Abstract

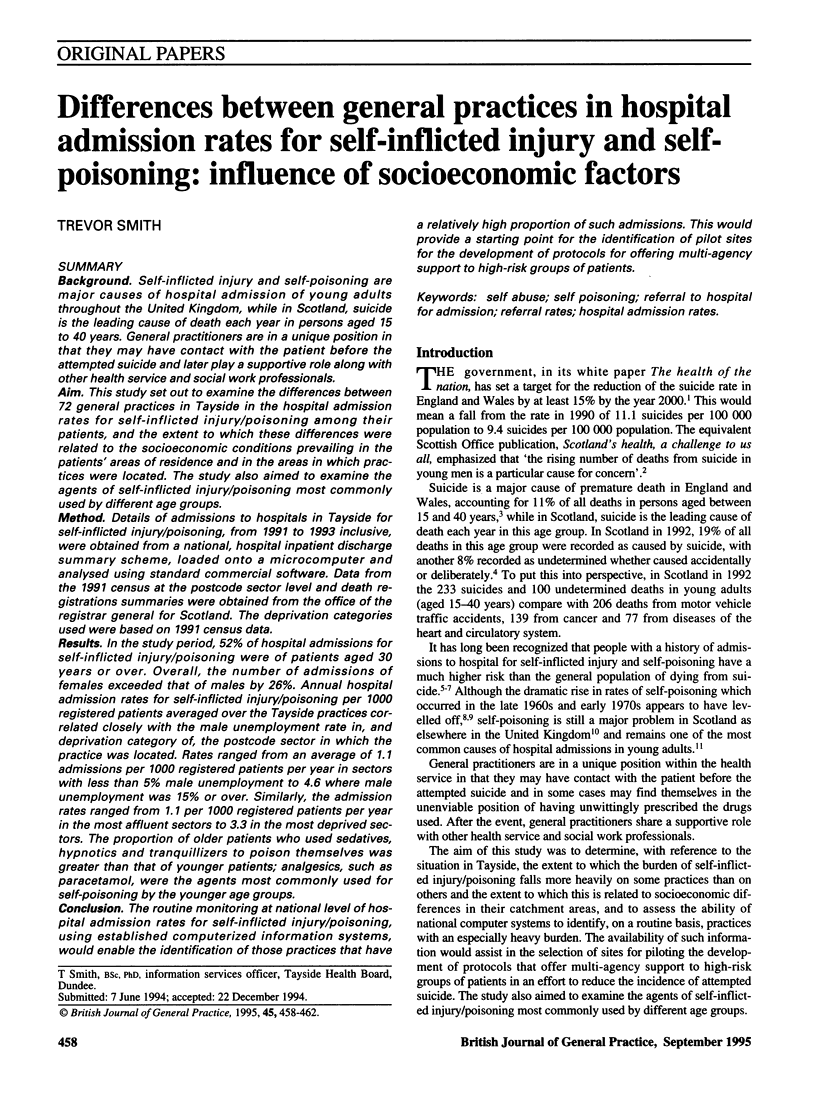

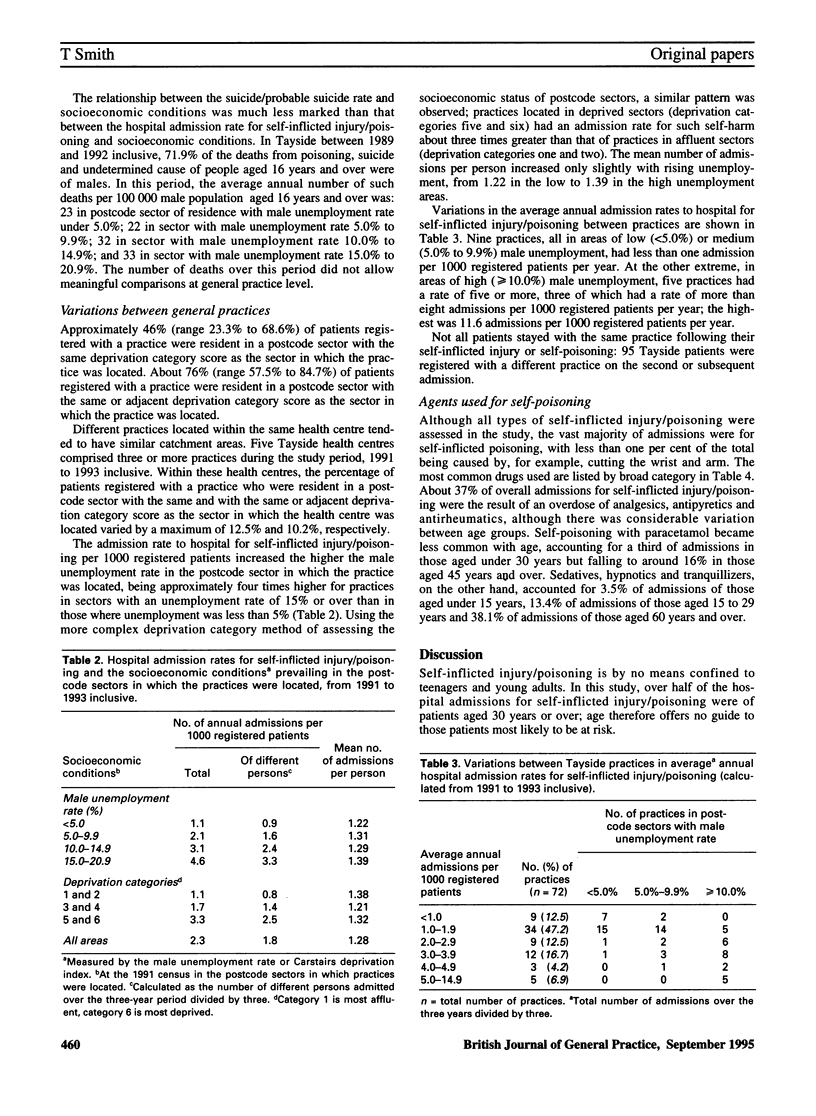

BACKGROUND. Self-inflicted injury and self-poisoning are major causes of hospital admission of young adults throughout the United Kingdom, while in Scotland, suicide is the leading cause of death each year in persons aged 15 to 40 years. General practitioners are in a unique position in that they may have contact with the patient before the attempted suicide and later play a supportive role along with other health service and social work professionals. AIM. This study set out to examine the differences between 72 general practices in Tayside in the hospital admission rates for self-inflicted injury/poisoning among their patients, and the extent to which these differences were related to the socioeconomic conditions prevailing in the patients' areas of residence and in the areas in which practices were located. The study also aimed to examine the agents of self-inflicted injury/poisoning most commonly used by different age groups. METHOD. Details of admissions to hospitals in Tayside for self-inflicted injury/poisoning, from 1991 to 1993 inclusive, were obtained from a national, hospital inpatient discharge summary scheme, loaded onto a microcomputer and analysed using standard commercial software. Data from the 1991 census at the postcode sector level and death registrations summaries were obtained from the office of the registrar general for Scotland. The deprivation categories used were based on 1991 census data. RESULTS. In the study period, 52% of hospital admissions for self-inflicted injury/poisoning were of patients aged 30 years or over. Overall, the number of admissions of females exceeded that of males by 26%. Annual hospital admission rates for self-inflicted injury/poisoning per 1000 registered patients averaged over the Tayside practices correlated closely with the male unemployment rate in, and deprivation category of, the postcode sector in which the practice was located. Rates ranged from an average of 1.1 admissions per 1000 registered patients per year in sectors with less than 5% male unemployment of 4.6 where male unemployment was 15% or over. Similarly, the admission rates ranged from 1.1 per 1000 registered patients per year in the most affluent