low-income families and that youth living in a state with a high density of pediatric rheumatologists were more likely to be seen expeditiously30. Youth with ESRD from lupus nephritis in the US Renal Data System were less likely to receive renal transplants if they were Black, Hispanic, older, or on Medicaid10.

Among the co-morbidities in SLE that are highly associated with worse quality of life, are mental health disorders. Approximately a third of youth with cSLE have clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or anxiety31. While in studies of single-center cohorts Black youth appear to be more affected32, in a large study of a national Medicaid sample, Black youth were less likely to be diagnosed with depression or anxiety and less likely to receive pharmacotherapy33. Beyond affecting quality of life, this disparity may have important implications on SLE disease outcomes. Depression symptoms are associated with worse medication adherence in youth34 and among cSLE youth with mental health disorders, mental health treatment, including the use of pharmacotherapy, improves adherence35.

Disparities in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common pediatric rheumatologic disease and is associated with an increased risk for morbidity and disability36. According to the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) JIA is comprised of seven subtypes that vary by clinical characteristic, and classically by the number of affected joints and extraarticular symptoms37.

Health Disparities in JIA

Overall, the global prevalence rate for JIA is 132 per 100,00038. Conversely, annual incidence rates for JIA range from 16 to 113 per 100,000 depending on the country and underlying population. Prevalence rates for rheumatoid factor (RF)-positive polyarticular JIA among American Indian/First Nations youth may be particularly high, but studies are scarce11, 39, 40. In the large US multi-center CARRA Registry, approximately 93% of youth diagnosed with JIA (N=4682) identified as white, and 11% as Hispanic ethnicity; only 5% identified as Black and 3% as Asian41.

When stratified by race and ethnicity, a greater percentage of white youth reported oligoarthritis, whereas a higher proportion of African American (16%) and Hispanic (21%) youths were more likely to present with systemic manifestations compared to white (7%) and non-Hispanic (8%) youth41. Furthermore, although rates of polyarthritis were comparable by race/ethnicity, higher proportions of both Black (26%) and Hispanic (23%) youths with JIA were RF-positive compared to 9% of both white and non-Hispanic comparator groups41.

Similar distributions were observed by global region, with the highest frequencies of systemic arthritis reported among traditionally less-developed regions of Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa and the Middle East, ranging from approximately 30% to slightly less than 20% compared to areas of Europe and North America (<10%), with the highest frequencies of RF-positive polyarthritis in Latin America and Southeast Asia42.

Despite similar prevalence rates of polyarticular JIA among white and Black youth, Black youth had 1.9 times greater odds of joint damage41 and persistently greater physician- and patient/caregiver-assessed disease activity and JIA-related pain43 than white counterparts. Social constructs of race/ethnicity and SES are strongly interrelated in the US44, in both of these studies, Black youths were more likely to report indicators of low SES, including annual household income less than $50,000 and reliance on public health insurance. Similarly, children with Medicaid were more likely to present with polyarticular and/or systemic JIA features, as well as present with more active disease and pain than children with private health insurance45.

Increased disease activity and morbidity can result in greater disability and reduced quality of life. Low SES, compared to high SES, has been associated with increased disability and decreased quality of life as measured by higher Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ) scores and worse illness perception45, 46. Similarly, among Egyptian youths with JIA, low SES was also associated with impaired health related quality of life (HRQoL) compared to high SES individuals47. Living on a reservation, rather than American Indian race, was correlated with increased JIA-related disability, supporting the role of SES and place-based factors in race/ethnicity-based health disparities48.

Healthcare Disparities in JIA

Early and aggressive treatment of JIA49–51 has been shown to improve treatment response and outcomes, so responsive access to care and quality treatment is necessary. However, disparities in access to care and treatment among youth with JIA has been largely understudied and instead inferences are often made from adults with rheumatoid arthritis, healthcare practices in other countries, and other pediatric subspecialties52.

In the US, urbanicity is often characterized by greater racial/ethnic heterogeneity, as well as areas of concentrated poverty and economic disadvantage, due to historical practices of segregation53, 54, these pockets of increased socioeconomic disadvantage facilitate physical and socioeconomic barriers to access to quality healthcare. In general, children with public insurance are more likely to be denied a subspecialty appointment and experience severe delays in specialty appointments compared to children with private insurance55. Outside of the U.S., high parental educational attainment56, private insurance57, and shorter distance to travel57, 58 were all associated with earlier access to a rheumatologist for treatment of JIA symptoms.

Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are instrumental in the treatment of JIA, particularly among severe cases. Studies have demonstrated that use of biologic DMARDs early in the disease process can better reduce disease activity and facilitate early disease management compared to conventional treatments51, 59. Whereas disparities in biologic DMARD use has been reported among Black adults with rheumatoid arthritis compared to white counterparts60, these disparities have not been fully elucidated among youth with JIA. Although not designed to examine differences across socio-demographics, studies have reported both higher61 and lower62 biologic DMARD use among Black children.

