Abstract

The ability of Listeria monocytogenes to tolerate salt stress is of particular importance, as this pathogen is often exposed to such environments during both food processing and food preservation. In order to understand the survival mechanisms of L. monocytogenes, an initial approach using two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed to analyze the pattern of protein synthesis in response to salt stress. Of 400 to 500 visible proteins, the synthesis of 40 proteins (P < 0.05) was repressed or induced at a higher rate during salt stress. Some of the proteins were identified on the basis of mass spectrometry or N-terminal sequence analysis and database searching. Twelve proteins showing high induction after salt stress were similar to general stress proteins (Ctc and DnaK), transporters (GbuA and mannose-specific phosphotransferase system enzyme IIAB), and general metabolism proteins (alanine dehydrogenase, CcpA, CysK, EF-Tu, Gap, GuaB, PdhA, and PdhD).

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive, food-borne human pathogen which causes listeriosis in immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women (11). This microorganism can survive a variety of environmental stresses, such as 10% NaCl solutions (26) and a range of temperatures from −0.1 to 45°C (37). The bacterium is also able to tolerate a pH as low as 3.5 after an adaptation phase at pH 5.5 (28). This high degree of adaptability is one reason for the difficulty in controlling the pathogen in a number of food products, since treatments used in food processing and preservation often utilize stressing agents and parameters to which L. monocytogenes is resistant. Salt (NaCl) is one of the most commonly employed agents for food conservation, allowing considerable increase in storage time by reducing water activity. However, L. monocytogenes is frequently isolated from food containing high quantities of salt, such as smoked salmon (10). The bacterium can also be detected after 150 days in pure salt at 22°C (15). A better knowledge of the adaptive mechanisms of L. monocytogenes to salt stress could lead to better control and prevention of this pathogen in food-processing plants.

When bacteria are subjected to a sudden shift in one or several parameters affecting their growth or survival, a program of gene expression is initiated, which is manifested as an increased or decreased amount of a set of proteins synthesized in response to stress. For instance, in Bacillus subtilis, salt stress strongly stimulates the expression of a set of proteins that probably allow the bacterium to survive in the rapidly changing environment. Salt also down-regulates the expression of other proteins which do not appear to be necessary for survival (7, 13, 22). In the case of L. monocytogenes, it has been shown that the microorganism responds to elevated osmolarity in the environment by the intracellular accumulation of compatible solutes, called osmolytes, through osmotic activation of their transport from the medium rather than through de novo synthesis. Among the compatible solutes, glycine betaine and carnitine are the most effective, particularly against osmotic stress (4, 21, 34). These osmolytes act in the cytosol by counterbalancing the external osmolarity, thus preventing water loss from the cell and plasmolysis without adversely affecting macromolecular structure and function (6).

Although a number of studies of the protective effect of osmolytes in L. monocytogenes have been published, the study of the variations of protein expression in response to salt stress has just begun (8). In order to achieve a better understanding of the impact of salt stress during food processing and preservation, the effect of NaCl on the protein expression of L. monocytogenes was studied. For that purpose, the two-dimensional (2-D) electrophoresis method, an approach that has often proved to be the appropriate tool to study the general expression levels of proteins, was used (29). Identification of salt shock proteins and salt acclimation proteins was also undertaken by mass spectrometry (MS) or N-terminal sequencing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions.

The L. monocytogenes LO28 strain (serotype 1/2c) was used throughout this study. This strain is a clinical isolate and was a gift from P. Cossart (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). L. monocytogenes was grown in MCDB 202 medium (Cryobiosystem, L'Aigle, France), a chemically defined medium (17). This medium has a low methionine content (4.4 μg/ml) and was supplemented with 1% yeast nitrogen base (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and 3.6 g of glucose/liter. The pH was adjusted to 7.3.

Salt stress and radioactive labeling of cultures.

Cultures of L. monocytogenes were grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.3) in supplemented MCDB 202 medium at 37°C with shaking, and solid NaCl was added to a final concentration of 3.5% (wt/vol). To 4-ml aliquots of this culture, 400 μCi of a mix containing 73% l-[35S]methionine and 22% l-[35S]cysteine (EXPRE35S35S labeling mixture; NEN-Dupont, les Ulis, France) was added immediately after the addition of NaCl or 1 h later. After 30 min of labeling, the bacteria were washed twice and resuspended in 1 ml of 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, containing 5 mM EDTA and 5 mM MgCl2. The cells were then sonicated with a Vibra cell (Bioblock Scientific, Illkirch, France) three times for 2 min each time on ice at power level 5 and 50% of the duty cycle. The suspension was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min to pellet the unbroken bacteria and bacterial cell walls. The incorporated radioactivity was determined by precipitating 2 μl of cell extracts onto glass fiber filters (Whatman GF/C) with cold 25% (vol/vol) trichloroacetic acid and then with 10% (vol/vol) trichloroacetic acid. The radioactivity was measured with a liquid scintillation counter (Packard) by using a scintillation cocktail (BCS; Amersham).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

Radiolabeled proteins were separated by 2-D electrophoresis according to the method of O'Farrell (29) with the following modifications. Briefly, isoelectrofocusing for the first dimension was performed in precast Immobiline DryStrip with a nonlinear gradient of pH 3 to 10 (Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France). The Immobiline DryStrips were rehydrated overnight with samples containing equal quantities of radioactivity (3.5 × 106 cpm) in 8 M urea, 2 mM tributyl phosphine (TBP), 2% carrier ampholytes (pH 3 to 10; Bio-Rad, Ivry-sur-Seine, France), 2% 3-[(3-cholamidolpropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate, and traces of bromophenol blue. Proteins were first subjected to isoelectric focusing (Multiphor II system; Pharmacia Biotech) for a total of 63.7 kVh. Immobiline DryStrips were first equilibrated for 15 min in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Hcl (pH 6.8), 6 M urea, 30% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 2 mM TBP and then for 15 min in the same buffer with traces of bromophenol blue and 2.5% iodoacetamide instead of TBP. The second dimension was a vertical sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using the buffer system of Laemmli (23). After the second dimension, the gels were fixed overnight in a solution of 10% acetic acid and 40% ethanol and then dried at 65°C for 1 h under vacuum. The gels were exposed to storage phosphor screens (Molecular Dynamics) for 24 h and scanned with a STORM 840 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) at a resolution of 100 dots per inch.

