Abstract

Previous in vitro experiments with Desulfovibrio vulgaris strain Hildenborough demonstrated that extracts containing hydrogenase and cytochrome c3 could reduce uranium(VI) to uranium(IV) with hydrogen as the electron donor. To test the involvement of these proteins in vivo, a cytochrome c3 mutant of D. desulfuricans strain G20 was assayed and found to be able to reduce U(VI) with lactate or pyruvate as the electron donor at rates about one-half of those of the wild type. With electrons from hydrogen, the rate was more severely impaired. Cytochrome c3 appears to be a part of the in vivo electron pathway to U(VI), but additional pathways from organic donors can apparently bypass this protein.

Bacteria of the genus Desulfovibrio are able to use a number of electron acceptors, such as sulfate, thiosulfate, sulfur, nitrate, nitrite, and others, for growth and respiration (5, 14, 22). Additionally, various strains have been shown to enzymatically reduce metals such as chromium(VI), manganese(IV), iron(III) (9), technetium(VII) (6, 7), and uranium(VI) (10). Often, the change in the redox state alters the toxicity or solubility of the metals (9). In particular, the microbial reduction of U(VI) has the potential to convert the metal from a soluble form into the insoluble mineral uraninite, thus providing a possible mechanism for the removal of contaminating uranium from groundwaters. Therefore, knowledge of the reductase responsible for this conversion, its regulation, and the flow of electrons available to the enzyme might allow predictions of the efficiency of the process in a defined environment or might provide a basis for the augmentation of soils for remediation.

Progress in identifying the U(VI) reductase of sulfate-reducing bacteria has been made by in vitro experimentation (11). Cell extracts from Desulfovibrio vulgaris strain Hildenborough containing hydrogenase and the tetraheme cytochrome c3 were capable of U(VI) reduction with hydrogen as the source of electrons. Furthermore, when these cell extracts were passed over a cation-exchange column to remove cytochrome c3, the U(VI) reduction capacity of the cell extracts was also removed. The addition of purified cytochrome c3 to the treated extracts restored their metal reduction capability. Thus, the pathway of electron flow to U(VI) in D. vulgaris strain Hildenborough with hydrogen as the donor was suggested to be hydrogenase to cytochrome c3 to U(VI) (11). It remained to be determined whether this was the route of U(VI) reduction by Desulfovibrio in vivo and whether alternate pathways might function. The potential for multiple pathways is supported by biochemical and sequencing data demonstrating that Desulfovibrio species have several c-type cytochromes (1, 3, 12; John Heidelberg, personal communication). In addition, polyhemic c-type cytochromes that have bis-histidinyl coordination of the heme iron atoms have been shown to have a general capacity for the reduction of metal oxyanions (8).

U(VI) reduction by a cytochrome c3 mutant.

To determine if cytochrome c3 was essential for U(VI) reduction, a cytochrome c3 mutant of D. desulfuricans strain G20 (20, 21), named I2, was assayed for its ability to reduce U(VI) enzymatically. The cytochrome c3 mutant I2 was constructed by the integration of a plasmid into the monocistronic chromosomal copy of cycA directed by a 259-bp internal fragment of the cycA gene (16). Cells were grown anaerobically in medium (LS) containing lactate (60 mM) as the primary electron donor and carbon source and sodium sulfate (50 mM) as the terminal electron acceptor (15). Kanamycin (175 μg/ml) was added to all media used to grow I2 to select for maintenance of the inserted plasmid. Since suppressors that restore cytochrome c3 have been shown to accumulate in I2 cultures after extended time in stationary phase (16), special care was taken throughout all manipulations to monitor the status of the mutant. I2 cultures were always started from freezer stocks and were subcultured no more than twice, typically after 16 h at 31°C, before being tested for U(VI) reduction. Western analysis of a subsample of the I2 cultures used in these assays showed that detectable cytochrome c3 had not been restored (data not shown).

