Abstract

In milk, Streptococcus thermophilus displays two distinct exponential growth phases, separated by a nonexponential one, during which proteinase synthesis was initiated. During the second exponential phase, utilization of caseins as the source of amino acids resulted in a decrease in growth rate, presumably caused by a limiting peptide transport activity.

The concentrations in milk of the essential amino acids glutamic acid and methionine (45 and <1 mg per liter, respectively) (7) are far below the requirements of Streptococcus thermophilus (200 and 60 mg per liter, respectively) (9). Consequently, S. thermophilus has to find complementary sources of amino acid in order to grow in milk to high cell densities. The presence of a cell wall proteinase, PrtS (1), an oligopeptide transport system, Ami (2), and a large set of intracellular peptidases (13) enables S. thermophilus to use milk proteins in a pathway similar to that described for lactococci (6, 8). Nevertheless, the relationship between proteolysis and growth of S. thermophilus in milk has not yet been characterized.

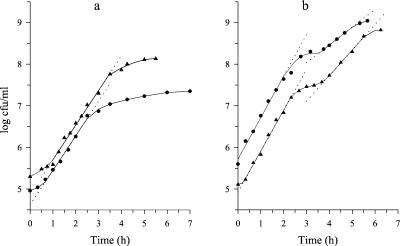

The possible limitation of the growth rate of S. thermophilus related to proteolysis was studied. The growths in milk of eight industrial strains and one laboratory strain were evaluated by spiral plating (Fig. 1). Their ability to produce a functional cell wall proteinase was assessed by plating cultures on Fast-Slow Differential Agar medium (5) (Table 1). The growth of the Prt− strains was clearly exponential, regardless of the strain. However, the growths of all Prt+ strains were not exponential. The standard deviations of the regressions (Sy,x), calculated as described by Snedechor and Cochran (14), ranged between 0.16 (ST16) and 0.29 (ST1), and therefore exceeded the error of the method (3).

FIG. 1.

Growth of Prt− (a) and Prt+ (b) strains of S. thermophilus in milk. Prt− strains were ST7 (•) and ST18 prtS (▴); Prt+ strains were ST1 (•) and ST18 (▴).

TABLE 1.

S. thermophilus strains used in the present study

| Strain | Phenotype on FSDAa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| CNRZ 385 | Prt+ | CNRZ collectionb |

| ST 1 | Prt+ | Industrial |

| ST 2 | Prt+ | Industrial |

| ST 7 | Prt− | Industrial |

| ST 11 | Prt+ | Industrial |

| ST 14 | Prt+ | Industrial |

| ST 16 | Prt+ | Industrial |

| ST 18 | Prt+ | Industrial |

| St18prtS | Prt− | 2 |

| ST18PprtS::PprtS-lux | Prt+ | This work |

Fast-Slow Differential Agar (5).

Collection CNRZ de bactéries lactiques et de bactéries propioniques, INRA, URLGA, 78352 Jouy-en-Josas Cedex, France.

