Abstract

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) affects >25% of women worldwide and often recurs after standard-of-care metronidazole (MTZ) treatment. LACTIN-V, a live biotherapeutic product (LBP) containing Lactobacillus crispatus strain CTV-05, reduced recurrent BV in a Phase 2b clinical trial, but efficacy was incomplete. We characterized microbiota and immune effects and correlates of treatment success in trial samples. By week 12, L. crispatus-dominant microbiota was achieved in 30% of LBP recipients compared to 9% of placebo (benefit ratio: 3.31; p<0.005). This effect was mostly due to CTV-05, but native L. crispatus strains were also present and increased over time. Inflammatory cytokines decreased in both arms after MTZ, but returned to baseline in placebo recipients. L. crispatus colonization was associated with pre-MTZ microbiota, baseline cytokine profiles, post-MTZ bacterial load, and clinical and behavioral variables. These findings elucidate LBP microbiota effects and identify predictors of treatment success, informing improved intervention strategies to advance women’s health.

Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis (BV), a vaginal syndrome characterized by Lactobacillus-deficient vaginal microbiota, affects 23–29% of women of reproductive age globally, with an estimated annual economic burden of $4.8 billion worldwide (Peebles et al., 2019; Workowski et al., 2021). BV symptoms include vaginal discharge, malodor, pain, and itching, leading to significant impairments in quality of life, self-esteem, and sexual function (Bilardi et al., 2013; Brusselmans et al., 2023). In addition, BV is linked to mucosal inflammation and increased risk for numerous adverse health outcomes, such as HIV acquisition, sexually transmitted infections, preterm birth, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, and cervical cancer (Anahtar et al., 2015; Atashili et al., 2008; Brusselaers et al., 2019; Gosmann et al., 2017; Hillier et al., 1988; Leitich and Kiss, 2007). While BV occurs globally, it disproportionately affects those with lower socioeconomic status and members of racial or ethnic minority groups across diverse settings (Allsworth and Peipert, 2007; Kenyon et al., 2013; Marconi et al., 2015; Peebles et al., 2019). Development of effective BV treatments is therefore a key objective to improve women’s health worldwide (Bradshaw and Sobel, 2016).

Current first-line therapy for BV consists of oral or intra-vaginal antibiotics such as metronidazole (MTZ), which target many species within the diverse anaerobic bacterial communities characteristic of BV (Bradshaw and Sobel, 2016; Workowski et al., 2021). In most cases, MTZ reduces abundance of BV-associated anaerobes and leads to emergence of bacterial communities dominated by Lactobacillus species (which are intrinsically MTZ-resistant) (Bradshaw and Brotman, 2015), but BV frequently recurs after treatment. An Australian study of women with symptomatic BV found that 58% experienced recurrent BV (rBV) within 1 year of MTZ therapy, while a US trial that enrolled women with symptomatic BV and a prior history of post-treatment recurrence found that >75–80% experienced rBV within 16 weeks of treatment (Bradshaw et al., 2006; Schwebke et al., 2021). It is hypothesized that the incomplete efficacy of MTZ often results from a failure to eradicate BV-associated bacterial communities and/or from their post-MTZ replacement with Lactobacillus species prone to reverting to BV (Bradshaw and Brotman, 2015). Studies have shown that Lactobacillus iners is associated with an increased risk of transition to BV-like states (DiGiulio et al., 2015; Munoz et al., 2021; Tamarelle et al., 2022) and with higher rates of adverse health outcomes (Colbert et al., 2023; Gosmann et al., 2017; Kindinger et al., 2017; Norenhag et al., 2020; van Houdt et al., 2018). MTZ treatment frequently results in establishment of vaginal microbiota dominated by L. iners rather than L. crispatus (Ferris et al., 2007; Joag et al., 2019; Mitchell et al., 2012; Ravel et al., 2013; Srinivasan et al., 2010; Verwijs et al., 2020), supporting the hypothesis that BV therapies which preferentially promote L. crispatus over L. iners may improve treatment outcomes and promote vaginal health (Bradshaw and Brotman, 2015; Nilsen et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2024).

New strategies to enhance L. crispatus colonization during BV treatment are in various stages of development, including vaginal microbiome transplants, adjunctive therapies that selectively inhibit L. iners and/or promote L. crispatus growth, and L. crispatus-containing live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) (Bloom et al., 2022; Chetty et al., 2025; Cohen et al., 2020; Lev-Sagie et al., 2019; Nilsen et al., 2020; Ravel et al., 2025; Yockey et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2024). The most advanced LBP in development is LACTIN-V, a vaginally-administered LBP containing the L. crispatus strain CTV-05, and the only LBP tested in large-scale clinical trials (Cohen et al., 2020; Hemmerling et al., 2009). Cohen and colleagues recently reported results of a phase 2b multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study showing that participants who received 11 weeks of intravaginal LACTIN-V after a 5-day course of intravaginal MTZ developed rBV at lower rates than placebo recipients (Cohen et al., 2020). Benefits from LACTIN-V were observed at both week 12 (approximately 1 week after completing therapy; relative risk of rBV = 0.66) and week 24 (approximately 13 weeks after completing therapy; relative risk of rBV = 0.73). However, rBV rates remained high even in the LBP arm, with 30% of recipients experiencing rBV by week 12 and 39% experiencing recurrence by week 24 in the intention-to-treat analysis. In prior reports, rBV was characterized using clinical measures, but comprehensive molecular analysis of vaginal microbiota composition and factors associated with colonization were not assessed.

Here we characterize the effects of LACTIN-V on vaginal microbiota composition and identify correlates of successful colonization by analyzing vaginal microbiota composition, bacterial strain dynamics, cytokine profiles, and demographic/behavioral parameters of LACTIN-V phase 2b trial participants (Cohen et al., 2020). We find that the reduction in rBV among LBP recipients corresponded to >3-fold higher rates of L. crispatus-dominant colonization, but only 30% of recipients achieved L. crispatus-dominant vaginal microbiota at week 12, consistent with the observed incomplete clinical efficacy. Microbiota trajectory and strain dynamics revealed CTV-05 accounted for the majority of L. crispatus colonization among LBP recipients, though endogenous strains increased over time and sometimes displaced CTV-05. We further describe the effects of LBP treatment and microbiota composition on vaginal immune markers, and show that pre-MTZ microbiota composition, baseline inflammatory cytokine profiles, post-MTZ total bacterial load, and selected clinical/behavioral variables are associated with LBP treatment success. These results show how an L. crispatus LBP alters vaginal microbiota composition to improve BV treatment efficacy while identifying factors linked to LBP success that can guide development of future therapies to promote more optimal vaginal microbiota communities and improved women’s health outcomes.

Results

Study design and participant characteristics

Women aged 18 to 45 years with BV completed five days of standard intravaginal MTZ therapy and were then randomized 2:1 to receive intravaginal LACTIN-V (Osel, Inc.) or placebo as previously described (Cohen et al., 2020). Enrollment occurred at four U.S. sites. LACTIN-V is a powder formulation containing the live L. crispatus strain CTV-05, administered via prefilled, single-use vaginal applicators at a dose of 2×109 colony-forming units (CFU). The placebo contained the same inactive ingredients without bacteria and was visually indistinguishable. BV diagnosed at the baseline “pre-MTZ” screening visit required at least three of four Amsel criteria and a Nugent score of ≥4 (Amsel et al., 1983; Nugent et al., 1991). Participants received five days of intravaginal MTZ gel within 30 days of diagnosis, and then were seen at a “post-MTZ” visit within 48 hours of completing antibiotics for randomization to LBP or placebo. The first treatment dose was clinician-administered at the post-MTZ visit, then participants self-administered doses daily for four consecutive days, followed by twice weekly dosing for 10 weeks (ending at week 11 post-randomization; Figure 1A). Clinician-collected vaginal swabs were obtained at the pre-MTZ and post-MTZ visits prior to randomization, and at weeks 4, 8, 12, and 24 post-randomization. Detailed demographic, clinical, and behavioral data showed no notable differences between arms (Cohen et al., 2020). The trial enrolled and randomized 228 participants (152 in the LBP arm and 76 in the placebo arm); samples from 213 of these participants (142 in the LBP arm and 71 in the placebo arm) were available for this analysis, representing a total of 1,156 unique study visits.

Figure 1: LACTIN-V trial design and microbiota endpoints.

A. Schematic of LACTIN-V trial study design and sampling visit timing.

B. Participants were grouped into three microbiota categories: L. crispatus-dominant colonization (≥ 50% L. crispatus relative abundance), Lactobacillus (non-crispatus)-dominant colonization (≥ 50% Lactobacillus, < 50% L. crispatus), or non-Lactobacillus-dominant (< 50% Lactobacillus) based on results of bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The Sankey diagram displays how participants transitioned between these three categories throughout the trial.

C. Microbiota composition and BV diagnosis at week 12 for each participant in the LBP and placebo treatment arms. Relative abundances of the 15 most abundant taxa are shown, with remaining taxa summed as “Other”. Participants are grouped by treatment arm into the categories defined as in Figure 1B, with BV diagnosis indicated along the top margin.

