Abstract

A century of mining activities in the gold/arsenic mine of the Salsigne district (Southern France) has resulted in the contamination of water, soil, and wildlife with arsenic (As) as well as other metal(loid)s. The aim of this study was to detect As and 16 other metal(loid)s in non-invasive keratinized samples from companion dogs in the former mining area. In total, 49 hair samples (N = 22 from the control area in central France and N = 27 from the former Salsigne mining area) and 14 nails (N = 6 from the control area and N = 8 from the mining area) were collected from dogs. Analysis of covariance showed higher As levels in hair of dogs (p = 0.046) from the former mining area (mean ± SD 232 ± 382, median 86.8, range 17.8–1759 µg/kg dry mass) compared to those from the control area (70.9 ± 99.7, 48.3, 21.0–506 µg/kg), when sex, age, and body mass of animals were taken into account. Spatial differences in As levels in nails were not statistically confirmed although hair and nail As levels correlated significantly (r = 0.71, p = 0.004). Research has demonstrated that hair of companion dogs cohabiting humans reflect spatial differences among former mining and control groups and therefore can serve as early warning for exposure in the human population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-17622-w.

Keywords: Non-invasive sampling, Pets, Metal(loid)s pollution, Salsigne gold mine

Subject terms: Zoology, Ecology, Environmental sciences

Introduction

France has the second-highest average arsenic (As) soil levels among European countries1. Additionally, As hotspots in French topsoil have been localized, among many others, along the borders of the Massif Central and correlated with mining areas2. The former Salsigne gold (Au) mine in the Orbiel Valley was the largest in Europe and, at one point, produced 25% of the world’s As3. Mining and processing activities led to the release of both natural and anthropogenic As into the environment of the Salsigne district, occurring in particulate form (dust) and as dissolved fractions (acid mine drainage)4,5. Studies investigating soil6, sediment7, and water3,4,8 from the area have reported As levels exceeding background values. Since the mined ores are polymetallic, environmental contamination with cadmium (Cd), copper (Cu), lead (Pb), antimony (Sb), thallium (Tl), vanadium (V), and zinc (Zn), in addition to As, has also been observed3,7. Therefore, the cultivation, sale, and consumption of vegetables, as well as the use of well water in the Orbiel Valley and water from the Orbiel River and its tributaries, have been prohibited since 19976,9. However, monitoring studies focusing on the biota of the Salsigne district and their content of As and other prioritized elemental pollutants10 remain rare. Partial remediation actions at La Combe du Saut have reduced As soil levels but have also increased the exposure of wild rodents, reflected by As organ levels6. A reduction in body and organ mass among these rodents, as well as impaired cognitive function and physical modifications observed in honey bees residing in the Salsigne district has been associated with environmental As levels6,11. To the best of the author’s knowledge, these are the only documented impacts of former mine contamination on certain animal species in the Orbiel Valley. Arsenic levels in the urine of the human population from the Salsigne district exceeded the reference value in 3.8% of participants (adults and children) monitored in 199712. In the 2019 study13, only children were addressed, 30% of whom had As urine levels above 10 µg/g creatinine (the reference value proposed for the adult French population14. Some evidence suggested increased cancer mortality near the Salsigne mine15. Summary of adverse effects following long-term oral or inhalation exposure to inorganic As include dermal, cardiovascular, respiratory, reproductive, developmental, nephrotoxic, neurotoxic, mutagenic, carcinogenic, and teratogenic effects16,17.

Recent studies highlighted the sentinel role of companion animals for public health18,19. In addition, dogs and cats share similar pathological changes driven by toxic metal(loid) exposure with humans18 and have relatively long lifespan accumulating metal(loid)s and their effects over the years.

Due to the high concentration of sulfhydryl groups that bind As with high affinity in keratin, hair and nails serve as a stable, non-invasive matrix for identifying chronic exposure to environmental As and other elements during the period from hair/nails growth until it is shed16,17,20,21. Arsenic in hair/nails is predominantly in its inorganic form (around 80%) and these tissues accumulate the highest levels of As in the body17,22. By carefully addressing external contamination through washing, hair and nails were effectively utilized as indicators of chronic human exposure to As from sources such as coal burned in power plants, contaminated water, food or air16,17,23–27. Normal As levels in hair were generally set below 1000 µg/kg dry weight16. Nail As levels were reported to correlate with hair and urine levels in highly exposed populations, with concentrations exceeding 1000 µg/kg dry weight28. The hair of dogs effectively reflected dietary As exposure29–31 but showed negligible variation between field urban and control areas32. Vázquez et al.33 observed significantly elevated As levels in the hair of Argentinean dogs living in regions with groundwater contaminated by As. Hair of wild rodents and bats living in a former mine and industrial areas were shown to be a reliable non-invasive proxy for internal metal(loid) levels20,21,34,35. The nails of snowshoe hares, muskrats, and red squirrels living near the former Canadian Au Giant Mine reflected accumulation of As36,37. Similar findings were confirmed in the nails of human residents living near a former As mining area in the UK22.

Our aim was to assess the hypothesis that the hair and nails of companion dogs could serve as exposure markers for As and other metal(loid)s in the former Salsigne mining area in the Orbiel Valley, France. If validated by considering biological factors of variation (e.g., age, sex), such biomarkers could also provide early warning for exposure in the human population that closely shares the same habitat with companion animals.

Results

The age, sex, and body mass of dogs sampled in this study were comparable between the two studied areas (control vs. former Salsigne mining area in the Orbiel Valley; Table 1). Prior to sampling, dogs in the former mining area had lived there for an average of six years (ranging from 0.3 to 14 years). Fifteen of those 27 regularly swam in the local rivers of the Orbiel Valley.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of biometric data and As levels in hair and nails of dogs sampled in France with results of testing differences between as levels in control and former Salsigne mining area in the Orbiel valley.

| All | Control area | Former mining area | Difference between two areas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N, mean ± SD, median, range | F(df), p or U, p | |||

| Sex | 24 M, 25 F | 12 M, 10 F | 12 M, 15 F | |

| Age (y) | 49, 7 ± 3, 7, 0.66-16 | 22, 7 ± 4, 8, 0.75-16 | 27, 6 ± 3, 6, 0.66-14 | 0.855 (1,47), 0.360 |

| Body mass (kg) | 47, 16 ± 12, 14, 3–66 | 20, 15 ± 12, 11, 3–50 | 27, 17 ± 13, 14, 5–66 | 0.388 (1,45), 0.537 |

| As in hair (µg/kg) | 49, 160 ± 43, 58.1, 17.8–1759 | 22, 70.9 ± 99.7, 48.3, 21.0-506 | 27, 232 ± 382, 86.8, 17.8–1759 | 4.71 (1,47), 0.035 |

| As in nails (µg/kg) | 14, 471 ± 671, 136, 30.4–1952 | 6, 137 ± 87, 125, 30.4–285 | 8, 722 ± 815, 175, 84.4–1952 | 15, 0.272 |

N, number of samples; M, male; F, female; differences between to areas were tested by ANOVA or Mann-Whitney U test; F, F ratio; df, degrees of freedom; p, p value; U, Mann-Whitney U statistic.

