Abstract

Management of teicoplanin (TEIC) therapy based on its free serum concentrations may be crucial for optimizing efficacy and safety. This study investigated the protein-binding variability of TEIC and evaluated predictive models for free TEIC concentrations in patients with various diseases. Additionally, effects of free serum TEIC concentrations on the efficacy and adverse event risk of TEIC therapy were analyzed. Free TEIC concentrations in sera from patients received TEIC treatment were determined via high-performance liquid chromatography followed by ultrafiltration. Therapeutic efficacy was evaluated by monitoring the changes in the serum C-reactive protein levels and fever, and adverse events were evaluated by examining the renal and hepatic functions. No significant correlation was observed between serum albumin concentration and free TEIC percentage; however, free TEIC percentage showed significant interpatient variability. Notably, predictive models based on the serum albumin and total serum TEIC concentrations were inaccurate for patients with different diseases. However, measured free serum TEIC concentrations predicted the therapeutic efficacy and the adverse event risk. In conclusion, our results suggest that TEIC dosage management based on the measured free serum TEIC concentrations, rather than the total or estimated TEIC concentrations, improves the clinical outcomes of patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections.

Keywords: Teicoplanin, Free serum concentration, Serum albumin concentration, Efficacy, Adverse events

Subject terms: Diseases, Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a multidrug-resistant bacterium that shows resistance to many antibacterial agents, including β-lactams1. Teicoplanin (TEIC), which exerts antibacterial effects by inhibiting peptidoglycan polymerization during bacterial cell wall synthesis, is used to treat MRSA infections2. TEIC is a glycopeptide derived from the actinomycete, Actinoplanes teichomyceticus, that consists of six major components (A2-1, A2-2, A2-3, A2-4, A2-5, and A3-1) and four subcomponents (RS-1–4), with A2 being the main component responsible for its antibacterial activity3,4. Vancomycin (VCM), a glycopeptide antibacterial agent, is also used to treat MRSA infections. Several meta-analysis studies have shown that TEIC exhibits comparable antibacterial activity to VCM but with a lower rate of adverse events, including nephrotoxicity5. Therefore, TEIC is more commonly used than VCM to treat MRSA infections in patients with or at risk of renal dysfunction.

TEIC strongly binds to serum albumin, with a protein-binding rate ≥ 90% in humans6. Free serum TEIC is primarily eliminated via renal glomerular filtration. Therefore, serum TEIC concentrations are strongly influenced by both serum albumin concentrations and renal functions. Yano et al. reported that free serum TEIC concentrations are elevated in patients with hypoalbuminemia7. Rowland reported that the total systemic clearance of TEIC increases with decreasing serum albumin concentrations but decreases with worsening renal dysfunction8. As the antibacterial activity of TEIC depends on its free serum concentration, its therapeutic efficacy against MRSA infection varies significantly among patients with hypoalbuminemia and renal dysfunction9,10. TEIC also causes adverse events, such as nephrotoxicity, due to elevated free TEIC concentrations11. MRSA infections are often associated with hypoalbuminemia and renal dysfunction due to advanced age or critical underlying diseases12. These reports highlight the importance of the therapeutic drug monitoring and dosage adjustment of TEIC in individual patients to enhance its therapeutic efficacy and safety.

TEIC dosage is determined based on the target total serum TEIC trough concentration range. Effective total serum TEIC trough concentrations are 15–30 µg/mL for uncomplicated infections13–15 and 20–40 µg/mL for complicated infections16–20. However, for drugs with high protein-binding rates, such as TEIC, free serum drug concentration fluctuates significantly, whereas the total concentration remains unchanged in patients with altered serum albumin concentrations. Therefore, free serum TEIC concentration measurement is crucial to optimize the efficacy and safety of TEIC therapy21. However, measurement of free serum TEIC concentrations requires complex preparations, which is impractical in clinical settings. Therefore, many studies have attempted to predict the free serum TEIC concentrations based on the total serum TEIC and albumin concentrations. For example, Yano et al. developed a simple prediction model for free serum TEIC concentrations with low bias and acceptable error based on the total serum TEIC and albumin concentrations of patients receiving TEIC therapy for gram-positive bacterial infections7. However, Roberts et al. reported that the prediction of free TEIC concentrations by Yano et al. resulted in highly variable differences between the measured and calculated concentrations9. Byrne et al. later developed a complex binding model to estimate the free TEIC concentrations based on the total TEIC concentrations and kinetic parameters21. These parameters include the maximum binding concentration of TEIC, number of TEIC-binding sites per molecule of albumin, molecular weights of TEIC and albumin, and equilibrium dissociation constant for TEIC binding to albumin, as determined by in vitro binding analysis6. However, this model was constructed based on the simulations of patients with hematological malignancies, making its applicability to patients with other diseases unclear.

In this study, we investigated the relationship between serum albumin and free serum TEIC concentrations in patients with various underlying diseases using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). We also examined whether the models of Yano et al.7 and Byrne et al.21 can be used to predict the free serum TEIC concentrations in patients with various diseases. Furthermore, we analyzed the impacts of free serum TEIC concentrations on the efficacy and adverse event risk of TEIC therapy.