D. Total bacterial load (measured by qPCR) at each scheduled visit in each arm. Boxplots (here and in subsequent figures) represent the median (middle horizontal line), the 25th and 75th percentiles (lower and upper boundaries of boxes, respectively, “IQR”), measurements that fall within 1.5 times the IQR (whiskers), and any individual measurement outside that range (dots).

LBP Effects on L. crispatus and total Lactobacillus colonization

Bacterial microbiota composition was determined by bacterial 16S V4 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing. Four samples were excluded due to technical failures of PCR amplification and sequencing (<103 processed reads per sample). Of the remaining 1,152 samples (Table S1, Figure S1A), the median number of analyzable reads per sample was 31,177 (IQR 23,774–41,251). No significant differences in microbiota composition were observed between study arms at either the pre-MTZ or post-MTZ visits (PERMANOVA p = 0.63 and p = 0.14, respectively; Figure S1B–C, SI).

To assess microbiota impacts of LBP treatment, we defined two outcome parameters based on microbiota proportional composition: ≥50% relative abundance of L. crispatus (“L. crispatus-dominant”) and ≥50% summed relative abundance of Lactobacillus genus (“Lactobacillus-dominant”, including L. crispatus). The primary microbiota endpoint for this analysis was establishment of an L. crispatus-dominant vaginal community at week 12, the timepoint corresponding to the trial’s primary clinical endpoint (Cohen et al., 2020). Secondary microbiota endpoints were L. crispatus-dominance at week 24 and total Lactobacillus-dominance at weeks 12 or 24. Almost all participants in both treatment and placebo arms had non-Lactobacillus-dominant microbiota (<50% Lactobacillus) at the pre-MTZ screening visit, consistent with the fact that all had met criteria for clinical BV (Figure 1B). The majority in both arms transitioned to Lactobacillus-dominance at the post-MTZ visit that was largely driven by high relative abundance of L. iners (Table S2). Only one participant in each arm exhibited L. crispatus-dominant colonization at the post-MTZ visit (Figure 1B). Microbiota composition of the two arms diverged after randomization, with 30% of LBP recipients (n=37) compared to only 9% of placebo recipients (n=5) achieving L. crispatus-dominant colonization at week 12 (the primary endpoint), resulting in a benefit ratio of 3.4 (95% CI: 1.4 – 8.1; p < 0.005; Table 1, Figure 1B–C). At week 24, 35% of LBP recipients (n=39) versus just 8% of placebo recipients (n=4) achieved L. crispatus-dominant colonization, for a benefit ratio of 4.5 (95% CI: 1.7 – 11.9). The LBP did not increase rates of total Lactobacillus-dominant colonization at week 12 compared to placebo (56% and 48% of LBP and placebo recipients, respectively; benefit ratio: 1.16; 95% CI: 0.85 – 1.59), but did at week 24 (58% and 33% of LBP and placebo recipients, respectively; benefit ratio: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.15 – 2.68; Table 1, Figure 1B–C).

Table 1:

Benefit ratios for LBP microbiota effects

| Taxon | Week | Microbiota Endpoint | LACTIN-V | Placebo | Benefit Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. crispatus | Week 12 | ≥ 50% L.c. | 37 (30%) | 5 (9%) | 3.37 (1.40 – 8.11) | < 0.005 |

| < 50% L.c. | 86 (70%) | 51 (91%) | ||||

| Week 24 | ≥ 50% L.c. | 39 (35%) | 4 (8%) | 4.49 (1.69 – 11.90) | ||

| < 50% L.c. | 74 (65%) | 48 (92%) | ||||

| Lactobacillus | Week 12 | ≥ 50% Lacto | 69 (56%) | 27 (48%) | 1.16 (0.85 – 1.59) | |

| < 50% Lacto | 54 (44%) | 29 (52%) | ||||

| Week 24 | ≥ 50% Lacto | 65 (58%) | 17 (33%) | 1.76 (1.15 – 2.68) | ||

| < 50% Lacto | 48 (42%) | 35 (67%) |

Benefit Ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals were computed using Wald’s method.

We next investigated how these microbiota parameters related to the clinical diagnosis of BV by comparing clinical and microbiota results for all post-randomization visits (weeks 4 and beyond, n = 729 visits). Among the 209 visits in which participants had ≥50% L. crispatus colonization, none had concurrent clinical BV (Table S3 and Figure 1C), and among 194 visits with <50% L. crispatus but ≥50% total Lactobacillus, only 1% (n=2) had BV. However, of the 326 visits with <50% total Lactobacillus, 50% (n=164) had clinical BV (Table S3). Thus, Lactobacillus-dominance (including L. crispatus-dominance) was highly specific for the absence of BV, while non-Lactobacillus-dominance was highly sensitive but less specific for BV.

In addition to sequencing-based microbiota composition analysis, total bacterial load in vaginal swab samples was assessed via quantitative PCR (qPCR) at the post-MTZ and post-randomization visits. Median bacterial load was significantly lower and more variable at the post-MTZ visit (median 102.69 copies/swab; IQR 100.08 - 106.44) than at subsequent visits (median 107.52 copies/swab; IQR 107.09 - 107.93 for all subsequent visits), consistent with antibiotic-mediated depletion of vaginal microbiota biomass during BV treatment, followed by bacterial repopulation of the vaginal environment (Figure 1D). We assessed whether post-MTZ microbiota composition (as determined by 16S rRNA gene sequencing) was correlated with total bacterial load using a multi-table multivariate generalization of the squared Pearson correlation, the RV coefficient (Josse and Holmes, 2016; Robert and Escoufier, 1976). This analysis revealed no significant correlation between post-MTZ microbiota composition and bacterial load (RV coefficient = 0.02, p-value > 0.1).

Microbiota composition trajectories throughout the trial

To characterize microbiota trajectories with greater resolution, we summarized microbiota composition using topic mixtures (Sankaran and Holmes, 2019; Symul et al., 2023). Compared to clustering or categorizing samples into community state types (CSTs) (Ravel et al., 2011), cervicotypes (CTs) (Gosmann et al., 2017), or sub-CSTs (France et al., 2020), this method provides probabilistic (rather than binary) weightings, allowing for more accurate descriptions of sample taxonomic composition and improved characterization of longitudinal dynamics (Symul et al., 2023). In our cohort, assignment to reference CST performed poorly (median Bray-Curtis dissimilarity with assigned CSTs > 0.33, SI), especially for Prevotella-dominated samples (median BC dissimilarity > 0.5, SI), and with over 40% of samples being equally similar to two or more CSTs (SI). To identify topics, which can be interpreted as bacterial subcommunities (i.e., consortia of bacterial taxa that co-occur with each other or with other taxa), and estimate their proportions in each sample, we fitted a latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) model (a Bayesian “topic model”) (Blei et al., 2003) to the taxonomic counts. We adapted a previously described approach (Symul et al., 2023) in which topics were constrained to be fully composed of either Lactobacillus or non-Lactobacillus species. Four non-Lactobacillus topics were inferred from the data (Figure S2A, B) and we defined four Lactobacillus-dominated topics, including three exclusively composed of a single Lactobacillus species (L. crispatus, L. iners, and L. jensenii/mulieris) and one composed of a mixture of the remaining Lactobacillus species (Figure S2C). Figure 2A shows inferred composition of each non-Lactobacillus topic, while Figure 2B displays topic proportions for each participant throughout the trial.

Figure 2: Microbiota trajectories throughout the trial.

A. Proportion of each taxon (y-axis) in each non-Lactobacillus topic (x-axis) as estimated by Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) from 16S rRNA gene sequencing data. Proportions sum to one for each topic. Taxa were included if they made up at least 1% of any topic and non-Lactobacillus topics are named according to their most predominant taxon. “G. s/l”: Gardnerella swidsinskii-leopoldii. “P. amnii”: Prevotella amnii. “Ca. L. v. (BVAB1)”: Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae (BVAB1). “P. bivia”: Prevotella bivia.

B. Microbiota composition expressed as topic relative abundance (x-axis) for each participant at each scheduled visit. Results are depicted for participants with microbiota compositional data for at least three of the six visits. Results are grouped by visit (horizontal panels) and treatment arm (vertical panels), and the y-axis is ordered by microbiota composition trajectories (see SI).

C. Relative abundance of each topic (horizontal panels) in each arm (vertical panels) at each visit. Samples from the same participant are connected by a line.

D. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between each participant’s microbiota composition at the two indicated consecutive visits, calculated from 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequence variant (ASV) relative abundances. For each pair of consecutive visits, values are shown only for participants with available microbiota data from both visits.

