Highlights

-

•

A novel mRNA vaccine was developed to achieve broad-spectrum protection against Influenza virus.

-

•

The Ub-Re-N mRNA vaccine boosts CD8+ T cell immunity through ubiquitination modification.

-

•

Vaccinated mice had significant reduced lung damage, viral load, and cytokine levels after influenza virus challenge.

-

•

The vaccine demonstrates potential for broad-spectrum protection against H1N1 and B influenza viruses.

Keywords: Influenza virus;Ubiquitin;mRNA vaccine;CD8+ T cell;Immune response

Abstract

Given the persistent antigenic drift of seasonal influenza viruses and the continuous threat of emerging pandemics, there is an urgent necessity to develop novel influenza vaccines capable of conferring broad-spectrum immunity against multiple viral subtypes. CD8+ T cells provide a promising approach to achieving such protection because of their ability to recognize conserved internal antigens. Particularly, the highly cross-reactive internal nucleoprotein of influenza virus demonstrates remarkable efficacy in safeguarding against infection caused by diverse strains. Ubiquitination modification is critical for the differentiation and functionality of CD8+ T cells, thereby modulating the immune response. In this study, three mRNA vaccines were designed using the influenza virus nucleoprotein as an immunogen, including wild-type N protein (WT-N), ubiquitinated wild N protein (Ub-WT-N), and ubiquitinated rearrangement N protein (Ub-Re-N). After immunizing C57BL/6 mice, both WT-N and Ub-WT-N vaccines elicited antibody production, while the Ub-Re-N group exhibited enhanced cellular immune response without inducing antibody production. Subsequently challenged with influenza viruses, the vaccinated mice showed significant protection against mortality and weight loss caused by H1N1 and influenza B strains. Notably, depletion of CD8+ T cells led to a substantial reduction in the protective efficacy of the Ub-Re-N vaccine. In conclusion, the mRNA vaccine encoding Ub-Re-N confers potent defense against influenza virus infection through induction of a robust antigen-specific T cell response.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Influenza is an acute respiratory illness caused by the influenza virus, which according to estimates from the World Health Organization, results in 250,000 to 500,000 fatalities annually (Estrada et al., 2019). The most effective strategy for preventing the influenza virus is vaccination, which induces robust production of neutralizing antibodies that exert their action within the respiratory tract and restrict viral dissemination in the host (Sun et al., 2024). While the commonly employed seasonal influenza vaccine can elicit an immune response against the corresponding strain, its protective efficacy gradually diminishes as the virus undergoes evolutionary changes (Lou et al., 2024; Trombetta et al., 2022). Consequently, regular updates of the strains employed for inactivated vaccines are necessary to address viral mutations (Becker et al., 2021). However, aligning these vaccine strains with circulating strains presents challenges due to unpredictable mutations and lengthy development. Hence, it is crucial to develop a universal influenza vaccine based on the conserved internal antigen of influenza A virus, which would offer broader protection and alleviate the need for annual flu vaccine reformulation.

While neutralizing antibodies are widely acknowledged as the primary immune effectors conferring antiviral protection, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells also play a pivotal role in regulating viral infection (Sun et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2024; La Gruta et al., 2014). In the context of natural influenza virus infection, cross-protective immunity assumes particular significance, with CD8+ T cells playing a crucial role in mediating this protection through their recognition of conserved antigenic components within the virus (Jansen et al., 2019; Koutsakos et al., 2019). For instance, studies have demonstrated that mice infected with specific subtypes of influenza A virus exhibit significant protection against heterologous virus strains, primarily mediated by specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) (Hemann et al., 2019; Fiege et al., 2021). Furthermore, CTL recognition of highly conserved amino acid sequences in the influenza virus proteins (such as NP, M1 protein epitopes) through the MHC I class molecule pathway. This process is triggered after the virus infects the host cell and activates the cytotoxicity of CD8⁺ T cells (such as releasing perforin/granzyme to induce target cell apoptosis) and secreting cytokines such as IFN-γ to inhibit virus replication (Jansen et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021; McGee et al., 2022) and is closely associated with human immune protection (Schotsaert et al., 2022, Tsang et al., 2022). The polyclonal virus-specific CD8+ T cells from European subjects showed cross-reactivity towards H5N1-derived peptides or genes encoding H5N1 NP, indicating a strong and widespread cellular immune response in humans against multiple influenza virus subtypes (Auladell et al., 2019). Moreover, preliminary investigations employing purified recombinant NP (rNP) proteins as vaccine antigens have further substantiated the protective efficacy of NP gene-based vaccines against lethal infections caused by heterologous influenza viruses in mice (Machkovech et al., 2015). The ubiquitination of viral proteins may weaken the levels of antibody response, yet it plays a crucial role in enhancing CTL induction and providing antiviral protection (Rodriguez et al., 1997). Gambino et al. demonstrated that ubiquitination-modified TCI-DNA vaccine conferred complete protection against fetal injury induced by Zika virus (Gambino et al., 2021). Despite potential limitations in antibody specificity, CD8+ T cell responses have shown efficacy in reducing morbidity and mortality associated with emerging viral subtypes, highlighting the need to develop vaccines based on conserved viral components for broader cross-protection (van de Sandt et al., 2019).

