Abstract

Pacemaker myocytes of the sinoatrial (SA) node initiate each heartbeat through coupled voltage and Ca2+ oscillators, but whether ATP supply is regulated on a beat-by-beat schedule in these cells has been unclear. Using genetically encoded sensors targeted to the cytosol and mitochondria, we tracked beat-resolved ATP dynamics in intact mouse SA node and isolated myocytes. Cytosolic ATP rose transiently with each Ca2+ transient and segregated into high- and low-gain phenotypes defined by the Ca2+–ATP coupling slope. Mitochondrial ATP flux adopted two stereotyped waveforms—Mode-1 “gains” and Mode-2 “dips.” Within Mode-1 cells, ATP gains mirrored the cytosolic high/low-gain dichotomy; Mode-2 dips scaled linearly with Ca2+ load and predominated in slower-firing cells. In the intact node, high-gain/Mode-1 phenotypes localized to superior regions and low-gain/Mode-2 to inferior regions, paralleling gradients in rate, mitochondrial volume, and capillary density. Pharmacology placed the Ca2+ clock upstream of ATP production: the HCN channel blocker ivabradine slowed the ATP cycle without changing amplitude, whereas the SERCA pump inhibitor thapsigargin or the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP abolished transients. Mode-2 recovery kinetics indicate slower ATP replenishment that would favor low-frequency, fluctuation-rich firing in a subset of cells. Together, these findings reveal beat-locked metabolic microdomains in which the Ca2+ clock times oxidative phosphorylation under a local O2 ceiling, unifying vascular architecture, mitochondrial organization, and Ca2+ signaling to coordinate energy supply with excitability. This energetic hierarchy helps explain why some SA node myocytes are more likely to set rate whereas others may widen bandwidth.

Keywords: Bioenergetics, stochastic resonance, entrainment, mitochondria, oxidative phosphorylation, pacemaking, excitation-contraction coupling

Summary

Beat-locked cytosolic and mitochondrial ATP transients in SA-node myocytes sort into high-gain, low-gain, or consumption-dominant modes aligned with superior–inferior vascular–mitochondrial gradients. This energetic hierarchy lets high-gain cells set fast rates while low-gain/dip cells stabilize slow rhythms—broadening operating range but capping maximal bandwidth.

Introduction

The heartbeat originates in the sinoatrial (SA) node, a crescent-shaped pacemaker region embedded at the junction of the superior vena cava and right atrium. Within the node, clusters of pacemaker myocytes fire spontaneous action potentials that propagate through gap junctions to neighboring SA node myocytes and, ultimately, the surrounding myocardium.

Pacemaking emerges from the concerted operation of a “membrane clock,” composed of voltage-gated ion channels, including hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (HCN2/HCN4) and Ca2+ channels (CaV3.1, CaV1.3 and CaV1.2) (Brown and Difrancesco, 1980; DiFrancesco, 1986; Huser et al., 2000; Mangoni et al., 2006), and a “Ca2+ clock,” timed by stochastic, diastolic Ca2+ sparks from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) that activate inward Na+/Ca2+-exchanger current (Bogdanov et al., 2001). These coupled oscillators depolarize the membrane to threshold, trigger a cell-wide, global intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) transient and, after repolarization by K+ currents, reset to begin the next diastolic depolarization.

A defining feature of the SA node is its functional and anatomical heterogeneity (Boyett et al., 2000). Superior regions tend to fire faster and are richer in mitochondria and capillaries, whereas inferior regions fire more slowly and are more sparsely vascularized. This spatial organization creates subpopulations with distinct intrinsic rates, metabolic throughput, and coupling, suggesting that network rhythm could arise through at least two non-exclusive mechanisms: classical entrainment (Jalife, 1984; Anumonwo et al., 1991)—where electrotonic coupling pulls disparate oscillators toward a common period—and stochastic resonance—where variability from a noisier subpopulation can enhance sensitivity and bandwidth (Clancy and Santana, 2020; Grainger et al., 2021; Guarina et al., 2022).

Each beat carries a steep energetic cost. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis is required to maintain Na+ and K+ gradients via the Na+/K+ ATPase, refill the SR with Ca2+ through the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) pump, support cross-bridge cycling, and fuel the continual adenylate cyclase-mediated production of cAMP that tunes both clock components (Yaniv et al., 2013). Even under basal conditions, isolated mouse SA node myocytes consume more O2 than ventricular myocytes paced at 3 Hz, and their ATP turnover rises further during sympathetic stimulation. About ~95% of this ATP is supplied by mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and the remaining ~5% by glycolysis (Wisneski et al., 1990; Saddik and Lopaschuk, 1991; Zhou and Tian, 2018; Lopaschuk et al., 2021)

Classic work has established coupling between Ca2+ handling and ATP production, showing that Ca2+ entering the mitochondrial matrix via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) activates three Ca2+-sensitive dehydrogenases—pyruvate, isocitrate, and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase—boosting NADH production and driving proton flux through the ATP5A-containing F1Fo-ATP synthase (Denton et al., 1980; Denton and McCormack, 1990; McCormack et al., 1990; Kirichok et al., 2004; Garbincius and Elrod, 2022). In this process, mitochondrial efficiency is shaped not only by enzymatic capacity but also by organelle architecture and proximity to SR Ca2+-release sites. The tethering protein mitofusin-2 (Mfn2), located on the outer mitochondrial membrane, mediates physical and functional coupling between mitochondria and the junctional SR, facilitating rapid Ca2+ transfer and enhancing oxidative phosphorylation (Chen et al., 2012; Dorn et al., 2015). Mitochondrial ATP production is supplemented by glycolysis and is further supported by creatine and adenylate kinase reactions, which draw on phosphocreatine and ADP pools to regenerate ATP. These pathways act in concert to maintain ATP supply across varying workloads.

To match the relentless demand for ATP by SA node myocytes, the SA node artery—most commonly a branch of the right coronary artery—fans into an elaborate capillary network that perfuses the node during diastole when extravascular compression is lowest. High-resolution, cleared-tissue reconstructions show that capillary density is greatest and myocyte-to-vessel distance shortest in the superior SA node, whereas inferior regions are more sparsely vascularized (Grainger et al., 2021; Manning et al., 2025). These structural gradients correlate with intrinsic firing rate, suggesting that local energetic support sculpts pacemaker hierarchy. Yet direct links between microvascular architecture, subcellular energetics, and pacemaking behavior have remained elusive.

Using genetically encoded fluorescent ATP sensors, we previously showed that, under physiological workload, cytosolic ATP rises and falls with every [Ca2+]ᵢ transient in ventricular myocytes (Rhana et al., 2024; Rhana et al., 2025). This raised two questions for the SA node: do spontaneously firing myocytes exhibit comparable beat-locked ATP dynamics, and do these dynamics differ between superior and inferior domains in ways that would be expected to bias rate setting versus bandwidth?

To address these questions, we combined beat-resolved ATP imaging in the intact node and in isolated myocytes to: (i) define two mitochondrial ATP modes time-locked to Ca2+ transients; (ii) identify matched high- and low-gain cytosolic ATP phenotypes; (iii) map these energetic phenotypes onto regional firing rate, mitochondrial volume, and capillary density; and (iv) demonstrate that the Ca2+ clock—via SR-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer—acts as a master regulator that times oxidative ATP production to demand. This hierarchy allocates pacemaking roles across the node and extends the emerging “paycheck-to-paycheck” model from ventricular myocytes (Rhana et al., 2024; Rhana et al., 2025) to the SA node. Here, “paycheck-to-paycheck” denotes beat-locked ATP synthesis/use bounded by a local O2 ceiling—capillaries set the ceiling, mitochondria the bandwidth, and Ca2+ the timing—linking vascular architecture and mitochondrial organization to excitability and clarifying why some cells set rate while others widen bandwidth.

Methods

Animals.

Male wild-type C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory) aged 8–12 weeks were used for all experiments in this study. Mice were euthanized with a single, intraperitoneal administration of a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (250 mg/kg). All procedures were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis.

AAV-mediated delivery of ATP biosensors.

Real-time visualization of intracellular ATP dynamics was enabled by systemically injecting mice with adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) vectors encoding either the cytosolic ATP sensor iATPSnFR1.0 (cyto-iATP) (Lobas et al., 2019) or the mitochondria-targeted variant iATPSnFR2.0 (mito-iATP) (Marvin et al., 2024) at a titer of 4 × 1012 viral genomes per milliliter (vg/mL). Under isoflurane anesthesia (5% induction, 2% maintenance), 100 μL of AAV9 vector solution was delivered via retro-orbital injection using a microsyringe.

Multi-photon imaging of [ATP]i and [ATP]mito.

Following confirmation of deep anesthesia, beating hearts were excised from animals expressing AAV9 constructs and transferred to warmed (37°C) Tyrode III solution consisting of 140 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES, and 5.5 mM glucose (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH). The SA node was dissected from the beating heart, pinned flat to expose the full node, and incubated in 10 μM blebbistatin (Sigma Aldrich) for 1 hour at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cyto-iATP and mito-iATP signals in intact SA nodes perfused ex vivo with room temperature Tyrode III supplemented with blebbistatin (10 μM) were imaged in line-scan mode using an Olympus multi-photon excitation FV3000-MPE upright microscope equipped with an Olympus XL Plan N 25X lens (NA = 1.05). For experiments employing ivabradine (30 μM; Tocris) or thapsigargin (1 μM; Tocris), agents were added directly to the perfusate, and preps were allowed to incubate for 30 minutes before line scans were recorded. During analysis, background was subtracted from all line-scan images, and fluorescence signals were expressed as F/F0, where F is the fluorescence intensity at a given time point and F0 is the mean baseline fluorescence.

Whole-mount immunolabeling of SA node tissue.

SA node immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously in detail (Grainger et al., 2021; Manning et al., 2025). Briefly, SA node tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes. After fixation, the tissue was washed three times for 5 minutes each and then transferred to a 15-mL tube filled with PBS and washed for 12 hours at low speed on a tube rotator. Tissues were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (25%, 50%, 75%, 95%, 100%), cleared in 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in ethanol for 2 hours, and bleached overnight (12 hours) in 6% hydrogen peroxide prepared in absolute ethanol. Samples were then rehydrated by reversing the ethanol gradient and washed in PBS (3 × 5 minutes). Cells were permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS (3 × 10 minutes) and then blocked by incubating with 5% normal donkey serum in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 2 hours at room temperature.

