Abstract

Thirty-nine Bacillus strains obtained from a variety of environmental and food sources were screened by PCR for the presence of five gene targets (hblC, hblD, hblA, nheA, and nheB) in two enterotoxin operons (HBL and NHE) traditionally harbored by Bacillus cereus. Seven isolates exhibited a positive signal for at least three of the five possible targets, including Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, B. cereus, Bacillus circulans, Bacillus lentimorbis, Bacillus pasteurii, and Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki. PCR amplicons were confirmed by restriction enzyme digest patterns compared to a positive control strain. Enterotoxin gene expression of each strain grown in a model food system (skim milk) was monitored by gene-specific reverse transcription-PCR and confirmed with the Oxoid RPLA and Tecra BDE commercial kits. Lecithinase production was noted on egg yolk-polymyxin B agar for all strains except B. lentimorbis, whereas discontinuous beta hemolysis was exhibited by all seven isolates grown on 5% sheep blood agar plates. The results of this study confirm the presence of enterotoxin genes in natural isolates of Bacillus spp. outside the B. cereus group and the ability of these strains to produce toxins in a model food system under aerated conditions at 32°C.

Bacillus cereus is traditionally considered the most problematic member of the genus Bacillus to the food industry due to the ability of many strains to produce enterotoxins, a topic which has been reviewed recently (9, 11, 14, 24). B. cereus may express at least two distinct multiple-component enterotoxins, the genes for which have been cloned and sequenced (13, 16, 29). A tripartite hemolytic heat-labile enterotoxin designated HBL is the product of an operon that includes hblA, hblD, and hblC, which encode the binding subunit (B) and the L1 and L2 lytic components, respectively (17, 29). Additionally, a nonhemolytic enterotoxin (NHE) operon has recently been characterized (13). The subunits of the B. cereus NHE also include two apparent lytic components, NH1 and NH2, and a third gene product that remains uncharacterized. In addition, a third enterotoxin has been described that is composed of a single 41-kDa subunit (2). The exact role of this toxin, BceT, is still unclear compared to what is known about HBL and NHE subunit enterotoxins.

Consumption of enterotoxigenic Bacillus spp. at high cell densities results in symptoms of diarrhea, with possible vomiting from a separate heat-stable emetic toxin (3, 10). Symptoms may appear 10 to 14 h following ingestion of foodstuffs contaminated with enterotoxigenic strains. Foods most often implicated in the diarrheal syndrome include poultry, cooked meats, soups, desserts, and occasionally fluid and dry milk products (19, 20). The infective dose is high (ca. >106 CFU/g) because symptoms rely on the ingestion of the viable cells or spores, not the preformed toxin, in affected foods (12). Such food may pose a threat to consumers if the product has been temperature abused during shipment or storage or when psychrotrophic strains of Bacillus spp. predominate and grow to high densities prior to consumption (7, 15, 18, 25, 28, 30).

Relatively few researchers have reported the presence of foodborne illness associated with Bacillus spp. other than B. cereus. However, due to the high degree of phylogenetic relatedness among members of this genus, a variety of species must be considered potentially enterotoxigenic, including the well-characterized insect pathogen Bacillus thuringiensis (1, 4, 6, 8). A number of Bacillus spp. have been shown to produce enterotoxins, including Bacillus circulans, Bacillus lentus, Bacillus mycoides, and Bacillus subtilis (5). Moreover, nucleic-acid-based detection assays designed to target enterotoxin genes may not always provide a positive signal when in fact the gene product is expressed, and vice versa (27).

Bacterial isolation.

Some Bacillus spp. used in this study were obtained as known pure cultures from other investigators, while others were isolated from food or environmental sources (Table 1). For natural isolates, 1 g (or 1 ml) of sample was placed into 10 ml of sterile 0.1% peptone (Amresco, Solon, Ohio), and the solution was mixed well and placed into a 70°C water bath for 30 min with occasional mixing. The treated sample was inoculated into sterile skim milk for a 10-h nonselective enrichment (32°C, with shaking) and then pour plated by using Trypticase soy agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) and incubated at 32°C for 24 h. Resulting colonies were restreaked onto GP agar (23) to ensure purity of culture. Gram stains were used to confirm isolation. Unknown strains were identified by M. F. A. Bal'a at the Department of Food Science and Technology, Mississippi State University, Starkville, by using the MIDI system (Microbial ID, Inc., Newark, Del.) and with the API 50 CH system (bioMerieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.).