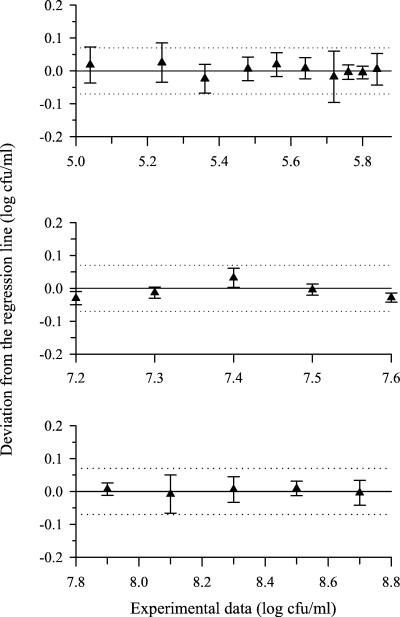

To characterize the growth kinetics of Prt+ strains, nine independent cultures of S. thermophilus ST18 have been performed. Statistical analysis of the Sy,x values made it possible to reject the hypothesis of a single exponential growth phase (P < 0.01). For each experiment, the hypothesis of an exponential growth could be statistically validated for the first and the third portions of the growth curve (up to 107 CFU/ml and from 5 × 107 to 5 × 108 CFU/ml, respectively). The Sy,x values were 0.04 ± 0.02 and 0.05 ± 0.03, respectively (means of the nine repetitions ± confidence limits; P = 0.95), and the deviations of experimental cell counts from the regression lines were randomly distributed around the regression line (Fig. 2). During the intermediate growth phase (between 107 and 5 × 107 CFU/ml), the distribution of the deviations of the experimental data from the regression line indicated a nonexponential growth. A similar statistical analysis was performed on the growth curves of each Prt+ strain, yielding similar results. The presence of two distinct exponential phases, separated by a nonexponential phase, seems to be a common feature of Prt+ strains of S. thermophilus during growth in milk. To our knowledge, it is the first time that such a behavior is depicted for lactic acid bacteria in milk. Although lactococci have been reported to display a biphasic exponential growth in milk, no intermediate growth phase has been detected (7, 11). The hourly growth rates of each exponential growth phase and the duration of the nonexponential growth phase were apparently not independent (Table 2). The longest nonexponential phases (1.33 h or more) were associated with the slowest growth rates during the two exponential phases. The proteolytic activity expressed by the strains, estimated from the amount of 14C-methylated casein hydrolyzed by a cell suspension (10), did not correlate with any of the growth parameters (Table 2). No relationship could be found between the population level at the end of the first exponential phase and the duration of the nonexponential growth phase (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Deviations of the experimental data from the regression lines during growth of S. thermophilus ST18 (mean of nine independent repetitions with confidence limits at P values of 0.95). From top to bottom: first exponential, intermediate, and second exponential growth phases. Dotted lines indicate the standard errors of the spiral plating method.

TABLE 2.

Growth parameters and proteolytic activity of the wild-type proteolytic strains of S. thermophilus

| Strain | Mean (SD) of growth rate (/h)a during:

|

Duration of the nonexponential phase (min) | Proteolytic activityb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st exponential phase | 2nd exponential phase | |||

| CNRZ 385 | 2.8 (0.18) | 1.6 (0.03) | 40 | 27.0 |

| ST1 | 3.2 (0.06) | 1.9 (0.02) | 60 | 4.5 |

| ST2 | 2.3 (0.14) | 1.3 (0.11) | 100 | 11.2 |

| ST11 | 2.8 (0.02) | 1.6 (0.01) | 40 | 10.3 |

| ST14 | 2.4 (0.01) | 1.3 (0.01) | 80 | 18.1 |

| ST16 | 2.5 (0.01) | 1.1 (0.05) | 80 | 10.0 |

| ST18 | 2.9 (0.17) | 2.2 (0.17) | 60 | 10.6 |

From two independent determinations.

Expressed as the percentage of 14C-methylated casein (0.1%, 0.18 μCi/mg) hydrolyzed within 10 min by a cell suspension concentrated to an optical density at 650 nm of 10 (10).

The growth of S. thermophilus ST18 was clearly modified when milk was supplemented with glutamine (2.6 g/liter) and methionine (1.0 g/liter). Only one single exponential growth phase was observed, with a growth rate of 3.3 h−1. Therefore, the diauxic growth of S. thermophilus ST18 in milk could be attributed to the amino acid supply from caseins to the strain. The first stages of growth of S. thermophilus ST18 in control milk (i.e., up to the middle part of the intermediate growth phase) were characterized by a decrease in concentration of several free amino acids of the milk, including Gln, Glu, Thr, Ser, Gly, Ala, Leu, and Ile (Table 3). The concentrations of some free amino acids (mainly Pro, Tyr, Phe, His, and Lys) increased during both the second part of the nonexponential phase and the second exponential growth phase. No clear evolution of the peptide content of the milk could be detected during the first exponential growth phase of S. thermophilus ST18, whereas an accumulation of peptides occurred during the second exponential growth phase (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Free amino acid changes during growth of S. thermophilus ST18 in milk