For immunolabeling, SA nodes were incubated at 4°C for 48 hours with goat anti-mouse CD31 primary antibody (AF3628; R&D Systems), diluted 1:50 in PBS. After three PBS washes (10 minutes each), tissues were incubated for 4 hours at room temperature in the dark with donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 568 (1:1000, A11057; Thermo Fisher Scientific) or anti-GFP Alexa Fluor 647 (1:1000, A32985; Thermo Fisher Scientific) secondary antibodies. Following final washes in PBS (3 × 10 minutes), tissues were incubated in a 1:4 solution of DMSO: PBS for 2 hours, then mounted in Aqua-Mount (Thermo Scientific), cover-slipped, and sealed for imaging.

Isolation of SA node myocytes.

The full SA node was dissected from the beating heart and exposed by pinning flat. The procedure for isolating single SA node myocytes was adapted from Fenske et al. (2020) and Grainger et al. (2021), with modifications. The node was incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes in low-Ca2+ Tyrode solution consisting of 140 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl₂, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 5.0 mM HEPES, 5.5 glucose, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, and 50.0 mM taurine (pH 6.9, adjusted with NaOH).

Enzymatic digestion was performed for 25 minutes at 37°C with periodic (every 5 minutes) gentle agitation using the same Ca2+-free Tyrode buffer (pH 6.9) supplemented with 18.87 U/mL elastase, 1.79 U/mL protease, 0.54 U/mL collagenase B, and 100 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA). Following enzymatic treatment, tissues were rinsed twice in fresh low-Ca2+ Tyrode and twice in ice-cold Kraft-Brühe (KB) solution consisting of 100.0 mM L-glutamic acid K+ salt, 5.0 mM HEPES, 20.0 mM glucose, 25.0 mM KCl, 10.0 mM L-aspartic acid K+ salt, 2.0 mM MgSO4, 10 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM taurine, 5.0 mM creatine, 10.0 mM EGTA, and 1.0 mg/mL BSA (pH 7.4, adjusted with KOH). Samples were stored at 4°C in 350 μL KB solution for 2–3 hours, then warmed to 37°C for 10 minutes prior to gentle mechanical dissociation using a fire-polished glass pipette.

Ca2+ was reintroduced in two steps performed at room temperature. First, 10 μL of Na+/Ca2+ solution containing 10.0 mM NaCl and 1.8 mM CaCl2 was added for 5 minutes, then 23 μL of Na+/Ca2+ solution was added and incubated for 5 minutes. A BSA-containing solution consisting of 140.0 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.0 MgCl₂, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5.0 mM HEPES, 5.5 mM glucose, and 1 mg/mL BSA was added at volumes of 55 μL, 175 μL and 612 μL in 4-minute steps.

Confocal imaging of [Ca2+]i, [ATP]i, [ATP]mito, and mitochondria.

Diastolic and systolic [Ca2+]i and cyto-iATP or mito-iATP signals from dissociated SA node myocytes were simultaneously recorded using an inverted Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan) operating in 2D or line-scan mode. Cytosolic Ca2+ was monitored by first loading SA node myocytes expressing cyto-iATP or mito-iATP with 10 μM Rhod-3-AM (Thermo Fisher, USA), as described previously (Rhana et al., 2024). After loading with Rhod-3, a drop of the cell suspension was transferred to a temperature-controlled (37°C) perfusion chamber on a microscope stage and cells were allowed to settle onto the coverslip for 5 minutes. Fluorescent indicators were excited with solid-state lasers emitting at 488 nm (cyto-iATP and mito-iATP) or 561 nm (Rhod-3) through a 60× oil-immersion lens (PlanApo; NA = 1.40). During analysis, background was subtracted from all confocal images, and fluorescence signals were expressed as F/F0, where F is the fluorescence intensity at a given time point and F0 is the mean baseline fluorescence. Ca2+, cyto-iATP, and mito-iATP signals were automatically detected and analyzed using ImageJ and SanPy software (Guarina et al., 2024) or custom Python code.

In a subset of experiments, we recorded Ca2+ release events from SA node myocytes loaded with Fluo-4-AM. These signals were detected and analyzed using an ML-based Ca2+ signal detection and analysis pipeline as previously described (Garrud et al., 2024). In brief, a F/F0 channel was calculated from the raw 488 channel by dividing each frame by a five-frame moving average (without background subtraction) and rescaled to eliminate fractional pixel values. Both channels (488 and F/F0) were used to simultaneously train a ML model ground truth by manually annotating every pixel of at least 10 Ca2+ signals from 10 representative experiments (Arivis Vision4D, Zeiss). The trained ML model was run on all experiments and Ca2+ signals with mean F/F0 intensity of less that 1.025 of baseline or total area of less than 5 microns were excluded from further analysis. ML-annotated Ca2+ signal properties (size, location (x, y, t), duration, and signal mass (sum of each Ca2+ signal F/F0 over its duration) were exported for summary and statistical analysis.

Quantification of mitochondrial volume.

Mitochondrial volume was quantified by analyzing super-resolution radial fluctuation (SRRF)-acquired 3D image stacks of MitoTracker-labeled SA node myocytes with Imaris 10 software (Oxford Instruments, UK). Myocytes were isolated from anatomically defined superior and inferior regions of the SA node. Mitochondria were segmented using the Surfaces tool based on MitoTracker Far Red fluorescence intensity, applying a consistent threshold across all samples. Total mitochondrial volume was computed for each individual cell, allowing for regional comparisons between superior and inferior SA node myocyte populations.

Super-resolution imaging of SA node myocytes.

Freshly isolated SA node myocytes expressing cyto-iATP or mito-iATP were incubated with 250 nM MitoTracker Deep Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 minutes at 37°C. SRRF imaging was performed using a Dragonfly 200 spinning-disk confocal system (Andor Technology, UK) equipped with an Andor iXon EMCCD camera. This system was coupled to an inverted Leica DMi microscope equipped with a 60x oil-immersion objective with a numerical aperture (NA) of 1.4. Images were acquired using Fusion software (Andor). Colocalization of ATP sensors with Rhod-3 and MitoTracker was evaluated using the Coloc module in Imaris 10 (Oxford Instruments, UK).

Statistics.

Data normality was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Parametric data are reported as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and compared using a one or two-tailed Student’s t-tests (two groups) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (≥3 groups). One-tailed t-tests were used when directional hypotheses were specified a priori based on established regional differences in SA node structure and function. Non-parametric data are summarized as medians (interquartile range) and analyzed with the Mann–Whitney test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and is denoted in the figures as P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.001 (***), and P < 0.0001 (****).

Distributions that were statistically multimodal (i.e., ATP signal mass, Ca2+ signal mass, and mitochondrial volume fraction) were modelled with finite Gaussian-mixture models. The optimal number of components was selected by minimizing the Bayesian information criterion and confirmed by the gap statistic, silhouette score, and Hartigan’s dip test for unimodality (P < 0.001 for departure from a single mode).

Online supplemental material.

Supplemental Figures S1–5 present the kinetics of ATP and Ca2+ transients at the whole-node and single-cell levels. Figure S1 shows the kinetics of whole-node cyto-iATP transients, and Figure S2 shows the corresponding whole-node mito-iATP transients. Figures S3–S5 focus on SA node myocytes, with Figure S3 depicting Ca2+ and cyto-iATP transients, Figure S4 showing Ca2+ and Mode 1 mito-iATP transients, and Figure S5 showing Ca2+ and Mode 2 mito-iATP transients.

Results

Targeted expression of ATP sensors in mitochondrial and cytosolic compartments of SA node myocytes

To enable compartment-resolved experiments, we expressed genetically encoded ATP reporters in the cytosol and mitochondrial matrix of mouse SA node myocytes. The cytosolic reporter was iATPSnFR1 (cyto-iATP) (Lobas et al., 2019). The mitochondrial reporter (mito-iATP) was derived from iATPSnFR2 bearing the A95A/A119L low-affinity (apparent Kd = 0.5 mM) variant and targeted to the matrix by four tandem COX8 leader sequences (Marvin et al., 2024).

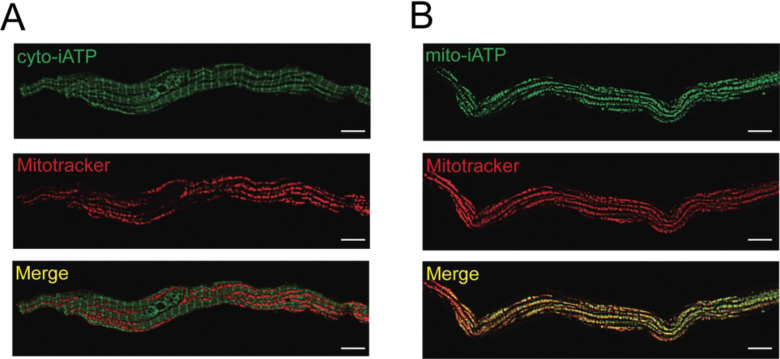

Following adenoviral transduction and enzymatic dissociation of mouse SA node tissue, we confirmed probe localization in isolated SA node myocytes using SRRF super-resolution microscopy (Figure 1). Cytosolic-iATPSnFR1 fluorescence was diffusely distributed throughout the cytoplasm and excluded from mitochondria, as indicated by a low Manders’ coefficient of 0.26 ± 0.04 relative to the MitoTracker Far Red signal (Figure 1A). In contrast, mito-iATPSnFR2 displayed a punctate fluorescence pattern characteristic of mitochondrial structures. Co-staining with MitoTracker Far Red demonstrated strong spatial overlap, with a mean Manders’ correlation coefficient of 0.85 ± 0.03, consistent with robust mitochondrial targeting (Figure 1B). These results validate the selective subcellular targeting of cyto- and mito-iATP sensors and establish a platform for high-resolution, compartment-specific imaging of ATP dynamics in SA node pacemaker cells.

Figure 1: Subcellular targeting of genetically encoded ATP sensors in mouse SA node myocytes.

