Abstract

Background:

Irritability comprises a set of behaviors that span normal:abnormal proneness to anger. When dysregulated and developmentally atypical, irritability indicates neurodevelopmental vulnerability for mental health problems. Yet, mental health risk indicators such as irritability likely present differently during specific developmental stages, especially across the crucial transition from preschool to early school age, when the presence of sustained elevated irritability predicts psychiatric disorders, increased impairment, and service use in school-age children. The goal of this study is to chart how behavioral manifestations of irritability unfold and shift across the developmental transition from preschool to early school age and identify key irritability behaviors that are most strongly predictive of other irritability behaviors in the next developmental stage.

Methods:

The sample was drawn from the Multidimensional Assessment of Preschoolers Study (MAPS, N=382), a diverse early childhood sample enriched for psychopathology via oversampling for disruptive behavior and family violence exposure. Objective frequency of normative to severe irritability captured as tantrum features and irritable mood across contexts were longitudinally measured at preschool- (Mage=4.49 years, SD=0.83) and early school-age (Mage=7.08, SD=0.94) using the developmentally specified Multidimensional Assessment Profile Scales-Temper Loss. A cross-lagged panel network was estimated to depict the longitudinal predictive connections between individual irritability items from preschool to early school age.

Results:

The strongest cross-lagged association was hit/bit/kick during a tantrum at preschool predicting tantrums in normative contexts at early school age. Severe tantrum behaviors (e.g., hit/bite/kick) and difficulty recovering from anger/tantrums at preschool age are key irritability behaviors that predict the development of widespread irritability features in early school age, including severity and length of tantrums, tantrums across contexts, and irritable mood expressions. As development unfolds, severe and violent irritable behaviors in preschool age influence a wide range of less dysregulated irritable behaviors, yet expressed at developmentally abnormally high frequencies, during early school age.

Conclusions:

Highlighting the central behavioral indicators of irritability and how expressions change over the crucial transition from preschool to early school age can inform pragmatic clinical screening measures to identify children who experience high levels of key irritability behaviors (i.e., severe tantrums or difficulty recovering from anger or tantrums in preschool-age) and novel interventions to target these behaviors and interrupt the clinical cascade toward entrenched psychiatric disorders.

Introduction

One of the key tenets – and measurement challenges – in developmental psychology is heterotypic continuity (Jung & Kim, 2023), which describes a phenomenon where underlying constructs (e.g., neurodevelopmental vulnerability to psychopathology) that remain constant may manifest differently as individuals develop. Capturing how behavioral manifestations of underlying neurodevelopmental vulnerability, i.e., susceptibility to environmental stressors or genetic predisposition to psychopathology, morph in their presentation through key developmental transitions is crucial to identifying mental health risk (Marquand et al., 2019; Mittal & Wakschlag, 2017). Elevated irritability, which comprises a set of dysregulated, severe, frequent and/or developmentally unexpectable tantrum behaviors and mood features (Wiggins et al., 2018), is one of the most common manifestations of underlying neurodevelopmental vulnerability to psychopathology (Leibenluft & Stoddard, 2013). Elevated irritability is a robust transdiagnostic predictor of psychopathology (Wiggins, Roy, et al., 2023), and when present in preschool-age (3-6 years), predicts later psychiatric disorders, increased impairment, and use of services in school-age children (Dougherty et al., 2015; Wiggins et al., 2018). Moreover, elevated irritability is one of the most common reasons families seek pediatric psychiatric evaluation (Mikita & Stringaris, 2013; Peterson et al., 1996) and is a major public health concern (Stringaris et al., 2018). The transdiagnostic nature of irritability, cutting across both internalizing and externalizing disorders (Vidal-Ribas et al., 2016), makes it an optimal target for large-scale screening of risk for common psychological, behavioral, and emotional disorders (Vidal-Ribas et al., 2016; Wakschlag et al., 2019). Thus, it is crucial to characterize how the behavioral manifestations of irritability evolve over development to mitigate these negative effects.