The current influenza vaccines should be optimized and designed to effectively activate cross-protective CD8+ T cell responses, thereby enhancing human protection against seasonal influenza virus drift mutations and mitigating the impact of future pandemic strains. The influenza virus nucleoprotein is a highly conserved internal protein in both type A and type B influenza viruses. It has the potential for cross-protection across subtypes and helps to overcome the limitations imposed by the antigenic drift on the viral surface, laying the foundation for the development of broad-spectrum vaccines. The NP protein is rich in MHC I class molecule-restricted epitopes and can be recognized by CD8⁺ T cells, triggering a strong cellular immune response. It plays a crucial role in eliminating infected cells and inhibiting viral replication. In this study, the nucleoprotein of influenza H1 subtype was selected as the target antigen. Three vaccine antigens were designed: wild-type N protein (WT-N), ubiquitinated wild N protein (Ub-WT-N), and ubiquitinated rearrangement N protein (Ub-Re-N). The structural rearrangement aims to induce cellular immunity while attenuating the humoral immune response. Subsequently, these three antigens were combined with mRNA vectors to prepare mRNA vaccines. The LNP-mRNA complex was efficiently delivered to mice using a microfluidic method. A comprehensive analysis of vaccine-mediated humoral and cellular immune responses was conducted, and its effectiveness was validated using animal models. This research offers fresh perspectives and empirical support for the advancement of cellular immunity vaccines, while also laying the groundwork for the creation of universal vaccines targeting various infectious diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice, cells, and viruses

Female C57BL/6 mice (aged 6 weeks) were procured from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd, the animal studies were reviewed and approved by Changchun Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (ethics number IACUC of AMMS-11-2022-016). The HEK 293T cells, pGEM-3Zf-n3 vector, and influenza virus strains: A/Puerto/R/8/34(H1N1), A/Jilin/JYT-01/2018(H1N1), B/Massachusetts/2/2012(Yamagata), B/Jilin/02/2022(Victoria) have been preserved in our lab. All experiments involving live viruses were conducted in biosafety level 2 facilities.

2.2. mRNA preparation and expression

WT-N, Ub-WT-N, and Ub-Re-N were respectively connected to the mRNA vector plasmid (pGEM-3Zf-n3) (Zhuang et al., 2020), and the structure diagram was shown in Fig. 1A and Table S1. mRNA samples were prepared by T7-FlashScribe Transcription Kit in vitro (CELLSCRIPT, USA). To improve the stability in living organisms, resistance against degradation, and effectiveness in translation, a replacement for uridine triphosphate (UTP) was utilized - 1-Methylpseudouridine-5′-triphosphate (TriLink, USA). Afterwards, the samples underwent purification with the MEGAclear Transcription Clean-Up Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and were then capped using the ScriptCap Cap 1 Capping System (CELLSCRIPT, USA).

Fig. 1.

The design mRNA vaccines and immune response in the immunized mice. (A) The diagram depicts the structure of mRNA. To enhance the stability of the Ub/NP complex, alanine was substituted for glycine at the 76th residue in the ubiquitin sequence. (B) The schematic diagram shows the structure of the Ub-Re-N plasmid, where the gene sequence encoding NP protein is divided into three parts while preserving 30 nucleotide bases before and after the cleavage site to ensure that potential epitopes are not destroyed. (C) Recombinant plasmids were transfected into 293T cells, and Western Blot analysis detected protein expression in cell lysates. (D) The total strip density from western blot was quantified using ImageJ software and analyzed with GraphPad Prism. (E) Schematic diagram of immunization of C57BL/6 mice. The experiment used 6-week-old C57BL/6 female mice. Three immunizations were conducted via intramuscular injection, with an interval of 14 days each time, and the dose was 15 μg. Blood was collected at different time points to detect antibody levels, and spleen lymphocytes were isolated on the 42nd day to analyze T cell subsets and cytokines. On the 42nd day, the influenza virus was infected by nasal instillation, and body weight changes were continuously monitored for 14 days. On the 5th day after infection, the viral load in nasal conchae, trachea and lung tissues was detected, and pathological analysis of the lung tissue was performed. (F) Humoral immune response in immunized mice, n = 4. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM, **** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05.

The HEK 293T cells were inoculated and transfected with mRNA following the Xfect TM RNA transfection reagent protocol (TAKARA, Japan). The expression of this protein was validated through western blot analysis. Influenza A Nucleoprotein / NP Antibody (Sino Biological, China) was employed to confirm the protein expression.