(A) Live-cell, super-resolution radial fluctuations (SRRF) confocal images of sinoatrial node myocytes expressing cyto-iATP (green), Mitotracker Deep Red (red), and the merged image (yellow) (0.26 ± 0.04; N = 3 mice, n = 16 myocytes) (B) Live-cell, SRRF confocal images of SA node myocytes expressing mito-iATP (green), Mitotracker Deep Red (red), and the merged image (yellow) (0.85 ± 0.03; N = 3 mice, n = 30 myocytes). White scale bars are 5 μm long.

Superior and inferior regions of the SA node exhibit distinct ATP dynamics

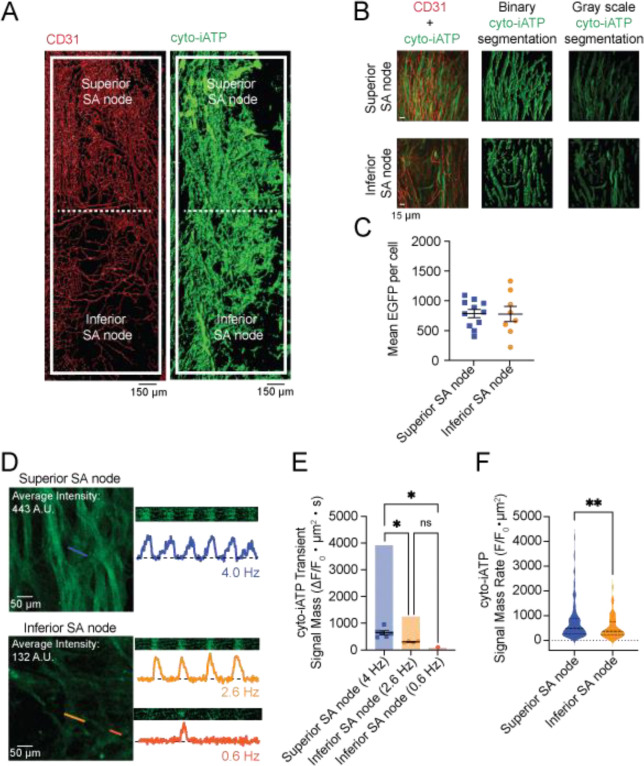

To map regional ATP dynamics, we first surveyed cyto-iATP fluorescence throughout the intact mouse SA node (Figure 2). To provide vascular landmarks and demarcate SA node borders, we co-stained whole mounts for the endothelial marker CD31. In agreement with Grainger et al. (2021) and Manning et al. (2025), vessel density varied markedly along the node and was highest in the superior region (Figure 2A). Cyto-iATP signals were present along the entire node. Automated segmentation revealed more cyto-iATP-positive myocytes in the superior than inferior region, mirroring the previously reported SA node myocyte density gradient (Grainger et al., 2021; Manning et al., 2025); however, mean iATP fluorescence per cell did not differ between superior (785.4 ± 69.1 AU) and inferior (779.3 ± 129.1 AU) regions (P = 0.48; Figure 2B, C).

Figure 2: Superior SA node myocytes exhibit higher steady-state cytoiATP and greater beat-to-beat ATP flux than inferior regions.

(A) 3-D segmented maximum-intensity projection of whole-mount SA node immunolabeled for CD31+ blood vessels (red, left), EGFP+ myocytes (green, right). (B) Merged exemplar maximum intensity projection of CD31+ and EGFP+ myocytes from the superior (top) and inferior (bottom) SA node. EGFP+ cells were segmented (middle) to create a mask of the raw signal (right). White scale bars, 15 μm. (C) Mean cyto-iATP-associated fluorescence per cell from the superior and inferior SA node (Superior, N = 3 mice, n = 11 cells; Inferior, N = 3 mice, n = 8 cells). (D) Live imaging of a region of the superior (top) and inferior (bottom) SA node expressing the cyto-iATP sensor. The line scan and normalized F/F0 traces are shown to the right. (E) Scatter plot of individual cyto-iATP signal mass (F/F0 ・μm2) from traces in (D). Bars indicate the summed signal masses within each region (N = 1, n = 6, 4 and 1 transient for superior 4.0 Hz, inferior 2.6 Hz, and inferior 0.6 Hz traces, respectively; p < 0.05). (F) Violin plots of cyto-iATP signal mass rate (Superior, N = 4 mice, n = 117 traces; Inferior, N = 4 mice, n = 60 traces; p = 0.0075).

We next imaged cyto-iATP ex vivo in spontaneously firing (i.e., sinus rhythm), intact SA nodes using multiphoton microscopy while suppressing contractile motion with blebbistatin (10 μM). Multiphoton optical sections of cyto-iATP fluorescence taken from superior and inferior regions of a representative living SA node revealed consistently higher average fluorescence in the superior domain (Figure 2D). Because sensor expression per cell is equivalent in the two regions (Figure 2B, C), the elevated signal likely reflects a genuine increase in steady-state cytosolic ATP concentration in the superior SA node.

Line-scan multiphoton imaging of cyto-iATP revealed large, rhythmic ATP transients in the superior SA node that tracked the local firing rate (~4 Hz; Figure 2D, top). Inferior regions were more heterogeneous; some myocytes fired more slowly (~2.6 Hz), whereas others were nearly quiescent (~0.6 Hz; Figure 2D, middle and bottom). Although action potentials were not recorded in these experiments, the observed frequencies closely match those measured electrically in superior (4 Hz) and inferior (0.6 Hz) myocytes (Grainger et al., 2021), implying that the cyto-iATP oscillations reflect intrinsic pacemaker activity.

A kinetic analysis showed that cyto-iATP transients were faster in the superior than inferior region of the SA node (Figure S1), with mean time-to-peak of 67.7 ± 0.9 ms and 73.0 ± 2.6 ms, respectively (P = 0.03). Decay phases of superior and inferior cyto-iATP transients were well described by single-exponential fits, with corresponding time constants (τ) of 42.2 ± 1.3 ms and 50.9 ± 2.7 ms (P = 0.0024). The overall duration of superior cyto-iATP transients was 152.1 ± 2.6 ms, significantly shorter (P = 0.0005) than that of the inferior region (174.7 ± 6.1 ms).

We quantified energetic output by calculating the signal mass of each cyto-iATP transient, defined as the time- and area-integrated change in fluorescence (ΔF/F0·μm2·s). As shown in Figure 2E, individual transients carried more mass in superior cells (652.8 ± 68.52 ΔF/F0·μm2·s) than in inferior cells (312.8 ± 18.24 and 117.7 ± 0.08 ΔF/F0·μm2·s in cells firing 2.6 and 0.6 Hz, respectively). When all events in these regions were combined, the total cyto-iATP signal mass over the entire recording period (4.2 seconds for both regions) was markedly greater in the superior SA node (Figure 2E). Accordingly, compiled data from four nodes revealed that the superior region generated a higher signal mass rate (i.e., total signal mass per trace ÷ recording time), with a median of 484.8 ΔF/F0·μm2 (interquartile range, 268.5–879.1 ΔF/F0·μm2), compared to the inferior region median of 364.5 ΔF/F0·μm2 (interquartile range, 225.2–759.4 ΔF/F0·μm2) (Figure 2F; P = 0.0075). Thus, myocytes in the superior SA node sustain a higher beat-to-beat energetic throughput than those in the inferior node.

Pharmacological dissection of membrane and Ca2+ clock contributions to cytosolic ATP dynamics

We next asked how the two intrinsic pacemakers—membrane clock and Ca2+ clock—shape energetic demand in the SA node (Figure 3). To this end, we imaged nodes expressing cyto-iATP in sinus rhythm before and after inhibiting HCN channels by application of the blocker ivabradine or eliminating SR Ca2+ release with the SERCA pump inhibitor thapsigargin (Figure 3A). Under basal conditions, superior SA node regions fired rhythmic cyto-iATP transients at 3.31 ± 0.07 Hz (N = 4 SA nodes); inferior cells fired more slowly at 2.57 ± 0.07 Hz (N = 4 SA nodes; P < 0.0001), but with similar amplitudes (superior = 1.18 ± 0.01 F/F0; inferior = 1.21 ± 0.02 F/F0; P = 0.28).

Figure 3: Distinct energetic roles of the membrane and Ca2+ clocks uncovered by ivabradine and thapsigargin.

(A) Normalized cyto-iATP line scan traces from superior (top) and inferior (bottom) SA node under control conditions (left) and after exposure to 30 μM ivabradine (middle) and 1 μM thapsigargin (right). Peak cyto-iATP amplitudes (B) and transient frequency (C) under control, ivabradine and thapsigargin conditions in superior and inferior regions of the SA node (Superior, N = 4 mice, n = 38 traces; Inferior, N = 4 mice, n = 25 traces; p<0.0001).

Ivabradine (30 μM) lengthened the cycle, decreasing frequency from 3.31 ± 0.07 Hz to 2.12 ± 0.04 Hz in superior cells and from 2.57 ± 0.07 Hz to 1.8 ± 0.06 Hz in inferior cells (P < 0.0001), but did not alter the transient peak (F/F0: 1.15 ± 0.01 and 1.17 ± 0.01 in superior and inferior SA nodes, respectively; P = 0.5) (Figure 3B, C). Thus, membrane clock inhibition curtailed ATP demand chiefly by lowering beat rate. In contrast, blocking SERCA with thapsigargin (1 μM) abolished spontaneous firing, collapsing cyto-iATP transients to baseline and preventing recovering during the 10-minute recording (Figure 3B, C). The complete loss of ATP pulses despite an intact membrane clock indicates that SR Ca2+ cycling is essential not only for excitability but also for beat-to-beat ATP generation.

Taken together, these manipulations show that chronotropic control (membrane clock) and SR Ca2+ re-uptake (Ca2+ clock) make separable, complementary contributions to cellular ATP turnover. The high metabolic output characteristic of the superior pacemaker zone is critically dependent on continuous SERCA activity, underscoring the role of the Ca2+ clock as a master regulator of metabolic supply rather than a passive follower of electrical activity.