To prepare cells for the assay of U(VI) reduction, early-stationary-phase cultures (with an optical density at 600 nm of about 1.0 when grown on complete LS medium) were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min and washed once in an equal volume of anaerobic sodium bicarbonate buffer. This buffer, 2.5 g of NaHCO3 per liter, was always freshly made on the day before use, boiled under a CO2 atmosphere for 20 min to degas it, and taken into an anaerobic chamber (atmosphere of N2-H2, 95:5; Coy Laboratory Inc., Grass Lake, Mich.) while it was still warm. On the day of the assay, the pH of the buffer was adjusted to 7.0 with 5 M HCl. The washed cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of this buffer inside the anaerobic chamber. To initiate the assay, a sample of the culture equivalent to 1.0 mg of total cell protein (2) was transferred to a tube containing 5 ml of an assay solution (1 mM uranyl acetate in anaerobic sodium bicarbonate buffer plus 10 mM Na pyruvate or Na lactate as the electron donor). For experiments investigating H2 as the electron donor, other electron donors were omitted from the medium, the headspace (∼12 ml) of a Hungate tube (Bellco, Vineland, N.J.) was replaced with 100% H2, and the tubes were incubated horizontally to maximize the surface area for gas exchange. All assay solutions were incubated and sampled in the anaerobic chambers, which were maintained at 31°C. During the 24-h assays, the pH of the assay buffer increased less than 0.4 pH unit.

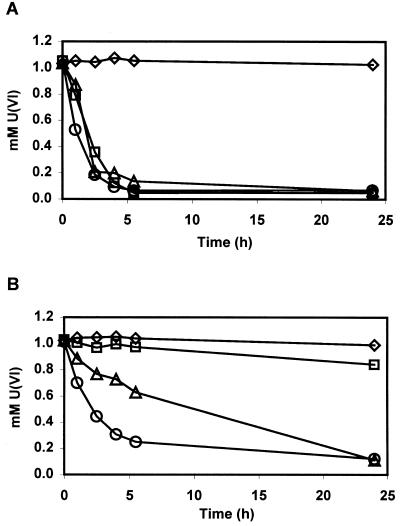

The reduction of U(VI) was followed by the disappearance of U(VI) from the assay solution, as shown with a kinetic phosphorescence analyzer (KPA-10; Chemchek Instruments, Richland, Wash.) (Fig. 1). Samples of 100 μl were removed at the times indicated in Fig. 1, appropriately diluted with anaerobic H2O, and then transferred from the anaerobic chambers in chilled microcentrifuge tubes. The samples were mixed with Uraplex complexant, and the U(VI) concentration was determined with the kinetic phosphorescence analyzer according to the directions of the manufacturer (Chemchek Instruments), essentially by measuring the phosphorescence following excitation by a pulsed nitrogen dye laser and comparing the response to a standard curve. Since spontaneous reoxidation of U(IV) to U(VI) occurs under aerobic conditions, tests were made to determine whether reoxidation occurred during the dilution and reading of samples. None was detected in diluted samples left for over 2 h, although reoxidation did occur after the samples were left standing overnight.

FIG. 1.

U(VI) reduction by D. desulfuricans strain G20 (A) or by the cytochrome c3 mutant I2 (B). All samples have 1 mM uranyl acetate and 200 μg of whole-cell protein/ml. Ten millimolar sodium lactate (○), 10 mM sodium pyruvate (Δ), 1 atm hydrogen gas (□), or no electron donor (◊) was added. Each point is the average of three or more U(VI) measurements from two different experiments. The results are representative of four trials with no reductant and with hydrogen as the electron donor and of a minimum of five trials each with lactate or with pyruvate as the electron donor.