Several studies examining the developmental trajectories of irritability found that most children experience low irritability levels that stay stable over time or, if they do have elevated irritability in preschool age, that irritability decreases as they age. However, some children experience an increase in irritability or persistently elevated irritability across preschool to early school age (e.g., Ezpeleta et al, 2015, Paggliaccio et al, 2018, Dugre & Potvin, 2020), which is associated with a higher likelihood of psychiatric diagnoses later in life, such as mood disorders, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and self-harm behaviors (Paggliaccio et al, 2018; Srinivasan, et al, 2024). While some levels of mild irritability behaviors, such as tantrums in expectable contexts, are developmentally normative, these same behaviors may be indicative of clinically significant problems when occurring at a high frequency or at a later developmental stage. Severe and violent tantrums behaviors are often suggestive of abnormal irritability even if in low frequency (Wakschlag et al., 2012).

There have been recent measurement advances to meet the need for developmentally specific characterization of irritability, including the Multidimensional Assessment Profile Scales-Temper Loss (MAPS-TL), a well-validated developmentally-sensitive questionnaire that utilizes a dimensional continuum to measure several behavioral manifestations of irritability, ranging from behaviors developmentally expected to those suggestive of psychopathology (Wakschlag et al., 2012). Originally developed for preschool-age children, the MAPS-TL includes multiple developmentally-specific versions: infant-toddlerhood (Krogh-Jespersen et al., 2022), early school-age (Hirsch et al., 2023), and preadolescence-adolescence (Alam et al., 2023; Kirk et al., 2023). To assess irritability, all MAPS-TL versions include 22 core items that remain the same across development (with only minor changes), such as “lose temper or have a tantrum with a parent” as well as additional, age-specific items for each developmental period (e.g., “have a temper tantrum when asked to stop playing and do something else” for the Toddler version. These core items were found to be relevant to irritability across these developmental stages (Wiggins, Roy, et al., 2023), which provides the opportunity for tracking the changes and stability of specific behaviors over time. Yet, while such developmentally validated measurement exists for each age period separately, it is unclear how these specific behaviors relate to each other across ages, particularly during critical developmental transitions when children experience changes in their social-developmental contexts and expectations such as the preschool to early school period.

As a first step to link differing manifestations of irritability across age periods, the present study aimed to characterize shifts from preschool to early school age, a transition period marked by rapid development in cognitive and social-emotional skills as well as changes in academic, social, and family expectations (Likhar et al., 2022; Miguel et al., 2019). Understanding shifts during this transition is important, as there is strong evidence suggesting irritability persisting into early school age is associated with widespread, detrimental effects in adolescence and beyond (Wiggins et al., 2018). Here, we leveraged a well-characterized longitudinal sample, which allows for measurement of multifaceted irritability features at preschool and school age, and employed a novel network analysis technique to examine how these behaviors unfold and develop over time, allowing us to capture the temporal relationship between individual irritability behaviors and potential symptom “evolution” from a developmental perspective (Wysocki et al., 2022). While previous studies have highlighted the significance of screening for early irritability, the current study further advances this line of research by pinpointing key irritable behaviors that lead to continued irritability as children age across the transition to school. These key irritable behaviors may be leveraged as targets for prevention programs. Based on prior literature on the normal:abnormal spectrum of irritability, we hypothesized that behaviors uncommon or atypical in preschool-age participants due to severity (Wakschlag et al., 2012), such as staying angry for a long time and hitting/biting/kicking during a tantrum, would be more strongly predictive of other irritability symptoms at early school age.

Methods

Participants

The current study used a sample drawn from the Multidimensional Assessment of Preschoolers Study (MAPS), a large-scale study enriched for children from diverse backgrounds who exhibit disruptive behaviors. Procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00025235, STU00083564). Mothers of children recruited from the greater Chicago area completed the assessment battery at the preschool- (Mage=4.49 years, SD=0.83) and early school- (Mage=7.08, SD=0.94) age time points.

Among those who enrolled in the study, 473 of 497 participants at preschool age baseline and 402 at school age follow-up had complete data for the MAPS-TL. The longitudinal sample consisted of 382 participants with complete MAPS-TL data across the two time points. Because network analysis requires complete data, the participants with missing data were excluded from analyses. Included vs. excluded participants did not differ in gender (χ2= 3.30, df = 1, p = .07), race/ethnicity (χ2= 4.32, df = 3, p = .21), poverty status (χ2= 0.002, df = 1, p > .99), or parental education (χ2= 2.80, df = 6, p = .73). The included participants were on average 3 months younger than the excluded participants younger (t = 2.39, df = 145.25, p = .018). Sample demographics are in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Information of Analytic Sample.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 179 (46.9) |