Ca2+ transient-locked mitochondrial ATP transients are stronger in superior SA node myocytes

To test whether cyto-iATP oscillations arise from beat-locked changes in mitochondrial ATP, we recorded line-scan images across an intact, mito-iATP–expressing SA node (Figure 4A, B). Spontaneous, rhythmic mitochondrial signals were detected in both superior and inferior regions of the node, appearing as two stereotyped waveforms, designated Mode 1 and Mode 2. Mode 1 events exhibited a rapid rise after each beat followed by an exponential decay, whereas Mode 2 events showed a transient dip before recovering, presumably as new ATP was synthesized.

Figure 4: Oxidative phosphorylation drives robust beat-locked mitoATP signals in SA node myocytes.

Representative line scans and normalized traces of mito-ATP signals of Mode 1 (top) and Mode 2 (bottom) sites in the superior (A) and inferior (B) SA node region under control conditions (left) and exposed to 1 μM FCCP (right). (C) Violin plots of Mode 1 mito-iATP signal mass rate (Superior N = 4 mice, n = 63 traces; Inferior N = 4 mice, n = 37 traces; p = 0.0004). Peak mito-iATP Mode 1 amplitude (D) and transient frequency (E) under control and FCCP conditions in superior and inferior regions of the SA node (Superior N = 4 mice, n = 74 traces; Inferior N = 4 mice, n = 35 traces; p<0.0001). (F) Violin plots of Mode 2 mito-iATP signal mass rate (Superior N = 4 mice, n = 12 traces; Inferior N = 4 mice, n = 5 traces; p = 0.0393) (G). Peak mito-iATP Mode 2 amplitude (G) and transient frequency (H) under control and FCCP conditions in superior and inferior regions of the SA node (Superior N = 4 mice, n = 7 traces; Inferior N = 4 mice, n = 6 traces; p<0.0001). White scale bars, 5 μm.

We performed a detailed kinetic analysis of mito-iATP events in the intact SA node (Figure S2). For Mode-1 “gain” events, rise and decay kinetics were statistically indistinguishable in superior and inferior SA nodes; time-to-peak was 70.0 ± 0.9 ms in the superior region and 71.3 ± 0.6 ms in the inferior region, followed by mono-exponential decay, with a τ of 41.1 ± 1.8 ms in the superior region and 42.5 ± 3.0 ms in the inferior region (Figure S2A-D). Mode-2 “dip” events reached their nadir in 138.1 ± 5.0 ms in the superior node and more rapidly (109.6 ± 10.0 ms) in the inferior node (P = 0.02); recovery proceeded with similar τ values of 87.2 ± 9.3 ms in the superior region and 71.1 ± 5.3 ms in the inferior region (Figure S2F-J). The full duration of Mode 1 mito-iATP transients in the superior region were 152.3 ± 3.5 ms, similar to that in the inferior region (156.3 ± 5.7 ms). Mode 2 mito-iATP dips were faster in the inferior region (251.8 ± 9.8 ms) than in the superior region (312.5 ± 19.5 ms; P = 0.0096). Given that the recovery phase of Mode 2 events reflects oxidative-phosphorylation capacity, the observed ~250–312 ms recovery window suggests that dip-dominant cells can sustain firing only up to ~3.2–4.0 Hz, as faster pacing would limit ATP replenishment before the next beat.

The mito-iATP signal mass rate (i.e., total signal mass per trace ÷ recording time) of Mode 1 sites was significantly larger in superior myocytes (median, 557.0 ΔF/F0·μm2; interquartile range, 318.6–1040.0 ΔF/F0·μm2) than inferior myocytes (median, 339.8 ΔF/F0·μm2; interquartile range, 245.5–537.7), indicating greater mitochondrial ATP production in the leading pacemaker zone (Figure 4C; P = 0.0004). Mode 1 mito-iATP amplitudes in the superior region (1.26 ± 0.02 F/F0) were similar to those in the inferior region (1.25 ± 0.01 F/F0) (Figure 4D; P = 0.99). The frequency of Mode 1 mito-iATP transients in the superior region ranged from 4.5 to 1.2 Hz, with a mean frequency of 3.21 ± 0.07 Hz. In the inferior node, mito-iATP transient frequency never exceeded 3.3 Hz, with a mean frequency of 2.49 ± 0.07 Hz (Figure 4E; P < 0.0001).

The integrated ATP deficit rate (i.e., negative signal mass) during Mode 2 events was significantly larger in superior myocytes (median, −689.6 ΔF/F0·μm2; interquartile range, −1117.0 to −458.8 ΔF/F0·μm2) than in inferior myocytes (median, −446.3 ΔF/F0·μm2; interquartile range, −633.6 to −317.7 ΔF/F0·μm2) (Figure 4F; P = 0.04), indicating greater mitochondrial ATP consumption in the leading pacemaker zone. Dip amplitudes were virtually identical between regions (0.77 ± 0.02 vs. 0.78 ± 0.02 F/F0; Figure 4G; P = 0.97). Mode-2 event frequency ranged from 2.6 to 2.8 Hz in the superior node (mean, 2.78 ± 0.04 Hz) to 2.1 to 2.8 Hz in the inferior node (mean, 2.57 ± 0.10 Hz; Figure 4H; P = 0.053), which is well below the ~3.2–4 Hz ceiling predicted from the 250–312 ms recovery window.

Across 50 beats (with contraction arrested), integrated Mode 2 dips averaged 0.24 ± 0.02, or ~1.7-fold larger than Mode 1 gains (0.25 ± 0.11). Thus, in Mode 2 microdomains, ATP is drawn out of the matrix faster than it is produced during the action potential, generating a brief deficit that is repaid more slowly during diastole. Because Mode 1 (gain) and Mode 2 (dip) regions are spatially distinct, this imbalance implies that high-demand microdomains (Mode 2) temporarily outstrip the surplus generated in high-production zones (Mode 1). Matrix diffusion and a diastolic repayment window therefore appear essential for beat-to-beat energetic homeostasis in pacemaker cells.

Brief exposure to FCCP (1 μM), an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation, abolished both waveform types in every cell examined (Figure 4A–H). Thus, beat-locked mitochondrial ATP transients depend on an intact proton-motive force and, therefore, on ongoing oxidative phosphorylation. The near-complete suppression of Mode-1 signals—and the greater reduction in Mode-2 amplitude—in superior myocytes underscores their heavier reliance on oxidative phosphorylation and highlights the tight electro-metabolic coupling that supports the dominant pacemaker site. By contrast, inferior mitochondria make only a modest contribution to the cytosolic ATP pool under basal conditions.

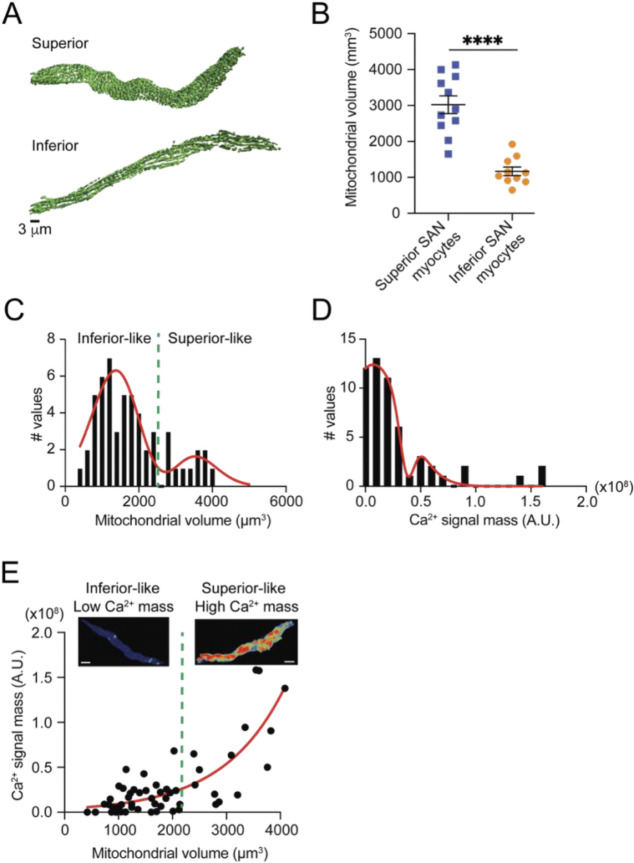

Regional differences in mitochondrial volume define distinct SA node myocyte phenotypes

Three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions of isolated, region-identified SA node myocytes showed that mitochondrial mass itself varies across the node. Superior cells possessed a visibly denser reticulum than inferior cells (Figure 5A), and volumetric rendering revealed more than a 2-fold increase in total mitochondrial volume in the superior population (3014 ± 245 mm3) compared with the inferior population (1161 ± 121 mm3) (P < 0.0001; Figure 5B). Combined with the current ATP-imaging results and the higher firing rates previously documented for superior versus inferior myocytes (Grainger et al., 2021), these data indicate that superior pacemaker cells pair a larger mitochondrial network with greater beat-locked ATP output and faster excitability, whereas inferior cells couple a smaller organelle pool to lower metabolic and electrical activity. Thus, regional differences in mitochondrial volume constitute a structural determinant of the metabolic and electrophysiological phenotypes that coexist within the SA node.

Figure 5. Regional mitochondrial abundance dictates Ca2+-signal mass in SA node myocytes.

(A) 3-D Surface renderings of the mitochondrial reticulum (Mitotracker Green) in representative myocytes isolated from the superior and inferior regions of the mouse SA node. (B) Total mitochondrial volume per myocyte (Superior N = 3 mice, n = 11 myocytes; Inferior N = 3 mice, n = 10 myocytes; p<0.0001). (C) Pooled frequency distribution of mitochondrial volume. A fit to the sum of two Gaussian functions (red line) resolves two populations; the green dashed line (≈ 2.2 × 103 μm3) is the intersection used to classify “inferior-like” (left of line) and “superior-like” (right of line) myocytes. (D) Frequency distribution of the integrated Ca2+-signal mass from the same myocytes. The red curve represents a fit to the sum of two Gaussian functions. (E) Scatter plot relating mitochondrial volume to Ca2+-signal mass for every myocyte (black circles). Solid red line, exponential fit (R2 = 0.73). Data falling to the left and right of the dashed threshold correspond to inferior-like (low Ca2+ mass) and superior-like (high Ca2+ mass) phenotypes, respectively; maximum intensity projection images (insets) illustrate Ca2+ dynamics transients for each group. White scale bars, 5 μm.