| Amino acid | Mean (SD) amino acid concn (μM)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | End of the 1st exponential phase | Middle of the nonexponential phase | Beginning of the 2nd exponential phase | End of the 2nd exponential phase | |

| Asn | 2.4b | NDd | ND | ND | ND |

| Asp | 16.7 (1.8) | 14.1 (0.9)e | 14.7 (0.2) | 21.0 (7.3) | 3.6 (0.7)e |

| Gln | 5.9 (0.9) | NDf | ND | ND | 4.2 (1.1)e |

| Glu | 216.1 (7.0) | 207.7 (15.1) | 188.2 (4.6) | 168.2 (8.1)e | 50.4 (4.3)f |

| Thr | 9.3 (2.6) | 6.6 (0.6) | 4.1 (1.2)e | NDe | 2.7 (0.3)f |

| Ser | 10.6 (0.8) | 6.6 (1.4) | 4.4 (1.0) | 2.0b | 4.5 (1.2)e |

| Pro | 21.1 (4.0) | 24.3 (1.1) | 29.6 (2.5) | 53.8 (2.6)f | 96.8 (9.2)e |

| Gly | 70.0 (6.9) | 60.3 (0.8) | 48.2 (5.0) | 17.0 (2.8)e | NDf |

| Ala | 28.4 (3.5) | 26.6 (0.6) | 21.3 (2.6)e | 7.3 (0.9)f | 5.9 (1.1)e |

| Cys | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Met | ND | ND | ND | 5.7 (0.2)f | NDf |

| Leu | 4.8 (0.4) | NDf | ND | 4.0b | ND |

| Ile | 3.9 (0.5) | NDf | ND | 1.9b | ND |

| Val | 12.7 (0.9) | 7.7 (1.8) | 7.5 (0.8) | 5.9b | ND |

| Tyr | 2.5b | ND | ND | 9.9 (0.9)f | 23.0 (1.3)f |

| Phe | ND | ND | ND | 11.4 (4.0)e | 15.4 (4.1) |

| Trp | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| His | 3.1 (1.4) | ND | 4.0b | 8.6 (0.3)e | 12.7 (1.1)e |

| Lys | 13.4 (3.2) | 11.4 (3.3) | 19.1 (5.2)e | 47.9 (3.3)f | 45.6 (17.8) |

| Arg | 13.4 (4.1) | 10.1 (8.8)c | 11.5 (9.9)c | 16.2 (1.7) | NDf |

From three independent determinations.

Not detected in two of three cultures.

Not detected in one of three cultures.

ND, not detected.

Significant change in concentration at a P value of 0.95.

Significant change in concentration at a P value of 0.99.