Arsenic and other metal(loid)s in hair

A basic comparison (ANOVA) of As levels in hair showed significant differences between the two areas (p = 0.035), but no such difference was found for nail As levels (p = 0.094, Table 1). The same comparison concerning other metal(loid)s in hair investigated in this study is presented in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD, median, range) and results of testing differences between metal(loid)s levels in hair of dogs sampled in the control and former Salsigne mining area in the Orbiel valley, France

| Metal(loid) | All (N = 49) |

Control area (N = 22) | Former mining area (N = 27) | Difference between two areas (F(df), p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba (µg/kg) | 1376 ± 1824, 741, 124-11061 | 1242 ± 841, 1053, 199–3263 | 1485 ± 2354, 559, 124-11061 | 1.60 (1,47), 0.212 |

| Ca (mg/kg) | 962 ± 961, 685, 91.1–5380 | 880 ± 646, 794, 91.1–2171 | 1028 ± 1166, 669, 96.8–5380 | 0.079 (1,47), 0.779 |

| Cd (µg/kg) | 21.8 ± 48.3, 8.28, 0.876-289 | 30.4 ± 67.2, 10.2, 0.960–289 | 14.8 ± 23.6, 5.89, 0.876–91.3 | 2.12 (1,47), 0.152 |

| Co (µg/kg) | 41.7 ± 56.0, 25.3, 4.94–309 | 44.3 ± 34.2, 35.1, 4.95–156 | 39.7 ± 69.6, 14.1, 7.52–309 | 4.13 (1,47), 0.048 |

| Cu (mg/kg) | 12.2 ± 2.97, 12.0, 7.54–21.9 | 12.7 ± 2.24, 12.3, 8.62–16.4 | 11.9 ± 3.5, 11.6, 7.54–21.9 | 1.70 (1,47), 0.199 |

| Fe (mg/kg) | 60.5 ± 76.4, 35.1, 13.0-449 | 53.8 ± 37.5, 41.2, 16.0-149 | 65.9 ± 97.8, 33.0, 13.0-449 | 0.760 (1,47), 0.388 |

| Hg (µg/kg) | 190 ± 293, 123, 9.15–1911 | 298 ± 397, 196, 43.8–1911 | 103 ± 114, 39.6, 9.15–380 | 15.4 (1,47), 0.0003 |

| Mg (mg/kg) | 162 ± 173, 104, 11.2–908 | 133 ± 133, 96.6, 11.2–554 | 186 ± 200, 104, 20.2–908 | 1.32 (1,47), 0.256 |

| Mn (mg/kg) | 3.11 ± 5.50, 1.16, 0.206–26.5 | 3.38 ± 5.44, 2.07, 0.320–26.3 | 2.88 ± 5.64, 0.693, 0.206–26.5 | 3.05 (1,47), 0.087 |

| Mo (µg/kg) | 44.4 ± 31.7, 32.9, 7.69–156 | 46.0 ± 31.3, 30.7, 18.4–124 | 43.2 ± 32.6, 35.4, 7.69–156 | 0.429 (1,47), 0.516 |

| Pb (µg/kg) | 487 ± 572, 224, 40.8–2417 | 445 ± 400, 392, 85.7–1948 | 522 ± 688, 190, 40.8–2417 | 1.24 (1,47), 0.271 |

| Se (µg/kg) | 755 ± 207, 686, 482–1452 | 780 ± 203, 771, 482–1452 | 734 ± 211, 667, 527–1407 | 1.07 (1,47), 0.305 |

| Tl (µg/kg) | 3.16 ± 3.15, 2.27, 0.365–16.6 | 3.26 ± 3.62, 1.99, 0.365–16.6 | 3.08 ± 2.77, 2.34, 0.447-13.0 | 0.022 (1,47), 0.882 |

| U (µg/kg) | 5.11 ± 6.39, 2.81, 0.343–32.4 | 5.77 ± 6.99, 3.80, 0.879–32.4 | 4.58 ± 5.93, 1.76, 0.343–20.5 | 2.19 (1,47), 0.145 |

| V (µg/kg) | 138 ± 206, 74.6, 12.0-1176 | 121 ± 97, 91.2, 14.3–453 | 152 ± 266, 58.6, 12.0-1176 | 1.29 (1,47), 0.261 |

| Zn (mg/kg) | 216 ± 30, 213, 172–296 | 229 ± 24, 229, 180–268 | 205 ± 30, 197, 172–296 | 8.91 (1,47), 0.004 |

N, number of samples; differences between two areas were tested by ANOVA; F, F ratio; df, degrees of freedom; p, p value.

More complex comparison (ANCOVA) showed significant differences among control and former mining area for As (p = 0.046), Hg (p = 0.002), and Zn (p = 0.011) in hair of companion dogs, when sex, body mass, and age of animals were taken into account as covariates (Table 3). Hair Hg and Zn were higher in the control group of dogs, while higher As was found in hair of dogs inhabiting former mining area. Proposed models explained 7%, 25% and 24% of variation in hair As, Hg, and Zn levels, respectively.

Table 3.

Results of analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) used to test influence of group (control vs. former Salsigne mining area in the Orbiel Valley) on hair levels of metal(loid)s taking into account the age, sex and body mass of dogs sampled in France.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable/Covariate | F(df) | p | R2adj | β | ω2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | Model | 1.84 (4,42) | 0.139 | 0.068 | ||

| Group (C) | 4.23 (1) | 0.046 | − 0.041 | 0.064 | ||

| Age | 1.36 (1) | 0.249 | − 0.007 | 0.007 | ||

| Sex (M) | 0.252 (1) | 0.618 | 0.010 | − 0.015 | ||

| Body mass | 1.28 (1) | 0.265 | − 0.002 | 0.005 | ||

| Ca | Model | 1.71 (4,42) | 0.165 | 0.058 | ||

| Group (C) | 0.25 (1) | 0.875 | 0.042 | − 0.020 | ||

| Age | 0.939 (1) | 0.338 | − 0.072 | − 0.001 | ||

| Sex (M) | 0.615 (1) | 0.437 | 0.206 | − 0.008 | ||

| Body mass | 4.64 (1) | 0.037 | 0.045 | 0.073 | ||

| Cu | Model | 3.41 (4,42) | 0.017 | 0.173 | ||

| Group (C) | 0.648 (1) | 0.425 | 0.020 | − 0.006 | ||

| Age | 0.063 (1) | 0.803 | 0.002 | − 0.017 | ||

| Sex (M) | 0.056 (1) | 0.815 | 0.006 | − 0.017 | ||

| Body mass | 12.1 (1) | 0.001 | − 0.007 | 0.196 | ||

| Hg | Model | 4.85 (4,42) | 0.003 | 0.251 | ||

| Group (C) | 11.3 (1) | 0.002 | 0.497 | 0.166 | ||

| Age | 0.332 (1) | 0.567 | − 0.024 | − 0.011 | ||

| Sex (M) | 0.182 (1) | 0.672 | 0.062 | − 0.013 | ||

| Body mass | 5.31 (1) | 0.026 | − 0.027 | 0.069 | ||

| Mg | Model | 2.39 (4,42) | 0.066 | 0.108 | ||

| Group (C) | 0.416 (1) | 0.522 | − 0.104 | − 0.011 | ||

| Age | 0.517 (1) | 0.476 | − 0.033 | − 0.009 | ||

| Sex (M) | 0.004 (1) | 0.985 | − 0.003 | − 0.019 | ||

| Body mass | 8.00 (1) | 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.133 | ||