| Female | 203 (53.1) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 183 (47.9) |

| White | 87 (22.8) |

| Hispanic | 106 (27.7) |

| Other | 6 (1.6) |

| Parental Education | |

| Less than high school | 13 (3.4) |

| High school/GED | 79 (20.7) |

| Some college | 121 (31.7) |

| Associates | 61 (16.0) |

| Bachelors | 59 (15.4) |

| Graduates | 42 (11.0) |

| Missing | 7 (1.8) |

| Poverty | |

| Not poor | 205 (53.7) |

| Poor | 177 (46.3) |

Note: Poverty status was determined using federal poverty guidelines based on annual household income and household size, as well as receipt of TANF services.

Measures

The MAPS-TL (Wakschlag et al., 2012) was completed by the mothers at both the preschool and early school-age time points. To reduce informant bias, all informants in this study were mothers. To facilitate comparison across ages, we focused on the core 22 items, which span three primary types of features: irritable mood, behavioral expression of tantrums, and context in which tantrums occur. To increase power and interpretability, items within the same aspect of irritability that had high correlations and face validity suggesting similar target construct were combined by computing the mean, resulting in a total of 16 target irritability features (see Supplemental Methods). Mothers reported on their children’s disruptive behaviors using an objective frequency scale from 0=never to 5=many times each day. Scores equal to or greater than 2 (1-3 days of the week) were collapsed due to skewness, resulting in a scale of 0 = never, 1= rarely (less than once per week), 2 = 1-3 days of the week or more.

Statistical Analyses

A directed cross-lagged panel network (CLPN, Wysocki et al., 2022) was estimated to depict the connections between irritability symptoms in preschool and early school age. Instead of examining irritability as a homogenous construct, the network approach allows for the investigation of the interrelationship among these nuanced behaviors that may involve different internal processes. To construct this network, LASSO regularized regressions were performed in R (version 4.0.3, R Core Team, 2020) using the “glmnet” package, (version 4.1-8, Friedman et al., 2010), which estimated the autoregressive and cross-lagged (non-autoregressive) associations among irritability features in preschool-age and early school-age children. Specifically, autoregressive associations were estimated by regressing each variable at early school age (T2) on itself measured at preschool age (T1), controlling for all other variables at early school age (T2). Therefore, this relationship indicates the degree to which a symptom predicts itself over time. Similarly, the cross-lagged associations were estimated by regressing each variable at early school age (T2) on each other variable at preschool age (T1), controlling for all other variables at early school age (T2), measuring a longitudinal predictive relationship between two different symptoms. Ten-fold validation was applied to select the λ within one standard error of the minimum; this produced a parsimonious model that preserved the most salient connections while shrinking the others to zeros.

The regularized regression coefficients were then extracted to visualize the CLPN using the R package “qgraph” (version 1.9.2, Epskamp et al., 2012) with the regression coefficients as the edge weights. Network accuracy and stability were evaluated through nonparametric and case-dropping bootstrapping using the “bootnet” R package (Epskamp et al., 2017). The centrality indices provide a summary quantitative indicator of the strength, expected influence, and closeness of each node within the network. To evaluate the relative importance of the irritable behaviors, centrality indices, including in-expected influence (in-EI) and out-expected influence (out-EI), were computed as the sum of the incoming connections (i.e., predicted by other variables) and outgoing connections (i.e., predictive of other variables) respectively. Because we aimed to identify key behavioral and mood indicators that are predictive of later irritability features, out-EI was chosen to be the primary centrality measure, as it measures the extent to which a certain irritability behavior at preschool age is predictive of all other irritability behaviors at early school age.

Results

Overall Model Quality

The CLPN from preschool age to early school age produced a total of 256 possible connections among irritable behaviors, 16 of which were autoregressive connections, and 240 of which were non-autoregressive connections. After LASSO regularization, 15 non-zero autoregressive coefficients and 101 non-zero non-autoregressive coefficients remained (Figure 1). Bootstrapping results suggest acceptable to good stability for out-expected influence (out-EI, Correlation Stability [CS] = 0.36) and in-expected influence (in-EI, CS = 0.52) but low stability for bridge-expected influence (bridge-EI, CS = 0.13). Thus, bridge-EI results are not presented. Results regarding the in-expected influence are presented in the supplementary materials.