To identify proteins by MS or N-terminal sequencing after 2-D electrophoresis, they were extracted by staining the gels with 0.1% Coomassie blue R-250 in a 40% ethanol-10% acetic acid solution and destaining them in the same solution without Coomasie blue. Each gel was extensively rinsed with distilled water.

Computer-aided analysis of 2-D gels.

Gels were analyzed with Melanie 3 software (Bio-Rad). Each labeling experiment was duplicated, and at least three 2-D gels were run for each experiment. Variations in protein expression were deemed valid if they were observed in at least n−1 gels, n being the number of gels run for each condition, and they were analyzed using Student's t test (confidence level, 0.05), which ensured that only significant changes in the values of protein spots were taken into consideration.

Identification of proteins by MS.

Proteins separated by 2-D electrophoresis were digested in the gel by trypsin (Promega). After extraction, peptides were mixed with a 10-mg/ml solution of alpha-cyano-4-hydroxy cinnamic acid (70% acetonitrile-0.3% trifluoroacetic acid) and placed on the sample plate. The samples were dried and then analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) (MS) (Voyager DE-STR; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). Finally, postsource decay (PSD) was performed to determine the sequence of amino acid residues.

An Internet program, ProFound (http://prowl.rockefeller.edu), was used to search genomic databases. The program uses fragment ion masses (generated by MALDI-TOF [MS]) to search the databases for matches with peptides from known proteins. The following parameters were used in the searches: Firmicutes species, protein molecular mass range from 0 to 3,000 kDa, no restriction of pI, trypsin digest (no missed cleavage allowed), and a fragment ion mass tolerance of ±50 ppm. The protein sequences found with ProFound were used to search protein databases for homologous proteins in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database; however, only a small number of L. monocytogenes proteins are available. To identify other proteins, another software program, Peptide Search, was used, which allowed us to consult a personal database established from the L. monocytogenes genome (14). The molecular masses and isoelectric points of the proteins were computed with another Internet program (http://www.expasy.ch/tools/pi_tool.html).

Identification of proteins by N-terminal microsequencing.

To obtain N-terminal amino acid sequences, selected proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Sequi-Blot PVDF Membrane; Bio-Rad) and microsequenced using an automatic Beckman/Porton LF3000 protein sequencer. Searches for sequence homology were performed with the FASTA program (30).

RESULTS

Conditions for growth and labeling of L. monocytogenes.

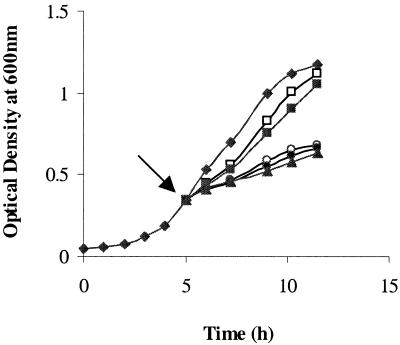

The normal growth of L. monocytogenes strain LO28 in MCDB 202 medium shows an exponential phase with a growth rate of approximately 0.151 h−1 (Fig. 1). When cells are subjected to a severe stress, they usually shut off most metabolic activity and commit themselves to adaptive strategies. Consequently, they enter a physiological state with very little protein synthesis, very different from the normal growth physiology. To obtain a less severe repression of the physiology, a salt concentration which would result in growth rate reduction of 25 to 50% of the unstressed rate was applied. A 3.5% NaCl concentration corresponding to a growth rate of 0.108 h−1 was chosen as a stressing condition. To highlight the proteins synthesized under these conditions, two independent labeling experiments on aliquots of the same culture were carried out. The first was performed 30 min after the passage in saline medium to identify the salt stress proteins; the second was performed between 60 and 90 min after the addition of salt to identify salt acclimation proteins.

FIG. 1.

Growth of the L. monocytogenes LO28 strain without additional NaCl (⧫) or following salt stress at 3 (□), 3.5 (▪), 4 (○), 4.5 (•), and 5% (▴) NaCl at the point indicated by the arrow (optical density at 600 nm, 0.3). The strain was grown in supplemented MCDB 202 medium at 37°C. Each data point shows the mean of five cultures grown independently.

Induction of proteins during salt stress.

