Abstract

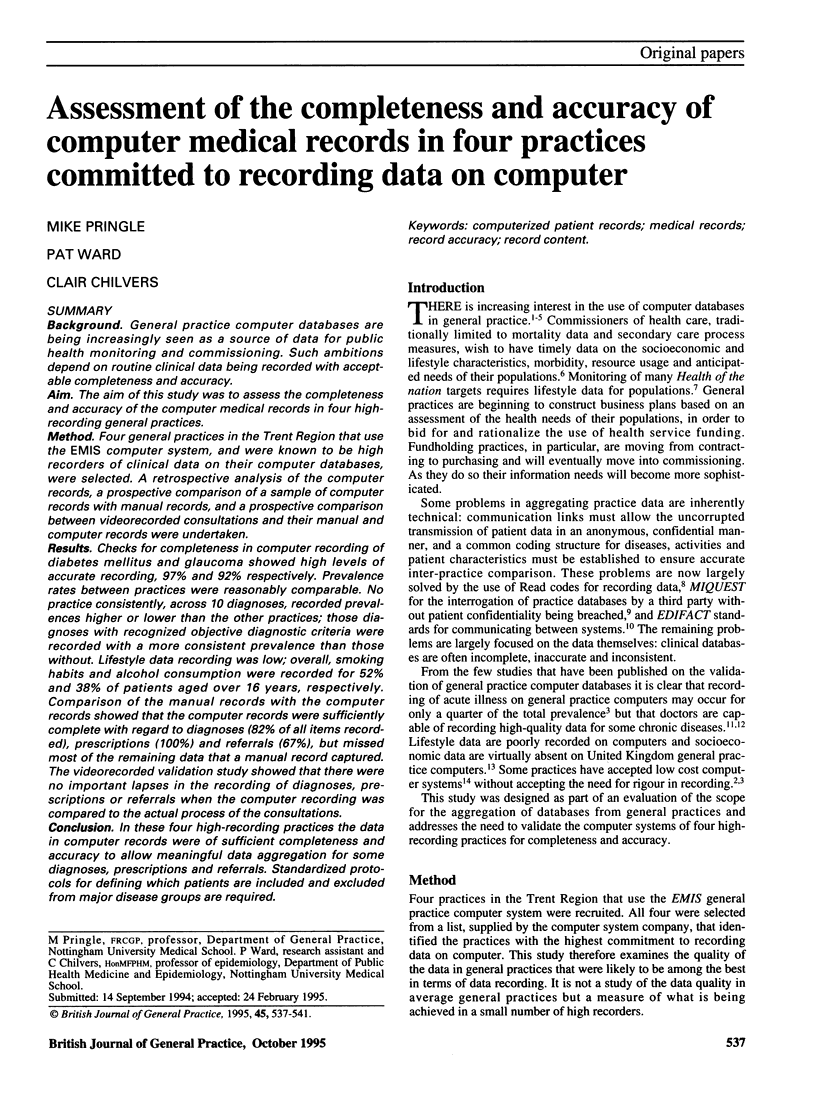

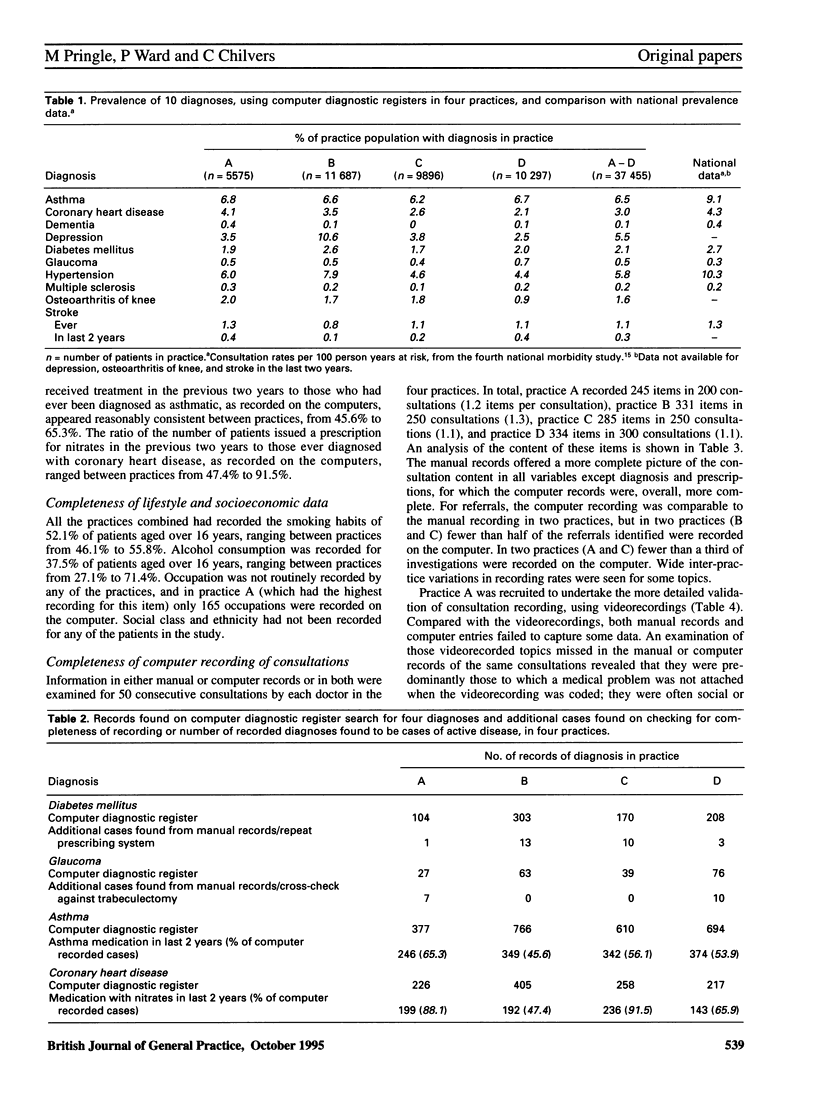

BACKGROUND. General practice computer databases are being increasingly seen as a source of data for public health monitoring and commissioning. Such ambitions depend on routine clinical data being recorded with acceptable completeness and accuracy. AIM. The aim of this study was to assess the completeness and accuracy of the computer medical records in four high-recording general practices. METHOD. Four general practices in the Trent Region that use the EMIS computer system, and were known to be high recorders of clinical data on their computer databases, were selected. A retrospective analysis of the computer records, a prospective comparison of a sample of computer records with manual records, and a prospective comparison between videorecorded consultations and their manual and computer records were undertaken. RESULTS. Checks for completeness in computer recording of diabetes mellitus and glaucoma showed high levels of accurate recording, 97% and 92% respectively. Prevalence rates between practices were reasonably comparable. No practice consistently, across 10 diagnoses, recorded prevalences higher or lower than the other practices; those diagnoses with recognized objective diagnostic criteria were recorded with a more consistent prevalence than those without. Lifestyle data recording was low; overall, smoking habits and alcohol consumption were recorded for 52% and 38% of patients aged over 16 years, respectively. Comparison of the manual records with the computer records showed that the computer records were sufficiently complete with regard to diagnoses (82% of all items recorded), prescriptions (100%) and referrals (67%), but missed most of the remaining data that a manual record captured. The videorecorded validation study showed that there were no important lapses in the recording of diagnoses, prescriptions or referrals when the computer recording was compared to the actual process of the consultations. CONCLUSION. In these four high-recording practices the data in computer records were of sufficient completeness and accuracy to allow meaningful data aggregation for some diagnoses, prescriptions and referrals. Standardized protocols for defining which patients are included and excluded from major disease groups are required.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chisholm J. The Read clinical classification. BMJ. 1990 Apr 28;300(6732):1092–1092. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6732.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland A., Mills K. A., Steele K. General practitioner records on computer--handle with care. Fam Pract. 