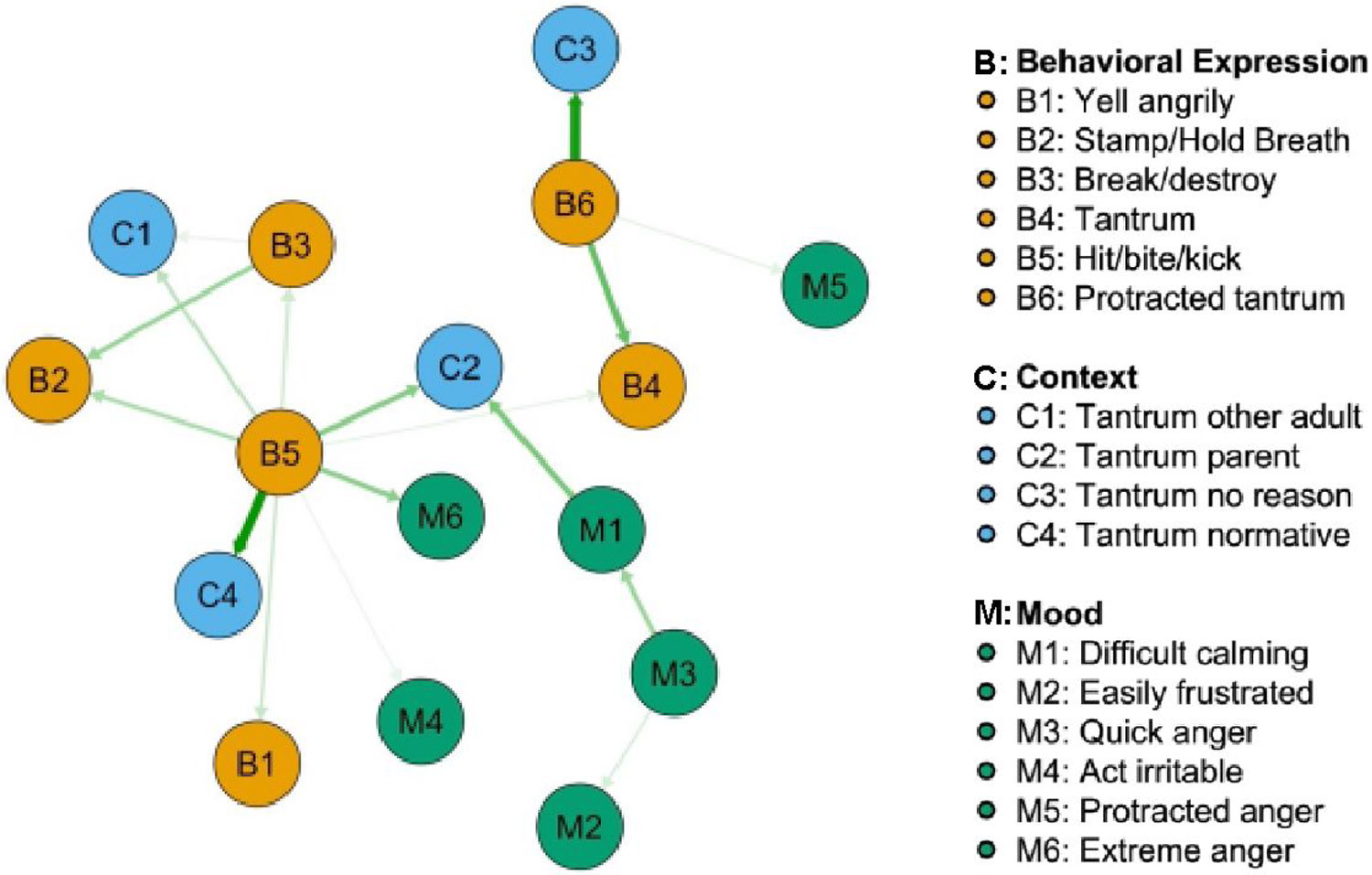

Figure 1. Cross-Lagged Panel Network – Predictive strength of each individual preschool age behavior to specific, other school age behaviors.

Note: Circles represent nodes (i.e., irritability features) and arrows represent temporal predictive relationship of one variable to other variables. Thickness of the arrow represents the strength of the predictive relationship (i.e., thicker arrow represents stronger relationship). For clarity, autoregressive and non-autoregressive edges less than 0.1 are not displayed. N = 382.