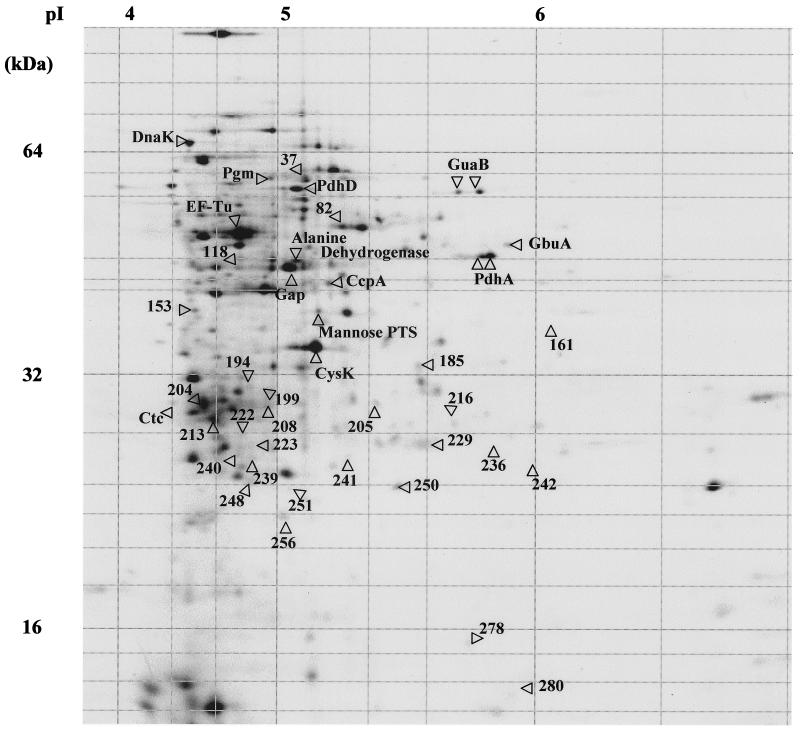

About 400 distinct proteins were analyzed using Melanie 3 software, with molecular masses from 12 to 100 kDa and a pI range from 4 to 7 (Fig. 2). Protein pattern comparisons of exponential cultures with their unstressed counterparts 30 or 90 min after being stressed allowed significant alterations (P < 0.05) to be distinguished in the expression of several proteins (Table 1). Thirty minutes after the salt stress, the synthesis of 26 proteins was modified: 20 proteins showed lower levels of synthesis, and six were overexpressed. One hour after the salt stress, the synthesis of 25 proteins varied: 11 showed a reduction in synthesis, and 9 were expressed at higher rates.

FIG. 2.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis autoradiogram of L. monocytogenes proteins labeled during exponential growth showing identified proteins synthesized in response to salt stress (3.5% NaCl). The reference numbers of individual protein spots correspond to those listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Proteins affected by salt stress identified by 2-D gel electrophoresisa

| Spot no. | Proteinb | Estimated value

|

Inductionc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pI | Mass (kDa) | 0-30 min | 60-90 min | ||

| 13 | DnaK | 4.52 | 66.2 | > | — |

| 36 | Pgm | 4.97 | 57.3 | < | — |

| 37 | 5.10 | 56.9 | < | — | |

| 44 | PdhD | 5.09 | 54.9 | — | > |

| 48 | GuaB | 5.83 | 54.4 | — | > |

| 49 | GuaB | 5.79 | 54.3 | — | > |

| 82 | 5.18 | 46.5 | — | < | |

| 84 | EF-Tu | 4.81 | 45.2 | — | > |

| 97 | GbuA | 5.93 | 43.0 | — | > |

| 105 | PdhA | 5.87 | 47.1 | — | > |

| 106 | PdhA | 5.84 | 47.6 | — | > |

| 109 | Alanine dehydrogenase | 5.09 | 49.0 | > | — |

| 113 | GAPDH | 5.07 | 48.9 | > | — |

| 118 | 4.79 | 48.9 | < | — | |

| 133 | CcpA | 5.12 | 40.5 | — | > |

| 153 | 4.56 | 35.0 | < | — | |

| 155 | Mannose-specific PTS | 5.11 | 34.9 | — | > |

| 161 | 6.10 | 34.4 | — | > | |

| 173 | CysK | 5.11 | 33.1 | > | — |

| 185 | 5.62 | 32.3 | < | < | |

| 194 | 4.86 | 31.4 | — | < | |

| 199 | 4.95 | 31.2 | > | — | |

| 204 | 4.60 | 30.6 | < | — | |

| 205 | 5.38 | 30.7 | < | — | |

| 206 | Ctc | 4.32 | 30.7 | > | — |

| 208 | 4.93 | 30.4 | < | — | |

| 213 | 4.66 | 29.9 | < | < | |

| 216 | 5.78 | 29.7 | < | < | |

| 222 | 4.89 | 29.4 | < | — | |

| 223 | 4.95 | 29.3 | — | < | |

| 229 | 5.64 | 28.8 | < | — | |

| 236 | 5.85 | 28.7 | — | < | |

| 239 | 4.88 | 28.3 | < | < | |

| 240 | 4.78 | 28.4 | — | > | |

| 241 | 5.21 | 28.3 | < | < | |

| 242 | 6.01 | 28.1 | < | < | |

| 248 | 4.86 | 26.8 | < | < | |

| 250 | 5.50 | 26.4 | < | — | |

| 251 | 5.06 | 26.2 | — | < | |

| 256 | 5.04 | 23.7 | < | < | |

| 278 | 5.81 | 15.1 | < | — | |

| 280 | 6.00 | 13.5 | < | < | |

Proteins listed are shown in Fig. 2.

Proteins were identified by MS or N-terminal microsequencing.

Synthesis relative to prestress. >, enhanced; <, reduced; —, no change.

Identification of salt stress proteins by MALDI-TOF.

The tryptic peptide masses were compared in ProFound to the National Center for Biotechnology Information database with minimal restricted search parameters. Spots 13, 84, 97, and 133 were identified as similar to a heat shock protein (DnaK), an elongation factor (EF-Tu), a transporter of glycine betaine (GbuA), and a catabolite control protein (CcpA) of L. monocytogenes, respectively (Table 2). The estimated values of pIs and molecular masses by 2-D electrophoresis were in agreement with those of the identified proteins. In addition, the Z score, which is the probability that a candidate protein in a database search is the protein being analyzed (computed by ProFound software), confirmed the correct identification.

TABLE 2.

