Abstract

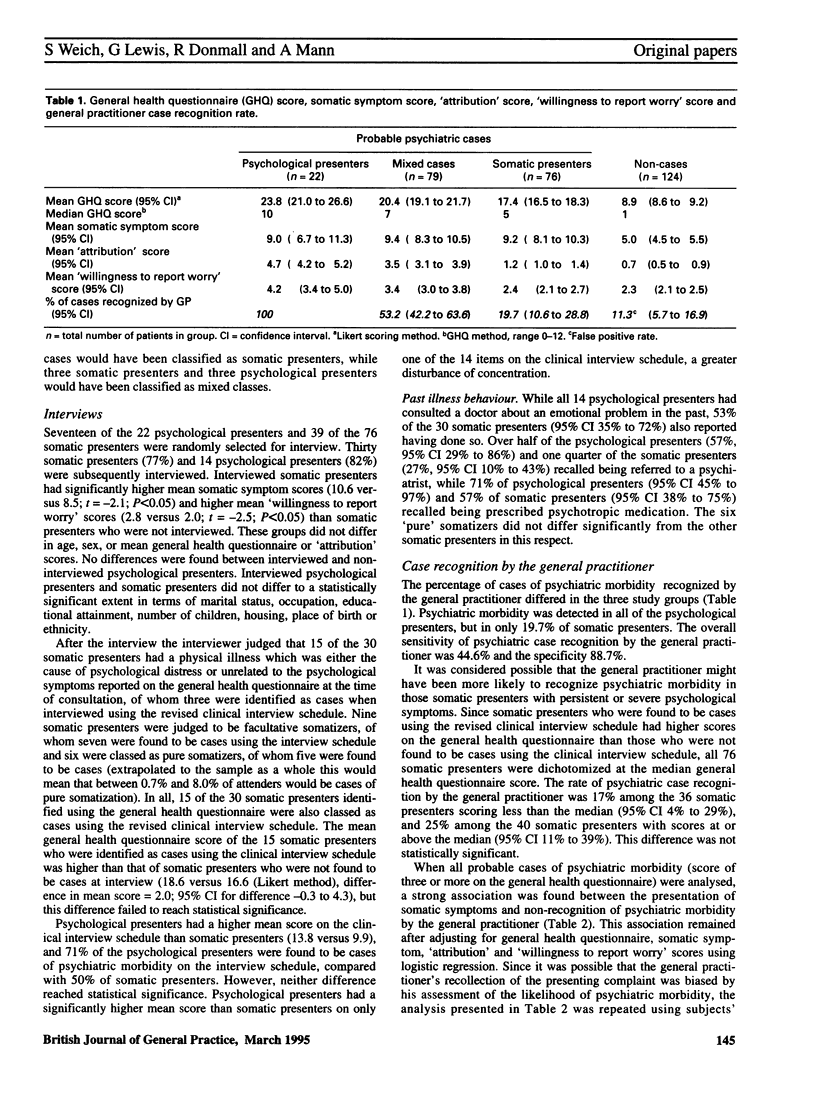

BACKGROUND. Twenty per cent of new illnesses in general practice, and 3% of consecutive attenders, are incident cases of 'pure' somatization. AIM. This study set out to estimate the prevalence of consultations by patients with psychiatric morbidity who present only somatic symptoms (somatic presentation), and to compare this with the likely prevalence of pure somatization. METHOD. A cross-sectional survey of consecutive general practice attenders was carried out. Psychiatric morbidity was measured using the general health questionnaire. Pure somatization was defined as medical consultation for somatic symptoms that were judged by a psychiatrist during an interview to be aetiologically attributable to an underlying psychiatric disorder but which were not recognized as such by the patient. RESULTS. Of attenders 25% were identified as somatic presenters. Of the somatic presenters interviewed one in six were estimated to be pure somatizers, which would extrapolate to 4% of attenders. Though all somatic presenters were probable cases of psychiatric disorder, subjects in this group had lower scores on the general health questionnaire than those who presented with psychological symptoms. General practitioner recognition of psychiatric morbidity was significantly lower among somatic presenters than for other subjects with psychiatric morbidity. CONCLUSION. General practitioner recognition of psychiatric morbidity could be improved for all types of somatic presentation, regardless of the aetiology of patients' somatic symptoms. There is a danger that concentrating attention on pure somatization may mean that psychiatric morbidity in the more common undifferentiated form of somatic presentation will be overlooked.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Banks M. H. Validation of the General Health Questionnaire in a young community sample. Psychol Med. 1983 May;13(2):349–353. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges K. W., Goldberg D. P. Somatic presentation of DSM III psychiatric disorders in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(6):563–569. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges K., Goldberg D., Evans B., Sharpe T. Determinants of somatization in primary care. Psychol Med. 1991 May;21(2):473–483. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700020584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig T. K., Boardman A. P., Mills K., Daly-Jones O., Drake H. The South London Somatisation Study. I: Longitudinal course and the influence of early life experiences. Br J Psychiatry. 1993 Nov;163:579–588. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay-Jones R. A., Murphy E. Severity of psychiatric disorder and the 30-item general health questionnaire. Br J Psychiatry. 1979 Jun;134:609–616. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.6.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N., Lespérance F., Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction. Impact on 6-month survival. JAMA. 1993 Oct 20;270(15):1819–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D. P., Bridges K. Somatic presentations of psychiatric illness in primary care setting. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(88)90048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K. The long-term outcome of psychiatric morbidity detected in general medical patients. J Psychosom Res. 1981;25(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(81)90038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House A. Mood disorders in the physically ill--problems of definition and measurement. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32(4-5):345–353. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(88)90017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W., Ries R. K., Kleinman A. The prevalence of somatization in primary care. Compr Psychiatry. 1984 Mar-Apr;25(2):208–215. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(84)90009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G., Pelosi A. J., Araya R., Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992 May;22(2):465–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipowski Z. J. Somatization: the concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry. 1988 Nov;145(11):1358–1368. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.11.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd G. G. Psychiatric syndromes with a somatic presentation. J Psychosom Res. 1986;30(2):113–120. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(86)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J. N., Goldberg D. P., Hillier V. F. Determinants of the ability of general practitioners to detect psychiatric illness. Psychol Med. 1979 May;9(2):337–353. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayou R. Medically unexplained physical symptoms. BMJ. 1991 Sep 7;303(6802):534–535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6802.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone P. H. Depression increases mortality and morbidity in acute life-threatening medical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34(6):651–657. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90109-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]