Abstract

Background

Remnant cholesterol (RC) has been implicated in cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in populations of European ancestry, yet its causal role remains underexplored in populations of East Asian ancestry, which are underrepresented in genetic studies. We sought to investigate the causal association between circulating RC levels and CVD risk in East Asian populations.

Methods

We first conducted observational analyses of RC and multiple CVD outcomes in Chinese populations. We then conducted genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of RC in 14,939 Chinese individuals and assessed its causal associations with CVD risk using two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) with Biobank Japan data. Replication analyses in European ancestry populations utilized summary statistics from the UK Biobank and FinnGen.

Results

Circulating RC levels were significantly associated with multiple CVD outcomes in Chinese individuals. Our GWAS identified seven significant loci associated with circulating RC levels in the Chinese population. In the MR analyses, we found that genetically predicted higher RC levels were significantly associated with increased risks of aortic aneurysm (odds ratio per standard deviation increase, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.53–2.17; P = 1.17 × 10−11) and ischemic heart diseases, such as myocardial infarction (1.22, 1.13–1.32; P = 1.81 × 10−7) and stable angina pectoris (1.17, 1.11–1.23; P = 1.18 × 10−8). Notably, these associations persisted after adjustment for total cholesterol, low-density and high-density lipoprotein cholesterols, Apolipoprotein A1 and Apolipoprotein B, respectively. Replication in European ancestry populations confirmed consistent causal effects for aortic aneurysm and ischemic heart diseases. A suggestive East Asian-specific association was identified between genetically predicted higher RC levels and an increased risk of peripheral artery disease, whereas a suggestive association with a higher risk of atrial flutter/fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmia was only observed in populations of European ancestry.

Conclusions

Our findings establish RC as an independent causal CVD risk factor in East Asian ancestry individuals and highlight population-specific differences in CVD risk profiles, emphasizing the need for ethnicity-tailored prevention strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04329-y.

Keywords: Remnant cholesterol, Cardiovascular diseases, Genome-wide association study, Mendelian randomization

Background

The cardiovascular impact of circulating lipids is complex and remains a debate[1]. While elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) is well-established as a causal cardiovascular risk factor through both genetic studies and successful LDL-c-lowering therapies [2, 3], the protective role of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) has been challenged by inconclusive results from interventional trials [4, 5]. On the other hand, despite the widespread use of LDL-c-lowering treatments, such as statins, a significant residual cardiovascular risk persists among the treated individuals [6, 7]. Remnant cholesterol (RC), which primarily refers to the content of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (e.g., chylomicrons, very-low-density lipoproteins [VLDL], and intermediate-density lipoproteins [IDL]), has emerged as an independent and important contributor to the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) beyond LDL-c and HDL-c [8, 9]. Emerging studies have demonstrated that higher RC levels are associated with an increased risk of CVD, even in the context of optimal LDL-c levels [10–12].

The effects of lipids on CVD risk are further modulated by metabolic conditions, genetic predispositions, and population-specific factors, complicating the understanding of direct causality [13–15]. Recently, genetically predicted RC levels have been associated with CVD risk in populations of European ancestry [16–18], while evidence in population of East Asian ancestry remains limited. East Asian ancestry individuals exhibit distinct lipid profiles, a rising burden of metabolic disorders, and genetic differences compared to population of European ancestry, underscoring the need for targeted investigations to understand the causal role of RC in this group.

In this study, we performed a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of RC in Chinese populations and employed two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) to examine the potential causal association between RC and CVD in East Asian ancestry individuals, integrating the summary statistics from the Biobank Japan [19]. Furthermore, we compared the causal effects of RC on CVD between populations of East Asian ancestry and European ancestry using GWAS summary statistics from the UK Biobank and FinnGen [20]. We also carried out an observational study in a Chinese population to further validate our findings. Our findings may provide novel insights into the population-specific role of RC in CVD risk, with implications for prevention and therapeutic strategies.

Methods

Study participants

The present study included 14,939 Han Chinese from four populations: the Shanghai Changfeng Study [21–23], the Rugao Longevity and Aging Study [24], the National Survey of Physical Traits cohort [25] and the Genetic characteristics of coRonary Artery disease in ChiNese young aDults study (GRAND) [26, 27]. Details of the participants’ characteristics and genotyping methodologies are provided in Additional file 1: Table S1. Notably, among the four Chinese populations, participants were instructed to fast overnight prior to blood sample collection the following morning. For each population, written informed consent was obtained from all participants before being enrolled, and the studies were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions.

For the European study, we included approximately 280,000 individuals from the UK Biobank with genotyping data and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based metabolomic data [28, 29]. The blood samples were collected during the participants’ visit to the assessment center, and the duration of fasting prior to blood draw was recorded. Following the central quality control procedures of the UK Biobank [28], we excluded: (1) individuals who had withdrawn consent, (2) non-Caucasian participants, (3) those with sex chromosome aneuploidy, (4) those with a mismatch between genetically inferred sex and self-reported sex, and (5) outliers for heterozygosity or missing rate. Ultimately, 213,397 participants were included in the present analyses.

Measurement of circulating remnant cholesterol levels

In this study, the levels of RC in each Chinese population were directly measured using the same NMR-based metabolomics platform. Briefly, blood metabolomics profiling was performed on a 600 MHz AVANCE III NMR spectrometer (Bruker Biospin GmbH, Germany), following previously established protocols (Additional file 2: Supplementary Method) [22, 30, 31]. For European ancestry participants from the UK Biobank, metabolites in EDTA plasma samples were measured using Nightingale Health’s high-throughput NMR-based platform [29]. Notably, to account for the effects of lipid-lowering medications, we corrected LDL-c and total cholesterol (TC) levels in statin users by dividing LDL-c by 0.70 and TC by 0.80, and subsequently recalculated RC levels [32]. The RC levels were then normalized using rank-based inverse normal transformation and analyzed in the observational studies and GWAS.

Observational study of remnant cholesterol and coronary artery disease severity in GRAND study

We investigated the association between RC levels and coronary artery disease (CAD) and CAD severity in the GRAND cohort. This study included 3779 participants who underwent coronary angiography with physician-confirmed CAD diagnoses and subtype classification. 2296 participants were diagnosed with CAD, among whom 2289 and 2277 underwent Gensini score assessment and circulating cardiac troponin T (cTnT) level measurement, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S2). Serum cTnT was measured using venous blood samples that were obtained at admission and by an automated analyzer using a high-sensitivity assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Gensini score was used to quantify atherosclerotic burden by evaluating both the degree of luminal narrowing and lesion location (with higher scores indicating more severe proximal lesions) through a standardized scoring system that sums segmental scores for individual coronary stenoses. We obtained self-reported data on age, sex, height, weight, smoking status, and alcohol consumption through electronic medical records, along with information on the use of glucose-lowering medications, antihypertensive drugs, and lipid-lowering agents. The diagnosis of hypertension and type 2 diabetes was determined through electronic medical records and physician assessments. Body mass index (BMI) was computed by dividing the weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters). Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) of RC levels and CAD and its subtype classification. Linear regression models were used to evaluate the estimate β (logOR) with 95% CI between RC levels and CAD severity.

To further investigate the association between RC levels and CAD prognosis in the Chinese population, we conducted a three-year longitudinal study involving 1,990 CAD patients from the GRAND cohort (Additional file 1: Table S3). The baseline coronary atherosclerotic burden was quantified using the Gensini score. Clinical follow-ups were conducted through either clinic visits or telephone interviews to document the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) during the 3-year follow-up period. MACE was defined as cardiovascular death, unplanned revascularization, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and stroke. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs of the baseline RC levels with the risk of MACE.

