Abstract

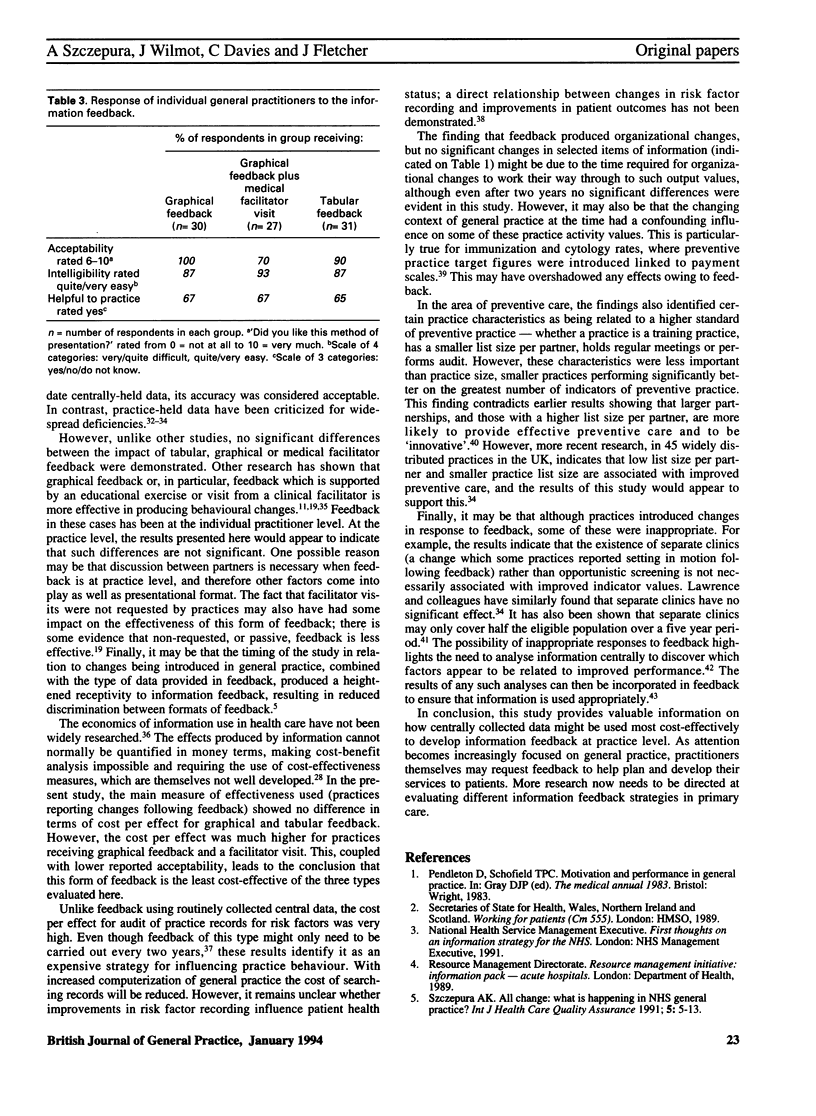

AIM. The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness and relative cost of three forms of information feedback to general practices--graphical, graphical plus a visit by a medical facilitator and tabular. METHOD. Routinely collected, centrally-held data were used where possible, analysed at practice level. Some non-routine practice data in the form of risk factor recording in medical notes, for example weight, smoking status, alcohol consumption and blood pressure, were also provided to those who requested it. The 52 participating practices were stratified and randomly allocated to one of the three feedback groups. The cost of providing each type of feedback was determined. The immediate response of practitioners to the form of feedback (acceptability), ease of understanding (intelligibility), and usefulness of regular feedback was recorded. Changes introduced as a result of feedback were assessed by questionnaire shortly after feedback, and 12 months later. Changes at the practice level in selected indicators were also assessed 12 and 24 months after initial feedback. RESULTS. The resulting cost per effect was calculated to be 46.10 pounds for both graphical and tabular feedback, 132.50 pounds for graphical feedback plus facilitator visit and 773.00 pounds for the manual audit of risk factors recorded in the practice notes. The three forms of feedback did not differ in intelligibility or usefulness, but feedback plus a medical facilitator visit was significantly less acceptable. There was a high level of self-reported organizational change following feedback, with 69% of practices reporting changes as a direct result; this was not significantly different for the three types of feedback. There were no significant changes in the selected indicators at 12 or 24 months following feedback. The practice characteristic most closely related to better indicators of preventive practice was practice size, smaller practices performing significantly better. Separate clinics were not associated with better preventive practice. CONCLUSION. It is concluded that feedback strategies using graphical and tabular comparative data are equally cost-effective in general practice with about two thirds of practices reporting organizational change as a consequence; feedback involving unsolicited medical facilitator visits is less cost-effective. The cost-effectiveness of manual risk factor audit is also called into question.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson C. M., Chambers S., Clamp M., Dunn I. A., McGhee M. F., Sumner K. R., Wood A. M. Can audit improve patient care? Effects of studying use of digoxin in general practice. BMJ. 1988 Jul 9;297(6641):113–114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6641.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braham R. L., Ruchlin H. S. Physician practice profiles: a case study of the use of audit and feedback in an ambulatory care group practice. Health Care Manage Rev. 1987 Summer;12(3):11–16. doi: 10.1097/00004010-198701230-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C., van Zwanenberg T. D. Primary and community health services in Newcastle upon Tyne--a joint statement of intent. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989 Apr;39(321):164–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm J. W. The 1990 contract: its history and its content. BMJ. 1990 Mar 31;300(6728):853–856. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6728.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter A., Brown S., Daniels A. Computer held chronic disease registers in general practice: a validation study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1989 Mar;43(1):25–28. doi: 10.1136/jech.43.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. E., Haynes R. B., Birkett N. J., Gilbert J. R., Taylor D. W., Sackett D. L., Johnston M. E., Hewson S. A. Does a mailed continuing education program improve physician performance? Results of a randomized trial in antihypertensive care. JAMA. 1986 Jan 24;255(4):501–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett G. D., deBlois C. S., Chang P. F., Holets T. Effect of cost education, cost audits, and faculty chart review on the use of laboratory services. Arch Intern Med. 1983 May;143(5):942–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser R. C., Gosling J. T. Information systems for general practitioners for quality assessment: I. Responses of the doctors. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985 Nov 23;291(6507):1473–1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6507.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant G. B., Gregory D. A., van Zwanenberg T. D. Development of a limited formulary for general practice. Lancet. 1985 May 4;1(8436):1030–1032. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91625-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horder J., Bosanquet N., Stocking B. Ways of influencing the behaviour of general practitioners. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1986 Nov;36(292):517–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson A., Mitford P., Aylett M. Creating a general practice data set: new role for Northumberland Local Medical Committee. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Oct 24;295(6605):1029–1032. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6605.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M., Coulter A., Jones L. A total audit of preventive procedures in 45 practices caring for 430,000 patients. BMJ. 1990 Jun 9;300(6738):1501–1503. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6738.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugford M., Banfield P., O'Hanlon M. Effects of feedback of information on clinical practice: a review. BMJ. 1991 Aug 17;303(6799):398–402. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6799.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop P., Winkens R. A. A diagnostic centre for general practitioners: results of individual feedback on diagnostic actions. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989 Dec;39(329):507–508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland M. O., Middleton J., Goss B., Moore A. T. Should performance indicators in general practice relate to whole practices or to individual doctors? J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989 Nov;39(328):461–462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner W., Ray W. A., Federspiel C. F., Miller W. O. Improving antibiotic prescribing in office practice. A controlled trial of three educational methods. JAMA. 1983 Oct 7;250(13):1728–1732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlager D. D. A comprehensive patient care system for the family practice. J Med Syst. 1983 Apr;7(2):137–145. doi: 10.1007/BF00995120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley J. C., Sackett D. L., Neufeld V., Gerrard B., Rudnick K. V., Fraser W. A randomized trial of continuing medical education. N Engl J Med. 1982 Mar 4;306(9):511–515. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203043060904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepura A., Mugford M., Stilwell J. A. Information for managers in hospitals: representing maternity unit statistics graphically. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Apr 4;294(6576):875–880. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6576.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepura A. Routine low-cost pathology tests: measuring the value in use of bacteriology tests in hospital and primary care. Health Serv Manage Res. 1992 Nov;5(3):225–237. doi: 10.1177/095148489200500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. W., Ritchie L. D., Taylor R. J., Ryan M. P., Paterson N. I., Duncan R., Brotherston K. G. General practice computing in Scotland. BMJ. 1990 Jan 20;300(6718):170–172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6718.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller D., Agass M., Mant D., Coulter A., Fuller A., Jones L. Health checks in general practice: another example of inverse care? BMJ. 1990 Apr 28;300(6732):1115–1118. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6732.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten M. A., Bazel D., Shannon H. S. Computerized protocol for preventive medicine: a controlled self-audit in family practice. Fam Pract. 1989 Jun;6(2):120–124. doi: 10.1093/fampra/6.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]