Three non-Lactobacillus topics were highly prevalent and abundant in both arms at the pre-MTZ visit, including topics in which the predominant taxa were Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae (BVAB1), Gardnerella swidsinskii/leopoldii, and Prevotella amnii (Figure 2C and S2D). Microbiota composition shifted substantially at the post-MTZ visit (Figure 2D), where besides high L. iners relative abundance, the non-Lactobacillus topic with the highest relative abundance was the topic in which Gardnerella swindsinskii/leopoldii was predominant (Figure 2C and S2D). Another major shift in microbiota composition occurred between the post-MTZ visit and the week 4 visit, which was larger in the LBP arm (median pairwise Bray-Curtis dissimilarity: 0.81; IQR: 0.50 – 0.97) than the placebo arm (median Bray-Curtis dissimilarity: 0.58; IQR 0.41 – 0.80), driven primarily by increased L. crispatus abundance among LBP recipients (Figure 2C–D and S2D). Microbiota composition was more stable after week 4, with median Bray-Curtis dissimilarity <0.55 at week 8 and all subsequent visits, which was comparable between arms (Figure 2D). LBP recipients who achieved L. crispatus-dominant colonization had more stable microbiota than their counterparts (Figure S2E, SI).

The observation that microbiota composition became more stable after week 4 was also supported by longitudinal patterns in microbiota categories. Among 115 participants with available data from both week 4 and week 12 visits, 71% (25 of 35; 95% CI: 53%–85%) of LBP recipients who achieved ≥50% L. crispatus at week 12 also had L. crispatus-dominance at week 4 (Figure 2B, Table S4). Similarly, 71% (27 of 38; 95% CI: 54%–84%) of LBP recipients who achieved L. crispatus-dominance at week 24 also had L. crispatus-dominance at week 4 (Figure 2B, Table S5). However, early L. crispatus-dominant colonization did not guarantee persistence, as only 49% (25 of 51) and 57% (27 of 47) of LBP recipients with L. crispatus-dominance at week 4 retained it at weeks 12 and 24, respectively. By contrast, among 38 LBP recipients with non-Lactobacillus-dominant microbiota at week 4, 79% remained non-Lactobacillus dominant at week 12 compared to just 10.5% each with L. crispatus-dominance or other Lactobacillus-dominant colonization (Table S4). Thus, microbiota communities established early tended to persist and early Lactobacillus-dominance – particularly L. crispatus-dominance – was strongly linked to ongoing Lactobacillus-dominance.

Metagenomic identification of the CTV-05 strain and assessment of L. crispatus strain dynamics

The observation that LBP treatment promoted L. crispatus colonization prompted us to examine what fraction of L. crispatus observed in LBP recipients represented the CTV-05 strain versus non-LBP native strains. We used metagenomic sequencing to assess L. crispatus strain dynamics, with strain genotypes and proportions inferred using StrainFacts (Smith et al., 2022). In a separate analysis, simulations and experimental spike-in data showed that StrainFacts performs well at inferring LBP (including CTV-05) strain genotypes and proportions in samples with ≥5% overall relative abundance of L. crispatus (Shih et al., 2025). In the LACTIN-V trial samples, L. crispatus strain inference was successful in 313 samples, identifying 24 genotypically distinct strains with at least 10% fractional strain abundance in at least one sample. To determine which strain represented CTV-05, we generated a closed assembly of the CTV-05 genome, which nearly perfectly matched the StrainFacts genotype of a widely prevalent inferred strain within the metagenomic dataset (Jaccard similarity >0.999). Among 57 samples with inferred L. crispatus strain composition from placebo recipients (any visit) or from LBP recipients prior to LBP administration, StrainFacts inferred CTV-05 presence in just 5 total samples from 5 unique participants (Figure 3A). This result suggested our strain inference approach had a low false positive CTV-05 detection rate; we cannot rule out that some “false positives” represented native strains with high genotypic similarity to CTV-05. Collectively, these results support that CTV-05 detection was achieved with high accuracy in sample metagenomes.

Figure 3: L. crispatus strain dynamics among LBP recipients.

A. Sankey diagram showing dynamics of CTV-05 versus non-CTV-05 L. crispatus strain colonization among LBP recipients. Strains were inferred from shotgun metagenomic whole genome sequencing (mWGS) using StrainFacts for all samples with ≥5% total L. crispatus relative abundance as determined from 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Samples were categorized based on proportional L. crispatus strain abundance as >90% CTV-05 (“High CTV-05”), 10–90% CTV-05 (“Mixed”), <10% CTV-05 (“Low CTV-05”). Strain inference was unsuccessful for a small fraction of samples (depicted in green) due to technical failures of metagenomic sequencing.

B. Histograms showing the number (percentage) of study participants in each treatment arm with the indicated number of inferred native (non-CTV-05) L. crispatus strains detected at least once during the trial.

C. Metagenomically inferred L. crispatus strain composition throughout the trial in an example participant from whom targeted isolations were performed at weeks 8, 12, and 24. The plot depicts overall microbiota relative abundance, with non-L. crispatus species summed (gray) and inferred L. crispatus strains shown individually in red (CTV-05 strain) and blue (a native strain: “Strain 14”).

D. Example Lactobacillus MRS agar plate from bacterial isolations showing characteristic L. crispatus colony morphology.

E. Genomes of L. crispatus isolated from the week 8, 12, and 24 visits of the participant in Figure 3C identified two strains nearly identical to the metagenomically inferred strains in these samples (assessed by Jaccard similarity to StrainFacts-inferred genotypes) and dissimilar from all other inferred strains in the cohort, none of which were detected in this participant’s samples. The isolated strains included the CTV-05 strain isolated from week 8 and 12 samples (red), and native Strain 14 isolated from week 12 and 24 samples (blue; see also Figure S3A).

F. Transition plot for LBP recipients showing total L. crispatus relative abundance (determined by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, top and bottom rows) and strain category proportions (third and fourth rows) at each pair of consecutively scheduled post-randomization visits with available strain inference data or at which strain inference was not performed due to <5% total L. crispatus relative abundance. Strain categories in the third and fourth rows show proportions of observed L. crispatus representing CTV-05 versus the sum of the native strain(s) at each visit; “undetermined” refers to samples in which strain inference was not performed. Pairs including a visit in which strain inference was unsuccessful due to technical failures of metagenomic sequencing are not shown. For each pair of visits, the top three panels show L. crispatus relative abundance, visit week, and strain category at the first visit in the pair (“Visit t”) and the bottom two panels show strain category and relative abundance at the subsequent visit (“Visit t+1”). Visit pairs are grouped along the horizontal axis by strain category at Visit t and ordered within groups by CTV-05 strain proportion at Visit t+1.

G. Pie charts for each Visit t strain category from Figure 3F, summarizing subsequent L. crispatus strain category frequencies at Visit t+1.

To further characterize fidelity of the strain-tracing approach, we analyzed inference results for native L. crispatus strains, supplemented by targeted bacterial isolations and genome sequencing to experimentally test bioinformatic predictions. Most participants in whom a native strain was inferred exhibited colonization by only a single native strain at any point during the study, with a few participants colonized by two or three native strains (Figure 3B). Since StrainFacts inferences are performed blinded to whether samples are derived from the same participant (Shih et al., 2025; Smith et al., 2022), consistent detection of the same 1–3 native strains in multiple samples from the same participant additionally supported validity of the inferences. We also performed targeted bacterial isolations of L. crispatus from a subset of samples inferred to contain CTV-05, one or more native strains, or a mixture of CTV-05 and native strains. The resulting isolates were highly genotypically similar to inferred strains from the same samples, including both CTV-05 and native strains (results for an example participant shown in Figure 3C–E, with additional participants detailed in Figure S3A). These experimental results further validated our metagenomic strain inference approach.

We examined L. crispatus strain dynamics by classifying samples with inferred strain data into three categories: samples with >90% CTV-05 fractional strain abundance (“High-CTV-05”), samples with 10–90% CTV-05 (“Mixed”), and samples with <10% CTV-05 (“Low-CTV-05”; Figure 3A). These thresholds were defined based on simulations to determine parameters maximizing reliability of strain detection (Shih et al., 2025). At each post-randomization timepoint, the majority of LBP recipients with analyzable L. crispatus strains had high-CTV-05 strain abundance, but the proportion with high-CTV-05 or mixed strains decreased over time, while the proportion with high native L. crispatus strain abundance (i.e., low-CTV-05) increased (Figure 3A). At week 4, 96.1% (n=74) of LBP recipients with ≥5% L. crispatus had high-CTV-05 or mixed strains, while just 3.9% (n=3) had high native strains. However, by week 24 only 63.2% (n=31) had high-CTV-05 or mixed strains while those with high native strains increased to 36.8% (n=18). To characterize this phenomenon in greater detail, we examined CTV-05 fractional strain abundance for each pair of consecutive post-randomization visits (Figure 3F–G). Among 144 visits with high-CTV-05, two main outcomes were observed at the next visit: 68% (n=98) maintained high-CTV-05 and 26% (n=38) transitioned to <5% total L. crispatus colonization (strain composition undetermined). Among the 18 visits with high native strain abundance, 61% (n=11) retained high native strain abundance at the next visit and none transitioned to CTV-05 dominance. Interestingly, among 23 visits with mixed CTV-05/native strain composition, only one (4%) transitioned to high-CTV-05, while 39% (n=9) remained mixed and 35% (n=8) transitioned to high native strain abundance, including some transitions to high native strain abundance that occurred while participants were still receiving LACTIN-V (Figure S3B). These results show CTV-05 was frequently the sole or dominant L. crispatus strain in LBP recipients, but when native strains dominated or co-occurred with CTV-05, they often replaced CTV-05 at subsequent visits but were almost never replaced by it.