Genome-wide association studies for remnant cholesterol

A GWAS for RC was conducted in each Chinese population using a linear mixed model implemented in BOLT-LMM software (2.4.1) [33] (Fig. 1). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were excluded from the analyses if they failed to meet the following criteria: deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE, P < 10−5), minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1%, or low imputation quality (INFO < 0.4). The analysis was adjusted for age, sex, and the top five genetic ancestry principal components. Results from each population were meta-analyzed using a fixed-effect model based on effect sizes and standard errors in METAL software [34].

Fig. 1.

The analysis workflow of the study

Due to the larger sample size and more stringent imputation strategy employed in the UK Biobank (e.g., multiple imputation reference panels) [28], variants with INFO > 0.8 were retained. Other quality control thresholds, including HWE > 10−5 and MAF > 1%, were applied consistently across both the Chinese and UK Biobank cohorts. GWAS was performed using PLINK (2.0) software [35], with adjustments of age, sex, fasting time, genotyping chips, assessment centers, metabolomic profiling batch, use of lipid-lowering medications, and the top ten genetic ancestry principal components.

Data sources for cardiovascular diseases

Genetic variants associated with CVDs in East Asian ancestry individuals were obtained from BioBank Japan (Additional file 1: Table S4) [19]. Briefly, GWASs were conducted in over 179,000 Japanese individuals using a generalized linear mixed model in SAIGE (v.0.37), with adjustment of age, age2, sex, age × sex, age2 × sex, and the top 20 principal components [19]. Based on ICD-10 codes, we selected circulatory system diseases (I00-I99) with a prevalence greater than 0.5% (hum0197.v3). This resulted in 13 cardiovascular outcomes, including aortic aneurysm, peripheral arterial disease, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, stable angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris, cerebral aneurysm, intracerebral hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, chronic heart failure, atrial flutter/fibrillation, and ventricular arrhythmia (Additional file 1: Table S4).

For replication, we matched these 13 cardiovascular outcomes with 12 diseases from the latest release of the FinnGen database (DF12, Additional file 1: Table S4) [20]. GWASs for these disease traits in FinnGen were performed in over 453,000 Finnish biobank participants using regenie (v.2.2.4), with adjustment of age, sex, top 10 principal components, and genotyping batch as covariates [20]. Further details on the data sources are provided in Additional file 1: Table S4.

Instrumental variables selection

To ensure the validity of instrumental variables (IVs), three fundamental assumptions must be met: (1) the IV must be strongly associated with the exposure of interest, (2) the IV must be independent of any confounders affecting the relationship between the exposure and the outcome, and (3) the IV should affect the outcome exclusively through the exposure pathway [36]. In this study, SNPs significantly associated with RC at the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10−8) were selected as candidate IVs. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was assessed between SNPs to select independent genetic variants using PLINK (1.9) software (window size = 10,000 kb, R2 < 0.1 for East Asians, with the 1000 Genome Project Phase 3 v5 East Asian population as the reference panel) [35]. For SNPs in LD, we selected the variant with the lowest P-value. The strength of each IV was evaluated by calculating the F statistic, and SNPs with an F statistic < 10 were excluded [37].

Two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis in East Asian ancestry individuals

Before each MR analysis, the selected IVs were harmonized across exposure and outcome summary statistics to ensure that the effects of SNPs corresponded to the same allele. Palindromic SNPs with intermediate allele frequencies (MAF > 0.42) were excluded (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Importantly, there was no overlap between the samples used for the exposure and outcome GWAS.

For the main analysis, we used the fixed-effect inverse variance weighted (IVW) method to estimate the causal effect of exposure on the outcome. This method assumes no (unbalanced) horizontal pleiotropy. Given that pleiotropic bias could potentially violate this assumption, we conducted sensitivity analyses using the weighted median method, MR-Egger method, and MR-PRESSO method to assess the robustness and reliability of the findings [38]. A causal association was considered robust when all sensitivity analysis methods yielded results that were consistent with the effect direction estimated by the IVW method.

The results are presented as OR (95% CI), reflecting the assessed CVD risk associated with one standard deviation (SD) increase in genetically predicted circulating levels of RC. Directional pleiotropy was tested using the hypothesis test for the MR-Egger regression’s intercept, and heterogeneity was assessed via Cochran’s Q-test. If heterogeneity was detected, a multiplicative random-effects IVW method was applied [38]. Furthermore, leave-one-out analyses were performed to evaluate whether the observed effects were driven by any single SNP.

To address the multiple testing issues, we applied a threshold of statistical significance at P < 0.0038 (0.05/13 cardiovascular outcomes) using Bonferroni correction. Results with 0.0038 ≤ P < 0.05 were considered suggestive associations. All MR analyses were performed using R software (4.2.2) with the TwoSampleMR (0.5.7) and MRPRESSO (1.0) packages. This study adhered to the guidelines for strengthening the reporting of observational studies in Epidemiology using Mendelian randomization studies (STROBE-MR; Additional file 3) [39, 40].

Multivariable Mendelian randomization analysis

To control for potential confounding effects from other lipid traits, including LDL-c, TC, HDL-c, Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), and Apolipoprotein B (ApoB), we conducted multivariable Mendelian randomization (MVMR) to estimate the independent causal effect of RC on each CVD outcome (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Because the inclusion of highly correlated exposures can reduce statistical power, weaken instrument strength, and introduce model instability [41], we designed three biologically informed models based on the distinct roles of cholesterol-carrying lipoproteins and apolipoproteins. In Model 1, we adjusted for TC alone, as it represents total circulating cholesterol. In Model 2, we decomposed TC into its components—LDL-c, HDL-c, and RC—to investigate whether RC is independently associated with CVD beyond other cholesterol fractions. In Model 3, we adjusted for ApoB and ApoA1, the main structural proteins of LDL-c/VLDL-c and HDL-c, respectively. Notably, ApoB has recently been reported as an independent CVD risk factor beyond LDL-c [42]. This modeling approach allowed us to account for the biological relevance of each lipid trait while minimizing multicollinearity (e.g., between ApoB and LDL-c), which could otherwise lead to unstable estimates.

The IVW method was used as the primary MVMR approach. As a sensitivity analysis, the MR-Egger method was also applied. The joint instrument strength for the exposures in the MVMR analysis was evaluated using the Sanderson–Windmeijer conditional F statistic [43]. IVs with a conditional F statistic below 10 were considered weak. The P < 0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant, indicating strong evidence for a causal association. All MVMR analyses were performed using the R packages TwoSampleMR (0.5.7), MVMR (0.4), and MendelianRandomization (0.9.0).

Replication analysis in population of European ancestry

To assess the generalizability and robustness of our results, we replicated the two-sample MR and MVMR analyses within populations of European ancestry using data from the UK Biobank and FinnGen databases (Additional file 1: Table S4). Briefly, SNPs significantly associated with RC (P < 5 × 10−8) were selected as IVs for the MR analysis. For the selected SNPs, LD was examined to ensure independence (R2 < 0.001 within a 10,000 kb window for European ancestry, justifying the larger sample size for Europeans). The remaining procedures were consistent with those described in East Asian ancestry individuals.

Reverse Mendelian randomization analysis

To estimate the causal effects of genetically predicted CVD risks on the RC level, we further performed reverse MR analyses. For each CVD, we included SNPs that reached the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10−8; or P < 1 × 10−5 if there were not enough SNPs) as candidates for IVs. Independent SNPs with an LD r2 < 0.001 and an F statistic > 10 were retained. The specific MR methods were consistent with those described above. Statistical significance was defined using the same threshold as in the forward MR, with a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of P < 0.0038 (0.05/13 CVDs).