Proteins identified from 2-D gel electrophoresis of L. monocytogenes by MS with ProFound software

| Spot no. | Name (NCBI accession no.) | Mass (kDa) | Peptide MH+ (Da)a | Δ in mass (ppm) | Start-end positions | Peptide sequence of matched fragment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | DnaK (NCBI 10719987) | 66.2 | 757.439 | −7 | 451-457 | NGIVTVR |

| 885.491 | −1 | 134-141 | IAGLEVER | |||

| 934.523 | 12 | 35-43 | TTPSVVGFK | |||

| 965.534 | 6 | 26-34 | IIPNPEGAR | |||

| 1,209.666 | 1 | 206-215 | IIDYLVAEFK | |||

| 1,223.686 | 17 | 427-437 | FQLADIPPAPR | |||

| 1,328.732 | 2 | 56-68 | AAITNPNTISSIK | |||

| 1,362.676 | −1 | 507-518 | NNADQLVFTVDK | |||

| 1,372.682 | 14 | 275-285 | FDELTHDLVER | |||

| 1,459.752 | 2 | 438-450 | GIPQIEVSFDIDK | |||

| 1,488.676 | 10 | 99-111 | SYAEDYLGETVDK | |||

| 1,563.838 | 21 | 112-125 | AVITVPAYFNDAQR | |||

| 1,879.976 | −8 | 83-98 | DYSPQEISAIILQYLK | |||

| 2,030.048 | 10 | 296-315 | DANLSASDIDQVILVGGSTR | |||

| 2,127.127 | −7 | 4-25 | IIGIDLGTTNSAVAVLEGGEAK | |||

| 2,910.393 | −12 | 393-419 | SQTFSTAADNQPAVDIHVLQGERPMAK | |||

| 84 | EF-Tu (NCBI 11612456) | 30.45 | 866.506 | 11 | 18-24 | EHILLSR |

| 1,135.621 | 14 | 155-164 | VVVTGVEMFR | |||

| 1,216.571 | 0 | 78-88 | ALQGEADWEAK | |||

| 1,492.763 | −32 | 25-37 | QVGVPYIVVFMNK | |||

| 1,702.908 | 11 | 166-181 | LLDYAEAGDNIGALLR | |||

| 1,976.953 | 7 | 89-105 | IDELMEAVDSYIPTPER | |||

| 2,032.985 | 8 | 221-235 | HTPFFNNYRPQFYFR | |||

| 2,184.031 | 4 | 106-124 | DTDKPFMMPVEDVFSITGR | |||

| 97 | GbuA (NCBI 4760363) | 43.61 | 757.427 | −8 | 98-103 | ELLEVR |

| 988.567 | 50 | 36-45 | ETGATIGVNK | |||

| 1,084.571 | 18 | 230-238 | IGDHIMIMR | |||

| 1,350.715 | −26 | 315-327 | ELVGIVHAAEVSK | |||

| 1,382.713 | −1 | 331-342 | ENITSLETALHR | |||

| 1,655.887 | 0 | 216-229 | TIIFITHDLDEALR | |||

| 1,773.853 | 12 | 106-120 | SMSMVFQNFGLFPNR | |||

| 2,109.072 | −9 | 272-289 | VYTASNVMIRPEIVNFEK | |||

| 2,512.238 | −10 | 177-199 | ALANNPDILLMDEAFSALDPLNR | |||

| 2,568.203 | −12 | 239-62 | DGSVVQTGSPEEILAHPANEYVEK | |||

| 2,980.397 | −12 | 143-171 | NAAESLALVGLAGYGDQYPSQLSGGMQQR | |||

| 133 | CcpA (NCBI 3659700) | 36.95 | 927.442 | −3 | 221-228 | YNYNAGVK |

| 1,022.575 | 0 | 318-326 | TVILPHSEK | |||

| 1,055.558 | 28 | 154-162 | FASVNIDYK | |||

| 1,179.573 | 34 | 308-317 | LMTSEEVDEK | |||

| 1,180.595 | 4 | 1-10 | MNVTIYDVAR | |||

| 1,279.641 | 15 | 116-126 | QVDGIIYMGER | |||

| 1,392.671 | 14 | 127-137 | ISEQLQEEFDR | |||

| 1,596.782 | −22 | 138-153 | SPAPVVLAGAVDMENK | |||

| 1,629.852 | 3 | 179-193 | QIAFVSGSLNEPVNR | |||

| 1,897.051 | −1 | 37-53 | VLDVINQLGYRPNAVAR | |||

| 2,278.231 | 5 | 60-80 | TTTVGVIIPDISNVFYAELAR |

Values indicate monoisotopic masses.

Currently, only 100 proteins of L. monocytogenes are available in the databases on the Internet, which limits identification. Nevertheless, another software package, Peptide Search, allows us to search in personal databases. The complete sequence of L. monocytogenes permitted the creation of a database of L. monocytogenes peptide masses. By this method, spots 36, 44, 48-49, 109, 155, and 206 were similar to a phosphoglycerate mutase (Pgm), a pyruvate dehydrogenase (PdhD), an inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (GuaB), an alanine dehydrogenase, a homolog of mannose-specific phosphotransferase system (PTS) enzyme IIAB, and a general stress protein (Ctc), respectively (Table 3). Verification of these results was not possible, as the Z scores were unknown, so sequence information of selected tryptic peptides was obtained using MALDI-PSD. This information, in conjunction with the mass fingerprints of the proteins obtained by MALDI-TOF (MS) analysis, confirmed the identification of three proteins, spots 36, 48-49, and 206, as Pgm, GuaB, and Ctc, respectively (Table 4). Using MS, spot 48 gave the same result as 49; the same thing was observed for spots 105 and 106. This was not surprising, since digestion of these proteins by trypsin gave peptides having approximately the same masses. The masses of the proteins 48 and 49 were 54.4 and 54.3 kDa, respectively, and those of 105 and 106 were 47.1 and 47.6 kDa, respectively. It was therefore concluded that spots 48 and 49 were the same protein. Similarly, spots 105 and 106 were the same protein. For each pair, the two spots are different isoforms of the same protein, where the proteins could be desaminated, phosphorylated, or modified by chemical groups which shift the protein isoelectric point toward an acidic pH.