Disparities in Other Diseases in Pediatric Rheumatology

Outside of cSLE and JIA there is very sparse literature involving other pediatric rheumatologic diseases aimed to help identify health and healthcare disparities. Few studies of juvenile dermatomyositis youth show a continued pattern of Black and Hispanic youth and youth from low-income families faring worse, both with delays in diagnosis, increased length of stay during hospitalization and higher rates of calcinosis63–65. Of concern is the growing literature indicating important health disparities in adult patients with some of these diseases, including ones with high morbidity and mortality such as systemic sclerosis66–70 and sarcoidosis71–74 .

Disparities in Transitional Care

The transition period from pediatric care to adult care is particularly challenged by changes and increased barriers to healthcare access. In certain disease in pediatric rheumatology, such as SLE, the age group in which patients transition is particularly medically vulnerable and plagued by increased mortality and poor outcomes29, 75, 76. Among youth with general chronic disease, young adults who are Black or Hispanic, of lower SES and non-English speakers are less likely to be adequately prepared to transition77.

There are limited studies in rheumatology that investigate racial and ethnic differences during transition. A recent study of a large cohort of privately insured young adults with cSLE found no difference across racial and ethnic groups in a successful transfer, defined as visit with an adult rheumatology/nephrology within 12 months after the last pediatric subspecialist visit78. A smaller study of youth with cSLE found that lower education and white race was associated with gaps in care during transition79.

There is high variability in the transition process across pediatric rheumatology practices despite both pediatric transition guidelines80 and guidelines specific for pediatric rheumatology81, 82. Only 8% of pediatric rheumatologists are very familiar the American Academy of Pediatrics transition policy and less than half report following their department’s own formal transition policy83. Potentially, this variability may be a source of disparities, however this area has yet to be adequately investigated.

Interventions to Eliminate Health & Healthcare Disparities

The development and implementation of effective interventions to mitigate health and healthcare disparities requires an iterative process of identifying, monitoring , and addressing disparities (Fig. 2)84. Interventions to decrease the gaps in health disparities created by inequities in healthcare are multifactorial and target individual, community, and macro-environmental factors related to federal policies and systems85.

Figure 2. Addressing Health Disparities in Pediatric Rheumatologic Diseases.

A proposed iterative framework to address health disparities through evidence-based methods. This is modified form a conceptual framework developed by Rashid et al84.

An example of federal programming that successfully targeted disparities2 is the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (sCHIP), federally-funded medical insurance for low-income children. The initiation sCHIP was associated with an increase in access to medical care for Black and Hispanic children by 10% and 21%, respectively. Following program initiation racial/ethnic disparities in unmet needs (delayed or foregone preventive, acute, specialty, emergency care, and required prescriptions) were eliminated with unmet needs at 19% for all racial/ethnic groups. At minimum, pediatric rheumatologists can work with other healthcare workers, such as nurses and social workers, to secure insurance for patients86.

At an institution and practice level, interventions are aimed to standardize care, improve provider education, and implement practices that affect vulnerable populations. A study of the implementation of an integrated care management program was developed and used in multihospital system in Boston to address social needs in vulnerable adult patients with medically and psychologically complex SLE87. Addressing social determinants of health is an important mechanism of mitigating healthcare disparities and the use of a social needs assessment tools has been proposed as an initial step of promoting health equity88.

In pediatric rheumatology, as is seen widely in medicine, clinicians do not always deliver the recommended care despite multiple guidelines89–92. In a recent study done by Burman et al. the investigators created a pediatric lupus care index (p-LuCI) which includes standard of care assessments or interventions that should be done at specified times93. Care and completion of the p-LuCI after intervention varied based on patient and clinician characteristics. Hispanic ethnicity was associated with higher likelihood of completion, over Black and white patients.

Encouragingly, in an implementation study in JIA toward a treat-to-target approach using a clinical decision support tool by Chang et al. demonstrated overall improvement in clinical Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Scores (cJADAS) and a gap in score improvement between races favored improvement in Black children62. Importantly, though, it did not close the disparity gap in cJADAS scores between Black and white children. It is possible, that prior to the implementation Black patients did not obtain sufficiently aggressive therapy. Standardization of care through tools utilizing and leveraging electronic medical records is a way to diminish the impact of potential implicit or explicit biases a provider may have that lead to disparities in care.

One critical means of increasing access to care is to increase the limited pediatric rheumatology workforce. Because of a dearth in pediatric rheumatologists, many youth must seek care with an adult rheumatologist who is not as highly trained in specific pediatric rheumatic diseases or as familiar with the clinical nuances required to optimally treat this population 94, 95. Furthermore, there is a mismatch of more senior pediatric rheumatologists leaving the workforce than trainees entering. By 2030 there is projected to be a remarkable deficit of 50% in the number of pediatric rheumatologists in the US. The Southeast, South Central and Southwest regions of the US are expected to be most affected96.