Results

Remnant cholesterol as a biomarker of coronary artery diseases in Chinese population

We conducted an observational study in the GRAND cohort to investigate the association between RC levels and CAD-related outcomes. Of the 3779 individuals included in GRAND, 2296 had CAD, comprising 453 with myocardial infarction, 815 with stable angina, and 967 with unstable angina (Additional file 1: Table S2). In univariable logistic regression analyses, higher RC levels were significantly associated with increased odds of all five CAD subtypes (Table 1). After multivariable adjustment, higher RC levels remained independently associated with increased odds of myocardial infarction (adjusted OR [95%CI], 1.352 [1.176, 1.556]; P = 2.45 × 10−5), unstable angina (1.130 [1.027, 1.244], P = 0.013), angina pectoris (1.115 [1.027, 1.210], P = 9.10 × 10−3), and overall CAD (1.145 [1.059, 1.238], P = 6.82 × 10−4), but not with stable angina (1.085 [0.980, 1.203], P = 0.117; Table 1). Meanwhile, we also performed linear regression analyses to evaluate the relationship between RC levels and CAD severity (Table 1). In univariable models, higher RC levels were significantly associated with increased cTnT levels and Gensini score (Table 1), and the multivariable adjusted association remained significant with cTnT levels (β = 0.059, [95%CI, 0.020–0.098], P = 3.29 × 10−3), but was attenuated to be insignificant with Gensini score 0.028 [− 0.013 to 0.069], P = 0.184), although the direction of association remained positive (Table 1). Additionally, during a follow-up of 36 months, 268 MACE cases were recorded. Per SD increase in baseline RC levels was significantly associated with an elevated risk of MACE (HR = 1.140, [95% CI, 1.012–1.286], P = 0.031), and this association remained significant with multivariable adjustment of baseline Gensini score, age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and relevant medication use (HR = 1.137, [95% CI, 1.009–1.282], P = 0.036; Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S3).

Table 1.

Association between baseline remnant cholesterol levels and coronary artery disease status, severity and major adverse cardiovascular events

| Outcome | Sample size | Univariable model | Multivariable modelb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional analysis | ORs or β [95% CI]a | P | ORs or β [95% CI] | P | |

| Disease status | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | Ncase = 453; Ncontrol = 1483 | 1.508 [1.352, 1.685] | 2.44 × 10–13 | 1.352 [1.176, 1.556] | 2.45 × 10–5 |

| Stable angina pectoris | Ncase = 816; Ncontrol = 1483 | 1.149 [1.054, 1.252] | 1.57 × 10–3 | 1.085 [0.980, 1.203] | 0.117 |

| Unstable angina pectoris | Ncase = 967; Ncontrol = 1483 | 1.174 [1.082, 1.274] | 1.24 × 10–4 | 1.130 [1.027, 1.244] | 0.013 |

| Angina pectoris | Ncase = 1783; Ncontrol = 1483 | 1.164 [1.086, 1.248] | 1.83 × 10–5 | 1.115 [1.027, 1.210] | 9.10 × 10–3 |

| Coronary artery disease | Ncase = 2296; Ncontrol = 1483 | 1.219 [1.141, 1.302] | 4.74 × 10–9 | 1.145 [1.059, 1.238] | 6.82 × 10–4 |

| Disease severity | |||||

| Gensini Score | 2289 | 0.045 [0.004, 0.086] | 0.032 | 0.028 [−0.013, 0.069] | 0.184 |

| cTnT | 2277 | 0.045 [0.004, 0.085] | 0.032 | 0.059 [0.020, 0.098] | 3.29 × 10–3 |

| Longitudinal analysis in CAD patients | HR [95% CI] | P | HR [95% CI] | P | |

| Disease prognosis | |||||

| MACE | NMACE = 268; Nnon-MACE = 1722 | 1.140 [1.012, 1.286] | 0.031 | 1.137 [1.009, 1.282] | 0.036 |

aOdds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI were calculated for myocardial infarction, stable angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris, angina pectoris, and coronary artery disease. Estimate β (logORs) with 95% CI were calculated for Gensini score and cTnT

bFor the association between RC levels and myocardial infarction, stable angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris, angina pectoris, coronary artery diseases, Gensini score, and cTnT, we adjusted age, sex, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, antidiabetic drugs use, and antihypertensive drugs use in the multivariable models; for the association between baseline RC levels and the 36-month cumulative incidence of MACE, we adjusted baseline Gensini score, age, sex, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, antidiabetic drugs use, and antihypertensive drugs use in the multivariable models

Seven loci of remnant cholesterol identified through GWAS in the Chinese Population

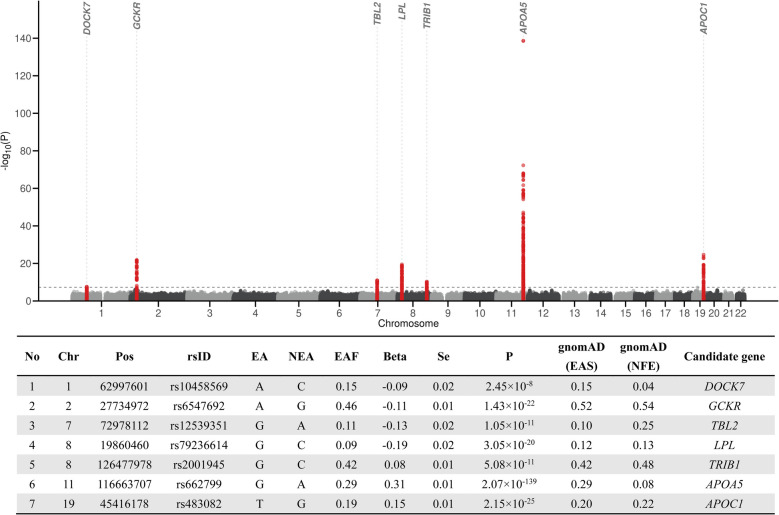

We further investigated the genetic architecture of RC in the Chinese population by conducting a GWAS. The characteristics of Chinese population are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1. The mean (SD) age was 61.1 (14.1) years, the mean (SD) BMI was 24.5 (3.4) kg/m2, and 49.6% were male. In the RC GWAS, the genomic inflation factor indicated minimal risk of excessive population stratification (λgc-meta = 1.027, Additional file 2: Figure S2). The SNP-based heritability (h2) for RC in Chinese was estimated to be 18.8% using LDSC regression. We identified seven genetic loci significantly associated with RC (DOCK7, GCKR, BCL7B, TRIB1, LPL, the APOA5/A4/C3/A1 gene cluster, and APOC1; P < 5 × 10−8), collectively harboring 17 independent associations (LD R2 < 0.1 within 1 Mb distance; Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Table S5). Among these, DOCK7, LPL, the APOA5/A4/C3/A1 gene cluster, and APOC1 were previously implicated in lipid metabolism [44–46]. The GCKR gene encodes the glucokinase regulatory protein, which is involved in various metabolic processes [47]. BCL7B and TRIB1 have also been associated with lipid levels [48, 49]. No novel loci were identified beyond those reported in prior lipid-related GWAS, likely due to the smaller sample size in the Chinese populations. Meanwhile, to assess the potential bias introduced by lipid-lowering medications, we performed sensitivity GWAS analyses after excluding medication users. The lead SNPs remained directionally consistent, with slightly attenuated significance, supporting the robustness of our results (Additional file 2: Figure S3).

Fig. 2.