TABLE 3.

Proteins identified from 2-D gel electrophoresis of L. monocytogenes by MS with Peptide Search software

| Spot no. | Protein (accession no.a) | Peptide MH+ (Da)b | Δ in mass (ppm) | Start-end positions | Peptide sequence of matched fragment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | Pgm (LMO02456) | 928.572 | −1 | 316-323 | VVDLILEK |

| 979.558 | 12 | 73-80 | IVYQSLTR | ||

| 1004.423 | 28 | 274-280 | EWDHFDR | ||

| 1089.583 | −12 | 212-220 | FEDPIELVK | ||

| 1116.580 | −4 | 95-104 | ALNNAFTHTK | ||

| 1293.596 | 25 | 84-94 | AIEEGEFQENK | ||

| 1304.675 | 26 | 142-152 | NVYIHAFLDGR | ||

| 1329.778 | −4 | 3-15 | SPVAIIILDGFGK | ||

| 1362.648 | 11 | 35-45 | YWADFPHGELK | ||

| 1431.752 | 12 | 387-399 | KPAEMTGESLIQK | ||

| 1555.877 | 0 | 372-386 | LADVAPTMLDLLGVK | ||

| 1607.839 | 29 | 169-184 | AISDLNYGAIATVSGR | ||

| 1725.835 | 10 | 249-262 | DNDAVIFFNFRPDR | ||

| 1820.928 | 10 | 153-168 | DVAPQSSLEYLETLQK | ||

| 1901.947 | 24 | 17-34 | AETVGNAVAQANKPNFDR | ||

| 2607.259 | −5 | 46-72 | AAGLDVGLPEGQMGNSEVGHTNIGAGR | ||

| 44 | PdhD (LMO01055) | 851.416 | −5 | 380-387 | FPFGGNGR |

| 880.537 | −3 | 57-64 | ALITIGHR | ||

| 972.537 | 6 | 331-340 | IAAEAIAGEK | ||

| 1274.675 | −14 | 388-399 | ALSLDAPEGFVR | ||

| 1626.845 | −26 | 275-289 | RPNTDEIGLEQAGVK | ||

| 1629.896 | −18 | 11-27 | DTIVIGAGPGGYVAAIR | ||

| 1993.933 | −37 | 112-128 | VEMLEGEAFFVDDHSLR | ||

| 2148.182 | −3 | 304-324 | SNVSNIFAIGDIVPGVPLAHK | ||

| 48-49 | GuaB (LMO02758) | 705.372 | 16 | 482-488 | MTGAGLR |

| 745.440 | −7 | 78-84 | MAIAIAR | ||

| 821.416 | 2 | 475-481 | EEAAFVR | ||

| 885.552 | 4 | 153-160 | LVGILTNR | ||

| 969.537 | 5 | 432-440 | LVPEGIEGR | ||

| 1004.542 | −31 | 226-234 | VIEFPNSAK | ||

| 1167.699 | −6 | 205-215 | LPLVDEAGILK | ||

| 1189.683 | −2 | 308-318 | ALFEVGVDIVK | ||

| 1240.563 | 21 | 460-471 | SGMGYTGSPDLR | ||

| 1541.829 | 24 | 292-307 | DVVIVAGNVATAEGAR | ||

| 1544.880 | 24 | 445-459 | GSVADIIFQLVGGIR | ||

| 2400.289 | −4 | 259-282 | LIEAGVDAIVIDTAHGHSAGVINK | ||

| 3001.477 | −12 | 110-136 | SESGVIIDPFYLTPDHQVFAAEHLMGK | ||

| 3050.456 | −27 | 372-402 | ALAAGGNAVMLGSMLAGTDESPGETEIFQGR | ||

| 109 | Alanine dehydrogenase (LMO01579) | 1191.572 | −31 | 63-72 | EAWDVDMVVK |

| 1333.705 | −17 | 139-150 | MAAQIGAQFLQR | ||

| 1347.647 | 1 | 75-85 | EPIASEYTYFK | ||

| 1394.707 | 4 | 342-353 | GLNTYQGHITYK | ||

| 1494.733 | 4 | 354-367 | AVADSLDLPYTDSK | ||

| 1556.865 | −4 | 168-184 | SEVVIIGGGIAGTNAAK | ||

| 1612.848 | −11 | 151-167 | TNGGMGVLLGGVPGVER | ||

| 1647.932 | 1 | 308-323 | TSTLALTNATLPFGLK | ||

| 1713.957 | 8 | 185-201 | IAAGLGANVTILDMNLK | ||

| 1814.938 | −12 | 291-307 | YGVLHYAVANMPGAVPR | ||

| 1926.883 | 0 | 38-56 | DAGIGSNYQDADFVQAGAK | ||

| 1969.051 | −15 | 324-341 | LANQGLEAAVQNDPFLLR | ||

| 2143.180 | −11 | 86-104 | EGLLLFTYLHLANEPTLAK | ||

| 155 | Mannose-specific PTS (LMO00096) | 877.515 | −3 | 155-161 | IEFVLTR |

| 1122.652 | 17 | 200-210 | LIEQAAPPGVK | ||

| 1324.738 | 30 | 166-177 | LLHGQVATAWTK | ||

| 1527.854 | −21 | 233-245 | ALLLFENPQDVLR | ||

| 1548.722 | 4 | 246-267 | AIEGGVEIEQVNVGSMAHSVGK | ||

| 2211.108 | −3 | 106-127 | FTMESAHEIAANILAPAQEGVR | ||

| 2371.172 | 10 | 128-154 | VKPEELQPQVTATEQPQAEIAAVGDGK | ||

| 206 | Ctc (LMO00211) | 1009.572 | −12 | 26-34 | VPGIIYGYK |

| 1053.631 | −19 | 105-115 | VVLVGDAPGVK | ||

| 1187.566 | 34 | 10-19 | ETTQHSEVTR | ||

| 1377.785 | −6 | 116-128 | AGGVLQQIIHDVK | ||

| 1628.875 | 7 | 35-49 | SENVPVSVDSLELIK | ||

| 2021.930 | −6 | 182-200 | AEEEPTTTEAPEPEAVHGK | ||

| 2121.035 | 14 | 163-181 | DYVVQAEEEETVVTVSAPR |

Accession numbers of the open reading frames encoding the proteins from the L. monocytogenes genome database of the Institut Pasteur (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/ListiList).

MH+, the protonated mass, i.e., mass + 1 Da. Values indicate monoisotopic masses.

TABLE 4.

Peptide sequences of proteins identified from 2-D gel electrophoresis of L. monocytogenes

| Spot no. | Protein | Accession no.a | Mode of identification | Peptide sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | Pgm | LMO02456 | Maldi-PSD | IFFNFRPDc |

| 44 | PdhD | LMO01055 | Edman degradation | (Q or S)VGDFPEb |

| 48-49 | GuaB | LMO02758 | Maldi-PSD | LAAAAVGITNDTFVc |

| IIFQLVGGIc | ||||

| 105-106 | PdhA | LMO01052 | Edman degradation | ASXTKKAb |