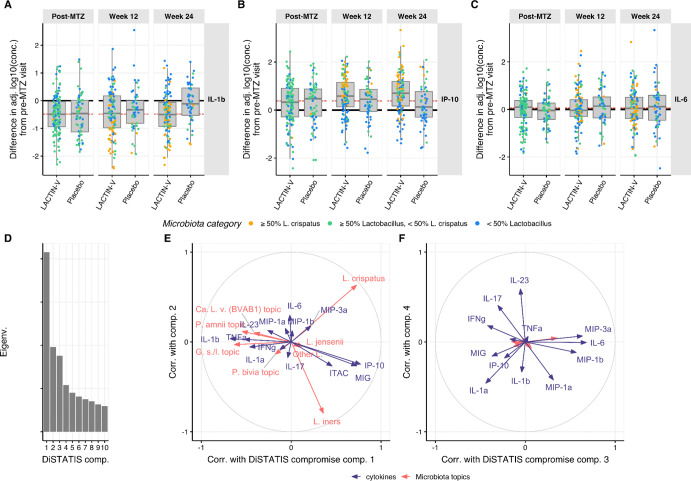

Intervention effects on vaginal inflammation

We assessed the effects of MTZ and LBP treatment on vaginal mucosal immune state and inflammation by measuring cytokine and chemokine concentrations in vaginal swab eluates using a previously described custom Luminex assay (Gosmann et al., 2017; Symul et al., 2023). Concentrations of 18 cytokines and chemokines were log-transformed for variance stabilization and imputed when outside their respective limits of quantification (Figure S4A). Concentrations of all chemokines and cytokines were strongly correlated, with the first principal component (PC1) accounting for 50% of the total variation (Figure S4B). This phenomenon suggested a size-effect (Jolicoeur and Mosimann, 1960) that we attributed to the (unmeasured) variation in biomass collection between swabs, which was addressed through PC1-subtraction (SI). Seven cytokines were excluded from analysis because a large proportion of values were outside the quantification range (Figure S4A). Mucosal immune dynamics during treatment were determined by comparing adjusted concentrations of each cytokine or chemokine from each participant’s baseline (pre-MTZ) visit with concentrations at subsequent visits.

We first examined how chemokines and cytokines with known relationships to BV and vaginal microbiota composition (Anahtar et al., 2015; Gosmann et al., 2017; Masson et al., 2019, 2014) changed during treatment. IL-1β concentrations decreased post-MTZ in both arms, while IP-10 showed the opposite pattern, consistent with previously reported pattern with BV treatment (Masson et al., 2014) (Figure 4A–B). These effects persisted in both arms through week 12, but IL-1β and IP-10 returned to pre-MTZ levels by week 24 in placebo recipients, leading to a difference of −0.39 (95% CI: −0.66 – −0.14) between adjusted concentrations in the LBP versus placebo arm for IL-1β and of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.21 – 0.79) for IP-10. By contrast, IL-6 concentrations – which have been reported not to differ between women with and without BV (Masson et al., 2014) – remained unchanged from pre-MTZ levels in both treatment arms throughout the study (Figure 4C). Sensitivity analyses examining the data prior to adjustment for size-effect via PC1-subtraction revealed findings that were qualitatively similar, but with reduced magnitude (SI).

Figure 4: Treatment effects on mucosal inflammation and relationship to microbiota composition.

A. Differences in log10-transformed, adjusted IL-1β concentrations between participants’ pre-MTZ visit and their ensuing post-MTZ, week 12, and week 24 visits (horizontal panels) in both treatment arms. Each dot represents a single visit per participant.

B. Same as Figure 4A. for IP-10 adjusted concentrations.

C. Same as Figure 4A. and 4B for IL-6 adjusted concentrations. Similar displays are available for all cytokine adjusted concentrations and non-adjusted concentrations in the SI.

D. DiSTATIS screeplot: eigenvalues (a.u.) of DiSTATIS compromise for the first 10 latent components.

E. DiSTATIS correlation circle showing the correlations between the 1st (x-axis) and 2nd (y-axis) DiSTATIS compromise latent dimension and the microbiota topic proportions (red) or cytokine transformed concentrations (blue).

F. Same as Figure 4E for DiSTATIS 3rd and 4th latent components.

The reversion of treatment-induced effects for IL-1β and IP-10 concentrations in placebo recipients by week 24 suggested an association with total Lactobacillus relative abundance, which differed between treatment arms at this visit (Table 1). We therefore examined the correlation of microbiota composition (summarized by topic proportions) with mucosal cytokine/chemokine concentrations. Their RV coefficient was 0.18 with p-value <0.005 (permutation test), indicating significant correlation. Similar RV coefficient values were obtained when repeating analysis independently for each visit (Figure S4C) except for a substantially lower correlation at the post-MTZ visit (where microbiota absolute abundance varied widely, Figure 1D), suggesting microbiota-immune correlation was not driven primarily by a participant effect. To characterize the microbiota-immune relationship in greater detail, we employed DiSTATIS (Abdi et al., 2009, 2005), a method that uses between-sample dissimilarity matrices to infer a consensus matrix across two datasets and associated latent components. Projecting microbiota topic relative abundances and transformed cytokine/chemokine concentrations onto this latent subspace using correlation circles revealed that the first latent dimension discriminated Lactobacillus-dominated samples from non-Lactobacillus-dominated samples (Figure 4D–F). Chemokines MIG (CXCL9), IP-10 (CXCL10), and ITAC (CXCL11) had high positive correlation along the first latent dimension, indicating positive covariation with Lactobacillus, while IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-1α had high negative correlations, indicating positive covariation with non-Lactobacillus species (Figure 4E). The second latent dimension discriminated L. crispatus from L. iners but most cytokines and chemokines had little or no correlation with that component, indicating minimal association of inflammatory markers with individual Lactobacillus species (Figure 4E). Most cytokines and chemokines had high correlations with the 3rd and/or 4th latent components but the microbiota topics did not, indicating a degree of immune variation that was microbiota-independent (Figure 4F). In these dimensions, IFNγ and IL-17 correlated with each other but were anti-correlated with IL-6, MIP-3α, MIP-1β, and MIP-1α. Notably, although IP-10 levels were previously reported to differ in a small subset of LACTIN-V recipients based on whether participants were highly colonized by CTV-05 versus non-CTV-05 L. crispatus strains (as measured by qPCR) (Armstrong et al., 2022), we observed no clear differences in microbiota correlation with cytokine/chemokine levels (including IP-10) in analysis that distinguished CTV-05 from other L. crispatus strains (Figure S4D–G).

Heterogeneity in LBP treatment effect based on baseline microbiota composition

We next performed exploratory post-hoc analyses to investigate whether differences in pre-MTZ microbiota composition corresponded to differences in response to the LBP (i.e., heterogeneity of treatment effect). We stratified participants by their most abundant pre-MTZ taxon (aggregated at the genus-level), identifying four groups for analysis: Lactobacillus-predominant, Gardnerella-predominant, Prevotella-predominant, and Ca. Lachnocurva vaginae (BVAB1)-predominant. LBP treatment benefit was evaluated for each group with respect to two distinct outcomes: ≥50% L. crispatus colonization (at week 12 or 24) and BV recurrence (by week 12 or 24) (Figure 5A). Heterogeneity in benefit among pre-MTZ microbiota groups (Figure 5B) was tested using an analysis of deviance comparing nested logistic regression models allowing (or not) for heterogeneity and adjusting for multiple testing by controlling for the false discovery rate (Methods, SI).

Figure 5: Heterogeneity in intervention effects with respect to pre-MTZ microbiota.

A. Participant-level observed outcomes for attainment of L. crispatus-dominance at weeks 12 and 24 (dark orange: ≥50% L. crispatus; light orange <50% L. crispatus) and BV recurrence by weeks 12 and 24 (dark blue: rBV; light blue: no rBV) for each participant with week 12 and/or week 24 data. White indicated data not available. Participants are grouped according to treatment arm and, within treatment arm, by the most predominant bacterial genus at their pre-MTZ visit (“L.” indicates Lactobacillus; “BVAB1” indicates Ca. Lachnocurva vaginae). Predominant-genus groupings lacking at least two participants in each treatment arm were excluded.

B. Pre-MTZ microbiota composition for each participant in Figure 5A (x-axis ordered and vertically aligned as in 5A), expressed as topic proportions (see Figure 2A for topic definitions).

