Abstract

We investigated the role in bacterial infection of a putative ABC transporter, designated ybiT, of Erwinia chrysanthemi AC4150. The deduced sequence of this gene showed amino acid sequence similarity with other putative ABC transporters of gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as well as structural similarity with proteins of Streptomyces spp. involved in resistance to macrolide antibiotics. The gene contiguous to ybiT, designated as pab (putative antibiotic biosynthesis) showed sequence similarity with Pseudomonas and Streptomyces genes involved in the biosynthesis of antibiotics. A ybiT mutant (BT117) was constructed by marker exchange. It retained full virulence in potato tubers and chicory leaves, but it showed reduced ability to compete in planta against the wild-type strain or against selected saprophytic bacteria. These results indicate that the ybiT gene plays a role in the in planta fitness of the bacteria.

Soft-rot diseases caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi and Erwinia carotovora occur worldwide and are of economic importance in a large number of crops (6, 10). The molecular basis of the pathogenicity of E. chrysanthemi has been intensively studied, and several genetic factors are known to play an important role in bacterial virulence: (i) genes encoding pectolytic enzymes, which degrade the plant cell walls and are responsible for the maceration symptoms (4, 18); (ii) genes encoding iron transport functions, which enable the bacteria to grow in iron-poor environments (12, 28); (iii) hrp genes (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity) which encode a type III secretion system involved in the delivery of proteins to the plant cell (2); and (iv) the sap operon (sensitive to antimicrobial peptides) which constitutes a detoxification mechanism that enables the bacterium to withstand the action of antimicrobial peptides from the host (20, 21).

In addition to the above-mentioned factors, E. chrysanthemi requires mechanisms to overcome competition from other types of bacteria that either enter the plant at the same time or are previously present. Bacterial populations associated with asymptomatic plants such as epiphytes or endophytes are common in natural conditions (3, 17, 24, 31). Certain bacterial species, such as Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas putida, are frequently present in the plant but are normally unable to reach a high population density, probably because plant defense mechanisms keep them under control (11). Therefore, competition for the same nutrient sources between pathogenic and saprophytic bacteria is probably an important factor in determining the bacterial population during infection. There has been relatively little work to test the importance of this concept in bacterial plant diseases; however, its importance is highlighted by the fact that E. carotovora produces the β-lactam antibiotic carbapenem, which appears to be involved in the competitive survival of the bacterium (35); furthermore, fluorescent pseudomonads produce phenazines and other natural antibiotics (33).

ABC transporters constitute a major class of proteins involved in the cellular translocation machinery and are present in the three major kingdoms of life. These proteins are defined by two main features: the nucleotide-binding domain, which energizes the transport process by coupling it with the hydrolysis of ATP or GTP, and the membrane-spanning domain, which is involved in the transfer process itself through a biological membrane (16). In prokaryotes, genes encoding ABC transporters constitute the largest known family of paralogs (36). Several subclasses have been defined, and there is generally a good correlation between sequence similarity and the type of molecule transported. In certain cases, bacterial ABC transporters are involved in antibiotic resistance by pumping the antibiotic molecule to the extracellular space (29). Hence, genes encoding ABC transporters in phytopathogenic bacteria are good candidates to play a role in virulence and/or survival in planta. In fact, we have previously reported the role of a peptide ABC transporter in the virulence of E. chrysanthemi (21).

In the present study we identified a gene from E. chrysanthemi encoding a putative ABC transporter, which shows sequence similarity to other putative transporters of gram-negative bacteria and macrolide resistance genes from Streptomyces spp. The corresponding mutant showed a wild-type level of virulence, but it was affected in its ability to compete in planta against the wild-type and against saprophytic bacteria present in potato tubers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbiological methods.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Strains of Escherichia coli were cultivated at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium. Strains of E. chrysanthemi were cultivated at 28°C in nutrient broth (NB; Difco, Detroit, Mich.) or King's B medium (19). Pseudomonas strains were cultivated at 28°C in King's B medium. Antibiotics were added to the media as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 15 μg/ml; and nalidixic acid, 20 μg/ml. Wild-type strains of Pseudomonas were isolated from potato tubers and identified by using the BIOLOG-Microlog System, 4.0 version (Biolog, Inc.). Macrolide inhibition assays were performed by the method described by López-Solanilla et al. (22).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 Δlac U169 (ø80 lacZM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 15 |