With efforts to grow the workforce, an important consideration will be to increase the number of pediatric rheumatologists from underrepresented demographics. Key strategies put forth by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health to address disparities include increase cultural competency of healthcare workers, support initiatives to increase a diverse work force and promote community interventions97.

Little has been reported recently on the demographic make-up of pediatric rheumatologists, but a study from 2000 indicated that 95% of the workforce is white95. The adult workforce, which often services pediatric rheumatology patients, is also highly non-diverse. In a study looking at adult rheumatologists, underrepresented in medicine (URIM) trainees, which include Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Hispanic or Latino, have increased in most internal medicine subspecialties, but not rheumatology, which remains under 12%97.

Discordance in race between clinicians and patients is a risk factor for negative patient-physician interactions and disparate care. One study found that Black SLE patients report more hurried communication and a perception of providers using more difficult words than white patients98. Further investigations on rheumatologists’ implicit biases and the effect on patient treatment and outcomes are needed.

Among key strategies to address healthcare disparities put forth by the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health is the education of healthcare workers toward improved cultural competency97. This includes education about healthcare disparities. Education about healthcare disparities for rheumatology trainees and faculty is highly variable and proposed curriculum to address gaps in knowledge is currently being developed99.

Areas for Future Studies

Historically, one of the challenges in identifying disparities in pediatric rheumatic diseases stems from a body of literature that is largely based on small single-centered studies without a wide enough lens or enough power to detect differences across sociodemographic groups such as race/ethnicity. Over the past decade, investigators have utilized administrative datasets and the CARRA registry, which has led to a deeper understanding of disparities impacting this patient population. However, there are still not enough studies in pediatric rheumatology that have examined even the most basic social determinants of health, such as income-level and poverty100. The continued use of large datasets and registries, such as the CARRA registry, will help advance the field in further identifying disparities in not only the more common pediatric rheumatic diseases, but the rarer diseases, as well. This research will help guide the development of targeted provider- and institution-level interventions and system-level advocacy. Critical to the success of this, will be ensuring that registries are representative of a diverse group of patients and are not unintentionally or systematically excluding hard-to-reach populations.

Indeed, currently there is a distinct gap in the literature regarding many underrepresented populations. In the US literature, Native Americans and American Indian youth are almost entirely absent. Despite this, in the few studies that have specifically investigated Native American youth, they are at higher risk for many rheumatic diseases, including cSLE and polyarticular JIA11. Furthermore, there are populations for which even the prevalence of disease is unknown due to a lack of rheumatologists. This particularly affects the continent of Africa101, 102.

A recent systematic review of the participation of underrepresented patients in research in SLE and Rheumatoid Arthritis found that trust in the patient physician relationship, inclusion/exclusion criteria that make Black and Hispanic ineligible, community engagement have been barriers to inclusive research in rheumatology103. These need to be carefully addressed in research in pediatric rheumatology and are critical to further identify and address disparities.

If intervention studies do not include diverse populations or intentionally exclude groups based on language, resources, acceptability, or other barriers, they have the potential to exacerbate health disparities. Recently, several studies in pediatric rheumatology have implemented technology-based programs and web-based programs for peer support and self-management support. Two studies from the University of Toronto have shown that implementing these tools can lead to important improvements in quality of life and self-management for youth with JIA104, 105. As these interventions are further tested for efficacy, it is critical that testing is specifically designed to be inclusive of participants across demographics, languages, and resources. This is especially important for technology-based interventions. A study by Sun et al., indicates that non-white, rural, low-income and Spanish speaking families in rheumatology were less likely to access electronic patient portals106.If intervention studies do not include diverse populations or are intentionally excluding groups based on language and resources, they have the potential to increase health disparities. Recently, several studies in pediatric rheumatology have implemented technology-based programs and web-based programs for peer support and self-management support. Two studies from the University of Toronto have shown that implementing these tools can lead to important improvements in quality of life and self-management for youth with JIA104, 105. As these interventions are further tested of efficacy, it is critical that testing is specifically designed to inclusive of participants across demographics, languages, and resources. This is especially important for technology-based interventions. A study by Sun et al, indicates that youth from non-white, rural, low-income and Spanish speaking families were less likely to access electronic patient portals106.

Healthcare disparities among LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning and queer) youth in rheumatology needs further investigation. Adolescents reporting minoritized sexual orientation increased from 7.9% in 2009 to 14.3 in 2017107. These youth are at increased risk for substance abuse, mental health disorders, and are 3 times more likely to attempt suicide107, 108. Hence, this is an area that should be included in research into disparities in pediatric rheumatology and sexual orientation and gender identity should be addressed in clinical encounters with adolescents in the pediatric rheumatology clinic.