C. Rates and associated 95% CI of L. crispatus-dominance (≥50% L. crispatus) at week 12 or 24 (horizontal panels) by pre-MTZ microbiota group in each arm. Participants are grouped based on their most predominant genus as defined in Figure 5A–B. CI are computed using Wilson’s scores due to low sample sizes in some groups.

D. Rate differences (rate in LBP arm - rate in placebo arm) and associated 95% CI (Wilson’s score method) between arms for results in Figure 5C. Color scale shows degree of benefit (defined as the difference in rates between the two arms) in achieving L. crispatus-dominance, with blue indicating benefit with LBP treatment and red indicating benefit with placebo. P-values adjusted for multiple testing (across panel 5D and 5F) using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction of the analysis of deviance test for heterogeneity in treatment effects when stratifying participants according to their most predominant genus at the pre-MTZ visit are shown in upper right corner.

E. Same as (Figure 5C), but for BV recurrence by week 12 or 24.

F. Same as (Figure 5D), but for BV recurrence by week 12 or 24. Color scale shows degree of benefit in reducing rBV, with blue indicating benefit with LBP treatment and red indicating benefit with placebo.

Analysis of the relationship between pre-MTZ microbiota groups and establishment of L. crispatus-dominant colonization suggested some groups benefitted more from LBP treatment than others (adjusted p-values = 0.11 at week 12 and 0.03 at week 24; Figure 5C, D). LACTIN-V recipients with pre-MTZ predominance of Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, or Prevotella attained higher rates of L. crispatus-dominant microbiota at both weeks 12 and 24 compared to their placebo counterparts, with modestly larger rate differences at week 24 (Figure 5D). In contrast, participants with pre-MTZ Ca. Lachnocurva vaginae (BVAB1) did not differ in L. crispatus-dominant colonization between LBP and placebo arms. Analysis of BV recurrence also showed differences in benefit from LBP treatment based on pre-MTZ microbiota (adjusted p-values <0.05 at week 12 and <0.01 at week 2; Figure 5E–F). Among LBP recipients with pre-MTZ Prevotella-predominance, BV recurred in almost all placebo recipients by week 24, compared to just over half of LBP recipients. By contrast, LBP recipients whose most prevalent taxa pre-MTZ was Ca. Lachnocurva vaginae (BVAB1) were unique in exhibiting slightly higher absolute rates of rBV than those who received placebo (Figure 5E–F). We used similar methods to perform a sensitivity analysis in which participants were grouped based on pre-MTZ CSTs (France et al., 2020) or using a model-based approach relying on topic relative abundances. Findings from this analysis were largely consistent with results of our predominant-taxon analysis above (Figure S5, SI). Together, these exploratory analyses showed that benefits of LBP treatment in achieving L. crispatus-dominance and preventing BV recurrence differed depending on pre-MTZ microbiota composition, with participants who had pre-MTZ predominance of Ca. Lachnocurva vaginae (BVAB1) exhibiting a lack of benefit compared to placebo, whereas other participants experienced more favorable responses.

Factors associated with achieving L. crispatus dominance in LBP recipients

To identify factors associated with establishing L. crispatus dominance among LBP recipients, we performed a series of multiblock partial least square discriminant analyses (MB-PLS-DA) on the longitudinal LACTIN-V arm data (Figure 6A–C, S6, S7A). Based on the observation that early L. crispatus-dominant colonization correlated with L. crispatus colonization at later visits (Table S4, S5), we analyzed factors from prior visits that associated with the participants’ microbiota category by week 4, as well as separate analyses of factors associated with microbiota category at ensuing visits. We defined three models corresponding to the different phases of the trial: the “initial phase” spanned from the post-MTZ visit to week 4, the “continuation phase” spanned from week 4 to week 12, and the “follow-up phase” spanned from week 12 to week 24 (Figure S6A). For each phase, factors of interest (i.e., explanatory variables) were grouped into 13 thematic blocks (Figure 6A, Table S6). The first block characterized participant demographics, blocks 2–4 described participant baseline vaginal ecosystem (i.e., pre-MTZ microbiota composition and diversity, pH, cytokines concentrations), blocks 5–8 quantified the vaginal ecosystem at the previous visit (e.g., at the post-MTZ visit in the initial phase, when the response is week 4 colonization status), while blocks 9–13 characterized participant sexual behavior, douching/bleeding, antibiotic use, and product adherence (Table S6). For each phase, MB-PLS-DA was used to evaluate the ability of these variables to discriminate between the following microbiota categories at each visit starting from week 4: ≥50% L. crispatus, ≥ 50% Lactobacillus but <50 % L. crispatus, or < 50% Lactobacillus (see also Figure 1B). We also used nested models to assess the additional contribution of specific blocks in discriminating colonization status (SI, Figure S6A–C).

Figure 6: Multiblock analysis of factors associated with microbiota categories in LACTIN-V recipients.

A. Multiblock partial least squared discriminant analysis (MB-PLS-DA, Figure S6A) of factors predictive of microbiota categories (≥50% L. crispatus; ≥50% Lactobacillus and <50% L. crispatus; or <50% Lactobacillus) at the indicated visits. Relative cumulative importance indices (x-axis, Methods) are shown for each thematic block of explanatory variables (y-axis, color) for the initial phase model (post-MTZ to Week 4; left panel), continuation phase model (Week 4 to 8 to 12; middle panel), and follow-up phase model (Week 12 to 24; right panel). Dots indicate point estimates and translucent horizontal bars represent bootstrapped 95% CI. Vertical lines at x = 1 show the expected value under the (null) hypothesis that all variables have the same importance. Block definitions along with the description of the variables included in each block are provided in Table S6. Horizontal dashed lines separate blocks included in the nested models (Figure S6A, SI, Methods).

B. Bi-plot for the MB-PLS-DA initial phase model (from post-MTZ to week 4). Dots represent scores (each dot is a participant) while arrows represent loadings (each arrow is an explanatory variable, see Figure S7A) for the most important variables (Methods) in the space of the 2 first latent variables. Dots (participants) are colored by their corresponding response categories (i.e., their colonization status at week 4). Perfect separation of the categories would indicate perfect prediction of colonization status at the week 4 visit. Arrows (explanatory variables) are colored by the block to which they belong to - Figure 6A and Table S6 serve as color legend.

C. Scree-plot of the first 15 eigenvalues of the model from Figure 6B. The first two latent variables (selected by cross-validation) are shown in dark gray.

D. Transformed log2-concentrations (y-axis) of two cytokines (MIG and IL-1b) whose pre-MTZ levels (left panel) were identified as associated with participants’ colonization status at week 4 (x-axis, colors) by the model (Figure 6A and S7A). Concentrations at the post-MTZ and week 4 visits are shown in the middle and right panels. Each dot is a participant, colored by the colonization status at week 4 for each panel.

In the model for the LBP arm initial phase, the most important block for discriminating week 4 colonization categories was the previous (i.e., post-MTZ) vaginal environment (Figure 6A, left panel). This block included post-MTZ total bacterial load, α-diversity, and pH. Lower values of these three factors were associated with higher chances of ≥50% L. crispatus at week 4, and were among the 5 most important variables in the model (Figure 6B–C and S7A). The next most important blocks were demographics and blocks characterizing participant pre-MTZ vaginal environment, including pre-MTZ vaginal pH, α-diversity, cytokine concentrations, and microbiota composition (as described by topic proportions, Figure 6A and S7A). Specifically, high pre-MTZ α-diversity and pH were negatively associated with L. crispatus colonization at week 4 (Figure 6B). Interestingly, pre-MTZ adjusted concentrations of the chemokine IL-1β were positively associated with achieving L. crispatus-dominance at week 4 while pre-MTZ IP-10 and MIG levels showed an opposite association (Figure 6B, 6D). Self-declared race and education were the most important demographic block variables, with white and more highly educated participants having higher rates of L. crispatus-dominance (Figure S7A). However, race and education were highly correlated in the cohort (Figure S7B) such that their individual contributions to explaining L. crispatus colonization could not be clearly distinguished. While these two demographic variables were also correlated with several pre-MTZ vaginal characteristics that also explained colonization such as pre-MTZ α-diversity (Figure S7C), they still mildly contributed to model explanatory power (Figure S6C). The remaining blocks or variables were not important for discriminating between initial phase colonization categories (Figure 6A–B, Figure S7A), possibly because variables in these blocks contributed limited information as overall adherence was high, use of antibiotics and douching was relatively rare, and some birth control options were rare in this cohort (SI). In contrast, within these blocks, factors with higher heterogeneity across participants such as bleeding and sexual activity showed greater variable importance (Figure S7A).