| XL1-Blue MRA | Δ(mcrA) 183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr) 173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac | |

| XL1-Blue MRA (P2) | XL1-Blue MRA (P2 lysogen) | Stratagene |

| E. chrysanthemi | ||

| AC4150 | Wild-type strain | 7 |

| BT117 | Δ(ybiT)::Tn7 Camr derivative of AC4150 | This work |

| P. fluorescens biotype G | Wild-type strain | This work |

| P. putida biotype B | Wild-type strain | This work |

| Plasmids and phages | ||

| pGEM T-Easy | Ampr | Promega |

| pBluescript II SK(−) | Ampr | Stratagene |

| pB108 | pBluescript II carrying AC4150 ybiT gene | This work |

| pB109 | pB108::Tn7 Camr | This work |

| λ-FIX II | Phage vector | Stratagene |

Camr, chloramphenicol resistant; Ampr, ampicillin resistant.

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

A genomic library of E. chrysanthemi was constructed in the λ-FIX II cloning vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Plasmid pBluescript SK(−) (Stratagene) was used for subcloning. A DNA fragment of the E. chrysanthemi ybiT gene was amplified by PCR and cloned in pGEM T-Easy (Promega, Madison, Wis.). This fragment was used as a probe to screen the DNA genomic library from wild-type E. chrysanthemi. The E. chrysanthemi ybiT mutants were obtained by Tn7 in vitro mutagenesis with the Genome Priming System kit (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The E. chrysanthemi ybiT gene was sequenced with supplied primers in the Genome Priming System kit. Marker exchange in E. chrysanthemi was performed as described previously (26). Standard molecular cloning techniques employed in this study were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (27). DNA sequencing of both strands was done by the chain termination method on double-stranded DNA templates with an Abiprism Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) in a 377 DNA Sequencer (Perkin-Elmer). Sequence alignments were performed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) with the BLAST network service (1). Secondary structure alignments were performed at Expasy tools (http://www.expasy.ch/tools) with the Jpred service (8). Multiple alignments represented in Fig. 1B were performed with CLUSTALW (34).

FIG. 1.

(A) Genetic and physical map of the insert of the pB108 clone from E. chrysanthemi. The insertion point of Tn7 in the mutant is indicated. Abbreviations: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; N, NotI; S, SalI; Sp, SphI. Camr, chloramphenicol resistance. (B) Alignment of the deduced YbiT amino acid sequence from E. chrysanthemi (YbiT E.chr.) with those from E. coli (YbiT E.col.) and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (YbiT P.aer.) and with macrolide resistance proteins from S. ambofaciens (SmrB) and S. lincolnensis (LmrC). Shaded letters indicate identical residues and conservative changes. The alignment was performed by using the CLUSTALW program. The ATP-binding domains are underlined. The EMBL accession numbers are as follows: AJ310611 (YbiT of E. chrysanthemi), P75790 (YbiT of E. coli) (5), D83399 (YbiT of P. aeruginosa) (30), X63451 (SmrB of S. ambofaciens) (14), and X79146 (LmrC of S. lincolnensis) (23).

Virulence assays.

Potato tubers (cv. Jaerla) and heads of witloof chicory were purchased from a local supermarket. The cells from an overnight NB liquid medium culture were washed with 10 mM MgCl2 by centrifugation and then resuspended in an appropriate volume of the same buffer to obtain the desired inoculum concentration. Potato tubers were inoculated with 50 μl of a suspension containing 5 × 105 bacteria by inserting a plastic micropipettor tip at a constant depth of 1.5 cm. The experiment was performed with 50 potato tubers; each one was inoculated separately at different points in the same tuber with wild-type and ybiT mutant strains in order to minimize the effect of the variability among individual potato tubers. Potatoes were kept at 28°C and 100% relative humidity for 48 h. The tubers were then sliced at the inoculation point, and the damage was estimated by measuring the macerated area. Differences between the wild-type and mutant strains were statistically assessed with a paired Student's t test. To monitor bacterial growth in potato tubers, 25 μl of a bacterial suspension containing 106 bacteria was inoculated on potato disks 1 cm in diameter and 1.5 mm thick. Disks were incubated at 28°C and high humidity, recovered at different times, and ground with a tissue homogenizer in 600 μl of 10 mM MgCl2. Bacterial CFU in the homogenate were determined by dilution plating. Six replicates were used to calculate means and standard errors. Statistical differences between paired means were assessed by using Student's t test (P < 0.05).

