Abstract

In Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26, LinD and LinE activities, which are responsible for the degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane, are inducibly expressed in the presence of their substrates, 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone (2,5-DCHQ) and chlorohydroquinone (CHQ). The nucleotide sequence of the 1-kb upstream region of the linE gene was determined, and an open reading frame (ORF) was found in divergent orientation from linE. Because the putative protein product of the ORF showed similarity to the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family, we named it linR. The fragment containing the putative LTTR recognition sequence (a palindromic TN11A sequence), which exists immediately upstream of linE, was ligated with the reporter gene lacZ and was inserted into the plasmid expressing LinR under the control of the lac promoter. When the resultant plasmid was introduced into Escherichia coli, the LacZ activity rose in the presence of 2,5-DCHQ and CHQ. RNA slot blot analysis for the total RNAs of UT26 and UT102, which has an insertional mutation in linR, revealed that the expression of the linD and linE genes was induced in the presence of 2,5-DCHQ, CHQ, and hydroquinone in UT26 but not in UT102. These results indicated that the linR gene is directly involved in the inducible expression of the linD and linE genes.

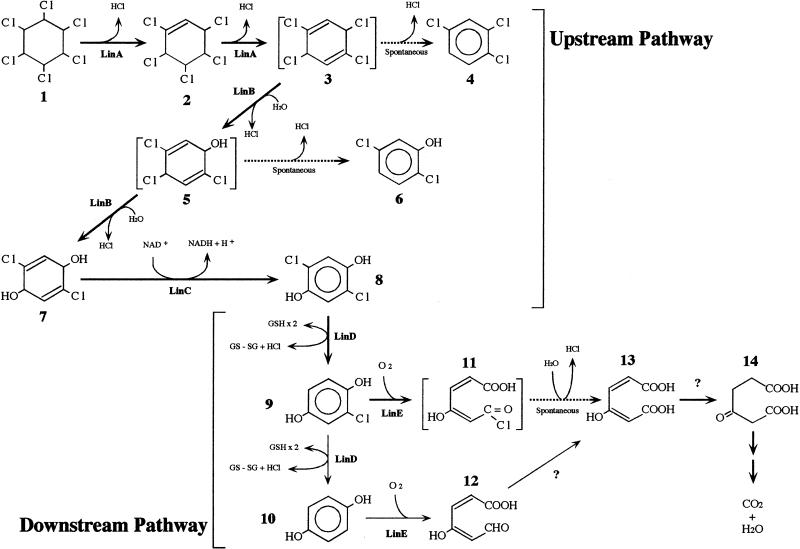

γ-Hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH; also called γ-BHC or lindane) is a haloorganic insecticide which has been used worldwide. Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26 can utilize γ-HCH as a sole source of carbon and energy (4). The degradation pathway of γ-HCH in UT26 consists of upstream and downstream pathways, which are shown in Fig. 1 (11). In the upstream pathway, γ-HCH is transformed to 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone (2,5-DCHQ), which is further degraded in the downstream pathway. In the previous studies, we isolated five genes (linA, linB, linC, linD, and linE) involved in these pathways and characterized their protein products (3, 7, 8, 12, 13). The linA, linB, and linC genes, for the upstream pathway, exist separately on the UT26 genome and are constitutively expressed (4, 12, 13). On the other hand, the linD and linE genes, for the downstream pathway, are located near each other and are inducibly expressed in the presence of their substrates (7, 8). They may constitute an operon (7). LinE is a novel meta-cleavage dioxygenase which cleaves aromatic rings with two hydroxy groups at para positions. We also demonstrated that PcpA from a pentachlorophenol-degrading bacterium, Sphingomonas chlorophenolica ATCC 39723, has activity similar to that of LinE (14). These results directly demonstrated a new type of ring cleavage pathway for aromatic compounds, the “hydroquinone (HQ) pathway.” Although reports of the HQ pathway have been limited, we consider it one of the major degradation pathways for aromatic compounds whose regulation system for gene expression has been established. However, the regulation system for the genes of the HQ pathway in UT26 is still unknown. In this study, we cloned and characterized a regulatory gene encoding a transcriptional regulator for linD and linE.