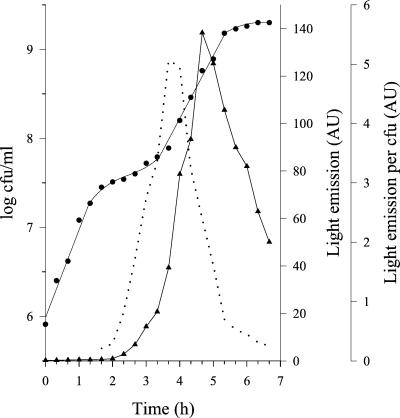

These results suggested that prtS is not expressed during the initial stages of growth of S. thermophilus in milk. To ascertain this hypothesis, the expression of the proteinase was estimated during the growth by using luciferase as a reporter activity (12). The lux genes from Vibrio harvei were inserted into the chromosome of S. thermophilus ST18, under the control of the prtS promoter, using the integrative plasmid poriNewLux (obtained from C. Delorme, Laboratoire de Génétique Microbienne, INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France). The construct was checked by Southern hybridization and by PCR analyses. In order to prevent indirect effects of the pH decrease on the light emission measurement, S. thermophilus ST18PprtS::PprtS -lux was grown in milk at constant pH (6.5). The growth parameters of S. thermophilus ST18PprtS::PprtS -lux were comparable to those of S. thermophilus ST18. No significant luciferase activity could be detected during the first exponential growth phase, indicating the absence of significant synthesis of proteinase (Fig. 3). This first growth phase therefore relies on the utilization of free amino acids (and peptides) as the source of amino acids.

FIG. 3.

Emission of light during growth of S. thermophilus ST18PprtS::PprtS -lux in milk. •, CFU per milliliter; ▴, light units per milliliter (arbitrary units). The dotted line indicates the amount of light produced per CFU.

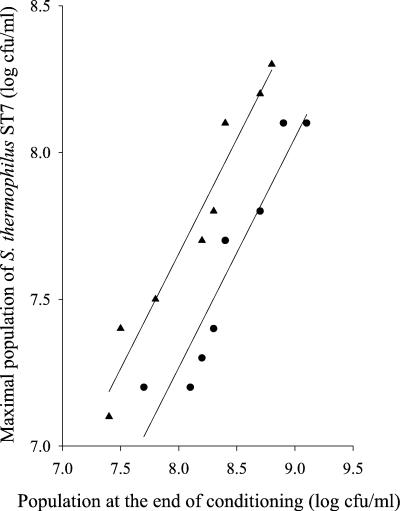

The second exponential growth phase of S. thermophilus ST18 was characterized by a reduction in growth rate, despite the synthesis of PrtS (Fig. 3). The observed stimulation of the growth rate in the presence of glutamine and methionine suggests that the casein utilization process limits the growth rate. However, some free amino acids and peptides accumulate in milk during this growth phase. The ability of these accumulated nitrogen sources to sustain growth of S. thermophilus was analyzed by performing sequential cultures. The milk was first conditioned by culturing either S. thermophilus ST16 or S. thermophilus ST18 (Prt+ strains) to different cellular levels. After the cells were discarded, conditioned milk was inoculated with the Prt− strain S. thermophilus ST7. When the first culture was interrupted during the nonexponential growth phase, no significant growth of S. thermophilus ST7 could be detected in the conditioned milk. In contrast, the Prt− strain was able to grow when the first culture was stopped during the second exponential growth phase. The final population level of S. thermophilus ST7 increased with the population level of the Prt+ strain at the end of the first culture (Fig. 4). It therefore indicates that, during growth in milk, Prt+ strains of S. thermophilus accumulate in the medium amino acids and peptides which are able to sustain growth of a nonproteolytic strain. Consequently, the growth rate during the second exponential growth phase cannot be limited by the rate of casein hydrolysis by PrtS. These experimental results are consistent with a limitation in growth rate due to a limitation in the rate of utilization of proteolysis products, i.e., either by their transport by the Ami system (2) or by their internal cleavage by peptidases. The hypothesis of a growth rate limitation due to the peptidolytic activity is very unlikely, since (i) the intracellular pool of peptidases of S. thermophilus is larger than that of lactococci (13), whose growth rate is not limited by the rate of peptide hydrolysis (4), and (ii) intracellular accumulation of intact peptide has never been observed during peptide transport experiments performed with S. thermophilus (unpublished results). The most probable explanation is a limitation of the growth rate by the rate of transport of proteolysis products. This hypothesis is also consistent with the observation that conditioning milk with the two Prt+ strains ST16 and ST18, which have the same amino acid requirements (9) and express the same level of PrtS activity (Table 2), did not ensure the subsequent growth of a Prt− strain to the same extent (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Final population of S. thermophilus ST7 grown in milk conditioned with a first culture of S. thermophilus ST16 (•) or ST18 (▴), as a function of the cell density at the end of the milk conditioning.