Virulence assays on witloof chicory leaves were performed as described by Bauer et al. (2) to compare wild-type and ybiT mutant strains. Each chicory leaf was inoculated at two locations with 10 μl of a suspension containing 2 × 105 bacterial cells, and 10 leaves were coinoculated with both wild-type and mutant strains. Chicory leaves were incubated for 48 h in a moist chamber at 28°C. The macerated area was measured, and differences between wild-type and mutant strains were statistically assessed with a paired Student's t test.

Competition assays.

We used the competitive index defined as the change in the population ratio of two strains after growth together under experimental conditions (13, 32). In vivo competition was determined by the estimation of the growth on potato tuber disks inoculated with 106 CFU of mixed inocula at a 1:1 ratio. The bacteria from the tissue were recovered 24 and/or 48 h later. Viable cell counts and the ratio of the two strains were determined by plating dilutions onto NB agar containing nalidixic acid or chloramphenicol for identification of the different strains. Parallel experiments to study competition in NB liquid medium were performed by growth at 28°C from a starting density of 106 CFU. Six independent replicates were used; the six corresponding indices were averaged, and the standard error of each mean was calculated.

Serial replacement experiments between E. chrysanthemi (wild type and BT117) and P. putida were done to compare the bacterial population reached when the strain was singly inoculated to the bacterial population reached when the strain was coinoculated with the other bacterial type. The experiments were done by inoculating potato disks as described above; for each comparison, the same level of inoculum of a given bacterial type was used in single inoculations and in coinoculations. In coinoculation experiments the proportions used were (in percentages) 25:75, 50:50, and 75:25 out of a total bacterial inoculum of 106 CFU. The bacterial populations of each type were estimated at 24 h. To compare singly inoculated versus coinoculated bacterial populations, an analysis of variance was performed for each of the following cases: (i) E. chrysanthemi AC4150 versus E. chrysanthemi AC4150 coinoculated with P. putida, (ii) E. chrysanthemi BT117 versus E. chrysanthemi BT117 coinoculated with P. putida, (iii) P. putida versus P. putida coinoculated with E. chrysanthemi AC4150, and (iv) P. putida versus P. putida coinoculated with E. chrysanthemi BT117. For each analysis of variance, two factors were considered: the “proportion of inocula” (25:75, 50:50, or 75:25) and the “type of inoculation” (single inoculation or coinoculation). Comparisons among means of bacterial population for each factor were made by using Fisher's least-significant-difference procedure.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences determined in this study were deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession numbers AJ310611 (ybiT gene) and AJ310612 (pab gene).

RESULTS

Cloning and analysis of the ybiT and pab genes of E. chrysanthemi.

Genes coding for transporters potentially involved in resistance to toxic substances were isolated in E. chrysanthemi. A specific fragment of 330 nucleotides (nt) was amplified by PCR with the oligonucleotides 5′-CTTGCAGAGGTCATTGGTAC-3′ and 5′-GTGGTGTGCTTCGTGACAA-3′ (based in conserved sequences found in transporters from other bacterial species). This fragment was cloned in a pGEM T-Easy vector and used to probe a λ-FIX II genomic library of E. chrysanthemi AC4150. A positive clone was isolated and subjected to restriction mapping. An internal EcoRI-NotI fragment of 5.1 kb, which was the only one that hybridized with the probe, was subcloned in the vector pBluescript SK(−) and designated pB108 (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). This clone was subjected to Tn7 in vitro mutagenesis, and several clones bearing Tn7 transposons within the insert were selected. Several of these constructions were used for sequencing an internal region of 1,865 nt of pB108. An open reading frame was found that was homologous to the ybiT gene of E. coli (87% amino acid identity), and the E. chrysanthemi gene was consequently named ybiT, since several homologous genes found in other bacteria have received the same designation. The ybiT sequence of E. chrysanthemi was used for the search with the BLAST service (1) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and the closest hits were the YbiT proteins of E. coli (87% identity), Vibrio cholerae N16961 (74%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 (72%), and Neisseria meningitidis MD58 (63%). The E. chrysanthemi ybiT sequence was further analyzed by using an interactive protein secondary structure prediction program (8) (Jpred, http://www.expasy.ch/tools), and the closest hits were the srmB gene of Streptomyces ambofaciens and the carA gene of Streptomyces thermotolerans, which are involved in bacterial resistance to the macrolide antibiotics spiramycin and carbomycin, respectively. Considering both types of analysis, a multiple alignment of related sequences was performed with CLUSTALW (34) (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/ClustalW.html) (Fig. 1B). The above-mentioned YbiT and macrolide resistance proteins possess four nucleotide-binding domains—two Walker A (GPSGSGKS) and two Walker B (LLLDEPXXXLD)—but they lack membrane-spanning domains (see Fig. 1B).