2.3. Vaccination and virus challenge

Using microfluidic technology, the mRNA (acetic acid buffer pH 4.0) was mixed with the lipid emulsion (SM-102, DSPC, cholesterol, PEG-lipid, molar ratio 50:10:38.5:1.5) at a constant flow rate at 4 °C. After vortexing and purification through a 0.22 μm filter, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) encapsulation was completed. The mRNA encapsulated withinLNP was delivered into mice, strictly adhering to the methodology established by Yu et al. (2024). Female C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into four groups (WT-N, Ub-WT-N, Ub-Re-N and PBS). Intramuscular injections were administered biweekly for a total of three doses, 15 μg/mouse. Blood samples were collected at different time points to measure antibody levels, and spleen lymphocytes were isolated on day 42 to analyze T cell subsets and cytokines. When collecting blood from mice, the eyes need to be disinfected with 75% ethanol. The head should be tilted at 30°, and the neck should be gently pinched to cause congestion of the orbital venous plexus. The capillary should be inserted at a 45° angle from the inner canthus into the space between the eyelid and the eyeball (approximately 1-2 mm). On the 42th day following the primary immunization, mice were challenged with influenza virus, the influenza virus infection operation was carried out in a BSL-2 biosafety cabinet. The virus solution was diluted to a 10xLD50 dose and then dripped into the bilateral nostrils of the mice. Subsequently, body weight and survival of the mice were monitored daily for two weeks post-virus challenge. On day 5 post-infection, viral loads in nasal conchae, trachea, and lung tissues were measured, and pathological analysis of lung tissue was conducted. For T cell depletion, immunized mice (Ub-Re-N or PBS) were intraperitoneally injected with 200 μg of anti-mouse CD4 antibody, anti-mouse CD8 antibody, IgG2b isotype control antibody (Bio X Cell, USA) on days -2, -1, and 0 prior to the infection, The specific experimental process can be seen in Fig. S1. Then, the spleens were harvested and subjected to flow cytometry analysis on the five day of infection, aiming to ascertain the efficacy of CD4 and CD8 depletion. At the conclusion of the experiment, mice were sedated using isoflurane, euthanized through cervical dislocation, and their lungs along with other organs were harvested for subsequent analysis. The viral load of nasal turbinate, trachea and lung tissue and the pathology of lung tissue were detected.

2.4. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISA plates were coated with 2 μg/mL of NP protein overnight at 4 °C and wash with PBST buffer 5 times (ELISA plate washer, Haimen KYlin-Bell Lab Instruments Co.,Ltd.), followed by blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37 °C for 2 h. Serum samples (dilution 1:100) were added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, wash with PBST buffer 5 times. Then detected using Goat Anti-Mouse IgG Human ads-HRP (1:7500) (SouthernBiotech, USA). for an additional hour. TMB was used as the substrate to develop color, and the reactions were stopped by adding 2M H2SO4. Ultimately, the microtiter plate reader was used to measure the optical density at 450 nm.

2.5. Flow cytometry

After a two-week period subsequent to the final immunization, the spleens of the immunized mice were collected and splenic lymphocytes were isolated. Subsequently, 1 × 105 lymphocytes were incubated in 96-well plates, followed by the addition of 2 μg of NP protein to each well and incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. Following this, a solution containing brefeldin A (100 ×) was added at a volume of 1 μL per well, and the cells were further incubated for 5 h. The resulting cell suspension was collected and subjected to incubation with antibodies (FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD3, APC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4, and PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD8a). After the designated period of incubation, the cells were fixed and their membranes permeabilized before being subsequently exposed to IFN-γ antibodies for evaluation using flow cytometry.

2.6. ELISPOT detection

The ELISPOT Plus: Mouse IFN-gamma (ALP) kits (Mabtech, Sweden) were utilized in accordance with the instructions provided by the manufacturer. In brief, single cell lymphocyte suspension obtained from immunized mice were introduced at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells per well into precoated plate containing the anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody. The cells were then stimulated with NP protein (10 μg/mL) for 24 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, biotin-conjugated anti-IFN-γ detection antibody, streptavidin-HRP, and AEC substrate solution were sequentially added to the plate. Finally, spot quantification was performed using the CTL Spot Reader.

2.7. Viral load and cytokines

The QIAamp virus RNA kit (QIAGEN, Germany) was employed for the extraction of RNA from lung tissue supernatant. RT-qPCR was utilized to quantify viral load and assess pro-inflammatory factors, primers were shown in Table S2.

2.8. Histopathology

The lung tissues were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, followed by the preparation of paraffin-embedded sections. Subsequently, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was employed for histopathological analysis. Finally, images were observed and captured using light microscopy.

2.9. Statistical analysis

To determine statistically significant differences in group means, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparison tests was performed using GraphPad Prism software. In the Fig.s, the data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), significance levels were denoted as **** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Design and antibody level analysis of influenza mRNA vaccine

In this study, wild type NP (WT-N), ubiquitin-modified wild NP (Ub-WT-N), and ubiquitin-modified NP with gene rearrangement (Ub-Re-N) were designed and depicted in Fig. 1A. To enhance antigen processing and presentation, as well as improve subsequent activation of CD8+ T cells, modifications were made to the NP of influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8). It was segmented into three parts for rearrangement, and to preserve CTL epitopes and enhance cellular immunity, 30 amino acid residues flanking the cleavage site were retained in their original form (Fig. 1B). Fusion of antigens with ubiquitin can promote antigen degradation (Fig. 1C and D), indicating that ubiquitin modification can facilitate peptide release from proteins, thereby enhancing antigen presentation.