| Tl | Model | 3.73 (4,42) | 0.011 | 0.192 | ||

| Group (C) | 0.426 (1) | 0.517 | 0.079 | − 0.010 | ||

| Age | 6.64 (1) | 0.014 | − 0.088 | 0.097 | ||

| Sex (M) | 0.937 (1) | 0.339 | 0.116 | − 0.001 | ||

| Body mass | 5.91 (1) | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.085 | ||

| Zn | Model | 4.67 (4,42) | 0.003 | 0.242 | ||

| Group (C) | 7.13 (1) | 0.011 | 10.4 | 0.099 | ||

| Age | 0.222 (1) | 0.640 | 0.518 | − 0.013 | ||

| Sex (M) | 0.705 (1) | 0.406 | − 3.26 | − 0.005 | ||

| Body mass | 8.33 (1) | 0.006 | − 0.886 | 0.119 | ||

Only results of metal(loid)s showing statistical significance for any of the tested independent variable/covariate were shown here; group 1-C, control area; group 2-former mining area; sex 1- M, male; sex 2- F, female; F, F ratio; p, p value; df, degrees of freedom; R2adj, adjusted R squared; β, estimate; ω2, omega squared effect size; all metal(loid)s were transformed (Box-Cox), except Zn, but this step conserved the direction of studied associations shown by sign next to estimate.

Sex showed negligible influence on metal(loid) levels, age was important predictor just for hair Tl variation (negative association, p = 0.014), while dogs’ mass showed positive association with hair Ca (p = 0.037), Mg (p = 0.007), and Tl (p = 0.019), but negative association with Cu (p = 0.001), Hg (p = 0.026), and Zn (p = 0.006) (Table 3).

Habit of swimming in the streams and rivers of the Orbiel Valley was shown by means of ANCOVA to significantly influence Ba, Ca, Co, Fe, Mg, Mn, Se, Tl, and U hair levels when age, sex and body mass of dogs from the former mining area were taken into account as covariates (Supplementary Table S1, ESM1). All mentioned metal(loid)s were higher in hair of dogs which regularly swam compared to those which had no such habit.

Hair As levels in dogs, as reported in the literature, are summarized in Supplementary Table S2 (ESM1).

Arsenic and other metal(loid)s in nails

Small number of collected nail samples disabled multivariate testing of factors influencing metal(loid) levels. Univariate testing showed higher nail Cu levels in dogs from former mining area compared to control area (p = 0.017, Table 4), and higher nail Se in male than female dogs (U = 5, p = 0.040). Age was negatively associated with As (r=-0.65, r2 = 0.37, F(1,12) = 8.60, p = 0.013), Hg (r=-0.56, r2 = 0.26, F(1,12) = 5.51, p = 0.037, and V nail levels (r=-0.54, r2 = 0.23, F(1,12) = 4.84, p = 0.048), while positive association was found with nail Mo levels (r = 0.59, r2 = 0.29, F(1,12) = 6.33, p = 0.027).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD, median, range) and results of testing differences between metal(loid)s levels in nails of dogs sampled in the control and former Salsigne mining area in the Orbiel valley, france.

| Metal(loid) | All (N = 14) |

Control area (N = 6) | Former mining area (N = 8) | Difference between two areas (U, p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba (µg/kg) | 3874 ± 3841, 2362, 460-12504 | 1981 ± 1190, 1716, 460–3779 | 5294 ± 4583, 3216, 1115–12,504 | 13, 0.175 |

| Ca (mg/kg) | 1040 ± 368, 929, 651–1948 | 1123 ± 460, 1028, 667–1948 | 978 ± 301, 905, 651–1535 | 29, 0.561 |

| Cd (µg/kg) | 6.70 ± 4.95, 5.78, 1.16–14.3 | 5.98 ± 5.89, 2.42, 1.68–14.3 | 7.24 ± 4.48, 7.21, 1.16–14.3 | 21, 0.747 |

| Co (µg/kg) | 67.1 ± 47.5, 50.8, 13.8–173 | 60.2 ± 48.4, 43.9, 13.8–150 | 72.3 ± 49.4, 63.8, 21.7–173 | 18, 0.478 |

| Cu (mg/kg) | 7.32 ± 2.47, 7.10, 3.07–11.5 | 5.41 ± 1.68, 5.87, 3.07–7.11 | 8.76 ± 1.96, 9.19, 5.01–11.5 | 5, 0.017 |

| Fe (mg/kg) | 213 ± 154, 169, 36.9–598 | 169 ± 133, 121, 36.9–413 | 245 ± 169, 216, 75.4–598 | 17, 0.401 |

| Hg (µg/kg) | 91.1 ± 63.8, 76.4, 25.4–226 | 53.8 ± 23.1, 50.5, 28.1–79.6 | 119 ± 71, 108, 25.5–226 | 11, 0.107 |

| Mg (mg/kg) | 157 ± 34, 151, 120–251 | 150 ± 16, 151, 120–167 | 162 ± 43, 150, 123–251 | 24, 1.00 |

| Mn (mg/kg) | 3.62 ± 2.27, 3.13, 0.787–8.25 | 3.03 ± 1.78, 2.79, 0.787–6.11 | 4.06 ± 2.61, 3.43, 1.02–8.25 | 19, 0.561 |

| Mo (µg/kg) | 48.0 ± 41.5, 33.9, 16.7–166 | 48.2 ± 32.3, 35.3, 18.7–97.5 | 47.8 ± 49.5, 32.6, 16.7–166 | 30, 0.478 |

| Pb (µg/kg) | 771 ± 677, 630, 79.8–2711 | 514 ± 327, 491, 79.8–1057 | 963 ± 822, 799, 98.1–2711 | 13, 0.175 |

| Se (µg/kg) | 664 ± 249, 535, 345–1062 | 719 ± 310, 733, 345–1062 | 622 ± 205, 523, 500–1043 | 28, 0.651 |

| Tl (µg/kg) | 5.78 ± 2.97, 4.91, 1.83–12.4 | 5.82 ± 3.06, 5.11, 1.83-10.0 | 5.75 ± 3.11, 4.91, 1.97–12.4 | 24, 0.948 |

| U (µg/kg) | 14.0 ± 10.6, 9.92, 3.29–36.8 | 14.0 ± 11.9, 8.41, 3.29–30.5 | 14.0 ± 10.3, 11.0, 3.82–36.8 | 20, 0.651 |

| V (µg/kg) | 483 ± 390, 384, 70.3–1518 | 343 ± 290, 232, 70.3–870 | 589 ± 438, 506, 176–1518 | 16, 0.333 |

| Zn (mg/kg) | 210 ± 47, 194, 121–284 | 189 ± 43, 187, 121–239 | 226 ± 47, 222, 170–284 | 14, 0.220 |

N, number of samples; differences between two areas were tested by Mann-Whitney U test; U- Mann-Whitney U statistic, p, p value.