TABLE 1.

Bacillus strains screened in this study

| Designationa | Species or strain | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 23 | B. amyloliquefaciens | Air |

| 28 | B. cereus | P. Granum, Oslo, Norway |

| 56 | B. cereus 1230-88 | VWR Scientific |

| 19 | B. cereus 0075-95 | P. Granum, Oslo, Norway |

| 22 | B. circulans | Whole milk |

| 33 | B. circulans | Chocolate milk no. 1 |

| 59 | B. circulans | C. E. Cerniglia, NCTR,b Jefferson, Ark. |

| 60 | B. circulans | Aquarium |

| 5 | B. lentimorbis | Tea |

| 6 | B. lentimorbis | Whey protein concentrate |

| 8 | B. lentimorbis | Black pepper |

| 9 | B. lentimorbis | Monosodium glutamate powder |

| 11 | B. lentimorbis | Shrimp homogenate no. 1 |

| 16 | B. lentimorbis | Shrimp homogenate no. 2 |

| 17 | B. lentimorbis | Vitamin supplement powder |

| 27 | B. lentimorbis | Salsa dip |

| 29 | B. lentimorbis | ATCC 14580 |

| 61 | B. lentimorbis | Shrimp homogenate no. 3 |

| 1 | B. licheniformis | Nonfat dry milk powder no. 1 |

| 2 | B. licheniformis | Nonfat dry milk powder no. 2 |

| 3 | B. licheniformis | Nonfat dry milk powder no. 3 |

| 13 | B. licheniformis | Shrimp homogenate no. 1 |

| 15 | B. licheniformis | Shrimp homogenate no. 2 |

| 24 | B. licheniformis | Chocolate milk |

| 38 | B. licheniformis PLR-1 | McKillip et al. (22) |

| 40 | B. marinus | Shrimp homogenate |

| 21 | B. megaterium DSM 319 | F. Meinhardt, Universität Münster, Münster, Germany |

| 37 | B. pasteurii | Soil |

| 62 | B. sporothermodurans MB372 | L. Herman, Government Dairy Research Station, Melle, Belgium |

| 63 | B. sporothermodurans MB374 | L. Herman, Government Dairy Research Station, Melle, Belgium |

| 64 | B. stearothermophilus | C. E. Cerniglia, NCTR, Jefferson, Ark. |

| 20 | B. subtilis | Shrimp homogenate |

| 26 | B. subtilis PY79 | L. Kroos, Michigan State University |

| 30 | B. subtilis 168 | P. Setlow, University of Connecticut |

| 32 | B. subtilis B4A | Washington State University |

| 34 | B. subtilis | ATCC 23856 |

| 65 | B. subtilis | Tabasco sauce |

| 4 | B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki | Soil |

| 7 | B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki | Whey protein concentrate |

The reference number and source for each strain is included. Isolates chosen for further characterization are indicated in boldface.

NCTR, National Center for Toxicological Research.

DNA extraction and PCR.

To screen isolates for the presence of one or more enterotoxin genes, total DNA was extracted by first growing cells to log phase (∼106 CFU/ml) in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco) at 37°C. One milliliter of cells was removed and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 2 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of sterile water, boiled for 5 min, and centrifuged again for 3 min at 12,000 × g. The top, DNA-containing, phase was removed to a new tube, and the DNA was quantitated by using a SmartSpec 3000 spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.).

PCR was performed by using a Gene Cycler (Bio-Rad). The PCRs included 20 pmol of each primer (Table 2), 45 μl of PCR Supermix (all from Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.), and 1 μl (100 ng) of template DNA. Amplification consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 54°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min. A final 7-min 72°C extension followed. PCR products (5 μl) were analyzed on a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and visualized by UV light.

TABLE 2.

Sequences, positions, and target gene designations for PCR primers used to screen Bacillus spp. in this study

| Primer designation | Sequence (5′→3′) | Positions | Amplicon size | Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCF | ATGATAAAAAAAATCCCTTACAA | 61-83 | 1,123 bp | hblA (B subunit of HBL) | 16 |

| BCR | TTTGTGGAGTAACAGTTTCTACTT | 1160-1184 | |||

| L2F | ATGAAAACTAAAATAATGACAG | 1183-1204 | 300 bp | hblC (L2 subunit of HBL) | 29 |