In the continuation phase model for the LBP arm (from week 4 to week 12), the colonization category at the previous visit was by far the most important block associated with colonization category at the following visit (Figure 6A), consistent with higher stability of microbiota composition from week 4 to 12 (Figure 2D). While no other blocks significantly improved model performance (Figure S6C), individual variables including sexual activity, bleeding, douching, and non-hormonal IUDs were all negatively associated with high-level L. crispatus colonization (Figure S7A). In the model for the LBP follow-up phase (from week 12 to week 24), the colonization category at the previous visit (i.e., week 12) was again strongly associated with the colonization category at week 24. However, in contrast to the previous phase, sexual behavior and antibiotic use only mildly contributed in explaining week 24 colonization categories (Figure 6A, right panel, Figure S6C, S7A).

Analogous analyses for placebo recipients did not show significant predictive value for either the initial phase or the follow-up phase in cross-validation (Figure S8A–C, S9). The placebo continuation phase model had modest predictive value, with microbiota category at the previous visit serving as the best predictor of microbiota category at the next visit (Figure S8A–C, S9).

Discussion

Treatment with vaginal live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) offers significant promise to improve health, but mechanisms, correlates, and strain dynamics of LBP colonization and efficacy remain incompletely understood (Bradshaw et al., 2025). We performed comprehensive analyses of samples and data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial of LACTIN-V, a single-strain L. crispatus LBP for prevention of BV recurrence (Cohen et al., 2020). We employed microbiome sequencing, strain tracing, and immunologic characterization together with multi-block analysis of biological, clinical, demographic, and behavioral parameters to investigate LBP effects and correlates of treatment success. LACTIN-V treatment resulted in L. crispatus-dominant vaginal bacterial communities in 30% and 35% of recipients at weeks 12 and 24, respectively, representing 3.4- and 4.5-fold higher rates than in placebo recipients. L. crispatus colonization among LBP recipients was substantially due to the LACTIN-V strain CTV-05, although dominance by native L. crispatus strains increased over time. Microbiota trajectory analysis showed that microbial communities established early frequently persisted. Achieving Lactobacillus-dominance – particularly L. crispatus-dominance – at early timepoints was strongly linked to persistence of Lactobacillus-dominance, while early non-Lactobacillus-dominance also tended to be maintained. In exploratory post-hoc analyses, we found that the LBP’s benefits differed based on baseline vaginal microbiota composition, and we identified specific microbial, immune, demographic, and behavioral factors associated with high-level L. crispatus colonization among LBP recipients.

To enhance resolution and power, we relied, for most of our analyses, on the observed relative abundances of species, genera, or de novo topics rather than on de novo clusters or assignment to reference community state types (CSTs). This approach is based on prior work showing that diverse vaginal microbiotas do not exhibit well-defined clusters (Lebeer et al., 2023; Symul et al., 2023) which we also observed in this cohort. We also favored taxa-based reporting to facilitate interpretation and comparison with past or future studies, noting that CST definitions remain in flux as datasets expand beyond predominantly U.S. populations.

To elucidate mechanisms by which the LBP promoted L. crispatus colonization, we investigated L. crispatus strain dynamics using both metagenomic analysis and cultivation-based strain characterization. Metagenomic strain inferences showed the CTV-05 strain accounted for the majority of L. crispatus colonization among LBP recipients, but native L. crispatus strains were also observed. Interestingly, among LBP recipients with ascertainable L. crispatus strain composition, 96.1% had CTV-05 as their dominant or co-dominant strain at week 4, but this proportion progressively declined, while the number of participants with dominance by one or more native L. crispatus strains rose from 3.9% at week 4 to 36.7% at week 24. Recipients with CTV-05 strain dominance at a given visit tended to either maintain CTV-05 dominance or exhibit substantial loss of L. crispatus at the ensuing visit. However, recipients with co-dominance of CTV-05 and native strains frequently experienced replacement of CTV-05 by the native strain at the next visit, but very rarely exhibited replacement of the native strain by CTV-05. Further research is needed to determine whether native L. crispatus strains that outcompeted CTV-05 have functional characteristics providing selective advantages and whether initial CTV-05 colonization establishes a more permissive environment for eventual transition to native L. crispatus strains.

We also examined impacts of MTZ and LBP treatment on mucosal inflammation by measuring vaginal cytokines and chemokines. Significant changes in several cytokines and chemokines were observed in participants for whom treatment successfully shifted microbiota composition to Lactobacillus-dominance, and these changes reverted in participants who shifted back to non-Lactobacillus-dominance. Most notably, inflammatory cytokines including IL-1α, IL-1ꞵ, and TNFα increased as Lactobacillus abundance decreased, whereas IP-10, MIG, and ITAC showed the opposite pattern, consistent with prior reports (Anahtar et al., 2015; Gosmann et al., 2017; Masson et al., 2019, 2014). These effects appeared primarily driven by genus-level Lactobacillus abundance rather than a particular species. A prior study examining a subset of LACTIN-V trial participants in whom strain abundance was assessed by qPCR reported that IP-10 levels were lower at week 24 in participants with CTV-05 colonization than those colonized by other L. crispatus strains (Armstrong et al., 2022), but we did not observe a similar association in our analysis of the full cohort. Treatment-induced cytokine changes persisted in the LBP arm at week 24 compared to placebo, but this was driven primarily by the LBP’s effect in promoting higher rates of Lactobacillus-dominance rather than a strain-specific effect of CTV-05.

Our post-hoc analysis of treatment outcomes showed LACTIN-V’s incomplete efficacy in achieving high-level L. crispatus colonization and preventing BV recurrence was linked to differences in pre-MTZ microbiota composition. Stratifying participants by their predominant bacterial genus at the pre-MTZ visit revealed between-group differences in achieving L. crispatus-dominance at week 24 and in preventing rBV by both weeks 12 and 24. Most prominently, these analyses showed a particular benefit from the LBP in preventing BV recurrence among participants with pre-MTZ Prevotella-predominance, whereas participants with pre-MTZ Ca. Lachnocurva vaginae (BVAB1)-predominance uniquely exhibited a trend toward higher BV recurrence rates with LBP treatment and little or no benefit from the LBP in achieving L. crispatus-dominance. The reasons for these patterns are unclear, but may reflect greater competitive ability or MTZ resistance in Ca. Lachnocurva vaginae or its co-occurring species (Alauzet et al., 2010; Aldridge et al., 2001). Since Ca. Lachnocurva vaginae remains uncultured (Fredricks et al., 2005; Holm et al., 2020), experimentally testing its antimicrobial susceptibility and ability to compete with other species is currently infeasible, but our results highlight its cultivation and phenotypic characterization as key research priorities. However, we emphasize that these results showing pre-MTZ microbiota effects on LBP efficacy are based on exploratory analyses of a relatively small study cohort, which can introduce arm imbalances through post-hoc stratification. They should therefore be regarded as hypothesis-generating observations that require replication and validation in future studies.

Our integrated multiblock analysis identified both expected and unanticipated biological, clinical, demographic, and behavioral correlates of L. crispatus-dominant colonization in LBP recipients. Low total bacterial load, low vaginal pH, and low microbiota α-diversity at the post-MTZ visit were associated with L. crispatus-dominant colonization, findings that help elucidate microbiota dynamic underlying a post hoc analysis of clinical parameters which showed that participants achieving BV cure at the post-MTZ visit had lower rates of recurrence at later timepoints (Hemmerling et al., 2024). Our analysis also showed low pre-MTZ vaginal concentrations of MIG and IP-10 and high concentrations of IL-1β were also associated with L. crispatus-dominance at week 4 – an unexpected finding given their opposite correlations with Lactobacillus abundance during concurrent visits. The explanation for this observation is unclear, but may involve a more vigorous pre-MTZ mucosal immune response helping to clear BV-associated bacteria, presence of inflammatory but MTZ- or LBP-responsive bacteria in some participants at baseline, or other mechanisms. After week 4, the strongest predictor of a participants’ microbiota category was their microbiota category at the previous timepoint, indicating that microbiota composition established early after LBP treatment best predicts subsequent outcomes. Demographic data including self-declared race and education levels were also linked to microbiota composition at week 4 and beyond, but since race and education were closely correlated and likely associated with unmeasured variables, this precluded clear mechanistic interpretation. Despite evidence for sexual activity as a significant influence on BV and vaginal microbiota composition (Vodstrcil et al., 2025), we did not identify a strong signal for sexual behavior as an explanatory variable for microbiota composition in LBP recipients. This may be because of little variation in self-reported sexual behavior throughout the trial such that effects of protected or unprotected sex may have occurred early and been obscured by one of the many factors associated with early L. crispatus colonization. It is also recognized that self-reported sexual activity in clinical trials may not be a reliable measure of actual sexual activity (Jewanraj et al., 2020; Schroder et al., 2003a, 2003b; Zenilman et al., 1995), and reporting biases or inaccuracies can decrease power to detect effects.