Results of the meta-analysis of GWAS for remnant cholesterol (RC) levels in 14,939 Han Chinese. The Manhattan plot showed seven significantly associated loci for RC levels. Variants in the seven loci were highlighted in red. The genome-wide threshold for significant (P = 5.0 × 10−8) associations was indicated by the horizontal dashed line

Subsequently, we performed cross-ancestry comparisons focusing on the seven lead loci identified in the Chinese population by conducting a GWAS of RC in the UK Biobank population (Additional file 1: Table S6). Notably, except for the variant rs12539351 (P = 1.0 × 10−3 in UK Biobank), all other six lead SNPs reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in UK Biobank with consistent effect directions. The rs12539351, located near the BCL7B gene, shows different LD structures between East Asian and European populations (Additional file 2: Figure S4), with a larger LD block in East Asians. SNPs in high LD with it have been reported to be associated with lipid traits in both populations [49, 50].

In addition, we observed notable differences in effect sizes and allele frequencies between the two populations. Among the six lead SNPs (out of seven identified in Chinese RC GWAS) reaching genome-wide significance in both ancestries, effect sizes tend to be larger in the Chinese population. Moreover, aside from the seven lead SNPs, six out of 12 additional independent SNPs identified in the Chinese cohort were excluded from the European ancestry analysis due to low allele frequencies (MAF < 0.01).

Genetically predicted remnant cholesterol and cardiovascular diseases in East Asian ancestry individuals

We integrated the GWAS summary statistics for CVDs from Biobank Japan and conducted two-sample MR analyses. Detailed information, including the IVs used, is provided in Additional file 1: Table S7. One palindromic variant, rs2001945 (MAFexposure = 0.42 and MAFoutcome = 0.43), was excluded from the analysis during the harmonization process. The F statistics for all IVs in this study were > 10, indicating no weak instrument bias.

Our analysis revealed several potential causal effects of RC on different cardiovascular outcomes in East Asian ancestry individuals (Fig. 3A and Additional file 1: Table S8). Genetically predicted higher levels of RC were significantly associated with a higher risk of aortic aneurysm (OR per SD increase in RC, 1.83 [95% CI, 1.54–2.17], P = 1.16 × 10−11), myocardial infarction (1.23 [1.13–1.33], P = 4.71 × 10−7), angina pectoris (1.17 [1.08–1.26], P = 1.34 × 10−4), and stable angina pectoris (1.17 [1.10–1.24], P = 1.74 × 10−6). Additionally, genetically predicted higher levels of RC were suggestively associated with an increased risk of unstable angina pectoris (1.15 [1.01–1.30], P = 0.03) and peripheral arterial disease (1.14 [1.04–1.26], P = 0.005). Sensitivity analyses confirmed that the directions of these associations were consistent with the results from the IVW method (Fig. 3A and Additional file 1: Table S8). No significant associations were found for other cardiovascular outcomes, including atrial flutter/fibrillation, cerebral aneurysm, chronic heart failure, intracerebral hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and ventricular arrhythmia (Additional file 1: Table S8). Furthermore, the MR-Egger method showed no evidence of unbalanced pleiotropy affecting these findings (all P for MR-Egger intercept > 0.05; Additional file 1: Table S8). Leave-one-out analyses also indicated that no individual SNP significantly influenced the outcomes, further supporting the robustness of the results (Additional file 2: Figure S5). In addition, to explore the effects of individual RC components on CVD, we further conducted separate MR analyses for IDL-c and VLDL-c on those CVD outcomes where a significant causal association with RC was observed. The results indicated that the effects of both IDL-c and VLDL-c on CVD risk were directionally consistent with those observed for overall RC (Additional file 2: Figure S6).

Fig. 3.

Causal effects of genetically predicted circulating levels of remnant cholesterol on cardiovascular diseases using univariate Mendelian randomization in a population of A East-Asian ancestry and B European ancestry. The inverse variance weighted method was considered the primary result. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the MR-Egger method, weighted median method, weighted mode method, and MR-PRESSO method. The X-axes are shown on a log-transformed scale

Next, we conducted MVMR analyses to assess the independent associations between RC and CVDs across three models (Fig. 4A and Additional file 1: Table S9). Notably, after adjusting for TC (Model 1), LDL-c and HDL-c (Model 2), and ApoA1 and ApoB (Model 3), the associations between RC and aortic aneurysm, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and stable angina pectoris remained statistically significant (all P < 0.05), suggesting that RC exerts a causal effect on these cardiovascular outcomes independent of other lipoproteins (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the suggestively significant association with unstable angina pectoris was no longer observed in model 1, and the association with peripheral arterial disease disappeared in model 1 and model 2 (Fig. 4A). However, the direction of association remained consistent with those observed in the primary analyses.

Fig. 4.

Causal effects of genetically predicted circulating remnant cholesterol levels on cardiovascular diseases in populations of A East Asian ancestry and B European ancestry, using univariable and multivariable Mendelian randomization (MR). The primary results were derived using the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method under the univariable MR framework. Sensitivity analyses were performed using multivariable MR with Model 1: total cholesterol (TC); Model 2: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c); Model 3: apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) and apolipoprotein B (ApoB). X-axes are shown on a log-transformed scale

Two-sample Mendelian randomization in population of European ancestry

To replicate the associations between genetically predicted RC and CVDs in a population of European ancestry, we first conducted a GWAS for RC using data from Europeans of the UK Biobank. We identified a total of 26,905 significant variants (P < 5 × 10−8), including 134 lead SNPs (R2 < 0.001, justifying the larger sample size of Europeans, Additional file 2: Figure S7). Using LDSC regression, we estimated the SNP-based heritability of RC in a population of European ancestry to be 14.4%, which is comparable to a previous estimate of 12.6% reported in an NMR-based metabolomics GWAS [51]. We then integrated the CVD GWAS summary statistics from FinnGen (R12, the latest release) and conducted two-sample MR in European ancestry population. We analyzed 12 CVDs, excluding stable angina pectoris, which was unavailable from the FinnGen database based on the ICD-10 codes (Additional file 1: Table S4).

The summary information for the 134 lead SNPs used as candidate IVs for RC in European ancestry individuals is provided in Additional file 1: Table S10. Three palindromic variants (rs6721748, rs7544869, rs9848779, and rs9388530) with an MAF > 0.42 were removed from the analyses. The F statistics for all IVs were > 10, indicating no weak instrument bias.

Consistent with the findings in East Asian ancestry individuals, genetically predicted higher levels of RC were significantly associated with an increased risk of aortic aneurysm (1.31 [1.19–1.44], P = 4.75 × 10−8), myocardial infarction (1.45 [1.33–1.59], P = 5.37 × 10−16), angina pectoris (1.46 [1.35–1.58], P = 1.45 × 10−20), unstable angina pectoris (1.48 [1.34–1.63], P = 1.37 × 10−15), and atrial flutter/fibrillation (1.11 [1.04–1.19], P = 1.99 × 10−3) in European ancestry individuals (Fig. 3B and Additional file 1: Table S11). Notably, the causal effect of RC on atrial flutter/fibrillation was not observed in East Asian ancestry individuals (0.97 [0.88–1.07], P = 0.57; Fig. 3B). Meanwhile, the magnitude of RC-associated risk for aortic aneurysm was higher in East Asian ancestry individuals than in European ancestry individuals (OREAS = 1.83 vs. OREUR = 1.31), whereas the magnitude of RC-associated risk for ischemic heart diseases was greater in European ancestry individuals (e.g., for myocardial infarction OREAS = 1.23 vs. OREUR = 1.45, Fig. 3). Moreover, genetically predicted higher levels of RC were suggestively associated with an increased risk of ventricular arrhythmia (1.06 [1.01–1.11], P = 0.009). However, no significant association was found between genetically predicted RC levels and peripheral arterial disease in European ancestry individuals (0.98 [0.87–1.11] in European ancestry individuals versus 1.14 [1.04–1.26] in East Asian ancestry individuals).