FIG. 1.

Proposed assimilation pathway of γ-HCH in S. paucimobilis UT26. Compounds: 1, γ-HCH; 2, γ-pentachlorocyclohexene; 3, 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-1,4-cyclohexadiene; 4, 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene; 5, 2,4,5-trichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1-ol; 6, 2,5-dichlorophenol; 7, 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol; 8, 2,5-DCHQ; 9, CHQ; 10, HQ; 11, acylchloride; 12, γ-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde; 13, maleylacetate; 14, β-ketoadipate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Sphingomonas strains and Escherichia coli were grown on Luria broth (6). The cultures were incubated at 30°C for Sphingomonas strains and at 37°C for E. coli. Antibiotics were used at final concentrations of 50 μg/ml for ampicillin and kanamycin and 25 μg/ml for nalidixic acid.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. paucimobilis | ||

| UT26 | Nalr | 4 |

| UT102 | Nalr Kmr; Tn5-induced mutant of UT26 | 10 |

| E. coli | ||

| JM110 | dam dcm supE hsdR17 thi leu rpsL1 lacY galK galT ara tonA thr tsx Δ(lac-proAB)/F′ [traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15] | 6 |

| MV1190 | Δlac-proAB thi supE Δsrl-recA306::Tn10 F′ traD36 proAB lacI ZΔM15 | 6 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMC1403 | pMB1 replicon; Apr | 18 |

| pHSG399 | pMB9 replicon; Cmr | 19 |

| pUC18 | pMB9 replicon; Apr | 19 |

| pUC19 | pMB9 replicon; Apr | 19 |

| pLR1 | pUC18/HincII + blunted PstI-SmaI fragment containing linR; linR is the same orientation as the lac promoter | This study |

| pMEU1 | pMC1403 carrying 238-bp EcoRI-BamHI fragment containing the upstream region of linE | This study |

| pMEU2 | pMC1403 carrying 163-bp EcoRI-BamHI fragment containing the upstream region of linE | This study |

| pMEU3 | pMC1403 carrying 138-bp EcoRI-BamHI fragment containing the upstream region of linE | This study |

| pMEU1R | pMEU1 carrying PvuII-PvuII fragment of pLR1 at its BalI site | This study |

| pMEU2R | pMEU2 carrying PvuII-PvuII fragment of pLR1 at its BalI site | This study |

| pMEU3R | pMEU3 carrying PvuII-PvuII fragment of pLR1 at its BalI site | This study |

Isolation of DNA.

Plasmid DNA of E. coli was isolated by the alkaline lysis method of Maniatis et al. (6). Total DNAs from Sphingomonas strains were isolated as described previously (9).

Southern blot analysis.

Southern blot analysis was performed with the ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) gene detection system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) according to the protocol provided.

Nucleotide sequence determination.

The nucleotide sequences of a 1.0-kb PstI-SmaI fragment of plasmid pLR1 and the fragments amplified by PCR were determined by the dideoxy chain termination method with the LI-COR (Lincoln, Neb.) model 4000L DNA-sequencing system.

Construction of plasmids for promoter activity assay.

Various lengths of the region upstream of linE followed by the 5′ end of the linE gene were amplified by PCR and fused to the lacZ gene in the same frame on the plasmid pMC1403 (18) to form plasmids pMEU1, pMEU2, and pMEU3. The primers used to amplify the region upstream of linE are LEUP-1 (5′-GCCGAATTCTCGTGCAGCGGCGCTGA-3′), LEUP-2 (5′-GCGGGATCCAGTTGCATCATGATCGCTC-3′), LEUP-3 (5′-GCCGAATTCTATATTCACAATCTG-3′), and LEUP-4 (5′-GCCGAATTCTATGAAGGTCCGC-3′). To amplify the fragments for pMEU1, pMEU2, and pMEU3, primers LEUP-4, LEUP-3, and LEUP-2, respectively, were used in combination with LEUP-1. The resultant plasmids can express the LinE-LacZ fusion protein if the upstream region has promoter activity. To form pMEU1R, pMEU2R, and pMEU3R, the PvuII-PvuII fragment containing Plac-linR was isolated from pLR1 and inserted into the BalI site of each plasmid. To make the BalI sites easily digested, each plasmid was purified from E. coli JM110 (dcm mutant).