In summary, our detailed analysis of the vaginal microbiota effects of a single-strain L. crispatus LBP reveals patterns of microbiota composition and strain dynamics underlying the clinical effects of LACTIN-V. We identify key microbiota and host factors associated with treatment success and L. crispatus colonization. If validated, these findings could help identify patients most likely to benefit from LBP treatment and guide the discovery of novel therapeutic targets to enhance LBP efficacy and improve women’s health outcomes globally.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, samples from a few participants in the primary clinical trial were not available for microbiome and cytokine analysis (samples were unavailable from 10 of 152 originally reported participants in the LBP arm and 5 of 76 participants in the placebo arm). In addition, technical failures of 16S rRNA gene sequencing precluded microbiota compositional analysis in four additional samples, so our analysis cohort was slightly smaller than the primary trial cohort. Second, the limited size of this Phase 2b study reduced statistical power, especially for heterogeneity and between-arm L. crispatus colonization comparisons. Third, the study’s relatively infrequent sampling schedule did not permit high temporal resolution to assess microbiota and strain dynamics. Finally, although detailed data were available regarding sexual, contraceptive, hygiene, and clinical parameters, participants were surveyed on only a narrow range of environmental and sociodemographic variables, precluding detailed investigation of factors that might help explain associations with microbiota composition.

Methods

Study design and sample collection

Samples analyzed in this study were obtained as part of a previously reported phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the L. crispatus LBP LACTIN-V (Osel, Inc., Mountain View, CA) for prevention of rBV (Cohen et al., 2020). Use of samples was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board (IRB Protocol #:2020P002237) as well as the UCSF Institutional Review Board (IRB Protocol#: 19–28337). LACTIN-V is a single-strain LBP formulated as a powder containing a preservation matrix and 2×109 colony-forming units (CFU) per dose of the L. crispatus strain CTV-05, which was isolated from a human vaginal sample (Cohen et al., 2020). CTV-05 is administered using a pre-filled vaginal applicator, and was compared in the trial to a placebo formulation consisting of the preservation matrix without CTV-05. The trial was conducted at four centers within the USA and enrolled premenopausal, non-pregnant women aged 18–45 years. Eligibility criteria were previously described (Cohen et al., 2020). Briefly, potential participants attended a screening (pre-MTZ) visit at which they were determined to be eligible for the study if testing revealed presence of BV as determined by both a Nugent score of 4–10 on Gram stain of a vaginal smear (Nugent et al., 1991) and presence of at least three of four Amsel criteria (characteristic vaginal discharge, >20% clue cells on microscopy of a vaginal wet prep, vaginal fluid pH >4.5, and presence of a fishy odor upon addition of 10% potassium hydroxide to a vaginal specimen) (Amsel et al., 1983), as well as negative testing for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomonas, and urinary tract infection. Women found to be eligible based on this evaluation completed 5 days of intravaginal MTZ therapy within 30 days of their pre-MTZ visit (Figure 1A, S1A). They then returned to the trial clinic within 48 hours of completing antibiotics (post-MTZ visit) and were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either LBP or placebo after providing written informed consent. The first dose of LBP or placebo was clinician-administered at the randomization (post-MTZ) visit, then doses were vaginally self-delivered daily for the next four days, then twice weekly for ten additional weeks. In-person study visits were scheduled 4, 8, 12, and 24 weeks after randomization, at which vaginal swabs were collected and stored (details below) and clinical report forms (CRFs) were completed. In addition, two phone visits were planned at week 16 and 20 during which a subset of the clinical report forms were filled to capture information on adverse events, menstruation, concomitant medication use, and sexual behavior protected or unprotected by condoms. Participants who desired additional in-person visits were invited to present to the clinics. Swabs and CRFs were collected at these additional visits.

Clinician-collected vaginal swab samples were obtained via speculum exam at in-person study visits. Two types of swabs were collected in parallel for analysis (Cohen et al., 2020). One set of swabs was collected at all in-person visits including the pre-MTZ (screening) visit using the Starplex™ Scientific Multitrans™ Collection and Transportation System (Starplex™ Scientific S1600), which comprises a plastic-shaft Dacron™-tipped swab stored in a glass bead-containing transport medium consisting gelatin (5.0 g/L), sucrose (68.46 g/L), glutamic acid (0.70 g/L), HEPES sodium salt (3.4 g/L), modified Hank’s balanced salts (9.8 g/L), sodium bicarbonate (0.35 g/L), bovine serum albumin (10 g/L) and the antimicrobial agents vancomycin (0.1 g/L), amphotericin B (2.5 mg/L), and colistin (0.015 g/L) at a pH of 7.2–7.8. The other set of swabs was collected at the post-MTZ (randomization) visit and all subsequent visits in the ESwab® Liquid Based Collection and Transport System (Copan ESwab 480C®). Samples were stored at room temperature for 1–4 hours after collection, then frozen at −80°C.

Microbiota sequencing, bacterial isolation, and cytokine analysis was performed on samples stored using the Starplex™ system. Samples were thawed on ice, vortexed at maximum speed for 5 seconds, then the swabs were removed from the transport media and media was divided into aliquots and re-frozen at −80°C. Subsequent processing was performed as described below. Measurement of bacterial load via qPCR was performed using swabs collected via the Copan ESwab® system.

Bacterial isolations and cultivation

Bacterial isolation and cultivation was performed under anaerobic conditions at 37°C in an AS-580 anaerobic chamber (Anaerobe Systems) with an atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide, 5% hydrogen, and 90% nitrogen (Airgas, Inc.). All culture media was pre-reduced prior to use by being placed in the anaerobic chamber overnight. Bacteria were isolated and cultivated on solid media including Lactobacillus MRS agar (Hardy Diagnostics, #G117), Columbia Blood Agar (“CBA”, Hardy Diagnostics, #A16), or CDC Anaerobe Laked Sheep Blood Agar with Kanamycin and Vancomycin (“LKV”, BD BBL™ Prepared Plated Media, #221846). Known L. crispatus strains and not-yet-identified isolates obtained on Lactobacillus MRS agar were expanded by culture in liquid media consisting of Lactobacillus MRS broth (BD #288130) prepared according to manufacturer instructions. Isolates obtained on CBA agar or LKV agar were expanded in liquid media consisting of either Wilkins-Chalgren Anaerobe Broth (Thermo Scientific™ Oxoid™, #CM0643B; prepared according to manufacturer instructions) or of NYCIII broth (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) medium 1685), whichever produced better growth. NYCIII broth was prepared using a slightly modified version of the standard ATCC protocol (Bloom et al., 2022). Pre-media consisted of 4 g/L HEPES (Fisher Scientific, #BP310–500), 15 g/L proteose peptone no. 3 (BD Biosciences, #BD 211693), and 5 g/L sodium chloride in 875 ml distilled water, which was pH-adjusted to 7.3 and autoclaved on liquid protocol at 121°C for 15 minutes, then cooled and stored at 4°C. One day before use, complete NYCIII broth was prepared from the autoclaved, cooled pre-media by adding dextrose (from a stock of 3 g per 45 ml; Fisher Chemical™, #D16–500) at 7.5% v/v, yeast extract solution (Gibco, #18180–059) at 2.5% v/v, and heat-inactivated horse serum (Gibco, #26050070) at 10% v/v, then sterilized by passage through a 0.22 μm vacuum filter.

To establish a genome sequence for the CTV-05 strain, a cryopreserved pure culture of CTV-05 was obtained from Osel, Inc. The strain was streaked for isolation on Lactobacillus MRS agar and cultured for 48 hours, then a single colony was picked into Lactobacillus MRS broth and incubated for 20 hours. The broth culture was harvested by centrifugation to obtain bacterial pellets for genomic DNA extraction and sequencing.

Bacterial isolations were performed from twelve selected trial samples (see Figure 3C–E, S3A) using a modification of previously described methods (Bloom et al., 2022). Since samples had been collected into Starplex™ transport medium containing antibiotics (see above), the samples were thawed on ice, immediately diluted into pre-reduced Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (“PBS”, Millipore Sigma, #D8537) at 1:12 v/v, centrifuged for 10 minutes at 10,000 rcf, then supernatant was removed. Pellets were re-suspended in PBS and re-centrifuged with removal of supernatant two more times, then resuspended in PBS, diluted in serial 10-fold dilutions, and 100 μl aliquots from each dilution were plated evenly on MRS, LKV, and CBA agar in parallel. Plates were incubated for 7 days and multiple examples of each distinct colony morphology from each sample were picked and subcultured onto solid media of the same type as the source media, with an emphasis on colonies from MRS agar with characteristic L. crispatus morphology (e.g., Figure 3D). After sub-culture for 3–7 days, colonies of the sub-cultured bacteria were picked into MRS broth (for colonies isolated on MRS agar) or into both NYCIII broth and Wilkens-Chalgren broth in parallel and incubated for 1–4 days, depending on growth rate. The resulting liquid cultures were then cryopreserved, with aliquots of each culture centrifuged and pellets saved for genomic DNA extraction and sequencing (see below).