Although we observed potentially unbalanced pleiotropy in the analyses for angina pectoris and myocardial infarction (P for intercept < 0.05 based on the MR-Egger’s intercept test; Additional file 1: Table S11), the MR-Egger method still supported a causal association between RC and these outcomes (1.64 [1.44–1.86], P = 3.33 × 10−12) and myocardial infarction (1.64 [1.42–1.89], P = 2.65 × 10−10). Leave-one-out analyses showed that no single SNP had a significant impact on the results (Additional file 2: Figure S8). As in East Asian ancestry individuals, genetically predicted RC levels were not associated with cerebral aneurysm, chronic heart failure, ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, or subarachnoid hemorrhage in European ancestry individuals (Additional file 1: Table S11). Similarly, in the population of European ancestry, IDL-c and VLDL-c demonstrated causal effect directions aligned with those of RC, with no evidence of heterogeneity (Additional file 2: Figure S9).

We also conducted the MVMR analyses in European ancestry population. After adjusting for TC, the causal associations between RC and aortic aneurysm, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris, atrial flutter/fibrillation, and ventricular arrhythmia remained statistically significant (Fig. 4B and Additional file 1: Table S12, all P < 0.05). However, in Model 2, which adjusted for LDL-c and HDL-c, and in Model 3, which adjusted for ApoA1 and ApoB, the statistical significance of several associations was no longer observed. This may be attributed to a drop in the conditional F statistic below 10, suggesting that these analyses may be affected by weak instrument bias (Additional file 1: Table S12). Nonetheless, the associations retained the same directional trend as observed in the primary analyses.

Reverse MR analyses assessing the causal effects of cardiovascular diseases on remnant cholesterol

To evaluate the possibility of reverse causality and to support the robustness of our primary findings, we conducted reverse MR analyses to assess the causal effects of CVDs on the levels of RC both in East Asian and European ancestry individuals (Fig. 5). Detailed information on the IVs for each CVD outcome is provided in Additional file 1: Table S13 for East Asian ancestry individuals and Additional file 1: Table S14 for European ancestry individuals.

Fig. 5.

Causal effects of genetically predicted cardiovascular diseases on circulating remnant cholesterol levels in East Asian ancestry individuals (inner circle) and European ancestry individuals (outer circle). The potential causal association was evaluated using two-sample MR analyses with the IVW method. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the MR-Egger method, weighted median method, weighted mode method, and MR-PRESSO method. The results are presented as causal estimates with Beta (SE) for each disease status

No significant associations were observed between genetically predicted CVDs and RC after correction for multiple testing (P < 0.0038) in either populations of East Asian ancestry or European ancestry, though genetically predicted higher risks of ischemic heart diseases showed suggestive associations in both populations (all 0.0038 < P < 0.05; Fig. 5, Additional file 1: Tables S15–S16). No causal relationships were observed between other CVDs and RC. Furthermore, the removal of any individual SNP did not significantly affect the results (Figures S10 and S11).

Discussion

In the population of East Asian ancestry, our study revealed elevated RC as an independent causal risk factor for aortic aneurysm and ischemic heart diseases, including myocardial infarction and angina pectoris. Notably, these causal associations persisted after rigorous adjustment for traditional lipid measures (TC, LDL-c, HDL-c, ApoA1, or ApoB) using MVMR, underscoring the unique role of RC in cardiovascular pathophysiology. While these results are in line with previous findings based on European ancestry populations supporting the broad causal relevance of RC to CVD, we identified population-specific risk gradients. Although the direction of effect is consistent, there is heterogeneity in effect sizes between individuals of East Asian and European ancestry in the MR analyses (e.g., risk for aortic aneurysm and ischemic heart disease seems higher for East Asian ancestry population). However, caution is warranted in interpreting these differences, as different IVs were constructed for each population. This heterogeneity highlights divergent cardiovascular consequences of RC across ethnicities, likely reflecting differences in genetic architecture, lipid metabolism, or environmental modifiers.

Observational studies across diverse populations revealed that RC levels are positively associated with CVD risks [10–12]. For example, in the Copenhagen General Population Study, the HR for the risk of ischemic heart disease was 2.3 (95% CI, 1.7–3.1) comparing participants with the highest versus the lowest quintile of RC [10]. MR studies in European ancestry population further validated RC’s causal role [16–18]. In populations of East Asian ancestry, such as Lee et al.’s nationwide Korean study, elevated RC was linked to CVD risk even after LDL-c adjustment [52]. However, causal inference in East Asian ancestry individuals has been hindered by the absence of large-scale RC GWAS. By performing the first RC GWAS in > 14,000 East Asian ancestry individuals and integrating MR, our study bridges this critical gap, enabling robust causal assessment in this underrepresented population. Moreover, our reverse MR analyses found no evidence for a causal effect of CVD on RC levels, helping to rule out reverse causality. This directional confirmation not only suggests that previous observational associations were unlikely to have been driven by reverse causation but also strengthens the robustness of the observed RC-to-CVD causal relationship and adds confidence to the inference that lowering RC may be an effective strategy for CVD prevention.

RC primarily refers to the cholesterol content within triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, including chylomicrons, VLDL, and IDL, which can enter the arterial intima and become preferentially trapped due to their relatively large size [8, 9]. Recent studies have shown that RC is emerging as an important residual risk factor beyond LDL-c in the development of CVD [53], through mechanisms such as endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and plaque destabilization [54]. Our results extend prior observational and MR evidence linking RC to CVD risk in both Europeans and East Asian ancestry populations, but uniquely highlight aortic aneurysm as a priority outcome in East Asian ancestry populations. While aortic aneurysm is often considered a late-stage complication of atherosclerosis [55], our MR findings suggest RC may directly drive vascular remodeling and aneurysm formation, independent of classical atherosclerotic pathways [56]. This observation is consistent with recent multi-ancestry studies implicating dyslipidemia in aneurysm pathogenesis [16, 57] and emphasizes the outsized role of RC in East Asian ancestry individuals, where non-HDL cholesterol levels are rising disproportionately [58]. Current lipid-lowering therapies predominantly target LDL-c, yet our data suggest RC contributes to residual CVD risk unmitigated by statins. This is particularly relevant in East Asia, where aortic aneurysm prevalence is increasing but underrecognized [59, 60]. Conversely, the higher ischemic heart disease risks observed in European ancestry population may reflect population-specific interactions between RC and other metabolic risk factors (e.g., insulin resistance) [61, 62], warranting tailored interventions.

Strengths of our study include the direct measurement of RC using NMR technology, a method shown to be more accurate than calculations based on traditional clinical lipid measurements [63]. We employed two-sample MR analysis to mitigate confounding and replicated our findings across ethnic populations using large-scale biobanks, including Biobank Japan, FinnGen, and the UK Biobank. Sensitivity analyses, such as MR-Egger and MVMR, further demonstrated the robustness of our results against pleiotropy and adjustments for lipid covariates.