In the region flanking the ybiT gene, an open reading frame was identified which showed amino acid sequence similarity with genes involved in antibiotic biosynthesis, such as PhzF from P. aeruginosa (32%) and LmbX from Streptomyces lincolnensis (29%), which are involved in the biosynthesis of phenazines and the macrolide lincomycin, respectively (23, 30).

Characterization of the ybiT mutant of E. chrysanthemi.

To obtain an insertional mutant of the ybiT gene, an appropriate Tn7 insertion in pB108 was selected (Fig. 1A). This clone was named pB109 (Table 1) and was marker exchanged into the E. chrysanthemi AC4150 chromosome. Of several Amps Camr recombinants (data not shown), one mutant strain, BT117, was selected for further analysis. Marker exchange was verified by DNA gel blot hybridization (data not shown). This mutant was analyzed by using the BIOLOG-Microlog System, and no differences in the utilization of carbon sources were found. The mutant BT117 and the wild type showed essentially the same growth rate in liquid medium (data not shown). To investigate the possible effect of the ybiT mutation on outer membrane permeability, the susceptibility of BT117 to lysozyme and rifampin was assayed, and no significant differences with respect to the wild type were found (data not shown). Furthermore, no difference in the mutant with respect to the wild type was found for the following characteristics: colony size, morphology, cell size and appearance, and production of pectic enzymes (data not shown). The susceptibility of mutant BT117 to several macrolide antibiotics was investigated by performing inhibition assays, with maximum concentrations of up to 165 μg/ml for carbomycin and 200 μg/ml for erythromycin and tylosin. No differences between the two strains were observed with these antibiotics (data not shown).

Virulence of the ybiT mutant.

To investigate the possible effect on virulence of the ybiT mutation, potato tubers were inoculated with E. chrysanthemi AC4150 or mutant BT117. Necrotic areas of the developed lesions were measured in all of the tubers after 48 h, and no statistically significant differences were found among the lesions produced by the two strains (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effects of Δ(ybiT)::Tn7 mutation on the virulence of E. chrysanthemi on potato tubers and witloof chicory leaves

| Expt | Mean size (cm2) of lesion ± SEa with strain:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| AC4150 | BT117 | |

| Potato tubers | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.1b |

| Witloof chicory leaves | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1b |

Values are the product of the length and width of the necrotic area.

Differences between parental and mutant strains are not significant according to the Student's t test (P < 0.05).

The virulence of E. chrysanthemi AC4150 and mutant BT117 was also assayed by inoculation of witloof chicory leaves. Necrotic areas of the developed lesions were measured 48 h after inoculation, and no statistically significant differences were found between the mutant and wild-type strains (Table 2). Growth rates in planta of the wild type and the mutant were also determined by inoculation in potato tuber disks, and the results indicated no differences between the two strains (data not shown).

In planta fitness of the ybiT mutant.

Since the ybiT gene of E. chrysanthemi showed structural homology to genes coding for resistance to macrolide antibiotics in Streptomyces spp. and these bacteria also produce the corresponding antibiotics, we hypothesized that E. chrysanthemi may be producing a macrolide-like molecule and that the resistance to this substance could be mediated by the YbiT protein. To further investigate this phenomenon, we performed competition analysis to ascertain whether or not the ybiT mutant was impaired in its ability to compete with the wild-type strain in the plant tissue. Potato tuber disks were inoculated with 106 CFU of mixed inocula (1:1) of the wild-type and mutant strains. After 24 and 48 h, bacteria were recovered from the infected tissue, and viable cells from each population were determined by dilution plating on selective media. The competitive index is defined as the output ratio of mutant to wild-type bacteria divided by the input ratio of mutant to wild-type bacteria. The index obtained for the ybiT mutant was of 0.5 ± 0.1 at 24 h and 0.3 ± 0.2 at 48 h, and the statistical analysis indicated that both indices differ significantly from 1. A parallel experiment showed that the competitive index was not significantly different from 1 in rich liquid (KB) medium (data not shown).