Summary

Critical health and healthcare disparities related to race/ethnicity, SES, and geography have been identified in the most prevalent pediatric rheumatic diseases. However, significant gaps in knowledge exist regarding health disparities associated with rarer pediatric rheumatologic diseases and within highly underrepresented demographics. Of particular note, is the lack of literature investigating health disparities (or even health outcomes) in Native American/First Nations youth with rheumatic disease. This group is almost entirely absent from research in pediatric rheumatology. Alarmingly, this is a population is subject to some of the worst health disparities in general health and common chronic diseases109 and with particularly high prevalence of pediatric rheumatic disease with high morbidity and disability, such as SLE and polyarticular JIA10, 11.

Important health disparities in Black Americans have been identified and widely recognized over the past several decades in the general U.S. population, resultant from centuries of systemic and systematic racism. Hence, it is no surprise that the most evident health disparities in pediatric rheumatology are in Black youth. In SLE, which is arguably the most studied disease in pediatric rheumatology with regards to health disparities, disparities in mortality—the most critical and most basic indicator of health—have not only persisted in the U.S. but have worsened over time. Currently in the US, SLE ranks 5th in causes of death for Black and Hispanic 10–25-year-old females9. Similarly, Black youth and low SES youth with SLE, JIA, and other rheumatologic disease are more likely to experience greater disease activity and increased morbidity into adulthood.

This highlights the urgent need to address and mitigate health and healthcare disparities within pediatric rheumatology at the familial, individual treatment, institutional, and societal levels. Identification of health disparities is not enough. Very little research in pediatric rheumatology has tackled interventions to promote health equity and close gaps in health disparities. The few studies that have investigated strategies to implement more standardized treatment and examined their impact on health disparities have had limited success in mitigating gaps in health care disparities, let alone gaps in health outcomes. Interventions that specifically target and uplift the care of vulnerable populations may be needed to attain health equity, rather than focusing on provision of equal care. Strategies that address health and healthcare disparities on different levels—including practice level changes, improving trainee education to address implicit bias, implementing equitable representation in pediatric rheumatology literature and research, and passing equity-focused healthcare policy—are crucial to ensuring optimal health and well-being among youth with rheumatic diseases.

Key Points:

Health disparities in pediatric rheumatic diseases are prevalent across racial/ethnic groups, socioeconomic groups and geographic areas.

While health disparities in youth with SLE and JIA have been identified, significant gaps in knowledge on disparities in other childhood rheumatologic diseases exist.

Standardizing care is a strategy to decrease disparities but improved understanding of healthcare disparities in this population is necessary to develop appropriate interventions to decrease healthcare inequity in pediatric rheumatology.

Synopsis.

Health and healthcare disparities in pediatric rheumatology are prevalent across racial/ethnic groups, socioeconomic groups, and geographic areas from a socially disadvantaged backgrounds affecting, access to care, disease severity, morbidity, mortality, quality of life and mental health. There is literature on JIA and SLE with significant gaps in studies looking at health and healthcare disparities of other pediatric rheumatic diseases. Understanding of why healthcare disparities exist will ultimately inform the innovation and implementation of policies and interventions on a federal, local, and individual levels.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Footnotes

Disclosure: the authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Oberg C, Colianni S, King-Schultz L. Child Health Disparities in the 21st Century. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. Sep 2016;46(9):291–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Services UDoHaH. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. 2010. Phase I report: Recommendations for the framework and format of healthy people 2020. Accessed 1/25/2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/PhaseI_0.pdf