β-Galactosidase assay.

E. coli harboring each plasmid was incubated with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (1 mM). The culture was divided, and each substrate was added (10 μM final concentration). After incubation for 2 h, the cells were harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). The cells were disrupted by sonication (Sonifier 250; Branson, Danbury, Conn.) and centrifuged at 12,000 × g. The supernatant was used for the measurement of β-galactosidase activity. The β-galactosidase activity of the cell extract was measured as follows. One hundred microliters of 13.3 mM o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to 400 μl of cell extract. After incubation at 30°C, 250 μl of Na2CO3 solution (1 M) was added to stop the reaction, and the absorbance at 420 nm was measured. The protein concentration of the cell extract was determined by using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. One unit of β-galactosidase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that would hydrolyze 1 nmol of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside in 1 min at 30°C.

RNA slot blot analysis.

Total RNAs of UT26 and UT102 were isolated as described previously (8). 2,5-DCHQ, chlorohydroquinone (CHQ), and HQ were used as inducers at final concentrations of 10 μM. Six micrograms of each RNA was blotted onto the nylon membrane with a PR600 slot blot manifold (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.). Northern blot hybridization was performed as described previously (8).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper were registered in the DDBJ nucleotide sequence database under accession no. AB021863.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cloning and sequencing of the linR gene.

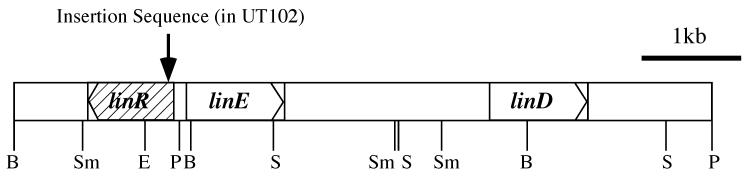

S. paucimobilis UT26 inducibly expresses LinD and LinE activities in the presence of 2,5-DCHQ, substrate for LinD (8) and CHQ, substrate for both LinD and LinE (7, 8). On the other hand, UT102, which is one of the Tn5-induced mutants of UT26, shows faint LinD and LinE activities with or without their substrates (7, 10). It can be considered that this phenotype of UT102 is caused by a mutation in a regulatory gene for the expression of linD and linE. As UT102 has an insertional mutation other than Tn5 in the upstream region of the linE gene (K. Miyauchi, Y. Nagata, and M. Takagi, unpublished data), we determined the nucleotide sequence of this region. The nucleotide sequence of a 1.0-kb PstI-SmaI fragment was determined, and we found an open reading frame (ORF) of 909 bp in this region (Fig. 2). Because this ORF showed similarity to regulatory proteins (see below) and UT102 has an insertion sequence in the N terminus of the ORF (Fig. 2) (Miyauchi et al., unpublished), we designated the ORF linR. The linR gene appears to be divergently transcribed from linE and to use GTG as a start codon. The G+C content of the linR gene is 61.3%, which is similar to those of other lin genes (7, 8, 12, 13) except for linA (53.9%) (3). The deduced molecular mass of LinR is 33.6 kDa.

FIG. 2.

Restriction map of linR and its flanking region. The arrow indicates the position of the insertion mutation in UT102. Abbreviations for restriction enzymes: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; P, PstI; S, SacI; Sm, SmaI.

Homology search analysis of LinR.