During these experiments we observed the presence of contaminating bacteria, which were previously present as endophytes in asymptomatic tubers, and these contaminations appeared to be more frequent in recovering the ybiT mutant from plant tissues than when the wild type was recovered. Several of these contaminating bacteria were isolated and then identified by the automated BIOLOG system as P. fluorescens biotype G and P. putida biotype B. One strain of each case was subjected to competition experiments at 24 h against E. chrysanthemi wild type and the ybiT mutant, and the results are shown in Table 3. Clearly, the two Pseudomonas strains are able to displace both E. chrysanthemi wild-type and mutant strains, but the competitive indices were more than 1 order of magnitude smaller in the case of the mutant than in the case of the wild type, indicating that the mutant strain was less competitive than the wild type. In parallel experiments performed in KB medium, the competitive indices of the mutant strain with respect to P. putida and P. fluorescens were similar to those obtained with the wild type against the same Pseudomonas strains (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Indices of competition in planta between E. chrysanthemi (AC4150 [wild type] and mutant BT117) and P. fluorescens biotype G and P. putida biotype B strains

| Strains | CIa (mean ± SE) |

|---|---|

| E. chrysanthemi AC4150 vs P. fluorescens | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Mutant BT117 vs P. fluorescens | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| E. chrysanthemi AC4150 vs P. putida | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| Mutant BT117 vs P. putida | 0.003 ± 0.00 |

Competitive index (CI) is defined as the output ratio of E. chrysanthemi AC4150 or mutant BT117 bacteria to P. fluorescens or P. putida strains divided by the input ratio of E. chrysanthemi AC4150 or mutant BT117 to P. fluorescens or P. putida strains. The data are the results of six independent experiments.

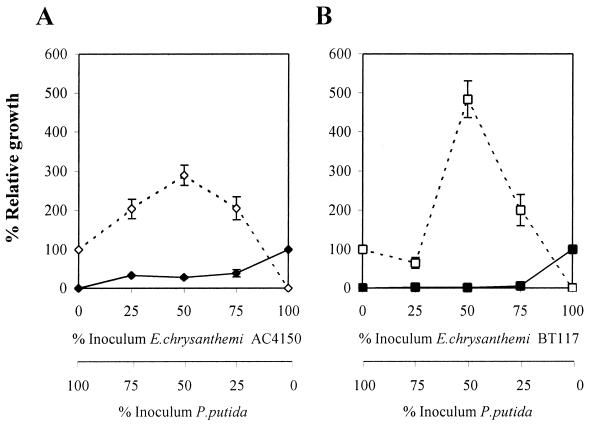

To further investigate this phenomenon, serial replacement competition experiments were performed between P. putida and E. chrysanthemi wild-type and mutant strains. Coinoculations of the two types of bacteria (E. chrysanthemi versus P. putida) were done by using a total inoculum of 106 CFU, with proportions (in percentages) of 25:75, 50:50, and 75:25 of each bacterial type. Single-inoculation experiments were carried out with the same level of inoculum (for a given bacterial type) as in the coinoculation experiments. In addition, the single-inoculated proportions of 0:100 and 100:0 (percentages) were included in the study. All of the inoculations were done in triplicate potato disks. Statistical analysis was performed as explained in Materials and Methods. Table 4 shows the statistical results of the means of bacterial populations for the factor “type of inoculation.” The effect of coinoculating P. putida and E. chrysanthemi (in both the wild type and the mutant) is to decrease significantly the bacterial growth of E. chrysanthemi, whereas the P. putida population significantly increased (Table 4). The results indicate that P. putida benefited from the coinoculation, whereas E. chrysanthemi was at a disadvantage. Figure 2 shows the relative effect of coinoculation in the bacterial growth of each strain. The results are the means of bacterial populations attained in the coinoculation experiments, expressed as a percentage of the means obtained for the corresponding single inoculation. These results indicate that the mutant strain was diminished in its ability to compete in planta compared to the wild type.

TABLE 4.