- 3.Braveman PA, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, et al. Health disparities and health equity: the issue is justice. Am J Public Health. Dec 2011;101 Suppl 1:S149–55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brofenbrenner U Ecological models of human development. International encyclopedia of education. 1994;3(2):1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reifsnider E, Gallagher M, Forgione B. Using Ecological Models in Research on Health Disparities. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2005/07/01/ 2005;21(4):216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Reports. 2014;129(1_suppl2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291s206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knight AM, Weiss PF, Morales KH, Keren R. National trends in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus hospitalization in the United States: 2000–2009. J Rheumatol. Mar 2014;41(3):539–46. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker LB, Uribe AG, Fernández M, et al. Adolescent onset of lupus results in more aggressive disease and worse outcomes: Results of a nested matched case-control study within LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LVII). Article. Lupus. 2008;17(4):314–322. doi: 10.1177/0961203307087875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yen EY, Singh RR. Brief Report: Lupus—An Unrecognized Leading Cause of Death in Young Females: A Population-Based Study Using Nationwide Death Certificates, 2000–2015. Article. Arthritis and Rheumatology. 2018;70(8):1251–1255. doi: 10.1002/art.40512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiraki LT, Feldman CH, Liu J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and demographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis from 2000 to 2004 among children in the US Medicaid beneficiary population. Arthritis Rheum. Aug 2012;64(8):2669–76. doi: 10.1002/art.34472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauldin J, Cameron HD, Jeanotte D, Solomon G, Jarvis JN. Chronic arthritis in children and adolescents in two Indian health service user populations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. Aug 27 2004;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houghton KM, Page J, Cabral DA, Petty RE, Tucker LB. Systemic lupus erythematosus in the pediatric North American Native population of British Columbia. J Rheumatol. Jan 2006;33(1):161–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Concannon A, Rudge S, Yan J, Reed P. The incidence, diagnostic clinical manifestations and severity of juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus in New Zealand Maori and Pacific Island children: the Starship experience (2000–2010). Lupus. Oct 2013;22(11):1156–61. doi: 10.1177/0961203313503051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackie F, Kainer G, Rosenberg A, et al. High rates of SLE (systemic lupus erythematosus) in indigenous children in Australia - An interim report of the Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit Study (APSU) 2009–2010. Conference Abstract. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2011;47:9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02117.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reveille JD, Moulds JM, Ahn C, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: I. The effects of HLA class II, C4, and CR1 alleles, socioeconomic factors, and ethnicity at disease onset. LUMINA Study Group. Lupus in minority populations, nature versus nurture. Arthritis Rheum. Jul 1998;41(7):1161–72. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alarcón GS, Rodríguez JL, Benavides G, Brooks K, Kurusz H, Reveille JD. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: V. Acculturation, health-related attitudes and behaviors, and disease activity in Hispanic patients from the LUMINA Cohort. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1999;12(4):267–276. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgos PI, McGwin G, Pons-Estel GJ, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS, Vila LM. US patients of Hispanic and African ancestry develop lupus nephritis early in the disease course: data from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LXXIV). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2011;70(2):393–394. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.131482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uribe AG, Alarcón GS, Sanchez ML, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XVIII. Factors predictive of poor compliance with study visits. Arthritis Care & Research. 2004;51(2):258–263. doi: 10.1002/art.20226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alarcón GS, McGwin JG, Bastian HM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. VIII. Predictors of early mortality in the LUMINA cohort. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2001;45(2):191–202. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bastian HM, Alarcon GS, Roseman JM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA) XL II: factors predictive of new or worsening proteinuria. Rheumatology. 2006;46(4):683–689. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alarcon GS. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic cohort: LUMINA XXXV. Predictive factors of high disease activity over time. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2006;65(9):1168–1174. doi: 10.1136/ard.200x.046896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández M, Alarcón GS, Calvo-Alén J, et al. A multiethnic, multicenter cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as a model for the study of ethnic disparities in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. May 15 2007;57(4):576–84. doi: 10.1002/art.22672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiraki LT, Benseler SM, Tyrrell PN, Harvey E, Hebert D, Silverman ED. Ethnic Differences in Pediatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. The Journal of Rheumatology. Nov 2009;36(11):2539–2546. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang JC, Xiao R, Mercer-Rosa L, Knight AM, Weiss PF. Child-onset systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with a higher incidence of myopericardial manifestations compared to adult-onset disease. Lupus. 2018;27(13):2146–2154. doi: 10.1177/0961203318804889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrison MJ, Zühlke LJ, Lewandowski LB, Scott C. Pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus patients in South Africa have high prevalence and severity of cardiac and vascular manifestations. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. Nov 26 2019;17(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12969-019-0382-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tucker L, Uribe A, Fernández M, et al. Adolescent onset of lupus results in more aggressive disease and worse outcomes: results of a nested matched case–control study within LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LVII). Lupus. 2008;17(4):314–322. doi: 10.1177/0961203307087875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bundhun PK, Kumari A, Huang F. Differences in clinical features observed between childhood-onset versus adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). Sep 2017;96(37):e8086. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000008086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewandowski LB, Watt MH, Schanberg LE, Thielman NM, Scott C. Missed opportunities for timely diagnosis of pediatric lupus in South Africa: a qualitative study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. Feb 23 2017;15(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12969-017-0144-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Q, Liang M, Duan J, Zhang L, Kawachi I, Lu TH. Age differences in secular trends in black-white disparities in mortality from systemic lupus erythematosus among women in the United States from 1988 to 2017. Lupus. Feb 3 2021:961203321988936. doi: 10.1177/0961203321988936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubinstein TB, Mowrey WB, Ilowite NT, Wahezi DM. Delays to Care in Pediatric Lupus Patients: Data From the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Legacy Registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Mar 2018;70(3):420–427. doi: 10.1002/acr.23285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubinstein T, Davis A, Rodriguez M, Knight A. Addressing Mental Health In Pediatric Rheumatology. Current Treatment Options in Rheumatology. 2018;4(1):55–72. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knight A, Weiss P, Morales K, et al. Depression and anxiety and their association with healthcare utilization in pediatric lupus and mixed connective tissue disease patients: a cross-sectional study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12:42. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knight AM, Xie M, Mandell DS. Disparities in Psychiatric Diagnosis and Treatment for Youth with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Analysis of a National US Medicaid Sample. J Rheumatol. Jul 2016;43(7):1427–33. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis AM, Graham TB, Zhu Y, McPheeters ML. Depression and medication nonadherence in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. Aug 2018;27(9):1532–1541. doi: 10.1177/0961203318779710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang JC, Davis AM, Klein-Gitelman MS, Cidav Z, Mandell DS, Knight AM. Impact of Psychiatric Diagnosis and Treatment on Medication Adherence in Youth With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Jan 2021;73(1):30–38. doi: 10.1002/acr.24450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moorthy LN, Peterson MG, Hassett AL, Lehman TJ. Burden of childhood-onset arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. Jul 8 2010;8:20. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-8-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. Feb 2004;31(2):390–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oen KG, Cheang M. Epidemiology of chronic arthritis in childhood. Semin Arthritis Rheum. Dec 1996;26(3):575–91. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(96)80009-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saurenmann RK, Rose JB, Tyrrell P, et al. Epidemiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a multiethnic cohort: ethnicity as a risk factor. Arthritis Rheum. Jun 2007;56(6):1974–84. doi: 10.1002/art.22709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg AM, Petty RE, Oen KG, Schroeder ML. Rheumatic diseases in Western Canadian Indian children. J Rheumatol. Jul-Aug 1982;9(4):589–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ringold S, Beukelman T, Nigrovic PA, Kimura Y, Investigators CRSP. Race, ethnicity, and disease outcomes in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Registry. J Rheumatol. Jun 2013;40(6):936–42. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Consolaro A, Giancane G, Alongi A, et al. Phenotypic variability and disparities in treatment and outcomes of childhood arthritis throughout the world: an observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. Apr 2019;3(4):255–263. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang JC, Xiao R, Burnham JM, Weiss PF. Longitudinal assessment of racial disparities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis disease activity in a treat-to-target intervention. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. Nov 13 2020;18(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12969-020-00485-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. Apr 2016;35(4):407–11. doi: 10.1037/hea0000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunner HI, Taylor J, Britto MT, et al. Differences in disease outcomes between medicaid and privately insured children: possible health disparities in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. Jun 15 2006;55(3):378–84. doi: 10.1002/art.21991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verstappen SM, Cobb J, Foster HE, et al. The association between low socioeconomic status with high physical limitations and low illness self-perception in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the Childhood Arthritis Prospective Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Mar 2015;67(3):382–9. doi: 10.1002/acr.22466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdul-Sattar AB, Elewa EA, El-Shahawy Eel D, Waly EH. Determinants of health-related quality of life impairment in Egyptian children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Sharkia Governorate. Rheumatol Int. Aug 2014;34(8):1095–101. doi: 10.1007/s00296-014-2950-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oen K, Malleson PN, Cabral DA, et al. Early predictors of longterm outcome in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: subset-specific correlations. J Rheumatol. Mar 2003;30(3):585–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Albers HM, Wessels JAM, Van Der Straaten RJHM, et al. Time to treatment as an important factor for the response to methotrexate in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2008;61(1):46–51. doi: 10.1002/art.24087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foster HE, Eltringham MS, Kay LJ, Friswell M, Abinun M, Myers A. Delay in access to appropriate care for children presenting with musculoskeletal symptoms and ultimately diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. Aug 15 2007;57(6):921–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang B, Qiu T, Chen C, et al. Timing matters: real-world effectiveness of early combination of biologic and conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for treating newly diagnosed polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis. RMD Open. Jan 2020;6(1)doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tesher MS, Onel KB. The clinical spectrum of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a large urban population. Curr Rheumatol Rep. Apr 2012;14(2):116–20. doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0237-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Massey DS, Tannen J. Suburbanization and Segregation in the United States: 1970–2010. Ethn Racial Stud. 2018;41(9):1594–1611. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1312010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parker K, Horowitz J, Brown A, Fry R, Cohn D, Igielnik R. What Unites and Divides Urban, Suburban and Rural Communities. 