Methods

Patients and serum samples

This study included 110 patients (282 samples) with uncomplicated, complicated, or suspected MRSA infections who underwent therapeutic drug monitoring at the Hiroshima University Hospital between March, 2023 and June, 2024. These patients received only TEIC therapy for at least four days, without any other anti-MRSA agents. Patients with TEIC hypersensitivity, pregnancy, and age < 18 years were excluded from the study. Finally, 97 patients (63 males and 34 females; total 231 samples) were analyzed. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University (approval number E2022-0129), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

On days 1–3, patients received a total of five loading doses of TEIC (median dose = 13 mg/kg; interquartile range [IQR] = 10.5–15.4 mg/kg) every 12 h to rapidly increase the serum TEIC concentrations. From day 4 onward, the patients received TEIC (median dose = 7.8 mg/kg; IQR = 5.6–10.1 mg/kg) once daily as a maintenance dose. TEIC dosage was determined by a physician based on the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Blood samples were collected before TEIC administration on days 3–4 during the loading dose period and from day 7 onward during the maintenance dose period. Blood samples were centrifuged at 1,800 g for 15 min at 25 °C to determine the serum trough concentrations of TEIC and albumin. Then, serum samples were stored at –30 °C until use.

Determination of total and free serum TEIC concentrations

TEIC was extracted from the serum as described by Roberts et al.9, with slight modifications. To determine the total serum TEIC concentration, 20 µL of primidone (TOKYO CHEMICAL INDUSTRY CO.,Tokyo, Japan) (250 µg/mL), an internal standard, was added to the serum sample (180 μL), followed by the addition of 400 µL of acetonitrile (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) for deproteinization. After centrifugation at 15,500 g for 10 min at 25 °C, 500 μL of the collected supernatant was mixed with 50 μL of 0.1 M HCl (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) solution and 600 µL of chloroform (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) for 5 min and centrifuged again at 15,500 g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected to determine the TEIC concentration. To determine the free serum TEIC concentration, 1 mL of the serum sample was ultrafiltered using the Centrifree Ultrafiltration Centrifugal Filters with a molecular weight cutoff of 30 kDa (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). The filtered sample was processed using the same method used to estimate the total TEIC concentration.

TEIC concentration was determined using HPLC (Prominence LC-20A series; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with the YMC-Triart C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm; YMC, Kyoto, Japan). The column was maintained at 35 °C. The mobile phase consisted of solvents A (10 mM phosphate buffer [pH 3.0]) and B (acetonitrile). TEIC elution was performed using the following linear gradient: 20% B for 3 min, 20–30% B for 3–5 min, 25% B for 5–15 min, 25–30% B for 15–17 min, 30% B for 17–18 min, and 25% B for 18–25 min at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. TEIC was detected within 14–25 min at 215 nm. Then, 20 µL of sample was injected into the column. Standard solutions for measuring the total and free TEIC concentrations were prepared by adding TEIC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to the commercial (Biowest, Nuaillé, France) or ultrafiltered commercial human serum. Calibration curves for total and free TEIC showed good linearity at 5–75 and 0.5–7.5 μg/mL, respectively. Correlation coefficient was 0.998 for total TEIC and 0.989 for free TEIC. Notably, intra- and inter-day coefficients of variation were < 15% for both. Limits of quantitation were 5 and 0.5 μg/mL for total and free TEIC measurements, respectively.

Estimation of free serum TEIC concentrations

Next, free serum TEIC concentration was estimated using two previously reported equations as indicated below.

|

1 |

The above equation was reported by Yano et al.7. In this equation, Cfree is the free serum TEIC concentration (µg/mL), Ctotal is the total serum TEIC concentration (µg/mL), sAlb is the serum albumin concentration (g/dL), n is the number of TEIC-binding sites per albumin molecule, and Ka is the association constant. According to their analysis, nKa value was 1.78 (g/dL)−1.

|

2 |

|

3 |

In the above equation reported by Byrne et al.21, Cfree is the free serum TEIC concentration (µM), Ctotal is the total serum TEIC concentration (µM), sAlb is the serum albumin concentration (µM), Bmax is the total maximum binding concentration of TEIC (µM), and 1,880 and 66,500 are the molecular weights in grams of TEIC and albumin, respectively. Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant (41.5 μM TEIC concentration) for TEIC binding to albumin, and 1.23 is the number of binding sites per albumin molecule reported for the major component of TEIC (A2-2).

Clinical outcomes

TEIC efficacy is evaluated based on the restoration of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations and alleviation of fever, as reported by Ueda et al.16. This study included 24 patients with body temperature ≥ 37.5 °C and CRP levels ≥ 3 mg/dL who did not receive any antipyretic medications. Amelioration of symptoms was defined as ≤ 30% decrease in CRP levels and ≥ 0.3 °C reduction in fever for at least two consecutive days within 96 h of TEIC administration.

