Abstract

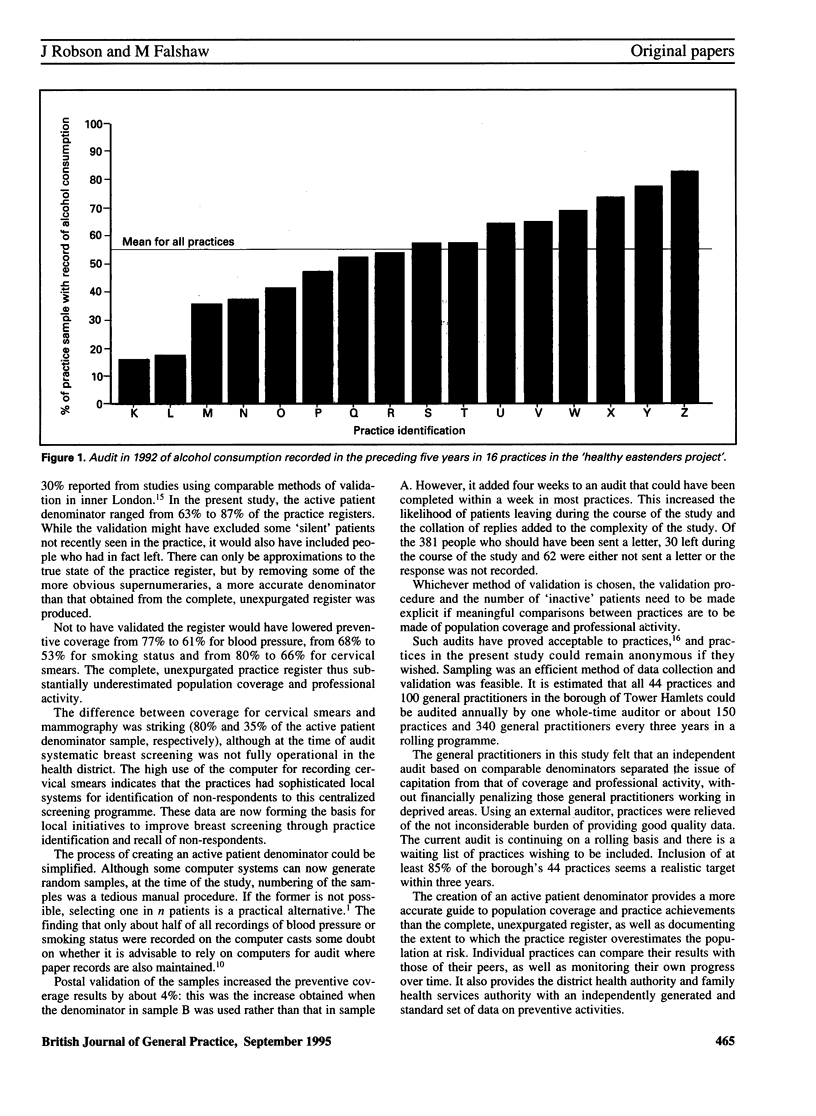

BACKGROUND. Reliable comparison of the results of audit between general practices and over time requires standard definitions of numerators and denominators. This is particularly relevant in areas of high population turnover and practice list inflation. Without simple validation to remove supernumeraries, population coverage and professional activity may be underestimated. AIM. This audit study aimed to define a standard denominator, the 'active patient' denominator, to enable comparison of professional activity and population coverage for preventive activities between general practices and over time. It also aimed to document the extent to which computers were used for recording such activities. METHOD. A random sample of people in the age group 30-64 years was drawn from the computerized general practice registers of the 16 inner London general practices that participated in the 'healthy eastenders project'. A validation procedure excluded those patients who were likely to have died or moved away, or who for administrative reasons were unable to contribute to the numerator; this allowed the creation of the active patient denominator. An audit of preventive activities with numerators drawn from both paper and computerized medical records was carried out and results were presented so that practices could compare their results with those of their peers and over time. RESULTS. Of the original sample of 2331 people, 25% (practice range 13%-37%) were excluded as a result of the validation procedure. A denominator based on the complete, unexpurgated practice register rather than the validated active patient denominator would have reduced the proportion of people with blood pressure recorded within the preceding five years from 77% to 61%, recording of smoking status from 68% to 53% and recording of cervical smears from 80% to 66%. Only 53% of the last recordings, within the preceding five years, of blood pressure and only 54% of those of smoking status were recorded on the practice computer. In contrast, 82% of recorded cervical smears were recorded on computer. CONCLUSION. The active patient denominator produces a more accurate estimate of population coverage and professional activity, both of which are underestimated by the complete, unexpurgated practice register. A standard definition of the denominator also allows comparisons to be made between practices and over time. As only half of the recordings of some preventive activities were recorded on computer, it is doubtful whether it is advisable to rely on computers for audit where paper records are also maintained.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bowling A., Jacobson B. Screening: the inadequacy of population registers. BMJ. 1989 Mar 4;298(6673):545–546. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6673.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming D. M., Lawrence M. S. Impact of audit on preventive measures. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983 Dec 17;287(6408):1852–1854. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6408.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser R. C., Clayton D. G. The accuracy of age-sex registers, practice medical records and family practitioner committee registers. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981 Jul;31(228):410–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser R. C., Gosling J. T. Information systems for general practitioners for quality assessment: I. Responses of the doctors. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985 Nov 23;291(6507):1473–1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6507.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser R. C. Patient movements and the accuracy of the age--sex register. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1982;32(243):615–622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser R. C. The reliability and validity of the age-sex register as a population denominator in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1978 May;28(190):283–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannay D. R., Maddox E. J. Missing patients on a health centre file. Community Health (Bristol) 1977 May;8(4):210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M., Coulter A., Jones L. A total audit of preventive procedures in 45 practices caring for 430,000 patients. BMJ. 1990 Jun 9;300(6738):1501–1503. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6738.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeigue P. M., Shah B., Marmot M. G. Relation of central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes prevalence and cardiovascular risk in South Asians. Lancet. 1991 Feb 16;337(8738):382–386. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91164-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle M., Hobbs R. Large computer databases in general practice. BMJ. 1991 Mar 30;302(6779):741–742. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6779.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland M. O., Middleton J., Goss B., Moore A. T. Should performance indicators in general practice relate to whole practices or to individual doctors? J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989 Nov;39(328):461–462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silman A. J. Age-sex registers as a screening tool for general practice: size of the wrong address problem. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Aug 18;289(6442):415–416. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6442.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A., Dowell T., Pollock C., Weekes T. Health promotion in general practice. Room for improvement in data collection. BMJ. 1993 Aug 7;307(6900):381–381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6900.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]