| L2R | ATCCTTTACTTTTTGAATTTAA | 483-1504 | |||

| L1F | ACGACCGCTCAAGAACAAAAAGTA | 2660-2682 | 1 kb | hblD (L1 subunit of HBL) | 29 |

| L1R | GATATTATCCAGTAAATCTGTATA | 637-3660 | |||

| NH1F | GCTCTATGAACTAGCAGGAAAC | 643-664 | 561 bp | nheA (NH1 subunit of NHE) | 13 |

| NH1R | GCTACTTACTTGATCTTCAACG | 1183-1204 | |||

| NH2F | CGGTTCATCTGTTGCGACACG | 2180-2200 | 332 bp | nheB (NH2 subunit of NHE) | 13 |

| NH2R | GATCCCATTGTGTACCATTGG | 2492-2512 |

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was isolated from late-log-phase cultures (optical density at 550 nm of 0.2, corresponding to growth curve densities of 107 CFU/ml) grown in sterile skim milk at 32°C with shaking at 100 rpm. Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified RNA was treated with DNase I by suspension of the pellet in a cocktail consisting of 1 μl of DNase I reaction buffer, 1.5 μl of DNase I (both from Life Technologies), 0.8 μl of RNasin (Promega, Madison, Wis.), and 4.7 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) water (Ambion, Austin, Tex.). The digest was incubated for 45 min at 37°C, inactivated by the addition of 1 μl of EDTA (Life Technologies), and incubated for 10 min at 65°C. The RNA was recovered by extraction once with an equal volume of cold phenol-chloroform, pH 4.7 (Sigma), and precipitation with 0.1 vol of cold 3 M sodium acetate, pH 5.2, and 2.5 vol of cold ethanol, followed by a 4°C centrifugation step at 14,000 × g for 30 min.

The DNase-treated RNA (0.4 μg) was subjected to RT-PCR by resuspension in a reaction mixture consisting of 25 μl of 2× RT reaction mixture, 1 μl of a RT-Taq mixture (reverse transcriptase-Taq polymerase) (both from Life Technologies), 4 μl of the appropriate gene-specific primer set (20 pmol each) (Table 2), and DEPC water to 50 μl. Negative controls included a no-RT and a no-template sample assembled for each reaction set. All reaction mixtures were incubated at 50°C for 45 min, followed by 35 cycles of PCR as described earlier.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism confirmation of amplicons.

To confirm amplicons, each product was digested with a restriction enzyme that generated a known cleavage pattern and compared to the fragments generated in the positive control strain (B. cereus, number 56) by using the same enzyme. The concentration of DNA in each digest (measured in micrograms per microliter) was determined spectrophotometrically and adjusted to 1 μg/μl. The nheA amplicon was digested with PstI, whereas nheB and hblC amplicons were digested with PvuII. RsaI was used to digest the hblC fragment, and hblA was digested with SstI (all enzymes were from Life Technologies). All reaction components were assembled according to the manufacturer's instructions and digested for 90 min at 37°C. The reactions were run on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels (Sigma) and visualized with ethidium bromide and UV light.

Enterotoxin detection.

Enterotoxins were detected by using two commercial immunoassay kits. The BCET-RPLA kit (Oxoid, Ogdensburg, N.Y.) was used to detect HblC in enrichment cultures, while the Tecra BDE kit (Tecra Diagnostics, Frenchs Forest, Australia) detected NheA. Both kits were used on each purified isolate according to the respective manufacturer's instructions.

Hemolysis and lecithinase detection.

Purified cultures of each strain were streaked onto 5% sheep blood agar (LABSCO, Louisville, Ky.) and egg yolk-polymyxin B Agar (Oxoid) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h for detection of discontinuous hemolysis patterns and lecithinase production, respectively.

Bacterial isolation and nucleic acid assays.