Next, occurrence of adverse events during TEIC therapy was evaluated based on the renal and hepatic functions. This study included 41 patients with eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 who did not receive any antipyretic medications or iodine contrast agents. To detect renal dysfunction, eGFR was calculated in mL/min/1.73 m2 as described in our previous study22. Renal dysfunction is defined as an increase in serum creatinine levels of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or ≥ 1.5-times the baseline level within 48 h or seven days of TEIC administration, respectively23. Hepatic dysfunction was assessed based on the normal hepatic function, which was defined as aspartate aminotransferase levels ≤ 30 IU/L and alanine aminotransferase levels ≤ 30 IU/L according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0)24. If these levels were normal, hepatic dysfunction was defined as an increase in the aspartate and alanine aminotransferase levels by over 3-times the normal levels. If these levels were abnormal, hepatic dysfunction was defined as an increase in the aspartate and alanine aminotransferase levels by over 1.5-times the abnormal levels.

Statistical analyses

Patient data are represented as the medians, IQRs, and ranges. Correlations were analyzed via Pearson’s and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient tests. Agreement between the estimated and measured free serum TEIC concentrations was assessed via Bland–Altman analysis. Differences in serum total (Ctotal) and free (Cfree) TEIC concentrations, as well as Ctotal/minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and Cfree/MIC ratios, across various clinical outcomes were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed using the data of patients showing TEIC efficacy or related adverse events. The cutoff values were optimized by plotting sensitivity and specificity against free TEIC concentrations and selecting the point where both measurements produced the best results as the cutoff value. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using Statcel4 (version 1.0; OMS Publishing Inc., Saitama, Japan) and JMP pro version 18.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 97 patients (63 males and 34 females; 231 samples) were enrolled in this study. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among the 97 patients, 91 (60 males and 31 females) exhibited serum albumin concentrations < 3.6 (g/dL). The median free TEIC percentage was 6.3%, with an IQR of 4.5–8.3% and a range of 1.0–37.4%. Median free TEIC percentage was 6.2% (IQR = 4.1–8.3%; range = 1.5–20.8%) during the loading dose period and 6.3% (IQR = 4.5–8.4%; range = 1.0–37.4%) during the maintenance dose period. These median values are consistent with those reported in previous studies5,9,25. Table 2 shows the underlying diseases in the patients. The types of underlying diseases varied among individuals. Solid tumors were the most common prevalent (34.0%), followed by hematologic malignancies (21.6%), kidney transplantation (11.3%) and liver transplantation (10.3%). Furthermore, some patients had multiple underlying diseases, exhibiting a complex underlying condition.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Median | IQR | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65 | 51–78 | 18–95 |

| Body weight (kg) | 53.5 | 44.5–60.9 | 24.2–101.4 |

| Dose (mg/kg) | 10.2 | 7.2–13.5 | 2.5–22.7 |

| Loading dose period (mg/kg) | 13.0 | 10.5–15.4 | 3.3–20.5 |

| Maintenance dose period (mg/kg) | 7.8 | 5.6–10.1 | 2.5–22.7 |

| sAlb (g/dL) | 2.4 | 2–2.8 | 1.1–4.5 |

| sCr (mg/dL) | 0.83 | 0.52–1.54 | 0.22–6.71 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 66 | 34–110 | 7–305 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 27 | 16–60 | 5–2699 |

| AST (IU/L) | 27 | 17–61 | 7–1889 |

| Trough total concentration (μg/mL) | 24.9 | 20.5–32.1 | 7.0–58.3 |

| Loading dose period (μg/mL) | 24.3 | 19.5–29.1 | 7.0–58.3 |

| Maintenance dose period (μg/mL) | 26.2 | 20.6–33.3 | 8.0–55.3 |

| Trough free concentration (μg/mL) | 1.53 | 1.10–2.13 | 0.50–7.06 |

| Loading dose period (μg/mL) | 1.50 | 1.08–1.95 | 0.50–6.01 |

| Maintenance dose period (μg/mL) | 1.65 | 1.13–2.35 | 0.51–7.06 |

| Free teicoplanin percentage (%) | 6.3 | 4.5–8.3 | 1.0–37.4 |

| Loading dose period (%) | 6.2 | 4.1–8.3 | 1.5–20.8 |

| Maintenance dose period (%) | 6.3 | 4.4–8.3 | 1.0–37.4 |

sAlb serum albumin, sCr serum creatinine, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, ALT serum alanine aminotransferase, AST serum aspartate aminotransferase, IQR interquartile range.

Table 2.

Underlying diseases in patient.

| Underlying diseases | Number (n = 97) |

|---|---|

| Burn injury | 1 (1.0%) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 5 (5.2%) |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 4 (4.1%) |

| Cholangitis | 2 (2.1%) |

| COVID-19 | 1 (1.0%) |

| Crohn’s disease | 2 (2.1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (10.3%) |

| Hematologic malignancies | 21 (21.6%) |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 7 (7.2%) |