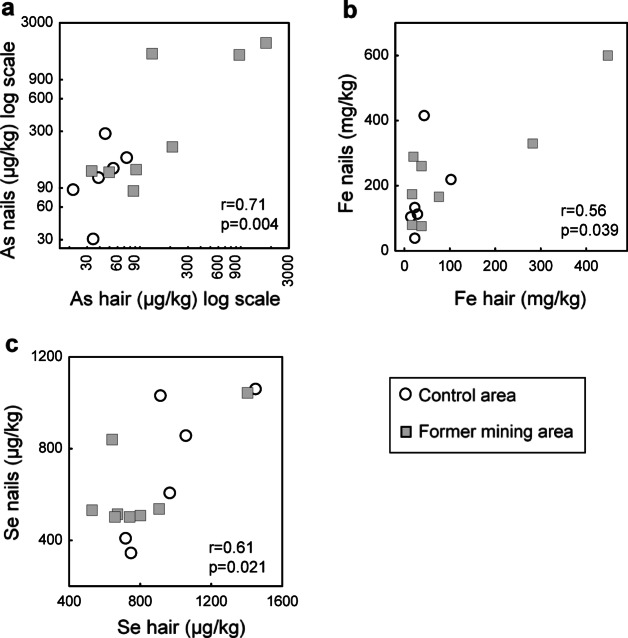

Significant associations of As (r = 0.71), Fe (r = 0.56), and Se levels (r = 0.61) between two matrices (hair vs. nail) are presented in Fig. 1. Literature data on As levels in dog nails are unavailable, therefore, we reported results from wild animals and humans residing in former mining areas (Table S3, ESM1).

Fig. 1.

Arsenic (a), Fe (b), and Se (c) levels in hair in relation to their respective levels in nails of dogs (N = 14) sampled in the control (white circles) and former Salsigne mining area (grey squares) in the Orbiel Valley, France. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) and p-value are indicated in the bottom right corner.

Discussion

The hypothesis that companion dogs’ hair and nails would show higher exposure near the former Au/As Salsigne mine than in the control area, was supported only for hair. Nails, however, failed to corroborate the same results observed in hair, although hair and nail As levels were moderately associated. These results suggest a higher chronic As exposure in companion dogs residing in the former Salsigne mining area compared to dogs from the control group.

Once in the organism, both the more toxic inorganic arsenicals and the less toxic organic arsenicals are absorbed from the intestines at high percentages; however, more than 75% is rapidly excreted in urine. The remaining As is generally distributed to all tissues in the organism, with a special affinity for keratinized tissues (e.g., hair, nails, skin), which is considered one of the detoxification pathways alongside demethylation. Consequently, hair and nails were considered a reliable and non-invasive biomarkers of past chronic As exposure from environmental compartments16,17.

Arsenic and other metal(loid)s in hair

Arsenic levels measured in the hair of all but one companion dog in this study were below 1000 µg/kg, a threshold considered normal for human hair16. The exception was a dog living in a former mining area, sharing a household with another dog that had the second-highest measured As hair level (1759 µg/kg and 961 µg/kg, respectively). Medical history of those two dogs revealed no signs of chronic conditions. Notably, As levels in the hair of dogs from the same households (e.g., E1, E2, E3, and E4; E10 and E11; E13 and E14; E16, E17, and E18; C10 and C11; C19 and C20; Supplementary Tables S4 and S5, ESM1) showed similar levels in both the exposed and control groups. Among dogs from Salsigne district, several were from the same neighborhood in Conques-sur-Orbiel and exhibited the highest As concentrations in both hair and nails. This may be at least partly attributed to the 2018 floods, which likely deposited contaminated sediments in their immediate living environment.

Dogs from Salsigne area could have been exposed to As predominantly through the ingestion of contaminated food but also through the ingestion of soil and water, as well as the inhalation of dust, similar to human population in mining areas38. Since air quality in the Salsigne district was assessed in 2022 as good and in the range of EU standards5, we considered this source of exposure to As as minor but still possible contributor. Majority of dogs from Salsigne area drank tap water, while six out of 27 dogs might have additional As exposure due to usage of well or river water downstream from mining area, which was reported to be contaminated with As3,4. Tap water for inhabitants of the Salsigne district comes from the source located northeast of the Orbiel Valley. Regular measurements of As in tap water in Conques-sur-Orbiel in 2024 revealed values (5–6 µg/L39), below the recommended limit for drinking water (10 µg/L40). All but two dogs from this study ate predominantly dry commercial dog food (kibble), which often contains a large portion of rice as the major carbohydrate source41. Rice is an important source of inorganic As for consumers right after fish and seafood17. Recent study involving dogs (N = 7) eating rice-rich kibbles (> 80%) confirmed higher As hair levels than in the dogs on a raw diet (N = 9)31. In a larger study (N = 50) with higher rice variability among kibbles fed to dogs, hair As failed to reflect differences in As exposure between dry and wet/mixed diets, as blood did30.

Dogs from both groups in this study were generally fed a kibble diet with varying and undefined ingredient ratios, occasionally supplemented with wet dog food and human food. Two dogs from the Salsigne district that were fed exclusively human diet had hair As levels (64.3 and 58.1 µg/kg) below the median of this mining area group (86.8 µg/kg). Considering all available facts, and with a reasonable insecurity due to lack of data on metal(loid) concentrations in food, it is not possible to reliably rank exposure sources or identify predominant contributor to the elevated As levels in dogs from the former mining area relative to the control group. Other exposure pathways might include exposure to contaminated soil. In children residing former Au mining areas in Victoria, Australia, toenail As levels were associated with soil As levels42–44. In general, children have higher level of nail As than adults due to more intensive contact with soil and dust through hand-to-mouth behavior43. Dogs share this exposure pathway with children due to digging and grooming behavior, thereby ingesting soil particles45. It is important to emphasize that repetitive licking behaviors directed toward the self or nearby objects, arising from underlying medical or behavioral conditions46, may lead to increased exposure to environmental metal(loid)s. Though uncommon46, such over-grooming can induce measurable variability in metal(loid) burdens even among cohabiting dogs. Besides mining-related pollution, As in the soil of Salsigne district could also stem from the use of arsenic-based pesticides in this historic viticulture region until 2001, when sodium arsenite was banned in France.

Dogs from the former mining area had three times higher average As level in their hair compared to those from the control group. The highest hair As in the control group (506 µg/kg) was seven times greater than the group’s mean. According to the owner’s report, this dog spent its summer holidays in an old mining region in France (Lozère department) and swam in the Tarn River, which may have contributed to higher environmental As exposure compared to other dogs in the control group. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed dogs that regularly swam in streams and rivers of the Salsigne district but found no significant difference in As levels compared to dogs from the same area that did not engage in this activity. In humans, absorption of As through skin and cutaneous barrier was considered negligible16. On the other hand, human hair resulted with higher As levels in individuals bathing in As rich water compared to those drinking water with high As, although their urine levels were similar47. However, hair analysis in this study revealed significantly higher levels of several other metal(loid)s (Ba, Ca, Co, Fe, Mg, Mn, Se, Tl, and U) in 15 dogs with a swimming habit from the Salsigne district. The rationale for these results is unclear. The higher affinity of hair for binding and accumulation of As and Hg compared to other metal(loid)s makes hair a sensitive biomarker of exposure to these metal(loid)s. Therefore, interpreting hair metal(loid) level, except for As and Hg, carries additional uncertainties, as some of the listed elements are homeostatically regulated essential elements (e.g., Ca, Fe, Mn, etc.), while others are ubiquitous in the environment (e.g., Ba, Pb, U, etc.)47. Due to the small sample size, further analysis to identify potential biological confounding factors was not possible, but these findings highlighted the need for future studies. Due to growing usage of hair and fur in monitoring studies including cofactor analyses30,48, and site-specific co-exposure to toxic elements from Salsigne mine, we found of great importance to report multielemental content of dogs’ hair to set up a baseline levels for the respective areas.