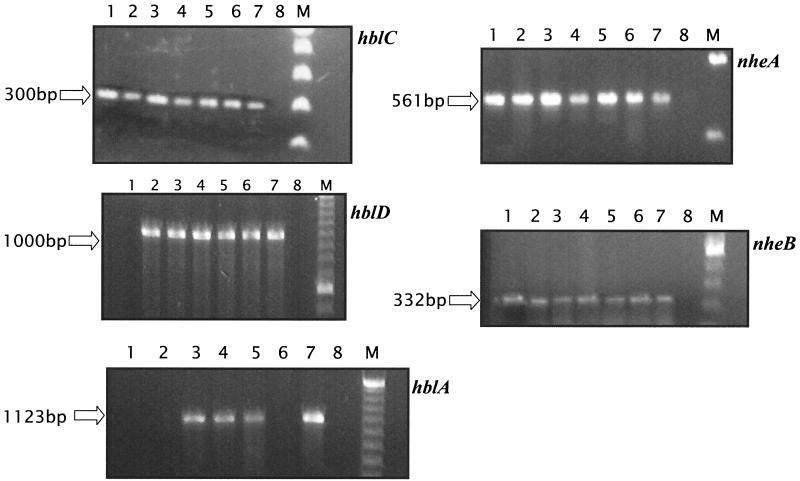

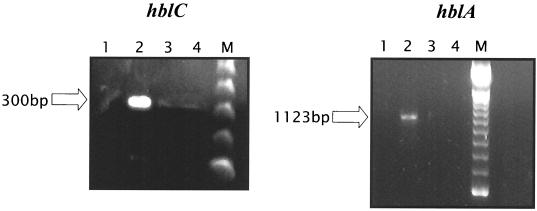

Thirty-nine Bacillus strains were isolated by the methods described above or were obtained from others as laboratory strains (Table 1). Each strain is identified with a corresponding number. Enterotoxin gene-specific PCR allowed for seven strains (indicated in boldface type in Table 1) to be identified subsequently as positive for at least one of the five possible toxin gene targets. Specifically, all seven strains were found to harbor the two NHE operon genes and at least one member of the HBL operon (Fig. 1). B. amyloliquefaciens, B. circulans, and both B. cereus strains contained all HBL gene targets. B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki exhibited detectable signal from hblC, nheA, and nheB, and B. lentimorbis and B. pasteurii contained hblC, hblD, nheA, and nheB (Fig. 1). RT-PCR showed detectable expression of hblC and hblA in only one B. cereus strain (Fig. 2). Addition of specific substances, such as magnesium, bovine serum albumin, or dimethyl sulfoxide, in the PCRs or dilution of template to circumvent potential carryover inhibitors did nothing to improve the detection of target transcripts (data not shown). Plate counts on cells at the time of RNA purification confirmed a density of 3.5 × 107 CFU/ml.

FIG. 1.

PCR of amplicons from selected Bacillus spp. grown in BHI broth. Target genes are indicated adjacent to each panel. Lanes 1 to 8, B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki, B. lentimorbis, B. circulans, B. amyloliquefaciens, B. cereus, B. pasteurii, strain number 56 positive control (B. cereus), and negative (no-template) control, respectively. M, low-molecular-mass DNA ladder.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR of isolate number 56 (B. cereus) grown in skim milk under conditions of aeration as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1 to 4, no-RNA control, sample RNA, no-RT control (negative control), and blank lane, respectively. M, molecular weight standard.

For the most part, reports on toxin production by Bacillus spp. other than B. cereus are still confined to members of the B. cereus subgroup, which also includes B. anthracis, B. mycoides, B. pseudomycoides, B. thuringiensis, and B. weihenstephanensis (27). Only one isolate (B. cereus, number 56) produced a positive signal upon RT-PCR on aerated skim milk cultures, and even this strain was positive only for hblC and hblA. Since this strain (among others) appeared positive for all other targets by DNA PCR, poor RT-PCR assay sensitivity is the most likely explanation for the inconsistent results. The food system in which our cells were grown further complicates RNA extraction, as the presence of carryover proteins, fats, and carbohydrates may detrimentally affect enzyme reaction conditions during RT, DNase treatment, and/or DNA amplification. The results of the immunoassays, however, indicate that enterotoxins are indeed being produced in most of the isolates used in our study despite the absence of detectable mRNA in all but one strain. The medium used in this study was selected to simulate a situation involving growth of enterotoxigenic Bacillus spp. in a temperature-abused product. Aeration conditions have previously been shown to maximize toxin expression, particularly in the presence of carbohydrates (7, 30).

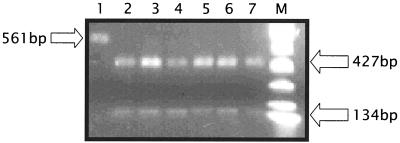

Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis.

To confirm the identities of PCR products, each amplicon was subjected to restriction enzyme digestion, and the banding profile was compared to that of the positive control strain, B. cereus. Products of the digestion of nheA amplicon with PstI resulted in a 134-bp fragment and a 427-bp fragment in all isolates but B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki, which was not digested (Fig. 3). This result is likely due to minor sequence differences within the amplified segment of this strain, one that has been previously documented as being potentially enterotoxigenic (1, 6, 8, 15).