| Joint disease | 4 (4.1%) |

| Kidney transplantation | 10 (10.3%) |

| Liver transplantation | 11 (11.3%) |

| Meningitis | 1 (1.0%) |

| Solid tumors | 33 (34.0%) |

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019

Relationship between total and free serum TEIC concentrations

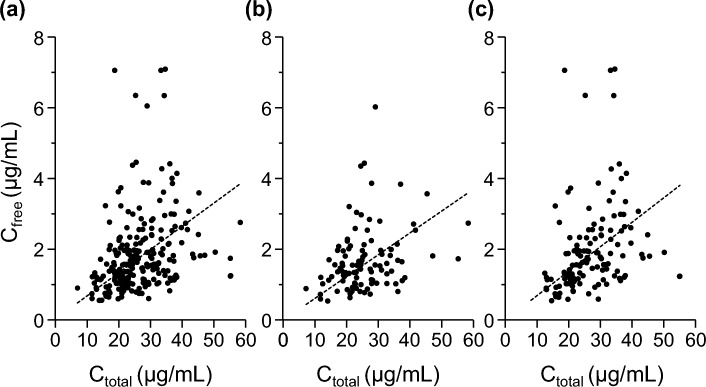

Relationship between total and free serum TEIC concentrations was analyzed using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient test. A significant correlation was observed between the total and free serum TEIC concentrations (r = 0.29; P < 0.01; Fig. 1a). We further analyzed the data separately for the loading and maintenance dose periods. Notably, weak positive correlations were observed during both the loading (r = 0.37; P < 0.01; Fig. 1b) and maintenance (r = 0.30, P < 0.01; Fig. 1c) dose periods.

Fig. 1.

Correlations between total and free serum teicoplanin (TEIC) concentrations in all (a), loading (b), and maintenance (c) dose periods. Dashed line indicates the least-squares fit to the data. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were (a) 0.29, (b) 0.37, and (c) 0.30.

Effect of serum albumin concentration on the free TEIC percentage

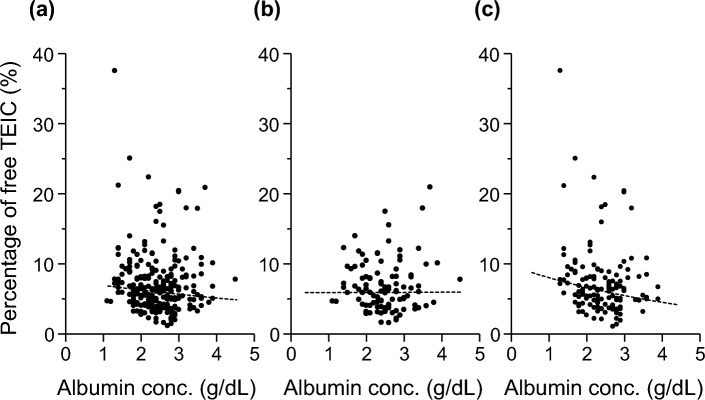

Next, effect of serum albumin concentration on the free TEIC percentage was analyzed using the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient test. Notably, no correlation was observed between the serum albumin concentration and free TEIC percentage (ρ = – 0.12; P = 0.056; Fig. 2a). We further analyzed the data separately for the loading and maintenance dose periods. Consistently, no significant correlation was observed during the loading dose period (ρ = – 0.05; P = 0.63; Fig. 2b); however, a weak negative correlation was observed during the maintenance dose period (ρ = – 0.19; P < 0.05; Fig. 2c). These results suggest that a decrease in the serum albumin concentration is associated with an increase in the free serum TEIC concentration, whereas the free TEIC percentage exhibits substantial interpatient variability.

Fig. 2.

Effects of serum albumin concentrations on the free TEIC percentages in all (a), loading (b), and maintenance (c) dose periods. Dashed line indicates the least-squares fit to the data. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were (a) – 0.12, (b) – 0.05 and (c) – 0.19.

Estimation of free serum TEIC concentrations

To assess whether the free serum TEIC concentration can be estimated from the serum albumin and total serum TEIC concentrations using previously reported equations, we evaluated the agreement between the measured and estimated free serum TEIC concentrations (Fig. 3). Free TEIC concentrations estimated using the equation of Yano et al. were higher than the measured concentrations, and a correlation was observed between the estimated and measured free serum TEIC concentrations (slope = 0.598; intercept = 4.114; r = 0.32; P < 0.05; Fig. 3a). Moreover, Bland–Altman plot revealed that the mean difference between the measured and estimated values was 3.38 μg/mL, showing substantial variability among patients (P < 0.05; Fig. 3b). Free serum TEIC concentrations estimated using the equation of Byrne et al. also revealed a correlation between the measured and estimated values (slope = 0.299; intercept = 1.86; r = 0.32; P < 0.05; Fig. 3c). However, the relationship between the measured and estimated free serum TEIC concentrations was inconsistent (P < 0.05), although the mean difference (0.58 μg/mL) was smaller than that reported by Yano et al. (Fig. 3d). These results suggest that the prediction of free serum TEIC concentrations based on the total serum TEIC and serum albumin concentrations is not sufficiently accurate for patients with underlying diseases.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between the measured and estimated free serum TEIC concentrations. Diagnostic plots of the estimated models of Yano et al. (a) and Byrne et al. (c) for free serum TEIC concentrations. Bland–Altman plot compared the measured and estimated free serum TEIC concentrations using the models of Yano et al. (b) and Byrne et al. (d). Solid line indicates the mean difference, and dashed line indicates the limit of agreement (mean ± 1.96 standard deviation).