Limitations of this study should also be noted. First, the modest sample size of the Chinese RC GWAS (N = 14,939) limited statistical power to detect novel RC-associated loci, though this did not compromise the MR findings. As a result, no novel loci were identified beyond those previously reported in European ancestry GWAS. Nevertheless, our study provides the first ancestry-specific genetic evidence for remnant cholesterol in East Asian ancestry populations, filling a critical gap in the literature. Second, genetic variants associated with metabolic traits may impact CVD risk through pleiotropic pathways involving unmeasured confounders. To address this, multiple MR models were applied in sensitivity analyses, which reinforced the reliability of our conclusions despite potential violations of MR assumptions. Third, while MVMR suggested independence of our results from LDL-c and ApoB, weak instrument bias in European ancestry population analyses precluded definitive conclusions regarding these associations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study reveals that, in populations of East Asian ancestry, genetically determined higher levels of RC are associated with various adverse cardiovascular outcomes, even independently of other lipid traits. Our findings bridge a critical gap in understanding the causal role of RC in populations of East Asian ancestry and highlight aortic aneurysm as a key outcome for targeted intervention. Future research should elucidate mechanisms linking RC to vascular remodeling and evaluate RC-lowering therapies (e.g., fibrates, omega-3 fatty acids) in diverse populations. Addressing these gaps will advance precision strategies to reduce the global burden of RC-driven CVDs.

Supplementary Information

Additional File 1: Tables S1-S16. Table S1 - Characteristics of the including study populations. Table S2 - The characteristics of GRAND cohort in the cross-section study. Table S3 - The characteristics of GRAND cohort in the longitudinal study. Table S4 - Data sources of GWASs for remnant cholesterol and cardiovascular diseases. Table S5- Summary of seven loci associated with remnant cholesterol in Meta-analysis of four Chinese studies. Table S6 - Comparison of seven loci associated with remnant cholesterol identified in the meta-analysis of four Chinese studies with corresponding results in the UK Biobank population. Table S7 - Effect estimates of the associations between genetic instrumental variables for remnant cholesterol and cardiovascular diseases in East Asians. Table S8 - Causal effects of remnant cholesterol on cardiovascular diseases in East Asians. Table S9 - Multivariable Mendelian randomization results of remnant cholesterol and each lipid profile component on cardiovascular diseases in East Asians. Table S10 - Effect estimates of the associations between genetic instrumental variables for remnant cholesterol and cardiovascular diseases in Europeans. Table S11 - Causal effects of remnant cholesterol on cardiovascular diseases in Europeans. Table S12 - Multivariable Mendelian randomization results of remnant cholesterol and each lipid profile component on cardiovascular diseases in Europeans. Table S13 - Effect estimates of the associations between genetic instrumental variables for cardiovascular diseases and remnant cholesterol in East Asians. Table S14 - Effect estimates of the associations between genetic instrumental variables for cardiovascular diseases and remnant cholesterol in Europeans. Table S15 - Association of genetically predicted risk of cardiovascular diseases with remnant cholesterol using univariable inverse-variance weighted method and sensitivity analyses in East Asians. Table S16 - Association of genetic predisposition to cardiovascular diseases with remnant cholesterol in univariable inverse-variance weighted analyses and in sensitivity analyses in Europeans.

Additional File 2: Supplementary method and Figures S1-S11. Supplementary method 1- Nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics profiling and data processing in four Chinses populations. Figure S1 - The workflow of Mendelian randomization in the current study. Figure S2 - Quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots of GWAS results. Figure S3 - Comparison of effect sizes and P values for 17 identified independent significant associations between the full Chinese population sample and the subset excluding lipid-lowering drug users. Figure S4 - Comparison of linkage disequilibrium pattern of rs12539351 in East Asian ancestry population and European ancestry population. Figure S5 - The leave-one-out analysis for the identified significant casual effects of RC on cardiovascular diseases in East Asians. Figure S6 - Mendelian randomization estimates of RC and its components (IDL-c and VLDL-c) on CVDs in East-Asian ancestry population. Figure S7 - Results of GWAS for RC levels in Europeans of UK Biobank. Figure S8 - The leave-one-out analysis for the identified significant casual effect of RC on cardiovascular diseases in Europeans. Figure S9 - Mendelian randomization estimates of RC and its components (IDL-c and VLDL-c) on CVDs in European ancestry population. Figure S10 - The leave-one-out analyses for the casual effect of cardiovascular diseases on RC in East Asians. Figure S11 - The leave-one-out analyses for the casual effect of cardiovascular diseases on RC in Europeans.

Additional File 3: STROBE-MR checklist of recommended items to address in reports of Mendelian randomization studies.

Acknowledgements

The data analysis server is supported by the Human Phenome Data Center of Fudan University, and we thank the center staff for their support. UK Biobank approved this present research under application number 54294. We gratefully acknowledge the contributors to the data used in this work.

Abbreviations

- ApoA1

Apolipoprotein A1

- ApoB

Apolipoprotein B

- BMI

Body mass index

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CI

Confidence interval

- cTnT

Cardiac troponin T

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- GRAND

The Genetic characteristics of coRonary Artery disease in ChiNese young aDults study

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- HDL-c

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HR

Hazard ratio

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- IDL

Intermediate-density lipoprotein

- INFO

Imputation quality

- IV

Instrumental variable

- IVW

Inverse variance weighted

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- LDL-c

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MACE

Major adverse cardiovascular event

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- MR

Mendelian randomization

- MVMR

Multivariable Mendelian randomization

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- OR

Odds ratio

- RC

Remnant cholesterol

- SD

Standard deviation

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TC

Total cholesterol

- VLDL

Very-low-density lipoprotein

Authors’ contributions

C.L., H.W., and Y.Z. drafted the manuscript. C.L. and H.W. performed formal statistical analysis. J.L., W.Y., and J.M.J.W. assisted with statistical analysis. Q.X.H., Q.W., and H.T. provided metabolite measurements and quality control in the study. Y.Z., Y.D., M.X., L.J, X.W, S.W., and H.T. organized data collection and/or preparation. G.C. and M.Y. provided critical comments on the manuscript. G.C. and Y.Z. conceived the idea and approach, and supervised the research. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC3400700, 2022YFA0806400), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2023SHZDZX02 and 2017SHZDZX01), the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning, Grant of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2022JC012), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82370357), grant from the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2022JC012), the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (22XD1423300) and Shanghai Oriental Youth Elite Talents Program (QNZH2024009).

Data availability

The UK Biobank data are available from the UK Biobank application (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). The GWAS summary statistics of Biobank Japan are available from the website of Biobank Japan (https://pheweb.jp/) [64]. The GWAS summary statistics of FinnGen (R12) are available from the website of FinnGen https://www.finngen.fi/en/access_results) [65]. The data required for the analysis of the article are provided in the Supplementary Tables, and further data can be obtained by a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The National Survey of Physical Traits is the subproject of the National Science & Technology Basic Research Project which was approved by the Ethics Committee of Human Genetic Resources of the School of Life Sciences, Fudan University (14117). The Shanghai Changfeng study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (2013–132). The Rugao Longevity and Aging study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the School of Life Sciences, Fudan University (BE1815). The GRAND study was approved by the central Ethics Committee at Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (B2017-051). All participants or their legal representatives provided informed consent before joining the study.

Consent for publication

All authors have consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chenhao Lin, Haolong Wen and Mengyao Yu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yuxiang Dai, Email: dai.yuxiang@hotmail.com.

Guo-Chong Chen, Email: gcchen@suda.edu.cn.