D. desulfuricans strain G20, the parent of the mutant I2, was found to reduce U(VI) enzymatically with lactate, pyruvate, or hydrogen as the electron donor (Fig. 1). The rate of reduction using the organic acids as the electron donor (Table 1) was comparable to the rates calculated from published reports for D. desulfuricans strain Essex 6; those rates varied between 0.75 and 4.2 μmol of U(VI) reduced · mg of cell protein−1 · h−1 (4, 10, 19). D. desulfuricans ATCC 7757 (17) exhibited similar rates [about 5.0 μmol of U(VI) reduced · mg of cell protein−1 · h−1]. To determine whether abiotic reduction occurred at an observable rate, heat-treated cells (prepared in assay buffer in a boiling-water bath for 20 min) were added to an assay mix in the presence of an electron donor or 3 mM sodium sulfide. An initial loss of about 10% of the U(VI) was sometimes observed. This decrease in U(VI) may have been due to a nonenzymatic interaction between the U(VI) and the cell biomass, since no further U(VI) reduction was detected during the 24 h of this assay. No loss of U(VI) was observed with sulfide alone in this time frame.

TABLE 1.

U(VI) reduction rates by D. desulfuricans strains G20 and I2, a cycA mutant of strain G20

| Strain (relevant genotype) | U(VI) reduction rate (avg ± SD) with electron donora

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactateb | Pyruvatec | Hydrogend | |

| G20 (wild type) | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| I2 (cycA mutant) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

Rates are from assays with whole cells (200 μg of cell protein/ml) and were determined from the first 2.5 h of the assay. Rates are measured in micromoles of U(VI) reduced per milligram of cell protein per hour.

Lactate, 10 mM; values are averages of seven or more determinations.

Pyruvate, 10 mM; values are averages of five or more determinations.

Hydrogen, 1 atm; values are averages of four determinations.

The mutant I2 lacking cytochrome c3 reduced U(VI) with hydrogen as the electron donor poorly, if at all (Fig. 1). This observation supports the earlier report that cytochrome c3 was necessary for U(VI) reduction by extracts of D. vulgaris when hydrogen was the source of electrons (12). However, some reduction of U(VI) with hydrogen was consistently seen during assays of I2. Whether this resulted from a bypass of cytochrome c3 or from the accumulation of small numbers of suppressors that restore cytochrome c3 remains to be resolved following the isolation of a deletion mutant. Surprisingly, I2 was still capable of reducing U(VI) with lactate as the electron donor at a rate about one-half of that of the wild type and of reducing U(VI) with pyruvate as the electron donor at a rate of about 33% of that of the wild type (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Clearly, pathways independent of cytochrome c3 function in U(VI) reduction in D. desulfuricans strain G20 when organic acids provide the electrons. Previous experiments using sulfate as the electron acceptor showed that I2 grew at the same rate as the wild type with lactate as the electron donor but was impaired for growth with pyruvate as the sole electron donor (16). This result suggested that cytochrome c3 was apparently involved in the transfer of electrons from pyruvate to sulfate to support growth but was not the sole carrier for electrons from lactate to sulfate. It was therefore expected that the cytochrome c3 mutant would exhibit a greater aberration in U(VI) reduction with pyruvate as the electron donor than with lactate. This was the result observed.

The contribution of toxic metal reduction to the physiology of the microbe remains to be established. Whether the reduction of U(VI) by Desulfovibrio is able to support the organism's growth is still controversial and may be quite strain dependent. Experiments with D. desulfuricans strain Essex 6 (ATCC 29577) were interpreted to show that this strain was unable to grow with U(VI) as the sole electron acceptor, although uranium did not seem to inhibit growth on sulfate until the uranium concentration in the growth medium was greater than 5 mM (10). However, a Desulfovibrio strain (18) and Desulfotomaculum reducens strain MI-1 (13) were reported to grow with U(VI) respiration.