Effects of free serum TEIC concentrations on the patient clinical outcomes

Effective total serum TEIC trough concentrations are 15–40 µg/mL in clinical settings12–18. However, in this study, free serum TEIC percentage varied widely, even among patients with the same total serum TEIC concentrations, as shown in Fig. 2. Drug efficacy and toxicity typically depend on its free concentration at the target site. Therefore, we assessed the effect of free serum TEIC concentration on its efficacy. The baseline clinical conditions of patients included in the clinical efficacy analysis are summarized in Table 3. Solid tumors were the most common underlying diseases in both patients with (47.1%) and without (28.6%) effective response. Among patients with effective response, pneumonia (35.3%) was the most frequent infection while urinary tract infection (42.9%) was the most frequent among those without effective response. Two patients with effective response had complicated infection involving both pneumonia and bacteremia whereas one patient without effective response had a complicated infection involving both a urinary tract infection and bacteremia. MRSA was the most commonly isolated Gram-positive organism, identified in 54.2% of the total patients, including 58.8% of those with effective response and 42.9% of those without effective response. No patients had other bacterial infections, received steroids or antibiotics other than TEIC, underwent mechanical ventilation, or had a surgical history within one week prior to TEIC treatment.

Table 3.

Baseline conditions of patients in clinical efficacy analysis.

| Ineffective (n = 7) | Effective (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying diseases | ||

| Burn injury | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 (0%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Crohn’s disease | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 0 (0%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Kidney transplantation | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Liver transplantation | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Septic arthritis | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Solid tumor | 2 (28.6%) | 8 (47.1%) |

| Type of infection | ||

| Bacteremia | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| CRBSI | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Cholangitis | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Cholecystitis | 0 (0%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Infectious endocarditis | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Liver abscess | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Peritonitis | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (14.3%) | 6 (35.3%) |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (42.9%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Isolated Gram-positive organisms | ||

| Enterococcus casseliflavus | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 0 (0%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 (14.3%) | 5 (29.4%) |

| Parvimonas micra | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| MRSA | 3 (42.9%) | 10 (58.8%) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (5.9%) |

No patients had other bacterial infections, received steroids or antibiotics other than TEIC, underwent mechanical ventilation, or had a surgical history within one week prior to TEIC treatment. CRBSI, catheter-related bloodstream infection; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