The immunization protocol of mice is shown in Fig. 1E. Humoral immunity plays an important role in preventing virus entry into host cells and promoting virus clearance (Qi et al., 2022). In our study, the serum IgG antibody level of immunized mice were measured using ELISA. The WT-N group exhibited the most potent humoral immune response, inducing a significant increase in humoral immunity by day 14 after the initial immunization. In contrast, the Ub-WT-N immunization group generated specific antibodies by day 21 following the first immunization, antibody levels were significantly lower compared to those observed in the WT-N immunization group. Importantly, no significant difference was observed in specific antibody levels between the Ub-Re-N vaccine and PBS groups after three doses, likely attributed to the modification of ubiquitin and gene rearrangement(Fig. 1F).

3.2. Cellular immunity analysis of influenza mRNA vaccine

To further investigate the immune effects associated with T cells, we isolated spleen lymphocytes and assessed the expression levels of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes as well as IFN-γ (Fig 2 and Fig S2). In CD3⁺CD4⁺ T cells, the proliferation levels in the WT-N, Ub-WT-N, and Ub-Re-N groups were 1.40-fold (p = 0.0368), 1.41-fold (p = 0.0278), and 1.57-fold (p = 0.0032) of those in the control group, respectively. Specifically, the proliferation level in the Ub-Re-N group was 1.13-fold higher than that in the WT-N group and 1.11-fold higher than that in the Ub-WT-N group (Fig. 2A). In CD3⁺CD8⁺ T cells, the proliferation levels in the WT-N, Ub-WT-N, and Ub-Re-N groups were 2.44-fold (p = 0.0004), 1.97-fold (p = 0.0099), and 2.55-fold (p = 0.0002) of those in the control group, respectively. The proliferation level in the Ub-Re-N group was 1.04-fold higher than that in the WT-N group and 1.30-fold higher than that in the Ub-WT-N group (Fig. 2B). Regarding cytokine-producing T cell subsets, the proportions of CD4⁺IFN-γ⁺ T cells in the WT-N, Ub-WT-N, and Ub-Re-N groups were 3.26-fold (p = 0.0400), 4.26-fold (p = 0.0045), and 5.29-fold (p = 0.0002) of those in the control group, respectively (Fig. 2C). Similarly, the proportions of CD8⁺IFN-γ⁺ T cells in the WT-N, Ub-WT-N, and Ub-Re-N groups were 5.18-fold (p = 0.0016), 3.59-fold (p = 0.0021), and 6.68-fold (p < 0.0001) of those in the control group, respectively (Fig. 2D). Notably, the proportion of CD8⁺IFN-γ⁺ T cells in the Ub-Re-N group was significantly higher than in the other immunized groups, being 1.83-fold (p = 0.0006) higher than that in the WT-N group and 1.86-fold (p = 0.0005) higher than that in the Ub-WT-N group. Furthermore, we quantified the secretion of IFN-γ in immunized mice by ELISpot, which revealed a significantly higher production of IFN-γ in the Ub-Re-N immunized group when compared to other groups (Fig. 2E and F).

Fig. 2.

Cell immune responses after immunization in mice. (A, B) Percentages of CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ spleen T cells via FCM analysis. (C, D) Percentages of CD4+ IFN γ+ and CD8+ IFN γ+ spleen T cells via FCM analysis. (E, F) The number of IFN-γ was tested using ELISPOT assay. All data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, n = 4 (except for E and F are n = 3). *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05.

3.3. mRNA vaccine protects mice from infection with influenza virus

42-day following the initial immunization, the mice were challenged with influenza virus (10 × LD50). Subsequently, for a duration of two weeks, daily monitoring was conducted on both weight and survival rates of the mice (Fig. 3A). The results revealed that mRNA vaccine-induced immunity conferred protection against weight loss and mortality, in stark contrast to control group mice who succumbed to viral attack. Importantly, both Ub-WT-N and Ub-Re-N groups exhibited an impressive protective efficacy rate of 100%. And the vaccinated group exhibited a significant reduction in viral load in the turbinate, trachea, and lungs compared to the control group (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Protective efficacy against lethal challenges with divergent variants of influenza viruses. (A) Body weight and survival curves of mice infected with influenza viruses. (B) Viral loads of mice tissues. Quantification of viral loads in nasal turbinate, trachea, and lung was analyzed following influenza virus challenge. (C) Representative H&E-stained lung sections on the 5th day post-infection (dpi). (D) Assessment of post-mRNA vaccination inflammatory responses. It was conducted by measuring the transcription levels of cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in lung tissue on day 5 post-infection using real-time qPCR. All data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, n = 6 (except for C is n = 3). (**** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05).