FIG. 3.

Restriction enzyme digestion confirmation of nheA amplicons from each strain following DNA PCR. Lanes 1 to 7 are loaded as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

The nheB amplicon digestion using PvuII for all strains showed fragments of 114 and 197 bp, and the hblD product from all strains except for number 4 generated bands at 742 and 260 bp after digestion with PvuII (data not shown). RsaI digestion of the hblC amplicon from all strains resulted in fragments of 119 and 202 bp, and hblA amplicon digestion using SstI for B. circulans, B. amyloliquefaciens, and both B. cereus strains resulted in 584- and 600-bp fragments (data not shown). All of the digestion products except for the nheB amplicon from isolate number 4 were consistent with patterns obtained from the positive control B. cereus (Fig. 3).

Enterotoxin detection, hemolysis, and lecithinase production.

Each of the seven enterotoxigenic Bacillus spp. was subjected to the two commercial immunoassays as described above. All were positive for NheA, and all but B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki were positive for HblC.

For all enterotoxigenic strains, discontinuous beta hemolysis was apparent following incubation on sheep blood agar plates. Lecithinase production on egg yolk-polymyxin B agar was observed from all strains except B. lentimorbis and B. cereus. Hsieh et al. (17) found discontinuous hemolysis patterns on sheep blood agar and BCET-RPLA assay results to be highly correlated with the presence of the hblA gene in most but not all of some 100 Bacillus spp. tested. However, results from this study and others indicate a lack of reliability in the presence of one marker alone in determining the virulence of Bacillus strains. For example, PCR results for enterotoxigenic Bacillus spp. may not necessarily correlate with immunoassay results, and vice versa. Mantynen and Lindstrom (21) developed a PCR assay targeting hblA and noted general agreement between this assay and the commercial RPLA assay but not between this assay and the BDE enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit results. Another study, by Pruβ et al. (27), found that, although hblA is broadly distributed among members of the B. cereus group, Southern blot hybridization occasionally occurred in the absence of a PCR product. Another study screened a total of 186 Bacillus strains for emetic toxin and HBL toxin production, biochemical characteristics, and ribotyping patterns (26). Approximately one-fifth of the strains screened, including enterotoxigenic isolates, were lecithinase negative. Collectively, these studies emphasize the need to design assays for Bacillus spp. that do not rely on a single virulence determinant.

Similarly, our PCR results detected individual enterotoxin genes in some but not all strains that were subsequently shown to produce enterotoxin when grown in milk. B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki proved to be the most unusual by exhibiting negative results on the commercial RPLA kit, which detects the L2 subunit of the hemolytic enterotoxin, a gene (hblC) for which this isolate demonstrated a positive PCR amplicon. Moreover, B. lentimorbis and B. pasteurii were both positive for hblC and hblD amplicons only but demonstrated similar toxin production as measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. Finally, all seven isolates clearly yielded discontinuous hemolysis patterns on 5% sheep blood agar plates, but both B. lentimorbis and B. cereus were negative for lecithinase production on egg yolk-polymyxin B agar plates. Our data therefore further demonstrate the heterogeneity of specific virulence factors in several natural isolates of Bacillus spp., most of which are not presently categorized within the B. cereus group.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by a grant (awarded to J.L.M.) from the Louisiana Board of Regents.