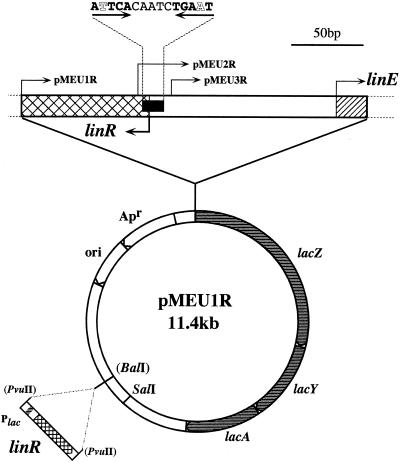

A FASTA homology search revealed that LinR shows similarity to LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs) (16). The proteins which showed high similarity to LinR are as follows: OhbR (29% identity; 69% similarity), a LysR-like protein in an operon for ortho-halobenzoate degradation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain JB2 (AF087482); NahR (31% identity; 68% similarity), a regulatory protein for naphthalene degradation genes in plasmid NAH7 of Pseudomonas putida (J04233); NagR (32% identity; 66% similarity), the regulator of the nag operon in Ralstonia sp. strain U2 plasmid pWWU2 (AF036940-2); NahR (31% identity; 68% similarity), a regulatory protein for naphthalene degradation genes in Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10 (AF039534-4); and SyrM1 (32% identity; 66% similarity), a LysR-like protein in Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 (AE000091-2). The LTTR family is one of the ubiquitous transcriptional regulators in prokaryotes (16), and the transcription of the genes responsible for the degradation of aromatic compounds is often regulated by LTTRs (2). Like known LTTRs, LinR also contains a putative helix-turn-helix structure (S22VSAAARELDLPQPTASHGLARLRKALGDPL52) at its N terminus, which is proposed to be responsible for DNA binding. Like many LTTRs, LinR does not have a glycine residue in the middle of the helix-turn-helix (D31 in LinR), which is conserved among classic helix-turn-helix structures (16), while OhbR, two NahRs, and SyrM have it. In the immediate upstream region of the linE gene, there is a consensus sequence for LTTR binding (ATTCACAATCTGAAT), which is a palindromic TN11A sequence (beginning and end underlined) (16) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Construction of plasmids pMEU1R, pMEU2R, and pMEU3R. The putative LinR-binding site and the start codons of linR and linE are indicated.

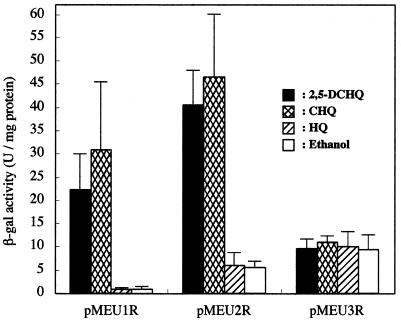

In vivo analysis of the function of LinR.

To characterize the function of LinR in the expression of linE, we constructed the plasmids pMEU1R, pMEU2R, and pMEU3R (Fig. 3). We also constructed pMEU1, pMEU2, and pMEU3, which do not have the linR gene, as a control for each plasmid. E. coli harboring pMEU1, pMEU2, or pMEU3 showed only a faint LacZ activity under every condition we tested (data not shown). E. coli harboring either pMEU1R or pMEU2R showed an increase in LacZ activity in the presence of 2,5-DCHQ and CHQ (23- to 36-fold), while E. coli harboring pMEU3R did not (Fig. 4). These results indicated that the linR gene and the palindromic TN11A sequence which is located upstream of linE are necessary for the upregulation of linE expression. It also seemed that the TN11A sequence is required to repress the expression of the linE gene when the substrates are not present.

FIG. 4.

β-Galactosidase (β-gal) activities of the cell extracts of E. coli harboring pMEU1R, pMEU2R, or pMEU3R. Standard errors calculated from three independent experiments are shown.

Substrate specificity of LinR.

The substrate specificity of LinR was studied with the E. coli in vivo system described above. In addition to 2,5-DCHQ and CHQ, only 2,6-DCHQ gave upregulation activity to E. coli harboring pMEU1R (Table 2). This result indicated that LinR specifically recognizes mono- or di-CHQs among the substrates we tested.