Differences in mitochondrial volume sustain varied SA node Ca2+-signaling loads

To determine whether mitochondrial size constrains the Ca2+ burden of individual pacemaker cells, we analyzed the full pool of SA node myocytes instead of pre-sorting them by anatomical origin. Pooling was justified for three reasons: (i) 3D reconstructions revealed a clearly bimodal distribution of mitochondrial volumes—small-volume cells came almost exclusively from the inferior node and large-volume cells from the superior node—so treating the tissue as two rigid classes would have narrowed the quantitative range available for correlation analysis and reduced power. (ii) Superior myocytes fire Ca2+ transients at ~4 Hz versus ~1 Hz in inferior cells Grainger et al. (2021); because transient amplitudes are comparable, frequency alone accounts for their greater total Ca2+ flux. In our dataset, every Ca2+ record was normalized to its own firing rate, removing this regional bias and allowing us to test whether bigger mitochondrial networks support larger beat-normalized Ca2+ loads across the entire spectrum of phenotypes. (iii) The limited yield of viable, dye-loaded cells obtained from finely dissected sub-regions—and the need to collect both 3D mitochondrial stacks and high-speed Ca2+ movies—would have left separate regional datasets under-powered. Pooling therefore maximized sample size and provided an unbiased, statistically robust test of structure–function coupling.

Three-dimensional mitochondrial stacks, obtained by SRRF imaging of the mitochondrial reticulum, and movies of cytosolic Ca2+ signals were generated from acutely dissociated SA node myocytes loaded with MitoTracker Far Red and Fluo-4 AM. Mitochondrial-volume histograms displayed two well-separated peaks; a double-Gaussian fit yielded a threshold of ~2,200 μm3 that segregated “inferior-like” (low-volume) from “superior-like” (high-volume) cells (Figure 5C). An analogous bimodal pattern was observed for Ca2+ signal mass (Figure 5D). Across the pooled population, mitochondrial volume was a strong predictor of Ca2+-handling load: larger mitochondria supported proportionally greater Ca2+ signal mass, with an exponential fit explaining 73% of the variance (Figure 5E). No low-volume cell achieved the Ca2+ output seen in high-volume cells, indicating that organelle size imposes an upper limit on signaling capacity. Hence, across all pacemaker cells studied, larger mitochondrial networks are functionally matched to higher Ca2+ loads, establishing mitochondrial volume as a principal structural correlate of energetic demand.

Beat-locked Ca2+ transients trigger cytosolic ATP increases in SA node myocytes

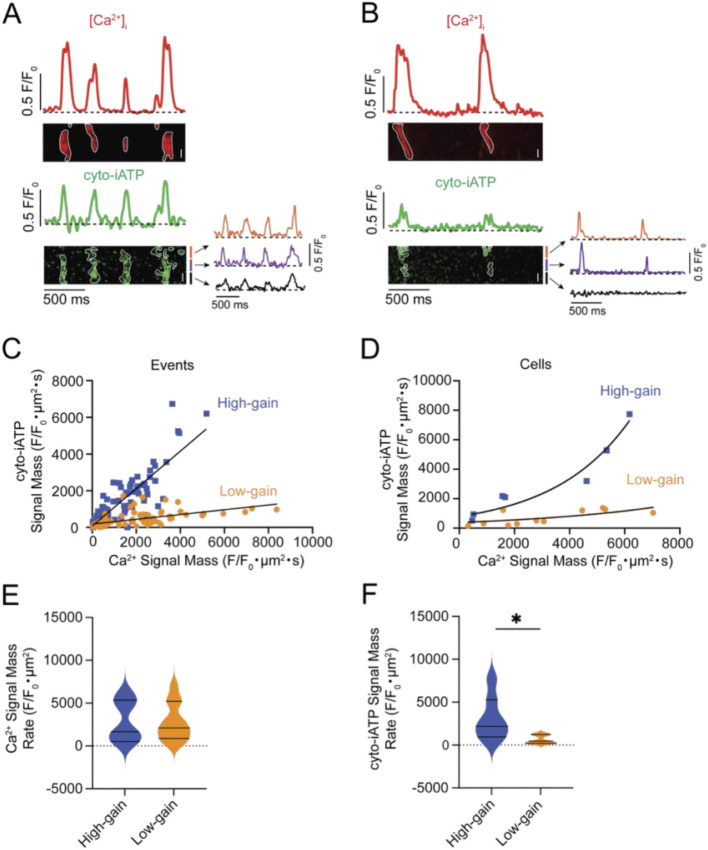

Having shown that mitochondrial volume scales with the Ca2+ burden that a cell must service, we next asked whether the timing of Ca2+ release likewise governs the beat-to-beat rise of ATP in the cytosol, turning structural capacity into real-time metabolic output. To do this, we loaded dissociated SA node myocytes expressing cyto-iATP with the red-shifted Ca2+ indicator Rhod-3 and simultaneously tracked cytosolic ATP and Ca2+ using a confocal microscope in line-scan mode (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Beat-locked Ca2+ release elicits bimodal high- and low-gain cytosolic ATP (cyto-iATP) transients in SA node myocytes.

Representative line-scan recordings showing simultaneous Ca2+ transients (red; top) and cyto-iATP signals (green; bottom) from SA node cells classified as high- (A) or low-gain (B) cyto-iATP. Traces correspond to normalized fluorescence (F/F₀) for Ca2+ (red) and cyto-iATP (green), with corresponding line-scan images below. Individual events are outlined in white. Orange, purple, and black traces indicate normalized fluorescence intensity from local cyto-iATP microdomains. (C) Event-level relationship between Ca2+ signal mass and cyto-iATP signal mass for all detected events. High-gain (blue squares) and low-gain (orange circles) events were fit with linear functions (high-gain slope = 1.02 Δcyto-iATP/ΔCa2+; low-gain slope = 0.13 Δcyto-iATP/ΔCa2+) (high-gain: N = 5 mice, n = 167 events ; low-gain: N = 5 mice, n = 180 events;). (D) Cell-averaged Ca2+–cyto-iATP signal mass relationship. High- and low-gain cells were fit with exponential functions (high gain: N = 5 mice, n = 7 cells ; low gain: N = 5 mice, n = 11 cells). (E) Violin plots of Ca2+ signal-mass rates (F/F₀·μm2) for high- and low-gain cells. (F) Violin plots of cyto-iATP signal-mass rates (F/F₀·μm2) for high- and low-gain cells (high-gain; N = 5 mice, n = 7 cells; low-gain: N = 5 mice, n = 11 cells; P = 0.0208). Scale bars, 5 μm.

Simultaneous line-scan imaging of Ca2+ release and cyto-iATP fluorescence in two representative pacemaker cells with high (Figure 6A) and low (Figure 6B) frequency of Ca2+-release events showed that, in both cases, every Ca2+-release event is paired with a rise in cytosolic ATP, confirming beat-locked metabolic coupling. The spatial extent of the ATP rise was found to differ markedly: in the high-frequency cell (Figure 6A), the increase was spread across a much broader swath of the cytoplasm, whereas in the low-frequency cell (Figure 6B), the increase was restricted to a narrow segment. Quantitative differences in these patterns, exemplified by traces from three regions of interest shown beneath each cyto-iATP image, highlight localized versus widespread ATP transients.

Given the variations in spatial distributions, we quantified the signal mass of Ca2+ signals and their associated cyto-iATP events. As shown in Figure 6C, pooled events from all cells imaged segregated into two groups, both of which could be fit to linear functions distinguished by the different slopes of their Ca2+-ATP relationships: 1.02 Δcyto-iATP/ΔCa2+ for high-gain events and 0.12 Δcyto-iATP/ΔCa2+ for low-gain events (P < 0.0001). Notably, plotting averaged cyto-iATP and Ca2+ signal mass per cell segregated the data into two clear gain regimes: a low-gain group with minimal ATP amplification and a high-gain group with steep, exponential Ca2+-to-ATP coupling (Figure 6D).

Despite the similarity of Ca2+ signal-mass rate (Figure 6E) across phenotypes, cyto-iATP signal-mass rate was significantly larger in high-gain cells (P = 0.0208), underscoring the higher energetic output in these cells over time (Figure 6F). This dichotomy mirrors the intact node, where superior myocytes exhibit greater signal-mass rates than inferior myocytes, and was reinforced by higher event frequencies in high-gain cells (2.56 ± 0.16 Hz) versus low-gain cells (1.50 ± 0.18 Hz; P = 0.003), closely matching regional values in tissue (Figure 3). Kinetic analysis of Ca2+ transients showed slower dynamics in high-gain cells, with a longer decay constant (τ = 198.2 ± 39.3 ms; P = 0.0175) and prolonged duration (405.0 ± 48.8 ms; P = 0.0413) compared with low-gain cells (τ = 91.7 ± 11.2 ms; 298.5 ± 24.5 ms) (Figure S3A–E). In contrast, cyto-iATP transients exhibited comparable rise times in high-gain (101.8 ± 7.4 ms) and low-gain cells (99.7 ± 8.2 ms), with similar decay constants (τ ≈ 96–130 ms) and durations (~270.9–289.8 ms) (Figure S3F–H).

Thus, cytosolic ATP output in pacemaker myocytes is not simply proportional to Ca2+ load but instead falls into discrete high- and low-gain modes, echoing the superior–inferior metabolic hierarchy of the intact SA node.