2018. May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. N Engl J Med. Jun 16 2011;364(24):2324–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1013285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shiff NJ, Tucker LB, Guzman J, Oen K, Yeung RS, Duffy CM. Factors associated with a longer time to access pediatric rheumatologists in Canadian children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. Nov 2010;37(11):2415–21. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agarwal M, Freychet C, Jain S, et al. Factors impacting referral of JIA patients to a tertiary level pediatric rheumatology center in North India: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2020;18(1)doi: 10.1186/s12969-020-0408-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tzaribachev N, Benseler SM, Tyrrell PN, Meyer A, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB. Predictors of delayed referral to a pediatric rheumatology center. Arthritis Rheum. Oct 15 2009;61(10):1367–72. doi: 10.1002/art.24671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tynjala P, Vahasalo P, Tarkiainen M, et al. Aggressive combination drug therapy in very early polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ACUTE-JIA): a multicentre randomised open-label clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. Sep 2011;70(9):1605–12. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.143347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suarez-Almazor ME, Berrios-Rivera JP, Cox V, Janssen NM, Marcus DM, Sessoms S. Initiation of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy in minority and disadvantaged patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. Dec 2007;34(12):2400–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ringold S, Beukelman T, Nigrovic PA, Kimura Y. Race, ethnicity, and disease outcomes in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Registry. J Rheumatol. Jun 2013;40(6):936–42. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang JC, Xiao R, Burnham JM, Weiss PF. Longitudinal assessment of racial disparities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis disease activity in a treat-to-target intervention. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2020;18(1)doi: 10.1186/s12969-020-00485-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Phillippi K, Hoeltzel M, Byun Robinson A, Kim S. Race, Income, and Disease Outcomes in Juvenile Dermatomyositis. J Pediatr. May 2017;184:38–44.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kwa MC, Silverberg JI, Ardalan K. Inpatient burden of juvenile dermatomyositis among children in the United States. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2018;16(1)doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0286-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pachman LM, Hayford JR, Chung A, et al. Juvenile dermatomyositis at diagnosis: clinical characteristics of 79 children. J Rheumatol. Jun 1998;25(6):1198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steen V, Domsic RT, Lucas M, Fertig N, Medsger TA. A clinical and serologic comparison of African American and Caucasian patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2012;64(9):2986–2994. doi: 10.1002/art.34482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chung MP, Dontsi M, Postlethwaite D, et al. Increased Mortality in Asians With Systemic Sclerosis in Northern California. ACR Open Rheumatology. 2020;2(4):197–206. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Beebe-Dimmer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in a large US population. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;48(8):2246–2255. doi: 10.1002/art.11073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gelber AC, Manno RL, Shah AA, et al. Race and association with disease manifestations and mortality in scleroderma: a 20-year experience at the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). Jul 2013;92(4):191–205. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31829be125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blanco I, Mathai S, Shafiq M, et al. Severity of systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in African Americans. Medicine (Baltimore). Jul 2014;93(5):177–185. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000000032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis Based on Health Care Use. Ann Am Thorac Soc. Aug 2016;13(8):1244–52. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-760OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hena KM. Sarcoidosis Epidemiology: Race Matters. Front Immunol. 2020;11:537382. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.537382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Westney GE, Judson MA. Racial and ethnic disparities in sarcoidosis: from genetics to socioeconomics. Clin Chest Med. Sep 2006;27(3):453–62, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ogundipe F, Mehari A, Gillum R. Disparities in Sarcoidosis Mortality by Region, Urbanization, and Race in the United States: A Multiple Cause of Death Analysis. Am J Med. Sep 2019;132(9):1062–1068.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Felsenstein S, Reiff AO, Ramanathan A. Transition of Care and Health-Related Outcomes in Pediatric-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Nov 2015;67(11):1521–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.22611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tucker LB, Uribe AG, Fernández M, et al. Adolescent onset of lupus results in more aggressive disease and worse outcomes: results of a nested matched case-control study within LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LVII). Lupus. Apr 2008;17(4):314–22. doi: 10.1177/0961203307087875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McManus MA, Pollack LR, Cooley WC, et al. Current status of transition preparation among youth with special needs in the United States. Pediatrics. Jun 2013;131(6):1090–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chang JC, Knight AM, Lawson EF. Patterns of Healthcare Use and Medication Adherence among Youth with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus during Transfer from Pediatric to Adult Care. J Rheumatol. Jan 1 2021;48(1):105–113. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.191029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Son MB, Sergeyenko Y, Guan H, Costenbader K. Disease activity and transition outcomes in a childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus cohort. Lupus. 2016;25(13):1431–1439. doi: 10.1177/0961203316640913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. Dec 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1304–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Calvo I, Antón J, Bustabad S, et al. Consensus of the Spanish society of pediatric rheumatology for transition management from pediatric to adult care in rheumatic patients with childhood onset. Rheumatol Int. Oct 2015;35(10):1615–24. doi: 10.1007/s00296-015-3273-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Foster HE, Minden K, Clemente D, et al. EULAR/PReS standards and recommendations for the transitional care of young people with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. Apr 2017;76(4):639–646. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chira P, Ronis T, Ardoin S, White P. Transitioning youth with rheumatic conditions: perspectives of pediatric rheumatology providers in the United States and Canada. J Rheumatol. Apr 2014;41(4):768–79. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rashid JR, Spengler RF, Wagner RM, et al. Eliminating Health Disparities Through Transdisciplinary Research, Cross-Agency Collaboration, and Public Participation. American Journal of Public Health. Nov 2009;99(11):1955–1961. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.167932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wasserman J, Palmer RC, Gomez MM, Berzon R, Ibrahim SA, Ayanian JZ. Advancing Health Services Research to Eliminate Health Care Disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S64–S69. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2018.304922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shone LP. Reduction in Racial and Ethnic Disparities After Enrollment in the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. PEDIATRICS. 2005;115(6):e697–e705. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Taber K, Williams J, Huang W, et al. Use of an Integrated Care Management Program to Uncover and Address Social Determinants of Health for Individuals with Lupus. 2020: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bourgois P, Holmes SM, Sue K, Quesada J. Structural Vulnerability: Operationalizing the Concept to Address Health Disparities in Clinical Care. Acad Med. Mar 2017;92(3):299–307. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000001294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Groot N, De Graeff N, Avcin T, et al. European evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: the SHARE initiative. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2017;76(11):1788–1796. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ringold S, Weiss PF, Colbert RA, et al. Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance consensus treatment plans for new-onset polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Jul 2014;66(7):1063–72. doi: 10.1002/acr.22259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mina R, Von Scheven E, Ardoin SP, et al. Consensus treatment plans for induction therapy of newly diagnosed proliferative lupus nephritis in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care & Research. 2012;64(3):375–383. doi: 10.1002/acr.21558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Otten MH, Anink J, Prince FH, et al. Trends in prescription of biological agents and outcomes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of the Dutch national Arthritis and Biologics in Children Register. Ann Rheum Dis. Jul 2015;74(7):1379–86. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Burnham JM, Peterson R, Ukaigwe J, Cecere L, Knight A, Chang JC. Determinants of Variation in Pediatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Care Delivery. 2020: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Correll CK, Spector LG, Zhang L, Binstadt BA, Vehe RK. Barriers and alternatives to pediatric rheumatology referrals: survey of general pediatricians in the United States. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. Jul 29 2015;13:32. doi: 10.1186/s12969-015-0028-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mayer ML, Sandborg CI, Mellins ED. Role of pediatric and internist rheumatologists in treating children with rheumatic diseases. Pediatrics. Mar 2004;113(3 Pt 1):e173–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Correll CK, Ditmyer MM, Mehta J, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Workforce Study and Demand Projections of Pediatric Rheumatology Workforce, 2015‐2030. Arthritis Care & Research. 2020;doi: 10.1002/acr.24497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jackson CS, Gracia JN. Addressing Health and Health-Care Disparities: The Role of a Diverse Workforce and the Social Determinants of Health. Public Health Reports. 2014;129(1_suppl2):57–61. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291s211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sun K, Eudy AM, Criscione-Schreiber LG, et al. Racial differences in patient-provider communication, patient self-efficacy, and their associations with lupus-related damage: a cross-sectional survey. J Rheumatol. Sep 1 2020;doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Blanco I, Barjaktarovic N, Gonzalez CM. Addressing Health Disparities in Medical Education and Clinical Practice. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. Feb 2020;46(1):179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2019.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rubinstein TB, Knight AM. Disparities in Childhood-Onset Lupus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. Nov 2020;46(4):661–672. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Henrickson M Policy challenges for the pediatric rheumatology workforce: Part III. the international situation. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2011;9(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-9-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sandhu VK, Hojjati M, Blanco I. Healthcare disparities in rheumatology: the role of education at a global level. Clin Rheumatol. Mar 2020;39(3):659–666. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04777-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lima K, Phillip CR, Williams J, Peterson J, Feldman CH, Ramsey-Goldman R. Factors Associated With Participation in Rheumatic Disease-Related Research Among Underrepresented Populations: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Oct 2020;72(10):1481–1489. doi: 10.1002/acr.24036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stinson J, Ahola Kohut S, Forgeron P, et al. The iPeer2Peer Program: a pilot randomized controlled trial in adolescents with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2016;14(1)doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0108-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stinson JN, Lalloo C, Hundert AS, et al. Teens Taking Charge: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Web-Based Self-Management Program With Telephone Support for Adolescents With Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(7):e16234. doi: 10.2196/16234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sun EY, Alvarez C, Callahan LF, Sheikh SZ. Disparities in Patient Portal Use Among Patients with Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases in a Large Academic Medical Center. 2020: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Raifman J, Charlton BM, Arrington-Sanders R, et al. Sexual Orientation and Suicide Attempt Disparities Among US Adolescents: 2009–2017. Pediatrics. 2020;145(3):e20191658. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fish JN, Baams L. Trends in Alcohol-Related Disparities Between Heterosexual and Sexual Minority Youth from 2007 to 2015: Findings from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. LGBT Health. Aug/Sep 2018;5(6):359–367. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sarche M, Spicer P. Poverty and health disparities for American Indian and Alaska Native children: current knowledge and future prospects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:126–36. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]