Pairwise statistical comparison between singly inoculated and coinoculated bacterial populations of E. chrysanthemi (AC4150 [wild type] and mutant BT117) and P. putida biotype B strains in potato disks

| Strain | Meana (CFU, 109) | SEb (CFU, 109) | 95% CI of the meanc (CFU, 109)

|

Difference of means (CFU, 109)d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| E. chrysanthemi AC4150 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 2.9∗ |

| E. chrysanthemi AC4150 (+P. putida) | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.9 | ||

| E. chrysanthemi BT117 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 4.5∗ |

| E. chrysanthemi BT117 (+P. putida) | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 | ||

| P. putida | 6.1 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 8.3 | −7.8∗ |

| P. putida (+E. chrysanthemi AC4150) | 13.9 | 11.6 | 16.1 | ||

| P. putida | 6.1 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 8.9 | −7.4∗ |

| P. putida (+E. chrysanthemi BT117) | 13.4 | 10.7 | 16.2 | ||

Means are values of nine replicates (three for each proportion of coinoculation).

The standard error is the pooled standard deviation (as estimated by analysis of variance) divided by the square root of the number of replicates.

Lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the mean value of the population.

Differences of each pair of means. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences as determined by the least-significant-difference procedure.

FIG. 2.

Relative growth of P. putida and E. chrysanthemi AC4150 and mutant BT117 in coinoculation with respect to single-inoculation experiments, at several inoculum proportions. (A) E. chrysanthemi AC4150 (⧫) versus P. putida (◊); (B) E. chrysanthemi BT117 (▪) versus P. putida (□). The units of the vertical axes are percent relative growth, i.e., the ratio of the number of bacterial cells recovered in a coinoculation experiment divided by the number of the bacterial cells recovered in the corresponding single-inoculation experiment.

DISCUSSION

To be successful as a plant pathogen, a bacterium must be able to (i) obtain nutrients in the plant apoplast, (ii) withstand or elude the defense reaction from the plant, and (iii) compete efficiently with other microorganisms present in the apoplast. This latter aspect has received relatively little attention in bacterial plant pathogens, although it is essential for the study of bacterial interactions in the rhizosphere. The survival of microorganisms in natural environments is favored by the capacity to produce compounds that are toxic to competing organisms and by the ability to resist the effects of such toxic compounds (33). We identified here a putative ABC transporter from E. chrysanthemi which has sequence similarity to the antibiotic resistance gene products of Streptomyces spp. and is involved in the bacterial ability to compete in planta.

The ybiT gene product of E. chrysanthemi showed a high sequence similarity with other gene products found in gram-negative bacteria, most of them designated YbiT (Fig. 1B). All of these proteins have two conserved ATP-binding domains and lack transmembrane domains (Fig. 1B). It is a common feature in prokaryotic transporters that both types of domains are located in different polypeptides; thus, they must act as multicomponent transporters (25). The function of ybiT genes is currently unknown, although a role in transport of molecules has been proposed, based on sequence similarity with other transporters (30). For example, the yheS and yjjK genes of E. coli, which have sequence similarity to the ybiT gene of E. chrysanthemi, are thought to be involved in antibiotic resistance (9). To our knowledge, this is the first phenotype reported for a mutant corresponding to a member of this gene family.

The ybiT gene of E. chrysanthemi is also similar to genes from Streptomyces spp. coding for macrolide resistance. Interestingly, when a search algorithm based on secondary structure prediction was used, the Streptomyces smrB gene was the closest match (see results), despite the fact that this gene has a 30% similarity in primary structure (Fig. 1B). Genes smrB, carA, tlrC, and lmrC of S. ambofaciens, S. thermotolerans, Streptomyces fradiae, and S. lincolnensis are involved in resistance to the macrolide antibiotics spiramycin, carbomycin, tylosin, and lincomycin, respectively, and it has been proposed that antibiotic export is the mechanism by which these genes confer resistance to their respective antibiotics (29). Also, the gene contiguous to ybiT in E. chrysanthemi, designated pab (putative antibiotic biosynthesis), showed sequence homology with other genes involved in the biosynthesis of antibiotics, such as lmbX of S. lincolnensis, which codes for lincomycin (23), and phzF from P. aeruginosa PAO1, which is involved in the synthesis of phenazines (30). This led us to the hypothesis that the genes found in E. chrysanthemi may also be involved in the production of and resistance to antibiotics. Although this hypothesis is congruent with the behavior of the mutant strain in coinoculation experiments (see below), more investigation will be necessary to confirm or reject it.