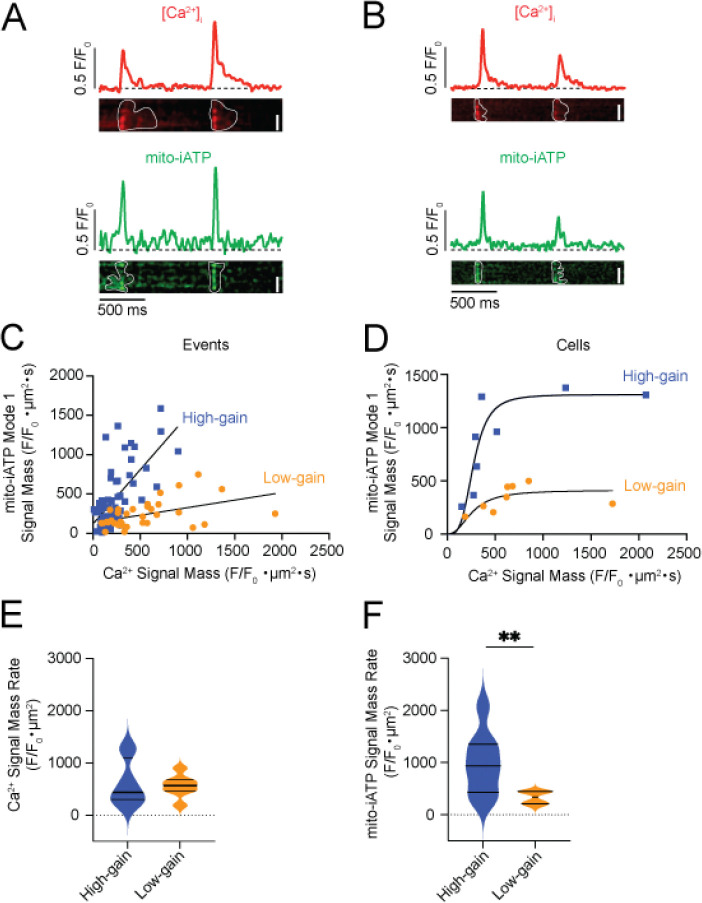

High- and low-gain mitochondrial ATP production in SA node myocytes

We found that Mode 1 events—rapid post-beat rises in mito-iATP—are tightly beat-locked, with Ca2+ transients preceding ATP onset by <50 ms, consistent with rapid SR-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer gating oxidative phosphorylation. The magnitude of ATP elevation per unit Ca2+ load varied sharply between cells. Representative high-gain cells (Figure 7A) produced broad, high-amplitude ATP increases spanning most of the scan region, while low-gain cells (Figure 7B) generated smaller, spatially restricted rises, despite comparable Ca2+ signals.

Figure 7: Beat-locked Mode 1 mito-ATP transients bifurcate into high- and low-gain phenotypes in SA node myocytes.

Representative line-scan recordings showing simultaneous Ca2+ transients (red; top) and mito-iATP signals (green; bottom) from SA node myocytes classified as high- (A) or low- mito-iATP gain (B). Traces correspond to normalized fluorescence (F/F₀) for Ca2+ (red) and mito-iATP (green), with corresponding line-scan images below. Individual events are outlined in white. (C) Event-level relationship between Ca2+ signal mass and mito-iATP signal mass for all individual detected events. The high (blue squares) and low (orange circles) mito-iATP gain events were fit with a linear function (high-gain slope= 1.38 Δmito-iATP/ΔCa2+; low-gain slope= 0.19 Δmito-iATP/ΔCa2+) (high-gain N = 4 mice, n = 60 events; low-gain N = 4 mice, n = 94 events). (D) Cell-averaged Ca2+ mito-iATP signal mass relationship. The high (orange circles) and low (blue squares) mito-iATP gain cells were fit with a cooperative Hill equation (high-gain N = 4 mice, n = 8 cells; low-gain N = 4 mice, n = 8 cells). (E) Violin plots of Ca2+ signal-mass rates (F/F₀·μm2) for high- and low-gain cells. (F) Violin plots of mito-iATP signal-mass rates (F/F₀·μm2) from high- and low-gain cells (high gain N = 4 mice, n = 8 cells; low-gain N = 4 mice, n = 8 cells; mito-iATP signal mass p = 0.0083). Scale bars, 5 μm.

Pooling the signal mass of all associated Ca2+ and mito-iATP events across cells yielded an apparently piecewise-linear Ca2+–ATP relation with two regimes (low slope 0.19 Δmito-iATP/ΔCa2+; high slope 1.38; Figure 7C), but because events are nested within cells this marginal pattern reflects aggregation. Accordingly, per-cell fits showed Hill models with greater apparent cooperativity in high-gain cells (Hill coefficients 3.60 vs. 2.35) and distinct plateaus (Figure 7D). The sigmoidal behavior is expected from thresholded, cooperative mitochondrial Ca2+ control—MICU1/2 gatekeeping of the MCU sets a Ca2+ threshold and gain (Mallilankaraman et al., 2012; Csordas et al., 2013; Kamer et al., 2017). Plateau differences imply capacity differences: the lower maximum output (ceiling) in low-gain cells is consistent with reduced mitochondrial mass and/or diminished per-mitochondrion respiratory capacity. It is important note, however, that because iATPSnFR family sensors have finite dynamic ranges and can saturate at high ATP (Lobas et al., 2019; Marvin et al., 2024; Rhana et al., 2024), the upper plateau in high-gain cells could partly reflect sensor saturation rather than biology, so ceiling differences are interpreted cautiously.

We extended the analysis by calculating Ca2+ and mito-iATP signal-mass rates (total signal mass per trace divided by recording time), which index Ca2+ load and ATP production over time rather than per-event yield. Ca2+ signal-mass rate did not differ between groups (Figure 7E), whereas mito-iATP signal-mass rate was higher in high-gain cells (P = 0.0083) (Figure 7F). Per-cell averages corroborated the two phenotypes, with high-gain cells firing faster (2.49 ± 0.59 Hz vs 0.92 ± 0.12 Hz; P = 0.0164). For Ca2+ transients, rise times did not differ significantly (93.8 ± 12.1 ms vs 72.3 ± 7.1 ms), but high-gain cells exhibited slower decay (τ = 156.9 ± 29.1 ms vs 89.7 ± 20.2 ms) and longer duration (391.2 ± 45.2 ms vs 251.4 ± 37.4 ms) (Figure S4A, C–E). Mito-iATP event kinetics were similar between groups (rise time 86.1 ± 11.7 ms vs 77.7 ± 16.1 ms; decay τ ≈ 98–101 ms; duration ~275–283 ms) (Figure S4A, F–H).

Thus, Mode-1 mitochondrial ATP production is stratified into low- and high-gain phenotypes with shallower vs. steeper Ca2+–ATP gain; high-gain cells rapidly mobilize ATP once a Ca2+ gate is crossed and operate nearer a higher ceiling, whereas low-gain cells exhibit a lower ceiling and approach saturation only at higher Ca2+ loads. This functional dichotomy echoes the superior–inferior metabolic hierarchy of the intact SA node, revealing that intrinsic cooperativity shapes not only the magnitude but also the dynamic range of pacemaker cell bioenergetics.

High- and low-load mitochondrial ATP consumption in SA node myocytes

As in intact SA nodes, we detected Mode-2 events—transient mito-iATP dips following each Ca2+ transient—indicating rapid, beat-synchronous ATP depletion in the matrix mitochondria in isolated myocytes (Figure 8). Plotting mito-iATP dip signal mass versus Ca2+ signal mass (Figure 8A, B) revealed two regimes separated by an empirical Ca2+ threshold of ~2,000 F/F0·μm2·s: below this threshold, events formed a dense, shallow-dip cluster (slope = −0.07 Δmito-iATP/ΔCa2+), whereas above it, dips deepened with increasing Ca2+ load (slope = −0.26 Δmito-iATP/ΔCa2+), as summarized in Figure 8C, D. High-load cells drew down ~2-fold more mitochondrial ATP per beat (−905.9 ± 162.3 vs −407.4 ± 82.4 F/F₀·μm2·s) and fired faster (2.11 ± 0.20 vs 1.08 ± 0.23 Hz; Figure S5C). For Ca2+ transients, rise time was longer in low-load cells (94.1 ± 5.3 ms) than in high-load cells (79.2 ± 5 ms), while decay (τ = 89.7–96.3 ms) and duration (≈257–280 ms) were similar (Figure S5A–F). Mode-2 mito-iATP kinetics did not differ between groups (rise 99.3–103.0 ms, τ = 89.7–96.3 ms, duration 257.7–341.9 ms; Figure S5G–I).

Figure 8: Beat locked Mode 2 mito-ATP dips bifurcate into high- and low-load phenotypes in SA node myocytes.

Representative line-scan recordings showing simultaneous Ca2+ transients (red; top) and Mode 2 mito-iATP signals (green; bottom) from SA node myocytes classified as high- (A) or low-load (B) mito-iATP consumption. Traces correspond to normalized fluorescence (F/F₀) for Ca2+ (red) and mito-iATP (green), with corresponding line-scan images below. Individual events are outlined in white. (C) Event-level relationship between Ca2+ signal mass and Mode 2 mito-iATP signal mass for all detected events. High-load (blue squares) and low-load (orange circles) events were fit with linear functions (high-load slope = −0.26 Δmito-iATP/ΔCa2+; low-load slope = −0.07 Δmito-iATP/ΔCa2+) (high-load: N = 4 mice, n = 98 events; low-load: N = 4 mice, n = 83 events). (D) Cell-averaged Ca2+–mito-iATP signal mass relationship. High-load (blue squares) and low-load (orange circles) cells were fit with linear functions (high-load: N = 4 mice, n = 5 cells; low-load: N = 4 mice, n = 9 cells). Scale bars, 5 μm.

Thus, mitochondrial ATP consumption is stratified into low- and high-load phenotypes: cells with mito-iATP dips above ~2,000 F/F0·μm2·s consume disproportionately more ATP per beat, whereas cells below this threshold consume less despite similar Ca2+ inputs, indicating discrete utilization modes that likely contribute to metabolic specialization within the node.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that ATP production in SA node myocytes is synchronized to each heartbeat rather than being produced continuously and is confined to discrete metabolic microdomains. By imaging mitochondrial ATP alongside Ca2+ transients, we observed recurring “ATP-gain” peaks and “ATP-dip” troughs whose magnitudes and timing matched the electrical cycle, revealing a just-in-time energetic budget tailored to beat-by-beat ionic demand.

Regional analyses uncovered pronounced heterogeneity along the node. Superior SA node myocytes, which possess greater mitochondrial volume and reside in regions of higher capillary density, displayed larger ATP gains and higher diastolic [ATP]i than inferior cells, in line with their faster basal firing rates. Pharmacological experiments illuminated SR-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer as the proximate trigger for oxidative phosphorylation: thapsigargin abolished ATP oscillations by preventing SR Ca2+ refilling, whereas blocking depolarizing HCN channels with ivabradine simply slowed their frequency without affecting their amplitude, demonstrating that the Ca2+ clock governs metabolic activation upstream of the membrane voltage clock.