Inactivation of the oligopeptide transport system prevented a significant growth of S. thermophilus in milk, suggesting that proteolysis products are mainly (if not only) oligopeptides (2). The relationship between casein utilization and growth in milk of S. thermophilus therefore presents several similarities with that of Lactococcus lactis (6, 8). First, casein utilization during growth results from a similar pathway, involving two crucial activities, namely proteolysis and oligopeptide transport. Second, the growth rate of both microorganisms is limited by the casein utilization process. Nevertheless, the step of the proteolytic pathway responsible for the limitation in growth rate is not the same for the two bacteria. The growth rate of L. lactis is limited by the rate of proteolysis by PrtP (4), whereas that of S. thermophilus is limited by the rate of utilization of the proteolysis products, presumably translocation of oligopeptides.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Danone Vitapole Recherche, Rhodia-Food, and Sodiaal.

We thank F. Duperray (Danone Vitapole Recherche), A. Sepulchre (Rhodia-Food), P. Ramos (Sodiaal), F. Rul (INRA), and J. Frère (University of Poitiers, Poitiers, France) for helpful discussions. D. Le Bars and P. Courtin (INRA) are acknowledged for amino acid analyses and measurement of proteolytic activities, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fernandez-Espla, M. D., P. Garault, V. Monnet, and F. Rul. 2000. Streptococcus thermophilus cell wall-anchored proteinase: release, purification, and biochemical and genetic characterization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4772-4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garault, P., D. Le Bars, and V. Monnet. 2001. Three binding proteins are involved in the transport of oligopeptide by Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 277:32-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassan, A. I., N. Deschamps, and J. Richard. 1989. Précision des mesures de vitesse de croissance des streptocoques lactiques dans le lait basées sur la méthode de dénombrement microbien par formation de colonies. Etude de référence avec Lactococcus lactis. Lait 69:433-447. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helinck, S., J. Richard, and V. Juillard. 1997. The effects of adding lactococcal proteinase on the growth rate of Lactococcus lactis depend on the type of the enzyme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2124-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huggins, A. M., and W. E. Sandine. 1984. Differentiation of fast and slow milk-coagulating isolates in strains of lactic streptococci. J. Dairy Sci. 67:1674-1679. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juillard, V., S. Helinck, B. Flambard, C. Foucaud, and J. Richard. 1998. Amino acid supply of Lactococcus lactis during growth in milk. Recent Res. Dev. Microbiol. 2:233-252. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juillard, V., D. Le Bars, E. R. S. Kunji, W. N. Konings, J.-C. Gripon, and J. Richard. 1995. Oligopeptides are the main source of nitrogen for Lactococcus lactis during growth in milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3024-3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunji, E. R. S., I. Mierau, A. Hagting, B. Poolman, and W. N. Konings. 1996. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 70:187-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Letort, C., and V. Juillard. 2001. Development of a minimal chemically defined medium for the exponential growth of Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91:1023-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monnet, V., D. Le Bars, and J.-C. Gripon. 1987. Purification and characterization of a cell wall proteinase from Streptococcus lactis NCDO 763. J. Dairy Res. 54:247-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niven, G. W., D. J. Knight, and F. Mulholland. 1998. Changes in the concentrations of free amino acids in milk during growth of Lactococcus lactis indicate biphasic nitrogen metabolism. J. Dairy Res. 65:101-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renault, P., G. Corthier, N. Goupil, C. Delorme, and S. D. Ehrlich. 1996. Plasmid vectors for gram-positive bacteria switching from high to low copy number. Gene 183:175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rul, F., and V. Monnet. 1997. Presence of additional peptidases in Streptococcus thermophilus CNRZ 302 compared to Lactococcus lactis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 82:695-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snedechor, G. W., and W. G. Cochran. 1957. Statistical methods. Iowa State University Press, Ames.