The histological examination of lung tissue revealed that vaccinated mice exhibited significantly reduced lung damage, decreased infiltration of inflammatory cells, preserved alveolar structure, and mildly thickened alveolar walls (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest the effective protective effects of Ub-WT-N and Ub-Re-N against influenza virus infection in mice. To assess the preventive efficacy of mRNA vaccine against influenza virus-induced inflammation, we employed RT-qPCR to quantify levels of inflammatory cytokines in the murine lung following influenza virus infection. Our research results show that, compared with the PBS control group, the Ub-Re-N vaccine significantly reduced the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α cytokines in the challenged mice after immunization (Fig. 3D). Although there was no protective effect against B/Jilin/02/2022 (Victoria) mortality and lung tissue damage in mice, a significant reduction in viral load was observed in turbinate, trachea, and lung tissues (Fig. S3). Notably, among all vaccine groups tested, the Ub-Re-N group exhibited superior inhibition of inflammatory factor release and displayed enhanced protection against H1 influenza viruses. These findings suggest that despite not inducing antibody production, the Ub-Re-N vaccine effectively mitigates the associated inflammatory response triggered by influenza virus.

3.4. Ub-Re-N mRNA vaccine induced CD8+ T cells play a key role in protecting mice against influenza virus infection

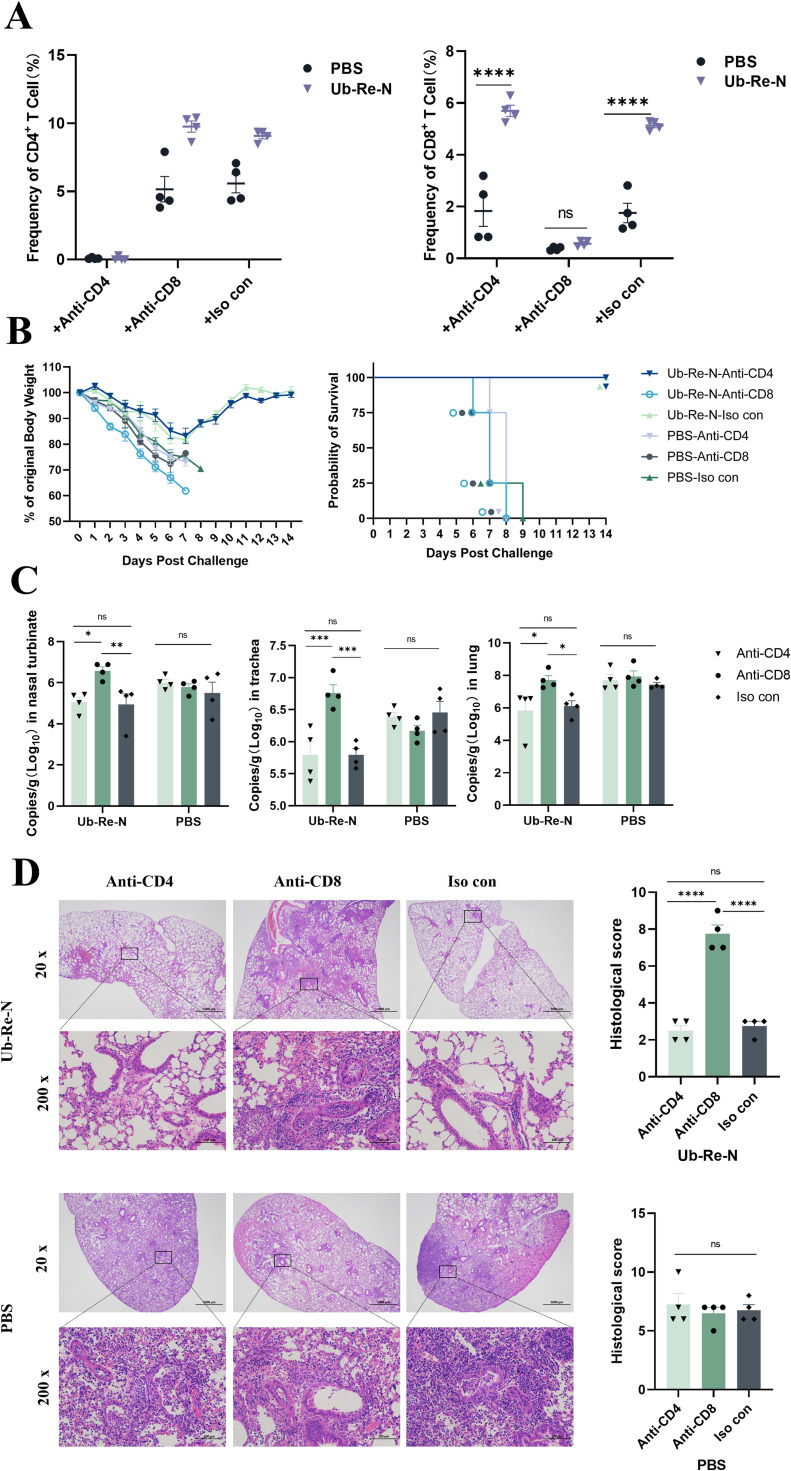

Due to the negligible antibody response induced by Ub-Re-N, we conducted subsequent experiments to investigate the crucial role of T cell response in preventing influenza virus infection. Initially, mice were immunized with either Ub-Re-N or PBS, followed by depletion of their CD4+ and CD8+ T cells using anti-CD4 or anti-CD8a antibodies. Subsequently, these mice were exposed to influenza virus attack. The spleen cells of both Ub-Re-N and PBS treated mice exhibited a complete absence of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (Fig 4A), confirming successful depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. In mice that were immunized with Ub-Re-N and subsequently, depleted of CD8⁺ T cells using anti-CD8 antibodies, all subjects succumbed following challenge with the influenza virus, resulting in a 0% survival rate (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, after depleting CD8+ T cells, significantly elevated levels of influenza virus titers were observed in mice immunized with the Ub-Re-N vaccine as compared to those injected with CD4 antibodies or homologous control antibodies (Fig. 4C). And there was no significant difference in virus titers between Ub-Re-N immunized mice that received anti-CD4 (resulting in CD4+ T cell depletion) and those receiving isotype control antibodies (Fig. 4C). The pathological results of lung tissue were consistent with those of viral load, the histological score of CD8+ T cell depletion significantly higher than CD4+ T cell depletion and Iso con group(Fig. 4D). These findings strongly indicate that the presence of CD8+ T cells is indispensable for preventing influenza virus infection following vaccination with Ub-Re-N.

Fig. 4.

CD8+ T-cells induced by Ub-Re-N mRNA vaccine were essential in protecting mice against infection. The mice received three immunizations and were then injected with anti-CD4, anti-CD8a, or IgG2b isotype control antibodies (200 μg/mouse) three times (-2, -1, and 1 day p.i.) to deplete CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, or without depleting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. After that, they were infected with A/Puerto/R/8/34(H1N1). (A) The quantities of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in splenocytes were quantified by flow cytometry analysis. (B) Body weight and survival curves of mice infected with influenza viruses. (C) Viral loads in nsnal turbinate, trachea and lung was detected by RT-qPCR. (D) Pathological analysis of lung tissue. The data were represented as mean ±SEM, n = 4 (**** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