These structure–function correlations extend earlier anatomical work showing a superior-to-inferior vascular gradient in the mouse node (Grainger et al., 2021). Manning et al. (2024) linked chronic under-perfusion to HIF-1α activation, SERCA down-regulation, and reduced PGC-1α–dependent mitochondrial biogenesis. Our results place this hypoxia–HIF cascade within the nodal context, supporting the conclusion that microvascular “wealth” establishes the mitochondrial “capital” available for rapid ATP payouts.

The dominant pacemaking locus within the SA node is likewise dynamic, migrating along the superior–inferior axis in response to changes in autonomic tone (Yamamoto et al., 1998; Boyett et al., 2000; Brennan et al., 2020). Optical mapping of ex vivo rat and human preparations demonstrates the coexistence of two discrete initiation sites—a richly vascularized, mitochondria-dense superior focus and a comparatively hypoperfused inferior focus—that alternate leadership according to sympathetic versus parasympathetic drive (Brennan et al., 2020). Our findings place firm energetic limits on this plasticity: when initiation shifts toward the inferior node, the lower capillary density, reduced mitochondrial reserve, and smaller beat-to-beat ATP gains of this region constrain the maximal rate it can sustain. Thus, although the pacemaker center can relocate, the performance of the newly recruited site remains bounded by the surrounding microvascular and metabolic landscape that we have mapped.

Our analysis revealed two coupling modes in pacemaker myocytes. Mode 1 is characterized by beat-locked mitochondrial ATP “gains” and exhibits two phenotypes: a high-gain subtype in which modest Ca2+ transients elicit steep ATP increases, and a low-gain subtype with a shallower Ca2+ -to-ATP coupling slope. Mode 2 shows mitochondrial ATP “dips” that scale linearly and inversely with Ca2+ load, consistent with consumption-dominated control. Together, these phenotypes underscore heterogeneity in SR–mitochondrial communication, likely reflecting differences in Ca2+ transfer efficacy, mitochondrial reserve, and local substrate availability.

While our experiments establish the existence of high- and low-gain ATP responses, they do not resolve the underlying molecular determinants. We therefore propose two testable hypotheses for future work: 1) a structure-centric model based on differential SR–mitochondria tethering, and 2) a biochemical framework centered on variable oxidative phosphorylation capacity. In the first case, superior pacemaker cells may express more Mfn2 (or other tethers), narrowing the SR–mitochondrial cleft and amplifying beat-triggered Ca2+ transfer. In this scenario, inferior cells, with sparser coupling, would receive smaller mitochondrial Ca2+ pulses and thus operate at lower metabolic gain. In the second case, high-gain cells would harbor a denser complex-V proteome (e.g., greater ATP5A content), allowing faster ATP synthesis per unit Ca2+. In this scenario, low-gain cells, with reduced ATP5A abundance, would be constrained to shallower slopes. These structural (coupling) and biochemical (flux capacity) gradients together offer a plausible framework for the dual-gain behavior we observe and define a roadmap for future mechanistic dissection.

It is important to place our findings in the context of two classical synchronization mechanisms that operate in oscillatory biological networks: entrainment and stochastic resonance. Entrainment refers to the mutual electrotonic coupling of self-oscillating myocytes, whereby the cell or region with the shortest intrinsic cycle length imposes its rhythm on its neighbors, achieving network-wide phase alignment (Jalife, 1984; Anumonwo et al., 1991). This process is most efficient when all cells possess comparable metabolic reserves, as would be expected in a node endowed with uniformly high vascular density that affords each myocyte abundant mitochondrial ATP production. Stochastic resonance, in contrast, is a nonlinear phenomenon in which intrinsic noise enhances the detection or propagation of weak periodic signals (Wiesenfeld and Moss, 1995; Gammaitoni et al., 1998; Hanggi, 2002). In the SA node, such noise can originate from metabolically constrained, intermittently firing cells situated in regions of sparse perfusion (Grainger et al., 2021; Guarina et al., 2022). When microvascular rarefaction creates metabolic heterogeneity, the resulting juxtaposition of high-gain and low-gain myocytes can harness stochastic resonance, preserving overall heart-rate frequency and periodicity, even as localized pockets of low excitability emerge.

A growing literature demonstrates pronounced electrophysiological heterogeneity along the SA node (Boyett et al., 2000). High-resolution 3D imaging showed that Ca2+ transients in the intact mouse SA node propagate discontinuously and asynchronously, arising from spatially heterogeneous local Ca2+ release events within the HCN4+/Cx43− meshwork (Kim et al., 2018; Monfredi et al., 2018; Bychkov et al., 2020). Complementary work revealed parallel heterogeneity in vascular density, membrane excitability, and Ca2+ signaling along the longitudinal axis of the node (Grainger et al., 2021). Such variability motivated the hypothesis that intrinsic noise sharpens pacemaker timing via stochastic resonance (Clancy and Santana, 2020; Grainger et al., 2021; Guarina et al., 2022). A recent multiscale study confirmed that such noise fine tunes SA node firing and preserves rhythmicity under strong parasympathetic drive (Okamura et al., 2024). Collectively, these data establish microscopic heterogeneity—spanning structure, metabolism, and electrical behavior—as an intrinsic feature of native SA node tissue that critically modulates its function.

Our current findings provide a metabolic explanation for this variability: inferior SA node myocytes, constrained by sparse vascular supply and limited mitochondrial reserve, behave as low frequency, intermittently firing “noise generators.” Observations of beat-locked mitochondrial ATP dips in Mode 2 cells confirm that, because of their half-recovery time of ~125 ms, these dip-dominant cells cannot entrain to the rapid rates sustained by gain-dominant neighbors at 8–10 Hz. Instead, the pronounced variability in ATP-withdrawal and -recovery kinetics creates the metabolic noise required for stochastic resonance, such that subthreshold fluctuations in membrane potential driven by deep ATP dips enhance the sensitivity of electrotonically coupled networks to depolarizing inputs from well-perfused, high-gain cells. Importantly, beat-locked mito-iATP dips reveal that dip-dominant cells, which require ~125 ms for half-recovery, cannot follow 8–10 Hz pacing and instead likely serve as intrinsic noise generators, providing the first metabolic assay capable of distinguishing entrainment from stochastic resonance. Our model predicts maximal network coherence when these low-gain, noise-generator cells are coupled to high-gain, well-perfused superior myocytes; this aligns with our experimental finding that collapsing mitochondrial reserve with FCCP or thapsigargin abolishes resonance, underscoring its metabolic origin.

While our experiments were performed in the murine SA node, the concepts we propose have broad applicability, as the bioenergetic machinery we interrogate—mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, TCA cycle activation, and oxidative phosphorylation— are widely conserved. Thus, the insights gained in murine models likely translate broadly, including to human cardiac physiology. Consistent with this premise, Tagirova Sirenko et al. (2021) showed that the fundamental pacemaking architecture of mouse and human SA node cells is essentially the same. We therefore anticipate that the electro-metabolic principles revealed here will apply to any excitable tissue or intrinsic pacemaker. Notably, when our nodal data are integrated with ventricular observations (Rhana et al., 2024; Rhana et al., 2025), a unified framework emerges: ionic and Ca2+ clocks set beat-to-beat electrical demand; SR-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer synchronizes oxidative phosphorylation to that demand; and regional capillary density fixes mitochondrial content, thereby defining the ceiling for ATP production.

The clinical relevance of this supply-limited phenotype is underscored by a mouse model of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in which selective rarefaction of superior-node capillaries precedes bradycardia and heightened beat-to-beat variability (Manning et al., 2025). We found that rarefaction compromises pacemaker robustness, even when global cardiac output remains normal, indicating that local vascular loss can destabilize rhythm before systemic hemodynamics decline. In the context of this study, however, microvascular rarefaction sculpts pockets of diminished mitochondrial reserve and low excitability, narrowing the roster of regions capable of sustaining high-frequency pacing. When such hypoperfused zones remain interlaced with well-supplied tissue, noise-assisted integration between low-gain and high-gain myocytes can act as a metabolic safety mechanism, injecting timing noise that preserves overall heart-rate frequency and beat-to-beat regularity despite localized deficits. Thus, while the leading pacemaker remains mobile, its performance—and resilience—are ultimately governed by the interplay among vascular architecture, mitochondrial content, and microdomain ATP dynamics.

In summary, our work extends a unified “paycheck-to-paycheck” model of cardiac energetics from ventricular myocytes to the pacemaker SA node. In this view, every heartbeat is supported by ATP that is generated, used, and renewed on a cycle-by-cycle basis: ionic and Ca2+ clocks set the rate at which ATP is produced; SR-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer generates ATP via oxidative phosphorylation; and local vascular supply determines the O2 supply needed to generate it. Whether a cell initiates the rhythm or follows it, its electrical and mechanical output is underwritten by the same just-in-time metabolic calculus. Variations in capillary density or mitochondrial content therefore shape not only contractile power but also the locus and stability of pacemaking. Recognizing that the heart is an organ that functions on the capacity of each beat to generate the ATP it needs for excitation-contraction coupling provides a common framework for interpreting how supply–demand mismatches give rise to arrhythmias, bradycardia, and pump failure across diverse physiological and pathological settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Robert Cudmore for helpful discussions.

Funding

The project was supported by NIH grant HL168874 (LFS) and the American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (https://doi.org/10.58275/AHA.25POST1378853.pc.gr.227467) (PR).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement

The raw data files supporting all findings presented in this paper are available from the corresponding author.