Zinc is an essential, homeostatically regulated element, with concentrations in hair and nails influenced by exposure pathways and nutritional status25. In contrast, mercury (Hg) is a toxic element that readily accumulates in keratinized tissues following exposure through contaminated food, water, soil, or air. It remains unclear which of these factors predominantly influenced the elevated Zn and Hg hair levels observed in the control group compared to dogs from Salsigne area.

As some authors mentioned earlier, hair metal(loid) interpretation in dogs is further complicated by diverse between-individual hair growth rates30,49, in addition to biological factors of age, sex and body condition, or residence area31–33,38,47. Modelling listed cofactors with As hair levels revealed nonsignificant influence of age, sex and body mass of dogs, which was in accordance to reports for Finish dogs30,31, but in contrast to Los Alamos dogs from Argentina (higher As in females33), urban Sydney dogs (higher As in older dogs32), and human residents of former mining area (higher As in males and older people38).

Both groups of dogs in this study exhibited similar As levels as dogs’ hair reported in studies from Sydney, Australia32, Slovakia50, and Finland30,31,51. However, dogs from Buenos Aires area in Argentina, known for naturally high groundwater As, had up to 100 times higher hair As33. Also, two to five times higher means were reported for dogs living in Campania, Italy52 compared to dogs from Salsigne area in France.

Hair levels of essential Cu, Mn, and Zn in dogs from this study were in the range of adequate values defined for dogs by Puls (20–50 mg Cu/kg, 0.5–22 mg Mn/kg, 150–250 mg Zn/kg53). The exception was the range of Fe values in French dogs (13.0-449 mg/kg), which crossed the adequate range of values set for dogs (75–260 mg/kg). Levels of toxic Cd and Pb measured here were in line with normal levels for dogs (100–900 µg Cd/kg, 880 µg Pb/kg53. The normal/adequate range of Mo and Se hair levels has not been defined for dogs but according to available levels defined for domestic animals (cattle/horse; 100–2000 µg Mo/kg, 500–3000 µg Se/kg), we can confirm that levels measured in French dogs fall within the reference range53. In addition, none of the dogs’ hair from this study crossed the normal levels of Hg set for cats (< 8000 µg Hg/kg53.

Arsenic and other metal(loid)s in nails

In contrast to hair levels, As in nails did not significantly differ between dogs from the Salsigne district and the control area, although levels were three to seven times higher in the former mining area of Salsigne. The low sample number and high data dispersion contributed to this result. Possible sources of intraindividual variation include age, sex, frequency of outdoor activities that wear down nails, and paw position of nails. These factors influence nail growth rates54–56 thereby affecting metal(loid) levels in nails. To the best of our knowledge, there are no available data for As baseline values in nails of dogs. However, nails of wild mammals used for monitoring As and Cd contamination of the Giant mine, former Au mine in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada reflected well chronic exposure of snowshoe hares, muskrats and red squirrels to As but not Cd36,37. Also, human nails showed differences in As levels between former As mine area in UK and control area22. In this study, only Cu nail levels showed statistical differences between the mining and control areas; however, we suggest that physiological processes, rather than environmental contamination with Cu in the Salsigne area, are the likely cause.

Male and female dogs studied here had similar As nail levels as was reported for humans residing in the former mining areas43,57. Negative correlation of As levels in nails with age of dogs from this study contradicts observations of positive association57 and absence of association with age43 in humans exposed to As in mining areas. Among rare studies that monitored biological samples to assess exposure in humans/animals residing in the former mine sites, just few included multielemental report of nails58 or studied influence of biological factors (age, sex, body mass) on measured metal(loid) levels43,57. Therefore, results gained in this study for metal(loid)s other than As lack source of data for comparison. Taking into account interspecies differences, As levels in nails of French dogs ranged similar as in wild mammals from Canadian Giant mine36,37, and humans from Australian Au mine43 and Portuguese mine area58. On the other hand, nails from adults and children residing in the Devon Great Consols As mine, UK22, Iron King Mine, Arizona, USA42 and Mangalur Au mine, India57 had higher mean and maximum As levels than measured in dogs from this study. Essential Se and Mn were comparable in dogs from France and humans living near or being occupationally exposed in Panasqueira Mine, Portugal, while Cd and Pb nail levels were up to 10 times lower in dogs from French Salsigne district58.

Two dogs from the Salsigne district, which had the highest As nail levels exceeding 1000 µg/kg, also had the highest hair levels. Strong correlation of As levels between these two keratinized matrices found in dogs is in accordance with previous reports from human studies57,58. Similar accumulation in both hair and nails of the same dogs was found also for Se and Fe. Although we found a strong correlation between the aforementioned hair and nail metal(loid) levels, these two matrices differ in growth rate (faster in hair) and shedding cycles56. Consequently, metal(loid) levels in nails reflect a longer timeframe of exposure compared to those in hair. Both in dogs from this study and reports addressing human exposure to As, nail levels were higher than hair levels23–25. In the human population, As nail content exceeding the threshold of 1000 µg/kg was considered indicative of high exposure to As28.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide evidence of higher As levels in the hair of companion dogs residing near the former Au/As mine in the Salsigne district, France, compared to those in the control area. In general, higher As levels in hair were accompanied by increased nail levels. These findings contribute to the very limited dataset of biological samples reflecting chronic exposure to As, as well as other toxicologically relevant metal(loid)s, in an area affected by mining legacy. Dogs with the highest As levels in keratinized tissues showed no evidences of chronic condition according to their medical history thus we can assume that present As levels, although above threshold level, do not cause notable adverse health effects. Non-invasiveness of hair and nails sampling and ability of these tissues to reflect spatial differences in exposure to As offers promising tool for future biomonitoring research in the respective area but also sites with mining-related metal(loid) contamination globally.

This study has several limitations, including a relatively small sample size and a limited number of replicates. To draw more robust conclusions and validate the findings of this small-scale investigation, future research should include a larger number of individuals sampled for both hair and nails. Additionally, incorporating dietary analyses and collecting environmental samples (e.g., soil and water) would provide further insight into potential sources of metal(loid) exposure originating from the former Salsigne mining district and other areas affected by a legacy of anthropogenic pollution.