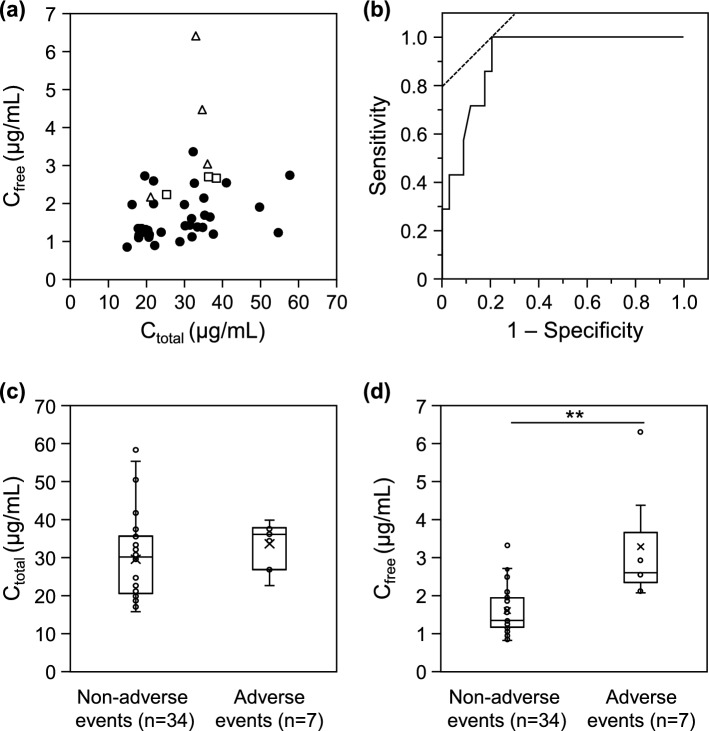

Symptoms were ameliorated in 17 out of 24 (71%) patients within 96 h of TEIC administration (Fig. 4a). ROC curve analysis showed that the free serum TEIC concentration effectively predicted the TEIC efficacy, with an area under the curve of 0.69 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.42–0.96; Fig. 4b). The cutoff value of 1.31 µg/mL, which showed maximum efficiency in using the free serum TEIC concentration to predict the TEIC efficacy, was identified, with a sensitivity of 76.5% and specificity 71.4%. Notably, no significant differences were observed in the total (patients with effective response [median = 24.8 μg/mL and IQR = 19.1–29.3 μg/mL] vs. patients without effective response [median = 21.1 μg/mL and IQR = 19.8–27.7 μg/mL]; P = 0.85; Fig. 4c) and free serum (patients with effective response [median = 1.50 μg/mL and IQR 1.26–1.81 μg/mL] vs. patients without effective response [median = 1.26 μg/mL and IQR 0.85–1.61 μg/mL]; P = 0.15; Fig. 4d) TEIC concentrations. To account for potential differences in TEIC sensitivity (MIC values), we compared the Ctotal/MIC and Cfree/MIC ratios between the two groups. The Ctotal/MIC ratio in patients with effective response (median = 39 μg/mL and IQR = 22.6–55.5 μg/mL) was significantly higher than that in patients with ineffective response ([median = 19.8 μg/mL and IQR = 7.0–26.4 μg/mL]; P < 0.05; Fig. 4e). Similarly, the Cfree/MIC ratio in patients with effective response (median = 2.34 μg/mL and IQR = 1.51–3.45 μg/mL) was also significantly higher than that in patients with ineffective response ([median = 0.85 μg/mL and IQR = 0.54–1.61 μg/mL]; P < 0.01; Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Effects of total and free serum TEIC concentrations on the efficacy of TEIC therapy. Relationships between total and free serum TEIC concentrations and efficacy of TEIC therapy. Open and closed circles indicate the data of patients with (n = 17) and without (n = 7) effective responses to TEIC therapy, respectively (a). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the efficacy of TEIC therapy based on the free serum TEIC concentrations (b). Total (Ctotal) (c) and free (Cfree) (d) serum TEIC concentrations in patients with and without effective responses to TEIC therapy. Total (Ctotal) (e) and free (Cfree) (f) serum TEIC concentrations/minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ratios in patients with and without effective responses to TEIC therapy. Cross marks indicate the mean values of the data. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, significantly different from the patients without effective response.

We further evaluated the relationship between the free serum TEIC concentration and occurrence of adverse events, such as renal and hepatic dysfunction, during TEIC therapy. Renal or hepatic dysfunction was noted in 7 of 41 (17%) patients after TEIC administration, with renal dysfunction in four patients and hepatic dysfunction in three patients (Fig. 5a). ROC curve analysis showed that the free serum TEIC concentration predicted the occurrence of adverse events related to TEIC, with an area under the curve of 0.91 (95% CI = 0.83–1.00; Fig. 5b). The cutoff value was 2.07 µg/mL, with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 79.4%. Moreover, total serum TEIC concentrations were slightly higher in the patients with adverse events (median = 36.1 μg/mL and IQR = 26.8–37.8 μg/mL) than in those without adverse events (median = 30.1 μg/mL and IQR = 20.5–35.6 μg/mL; P = 0.08; Fig. 5c). On the other hand, free serum TEIC concentrations were also significantly higher in the patients with adverse events (median = 2.60 μg/mL and IQR = 2.13–4.37 μg/mL) than in those without adverse events (median = 1.35 μg/mL and IQR = 1.16–1.90 μg/mL; P < 0.01; Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Effects of total and free serum TEIC concentrations on the occurrence of adverse events during TEIC therapy. Relationships between total and free serum TEIC concentrations and occurrence of adverse events during TEIC therapy. Open triangles, open squares, and closed circles indicate the data of patients with renal dysfunction (n = 4), with hepatic dysfunction (n = 3), and without any adverse events (n = 34) during TEIC therapy, respectively (a). ROC curve of the occurrence of adverse events during TEIC therapy based on the free serum TEIC concentrations (b). Total (c) and free (d) serum TEIC concentrations in patients with and without adverse events during TEIC therapy. Cross marks indicate the mean values of the data. **P < 0.01, significantly different from the patients without adverse events.

Discussion

TEIC dosage management based on free serum TEIC concentrations is crucial to enhance the efficacy and safety of TEIC therapy. Therefore, in this study, we measured the free serum TEIC concentrations in patients with various underlying diseases receiving TEIC therapy via HPLC. Relationship between serum albumin and free serum TEIC concentrations revealed that the protein-binding rate of TEIC varied widely among patients and that free serum TEIC concentrations differed, even among patients with similar serum albumin and total TEIC concentrations. Moreover, measured free serum TEIC concentrations were inconsistent with those estimated using the equations established by Yano et al.7 and Byrne et al.21. Notably, measured free serum TEIC concentrations effectively predicted the efficacy and adverse event risk of TEIC therapy. Our results suggest that patients benefit from TEIC dosage management based on the measured free serum TEIC concentrations, rather than the total or free serum TEIC concentrations estimated using previously reported models.