Key “hub” indicators: Strongest overall preschool-age predictors across all early school-age behaviors

Among the 16 candidate irritable behaviors at preschool age, “Hit, bite, or kick during a tantrum, fall-out, or melt-down” emerged as a key “hub” behavior (i.e., strongest out-EI, z = 2.74) that had the strongest predictive value across all early school age irritable behaviors. Other preschool-age irritable behaviors that strongly predicted across all irritable behaviors at early school age included: “Have a temper tantrum that lasted more than 5 minutes/even when tried calm him or her down/until exhausted” (out-EI z = 1.09) and “Have difficulty calming down when angry” (out-EI z = 0.85).

Specific pathways from one behavior at preschool age to another at school age

“Hit, bite, or kick during a tantrum” at preschool age also emerged as the strongest predictor of other specific irritable behaviors (i.e., non-autoregressive) at early school age, particularly “Losing temper in [various contexts]” (ß = .24). Protracted tantrums (“Have a temper tantrum that lasted more than 5 minutes/even when tried calm him or her down/until exhausted”) was the next strongest non-autoregressive preschool age predictor; this behavior at preschool age was associated with both unexpectable tantrums (“Lose temper or have a tantrum out of the blue or for no reason”, ß = .23) and maintained anger (“Stay angry for a long time”, ß = .18) at early school age.

Behaviors that maintained homotypic continuity (same manifestation over time)

Behaviors that were most likely to persist in the same form (autoregressive associations) from preschool to school age included “Act irritable” (ß = .28), “Yell angrily at someone” (ß = .28), and “Have a short fuse (become angry quickly)” (ß = .24).

Additional Analyses

Undirected cross-sectional networks, which depict the unique cross-sectional association between irritability features, were identified for the preschool-age and early school-age time points separately (Supplementary Materials, Figure S2). The network models achieved good stability for the centrality indices. Given the longitudinal focus of the present study, details of the cross-sectional network results are included in the supplementary materials.

To control for sociodemographic variables, a CLPN that included gender, race/ethnicity, age at the preschool-age time point, and poverty status as covariates was performed, with results consistent with the CLPN without covariates (i.e. identifying the same items with the highest out-EI and strongest connections, see supplementary material for detail). However, the model stability indices were not able to be accurately calculated for the model with covariates. Thus, the discussion focuses on the results from the CLPN without covariates. Future studies sufficiently powered to conduct separate analyses for each sociodemographic subgroup may wish to examine the network structure in different sociodemographic groups separately.

Discussion

Irritability is often discussed as a homogeneous concept, yet irritability is composed of multiple behaviors that can change over development. The present study is the first to examine how behavioral manifestations of irritability shift over time and how certain developmentally salient, early irritable behaviors can lead to other manifestations of irritability in later developmental stages. Indeed, while prior work has been fruitful in identifying age-banded irritable behaviors of interest (Alam et al., 2023; Hirsch et al., 2023; Krogh-Jespersen et al., 2022), no work had yet linked these developmentally sensitive characterizations of irritability to characterize how manifestations of irritable behavior may change over development. Tracing how neurodevelopmental vulnerability manifests differently across time, including key “hub” behaviors that may give rise to additional manifestations of irritability as time passes, will improve prevention and interventions by pinpointing behaviors to be triaged. These key “hub” behaviors have prognostic value, as they strongly predict a variety of future irritable behaviors and can be prioritized in pragmatic screening such as computer adaptive testing.

In the present study, we identified that hitting, biting, or kicking during a tantrum in preschool age was a key “hub” behavior more predictive of a large variety of future school-age irritable behaviors compared to other preschool-age irritability behaviors. Previous work has also identified hitting/biting/kicking as a primary behavior uniquely indicative of later impairment (Wiggins, Ureña Rosario, et al., 2023), in addition to other, similarly severe, violent/destructive tantrum behaviors, “break or destroy things during a temper tantrum” (Wiggins et al., 2018). Here, hit/bite/kick was only endorsed by 27% of the present study’s participants, making it the least frequently endorsed of the candidate irritable behaviors; yet, when families did endorse it at preschool age, it was associated with an increase in multiple other irritable behaviors at early school-age, highlighting its predictive potency. Our results, in combination with prior work (Wiggins et al., 2018; Wiggins, Ureña Rosario, et al., 2023), suggest that severe, pathognomonic irritable behaviors are critical for identifying at-risk children and moreover, in preschool age, may be a precursor to other irritable behaviors at early school age.