Materials and methods

Study area

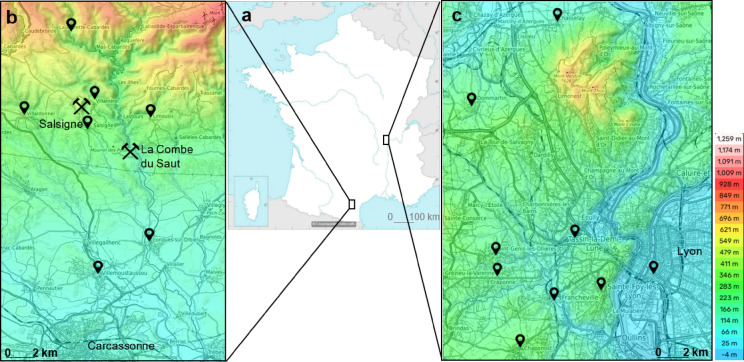

The study included dogs residing in a former As and Au mining area within the Orbiel Valley (southern France), up to 10 km in diameter from the Salsigne mine, as well as dogs from a control area in central France (W from Lyon; Fig. 2). The control area was selected based on the condition that it avoids natural As geochemical deposits or anthropogenic pollution, as confirmed by the governmental inventory of polluted soils and historical industrial areas59,60.

Fig. 2.

Map of sampling areas in France, Europe (a): the former Salsigne mining area in the Orbiel Valley (b), and the control area near Lyon in France (c). Black pointers denote locations where sampled dogs live. Hammer and pick symbol denote Salsigne and La Combe du Saut sites of former ore processing, tailing dams and waste storages in the Orbiel Valley (b). Maps adjusted using the Encylopaedia Universalis under CC BY-NC license and topographic map of France (https://topographic-map.com).

The Orbiel Valley is located on the southern slopes of the Montagne Noire, the southernmost part of Massif Central mountain range, where the Orbiel River originates. The Valley experiences a continental climate, influenced by both Mediterranean and oceanic systems, resulting in high annual rainfall (900 mm), mild average temperatures (13 °C), frequent winds (over 300 days per year), and flash floods7. The valley’s lithology is highly variable, with sulphide mineral accumulations primarily containing iron, copper, gold, arsenic, and bismuth7,61. Arsenic commonly occurs in gold-bearing minerals, so the processing of gold has led to the disposal of large quantities of As-containing waste62 near the Salsigne mine since 18923. Consequently, the area naturally has elevated As levels in the soil, sediment, surface water, and groundwater, which were further exacerbated by mining and processing activities, as well as the storage of waste rock and tailings, for over a century until the mine’s closure in 20043,4,6,7,62. Several millions tons of waste were stored with variable safety measures regarding the leaching of toxic elements into the environment at multiple waste storage sites5. At the location called La Combe du Saut, southeast from Salsigne mine, various remediation actions have resulted in a mosaic of contaminated and rehabilitated zones6. Around 5000 inhabitants live in the Salsigne district today, mostly in small towns (population up to 2575 in Conques-sur-Orbiel63), with the largest city, Carcassonne (population of 4621863), located further south at the confluence of the Orbiel to Aude rivers.

Sample collection

Twenty-two companion dogs from the control area (Supplementary Table S4, ESM1) and 27 dogs from former Salsigne mining area (Supplementary Table S5, ESM1) were sampled for hair in collaboration with local veterinarians and dog groomers in 2023. Of these, 14 (six from the control area and eight from former mining area) were additionally sampled for nails. Up to 10 g of unwashed hair (including both guard hair and underfur) was cut from the neck or shoulder region known for the fastest hair growth49 as close to the skin as possible, using stainless steel scissors. Nails were trimmed with stainless steel nail trimmers. All samples were sealed in paper envelopes and sent to the laboratory. Each dog owner provided written informed consent to participate in the study and completed a questionnaire providing biometric data as well as details about their dog’s daily habits and medical history. The basic criteria for inclusion dogs in the study were age over six months and a minimum residence period of three months in the area. All dogs, except for two (E1 and E5 from former mining area, who eat the same food as their owners), were fed kibbles and drank tap water. Five dogs from former Salsigne mine also drank well water (E1-E4, E15), and two dogs (E13 and E14) drank river water in addition to tap water. Approval for the study experimental protocol, including the questionnaire for the dog owners, was granted by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zagreb, Croatia (Class: 640-01/23 − 02/13, Reg. No. 251-61-01/139-23-17). The study was performed in accordance with EU Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes and followed the ARRIVE guidelines for the reporting of animal research. The questionnaire was conducted with accordance to Declaration of Helsinki.

Metal(loid) analyses

Hair of dogs (0.3 g) was washed using the five-step washing procedure (acetone-water-water-water-acetone) recommended by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA64). This procedure involved the use of 20 mL of acetone (acetone for gas chromatography MS SupraSolv®, Merck, Germany) and ultrapure water (18 MΩ·cm, Smart2Pure 6 UV/UF system, Thermo Scientific, Hungary) in each step. Due to the lower weight (0.01–0.13 g) and consequently smaller surface area of the nail samples compared to hair, the washing procedure was conducted with 10 mL of acetone and water. After drying for 24 h at 40 °C, the hair and nails were transferred to Teflon tubes and digested with 2 mL of purified nitric acid (p.a. 65%, Merck, Germany; SubPUR/DuoPUR, Milestone, Italy) and 2 mL of ultrapure water in a microwave digestion system (UltraCLAVE IV, Milestone, Italy). Metal(loid)s (As, Ba, Ca, Cd, Co, Cu, Fe, Hg, Mg, Mn, Mo, Pb, Se, Tl, U, V, and Zn) were quantified by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; Agilent 8900, Agilent Technologies, Japan) using the method previously detailed elsewhere65–67. For analytical quality control and assurance, matrix matched and other animal tissue reference materials (RMs; Human hair IAEA-086, Austria; Human hair No. 13, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan; Bovine liver 1577a, National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA, and Pig kidney BCR-186, Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements, Belgium) were digested and measured alongside the sample series. The method detection limits, certified and observed metal(loid) levels in RMs are detailed in the Supplementary Table S6 (ESM1). Results were expressed in µg/kg or mg/kg dry mass of hair or nails.

Statistical analyses

The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, while visual inspection was performed using Q-Q plots. Data that did not fulfil the normality criteria (all metal(loid)s in hair, except Zn, and As, Ba, Cd, Hg, Mg, Mo, Pb, Se, U, and V in nails) were transformed using the Box-Cox transformation. The homogeneity of variance (Levene test) was confirmed for all variables.

For hair samples, where the sample size allowed the use of parametric methods, a one-way ANOVA was used to compare metal(loid) levels between dogs from the control and former mining area, as well as between sexes. Although a t-test would have been applicable in the case of two groups, ANOVA was chosen to ensure a consistent statistical approach across all analyses and to facilitate the subsequent assessment of covariate effects using ANCOVA. To examine the relationship between metal(loid) and age and body mass, simple linear regression models were used instead of correlation analysis, allowing quantification of the direction and strength of the effects of the predictor variables. In addition, a separate analysis was conducted only for dogs from the former mining area when an additional factor, dogs’ swimming habits, was included to investigate further patterns of association of age, sex, body mass and swimming habits with metal(loid) levels. In this analysis, as in the previous one, ANOVA and regression models were used, followed by ANCOVA. For nail metal(loid) levels, due to the significantly smaller sample size, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze differences between dogs from the control and former mining area, as well as between sexes. To increase the reliability of the results, a bootstrap analysis with 50,000 replicates was performed exclusively for the Mann-Whitney U test. The relationship between metal(loid) levels and age and body mass was assessed using simple linear regression.