A highly effective approach to enhance vaccine antigen presentation involves fusion of ubiquitin sequence with the target antigen. Previous studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between rapid ubiquitin-mediated antigen processing and an augmented cell-mediated immune response, with the rate of antigen ubiquitination being associated with the intensity of induced cellular immunity (Bhat et al., 2022; Han et al., 2011). This strategy enables enforced ubiquitination of the antigen, leading to its accelerated degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and subsequent generation of epitope peptides of appropriate length. These epitope peptides bind to MHC Class I molecules and activate an antigen-specific T cell immune response (Boshra et al., 2011; Imai et al., 2008). Such an approach holds great promise for prevention and treatment of viral infections (Zhang et al., 2005; Kloetzel et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2009). For instance, immunization with a ubiquitination-modified SARS-CoV-2 spike protein vaccine (Ub-S DNA) has been shown to confer protection in mice even in the absence of antibodies (Shi et al., 2024). Zhang et al. reported on a novel DNA vaccine targeting "self" antigens expressed in melanoma/melanocytes based on the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Their findings revealed that fusion of ubiquitin genes with target antigens enhances vaccine immunogenicity (Zhang et al., 2005). de Oliveira et al. investigated expression, polyubiquitination, and therapeutic potential of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) E6E7 antigens after fusion with ubiquitin as a novel strategy for cancer vaccines (de Oliveira et al., 2017).

In this study, we successfully fused the ubiquitin gene with the influenza virus N protein and structurally rearranged it to construct a novel mRNA vaccine, named Ub-Re-N. In vaccine development, structural rearrangement of the nucleocapsid N protein is strategically designed to preserve conserved linear epitopes recognized by CD8⁺ T cells, while ubiquitination modification is incorporated to enhance its degradation efficiency within the proteasome (Sharma et al., 2009; Marín-López et al., 2018). Experimental data demonstrated that the Ub-Re-N recombinant vaccine exhibited significantly lower immunogenicity in inducing B cell antibody production compared to the WT-N group. In contrast, the Ub-WT-N vaccine, which underwent ubiquitination modification alone without structural rearrangement, retained a certain level of humoral immune activity. This result aligns with the notion that antigen structural rearrangement may disrupt conformational epitopes recognized by B cells (Park et al., 2023). Consequently, the conformational changes induced by structural rearrangement in Ub-Re-N significantly impaired its ability to stimulate B cell responses. These findings collectively suggest that the attenuation of humoral immune responses is primarily attributed to alterations in antigen conformation, rather than the complete absence of the native N protein. Notably, in the C57BL/6 mouse model, vaccination with Ub-Re-N significantly augmented T cell recruitment and activation, specifically enhancing the secretion of antigen-specific CD8+/IFN-γ+ cells. Furthermore, mice vaccinated with Ub-Re-N exhibited a more robust lymphocyte proliferation response compared to those receiving WT-N or Ub-WT-N vaccines, suggesting that ubiquitination modifications can enhance cellular immunity even when gene rearrangement modifications may attenuate antibody responses. These finding underscores the pivotal role of ubiquitination in promoting cell-mediated immune responses. Importantly, our findings align with previous studies that have established a direct correlation between ubiquitin-mediated antigen treatment and enhanced cell-mediated immune responses (Çetin et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2011; Bhat et al., 2022).

Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells play a pivotal role in the regulation of viral infections by effectively eliminating infected target cells through cytotoxic or non-cytotoxic mechanisms, such as IFN-γ production (Rehermann et al., 2005). Our study demonstrates that vaccination with Ub-Re-N induces a robust immune response mediated by CD8+ T cells, thereby conferring effective protection against influenza virus infection in mice. By conducting a CD8 antibody depletion assay, we validated the indispensable contribution of CD8+ T cells to this protective effect. Notably, upon antibody-dependent CD8 T cell depletion from immunized mice, we observed no significant difference in viral load within tissues compared to the control group when challenged with influenza virus. This finding further underscores the critical role of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in controlling viral infections.

However, this study still has several limitations. The risk of exhaustion or excessive activation of CD8⁺ T cells was not evaluated. The safety issues in this aspect need to be further analyzed in combination with immunological theories, and corresponding strategies should be formulated. This study only evaluated the short-term protective effect of the vaccine within two weeks after challenge. The persistence of immune memory and the long-term protective efficacy still need to be verified through subsequent experiments with a duration of more than six months. And the study has not comprehensively evaluated the systemic toxicity and cytokine storm risks that the vaccine may cause. It is necessary to conduct relevant experiments to further confirm its overall safety. Additionally, this vaccine has limited protective effect against the B/Jilin/02/2022 (Victoria) virus. It is speculated that this may be related to the low antigen match, making it difficult for the immune system to effectively recognize and generate specific immune responses; at the same time, the virus may have acquired immune evasion ability through continuous mutations and unique immune escape mechanisms. The above hypotheses need to be further studied in depth and systematically explored for their potential mechanisms.

In summary, the Ub-Re-N vaccine elicited a robust cellular immune response in normal mice and, irrespective of antibody presence, significantly reduced viral load in mouse tissues following infection. These findings suggest that incorporating ubiquitin sequence with antigen genes can enhance vaccine efficacy, thereby highlighting its potential for broad applications in viral infection prevention and cancer treatment.

5. Conclusion

The Ub-Re-N mRNA vaccine significantly enhances the cellular immune response mediated by CD8+ T cells through the incorporation of ubiquitination modification. This enhancement enables T cells to more accurately and effectively recognize and eliminate infected target cells, thereby efficiently controlling the spread of pathogens within the host and providing broad-spectrum cross-protection against multiple influenza virus subtypes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yaxin Di: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation. Ziliang Wang: Data curation, Validation. Zilin Ren: Formal analysis, Methodology. Haixin Huang: Formal analysis. Songhui Yang: Software. Chenchao Zhang: Investigation. Shibo Liang: Resources. Pengyuan Dong: Resources. Wanbo Tai: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Xinyu Zhuang: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration. Mingyao Tian: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32202820 to X.Z., 82271872 to W.T., 82341046 to W.T.); the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (E24010010, E24010014) to W.T.; Shenzhen Bay Laboratory Startup Fund (no. 21330111 to W.T.); National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFA0920000).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2025.100457.

Contributor Information

Wanbo Tai, Email: taiwb@szbl.ac.cn.

Xinyu Zhuang, Email: xinyuzhuang367@163.com.