Protracted, dysregulated tantrums (“Have difficulty calming down when angry” and “Have a temper tantrum that lasted more than 5 minutes/even when tried calm him or her down/until exhausted”) emerged as other key “hub” behaviors strongly predictive of multiple other irritable behaviors at early school age, which speaks to the possibility of preschool age emotional dysregulation as foundational for risk. These findings are similar to previous work suggesting that the foundation of irritability is low frustration tolerance (Alam et al., 2023; Kirk et al., 2023; Wiggins et al., 2018, 2021; Wiggins, Ureña Rosario, et al., 2023) supporting the idea that a fundamental aspect of irritability is difficulty regulating negative emotions (e.g., frustration and anger). Indeed, in considering the key “hub” behaviors together (hit/bite/kick, a pathognomonic, severe indicator; and protracted dysregulated tantrums, a mood regulation component), our findings corroborate ongoing work on pragmatic screening deriving parsimonious models of key irritable behaviors (Alam et al., 2023; Hirsch et al., 2023; Wakschlag et al., 2024, Accepted; Wiggins et al., 2018; Wiggins, Ureña Rosario, et al., 2023). Indeed, across all these pragmatic screeners and in our present findings, the combination of a pathognomonic, severe behavior that most children do not do (e.g., violent/destructive tantrums) and a mood dysregulation component (e.g., protracted dysregulated tantrums) appears to indicate problematic irritability. Beyond the converging results with these studies that focused on identifying age-banded behaviors for irritability screeners, the current study further advanced the understanding of the developmentally sensitive presentation of irritability by examining how specific behaviors in one developmental stage predict behaviors in subsequent developmental stages, explicating the underlying heterotypic continuity processes.

We also identified preschool-age behaviors (that happened to overlap with the key “hub” behaviors) showing strong individual pathways to specific early school-age behaviors. In one of the cases, a pathognomonic, inherently severe behavior (hit/bite/kick) at preschool age led to what prior item response theory had deemed a mild behavior (have tantrums in various contexts, Wakschlag et al., 2012) when occurring at low frequencies; this “mild” behavior becomes problematic at higher frequencies (i.e., every day). Our results suggest that early, pathognomonic behavior can lead to later behaviors that may appear mild but are problematic at a higher frequency and/or at an older age. The other strong pathways were from protracted, dysregulated tantrums (tantrum more than 5 mins/even when tried to calm down/until exhausted) at preschool age leading to unexpectable tantrums (out of the blue) and to maintained anger (angry for a long time) in early school age; in these cases, as expected, pathognomonic behavior led to more pathognomonic behaviors. Of note, the homotypically continuous behaviors, manifesting the same from preschool to school age (i.e., act irritable, yell angrily, angry quickly), were, importantly, identified as truly “core” behaviors span age periods and are less developmentally specific. These behaviors likely persist from preschool to early school age, which is consistent with previous studies suggesting these items are relevant and should be assessed at these developmental stages.

While this study has several strengths, including a sociodemographically diverse sample, developmentally sensitive and nuanced measurement of irritability behaviors, and novel analytic techniques, the findings should be interpreted with consideration of the following limitations. The present study leveraged a community sample, and while it was enriched for irritability, the severity and/or frequency of irritable behaviors may be low relative to clinical samples. To address the skewness in the irritability items, the highest four categories of the objective frequency responses were combined, which could have masked nuances in the network model. While it is important to employ community samples, as community settings are where general screening for these behaviors take place, future studies may wish to leverage clinical samples with more severe irritability features. Of note, while the current study utilized the mother-report MAPS-TL as the irritability behavior measure, which provides objective frequencies of irritability behaviors, the questionnaire may not fully capture the child’s behavioral patterns in other salient social contexts (e.g., interactions with other caregivers or teacher). Future studies may wish to utilize a multi-method approach by including father-report, teacher-report, or observational data to measure irritability behaviors and capture the nuanced connections between context-dependent irritability behaviors. In addition, because the analyses required list-wise deletion for missing data, the sample size was limited. Therefore, the effect of sociodemographic variables on the network structure was not explored due to limited power. Future studies may wish to replicate these findings with large consortium datasets that have specialized irritability measures, which are not currently available, and to explore the impact of sociodemographic characteristics on network structure of irritability behaviors using sample stratification. Additionally, future research may wish to investigate aspects of irritability, such as its tonic and phasic expressions, more in depth by including measures specifically geared toward these constructs, such as The Irritability and Dysregulation of Emotion Scale (TIDES-13, Dissanayake et al., 2024), to examine the developmental transitions of these constructs.