Associations between hair and nail metal(loid) levels were studied using the Spearman’s rank correlation. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 18 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The help of dog owners, local groomers and veterinarians with the collection of samples is gratefully acknowledged. This study was funded by the Ministry of Science and Education of the Republic of Croatia through Institutional Funding and within the project HumEnHealth funded by the European Union – Next Generation EU (Program Contract of December 8, 2023, Class: 643-02/23-01/00016, Reg. no. 533-03-23- 0006). Study was performed using the facilities and equipment funded within the European Regional Development Fund project KK.01.1.1.02.0007 “Research and Education Centre of Environmental Health and Radiation Protection – Reconstruction and Expansion of the Institute for Medical Research and Occupational Health”.

Author contributions

ML, ARLP, and APC contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by ML, ARLP, TO, and MF. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ML and ARLP and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Each dog owner provided written informed consent to participate in the study and completed a questionnaire providing biometric data as well as details about their dog’s daily habits and medical history. Approval for the study was granted by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zagreb, Croatia (Class: 640-01/23 − 02/13, Reg. No. 251-61-01/139-23-17).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Maja Lazarus and Abigail R.L. Plançon contributed equally as first authors

References

- 1.Fendrich, A. N. et al. Modeling arsenic in European topsoils with a coupled semiparametric (GAMLSS-RF) model for censored data. Environ. Int.185, 108544 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchant, B. P., Saby, N. P. A. & Arrouays, D. A survey of topsoil arsenic and mercury concentrations across France. Chemosphere181, 635–644 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbaz-Poulichet, F. et al. The environmental legacy of historic Pb-Zn-Ag-Au mining in river basins of the Southern edge of the Massif central (France). Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int.24, 20725–20735 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khaska, M. et al. Arsenic and metallic trace elements cycling in the surface water-groundwater-soil continuum down gradient from a reclaimed mine area: Isotopic imprints. J. Hydrol.558, 341–355 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calas, A. et al. Air quality, metal(loid) sources identification and environmental assessment using (bio)monitoring in the former mining district of Salsigne (Orbiel valley, France). Chemosphere357, 141974 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drouhot, S. et al. Responses of wild small mammals to arsenic pollution at a partially remediated mining site in Southern France. Sci. Total Environ.470–471, 1012–1022 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delplace, G., Viers, J., Schreck, E., Oliva, P. & Behra, P. Pedo-geochemical background and sediment contamination of metal(loid)s in the old mining-district of Salsigne (Orbiel valley, France). Chemosphere287 (Pt 2), 132111 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khaska, M., Le Salle, G. L., Verdoux, C., Boutin, R. & P. & Tracking natural and anthropogenic origins of dissolved arsenic during surface and groundwater interaction in a post-closure mining context: Isotopic constraints. J. Contam. Hydrol.177–178, 122–135 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miquel, M. G., Report & on the Effects of Heavy Metals on the Environment and Health. Report No. 2979 (National Assembly) and No. 261 (Senate). Parliamentary Office for the Evaluation of Scientific and Technological Choices. [in French] (2001). https://www.senat.fr/rap/l00-261/l00-2611.pdf

- 10.U.S. E.P.A., United States Environmental Protection Agency Priority Pollutant List. (2014). https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/priority-pollutant-list-epa.pdf

- 11.Monchanin, C. Environmental exposure to metallic pollution impairs honey bee brain development and cognition. J. Hazard. Mater.465, 133218 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fréry, N., Ohayon, A. & Quenelle, P. On the Exposure of the Population to Industrial Pollutants in the Salsigne Region (Aude). National Public Health Network [in French] (1998). https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/regions/occitanie/documents/rapport-synthese/1998/enquete-sur-l-exposition-de-la-population-aux-polluants-d-origine-industrielle.-region-de-salsigne-aude

- 13.A.R.S., Regional Health Agency. Press Release: Medical Monitoring in the Orbiel Valley: 191 Children have Already Benefited from the Monitoring System Set up by the ARS, with the Expertise of the Poison Control and Toxicovigilance Center. [in French] (2019). https://www.occitanie.ars.sante.fr/media/41571/download?inline

- 14.Saoudi, A. et al. Urinary arsenic levels in the French adult population: The French National nutrition and health study, 2006–2007. Sci. Total Environ.433, 206–215 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dondon, M. G., de Vathaire, F., Quénel, P. & Fréry, N. Cancer mortality during the 1968–1994 period in a mining area in France. Eur. J. Cancer Prev.14, 297–301 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.A.T.S.D.R., Agency for Toxic Substances and Diseases Registry. Toxicological profile for Arsenic. Agency for Toxic Substances and Diseases Registry, U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA (2007). https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp2.pdf

- 17.EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Update of the risk assessment of inorganic arsenic in food. EFSA J.22, e8488. 10.2903/j.efsa.2024.8488 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegedus, C. et al. Pets, genuine tools of environmental pollutant detection. Anim. (Basel). 13, 2923 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastorinho, M. R. & Sousa, A. C. A. Pets as sentinels of human exposure to neurotoxic metals, in Pets as Sentinels, Forecasters and Promoters of Human Health (eds. Pastorinho, M. & Sousa, A.) (2020). 10.1007/978-3-030-30734-9_5

- 20.Jota Baptista, C., Seixas, F., Gonzalo-Orden, J. M. & Oliveira, P. A. Biomonitoring metals and metalloids in wild mammals: Invasive versus non-invasive sampling. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int.29, 18398–18407 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García-Muñoz, J., Pérez-López, M., Soler, F., Prado Míguez-Santiyán, M. & Martínez-Morcillo, S. Non-invasive samples for biomonitoring heavy metals in terrestrial ecosystems. Trace Met. Environ.10.5772/intechopen.1001334 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Button, M., Jenkin, G. R., Harrington, C. F. & Watts, M. J. Human toenails as a biomarker of exposure to elevated environmental arsenic. J. Environ. Monit.11, 610–617 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandal, B. K., Ogra, Y. & Suzuki, K. T. Speciation of arsenic in human nail and hair from arsenic-affected area by HPLC-inductively coupled argon plasma mass spectrometry. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.189, 73–83 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gault, A. G. et al. Arsenic in hair and nails of individuals exposed to arsenic-rich groundwaters in Kandal province, Cambodia. Sci. Total Environ.393, 168–176 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.How, V., Wong, W. V., Leong, J. Y., Robun, C. & Anual, Z. F. Evaluation of trace element in the hair and nail samples of conventional and organic farmers in pesticide-treated Highland villages. Environ. Geochem. Health. 47, 318 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yüksel, B., Kayaalti, Z., Sӧylemezoglu, T., Türksoy, V. A. & Tutkun, E. GFAAS determination of arsenic levels in biological samples of workers occupationally exposed to metals: An application in analytical toxicology. Spectrosc.36, 171–176 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yüksel, B., Şen, N., Türksoy, V. A., Tutkun, E. & Söylemezoğlu, T. Effect of exposure time and smoking habit on arsenic levels in biological samples of metal workers in comparison with controls. Marmara Pharm. J.22, 218–226 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Signes-Pastor, A. J. et al. Toenails as a biomarker of exposure to arsenic: A review. Environ. Res.195, 110286 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neiger, R. D. & Osweiler, G. D. Arsenic concentrations in tissues and body fluids of dogs on chronic low-level dietary sodium arsenite. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest.4, 334–337 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosendahl, S. et al. Diet and dog characteristics affect major and trace elements in hair and blood of healthy dogs. Vet. Res. Commun.46, 261–275 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosendahl, S., Anturaniemi, J. & Hielm-Björkman, A. Hair arsenic level in rice-based diet-fed Staffordshire bull terriers. Vet. Rec. 186, e15. 10.1136/vr.105493 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jafari, S. Use of pets as indicators of heavy metal exposure across Sydney. Master’s Thesis, Macquarie University, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Sydney, Australia. (2014). 10.25949/19440725.v1