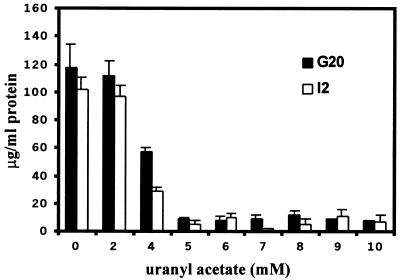

To examine the ability of U(VI) reduction to support growth, it was first necessary to establish the toxicity level of the metal. In addition, a physiological role for heavy metal reduction has been proposed to be detoxification. Both issues were addressed by a comparison of the uranium inhibition of the growth of the parent with that of the I2 mutant to establish the inhibitory levels and to determine whether the mutant was now more sensitive to inhibition by the metal. Early-stationary-phase G20 or I2 cells were subcultured at a 1:10 dilution from LS medium into LS medium supplemented with various concentrations of uranyl acetate. After 24 h of incubation, changes in protein concentrations were used as the measure of growth (2). Both G20 and I2 were capable of growth with up to 4 mM uranyl acetate present in the medium but were completely inhibited at 5 mM (Fig. 2). Similar growth inhibition was seen when uranium was added as uranyl nitrate (data not shown). Thus, the uranium tolerance of these strains was similar to that reported for D. desulfuricans strain Essex 6 (10). Strain G20 consistently reached a slightly higher protein concentration than I2, similar to the 30% ± 15% greater protein concentration that it achieved in LS medium in the absence of uranium (16). Although concentrations of uranyl acetate at or above 5 mM in LS medium inhibited growth, viable cells of both G20 and I2 were recovered at concentrations up to 8 mM. To determine the MIC of uranium on solidified LS medium, 30 μl of early-stationary-phase cells were streaked onto the surface of a plate containing a 0 to 5 mM gradient of uranyl acetate. No difference in levels of growth was detectable; both G20 and I2 failed to grow at or above 3 mM (data not shown). Interestingly, the MICs of uranyl acetate for the D. desulfuricans parental strain G20 and the mutant I2 in both liquid culture and on solidified medium were statistically the same. Thus, a higher rate of reduction did not appear to confer greater resistance.

FIG. 2.

U(VI) sensitivity in D. desulfuricans strains G20 and I2 subcultured onto LS medium supplemented with the indicated amounts of uranyl acetate. Protein measurements were made after 24 h. These values are the averages of results of four trials. T bars indicate standard deviations.

To determine if D. desulfuricans strain G20 was capable of growth with U(VI) as the sole electron acceptor, G20 and I2 cells were grown to early stationary phase on LS medium and then subcultured at a 1:10 dilution into liquid or serially diluted and plated onto solidified medium containing uranyl acetate as the sole electron acceptor. This test medium was modified LS lacking sodium sulfate, yeast extract, cysteine, and sodium carbonate, with sterile uranyl acetate added after the autoclaving. To maximize the potential to observe growth, if any occurred, uranyl acetate was added at subinhibitory concentrations of 4 mM in liquid cultures and 2 mM on solidified medium. There was no measurable protein increase over the level in the no-electron acceptor controls after 24 h on liquid medium for either the parental G20 strain or for the cytochrome c3 mutant I2 (data not shown). Neither G20 nor I2 formed colonies with uranyl acetate-supplemented solidified test medium after 1 month of incubation. Medium supplemented with cysteine to control redox supported the growth by both strains of tiny colonies that were not different in size with uranium present. Reduction of U(VI) could not be shown to support the growth of wild-type G20 or of the cytochrome c3 mutant I2.

Future experiments may reveal an as-yet-unidentified physiological role for U(VI) reduction and the additional components capable of the transfer of electrons to this metal in the absence of the primary tetraheme cytochrome c3. A mutant with a deletion of the gene encoding cytochrome c3 is currently being constructed to address these possibilities.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary sequence data were obtained from John Heidelberg of The Institute for Genomic Research (http://www.tigr.org). Sequencing of Desulfovibrio vulgaris strain Hildenborough was accomplished with support from the U.S. Department of Energy.