| 109 | Alanine dehydrogenase | LMO01579 | Edman degradation | XLVGVPNb |

| 113 | Gap | LMO02459 | Edman degradation | TVKVGINb |

| 155 | Mannose-specific PTS | LMO00096 | Edman degradation | MXGIXLAb |

| 173 | CysK | Edman degradation | TIANSITb | |

| 206 | Ctc | LMO00211 | Edman degradation | ATTLEVQb |

| Maldi-PSD | YVVQAEEEETVVTVSAc |

Accession numbers of the open reading frames encoding the proteins from the L. monocytogenes genome database of the Institut Pasteur (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/ListiList).

N-terminal amino acid sequence.

Internal peptides mapped.

Identification of proteins by N-terminal amino acid sequence determination.

To identify or to confirm the identification of some proteins, N-terminal sequencing was performed. Proteins corresponding to spots 44, 109, 155, and 206 were confirmed to be similar to PdhD, an alanine dehydrogenase, a homolog of mannose-specific PTS enzyme IIAB, and Ctc, respectively. This technique enabled identification of the spots 105-106, 113, and 173 as being similar to a pyruvate dehydrogenase (PdhA), a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gap), and CysK, respectively (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the pattern of protein synthesis after salt stress in L. monocytogenes was analyzed by 2-D gel electrophoresis, and the identities of 12 salt stress-induced proteins were determined by microsequencing and MS. The identified proteins belong to two groups: the salt shock proteins (Ssp), which are rapidly but transiently overexpressed (19), and the stress acclimation proteins (Sap), which are more or less rapidly induced but still overexpressed several hours after the downshifts. For example, these two groups of proteins were described in response to cold shock in L. monocytogenes and in Pseudomonas fragi (2, 27).

Our experiment revealed that in L. monocytogenes, six Ssp proteins were induced. Among these proteins, two general stress proteins (Gsp), DnaK and Ctc, were identified. DnaK, a heat shock protein, is required for stress tolerance, and it stabilizes cellular proteins (17). The synthesis of DnaK also increased after salt stress in Lactococcus lactis and Enterococcus faecalis (9, 19). However, the contrary was observed for B. subtilis (36), but in the latter study the labeling was performed only 10 to 20 min after the addition of salt. Using this labeling period, Kilstrup et al. (19) suggested the increased synthesis of DnaK may have been missed if the kinetics of its synthesis were similar to those in L. lactis, as the synthesis rate had resumed the preshift level between 10 and 15 min after the stress. Ctc is induced in B. subtilis in response to various stresses, such as salt stress, and its function is unknown (18, 36). Three other overexpressed salt shock proteins belonged to the general metabolism. First, an alanine dehydrogenase has been identified which presently does not seem to be involved in any other stress response (33). The second protein, CysK, is needed for cysteine biosynthesis and is induced after cold and oxidative stresses in B. subtilis (1, 16). The last identified protein is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gap), an enzyme of glycolysis whose synthesis increased in B. subtilis during the 30 min following cold stress. However, after saline stress, no change in the rate of synthesis of this enzyme was observed, either in B. subtilis or in L. lactis (16, 19, 39). Because of the increase in the relative synthesis of an alanine dehydrogenase, CysK, and Gap, it appears that the synthesis of amino acids and the production of pyruvate, which is necessary for acetyl-coenzyme A synthesis, one of the key components of the Krebs cycle, are of considerable importance after salt stress.

Only one of the 20 proteins repressed during the first 30 min following salt stress was identified; this was a phosphoglycerate mutase (Pgm), an enzyme of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis in B. subtilis (24). To our knowledge, no decrease in the synthesis of Pgm has been described in response to any stress. This decreased synthesis could be related to the increasing synthesis of Gap, in order to compensate for the increasing amount of phosphoglycerate produced, but no clear explanation of these contradictory effects is possible at present.