Yan Zheng, Email: yan_zheng@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. A century of cholesterol and coronaries: from plaques to genes to statins. Cell. 2015;161(1):161–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ference BA, Braunwald E, Catapano AL. The LDL cumulative exposure hypothesis: evidence and practical applications. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21(10):701–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, Hegele RA, Krauss RM, Raal FJ, Schunkert H, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Komajda M, Lopez-Sendon J, Mosca L, Tardif JC, Waters DD, et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lincoff AM, Nicholls SJ, Riesmeyer JS, Barter PJ, Brewer HB, Fox KAA, Gibson CM, Granger C, Menon V, Montalescot G, et al. Evacetrapib and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20):1933–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhindsa DS, Sandesara PB, Shapiro MD, Wong ND. The evolving understanding and approach to residual cardiovascular risk management. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman MJ, Ginsberg HN, Amarenco P, Andreotti F, Boren J, Catapano AL, Descamps OS, Fisher E, Kovanen PT, Kuivenhoven JA, et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence and guidance for management. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(11):1345–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boren J, Taskinen MR, Bjornson E, Packard CJ. Metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in health and dyslipidaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19(9):577–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordestgaard BG. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: new insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. Circ Res. 2016;118(4):547–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varbo A, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG. Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):427–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadstrom BN, Wulff AB, Pedersen KM, Jensen GB, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated remnant cholesterol increases the risk of peripheral artery disease, myocardial infarction, and ischaemic stroke: a cohort-based study. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(34):3258–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quispe R, Martin SS, Michos ED, Lamba I, Blumenthal RS, Saeed A, Lima J, Puri R, Nomura S, Tsai M, et al. Remnant cholesterol predicts cardiovascular disease beyond LDL and ApoB: a primary prevention study. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(42):4324–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arsenault BJ, Boekholdt SM, Kastelein JJ. Lipid parameters for measuring risk of cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(4):197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes MV, Asselbergs FW, Palmer TM, Drenos F, Lanktree MB, Nelson CP, Dale CE, Padmanabhan S, Finan C, Swerdlow DI, et al. Mendelian randomization of blood lipids for coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(9):539–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levin MG, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization as a tool for cardiovascular research: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2024;9(1):79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan B, Wang A, Xu H. Causal associations of remnant cholesterol with cardiometabolic diseases and risk factors: a mendelian randomization analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navarese EP, Vine D, Proctor S, Grzelakowska K, Berti S, Kubica J, Raggi P. Independent causal effect of remnant cholesterol on atherosclerotic cardiovascular outcomes: a Mendelian randomization study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2023;43(9):e373–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Zhuang Z, Li Y, Xiao W, Song Z, Huang N, Wang W, Dong X, Jia J, Clarke R, et al. Elevated blood remnant cholesterol and triglycerides are causally related to the risks of cardiometabolic multimorbidity. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakaue S, Kanai M, Tanigawa Y, Karjalainen J, Kurki M, Koshiba S, Narita A, Konuma T, Yamamoto K, Akiyama M, et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2021;53(10):1415–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, Sipila TP, Kristiansson K, Donner KM, Reeve MP, Laivuori H, Aavikko M, Kaunisto MA, et al. Finngen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature. 2023;613(7944):508–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao X, Hofman A, Hu Y, Lin H, Zhu C, Jeekel J, Jin X, Wang J, Gao J, Yin Y, et al. The Shanghai Changfeng study: a community-based prospective cohort study of chronic diseases among middle-aged and elderly: objectives and design. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(12):885–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Q, Huang QX, Zeng HL, Ma S, Lin HD, Xia MF, Tang HR, Gao X. Prediction of metabolic disorders using NMR-based metabolomics: the Shanghai Changfeng study. Phenomics. 2021;1(4):186–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang Q, Qadri SF, Bian H, Yi X, Lin C, Yang X, Zhu X, Lin H, Yan H, Chang X et al: A metabolome-derived score predicts metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and mortality from liver disease. J Hepatol 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Liu Z, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Chu X, Wang Z, Qian D, Chen F, Xu J, Li S, Jin L, et al. Cohort profile: the Rugao Longevity and Ageing Study (RuLAS). Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(4):1064–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang F, Luo Q, Chen Y, Liu Y, Xu K, Adhikari K, Cai X, Liu J, Li Y, Liu X et al: A genome-wide scan on individual typology angle found variants at SLC24A2 associated with skin color variation in Chinese populations. J Invest Dermatol 2022, 142(4):1223–1227 e1214. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Shalaimaiti S, Dai Y-X, Wu H-Y, Qian J-Y, Zheng Y, Yao K, Ge J-B. Clinical and genetic characteristics of coronary artery disease in Chinese young adults: rationale and design of the prospectivegenetic characteristics of coronaryartery disease in ChiNese young aDults (GRAND) Study. Cardiology Plus. 2021;6(1):65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mei Z, Xu L, Huang Q, Lin C, Yu M, Shali S, Wu H, Lu Y, Wu R, Wang Z, et al. Metabonomic biomarkers of plaque burden and instability in patients with coronary atherosclerotic disease after moderate lipid-lowering therapy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(24): e036906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, Motyer A, Vukcevic D, Delaneau O, O’Connell J, et al. The UK biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562(7726):203–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Julkunen H, Cichonska A, Tiainen M, Koskela H, Nybo K, Makela V, Nokso-Koivisto J, Kristiansson K, Perola M, Salomaa V, et al. Atlas of plasma NMR biomarkers for health and disease in 118,461 individuals from the UK Biobank. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jimenez B, Holmes E, Heude C, Tolson RF, Harvey N, Lodge SL, Chetwynd AJ, Cannet C, Fang F, Pearce JTM, et al. Quantitative lipoprotein subclass and low molecular weight metabolite analysis in human serum and plasma by (1)H NMR spectroscopy in a multilaboratory trial. Anal Chem. 2018;90(20):11962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang Q, Chen Q, Yi X, Wang H, Wang Q, Zhi H, Wu J, Wang DW, Tang H: Reproducibility of NMR-based quantitative metabolomics and HBV-caused changes in human serum lipoprotein subclasses and small metabolites. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2024:101180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Graham SE, Clarke SL, Wu KH, Kanoni S, Zajac GJM, Ramdas S, Surakka I, Ntalla I, Vedantam S, Winkler TW, et al. The power of genetic diversity in genome-wide association studies of lipids. Nature. 2021;600(7890):675–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loh PR, Tucker G, Bulik-Sullivan BK, Vilhjalmsson BJ, Finucane HK, Salem RM, Chasman DI, Ridker PM, Neale BM, Berger B, et al. Efficient bayesian mixed-model analysis increases association power in large cohorts. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):284–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;362: k601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierce BL, Ahsan H, Vanderweele TJ. Power and instrument strength requirements for Mendelian randomization studies using multiple genetic variants. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):740–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowden J, Holmes MV. Meta-analysis and Mendelian randomization: a review. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(4):486–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Yarmolinsky J, Davies NM, Swanson SA, VanderWeele TJ, Higgins JPT, Timpson NJ, Dimou N, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR statement. JAMA. 2021;326(16):1614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Davies NM, Swanson SA, VanderWeele TJ, Timpson NJ, Higgins JPT, Dimou N, Langenberg C, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomisation (STROBE-MR): explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2021;375: n2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanderson E, Glymour MM, Holmes MV, Kang H, Morrison J, Munafò MR, Palmer T, Schooling CM, Wallace C, Zhao Q, et al. Mendelian randomization. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2022;2(1): 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Oliveira-Gomes D, Joshi PH, Peterson ED, Rohatgi A, Khera A, Navar AM. Apolipoprotein B: bridging the gap between evidence and clinical practice. Circulation. 2024;150(1):62–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanderson E, Davey Smith G, Windmeijer F, Bowden J. An examination of multivariable Mendelian randomization in the single-sample and two-sample summary data settings. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(3):713–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagy R, Boutin TS, Marten J, Huffman JE, Kerr SM, Campbell A, Evenden L, Gibson J, Amador C, Howard DM, et al. Exploration of haplotype research consortium imputation for genome-wide association studies in 20,032 Generation Scotland participants. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinnott-Armstrong N, Tanigawa Y, Amar D, Mars N, Benner C, Aguirre M, Venkataraman GR, Wainberg M, Ollila HM, Kiiskinen T, et al. Genetics of 35 blood and urine biomarkers in the UK Biobank. Nat Genet. 2021;53(2):185–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waterworth DM, Ricketts SL, Song K, Chen L, Zhao JH, Ripatti S, Aulchenko YS, Zhang W, Yuan X, Lim N, et al. Genetic variants influencing circulating lipid levels and risk of coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(11):2264–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, Pirruccello JP, Ripatti S, Chasman DI, Willer CJ, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466(7307):707–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richardson TG, Sanderson E, Palmer TM, Ala-Korpela M, Ference BA, Davey Smith G, Holmes MV. Evaluating the relationship between circulating lipoprotein lipids and apolipoproteins with risk of coronary heart disease: a multivariable mendelian randomisation analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(3): e1003062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karjalainen MK, Karthikeyan S, Oliver-Williams C, Sliz E, Allara E, Fung WT, Surendran P, Zhang W, Jousilahti P, Kristiansson K, et al. Genome-wide characterization of circulating metabolic biomarkers. Nature. 2024;628(8006):130–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim YJ, Go MJ, Hu C, Hong CB, Kim YK, Lee JY, Hwang JY, Oh JH, Kim DJ, Kim NH, et al. Large-scale genome-wide association studies in East Asians identify new genetic loci influencing metabolic traits. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):990–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagenbeek FA, Pool R, van Dongen J, Draisma HHM, Jan Hottenga J, Willemsen G, Abdellaoui A, Fedko IO, den Braber A, Visser PJ, et al. Heritability estimates for 361 blood metabolites across 40 genome-wide association studies. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee SJ, Kim S-E, Go T-H, Kang DR, Jeon H-S, Kim Y-I, Cho D-H, Park YJ, Lee J-H, Lee J-W, et al. Remnant cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and incident cardiovascular disease among Koreans: a national population-based study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023;30(11):1142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burnett JR, Hooper AJ, Hegele RA. Remnant cholesterol and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(23):2736–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz EA, Reaven PD. Lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, vascular inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821(5):858–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golledge J, Norman PE. Atherosclerosis and abdominal aortic aneurysm: cause, response, or common risk factors? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(6):1075–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golledge J. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: update on pathogenesis and medical treatments. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(4):225–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng S, Tsao PS, Pan C. Abdominal aortic aneurysm and cardiometabolic traits share strong genetic susceptibility to lipid metabolism and inflammation. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Taddei C, Zhou B, Bixby H, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, Jackson R, Farzadfar F, Sophiea MK, Di Cesare M, Iurilli MLC et al: Repositioning of the global epicentre of non-optimal cholesterol. Nature 2020, 582(7810):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Song P, He Y, Adeloye D, Zhu Y, Ye X, Yi Q, Rahimi K, Rudan I, Global Health Epidemiology Research G. The global and regional prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a systematic review and modeling analysis. Ann Surg. 2023;277(6):912–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goh RSJ, Chong B, Jayabaskaran J, Jauhari SM, Chan SP, Kueh MTW, Shankar K, Li H, Chin YH, Kong G, et al. The burden of cardiovascular disease in Asia from 2025 to 2050: a forecast analysis for East Asia, South Asia, South-East Asia, Central Asia, and high-income Asia Pacific regions. Lancet Reg Health. 2024;49: 101138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhatnagar A. Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2017;121(2):162–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bays HE, Kulkarni A, German C, Satish P, Iluyomade A, Dudum R, Thakkar A, Rifai MA, Mehta A, Thobani A, et al. Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors - 2022. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022;10: 100342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sturzebecher PE, Katzmann JL, Laufs U. What is ‘remnant cholesterol’? Eur Heart J. 2023;44(16):1446–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Biobank Japan access results. Available from: https://pheweb.jp/. Cited 2025 January 2