Protein-binding rate of TEIC is ≥ 90%6. Analysis of the relationship between total and free serum TEIC concentrations revealed a weak positive correlation in both the loading and maintenance dose periods (Fig. 1). However, the ratio of free serum TEIC concentration to total serum TEIC concentration varied from 1 to 37.4% across samples (Table 1). Previous studies have shown higher free serum TEIC percentages in patients with hypoalbuminemia than in those with normal serum albumin concentrations7,9,21. In this study, a similar trend was observed in the maintenance dose period; however, patients exhibited higher free TEIC percentages, regardless of the serum albumin concentrations, throughout TEIC therapy (Fig. 2). Although protein binding is not saturated at the serum TEIC concentrations typically observed in clinical settings, drug binding to albumin varies widely depending on the disease stage. For example, drug binding to albumin is decreased in renal and hepatic diseases due to reduced serum albumin concentrations, structural changes in albumin molecules, and displacement by accumulated endogenous substances, such as uremic toxins, bilirubin, and fatty acids26. Furthermore, several diseases and conditions, such as shock, acute head trauma, and cancer, affect the drug binding to albumin26. Association constant (Ka) of TEIC to albumin is reduced in patients with hyperglycemic hypoalbuminemia27. Therefore, protein-binding rate of TEIC is not constant, and free serum TEIC concentrations estimated based on the serum albumin and total serum TEIC concentrations are possibly inaccurate in patients with different underlying diseases. Here, free serum TEIC concentrations estimated using the equations of Yano et al.7 and Byrne et al.21 were different from the actual measured free serum TEIC concentrations (Fig. 3). Similarly, Roberts et al. also reported that the free serum TEIC concentrations estimated using the equation of Yano et al. did not agree with the measured concentrations in patients with hypoalbuminemia9. Our patients were predominantly hypoalbuminemic, with only six exhibiting serum albumin concentrations ≥ 3.6 g/dL, consistent with the report of Roberts et al.9. Byrne et al. used the kinetic parameters of protein binding to estimate the free serum TEIC concentrations from the serum albumin and total serum TEIC concentrations in patients with homological malignancies21. We applied their equations and parameters to estimate the free serum TEIC concentrations in our patients but found no consistency. These underlying diseases such as renal and hepatic diseases, solid tumors, and diabetes mellitus were also observed among our patients analyzed (Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, we speculate that this lack of consistency may be partially attributable to changes in Ka values associated with certain underlying diseases. Estimation of free serum TEIC concentrations based on the serum albumin and total serum TEIC concentrations is not sufficiently accurate for patients with various underlying diseases.

Effective total serum TEIC trough concentrations are 15–40 µg/mL in clinical settings13–20. High TEIC concentrations cause adverse events, such as thrombocytopenia at > 40 µg/mL28 and renal dysfunction at > 60 µg/mL28–30. TEIC management based on the free serum TEIC concentrations can improve the efficacy and reduce any adverse events during therapy. However, the optimal therapeutic concentration range of free serum TEIC remains unknown. Byrne et al. reported the lower and upper limits of the therapeutic target corresponding to the free serum TEIC trough concentrations as 1–2 (1.5) and 3–6 (4.5) mg/L based on the protein-binding rate of 90–95%21. In this study, therapeutic efficacy was observed at free serum TEIC concentrations ≥ 1.31 µg/mL. One of the 17 patients who showed efficacy exhibited a total serum TEIC concentration < 15 µg/mL and free serum TEIC concentration of 1.67 µg/mL, which exceeded the cutoff value. Therefore, increasing the TEIC dosage in such patients does not affect the therapeutic efficacy but possibly increases the risk of adverse events. However, TEIC dosage should be increased at free serum TEIC concentrations < 1.31 µg/mL, even at total serum TEIC concentrations > 15 μg/mL. We found that the cutoff value for the occurrence of adverse events was 2.07 μg/mL. Sugiyama et al. reported the cutoff value for predicting the mean free serum TEIC concentration associated with the occurrence of renal dysfunction as 4.2 µg/mL11. Our cutoff value was lower than that reported by Sugiyama et al. possibly due to the smaller sample size of our study. Although we could not fully exclude potential contributing factors, we excluded the data of patients receiving antipyretic medications and iodine contrast agents to eliminate any impact on renal and hepatic functions. In this study, one patient exhibited a total serum TEIC concentration > 40 μg/mL and free serum TEIC concentration of 1.78 μg/mL, which was lower than the cutoff value. Such patients can possibly maintain their current dose but require close monitoring for any adverse events. In contrast, another patient exhibited a free serum TEIC concentration of 6.31 μg/mL and total serum TEIC concentration < 40 μg/mL. Such patients are at high risk for adverse events. Consistently, adverse events were noted in this patient. These different results are possibly because of the varying protein-binding rates of TEIC among patients, which cannot be determined based on the changes in serum albumin concentrations alone. Therefore, TEIC dosages should be managed based on the measured free serum TEIC concentrations to improve patient clinical outcomes.

No significant difference in free serum TEIC concentrations was observed between patients with and without therapeutic efficacy, suggesting that the MIC of the causative MRSA strain may vary among patients (Fig. 4d). To evaluate the impact of MIC values on therapeutic efficacy, we compared the Ctotal/MIC and Cfree/MIC ratios between the two groups and found that patients with effective response had a significantly higher ratio than those with ineffective response (Fig. 4f). This finding suggests that therapeutic efficacy of TEIC depends not only on free TEIC concentrations but also on bacterial susceptibility. Therefore, TEIC dosing strategies should consider both free drug exposure and MIC values to achieve optimal outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small because the study was conducted at a single institution. Second, this study could not account for potential factors contributing to the clinical outcomes, such as patient age, renal and hepatic functions, and underlying diseases. Therefore, further studies are necessary to determine the optimal therapeutic range of free serum TEIC concentrations that maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse events.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the binding rate of TEIC to serum albumin varied among patients depending on several factors, including the serum albumin concentration and the type of underlying disease. Furthermore, our findings highlight the efficiency of TEIC dosage management based on the measured free serum TEIC concentration and MIC values for MRSA infection treatment.