In the present study, 11 Sap proteins were detected, and 7 of them were identified. The first is GbuA (a subunit of the glycine betaine transport system GbuABC), which is an osmoprotectant transporter accumulated in response to salt stress by L. monocytogenes and many bacteria, such as B. subtilis (12). The examination of the deduced amino acid sequence of GbuA revealed 60% identity to the equivalent protein, OpuAA, from B. subtilis, which is also induced by salt shock (20, 31). The second is an elongation factor (EF-Tu) whose synthesis rate increased in Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the presence of a high iron concentration (38). It has been suggested that in Escherichia coli, EF-Tu, in addition to its function in translation elongation, might be implicated in protein folding and/or protection from stress (5). Salt stress also induced higher levels of GuaB, which shows a similar induction after superoxide stress in B. subtilis (1). The overexpression of GuaB in L. monocytogenes could reflect a particular need for purines in surviving cells where DNA is being repaired, as after peroxide shock in B. subtilis (1). Some induced Sap proteins were related to glycolysis. The catabolite control protein (CcpA), which controls the pathways of carbon catabolism, is a regulator of glycolysis in several microorganisms (3, 25, 35) and is induced after cold stress in L. lactis (39). A homolog of mannose-specific PTS enzyme IIAB and two pyruvate dehydrogenase subunits (PdhA and PdhD) were also identified.

Finally, the results observed agreed well with the fact that acclimation of L. monocytogenes to NaCl influences general metabolism and many metabolic pathways. For instance, the overexpression of EF-Tu, which has a protective influence on newly produced proteins, is probably important in protein folding and protein renaturation after stress (5). Overproduction of CcpA, the mannose-specific PTS enzyme IIAB, and the two pyruvate dehydrogenase subunits (PdhA and PdhD) is probably related to metabolic pathways providing energy. As a matter of fact, the Krebs cycle and sugar metabolism may be major sources of ATP for the bacterial cell and, in the present study, for stressed L. monocytogenes cells.

It is interesting that the accumulation of glycine betaine has been found to be important in L. monocytogenes tolerance to both osmotic and chill stresses. Our results indicate that among the salt stress-induced proteins identified, four proteins (DnaK, CysK, CcpA, and Gap) are overexpressed after cold stress in other bacteria (32). Such results support hypothesized similar mechanisms of regulation in the adaptations to salt and cold stresses. Further work is required to better define the extent of the overlap between cold and salt stress adaptation in L. monocytogenes.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that one protein, GbuA, overexpressed in the presence of salt, is directly connected to the salt stress response. This response is also connected with general stress response, as two Gsp proteins (DnaK and Ctc) were induced after salt stress. In addition, because the synthesis of Gap, PdhA, PdhD, and Pgm is modified in the presence of salt, it appears that glycolysis is important after this stress. These proteins may represent vital enzymes that are rather salt sensitive and whose production is necessary to keep up a minimal level of catabolic metabolism. As for the other salt stress proteins identified in L. monocytogenes, it also apparent that they have a broad spectrum of functions. These observations reveal that the salt stress response is a rather complex process which remains to be elucidated by understanding the detailed function of the Ssp and Sap proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rozenn Gardan for critically reviewing the manuscript and for stimulating and helpful discussions. We are grateful to Christian Beauvallet for his technical help in MS, Ana Paula Teixeira-Gomes for assistance in N-terminal amino acid sequencing, and Tania Ngapo for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Région Auvergne, France.