TABLE 2.

Substrate specificity of LinR

| Substrate | β-Galactosidase activity (U/min/mg of protein)a |

|---|---|

| 2,5-DCHQ | 22 ± 7.5 |

| CHQ | 31 ± 14 |

| HQ | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| 2,6-DCHQ | 3.9 ± 1.0 |

| TetrachloroHQ | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

| Catechol | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| 3-Cl catechol | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| 4-Cl catechol | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| Phenol | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| m-Chlorophenol | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| o-Chlorophenol | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| Protocatechuate | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| Gentisate | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| Salicylate | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| 5-Cl salicylate | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

E. coli MV1190(pMEU1R) was used for the assay.

RNA slot blot analysis.

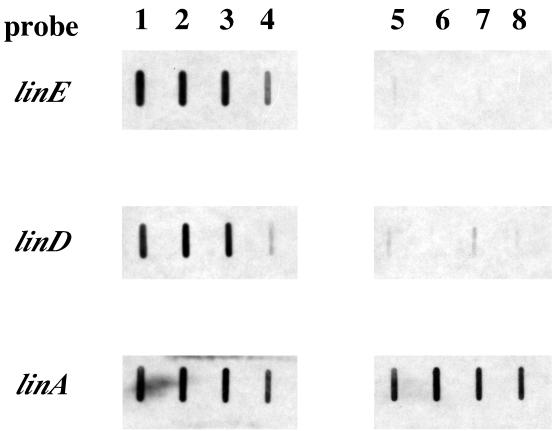

To confirm the function of the linR gene for the expression of linE and linD, RNA slot blot analysis was performed with total RNAs of UT26 and UT102, which is a linR mutant. Figure 5 shows that linD and linE were inducibly expressed in the presence of 2,5-DCHQ, CHQ, and HQ in UT26, while almost no expression of linD and linE was observed in UT102 even in the presence of these substrates. The linA gene, which is constitutively expressed regardless of the presence of the substrates (4), was used as a control. This result indicated that HQ worked as an inducer for linD and linE expression in UT26 (Fig. 5) in addition to 2,5-DCHQ and CHQ, while it did not in the E. coli in vivo system (Fig. 4 and Table 2), suggesting a difference between the permeabilities of HQ in Sphingomonas and E. coli. The possibility that the intermetabolite of HQ works as an inducer in UT26 could not be excluded. However, we can conclude that CHQs are direct substrates of LinR at least, because E. coli does not have activity for conversion of CHQs. Like LinR, the inducer of NahR for the expression of naphthalene-degradative genes is an aromatic compound, salicylate (17), while that of CatR for the expression of catechol-degradative genes is cis,cis-muconate, which is the ring cleavage product of catechol (15). The BenM protein, which regulates the expression of the ben operon in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1, responds to both aromatic compounds and ring cleavage products, i.e., benzoate and cis,cis-muconate (1). It would be very interesting to know why these substrates are selected as the inducers for the regulation system of each degradation pathway.

FIG. 5.

RNA slot blot analysis of total RNAs of UT26 (lanes 1 to 4) and UT102 (lanes 5 to 8) incubated with 2,5-DCHQ (lanes 1 and 5), CHQ (lanes 2 and 6), HQ (lanes 3 and 7), and ethanol (lanes 4 and 8). The probes used are also shown.

HQ pathway.

The results described above indicate that the linR gene is necessary for the inducible expression of linE and linD. Because (C)HQs are specific substrates not only for LinD and LinE but also for LinR (Fig. 4 and 5 and Table 2), the genes encoding these three proteins seem to constitute a specific system for the degradation of (C)HQs, while the gene expression of some dehalogenases for xenobiotic haloalkanes is constitutive (5). The existence of a well-established degradation system strongly suggests that the HQ pathway is one of the major pathways for the degradation of aromatic compounds. linD and linE are considered to form an operon for the following reasons, although we could not detect the band corresponding to the predicted length for the putative linE-linD operon by Northern blot analysis (data not shown). First, the linD and linE genes are located close to each other. Second, the expression of linD is induced simultaneously with that of linE (Fig. 5). Third, we could not identify an obvious terminator sequence between the linE and linD genes. We are trying to identify other genes which belong to this operon.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