We have used the estimation of the competitive indices from coinoculation experiments to analyze the effect of the ybiT mutation on bacterial competence during infection. The competitive index has been widely used in animal systems to analyze mutants with diminished ability to colonize host tissues (13). When the competitive index is significantly less than 1 in vivo, but not in vitro, it can be considered that the mutation has an effect on the ability to colonize the tissue and that it cannot be complemented by coinfection. The competitive index of the ybiT mutant was 0.5 in planta, whereas in rich medium the mutant was not significantly impaired. It must be pointed out that the altered ability of the ybiT mutant to compete in planta with other bacteria is neither due to diminished virulence, as the pathogenicity test indicated (see Table 2), nor due to diminished capacity to grow in planta in the absence of competitors (data not shown).

We have used the competitive index and serial replacement analysis to assess the competitive ability of the E. chrysanthemi ybiT mutant against saprophytic bacteria (Tables 3 and 4 and Fig. 2). Two strains of P. fluorescens and P. putida were chosen for these experiments since these bacteria had been frequently isolated from potato tubers and, thus, they are potential competitors of E. chrysanthemi in field or storage conditions. Three main conclusions can be drawn from these studies. First, the Pseudomonas strains were always able to outgrow E. chrysanthemi in potato tubers. Second, the competitiveness of the ybiT mutant was lower than that of the wild type; the competitive index versus P. putida was 30 times lower, and there were also clear differences in the serial replacement analysis. Third, not only did P. putida outgrow E. chrysanthemi but the actual bacterial populations attained were significantly higher than those in the absence of Erwinia (see Table 4 and Fig. 2). This is particularly striking in the coinoculation of P. putida with the ybiT mutant at 50%, which produced an almost fivefold increase in the bacterial population of P. putida (Fig. 2). For a possible explanation of this phenomenon, we can postulate that Erwinia sp. acts first, killing plant cells and breaching the plant defenses, and that in a second stage saprophytes are more effective in the utilization of the released nutrients.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the impaired ability to compete in planta of the ybiT mutant. This finding is congruent with a possible involvement of this gene in resistance against natural antibiotics, but other explanations cannot be ruled out. The study of this type of resistance will merit future investigations, and it could be utilized for improving the biocontrol capacity of other bacteria. It will also be interesting to determine whether the ybiT genes of other bacteria, such as E. coli, are also involved in competition in their natural niches. This phenomenon could play a role in the competitiveness of E. chrysanthemi in natural conditions and could be involved in the survival and persistence of the bacteria in soils or in epiphytic conditions.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Rosa Raposo (INIA [Spain]) for her advice in statistical analysis. We also thank Carlos Pérez-Villota (Lilly Company) and Isabel Apaolaza (Pfizer, S.A.) for the generous gifts of the macrolide antibiotics tylosin and carbomycin, respectively. We thank Angeles Rubio, Joaquin García-Guijarro, and Dolores Lamoneda for technical assistance. We thank Francisco García-Olmedo, Isabel Aguilar, and César Poza-Carrión for the critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was financed by the Ministry of Science and Technology (PGC) project P98-0734.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer, D. W., A. J. Bogdanove, S. V. Beer, and A. Collmer. 1994. Erwinia chrysanthemi hrp genes and their involvement in soft rot pathogenesis and elicitation of the hypersensitive response. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 7:573-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beattie, G. A., and S. E. Lindow. 1995. The secret life of foliar bacterial pathogens on leaves. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 33:145-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaulieu, C., M. Boccara, and F. Van Gijsegem. 1993. Pathogenic behavior of pectinase-defective Erwinia chrysanthemi mutants on different plants. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 6:197-202. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boccara, M., R. Vedel, D. Lalo, M.-H. Lebrun, and J. F. Lafay. 1991. Genetic diversity and host range in strains of Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 4:293-299. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee, A. K., K. K. Thurn, and D. A. Feese. 1983. Tn5-induced mutations in the enterobacterial phytopathogen Erwinia chrysanthemi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:644-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuff, J. A., M. E. Clamp, A. S. Siddiqui, M. Finlay, and G. J. Barton. 1998. JPred: a consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 14:892-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dassa, E., M. Hofnung, I. T. Paulsen, and M. H. Saier. 1999. The Escherichia coli ABC transporters: an update. Mol. Microbiol. 