This study characterized how behavioral manifestations of irritability shift over the transition from preschool age to early school age. The findings highlight the developmental nature of irritability behaviors, as not all behaviors are equally persistent or predictive of other behaviors, and suggest that developmental stages should be considered when measuring irritability-related symptoms in children. As our results indicated several behaviors in preschool age to be significantly predictive of future irritability behaviors, when measuring irritability symptoms at early developmental stages, emphasis should be placed on these identified behaviors as they can reflect a risk of broader and more pervasive psychopathology later on. The area of developmental science is emerging, and the current study contributes to the literature to support the growth of developmental theories.

In this study, we contribute to a burgeoning science base for the creation of early screening tools that prioritize developmentally salient irritability features associated with expanding, worsening symptoms. Our work highlights key irritability behavioral expressions that may be significant for the development and maintenance of other irritable behaviors, which may inform the development of intervention programs targeting these key “hub” behaviors to stop the emergence or exacerbation of later irritability manifestations. Such key irritability behaviors can be prioritized for assessment in brief, pragmatic screening measures. Preventive interventions can focus on these hub behaviors to prevent the downstream of a variety of symptoms. Future studies would benefit from further examining the possible mechanism of these behavioral shifts, more complex interactive effects, and additional symptom dimensions outcomes (e.g., anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity) to better understand the full extent of how irritable behaviors shift into psychopathology beyond temper and irritable mood-related constructs.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2. Out-expected Influence - Overall predictive strength of each preschool age behavior to all school age behaviors.

Note: The values displayed are z-standardized scores. N = 382.

Footnotes

Presentation information:

The preliminary findings of this study were presented as a poster at the Association for Psychological Science (APS) Annual Convention, San Francisco, CA., May 23-26, 2024.