References

- Anumonwo J.M., Delmar M., Vinet A., Michaels D.C., and Jalife J.. 1991. Phase resetting and entrainment of pacemaker activity in single sinus nodal cells. Circ Res. 68:1138–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov K.Y., Vinogradova T.M., and Lakatta E.G.. 2001. Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchanger: molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ Res. 88:1254–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyett M.R., Honjo H., and Kodama I.. 2000. The sinoatrial node, a heterogeneous pacemaker structure. Cardiovasc Res. 47:658–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J.A., Chen Q., Gams A., Dyavanapalli J., Mendelowitz D., Peng W., and Efimov I.R.. 2020. Evidence of Superior and Inferior Sinoatrial Nodes in the Mammalian Heart. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 6:1827–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H., and Difrancesco D.. 1980. Voltage-clamp investigations of membrane currents underlying pace-maker activity in rabbit sino-atrial node. J Physiol. 308:331–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov R., Juhaszova M., Tsutsui K., Coletta C., Stern M.D., Maltsev V.A., and Lakatta E.G.. 2020. Synchronized Cardiac Impulses Emerge From Heterogeneous Local Calcium Signals Within and Among Cells of Pacemaker Tissue. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 6:907–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Csordas G., Jowdy C., Schneider T.G., Csordas N., Wang W., Liu Y., Kohlhaas M., Meiser M., Bergem S., Nerbonne J.M., Dorn G.W. 2nd, and Maack C.. 2012. Mitofusin 2-containing mitochondrial-reticular microdomains direct rapid cardiomyocyte bioenergetic responses via interorganelle Ca(2+) crosstalk. Circ Res. 111:863–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy C.E., and Santana L.F.. 2020. Evolving Discovery of the Origin of the Heartbeat: A New Perspective on Sinus Rhythm. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 6:932–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas G., Golenar T., Seifert E.L., Kamer K.J., Sancak Y., Perocchi F., Moffat C., Weaver D., Perez S.F., Bogorad R., Koteliansky V., Adijanto J., Mootha V.K., and Hajnoczky G.. 2013. MICU1 controls both the threshold and cooperative activation of the mitochondrial Ca(2)(+) uniporter. Cell Metab. 17:976–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton R.M., and McCormack J.G.. 1990. Ca2+ as a second messenger within mitochondria of the heart and other tissues. Annu Rev Physiol. 52:451–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton R.M., McCormack J.G., and Edgell N.J.. 1980. Role of calcium ions in the regulation of intramitochondrial metabolism. Effects of Na+, Mg2+ and ruthenium red on the Ca2+-stimulated oxidation of oxoglutarate and on pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in intact rat heart mitochondria. Biochem J. 190:107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D. 1986. Characterization of single pacemaker channels in cardiac sino-atrial node cells. Nature. 324:470–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn G.W. 2nd, Song M., and Walsh K.. 2015. Functional implications of mitofusin 2-mediated mitochondrial-SR tethering. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 78:123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske S., Hennis K., Rotzer R.D., Brox V.F., Becirovic E., Scharr A., Gruner C., Ziegler T., Mehlfeld V., Brennan J., Efimov I.R., Pauza A.G., Moser M., Wotjak C.T., Kupatt C., Gonner R., Zhang R., Zhang H., Zong X., Biel M., and Wahl-Schott C.. 2020. cAMP-dependent regulation of HCN4 controls the tonic entrainment process in sinoatrial node pacemaker cells. Nat Commun. 11:5555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammaitoni L., Hänggi P., Jung P., and Marchesoni F.. 1998. Stochastic resonance. Reviews of Modern Physics. 70:223–287. [Google Scholar]

- Garbincius J.F., and Elrod J.W.. 2022. Mitochondrial calcium exchange in physiology and disease. Physiol Rev. 102:893–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrud T.A.C., Bell B., Mata-Daboin A., Peixoto-Neves D., Collier D.M., Cordero-Morales J.F., and Jaggar J.H.. 2024. WNK kinase is a vasoactive chloride sensor in endothelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 121:e2322135121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger N., Guarina L., Cudmore R.H., and Santana L.F.. 2021. The Organization of the Sinoatrial Node Microvasculature Varies Regionally to Match Local Myocyte Excitability. Function (Oxf). 2:zqab031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarina L., Le J.T., Griffith T.N., Santana L.F., and Cudmore R.H.. 2024. SanPy: Software for the analysis and visualization of whole-cell current-clamp recordings. Biophys J. 123:759–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarina L., Moghbel A.N., Pourhosseinzadeh M.S., Cudmore R.H., Sato D., Clancy C.E., and Santana L.F.. 2022. Biological noise is a key determinant of the reproducibility and adaptability of cardiac pacemaking and EC coupling. J Gen Physiol. 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanggi P. 2002. Stochastic resonance in biology. How noise can enhance detection of weak signals and help improve biological information processing. Chemphyschem. 3:285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huser J., Blatter L.A., and Lipsius S.L.. 2000. Intracellular Ca2+ release contributes to automaticity in cat atrial pacemaker cells. J Physiol. 524 Pt 2:415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalife J. 1984. Mutual entrainment and electrical coupling as mechanisms for synchronous firing of rabbit sino-atrial pace-maker cells. J Physiol. 356:221–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamer K.J., Grabarek Z., and Mootha V.K.. 2017. High-affinity cooperative Ca(2+) binding by MICU1-MICU2 serves as an on-off switch for the uniporter. EMBO Rep. 18:1397–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.S., Maltsev A.V., Monfredi O., Maltseva L.A., Wirth A., Florio M.C., Tsutsui K., Riordon D.R., Parsons S.P., Tagirova S., Ziman B.D., Stern M.D., Lakatta E.G., and Maltsev V.A.. 2018. Heterogeneity of calcium clock functions in dormant, dysrhythmically and rhythmically firing single pacemaker cells isolated from SA node. Cell Calcium. 74:168–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirichok Y., Krapivinsky G., and Clapham D.E.. 2004. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature. 427:360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobas M.A., Tao R., Nagai J., Kronschlager M.T., Borden P.M., Marvin J.S., Looger L.L., and Khakh B.S.. 2019. A genetically encoded single-wavelength sensor for imaging cytosolic and cell surface ATP. Nat Commun. 10:711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopaschuk G.D., Karwi Q.G., Tian R., Wende A.R., and Abel E.D.. 2021. Cardiac Energy Metabolism in Heart Failure. Circ Res. 128:1487–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallilankaraman K., Doonan P., Cardenas C., Chandramoorthy H.C., Muller M., Miller R., Hoffman N.E., Gandhirajan R.K., Molgo J., Birnbaum M.J., Rothberg B.S., Mak D.O., Foskett J.K., and Madesh M.. 2012. MICU1 is an essential gatekeeper for MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake that regulates cell survival. Cell. 151:630–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni M.E., Traboulsie A., Leoni A.L., Couette B., Marger L., Le Quang K., Kupfer E., Cohen-Solal A., Vilar J., Shin H.S., Escande D., Charpentier F., Nargeot J., and Lory P.. 2006. Bradycardia and slowing of the atrioventricular conduction in mice lacking CaV3.1/alpha1G T-type calcium channels. Circ Res. 98:1422–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning D., Rivera E.J., Rhana P., Matsumoto C., Fong Z., Thai P.N., Munoz M.F., Contreras J.E., Kim S., Grainger N., Chiamvimonvat N., Bautista G.M., and Santana L.F.. 2025. Microvascular Rarefaction in the Sinoatrial Node: A Potential Mechanism for Pacemaker Dysfunction in Early HFpEF. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning D., Rivera E.J., and Santana L.F.. 2024. The life cycle of a capillary: Mechanisms of angiogenesis and rarefaction in microvascular physiology and pathologies. Vascul Pharmacol. 156:107393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin J.S., Kokotos A.C., Kumar M., Pulido C., Tkachuk A.N., Yao J.S., Brown T.A., and Ryan T.A.. 2024. iATPSnFR2: A high-dynamic-range fluorescent sensor for monitoring intracellular ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 121:e2314604121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J.G., Halestrap A.P., and Denton R.M.. 1990. Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiol Rev. 70:391–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monfredi O., Tsutsui K., Ziman B., Stern M.D., Lakatta E.G., and Maltsev V.A.. 2018. Electrophysiological heterogeneity of pacemaker cells in the rabbit intercaval region, including the SA node: insights from recording multiple ion currents in each cell. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 314:H403–H414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura A., He I.K., Wang M., Malsev A.V., Maltsev A.V., Stern M.D., Lakatta E.G., and Maltsev V.A.. 2024. Cardiac Pacemaker Cells Harness Stochastic Resonance to Ensure Fail-Safe Operation at Low Rates Bordering on Sinus Arrest. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Rhana P., Matsumoto C., Fong Z., Costa A.D., Del Villar S.G., Dixon R.E., and Santana L.F.. 2024. Fueling the heartbeat: Dynamic regulation of intracellular ATP during excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 121:e2318535121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhana P., Matsumoto C., and Santana L.F.. 2025. Demonstration of Beat-to-Beat, On-Demand ATP Synthesis in Ventricular Myocytes Reveals Sex-Specific Mitochondrial and Cytosolic Dynamics. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Saddik M., and Lopaschuk G.D.. 1991. Myocardial triglyceride turnover and contribution to energy substrate utilization in isolated working rat hearts. J Biol Chem. 266:8162–8170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagirova Sirenko S., Tsutsui K., Tarasov K.V., Yang D., Wirth A.N., Maltsev V.A., Ziman B.D., Yaniv Y., and Lakatta E.G.. 2021. Self-Similar Synchronization of Calcium and Membrane Potential Transitions During Action Potential Cycles Predict Heart Rate Across Species. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 7:1331–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeld K., and Moss F.. 1995. Stochastic resonance and the benefits of noise: from ice ages to crayfish and SQUIDs. Nature. 373:33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisneski J.A., Stanley W.C., Neese R.A., and Gertz E.W.. 1990. Effects of acute hyperglycemia on myocardial glycolytic activity in humans. J Clin Invest. 85:1648–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Honjo H., Niwa R., and Kodama I.. 1998. Low-frequency extracellular potentials recorded from the sinoatrial node. Cardiovasc Res. 39:360–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv Y., Spurgeon H.A., Ziman B.D., Lyashkov A.E., and Lakatta E.G.. 2013. Mechanisms that match ATP supply to demand in cardiac pacemaker cells during high ATP demand. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 304:H1428–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., and Tian R.. 2018. Mitochondrial dysfunction in pathophysiology of heart failure. J Clin Invest. 128:3716–3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data files supporting all findings presented in this paper are available from the corresponding author.