32:887-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickey, R. S. 1979. Erwinia chrysanthemi: a comparative study of phenotypic properties of strains from several hosts and other Erwinia species. Phytopathology 69:324-329. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elvira-Recuenco, M., and J. W. van Vuurde. 2000. Natural incidence of endophytic bacteria in pea cultivars under field conditions. Can. J. Microbiol. 46:1036-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franza, T., C. Sauvage, and D. Expert. 1999. Iron regulation and pathogenicity in Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937: role of the Fur repressor protein. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freter, R., P. C. O'Brien, and M. S. Macsai. 1981. Role of chemotaxis in the association of motile bacteria with intestinal mucosa: in vivo studies. Infect. Immun. 34:234-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geistlich, M., R. Losick, J. R. Turner, and R. N. Rao. 1992. Characterization of a novel regulatory gene governing the expression of a polyketide synthase gene in Streptomyces ambofaciens. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2019-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins, C. F. 1992. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 8:67-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinton, D. M., and C. W. Bacon. 1995. Enterobacter cloacae is an endophytic symbiont of corn. Mycopathologia 129:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keen, N. T., D. Dahlbeck, B. Staskawicz, and W. Belser. 1984. Molecular cloning of pectate lyase genes from Erwinia chrysanthemi and their expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 159:825-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King, E. O., M. K. Ward, and O. E. Raney. 1954. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 44:301-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.López-Solanilla, E., F. García-Olmedo, and P. Rodríguez-Palenzuela. 1998. Inactivation of the sapA to sapF locus of Erwinia chrysanthemi reveals common features in plant and animal bacterial pathogenesis. Plant Cell 10:917-924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López-Solanilla, E., A. Llama-Palacios, A. Collmer, F. García-Olmedo, and P. Rodríguez-Palenzuela. 2001.. Relative effects on virulence of mutations in the sap, pel, and hrp loci of Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:386-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.López-Solanilla, E., M. Pernas, R. Sánchez-Monge, G. Salcedo, and P. Rodríguez-Palenzuela. 1999. Antifungal activity of a plant cystatin. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:624-627. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peschke, U., H. Schmidt, H. Z. Zhang, and W. Piepersberg. 1995. Molecular chacterization of the lincomycin-production gene cluster of Streptomyces lincolnensis 78-11. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1137-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pleban, S., L. Chernin, and I. Chet. 1997. Chitinolytic activity of an endophytic strain of Bacillus cereus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 25:284-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quentin, Y., and G. Fichant. 2000. ABCdb: an ABC transporter database. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:501-504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roeder, D. L., and A. Collmer. 1985. Marker-exchange mutagenesis of a pectate lyase isozyme gene in Erwinia chrysanthemi. J. Bacteriol. 164:51-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. A. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Sauvage, C., and D. Expert. 1994. Differential regulation by iron of Erwinia chrysanthemi pectate lyases: pathogenicity of iron transport regulatory (cbr) mutants. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 7:71-77. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoner, B., M. Geistlich, P. Rosteck, Jr., R. N. Rao, E. Seno, P. Reynolds, K. Cox, S. Burgett, and C. Hershberger. 1992. Sequence similarity between macrolide-resistance determinants and ATP-binding transport proteins. Gene 115:93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, and I. T. Paulsen. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tapia-Hernandez, A., M. R. Bustillos-Cristales, T. Jimenez-Salgado, J. Caballero-Mellado, and L. E. Fuentes-Ramirez. 2000. Natural endophytic occurrence of Acetobacter diazotrophicus in pineapple plants. Microb. Ecol. 39:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor, R. K., V. L. Miller, D. B. Furlong, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2833-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomashow, L. S., and D. A. Weller. 1995. Current concepts in the use of introduced bacteria for biological control: mechanisms and antifungal metabolites, p. 187-235. In G. Stacey and N. Keen (ed.), Plant-microbe interactions. Chapman and Hall, New York, N.Y.

- 34.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomson, N. R., M. A. Crow, S. J. McGowan, A. Cox, and G. P. C. Salmond. 2000. Biosynthesis of carbapenem antibiotic and prodigiosin pigment in Serratia is under quorum sensing control. Mol. Microbiol. 36:539-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomii, K., and M. Kanehisa. 1998. A comparative analysis of ABC transporters in complete microbial genomes. Genome Res. 8:1048-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]