We are grateful to Farid Bal'a at Mississippi State University for strain typing with the MIDI system and to Catherine Wakeman at Louisiana Tech University for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Hameed, A., and R. Landen. 1994. Studies on Bacillus thuringiensis strains isolated from Swedish soils: insect toxicity and production of B. cereus-diarrheal-type enterotoxin. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 10:406-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agata, N., M. Ohta, Y. Arakawa, and M. Mori. 1995. A novel dodecadipepsipeptide, cereulide, is an emetic toxin of Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 129:17-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agata, N., M. Ohta, Y. Arakawa, and M. Mori. 1995. The bceT gene of Bacillus cereus encodes an enterotoxigenic protein. Microbiology 141:983-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ash, C., J. Farrow, M. Dorsch, E. Stackebrandt, and M. Collins. 1991. Comparative analysis of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and related species on the basis of reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:343-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beattie, S. H., and A. G. Williams. 1999. Detection of toxigenic strains of Bacillus cereus and other Bacillus spp. with an improved cytotoxicity assay. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28:221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson, C. R., D. A. Caugant, and A. B. Kolst. 1994. Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1719-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christiansson, A., A. S. Naidu, I. Nilsson, T. Wadstrom, and H.-E. Pettersson. 1989. Toxin production by Bacillus cereus dairy isolates in milk at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:2595-2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damgaard, P. H., H. D. Larson, B. M. Hansen, J. Bresciani, and K. Jergensen. 1996. Enterotoxin-producing strains of Bacillus thuringiensis isolated from food. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 23:146-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drobniewski, F. A. 1993. Bacillus cereus and related species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 6:324-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finlay, W. J. J., N. A. Logan, and A. D. Sutherland. 2000. Bacillus cereus produces most emetic toxin at lower temperatures. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 31:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granum, P. E. 1997. Bacillus cereus, p. 327-336. In M. P. Doyle, L. R. Beuchat, and T. J. Montville (ed.), Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Granum, P. E., and T. Lund. 1997. Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 157:223-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granum, P. E., K. O'Sullivan, and T. Lund. 1999. The sequence of the non-haemolytic enterotoxin operon from Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 177:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffiths, M. W. 1990. Toxin production by psychrotrophic Bacillus spp. present in milk. J. Food Prot. 53:790-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen, B. M., and N. B. Hendriksen. 2001. Detection of enterotoxic Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis strains by PCR analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:185-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinrichs, J. H., D. J. Beecher, J. D. Macmillan, and B. A. Zilinskas. 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of the hblA gene encoding the B component of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. J. Bacteriol. 175:6760-6766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh, Y. M., S. J. Sheu, Y. L. Chen, and H. Y. Hsen. 1999. Enterotoxigenic profiles and polymerase chain reaction detection of Bacillus cereus group cells and B. cereus strains from foods and food-borne outbreaks. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:481-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaquette, C. B., and L. R. Beuchat. 1998. Survival and growth of psychrotrophic Bacillus cereus in dry and reconstituted infant rice cereal. J. Food Prot. 61:1629-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koneman, E., S. D. Allen, W. M. Janda, P. C. Schreckenberger, and W. C. Winn, Jr. 1997. The aerobic Gram-positive bacilli, p. 651-708. In Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology, 5th ed. Lippincott, New York, N.Y.

- 20.Kramer, J. M., and R. J. Gilbert. 1992. Bacillus cereus gastroenteritis, p. 119-153. In A. T. Tu (ed.), Food poisoning—handbook of natural toxins, vol. 7. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantynen, V., and K. Lindstrom. 1998. A rapid PCR-based test for enterotoxigenic Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1634-1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKillip, J. L., C. L. Small, J. J. Brown, J. F. Brunner, and K. D. Spence. 1997. Sporogenous midgut bacteria of the leafroller, Pandemis pyrusana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Environ. Entomol. 26:1475-1481. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKillip, J. L., and M. A. Drake. 1999. Isolation of “unknown” bacteria in the introductory microbiology laboratory—a new selective medium for Gram-positives. Am. Biol. Teacher 64:610-611. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKillip, J. L. 2000. Prevalence and expression of enterotoxins in Bacillus cereus and other Bacillus spp., a literature review. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 77:393-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Notermans, S., and S. Tatini. 1993. Characterization of Bacillus cereus in relation to toxin production. Neth. Milk Dairy J. 47:71-77. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pirttijarvi, T. S. M., M. A. Andersson, A. C. Scoging, and M. S. Salkinoja-Salonen. 1999. Evaluation of methods for recognising strains of the Bacillus cereus group with food poisoning potential among industrial and environmental contaminants. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22:133-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pruβ, B. M., R. Dietrich, B. Nibler, E. Martlbauer, and S. Scherer. 1999. The hemolytic enterotoxin HBL is broadly distributed among species of the Bacillus cereus group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5436-5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowan, N. J., and J. G. Anderson. 1998. Diarrheal enterotoxin production by psychrotrophic Bacillus cereus present in reconstituted milk-based infant formula (MIF). Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 26:161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan, P. A., J. D. Macmillan, and B. A. Zilinskas. 1997. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the L1 and L2 components of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. J. Bacteriol. 179:2551-2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Netten, P., A. van de Moosdijk, P. van Hoensel, D. A. Mossel, and I. Perales. 1990. Psychrotrophic strains of Bacillus cereus producing enterotoxin. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 69:73-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]