Mingyao Tian, Email: klwklw@126.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Auladell M., Jia X., Hensen L., et al. Recalling the future: immunological memory toward unpredictable influenza viruses. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1400. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T., Elbahesh H., Reperant L.A., et al. Influenza vaccines: successes and continuing challenges. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;224(12 Suppl 2):S405–S419. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S.A., Vasi Z., Adhikari R., et al. Ubiquitin proteasome system in immune regulation and therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022;67 doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S.A., Vasi Z., Adhikari R., et al. Ubiquitin proteasome system in immune regulation and therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022;67 doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshra H., Lorenzo G., Rodriguez F., et al. A DNA vaccine encoding ubiquitinated Rift Valley fever virus nucleoprotein provides consistent immunity and protects IFNAR(-/-) mice upon lethal virus challenge. Vaccine. 2011;29(27):4469–4475. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çetin G., Klafack S., Studencka-Turski M., et al. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in immune cells. Biomolecules. 2021;11(1):60. doi: 10.3390/biom11010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira L.M., Morale M.G., Chaves A.A., et al. Expression, polyubiquitination, and therapeutic potential of recombinant E6E7 from HPV16 antigens fused to ubiquitin. Mol. Biotechnol. 2017;59(1):46–56. doi: 10.1007/s12033-016-9990-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada L.D., Schultz-Cherry S. Development of a universal influenza vaccine. J. Immunol. 2019;202(2):392–398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiege J.K., Block K.E., Pierson M.J., et al. Mice with diverse microbial exposure histories as a model for preclinical vaccine testing. Cell Host. Microbe. 2021;29(12) doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.10.001. 1815-1827.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambino F., Jr., Tai W., Voronin D., et al. A vaccine inducing solely cytotoxic T lymphocytes fully prevents Zika virus infection and fetal damage. Cell Rep. 2021;35(6) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Li Y., Song J., et al. Immune responses in wild-type mice against prion proteins induced using a DNA prime-protein boost strategy. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2011;24(5):523–529. doi: 10.3967/0895-3988.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemann E.A., Green R., Turnbull J.B., et al. Interferon-λ modulates dendritic cells to facilitate T cell immunity during infection with influenza A virus. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20(8):1035–1045. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0408-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T., Duan X., Hisaeda H., et al. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells induced by the ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;365(4):758–763. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen J.M., Gerlach T., Elbahesh H., et al. Influenza virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity induced by infection and vaccination. J. Clin. Virol. 2019;119:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Chen ZJ. The role of ubiquitylation in immune defence and pathogen evasion. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;12(1):35–48. doi: 10.1038/nri3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.S., Sun J., Braciale TJ. T cell responses during influenza infection: getting and keeping control. Trends. Immunol. 2011;32(5):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloetzel P.M., Ossendorp F. Proteasome and peptidase function in MHC-class-I-mediated antigen presentation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2004;16(1):76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsakos M., Illing P.T., Nguyen T.H.O., et al. Human CD8+ T cell cross-reactivity across influenza A, B and C viruses. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20(5):613–625. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Gruta N.L., Turner S.J. T cell mediated immunity to influenza: mechanisms of viral control. Trends. Immunol. 2014;35(8):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou J., Liang W., Cao L., et al. Predictive evolutionary modelling for influenza virus by site-based dynamics of mutations. Nat. Commun. 2024;15(1):2546. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46918-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machkovech H.M., Bedford T., Suchard M.A., et al. Positive Selection in CD8+ T-Cell epitopes of influenza virus nucleoprotein revealed by a comparative analysis of human and swine viral lineages. J. Virol. 2015;89(22):11275–11283. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01571-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-López A., Calvo-Pinilla E., Barriales D., et al. CD8 T cell responses to an immunodominant epitope within the nonstructural protein NS1 provide wide immunoprotection against bluetongue virus in IFNAR-/-Mice. J. Virol. 2018;92(16) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00938-18. e00938-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee M.C., Huang W. Evolutionary conservation and positive selection of influenza A nucleoprotein CTL epitopes for universal vaccination. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94(6):2578–2587. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.H.O., Rowntree L.C., Chua B.Y., et al. Defining the balance between optimal immunity and immunopathology in influenza virus infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024;24(10):720–735. doi: 10.1038/s41577-024-01029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Champion JA. Effect of antigen structure in subunit vaccine nanoparticles on humoral immune responses. ACS. Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023;9(3):1296–1306. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c01516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H., Liu B., Wang X., et al. The humoral response and antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022;23(7):1008–1020. doi: 10.1038/s41590-022-01248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehermann B., Nascimbeni M. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5(3):215–229. doi: 10.1038/nri1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez F., Zhang J., Whitton JL. DNA immunization: ubiquitination of a viral protein enhances cytotoxic T-lymphocyte induction and antiviral protection but abrogates antibody induction. J. Virol. 1997;71(11):8497–8503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.11.8497-8503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotsaert M., Cox R.J., Mallett CP. Editorial: Pandemic influenza vaccine approaches: Current status and future directions. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.980956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Madhubala R. Ubiquitin conjugation of open reading frame F DNA vaccine leads to enhanced cell-mediated immune response and induces protection against both antimony-susceptible and -resistant strains of Leishmania donovani. J. Immunol. 2009;183(12):7719–7731. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Zheng J., Zhang X., et al. A T cell-based SARS-CoV-2 spike protein vaccine provides protection without antibodies. JCI. Insight. 2024;9(5) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.155789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Ma H., Wang X., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies to combat influenza virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2024;221 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2023.105785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombetta C.M., Kistner O., Montomoli E., et al. Influenza viruses and vaccines: the role of vaccine effectiveness studies for evaluation of the benefits of influenza vaccines. Vaccines. (Basel) 2022;10(5):714. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang T.K., Lam K.T., Liu Y., et al. Investigation of CD4 and CD8 T cell-mediated protection against influenza A virus in a cohort study. BMC. Med. 2022;20(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02429-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Sandt C.E., Clemens E.B., Grant E.J., et al. Challenging immunodominance of influenza-specific CD8+ T cell responses restricted by the risk-associated HLA-A*68:01 allomorph. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):5579. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13346-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.M., Kang L., Wang XH. Improved cellular immune response elicited by a ubiquitin-fused ESAT-6 DNA vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;53(7):384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T., Zhang C., Xing J., et al. Ferritin-binding and ubiquitination-modified mRNA vaccines induce potent immune responses and protective efficacy against SARS-CoV-2. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024;129 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zheng H., Guo P., et al. Broadly protective CD8+ T cell immunity to highly conserved epitopes elicited by heat shock protein gp96-adjuvanted influenza monovalent split vaccine. J. Virol. 2021;95(12) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00507-21. e00507-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Obata C., Hisaeda H., et al. A novel DNA vaccine based on ubiquitin-proteasome pathway targeting 'self'-antigens expressed in melanoma/melanocyte. Gene Ther. 2005;12(13):1049–1057. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X., Qi Y., Wang M., et al. mRNA vaccines encoding the HA protein of influenza A H1N1 virus delivered by cationic lipid nanoparticles induce protective immune responses in mice. Vaccines. (Basel) 2020;8(1):123. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.