This work was supported in part by the Natural and Accelerated Bioremediation Research Program and the Basic Energy Research Program of the U.S. Department of Energy through grants DE-FG02-97ER62495 and DE-FG02-87ER13713, respectively; by the Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station; and by the Molecular Biology Program, University of Missouri—Columbia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aubert, C., G. Leroy, P. Bianco, E. Forest, M. Bruschi, and A. Dolla. 1998. Characterization of the cytochromes c from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans strain G201. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 242:213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford, M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florens, L., and M. Bruschi. 1994. Recent advances in the characterization of the hexadecahemic cytochrome c from Desulfovibrio. Biochimie 76:561-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganesh, R., K. G. Robinson, G. D. Reed, and G. S. Sayler. 1997. Reduction of hexavalent uranium from organic complexes by sulfate- and iron-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4385-4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen, T. A. 1994. Metabolism of sulfate-reducing prokaryotes. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 66:165-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lloyd, J. R., H.-F. Nolting, V. A. Sole, K. Bosecker, and L. E. Macaskie. 1998. Technetium reduction and precipitation by sulphate-reducing bacteria. Geomicrobiol. J. 15:45-58. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lloyd, J. R., J. Ridley, T. Khizniak, N. N. Lyalikova, and L. E. Macaskie. 1999. Reduction of technetium by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans: biocatalyst characterization and use in a flowthrough bioreactor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2691-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lojou, E., P. Bianco, and M. Bruschi. 1998. Kinetic studies on the electron transfer between various c-type cytochromes and iron(III) using a voltametric approach. Electrochim. Acta 43:2005-2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovley, D. R. 1993. Dissimilatory metal reduction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:263-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1992. Reduction of uranium by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:850-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovley, D. R., P. K. Widman, J. C. Woodward, and E. J. P. Phillips. 1993. Reduction of uranium by cytochrome c3 of Desulfovibrio vulgaris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3572-3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moura, J. J. G., C. Costa, M.-Y. Liu, I. Moura, and J. Le Gall. 1991. Structural and functional approach toward a classification of the complex cytochrome c system found in sulfate-reducing bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1058:61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pietzsch, K., B. C. Hard, and W. Babel. 1999. A Desulfovibrio sp. capable of growing by reducing U(VI). J. Basic Microbiol. 39:365-372. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Postgate, J. R. 1984. The sulphate-reducing bacteria, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 15.Rapp, B. J., and J. D. Wall. 1987. Genetic transfer in Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:9128-9130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rapp-Giles, B. J., L. Casalot, R. S. English, J. A. Ringbauer, Jr., A. Dolla, and J. D. Wall. 2000. Cytochrome c3 mutants of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:671-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spear, J. R., L. A. Figueroa, and B. D. Honeyman. 2000. Modeling reduction of uranium U(VI) under variable sulfate concentrations by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3711-3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tebo, B. M., and A. Y. Obraztsova. 1998. Sulfate-reducing bacterium grows with Cr(VI), U(VI), Mn(IV), and Fe(III) as electron acceptors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 162:193-198. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker, M. D., L. L. Barton, and B. M. Thomson. 1998. Reduction of Cr, Mo, Se, and U by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans immobilized in polyacrylamide gels. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wall, J. D., B. J. Rapp-Giles, and M. Rousset. 1993. Characterization of a small plasmid from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and its use for shuttle vector construction. J. Bacteriol. 175:4121-4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weimer, P. J., M. J. Van Kavelaar, C. B. Michel, and T. K. Ng. 1988. Effect of phosphate on the corrosion of carbon steel and on the composition of corrosion products in two-stage continuous cultures of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:386-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widdel, F. 1988. Microbiology and ecology of sulfate- and sulfur-reducing bacteria, p. 469-585. In A. J. B. Zehnder (ed.), Biology of anaerobic microorganisms. Wiley-Interscience, John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.