Nucleic acid extraction for short-read sequencing

Total nucleic acids (TNA) extraction from cervicovaginal swabs for microbiota profiling was performed via a phenol-chloroform method, which includes a previously described bead beating process to disrupt bacteria70 and modified for processing in 96-well plate format (Phenol:Chloroform:IAA, 25:24:1, pH 6.6, Invitrogen, #AM9730, which has since been discontinued; Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate 20% Solution, Fisher Scientific, #BP1311–200; EDTA, Invitrogen, #AM9260G; 2-Propanol, Sigma, #I9516–500ML; 3M Sodium Acetate, pH 5.5, Life Technologies, #AM9740). Aliquoted samples were thawed on ice, then TNA extraction was performed using 200uL of well-mixed Star media. The extracted TNA sample was eluted into 80uL of TE buffer (Promega, #V6321).

To extract bacterial genomic DNA (gDNA) for genome sequencing of cultured bacterial strains, each isolated strain was streaked on the indicated solid media and a single, clonal colony was picked into broth culture and incubated in static culture under anaerobic conditions for between 18 and 120 hours (depending on strain growth kinetics). Cultures were centrifuged and gDNA was extracted from the pellets using a plate-based protocol including a bead beating process and combining phenol-chloroform isolation (Anahtar et al., 2016) with QIAamp 96 DNA QIAcube HT kit (Qiagen, # 51331) procedures.

Bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene amplification and sequencing

Bacterial microbiota taxonomic composition in cervicovaginal samples was determined by sequencing the V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. The V4 region was amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primer set 515F/806R at 200 pM each (515F primer sequence 5’- AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGACGTACGTACGGTGTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’ and barcoded 806R primer sequence 5’-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATXXXXXXXXXXXXAGTCAGTCAGCCGGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’, in which the underlined sequences in each primer represent the regions of complementarity to 5’ and 3’ ends of the V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, respectively, and the barcode positions in the 806R primer are indicated by X; IDT), with the 806R primers barcoded for multiplexing (Bloom et al., 2022; Caporaso et al., 2011). PCR was performed in 25 μl reactions containing 1X Q5 reaction buffer (NEB, #B9027), 0.2 mM of dNTPs (NEB, #N0447), 0.2 μM of each primer, 0.5 unit of Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB, #M0491), and 2 μl of the TNA sample. PCR was performed in triplicate for each sample in the following program: 98°C for 30 seconds, followed by 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 2 minutes. The triplicate PCR reactions for each sample were combined and amplicon production and size were confirmed on an agarose gel. Negative controls with PCR-quality water (Invitrogen, #10977) as a template were amplified in parallel for each primer barcode mix and assessed in parallel by gel electrophoresis to confirm absence of contamination and non-specific amplification. PCR products were pooled, with the amount for each sample semi-quantitatively adjusted based on its gel band intensity, then purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, #28104) and quality controlled with the Qubit™ 4 Fluorometer (Invitrogen #Q33226), and TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, 4200 TapeStation). Libraries were mixed with 10% PhiX and single-end sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq using a 300-cycle v2 kit (Illumina, #MS-102–2002) employing the custom Earth Microbiome Project sequencing primers (Read 1 sequencing primer sequence: 5’-ACGTACGTACGGTGTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’; read 2 sequencing primer sequence: 5’-ACGTACGTACCCGGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’; index sequencing primer sequence: 5’- ATTAGAWACCCBDGTAGTCCGGCTGACTGACT-3’; IDT) (Caporaso et al., 2011). Negative controls for TNA extractions and PCRs were included in each sequencing library. Study samples were sequenced in a total of six libraries. Samples with read counts < 10,000 in initial libraries were re-amplified and re-pooled into subsequent libraries and data from the run producing the highest number of reads for each sample (if the sample was sequenced multiple times) were selected for subsequent analysis. Analyzable 16S rRNA gene data was generated from a total of 1152 out of 1156 available trial samples, with the remaining 4 samples failing due to technical challenges with extraction, amplification, or sequencing.

Bacterial short-read shotgun whole genome library preparation and sequencing

Shotgun metagenomic and genomic libraries were prepared following a modified protocol of Baym et. al (Baym et al., 2015), using the Nextera DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, #20034211) and KAPA HiFi Library Amplification Kit (Kapa Biosystems, #KK2602). In brief, DNA from each sample was standardized to a concentration of 1ng/mL after quantification with SYBR Green (Invitrogen, #S7653), followed by simultaneous fragmentation and sequencing adaptor incorporation by mixing 1ng of DNA (1 mL) with 1.25 ml TD buffer and 0.25 mL TDE1 provided in the Nextera kit and incubating for 9min at 55°C. Tagmented DNA fragments were amplified in PCR using the KAPA high fidelity library amplification reagents, with Illumina adaptor sequences and sample barcodes incorporated in primers. PCR products were pooled, purified with magnetic beads (MagBio Genomics #AC-60050) and paired-end sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq X with a 300-cycle kit (Psomagen, Inc.).

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequence processing and annotation

Demultiplexing of Illumina MiSeq bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequence data was performed using QIIME 1 version 1.9.188 (Caporaso et al., 2010). Mapping files created in QIIME 1 format were validated using validate_mapping_file.py, then sequences were demultiplexed with split_libraries_fastq.py using parameter store_demultiplexed_fastq and no quality filtering or trimming, and demultiplexed sequences were organized into individual fastq files using split_sequence_file_on_sample_ids.py. Sequence reads were trimmed and filtered using dada2 version 1.6.0 (Callahan et al., 2016), trimming at positions 10 (left) and 230 (right) using the filterAndTrim function with truncQ = 11, MaxEE = 2, and MaxN = 0. Sequences were then inferred, then initial taxonomy assigned using the dada2 assignTaxonomy function with the RDP training database rdp_train_set_16.fa.gz (https://www.mothur.org/wiki/RDP_reference_files). Amplicon sequence variant (ASV) taxonomic assignments were refined via extensive manual review. The resulting annotated sequences were analyzed in R using phyloseq version 1.30.0 (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013) and custom R scripts. Sequence processing and taxonomy assignment was performed blinded to information about participants’ and samples’ clinical and demographic characteristics, treatments, and trial outcomes.

Total bacterial load via qPCR

Quantification of total bacterial load via qPCR was performed and reported as part of the initial LACTIN-V clinical trial36. In brief, DNA extracted from samples stored in the Copan ESwab® system were amplified using bacterial 16S rRNA gene primers targeting total bacteria (16S ribosomal DNA, AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG, GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT, 312bp). Bacterial concentration was calculated using a standard curve based on serial dilutions of the CTV-05 strain as previously described (Cohen et al., 2020).

Assessing balance between arms at the pre- and post-MTZ visits.

Since pre-intervention (i.e., pre-MTZ or post-MTZ) microbiota composition may be associated with differential microbiota composition post-intervention, imbalances between arms could lead to biases in our primary outcome benefit ratio estimates. To assess whether significant imbalances in microbiota composition existed in this cohort, we performed a PERMANOVA analysis, as implemented in the vegan R package, to test whether the intervention arm (LBP vs placebo) explained significant variability in microbiota β-diversity, computed using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity on ASV relative abundances.

Benefit Ratios

Benefit ratios, and associated confidence intervals and p-value were computed using Wald’s method as implemented in the epitools R package (Aragon, 2004).

Identification of microbiota topics from 16S rRNA gene sequencing count data

Microbiota topics were identified using a modification of a previously described approach (Symul et al., 2023). One main difference is that here, Lactobacillus topics (i.e., topics composed exclusively of Lactobacillus species) were defined independently from non-Lactobacillus topics (i.e., topics composed exclusively of non-Lactobacillus species), which were identified by fitting a Latent Dirichlet Allocation model (Blei et al., 2003) to the non-Lactobacillus ASV counts aggregated at the species level. This was done to facilitate the interpretation of topic composition and, specifically, to allow for “pure” topics for the most prevalent Lactobacillus species in this cohort (L. crispatus, L. iners, and L. jensenii).

To determine K, the optimal number of non-Lactobacillus topics, we relied on a method called “topic alignment” (Fukuyama et al., 2023) which examines the robustness of topics across resolutions (increasing values of K) and provides diagnostics scores that facilitate the identification of spurious topics. We selected K to minimize the number of spurious topics (flagged by low coherence scores) and such that the number of paths (collection of similar topics across resolution) in the alignment presented a plateau (Fukuyama et al., 2023) (Figure S2A–B). The estimated proportions (relative abundances) of non-Lactobacillus topics in each sample ( where is the topic and is the sample) were computed by multiplying the proportions estimated by the model on non-Lactobacillus counts () by the total non-Lactobacillus proportions in each samples ( where is the observed proportion of ASV in sample and is the set of non-Lactobacillus ASVs, such that ).

Lactobacillus topics were defined as follows: Lactobacillus species which reached 50% of a microbiota composition in at least 10 samples made up their own topic, while the remaining Lactobacillus species were grouped into a single topic (“Other L.”) as their total prevalence and abundance was overall small (Figure S2C). The composition of this topic was estimated from the species average prevalences in this cohort. The estimation of proportions of Lactobacillus topics in each sample was straightforward: they were computed from the proportions of the corresponding species in each sample.

Isolate genome assemblies from short-read sequencing