sectors to 3.3 in the most deprived sectors. The proportion of older patients who used sedatives, hypnotics and tranquillizers to poison themselves was greater than that of younger patients; analgesics, such as paracetamol, were the agents most commonly used for self-poisoning by the younger age groups. CONCLUSION. The routine monitoring at national level of hospital admission rates for self-inflicted injury/poisoning, using established computerized information systems, would enable the identification of those practices that have a relatively high proportion of such admissions. This would provide a starting point for the identification of pilot sites for the development of protocols for offering multi-agency support to high-risk groups of patients.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brewer C., Farmer R. Self poisoning in 1984: a prediction that didn't come true. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985 Feb 2;290(6465):391–391. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6465.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buglass D., McCulloch J. W. Further suicidal behaviour: the development and validation of predictive scales. Br J Psychiatry. 1970 May;116(534):483–491. doi: 10.1192/bjp.116.534.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer S., Bagley C. Effect of psychiatric intervention in attempted suicide: a controlled study. Br Med J. 1971 Feb 6;1(5744):310–312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5744.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K. Assessment of suicide risk. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 Feb;150:145–153. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krikler D. M. Electrocardiographic diagnosis. Lancet. 1974 May 18;1(7864):974–976. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt S., Kreitman N. Trends in parasuicide and unemployment among men in Edinburgh, 1968-82. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Oct 20;289(6451):1029–1032. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6451.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. The relative effects of sex and deprivation on the risk of early death. J Public Health Med. 1992 Dec;14(4):402–407. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]