- 65. FinnGen access results. Available from: https://www.finngen.fi/en/access_results. Cited 2025 January 2

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional File 1: Tables S1-S16. Table S1 - Characteristics of the including study populations. Table S2 - The characteristics of GRAND cohort in the cross-section study. Table S3 - The characteristics of GRAND cohort in the longitudinal study. Table S4 - Data sources of GWASs for remnant cholesterol and cardiovascular diseases. Table S5- Summary of seven loci associated with remnant cholesterol in Meta-analysis of four Chinese studies. Table S6 - Comparison of seven loci associated with remnant cholesterol identified in the meta-analysis of four Chinese studies with corresponding results in the UK Biobank population. Table S7 - Effect estimates of the associations between genetic instrumental variables for remnant cholesterol and cardiovascular diseases in East Asians. Table S8 - Causal effects of remnant cholesterol on cardiovascular diseases in East Asians. Table S9 - Multivariable Mendelian randomization results of remnant cholesterol and each lipid profile component on cardiovascular diseases in East Asians. Table S10 - Effect estimates of the associations between genetic instrumental variables for remnant cholesterol and cardiovascular diseases in Europeans. Table S11 - Causal effects of remnant cholesterol on cardiovascular diseases in Europeans. Table S12 - Multivariable Mendelian randomization results of remnant cholesterol and each lipid profile component on cardiovascular diseases in Europeans. Table S13 - Effect estimates of the associations between genetic instrumental variables for cardiovascular diseases and remnant cholesterol in East Asians. Table S14 - Effect estimates of the associations between genetic instrumental variables for cardiovascular diseases and remnant cholesterol in Europeans. Table S15 - Association of genetically predicted risk of cardiovascular diseases with remnant cholesterol using univariable inverse-variance weighted method and sensitivity analyses in East Asians. Table S16 - Association of genetic predisposition to cardiovascular diseases with remnant cholesterol in univariable inverse-variance weighted analyses and in sensitivity analyses in Europeans.

Additional File 2: Supplementary method and Figures S1-S11. Supplementary method 1- Nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomics profiling and data processing in four Chinses populations. Figure S1 - The workflow of Mendelian randomization in the current study. Figure S2 - Quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots of GWAS results. Figure S3 - Comparison of effect sizes and P values for 17 identified independent significant associations between the full Chinese population sample and the subset excluding lipid-lowering drug users. Figure S4 - Comparison of linkage disequilibrium pattern of rs12539351 in East Asian ancestry population and European ancestry population. Figure S5 - The leave-one-out analysis for the identified significant casual effects of RC on cardiovascular diseases in East Asians. Figure S6 - Mendelian randomization estimates of RC and its components (IDL-c and VLDL-c) on CVDs in East-Asian ancestry population. Figure S7 - Results of GWAS for RC levels in Europeans of UK Biobank. Figure S8 - The leave-one-out analysis for the identified significant casual effect of RC on cardiovascular diseases in Europeans. Figure S9 - Mendelian randomization estimates of RC and its components (IDL-c and VLDL-c) on CVDs in European ancestry population. Figure S10 - The leave-one-out analyses for the casual effect of cardiovascular diseases on RC in East Asians. Figure S11 - The leave-one-out analyses for the casual effect of cardiovascular diseases on RC in Europeans.

Additional File 3: STROBE-MR checklist of recommended items to address in reports of Mendelian randomization studies.

Data Availability Statement

The UK Biobank data are available from the UK Biobank application (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). The GWAS summary statistics of Biobank Japan are available from the website of Biobank Japan (https://pheweb.jp/) [64]. The GWAS summary statistics of FinnGen (R12) are available from the website of FinnGen https://www.finngen.fi/en/access_results) [65]. The data required for the analysis of the article are provided in the Supplementary Tables, and further data can be obtained by a reasonable request to the corresponding author.