Author contributions

Y.I., T.T., T.Y. and H.M. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Y.I. and A.M. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. T.Y. and H.M. critically revised the article for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data analyzed/generated in this study are included in the article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lakhundi, S. & Zhang, K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.31, e00020-e118 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parenti, F. Structure and mechanism of action of teicoplanin. J. Hosp. Infect.7(Suppl A), 79–83 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernareggi, A. et al. Teicoplanin metabolism in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.36, 1744–1749 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardone, M. R., Paternoster, M. & Coronelli, C. Teichomycins, new antibiotics from Actinoplanes teichomyceticus nov. sp. II. Extraction and chemical characterization. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo)31, 170–177 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svetitsky, S., Leibovici, L. & Paul, M. Comparative efficacy and safety of vancomycin versus teicoplanin: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.53, 4069–4079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assandri, A. & Bernareggi, A. Binding of teicoplanin to human serum albumin. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol.33, 191–195 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yano, R. et al. Variability in teicoplanin protein binding and its prediction using serum albumin concentrations. Ther. Drug Monit.29, 399–403 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowland, M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of teicoplanin. Clin. Pharmacokinet.18, 184–209 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts, J. A. et al. Variability in protein binding of teicoplanin and achievement of therapeutic drug monitoring targets in critically ill patients: lessons from the DALI Study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents43, 423–430 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brink, A. J. et al. Albumin concentration significantly impacts on free teicoplanin plasma concentrations in non-critically ill patients with chronic bone sepsis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents45, 647–651 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugiyama, K., Hirai, K., Suyama, Y., Furuya, K. & Ito, K. Association of the predicted free blood concentration of teicoplanin with the development of renal dysfunction. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol.80, 597–602 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulldemolins, M., Roberts, J. A., Lipman, J. & Rello, J. Antibiotic dosing in multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Chest139, 1210–1220 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanai, Y. et al. Optimal trough concentration of teicoplanin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther.46, 622–632 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueda, T. et al. High-dose regimen to achieve novel target trough concentration in teicoplanin. J. Infect. Chemother.20, 43–47 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda, T. et al. Enhanced loading regimen of teicoplanin is necessary to achieve therapeutic pharmacokinetics levels for the improvement of clinical outcomes in patients with renal dysfunction. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.35, 1501–1509 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueda, T. et al. Clinical efficacy and safety in patients treated with teicoplanin with a target trough concentration of 20 μg/mL using a regimen of 12 mg/kg for five doses within the initial 3 days. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol.21, 50 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pea, F. et al. Teicoplanin in patients with acute leukaemia and febrile neutropenia: A special population benefiting from higher dosages. Clin. Pharmacokinet.43, 405–415 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seki, M., Yabuno, K., Miyawaki, K., Miwa, Y. & Tomono, K. Loading regimen required to rapidly achieve therapeutic trough plasma concentration of teicoplanin and evaluation of clinical features. Clin. Pharmacol.4, 71–75 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mimoz, O. et al. Steady-state trough serum and epithelial lining fluid concentrations of teicoplanin 12 mg/kg per day in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med.32, 775–779 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews, P. C., Taylor, A., Byren, I. & Atkins, B. L. Teicoplanin levels in bone and joint infections: Are standard doses subtherapeutic?. J. Infect.55, 408–413 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrne, C. J. et al. Population pharmacokinetics of total and unbound teicoplanin concentrations and dosing simulations in patients with haematological malignancy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.73, 995–1003 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaji, H. et al. Assessment of risk of acidosis in patients with mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease treated with intravenous branched-chain amino acid-enriched solution: A propensity score matching analysis. Biol. Pharm. Bull.48, 46–50 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng, X., McMahon, G. M., Brunelli, S. M., Bates, D. W. & Waikar, S. S. Incidence, outcomes, and comparisons across definitions of AKI in hospitalized individuals. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.9, 12–20 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 (U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, 2017). https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm.

- 25.Barbot, A. et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of sequential intravenous and subcutaneous teicoplanin in critically ill patients without vasopressors. Intensive Care Med.29, 1528–1534 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamasaki, K., Chuang, V. T., Maruyama, T. & Otagiri, M. Albumin-drug interaction and its clinical implication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1830, 5435–5443 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enokiya, T., Muraki, Y., Iwamoto, T. & Okuda, M. Changes in the pharmacokinetics of teicoplanin in patients with hyperglycaemic hypoalbuminaemia: Impact of albumin glycosylation on the binding of teicoplanin to albumin. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents46, 164–168 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson, A. P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of teicoplanin. Clin. Pharmacokinet.39, 167–183 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frye, R. F., Job, M. L., Dretler, R. H. & Rosenbaum, B. J. Teicoplanin nephrotoxicity: First case report. Pharmacotherapy12, 240–242 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kureishi, A. et al. Double-blind comparison of teicoplanin versus vancomycin in febrile neutropenic patients receiving concomitant tobramycin and piperacillin: Effect on cyclosporin A-associated nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.35, 2246–2252 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed/generated in this study are included in the article.