- 33.Vázquez, C., Palacios, O., Boeykens, S. & Marcó Parra, L. M. Domestic dog hair samples as biomarkers of arsenic contamination. X-Ray Spectrom.42, 220–223 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tête, N. et al. Hair as a noninvasive tool for risk assessment: Do the concentrations of cadmium and lead in the hair of wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) reflect internal concentrations? Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.108, 233–241 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernout, B. V. et al. Fur: A non-invasive approach to monitor metal exposure in bats. Chemosphere147, 376–381 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amuno, S. et al. Comparative study of arsenic toxicosis and ocular pathology in wild muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus) and red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) breeding in arsenic contaminated areas of yellowknife, Northwest territories (Canada). Chemosphere248, 126011 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amuno, S., Jamwal, A., Grahn, B. & Niyogi, S. Chronic arsenicosis and cadmium exposure in wild snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) breeding near yellowknife, Northwest territories (Canada), part 1: Evaluation of oxidative stress, antioxidant activities and hepatic damage. Sci. Total Environ.618, 916–926 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao, C. et al. Changes in arsenic accumulation and metabolic capacity after environmental management measures in mining area. Sci. Total Environ.855, 158652 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ARS, Regional Health Agency. Drinking Water - Results of Sanitary Control Analyses of Water Intended for Human Consumption [in French] (2024). https://orobnat.sante.gouv.fr/orobnat/afficherPage.do?methode=menu&usd=AEP&idRegion=76

- 40.WHO, World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda (World Health Organization, 2022). https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352532/9789240045064-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [PubMed]

- 41.Cowell, C. S., Stout, N. P., Brinkmann, M. F., Moser, E. A. & Crane, S. W. Making of commercial pet foods, in Small animal clinical nutrition (eds. Hand, M.S., Thatcher, C.D., Remillard, R.L. & Roudebush, P.) 127–146 (2000).

- 42.Loh, M. M. et al. Multimedia exposures to arsenic and lead for children near an inactive mine tailings and smelter site. Environ. Res.146, 331–339 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin, R., Dowling, K., Pearce, D., Bennett, J. & Stopic, A. Ongoing soil arsenic exposure of children living in an historical gold mining area in regional victoria, Australia: Identifying risk factors associated with uptake. J. Asian Earth Sci.77, 256–261 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearce, D. C. et al. Arsenic microdistribution and speciation in toenail clippings of children living in a historic gold mining area. Sci. Total Environ.408, 2590–2599 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen, X., Cao, S., Wen, D., Geng, Y. & Duan, X. Sentinel animals for monitoring the environmental lead exposure: Combination of traditional review and visualization analysis. Environ. Geochem. Health. 45, 561–584 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frank, D. Repetitive behaviors in cats and dogs: are they really a sign of obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD)? Can. Vet. J.54, 129–131 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eastern Research Group. Hair Analysis Panel Discussion: Exploring the State of the Science, June 12–13, 2001: Summary Report Prepared for the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Division of Health Assessment and Consultation and Division of Health Education and Promotion. (2001). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-HE20-PURL-LPS105404/pdf/GOVPUB-HE20-PURL-LPS105404.pdf

- 48.Ferrante, M. et al. Trace elements bioaccumulation in liver and fur of Myotis myotis from two caves of the Eastern side of Sicily (Italy): A comparison between a control and a polluted area. Environ. Pollut. 240, 273–285 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gunaratnam, P. & Wilkinson, G. T. A study of normal hair growth in dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract.24, 445–453 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kozak, M., Kralova, E., Sviatko, P., Bilek, J. & Bugarsky, A. Study of the content of heavy metals related to environmental load in urban areas in Slovakia. Bratisl Lek Listy. 103, 231–237 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosendahl, S. et al. Mineral, trace element, and toxic metal concentration in hair from dogs with idiopathic epilepsy compared to healthy controls. J. Vet. Intern. Med.37, 1100–1110 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaccaroni, A. et al. Elements levels in dogs from triangle of death and different areas of campania region (Italy). Chemosphere108, 62–69 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puls, R. Mineral Levels in Animal Health. Diagnostic Data (Sherpa International, 1994).

- 54.Contreras, E. T., Bruner, K., Hegwer, C. & Simpson, A. Claw growth rates in a subset of adult, indoor, domestic cats (Felis catus). Vet. Dermatol.36, 362–367 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Orentreich, N., Markofsky, J. & Vogelman, J. H. The effect of aging on the rate of linear nail growth. J. Invest. Dermatol.73, 126–130 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hopps, H. C. The biologic bases for using hair and nail for analyses of trace elements. Sci. Total Environ.7, 71–89 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chakraborti, D. et al. Environmental arsenic contamination and its health effects in a historic gold mining area of the Mangalur greenstone belt of Northeastern karnataka, India. J. Hazard. Mater.262, 1048–1055 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coelho, P. et al. Metal(loid) levels in biological matrices from human populations exposed to mining contamination-Panasqueira mine (Portugal). J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 75, 893–908 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Géorisques Ministry of Ecological Transition and Territorial Cohesion Understanding the Risks Near My Home. Ministry of Ecological Transition, Energy, Climate, and Risk Prevention, French Republic [in French] (2024). https://www.georisques.gouv.fr/

- 60.Géorisques, Ministry of Ecological Transition and Territorial & Cohesion, C. A. S. I. A. S. Map of Former Industrial Sites and Service Activities. Ministry of Ecological Transition, Energy, Climate, and Risk Prevention, French Republic [in French] (2021). https://www.georisques.gouv.fr/donnees/bases-de-donnees/inventaire-historique-de-sites-industriels-et-activites-de-service

- 61.Pérez, G. & Valiente, M. Determination of pollution trends in an abandoned mining site by application of a multivariate statistical analysis to heavy metals fractionation using SM&T-SES. J. Env Monit.7, 29–36 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Asselin, E. & Shaw, R. Developments in arsenic management in the gold industry, in Gold ore processing: project, development and operations (ed. Adams, M.D.) 739–751 (2016).

- 63.INSEE, French National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies. Population census 2021 (2021). https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/zones/7725600?geo=COM-11069&debut=0

- 64.Ryabukhin, Y. S. Activation analysis of hair as an indicator of contamination of man by environmental trace element pollutants. IAEA Rep, IAEA/RL/50 (1976). https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN

- 65.Vihnanek Lazarus, M. et al. Cadmium and lead in grey Wolf liver samples: Optimization of a microwave-assisted digestion method. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 64, 395–403 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lazarus, M. et al. Stress and reproductive hormones in hair associated with contaminant metal(loid)s of European brown bear (Ursus arctos). Chemosphere325, 138354 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lazarus, M. et al. Metal(loid) exposure assessment and biomarker responses in captive and free-ranging European brown bear (Ursus arctos). Environ. Res.183, 109166 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.