1992 Dec;9(4):441–450. doi: 10.1093/fampra/9.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jick H., Jick S. S., Derby L. E. Validation of information recorded on general practitioner based computerised data resource in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1991 Mar 30;302(6779):766–768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6779.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N., Mant D., Jones L., Randall T. Use of computerised general practice data for population surveillance: comparative study of influenza data. BMJ. 1991 Mar 30;302(6779):763–765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6779.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPorte R. E. Global public health and the information superhighway. BMJ. 1994 Jun 25;308(6945):1651–1652. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6945.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazareth I., King M., Haines A., Rangel L., Myers S. Accuracy of diagnosis of psychosis on general practice computer system. BMJ. 1993 Jul 3;307(6895):32–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6895.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle M. Greeks bearing gifts. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Sep 26;295(6601):738–739. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6601.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle M., Hobbs R. Large computer databases in general practice. BMJ. 1991 Mar 30;302(6779):741–742. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6779.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle M., Stewart-Evans C. Does awareness of being video recorded affect doctors' consultation behaviour? Br J Gen Pract. 1990 Nov;40(340):455–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. W., Ritchie L. D., Taylor R. J., Ryan M. P., Paterson N. I., Duncan R., Brotherston K. G. General practice computing in Scotland. BMJ. 1990 Jan 20;300(6718):170–172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6718.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward P., Morton-Jones A. J., Pringle M. A., Chilvers C. E. Generating social class data in primary care. Public Health. 1994 Jul;108(4):279–287. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(94)80007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh C., Davies H. Clinical coding: completeness and accuracy when doctors take it on. BMJ. 1993 Apr 10;306(6883):972–972. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6883.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]