References

- Alam T, Kirk N, Hirsch E, Briggs-Gowan M, Wakschlag LS, Roy AK, & Wiggins JL (2023). Characterizing the spectrum of irritability in preadolescence: Dimensional and pragmatic applications. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res, 32(S1), e1988. 10.1002/mpr.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake AS, Dupuis A, Arnold PD, Burton CL, Crosbie J, Schachar RJ, & Levy T (2024). Is irritability multidimensional: Psychometrics of The Irritability and Dysregulation of Emotion Scale (TIDES-13). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(8), 2767–2780. 10.1007/s00787-023-02350-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Smith VC, Bufferd SJ, Kessel E, Carlson GA, & Klein DN (2015). Preschool irritability predicts child psychopathology, functional impairment, and service use at age nine. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 56(9), 999–1007. 10.1111/jcpp.12403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Borsboom D, & Fried EI (2017). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, & Borsboom D (2012). qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J, Hastie T, & Tibshirani R (2010). Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. Journal of Statistical Software, 33(1), 1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Alam T, Kirk N, Bevans KB, Briggs-Gowan M, Wakschlag LS, Wiggins JL, & Roy AK (2023). Developmentally specified characterization of the irritability spectrum at early school age: Implications for pragmatic mental health screening. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 32(S1), e1985. 10.1002/mpr.1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung B, & Kim H (2023). The validity of transdiagnostic factors in predicting homotypic and heterotypic continuity of psychopathology symptoms over time. Front Psychiatry, 14, 1096572. 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1096572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk N, Hirsch E, Alam T, Wakschlag LS, Wiggins JL, & Roy AK (2023). A pragmatic, clinically optimized approach to characterizing adolescent irritability: Validation of parent- and adolescent reports on the Multidimensional Assessment Profile Scales-Temper Loss Scale. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res, 32(S1), e1986. 10.1002/mpr.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh-Jespersen S, Kaat AJ, Petitclerc A, Perlman SB, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Burns JL, Adam H, Nili A, Gray L, & Wakschlag LS (2022). Calibrating temper loss severity in the transition to toddlerhood: Implications for developmental science. Appl Dev Sci, 26(4), 785–798. 10.1080/10888691.2021.1995386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, & Stoddard J (2013). The developmental psychopathology of irritability. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt2), 1473–1487. 10.1017/s0954579413000722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhar A, Baghel P, & Patil M (2022). Early Childhood Development and Social Determinants. Cureus, 14(9), e29500. 10.7759/cureus.29500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquand AF, Kia SM, Zabihi M, Wolfers T, Buitelaar JK, & Beckmann CF (2019). Conceptualizing mental disorders as deviations from normative functioning. Mol Psychiatry, 24(10), 1415–1424. 10.1038/s41380-019-0441-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel PM, Pereira LO, Silveira PP, & Meaney MJ (2019). Early environmental influences on the development of children’s brain structure and function. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 61(10), 1127–1133. 10.1111/dmcn.14182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikita N, & Stringaris A (2013). Mood dysregulation. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S11–6. 10.1007/s00787-012-0355-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, & Wakschlag LS (2017). Research domain criteria (RDoC) grows up: Strengthening neurodevelopment investigation within the RDoC framework. Journal of Affective Disorders, 216, 30–35. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Zhang H, Santa Lucia R, King RA, & Lewis M (1996). Risk factors for presenting problems in child psychiatric emergencies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 35(9), 1162–1173. 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Flouri E, Lewis G, Solmi F, Stringaris A, & Lewis G (2024). Changes in Early Childhood Irritability and Its Association With Depressive Symptoms and Self-Harm During Adolescence in a Nationally Representative United Kingdom Birth Cohort. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 63(1), 39–51. 10.1016/j.jaac.2023.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, & Leibenluft E (2018). Practitioner Review: Definition, recognition, and treatment challenges of irritability in young people. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(7), 721–739. 10.1111/jcpp.12823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, Valdivieso I, Leibenluft E, & Stringaris A (2016). The Status of Irritability in Psychiatry: A Conceptual and Quantitative Review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(7), 556–570. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Carroll AJ, Friedland S, Walkup J, Wiggins JL, Mohanty N, Papacek E, Bridi S, Carroll R, Drelicharz D, Hasan Z, Kotagal T, Davis MM, & Smith JD (2024). Making it “EASI” for pediatricians to determine when toddler tantrums are “more than the terrible twos”: Proof-of-concept for primary care screening with the Multidimensional Assessment Profiles-Early Assessment Screener for Irritability (MAPS-EASI). Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 42(1), 34–49. 10.1037/fsh0000868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Choi SW, Carter AS, Hullsiek H, Burns J, McCarthy K, Leibenluft E, & Briggs-Gowan MJ (2012). Defining the developmental parameters of temper loss in early childhood: Implications for developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 53(11), 1099–1108. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02595.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Roberts MY, Flynn RM, Smith JD, Krogh-Jespersen S, Kaat AJ, Gray L, Walkup J, Marino BS, Norton ES, & Davis MM (2019). Future Directions for Early Childhood Prevention of Mental Disorders: A Road Map to Mental Health, Earlier. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 48(3), 539–554. 10.1080/15374416.2018.1561296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Zhang Y, Heffernan ME, MacNeill L, Peterson EO, Friedland S, Sass AJ, Smith JD, Davis MD, & Wiggins JL (Accepted). How EASI can it be?: Closing the research-to-practice gap via population-based validation of the MAPS-EASI 2.0 early childhood irritability screener for translation to clinical use. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JL, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Brotman MA, Leibenluft E, & Wakschlag LS (2021). Toward a Developmental Nosology for Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder in Early Childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(3), 388–397. 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JL, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Estabrook R, Brotman MA, Pine DS, Leibenluft E, & Wakschlag LS (2018). Identifying Clinically Significant Irritability in Early Childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(3), 191–199.e2. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JL, Roy AK, & Wakschlag LS (2023). MAPping affective dimensions of behavior: Methodologic and pragmatic advancement of the Multidimensional Assessment Profiles scales. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 32(S1), e1990. 10.1002/mpr.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JL, Ureña Rosario A, Zhang Y, MacNeill L, Yu Q, Norton E, Smith JD, & Wakschlag LS (2023). Advancing earlier transdiagnostic identification of mental health risk: A pragmatic approach at the transition to toddlerhood. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 32(S1), e1989. 10.1002/mpr.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki A, van Bork R, Cramer AOJ, & Rhemtulla M (2022). Cross-Lagged Network Models. 10.31234/osf.io/vjr8z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.