We also thank the European Listeria Genome Consortium, composed of Philippe Glaser, Alexandra Amend, Fernando Baquero-Mochales, Patrick Berche, Helmut Bloecker, Petra Brandt, Carmen Buchrieser, Trinad Chakraborty, Alain Charbit, Elisabeth Couvé, Antoine de Daruvar, Pierre Dehoux, Eugen Domann, Gustavo Dominguez-Bernal, Lionel Durant, Karl-Dieter Entian, Lionel Frangeul, Hafida Fsihi, Francisco Garcia del Portillo, Patricia Garrido, Werner Goebel, Nuria Gomez-Lopez, Torsten Hain, Joerg Hauf, David Jackson, Jurgen Kreft, Frank Kunst, Jorge Mata-Vicente, Eva Ng, Gabriele Nordsiek, José Claudio Perez-Diaz, Bettina Remmel, Matthias Rose, Christophe Rusniok, Thomas Schlueter, José-Antonio Vazquez-Boland, Hartmut Voss, Jurgen Wehland, and Pascale Cossart.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antelmann, H., J. Bernhardt, R. Schmid, H. Mach, U. Völker, and M. Hecker. 1997. First steps from a two-dimensional protein index towards a response-regulation map for Bacillus subtilis. Electrophoresis 18:1451-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayles, D. O., B. A. Annous, and B. J. Wilkinson. 1996. Cold stress proteins induced in Listeria monocytogenes in response to temperature downshock and growth at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1116-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behari, J., and P. Youngman. 1998. A homolog of CcpA mediates catabolite control in Listeria monocytogenes but not carbon source regulation of virulence genes. J. Bacteriol. 180:6316-6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beumer, R. R., M. C. Te Giffel, L. J. Cox, F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 1994. Effect of exogenous proline, betaine, and carnitine on growth of Listeria monocytogenes in a minimal medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1359-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caldas, T. D., A. El Yaagoubi, and G. Richarme. 1998. Chaperone properties of bacterial elongation factor EF-Tu. J. Biol. Chem. 273:11478-11482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csonka, L. N., and A. D. Hanson. 1991. Prokaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 45:569-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dartois, V., M. Débarbouillé, F. Kunst, and G. Rapoport. 1998. Characterization of a novel member of the DegS-DegU regulon affected by salt stress in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:1855-1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esvan, H., J. Minet, C. Laclie, and M. Cormier. 2000. Protein variations in Listeria monocytogenes exposed to high salinities. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 55:151-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flahaut, S., A. Hartke, J. C. Giard, A. Benachour, P. Boutibonnes, and Y. Auffray. 1996. Relationship between stress response towards bile salts, acid and heat treatment in Enterococcus faecalis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 138:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonnesbech Vogel, B., H. H. Huss, B. Ojeniyi, P. Ahrens, and L. Gram. 2001. Elucidation of Listeria monocytogenes contamination routes in cold-smoked salmon processing plants detected by DNA-based typing methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2586-2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gellin, B. G., and C. V. Broome. 1989. Listeriosis. JAMA 261:1313-1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerhardt, P. N., L. Tombras Smith, and G. M. Smith. 2000. Osmotic and chill activation of glycine betaine porter II in Listeria monocytogenes membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 182:2544-2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerth, U., E. Krüger, I. Derré, T. Msadek, and M. Hecker. 1998. Stress induction of the Bacillus subtilis clpP gene encoding a homologue of the proteolytic component of the Clp protease and the involvement of ClpP and ClpX in stress tolerance. Mol. Microbiol. 28:787-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couve, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Dominguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durant, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. G. Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gomez-Lopez, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueno, A. Maitournam, J. M. Vicente, E. Ng, H. Nedjari, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Perez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnanou Besse, N., F. Dubois Brissonnet, V. Lafarge, and V. Leclerc. 2000. Effect of various environmental parameters on the recovery of sublethally salt-damaged and acid-damaged Listeria monocytogenes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89:944-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graumann, P., K. Schröder, R. Schmid, and M. A. Marahiel. 1996. Cold shock stress-induced proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:4611-4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hebraud, M., and J. Guzzo. 2000. The main cold shock protein of Listeria monocytogenes belongs to the family of ferritin-like proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilden, I., B. N. Krath, and B. Hove-Jensen. 1995. Tricistronic operon expression of the genes gcaD (tms), which encodes N-acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate uridyltransferase, prs, which encodes phosphoribosyl diphosphate synthetase, and ctc in vegetative cells of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:7280-7284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilstrup, M., S. Jacobsen, K. Hammer, and F. K. Vogensen. 1997. Induction of heat shock proteins DnaK, GroEL, and GroES by salt stress in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1826-1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko, R., and L. T. Smith. 1999. Identification of an ATP-driven, osmoregulated glycine betaine transport system in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4040-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko, R., L. Tombras Smith, and G. M. Smith. 1994. Glycine betaine confers enhanced osmotolerance and cryotolerance on Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 176:426-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunst, F., and G. Rapoport. 1995. Salt stress is an environmental signal affecting degradative enzyme synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:2403-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyva-Vazquez, M. A., and P. Setlow. 1994. Cloning and nucleotide sequences of the genes encoding triose phosphate isomerase, phosphoglycerate mutase, and enolase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 176:3903-3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahr, K., W. Hillen, and F. Titgemeyer. 2000. Carbon catabolite repression in Lactobacillus pentosus: analysis of the ccpA region. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:277-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClure, P. J., T. A. Roberts, and P. O. Oguru. 1989. Comparison of the effects of sodium chloride, pH and temperature on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes on gradient plates and liquid medium. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 9:95-99. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michel, V., I. Lehoux, G. Depret, P. Anglade, J. Labadie, and M. Hebraud. 1997. The cold shock response of the psychrotrophic bacterium Pseudomonas fragi involves four low-molecular-mass nucleic acid-binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 179:7331-7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Driscoll, B., C. G. Gahan, and C. Hill. 1996. Adaptive acid tolerance response in Listeria monocytogenes: isolation of an acid-tolerant mutant which demonstrates increased virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1693-1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Farrell, P. H. 1975. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 250:4007-4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearson, W. R., and D. J. Lipman. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:2444-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersohn, A., M. Brigulla, S. Haas, J. D. Hoheisel, U. Volker, and M. Hecker. 2001. Global analysis of the general stress response of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:5617-5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salotra, P., D. K. Singh, K. P. Seal, N. Krishna, H. Jaffe, and R. Bhatnagar. 1995. Expression of DnaK and GroEL homologs in Leuconostoc mesenteroides in response to heat shock, cold shock or chemical stress. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 131:57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siranosian, K. J., K. Ireton, and A. D. Grossman. 1993. Alanine dehydrogenase (ald) is required for normal sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:6789-6796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith, L. T. 1996. Role of osmolytes in adaptation of osmotically stressed and chill-stressed Listeria monocytogenes grown in liquid media and on processed meat surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3088-3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobisch, S., D. Zühlke, J. Bernhardt, J. Stülke, and M. Hecker. 1999. Role of CcpA in regulation of the central pathways of carbon catabolism in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:6996-7004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Völker, U., S. Engelmann, B. Maul, S. Riethdorf, A. Völker, R. Schmid, H. Mach, and M. Hecker. 1994. Analysis of the induction of general stress proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 140:741-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker, S. J., P. Archer, and J. G. Banks. 1990. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes at refrigeration temperatures. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 68:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong, D. K., B. Y. Lee, M. A. Horwitz, and B. W. Gibson. 1999. Identification of Fur, aconitase, and other proteins expressed by Mycobacterium tuberculosis under conditions of low and high concentrations of iron by combined two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Infect. Immun. 67:327-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wouters, J. A., H. H. Kamphuis, J. Hugenholtz, O. P. Kuipers, W. M. de Vos, and T. Abee. 2000. Changes in glycolytic activity of Lactococcus lactis induced by low temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3686-3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]