This work was performed using the facilities of the Biotechnology Research Center, The University of Tokyo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collier, L. S., G. L. Gaines III, and E. L. Neidle. 1998. Regulation of benzoate degradation in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 by BenM, a LysR-type transcriptional activator. J. Bacteriol. 180:2493-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz, E., and M. A. Prieto. 2000. Bacterial promoters triggering biodegradation of aromatic pollutants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:467-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imai, R., Y. Nagata, M. Fukuda, M. Takagi, and K. Yano. 1991. Molecular cloning of a Pseudomonas paucimobilis gene encoding a 17-kilodalton polypeptide that eliminates HCl molecules from γ-hexachlorocyclohexane. J. Bacteriol. 173:6811-6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imai, R., Y. Nagata, K. Senoo, H. Wada, M. Fukuda, M. Takagi, and K. Yano. 1989. Dehydrochlorination of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-BHC) by γ-BHC-assimilating Pseudomonas paucimobilis. Agric. Biol. Chem. 53:2015-2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen, D. B., J. E. Oppentocht, and G. J. Poelarends. 2001. Microbial dehalogenation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 7.Miyauchi, K., Y. Adachi, Y. Nagata, and M. Takagi. 1999. Cloning and sequencing of a novel meta-cleavage dioxygenase gene whose product is involved in degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Sphingomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:6712-6719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyauchi, K., S. K. Suh, Y. Nagata, and M. Takagi. 1998. Cloning and sequencing of a 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone reductive dehalogenase gene which is involved in the degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Sphingomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:1354-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagata, Y., R. Imai, A. Sakai, M. Fukuda, K. Yano, and M. Takagi. 1993. Isolation and characterization of Tn5-induced mutants of Pseudomonas paucimobilis UT26 defective in γ-hexachlorocyclohexane dehydrochlorinase (LinA). Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 57:703-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagata, Y., K. Miyauchi, S. K. Suh, A. Futamura, and M. Takagi. 1996. Isolation and characterization of Tn5-induced mutants of Sphingomonas paucimobilis defective in 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone degradation. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 60:689-691. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagata, Y., K. Miyauchi, and M. Takagi. 1999. Complete analysis of genes and enzymes for γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 23:380-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagata, Y., T. Nariya, R. Ohtomo, M. Fukuda, K. Yano, and M. Takagi. 1993. Cloning and sequencing of a dehalogenase gene encoding an enzyme with hydrolase activity involved in the degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Pseudomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:6403-6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagata, Y., R. Ohtomo, K. Miyauchi, M. Fukuda, K. Yano, and M. Takagi. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of a 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase gene involved in the degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Pseudomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 176:3117-3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohtsubo, Y., K. Miyauchi, K. Kanda, T. Hatta, H. Kiyohara, T. Senda, Y. Nagata, Y. Mitsui, and M. Takagi. 1999. PcpA, which is involved in the degradation of pentachlorophenol in Sphingomonas chlorophenolica ATCC39723, is a novel type of ring-cleavage dioxygenase. FEBS Lett. 459:395-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsek, M. R., D. L. Shinabarger, R. K. Rothmel, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1992. Roles of CatR and cis,cis-muconate in activation of the catBC operon, which is involved in benzoate degradation in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 174:7798-7806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schell, M. A. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:597-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schell, M. A. 1985. Transcriptional control of the nah and sal hydrocarbon-degradation operons by the nahR gene product. Gene 36:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapira, S. K., J. Chou, F. V. Richaud, and M. J. Casadaban. 1983. New versatile plasmid vectors for expression of hybrid proteins coded by a cloned gene fused to lacZ gene sequences encoding an enzymatically active carboxy-terminal portion of beta-galactosidase. Gene 25:71-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viera, J., and J. Messing. 1987. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 153:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]